Abstract

Mechanochemical coupling reactions are typically single-site events that are thermally driven, require an inert atmosphere, and are kinetically slow under ball milling conditions. Here, we demonstrate the rapid 4-fold single-pot mechanochemical C–N coupling of tetrabromopyrene and phenothiazine leading to a novel pyrene-phenothiazine (PYR–PTZ) molecule that is shown to be an effective hole-transport material (HTM) in a perovskite solar cell (PSC). When compared to previously reported mechanochemical C–N coupling reactions, the mechanosynthesis of PYR–PTZ is achieved in just 99 min of ball-milling under ambient conditions without a glovebox or the need for external heating. This represents an advance over previous methods for the synthesis of HTMs and opens new avenues for exploring the discovery of other organic HTMs for PSC applications. The photophysics, crystal structure, and electron transport properties of the novel HTM have been characterized using a combination of experimental and density functional theory methods. In an encapsulated PSC, the photoconversion efficiency of PYR–PTZ is comparable to that of the widely used spiro-MeOTAD molecule, but the stability of PYR–PTZ is superior in a naked PSC after 4 weeks. This work demonstrates the value of mechanochemistry in the sustainable synthesis of new organic HTMs at significantly reduced costs, opening up new opportunities for mechanochemistry in optoelectronics.

Short abstract

This work reports the mechanosynthesis, photophysics, and application of a novel organic pyrene-phenothiazine (PYR–PTZ) hole transport material in perovskite solar cells (PSCs). PYR–PTZ exhibits superior stability and comparable photoconversion efficiency when used as a hole-transport layer in perovskite solar cells when compared to the commonly used spiro-MeOTAD molecule.

Introduction

Hybrid organic–inorganic perovskite solar cells (PSCs) have attracted significant attention due to their unique physical properties and potential applications in photovoltaics (PVs). The photoconversion efficiency (PCE) of PSCs has reached up to 25.7%,1 comparable to inorganic PVs, such as CdTe and copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS) but with the advantage of PSCs having low temperatures and printing compatibility. A PSC consists of a conductive substrate, electron transporting layer (ETL), perovskite layer, hole transport layer (HTL), and back electrode (Au).2 In this configuration, light absorption, generation of charges, and transport of electrons and holes enable the conversion of light to electricity. Although a high PCE is necessary for an efficient device, the sustainable application of PSCs requires a cost-effective and environmentally sustainable method for the sourcing, synthesis, and application of the various components of the device at scale. Currently, the most expensive component of PSCs is the hole-transport material (HTM). The prohibitive cost of commonly used HTMs arise as a consequence of the multistep solution synthesis required, leading to significant material costs with each step, and by extension, posing challenges to the environment as the bulk solvent and waste produced must be disposed of. Spiro-MeOTAD (2,2′,7,7′-tetrakis(N,N-di(p-methoxyphenyl amine))-9,9′-spirobifluorene) represents one of the earliest proposed HTMs for PSCs and continues to be widely used within the PV community.3 The synthesis of spiro-MeOTAD (Scheme 1a) is typically done in solution and requires both high temperatures and inert conditions. Moreover, the costs associated with using spiro-MeOTAD pose a significant challenge to the scalable production and practical application of PSCs.4−7 There are a number of previously reported HTMs (Table S1) that comprise either a pyrene (PYR) or a phenothiazine (PTZ) moiety, indicating the potential of these chemical fragments for use in PSCs. Unfortunately, all these HTMs are synthesized using multistep solution methods that use large volumes of bulk solvent, providing significant opportunities to develop greener synthetic methods for targeting HTMs.

Scheme 1. Chemical Reactions for: (a) Solution Synthesis of 2,2′,7,7′-Tetrakis[N,N-di(4-methoxyphenyl)amino]-9,9′-spirobifluorene (spiro-MeOTAD); (b) the Four-Fold Single-Pot Mechanochemical C–N Coupling of Tetrabromopyrene and Phenothiazine Leading to PYR–PTZ that Proceeds without Any External Heating and under Ambient Conditions as Reported in This Work.

LAG = Liquid-assisted grinding.

