Abstract

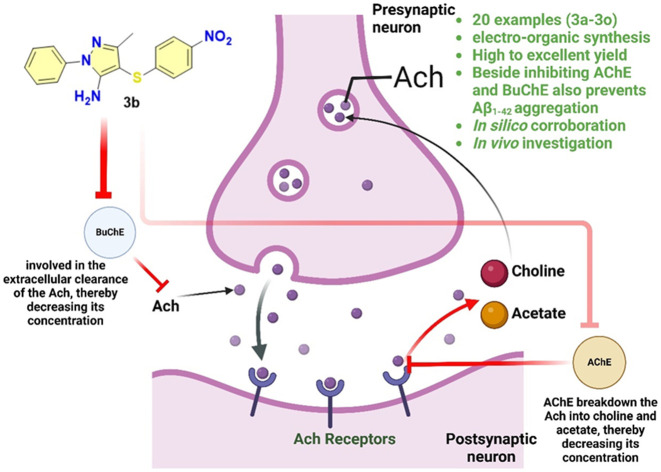

Current therapeutic regimens approved to treat Alzheimer's disease (AD) provide symptomatic relief by replenishing the acetylcholine levels in the brain by inhibiting AChE. However, these drugs don't halt or slow down the progression of Alzheimer's disease, which remains a major challenge. Evidence suggests a significant increase in BuChE activity with a decrease in AChE activity as the AD progresses along with the Aβ1–42 aggregation. To address this unmet need, we rationally developed sulfenylated 5-aminopyrazoles (3a–3o) via electro-organic synthesis in good to excellent yields (68–89%) and duly characterized them using spectrophotometric techniques. The compounds were tested for acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) inhibition, with 3b (4-NO2) showing the highest potency. It exhibited IC50 values of 1.634 ± 0.066 μM against AChE and 0.0285 ± 0.019 μM against BuChE, outperforming donepezil and tacrine. Admittedly, 3b effectively inhibited Aβ1–42 aggregation and enhanced working memory, as indicated by the Y-maze test, besides portraying no cytotoxicity. The outcome was further corroborated using in silico techniques, leading to the elucidation of plausible inhibition and metabolism mechanisms.

Sulfenylated amino pyrazoles: inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase.

1. Introduction

The risk and incidence of neurodegenerative diseases increases with age, and Alzheimer's disease (AD) is among the most prevalent age-related conditions.1 A hallmark of Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the decline in acetylcholine levels.2 According to reports from the Alzheimer's association, it is projected that by 2024, AD will impact 6.9 million Americans aged 65 and older.3,4 The disease is characterized by a progressive decline in cognitive function, beginning with mild memory loss and progressing to severe impairment, significantly impacting daily life and interactions.5–7 The disease is marked by crucial pathological features: β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tau tangles (NFTs), which are central to the cognitive decline observed in patients.8–10 The cognitive impairments associated with Alzheimer's disease (AD) are fundamentally linked to the degeneration of neurons and synapses, especially in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex.11 In addition to these hallmark features, AD involves the degeneration of cholinergic neurons and increased activity of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE).12–14 AChE is primarily found in neuronal tissues that include the brain and neuromuscular junction, whereas BuChE is predominantly found in the liver and plasma, including the brain.15,16 AChE, in particular, is associated with the hydrolysis of acetylcholine. At the same time, BuChE is related to the hydrolysis of broader substrates, which primarily include butyrylcholine, and plays a vital role in acetylcholine hydrolysis, too.17,18 The levels of AChE and BuChE are frequently upregulated in AD.19 Apart from this, a fascinating fact is that BuChE is found to compensate for the decline in AChE activity.20,21 This leads to failure and imparts resistance to the AChE inhibitors employed to treat AD by preventing the degradation of acetylcholine levels.22,23 This is further complicated by oxidative stress, chronic neuro-inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and imbalances in calcium and metals.24–26 To treat such conditions, the USFDA has approved numerous small molecules (Fig. 1). The current pharmacological interventions, such as donepezil and rivastigmine, can partially overcome AD symptoms by enhancing acetylcholine levels in the brain through inhibiting acetylcholinesterase (AChE). However, these therapies don't impede or slow down the progression of Alzheimer's disease, presenting a significant challenge. Regarding the pathophysiology of these targeted enzymes, AChE plays a substantial role in regulating acetylcholine; however, several reports also suggest an increase in BuChE activity significantly, which decreases the AChE activity upon the progression of AD.27,28 Additionally, Aβ1–42 aggregation, a hallmark of AD progression, is characterized by the neurotoxic plaque formation that disrupts neuronal function. In such a scenario, developing a multifunctional inhibitor of AChE and BuChE with a profound effect on Aβ1–42 aggregation inhibition could be a comprehensive therapeutic approach to address the unmet therapeutic needs in AD more effectively.29 These drugs would have the potential to not only improve the cognitive symptoms but also address neuro-inflammation holistically, slowing down the AD progression.

Fig. 1. Chemical structure of key approved cholinesterase inhibitors.

In response to this unmet need, the present manuscript outlines the synthesis of sulfenylated 5-aminopyrazoles and explores their potential as AChE and BuChE inhibitors. Additionally, we also explored their implication for Aβ1–42 aggregation inhibition. We established their utility as triple inhibitors via a plethora of in vitro and in vivo investigations to treat AD. The molecules were synthesized utilizing greener synthetic approaches, specifically employing an electro-organic synthetic methodology for the sulfenylation of aminopyrazoles.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Drug design

The molecules were rationally designed to consider the pharmacophoric features of FDA-approved drugs, donepezil and tacrine (revoked from the approved list), against AChE and BuChE, respectively. For AChE inhibitor development, an HHRR-based (Fig. 2) pharmacophore was generated using the Phase module of the Schrodinger software utilizing the 3D structure of donepezil bound to the AChE protein (PDB code: 4EY7).30 The model generated was HHRR (BEDROC160.9 score: 0.943), comprising two hydrophobic groups (H) and two aromatic ring systems (R). Based on our synthetic chemistry background, we rationally designed 4-(phenylthio)-1H-pyrazoles, considering ‘3a’ as a prototype molecule from the proposed series of inhibitors. We superimposed it with the generated pharmacophoric model (Fig. 2A). The prototype molecule 3a aligns well with the generated pharmacophore model of donepezil at the binding site of AChE, providing great scope for further exploration of anticholinesterase biochemical and biological activity. We were further interested if our proposed molecules could demonstrate additional inhibitory activities against BuChE, facilitating the development of dual inhibitors, targeting both AChE and BuChE. In this context, we generated the pharmacophore model of the FDA-approved drug tacrine bound to BuChE (PBD code: 4BDS).31 The generated pharmacophore DHRR (BEDROC 160.9 score: 0.715) comprises a hydrogen bond donor (D) and a hydrophobic group (H) followed by two hydrogen bond acceptors (R). Our prototype molecule of series 3a was further examined to see if it aligns with the pharmacophoric features of tacrine. It was found that molecule 3a not only satisfies the prerequisite of the DHRR model but also possesses an additional aromatic ring that can potentially improve the binding affinity with BuChE through lipophilic interactions (Fig. 2B). The overall pharmacophore-based superposition thus provides a strong basis for the dual inhibition of AChE and BuChE by the 4-(phenylthio)-1H-pyrazole-based rationally designed inhibitors. This aspect is further explored in detail in the following sections and is well corroborated by the biological and in silico studies.

Fig. 2. Drug design strategy for the development of (A) AChE inhibitors and (B) BuChE inhibitors.

