Abstract

Recently, we disclosed VU0467319, an M1 positive allosteric modulator (PAM) clinical candidate that had successfully completed a phase I single ascending dose clinical trial. Pharmacokinetic assessment revealed that, in humans upon increasing dose, a circulating, inactive metabolite constituted a major portion of the total drug-related area under the curve (AUC). One approach the team employed to reduce inactive metabolite formation in the back-up program was the kinetic isotope effect, replacing the metabolically labile C–H bonds with shorter, more stable C–D bonds. The C–D dipole afforded VU6045422, a more potent M1 PAM (human EC50 = 192 nM, 80% ACh Max) than its proteocongener VU0467319 (human EC50 = 492 nM, 71% ACh Max), and retained the desired profile of minimal M1 agonism. Overall, the profile of VU6045422 supported advancement, as did greater in vitro metabolic stability in both microsomes and hepatocytes than did VU0467319. In both rat and dog in vivo, low doses proved to mirror the in vitro profile; however, at higher doses in 14-day exploratory toxicology studies, the amount of the same undesired metabolite derived from VU6045422 was equivalent to that produced from VU0467319. This unexpected IVIVC result, coupled with less than dose-proportional increases in exposure and no improvement in solubility, led to discontinuation of VU0467319/VU6045422 development.

Keywords: muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtype 1 (M1), positive allosteric modulator (PAM), deuterium, cognition, metabolism, isotope

Introduction

In the 1980s, numerous pharmaceutical companies demonstrated that “M1 agonists” exhibited robust efficacy in improving cognition in Alzheimer’s patients.1−6 However, the lack of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor selectivity among the five subtypes (M1–5) led to the concomitant activation of peripheral M2 and M3 receptors and contributed to significant clinically relevant cholinergic adverse events known by the acronym SLUDGE (salivation, lacrimation, urination, defecation, gastrointestinal distress, and emesis).1−6 Thus, developing drugs that selectively activate M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors has been a goal since that time. The advent of recombinant functional G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) assays made high-throughput screening for highly subtype-selective positive allosteric modulators for the M1 receptor possible.7−20 We disclosed 1, VU0467319, an M1 positive allosteric modulator (PAM) clinical candidate that was chemically optimized from hits derived from an HTS campaign. VU0467319 has a profile of moderate M1 PAM potency and minimal M1 agonism and successfully completed a phase I SAD clinical trial (Figure 1).21 While observed preclinically in both microsome and hepatocyte preparations, as well as in preclinical species in vivo, in humans, the circulating, inactive metabolite 2 (VU0481424) constituted a majority (>50%) of the total drug-related area under the curve (AUC) upon increasing dose.22−24 As this would not only require the need for regulatory metabolite monitoring but also result in a significant loss of an active, circulating parent, the development of 1 was terminated and effort was made to identify a back-up M1 PAM with improved pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles.

Figure 1.

Structures of VU0467319 1, and the corresponding oxidative metabolite 2, as well as the dideutero congener 3 (VU6030095) and the penta-deutero analogue 5 (VU6045422), with the putative oxidative metabolites 4 and 6, respectively.

Since M1 PAM 1 had the desired pharmacological profile, the team attempted numerous strategies to sterically and electronically address the metabolic “hot spot”; however, all attempts eroded M1 PAM potency significantly. As a final effort to salvage the chemotype, we elected to install a gem-dideutero moiety at the metabolic hot spot and explore if the kinetic isotope effect, with shorter, stronger C–D, would mitigate oxidative metabolism.25,26 This exercise led to the development of dideutero 3 (VU6030095), and a key question surrounded whether it would prove to be more stable and generate less of the analogous oxidative metabolite 4 (VU6031240). As progress began, an analytical standard was required that would be 3 atomic mass units (amu) different from 3, and that request led to the production of the penta-deutero congener 5 (VU6045422) due to ease of incorporation of a 5 amu standard. We then characterized the pharmacological profile and metabolic stability of 5 and its propensity to produce putative oxidative metabolite 6 (VU6045587). Here, we detail the unexpected molecular pharmacology of these deuteron congeners as well as their disparate in vitro and in vivo DMPK profiles, highlighting that deuterium incorporation is not always a panacea to endow metabolic stability.