Mechanochemistry8−10 is an attractive alternative to the solution synthesis of HTMs because the reaction environment uses minimal or no solvent at all. IUPAC recently recognized mechanochemistry as one of the top 10 emerging technologies that have the potential to positively impact society.11 The mechanochemical approach is especially beneficial for preparing complex organic molecules with high purity, which are critical for efficient charge transport and stability in PSCs.12,13 Beyond HTMs, mechanochemistry has significant potential for synthesizing other PSC components, such as electron transport materials, additives for perovskite layers, and interface modifiers.14,15 It can facilitate the incorporation of dopants or functional groups into these materials, enabling precise property tuning.16 Moreover, the robust and energy-efficient nature of mechanochemistry makes it suitable for producing a wide range of materials including organic molecules,17 inorganic complexes,18 and halide perovskites.19 For example, Borchardt has demonstrated the utility of mechanochemistry in carrying out Suzuki20 and Sonogashira21 coupling reactions. Furthermore, Stuparu has shown that mechanochemistry can be used to synthesize curved polycyclic aromatics.22 In the present work, we demonstrate that by leveraging mechanochemical tools, it is possible to advance the sustainable synthesis of HTMs for use in PSCs.

A previous work by Kubota et al.23 has shown that mechanochemical C–N coupling reactions are viable methods for the synthesis of organic optoelectronic materials, but the yields of the reactions disclosed were shown to be temperature dependent with the greatest yields afforded when an external heater was used during the ball milling reaction. A similar strategy was employed by Browne24 and Geneste25 in carrying out the mechanochemical Buchwald–Hartwig amination of aryl halides using secondary amines. Subsequent work by Leitch and Browne26 has shown that mechanochemical C–C coupling reactions are also temperature sensitive. While these efforts suggest that mechanochemical coupling reactions are in general achievable, there are few reports of 4-fold single-pot mechanochemical C–N coupling reactions that are performed under ambient conditions. The current work demonstrates the viability of 4-fold single-pot mechanochemical C–N coupling reactions, leading to a novel pyrene-phenothiazine (PYR–PTZ) HTM. The mechanosynthesis of PYR–PTZ was achieved without any external heating, a Schlenk line, or a glovebox. This solvent-free mechanosynthesis strategy for accessing functional HTMs is accompanied by purification via crystallization, which eliminates the need for solvent-demanding column chromatography, further reducing the environmental impact and cost of the HTM synthesis.

The functionality of the synthesized HTM is demonstrated by the integration of PYR–PTZ in a PSC. The PCE of PYR–PTZ is compared with spiro-MeOTAD. The measured PCE for PYR–PTZ is 10.83 ± 1.62%, while spiro-MeOTAD yields a marginally higher PCE of just 14.09 ± 1.11%, indicating a competitive result for the first-time PSC assembled using PYR–PTZ. From a broader perspective, this work paves the way for the mechanosynthesis of other functional HTMs for applications in solar cells, X-ray detectors, and image-sensing devices.2

Results and Discussion

Mechanosynthesis and Photophysical Properties of PYR–PTZ

The PYR–PTZ molecule is synthesized via the Pd-catalyzed mechanochemical C–N coupling of 1,3,6,8-tetrabromopyrene and phenothiazine using milling vessels and balls made of stainless-steel (Scheme 1b). The precursor 1,3,6,8-tetrabromopyrene is obtained via the bromination of pyrene using a literature procedure.27 The palladium acetate is used as a catalyst, and sodium tert-butoxide acts as a base. The tri-tert-butylphosphonium tetrafluoroborate acts as the air-stable source of tri-tert-butyl-phosphine ligand and the N,N-di-isopropylethylamine (DIPEA) acts as a base that releases tri-tert-butyl-phosphine.28 These air-stable reagents enable the reaction (Scheme 1b) without cumbersome inert conditions that require a Schlenk line or glovebox setup. 1,5-Cyclooctadiene (COD) is used as a liquid-assisted grinding solvent, which also prevents the aggregation of the Pd catalyst, resulting in higher catalytic efficiency.29,30 The reaction conditions were optimized for the size and number of milling balls (Table 1).