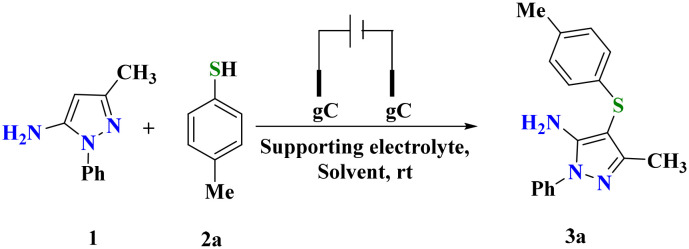

2.2. Chemistry

We initiated the present study with reaction optimization using amino pyrazole (1) (0.28 mmol) and p-methyl-thiophenol (2a) (0.30 mmol) as model substrates. The selected molar ratio of both substrates was dissolved in acetonitrile and stirred at 25 °C for 2 h (Table 1, entry 1). The failure of the reaction to yield the desired product even after 2 h of reaction run was evidenced. The reaction subsequently assessed by incorporating KI (100 mol%) also failed, as both reactants remained unreacted (Table 1, entry 2). The same reaction was then investigated with electro-organic synthesis using glassy carbon electrodes as both the anode and cathode at 20 mA, which resulted in a positive reaction outcome (Table 1, entry 3). The reaction mixture was poured into ice-cold water and subsequently extracted with ethyl acetate and purified over silica gel using a Buchi pure flash chromatograph to afford 85% of the pure product, which was characterized as 3-methyl-1-phenyl-4-(4-tolylthio)-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3a) using spectroscopic analysis. In the IR spectrum of 3a, the absorption peaks recorded at 3306 and 1595 cm−1 were assigned to N–H and C C stretching, respectively. A peak due to C–S stretching was recorded at 704 cm−1. Similarly, the 1H NMR spectrum of 3a displayed seven sets of signals due to symmetrically non-equivalent protons. Two singlets at δH 2.24 and 2.06 ppm were recorded and assigned to the methyl protons attached to phenyl and pyrazole nuclei, respectively. The aromatic protons resonate as two multiplets ranging between δH 7.62 and 6.96 ppm. The singlet at δH 5.62 ppm was attributed to –NH2 protons, which was also confirmed through D2O exchange. The proton decoupled 13C spectrum 3a displayed thirteen signals due to thirteen non-equivalent carbon atoms. Finally, the overall composition of 3a was confirmed by ESI HRMS analysis. A peak due to the [M + H]+ ion was observed at 296.1225 (m/z calcd. for C17H17N3S: 295.1143) (Fig. S1–S4†).

Table 1. Screening of the electro-organic C–S bond formation reaction using different conditionsa.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. no | Reagent (equiv.) | Reaction medium | Time (h) | Current (mA) | Yield (%) |

| 1. | — | CH3CN | 2 | NR | |

| 2. | KI (1) | CH3CN | 2 | NR | |

| 3. | KI (1) | CH3CN | 2 | 20 | 85 |

| 4. | n-Et4NClO4 (1) | CH3CN | 2 | 20 | 15b |

| 5. | n-Et4NBF4 (1) | CH3CN | 2 | 20 | 12b |

| 6. | n-Bu4NBF4 (1) | CH3CN | 2 | 20 | 13b |

| 7. | LiClO4 (1) | CH3CN | 2 | 20 | 15b |

| 8. | TMAI (1) | CH3CN | 2 | 20 | 50 |

| 9. | TBAB (1) | CH3CN | 2 | 20 | 40b |

| 10. | TBAI (1) | CH3CN | 2 | 20 | 70 |

| 11. | KI (1) | MeOH | 2 | 20 | 71 |

| 12. | KI (1) | H2O | 2 | 20 | 10b |

| 13. | KI (0.5) | CH3CN | 2 | 20 | 87 |

| 14. | KI (0.2) | CH3CN | 2 | 20 | 75 |

| 15. | KI (0.1) | CH3CN | 2 | 20 | 70 |

| 16. | KI (0.2) | CH3CN | 2 | 15 | 75 |

| 17. | KI (0.2) | CH3CN | 2 | 25 | 85 |

| 18. | — | CH3CN | 2 | 20 | 10b |

Optimized reaction conditions: 1 (0.28 mmol), 2a (0.30 mmol), KI (50 mol%), undivided cell, glassy carbon electrodes, constant current = 20 mA and CH3CN (5 mL).

Incomplete reaction.

After establishing the molecular geometry of 3a using different techniques, the reaction feasibility was then extended with a variety of electrolytes such as n-Et4NClO4, n-Et4NBF4, n-Bu4NBF4, LiClO4 and tetra alkyl ammonium salts of iodine and bromide (TMAI, TBAB and TBAI) (Table 1, entries 4–10). The reaction resulted in a reduced product yield or incomplete reactions. The above observations established KI as an optimum electrolyte for the desired organic transformation. The utilization of a polar protic solvent didn't improve the reaction outcome substantially (Table 1, entries 11 and 12). Further, these results establish the importance of CH3CN in achieving a high reaction yield. With these encouraging results in hand, the catalytic loading of KI and the reaction current was also optimized (Table 1, entries 13–17). The role of KI in this electrochemical C–H functionalization was also investigated by reacting 1 and 2a in CH3CN in its absence (Table 1, entry 18). A yield of 10% indicates the potential utility of KI in catalysing this electro-organic synthesis. After a series of reactions using different electrolytes, the optimized reaction conditions yielded 87% of 3a in 2 h (Table 1, entry 13). Zhang et al.32 synthesized amino pyrazole based thioether derivatives using amino pyrazole and thiophenols as starting materials using Pt electrodes as electrodes, NH4BF4 as an electrolyte and NH4I as a mediator to afford the corresponding sulfenylated products in good yield. However, the method's efficiency is limited due to the use of expensive platinum electrodes, extended reaction times, and the presence of an additional mediator.

With these conditions, the developed protocol was validated with differently substituted thiophenols. The diverse set of substrates (2a–2o) reacted with 1 to yield 68–89% of sulfenylated products (3a–3o) (Scheme 1) (Fig. S5–S55†). Notably, thiols possessing an electron releasing group (–Me) resulted in the corresponding products 3a, 3l, 3m and 3o in 88, 75, 83 & 79% yields, respectively. Due to the steric effect, the methyl group substituted at the 2nd position of the phenyl ring (3l & 3o) resulted in lower yields than the substitution at the other positions. Electron withdrawing substitution (–NO2) at the phenyl ring of thiophenol was well-compatible under optimized conditions and afforded 78% of 3b. Moreover, meta and para halogen substituted thiols yielded desired products (3c, 3f, 3g, 3h & 3j) in 89, 85, 80, 81 & 80% yields, respectively. However, lower product yields was observed with ortho-bromo/chloro substituted thiols (3d, 3e & 3n) due to the prevailing ortho effect. Naphthalene thiol was also a compatible substrate offering 89% of the desired product. The molecular structure of the developed thiolated pyrazoles was established using spectral analysis. Moreover, the crystal structure of 3i was established, and the ORTEP diagram is presented in Fig. S56† (CCDC No. 2305521). An orthorhombic crystal system with the Pna21 space group was observed for the molecule in X-ray diffraction studies (Table S1†).

Scheme 1. Substrate scope for electroorgano-catalyzed sulfenylation of aminopyrazoles.a,b.

Reactions were conducted under controlled conditions using amino pyrazole (1) and thiophenol (2i) as substrates. Initially, a radical mechanism was established, as the reaction performed in the presence of TEMPO (5 eq.) yielded trace amount (10%) of 3i. The role of KI and electric current in reaction catalysis was already established during reaction optimization, as their absence resulted in a reduced yield and failed reactions, respectively. In another experiment, the reaction of 2i in the absence of 1 resulted in a 95% yield of diphenyl disulfide (4A) under otherwise identical conditions. The formation of 3i in a reaction between 4A and 1, performed under optimized conditions, establishes the intermediacy of 4A (Scheme S1†). Based on the outcome of the above-controlled experiments, a plausible mechanism for the reaction has been proposed. The reaction involves the oxidation of I− to I2, which then reacts with thiophenol (2i) to yield a thiophenol radical (4B). This radical subsequently reacts with amino pyrazole (1), yielding another radical intermediate (4D) that eventually converts into 3i (Scheme S1†).

