Abstract

Introduction

Transarterial radioembolisation (RE) using yttrium-90 (Y-90) microspheres is a widely used locoregional therapy for a broad spectrum of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) given its favourable safety profile. We evaluated the real-world outcomes of unresectable HCC treated with resin Y-90 RE and the relationship between tumour absorbed dose and subsequent curative therapy with survival.

Methods

Included were consecutive patients treated with Y-90 resin microspheres RE for unresectable HCC between January 2008 and May 2019 at the National Cancer Centre Singapore/Singapore General Hospital. The outcomes were stratified by tumour burden, distribution, presence of portal vein invasion (PVI) and liver function to improve prognostication.

Results

The median overall survival (OS) evaluated on 413 included patients was 20.9 months (95% CI: 18.2–24.0). More than half of the patients (214/413, 51.8%) had HCC beyond up-to-seven criteria, and 37.3% had portal vein invasion (154/413, 37.3%). Majority (71.7%) had dosimetry calculated based on the partition model. Patients who received ≥150 Gy to tumour had significantly better outcomes (OS 32.2 months, 95% CI: 18.3–46.4) than those who did not (OS 17.5 months, 95% CI: 13.7–22.7, p < 0.001). Seventy patients (17%) received curative therapies after tumour was downstaged by Y-90 RE and had better OS of 79.7 months (95% CI: 40.4 – NE) compared to those who did not receive curative therapies (OS 17.1 months; 95% CI: 13.5–20.4, p < 0.001). RE-induced liver injury was observed in 5.08% of the patients while 3.2% of the patients had possible radiation pneumonitis but none developed Grade 3–4 toxicity. For HCC without PVI, OS differed significantly with performance status, albumin-bilirubin grade, tumour distribution, and radiation dose; for HCC with PVI, Child-Pugh class and AFP were significant predictors of survival.

Conclusions

Treatment outcomes for unresectable HCC using Y-90 RE were favourable. Incorporating tumour burden and distribution improved prognostication. Patients who received tumour absorbed dose above 150 Gy had better OS. Patients who subsequently received curative therapies after being downstaged by Y-90 RE had remarkable clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Liver cancer, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Radioembolisation, Selective internal radiation therapy, Downstage

Introduction

Primary liver cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality and the sixth most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide [1]. The number of new cases of liver cancer is expected to increase by 55% by 2040, and 1.3 million people globally could die from liver cancer in 2040 [2]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the major cause of primary liver cancer, and Asia carries the highest burden of this disease. The overall prognosis of HCC is poor, with less than 20% of the patients surviving 5 years after diagnosis [3, 4]. Data from the National Cancer Centre Singapore showed that at the time of diagnosis, 46% of the HCC patients had locally advanced disease and 33% had metastatic disease [5].

The clinical management of HCC is determined by a few major factors such as tumour burden, underlying liver function, and the patient's functional status. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system is widely used in clinical studies and is useful for prognostication [6–9]. Patients staged as intermediate HCC (BCLC B), however, encompass a heterogeneous population who receive a range of treatment modalities with treatment aims ranging from curative intent to best supportive care, resulting in significant disparities in clinical outcomes [6, 10]. Advanced HCC (BCLC C) is similarly heterogenous and includes patients with vascular invasion and/or extra-hepatic disease. Despite considerable clinical variations in BCLC B-C patients, limited data are available regarding the influence of tumour burden and distribution on the clinical outcomes associated with various treatment modalities. It remains challenging to individualise treatment approaches for patients with intermediate and locally advanced HCC.

Transarterial radioembolisation (RE) with yttrium-90 (Y-90) microspheres, also known as selective internal radiation therapy, is an increasingly used therapy for early to locally advanced HCC including patients with vascular invasion [11–16]. Due to the hypervascular nature of HCC, intra-arterially injected microspheres are preferentially directed to the tumour where the Y-90 particles deliver short-ranged but high-energy beta radiation with a short half-life, which are attributes ideal for brachytherapy. As the microspheres used in RE are much smaller than particles used in transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE), they lodge in the arterioles with minimal arterial embolisation. As such, tumoricidal effects are primarily mediated by radiation injury rather than ischaemic injury [17, 18]. Currently, two major types of Y-90 microspheres are used clinically, namely resin and glass microspheres. While they are different in size, activity per microsphere and the number of injected microspheres, no significant survival difference was apparent in a large prospective study [19]. In 2021, glass Y-90 RE was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for unresectable solitary HCC up to 8 cm with preserved liver function on the basis of the LEGACY study [11]. Surgical resection and transplantation of HCC after downstaging with Y-90 RE are effective and safe, but it remains unclear how these impact clinical outcomes [20–23]. A number of expert consensus statements have been published to provide guidance on using Y-90 resin microspheres for HCC patients, including in Asia but the optimal dose-response relationship is yet to be determined [24]. Post hoc analysis from the SARAH randomised controlled trial suggested that patients who received a tumour absorbed dose of >100 Gray (Gy) of resin microspheres has better clinical outcomes, and the probability for disease control reached 90% with >150 Gy delivery [25]. Similarly, a randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 2 trial (DOSISPHERE-01) found personalised dosimetry with a target of ≥205 Gy glass microspheres to tumour achieved significantly improved outcomes (median overall survival [OS] of 24.8 mo) compared to a standard dosimetry group with 120 ± 20 Gy to the perfused liver territory (OS of 10.7 mo, p = 0.02) [26, 27].

Previous reports on HCC treated by Y-90 RE did not provide granular data on clinical outcomes with various tumour burdens and radiation doses. Here, we aim to evaluate the impact of tumour burden, tumour distribution, tumour absorbed dose and subsequent curative therapy on clinical outcomes in patients with HCC treated with Y-90 resin microsphere RE.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This is a single-centre retrospective cohort study that enrolled consecutive patients treated with Y-90 RE from January 1, 2008, to May 22, 2019, at the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS) and Singapore General Hospital (SGH). The data were extracted from Sunrise Clinical Manager (Allscripts Health Solutions INC, Chicago, IL, USA) and recorded into a prospectively maintained electronic database. All patients were at least 18 years old and HCC was diagnosed according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) criteria [28]. The following patients were excluded from the study: patients (1) with less than one follow-up visit after Y-90 RE treatment, (2) had Y-90 RE for non-HCC tumours, (3) had metastatic disease at the time of Y-90 RE, (4) had concurrent second primary cancer, and/or (5) had significant missing data such as post-treatment scan for disease evaluation. Baseline laboratory values, relevant clinical histories, Child-Pugh Score, albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade, tumour burden, and pre- and post-treatment imaging were collected. Radiological findings were reviewed and reported by experienced radiologists in our institution.

Y-90 RE Procedure

The first stage of the procedure included a planning hepatic angiography and intra-arterial injection of technetium-99m-labelled macroaggregated albumin (Tc-99m MAA) into targeted vascular territories. Both planar and single-photon emission computed tomography-CT (SPECT-CT) were then performed for eligibility and dosimetry planning as previously described [29]. Eligible patients subsequently received Y-90 RE using resin microspheres (SIR-Spheres, Sirtex Medical, USA) within 4 weeks of the Tc-99m MAA study. For patients with bilobar disease, two injections were given separately in the right and left hepatic artery. This could be in a single setting or a staged procedure within 6 weeks interval based on physician’s preference and patient’s characteristics [30]. Significant gastrointestinal uptake was avoided by prophylactic coiling of involved arteries. Y-90 RE was contraindicated in patients with hepato-pulmonary shunts greater than 20% or resulting in more than 20 Gy of planned radiation dose to the lungs.

Dosimetry Analysis

The partition model was used for prediction of tumour absorbed dose, normal liver absorbed dose and lung absorbed dose based on Tc-99m MAA SPECT/CT in 71.7% (296/413) of the patients, while the remaining cases used the manufacturer-recommended body surface area (BSA) model. Shortly after hepatic angiography with Tc-99m MAA injection, the lung shunt fraction was evaluated with planar and SPECT-CT imaging. For the partition model, regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn for the lungs, liver, and hepatic tumours (including portal vein tumour thrombus) on the Tc-99m MAA SPECT-CT by nuclear medicine technologists under the supervision of experienced nuclear medicine physicians using OsiriX DICOM viewer (Pixmeo, Geneva). For the planning dosimetry in multifocal disease, a maximum of 5 dominant hepatic tumours with a minimum length of 1.0 cm were included in the ROIs. Calculation of tumour absorbed dose was based on Medical Internal Radiation Dose (MIRD) formalism with input of values from tracer counts and volumes obtained in a volume of interest encompassing tumour, non-tumourous liver, and lung (tricompartment model). Weighted average tumour absorbed dose was used for the calculation in multipartition models. Post-treatment Y-90 Bremsstrahlung SPECT-CT or positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) scans were performed within 24 h and used for evaluation of the Y-90 RE. Tumour absorbed dose was obtained from 32 available Y-90 PET-CT scans using SurePlan Liver Y-90 v6.9.9 (MIM Software, Columbus, OH, USA) utilising voxel-based dosimetry with tumour ROIs drawn in reference to the planning Tc-99m MAA SPECT/CT. This mean tumour absorbed dose was reported on a per-patient basis including multifocal lesions and single lesions supplied by multiple vessels. Lung absorbed dose was calculated using the Tc-99m MAA SPECT/CT with tricompartmental modelling. The lung shunt for this detailed calculation relied on count analysis from SPECT/CT rather than the planar images (geometric mean of tracer counts from the planar images was used for liver lung shunt fraction to determine the inclusion or exclusion of patient for further Y-90 RE on the day of hepatic angiography with MAA labelled liver lung shunt study). The lung volume was based on ROI drawings on the CT component of the SPECT/CT. The maximum absorbed dose permitted to the lungs was 20 Gy while the cap for normal liver absorbed dose was aimed to be no more than 30 Gy for whole liver treatments.