Table 1. Reaction Optimization Conditions for the Mechanosynthesis of PYR–PTZ.

| entry no | number of balls | size of balls (mm) | grinding time | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 7 | 7 Hrs | 30 |

| 2 | 8 | 4 | 7 Hrs | 13 |

| 3 | 16 | 4 | 7 Hrs | 37 |

| 4 | 24 | 4 | 7 Hrs | 37 |

| 5 | 24 | 4 | 99 min | 17 |

| 6 | 34 | 4 | 99 min | 44 |

The reaction gave a 30% yield with two balls of 7 mm diameter. Initially, with a decrease in the size of the balls to 4 mm and increasing the number of balls to eight, we observed a decrease in the yield to 13%. However, using 4 mm diameter balls with varying numbers from 16 to 24, the yields were improved and the reaction time was decreased. Further increasing the number of balls to 34 gave a satisfactory yield of 44% in just 99 min. Following the completion of the reaction and filtration through a short silica bed, the product was purified by crystallization and washing with a small amount of solvent, thus eliminating the need for an extensive amount of solvent needed for chromatographic purification. The successful synthesis of the target PYR–PTZ molecule was confirmed via single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Figures S1 and S2), 1H and 13C NMR (Figures S3 and S4), and high-resolution mass spectrometry (Figure S5). There are several reports of the synthesis of HTMs,31 but this is the first report of a Pd-catalyzed solid-state mechanosynthesis of a HTM that has a demonstrated application as a component in a PSC. This methodology can be used to synthesize other HTMs more economically by changing the amine ligands used in the mechanochemical C–N coupling reaction.

Crystals of PYR–PTZ suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction were grown via the slow diffusion of toluene (TOL) into a dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) solution of PYR–PTZ. The PYR–PTZ molecule exhibits a bright orange color. The PYR–PTZ molecule crystallizes in the triclinic P1̅ space group (Table S2) with two-half molecules of PYR–PTZ in the asymmetric unit (Figure 1a). The crystal packing of PYR–PTZ is distinctly different from that displayed by the constituent PYR and PTZ molecules, as illustrated by the simulated powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns of these materials (Figure 1b). The single-crystal structure reveals strong π–π stacking between the aromatic rings of phenothiazine across the symmetry inequivalent fragments (Figure S2).

Figure 1.

(a) ORTEP diagram from the single-crystal X-ray structure of PYR–PTZ; (b) overlay of the simulated PXRD patterns of pyrene, phenothiazine, and PYR–PTZ; (c) normalized UV/vis spectra of 15 μM PYR–PTZ in toluene, dichloromethane, and chloroform, and (d) emission spectra of 15 μM PYR–PTZ tetrad in toluene, dichloromethane, and chloroform. Excitation wavelength 359 nm for TOL and CHCl3 and 358 nm for CH2Cl2.

The UV–vis absorption spectra of PYR–PTZ in TOL, chloroform (CHCl3), and CH2Cl2 are shown in Figure 1c. The PYR–PTZ molecule exhibits vibronic absorption bands at 325, 342, and 359 nm corresponding to the PYR moiety. The absorption bands are red-shifted compared to the parent PYR scaffold due to the increased electron delocalization from the PTZ to the PYR. PYR–PTZ exhibits a molar attenuation coefficient of 55,004 M–1·cm–1 in TOL (Figure S6). Solvent polarity does not significantly influence the PYR–PTZ absorption and excitation properties, as illustrated by absorptions at 359.2 nm (TOL), 358 nm (CH2Cl2), and 358.8 nm (CHCl3) (Figure 1c). The emission spectra are recorded by exciting at the respective absorption maximum in the respective solvents (Figure 1d). The emission spectra reveal weak emission bands at 380–420 nm range corresponding to localized emission. In addition, the major, broad emission band is observed at 600 nm in TOL, which shows a red shift with increasing solvent polarity from 622 nm in CHCl3 to 658 nm in CH2Cl2. The bathochromic shift of emission maxima with solvent polarity indicates the charge transfer from PTZ to the PYR moiety.

Computed Hole Transport Properties of PYR–PTZ

To contrast the electronic properties of PYR–PTZ with those of spiro-MeOTAD, time-dependent density functional theory calculations were performed at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory. The frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs) of PYR–PTZ (Figure S7) show that in the HOMO, most of the electron density is localized on the PTZ fragments coupled to the PYR core. The dominant contributor to the LUMO is the PYR molecule, illustrating the electrophilic character of the PYR core and hence the significant charge separation between the PTZ moieties and the PYR core. The band gap energy is 2.70 eV in PYR–PTZ. The FMOs of spiro-MeOTAD (Figure S8) illustrate an improved orbital overlap in the HOMO and a higher band gap energy of 3.59 eV. The overall band alignment diagram (Figure 2a) for both HTMs shows a competitive ability to extract the photogenerated holes from the perovskite layer.

