Abstract

Flow cytometry analysis of lymphocyte subset markers was performed for a group of sexually active, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative adolescents over a 2-year period to establish normative data. Data were collected in the REACH Project (Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health), a multicenter, longitudinal study of HIV-positive and high-risk HIV-negative adolescents. Two- and three-color flow cytometry data were collected every 6 months for these subjects. We determined the effects of gender, race, and age on the following lymphocyte subset markers: total CD4+ cells, CD4+ naïve cells, CD4+ memory cells, all CD8+ cells, CD8+ naïve cells, CD8+ memory cells, CD16+ natural killer cells, and CD19+ B cells. Gender was the demographic characteristic most frequently associated with differences in lymphocyte subset measures. Females had higher total CD4+ cell and CD4+ memory cells counts and lower CD16+ cell counts than males. Age was associated with higher CD4+ memory cell counts as well as higher CD8+ memory cell counts. For CD19+ cells, there was an interaction between age and gender, with males having significantly lower CD19+ cell counts with increasing age, whereas there was no age effect for females. Race and/or ethnicity was associated with differences in total CD8+ cell counts and CD8+ memory cell counts, although both of these associations involved an interaction with gender.

The interaction between infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and immunologic responses to infection has led to the development of new and more detailed laboratory methods. There are limited normative data available for immunologic assays and flow cytometry measures, especially for specific age populations, such as adolescents. Adolescence is a unique period of development, characterized by profound physiologic and psychosocial changes (19). Gender and age differences in immunologic cell numbers and function have been observed for both healthy and diseased subjects. Studies of adolescents and adults have demonstrated gender differences as well as some age differences in immune cell counts as characterized by flow cytometry studies and limited number of functional assays (2, 21, 22).

Age may be an important factor influencing immunologic responses to infection, especially in younger children (4, 8).Other factors, including race and genetic characteristics, may also influence immunologic cell numbers. Understanding how these factors influence the immune system in healthy individuals is key to beginning to understand age, gender, and race differences in immune system-based diseases and the adolescent's immunologic response to infection with HIV and other infectious agents.

HIV infection is a major issue confronting adolescents (17). Recent data show marked increases in the number of HIV infections in adolescents and young adults, especially in the number of infections due to heterosexual transmission in young women and in the number due to male-to-male transmission in young men (3, 23). The REACH (Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health) Project of AMHARN (The Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network) recruited and longitudinally followed a cohort of high-risk youths not infected with HIV to establish normative data for this population (15, 24). The study set out to establish gender, age, and racial differences in a set of immunologic markers in a longitudinal analysis. Before comparisons can be made for HIV-infected adolescents, normative data must be established for groups related to age, race and/or ethnicity, and gender. We present data for a group of phenotypic markers in an HIV-negative adolescent cohort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The REACH Project recruited HIV-positive and high-risk HIV-negative adolescents (age range, ≥13 to <19 years) into a study of biomedical and behavioral features of HIV infection as observed while under medical care for HIV infection and adolescent health. The HIV-negative subjects served to establish adolescent normative data for a number of biological measures. HIV-negative subjects were recruited from adolescent clinics serving high-risk adolescents based on the high seroprevalence rates in the geographic areas and on sexual risk or needle-using risk of the adolescents. The characteristics of the cohort, recruitment and eligibility criteria, and study design have been reported elsewhere (14, 24). The HIV-negative subjects were determined to be so on the basis of results from an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) performed within 30 days of enrollment into the REACH study. The HIV ELISA was repeated annually to confirm HIV-negative status. The HIV-negative youth, to qualify for enrollment into the study, had a history of either sexual intercourse or injection drug use.

Blood samples for HIV-negative subjects were collected at 15 clinical sites every 6 months (see Appendix). The following flow markers were analyzed, along with an automated differential count, at a local AIDS Clinical Trials Group-certified laboratory: CD3+/CD4+ (helper T cell), CD3+/CD8+ (suppressor and/or cytotoxic T cell), CD3−/CD56+/CD16+ (natural killer cell), and CD19+ (total B cell). Additional flow markers were analyzed centrally at the Immunology Core Laboratory at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, as previously reported (5, 6). These markers included the following cell subsets: CD4+/CD45RO−/CD45RA+ (naïve helper cell), CD4+/CD45RO+/CD45RA− (memory helper cell), CD8+/CD45RO−/CD45RA+ (naïve suppressor cell), and CD8+/CD45RO+/CD45RA− (memory suppressor cell).