Outcome Measures

We grouped our patients based on tumour burden (Milan and up-to-seven criteria) and tumour distribution (unilobar vs. bilobar disease) as previously described in an HCC cohort treated with surgical resection [31]. The Milan criteria described solitary HCC of not more than 5 cm or not more than 3 lesions none of which are more than 3 cm and the absence of macrovascular invasion or extra-hepatic disease [32]. The up-to-seven (UT7) criteria described a scoring system of HCC without macrovascular invasion where “seven” is the sum of the largest tumour diameter (in cm) and the number of tumours [33]. To elucidate the impact of tumour burden, distribution, and the presence of portal venous invasion (PVI) on OS, patients were subgrouped as: (1) HCC within Milan criteria (MC) (<Milan); (2) unilobar HCC beyond MC but within UT7 (<UT7-u); (3) bilobar HCC beyond MC within UT7 (<UT7-b); (4) unilobar HCC beyond MC and UT7 (>UT7-u); (5) bilobar HCC beyond MC and UT7 (>UT7-b); (6) HCC with portal vein invasion (PVI) and Child-Pugh class A (PVI-CPA); and (7) HCC with PVI and Child-Pugh class B (PVI-CPB). Patients with PVI were subdivided into branch or main vessel invasion. Separately, we subdivided the patients based on the tumour absorbed dose into two groups: those who received ≥150 Gy and those who did not, and we compared tumour absorbed dose calculated by the tricompartment method using Tc-99m MAA SPECT/CT against voxel-based dosimetry from Y-90 PET-CT in 32 patients. The threshold of 150 Gy was chosen because the mean tumour dose was 154.7 ± 80.4 Gy (Table 1). This threshold was also consistent with that shown to confer >90% disease control rate in the SARAH study. Patients whose HCC were downstaged with Y-90 RE and received further treatment with curative intent (surgical resection, thermal ablation, or liver transplantation) were separately analysed from those who did not receive such treatment irrespective of successful downstaging. Analysed outcomes included OS and progression-free survival (PFS), defined, respectively, as the time between Y-90 RE and death or disease progression/death. Patients who were alive and progression-free at the time of analysis were censored at the last follow-up date. Visit status was updated until data lock on December 21, 2022. Complications arising from Y-90 RE, namely RE-induced liver disease (REILD) and radiation pneumonitis (RP), were recorded. REILD was defined as the onset of ascites and hyperbilirubinemia (serum bilirubin ≥50 mmol/L) 2 weeks–4 months post-Y-90 RE in the absence of tumour progression or bile duct obstruction [34]. RP was diagnosed in patients with respiratory symptoms within 6 months of Y-90 RE and/or pulmonary infiltrates for which RP could not be excluded radiologically [35, 36].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Baseline characteristics | N = 413 | Proportions |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Mean (SD), years | 65.6 (11.0) | |

| Median (IQR), years | 66 (59.9–72.7) | |

| <65 years | 182 | 44.1% |

| ≥65 years | 231 | 55.9% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 345 | 83.5% |

| Female | 68 | 16.5% |

| ECOG | ||

| 0 and 1 | 405 | 98.1% |

| 2 and 3 | 8 | 1.9% |

| Child-Pugh | ||

| A | 358 | 86.7% |

| B | 55 | 13.3% |

| ALBI | ||

| 1 | 120 | 29.1% |

| 2 | 271 | 65.6% |

| 3 | 22 | 5.3% |

| Aetiology | ||

| HepB | 203 | 49.2% |

| HepC | 53 | 12.8% |

| HepB+C | 4 | 1.0% |

| Alcohol | 29 | 7.0% |

| NAFLD | 82 | 19.9% |

| Others | 42 | 10.2% |

| AFP | ||

| <400 μg/L | 246 | 66.5% |

| ≥400 μg/L | 124 | 33.5% |

| Tumour burden | ||

| Solitary | 126 | 30.7% |

| 2–5 tumours | 82 | 20.0% |

| >5 tumours | 202 | 49.3% |

| Tumour size, cm | ||

| Median (IQR) | 7 (4.3–10.7) | |

| Mean (SD) | 7.9 (4.5) | |

| Largest tumour size | ||

| <8 cm | 231 | 57.0% |

| ≥8 cm | 174 | 43.0% |

| Tumour location | ||

| Unilobar | 215 | 52.4% |

| Bilobar | 195 | 47.6% |

| BCLC | ||

| A | 76 | 18.4% |

| B | 161 | 39.0% |

| C | 173 | 41.9% |

| D | 3 | 0.7% |

| Subgroup by Milan and UT7 criteria | ||

| Within Milan | 14 | 3.4% |

| Beyond Milan within UT7 | 31 | 7.5% |

| Beyond UT7 | 214 | 51.8% |

| Portal vein invasion | 154 | 37.3% |

| Portal vein invasion | ||

| No | 259 | 62.7% |

| Branch | 122 | 29.5% |

| Main and beyond | 32 | 7.8% |

| Y-90 administered activity, GBq | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.6 (1.0) | |

| Median (IQR) | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) | |

| Predicted tumour absorbed dose, Gy | ||

| Mean (SD) | 154.7 (80.4) | |

| Median (IQR) | 131.9 (102.9–196.9) | |

| Subsequent curative treatment | ||

| No | 343 | 83.1% |

| Yes | 70 | 17.0% |

| Thermal ablation | 42 | 60.0% |

| Resection | 25 | 35.7% |

| Transplant | 3 | 4.3% |

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; AFP, α-fetoprotein; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver cancer; UT7, up-to-seven.

Statistical Analysis

Patient demographics were summarised with descriptive statistics. Fisher’s exact test and χ2 test were used to compare categorical variables while ANOVA and Mann-Whitney U test were used for continuous variables. Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple pairwise comparisons. Survival curves were analysed with the Kaplan-Meier technique and compared using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate cox proportional hazard regression model was used to identify potential prognostic factors for survival between variables and survival. The selection of variables into the multivariate model was determined following the univariate analysis when statistically significant and/or clinically important variables were included in the multivariate model. All statistical analyses were carried out with Stata/SE16.1 software (StatCorp LLC).

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted according to the ethical guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB), approval number 2023/2062.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

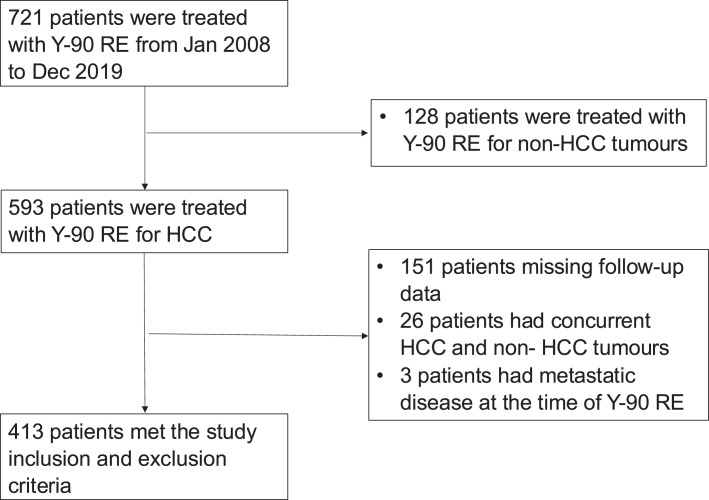

A total of 721 patients underwent Y-90 RE during the study period and 413 met the study inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The mean and median follow-up duration was 28.6 months (±30.6 months) and 16.4 months (range, 6.67–41.7 months), respectively.

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram.

The baseline characteristics and tumour characteristics are listed in Table 1 and online supplementary Table 1 (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000541539). The median age of the cohort was 66 years old (range, 59.9–72.7). Patients were predominantly male (83.5%), were of Hep B aetiology (49.2%) and were Child-Pugh A (86.7%). The median tumour size for solitary HCC was 8.0 cm (range, 5.6–11.2), and the largest solitary tumour treated was 21.5 cm. Most patients had multifocal lesions (69.3%) and almost half of the patients had bilobar disease (47.6%); 154 patients (37.3%) were BCLC C HCC with tumour invasion of the portal venous system. Two hundred and ninety-six (296) patients had available tri-compartment dosimetry data by MIRD calculation, and 32 had dosimetry data from Y-90 PET-CT. The mean and median Y-90 administered activity were 1.6 (±1.0 GBq) and 1.41 GBq (range, 0.94–2.2 GBq), while the mean and median tumour absorbed dose were 154.7 (±80.4 Gy) and 131.9 Gy (range, 102.9–196.9 Gy), respectively.

Survival Outcomes

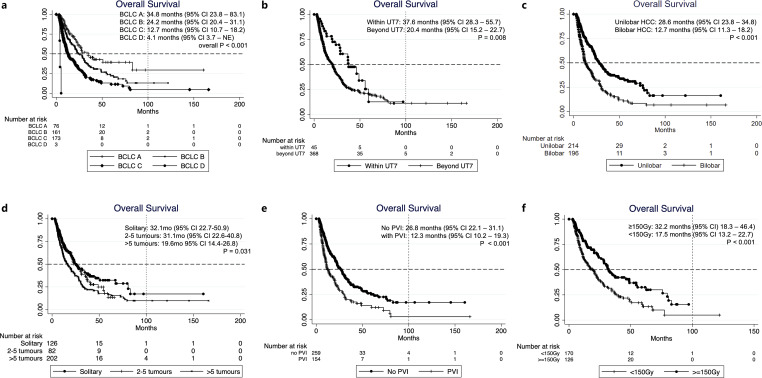

At the time of analysis, 62% of the patients were demised. The median OS of the entire cohort was 20.9 months (95% CI: 18.2–24) and was not significantly different with age and gender (Table 2). OS based on BCLC staging were: BCLC A 34.8 months (95% CI: 23.8–83.1), BCLC B 24.2 months (95% CI: 20.4–31.1), BCLC C 12.7 months (95% CI: 10.7–18.2), and BCLC D 4.1 months (95% CI: 3.7 – NE, n = 3) (Table 2; Fig. 2). The best OS was observed in the group within UT7 (37.6 months; 95% CI: 28.3–55.7). Bilobar HCC had worse outcome (OS 12.7 months; 95% CI: 11.3–18.2) than unilobar HCC (OS 28.6 months; 95% CI: 23.8–34.8; p < 0.001). Of note, patients with solitary HCC (OS 32.1 months, 95% CI: 22.7–50.9) and multifocal HCC with 2–5 tumours (OS 31.1 months; 95% CI: 22.6–40.8) had comparable OS (p = 0.646), and both groups survived longer than those with > 5 tumours (OS 19.6 months; 95% CI: 14.4–26.8; p = 0.031). HCC without PVI had OS of 26.8 months (95% CI: 22.1–31.1) whereas those with PVI had OS of 12.3 months (95% CI: 10.2–19.3, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Among patients with PVI, comparable OS were observed in those with branch PVI (11.8 months; 95% CI: 10.2–18.2) and main PVI (15.3 months; 95% CI: 7.2 – NE, p = 0.381). Patients who received tumour absorbed dose ≥150 Gy had a better OS (32.2 months, 95% CI: 18.3–46.4) compared to those received <150 Gy (OS 17.5 months, 95% CI: 13.2–22.7, p < 0.001), and solitary HCC that received ≥150 Gy had an excellent mOS of 46.4 months (95% CI: 23.9 – NE) (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Table 2.