Figure 2.

(a) Energy band diagram of the PSC stack consisting of TiO2 as the ETL and spiro-MeOTAD or PYR–PTZ as the HTM. (b) Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) of the PYR–PTZ molecule.

The molecular electrostatic potential (Figure 2b) of the PYR–PTZ molecule is consistent with that of the FMOs and shows significant charge separation between the PTZ moieties and the PYR core, with most of the electron density localized on the PTZ moieties. In order to gain deeper insights into the hole-transfer (HT) properties of PYR–PTZ and spiro-MeOTAD, DFT calculations were performed in order to estimate the coupling integrals, a fundamental parameter governing hole mobility within the framework of classical Marcus theory.32 An analysis of the HT within PYR–PTZ revealed a maximum coupling integral of 45 meV between its HOMO–1 orbitals along the c-axis. This value is marginally better than the 42 meV coupling integral estimated between adjacent spiro-MeOTAD molecules along the a-axis, suggesting competitive HT properties between PYR–PTZ and spiro-MeOTAD. Both spiro-MeOTAD and PYR–PTZ exhibit significant variations in HT properties as a function of the crystallographic direction (Figures S9 and S10).

Performance of PYR–PTZ in PSCs

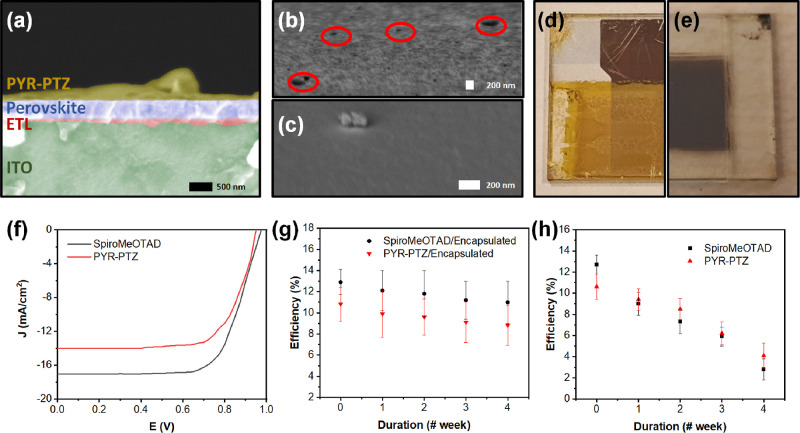

PSCs were fabricated using a standard n-i-p architecture of indium tin oxide (ITO)/ETL/absorbing layer (perovskite)/HTL/Au. Two types of PSCs with spiro-MeOTAD (control) and PYR–PTZ (test sample) were prepared, in both encapsulated and nonencapsulated forms. Both spiro-MeOTAD and PYR–PTZ were used with estimated thicknesses of between 150–200 nm. The cross-section and surface morphology of the PSCs were measured via SEM (Figure 3a). Unlike spiro-MeOTAD (Figure 3b), PYR–PTZ showed uniform morphology without pinhole defects (Figure 3c). Spiro-MeOTAD is known for its surface roughness even after treatment with antisolvents (Figure 3b), such as diethyl ether (see the Experimental section). Surface roughness is expected to influence the stability and performance of the PSC.33,34

Figure 3.

SEM images of (a) cross-section of the cell stacks with PYR–PTZ with each layer labeled, (b) top view of the spiro-MeOTAD, and (c) PYR–PTZ; Utilized PSCs together with the corresponding macro images of (d) naked and (e) encapsulated cell stacks used for the measurements after 4 weeks duration. Surface defects present in spiro-MeOTAD HTL are indicated with red in (b); (f) J–V curve of the encapsulated PSCs measured right after assembly. The highest efficiency values were achieved from the cell stacks with a PCE of 14.09% for the spiro-MeOTAD utilized cell and 10.83% for PYR–PTZ utilized cells; measured efficiency values of the (g) encapsulated and (h) naked PSC stacks containing spiro-MeOTAD and PYR–PTZ as the HTL materials.