A cross-sectional analysis of 192 subjects by two-sided tests with a type I error of 5% and a power of 80% can identify a standardized effect of 0.20, considered small, or a correlation of 0.20. Repeated analyses, with subject's age at the data collection visit as the time variable, were performed using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) software (SAS software, version 8.1; [SAS Institute]). P values of 0.05 or less were considered significant for two-sided tests. Multiple comparison corrections were not used. Summary statistics for cell counts are presented as means and standard deviations, which include only one observation per subject in each age category, although individual subjects may have contributed to more than one age category. For analysis, counts were log-transformed to make skewed distributions more nearly normal, as assessed by the Shapiro-Wilks test. Separately for each lymphocyte subset, GEE models were used to regress log counts on gender, subject's present age, and race and/or ethnicity of these HIV-negative subjects. The three two-way interactions of the demographic variables were also examined; models with interactions also retained main effects. Because multiple visits in the same age category were included, these GEE models used more data than appear in the summary of means and standard deviations.

RESULTS

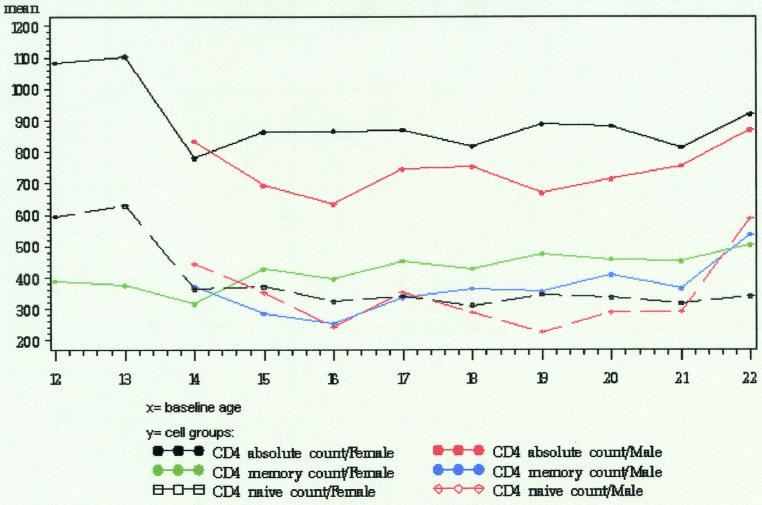

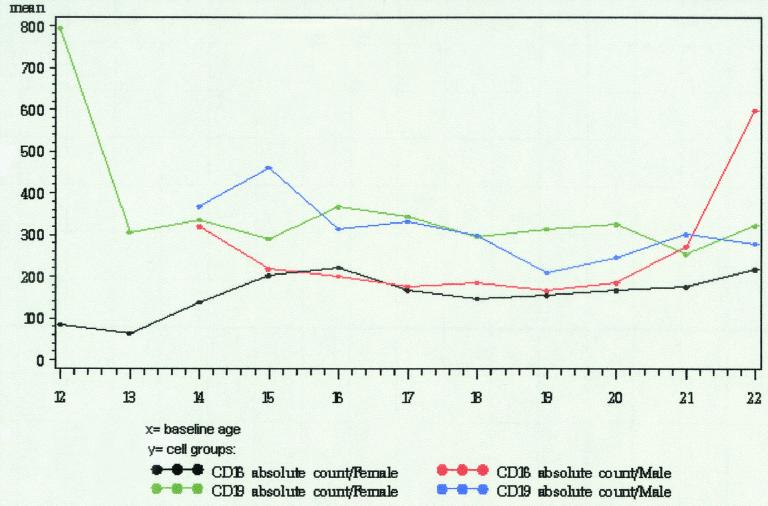

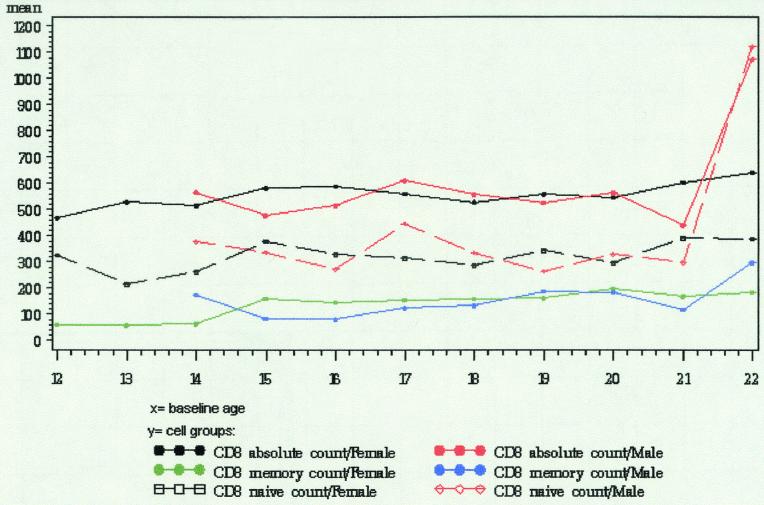

At the time of this analysis, 198 HIV-negative subjects were enrolled in the REACH cohort. Two HIV-negative transgender males were excluded and 4 subjects did not have a complete lymphocyte subset panel evaluation performed, leaving 192 subjects eligible for analysis. The