Abstract

The present study evaluated the potential use of immunoglobulin prepared from the egg yolk of hens immunized with Helicobacter pylori (immunoglobulin Y [IgY]-Hp) in the treatment of H. pylori infections. The purity of our purified IgY-Hp was 91.3%, with a yield of 9.4 mg of IgY per ml of egg yolk. The titer for IgY-Hp was 16 times higher than that for IgY in egg yolk from nonimmunized hens, and IgY-Hp significantly inhibited the growth and urease activity of H. pylori in vitro. Bacterial adhesion on AGS cells was definitely reduced by preincubation of both H. pylori (108 CFU/ml) and 10 mg of IgY-Hp/ml. In Mongolian gerbil models, IgY-Hp decreased H. pylori-induced gastric mucosal injury as determined by the degree of lymphocyte and neutrophil infiltration. Therefore, in this experimental model, H. pylori-associated gastritis could be successfully treated by orally administered IgY-Hp. The immunological activity of IgY-Hp stayed active at 60°C for 10 min, suggesting that pasteurization can be applied to sterilize the product. Fortification of food products with this immunoglobulin would significantly decrease the H. pylori infection. In conclusion, the IgY-Hp obtained from hens immunized by H. pylori could provide a novel alternative approach to treatment of H. pylori infection.

Helicobacter pylori is the most common cause of gastritis and gastric ulcers and plays a pivotal role in the development of gastric carcinomas (3, 21). Often a significant portion of those infected do not show symptoms, although chronic infection increases the risk of the development of H. pylori-associated gastric disease. There have been tremendous efforts to evaluate numerous therapeutic regimens for eradication of H. pylori infections. Successful treatment of H. pylori infections most often employs antibiotic therapy, consisting of some combination of metronidazole, amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and either bismuth or a proton pump inhibitor (8, 12). However, antibiotic therapy fails in 10 to 15% of cases due to the development of antibiotic resistance (5, 22). Increasing occurrence of antibiotic resistance would further complicate the treatment of H. pylori infections. Consequently, it is important to seek new therapies for a wider means of treating, suppressing, or preventing H. pylori infection without drug resistance problems.

The concept of protecting a host with passively derived antibodies is not new. It has been shown that oral administration of antibacterial or antiviral immunoglobulins, through infant formulae or other diet, is effective in preventing intestinal infection (4, 23). However, oral administration of antibodies is prohibitively expensive when large amounts of antibodies are required (14).

Recently, chicken egg yolk was recognized as an inexpensive, alternative antibody source, and the usefulness of egg yolk immunoglobulin Y (IgY) has been assessed for therapeutic application by passive immunization therapy through oral ingestion of IgY, as in fortified food products for prevention or control of intestinal infections, such as those caused by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (20), Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (25), and rotavirus (9, 17, 23). These studies, taken together, provide the potential advantage of using IgY with specificity to H. pylori (IgY-Hp) for controlling H. pylori-associated gastric disease and subsequently prevent disease resulting from chronic infection. Nevertheless, there has been no report so far on the use of IgY in the prevention and treatment of H. pylori infections.

Furthermore, for the practical application of IgY-Hp, together with food or pharmaceutical materials to prevent H. pylori-associated disease, the stability of IgY toward heat, acid, and pepsin should be ensured. The aim of this study was to evaluate the potential use of IgY-Hp in the prevention and treatment of H. pylori infections. To achieve this objective, we studied, in vitro and in vivo, the activity of IgY-Hp against H. pylori. The effect of IgY-Hp on gastric mucosal injury induced by H. pylori was evaluated in vivo using Mongolian gerbils. The stability of IgY-Hp was also investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

H. pylori preparation and immunization.

H. pylori (ATCC 43504) was cultured in brucella broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.), supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) bovine calf serum (PAA Laboratories Inc., Parker Ford, Pa.) and antibiotics (amphotericin B, 2.5 μg/ml; vancomycin, 10 μg/ml; trimethoprim, 5 μg/ml; and polymyxin B, 2.5 IU/ml; all were from Sigma Chemical Co. [St. Louis, Mo.]) at 37°C under 10% CO2 at 200 rpm. The H. pylori was harvested by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min and disrupted by sonication. Cellular material was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was collected (H. pylori whole-cell lysate). The protein concentrations were determined by bicinchoninic acid methods (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