OS by baseline characters and subgroups

| All patients | <Milan | <UT7-u1 | >UT7-u | >UT7-b | PVI-CPA | PVI-CPB | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OS | 95% CI | p value | n | OS | 95% CI | p value | n | OS | 95% CI | p value | n | OS | 95% CI | p value | n | OS | 95% CI | p value | n | OS | 95% CI | p value | n | OS | 95% CI | p value | |

| All | 413 (100) | 20.9 | 18.2–24 | NA | 14 | 37.0 | 19.6-NE | NA | 28 | 46.4 | 23.9–59.5 | NA | 110 | 31.2 | 23.8–40.1 | NA | 104 | 15.2 | 11.5–20.9 | NA | 133 | 14.8 | 11.3–20.9 | NA | 21 | 6.1 | 4.1–8.1 | NA |

| Age | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <65 years | 182 (44.1) | 20.4 | 15.0–24.0 | 0.641 | 5 | NE | NE | NE | 6 | 49.0 | 23.9-NE | 0.640 | 44 | 23.8 | 17.7–67.8 | 0.347 | 50 | 13.6 | 9.8–20.9 | 0.504 | 67 | 20.4 | 11.0–30.6 | 0.053 | 9 | 6.0 | 3.0–8.3 | 0.386 |

| ≥65 years | 231 (55.9) | 22.1 | 17.3–27.2 | 9 | 37.0 | 3.7-NE | 22 | 46.4 | 13.7–59.5 | 66 | 33.3 | 25.7–77.3 | 54 | 19.2 | 11.5–27.9 | 66 | 13.5 | 10.2–19.8 | 12 | 6.1 | 4.1–10.8 | |||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 345 (83.5) | 20.8 | 17.3–24.2 | 0.757 | 9 | 37.0 | 3.7-NE | 0.500 | 21 | 46.4 | 28.6–59.5 | 0.387 | 92 | 32.4 | 8.2-NE | 0.548 | 89 | 14.4 | 11.1–20.4 | 0.301 | 112 | 17.1 | 6.7–28.4 | 0.492 | 19 | 6.2 | 4.5–8.1 | 0.374 |

| Female | 68 (16.5) | 22.2 | 11.0–27.9 | 5 | NE | 8.5-NE | 7 | 23.9 | 3.7-NE | 18 | 26.8 | 24.2–50.9 | 15 | 20.9 | 12.2-NE | 21 | 10.3 | 11.8–20.9 | 2 | 4.1 | NE | |||||||

| ECOG | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0–1 | 405 (98.1) | 22.1 | 19.5–25.3 | <0.001 | 14 | 37.0 | 19.6-NE | NA | 26 | 49.0 | 28.6–59.5 | 0.016 | 109 | 31.2 | 24.2–50.9 | 0.010 | 103 | 15.2 | 11.5–21.9 | 0.204 | 133 | 14.8 | 11.3–20.9 | NA | 17 | 6.1 | 4.1–8.3 | 0.802 |

| 2–3 | 8 (1.9) | 5.3 | 3.4–10.8 | 2 | 3.7 | 3.7-NE | 1 | NE | NE | 1 | NE | NE | 0 | 4 | 5.3 | 4.1-NE | ||||||||||||

| Child-Pugh class | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A | 358 (86.7) | 23.7 | 20.6–28.4 | <0.001 | 13 | 37.0 | 8.5-NE | 0.214 | 24 | 46.4 | 23.9–59.5 | 0.615 | 98 | 33.3 | 26.2–67.6 | <0.001 | 88 | 11.2 | 12.5–24.0 | 0.003 | 133 | 14.8 | 11.3–20.9 | NA | 0 | |||

| B | 55 (13.3) | 8.1 | 6.0–10.9 | 1 | NE | NE | 4 | 11.4 | 3.7-NE | 12 | 10.9 | 3.4-NE | 16 | 7.1 | 4.3–16.5 | 0 | 21 | 8.1 | 6.0–10.9 | NA | ||||||||

| ALBI | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 120 (29.1) | 31.9 | 26.2–48.8 | vs. ALBI 1 | 8 | 28.3 | 3.7-NE | 0.348 | 12 | 49.0 | 10.6–59.5 | 0.663 | 38 | 75.9 | 31.2-NE | 0.004 | 26 | 30.1 | 11.1–48.8 | 0.046 | 34 | 23.3 | 17.1–31.9 | 0.327 | 1 | NE | 0.068 | |

| 2 | 271 (65.6) | 17.3 | 12.7–21.9 | <0.001 | 6 | NE | 8.5-NE | 16 | 36.8 | 11.4-NE | 69 | 23.8 | 20.6–32.1 | 71 | 12.7 | 10.7–20.6 | 95 | 11.9 | 9.9–19.5 | 13 | 6.2 | 3.5–8.1 | ||||||

| 3 | 22 (5.33) | 13.5 | 5.3–28.1 | 0.004 | 3 | 8.3 | 8.3-NE | 7 | 16.5 | 3.4-NE | 4 | 11.3 | 4.8-NE | 7 | 6 | 4.5-NE | ||||||||||||

| AFP | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <400 μg/L | 246 (66.5) | 24 | 20.6–28.5 | 0.005 | 9 | 37.0 | 3.7-NE | 0.903 | 23 | 46.4 | 23.9–59.5 | 0.764 | 72 | 27.2 | 22.6–34.8 | 0.245 | 64 | 16.2 | 11.4–22.8 | 0.837 | 67 | 20.4 | 13.5–30.3 | 0.217 | 8 | 7.3 | 3.2–28.1 | 0.047 |

| ≥400 μg/L | 124 (33.5) | 14.4 | 10.7–21.7 | 4 | NE | 8.5-NE | 4 | 49.0 | 3.7-NE | 27 | 34.7 | 11.0–75.9 | 33 | 14.4 | 8.4–28.8 | 45 | 15.3 | 9.9–21.7 | 11 | 6.0 | 3.5–6.2 | |||||||

| Tumour burden (without portal vein invasion) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Solitary | 84 (32.4) | 32.1 | 22.7–50.9 | vs. Solitary | 12 | 37.0 | 8.5-NE | 0.323 | 16 | 46.4 | 10.6-NE | 0.883 | 56 | 27.6 | 20.8–50.9 | 0.563 | 0 | 40 | 20.4 | 10.5–38.3 | 0.198 | 2 | 4.9 | 4.9-NE | 0.826 | |||

| 2–5 tumours | 58 (22.4) | 31.1 | 22.6–40.8 | 0.323 | 2 | NE | NE | 11 | 49.0 | 20.2-NE | 16 | 30.4 | 22.1-NE | 27 | 20.9 | 9.6–31.1 | 0.759 | 19 | 14.8 | 10.2–21.4 | 5 | 7.2 | 4.1-NE | |||||

| >5 tumours | 117 (45.2) | 19.6 | 14.4–26.8 | 0.004 | 0 | 1 | NE | NE | 38 | 32.4 | 20.6–77.3 | 77 | 15.1 | 11.5–20.4 | 71 | 13.5 | 9.5–24.0 | 14 | 6.1 | 3.5–10.8 | ||||||||

| Tumour size | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <8 cm | 231 (57.0) | 25.7 | 20.4–31.1 | 0.007 | 14 | 37.0 | 19.6-NE | NA | 28 | 46.4 | 23.9–59.5 | NA | 49 | 34.7 | 24.2–77.3 | 0.297 | 61 | 20.6 | 11.5–28.4 | 0.063 | 70 | 20.6 | 11.5–28.4 | 0.470 | 6 | 5.3 | 3.2-NE | 0.803 |

| ≥8 cm | 174 (43.0) | 15.2 | 12.3–21.7 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 26.8 | 17.5–34.8 | 42 | 12.2 | 9.5–16.5 | 57 | 12.2 | 9.5–16.5 | 15 | 6.2 | 4.1–8.1 | |||||||||||

| Tumour location | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unilobar | 215 (52.4) | 28.6 | 23.8–34.8 | <0.001 | 13 | 37.0 | 8.5-NE | 0.561 | 28 | 46.4 | 23.9–59.5 | NA | 110 | 31.2 | 23.8–40.1 | NA | 0 | 59 | 20.9 | 13.5–25.3 | 0.194 | 4 | 4.9 | 3.2-NE | 0.497 | |||

| Bilobar | 195 (47.6) | 12.7 | 11.3–18.2 | 1 | NE | NE | 0 | 0 | 104 | 15.2 | 11.5–20.9 | NA | 71 | 11.8 | 10.1–19.5 | 17 | 6.1 | 4.1–8.1 | ||||||||||

| Portal vein invasion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 259 (62.7) | 26.8 | 22.1–31.1 | Yes vs. No <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 154 (37.3) | 12.3 | 10.2–19.3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch | 122 (29.5) | 11.8 | 10.2–18.2 | Branch vs. Main 0.381 | 106 | 13.7 | 11.0–21.4 | 0.133 | 16 | 6.1 | 4.1–10.8 | 0.566 | ||||||||||||||||

| Main and beyond | 32 (7.8) | 15.3 | 7.2 - NE | 27 | 19.5 | 7.2-NE | 5 | 7.2 | 3.2-NE | |||||||||||||||||||

| Subsequent Curative Treatment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 343 (83.1) | 79.7 | 13.5–20.4 | <0.001 | 8 | NE | 37.0-NE | NA | 6 | 37.6 | 13.7-NE | 0.122 | 26 | NE | 31.2-NE | <0.001 | 12 | 49.3 | 14.4-NE | <0.001 | 17 | 79.7 | 15.3-NE | <0.001 | 1 | NE | NE | 0.386 |

| No | 70 (17.0) | 17.1 | 40.4-NE | 6 | 19.6 | 3.7-NE | 22 | 55.7 | 23.9-NE | 84 | 25.7 | 20.6–33.3 | 92 | 12.7 | 11.1–19.6 | 116 | 13.5 | 10.3–19.5 | 20 | 6.1 | 4.1–7.3 | |||||||

| Tumour absorbed dose (n = 296, 71.7%) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <150 Gy | 170 (57.4) | 17.5 | 13.2–22.7 | <0.001 | 5 | 37.0 | 19.6-NE | 0.744 | 9 | 49.0 | 7.4-NE | 0.609 | 48 | 22.7 | 17.3–34.7 | 0.003 | 36 | 12.7 | 8.4–24.0 | 0.004 | 61 | 12.3 | 9.5–24.0 | 0.501 | 11 | 7.3 | 4.1–14.9 | 0.807 |

| ≥150 Gy | 126 (42.6) | 32.2 | 18.3–46.4 | 7 | NE | 3.7-NE | 14 | 37.6 | 10.6-NE | 38 | 75.9 | 32.4-NE | 30 | 30.1 | 11.4–54.6 | 33 | 20.4 | 13.9–31.9 | 2 | 8.3 | NE | |||||||

| Tumour absorbed dose (solitary HCC) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <150 Gy | 35 (48.6) | 22.7 | 13.7–37.0 | 0.094 | 5 | 37.0 | 19.6-NE | 0.774 | 3 | NE | 13.7-NE | 0.446 | 27 | 22.7 | 11.0–34.8 | 0.035 | ||||||||||||

| ≥150 Gy | 37 (51.4) | 46.4 | 23.9-NE | 6 | 3.7-NE | 11 | 23.9 | 3.8-NE | 20 | 83.1 | 26.2-NE | |||||||||||||||||

OS, overall survival; CI, confidence interval; NE, non-estimable; NA, non-applicable; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; AFP, α-fetoprotein; PVI, portal vein invasion. Subgroups: <Milan, within Milan Criteria; <UT7-u, unilobar HCC beyond Milan Criteria but within Up-to-seven Criteria (UT7); <UT7-b, bilobar HCC beyond Milan Criteria but within UT7; >UT7-u, unilobar HCC beyond Milan Criteria and UT7; >UT7-b, bilobar HCC beyond Milan Criteria and UT7; PVI-CPA, portal vein invasion (PVI) and Child-Pugh class A; PVI-CPB, with PVI and Child-Pugh class B.