Results and Discussion

Design

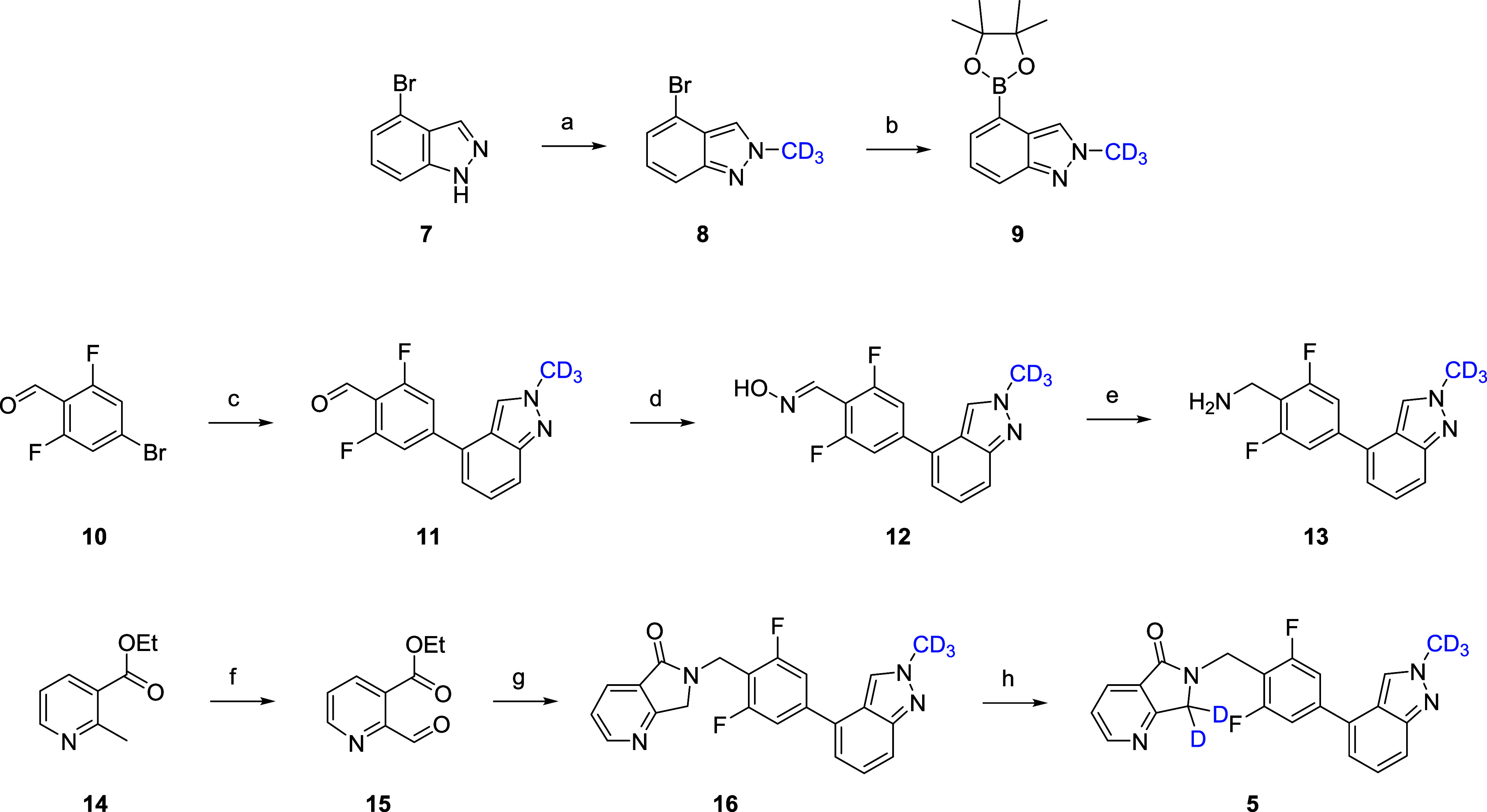

As alluded to previously, attempts to block undesired oxidative metabolism at the benzylic lactam center, employing either steric or electronic strategies, were unsuccessful, resulting in a complete loss of the M1 PAM potency. Thus, we evaluated the impact of deuterium incorporation at the metabolic hot spot to assess if the shorter, stronger C–D bond would yield improved stability (i.e., the kinetic isotope effect).25,26 To access the desired gem-dideutero derivative, a concise strategy was developed (Scheme 1), wherein 1 was treated with NaOD in D2O to cleanly afford 3 (VU6030095) in 70% yield with high isotopic purity. Due to the stage of the program, a request was made to produce an analytical standard 3 amu different from 3, which led to the more complex, convergent synthesis (Scheme 2) of 5 (VU6045422) harboring not only the gem-dideutero moiety of 3, but an additional N-CD3 on the indazole. Starting from commercial bromo indazole 7, alkylation with CD3I affords the N-CD3 indazole 8 in 33% yield. Conversion of 8 into pinacol borate under standard conditions provides the Suzuki coupling partner 9 in 72% yield. Commercial aldehyde 10 participates in a Suzuki coupling reaction with 9 to afford biaryl aldehyde 11 in 96% yield. The requisite benzyl amine 13 is accessed in two high yielding streps by the conversion of aldehyde 11 to oxime 12, followed by Zn-catalyzed reduction. Pyridine 14 undergoes benzylic oxidation with SeO2 to deliver aldehyde 14, which then undergoes a reductive amination/cyclization sequence to give lactam 16 in high yield. As for 3, exposure of 16 to NaOD in D2O cleanly afforded 5 (VU6045422) in 73% yield and high isotopic purity. Thus, the team had the necessary new ligands 3 and 5 to assess metabolic stability as well as M1 PAM activity; however, we also needed to synthesize known metabolite 2, as well as the putative metabolites 4 and 6 to provide analytical standards for quantification in vitro and in vivo.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of VU6030095 (3).