Brown Leghorn hens (25 weeks old; n = 15) were immunized intramuscularly with H. pylori whole-cell lysate (200 μg/ml, protein) using an equal volume of Freund's complete adjuvant (Difco Laboratories). Each hen was injected at four different sites (250 μl per site) of the leg muscle. Three booster injections, with Freund's incomplete adjuvant, were given at 2-week intervals following the first injection. One month after immunization, the eggs laid were collected daily for 1 month and stored at 4°C. The egg yolk was separated, pooled, and frozen prior to purification of IgY.

Isolation and purification of IgY-Hp.

Isolation of IgY-Hp was carried out by the method described by Akita and Nakai (1) with modification. Egg yolk was separated from the white, and the yolk preparation was mixed with an equal volume of distilled water for 30 min, followed by the addition of 0.15% (wt/vol) λ-carrageenan (Wako Pure Chemical Laboratory, Osaka, Japan). After centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 20°C for 30 min, the water-soluble fraction (WSF) was collected and filtered through a Whatman filter paper (no. 1) to remove solid lipid materials. The resulting IgY-containing filtrate was further purified by salt precipitation (19% [wt/vol] sodium sulfate) and ultrafiltration (UF) using a UF membrane (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) cartridge with a molecular weight cutoff of 100 kDa. Purity and yield of IgY were monitored at various stages by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The IgY content was measured by its absorbance at 280 nm.

SDS-PAGE.

According to the method of Laemmli (18), 10% PAGE was done with a Mini-PROTEAN II Cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). Under nonreducing conditions, samples were diluted 1:4 with sample buffer (62.6 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 25% [vol/vol] glycerol, and 2% SDS [vol/vol]). Under reducing conditions, samples were diluted with sample buffer containing 5% (vol/vol) β-mercaptoethanol and heated for 5 min at 100°C. Fifteen microliters of the samples was loaded into each well (3 μg of protein per well). Prestained SDS-PAGE standards (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and standard chicken IgY (Promega, Madison, Wis.) were used as molecular weight markers.

ELISA.

To assess the antibody activity of IgY-Hp to H. pylori, we performed the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) by Akita et al. (2) with modification. Ninety-six-well plates were coated with H. pylori whole-cell lysate (500 ng/well). After blocking with 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin, 100 μl of IgY-Hp (1 mg/ml) was added using a twofold serial dilution. The plates were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-Tween (0.05% Tween 20 in PBS [pH 7.2]) and incubated for 1 h after the addition of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-chicken IgY (Promega). The plates were washed with PBS-Tween, and disodium p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma) was added as substrate to each well. After incubation for 10 min, the reaction was stopped by addition of 3 M NaOH. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm using a microplate reader (Multiskan MS; Thermo Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland).

Heat, acid, and pepsin stability of IgY-Hp.

IgY-Hp solutions were incubated at 0, 4, 10, 25, 35, 60, 70, 80, and 90°C for 10 min. The heat-treated IgY-Hp was cooled in an ice bath. For the pH stability test, the pHs of IgY-Hp solutions were adjusted to the desired pH (pH 2 to 8) with NaOH or HCl, the solutions were incubated at 37°C for 4 h, and then each IgY-Hp solution was neutralized. For the pepsin stability tests, the pHs of the IgY-Hp solutions were adjusted to pH 2, pH 4, and pH 6, respectively. IgY-Hp solution of each pH were incubated with 15 μg of pepsin (Sigma)/ml at 37°C for 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 h. After incubation, each IgY-Hp solution was neutralized to inactivate the pepsin. The remaining antibody activity was measured by ELISA, following the heat, pH, and pepsin treatments. Antibody activity was represented as a percentage of control.

Colony counting.