demographic characteristics of the eligible subjects are shown in Table 1. For each eligible subject, all study visits at which a complete lymphocyte subset panel evaluation had been performed were included in the analysis. The total number of study visits included was 779, with one to nine visits per subject. The distribution of ages at the times the visits were made is also shown in Table 1. The means and standard deviations by gender and age for each of the eight subsets are provided in Table 2. Figures 1 to 3 are a graphical display of means by gender and age.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the cohort

| Characteristic | No. of subjects | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 147 | 77.0 |

| Male | 45 | 23.0 |

| Race | ||

| African-American, not Hispanic | 121 | 63 |

| Hispanic | 43 | 22 |

| Other | 28 | 15 |

| Age at first visit (yr) | ||

| 12 | 1 | 0.5 |

| 14 | 7 | 3.7 |

| 15 | 28 | 14.6 |

| 16 | 44 | 22.9 |

| 17 | 49 | 25.5 |

| 18 | 63 | 32.8 |

| No. of visits (females) by agea: | ||

| 12 | 1 | 0.2 |

| 13 | 2 | 0.3 |

| 14 | 7 | 1.2 |

| 15 | 35 | 5.9 |

| 16 | 74 | 12.5 |

| 17 | 126 | 21.4 |

| 18 | 164 | 27.8 |

| 19 | 108 | 18.3 |

| 20 | 52 | 8.9 |

| 21 | 18 | 3.1 |

| 22 | 3 | 0.5 |

| Total | 590 | 100 |

| No. of visits (males) by agea: | ||

| 14 | 4 | 2.1 |

| 15 | 9 | 4.8 |

| 16 | 18 | 9.5 |

| 17 | 34 | 18.0 |

| 18 | 55 | 29.1 |

| 19 | 41 | 21.7 |

| 20 | 18 | 9.5 |

| 21 | 8 | 4.2 |

| 22 | 2 | 1.1 |

| Total | 189 | 100 |

| Total | 192 | 100 |

Ages are given in years.

TABLE 2.

Mean counts (and standard deviations) of lymphocyte subsets by gender and age

| Lymphocyte subset and age (yr) | Value for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males