Reagents and conditions: (a) NaOD (40 wt % in D2O), tetrahydrofuran (THF)/D2O, 35 °C, 70%.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of VU6045422 (5).

Reagents and conditions: (a) ICD3, Cs2CO3, MeCN, room temperature (rt), 33%; (b) bis-pinacolborane, PdCl2(dppf)·CH2Cl2, KOAc, 1,4-dioxane, 100 °C, 72%; (c) 9, PdCl2(dppf)·CH2Cl2, Cs2CO3, 1,4-dioxane/H2O, 100 °C, 96%; (d) NH2OH·HCl, NaOAc, EtOH, 98%; (e) Zn/HOAc, rt, 96%; (f) SeO2, 1,4-dioxane, molecular weight (mw), 120 °C, 68%; (g) 13, sodium triacetoxyborohydride (STAB), dichloroethane (DCE), 89%; (h) NaOD (40 wt % in D2O), THF/D2O, 45 °C, 73%.

The major metabolite 2 of 1 was made into a two-step sequence employing the key benzyl amine used to construct 1 (Scheme 3). Starting from commercial anhydride 17, treatment with functionalized benzyl amine provides phthalimide 18 in 90% yield. Chemoselective reduction with NaBH4 provides racemic metabolite 2 in a 24% isolated yield. In a similar fashion (Scheme 4), chemoselective reduction of 19 and 20 with NaBD4 in dichloromethane (DCM)/MeOD provides 4 and 6, respectively, in 30–35% isolated yields. Like 2, putative metabolites 4 and 6 were inactive as M1 PAMs.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of VU0481424 (2).

Reagents and conditions: (a) (2,6-difluoro-4-(2-methyl-2H-indazol-4-yl)phenyl)amine, Et3N, dimethylformamide (DMF)/MeCN, rt, 1 h, then 1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxide hexafluorophosphate (HATU), 90%; (b) NaBH4, DCM/MeOH, 24%.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of VU6031240 (4) and VU6045587 (6).

Reagents and conditions: (a) NaBD4, DCM/MeOD, 30–35%.