1Bilobar HCCs beyond Milan and within UT7 criteria were excluded in this table due to low number of patients (n = 3).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier OS curves of HCC patients treated with Y-90 radioembolization, stratified by (a) BCLC; (b) UT7 Criteria; (c) tumour distribution (unilobar vs. bilobar tumours); (d) tumour burden; (e) portal vein invasion; (f) Y-90 tumour absorbed dose.

Univariate analysis (Table 3) showed OS was significantly shorter in patients with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 2–3 versus 0–1 (HR 6.4; 95% CI: 3.1–13.1), Child-Pugh B versus A (HR 2.8; 95% CI: 2.0–3.9), ALBI grade 2 (HR 1.7; 95% CI: 1.3–2.3) and grade 3 (HR 2.3; 95% CI: 1.3–4.0) versus grade 1, α-fetoprotein (AFP) ≥ 400 μg/L (HR 1.49; 95% CI: 1.1–2.0), tumour ≥ 8 cm (HR 1.42; 95% CI: 1.1–1.8), bilobar versus unilobar HCC (HR 1.94; 95% CI: 1.5–2.5), tumour absorbed dose below 150 Gy (HR 1.78; 95% CI: 1.31–2.41) and HCC with PVI (HR 1.88; 95% CI: 1.44–2.45). In patients with HCC without PVI, survival differed significantly with ECOG performance status, liver function (Child-Pugh class, ALBI grade), tumour size, tumour distribution, and tumour absorbed dose; whereas in patients with HCC and PVI, ECOG performance status, Child-Pugh class, and AFP level were important predictors of OS (Table 3). Multivariate analysis was performed separately in HCC with or without PVI. For HCC without PVI, ECOG performance status, ALBI grade, tumour distribution, and tumour absorbed dose remained independent predictors of OS. Child-Pugh class and AFP were significant predictors in HCC with PVI.

Table 3.

Predictors of OS from univariate and multivariate analysis in HCC patients with or without portal vein invasion

| OS | No PVI (n = 259) | With PVI (n = 154) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| univariate | univariate | multivariate | univariate | multivariate | ||||||||||||||

| n (%) | HR | 95% CI | p value | n (%) | HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | n (%) | HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Age | ||||||||||||||||||

| <65 years | 182 (44.1) | 1 | 106 (40.9) | 1 | 76 (49.4) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| ≥65 years | 231 (55.9) | 0.94 | 0.73–1.21 | 0.641 | 153 (59.1) | 0.81 | 0.58–1.12 | 0.202 | 78 (50.7) | 1.41 | 0.96–2.09 | 0.082 | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 345 (83.5) | 1.06 | 0.74–1.51 | 0.757 | 214 (82.6) | 1.11 | 0.70–1.76 | 0.663 | 131 (85.1) | 0.90 | 0.51–1.59 | 0.725 | ||||||

| Female | 68 (16.5) | 1 | 45 (17.4) | 1 | 23 (14.9) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| ECOG | ||||||||||||||||||

| 0–1 | 405 (98.1) | 1 | 255 (98.5) | 1 | 1 | 150 (97.4) | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2–3 | 8 (1.9) | 6.38 | 3.11–13.11 | <0.001 | 4 (1.5) | 9.32 | 3.37–25.80 | 0.001 | 7.61 | 1.80–32.2 | 0.006 | 4 (2.6) | 3.76 | 1.36–10.41 | 0.011 | 2.72 | 0.76–9.82 | 0.126 |

| Child-Pugh | ||||||||||||||||||

| A | 358 (86.7) | 1 | 225 (86.9) | 1 | 1 | 133 (86.4) | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| B | 55 (13.3) | 2.80 | 1.99–3.94 | <0.001 | 34 (13.1) | 2.68 | 1.69–4.25 | <0.001 | 2.09 | 0.99–4.43 | 0.054 | 21 (13.6) | 3.08 | 1.86–5.12 | <0.001 | 2.87 | 1.59–5.19 | <0.001 |

| ALBI | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 120 (29.1) | 1 | 85 (32.8) | 1 | 1 | 35 (22.7) | 1 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 271 (65.6) | 1.73 | 1.30–2.29 | <0.001 | 163 (62.9) | 2.96 | 1.20–2.43 | 0.003 | 1.32 | 0.87–2.01 | 0.192 | 108 (70.1) | 1.62 | 0.99–2.66 | 0.056 | |||

| 3 | 22 (5.3) | 2.29 | 1.31–4.02 | 0.004 | 11 (4.3) | 3.05 | 1.63–9.28 | 0.002 | 2.42 | 1.34–16.8 | 0.016 | 11 (7.1) | 0.89 | 0.65–3.18 | 0.372 | |||

| AFP | ||||||||||||||||||

| <400 μg/L | 246 (66.5) | 1 | 171 (71.6) | 1 | 75 (57.3) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| ≥400 μg/L | 124 (33.5) | 1.49 | 1.13–1.97 | 0.005 | 68 (28.5) | 1.29 | 0.89–1.88 | 0.185 | 56 (42.8) | 1.60 | 1.03–2.47 | 0.036 | 1.84 | 1.17–2.88 | 0.008 | |||

| Tumour burden | ||||||||||||||||||

| Solitary | 126 (30.7) | 1 | 84 (32.4) | 1 | 1 | 42 (27.8) | ||||||||||||

| 2–5 tumours | 82 (20.0) | 1.20 | 0.84–1.72 | 0.323 | 58 (22.4) | 1.11 | 0.71–1.73 | 0.46 | 0.73 | 0.42–1.28 | 0.271 | 24 (15.9) | 1.68 | 0.90–3.15 | 0.103 | |||

| >5 tumours | 202 (49.3) | 1.55 | 1.15–2.08 | 0.004 | 117 (45.2) | 1.52 | 1.04–2.21 | 0.031 | 0.72 | 0.39–1.30 | 0.274 | 85 (56.3) | 1.48 | 0.92–2.38 | 0.106 | |||

| Tumour size | ||||||||||||||||||

| <8 cm | 231 (57.0) | 1 | 155 (60.3) | 1 | 1 | 76 (51.4) | 1 | |||||||||||

| ≥8 cm | 174 (43.0) | 1.42 | 1.10–1.82 | 0.007 | 102 (39.7) | 1.40 | 1.01–1.93 | 0.042 | 1.00 | 0.96–1.05 | 0.962 | 72 (48.7) | 1.31 | 0.88–1.95 | 0.182 | |||

| Tumour distribution | ||||||||||||||||||

| Unilobar | 215 (52.4) | 1 | 152 (58.7) | 1 | 1 | 63 (41.7) | 1 | |||||||||||

| Bilobar | 195 (47.6) | 1.94 | 1.51–2.49 | <0.001 | 107 (41.3) | 2.14 | 1.55–2.96 | <0.001 | 2.72 | 1.63–4.56 | <0.001 | 88 (58.3) | 1.40 | 0.94–2.10 | 0.099 | |||

| Tumour absorbed dose (n = 296, 71.7%) | ||||||||||||||||||

| <150 Gy | 170 (57.4) | 1.78 | 1.31–2.41 | <0.001 | 98 (51.9) | 1.98 | 1.35–2.90 | 0.001 | 2.07 | 1.34–3.19 | 0.001 | 72 (67.3) | 1.32 | 0.79–2.20 | 0.294 | |||

| ≥150 Gy | 126 (42.6) | 1 | 91 (48.2) | 1 | 1 | 35 (32.7) | 1 | |||||||||||

| Tumour absorbed dose (solitary HCC) | ||||||||||||||||||

| <150 Gy | 56 (52.8) | 1.45 | 0.85–2.48 | 0.171 | 35 (49.3) | 1.81 | 0.93–3.52 | 0.082 | 21 (58.3) | 0.93 | 0.38–2.30 | 0.871 | ||||||

| ≥150 Gy | 50 (47.2) | 1 | 36 (50.7) | 1 | 15 (41.7) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Portal vein invasion | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 259 (62.7) | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 154 (37.3) | 1.80 | 1.40–2.31 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| Branch | 122 (29.5) | 1.88 | 1.44–2.45 | <0.001 | 122 (29.5) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Main and beyond | 32 (7.8) | 1.46 | 0.87–2.45 | 0.151 | 32 (7.8) | 0.79 | 0.46–1.35 | 0.381 | ||||||||||

| Subsequent curative treatment | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 343 (83.1) | 1 | 207 (79.9) | 1 | 1 | 136 (88.3) | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 70 (17.0) | 0.25 | 0.16–0.37 | <0.001 | 52 (20.1) | 0.25 | 0.15–0.41 | <0.001 | 0.30 | 0.17–0.52 | <0.001 | 18 (11.7) | 0.25 | 0.11–0.54 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 0.16–0.78 | 0.010 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; AFP, α-fetoprotein; PVI, portal vein invasion.

