Abstract

Background

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are exposed to a multitude of hazards in the hospital environment, increasing their risks of sustaining injuries at a higher rate compared to workers in other sectors and resulting in substantial level of modified work and absenteeism. This study aims to examine the burden and determinants of occupational injury severity of HCWs at a tertiary care hospital in Lebanon.

Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional study examined incident reports completed by HCWs over a period of 5 years (January 2018 to December 2022). Injury severity was assessed by HCWs’ need for an Emergency Department (ED) visit after sustaining an injury at work. The association with age, sex, occupation, and type of injury was examined. Results were reported as adjusted OR, with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals and p-values, using logistic regression.

Results

1,772 injury reports were recorded, of which 790 were included for analysis since the sample was limited to the outpatient clinic opening hours to ensure a more accurate assessment of injury severity. Of these, 27% required an ED visit. Male sex (OR = 1.601, p-value = 0.005) was associated with more severe injuries. Transportation injuries (OR = 5.927, p-value = 0.001) were more severe compared to other injury mechanism, while needle-pricks (OR = 0.008, p-value = 0.000), exposure to blood products (OR = 0.025, p-value = 0.000), and exposure to harmful substances (OR = 0.209, p-value = 0.003) were less severe. Age and occupation only showed significance at the bivariate level.

Conclusion

This study highlighted significant determinants of injury severity among HCWs, emphasizing the critical need for targeted interventions for individuals at risk. Implementing comprehensive safety and wellness programs can enhance the overall health and safety of HCWs in high-stress environments.

Keywords: Healthcare workers, Injury severity, Emergency department, Tailored interventions, Blood-borne pathogens, Transportation incidents

Background

Healthcare workers (HCWs) play a crucial role within society and the healthcare system, a responsibility highlighted during the recent COVID-19 pandemic when they were widely recognized as “heroes” [1] for their critical contribution to saving lives. HCWs occupational environment is associated with numerous hazards, making employees prone to various workplace injuries [2, 3]. Working in the healthcare field, especially hospitals, poses unique challenges [2, 3] compared to other sectors traditionally deemed as high risk, such as mining, construction, and transportation. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports that healthcare recorded the highest number of nonfatal recordable injuries and illnesses in 2022, compared to other sectors, with an incidence rate of 6.1 per 100 full-time employees (FTE) [4]. Over half of these documented cases (3.2 per 100 FTE) result in lost workdays, job restriction, or transfer [4]. These rates match or exceed those of other industries including the goods-producing (2.9 per 100 FTE), construction (2.4 per 100 FTE), and manufacturing (3.2 per 100 FTE) sectors [4].

Due to the fast pace and demanding nature of their work, HCWs face a multitude of serious hazards [2, 3, 5, 6]. The latter include exposure to biological hazards, such as communicable diseases and blood-borne pathogens (BBP) [2, 7, 8]. BBP refer to infectious microorganisms carried in human blood and other body fluids, and can potentially cause diseases [9]. The most common BBP are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) [9]. According to the CDC, HCWs are at risk of contracting BBP by “a percutaneous injury in which a health care worker is injured by a sharps object, or a mucocutaneous exposure incident with contact of a mucous membrane or non-intact skin with blood, tissue, or other potentially infectious bodily fluids” [9]. Moreover, hospital workers face chemical hazards (i.e., drug residue, laboratory work, inhaled anesthetics, etc.) [2, 7], physical hazards (i.e., radioactive material, radiation, etc.) [2, 7], and ergonomic hazards (mainly from lifting and re-positioning of patients and repetitive tasks) [2, 7, 10]. Further to the physical exposure, HCWs are at an increased risk of psychological stressors and violence [11]. These hazards are often reported by HCWs as “incidents” or unexpected events which are not consistent with the routine operation and that adversely affect or threaten to affect the health, safety, or well-being of the HCWs. According to the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis, the global prevalence of needle stick injuries among HCWs during career time and previous one year is 56.2% and 32.4%, respectively [12]. Moreover, musculoskeletal injuries are highly prevalent: 55% of HCWs suffered in the previous twelve months from back pain, 44% from shoulder pain, and 42% from neck pain [13].

