Dallas, Texas, was founded in 1841 by John Neely Bryan on the east bank of the Trinity River (1). In 1842 he married Margaret Bryan (Figure 1). He was 33 years old and she was 18. Mr. Bryan had earlier been in Arkansas and wandered into Texas as early as 1839. It was not until 1844 that a surveyor laid out lots of one-half mile by one-half mile. He advertised the town but after 7 years had sold only 86 lots. Mr. Bryan left for the California gold fields in 1849. He returned to Dallas in 1851 and in 1852 sold his townsite real estate to Alexander Cockrell for $7000 (2). During his lifetime he sold most of his land at relatively cheap prices and thus did not profit from his real estate.

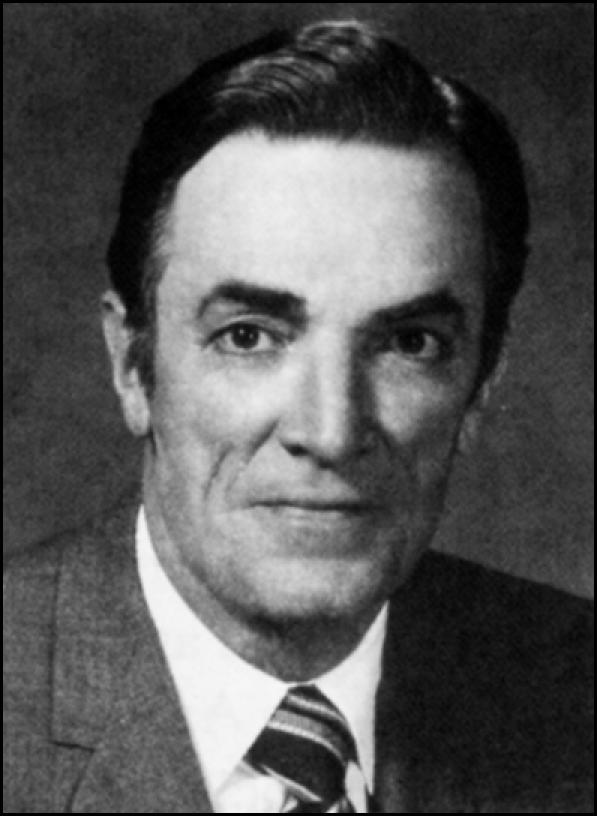

Figure 1.

John Neely Bryan, founder of the city of Dallas, with wife, Margaret. From the collections of the Texas/Dal las History and Archives Division, Dallas Public Library.

In 1842, Dr. Calder became the area's first physician. He settled at Cedar Springs and was killed by Indians the following year in Collin County. In May 1843, Dr. John Cole, originally from Virginia, moved to Dallas from Fayetteville, Arkansas. Cole Avenue, the street where he practiced, was named for him in 1882 following his death in 1850. Early physicians often had other jobs, mostly as farmers, as Dr. Cole had been. There was no surgical specialty since all physicians were known as physicians and surgeons. There were no hospitals, and physicians might ride a horse several miles to get to their patients.

The Republic of Texas had already passed a law creating a Board of Medical Censors on December 14, 1837. The board met annually to evaluate credentials and reputations of physicians (3). Four years after Dallas was founded, Texas became the 28th state under the governorship of Sam Houston. The following year, 1846, Dallas was named temporary seat of Dallas County, which was named for Vice President George Mifflin Dallas. The city was not officially incorporated until 1856.

MEDICINE IN DALLAS, 1850–1875

The population of Dallas in 1850 was approximately 1000, with 430 families (3). The primary industries were cotton production and railroad transportation. It was fairly easy to get into medical school by today's standards, since only a high school diploma or the equivalent was required—and that meant applicants could have as few as 8 or 10 high school credits. Medical school was only 2 years; thus, a student could have a diploma of medicine 2 years after high school graduation. However, to practice medicine it was not necessary to have a diploma but merely to appear before a district board appointed by some judges and successfully answer some questions. Students who passed the examination were eligible to legally practice medicine. Many physicians—including Dr. Charles M. Rosser, who was considered the founding father of Baylor University College of Medicine–practiced medicine between their first and second years of medical school. This was a common way to finance medical school education. Dr. Rosser returned to the University of Louisville to finish his second year of medical school in 1888 (4).

When a physician received a diploma, it was registered with the county clerk or with the health officer. The physician received some ethical instruction and could be called a “specialist,” although none were trained as such. These “specialists” were much more at ethical risk than so-called “primary care physicians.” There were some ethical restrictions: for example, Dr. Daniel W. Momand was severely reprimanded for attempting an operation on a horse (4).

Physicians performed the only operations known to pioneers, which were amputations and treatment of wounds in the home. Even appendectomies were not performed. Physicians were informed that the average office fee was $1 and a home visit was $2. If they traveled out of city limits by horseback, they could charge 50¢ per mile. They carried their drugs with them since the first drug store in Dallas was not established until 1855 by Frank A. Sayre. It was located at the corner of Houston and Main on the west side of the city square. The first railroad came to Dallas in 1872, which later accounted for explosive growth of the city (5).

In 1874 the first City Hospital was built (Figure 2). Prior to this, hospitals were in shacks. The City Hospital was a single room built on a piece of property owned by Mr. Long, which was sold for $1000. The building was approximately 50 × 50 feet, housed 18 people in one room, and cost $250 to build. It was located on the corner of South Lamar and Columbia Streets. Later a woman's facility and kitchen were added. There was no indoor plumbing, and sewerage was a problem. No one was available to pick up dead animals. The city health officer was the one primarily responsible for the hospital.

Figure 2.

Dallas' first City Hospital, built in 1874. Photo courtesy of Parkland Health and Hospital System.

SURGERY IN DALLAS, 1875–1900

By 1870 the population of Dallas was 3000, and by 1890 it was 38,000, making Dallas the largest city in Texas (1) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Downtown Dallas about 1873. Photo courtesy of the Center for American History at the University of Texas.

Dr. Henry Keirn Leake (1875)

The first private infirmary in Dallas was constructed in 1875 and was owned by Dr. Hughes and Dr. Henry K. Leake. Dr. Leake had moved to Dallas that year and began to specialize in surgery as a field separate from general medicine. He is credited with moving surgery from the home into the hospital. Dr. Leake was a pioneer surgeon and specialist in Dallas and the Southwest prior to 1900 (Figure 4). He was born in Yazoo City, Mississippi, in 1847. He was a member of the Confederate Army in Alabama and attended medical school at Louisville Medical School from 1867 to 1869, approximately 20 years before Dr. Charles M. Rosser. Dr. Leake founded the Leake Sanitarium for surgical cases in the early 1890s and was one of the first physicians in the Southwest to perform an appendectomy. The first appendectomy in the USA was not performed until around 1887. He had trained in London under Dr. Lawson Tate and received additional training in Berlin, New York, and the Mayo Clinic from 1885 to 1890. It was common for many physicians from Dallas to spend a few months at the Mayo Clinic and come back to Dallas as a so-called “specialist” in some particular area. Eventually, when St. Paul Hospital opened on June 15, 1898, Dr. Leake was the first chief of surgery (6). In addition to being president of the Texas State Medical Association, Dr. Leake was also editor of Texas Medical Record. He died in Dallas on October 30, 1916, and is buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

Figure 4.

Dr. Henry K. Leake.

The Dallas County Medical Surgical Association (1875)

The Dallas County Medical Surgical Association was founded in 1875 but lasted only 3 or 4 years. It was a forerunner of the Dallas County Medical Society (7). On April 1, 1876, the Dallas County Medical Society held its first meeting, and its first president was Dr. Albert Johnston. To be a member, the physician and surgeon had to have a diploma from a regularly constituted medical college recognized as such by the American Medical Association (AMA). The purpose of the organization was to establish a uniform fee for doctors to guarantee citizens against excessive charges. One of its original members was Dr. S. D. Thurston. The group met once a week in doctors' offices, which were usually over drugstores or dry goods stores (8). The name was changed to the Dallas County Medical and Surgical Society on August 8, 1876, but the organization disbanded in 1879.

Dallas County Medical Society (1884)

In 1884 the Dallas County Medical Society that we know today was established. Its first meeting was held on April 3,1884, in the offices of Dr. Robert Henry Chilton and Dr. Joseph H. Smith. After the first few meetings in Dr. Chilton's office, the 30 members of the 37 eligible candidates began to meet in the basement of City Hall at the present site of the Adolphus Hotel. The first president of the Dallas County Medical Society was Dr. John Morton, 1884–1887, who died in office on July 18, 1887. Dr. Morton was born in Rutherford County, Tennessee, in 1831 and graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School. He served in the Russian Army and moved to Dallas in 1875, opening an office at 602 Main Street. Many of the physicians at that time practiced on Main Street and Lamar Street (9).