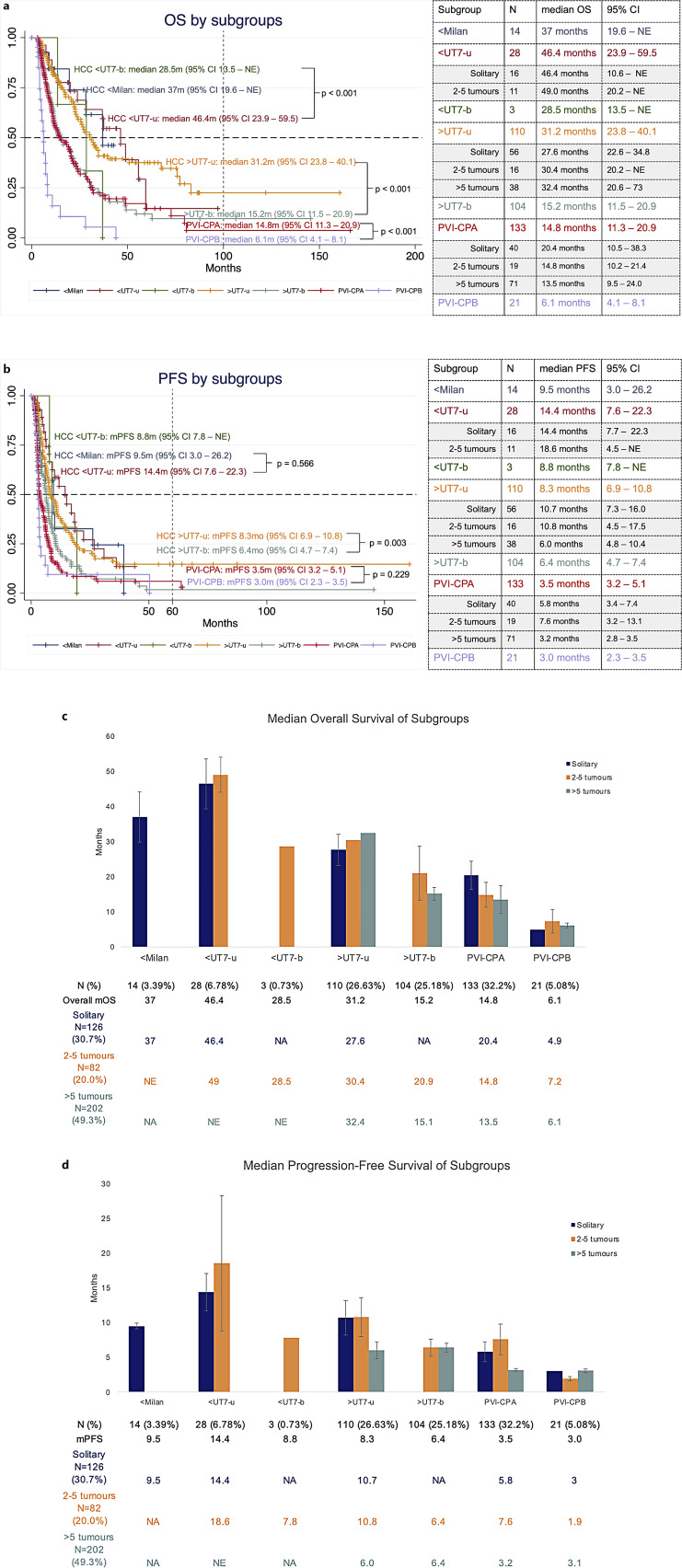

To evaluate the impact of tumour burden, distribution, and PVI on OS, patients were subgrouped as described in the Methods. The highest median OS was observed in unilobar HCC within UT7 (<UT7-u) group at 46.4 months (95% CI: 23.9–59.5). Patients with unilobar HCC beyond UT7 criteria and without PVI (>UT7-u) had significantly longer mOS (31.2 months, 95% CI: 23.8–40.1) compared to >UT7-b group (15.2 months, 95% CI: 11.5–20.9; p < 0.001). For HCC with PVI, patients with Child-Pugh B liver function (PVI-CPB) had significantly poorer mOS (6.1 months; 95% CI: 4.1–8.1) than Child-Pugh A (PVI-CPA) (14.8 months; 95% CI: 11.3–20.9, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

a, b Kaplan-Meier survival curves of HCC patients treated with Y-90 radioembolization, subgrouped based on Milan Criteria, UT7 criteria and tumour distribution; HCC with PVI was stratified with Child-Pugh class. c, d Bar chart showing median OS and PFS in subgroups of patients, stratified by tumour burden.

The median PFS of the entire cohort was 6.1 months (95% CI: 5.7–6.7). Similarly to OS, patients with unilobar HCC within UT7 (<UT7-u) had the best PFS (14.4 months, 95% CI: 7.6–22.3 months). Patients who received dose ≥150 Gy had improved PFS (8.5 months, 95% CI: 7.3–12.8) compared to those who received <150 Gy (5.7 months, 95% CI: 4.5–6.5, p = 0.004), and solitary HCC that received dose ≥150 Gy had significantly longer PFS (18.4 months; 95% CI: 10.7–26.8) than those with <150 Gy (9.5 months; 95% CI: 6.7–14.4; p = 0.049) (online suppl. Table 2; Fig. 1). Variables predicting worse PFS were age <65 years old (HR 1.32; 95% CI: 1.07–1.63; p = 0.009), Child-Pugh B (HR 1.41; 95% CI: 1.04–1.91; p = 0.028), ALBI grade 2 (HR 1.52; 95% CI: 1.20–1.93; p = 0.001), AFP ≥ 400 μg/L (HR 1.69; 95% CI: 1.34–2.13; p < 0.001), >5 tumours (HR 1.88; 95% CI: 1.47–2.41; p < 0.001), tumour size ≥8 cm (HR 1.41; 95% CI: 1.14–1.75; p = 0.001), bilobar disease (HR 1.74; 95% CI: 1.41–2.14; p < 0.001), tumour absorbed dose <150 Gy (HR 1.45; 95% CI: 1.13–1.88; p = 0.001), and the presence of PVI (HR 1.94; 95% CI: 1.57–2.41; p < 0.001) (online suppl. Table 3). Multivariate analysis showed AFP ≥400 μg/L (HR 1.46; 95% CI: 1.06–2.02) and tumour absorbed dose <150 Gy (HR 1.39, 95% CI: 1.06–1.82, p = 0.018) were independent predictors of poor PFS for HCC without PVI, and tumour size ≥ 8 cm (HR 1.98, 95% CI: 1.33–2.94) was the only independent predictor for poor PFS for HCC with PVI (online suppl. Table 3).

Tumour absorbed dose calculated by the tri-compartment method from Tc-99m MAA SPECT/CT was compared against voxel-based dosimetry from Y-90 PET-CT scans in 32 patients. The mean and median predicted tumour dose was 214.08 Gy (±124.1 Gy) and 191.75 Gy (range: 108.8–267.9 Gy). All patients with planned tumour absorbed dose ≥150 Gy were verified to receive doses exceeding 150 Gy based on Y-90 PET-CT.

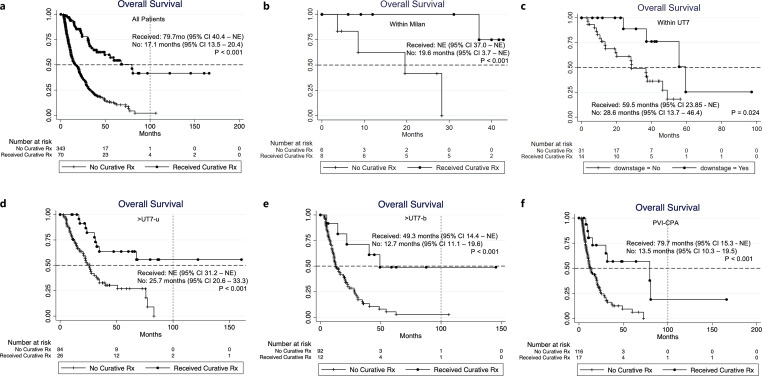

Seventy patients (70/413, 16.9%) in our cohort received further treatment with curative intent after Y-90 RE downstaged the tumours (surgical resection n = 25, transplantation n = 3, thermal ablation n = 42). These patients had a median OS of 79.7 months (95% CI: 40.4 – NE), which was significantly longer than those who did not receive subsequent curative treatments (OS 17.1 months; 95% CI: 13.5–20.4, p < 0.001), and this observation is consistent among all the subgroups (Fig. 4). Baseline characteristics of patients who did and did not receive curative treatments after Y-90 RE are summarised in Table 4.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients with HCC who received curative treatment after Y-90 radioembolization downstage among (a) all patients; (b) < Milan; (c) <UT7-u; (d) >UT7-u; (e) >UT7-b; (f) PVI-CPA; only 1 patient in the PVI-CPB group received further treatment (thermal ablation) after HCC downstaged with Y-90 radioembolization.

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics of patients who received or did not receive subsequent curative treatment after tumour downstaged by Y-90 RE, by overall and subgroups

| overall | <Milan | <UT7-u1 | >UT7-u | >UT7-b | PVI-CPA | PVI-CPB | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsequent curative treatment post-Y-90 RE | |||||||||||||||||||||

| yes | no | p value | yes | no | p value | yes | no | p value | yes | no | p value | yes | no | p value | yes | no | p value | yes | no | p value | |

| N = 70 | N = 343 | N = 8 | N = 6 | N = 6 | N = 22 | N = 26 | N = 84 | N = 12 | N = 92 | N = 17 | N = 116 | N = 1 | N = 20 | ||||||||

| Age | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 64.3 (1.1) | 65.9 (0.6) | 0.258 | 64.4 (5.1) | 68 (3.0) | 0.558 | 66.0 (12.7) | 71.9 (6.2) | 0.120 | 64.0 (9.4) | 68.9 (10.5) | 0.034 | 65.1 (6.3) | 63.7 (12.9) | 0.720 | 64.0 (7.2) | 64.5 (11.2) | 0.595 | 71 | 64.1 (9.0) | NA |

| Median (IQR) | 65.0 (58.5–70.4) | 66.0 (60.0–73.4) | 0.120 | 66 (54.0–77) | 68 (65.3–72) | 0.698 | 66.3 (54.1–79.0) | 71.3 (68–76) | 0.466 | 65 (61.9–70.0) | 69 (61.0–77.4) | 0.057 | 65.5 (61.2–69.5) | 65 (56.8–72.2) | 0.992 | 63 (57–68.2) | 64.9 (58.9–72.2) | 71 | 65.6 (58.7–71.5) | ||

| <65 years | 34 (48.6) | 148 (43.2) | 0.405 | 4 (50.0) | 1 (16.7) | 0.301 | 3 (50) | 3 (13.6) | 0.091 | 12 (46.2) | 32 (38.1) | 0.464 | 6 (50) | 44 (47.8) | 0.887 | 9 (52.9) | 58 (50) | 0.821 | 0 (0) | 9 (45.0) | 0.375 |

| ≥65 years | 36 (51.4) | 195 (56.9) | 4 (50.0) | 5 (83.3) | 3 (50) | 19 (86.4) | 14 (53.9) | 52 (61.9) | 6 (50) | 48 (52.2) | 8 (47.1) | 58 (50) | 1 (100) | 11 (55.0) | |||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 61 (87.1) | 284 (82.8) | 0.372 | 5 (62.5) | 4 (66.7) | 0.872 | 5 (83.3) | 16 (72.7) | 0.595 | 25 (96.2) | 67 (79.8) | 0.067 | 9 (75.0) | 80 (87.0) | 0.268 | 16 (94.1) | 96 (8.8) | 0.3 | 1 (100) | 18 (90.0) | 0.740 |

| Female | 9 (12.9) | 59 (17.2) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 6 (27.3) | 1 (3.9) | 17 (20.2) | 3 (25.0) | 12 (13.0) | 1 (5.9) | 20 (17.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (10.0) | |||||||

| ECOG | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 and 1 | 70 (100) | 335 (97.7) | 0.361 | 8 (100) | 6 (100) | NA | 6 (100) | 20 (90.9) | 0.443 | 26 (100) | 83 (98.8) | 0.576 | 12 (100) | 91 (98.9) | 0.717 | 17 (100) | 116 (100) | NA | 1 (100) | 16 (80.0) | 0.619 |

| 2 and 3 | 0 (0) | 8 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (20.0) | |||||||

| Child-Pugh | |||||||||||||||||||||

| A | 66 (94.3) | 292 (85.1) | 0.051 | 7 (87.5) | 6 (100) | 0.369 | 6 (100) | 18 (81.8) | 0.549 | 24 (92.23) | 74 (88.1) | 0.728 | 12 (100) | 76 (82.6) | 0.116 | 17 (100) | 116 (100) | NA | |||

| B | 4 (5.7) | 51 (14.9) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (18.2) | 2 (7.7) | 10 (11.9) | 0 (0) | 16 (17.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| ALBI | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 27 (38.6) | 93 (27.1) | 0.066 | 4 (50) | 4 (66/7) | 0.533 | 3 (50) | 9 (40.9) | 0.690 | 14 (53.9) | 24 (28.6) | 0.048 | 3 (25) | 23 (25) | 0.606 | 3 (17.7) | 31 (216.7) | 0.582 | 0 (0) | 1 (5.0) | 0.724 |