The scarcity of comprehensive studies on determinants of injury severity among HCWs is a notable gap in the existing literature, especially in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. A Turkish study demonstrated that nearly one fourth of injured HCWs were unable to work without absence after sustaining an occupational injury [14]. While most studies focus on industries such as construction [15], mining [16], and transportation [17, 18], few studies focus on the burden and determinants of occupational injury severity within the healthcare setting. Factors contributing to injury severity among HCWs remain poorly understood, hindering efforts to implement adequate evidence-based preventive measures and interventions. The limited focus on studying injury severity among HCWs may have contributed to persistent misconceptions about health and safety in hospital settings and undermine efforts to prioritize occupational health and safety measures.

In Lebanon, a country located in the MENA region and recently re-classified by the World Bank as a low- or middle- income country (LMIC) following its recent socio-economic crisis [19], HCWs are working under unconventional stress levels, especially after the massive exodus of many HCWs post crises [20]. Few studies examined hospitals’ occupational injuries in resource-constrained settings [8]. The objective of this study is to explore the prevalence and determinants of injury severity among HCWs at a tertiary care center in Lebanon.

Methods

Study design and setting

This is a retrospective, cross-sectional, single-site study that examined injuries sustained by all HCWs at the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC) - a tertiary hospital in Lebanon, over a period of 5 years from January 2018 to December 2022. AUBMC is one of the largest medical centers located in Beirut, the capital of Lebanon. It offers tertiary care to over 360,000 patients per year and employs around 3,600 HCWs.

Participants

The study uses secondary data from incident reports filled by all HCWs who sustained an occupational injury while performing their duties at AUBMC between January 2018 till December 2022. Within the context of this study, HCWs include hospital employees involved in clinical services: Practical Nurses (PNs), Registered Nurses (RNs), allied health professionals (laboratory technicians, pharmacists, phlebotomists, anesthesia therapists, physical therapists, radiographers, nutritionists, and infection control staff), Residents, and Physicians.

Data collection

The study utilized secondary data analysis of all incident report forms completed by AUBMC HCWs and submitted to the Environmental Health, Safety, and Risk Management department (EHSRM). Reported incidents result from exposures to different kinds of hazards during performance of the HCW’s job duties and cause an injury. The incident report form includes information related to the injured HCW demographics (i.e., age, sex), job title, department, the mechanism of injury and location and time of the incident, and whether a visit to the ED was warranted. The form is maintained separately from the employee’s health record, and hence it is not possible to obtain any further data on hospitalization, surgeries, or work absenteeism that followed the injury based on the incident report database only. To ensure anonymity and confidentiality, incident data were de-identified by a health and safety officer prior to sharing with the research team.

Measures

The main outcome of the study is injury severity, assessed by the dichotomous variable “Emergency Department visit” (yes/no). The institution offers University Health Services (UHS) at the Family Medicine clinics for all HCWs. UHS provides a wide range of primary care services except the severe ones. During UHS operating hours (weekdays and day shifts), HCWs with less severe injuries typically visit the clinic for treatment. In contrast, severe injuries are directed to the ED. On weekends and evening/night shifts, the ED remains the only accessible option, regardless of injury severity. Therefore, we excluded injuries that occurred during weekends and evening/night shifts. The independent variables from the incident report form are: age, sex, occupation, and mechanism of injury.

Sources of bias

There records (incident report forms) are filled in a relatively complete and accurate way, thus reducing risks of information bias. In addition to the culture of reporting at the institution, there is a financial incentive for HCWs to report accurately any incident or injury sustained at work, as all medical fees and sick leaves will be totally covered, in comparison to the medical care covered by insurance that is subject to personal payments such as deductibles and co-pays. Moreover, to avoid selection bias and to ensure that the primary outcome– injury severity– was assessed consistently across cases, the restriction by design approach was employed. This categorization process ensured that severity assessment was not biased by differential access to healthcare services.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to characterize the study sample. Categorical variables (ED visit, sex, occupation, and mechanism of injury) were depicted by frequency and percentage. Mean and standard deviation were calculated for continuous variables (age). To investigate the relationship between the outcome (ED visit) and other predictors, each predictor was separately analyzed through a simple logistic regression. Unadjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported as well as the p-values. Variables with p-value < 0.2 in the unadjusted models were considered eligible to be included in the multiple logistic regression model, and added successively using the forward selection method. Results were presented as adjusted ORs and their corresponding 95% CIs. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The adjusted model’s overall p-value was 0.000 with a pseudo R-squared = 0.5708. The goodness-of-fit of the adjusted model was tested (p-value = 0.1001: the model adequately fits the data). All analyses were conducted on Stata software, version 17.