The J–V curve measurement of device performance with the reverse scan is used to calculate the PCE values of the cell stacks. J–V measurements for two types of PSCs, (i) naked PSC and (ii) encapsulated PSC, have been performed for the devices as fabricated and at 4 weeks after fabrication (Figure 3d,e). For simplicity, J–V from encapsulated spiro-MeOTAD and PYR–PTZ are provided in Figure 3f. The short circuit current density (Jsc) values are shown in Table S3 for all cell configurations. A representative J–V plot (forward and reverse scan) for spiro-MeOTAD and PYR–PTZ is shown in Figure S11. First, we discuss the encapsulated cell structures (Table S3). The PSC containing spiro-MeOTAD yielded a Jsc of 17.05 mA/cm2, an open circuit voltage (Voc) of 0.98 V, a fill factor (FF) of 77.55 ± 1.41%, and a corresponding PCE of 14.09 ± 1.11%. This value decreases to a Jsc of 15.82 mA/cm2, Voc of 0.95 V, FF of 75.89 ± 1.78%, and a corresponding PCE of 12.46 ± 1.54% after 4 weeks (Figure 3g). For PYR–PTZ, a Jsc of 14.32 mA/cm2, Voc of 0.95 V, and FF of 72.86 ± 1.36% corresponding to a PCE of 10.83 ± 1.62%, exhibited at the beginning for encapsulated cell stacks. The measured performance values after 4 weeks’ duration are Jsc of 12.26 mA/cm2, Voc of 0.94 V, and FF of 70.1 ± 1.63%, corresponding to a PCE of 8.83 ± 1.73% (Figure 3g). From these results, PSCs that have PYR–PTZ as the HTM, have a competitive PCE, especially when compared to the widely used spiro-MeOTAD HTM.

For the nonencapsulated cells, spiro-MeOTAD yielded a Jsc of 17.20 mA/cm2, Voc of 0.98 V, and FF of 74.64 ± 1.85%, and a corresponding PCE of 13.80 ± 1.37% as the starting performance (Figure 3h), which decreased to a Jsc of 7.95 mA/cm2, Voc of 0.72 V, and FF of 44.33 ± 1.39%, and a corresponding PCE of 2.82% ± 1.52% after 4 weeks (Figure 3h). For the PYR–PTZ PSC, a similar trend is observed with a Jsc of 14.28 mA/cm2, Voc of 0.95 V, and FF of 71.63 ± 1.69%, and a corresponding PCE of 10.61 ± 1.24% in the beginning (Figure 3h). Then, it decreased to a Jsc of 11.56 mA/cm2, Voc of 0.70 V, and FF of 46.33 ± 1.84%, and a corresponding PCE of 4.09 ± 1.37%. As depicted in the average cell performance values (n = 3) given in Figure 3h, there is a dramatic decrease in the cell performance for both control and test cells, which indicates degradation of the perovskite layer beneath the HTL due to exposure to an open atmosphere. However, it should be noted that PYR–PTZ HTL might give better protection of the perovskite layer, due to its hydrophobic character and excellent layer thickness uniformity, than spiro-MeOTAD. This could be the reason for a lower PCE value for spiro-MeOTAD than for PYR–PTZ at week 4.

The degradation observed in Figure 3h is typical for organic–inorganic perovskites such as methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3). MAPbI3 has a hygroscopic character, and as a result, the material degrades quickly in an ambient environment.35 Upon exposure to water vapor, a monohydrate (CH3NH3PbI3·H2O) is formed in the MAPbI3 layer. As a result, Jsc is reduced dramatically. Furthermore, the formation of hydrates in the perovskite layer might also cause lateral cell expansions in the absorber layer, which translates into the deterioration of the ETL/perovskite and HTL/perovskite interfaces. Such deteriorations cause trap sites to form at the interface,36 which increases the recombination of photogenerated charge carriers and decreases the Voc and overall cell performance (Table S3).37

In summary, measurements conducted on the novel PYR–PTZ material show that it acts as a functional HTM within the n-i-p cell configuration. The attained performance values of PYR–PTZ are comparable to those of the benchmark spiro-MeOTAD HTM. The Voc values of devices containing PYR–PTZ and spiro-MeOTAD are comparable. This may be explained by the deep HOMO levels of both HTMs, providing high photoconversion efficiencies during the operation of the PSC.7,38,39