| 2 | 42 (60.0) | 229 (66.8) | 4 (50) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50) | 13 (59.1) | 12 (46.2) | 57 (67.9) | 9 (75) | 62 (67.4) | 13 (76.5) | 82 (70.7) | 1 (100) | 12 (60.0) | |||||||

| 3 | 1 (1.4) | 21 (6.12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 7 (7.6) | 1 (5.9) | 3 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 7 (35.0) | |||||||

| Aetiology | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Viral (HepB and/or HepC) | 49 (70.0) | 211 (61.5) | 0.180 | 7 (87.5) | 4 (66.7) | 0.538 | 6 (100) | 11 (50) | 0.026 | 16 (61.5) | 42 (50.0) | 0.303 | 6 (50) | 32 (34.8) | 0.303 | 14 (82.4) | 79 (68.1) | 0.232 | 0 (0) | 14 (70.0) | 0.147 |

| Non-viral | 21 (30.0) | 132 (38.5) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 11 (50) | 10 (38.5) | 42 (50.0) | 6 (50) | 60 (65.2) | 3 (17.7) | 37 (31.9) | 1 (100) | 6 (30.0) | |||||||

| AFP | |||||||||||||||||||||

| <400 μg/L | 43 (70.5) | 203 (65.7) | 0.468 | 5 (71.4) | 4 (66.7) | 0.853 | 5 (83.3) | 18 (85.7) | 0.885 | 18 (81.8) | 54 (70.1) | 0.278 | 7 (58.3) | 57 (67.1) | 0.550 | 7 (53.9) | 39 (39.4) | 0.640 | 1 (100) | 7 (38.9) | 0.228 |

| ≥400 μg/L | 18 (29.5) | 106 (34.3) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (14.3) | 4 (18.2) | 23 (29.9) | 5 (41.7) | 28 (32.9) | 6 (46.2) | 60 (60.6) | 0 (0) | 11 (61.1) | |||||||

| Tumour burden | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Solitary | 33 (47.1) | 93 (27.4) | 0.005 | 7 (87.5) | 5 (83.3) | 0.825 | 4 (66.7) | 12 (54.6) | 0.793 | 4 (66.7) | 12 (54.6) | 0.793 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.936 | 9 (52.9) | 31 (27.4) | 0.091 | 0 (0) | 2 (10.0) | 0.186 |

| 2–5 tumours | 10 (14.3) | 72 (21.2) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 9 (40.9) | 2 (33.3) | 9 (40.9) | 3 (25) | 24 (26.1) | 1 (5.9) | 18 (15.9) | 1 (100) | 4 (20.0) | |||||||

| >5 tumours | 27 (38.6) | 175 (51.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.6) | 9 (75) | 68 (73.9) | 7 (41.2) | 64 (56.6) | 0 (0) | 14 (70.0) | |||||||

| Largest tumour size | |||||||||||||||||||||

| <8 cm | 46 (67.7) | 185 (54.9) | 0.053 | 8 (100) | 6 (100) | NA | 6 (100) | 22 (100) | NA | 14 (56.0) | 35 (41.7) | 0.206 | 7 (58.3) | 54 (59.3) | 0.947 | 11 (68.8) | 59 (53.2) | 0.241 | 0 (0) | 6 (30.0) | 0.517 |

| ≥8 cm | 22 (32.4) | 152 (45.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 11 (44.0) | 49 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) | 37 (40.7) | 5 (31.3) | 52 (46.9) | 1 (100) | 14 (70.0) | |||||||

| Tumour location | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Unilobar | 52 (74.3) | 162 (47.7) | <0.001 | 7 (87.5) | 6 (100) | 0.369 | 13 (76.5) | 46 (40.7) | 0.006 | 1 (100) | 4 (20.0) | 0.619 | |||||||||

| Bilobar | 18 (25.7) | 178 (52.4) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 4 (23.5) | 67 (59.3) | 0 (0) | 16 (80.0) | |||||||||||||

| Portal vein invasion | |||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 52 (74.3) | 207 (60.4) | 0.083 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Branch | 15 (21.4) | 107 (31.2) | 14 (82.4) | 92 (79.3) | 0.771 | 1 (100) | 15 (75.0) | 0.567 | |||||||||||||

| Main and beyond | 3 (4.3) | 29 (8.5) | 3 (17.7) | 24 (20.7) | 0 (0) | 5 (25.0) | |||||||||||||||

| Y-90 administered dose, GBq | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.3 (0.84) | 1.7 (1.0) | 0.002 | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.3 (0.8) | 0.282 | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.4) | 0.019 | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.1) | 0.320 | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.7 (1.0) | 0.267 | 1.1 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.9) | 0.011 | 3 | 2.0 (1.1) | 0.233 |

| Median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.7–1.8) | 1.4 (1–2.4) | 0.003 | 1.0 (0.7–1.9) | 1.4 (1–2.4) | 0.219 | 0.6 (0.4 = 0.6) | 1.0 (0.6–1.1) | 0.011 | 1.5 (0.9–2.2) | 1.6 (1.1–2.6) | 0.311 | 1.3 (1.0–1.9) | 1.4 (1–2.3) | 0.348 | 0.8 (0.7–1.5) | 1.5 (1–2.5) | 0.005 | 3 | 1.8 (1.0–2.8) | |

| Tumour absorbed dose, Gy | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 190.3 (104.5) | 145.7 (70.6) | 0.001 | 234.3 (41.8) | 172.8 (46.1) | 0.433 | 196.6 (03.4) | 195.2 (74.3) | 0.972 | 203.4 (124.6) | 139.8 (63.8) | 0.003 | 166.7 (91.9) | 161.9 (71.8) | 0.847 | 164.6 (69.6) | 130.3 (64.0) | 0.090 | 90.1 | 108.2 (53.7) | |

| Median (IQR) | 166.4 (120–239.3) | 127.8 (94.8–182) | 0.002 | 218.3 (134.5–310.3) | 129.7 (123.8–265) | 0.540 | 157.4 (142.8–207.8) | 166.7 (143.0–265.6) | 0.889 | 190.5 (120.2–269.1) | 129.7 (100.8–179.0) | 0.001 | 166.4 (106–218.7) | 140 (110–211.7) | 0.891 | 181.6 (10.6–16.7) | 10.1 (91–155.9) | 0.104 | 90.1 | 107.9 (72.6–120.8) | |

| Subsequent curative treatment | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal ablation | 42 (60.0) | 7 (87.5) | 4 (66.7) | 10 (38.5) | 9 (75) | 11 (64.7) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||||

| Resection | 25 (35.7) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (33.3) | 16 (61.5) | 3 (25) | 3 (17.7) | 0 (0) | ||||||||||||||

| Transplant | 3 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (17.7) | 0 (0) | ||||||||||||||

| BCLC | |||||||||||||||||||||

| A | 24 (34.3) | 5 (15.2) | 0.001 | ||||||||||||||||||

| B | 27 (38.6) | 134 (39.1) | |||||||||||||||||||

| C | 19 (27.1) | 154 (44.9) | |||||||||||||||||||

| D | 0 (0) | 3 (0.9) | |||||||||||||||||||

| UT7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In | 14 (20.0) | 31 (9.0) | 0.007 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Out | 56 (80.0) | 312 (91.0) | |||||||||||||||||||

RE, radioembolisation; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; AFP, α-fetoprotein; NA, non-applicable; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver cancer; UT7, up-to-seven.

Subgroups: <Milan, within Milan Criteria; <UT7-u, unilobar HCC beyond Milan Criteria but within Up-to-seven Criteria (UT7); <UT7-b, bilobar HCC beyond Milan Criteria but within UT7; >UT7-u, unilobar HCC beyond Milan Criteria and UT7; >UT7-b, bilobar HCC beyond Milan Criteria and UT7; PVI-CPA, portal vein invasion (PVI) and Child-Pugh class A; PVI-CPB, with PVI and Child-Pugh class B.

1Bilobar HCCs beyond Milan and within UT7 criteria were excluded in this table due to low number of patients (n = 3).

Of all patients in our cohort, we evaluated incidences of REILD and RP post RE. A total of 21 (5.08%) developed REILD post-Y-90 RE based on the definition described in the Methods, and 2/3 of which had BCLC C HCC with portal vein invasion prior to treatment [34]. The mean and median non-tumorous liver dose in patients with REILD are 36.3 Gy ± 14.5 Gy and 39 Gy (range, 27.8–48.0 Gy), respectively. Thirteen patients (3.2%) developed respiratory symptoms and/or radiological pulmonary infiltrates, for which the possibility of RP could not be excluded. Only 1 patient required steroid treatment for RP (grade 2 toxicity), while the rest had grade 0 to grade 1 pneumonitis based on the modified National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria. The baseline characteristics and OS of patients who developed REILD and RP are summarised in online supplementary Table 5.

Discussion

RE with Y-90 has been widely used for the treatment of a broad spectrum of HCC. There is substantial evidence of the safety and efficacy of Y-90 RE when used with different therapeutic aims from supportive palliation therapy, downstaging and bridging therapy, to monotherapy with curative intent [11, 12, 21, 37]. Except for clinical outcomes data for surgical resection and TACE, there is an absence of granular data on the impact of tumour burden and distribution on clinical outcomes of intermediate to locally advanced HCC treated by different modalities [31, 38, 39]. Such data are essential to compare the clinical outcomes of patients with similar tumour burden treated with different modalities within this highly heterogeneous group of patients. While such comparisons do not have the strength of evidence provided by randomised controlled trials, they provide important information for clinical decision-making and are hypothesis-generating.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest single-institution HCC cohort treated with Y-90 resin microsphere RE with prospectively collected granular data. All patients were treated at a high-volume centre with consistency in the delivery of resin microsphere paired with long-term outcome data. Our result confirmed the efficacy of Y-90 RE with HCC, especially for patients with intermediate and locally advanced HCC (BCLC B-C). The median OS of our entire cohort of 413 patients was 20.9 months, one of the best outcomes reported from real-world studies of HCC treated with Y-90 RE [12, 37, 40, 41]. The OS of patients with locally advanced HCC (BCLC with PVI) in our cohort is much higher (mOS 12.3 months) than that reported in the two prospective multicentre trials with Y-90 RE, SIRveNIB and SARAH, where the OS were 8.8 and 8.0 months, respectively [14, 16]. This difference may be due to patient selection and a better understanding of the optimal dosing of Y-90 in recent years.

In line with previous studies, risk factors for worse outcomes after Y-90 RE included poor performance status (ECOG >1), suboptimal liver function (Child-Pugh B and ALBI 2–3), larger tumour, >5 tumour nodules, and higher AFP levels [12, 37]. This is largely in agreement with the BCLC stratification strategy and supports the proposal to consider AFP levels to further stratify HCC patients [6]. Moreover, our data show that it is prudent to include tumour distribution as a prognostication factor for HCC patients, as demonstrated by the significant disparities in OS and PFS between unilobar and bilobar HCC in our cohort. In patients with unilobar HCC, survivals were comparable between multifocal (<5 lesions) and solitary lesions, suggesting good efficacy of Y-90 RE beyond the currently FDA-approved indication for solitary HCC. The significantly improved OS in patients with HCC downstaged by Y-90 RE who subsequently received curative treatments suggests the potential of using Y-90 RE as a neoadjuvant modality in the treatment of high-risk HCC with curative intent.