Hepatocyte Stability (In Vitro)

Prior to full characterization of deuterated analogues 3 and 5, they were incubated in rat, dog, monkey, and human hepatocytes, along with 1, to determine the amount of parent remaining, as well as the degree of undesired oxidative metabolites 2, 4, and 6 (Figure 2). For 1, metabolite 2 was generated between 23.7 and 34.9% across rat, dog, and humans and was the major species in monkey (74.3%). For the gem-dideutero congener 3, metabolic stability was improved in vitro. In humans, production of the corresponding oxidative metabolite 4 was reduced 50% (34.9–15.2%) and both rat (7.8%) and dog (5.5%) were low, while in monkey there was a similar reduction >50% (74.3–30.3%). Surprisingly, the penta-deutero derivative 5 demonstrated exceptional stability across species, affording low levels of the analogous metabolite 6 in rat (8.1%), dog (4.1%), monkey (21%) and humans (4.9%). Specifically, whereas 34.9% of 1 was metabolized to 2 in human hepatocytes, 6 displayed a >80% reduction in metabolite production (4.9%). Thus, in hepatocytes in vitro, the kinetic isotope effect engendered greater metabolic stability of the labile hot spot on the lactam. It remained to be seen if this effect would translate in vivo, but we first had to assess the impact of the deuterated analogues on molecular pharmacology, in vitro DMPK, standard low-dose in vivo DMPK and, if warranted, in vivo efficacy in a rat novel object recognition (NOR) behavioral assay.

Figure 2.

Multispecies hepatocyte metabolite identification of M1 PAMs 1, 3, and 5 and quantification of oxidative metabolites 2, 4, and 6, respectively. In vitro hepatocyte assays clearly indicated greater stability toward oxidative metabolism for the deuterated congeners.

Molecular Pharmacology and In Vitro DMPK

As we only introduced deuterium into the VU319/ACP-319 (1)21 core with 3 and 5, we anticipated comparable M1 PAM pharmacology (Table 1). Interestingly, the gem-dideutero 3 was less potent (human EC50 = 624 nM, 81%; rat EC50 = 361 nM, 85%) than 1 (human EC50 = 492 nM, 80%; rat EC50 = 213 nM, 79%), yet maintained the desired profile of minimal M1 agonism and selectivity versus M2–5 (>30 μM).21 The loss of M1 PAM potency could be the result of a C–D dipole that diminishes the receptor affinity. The addition of the N-CD3 moiety in 5 resulted in a more potent human M1 PAM (EC50 = 192 nM, 80%) and equipotent rat M1 PAM (EC50 = 249 nM, 82%), again with minimal M1 agonism and selectivity versus M2–5 (>30 μM). Perhaps in this case, the C–D dipole of the CD3 moiety engages the receptor more effectively. Interestingly, in hepatic microsomes, predicted hepatic clearance was significantly lower for the parent 1 across species than either deutero derivative 3 or 5, while the fraction unbound in plasma and brain was equivalent across the three M1 PAMs. CYP450 profiles were comparable for the three compounds, as were MDCK-MDR1 (P-gp) ER (1.3–1.8) with high Papp ((31–41) × 10–6 cm/s).

Table 1. Pharmacology and In Vitro DMPK Profiles of M1 PAMs 1, 3, and 5.

In Vitro Electrophysiology

We carried out electrophysiology studies in mouse native tissue layer V medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) to ensure that 5 did not induce long-term depression (LTD). While ago-PAMs induce substantial long-term depression that correlates with a lack of robust procognitive efficacy,14,16−21 PAM 5 demonstrated no significant changes in field excitatory post synaptic potentials (fEPSPs) recorded from layer V and evoked by electrical stimulation in layer II/III at 10 μM concentration (∼40× above the functional mouse EC50). Thus, PAM 5 maintains activity dependence of PFC function (Figure 3), and it is expected to display robust precognitive efficacy.

Figure 3.

M1 PAM 5 (VU6045422) did not induce a significant long-term depression of fEPSPs in the mouse layer 5 prefrontal cortex. (A) Normalized time course of the fEPSP slope during baseline, application of 10 μM VU6045422 and washout. (B) Bar graph summarizing the averaged fEPSP slope during the last 5 min of washout (gray bar in panel (A)) compared to the baseline period (ns, p > 0.05, two-tailed paired t test, n = 9).

In Vivo DMPK and Behavior

As a reference in rat, 1 displayed an attractive profile (CLp = 3 mL/min/kg, t1/2 = 3 h, Vss = 0.67 L/kg and with 80% F) and a robust in vitro/in vivo correlation (IVIVC, e.g., rat CLhep = 5.7 mL/min/kg).21 Moreover, 1 showed good central nervous system (CNS) distribution in rat (Kp = 0.64; Kp,uu = 0.91).21 The gem-dideutero congener 3 (Table 2) showed a very similar in vivo profile to 1 in rat (CLp = 5.5 mL/min/kg, t1/2 = 3 h, Vss = 1.4 L/kg and with 100% F), with a poor IVIVC (CLp = 5.5 mL/min/kg vs rat CLhep = 41.3 mL/min/kg), but good CNS exposure (Kp = 0.63; Kp,uu = 0.57). Once again, a poor IVIVC was noted for penta-deutero analogue 5, but the in vivo DMPK profile was excellent (CLp = 4.8 mL/min/kg, t1/2 = 3.6 h, Vss = 1.1 L/kg, 100% F, Kp = 1.1; Kp,uu = 1.5). Interestingly, there were significant disconnects between the stability noted for 3 and 5 in hepatic microsomes, hepatocytes, and in vivo. As 3 and 5 were comparable in disposition, but 3 was a weaker PAM, the team decided to compare in vivo efficacy of these two PAMs in a rat novel object recognition (NOR) assay (Figure 4) to validate the differential M1 PAM potency. While both M1 PAMs afforded a dose-dependent increase in NOR, 5 was more efficacious (minimum effective dose (MED) = 1 mg/kg) compared to 3 (MED = 10 mg/kg). The in vitro and in vivo potency of 5 elevated it as a potential candidate, and deeper profiling was initiated.

Table 2. In Vivo Pharmacokinetic Profiles of M1 PAMs 3 and 5.

| compound | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| parameter | rat (SD) | dog (beagle or mongrel) | NHP (cyno) | rat (SD) | dog (beagle or mongrel) | NHP (cyno) | rat (SD) | dog (beagle or mongrel) | NHP (cyno) |

| dose (mg/kg) iv/po | 1/3 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 1/10 | 1/10 | 1/5 | 1/5 | ||

| CLp (mL/min/kg) | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.3 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 2.6 | 4.0 | ||

| Vss (L/kg) | 0.67 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.1 | ||

| elimination t1/2 (h) | 3.0 | 7.5 | 4.3 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 10.0 | 4.6 | ||

| F (%) po | 93 | 100 | 59 | 100 | 100 | 85 | 64 | ||

| Kp | 0.77 | 0.63 | 1.1 | ||||||

| Kp,uu | 1.3 | 0.57 | 1.5 |

Figure 4.

Novel object recognition (NOR) test in rats with M1 PAMs 3 and 5. (A) PAM 3 dose-dependently enhanced the recognition memory in rats. Pretreatment with 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg of 3 (PO 0.5% Natrasol/0.015% Tween 80 in water) 2 h prior to exposure to identical objects significantly enhanced recognition memory assessed 24 h later. Minimum effective dose (MED) is 10 mg/kg. (B) PAM 5 dose-dependently enhanced recognition memory in rats. Pretreatment with 0.3, 1, and 3 mg/kg of 5 (PO 10% Tween 80 in water) 1 h prior to exposure to identical objects significantly enhanced recognition memory assessed 24 h later. Minimum effective dose (MED) is 1 mg/kg. N = 13–18/group of male Sprague-Dawley rats. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 Dunnett posthoc test.

As shown in Table 2, M1 PAM 5 possessed attractive pharmacokinetic properties in dog (CLp = 2.6 mL/min/kg, t1/2 = 10 h, Vss = 2.0 L/kg, 85% F) and Cynomolgus monkey (CLp = 4.0 mL/min/kg, t1/2 = 4.6 h, Vss = 1.1 L/kg, 64% F). Whereas 1 had a hERG manual patch clamp IC50 of 12 μM,21 PAM 5 had an improved hERG manual patch clamp potency (IC50) of 21 μM. In addition, 5 was negative in the bacterial mutagenicity mini-AMES assay (4-strain with and without S9), had no significant activity in a Eurofins lead profiling screen (evaluating potential for “off-target” binding) of 68 GPCRs, ion channels, and transporters (no activity >50%@10 μM except: 58%@10 μM at α2A and 59%@10 μM at rat imidazoline), and evidence only a trace (<0.1%) of conjugation in GSH trapping studies (rat, dog, cyno, and human microsomes). PAM 1 was solely metabolized by CYP 3A4;21 in contrast, other CYP isoforms contributed to metabolizing PAM 5 (3A4 (92.6%), 2D6 (1.6%), and 3A5 (5.8%)). Moreover, there were no time-dependent CYP inhibition or CYP induction liabilities identified; 5 had minimal bile salt export pump (BSEP) inhibition (IC50 = 42.3 μM). Finally, at a 100 mg/kg IP dose in mice, a minimal Racine score of 1 was noted for M1 PAM 5. In a rat oral dose escalation PK study, sublinear dose escalation using suspension-based formulations in vehicle was observed (3–30 mg/kg); while dose-related increases in exposure were seen, the 100 mg/kg cohort was not linear (Figure 5). Despite high exposures obtained in this study, no cholinergic signs or adverse events were noted.