2.3. Biological investigations

2.3.1. Inhibition of AChE and BuChE along with the modulation of oxidative stress

Following the synthesis, our main objective was to evaluate the implication of our synthetics for the inhibition of AChE and BuChE. The in vitro analysis of these enzymes revealed that among the pool of synthetics, compound 3b was observed to be the best one with IC50 values of 1.634 ± 0.066 and 0.0285 ± 0.019 μM for AChE and BuChE, respectively. Notably, compound 3b demonstrated a higher selectivity towards BuChE. Furthermore, the compound containing a dichlorophenyl-substituted pyrazole amine (3d) showed greater efficacy against BuChE with an IC50 of 0.575 ± 0.054 μM, while it was less effective on AChE (IC50 = 3.905 ± 0.091 μM). Compounds 3b and 3c showed stronger inhibition against AChE (IC50 = 1.920 ± 0.065 and 2.145 ± 0.095 μM, respectively) than 3d. Additionally, compounds 3h, 3l and 3m also displayed promising inhibition of both AChE and BuChE activity. The IC50 values for these compounds were as follows: 3h showed an AChE IC50 of 2.341 ± 0.082 μM and a BuChE IC50 of 6.842 ± 0.042 μM, 3l had an AChE IC50 of 1.928 ± 0.010 μM and a BuChE IC50 of 2.731 ± 0.042 μM, and 3m exhibited an AChE IC50 of 2.554 ± 0.012 μM and a BuChE IC50 of 0.952 ± 0.052 μM. The observed activity of these synthetics is likely due to the substituted pyrazole amine nucleus, which plays a crucial role in their interaction with the enzymes. On the other hand, compound 3o was found to have the weakest activity, likely due to the substitution of two bulky electron-donating groups on the phenyl ring, which may hinder its interaction with the target enzymes (Table 2). Next, oxidative stress is widely recognized as a key factor in the pathophysiology of AD. Small molecules with free radical scavenging properties have been reported to offer potential therapeutic benefits in managing AD. In light of this, the sulfenylated amino pyrazoles (3) were also evaluated for their antioxidant activity. To our delight, the analysis (Table 2) performed at 50 and 100 μM concentrations of the investigational compound revealed that among the tested compounds, 3b displayed % free radical scavenging activity of 17.24 ± 0.521 and 32.83 ± 0.139, respectively. However, compound 3d emerged as the most effective antioxidant within this series of compounds, exhibiting scavenging activities of 20.59 ± 0.318 and 42.41 ± 0.281% at 50 and 100 μM, respectively. In addition to these findings, compounds 3e, 3g and 3j also showed notable antioxidant activity. Specifically, compound 3e displayed 16.35 ± 0.522 and 33.13 ± 0.138% scavenging at 50 and 100 μM, respectively, compound 3g exhibited 17.28 ± 0.428 and 31.51 ± 0.411% at 50 and 100 μM, and compound 3j had 16.62 ± 0.252 and 33.24 ± 0.194% at 50 and 100 μM, respectively. These results suggest that certain compounds within this series, particularly compound 3d, possess potent anti-oxidant properties that may contribute to their potential efficacy in counteracting the oxidative stress associated with Alzheimer's disease.

Table 2. AChE and BuChE inhibition and antioxidant activity of synthesized compounds (3a–3o).

| Compounds | AChE IC50 ± SE (μM) | BuChE IC50 ± SE (μM) | Selectivity ratio | % Free radical scavenging, mean ± SE (μM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 μM | 100 μM | ||||

| 3a | 1.920 ± 0.065 | 0.865 ± 0.038 | 2.22 | 09.42 ± 0.291 | 19.43 ± 0.421 |

| 3b | 1.634 ± 0.066 | 0.0285 ± 0.019 | 57.33 | 17.24 ± 0.521 | 32.83 ± 0.139 |

| 3c | 2.145 ± 0.095 | 1.871 ± 0.074 | 1.15 | 15.41 ± 0.422 | 28.23 ± 0.420 |

| 3d | 3.905 ± 0.091 | 0.575 ± 0.054 | 6.79 | 20.59 ± 0.318 | 42.41 ± 0.281 |

| 3e | 8.633 ± 0.082 | 3.829 ± 0.065 | 2.25 | 16.35 ± 0.522 | 33.13 ± 0.138 |

| 3f | 27.27 ± 0.010 | 20.983 ± 0.069 | 1.30 | 14.42 ± 0.136 | 29.52 ± 0.361 |

| 3g | 14.73 ± 0.010 | 19.78 ± 0.010 | 0.74 | 17.28 ± 0.428 | 31.51 ± 0.411 |

| 3h | 2.341 ± 0.082 | 6.842 ± 0.042 | 0.34 | 15.19 ± 0.291 | 32.11 ± 0.220 |

| 3i | 15.37 ± 0.010 | 18.84 ± 0.013 | 0.82 | 07.31 ± 0.428 | 12.45 ± 0.310 |

| 3j | 8.397 ± 0.060 | 4.252 ± 0.029 | 1.97 | 16.62 ± 0.252 | 33.24 ± 0.194 |

| 3k | 15.033 ± 0.012 | 19.831 ± 0.042 | 0.76 | 05.13 ± 0.503 | 09.69 ± 0.352 |

| 3l | 1.928 ± 0.010 | 2.731 ± 0.042 | 0.71 | 07.52 ± 0.218 | 15.55 ± 0.153 |

| 3m | 2.554 ± 0.012 | 0.952 ± 0.052 | 2.68 | 05.92 ± 0.422 | 11.53 ± 0.213 |

| 3n | 6.042 ± 0.018 | 1.053 ± 0.026 | 5.74 | 12.34 ± 0.248 | 27.52 ± 0.520 |

| 3o | 16.74 ± 0.068 | 25.93 ± 0.033 | 0.65 | 14.83 ± 0.310 | 29.42 ± 0.351 |

| Donepezil | 2.019 ± 0.068 | 17.38 ± 0.028 | 0.12 | — | — |

| Tacrine | 29.84 ± 0.04 | 28.49 ± 0.02 | — | — | — |

| Ascorbic acid | — | — | — | 45.83 ± 1.030 | 82.01 ± 1.42 |

2.3.2. Aβ1–42 inhibition assay and in vivo memory assessment by the Y-maze test

The most explored pathological marker of AD is Aβ1–42. Thus, the most active molecule, 3b, was studied to analyze if it possesses the potential to inhibit Aβ1–42 aggregation. The analysis performed at 0.5, 10, and 20 μM concentrations with donepezil revealed a notable reduction in Aβ1–42 aggregation. The analysis also revealed 3b to be much more potent in inhibiting Aβ1–42 aggregation at low micromolar concentrations (Fig. 3A). A hippocampus-dependent spatial memory assessment was performed using the Y-maze protocol. The spontaneous alternation score assessed by % alternation was used to assess the working memory. The score is used to investigate the cognitive and exploratory behaviours. Lead compound 3b was investigated at 4, 2, 1 and 0.5 mg kg−1 doses. Control and vehicle groups were used as positive controls, and % alternation was assessed up to 80% with no significant difference between these groups. The treated group showed a significant decrease in working memory. The marketed drug donepezil was found to restore the working memory to normal. The novel compound 3b showed no significant improvement in the % alternation score at the initial doses up to 2 mg kg−1 as compared to scopolamine. However, the animals treated with compound 3b at 4 mg kg−1 doses showed significantly improved working memory (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. (A) Aβ1–42 aggregation inhibition potential of compound 3b at various concentrations. Donepezil (DNP) was considered as the standard drug. (B) The effect of compound 3b (doses: 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 mg kg−1), scopolamine, and donepezil on spontaneous % alternation; the % alternation score is used to assess the hippocampus dependent spatial working memory. The alternation score of compound 3b at four different doses was analysed using donepezil as a positive control and scopolamine as a negative control. The control group contains distilled water, and the vehicle contains the media used to dissolve the drug. ap < 0.05 compared to the control; bp < 0.05 compared to the vehicle; cp < 0.05 compared to scopolamine; dp < 0.05 compared to donepezil; ep < 0.05 compared to compound 3b at a dose of 0.5 mg kg−1; fp < 0.05 compared to compound 3b at a dose of 1 mg kg−1; gp < 0.05 compared to compound 3b at a dose of 2 mg kg−1; hp < 0.05 compared to compound 3b at a dose of 4 mg kg−1 (one-way ANOVA followed by the Newman–Keuls test).

2.3.3. SHSY-5Y cell line-based neurotoxicity and histopathology studies

The cell line-based neurotoxicity of compound 3b was evaluated on the neuroblastoma cell line at three different concentrations. Compound 3b was found to be non-cytotoxic up to 20 μM concentration (Fig. 4B). However, a significant toxicity was observed at 40 μM. To evaluate the acute toxicity, the brain tissue was collected after the completion of the behavioural studies. The hippocampus of the various groups of animals was studied. Scopolamine treatment is reported to induce toxic lesions on the brain tissues. Treatment with scopolamine showed toxicity in the region of the hippocampus (Fig. 4A). However, such types of toxicity were not observed in all other treatment groups. Thus, the hit molecule 3b has a neuroprotective effect and protects the hippocampus cells from the toxic effect of scopolamine.

Fig. 4. (A) Histopathology of cells; (B) assessment of the toxicity on the SHSY-5Y cell line.