Conclusions

This work reports the 4-fold mechanochemical C–N coupling of tetrabromopyrene and phenothiazine under ambient conditions, leading to a novel PYR–PTZ molecule. The synthetic methodology utilizes air-stable reagents to conduct the C–N coupling without the need for a Schlenk line or a glovebox. Our mechanochemical synthetic methodology offers a minimal solvent route and purification by crystallization, eliminating the extensive solvent-demanding column chromatography in the synthesis of most HTMs. This lowers the environmental impact and costs of the HTM synthesis. PYR–PTZ functionality is demonstrated as an HTL when used in PSCs. The measured PCE for PYR–PTZ was 10.83 ± 1.62%, while for spiro-MeOTAD, the PCE was 14.09 ± 1.11% in encapsulated PSC structures. This indicates a competitive result in the use of PYR–PTZ in the PSCs. Nonencapsulated PYR–PTZ-based PSC led to slightly higher PCE values (4.09 ± 1.37%) when compared to spiro-MeOTAD-based cells (2.82 ± 1.52%) after 4 weeks. This observation is likely due to the more homogeneous and defect-free surface protecting the MAPbI3. From a general perspective, PYR–PTZ can be used as an HTL in PSCs due to its sustainable and low-cost mechanochemical synthesis coupled with its good stability and respectable PCE.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of Khalifa University of Science and Technology under the Research and Innovation Grant (award no. RIG-2023-054). This publication is based on work supported by Khalifa University of Science and Technology under the Center for Catalysis and Separations. This research was also supported by ASPIRE, the technology program management pillar of Abu Dhabi’s Advanced Technology Research Council (ATRC), via an ASPIRE Award for Research Excellence (Project Code: AARE20-259). The theoretical calculations were performed using the high-performance computing clusters of Khalifa University. The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the research computing department of Khalifa University. C.E., J.W., A.S.A., and H.G. would like to thank Mark Smithers (MESA + Institute, University of Twente) for their support. The research leading to the results in this report has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 742004).

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data is given in the manuscript or provided in the Supporting Information document.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.cgd.4c01523.

Materials and methods used, reference literature data on the hole-transport properties of comparable materials, crystallographic data, NMR data, high-resolution mass spectra, absorption spectra of the PYR–PTZ HTM, computational data, experimental photoconversion efficiencies, and J–V curves in the forward and reverse scans (PDF)