H. pylori (108 CFU/ml) was incubated with IgY-Hp (1 and 10 mg/ml) for 6 h at 37oC under 10% CO2 at 50 rpm. After incubation, H. pylori was diluted with brucella broth via a 10-fold series dilution. Each 100 μl was inoculated onto brucella agar containing 5% (vol/vol) bovine calf serum, and the plate contents were incubated at 37°C under 10% CO2 for 10 days. The colonies were identified as H. pylori by Gram staining and urease, oxidase, and catalase activities. The growth rate (percentage of control) was calculated by colony counting compared to results for the control.

Urease activities.

Both IgY-Hp (1 and 10 mg/ml) and H. pylori (108 CFU/ml) were incubated at 37°C under 10% CO2 for 6 h at 50 rpm, and then 50 μl of urea base (2% urea and 0.03% phenol red) was added and allowed to react for 30 min. Urease activity was quantified by measuring the optical density at 550 nm, using a modification to the method of Fauchere and Blaser (10), and was represented as % of control.

H. pylori adhesion on AGS cells.

The human gastric carcinoma cell line AGS was obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Korea). Cells (105 cells/ml) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.), supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, Utah) and antibiotics (100 U of penicillin/ml and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml; HyClone) at 37°C under 5% CO2 for 24 h. AGS cells were checked for their H. pylori colonization level in the presence or absence of IgY-Hp using scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

SEM.

For electron microscopy investigation of bacterial adhesion, 300 μl of preincubated IgY-Hp (10 mg/ml) and H. pylori (108 CFU/ml) was added to the AGS cells on the chamber slide (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, Ill.). After incubation for 4 h, the chamber slide was washed with PBS and fixed with 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde for 24 h. After washing with PBS, the material was postfixed with 1% OSO4 for 60 min and then washed twice with PBS. Fixed material was dehydrated through a graded ethanol series from 50 to 95%, followed by two washes with absolute ethanol for 15 min. Dehydrated material, in absolute ethanol, was critical point dried in a critical point drier (HCP-2; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Critical point dried material was mounted on an aluminum stub and coated with gold. Adherence of H. pylori to AGS cells was observed by SEM (S2500; Hitachi).

Passive immunization with IgY-Hp against H. pylori infection in Mongolian gerbils.

Mongolian gerbils (6-week-old males) were purchased from Bio Animal 21 (Sung-Nam, Korea). The gerbils were infected with H. pylori (0.5 ml, 108 CFU/ml, orally) three times at 12-h intervals. Two weeks after inoculation, immune response to infection was monitored by ELISA. H. pylori-infected gerbils were randomly divided into three groups as follows: (i) H. pylori infection only (n = 10), (ii) treatment with 1 mg of IgY-Hp treatment/ml (n = 10), and (iii) treatment with 10 mg of IgY-Hp/ml (n = 10). Negative control groups were administered IgY-Hp (1 and 10 mg/ml) alone (n = 10). IgY-Hp (1 ml) was administered daily, using an oral feeding needle, for 4 weeks. After the gerbils were fasted for 24 h, the antral portion of stomach was quickly removed and used for histological examinations. Formalin-fixed tissue was processed routinely in paraffin and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for examination by light microscopy. Gastric mucosal injury was classified and scored on a scale of 0, 1, 2, or 3, according to the updated Sydney system (6).

Statistical analysis.

All data were expressed as the means ± standard deviations (SD). The statistical significance was evaluated by Student's t tests. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Purification and characterization of IgY-Hp from egg yolk.

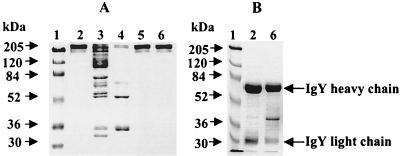

Isolation of egg yolk IgY, using the λ-carrageenan method followed by a UF system, was effective. The purity of the IgY obtained was 91.3%, with a yield of 9.4 mg of IgY per ml of egg yolk (Table 1). The egg yolk proteins obtained during purification of IgY were analyzed using SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig. 1, the IgY finally purified, using the UF system, was pure and dissociated into heavy and light chains of 64 and 25 kDa, respectively. The electrophoretic patterns were in perfect accordance with commercially available IgY (Promega) (Fig. 1A and B, lane 2). After treating the egg yolk with λ-carrageenan, the number of proteins in the WSF were significantly decreased. These contaminating proteins were removed by salting out with 19% sodium sulfate. The IgY preparation was concentrated and desalted using the UF system.