2.4. In silico studies

Molecular docking studies were performed with the most potent compound 3b and the standard drugs (donepezil and tacrine) within the binding pocket of AChE (PDB ID: 4EY7) and BuChE (PDB ID: 4BDS) to get a detailed insight into the probable non-covalent interactions prevailing in their protein–ligand complex. Re-docking of the co-crystallized ligand and assessment of the root mean square deviation (RMSD) are the essential criteria for validating the docking protocol. The protocol was established to be reliable, as an RMSD of less than 2 Å was observed and further utilized for molecular docking with the most potent compound and standards employed. The binding energies were evaluated for all four docked complexes. In the case of AChE (PDB: 4EY7), the most potent compound 3b and its standard drug, donepezil, displayed a binding energy of −13.62 and −11.99 kcal mol−1, respectively. The targeted compounds primarily engaged in H-bonding and π–π interactions. Compound 3b displayed H-bonding interactions with Asp74 with a bond distance of 2.23 Å. In addition to H-bonding interactions, the compound displayed π–π interactions with Trp341 and Trp86. The binding cavity of the protein (PDB: 4EY7) that accommodated 3b was lined with amino acids including Trp286, Ser125, Tyr124, Asp74, Gly121, Gly120, Glu202, Ser203, Tyr133, Gly448, His447, Trp86, Tyr337, Phe338, Tyr341, Val294, Phe295 and Arg296. The binding pocket of donepezil was also found to be lined with these amino acids. Moreover, the 4EY7–donepezil complex was also stabilized through H-bonding interaction with Phe295 and π–π interactions with Trp286 and Trp86. The interaction diagrams for both are presented in Fig. 5A. In the case of BuChE (PDB: 4BDS), the compound (3b) and standard drug (tacrine) were selected for docking studies. Compound 3b and tacrine displayed a binding energy of −9.9 and −8.1 kcal mol−1, respectively. The stabilization of 3b in the BuChE binding pocket was due to H-bonding and π–π interactions. Compound 3b fits into the BuChE cavity lined with amino acids including Gly78, Met437, Ser79, Gly117, Ser198, Ala199, His438, Trp430, Gly439, Tyr440, Trp82, Tyr332, Phe329, Gly115, Gly116, Phe398, Glu197, Trp231, Leu286, Ser287 and Val288. H-bonding interaction was observed between 3b and Trp82 with a bond distance of 2.6 Å. In addition to this, π–π stacking was observed with Trp82 and Phe329 amino acid residues. Compound 3b and tacrine bind with the BuChE protein within the same binding pocket lined with amino acids. In the case of the protein–tacrine complex, only Trp82 was involved in π–π interactions. The interaction diagrams for both are shown in Fig. 5B.

Fig. 5. (A) 2D and 3D interaction diagrams for docked complexes of 3b and donepezil with AChE (PDB ID: 4EY7) and (B) 3b and tacrine with BuChE (PDB ID: 4BDS) protein.

Next, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of 100 ns were performed for all four docked complexes to understand the stable interactions in a protein–ligand complex. The results indicated that both the protein backbone and the ligand in each complex remained stable, with minimal RMSD fluctuations throughout the simulation, confirming the stability of these docked complexes. An initial increase in RMSD was observed in all four cases within a time frame of 0–10 ns (Fig. 6A). After a simulation of 10 ns, all four complexes didn't display significant fluctuations in their RMSD values. Additionally, we analyzed RMSF values in all four complexes; protein residues involved in binding with the ligands exhibited minor fluctuations, generally less than 3 Å, signifying stable binding interactions. Some residues experienced larger fluctuations, primarily those situated in the outer loop of the protein, but these fluctuations didn't affect the binding pocket (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6. (A) RMSD of simulated complexes of AChE and BuChE; (B) RMSF of simulated complexes of AChE and BuChE.

The interaction fraction for all four complexes was also analyzed. In the case of the 4EY7–3b complex, compound 3b exhibited H-bond interaction with Tyr124 and Trp236 residues, with interaction fractions of 41 and 52%, respectively. Moreover, π–π interaction was observed with the Tyr341 amino acid residue with a 34% interaction fraction. Similarly, π–π interactions between donepezil and Trp286 and Trp86 and Tyr337 were observed in its simulated complex with an interaction fraction of 44, 49 and 38% (Fig. 7A). The presence of both compounds within the same binding pocket after a simulation of 100 ns revealed their stability (Fig. 7B and C). Similarly, the interaction fraction for the simulated complexes of BuChE was also assessed. In the case of the BuChE–3b complex, the main stabilization interactions were of π–π type and were observed between Trp82 and Phe329 amino acid residues with interaction fractions of 49 and 53%, respectively (Fig. 7A). In addition to this, many water-bridged hydrogen bonds were also present. The above findings of in silico studies revealed that the most potent compound, 3b, binds snugly within the binding pocket of the proteins (AChE and BuChE) and displays stable interactions.

Fig. 7. (A) Interaction fraction for simulated complexes; (B) 2D interaction diagram for 3b–4EY7 complex; (C) donepezil–4EY7 complex; (D) 3b–4EY7 complex; (E) tacrine–4EY7 complex after simulation of 100 ns.

In the end, we thought it worthwhile to understand the in silico pattern of our lead 3b drug metabolism. To achieve this, we utilized the application of GastroPlus® and explored the virtual metabolism for our best lead 3b. The analysis revealed the human liver microsomal (HLM) protein to be 41.5 μL min−1 mg−1, indicating predominant metabolism in the liver. The analysis of phase I metabolism reveals (Fig. 8A) that the metabolism of 3b resulted in two metabolites, M1 and M2. The major metabolite is M1 (90%), which is formed via the oxidation of the sulfur atom, eventually producing the sulfoxide derivative of 3b. The major enzymes identified in the generation of M1 involve CYP1A2 (22.9%), followed by CYP3A4 (13.7%) and CYP2C19 (0.5%). The secondary metabolite M2 is found to be generated via the involvement of CYP3A4 (4.1%) and CYP2C19 (0.2%). The metabolism involves the oxidation of the methyl group substituent to the hydroxyl analog. The phase II metabolism simulation analysis revealed (Fig. 8B) that UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) isoforms were involved in the metabolism. The metabolism consists of the transfer of glucuronic acid to the –NH2 (amine group) of 3b, thus making it polar and easier to excrete.

Fig. 8. Analysis and prediction of phase 1 (A) and phase II (B) metabolism using GastroPlus® software.

Next, we thought it worthwhile to predict the log D of our lead compound 3b. Log D measurement allows an efficient measurement of the lipophilicity of the synthetic compound. The analysis was done to ensure that the compound has enough potential to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and affect the target. The study (Fig. 9) revealed that log D stabilizes at approximately 3.4 at pH > 4, suggesting that 3b possesses plausibly moderate to high lipophilicity under physiological conditions and could easily cross the BBB.

Fig. 9. Analysis of log D for 3b using GastroPlus® software.

3. Experimental

Various building blocks, including amino pyrazole and substituted aryl thiols utilized in the present study, were procured from Sigma Aldrich in their analytically pure form. The received chemicals were utilized for the synthetic process without any further purification. Silica-coated (F254) aluminium plates from Merck Scientific were used in reaction monitoring. A melting point apparatus from JSGW was utilized to determine the melting point, and the determined melting points were uncorrected. An FT-IR spectrometer from Perkin Elmer was utilized to record IR spectra, and the stretching and bending vibration values are reported in cm−1. Bruker Ultra-Shield (300 MHz), JEOL ECZ-400S & ECZ-600S NMR spectrometers were used to record the developed synthetics' proton and carbon NMR spectra. A SCIEX TripleTOF-5600 mass spectrometer was used to record the compounds' mass data. The electro-organic synthetic platform from IKA (Electrasyn 2.0) was utilized to carry out all the synthetic reactions. A Y-maze test provided by Orchid Scientific India was used for behavioural testing.

3.1. Synthesis of sulfenylated aminopyrazoles (3a–3o)

A stirred solution of amino pyrazole (1) (0.28 mmol) and 2 (0.30 mmol) in CH3CN (3 mL) was treated with KI (50 mol%). The reaction was conducted using an Electrasyn 2.0, with glassy carbon as the cathode and anode. The formation of new products during the reaction was examined using TLC (MeOH : CHCl3 (5 : 95, v/v)). After 2 h, the complete disappearance of both reactants was observed. Then, the reaction mixture was added to ice-cold water and treated with sodium thiosulfate solution to neutralize the unreacted iodine. The resulting mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 50 mL) and dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate. The organic phase was concentrated and purified by chromatography on silica using a Buchi Pure-810 flash chromatograph with ethyl acetate/hexane as the eluent.