Results

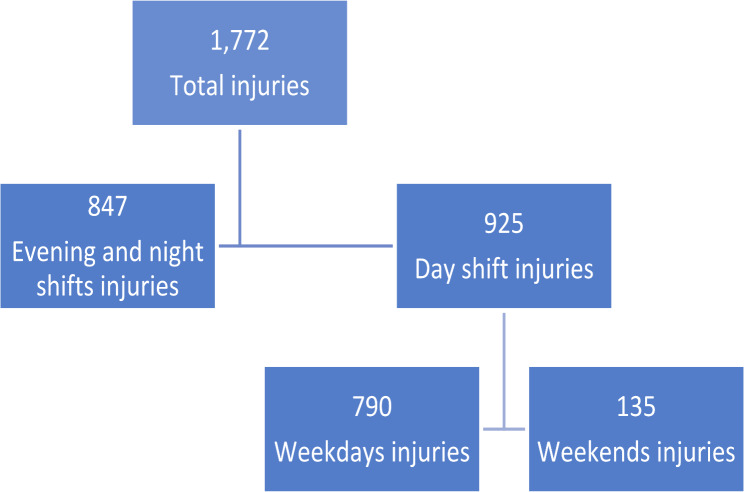

A total of 1,772 injuries were recorded through incident reporting by HCWs at the hospital between 2018 and 2022. After excluding those occurred on weekends and on evening/night shifts, 790 incidents remained for analysis (Fig. 1). This approach ensured that our severity assessment was not biased by differential access to healthcare services, as ED visits during day shifts of the weekdays were more likely to reflect truly severe injuries rather than a lack of alternative care options.

Fig. 1.

Selection of reported HCWs injuries for analysis

There were no fatal occupational injuries recorded at the hospital during the study period. The mean age for injured HCWs was 34.70 years (+/- 11.02). The majority were males (52.08%) and 26.98% were considered severe injuries that required evaluation and treatment at the ED (Table 1). Most injuries were due to needle stick and other sharp exposures (50.25%) and slips, trips, and falls (11.77%), and sustained by residents (29.24%) and RNs (24.30%).

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of the study participants

| Covariate | Frequency (percentage) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 375 (52.08%) |

| Female | 345 (47.92%) |

| Yes | 208 (26.98%) |

| No | 563 (73.02%) |

| Subtotal | 771 (100%) |

| Mechanism of injury | |

| Needle Stick & Other Sharp Object Injury* | 397 (50.25%) |

| Slips, Trips & Falls | 93 (11.77%) |

| Exposure to Blood or other Body Fluid* | 78 (9.87%) |

| Transportation accidents | 76 (9.62%) |

| Contact with Objects or Equipment | 70 (8.86%) |

| Overexertion and Bodily Reaction | 29 (3.67%) |

| Exposure to or contact with harmful substances or environments | 29 (3.67%) |

| Non-contaminated Sharp Object Injury | 13 (1.65%) |

| Violence** | 5 (0.87%) |

| Subtotal | 790 (100%) |

| Occupation | |

| Registered Nurse | 192 (24.30%) |

| Resident | 231 (29.24%) |

| Practical Nurse | 124 (15.70%) |

| Allied health professional | 154 (19.49%) |

| Physician | 89 (11.27%) |

| Subtotal | 790 (100%) |

(* Both “Needle Stick & Other Sharp Object Injury” and “Exposure to Blood or other Body Fluid” are considered blood-borne pathogen BBP exposures

** Violence refers to any physical or verbal assault to the HCWs by patients, patients’ families, coworkers, or supervisors)

The unadjusted odds ratio (OR) of sustaining a severe injury (higher odds of visiting the ED), according to different predictors are shown in Table 2. “Female”, “practical nurse” and “contact with objects or equipment” are used as reference categories for the variables “sex”, “occupation” and “mechanism of injury”, respectively. With each one-year increase in age, the risk for severe injuries increased (unadjusted OR = 1.026, p-value = 0.000). Additionally, male sex was associated with a higher risk for severe injuries (unadjusted OR = 1.511, p-value = 0.013). Occupation (p-value = 0.000) also showed significant results: Registered Nurses (unadjusted OR = 0.475, p-value = 0.002), residents (unadjusted OR = 0.004, p-value = 0.000), and physicians (unadjusted OR = 0.043, p-value = 0.000) recorded less severe injuries that Practical Nurses. Finally, the mechanism of injury (p-value = 0.000) was a significant predictor of severity in the unadjusted analysis.