|

Females

|

|||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |

| Total CD4+ cells | ||||||

| 14 | 3 | 833 | 143 | 5 | 779 | 243 |

| 15 | 6 | 692 | 202 | 27 | 862 | 295 |

| 16 | 13 | 632 | 107 | 55 | 866 | 287 |

| 17 | 22 | 745 | 293 | 83 | 869 | 269 |

| 18 | 36 | 753 | 207 | 108 | 817 | 273 |

| 19 | 23 | 668 | 177 | 71 | 887 | 290 |

| 20 | 11 | 712 | 192 | 35 | 881 | 319 |

| 21 | 5 | 753 | 184 | 13 | 813 | 193 |

| CD4+ naïve cells | ||||||

| 14 | 2 | 444 | 160 | 3 | 364 | 200 |

| 15 | 6 | 352 | 153 | 19 | 372 | 178 |

| 16 | 9 | 243 | 114 | 40 | 323 | 142 |

| 17 | 18 | 354 | 185 | 80 | 342 | 163 |

| 18 | 35 | 291 | 128 | 99 | 311 | 166 |

| 19 | 23 | 227 | 109 | 69 | 345 | 158 |

| 20 | 11 | 288 | 114 | 34 | 335 | 157 |

| 21 | 5 | 289 | 145 | 13 | 318 | 122 |

| CD4+ memory cells | ||||||

| 14 | 2 | 373 | 63 | 3 | 316 | 46 |

| 15 | 6 | 286 | 73 | 19 | 426 | 137 |

| 16 | 9 | 252 | 59 | 40 | 396 | 148 |

| 17 | 18 | 336 | 168 | 80 | 453 | 167 |

| 18 | 35 | 366 | 130 | 99 | 429 | 145 |

| 19 | 23 | 355 | 116 | 69 | 476 | 179 |

| 20 | 11 | 407 | 148 | 34 | 458 | 158 |

| 21 | 5 | 363 | 201 | 13 | 450 | 134 |

| Total CD8+ cells | ||||||

| 14 | 3 | 566 | 169 | 5 | 515 | 249 |

| 15 | 6 | 476 | 190 | 27 | 582 | 230 |

| 16 | 13 | 515 | 226 | 55 | 589 | 311 |

| 17 | 22 | 610 | 465 | 83 | 559 | 264 |

| 18 | 36 | 558 | 288 | 108 | 528 | 260 |

| 19 | 23 | 527 | 281 | 71 | 559 | 229 |

| 20 | 11 | 563 | 272 | 35 | 545 | 240 |

| 21 | 5 | 439 | 180 | 13 | 604 | 189 |

| CD8+ naïve cells | ||||||

| 14 | 2 | 377 | 102 | 3 | 263 | 72 |

| 15 | 6 | 338 | 102 | 19 | 379 | 166 |

| 16 | 9 | 271 | 150 | 39 | 331 | 239 |

| 17 | 18 | 447 | 410 | 80 | 315 | 187 |

| 18 | 35 | 336 | 197 | 99 | 286 | 161 |

| 19 | 23 | 264 | 175 | 69 | 344 | 173 |

| 20 | 11 | 329 | 247 | 34 | 296 | 170 |

| 21 | 5 | 296 | 123 | 13 | 391 | 185 |

| CD8+ memory cells | ||||||

| 14 | 2 | 175 | 119 | 3 | 64 | 26 |

| 15 | 6 | 84 | 52 | 19 | 161 | 86 |

| 16 | 9 | 81 | 80 | 39 | 146 | 69 |

| 17 | 18 | 125 | 87 | 80 | 156 | 114 |

| 18 | 35 | 134 | 107 | 99 | 160 | 112 |

| 19 | 23 | 189 | 143 | 69 | 162 | 99 |

| 20 | 11 | 184 | 76 | 34 | 197 | 143 |

| 21 | 5 | 117 | 44 | 13 | 168 | 58 |

| CD16+ cells | ||||||

| 14 | 2 | 319 | 216 | 5 | 138 | 32 |

| 15 | 6 | 217 | 150 | 27 | 202 | 227 |

| 16 | 13 | 201 | 136 | 55 | 222 | 148 |

| 17 | 20 | 177 | 103 | 83 | 166 | 88 |

| 18 | 35 | 186 | 100 | 107 | 147 | 84 |

| 19 | 23 | 166 | 73 | 71 | 155 | 97 |

| 20 | 11 | 185 | 109 | 34 | 166 | 111 |

| 21 | 5 | 271 | 122 | 13 | 176 | 96 |

| CD19+ cells | ||||||

| 14 | 3 | 367 | 117 | 5 | 336 | 137 |

| 15 | 6 | 460 | 158 | 27 | 291 | 123 |

| 16 | 13 | 315 | 167 | 55 | 367 | 189 |

| 17 | 22 | 333 | 218 | 83 | 344 | 234 |

| 18 | 35 | 299 | 180 | 107 | 296 | 154 |

| 19 | 23 | 210 | 105 | 71 | 315 | 167 |

| 20 | 11 | 247 | 79 | 35 | 325 | 233 |

| 21 | 5 | 301 | 126 | 13 | 253 | 97 |

FIG.1.