TABLE 1.

Summary of yield and purity of IgY from egg yolk

| Prepn | Amt of protein (mg) | Amt of IgY (mg) | Purity (%) | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egg yolk | 260a | 10.5 | 4.0 | 100 |

| WSFb | 32.9 | 9.9 | 30.1 | 94.3 |

| SOSc | 10.8 | 9.7 | 89.8 | 92.4 |

| UFd | 10.3 | 9.4 | 91.3 | 89.5 |

A 1-ml egg yolk was used.

WSF after 0.15% λ-carrageenan treatment.

SOS, Salting-out solution created by 19% sodium sulfate treatment.

Final preparation by UF (Materials and Methods).

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE patterns of IgY purified from egg yolk. (A) Coomassie-stained SDS-10% PAGE under nonreducing conditions. (B) Reducing conditions of SDS-10% PAGE. Lanes: 1, molecular size marker, 2, chicken IgY, standard immunoglobulin (Promega), 3, egg yolk, 4, WSF after λ-carrageenan treatment, 5, IgY obtained after salting out, and 6, final IgY obtained by UF.

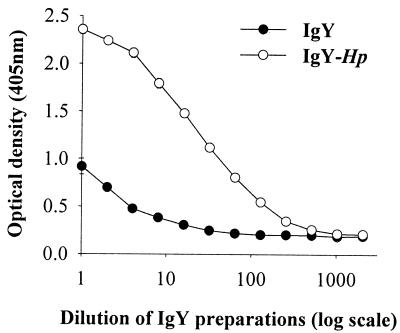

The IgY and IgY-Hp obtained from hens without and with H. pylori immunization, respectively, were examined for immunological properties by ELISA. The ELISA titers were 640 and 10,240 for IgY and IgY-Hp, respectively. These results indicate that IgY-Hp is highly specific to H. pylori (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

The reaction between IgY-Hp and H. pylori. One hundred microliters of IgY-Hp (1 mg/ml) was added with a twofold serial dilution in 96-well plates coated with H. pylori whole-cell lysate (500 ng/well), and the titers were measured using ELISA. IgY was isolated from the egg yolk of nonimmunized hens, and IgY-Hp was obtained from H. pylori-immunized hens.

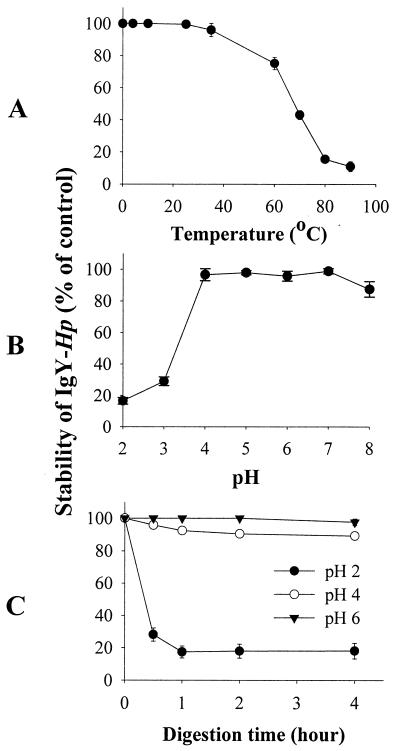

The heat, pH, and pepsin stabilities of IgY-Hp were evaluated by ELISA (Fig. 3). The IgY-Hp was stable at 40°C. However, at 60°C for 10 min, IgY-Hp lost approximately 20% of its antibody activity. The antibody activity of IgY-Hp significantly decreased at 80°C and lost up to 90% of its activity. IgY-Hp showed broad stability between the pHs 4 and 8. However, IgY-Hp lost 80 and 70% of its initial activity at pH 2 and 3, respectively. The antibody activity of IgY-Hp, as determined by ELISA, was almost lost when incubated with pepsin at pH 2, while about 92 and 99% of the activity remained at pH 4 and 6, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Heat, pH, and pepsin stability of IgY-Hp. IgY-Hp was treated at various temperatures for 10 min (A), at various pHs for 4 h (B), and with pepsin (15 μl/ml) (C) at pH 2, 4, and 6 for 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 h. Remaining activities after the treatments were measured using ELISA and are expressed as a percentage of the initial activity.

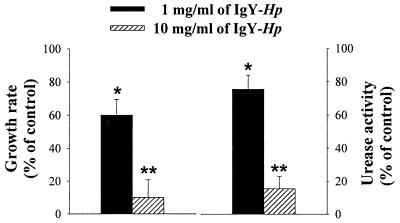

Effects of IgY-Hp on growth and urease activity of H. pylori in vitro.

To determine the effect of IgY-Hp on the growth and urease activity of H. pylori, we compared growth rates and urease activity with those of the control. The growth rates for H. pylori were 60.0% ± 9.5% and 10.0% ± 10.8% compared with those found for the control, after incubation with 1 mg and 10 mg of IgY-Hp/ml, respectively (Fig. 4). When H. pylori (108 CFU/ml) was incubated with IgY-Hp (1 and 10 mg/ml) for 6 h, the urease activity of H. pylori was 75.4% ± 8.5% and 15.5% ± 7.4% compared with that of the control (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Effect of IgY-Hp on the growth and urease activity of H. pylori. H. pylori (108 CFU/ml) was incubated with of IgY-Hp (1 and 10 mg/ml) for 6 h at 37°C under 10% CO2 at 50 rpm. After incubation, bacteria were inoculated on agar plates. The growth rate (percentage of control) was calculated by colony counting compared to the control. Both IgY-Hp (1 and 10 mg/ml) and H. pylori (108 CFU/ml) were incubated at 37oC under 10% CO2 for 6 h at 50 rpm and then 50 μl of urea base (2% urea-0.03% phenol red) was added and reacted for 30 min. Urease activity was measured by a spectrophotometer at 550 nm and is represented as a percentage of the control. The results are shown as the mean ± SD. * and **, statistically significant differences from the values for the control (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively).

Effect of IgY-Hp on H. pylori-induced gastritis in the Mongolian gerbils model.

Mongolian gerbils were inoculated with H. pylori. Two weeks after the inoculation, the status of infection was confirmed by measuring the serum antibody (IgG) against H. pylori. The H. pylori-infected gerbils were determined by high IgG titer (data not shown).

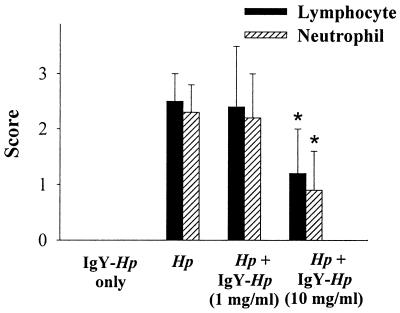

Oral administration of 10 mg of IgY-Hp/ml for 4 weeks to the H. pylori-infected gerbils improved lymphocyte infiltration compared to that found for the H. pylori infection group with no IgY-Hp (1.2 ± 0.8 versus 2.5 ± 0.5; P < 0.01) (Fig. 5). However, the group that was administered 1 mg of IgY-Hp/ml showed no statistically significant difference with the H. pylori infection group (2.4 ± 1.1 versus 2.5 ± 0.5) (Fig. 5). The group treated with 10 mg of IgY/ml significantly improved neutrophil infiltration (0.9 ± 0.7 versus 2.3 ± 0.8; P < 0.01) (Fig. 5). There was no statistically significant difference between the group treated with 1 mg of IgY-Hp/ml and the H. pylori infection group (2.2 ± 0.5 versus 2.3 ± 0.8) (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Effect of IgY-Hp on H. pylori-induced gastric mucosal injury. IgY-Hp (1 and 10 mg/ml) was orally administered to Mongolian gerbils for 4 weeks. The lymphocytes and neutrophils were measured by the degree of lymphocyte and neutrophil infiltration, respectively. The results are shown as the mean ± SD. *, statistically significant differences from the values for the H. pylori infection group (P < 0.01).

A high dose of IgY-Hp treatment decreased H. pylori-induced lymphocyte and neutrophil infiltration in gastric mucosa. However, a low dose of IgY failed to protect gerbils from H. pylori-induced gastric mucosal injury.

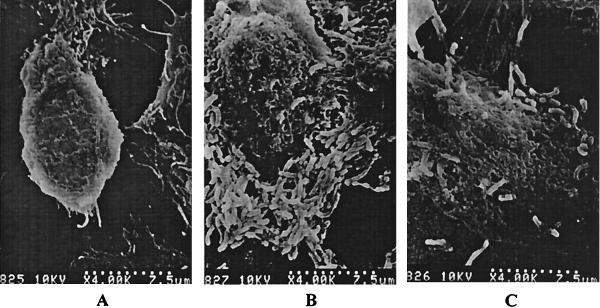

Effect of IgY-Hp on H. pylori attachment on AGS cells.

Figure 6 shows SEM of AGS cells and those infected with H. pylori (108 CFU/ml) in the presence and absence of IgY-Hp (10 mg/ml). Numerous rod-shaped H. pylori organisms, attached to the AGS cells' surfaces, were observed when cells were cultured with H. pylori (Fig. 6B). On the other hand, the number of adhering H. pylori organisms dramatically decreased when cells were pretreated with IgY-Hp (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

SEM findings for H. pylori-infected AGS cells in the presence or absence of IgY-Hp. (A) AGS cells. (B) AGS cells infected with H. pylori (108 CFU/ml). (C) AGS cells infected with H. pylori (108 CFU/ml) pretreated with IgY-Hp (10 mg/ml).

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that IgY-Hp prepared from the egg yolk of hens immunized with H. pylori is effective in the treatment of H. pylori infections. H. pylori infections are widespread in humans, and, although they can be cured using antimicrobial therapy, this large-scale use of antibiotics leads to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains (5, 22). Moreover, antimicrobial therapeutic cures of H. pylori infections do not lead to immunity from reinfection (28), and the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains can increase failure-of-therapy and relapse rates (26). Consequently, there have been tremendous efforts to seek alternatives to antibiotic-based therapies for a more widely available means of treating, suppressing, or preventing H. pylori infections without drug resistance problems.

Recent work in several laboratories, using several animal models, has shown that immunization with defined native and recombinant antigens of H. pylori can protect against H. pylori infections (7, 11, 16). The mechanisms of protection are still poorly understood. Although prophylactic and therapeutic immunization has been successful in animal models, efficacy data for humans are still lacking.

On the other hand, treatment of H. pylori infection by oral administration of active antibodies specific to H. pylori may have merit, due to the antibody being recognized by H. pylori, thus inhibiting adhesion of the bacterium to human epithelial cells more efficiently. Many studies have shown that egg yolk from an immunized hen has an antibody capable of specific recognition in an abundant quantity and is therefore economical (15, 19, 27). We estimated that 1 ml of the egg yolk (15 ml per egg) contains about 9.4 mg of IgY. A hen lays about 250 eggs (about 4,000 ml of egg yolk) in a year; thus, the eggs laid by an immunized hen in a year would yield 40 g of IgY. Oral administration of IgY from chicken egg yolk has been used successfully by many researchers in preventing many intestinal diseases, such as those caused by enterotoxigenic E. coli (20) and human rotavirus (9, 23). Sugita-Konishi et al. (24) reported that IgY, obtained from hens immunized with a mixture of formalin-treated pathogenic bacteria, inhibited the growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The production of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin A and adhesion of Salmonella typhimurium serovar Enteritidis to cultured human intestinal cells were also inhibited. IgY antibodies inhibited the colonization of teeth by Streptococcus mutans, thus preventing plaque formation in humans (13). However, there has been no report so far on the use of IgY in the prevention and treatment of H. pylori infections.