Although the AASLD and EASL guidelines only recommended Y-90 RE as an alternative therapy to TACE, there’s a growing body of evidence that Y-90 RE has superior clinical outcomes and safety profile than TACE [12, 13, 41–44]. A small phase II randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing these two modalities in 45 BCLC A or B patients showed that patients in the Y-90 RE group had similar OS (18.6 vs. 17.7 months, p = 0.99) but significantly longer time to progression (TTP) (>26 vs. 6.8 months, p = 0.0012) compared to conventional TACE [13]. A phase II RCT (TRACE) comparing the efficacy of Y-90 RE and drug-eluting bead TACE in intermediate-stage HCC showed superior survival and tumour control in the Y-90 RE group at interim analysis, thereby meeting the primary endpoint of the study [44]. Similarly, an overall and individual patient-level meta-analysis included 17 studies comparing TACE and Y-90 RE showed significantly longer TTP after Y-90 RE [45]. BCLC B (intermediate) HCC encompasses a heterogeneous group of patients with different degrees of liver impairment and tumour burden, for which locoregional therapy is the standard of care. In our cohort, we observed a median OS of 24.2 months in BCLC B patients treated with Y-90 RE (n = 161, 95% CI: 20.4–31.1 months). Similar survival was reported in a retrospective study comparing Y-90 RE and TACE in BCLC B patients, when there is a trend towards a longer OS in the Y-90 RE group (21.53 ± 1.6 months) compared to TACE (17.06 ± 1.5 months) [46]. The incidence of REILD in our cohort was 5.08% (21 out of 413) based on the definition proposed by Braat et al. [34], which was consistent with that reported in the literature. This definition extended the onset of REILD from within 8 weeks of RE, as per Sangro Bruno’s original definition, to 4 months post-treatment [34, 47]. When we evaluated REILD based on the original definition, the incidence was 2.42% (10 out of 413). Mortality rates were 76.2% (extended definition) versus 90% (original definition) respectively, whereas OS did not differ significantly between the two definitions (HR 1.89, 95% CI: 0.75–4.79; p = 0.179).

As TACE is a relative contraindication in patients with HCC and PVI due to the risk of severe ischemia with pre-existing occlusion of the liver’s primary blood supply, Y-90 RE has been suggested as the preferred locoregional treatment of HCC with PVI. In our cohort, patients with PVI (including main PVI) had a median OS of 12.3 months, with no significant differences observed between branch and main portal vein invasions (Fig. 2e; Table 2). Patients with underlying Child-Pugh A disease and PVI had a median OS of 14.8 months, consistent with other cohorts [15, 37]. Until recently, tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) has been the recommended treatment by BCLC for HCC with PVI. In the subgroup analysis of the Sorafenib Asia-Pacific Trial, patients with PVI who received sorafenib had a modest survival benefit compared to placebo (5.6 vs. 4.1 months) [48]. Two earlier RCTs comparing Y-90 RE and sorafenib (SARAH and SIRveNIB) in advanced HCC showed no significant differences of OS in the subgroup of patients with PVI [14, 16]. However, since then the practice of Y-90 has changed significantly owing to improved dosimetry planning. A prospective observational study reviewed 75 BCLC C patients treated with Y-90 RE from 2015 to 2019 showed an OS of 13.6 months for the entire cohort (95% CI: 7.5–16.1). Consistent with our findings, patients with underlying Child’s A liver cirrhosis is the best predictor of longer OS [49]. A recently published multicentre retrospective study compared outcomes between Y-90 RE and TKI in 216 treatment-naïve HCC patients with segmental or lobar PVI (without main PVI) observed a superior OS in the Y-90 RE group versus TKI group after propensity score matching (24.2 vs. 8.4 months, p = 0.004) [50]. In the updated analysis of the IMBrave150 trial, patients with macrovascular invasion without extra-hepatic metastasis had OS of 14.1 months in the atezolizumab-bevacizumab group versus 9.7 months in the sorafenib group, whereas in real-world practice (AB-real study) the observed mOS were 10.03 months (8.8 months – NE) after a median follow-up of 10 months [51, 52]. Overall, the current data suggested a potential role of Y-90 RE in treating HCC with PVI with a trend towards a better outcome compared to sorafenib. Further studies are needed to compare the outcome of Y-90 RE with current first-line systemic therapy atezolizumab-bevacizumab in patients with PVI.

There have been major advances in the knowledge of Y-90 RE over the past decade. In particular, the use of personalised dosimetry with increasing tumour-absorbed dose thresholds has been shown to have better clinical outcomes. The recent TARGET study was a retrospective multicentre investigation that evaluated 209 patients with HCC who were treated with Y-90 glass microspheres [53]. The responders and non-responders had geometric mean total perfused tumour absorbed doses of 225.5 Gy and 188.3 Gy (p = 0.048) and higher tumour absorbed dose was associated with longer OS (HR per 100 Gy increase = 0.83, 95% CI: 0.71–0.95; p = 0.009). A randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 2 trial (DOSISPHERE-01) by Garin et al. [26] evaluated treatment with Y-90 glass microspheres and found that personalised dosimetry with a target of ≥205 Gy to tumour (PDA) performed favourably compared to a standard dosimetry group with 120 ± 20 Gy to the perfused liver territory (SDA) (20/28 vs. 10/28 had objective response, p = 0.0074). The updated analysis of this trial showed an OS gain of 12.1 months (PDA 24.8 months vs. SDA 10.7 months) with personalised dosimetry approach [27]. Another study comparing absorbed perfused liver dose with pathological necrosis of HCC in liver explants found that all patients receiving ≥400 Gy achieved complete pathological necrosis, thereby setting a standard for radiation segmentectomy using glass microspheres [54]. With regard to dosimetry for Y-90 resin microspheres, Hermann et al. [25] analysed the dosimetry of the phase 3 SARAH trial and found that out of the 121 patients with HCC treated, participants who received ≥100 Gy had a longer survival than those receiving less than 100 Gy (14.1 months [95% CI: 9.6 months, 18.6 months] vs. 6.1 months [95% CI: 4.9 months, 6.8 months], respectively; p < 0.001). The same study noted the highest disease control rate was observed in 31 of 40 participants (78%) with a tumour-absorbed dose ≥100 Gy and optimal visual agreement between the Tc-99m MAA study and Y-90 SPECT/CT or PET/CT. Recently, a single-arm clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of low-activity resin-based Y-90 RE in 30 HCC patients described a goal of delivering >200 Gy to the tumour and a non-tumoural liver dose of <70 Gy [55]. This study found that a mean tumour absorbed dose of 253 Gy predicted an overall tumoural response with 92% sensitivity and 83% specificity (AUC = 0.929). A more recent retrospective study by Villalobos et al. [56] compared the effectiveness and dosimetry between glass- versus resin-based Y-90 RE for HCC radiation segmentectomy. Both cohort had similar objective response rates (resin-based 95% vs. glass-based 82%, p = 0.1), but resin-based ablative Y-90 RE resulted in significantly higher complete response rate than the glass-based cohort (95% vs. 56%, p = 0.003). The tumour doses that predicted objective response and complete response in the resin-based cohort were 176 Gy and 247 Gy. This study also highlighted the different radiobiologies of glass- and resin microspheres, where higher tumour particle loading, lower tumour-to-normal ratio, and lower mean tumour dose was observed in the resin-based cohort. This likely accounted for the different dose targets reported in glass- versus resin-based Y-90 RE. Data on the dose-response relationship of resin-based Y-90 RE are emerging. Further studies are needed to evaluate the dose correlation with OS and PFS outcomes in addition to tumoural response, to better inform the optimal tumour dose of Y-90 resin microsphere RE.

One major advantage of our study is the availability of tumour-absorbed doses with the use of the partition model for dosimetry in 71.7% of the patients. For HCC without PVI, a tumour dose ≥150 Gy is an independent predictor of better OS. Baseline characteristics between subgroups who received tumour-absorbed dose <150 Gy and ≥150 Gy was summarised in online supplementary Table 4. The underlying assumption that the distribution of MAA and Y-90 resin microspheres was similar was corroborated by the post-treatment Y-90 PET/CT voxel-based dosimetry analysis whereby tumour absorbed dose above 150 Gy was confirmed in a subset of patients with available tumour absorbed dose from Y-90 PET-CT.

A limitation of the study is the possibility of bias in a retrospective cohort, where important confounding factors may not have been accounted for. The heterogeneous patient groups in our cohort, however, reflect the real-world HCC population that requires Y-90 RE. Information that was missing in our cohort included data on how many patients received additional therapies subsequently for tumour control, which could account for the relatively high OS albeit similar PFS compared to other cohorts. Tumour responses for RECIST and mRECIST assessment were also not available. Not all the patients in our cohort have tumour dose reported, which rendered dose-response analysis limited by the sample size.

Conclusion

Our single-institution experience with resin microsphere Y-90 RE showed good clinical outcomes in patients with intermediate to locally advanced HCC. Incorporating tumour burden, distribution, and tumour absorbed dose improved prognostication of intermediate HCC. Patients who received tumour dose above 150 Gy had significantly improved clinical outcomes. Patients who received curative-intent therapy after downstaging with Y-90 RE had remarkably better OS.

Statement of Ethics

The data used in this study constitutes de-identified patient information from our institution. The study protocol was reviewed by the Central Institutional Review Board (CIRB), and a waiver of informed consent was granted because the study did not meet the definition of Human Subject Research (CIRB Reg: 2023/2062).

Conflict of Interest Statement

David CE Ng received research funding from SIRTEX Medical, Bayer, Merck, Norvatis and Genzyme. Apoorva Gogna received honoraria as speaker/proctor from SIRTEX Medical. Chow Wei Too received honoraria as a proctor from SIRTEX Medical. Pierce KH Chow received honoraria from La Hoffman-Roche, SIRTEX Medical; research funding from Sirtex Medical, Ipsen, IQVIA, New B Innovation, AMiLi, Perspectum, MiRXES, La Hoffman-Roche; holds a consultancy or advisory role in Sirtex Medical, Ipsen, BMS, Oncosil, Bayer, New B Innovation, MSD, Guerbet, Roche, AUM Bioscience, L.E.K. Consulting, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Genentech, IQVIA, Abbott. The remaining authors have no conflicts to declare.

Funding Sources

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

Author Contributions

K.C., A.K.T.T., D.C.E.N., A.G., and P.K.H.C. conceptualised the study; K.C., A.K.T.T., F.N.N.M., R.H.G.L., S.P.T., K.S.H.L., N.K.V., H.L.H., C.W.T., E.X.Y., T.S.K.O., D.Y.Y.P., L.Y., W.Y.N., W.Y.C., J.P.E.C., B.K.P.G., and H.C.T. contributed to data acquisition; K.C., A.K.T.T., and L.Y. performed the data analysis and K.C., A.K.T.T., D.C.E.N., A.G., S.X.Y., and P.K.H.C. interpreted the results. K.C. and A.K.T.T. drafted the work and D.C.E.N., A.G., and P.K.H.C. reviewed it critically for important intellectual content. P.K.H.C. granted the final approval of the manuscript to be published.