Author Contributions

C.E. and J.W. performed the perovskite solar cell assembly and hole transport layer electrical characterization, formal UV–vis and NMR analysis and wrote the initial draft of the discussion for the experimental work performed at the University of Twente. C.E. and J.W. were also involved in reviewing and editing subsequent drafts of the manuscript. W.A.A., Z.Y. and T.A. performed DFT calculations, interpretation of the computational results and contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. H.H.H. provided access to the mechanochemical milling instrument used to synthesize PYR–PTZ, engaged in data analysis and contributed to the conceptualization and editing of the manuscript. L.L. and P.B.M performed the crystallographic work, assisted S.M. with interpretation and solution of the crystal structure and contributed to drafting the manuscript. D.S. collected NMR and HRMS data and contributed to the drafting and review of the manuscript. H.G. and A.S.A supervised C.E. and J.W. with the experimental work performed at the University of Twente and contributed to writing, reviewing and editing the manuscript. B.D. and S.M. conceived the study together and supervised the work of W.A.A, T.A. and Z.Y. B.D. performed the mechanosynthesis, analytical characterization and interpretation of the analytical data. B.D. and S.M. put together the first draft of the manuscript and oversaw the completion of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Sharma R.; Sharma A.; Agarwal S.; Dhaka M. S. Stability and efficiency issues, solutions and advancements in perovskite solar cells: A review. Sol. Energy 2022, 244, 516–535. 10.1016/j.solener.2022.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jena A. K.; Kulkarni A.; Miyasaka T. Perovskite Photovoltaics: Background, Status, and Future Prospects. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 3036–3103. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rombach F. M.; Haque S. A.; Macdonald T. J. Lessons learned from spiro-OMeTAD and PTAA in perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 5161–5190. 10.1039/D1EE02095A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petrus M. L.; Bein T.; Dingemans T. J.; Docampo P. A low cost azomethine-based hole transporting material for perovskite photovoltaics. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 12159–12162. 10.1039/C5TA03046C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vivo P.; Salunke J. K.; Priimagi A. Hole-Transporting Materials for Printable Perovskite Solar Cells. Materials 2017, 10, 1087. 10.3390/ma10091087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangala S.; Misra R. Spiro-linked organic small molecules as hole-transport materials for perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 18750–18765. 10.1039/C8TA08503J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.; Yuan F.; Zhou D.; Liao X.; Chen L.; Chen Y. Hole transport layers for organic solar cells: recent progress and prospects. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 11478–11492. 10.1039/D0TA03511D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed Z. M.; Dhokale B.; Shunnar A. F.; Awad W. M.; Hernandez H. H.; Naumov P.; Mohamed S. Crystal Engineering of Binary Organic Eutectics: Significant Improvement in the Physicochemical Properties of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons via the Computational and Mechanochemical Discovery of Composite Materials. Cryst. Growth Des. 2021, 21, 4151–4161. 10.1021/acs.cgd.1c00420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ng Z. X.; Tan D.; Teo W. L.; León F.; Shi X.; Sim Y.; Li Y.; Ganguly R.; Zhao Y.; Mohamed S.; García F. Mechanosynthesis of Higher-Order Cocrystals: Tuning Order, Functionality and Size in Cocrystal Design. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 17481–17490. 10.1002/anie.202101248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shunnar A. F.; Dhokale B.; Karothu D. P.; Bowskill D. H.; Sugden I. J.; Hernandez H. H.; Naumov P.; Mohamed S. Efficient Screening for Ternary Molecular Ionic Cocrystals Using a Complementary Mechanosynthesis and Computational Structure Prediction Approach. Chem.—A Eur. J. 2020, 26, 4752–4765. 10.1002/chem.201904672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomollón-Bel F. Chemical Innovations That Will Change Our World: IUPAC identifies emerging technologies in Chemistry with potential to make our planet more sustainable. Chem. Int. 2019, 41, 12–17. 10.1515/ci-2019-0203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynes J. F.; Leon F.; García F. Mechanochemistry for Organic and Inorganic Synthesis. ACS Org. Inorg. Au 2024, 4, 432–470. 10.1021/acsorginorgau.4c00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Espejo G.; Rodríguez-Padrón D.; Luque R.; Camacho L.; de Miguel G. Mechanochemical synthesis of three double perovskites: Cs2AgBiBr6, (CH3NH3)2TlBiBr6 and Cs2AgSbBr6. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 16650–16657. 10.1039/C9NR06092H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynes J. F.; Isoni V.; García F. Tinkering with Mechanochemical Tools for Scale Up. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202300819 10.1002/anie.202300819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan D.; García F. Main group mechanochemistry: from curiosity to established protocols. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 2274–2292. 10.1039/C7CS00813A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochowicz D.; Saski M.; Yadav P.; Grätzel M.; Lewiński J. Mechanoperovskites for Photovoltaic Applications: Preparation, Characterization, and Device Fabrication. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 3233–3243. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friščić T.; Mottillo C.; Titi H. M. Mechanochemistry for Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 1018–1029. 10.1002/anie.201906755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auvray T.; Friščić T. Shaking Things from the Ground-Up: A Systematic Overview of the Mechanochemistry of Hard and High-Melting Inorganic Materials. Molecules 2023, 28, 897. 10.3390/molecules28020897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazon F.; El Ajjouri Y.; Sebastia-Luna P.; Lauciello S.; Manna L.; Bolink H. J. Mechanochemical synthesis of inorganic halide perovskites: evolution of phase-purity, morphology, and photoluminescence. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 11406–11410. 10.1039/C9TC03778K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt C. G.; Grätz S.; Lukin S.; Halasz I.; Etter M.; Evans J. D.; Borchardt L. Direct Mechanocatalysis: Palladium as Milling Media and Catalyst in the Mechanochemical Suzuki Polymerization. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 18942–18947. 10.1002/anie.201911356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickhardt W.; Siegfried E.; Fabig S.; Rappen M. F.; Etter M.; Wohlgemuth M.; Grätz S.; Borchardt L. The Sonogashira Coupling on Palladium Milling Balls—A new Reaction Pathway in Mechanochemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202301490 10.1002/anie.202301490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Báti G.; Laxmi S.; Stuparu M. C. Mechanochemical Synthesis of Corannulene: Scalable and Efficient Preparation of A Curved Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon under Ball Milling Conditions. ChemSusChem 2023, 16 (20), e202301087. 10.1002/cssc.202301087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota K.; Endo T.; Uesugi M.; Hayashi Y.; Ito H. Solid-State C–N Cross-Coupling Reactions with Carbazoles as Nitrogen Nucleophiles Using Mechanochemistry. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202102132 10.1002/cssc.202102132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Q.; Nicholson W. I.; Jones A. C.; Browne D. L. Robust Buchwald–Hartwig amination enabled by ball-milling. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 1722–1726. 10.1039/C8OB01781F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemesre Q.; Wiesner T.; Wiechert R.; Rodrigo E.; Triebel S.; Geneste H. Parallel mechanochemical optimization – Buchwald–Hartwig C–N coupling as a test case. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 5502–5507. 10.1039/D2GC01460B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt R. R. A.; Raby-Buck S. E.; Ingram K.; Leitch J. A.; Browne D. L. Temperature-Controlled Mechanochemistry for the Nickel-Catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura-Type Coupling of Aryl Sulfamates via Ball Milling and Twin-Screw Extrusion. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202210508 10.1002/anie.202210508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt S.; Kastler M.; Enkelmann V.; Baumgarten M.; Müllen K. Pyrene as Chromophore and Electrophore: Encapsulation in a Rigid Polyphenylene Shell. Chem.—Eur. J. 2006, 12, 6117–6128. 10.1002/chem.200500999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netherton M. R.; Fu G. C. Simple, Practical, and Versatile Replacements for Air-Sensitive Trialkylphosphines. Applications in Stoichiometric and Catalytic Processes. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 4295–4298. 10.1021/ol016971g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota K.; Takahashi R.; Uesugi M.; Ito H. A Glove-Box- and Schlenk-Line-Free Protocol for Solid-State C–N Cross-Coupling Reactions Using Mechanochemistry. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 16577–16582. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c05834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota K.; Seo T.; Koide K.; Hasegawa Y.; Ito H. Olefin-accelerated solid-state C–N cross-coupling reactions using mechanochemistry. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 111. 10.1038/s41467-018-08017-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashaei B.; Bellani S.; Shahroosvand H.; Bonaccorso F. Molecularly engineered hole-transport material for low-cost perovskite solar cells. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 2429–2439. 10.1039/C9SC05694G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R. A. Chemical and electrochemical electron-transfer theory. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1964, 15, 155–196. 10.1146/annurev.pc.15.100164.001103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.-G.; Kim J.-H.; Ramming P.; Zhong Y.; Schötz K.; Kwon S. J.; Huettner S.; Panzer F.; Park N.-G. How antisolvent miscibility affects perovskite film wrinkling and photovoltaic properties. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1554. 10.1038/s41467-021-21803-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y.; Yang L.; Wang F.; Sui Y.; Sun Y.; Wei M.; Cao J.; Liu H. Anti-solvent surface engineering via diethyl ether to enhance the photovoltaic conversion efficiency of perovskite solar cells to 18.76%. Superlattices Microstruct. 2018, 113, 761–768. 10.1016/j.spmi.2017.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J.; Tan S.; Lund P. D.; Zhou H. Impact of H2O on organic–inorganic hybrid perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 2284–2311. 10.1039/C7EE01674C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leguy A. M. A.; Hu Y.; Campoy-Quiles M.; Alonso M. I.; Weber O. J.; Azarhoosh P.; van Schilfgaarde M.; Weller M. T.; Bein T.; Nelson J.; Docampo P.; Barnes P. R. F. Reversible Hydration of CH3NH3PbI3 in Films, Single Crystals, and Solar Cells. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 3397–3407. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b00660. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherkar T. S.; Momblona C.; Gil-Escrig L.; Ávila J.; Sessolo M.; Bolink H. J.; Koster L. J. A. Recombination in Perovskite Solar Cells: Significance of Grain Boundaries, Interface Traps, and Defect Ions. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 1214–1222. 10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitchaiya S.; Natarajan M.; Santhanam A.; Asokan V.; Yuvapragasam A.; Madurai Ramakrishnan V.; Palanisamy S. E.; Sundaram S.; Velauthapillai D. A review on the classification of organic/inorganic/carbonaceous hole transporting materials for perovskite solar cell application. Arabian J. Chem. 2020, 13, 2526–2557. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2018.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X.; Song Z.; Li Z.; Tang W. Toward ideal hole transport materials: Areview on recent progress in dopant-free hole transport materials for fabricating efficient and stable perovskite solar cell. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 4057–4086. 10.1039/D0EE02337J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data is given in the manuscript or provided in the Supporting Information document.