First trained surgical specialist in Dallas (1880)

Dr. Robert Henry Chilton came to Dallas in 1880 and was the only trained specialist in Dallas in the 1880s as an eye, ear, nose, and throat specialist. He was born in Cumberland County, Kentucky, in 1844 and started practicing medicine in 1864 at age 21 years, but he did not graduate from Miami Medical College in Cincinnati until 1870. Dr. Chilton had studied ophthalmology and otolaryngology at the University of Louisville and served on the staff of the City Hospital (10).

Pest houses (1876, 1882)

In 1876 and 1882, there were pest houses—which were usually shacks—primarily for the purpose of taking care of smallpox patients (11). However, in 1907, the Union Hospital was constructed about 4 miles from Main Street and took the place of the pest houses (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Union Hospital, built in 1907. Photo courtesy of Parkland Health and Hospital System.

Stock market crash (1878)

There was a huge stock market crash in 1878. The Dow Index dropped from 55 to 20, far from the 9000 to 11,000 we know today. Some of the rail line stocks dropped 60%. By 1881 telephone exchanges opened in Dallas (1).

Germ theory (1885)

By 1885 there were 65 physicians in Dallas (12). They did not accept the “germ theory,” and there was no asepsis. It was not until 1890 that physicians even wore gloves during surgery. They commonly walked from one surgical procedure to another without even washing their hands.

St. Paul Hospital (1898)

The physicians in Dallas wanted a larger hospital with an open staff. Dr. C. M. Rosser and some other physicians petitioned the Sisters of Charity of Emmitsburg, Maryland, to open a general hospital in Dallas. They eventually agreed to do this, and in 1896 the hospital was chartered. The main St. Paul Hospital opened on June 15, 1898, with 110 beds (Figure 6). This was important because it was the first facility to have an open staff. Dr. Henry K. Leake was the first surgeon in chief.

Figure 6.

St. Paul Hospital. Photo courtesy of St. Paul Hospital.

By 1900, Dallas had a population of 42,638, and the population almost doubled every decade. There were 146 physicians, and during the first decade of the century, 8 medical schools were organized in Dallas. In Texas, the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, organized in 1891, is the only school still in existence that was established before 1900.

Dr. V. P. Armstrong and the first Parkland Hospital (1894)

Dr. Charles M. Rosser was city health officer in 1891. In that year, Dr. Rosser was surgeon and chief at the Dallas City Hospital. Dr. V. P. Armstrong moved to Dallas in 1890 and went into practice with Dr. Rosser. Dr. Armstrong became health officer in 1892 following Dr. Rosser (Figure 7). He recognized the poor sanitary conditions that existed and finally convinced the city council to appropriate money to build a new hospital. Dr. Armstrong is credited with the development of the first Parkland Hospital, which opened on May 19, 1894, on 17 acres of park land at the corner of Maple and Oak Lawn (Figure 8). The newspaper ad stated that it was “the most elegant in the state and for terms of admission as to surgical cases, inquiries should be addressed to Dr. V. P. Armstrong who is 'Surgeon in Chief.'” Therefore, Dr. V. P. Armstrong was the first chief of surgery at the first of three Parkland Hospitals in Dallas.

Figure 7.

Dr. V. P. Armstrong.

Figure 8.

The first Parkland Hospital, about 1895. Photo courtesy of the Dallas Public Library.

All patients admitted after March 14, 1894, had to be bona fide residents of the city of Dallas, although eligibility has since been expanded to residents of Dallas County. Parkland Hospital was 2 stories and had 100 beds. There were 6 separate wards: one for white women, one for black women, one for white men, one for black men, one for children, and one for maternity cases. The single operating room had a cement floor. Dr. Armstrong, the county health officer, and his family lived in the hospital. The charge for a private room was $7 to $12 per week.

Dr. Armstrong was born in Davidson County, Tennessee, on February 18, 1855. He went to Notre Dame University and graduated from medical school at the University of Louisville in 1877. He studied at numerous universities abroad and practiced 13 years in Caldwell, Texas, before moving to Dallas in 1890. He died in Oak Cliff at home on November 30, 1923 (13).

The city bought its first ambulance, a buggy, in 1894 for $500 but did not have enough money for a horse to pull it. The horse was not purchased until 1896 for $100, and 3 years later, Health Officer John W. Hicks Florence insisted that rubber wheels be purchased for the wagon ambulance for humanitarian reasons since the ride was so rough (14) (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Dallas' first buggy ambulance, 1894. Photo courtesy of Parkland Health and Hospital System.

Clinics, infirmaries, surgical institutes, and hospitals (1875–1900)

Several small clinics and hospitals were established in the later part of the 1800s. The first was the Dallas Medical Institute, established in 1875. Following that, the Dallas Sanitarium, with Dr. Carl Murray as proprietor, existed from 1881 to 1882. From 1884 to 1885, the sanitarium was renamed Dallas Medical and Surgical Institute; however, it was not listed after 1885.

The Weden and Temple Medical and Surgical Institute opened in 1893 at 333 Elm Street at the corner of North Akard, managed by Dr. Weden Smith and Dr. Temple Smith. Dr. Leake's private hospital, located at 176 South Pearl at the northeast corner of Pearl and Polk Streets, was the only hospital open to all physicians. It opened in 1894 and closed in 1914.

THE BEGINNINGS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF DALLAS MEDICAL DEPARTMENT AND THE TEXAS BAPTIST MEMORIAL SANITARIUM, 1900–1920

Establishment of the University of Dallas Medical Department (1900)

The driving force behind starting the University of Dallas Medical Department was Dr. Charles McDaniel Rosser (Figure 10), a native of Georgia who came to Texas in 1865 at the age of 4 years and settled near Pittsburg (15). Following medical school at Louisville, he returned to Waxahachie, Texas. Four years later in 1891, he was appointed health officer for the city of Dallas. He was also appointed surgeon and chief of the Dallas City Hospital. He resigned as public health officer after 1 year to become surgeon of Houston and Texas Central Railroad and chairman of the medical section of the Texas Medical Association. In 1895 Dr. Rosser was appointed superintendent of the North Texas Hospital for the Insane at Terrell but resigned in 1897 to join Dr. Samuel E. Milliken of Dallas as a partner in private practice. Dr. Rosser, by this time, was convinced that Dallas needed its own medical college.

Figure 10.

Dr. Charles Rosser, father of the University of Dallas Medical Department/Baylor University College of Medicine.

On August 14, 1900, at the office of Dr. J. B. Titterington and Dr. V. P. Armstrong (the first chief of surgery at Parkland Hospital), there was a meeting along with Drs. Rosser, Lawrence Ashton, J. P. Gilcreest from Gainesville, Joe Becton of Greenville, Texas, and A. F. Beddoe, B. E. Hadra, and Sam Milliken, all from Dallas. They decided it was time to organize a medical school in Dallas and went to Mayor Cabell, who immediately ran a newspaper advertisement announcing that all reputable physicians were to meet in the council chambers of City Hall on Thursday, August 16, at 8:30 PM for the purpose of taking preliminary steps to establish a medical college in Dallas. The advertisement was signed by Mayor Ben E. Cabell, Charles Steinman, president of the Commercial Club, and W. J. Maroney, a prominent attorney (16, 17).

Only 15 of the 55 physicians who attended the meeting favored a medical school. Those who favored the medical school included Drs. C. M. Rosser, Sam Milliken, Lawrence Ashton, V. P. Armstrong (a surgeon), and J. B. Titterington (an ophthalmologist and otologist). They had the backing of the mayor and city councilmen, as well as the influential businessmen. The opposition was led by Dr. Stephen Thurston, an original member of the Dallas County Medical Surgical Association, and he was supported by St. Paul Hospital. Dr. Rosser chastised many of the other physicians who thought there were too many medical colleges and there weren't enough faculty members capable of instructing medical students. He stated, “There may be some here that would not want to organize a medical college, but if there is going to be one they would like to be in it. I tell you now, not as a threat but as a matter of information, there is going to be one.” The Dallas Morning News published the next day that there was forced adjournment of the meeting but approximately 15 physicians remained (18).

The charter for the University of Dallas Medical Department was filed with the secretary of state 1 month later on September 15, 1900. The college leased a Jewish synagogue, the former Temple Emanu-el (Figure 11). The medical college officially opened its doors on November 19, 1900, in the Jewish synagogue in what is now the 1300 block of Commerce Street, across from the present site of the Adolphus Hotel. This would eventually be Baylor University College of Medicine. Not having a university affiliation would be a problem.

Figure 11.

Temple Emanu-el, the first building for the University of Dallas Medical Department. Photo from Dallas Historical Society Archives.

Dr. J. B. Titterington was appointed dean, acting secretary, and professor of anatomy and eyes, ears, nose, and throat. Dr. Titterington, a native Dallasite, was born in Dallas County in 1868 and was an 1897 graduate of New York's Bellevue Hospital Medical College. After postgraduate training in ophthalmology and otolaryngology in London, he returned to Dallas in 1898.

First chief of surgery and a faculty revolt (1900)

Dr. Sam Milliken was the first chief of surgery at the University of Dallas Medical Department (Figure 12). Other faculty included Dr. Gilcreest, an 1876 graduate of the University of Missouri Medical School. He was designated president of the medical school and teacher of gynecology. Dr. Charles Rosser taught clinical medicine and mental and nervous diseases.

Figure 12.

Dr. Sam E. Milliken.

The medical school had been opened only 2 months when a faculty revolt occurred during Christmas vacation, 1900. Dr. Titterington, dean and acting secretary, and his partner, Dr. Sam Milliken, chief of surgery, decided to take possession of the medical school without the knowledge of Dr. Rosser and Dr. Armstrong. One night they replaced the medical school's sign, changing it from the University of Dallas Medical Department to Dallas Polyclinic Medical College. This infuriated Dr. Rosser. He sought a court injunction and won, and Drs. Titterington, Ashton, and Milliken had to resign. Dr. Rosser became the dean in place of Dr. Titterington on January 4, 1901 (18).

Dr. Milliken was born on December 2, 1866, in Mansfield, Texas. He graduated from the University of Louisville in 1887 and was probably a classmate of Dr. Charles Rosser. He did postgraduate work from 1889 to 1897 at New York Polyclinic and was in the private practice of medicine and surgery at Elm and St. Paul Streets between two tombstone factories. Dr. Milliken moved to Dallas in 1897 and partnered with Dr. C. M. Rosser to codirect Hermitage Hospital, located at 449 Elm Street. He was also proprietor of the Polyclinic Infirmary at 228 S. Ervay until 1902. He served as president of the Dallas County Medical Society in 1916. Dr. Milliken was a fellow of the American College of Surgeons and practiced surgery in Dallas until he retired in 1941. He died in 1949 (19).

Second chief of surgery (1900)

In 1900, after Dr. Milliken's forced resignation, a delegation of Dallas physicians asked Dr. Berthold Ernest Hadra and his friend Dr. J. T. Harrington to come to Dallas and have Dr. Hadra head the surgical department at the University of Dallas Medical Department.

Dr. Hadra had become professor of surgery in 1888 at the medical college in Galveston but was replaced in 1891 by Dr. James Thompson from England. In 1900, as he came to Dallas, he was elected president of the Texas Medical Association. With the new faculty, the staff included Dr. J. M. Inge of Denton, Texas, who taught surgical anatomy. Dr. Joe Becton of Greenville was the head of operative surgery, and Dr. T. B. Fisher was instructor in surgery.

At the end of the first semester in 1902, the medical school was reorganized, and Dr. B. E. Hadra was appointed professor of clinical surgery and vice president of the faculty (Figure 13). He is likely the second chief of surgery at the University of Dallas Medical Department. Dr. Hadra was born in the village of Ofen, near Brieg, Silesia, then part of Germany, on November 8, 1842 (20). He was educated at the University of Breslau and Berlin and acquired the qualifications necessary to permit him to practice medicine and surgery. He became an assistant surgeon in the Prussian Army and in 1866 served during the Seven Week War between Austria and Germany. Dr. Hadra married Auguste Beyer, and in 1869 he and his wife came to the USA from Germany. A son named Frederick was born on the voyage and became a distinguished surgeon himself, with a rank of major in the US Army during the Spanish-American War. Upon arrival in the USA, the family settled in Houston, Texas, and remained there from 1870 until 1872. On February 9, 1872, Dr. Hadra opened an office in Austin and was considered an excellent surgeon (21). He was a very prominent physician and was appointed a regent of the University of Texas in May 1883. He was associated with Dr. Ashbel Smith on the board of regents. Dr. Smith was considered one of the most intellectual physicians of Texas. In 1878 and again in 1891, Dr. Hadra practiced in San Antonio. In 1885 he again practiced in Austin. Dr. Hadra had practiced in several towns, including Waco, where he lived for about a year in 1899.

Figure 13.

Dr. B. E. Hadra.

A close friend of Dr. Hadra was Dr. J. Marion Simms, a renowned gynecologist of New York. In fact, Dr. Hadra was associated with Dr. Simms and named his son James for him. Dr. Simms is credited with developing a surgical cure for vesicovaginal fistula, and a gavel was presented to the Southern Surgical Association from his operating room table in 1895. He became famous as a surgeon in Europe.

Dr. Hadra published articles in such journals as the American Journal of Obstetrics, Journal of the American Medical Association, New York Medical Journal, Boston Medical Journal, and Texas State Medical Journal. He was considered an excellent surgeon and diagnostician and soon became internationally known. Patients came from many countries, and he had a large clientele from Mexico. In 1888 two outstanding events occurred: one was the publication of his book Lesions of the Vagina and Pelvic Floor and the other was his acceptance of the appointment as professor of the science and art of surgery at Galveston Medical College, which had been in existence since 1866 and was the predecessor of the University of Texas Medical Branch. Dr. Hadra is credited with being the first surgeon in the world to recognize the relationship of the diaphragm to rectocele and cystocele and to devise an operation for correction of these conditions (22). Dr. Hadra has been given credit for the beginning of modern operations for prolapse.

In 1891, while at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, he was replaced by Dr. James Thompson from England. Dr. Hadra became president of the Texas Medical Association in 1900 while living in Waco. During that year he moved to Dallas to become professor of clinical surgery at the University of Dallas Medical Department. At the same time Dr. Hadra was appointed professor of surgery, Dr. J. B. Becton was appointed head of operative surgery (Figure 14). Dr. Becton was a charter member of the Texas Surgical Society, which was founded in 1915.

Figure 14.

Dr. J. B. Becton.

On January 12, 1903, at 10:00 PM, Dr. Hadra was found dead by his son James. He was seated in a chair in the office located on Elm and Akard Streets. He was 60 years of age and held the position of professor of clinical surgery at the University of Dallas Medical Department. Burial was in Austin, Texas.

Surgical anatomy (1900)

Around 1900 the principal method of teaching was by lectures. In such courses as human anatomy, the only cadavers available for dissection were unclaimed bodies snatched on the sly, either before or immediately after burial in pauper's graves. Two medical students worked their way through school by transporting bodies to the school's dissecting room (23). In 1903, the professor of anatomy at the medical college was Dr. Kent V. Kibbie (24).

The Good Samaritan Hospital (1901)

One of the main obstacles in producing fully qualified physicians was the lack of a hospital in which medical students could receive clinical training. The staff sought permission from the city council to have access to the wards and operating rooms of Parkland for teaching purposes. The senior students needed to have bedside and operating room training. Dallas municipal authorities agreed to allow the students to attend patients at city-operated Parkland Hospital (25). Thus, three times a week, students traveled by wagon across the town to the city hospital for clinical practice and observation, since it was too far to walk. Dr. Rosser approached St. Paul Hospital about rotating students there; however, the sister refused (26). He then contacted Col. C. C. Slaughter, the famed cattle baron who was worth millions, in hopes that he might fund a hospital for the new medical school.

Dr. Rosser, the dean, in the meantime decided to form a private hospital. He purchased the 14-room brick mansion on Junius Street known as “Hopkins Place.” The house was built in 1880 by Col. W B. Wright, an early day pioneer. It had previously been owned by Captain W. H. Gaston, for whom Gaston Avenue is named; however, it was owned by Judge M. L. Crawford when Dr. Rosser purchased it. The purchase price was $22,500 to be paid out over an extended period. The house was remodeled to provide space for a ward, an admitting area, and operating rooms, and by 1901 the mansion was ready to begin functioning in its new role as the city's second privately owned and operated general hospital. It was named the Good Samaritan Hospital, which was the forerunner of Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) (25) (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Good Samaritan Hospital.

First graduating class (1902)

The first class to graduate from the University of Dallas Medical Department in 1902 had 19 students (Figure 16). Graduation was held at the Carnegie Library (Figure 17). By the second session in 1902, only 30 of the 66 students returned. In 1901, the Texas State Board of Medical Examiners had been created. Prior to this, Texas required only $15 in the absence of a diploma to practice medicine.

Figure 16.

The faculty and first graduating class of the University of Dallas Medical Department, 1902. Front row, left to right: Dr. Charles M. Rosser, founder of the medical school and first dean; Dr. J. H. Florence of Houston, first professor of obstetrics; Dr. B. E. Hadra, first professor of surgery; Dr. J. E. Gilcreest of Gainesville, first professor of gynecology; Dr. W. M. Lively of Oak Cliff, professor; Dr. A. F. Beddoe, professor of pediatrics; Dr. A. Bell, first professor of physiology; Dr. J. M. Inge of Denton, first professor of anatomy; and Dr. James E. Wilson, assistant professor of obstetrics. The woman in the front row is listed as a student.

Figure 17.

Carnegie Library, a part of the Dallas Public Library system, in 1901. Photo from Dallas Historical Society Archives.

Burning of the Jewish synagogue (1902)

The faculty was constantly changing. All faculty members were volunteers, and teaching was a chore. They were discontent with the school's lack of progress. They had no university affiliation, and often faculty failed to meet their teaching assignments. To further complicate things, on February 4, 1902, the east half of the Jewish synagogue burned. Mayor Cabell made City Hall auditorium available for lectures. There were several times during the medical school's history that City Hall came to its aid. The school needed another building, so for $15,000, the College Building on Ervay was purchased. It was remodeled in time for the school to open in October 1902 (Figure 18). It would house the medical school for the next 4 years.

Figure 18.

The College Building.

The College Building also included a 12-bed emergency hospital, primarily a charity hospital with operating rooms and obstetrics, that was later moved to Dallas City Hall.

At the time of relocation of the school to the College Building, the president was Dr. J. M. Inge, the vice president was Dr. E. H. Cary, and the secretary and treasurer was Dr. Elbert Dunlap. Commencement exercises for the 1902–1903 session were held on April 3, 1903, in Lecture Hall A in the College Building. Only 3 students met the attendance and course completion requirements of the 4-year program to be eligible for graduation.

A new dean (1902)

Dr. E. H. Cary was recruited as professor of ophthalmology and otolaryngology. One year after Dr. Cary came, he was named chief of ophthalmology, and 3 months later, on April 15, 1902, he was made dean of the medical school to replace Dr. Rosser (Figure 19). Dr. Cary was dean from 1902 until 1920. The school was in a desperate financial situation. Tuition was $75 per year, with only 60 students enrolled, and the entire budget was only $5000. Nevertheless, Dr. Cary would guide this school for the next 50 years and would become chairman of the Department of Surgery of Baylor University College of Medicine in 1925.

Figure 19.

Dr. E. H. Cary, dean from 1902 to 1920.

Baylor University affiliation (1903)

The population of Dallas in 1903 was 45,000, and Teddy Roosevelt was president. There were only 40 cars in Dallas, and the average life expectancy in 1900 was 47 years.

In June 1903, negotiations were begun in the hope of establishing an affiliation with Baylor University in Waco, Texas. At this time there were several hospitals in town, including Parkland Hospital, St. Paul Hospital, Good Samaritan Hospital, Dr. Leake's private hospital, and the 12-bed emergency hospital in the college building (26). By the summer of 1903, at the annual meeting of the AMA in New Orleans, Dr. Cary heard Dr. Frank M. Billings, AMA president, say that the vast majority of privately owned medical schools throughout the nation were doomed and that within 5 years no medical school could survive without university affiliation. This impressed Dr. Cary (dean) and Dr. Rosser, and they agreed to secure university affiliation.

Within 3 weeks after Dr. Cary contacted Baylor University in Waco, they had an affiliation contract with the university. In return for that affiliation, the University of Dallas Medical Department had to donate all of its property to Baylor. The board of trustees was reorganized, and Dr. Cary quickly became vice chairman of the board of trustees of the medical college as well as dean. The property was given to Baylor University at Waco on June 29, 1903, just 3 years after the University of Dallas Medical Department had been founded. The name of the school was changed to Baylor University College of Medicine. Dr. Cary, who was vice chairman of the board of trustees and dean, was to serve as chairman of the board of trustees in the absence of President Brooks of Baylor University, who was ex officio chairman. This meant that Dr. Cary was not only dean but in reality chairman of the board of trustees, since President Brooks could rarely make a meeting due to the distance. Dr. C. M. Rosser was elected president of the faculty of Baylor University College of Medicine (27). Although university affiliation gave prestige to the medical college, Baylor University in Waco did not offer any financial aid to the medical school.

The first executive committee consisted of S. P. Brooks, chairman; E. H. Cary, vice chairman (ophthalmologist/otolaryngologist); Elbert Dunlap, secretary and treasurer (obstetrician/ gynecologist); C. M. Rosser (surgeon); Sam Milliken (surgeon); V. P. Armstrong (surgeon); and A. F. Beddoe (24).

Other medical schools (1903)

By 1903, there were 4 medical colleges in Dallas: Baylor University College of Medicine, Dallas Medical College, Physio Medical College of Texas, and Southwestern Medical School. In 1903 Dr. F. A. Bell, Dr. J. O. McReynolds (an ophthalmologist), Dr. Henry K. Leake, and Dr. J. M. Pace organized the Texas College of Physicians and Surgeons. This organization later became the Medical School of Southwestern University, Georgetown, Texas. Much later, the affiliation shifted to Southern Methodist University after that university was established (28).

Requirements for medical school entrance (1903)

Admission requirements for the 1903–1904 session stated that a student had to have a certificate from a legally constituted high school, a superintendent of state education, or a superintendent of some county board of education attesting to the fact that he or she possessed at least the educational attainments required of first-grade teachers of public schools. There were 11 graduates the first year after Baylor affiliation, and Dr. J. O. Hayes was the first graduate to be handed a diploma awarding a degree of doctor of medicine from Baylor University College of Medicine in 1904 (29).

The bloodless surgeon of Vienna and the vision of the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium (1903)

The Philip Armour family, of the Armour and Co. meatpacking plant of Chicago, had a child with congenital hip dislocation. They brought Dr. Adolf Lorenz of Vienna, Austria, to Chicago to treat their child. Dr. Lorenz subsequently lectured before the AMA in New Orleans in May 1903 and attracted wide publicity. Dr. Charles Rosser met Dr. Lorenz in Chicago, went to the meeting in New Orleans, and invited Dr. Lorenz to visit Dallas and give a clinical demonstration of his bloodless surgery under the auspices of the faculty of the University of Dallas Medical Department and the Good Samaritan Hospital, both of which had been founded and directed by Dr. Rosser. Dr. Lorenz arrived in Dallas on May 20, 1903, and held two clinics daily for a week, alternating between Good Samaritan Hospital on Junius Street and the College Building on Ervay Street (Figure 20). At the end of the week, a banquet was held at the Oriental Hotel honoring Dr. Lorenz, and the final address of the evening was given by the Rev. Dr. George W. Truett. At the age of 36 years, he stated in his address, “Is it not now time to begin the erection of a great humanitarian hospital, one to which men of all creeds and those of none may come with equal confidence?” It is thought that Dr. Truett's address motivated individuals to found the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium, which would eventually become BUMC.

Figure 20.

Drs. Blount, Lorenz, Cary, and Rosser in front of the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium.

Col. C. C. Slaughter was contacted and originally was to give $25,000, but because he was so wealthy he was asked to give $50,000. Col. Slaughter not only gave $50,000 but also agreed to give $2 for every $1 contributed from other sources. J. P. Wilson, builder of the downtown Wilson Building, also gave $50,000 to match Col. Slaughter's original gift. In June 1903, the hospital project was undertaken by the Baptist General Convention of Texas (30).

Col. Slaughter was one of the wealthiest people in the USA. He was born in Sabine County, Texas, on February 9,1837, when Texas was still a republic. His father was George Webb Slaughter, who served as Sam Houston's chief of scouts during the Texas Revolution and was the last Texan to see the defenders of the Alamo alive. It is estimated that Col. Slaughter gave a half million dollars to the sanitarium and medical school between 1903 and 1919 (Figure 21). His heirs continued to be benefactors to Baylor Hospital. Notable among them was his daughter, Minnie (Mrs. George T. Veal), who subsequently became Baylor Hospital's greatest financial benefactor. Col. Slaughter's “Steamboat Victorian” home (Figure 22) was originally built by Col. W. E. Hughes, owner of the Grand-Windsor Hotel.

Figure 21.

Col. C. C. Slaughter with his wife.

Figure 22.

The home of Col. C. C. Slaughter, 1890. Photo courtesy of Old City Park, the Historical Village of Dallas, Dallas, Texas.

Purchase of Good Samaritan Hospital by the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium (1903)

At a meeting on October 26, 1903, 3 days after the first meeting of the board of directors of the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium, Dr. Rosser offered the Baptists the opportunity to purchase his Good Samaritan Hospital at the same price he had paid for it and presented them with all of his equipment. The board accepted on October 30. The Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium officially opened in the building formerly called the Good Samaritan Hospital on May 11, 1904 (31).

Within 6 months of the opening of the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium, it was decided that a new hospital should be built. On February 25,1905, the board of directors decided to shut down the building they had bought from Dr. Rosser and not admit any more patients because they were concerned that it would be unsafe for patients to be so close to work and noise while the new hospital was being built. Thus, from March 11, 1905, until mid October 1909, no patients were treated at the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium (the former Good Samaritan Hospital).

New requirements for medical schools (1905)

During the middle of 1905, the first session of the Council on Medical Education of the AMA was held. A medical school required 4 years of at least 30 weeks per year as determined by the Joint Conference of the Council on Medical Education. A total of 4000 hours of actual instruction was required by the Association of American Medical Colleges. Baylor University College of Medicine recognized these requirements and knew the critical need for more funds and more facilities. As a result of the higher standards set by the council, from 1905 to 1910 the number of medical colleges in the USA was reduced from 162 to 131, the number of students from 28,142 to 21,526, and the number of graduates per year from 5600 to 4440.

Sale of College Building; opening of Ramseur Science Hall (1906–1909)

Mrs. P. S. Ramseur of Paris, Texas, gave the sanitarium her estate, including 9000 acres and $15,000 in cash, which gave an overall value exceeding $100,000. With the money, a new science building, the Ramseur Science Building, was built. Based on the assumption that the new building would be completed by October 1, 1906, the College Building on Ervay Street was sold to R. V and Cecil Rogers in July 1906, but Ramseur Science Hall did not open until 1909. Thus, the medical school moved into the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium on October 1, 1906, and remained there for 3 years (32).

Ramseur Hall housed all the departments of the medical college from 1909 to 1923 and was located near the current dental school (33) (Figure 23). A dispensary was established on the ground floor of Ramseur Hall, and this is the first definitive record of an outpatient department in the college. The dispensary was opened for the poorer of the city from 2:00 to 3:00 PM every day except Sundays and holidays.

Figure 23.

Ramseur Hall.

Legislative acts (1907)

Two legislative acts were passed by the 30th legislature for the state of Texas in 1907 that had significant influence on medical education in Texas. The first was the creation of the State Board of Medical Examiners, which became effective on July 13, 1907. The other was the creation of the State Anatomical Board, whose function was the procurement of anatomical material for medical schools, thus obviating private procurement of this material (34).

First interns from Baylor University College of Medicine (1907)

Six students graduated in 1907, and two became the first two interns appointed from the medical school. Miss Halle Earl, who had the highest class standing, was appointed intern at Dr. Gilcreest's Hospital in Gainesville, and M. F. Sloan was appointed intern at St. Paul Hospital (34).

First interns appointed to the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium (1908)

The ninth session of Baylor University College of Medicine opened on October 1, 1908, with an enrollment of 53 students and closed on Thursday, April 29, 1909, with commencement exercises held at the Bush-Temple Music Hall. Sixteen students graduated from Baylor University College of Medicine in 1909, and two were appointed interns at the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium: Dr. Audy V. Cash and Dr. W. W. Shortal, who would later become a member of the surgical staff at Baylor Hospital (35) (Figure 24).

Figure 24.

Intern record from the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium, 1909.

New building for the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium (1909)

The new Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium—the building that replaced the former Good Samaritan Hospital—opened on October 14, 1909, with 250 beds, including 114 private rooms, with every room having outside ventilation (32) (Figure 25). In 1910, nurses could expect to earn up to $4 for a 12-hour day without rest. The operating room fee was $15 for major operations and $10 for minor surgical procedures (Figure 26). A bed in a ward cost $10 per week, including board and nursing care (31).

Figure 25.

The new Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium building, built in 1909.

Figure 26.

Surgery at the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium, c. 1920.

The first decade (1900–1910)

The tenth session closed on April 26,1910, with 9 graduates. Thus, for the first 10 years, the college had 134 graduates. In 1910, two medical schools remained in Dallas: Baylor University College of Medicine and Southwestern University College of Medicine, both of which were struggling for existence. During the first 10 years, 1900–1910, Baylor University College of Medicine had occupied 4 buildings: first, the leased Jewish synagogue, former Temple Emanu-el on Commerce Street damaged by fire in February 1902; second, the College Building on South Ervay Street; third, the original Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium on Junius Street; and fourth, Ramseur Science Hall in 1909. No record is available of any specific research projects engaged in during the time. The college had overcome the opposition of its foundation in 1900 and survived the faculty insurrection early in the first session. At the end of the l0-year period, the faculty consisted of only 2 full-time and 28 voluntary members.

Acceptance into the Association of American Medical Colleges (1910)

The Flexner Report of 1910 was critical of Baylor University College of Medicine, noting that the requirements for admission were low and basically there was a need for financial resources. During the 1910–1911 academic year, the library was organized and housed in the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium. Rules and regulations recommended by the board of trustees at a meeting on June 1, 1911, stated that one negative vote by a faculty member would be sufficient reason to prevent a student from graduating. The second regulation was that the registrar keep class standings (35). In 1911, Dr. Walter H. Moursund, a 1906 graduate of the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, joined the faculty as assistant in pathology and bacteriology. He would later become dean of the medical school and go with it when it moved to Houston. On February 13, 1913, at a meeting in Chicago, Baylor University College of Medicine was elected to membership in the Association of American Medical Colleges (36).

Departmental organization (1913)

It was not until the 1913–1914 session that all branches of the curriculum were set up in departments. The departments included anatomy, physiology, pharmacodynamics, chemistry, pharmacology, pathology, bacteriology and hygiene, medicine, surgery, and gynecology and obstetrics (37).

More admission requirements (1913–1917)

At the June 13, 1913, meeting, the Texas State Board of Medical Examiners announced that only graduates of class A and B medical schools would be accepted for examination for licensure. Baylor University College of Medicine was rated class Bat that time. By the time the 14th session (1913–1914) opened, only 3 of the 5 applicants for the freshman class were accepted due to new admission requirements, which included physics and German or French. By the 1915–1916 session, biology, physics, and chemistry were all required for admission (37).

The only other medical college operating in Dallas was Southwestern University Medical College, which had become the Medical Department of Southern Methodist University on April 14, 1911. It closed on June 14, 1915, and those students were accepted as transfers by Baylor University College of Medicine. When the 16th session closed on May 31, 1916, the honorary degree of doctors of laws was conferred by Baylor University on Dr. E. H. Cary, dean of the medical college (38). Finally, on June 12, 1916, the Council on Medical Education awarded the college a class A rating (39).

With the opening of the October 1, 1917, session, requirements for admission increased to a minimum of 2 years of college work. The Medical Department of Texas Christian University of Fort Worth announced that it would not open for another session after 1918. It merged with Baylor University College of Medicine since it lacked an endowment and could not accommodate the higher entrance requirements. Thus, Baylor was the sole surviving medical school not only in Dallas but also in North Texas in 1918 (40).

Second Parkland Hospital (1914)

Under the auspices of the Masonic Lodge, the cornerstone for a new city hospital was laid on March 18, 1913, with impressive ceremonies. On February 1, 1914, the new and second city-county Parkland Hospital opened at Oak Lawn and Maple Avenues in far North Dallas (Figure 27). The city continued to operate its emergency hospital separately in the City Hall (39).

Figure 27.

Parkland Hospital, built in 1914 and vacated in 1954; the building is now the Woodlawn Building. Photo courtesy of Parkland Hospital.

World War I and Hospital Unit V (1917)

President Wilson declared war on Germany on April 6,1917, and doctors were rapidly mobilized. A military hospital unit, designated as Hospital Unit V, was organized at Baylor, and members of the Baylor faculty, including Dr. W. W. Shortal, surgeon (captain) and Dr. Samuel D. Weaver, surgeon (first lieutenant), were among those in the unit. They did not return to the USA until February 1919 (41). Although Dr. Gary, then president of the Texas Medical Association, wanted to volunteer and head for France, President Brooks at Baylor in Waco convinced him that he was needed more at home than overseas. Thus, Dr. Cary was largely responsible for the reorganization and training of the Baylor Medical Surgical Unit formed in 1917, composed of sanitarium staff and medical school faculty. Dr. Cary secured authority from Washington to develop a Student's Army-Training Corps at Baylor, and the entire student body was organized. The government paid student tuition fees, but Dr. Cary had to borrow another $100,000 to build barracks and provide food for the students. The war ended on November 11, 1918, and almost 10 million had been killed, including 115,000 Americans. Two months later, on January 25, 1919, Col. Slaughter died (40).

Burning of City Hospital (1918)

In 1918, the original frame City Hospital Building, built in 1874 and used for infectious and contagious diseases, was destroyed by fire. The patients were transferred to the main building of Parkland Hospital on Oak Lawn Avenue (42).

Surgery specialty requirements (1920)

In 1920, the Council on Medical Education of the AMA appointed 9 committees to formulate requirements of necessary graduate training to prepare practitioners to become specialists. The two main groups were medicine and surgery. Under surgery were ophthalmology, otolaryngology, orthopaedic surgery, and urology (43).

Teaching hospital designation (1920)

After World War I, the clinical facilities were reorganized, and Baylor trustees designated the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium as the official teaching hospital for the medical school and limited practice in the sanitarium to medical school faculty and members of the sanitarium staff (44).

Early surgical faculty (1903–1925)

In the 1903–1904 catalog, Baylor University Bulletin, Dr. Samuel E. Milliken is listed as professor of the principles and practice of surgery (24). Dr. Vernando P. (V. P.) Armstrong is listed as professor of gynecology and abdominal surgery. Dr. J. M. Inge is listed as emeritus professor of clinical surgery. Later catalogs list Dr. W. R. Blailock as professor of the principles and practice of surgery in 1904–1906 (45). Dr. V. P. Armstrong was professor of the principles and practice of surgery in 1906–1907 (46). In the 1904–1905 Bulletin, Dr. W. W. Samuel is professor of operative surgery and was so until 1908. These latter three surgeons followed Dr. Hadra in surgery, but it is unclear who was chief of surgery if there was one.

Dr. Garfield McCoy Hackler. In the 1905–1906 catalog with announcements for 1906–1907, Dr. Garfield McCoy Hackler is listed as professor of the theory and practice of medicine (47). Dr. Hackler's obituary in the Texas State Journal of Medicine in June 1937 states that he was born in 1865 in Independence, Virginia (48). He graduated from medical school at the University of Maryland in Baltimore in 1891 and did postgraduate work in New York, Chicago, and New Orleans. In 1907 he went to London and Leeds to study local and spinal anesthesia in surgery. In 1894 he located at Ennis, Texas, where he practiced for 10 years before moving to Dallas in 1904. After coming to Dallas he was associated with Baylor University College of Medicine as chairman of medicine from 1904 to 1907, at which time he became professor of the principles of surgery in 1911; 18 years later, he was appointed professor of surgery. He became one of the senior surgeons and participated in the groundbreaking ceremony for the new sanitarium building. Dr. Hackler was a member of the Texas Surgical Society, the Southern Clinical Society, and the Southern Medical Association. He became a fellow of the American College of Surgeons in 1915. He was a member of the First Baptist Church and died shortly after suffering a stroke in his office on May 6, 1937 (48).

Dr. Charles M. Rosser. In the 1906–1907 catalog for Baylor University, Dr. Charles M. Rosser is listed as professor of surgery. Dr. Rosser was born in Cuthbert, Georgia, on December 22, 1862. His father, Rev. M. F. Rosser, was a well-known Methodist minister who had served in the Confederate Army. The family moved to Texas in 1865, locating in Camp County. Dr. Rosser received his medical degree from the University of Louisville in 1888. He moved to Waxahachie, Texas, to practice medicine and teach school. Dr. Rosser moved to Dallas in 1890 for the practice of medicine and surgery and was one of the first Texans to confine his work entirely to surgery. He was married in 1897 to Alma Curtice of Eminence, Kentucky. They had two children, Dr. Curtice Rosser and Mrs. George McBlair of Dallas. In later years, the elder Dr. Rosser practiced with his son. He was considered the father of Baylor University College of Medicine at Dallas. In 1901 he founded the Good Samaritan Hospital in Dallas, which was the predecessor of the present BUMC.

Dr. Charles Rosser was an eloquent speaker, able to recall sentences and paragraphs from speeches and writings of months and even years past. He was president of the Southwest Surgical Association from 1904 to 1907 and of the Dallas County Medical Society in 1923. He was the 58th president of the Texas Medical Association in 1925–1926. He was a fellow of the American College of Surgeons and served as president of the first Texas State Board of Health. Dr. Rosser died on January 27, 1945, following an extended illness (49). It is likely that he was in charge of surgery at some time around 1910–1912, but this is unclear.

Dr. W. W. Shortal, first intern Dr. Shortal (Figure 28) was born in Ragsdale, Fannin County, on July 13,1886. He attended Honey Grove High School and graduated from Baylor University College of Medicine in 1909. He entered private practice in Dallas, specializing in general surgery. After serving as a major in World War I, he became clinical professor of surgery at Baylor University College of Medicine. According to the Dallas Medical Journal dated February 2, 1968, Dr. Shortal was chief surgeon at Scottish Rite Hospital from 1930 to 1936 and was chief surgeon at the City-County Hospital from 1920 to 1934. In 1933 he started the Shortal Clinic. He became a member of the American College of Surgeons in 1920. Dr. Shortal died on January 26, 1968, and was buried at Sparkman/Hillcrest at Northwest Highway (50, 51). In the 1909–1910 catalog, Dr. W. W. Shortal is listed as a faculty member and demonstrator of anatomy (52). He was the first intern from Baylor University College of Medicine. By 1916 he was listed as professor of applied anatomy.

Figure 28.

Dr. W. W. Shortal.

Dr. Harold M. Doolittle. In the Baylor University Bulletin announcements for 1916–1917, Dr. Harold M. Doolittle (Figure 29) is listed as professor of surgery along with Dr. Hackler and Dr. Rosser (53). Dr. Doolittle had become an associate professor of clinical surgery in 1911. He was born in Elyria, Ohio, on August 27,1877. He graduated from the University of Michigan Department of Medicine and Surgery in Ann Arbor in 1902. Dr. Doolittle served an internship at Northern Pacific Railroad Hospital in Brainerd, Minnesota. He was one of the first fellows of surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester from 1904 to 1905. Dr. Doolittle came to Dallas in 1905 and was first associated with Dr. C. M. Rosser. Later he practiced independently and in 1915 joined Dr. R. W. Baird in a partnership that later developed into the Dallas Medical Surgical Clinic. He was chief of the surgical staff and chairman of the board of the Dallas Medical and Surgical Clinic from its founding to the time of his death (54). Dr. Doolittle married Leda Stimson in 1907. He was a fellow of the American College of Surgeons and a founding member and president of the Texas Surgical Society. He resigned from the staff in 1935 due to health conditions. He became an honorary fellow of the Texas Surgical Society in 1938. Dr. Doolittle, a member of the Episcopal Church, died in Dallas on February 22, 1950, after a brief illness (55).

Figure 29.

Dr. Harold M. Doolittle.

Dr. A. B. Small. In the catalog for 1916–1917 and announcements dated May 1917, Dr. A. B. Small (Figure 30) is listed as clinical professor of surgery. He was born on July 15, 1863, in Collinsville, Alabama, and educated at the Memphis Hospital Medical College in 1888. He moved to Dallas in 1895. He was clinical professor of surgery until 1935 and was the father of Andrew B. Small, Jr., who became assistant clinical professor of surgery in 1943. He served as chairman of the section on surgery of the Texas State Medical Association in 1926 and again in 1932. He was also vice president of the Texas State Medical Association. Dr. Small married Marie Watson of Waxahachie in 1900 (56). His grandson, Dr. Andrew B. Small III, did his residency at BUMC and is on the staff there. Dr. Andrew Small Ill's son, the fourth generation of the Small family, was a radiology resident at BUMC. Dr. Small was a founding member and also president of the Texas Surgical Society in 1926. He died suddenly on November 29, 1934, at age 71 years in Dallas.

Figure 30.

Dr. A. B. Small.

Early minutes of the hospital board of trustees (1904–1950)

Dr. Harold Cheek and Simira Meymand reviewed the minutes of the hospital board of trustees dating from October 1904 (57). These minutes were brief and mostly written in longhand. The staff of the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium comprised 23 physicians, including Drs. E. H. Cary, J. M. Pace, and Charles M. Rosser; Pierre Wilson was president. In March 1910 rules and regulations were established for the development of an intern program that would consist of 6 months on the medical service and 6 months on the surgery service. Dr. W. W. Shortal was the first intern selected. In June 1910 there is evidence that medical services were organized to include a medical, surgical, and gynecological service. The following year, it was noted that 4 interns had been selected for the coming year.

In January 1912 the sanitarium hospital board created a medical staff chosen from the faculty of Baylor University College of Medicine. It would constitute the executive medical committee and shows Dr. Charles M. Rosser in surgery, who was likely the first chief of surgery at Baylor University College of Medicine. Dr. E. H. Cary was dean and head of ophthalmology and otolaryngology. Dr. Harold M. Doolittle was appointed head of operative and clinical surgery, and Dr. Elbert Dunlap head of gynecology. By November 1912, additional executive committee members included Drs. G. M. Hackler, C. M. Grigsby, H. L. Moore, C. R. Hanna, J. H. Dean, W. M. Peck, J. M. Martin, J. H. Martin, and S. L. Turner.

In February 1915 Dr. E. H. Cary, as spokesman for the staff, encouraged the board of trustees to organize the staff into 3 categories: 1) executive senior physicians and surgeons; 2) executive junior physicians and surgeons; and 3) honorary physicians and surgeons. This structure is similar to today's organization of associate attending and attending staff. On May 10, 1918, the staff recommended raising the hospital standards to conform to the minimal standards of the American College of Surgeons and to request that the board create a declaration opposing fee splitting (58). On June 18, 1927, the board of trustees formed divisions to include medicine, surgery, and obstetrics.

On October 5, 1927, Dr. Ozro T. Woods admitted patients through the dispensary to be used for the purpose of teaching. By January 23, 1928, the minutes note that 9 interns from the senior class were selected for the coming year. Dr. Rosser resigned on December 20, 1928. Dr. Doolittle resigned from the faculty on October 23, 1935. Dr. Charles W. Flynn became chairman of surgery in April 1936.

BAYLOR UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL AND BAYLOR UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MEDICINE, 1920–1960

Consolidation of the sanitarium and medical school under the Baylor name (1920)

On November 12, 1920, formal approval was granted to combine the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium and the college of medicine by the Baptist General Convention of Texas in a meeting in El Paso. That consolidation placed the college of medicine, the dental school, and the nursing school under the board of trustees of Baylor University. The Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium was renamed Baylor Hospital on January 21,1921, and property, including Ramseur Hall and the sanitarium, passed to Baylor University in Waco (43).

Support of the medical school by Baylor University at Waco (1920)

In June 1920 at the 75th anniversary celebration of Baylor University, the executive committee of the board of directors of the Baptist General Convention of Texas passed a resolution stating that Baylor University would receive a sum equal to 5% of an endowment of $ 1 million payable annually to the trustees of Baylor University College of Medicine (59).

Departmentalization and reorganization (1920)

By 1920 the hospital had 400 beds and 7 operating rooms (60). A chairman was appointed to each medical school department, thus more clearly defining departments. There were only 8 full-time faculty members. It was specified that the position of dean should be filled by someone not in private practice. Because of this, Dr. Cary resigned as dean and became dean emeritus and chairman of the advisory committee as well as continuing his faculty responsibilities as professor of ophthalmology and otolaryngology. Dr. W. H. Moursund, professor of pathology, who had recently come back from the military service, was appointed acting dean (59) (Figure 31).

Figure 31.

Dr. Walter H. Moursund, dean of Baylor University College of Medicine.

In 1921, Dr. Mclver Woody, formally dean and chief of the surgical division at the University of Tennessee School of Medicine, was named dean of the medical school and professor of surgery (61). Dr. Woody had received his bachelor's degree from Harvard and his medical degree from Harvard in 1912. He had interned at Boston City Hospital in 1913–1914 and was a teaching fellow at Harvard from 1914 to 1919. However, after 1 year, Dr. Woody resigned the deanship and the professorship of surgery, and Dr. Moursund was again made acting dean and then permanent dean in 1923 (62).

Purchase of the Stephen F. Austin School (East Dallas City Hall) (1922)

In Dallas in 1920, the first paved highway was Beltline Road. In 1922 the Magnolia Building, with the flying red horse, opened. The same year, insulin was first used to treat diabetes. In that year Baylor Hospital bought from the board of education of the city of Dallas the Stephen F. Austin school building at the corner of Gaston Avenue and Hall Street for $40,000 (63). Built in 1886, the Stephen F. Austin building had formerly been City Hall of East Dallas and later had become one of the public grade schools (Figure 32). For several years Dr. Cary had advocated the purchase of this property, but there had been opposition by the neighbors. The black servants were leaving the area in droves, explaining that they did not want to work close to a place where “young boys cut up dead men.” In 1925 the medical college was housed in two buildings, Ramseur Hall and Cary Hall (Old City Hall). Cary Hall would be used by the medical college until 1943, when the school moved to Houston.

Figure 32.

Cary Hall, which had been the City Hall of East Dallas and an elementary school before being purchased by the medical college.

Beginning with the 1923 session, each student paid a hospital fee of $3 to cover expenses of hospitalization of the students for a period of up to 1 week. The operating room fee for the students was covered only when an operation was a distinct emergency (64). The 23rd session closed on June 12, 1923, with 17 graduates.

Medical Arts Building (1923)

In 1923, Dr. Cary, one of the wealthiest physicians in Dallas, opened his magnificent 19-story Medical Arts Building on Pacific Avenue in downtown Dallas (65). He opened a small hospital on 2 floors of the building with operating rooms for otolaryngology, dental, and abdominal surgery. The building received national publicity, but locally it signified a deep internal rift at Baylor, one destined to fester for more than 20 years and eventually lead to the removal of the medical college to Houston. The building was eventually torn down in 1977 because of difficulty with parking and downtown traffic; it had been outdone by newer and more modern buildings in more convenient locations.

Dr. Cary, chief of surgery (1925–1929)

Dr. E. H. Cary, former dean, became head of the Department of Surgery in 1925 and remained so until 1929 (66). In 1929 Dr. Cary was elected president of the Dallas County Medical Society, the Texas Medical Association, and the Southern Medical Association.

Faculty unrest—a second Flexner Report (1925)

Citizens of Dallas began talking in the late 1920s about making Dallas a great medical center. The men who were dreaming of making Dallas a great medical center, in time, thought their dream could not become a reality unless all denominational attachments of the scientific institutions were severed. Great foundations such as the Carnegie and Rockefeller Foundations were largely responsible for this thought. The board of trustees brought in Dr. J. F. Kimball as vice president of Baylor University in 1929, and he gave wise and constructed supervision to all the Baylor units in Dallas for 10 years. He had previously served as superintendent of Dallas Public Schools. Brice Twitty was also brought in; he was a man of great knowledge in the fields of public relations and finance. The doctors wanted departmentalization, and the trustees attempted to accommodate them.

The Flexner book on medical education was published in 1925 (67). Dallas physicians realized that medical education in Dallas was not what it should be. The board of trustees was sympathetic but did not want to put Baylor in debt. The physicians became impatient and felt that the leadership was inadequate. They felt the need to separate scientific institutions from denominations. Two reports were submitted to the board of trustees within 3 months of each other. The first was from Dean Moursund, Dr. Henry M. Winans, and Dr. W. W. Looney, dated December 20, 1928. The 8 page report from the faculty outlined the dissatisfaction and the lack of support for the medical college, the nursing service, and the nursing school. Dr. Moursund stated that it was “a wind that would blow into a storm.” The second report was dated March 6, 1929, and was submitted to the trustees and president of Baylor University. It proposed the new administrative structure for all units of Baylor in Dallas. It urged that the new clinic of the City Health Department be aligned with Baylor Hospital and that a baby hospital funded by Mr. Bradford, the Cancer and Pellagra Hospital, and the Psychopathic Hospital, which had been audiorized by the state legislature, all be located on the Baylor campus. The report was signed by Dr. E. H. Cary, chief of surgery; Dr. A. I. Folsom, who would follow as chief of surgery later in 1929; and Dr. C. C. Hannah (67). The board of trustees was reluctant to undertake too many large projects because of the financial risk. The Great Depression was coming. Although steps were taken, they were not enough to satisfy the physicians (68).

Stock market crash (1929)

Initially after World War I, there had been an economic boom, but this was quickly followed by a severe economic downturn in 1923, leaving the Texas Baptists saddled with huge debts. By November 1928 the hospital was in debt $261,330 (69, 70). On October 24, 1929, came Wall Street's infamous “Black Thursday,” and the stock market crashed. The Great Depression engulfed America. By 1933, 2294 banks had closed and 15 million Americans were unemployed.

Approval of the Baylor Plan by the American College of Surgeons (1929)

In December 1929 the Baylor Plan of prepaid hospital insurance was formed (the forerunner of Blue Cross/Blue Shield). As the Great Depression wore on, patients had more difficulty paying hospital bills, which had increased in cost. One afternoon in late 1929, Vice President Kimball, who was in charge of the Dallas unit, and Superintendent Twitty discussed the crisis in Mr. Kimball's office. Dr. Kimball suggested that people be allowed to pay a small amount each month toward future care. Dr. Kimball proposed that each teacher in the Dallas School District pay 50¢ per month or $ 1.50 per family into the treasury of his or her school. By December they had enrolled 1356 patients.

The first patient to receive hospital benefits under the Baylor Plan was Alma Dickson, who slipped on icy pavement in December 1929 and fractured her ankle. She spent Christmas Day in the hospital. Following hospitalization, she found her hospital bill paid in full by the plan. There had been considerable resistance to the new idea until one of the employees from the Dallas Morning News developed appendicitis. Her hospital bill was paid in full by the plan, and this so impressed the others that the rest of the Dallas Morning News employees enrolled. National recognition spread rapidly.

The American College of Surgeons became the first important national medical body to approve the Baylor Plan. It was ultimately endorsed by the American Hospital Association and eventually became known as Blue Cross. In 1946, the Blue Cross Plan was supplemented by the Blue Shield Plan, which provided insurance for the payment of doctor bills. By 1977, more than 90 million Americans were covered by Blue Cross. In the lobby of BUMC's Truett Hospital is a bronze plaque inscribed “to Baylor University Hospital, Dallas, Texas, the birthplace of the Blue Cross Program of prepaid hospital insurance” (70).

Events of the 1930s

In the 1931–1932 session at Baylor University College of Medicine, there were 256 medical students with 120 freshman, and 67 graduated on May 3,1932. The Baylor School of Pharmacy had to close in 1931 due to insufficient funds and lack of support by Baylor University in Waco (71).

During the 1930s, several events are noteworthy. In 1934, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, notorious bank robbers from Dallas, were killed in Arcadia, Louisiana. The Dionne quintuplets were born in Calendar, Ontario. The Empire State Building opened in 1935, and Al Capone was convicted of income tax evasion. The Hindenburg airship exploded in Lake Hurst, New Jersey (1937). Charles Lindbergh's son was kidnapped. Sulfa, “the wonder drug,” was marketed. The first Cotton Bowl game was played, and Bugs Bunny, the cartoon character, was originated. In 1935 Fort Knox was established. Congress passed Social Security, and Huey “Kingfish” Long was shot to death by a physician, Dr. Carl A. Weiss. The flying red horse was placed on the Magnolia Building in Dallas (1934).

Florence Nightingale Hospital and Baylor University Hospital (1937)

The Florence Nightingale Hospital, on the corner of Gaston Avenue and Adair Street, was completed in the summer of 1937 and was connected by underground corridors with Baylor Hospital. The hospital was made possible by a gift from Mr. and Mrs. Edwy Rolfe Brown of Dallas (72, 73). With the opening of the Florence Nightingale Hospital on May 12,1937, officials of Baylor Dallas used the term “Baylor University Hospitals” for what may have been the first time. As early as 1932, officials had added the word “university” in references to Baylor Hospital, but the name was not formally changed to Baylor University Hospital until July 16, 1937, when a new 50-year charter was issued to Baylor University and the hospital name change became official (73).

In 1938, Dr. Joseph M. Hill, a native of Buffalo, New York, began the development of a machine called “ADTEVAC” (adsorption temperature controlled vacuum) that could dry blood plasma. The blood plasma was changed to powder form that did not require refrigeration and could be mixed with a dissolving liquid immediately prior to its use in transfusion to form instant blood plasma. Due to widespread interest in the product, Baylor received a $13,000 grant in December 1939 from Dr. and Mrs. Stanley Seeger, a Milwaukee couple who had recently moved to Dallas. The donation was in memory of the late William Buchanan, Mrs. Seeger's father and a multimillionaire Texarkana lumber dealer and oilman. Dr. Seeger's daughter, Hannah Davis, and her husband, Wirt Davis, and family would subsequently make many significant endowments to the Department of Surgery (71).

Southwestern Medical Foundation (1939)

In 1938 Baylor University College of Medicine had many problems. The tuition paid could not resolve the basic problem that had always plagued the school: a lack of money. The school had no endowment, no support from a major financial foundation or granting agency, and no significant monetary assistance from its own parent, Baylor University. There was little research in the school, and instruction was basically limited to lectures. The physical plant was inadequate, and Baylor's position as a class A institution was again in jeopardy.

On January 21, 1939, with the support of several leading figures within the community, Dr. Cary obtained a charter for the Southwestern Medical Foundation. E. R. Brown, who had helped fund the Florence Nightingale Hospital; Karl Hoblitzelle, a business entrepreneur and interstate theater owner; and Dr. Hall Shannon were the incorporators for the nonprofit corporation with no capital stock. The foundation added Herbert Marcus, Jesse S. Jones of Houston, R. C. Fulbright of Houston, and T O. Walton, president of Texas A&M College at Bryan, Texas, to the board of trustees. The foundation's charter gave it the right to own and operate a medical school (74). A formal dinner sponsored by the foundation was held on January 23, 1939, at the Adolphus Hotel, and the formation and purpose of the foundation were announced. The members noted that a medical school located in Dallas would belong to the entire Southwest and would be strictly nonsectarian (75). It was estimated that from $5 million to $25 million would be needed from private sources. The foundation appointed a committee, including Dr. E. H. Cary, for the purpose of raising $5 million to support medical research at Baylor University College of Medicine. Dr. Allen Gregg, director of medical science for the Rockefeller Foundation, was the principal speaker. The endowment failed to materialize because within a few months the world was focusing on World War II prospects in Europe. With the opening of the 40th session of the medical school in October 1939, the admission requirements were increased to a minimum of 3 years of college credit.

Baylor surgeons in the 56th Evacuation Unit (1940)

In August 1940, Baylor University College of Medicine received a telegram from US Surgeon General James C. Magee asking that the college organize a medical unit for the army. The unit was to be designated the 56th Evaluation Hospital, and it would be composed almost entirely of hospital staff and medical school faculty and alumni just as its predecessor, Hospital Unit V, had been 22 years earlier in World War I. Included in the organization of the 56th Evacuation Hospital were several surgeons, including Majors Andrew D. Small, Charles D. Bussey, and James Hudson Dunlap, who were founding members of the Dallas Society of General Surgeons, and Captain Robert). Rowe, a colon and rectal surgeon (76).

Hitler had taken over France, and London was being bombed. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had Congress approve the first peace-time draft in American history. The USA and Britain were moving closer to a military alliance (77). Shortly before 8:00 AM on Sunday morning, December 7, 1941, hundreds of Japanese planes attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbor and the Hawaiian islands without warning. The attack left 2330 Americans dead and another 1145 wounded. The next day President Roosevelt called for a declaration of war against Japan, and that request was approved in congress by a vote of 470 to 1. Three days later, Japan, Germany, and Italy declared war on the USA (78).

Several important surgeons came to Dallas in the 1930s and 1940s. Many were first in their specialty:

Dr. Walter Sistrunk, 1930

Dr. Oscar Marchman, 1931

Dr. Albert P. D'Errico, 1932, neurosurgery

Dr. James T Mills, 1935, plastic surgery

Dr. J. Warner Duckett, 1936, pediatric surgery

Dr. John Vivian Goode, 1938, general surgery

Dr. William Lee Hudson, 1938, general surgery

Dr. Hudson Dunlap, 1942, general surgery

Dr. Jack Carr, 1942, colon and rectal surgery

Dr. Frank Selecman, 1942, general surgery

Establishment of the Southwestern Medical College (1942)

In early 1942, the Southwestern Medical Foundation became active towards reaching an agreement with Baylor University for joint operation of Baylor University College of Medicine. Dr. Cary, former chief of surgery, ultimately put the college of medicine and the foundation on a collision course. It had been announced on March 8, 1942, by Southwestern Medical Foundation's president, Dr. E. H. Cary of Dallas, and reported in the Dallas Morning News on March 12, 1942, that plans for a great medical center on a 35-acre tract on Harry Hines Boulevard, including the Parkland Hospital grounds, had been made. The new medical school was to be named Southwestern Medical College.