Funding Statement

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants but are available from K.C. and corresponding author P.K.H.C. upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rumgay H, Arnold M, Ferlay J, Lesi O, Cabasag CJ, Vignat J, et al. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J Hepatol. 2022;77(6):1598–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang CH, Cheng Y, Zhang S, Fan J, Gao Q. Changing epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia. Liver Int. 2022;42(9):2029–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hassanipour S, Vali M, Gaffari-Fam S, Nikbakht HA, Abdzadeh E, Joukar F, et al. The survival rate of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asian countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EXCLI J. 2020;19:108–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chew XH, Sultana R, Mathew EN, Ng DCE, Lo RHG, Toh HC, et al. Real-world data on clinical outcomes of patients with liver cancer: a prospective validation of the national cancer centre Singapore consensus guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2021;10(3):224–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, Ferrer-Fabrega J, Burrel M, Garcia-Criado A, et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: the 2022 update. J Hepatol. 2022;76(3):681–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1301–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Galle PR, Forner A, Llovet JM, Mazzaferro V, Piscaglia F, Raoul J-L, et al. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):182–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, Sirlin CB, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):358–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kudo M. Heterogeneity and subclassification of Barcelona clinic liver cancer stage B. Liver Cancer. 2016;5(2):91–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Salem R, Johnson GE, Kim E, Riaz A, Bishay V, Boucher E, et al. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for the treatment of solitary, unresectable HCC: the LEGACY study. Hepatology. 2021;74(5):2342–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sangro B, Carpanese L, Cianni R, Golfieri R, Gasparini D, Ezziddin S, et al. Survival after yttrium-90 resin microsphere radioembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma across Barcelona clinic liver cancer stages: a European evaluation. Hepatology. 2011;54(3):868–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salem R, Gordon AC, Mouli S, Hickey R, Kallini J, Gabr A, et al. Y90 radioembolization significantly prolongs time to progression compared with chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(6):1155–63.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chow PKH, Gandhi M, Tan SB, Khin MW, Khasbazar A, Ong J, et al. SIRveNIB: selective internal radiation therapy versus sorafenib in asia-pacific patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(19):1913–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abouchaleh N, Gabr A, Ali R, Al Asadi A, Mora RA, Kallini JR, et al. (90)Y radioembolization for locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis: long-term outcomes in a 185-patient cohort. J Nucl Med. 2018;59(7):1042–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vilgrain V, Pereira H, Assenat E, Guiu B, Ilonca AD, Pageaux GP, et al. Efficacy and safety of selective internal radiotherapy with yttrium-90 resin microspheres compared with sorafenib in locally advanced and inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma (SARAH): an open-label randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(12):1624–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kennedy AS, Nutting C, Coldwell D, Gaiser J, Drachenberg C. Pathologic response and microdosimetry of (90)Y microspheres in man: review of four explanted whole livers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60(5):1552–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rodriguez LS, Thang SP, Li H, Khor LK, Tay YS, Myint KO, et al. A descriptive analysis of remnant activity during (90)Y resin microspheres radioembolization of hepatic tumors: technical factors and dosimetric implications. Ann Nucl Med. 2016;30(3):255–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Van Der Gucht A, Jreige M, Denys A, Blanc-Durand P, Boubaker A, Pomoni A, et al. Resin versus glass microspheres for (90)Y transarterial radioembolization: comparing survival in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma using pretreatment partition model dosimetry. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(8):1334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zori AG, Ismael MN, Limaye AR, Firpi R, Morelli G, Soldevila-Pico C, et al. Locoregional therapy protocols with and without radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma as bridge to liver transplantation. Am J Clin Oncol. 2020;43(5):325–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gabr A, Kulik L, Mouli S, Riaz A, Ali R, Desai K, et al. Liver transplantation following yttrium-90 radioembolization: 15-year experience in 207-patient cohort. Hepatology. 2021;73(3):998–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yu CY, Huang PH, Tsang LL, Hsu HW, Lim WX, Weng CC, et al. Yttrium-90 radioembolization as the major treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2023;10:17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pardo F, Sangro B, Lee RC, Manas D, Jeyarajah R, Donckier V, et al. The post-SIR-spheres surgery study (P4S): retrospective analysis of safety following hepatic resection or transplantation in patients previously treated with selective internal radiation therapy with yttrium-90 resin microspheres. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(9):2465–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu DM, Leung TW, Chow PK, Ng DC, Lee RC, Kim YH, et al. Clinical consensus statement: selective internal radiation therapy with yttrium 90 resin microspheres for hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia. Int J Surg. 2022;102:106094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hermann AL, Dieudonne A, Ronot M, Sanchez M, Pereira H, Chatellier G, et al. Relationship of tumor radiation-absorbed dose to survival and response in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial radioembolization with (90)Y in the SARAH study. Radiology. 2020;296(3):673–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garin E, Tselikas L, Guiu B, Chalaye J, Edeline J, de Baere T, et al. Personalised versus standard dosimetry approach of selective internal radiation therapy in patients with locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (DOSISPHERE-01): a randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(1):17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Garin E, Tselikas L, Guiu B, Chalaye J, Rolland Y, de Baere T, et al. Long-term overall survival after selective internal radiation therapy for locally advanced hepatocellular carcinomas: updated analysis of DOSISPHERE-01 trial. J Nucl Med. 2024;65(2):264–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68(2):723–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lau WY, Kennedy AS, Kim YH, Lai HK, Lee RC, Leung TW, et al. Patient selection and activity planning guide for selective internal radiotherapy with yttrium-90 resin microspheres. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(1):401–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sangro B, Martinez-Urbistondo D, Bester L, Bilbao JI, Coldwell DM, Flamen P, et al. Prevention and treatment of complications of selective internal radiation therapy: expert guidance and systematic review. Hepatology. 2017;66(3):969–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wee IJY, Moe FNN, Sultana R, Ang RWT, Quek PPS, Goh BKP, et al. Extending surgical resection for hepatocellular carcinoma beyond Barcelona Clinic for Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage A: a novel application of the modified BCLC staging system. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2022;9:839–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(11):693–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM, Miceli R, Bhoori S, Schiavo M, Mariani L, et al. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(1):35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Braat MN, van Erpecum KJ, Zonnenberg BA, van den Bosch MA, Lam MG. Radioembolization-induced liver disease: a systematic review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(2):144–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leung TW, Lau WY, Ho SK, Ward SC, Chow JH, Chan MS, et al. Radiation pneumonitis after selective internal radiation treatment with intraarterial 90yttrium-microspheres for inoperable hepatic tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;33(4):919–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lin M. Radiation pneumonitis caused by yttrium-90 microspheres: radiologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162(6):1300–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kolligs F, Arnold D, Golfieri R, Pech M, Peynircioglu B, Pfammatter T, et al. Factors impacting survival after transarterial radioembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: results from the prospective CIRT study. JHEP Rep. 2023;5(2):100633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang Q, Xia D, Bai W, Wang E, Sun J, Huang M, et al. Development of a prognostic score for recommended TACE candidates with hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicentre observational study. J Hepatol. 2019;70(5):893–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hung YW, Lee IC, Chi CT, Lee RC, Liu CA, Chiu NC, et al. Redefining tumor burden in patients with intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: the seven-eleven criteria. Liver Cancer. 2021;10(6):629–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hilgard P, Hamami M, Fouly AE, Scherag A, Muller S, Ertle J, et al. Radioembolization with yttrium-90 glass microspheres in hepatocellular carcinoma: European experience on safety and long-term survival. Hepatology. 2010;52(5):1741–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Kulik L, Wang E, Riaz A, Ryu RK, et al. Radioembolization results in longer time-to-progression and reduced toxicity compared with chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(2):497–507 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang Y, Li Y, Ji H, Zhao X, Lu H. Transarterial Y90 radioembolization versus chemoembolization for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Biosci Trends. 2015;9(5):289–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yang Y, Si T. Yttrium-90 transarterial radioembolization versus conventional transarterial chemoembolization for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Biol Med. 2018;15(3):299–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dhondt E, Lambert B, Hermie L, Huyck L, Vanlangenhove P, Geerts A, et al. (90)Y radioembolization versus drug-eluting bead chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: results from the TRACE phase II randomized controlled trial. Radiology. 2022;303(3):699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Brown AM, Kassab I, Massani M, Townsend W, Singal AG, Soydal C, et al. TACE versus TARE for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: overall and individual patient level meta analysis. Cancer Med. 2023;12(3):2590–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Massani M, Pirozzolo G, Stecca T, Barbisan D, Pozza FD, Morana G, et al. Yttrium-90 radioembolisation versus transarterial chemoembolisation for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective comparative analysis according to BCLC classification. Clin Surg. 2017;2. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sangro B, Gil-Alzugaray B, Rodriguez J, Sola I, Martinez-Cuesta A, Viudez A, et al. Liver disease induced by radioembolization of liver tumors: description and possible risk factors. Cancer. 2008;112(7):1538–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cheng AL, Guan Z, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma according to baseline status: subset analyses of the phase III Sorafenib Asia-Pacific trial. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(10):1452–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Goswami P, Adeniran OR, K Frantz S, Matsuoka L, Du L, Gandhi RT, et al. Overall survival and toxicity of Y90 radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma patients in Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C (BCLC-C). BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22(1):467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hur MH, Cho Y, Kim DY, Lee JS, Kim GM, Kim HC, et al. Transarterial radioembolization versus tyrosine kinase inhibitor in hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29(3):763–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cheng AL, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2022;76(4):862–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fulgenzi CAM, Cheon J, D'Alessio A, Nishida N, Ang C, Marron TU, et al. Reproducible safety and efficacy of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab for HCC in clinical practice: results of the AB-real study. Eur J Cancer. 2022;175:204–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lam M, Garin E, Maccauro M, Kappadath SC, Sze DY, Turkmen C, et al. A global evaluation of advanced dosimetry in transarterial radioembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma with Yttrium-90: the TARGET study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;49(10):3340–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gabr A, Riaz A, Johnson GE, Kim E, Padia S, Lewandowski RJ, et al. Correlation of Y90-absorbed radiation dose to pathological necrosis in hepatocellular carcinoma: confirmatory multicenter analysis in 45 explants. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48(2):580–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kokabi N, Arndt-Webster L, Chen B, Brandon D, Sethi I, Davarpanahfakhr A, et al. Voxel-based dosimetry predicting treatment response and related toxicity in HCC patients treated with resin-based Y90 radioembolization: a prospective, single-arm study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;50(6):1743–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Villalobos A, Arndt L, Cheng B, Dabbous H, Loya M, Majdalany B, et al. Yttrium-90 radiation segmentectomy of hepatocellular carcinoma: a comparative study of the effectiveness, safety, and dosimetry of glass-based versus resin-based microspheres. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2023;34(7):1226–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement