Over the past several years, increased attention has been given to the risks associated with medication use, especially within hospitals. The Institute of Medicine's 2000 report, To Err is Human (1), continues to stir an avalanche of interest from the government and the private and public sectors. This increasing scrutiny has emerged as regulators, payers, and patients have demanded not just incremental improvement in safety but giant steps toward medical perfection. This article addresses what has been accomplished, where we may be headed, and what is left undone.

LOW-HANGING FRUIT

Early efforts to improve medication safety within hospitals focused on rather obvious and easily corrected system problems that frequently caused significant patient harm. Concentrated electrolyte solutions have been removed from nursing medication preparation areas, where they might be inadvertently given to patients and cause disastrous consequences. Easily misidentified and similarly labeled products were often kept together on the shelf, a potentially confusing and dangerous circumstance! By removing these products from patient care areas and preparing them in the pharmacy with careful labeling, this type of error has become far less frequent in American hospitals. However, over time it has become more difficult to find gross examples of easily corrected safety issues, and subsequent efforts to improve medication safety have been far more difficult.

These worthwhile changes have rapidly progressed from being common-sense suggestions to strong mandates of the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), as summarized in its 2004 National Patient Safety Goals (2). As of January 2004, organizations failing to implement any of the listed goals will not receive full accreditation.

A CULTURE CHANGE

Early efforts in the area of patient safety sought to change medical culture so that errors and mishaps were more openly acknowledged and disseminated. A “culture of blame” had tended to suppress the reporting of errors and mistakes, making it more difficult to develop improvement strategies. Instead, emphasis has been shifted away from personal blame and suggestions of professional incompetence to a focus on “system” problems that permitted, set up, or facilitated a professional error. This has increased voluntary reporting of medication errors and the development of multidisciplinary teams that review these reports, which at times conduct a “root cause analysis” to improve safety.

Unfortunately, two powerful detriments to a more open culture persist—medical malpractice litigation and state licensing board review. Although hospital committee activity that seeks to improve quality is legislatively “protected” from discovery by plaintiffs, there remains considerable hesitancy to allow information regarding errors to flow beyond a small group of leaders. Additionally, reports of medical errors may be filed in the employment records of the involved individuals, impacting future licensure of hospital privileges. An attitude of protecting the institution could potentially override the needs of patients and families. To counter this emphasis, hospitals are strongly encouraged to include nonmedical, nonhospital members from the community on their patient safety committees and hospital boards.

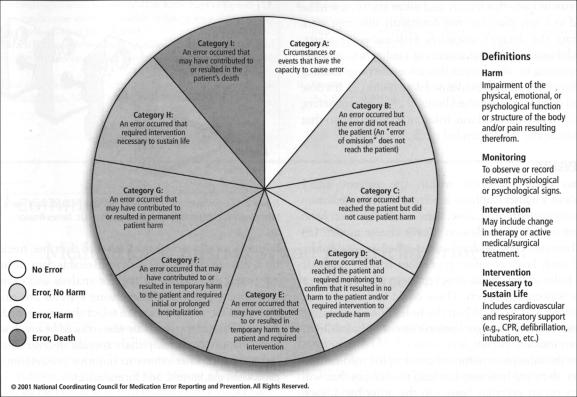

Hospitals within Baylor Health Care System (BHCS) use common definitions of medication errors, based on the severity of the effect on the patient's well-being. These definitions are adopted directly from those published by the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention, an independent body comprising 25 national and international organizations (Figure 1). The council's general definition of a medication error is as follows:

Figure 1.

Index of the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention for categorizing medication errors.

A medication error is any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient, or consumer. Such events may be related to professional practice, health care products, procedures, and systems, including prescribing; order communication; product labeling, packaging, and nomenclature; compounding; dispensing; distribution; administration; education; monitoring; and use (3).

A web-based reporting tool has been developed at BHCS that includes features not often found in other systems. When they file a report, users can select from a menu of likely “contributing causes.” These causes include prescription problems, computer system problems, problems with the use of intravenous pumps, and lack of drug information. By sending reports that indicate a selected group of errors with similar underlying causes to a small team capable of impacting a part of the medication administration system, significant changes can be rapidly implemented, directly impacting patient safety. For example, a set of errors related to the computer system revealed medication ordering screens that were confusing, ambiguous, or inaccurate. These screens have been corrected, preventing similar errors. In this way, voluntary reporting of medication errors has allowed those directly involved in patient care to have substantial impact on safety.

“LET ME COUNT THE WAYS”

It is important that we measure the safety of our systems, as it is said, “You manage what you measure.” There has been a trend in health care toward measuring “outcomes” and pushing for “evidence-based medicine.” How else can it be said that a hospital is improving the safety of its care over time? Unfortunately, measuring medication safety continues to be a major obstacle. Definitions surrounding medication safety are fraught with difficulty. The terms medication error, adverse drug event, side effect, and adverse drug reaction are confusing and misunderstood (4). Is a medication dose that is delayed an hour while a patient is away from his room for a procedure an “error”?

Voluntary reports remain the mainstay of discovery, even though all acknowledge that these reports reveal only a very small fraction of occurrences. By what mechanisms can more events be discovered? In recent years, attempts at using computerized “trigger tools” have been employed with varying success (5). Computerized systems look for key triggers that might indicate that an adverse drug event has occurred. For example, administration of a benzodiazepine reversal agent might imply that a sedative has been used unsafely. This approach is being explored with some success. The types of discoverable events that might be associated with an adverse drug event include certain laboratory results (low serum potassium, a positive stool test for Clostridium difficile toxin), ordering of certain medications (diphenhydramine, naloxone), or an unexpected change in a patient's condition (transfer to the intensive care unit, fall). Using computerized trigger tools is certainly much less labor intensive than manually reviewing charts or searching through discharge diagnostic codes, older methods still more commonly used.

USING EXPERT SYSTEMS

Increasing success is being achieved by using automated, rule-based detection systems to alert prescribers and pharmacists of potential hazards when the relevant data are received in clinical computer systems (6). In these scenarios, an order for a medication is automatically compared with specific existing laboratory data, vital signs, allergy information, and other data in the patient's chart. Sophisticated rules and algorithms have been developed that alert the verifying pharmacist when potentially hazardous conditions exist. For example, when low-molecular-weight heparin is prescribed, the computer system uses the patient's age, weight, gender, and most recent serum creatinine to estimate renal function. This information is compared with the new prescription to ensure that the heparin dose is within an appropriate range. Warning alerts are displayed and directed to the most appropriate professional.

In a slightly different scenario, when new laboratory results are obtained, the patient's medication profile is automatically examined for potential conflicts. This type of screening for potentially hazardous medication orders ideally occurs when an order is written, allowing the prescriber to get it right at the outset without depending on downstream professionals or systems to intercept the order. The best computerized physician order entry systems have this feature and allow the review to be accomplished in a way that does not constantly interrupt work flow or saturate the doctor's attention with excessive alerts, warnings, and directives. Manufacturers of medication infusion pumps are beginning to offer devices that allow the programming of drug infusion protocols with predefined dose limits (7). If a dose is programmed outside of established limits or clinical parameters, the pumps halt or provide an alarm, informing the clinician that the dose is outside the recommended range.

ANALYZING EVENTS

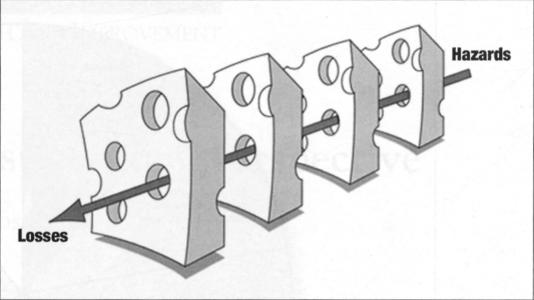

There has been discussion within the patient safety community about whether emphasis is better placed on medication variances (wrong patient, drug, dose, time, or route) or on harm to patients (outcomes). James Reason's “swiss cheese model” (8) (Figure 2) illustrates how mishaps occur when several safety nets fail and each layer of safety procedure is not rigorously applied. The holes in the cheese slice represent a latent error or system failure waiting to happen. These could be human error, equipment failure, and so on. When the holes line up, meaning all the defenses fail and an organization's latent vulnerabilities are exposed, an incident occurs.

Figure 2.

The “swiss cheese model” shows how hazards may reach a patient when safety nets fail. Reprinted with permission of Dr. James Reason.

Because of the infrequent nature of catastrophic medication-related events, their analysis may not lead to changes that will improve safety on an everyday basis. On the other hand, each step in the medication administration system is easily measured, monitored, and analyzed.

APPROACHES TO IMPROVING SAFETY

Inaccurate transcription of medical orders occurs frequently, and this can flow downstream, injuring patients. An order for Celebrex, a cyclooxgenase-2 inhibitor used for arthritis, might be entered as Cerebryx, an antiepileptic drug, with vastly different consequences to the patient. At BHCS, programs to reduce transcription errors have included the following:

Prescriber ordering and legibility audits—periodic reviews of prescriber compliance with medical staff regulations and JCAHO guidelines regarding the use of abbreviations, legibility, and prescriber identification

Pharmacist order entry—entry and verification of medication orders by decentralized pharmacists at the point of care, alongside other members of the care team

Computerized physician order entry

Order document scanning—transmittal of an electronically scanned image to the central pharmacy, where it remains available for retrospective review

Another frequently occurring error occurs at the bedside, when what is administered is not what was ordered for that patient. All the policies, procedures, and built-in safety features can be powerless to prevent this type of error, which very obviously can have disastrous consequences. Computerized barcoding systems have emerged that can vastly reduce this type of error. Armbands on all patients have specific identifying barcode labels. Each medication order is also barcoded, as is each dose of every medication. At the time of administration, the computer reconciles all three, and if the patient, the medication, and the order are all correct, the nurse is given the “green light” to give the medication. Additionally, a record of the dose being given is automatically recorded, along with the time, freeing the nurse from this tedious clerical activity. Reliable data are automatically generated that can be helpful for analysis and examination. In addition, sophisticated dispensing systems are employed that make it difficult for a nurse to select the wrong medication for a patient. Prescribing errors are also reduced by involving the entire care team in multidisciplinary rounds, decentralized pharmacy services, and other efforts to improve prescribing (care paths, protocols, guidelines, and formularies).

SUMMARY

Improving patient safety in hospitals has been at the forefront of national interest, in some ways even surpassing discussions of medical financing. Dramatic cases are highly publicized by the media, adding public pressure for safety but also damaging the reputations of our most highly regarded health care institutions. This interest and emphasis has led hospitals to reexamine their approaches to safety and allocate increased resources toward this laudable goal. Technology not only has added immensely to the complexity of care but has been a powerful tool for ensuring safety in the medication administration system, with approaches ranging from computerized physician order entry and barcode labeling and administration systems to automated medication and dose checking. BHCS has made a substantial commitment to integraling this technology throughout its facilities. Technology should present enormous opportunities to improve prescribing, make care more efficient, and enhance patient safety. Nonetheless, no computerized system can be more than a helpful advisor to the dedicated and knowledgeable professionals working together, in an open and constructive environment, to provide the best possible care for their patients.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to Michael Sanborn and Valerie Sheehan for their valuable contributions to the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. National patient safety goals. Available at http://www.jcaho.org/accredited+organizations/patient+safety/; accessed July 20, 2004.

- 3.National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention. About medication errors. Available at http://www.nccmerp.org/aboutMedErrors.html; accessed July 20,2004.

- 4.Nebeker Jr, Barach P, Samore MH. Clarifying adverse drug events: a clinician's guide to terminology, documentation, and reporting. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:795–801. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-10-200405180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.VHA, Inc. Monitoring Adverse Drug Events: Finding the Needles in the Haystack. Vol. 9. Irving, TX: VHA; 2002. VHA 2002 Research Series. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galanter WL, Di Domenico RJ. Analysis of medication safety alerts for inpatient digoxin use with computerized physician order entry. Available at http://www.cerner.com/products/products_4a.asp?id=273; accessed July 7,2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Malashock M, Shull S, Gould D. Hospital Pharmacy. Vol. 39. 2004. Effect of smart infusion pumps on medication errors related to infusion device programming; pp. 460–469. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reason JT. Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing; 1997. [Google Scholar]