Graphical representation of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets (CD4 cells) observed in adolescents.

FIG. 3.

Graphical representation of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets (CD16 and CD19 cells) observed in adolescents.

The significant statistical associations, by cell type, are shown in Table 3. There was a significant association with one or more of the demographic characteristics for 6 of the 8 lymphocyte subsets that were examined. No association with the three demographic characteristics was found for CD4+ naïve cells or for CD8+ naïve cells.

TABLE 3.

Significant associations between demographic characteristics and lymphocyte subsets, calculated by multivariate linear regression

| Lymphocyte subset | Covariate | Regression coefficienta | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total CD4+ | Female | 0.0734 | 0.0004 |

| CD4+ naïve | None | ||

| CD4+ memory | Female | 0.1296 | <0.0001 |

| Age | 0.0139 | 0.0097 | |

| Total CD8+ | Female | −0.1271 | 0.032 |

| Gender × raceb | 0.1901 | 0.011 | |

| CD8+ naïve | None | ||

| CD8+ memory | Age | 0.0228 | 0.018 |

| African-American | −0.3293 | 0.0002 | |

| Gender × racec | 0.3311 | 0.0016 | |

| CD16+ | Female | −0.0905 | 0.038 |

| CD19+ | Age | −0.0341 | 0.0001 |

| Age × genderd | 0.0254 | 0.0329 |

Value obtained by taking the log10 of cell counts.

African-American females have higher total CD8+ cell counts. No race effect was observed for males.

African-American males have lower CD8+ memory cell counts. No race effect was observed for females.

Males have lower CD19+ cell counts with increasing age. No age effect was observed for females.

Gender was the demographic characteristic most frequently associated with differences in lymphocyte subset counts. Gender had a significant main effect or interaction for 6 of the 8 subsets: total CD4+ cells, CD4+ memory cells, total CD8+ cells, CD8+ memory cells, CD16+ cells, and CD19+ cells. Females had higher total CD4+ cell counts, higher CD4+ memory cell counts, and lower CD16+ cell counts. For total CD8+ cells and CD8+ memory cells, there was an interaction between gender and race. African-American males had significantly lower total CD8+ counts than did other males; there was not a significant difference in total CD8+ counts by race for females, although African-American females had nearly significantly higher total CD8+ counts. For CD8+ memory cells, African-American and Hispanic males had higher mean counts than males classified as Caucasian or other, while African-American and Hispanic females had lower mean counts than females classified as Caucasian or other. None of these differences were statistically significant when data for males and females were modeled separately. For CD19+ cells, there was an interaction between gender and age. Males had significantly lower CD19+ cells counts with increasing age, whereas there was no age effect for females.

Age was associated with differences in three of the eight subsets: CD4+ memory cells, CD8+ memory cells, and CD19+ cells. Older subjects had higher CD4+ memory cell counts and higher CD8+ memory cell counts. The gender by age interaction for CD19+ cells is described in the preceding paragraph.

Race and/or ethnicity was associated with differences in only two of the eight subsets: total CD8+ cells and CD8+ memory cells. Both of these associations involved an interaction with gender, as was discussed above.

DISCUSSION

We have investigated the impact of gender, race, and age on T-lymphocyte subset populations as measured by flow cytometry in adolescents identified as at high risk for HIV infection in a national, longitudinal study. Gender was the demographic factor most frequently associated with differences in lymphocyte subsets. In females, we found higher CD 4+ T-lymphocyte counts and higher CD4+ memory T-lymphocyte counts, and lower CD 16+ T-lymphocyte counts than in males. Our study demonstrated some limited gender differences in CD8+ cells and CD19+ cells counts, but only with the influence of either race or age. Since this was a longitudinal study in a predominantly African-American and Hispanic group of adolescents, it serves as an important reference when studying disease processes that affect the immune system in the adolescent population.

Our data for CD4+ T lymphocyte differences by gender are consistent with those previously reported for minority and Caucasian adolescents. Bartlett and colleagues studied a group of minority youth and found higher levels (both totals and percentages) of CD4+ T lymphocytes in females than in males and lower levels of B cells in females than in males (2). In another study of primarily Caucasian adolescents from 12 to 19 years, Tollerud and colleagues found higher levels of CD4+ T lymphocytes in females than in males among older adolescents (21). Our studies demonstrate that much of this gender difference is mainly in the memory CD4+ T-cell subset. We did not find significantly higher B-cell levels in males than in females, as was found by Bartlett. There is no direct explanation for this; however, we had fewer adolescents in the younger age ranges, which may explain some of this difference. A number of studies have reported increases in CD4+ T cells in females (2, 12, 21, 22). Studies of adults have identified some similar gender differences. Higher mean total CD3+ T-cell and mean total CD4+ T-cell counts have been observed in females than in males; in addition, lower CD16+ cells have also been noted in adult females than in males (14, 18). Differences in immune cell numbers may be secondary to hormonal differences (androgens or estrogen or both).

Gender may affect the immune system at many levels. Differences in sex steroid regulation and production are present in males and females early in development, with the most profound differences noted during adolescence with the onset of puberty. Pubertal hormonal changes occur under the control of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, which leads to increases in sex hormone levels (16). Gender has an effect on both B- and T-cell responses and the secretion of immune modulators, including cytokines and chemokines (11). Cell proliferation occurs under the influence of cytokines, and some differences in T-cell numbers between males and females may be related to differences in cytokine regulation (9). Whether the increased levels of circulating CD4+ T cells found in females in this study is secondary to the influence of specific cytokines requires further investigation.

Sex hormones may influence the immune cell populations through several indirect pathways. Sex hormones may impact immune cell numbers through thymic pathways. Studies of castrated male mice demonstrate increased number of both CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells (7). In addition, evidence suggests that thymic involution is modulated by androgens (13). Sex hormones may also influence T cells directly through cell receptors for sex steroids, as has been found for CD8+ T cells (20).

During adolescence, the hormonal influence on immune cell numbers may be most apparent; however, the impact of sex hormones on immunity may begin much earlier. There are detectable estrogen receptors in fetal thymus as well as fetal lymphoblast cells, suggesting that sex hormones may influence lymphocyte maturation in the thymus (7). Whether the interactions between lymphocyte receptors and sex hormones lead to differences in immune cells numbers later in life is not clear. Gender differences in circulating T-cell subsets most likely reflect a complex regulatory mechanism, some of which may be under the influence of gender differences in sex steroids.

The impact of gender on the immune system is evident from gender differences in immune system diseases particularly autoimmune disorders. Systemic lupus erythematosis, rheumatoid arthritis, myasthenia gravis, and Hashimoto's disease all have a higher prevalence among women (1, 10).

We found no independent influences of race and/or ethnicity on any of the immunologic measures in our study. We are limited, however, by the relatively small numbers of Caucasion subjects in our cohort. Rates of new HIV infections in adolescents appear to be greatest in minority groups (3). Thus, racial or ethnic differences in immune responses would be important to determine in a more heterogeneous population.

We also found limited influence of age on the T-cells subsets studied with the only independent impact of age on memory CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells. Again, our study is limited by small numbers of younger adolescent subjects. Studies in younger children show a significant impact of age on T-cell populations, with signficantly higher numbers of CD4+ T lymphocytes in young infants (4). Differences between adolescents and adults have been reported: adolescent females begin to demonstrate CD4+ T-cell levels that are increased compared to those observed in males, and females also begin to demonstrate CD8+ T cell levels that are lower (such levels in adults have also been reported) (21, 22). Our numbers may be too small to demonstrate subtle differences in the transition from adolescence to adulthood.

Our study is unique as a longitudinal analysis of gender, age, and race and/or ethnicity differences in specific immunologic cells in high-risk youth. Although we found some significant differences, our study has several limitations. First, as most of our youth were sexually mature at the time of entry into the study, we were unable to analyze the data by Tanner-stage subgroups. Second, the mechanisms leading to gender differences were beyond the scope of this study. Finally, our population was primarily minority; thus, the findings may not apply to all populations. However, understanding the impact of gender, race, and age on immune cell numbers in healthy individuals is essential for subsequent evaluation in disease states.

FIG. 2.

Graphical representation of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets (CD8 cells) observed in adolescents.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the members of the Community Advisory Board for their insight and counsel and particularly indebted to the youth who are making this study happen.

The Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network is supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with supplemental funding from the National Institutes on Drug Abuse, Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Mental Health and the Health Resources and Services Administration. Network operations and analytic support are provided by C. M. Wilson, C. Partlow (University of Alabama at Birmingham), S. J. Durako, J. H. Ellenberg, B. Hobbs, A. Bennett, M. Camarca, K. Clingan, J. Houser, V. Junankar, O. Leytush, L. Muenz, Y. Ma, R. Mitchell, T. Myint, P. Ohan, L. Paolinelli, M. Rakheja, M. Sarr, and A. Soloviov (Westat, Inc.).

APPENDIX

The following investigators, listed in order by the numbers of subjects enrolled at their respective clinics, are participating in this study: L. Friedman, L. Pall, D. Maturo, A. Pasquale (University of Miami); D. Futterman, D. Monte, M. Alovera-DeBellis, N. Hoffman, and S. Jackson (Montefiore Medical Center); D. Schwarz and coauthor B. Rudy (University of Pennsylvania and the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia); M. Tanney and A. Feldman (Children's Hospital of Philadelphia); M. Belzer, D. Tucker, C. Hosmer, K. Chung (Children's Hospital of Los Angeles); S. E. Abdalian, L. Green, C. McKendall, and L. Wenthold (Tulane Medical Center); L. J. D'Angelo, C. Trexler, C. Townsend-Akpan, R. Hagler, and J. A. Morrissy (Children's National Medical Center); L. Peralta, C. Ryder, S. Miller, and S. Calianno (University of Maryland); L. Henry-Reid and R. Camacho (Cook County Hospital/University of Chicago); M. Sturdevant, A. Howell, and J. E. Johnson (Children's Hospital, Birmingham); A. Puga, D. Cruz, and P. McLendon (Children's Diagnostic and Treatment Center); M. Sawyer, J. Tigner, and A. Simmonds (Emory University); P. Flynn, K. Lett, J. Dewey, S. Discenza (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital); L. Levin and M. Geiger (Mt. Sinai Medical Center); P. Stanford and F. Briggs (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey); and J. Birnbaum, M. Ramnarine, and V. Guarino (SUNY Health Science Center at Brooklyn). The following investigators have been responsible for the basic science agenda: C. Holland (Center for Virology, Immunology, and Infectious Disease, Children's Research Institute, Children's National Medical Center), A. B. Moscicki (University of California at San Francisco), D. A. Murphy (University of California at Los Angeles); S. H. Vermund (University of Alabama at Birmingham); P. Crowley-Nowick (The Fearing Laboratory, Brigham and Women's Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass.), coauthor S. D. Douglas (University of Pennsylvania and the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia). Staff from sponsoring agencies include A. Rogers and A. Willoughby, (NICHD), K. Davenny and V. Smeriglio (NIDA), E. Matzen, (NIAID), B. Vitiello (NIMH).

REFERENCES

- 1.Athreya, B. H., J. Pletcher, F. Zulian, D. B. Weiner, and W. V. Williams. 1993. Subset-specific effects of sex hormones and pituitary gonadotropins on human lymphocyte proliferation in vitro. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 66:201-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartlett, J. A., S. J. Schleifer, M. K. Demetrikopoulos, B. R. Delaney, S. C. Shiflett, and S. E. Keller. 1998. Immune function in healthy adolescents. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 5:105-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2000. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, vol. 11, p. 1-44. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.

- 4.Denny, T., R. Yogev, R. Gelman, C. Skuza, J. Oleske, E. Chadwick, S. Cheng, and E. Connor. 1992. Lymphocyte subsets in healthy children during the first 5 years of life. JAMA 267:1481-1488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douglas, S. D., B. J. Rudy, L. Muenz, A. B. Moscicki, C. M. Wilson, C. Holland, P. Crowley-Nowick, S. H. Vermund, and the Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network. 1999. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell markers in antiretroviral therapy-naive HIV-infected and high risk seronegative adolescents. AIDS 13:1629-1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Douglas, S. D., B. Rudy, L. Muenz, S. E. Starr, D. E. Campbell, C. M. Wilson, C. Holland, P. Crowley-Nowick, S. H. Vermund, and the Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network. 2000. T-lymphocyte subsets in HIV-infected and high-risk HIV-uninfected adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 154:375-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossman, C. 1989. Possible underlying mechanisms of sexual dimorphism in the immune response, fact and hypothesis. J. Steroid Biochem. 34:241-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotylo, P. K., N. S. Fineberg, K. S. Freeman, N. L. Redmond, and C. Charland. 1993. Reference ranges for lymphocyte subsets in pediatric patients. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 100:111-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lahita, R. G. 2000. Gender and the immune system. J. Gender-Specific Med. 3:19-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lahita, R. G. 1987. Sex and age in ystemic lupus erythematosus, p. 523-529. In R. G. Lahita (ed.), Systemic lupus erythematosus. Wiley Medical, New York, N.Y.

- 11.McMurray, R. W., R. W. Hoffman, W. Nelson, and S. E. Walker. 1997. Cytokine mRNA expression in the B/W mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus—analyses of strain, gender, and age effects. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 84:260-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller, D., M. Chen, A. Vikingsson, D. Hildeman, and K. Peder. 1995. Oestrogen influences CD4+ T-lymphocyte activity in vivo and in vitro in β2-microglobulin-deficient mice. Immunology 86:162-167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen, N. J., S. M. Viselli, J. Fan, and W. J. Kovacs. 1998. Androgens accelerate thymocyte apoptosis. Endocrinology 139:748-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reichert, T., M. DeBruyere, V. Deney, T. Totterman, P. Lydyard, F. Yuksel, H. Chapel, D. Jewell, L. Van Hove, J. Linden, and L. Buchner. 1991. Lymphocyte subset reference ranges in adult caucasians. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 60:190-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers, A. S., D. Futterman, A. B. Moscicki, C. M. Wilson, J. Ellenberg, and S. H. Vermund. 1998. The REACH Project of the Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network: design, methods, and selected characteristics. J. Adolesc. Health 22:300-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Root, A. W. 1973. Endocrinology of puberty. I. Normal sexual maturation. J. Pediatr. 83:1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rotheram-Borus, M. J., and D. Futterman. 2000. Promoting early detection of HIV infection among adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 154:435-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santagostino, A., G. Gargaccio, A. Pistorio, V. Bolis, G. Camisasca, P. Pagliaro, and M. Girotto. 1999. An Italian national multicenter study for the definition of a reference ranges for normal values of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets in healthy adults. Haematologica 84:499-504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slap, G. B. 1986. Normal physiological and psychosocial growth in the adolescent. J. Adolesc. Health. 7:13S-23S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stimson, W. H. 1988. Estrogen and human T lymphocytes: presence of specific receptors in the T-suppressor/cytotoxic subset. Scand. J. Immunol. 28:345-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tollerud, D. J., S. T. Ildstad, L. M. Brown, J. W. Clark, W. A. Blattner, D. L. Mann, C. Y. Neuland, L. Pankiw-Trost, and R. N. Hoover. 1990. T-cell subsets in healthy teenagers: transition to the adult phenotype. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 56:88-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tollerud, D. J., J. W. Clark, L. Morris Brown, C. Y. Neuland, L. K. Pankiw-Trost, W. A. Blattner, and R. N. Hoover. 1989. The influence of age, race, and gender on peripheral blood mononuclear-cell subsets in healthy nonsmokers. J. Clin. Immunol. 9:214-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valleroy, L. A., D. A. MacKellar, J. M. Karon, D. H. Rosen, W. McFarland, D. A. Shehan, S. R. Stoyanoff, M. LaLota, D. D. Celentano, B. A. Koblin, H. Thiede, M. H. Katz, L. V. Torina, and R. S. Janssen. 2000. HIV prevalence and associated risks in young men who have sex with men. JAMA 284:198-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson, C. M., J. Houser, C. Partlow, B. J. Rudy, D. Futterman, L. B. Friedman, and the Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network. 2001. The REACH (Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health) Project: study design, methods, and population profiles. J. Adolesc. Health 298S:8-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]