In this study, IgY-Hp, obtained from hens immunized with H. pylori whole-cell lysate, dramatically inhibited the growth of H. pylori in vitro. If the antibody IgY had no specific effect, no inhibition of bacterial growth would occur. It seems clear from our observations, using gerbil models, that IgY-Hp decreased H. pylori-induced gastric mucosal injury, as determined by the degree of lymphocyte and neutrophil infiltration. Therefore, the therapeutic value of orally administered IgY-Hp, against the experimental model in gerbils, lies in its ability to inhibit the bacterial organism. More convincing evidence in support of the specificity of these antibodies comes from inhibition of H. pylori attachment to AGS cells, as confirmed by SEM. Although the mechanisms by which IgY-Hp prevented H. pylori colonization are yet not elucidated, our results suggest that IgY-Hp would inhibit H. pylori adherence properties. Of interest, the IgY-Hp used in this study significantly inhibited urease activity. The relationship between inhibitions of urease activity and adhesion properties needs to be clarified. In this study, IgY-Hp seems to have two properties: inhibiting adhesion of the bacterium to gastric epithelial cells and demonstrating powerful urease-inhibiting activity.

For practical application of IgY-Hp together with food or pharmaceutical materials to treat H. pylori infection, the stability of IgY-Hp toward heat, acid, or pepsin was studied by measuring the remaining activity by ELISA. Immunologically, IgY-Hp stayed active at 60°C for 10 min, suggesting that pasteurization can be applied to sterilize the product. The fortification of food products with this immunoglobulin, together with its higher productivity and effectiveness, would significantly decrease the activities of H. pylori infections.