3-Methyl-1-phenyl-4-(p-tolylthio)-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3a)32

Yellow solid; yield 87%; M.pt: 98–101 °C; Rf: 0.84 (ethyl acetate: hexane (40 : 60; v/v)); IR (KBr, cm−1) νmax: 3306 (stretching, N–H), 1595 (stretching, C C, Ar), 704 (stretching, C–S); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 7.62–7.58 (m, 2H), 7.53–7.47 (m, 2H), 7.37–7.31 (m, 1H), 7.11–7.09 (m, 2H), 7.00–6.96 (m, 2H), 5.62 (s, 2H (–NH2)), 2.24 (s, 3H (–Me)), 2.06 (s, 3H (–Me)); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 152.08 (C N), 150.59 (C–NH2), 139.52 (Ar), 135.56 (Ar), 134.80 (Ar), 130.18 (Ar), 129.76 (Ar), 127.03 (Ar), 125.82 (Ar), 123.31 (Ar), 86.90 (C-S), 20.97 (–Me), 12.66 (–Me); MS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C17H17N3S: 295.1143; found: 296.1225 [M + H]+.

3-Methyl-4-((4-nitrophenyl)thio)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3b)

Yellow solid; yield: 78%; M.pt.: 98–103 °C; Rf: 0.75 (EA : hexane (40 : 60; v/v)); IR (KBr, cm−1) νmax: 3410 (N–H stretch), 1633 (C C stretch, Ar), 1504 (NO2 stretch, asymmetric), 1338 (NO2 stretch, symmetric), 707 (C–S stretch); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 8.13–8.09 (m, 2H), 7.58–7.55 (m, 2H), 7.50–7.45 (m, 2H), 7.34–7.30 (m, 1H), 7.25–7.21 (m, 2H), 5.82 (s, 2H (–NH2)), 2.02 (s, 3H (–Me)); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 152.01 (C N), 150.97 (C–NH2), 149.99 (C–NO2), 145.16 (Ar), 139.35 (Ar), 129.81 (Ar), 127.27 (Ar), 125.30 (Ar), 124.68 (Ar), 123.58 (Ar), 83.44 (C–S), 12.59 (–Me); MS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C16H14N4O2S: 326.0837; found: 327.0931 [M + H]+, 329.0907 [M + H + 2]+.

4-((4-Chlorophenyl)thio)-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3c)32

Brown solid; yield: 89%; M.pt.: 110–115 °C; Rf: 0.88 (EA : hexane (40 : 60; v/v)); IR (KBr, cm−1) νmax: 3287 (N–H stretch), 1593 (C C stretch, Ar), 690 (C–S stretch); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 7.62–7.58 (m, 2H), 7.53–7.48 (m, 2H), 7.38–7.33 (m, 3H), 7.10–7.05 (m, 2H), 5.74 (s, 2H (–NH2)), 2.06 (s, 3H (–Me)); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 152.07 (C N), 150.81 (C–NH2), 139.35 (Ar), 138.45 (Ar), 129.98 (Ar), 129.79 (Ar), 129.45 (Ar), 127.19 (Ar), 127.05 (Ar), 123.48 (Ar), 85.60 (C–S), 12.59 (Me); MS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C16H14ClN3S: 315.0597; found: 316.0670 [M + H]+.

4-((2,5-Dichlorophenyl)thio)-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3d)

Yellow solid; yield: 80%; M.pt.: 100–101 °C; Rf: 0.84 (EA : hexane (40 : 60; v/v)); IR (KBr, cm−1) νmax: 3289 (N–H stretch), 1599 (C C stretch, Ar), 697 (C–S stretch); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 7.58–7.55 (m, 2H), 7.49–7.44 (m, 3H), 7.35–7.30 (m, 1H), 7.19–7.16 (m, 1H), 6.56–6.57 (m, 1H), 5.86 (s, 2H (–NH2)), 2.00 (s, 3H (–Me)); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 152.14 (C N), 151.19 (C–NH2), 140.78 (Ar), 139.31 (Ar), 133.03 (Ar), 131.70 (Ar), 129.85 (Ar), 128.30 (Ar), 127.32 (Ar), 126.42 (Ar), 124.47 (Ar), 123.59 (Ar), 82.68 (C–S), 12.56 (Me); MS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C16H13Cl2N3S: 349.02; found: 350.20 [M + H]+, 352.00 [M + H + 2]+.

4-((2-Chlorophenyl)thio)-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3e)32

Yellow solid; yield: 73%; M.pt.: 100–103 °C; Rf: 0.84 (EA : hexane (40 : 60; v/v)); IR (KBr, cm−1) νmax: 3291 (N–H stretch), 1596 (C C stretch, Ar), 695 (C–S stretch); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 7.58–7.55 (m, 2H), 7.49–7.44 (m, 2H), 7.40 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.34–7.29 (m, 1H), 7.21 (td, J = 7.6 & 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (td, J = 7.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 5.71 (s, 2H (–NH2)), 1.99 (s, 3H (–Me)); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 152.25 (C N), 151.05 (C–NH2), 139.43 (Ar), 138.05 (Ar), 130.05 (Ar), 129.79 (Ar), 129.58 (Ar), 128.23 (Ar), 127.17 (Ar), 126.52 (Ar), 125.54 (Ar), 123.52 (Ar), 83.70 (C–S), 12.60 (Me); MS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C16H14ClN3S: 315.0597; found: 316.0694 [M + H]+, 318.0662 [M + H + 2]+.

4-((4-Bromophenyl)thio)-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3f)

Yellow solid; yield: 85%; M.pt.: 98–105 °C; Rf: 0.84 (EA : hexane (40 : 60; v/v)); IR (KBr, cm−1) νmax: 3306 (N–H stretch), 1595 (C C stretch, Ar), 703 (C–S stretch); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 7.57–7.54 (m, 2H), 7.48–7.41 (m, 4H), 7.32–7.28 (m, 1H), 6.99–6.95 (m, 2H), 5.70 (s, 2H (–NH2)), 2.02 (s, 3H (–Me)); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 152.08 (C N), 150.78 (C–NH2), 139.47 (Ar), 139.11 (Ar), 132.30 (Ar), 129.77 (Ar), 127.33 (Ar), 127.10 (Ar), 123.40 (Ar), 118.09 (Ar), 85.34 (C–S), 12.64 (Me); MS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C16H14BrN3S: 359.0092; found: 360.0188 [M + H]+, 362.0168 [M + H + 2]+.

4-((3-Chlorophenyl)thio)-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3g)

Brown solid; yield: 80%; M.pt.: 75–78 °C; Rf: 0.84 (EA : hexane (40 : 60; v/v)); IR (KBr, cm−1) νmax: 3314 (N–H stretch), 1606 (C C stretch, Ar), 696 (C–S stretch); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 7.63–7.59 (m, 2H), 7.54–7.48 (m, 2H), 7.39–7.28 (m, 2H), 7.20–7.17 (m, 1H), 7.06–7.03 (m, 2H), 5.82 (s, 2H (–NH2)), 2.07 (s, 3H (–Me)); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 152.17 (C N), 150.86 (C–NH2), 142.14 (Ar), 139.33 (Ar), 134.32 (Ar), 131.26 (Ar), 129.84 (Ar), 127.24 (Ar), 125.37 (Ar), 124.40 (Ar), 123.97 (Ar), 123.47 (Ar), 84.89 (C–S), 12.58 (Me); MS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C16H14ClN3S: 315.0597; found: 316.0688 [M + H]+, 318.0655 [M + H + 2]+.

4-((4-Fluorophenyl)thio)-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3h)32

Yellow solid; yield: 81%; M.pt.: 100–104 °C; Rf: 0.8 (EA : hexane (40 : 60; v/v)); IR (KBr, cm−1) νmax: 3443 (N–H stretch), 1596 (C C stretch, Ar), 1222 (C–F stretch), 703 (C–S stretch); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 7.56 (s, 2H), 7.53–7.43 (m, 2H), 7.30 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), 5.66 (s, 2H (–NH2)), 2.03 (s, 3H (–Me)); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 162.03 (C–F), 159.63 (C–F), 152.03 (C N), 150.70 (C–NH2), 139.49 (Ar), 134.72 (Ar), 129.76 (Ar), 127.63 (Ar), 127.55 (Ar), 127.07 (Ar), 123.37 (Ar), 116.67 (Ar), 116.45 (Ar), 86.54 (C–S), 12.66 (Me); MS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C16H14FN3S: 299.0892; found: 300.0969 [M + H]+.

3-Methyl-1-phenyl-4-(phenylthio)-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3i)

Yellow solid; yield: 68%; M.pt.: 97–100 °C; Rf: 0.84 (EA : hexane (40 : 60; v/v)); IR (KBr, cm−1) νmax: 3412 (N–H stretch), 1596 (C C stretch, Ar), 705 (C–S stretch); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 7.58–7.56 (m, 2H), 7.48–7.44 (m, 2H), 7.32–7.26 (m, 1H), 7.26–7.22 (m, 2H), 7.09–7.01 (m, 3H), 5.63 (s, 2H (–NH2)), 2.02 (s, 3H (–Me)); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 152.16 (C N), 150.72 (C–NH2), 139.56 (Ar), 139.25 (Ar), 129.76 (Ar), 129.56 (Ar), 127.02 (Ar), 125.41 (Ar), 125.36 (Ar), 123.33 (Ar), 86.05 (C–S), 12.69 (Me); MS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C16H15N3S: 281.0987; found: 282.1078 [M + H]+.

4-((3-Fluorophenyl)thio)-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3j)

Yellow solid; yield: 80%; M.pt.: 95–99 °C; Rf: 0.84 (EA : hexane (40 : 60; v/v)); IR (KBr, cm−1) νmax: 3417 (N–H stretch), 1596 (C C stretch, Ar), 1208 (C–F stretch), 690 (C–S stretch); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 7.58–7.54 (m, 2H), 7.48–7.43 (m, 2H), 7.33–7.26 (m, 2H), 6.93–6.86 (m, 2H), 6.79–6.75 (m, 1H), 5.72 (s, 2H (–NH2)), 2.02 (s, 3H (–Me)); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 164.38 (C–F), 161.94 (C–F), 152.10 (C N), 150.87 (C–NH2), 142.54 (Ar), 142.46 (Ar), 139.44 (Ar), 131.32 (Ar), 129.79 (Ar), 127.16 (Ar), 123.48 (Ar), 121.27 (Ar), 112.33 (Ar), 112.11 (Ar), 111.87 (Ar), 111.63 (Ar), 85.04 (C–S), 12.61 (Me); MS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C16H14FN3S: 299.0892; found: 300.0992 [M + H]+.

3-Methyl-4-(naphthalen-2-ylthio)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3k)

Brown semi-solid; yield: 89%; M.pt.: 40–44 °C; Rf: 0.83 (EA : hexane (40 : 60; v/v)); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 7.85 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.56–7.35 (m, 6H), 7.27 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 5.71 (s, 2H (–NH2)), 2.10 (s, 3H (–Me)); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 152.40 (C N), 150.82 (C–NH2), 139.17 (Ar), 136.71 (Ar), 133.90 (Ar), 131.52 (Ar), 129.91 (Ar), 129.14 (Ar), 128.20 (Ar), 127.40 (Ar), 127.27 (Ar), 125.84 (Ar), 124.55 (Ar), 123.58 (Ar), 122.77 (Ar), 86.33 (C–S), 12.60 (Me); MS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C20H17N3S: 331.1143; found: 332.1219 [M + H]+.

3-Methyl-1-phenyl-4-(o-tolylthio)-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3l)32

Yellow solid; yield: 75%; M.pt.: 80–83 °C; Rf: 0.84 (EA : hexane (40 : 60; v/v)); IR (KBr, cm−1) νmax: 3300 (N–H stretch), 1596 (C C stretch, Ar), 695 (C–S stretch); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δH: 7.61–7.59 (m, 2H), 7.50–7.47 (m, 2H), 7.35 (dd, J = 7.3, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.13–7.12 (m, 1H), 7.04 (dd, J = 7.3, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 6.80–6.78 (m, 1H), 4.17 (s, 2H (-NH2)), 2.43 (s, 3H (–Me)), 2.21 (s, 3H (–Me)); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δC: 153.44 (C N), 148.56 (C–NH2), 138.79 (Ar), 137.04 (Ar), 134.40 (Ar), 130.24 (Ar), 129.72 (Ar), 127.51 (Ar), 126.57 (Ar), 124.71 (Ar), 123.78 (Ar), 123.46 (Ar), 87.12 (C–S), 19.75 (Me), 12.37 (Me); MS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C17H17N3S: 295.1143; found: 296.1211 [M + H]+.

4-((3-Methylphenyl)thio)-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3m)32

White solid; yield: 83%; M.pt.: 110–115 °C; IR (KBr, cm−1) νmax: 3301 (N–H stretch), 1594 (C C stretch, Ar), 694 (C–S stretch); Rf: 0.88 (EA : hexane (40 : 60; v/v)); IR (KBr, cm−1) νmax: 3330 (N–H stretch), 1596 (C C) (aromatic stretch), 689 (C–S stretch); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δH: 7.61–7.58 (m, 2H), 7.50–7.47 (m, 2H), 7.36–7.33 (m, 1H), 7.13–7.10 (m, 1H), 6.93–6.87 (m, 3H), 4.19 (s, 2H (–NH2)), 2.28 (s, 3H (–Me)), 2.24 (s, 3H (–Me)); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δC: 153.30 (C N), 150.98 (C–NH2), 148.52 (Ar), 138.90 (Ar), 138.07 (Ar), 129.70 (Ar), 126.05 (Ar), 123.43 (Ar), 122.18 (Ar), 88.07 (C–S), 21.52 (Me), 12.41 (Me); MS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C17H17N3S: 295.1143; found: 296.1219 [M + H]+.

4-((2-Bromophenyl)thio)-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3n)

White solid; yield: 73%; M.pt.: 105–109 °C; Rf: 0.84 (EA : hexane (40 : 60; v/v)); IR (KBr, cm−1) νmax: 3304 (N–H stretch), 1590 (C C stretch, Ar), 700 (C–S stretch); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δH: 7.59 (dd, J = 8.7, 1.3 Hz, 2H), 7.51–7.48 (m, 3H), 7.37–7.34 (m, 1H), 7.16 (td, J = 7.5, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (td, J = 7.5, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (dd, J = 8.7, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 4.22 (s, 2H (–NH2)), 2.22 (s, 3H (–Me)); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δC: 153.39 (C N), 148.70 (C–NH2), 139.13 (Ar), 138.65 (Ar), 132.99 (Ar), 129.77 (Ar), 127.85 (Ar), 127.67 (Ar), 126.15 (Ar), 125.42 (Ar), 123.51 (Ar), 119.97 (Ar), 86.95 (C–S), 12.35 (Me); MS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C16H14BrN3S: 359.0092; found: 360.0130 [M + H]+, 362.0108 [M + H + 2]+.

4-((2,4-Dimethylphenyl)thio)-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (3o)

Yellow solid; yield: 79%; M.pt.: 90–94 °C; Rf: 0.88 (EA : hexane (40 : 60; v/v)); IR (KBr, cm−1) νmax: 3300 (N–H stretch), 1592 (C C stretch, Ar), 695 (C–S stretch); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δH: 7.61–7.59 (m, 2H), 7.50–7.46 (m, 2H), 7.36–7.33 (m, 1H), 6.96 (s, 1H), 6.87 (dd, J = 8.0, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.16 (s, 2H (–NH2)), 2.40 (s, 3H (–Me)), 2.25 (s, 3H (–Me)), 2.21 (s, 3H (–Me)); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δC: 153.40 (C N), 148.47 (C–NH2), 138.84 (Ar), 134.50 (Ar), 134.36 (Ar), 133.45 (Ar), 131.23 (Ar), 129.70 (Ar), 127.45 (Ar), 127.29 (Ar), 124.14 (Ar), 123.42 (Ar), 87.60 (C–S), 20.78 (Me), 19.71 (Me), 12.37 (Me); MS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C18H19N3S: 309.4310; found: 310.1357 [M + H]+.

3.2. Biology

In vitro AChE and BuChE inhibition assay

The inhibitory potential of the synthesized thiolated amino pyrazoles was assessed against AChE and BuChE by following a reported procedure with minor modifications. Both enzymes utilized in the present study were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (AChE (CAS No. 9000-81-1) and BuChE (CAS No. 9001-08-5)). Other chemicals, including butyrylthiocholine iodide (BTCI), acetylthiocholine iodide (ATCI), and 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB, Ellman's reagent), were purchased from Himedia. Donepezil and tacrine were employed as standard drugs, and Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8) was used as the media for performing the assay. Six concentrations of test compounds starting from 0.1 μM to 200 μM were selected for the evaluation and the determination of IC50 values. All the experiments were performed in 96-well plates. Initially, 50 μL of AChE (1.00 U mL−1) or BuChE (0.6 U mL−1) was mixed with 20 μL of test or standard compounds and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Then, 100 μL of 1.5 mM DTNB was added. The substrate (ATCI, 15 mM, 10 μL or BTCI, 30 mM, 10 μL) was introduced, and absorbance was recorded immediately at 415 nm for 20 min at 1 min intervals using a Synergy HTX multi-mode reader (BioTek, USA). IC50 values were derived from the absorbance data of the test and standard compounds. Each assay was performed in triplicate across three independent experiments.33,34

Antioxidant activity (DPPH assay)

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) is a stable free radical characterized by its purple color. It interacts with antioxidants, resulting in the formation of yellow diphenylpicrylhydrazine. This assay evaluates the free radical scavenging ability of a compound by measuring the reduction of DPPH through antioxidant activity using a reported procedure.35–37 In summary, 10 μL of synthesized compounds at concentrations of 100 and 50 μM in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) were mixed with 20 μL of 10 mM DPPH solution (stock in methanol) in a 96-well plate. The total volume was adjusted to 200 μL with methanol. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 25 min in a shaking water bath with moderate agitation. The absorbance of the reaction mixture was recorded at 520 nm. The reduction percentage (RP) of DPPH was calculated using the formula RP = 100 [(A0 − Ac)/A0], where A0 represents the absorbance of the control (untreated DPPH) and Ac represents the absorbance of the test (treated DPPH). Ascorbic acid served as the standard for this assay.34

Aβ1–42 inhibition assay

The thioflavin T (ThT) assay was performed to evaluate the inhibitory potential of compound 3b.38,39 A 200 μM stock solution of Aβ1–42 was prepared by dissolving it in 10 mM phosphate buffer (PBS) at pH 7.5. The developed synthetics were also dissolved in DMSO and further diluted with PBS. The ThT assay used various ratios of Aβ1–42 to the inhibitor (1 : 0.5, 1 : 1, 1 : 2). The mixtures were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 48 h. At the end of the incubation, fluorescence intensities were measured by adding 178 μL of 20 μM ThT, with excitation and emission wavelengths set at 450 and 483 nm, respectively.33

SH-SY5Y cell line-based cytotoxicity study

The MTT assay on the SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line was performed to assess the neuroprotective effect of compound 3b using slight modification in a reported procedure. In brief, the cells (at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well) were seeded into 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified environment. Varying concentrations (10, 20, and 40 μM) of compound 3b were added to the 96-well plates, which were further incubated for another 72 h. Then, an MTT reagent (20 μL) was introduced to each well, and the incubation was carried out further for 2 h. The resulting purple formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 μL of DMSO per well. Absorbance was then measured at 570 nm to determine cell viability, expressed as a percentage of the control. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.33

Scopolamine induced amnesia model

Animals

The study utilized adult male Swiss albino mice weighing 20–25 g. The mice were housed in polyacrylic cages (22.5 × 37.5 cm) at 24–27 °C, with a 12 h light and dark cycle. Food was withheld for 1 h before the behavioural tests. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of “Indian Institute of Technology (BHU), Varanasi” and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Institute, Protocol No. Dean/13-14/CAEC/344.

Administration of scopolamine

The solution of scopolamine hydrobromide was prepared by dissolving 3 mg kg−1 in distilled water and administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) on the seventh day, 1 h after the administration of the test compound or donepezil. Behavioural assessments were recorded after 5 min of post-scopolamine injection.

Experimental protocol and drug administration

Mice were allocated into eight groups, each comprising six animals. Donepezil and test compound 3b were freshly dissolved in distilled water before administration. The experimental groups were as follows: (i) vehicle (1 mL), (ii) scopolamine (3 mg kg−1), (iii) scopolamine plus donepezil (1 mg kg−1), (iv) scopolamine plus compound 3b (0.5 mg kg−1), (v) scopolamine plus compound 3b (1 mg kg−1), (vi) scopolamine plus compound 3b (2 mg kg−1), (vii) scopolamine plus compound 3b (4 mg kg−1), and (viii) control. Doses were determined based on their LD50 values. All treatments were administered via intraperitoneal injection. Donepezil and the test compounds were administered once daily for seven days. On the seventh day, scopolamine was administered to all groups except the vehicle and control groups to induce amnesia.

3.3. In silico docking and dynamics simulation

Molecular docking analyses were carried out to determine the binding energy and explore the non-covalent interactions within the protein–ligand complex, aiming to identify potential ligand binding sites.40 The binding mode of compound 3b with AChE and BuChE was predicted using Maestro Glide. The protein structures of AChE (PDB ID: 4EY7) and BuChE (PDB ID: 4BDS) originated from the RCSB Protein Data Bank and subsequently prepared and minimized using Prime. Blind docking was performed to identify binding sites in the AChE and BuChE protein structures, utilizing a grid box of −14.11 × −43.83 × 27.67 Å and 132.99 × 116.01 × 41.21 Å, respectively, along the x, y, and z axes, which covered the entire protein. Ligand preparation was completed using the LigPrep module in Maestro. Extra-precise docking was performed with a scaling factor of 0.80 and a partial charge cut-off of 0.15. The docking results were further analyzed using PyMOL and Chimera for visualization and interpretation.35–37

Molecular dynamics simulations were conducted using Desmond software over a 100 ns period to assess the stability of protein–ligand interactions.41 The SPC solvation model was applied to solvate the complexes within an orthorhombic box of dimensions 10 Å, and Na+ and Cl− ions were added to neutralize the system electrically.42 The protein–ligand system was prepared for dynamics simulation using the System Builder tool. Initial minimization and relaxation were performed using OPLS 2005 force field parameters within the Desmond package.43 The molecular dynamics simulation was conducted under NPT ensemble conditions at 300 K and 1.01325 bar, with a cut-off radius of 9 Å. The stability of the protein–ligand complexes was determined by analyzing the RMSD of the ligand and the RMSF of the proteins.37

4. Conclusion

Aminopyrazole-based thioethers (3a–3o) were synthesized using electro-organic synthesis in good to excellent yields (68–89%). All the synthesized molecules were characterized using spectroscopic techniques, and the single crystal for one of the compounds (3i) was developed. The developed synthetics (3a–3o) were further explored for acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activity. Among them, compound 3b (4-NO2) was observed to be the most active with IC50 values of 1.634 ± 0.066 and 0.0285 ± 0.019 μM against AChE and BuChE, respectively, in comparison with standard drugs donepezil (IC50 = 2.019 and 17.38 ± 0.028 μM) and tacrine (29.84 ± 0.04 and 28.49 ± 0.02 μM). The results of the anti-oxidant assay revealed that compound 3d possesses strong antioxidant properties that may contribute to its potential efficacy in counteracting the oxidative stress associated with Alzheimer's disease. The most active compound (3b) was also studied for its Aβ1–42 aggregation inhibition potential, where it displayed a similar trend at 20 μM to that observed for donepezil. Hippocampus dependent spatial memory assessment was performed for 3b by the Y-maze protocol. Animals treated with a 4 mg kg−1 dosage of 3b exhibited a notable enhancement in the working memory. Neurotoxicity and histopathology evaluations indicated that compound 3b was non-cytotoxic at concentrations up to 20 μM and demonstrated a neuroprotective effect, safeguarding hippocampal cells from scopolamine-induced toxicity. Additionally, molecular docking studies were carried out with 3b and standard drugs (donepezil and tacrine) in the binding pockets of AchE and BuChE, respectively, to determine the binding interactions. Compound 3b exhibited a good binding affinity with a binding energy of −13.62 & −9.9 kcal mol−1 against AchE and BuChE, respectively, as compared to the standard drugs. A molecular dynamics simulation of 100 ns revealed that compound 3b binds snugly within the binding pocket of both proteins (AChE and BuChE) and exhibits stable interactions. The metabolism prediction of 3b achieved using GastroPlus® software revealed that the compound undergoes phase I metabolism via oxidation of the sulfur atom. At the same time, phase II metabolism involves conjugation with glucuronic acid catalysed by UGT. Additionally, compound 3b possessed optimal log D, enabling it to cross the BBB.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Author contributions

Payal Rani (PR) – methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, visualisation, writing – original draft; Sandhya Chahal (SC) – conceptualization, software; Anju Ranolia (AR) – conceptualization, writing – review and editing; Kiran (K) – conceptualization; Devendra Kumar (DK) – visualization; Ramesh Kataria (RK) – resources and software; Parvin Kumar (PK) – supervision, conceptualization; Devender Singh (DS) – visualization; Anil Duhan (AD) – visualization; Vibhu Jha (VJ) – resources, review and editing; Muhammad Wahajuddin (MW) – resources, review and editing; Gaurav Joshi (GJ) – conceptualization, resources, visualization, writing – review and editing; Jayant Sindhu (JS) – supervision, software, conceptualization, project administration, writing – original draft.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

PR and Kiran thank UGC for SRF, AR thanks UGC for JRF, JS thanks CCS HAU for providing a basic research facility, VJ would like to gratefully acknowledge Prof. Rob Falconer, Director of the Institute of Cancer Therapeutics, and Dr. Gemma Quinn, Head of School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, University of Bradford, UK, for providing funding to establish a computational modeling facility. GJ thanks and acknowledges the Department of Biotechnology, New Delhi Grant No. BT/PR47642/CMD/150/24/2023 for financial support.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. CCDC 2305521. For ESI and crystallographic data in CIF or other electronic format see DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d5md00069f

References

- Masters C. L. Bateman R. Blennow K. Rowe C. C. Sperling R. A. Cummings J. L. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2015;1:15056. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir J. L. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 1997;56:687–696. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00431-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enwefa S. C. Enwefa R. L. J. Neurol. Surg. Rep. 2020;3:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ho J. Y. Franco Y. SSM - Popul. Health. 2022;17:101052. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q. Wang Q. Fu J. Xu X. Guo D. Pan Y. Zhang T. Wang H. ACS Nano. 2024;18:33032–33041. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.4c05693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y. Duan J. Dang X. Yuan Y. Wang Y. He X. Bai R. Ye X. Y. Xie T. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2023:38. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2023.2195991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. Tan Y. Cheng X. Zhang Z. Huang J. Hui S. Zhu L. Liu Y. Zhao D. Liu Z. Peng W. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.990307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H. Xiang Y. Qu X. Liu H. Liu C. Li G. Han L. Qin X. Front. Pharmacol. 2019;10:395. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X. Huang J. Li H. Zhao D. Liu Z. Zhu L. Zhang Z. Peng W. Phytomedicine. 2024;126:154887. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2023.154887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q.-Q. Chen Y.-M. Liu H.-R. Yan J.-Y. Cui P.-W. Zhang Q.-F. Gao X.-H. Feng X. Liu Y.-Z. Drug Dev. Res. 2020;81:1037–1047. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Crespo M. Domínguez-Álvaro M. Alonso-Nanclares L. DeFelipe J. Blazquez-Llorca L. Brain. 2021;144:553–573. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X.-H. Tang J.-J. Liu H.-R. Liu L.-B. Liu Y.-Z. Drug Dev. Res. 2019;80:438–445. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang L. Gao X.-H. Liu H.-R. Men X. Wu H.-N. Cui P.-W. Oldfield E. Yan J.-Y. Mol. Diversity. 2018;22:893–906. doi: 10.1007/s11030-018-9839-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. Yan Z. Yang W. Liu R. Fan G. Gu Z. Tang Z. Sens. Actuators, B. 2025;424:136895. [Google Scholar]

- Gok M. Cicek C. Bodur E. J. Neurochem. 2024;168:381–385. doi: 10.1111/jnc.15833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing S. Li Q. Xiong B. Chen Y. Feng F. Liu W. Sun H. Med. Res. Rev. 2021;41:858–901. doi: 10.1002/med.21745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obaid R. J. Naeem N. Mughal E. U. Al-Rooqi M. M. Sadiq A. Jassas R. S. Moussa Z. Ahmed S. A. RSC Adv. 2022;12:19764–19855. doi: 10.1039/d2ra03081k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asghar A. Yousuf M. Fareed G. Nazir R. Hassan A. Maalik A. Noor T. Iqbal N. Rasheed L. RSC Adv. 2020;10:19346–19352. doi: 10.1039/d0ra02339f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y. Liu D. Zhang H. Wang Y. Wang D. Cai H. Wen H. Yuan G. An H. Wang Y. Shi T. Wang Z. Bioorg. Chem. 2021;115:105255. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecchio I. Sorrentino L. Paoletti A. Marra R. Arbitrio M. J. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Dis. 2021;13:11795735211029112. doi: 10.1177/11795735211029113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. Zhang G. Zhang Z.-W. Jiang X. Zhang Z. Li H. Qin H.-L. Tang W. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021;36:1860–1873. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2021.1959571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhute S. Sarmah D. Datta A. Rane P. Shard A. Goswami A. Borah A. Kalia K. Dave K. R. Bhattacharya P. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2020;3:472–488. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.9b00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajendra K. Pratap G. K. Poornima D. V. Shantaram M. Ranjita G. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2024;11:100154. [Google Scholar]

- Medda N. Patra R. Ghosh T. K. Maiti S. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020;198:8–15. doi: 10.1007/s12011-020-02044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj K. Kaur P. Gupta G. D. Singh S. Neurosci. Lett. 2021;753:135873. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2021.135873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman M. U. Sehar N. Dar N. J. Khan A. Arafah A. Rashid S. Rashid S. M. Ganaie M. A. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023;144:104961. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greig N. H. Lahiri D. K. Kumar S. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2002;14:77–91. doi: 10.1017/s1041610203008676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard C. G. Eur. Neurol. 2002;47:64–70. doi: 10.1159/000047952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidan G. S. Parlar S. Tarikogullari A. H. Alptuzun V. Alpan A. S. Arch. Pharm. 2022;355:2200152. doi: 10.1002/ardp.202200152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung J. Rudolph M. J. Burshteyn F. Cassidy M. S. Gary E. N. Love J. Franklin M. C. Height J. J. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:10282–10286. doi: 10.1021/jm300871x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachon F. Carletti E. Ronco C. Trovaslet M. Nicolet Y. Jean L. Renard P.-Y. Biochem. J. 2013;453:393–399. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. Zou Q. Wang Q. Jin D. Jiang S. Qian P. J. Org. Chem. 2024;89:5434–5441. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.3c02888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S. M. Behera A. Jain N. K. Tripathi A. Rishipathak D. Singh S. Ahemad N. Erol M. Kumar D. RSC Adv. 2023;13:26344–26356. doi: 10.1039/d3ra03224h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma O. P. Bhat T. K. Food Chem. 2009;113:1202–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Takatsuka M. Goto S. Kobayashi K. Otsuka Y. Shimada Y. Food Biosci. 2022;48:101714. [Google Scholar]

- Farzan M. Abedi B. Bhia I. Madanipour A. Farzan M. Bhia M. Aghaei A. Kheirollahi I. Motallebi M. Amini-Khoei H. Ertas Y. N. Chem A. C. S. Neuroscience. 2024;15:2966–2981. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.4c00349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacques M. T. de Souza V. Barbosa F. A. R. Canto R. Faria Santos. Lopes S. C. Prediger R. D. Braga A. L. Aschner M. Farina M. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023;14:2857–2867. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.3c00138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekhar K. Narayanaswamy N. Murugan N. A. Kuang G. Ågren H. Govindaraju T. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:23668. doi: 10.1038/srep23668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekhar K. Narayanaswamy N. Murugan N. A. Viccaro K. Lee H.-G. Shah K. Govindaraju T. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017;98:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2017.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maity P. Katiyar M. K. Ranolia A. Joshi G. Sindhu J. Kumar R. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A. 2024;457:115878. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhu J. Mayank A. K. K. Bhasin N. Kaur N. S. Bhasin K. K. New J. Chem. 2019;43:2065–2076. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash H. Chahal S. Tyagi P. Sharma D. Mangyan M. R. Srivastava N. Sindhu J. Singh K. J. Mol. Struct. 2025;1319:139437. [Google Scholar]

- Chahal S. Punia J. Rani P. Singh R. Mayank P. Kumar R. Kataria G. J. Sindhu J. RSC Med. Chem. 2023;14:757–781. doi: 10.1039/d2md00431c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.