Table 2.

Simple logistic regression analysis of the outcome (ED visit) and other covariates

| Covariate | Unadjusted OR | 95% CI for unadjusted OR | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.026 | 1.012; 1.041 | 0.000* |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1.511 | 1.089; 2.095 | 0.013* |

| Female (reference) | --- | --- | --- |

| Mechanism of injury | 0.000* | ||

| Needle Stick & Other Sharp Object Injury | 0.004 | 0.001; 0.013 | 0.000* |

| Slips, Trips & Falls | 0.624 | 0.321; 1.216 | 0.166* |

| Exposure to Blood or other Body Fluid | 0.013 | 0.003; 0.059 | 0.000* |

| Transportation accidents | 5.409 | 2.023; 14.461 | 0.001* |

| Contact with Objects or Equipment (reference) | --- | --- | --- |

| Overexertion and Bodily Reaction | 0.907 | 0.359; 2.288 | 0.836 |

| Exposure to or contact with harmful substances or environments | 0.226 | 0.088; 0.584 | 0.002* |

| Non-contaminated Sharp Object Injury | |||

| Violence | 0.074 | 0.296; 3.891 | 0.914 |

| 0.716 | 0.111; 4.613 | 0.725 | |

| Occupation | 0.000* | ||

| Registered Nurse | 0.475 | 0.295; 0.757 | 0.002* |

| Resident | 0.004 | 0.001; 0.029 | 0.000* |

| Practical Nurse (reference) | --- | --- | --- |

| Allied health professional | 0.891 | 0.551; 1.441 | 0.637 |

| Physician | 0.043 | 0.015; 0.124 | 0.000* |

(* p-value < 0.2 is considered eligible to be included in the full regression model)

Table 3 shows the adjusted OR for sustaining a severe injury, accounting for other co-variates. Males had higher odds of sustaining a severe injury than females (adjusted OR = 2.358, p-value = 0.002) (risk factor). Injuries resulting from transportation accidents (adjusted OR = 5.927, p-value = 0.001) were also more severe compared to other injuries (risk factor). In contrast, injuries resulting from exposure to BBP were considered less severe compared to other injury mechanisms (protective factor): exposure to blood or other body fluid (adjusted OR = 0.025, p-value = 0.000) and needle-stick injuries (adjusted OR = 0.008, p-value = 0.000). Exposure to or contact with harmful substances or environments (adjusted OR = 0.209, p-value = 0.003) were also found to be less severe (protective factor). Finally, the adjusted analysis showed no statistically significant association with the occupation.

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regression analysis of the outcome (ED visit) with other covariates

| Covariate | β coefficient | Adjusted OR | 95% CI for adjusted OR | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | -0.003 | 0.993 | 0.969; 1.018 | 0.587 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 0.373 | 2.358 | 1.370; 4.057 | 0.002* |

| Female (reference) | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Mechanism of injury | ||||

| Needle Stick & Other Sharp Object Injury | -2.097 | 0.008 | 0.002; 0.031 | 0.000* |

| Slips, Trips & Falls | -0.143 | 0.719 | 0.357; 1.448 | 0.356 |

| Exposure to Blood or other Body Fluid | -1.602 | 0.025 | 0.005; 0.118 | 0.000* |

| Transportation accidents | 0.773 | 5.927 | 2.118; 16.585 | 0.001* |

| Contact with Objects or Equipment (reference) | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Overexertion and Bodily Reaction | ||||

| Exposure to or contact with harmful substances or environments | -0.06 | 0.871 | 0.330; 2.299 | 0.78 |

| Non-contaminated Sharp Object Injury | -0.68 | 0.209 | 0.075; 0.585 | 0.003* |

| Violence | ||||

| 0.24 | 1.737 | 0.161; 18.751 | 0.649 | |

| Occupation | ||||

| Registered Nurse | -0.084 | 0.825 | 0.405; 1.679 | 0.596 |

| Resident | -0.845 | 0.143 | 0.016; 1.264 | 0.08 |

| Practical Nurse (reference) | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Allied health professional | 0.121 | 1.321 | 0.679; 2.571 | 0.412 |

| Physician | -0.291 | 0.512 | 0.102; 2.560 | 0.415 |

(* p-value ≤ 0.05 is considered statistically significant)

Discussion

This study investigates the determinants of injury severity among HCWs at a tertiary hospital, over a five-year period. To our knowledge, this is the first study that explores the severity of injuries sustained by HCWs while performing their clinical duties. Several studies have been conducted across various industries and sectors [15, 18], but few have focused on hospitals. The findings highlight the critical need for tailored safety measures and interventions to reduce the severity of injuries sustained by HCW on the job. By identifying key determinants of injury severity, the results can provide insights to guide the development of effective prevention strategies and improve workplace safety in healthcare environments. This study showed that approximately 27% of all reported injuries required urgent evaluation at the ED. The key findings indicated that injury severity, defined by the necessity of an ED visit, is significantly associated with sex and type of injury, but not with occupation.

Within the context of this study, males sustained more severe injuries than females. This aligns with previous research documenting a male predominance in injury severity and ED visits in different industries [21–23]. In a study investigating the characteristics of occupational injuries among Spanish nurses, men were found to suffer more severe injuries than women [24]. Similarly, in the healthcare setting, evidence has shown that the rate of fatal injuries was the highest among older men [25]. This sex disparity could be multifaceted, involving differences in job roles, physical demands, and reporting behaviors.

As for age, the analysis failed to confirm any significant association. Some evidence suggested that older workers sustain more severe injuries [22, 26, 27]. However, according to a recent systematic review, nearly half of the examined studies showed no severity difference between older and younger workers [28], introducing uncertainty into classifying age as a risk or protective factor for occupational injury severity [28]. The rationale behind such inconclusive results could be that younger workers are involved in more hazardous jobs, while older workers are more susceptible to injuries.

Exposure to bloodborne pathogens (BBP) through needle pricks and contact with blood and other body fluids was found to be less severe compared to other injury mechanisms. However, such injuries are known to carry a substantial psychologic burden and serious emotional distress among HCWs who experience a needle-stick by fear of transmission of a virus [29]. BBP exposures contribute to 39%, 37% and 4.4% of hepatitis C, hepatitis B and HIV infections respectively, among HCWs [30]. Moreover, BBP impose high cost on the healthcare system, particularly as exposed employee are required to undergo comprehensive serologic testing at various time intervals and follow-up assessments at the clinic if the source was positive for any of the BBP [29].

Exposure to harmful substances or environments was also found to be less severe compared to other injury mechanism. HCWs who reported such injuries were mainly exposed to chemicals at the hospital. According to a review on occupational chemical exposures, HCWs are mainly at increased risk of irritant and allergic contact dermatitis [31]. They are commonly exposed to biocides used for application such as the sterilization of medical devices, quaternary ammonia compounds for disinfection, and allergens found in medical gloves and sanitizers [31]. These common conditions are usually treated in the clinic and rarely require an urgent ED visit.

Transport-related injuries were found to be more severe compared to other injury mechanism. This finding aligns with previous evidence from the literature in both the healthcare setting [22, 25] and other industries [17]. In Lebanon, injuries sustained by employees while commuting to work are considered work-related by Labor law. Shift work (which is the case of most HCWs) is correlated with higher incidence of road traffic injuries [32]. This issue is highly noticeable in LMIC, where the infrastructure may be less developed, traffic regulations less strictly enforced, and public transportation frequently unavailable [33]. In such settings, the combination of shift work and challenging commuting conditions may increase the risk of transport-related injuries among HCWs. Few studies have been conducted in the healthcare industry, indicating that transportation work-related injuries tend to be severe [22] and result in higher fatality rates [25].

Finally, our findings at the bivariate level showed that PNs sustain more severe injuries compared to other HCWs. PNs and other assistant nursing personnel are involved in physically demanding jobs that require lifting, positioning, toileting and ambulating patients [34]. Such repetitive and fast-paced tasks, often completed when standing in awkward postures, put HCWs at an increased risk of musculoskeletal injuries, mostly back and other joints injuries [34]. The burden of such injuries among nurses is reflected by the increased rate of sick leaves and worker’s compensation claims [35].

Study limitations and strengths

This study has some limitations. First, the findings are based on data from a single tertiary care center, which may limit the generalizability of results to other healthcare settings or regions with different reporting systems, organizational practices and cultural contexts. Second, using ED visits to estimate injury severity could be considered a limited proxy measure. In the context of this study, the only available information was the occurrence of an ED visit. It was not possible to access additional data since the incident report form is maintained separately from the electronic medical chart of the workers. However, the exclusion by design approach of the injuries recorded during the UHS clinics closure times can potentially address this limitation. Third, the data might have over-reported BBP exposures, since HCWs fear transmissions of viruses and wish to conduct regular testing and follow ups as indicated. This is in contrast with a potential under-reporting of musculoskeletal injuries, because many HCWs might be apprehensive to declare such incidents by fear of retaliation or job transfer [36, 37]. Finally, routinely collected data allow for a minimal amount of data to be collected and do not serve as an accurate and complete source of information. While our study provides valuable insights into injury determinants, the absence of post-injury care data (incident related sick leave, hospitalizations, surgeries, and resulting modified work) limits the ability to categorize injuries based on clinical severity beyond incident report classifications. Future research utilizing electronic health records and administrative sick leave data will provide a more comprehensive analysis of injury severity, including hospitalization, surgical interventions, and return-to-work timelines.

This study has several strengths that are worth emphasizing. First, it involves a comprehensive dataset collected over five years, encompassing a large number of incidents. The multifactorial analysis, through employing a multiple logistic regression model, effectively identifies and adjusts for various confounding factors, providing a clear understanding of the simultaneous impact of different predictors on injury severity. Second, the incident reports were completed in an accurate, reliable, and consistent way. The de-identified injury dataset was retrieved from the online incident report. This electronic system is user-friendly, and the injured worker can easily submit an incident immediately when it occurs on the day of the injury. Using such records ensures greater data accuracy, reliability, and objectivity, instead of relying on participants’ retrospective recollection of injuries. Third, the study examines occupational injury severity within the broader context of socio-economic crisis, workforce restructuring and the COVID-19 pandemic in an LMIC setting. It provides valuable insights specific to the MENA context, which is underrepresented in the occupational health literature. Despite its global burden [38], occupational injuries tend to be under-reported, especially in LMIC due to the low resource setting and the lack of surveillance systems [39, 40].

Recommendations

Occupational injuries are preventable causes of morbidity and mortality. In the light of the findings of this study, we propose a series of recommendations to mitigate the risk of sustaining severe injuries by HCWs.

Engineering controls: Hospitals should prioritize engineering measures to enhance workplace safety and minimize injury risks for HCWs. This includes the adoption of safety-engineered devices (such as retractable needles), ergonomic workplace design, and well-maintained lifting equipment to reduce the physical strain associated with patient handling. Additionally, hospitals should install slip-resistant flooring in high-risk areas, ensure adequate lighting and hazard signage, and provide adjustable workstations to accommodate different HCWs’ needs. The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) should also be promoted. HCWs commuting to work by motorcycle (a common practice in LMIC) should be required to wear a helmet, protective clothing, such as knees and elbows pads. The use of slip-resistant footwear is also essential to avoid slips, trips, and falls.

Safe patient handling and motility (SPHM) program: The implementation of an evidence-based SPHM program through a minimal lift policy and the promotion of lifting equipment is highly encouraged [41]. Targeted training for PNs, a group of employees with higher rates of severe injuries, and other high-risk groups on safe handling practices and injury prevention can mitigate the risk of severe injuries. Hospitals should establish regular safety audits, compliance monitoring, and feedback mechanisms to assess program adherence and identify areas for improvement.

Occupational health documentation: The incorporation of a standardized measure of injury severity in occupational health records is needed. This improvement would facilitate more accurate assessments in future studies and support better workplace safety interventions.

Psychosocial support: Continuous support of HCWs’ mental health and well-being is important. Stress management resources and wellness programs can help alleviate the negative effects of job strain. A culture of open communication is essential to address the psychological and emotional needs of HCWs. These initiatives closely align with the NIOSH Total Worker Health® (TWH) program that integrates health promotion and workplace safety, to advance workers’ well-being [42]. By adopting the TWH approach, hospitals can develop more holistic support systems and promote injury-prevention efforts for a healthier workforce [42].

Behavioral change interventions: Safety measures aiming at reducing injury risk and fostering a culture of safety are instrumental to be implemented at both individual and organizational levels. Behaviors, such as unsafe driving when commuting to work and not respecting safety signs should be changed. Training sessions, education and strengthening safety protocols, especially for activities prone to causing severe injuries are essential. Furthermore, since in the context of our study there was no way of knowing how many of the transport injuries were from people commuting to work versus those conducting hospital/university business in a vehicle, one suggestion is to modify the occupational health record to more easily identify these two groups. This is important for planning future interventions, including general transport, safety awareness, campaigns, and dedicated mandatory training for drivers and other university employees that are more highly exposed to transport injury.

Conclusion

This study shows that one-fourth of occupational injuries sustained by HCWs are severe and that severity is associated with sex and mechanism of injury, but not with age or occupation. It provides critical insights into the determinants of injury severity among HCWs, highlighting the need for targeted interventions to improve health and safety in hospital settings. By addressing the identified risk factors and enhancing safety protocols, it is possible to mitigate the severity of occupational injuries on HCWs and ensure a safer workplace. Future studies should focus on assessing the cost associated with these injuries and related sick leaves for a more accurate estimate of the overall burden. Further studies on road traffic incidents, particularly within the context of low- and middle- income countries (LMICs), are also of high priority.

Abbreviations

- BBP

Blood-borne pathogens

- ED

Emergency Department

- FTE

Full-time employee

- HCWs

Healthcare workers

- LMIC

Low- and middle-income countries

- MENA

Middle East and North Africa

- OR

Odds ratio

- PN

Practical nurses

- RN

Registered nurses

- UHS

University health services

Author contributions

CJS, GK, and HM conceptualized the study, GK reviewed the literature. GK and CJS collected and analyzed the data. GK and CJS wrote the original draft. HM, DR and SH made significant contributions to the design and analysis, and reviewed it. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Fogarty International Center of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), under the Global Environmental and Occupational Health Research and Training Hub for the Middle East and North Africa (GEOHealth-MENA) training grant number U2RTW012231 and the Global Health Emerging Scholars Program, NIH FIC D43TW010540. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the Open Science Framework repository: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2HFQX.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board at the American University of Beirut (AUB IRB ID: BIO-2023-0052). Because this study uses existing data, and there was no contact with human subjects, Yale IRB Human Research Protection Program (HRPP) considered this as non-human-subject research (Yale IRB ID: 2000035933). No informed consent was required since the study involved a secondary analysis of de-identified incident report forms that are not linked to the medical record of the participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Diana V Rahme and Carine J Sakr are equally contributing authors.

References

- 1.Cox CL. Healthcare heroes’: problems with media focus on heroism from healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Ethics. 2020;46(8):510–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.OSHA. Healthcare. Available from: https://www.osha.gov/healthcare

- 3.Rai R, et al. Exposure to occupational hazards among health care workers in low-and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.BLS. Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities. 2022; Available from: https://www.bls.gov/web/osh/table-1-industry-rates-national.htm

- 5.OSHA. Worker Safety in Hospitals Caring for our Caregivers. Available from: https://www.osha.gov/hospitals/understanding-problem

- 6.Dembe AE, Delbos R, Erickson JB. Estimates of injury risks for healthcare personnel working night shifts and long hours. BMJ Qual Saf. 2009;18(5):336–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Che Huei L, et al. Occupational health and safety hazards faced by healthcare professionals in Taiwan: A systematic review of risk factors and control strategies. SAGE Open Med. 2020;8:2050312120918999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakr CJ, et al. Occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens among healthcare workers in a tertiary care center in Lebanon. Annals Work Exposures Health. 2021;65(4):475–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC. Stop Sticks campaign. 2019; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nora/councils/hcsa/stopsticks/bloodborne.html#:~:text=Bloodborne%20pathogens%20and%20workplace%20sharps,care%20workers%20are%20at%20risk

- 10.Kim WJ, Jeong BY. Exposure time to Work-Related hazards and factors affecting musculoskeletal pain in nurses. Appl Sci. 2024;14(6):2468. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Önal Ö et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of verbal and physical violence against healthcare workers in the Eastern mediterranean region. East Mediterr Health J, 2023. 29(10). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Mengistu DA, Tolera ST, Demmu YM. Worldwide prevalence of occupational exposure to needle stick injury among healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2021;2021(1):9019534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis KG, Kotowski SE. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders for nurses in hospitals, long-term care facilities, and home health care: a comprehensive review. Hum Factors. 2015;57(5):754–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medeni I, Alagüney ME, Medeni V. Occupational injuries among healthcare workers: a nationwide study in Turkey. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1505331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chau N, et al. Relationships of job, age, and life conditions with the causes and severity of occupational injuries in construction workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2004;77:60–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.da Costa RdC, Pires de Novais MA, Zucchi P. Notifications of work-related injuries and diseases: an observational study on a mining disaster. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith CK, Williams J. Work related injuries in Washington State’s trucking industry, by industry sector and occupation. Accid Anal Prev. 2014;65:63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fordyce TA, et al. An analysis of fatal and non-fatal injuries and injury severity factors among electric power industry workers. Am J Ind Med. 2016;59(11):948–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Group WB. Lebanon Overview: Development news, research, data. 2022; Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/lebanon/overview#:~:text=GDP%20per%20capita%20dropped%20by,income%20status%20in%20July%202022

- 20.Khairallah GM et al. Establishing an Employee Assistance Program at a Tertiary Healthcare Center in a Time of Multiple Crises: The Experience of the American University of Beirut Medical Center. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health: pp. 1–11.

- 21.Tadros A, et al. Emergency department visits for work-related injuries. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(8):1455–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santana VS, et al. Severity of occupational injuries treated in emergency services. Rev Saude Publica. 2009;43:750–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gravseth HM, Lund J, Wergeland E. Occupational injuries in Oslo: a study of occupational injuries treated by the Oslo emergency ward and Oslo ambulance service. Tidsskrift Den Norske Laegeforening: Tidsskrift Praktisk Medicin Ny Raekke. 2003;123(15):2060–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rey-Merchán MdC, López-Arquillos A. Rey-Merchán. Characteristics of occupational injuries among Spanish nursing workers. Healthcare. MDPI; 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Hawkins D, Chavarria AL. Fatal injuries in the health care and social assistance industry, census of fatal occupational injuries, 2011 to 2019. J Occup Environ Med. 2023;65(2):167–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grandjean CK, et al. Severe occupational injuries among older workers: demographic factors, time of injury, place and mechanism of injury, length of stay, and cost data. Nurs Health Sci. 2006;8(2):103–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoesz B, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of non-fatal work-related injuries among older workers: A review of research from 2010 to 2019. Saf Sci. 2020;126:104668. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bravo G, et al. Do older workers suffer more workplace injuries? A systematic review. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2022;28(1):398–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooke CE, Stephens JM. Clinicconomic, and humanistic burden of needlestick injuries in healthcare workers. Med Devices: Evid Res, 2017: pp. 225–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Prüss-Üstün A, Rapiti E, Hutin Y. Estimation of the global burden of disease attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among health‐care workers. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48(6):482–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson SE, Meade BJ. Potential health effects associated with dermal exposure to occupational chemicals. Environ Health Insights. 2014;8:EHI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horwitz IB, McCall BP. The impact of shift work on the risk and severity of injuries for hospital employees: an analysis using Oregon workers’ compensation data. Occup Med. 2004;54(8):556–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gupta M, Bandyopadhyay S. Regulatory and road engineering interventions for preventing road traffic injuries and fatalities among vulnerable road users in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Front Sustainable Cities. 2020;2:10. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson K et al. Manual patient handling in the healthcare setting: a scoping review. Physiotherapy, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Davis KG, et al. Workers’ compensation costs for healthcare caregivers: home healthcare, long-term care, and hospital nurses and nursing aides. Am J Ind Med. 2021;64(5):369–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fagan KM, Hodgson MJ. Under-recording of work-related injuries and illnesses: an OSHA priority. J Saf Res. 2017;60:79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon S, Lee SJ. Underreporting of work-related low back pain among registered nurses: A mixed method study. Am J Ind Med. 2023;66(11):952–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collaborators GORF. Global and regional burden of disease and injury in 2016 arising from occupational exposures: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77(3):133–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Hajj S, et al. History of injury in a developing country: a scoping review of injury literature in Lebanon. J Public Health. 2021;43(1):e24–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Debelu D, et al. Occupational-related injuries and associated risk factors among healthcare workers working in developing countries: a systematic review. Health Serv Res Managerial Epidemiol. 2023;10:23333928231192834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Safe. Patient Handling Available from: https://www.osha.gov/healthcare/safe-patient-handling

- 42.About the Total Worker Health® Approach. 2024; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/about/index.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the Open Science Framework repository: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2HFQX.