In conclusion, the encouraging results of this study indicate that the IgY-Hp obtained from hens immunized by H. pylori may provide a novel approach to the management of H. pylori infections in humans. However, many problems remain unsolved for the clinical application, such as the effect of IgY-Hp in humans, the persistence of the effect of IgY-Hp after cessation of the application, and the potential for eradicating an established infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant no. 2000-1-20800-005-3 from the Basic Research Program of the Korea Science & Engineering Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akita, E. M., and S. Nakai. 1993. Comparison of four purification methods for the production of immunoglobulin from eggs laid by hens immunized with an enterotoxigenic E. coli strain. J. Immunol. Methods 160:207-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akita, E. M., and S. Nakai. 1992. Immunoglobulin from egg yolk: isolation and purification. J. Food Sci. 57:629-634. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaser, M. J. 1992. Hypotheses on the pathogenesis and natural history of Helicobacter pylori induced inflammation. Gastroenterology 102:720-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlander, D., H. Kollberg, P. E. Wejaker, and A. Larsson. 2000. Peroral immunotherapy with yolk antibodies for the prevention and treatment of enteric infections. Immunol. Res. 21:1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deloney, C. R., and N. L. Schiller. 2000. Characterization of an in vitro-selected amoxicillin-resistant strain of Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3368-3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon, M. F., R. M. Genta, J. H. Yardley, and P. Correa. 1996. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney Syst. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 20:1161-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubois, A., C. K. Lee, N. Fiala, H. Kleanthous, P. T. Mehlman, and T. Monath. 1998. Immunization against natural Helicobacter pylori infection in nonhuman primates. Infect. Immun. 66:4340-4346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunn, B. E., H. Cohen, and M. J. Blaser. 1997. Helicobacter pylori. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:720-741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebina, T. 1996. Prophylaxis of rotavirus gastroenteritis using immunoglobulin. Arch. Virol. 12(Suppl.):217-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fauchere, J. L., and M. J. Blaser. 1990. Adherence of Helicobacter pylori cells and their surface components to HeLa cell membranes. Microb. Pathog. 9:427-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrero, R. L., J. M. Thiberge, I. Kansau, N. Wuscher, M. Huerre, and A. Labigne. 1995. The GroES homolog of Helicobacter pylori confers protective immunity against mucosal infection in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:6499-6503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibaldi, M. 1995. Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal disease. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 35:647-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatta, H., K. Tsuda, M. Ozeki, M. Kim, T. Yamamoto, S. Otake, M. Hirasawa, J. Katz, N. K. Childers, and S. M. Michalek. 1997. Passive immunization against dental plaque formation in humans: effect of a mouth rinse containing egg yolk antibodies (IgY) specific to Streptococcus mutans. Caries Res. 31:268-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatta, H., K. Tsuda, S. Akachi, M. Kim, T. Yamamoto, and T. Ebina. 1993. Oral passive immunization effect of anti-human rotavirus IgY and its behavior against proteolytic enzymes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 57:1077-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatta, H., K. Tsuda, S. Akachi, M. Kim, and T. Yamamoto. 1993. Productivity and some properties of egg yolk antibody (IgY) against human rotavirus compared with rabbit IgG. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 57:450-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koesling, J., B. Lucas, L. Develioglou, T. Aebischer, and T. F. Meyer. 2001. Vaccination of mice with live recombinant Salmonella typhimurium aroA against H. pylori: parameters associated with prophylactic and therapeutic vaccine efficacy. Vaccine 12:413-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuroki, M., M. Ohta, Y. Ikemori, F. C. Icatlo, Jr., C. Kobayashi, H. Yokoyama, and Y. Kodama. 1997. Field evaluation of chicken egg yolk immunoglobulins specific for bovine rotavirus in neonatal calves. Arch. Virol. 142:843-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, X., T. Nakano, H. H. Sunwoo, B. H. Paek, H. S. Chae, and J. S. Sim. 1998. Effects of egg and yolk weights on yolk antibody (IgY) production in laying chickens. Poult. Sci. 77:266-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marquardt, R. R., L. Z. Jin, J. W. Kim, L. Fang, A. A. Frohlich, and S. K. Baidoo. 1999. Passive protective effect of egg-yolk antibodies against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88+ infection in neonatal and early-weaned piglets. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 23:283-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsonnet, J., S. Hansen, L. Rodriguez, A. B. Gelb, R. A. Warnke, E. Jellum, J. H. Vogelman, and G. D. Friedman. 1994. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 330:1267-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peitz, U., M. Menegatti, D. Vaira, and P. Malfertheiner. 1998. The European meeting on Helicobacter pylori: therapeutic news from Lisbon. Gut 43(Suppl.):S66-S69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarker, S. A., T. H. Casswall, L. R. Juneja, E. Hoq, I. Hossain, G. J. Fuchs, and L. Hammarstrom. 2001. Randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of hyperimmunized chicken egg yolk immunoglobulin in children with rotavirus diarrhea. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 32:19-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugita-Konishi, Y., K. Shibata, S. S. Yun, Y. Hara-Kudo, K. Yamaguchi, and S. Kumagai. 1996. Immune functions of immunoglobulin Y isolated from egg yolk of hens immunized with various infectious bacteria. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 60:886-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sunwoo, H. H., T. Nakano, W. T. Dixon, and J. S. Sim. 1996. Immune responses in chickens against lipopolysaccharide of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Poult. Sci. 75:342-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trust, T. J., R. A. Alm, and J. Pappo. 2001. Helicobacter pylori: today's treatment, and possible future treatment. Eur. J. Surg. 586(Suppl.):82-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verdolva, A., G. Basile, and G. Fassina. 2000. Affinity purification of immunoglobulins from chicken egg yolk using a new synthetic ligand. J. Chromatogr. B 749:233-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xia, H. X., N. J. Talley, C. T. Keane, and C. A. O'Morain. 1997. Recurrence of Helicobacter pylori infection after successful eradication: nature and possible causes. Dig. Dis. Sci. 42:1821-1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]