Figure 5.

Rat oral dose escalation PK study at 3 (AUC last 8390 h·ng/mL; Cmax = 1250 ng/mL), 10 (AUC last 23,900 h·ng/mL; Cmax = 3380 ng/mL), 30 (AUC last 55,600 h·ng/mL; Cmax = 6020 ng/mL), and 100 mg/kg (AUC last 87,800 h·ng/mL; Cmax = 7850 ng/mL).

As disconnects were observed with metabolic stability in vitro (in microsomes and hepatocytes) and in vivo, we had to ensure that 5 differentiated from 1 and would not produce high levels of metabolite 6in vivo. To this end, we prepared a 200 g lot of PAM 5 and performed, in parallel, a dog maximum tolerated dose (MTD) with a pharmacokinetics study and a 14-day rat exploratory toxicology and toxicokinetic study, quantifying plasma Cmax and AUC for both parent 5 and metabolite 6. In the dog MTD (dosed at 30, 100, and 1000 mg/kg of PO), PAM 5 was well-tolerated, but at all three dose levels, significant levels of 6 were detected (17–23% of Cmax concentration and 18–21% of the AUC), far above what hepatocyte incubations predicted (Table 3). Moreover, while exposure increased with dose, it was nonlinear. Unfortunately, in the 14-day rat toxicology and toxicokinetic study (dosed at 300, 750, and 1500 mg/kg of PO using suspension-based formulations), even higher levels of 6 (Table 4) were detected at day 14 in terms of both Cmax (23–32%) and AUC (23–28%). At lower doses, exposure was nonlinear and exposure of 5 decreased, while the exposure of 6 increased (both Cmax and AUC) at the 1500 mg/kg dose. Based on these in vivo data sets, it was clear that 5 did not differentiate from 1 in terms of the amount of circulating oxidative metabolite 6, and the levels were likely to be higher in humans, requiring monitoring. The series was terminated based on (1) poor and less than dose-proportional increases in systemic exposure, (2) lack of a kinetic isotope effect to diminish production of 6 in dogs and rats, and (3) strong likelihood of even higher concentrations of 6 to be present in man.

Table 3. Dog MTD Study Concentrations of 5 and 6.

|

5 |

6 |

ratio |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dose, (mg/kg PO) | Cmax | AUC | Cmax | AUC | Cmax (%) | AUC (%) |

| 30 | 2400 | 34,858 | 455 | 6242 | 19 | 18 |

| 300 | 3620 | 67,985 | 818 | 14,120 | 23 | 21 |

| 1000 | 5560 | 103,306 | 972 | 19,158 | 17 | 19 |

Table 4. Rat 14-Day Toxicology Study Concentrations of 5 and 6 on Day 14.

|

5 |

6 |

ratio |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dose, (mg/kg PO) | Cmax | AUC | Cmax | AUC | Cmax (%) | AUC (%) |

| 300 | 22,200 | 321,000 | 6740 | 89,500 | 30 | 28 |

| 750 | 31,300 | 536,000 | 7340 | 125,000 | 23 | 23 |

| 1500 | 30,700 | 518,000 | 9890 | 143,000 | 32 | 28 |

Conclusions

A chemical optimization back-up program for VU0467319, an M1 PAM clinical candidate that successfully completed a phase I SAD clinical trial, is reported. In an attempt to diminish a circulating, inactive metabolite that constituted a significant portion of the AUC upon increasing dose in humans, we focused on C–D bioisosteres and application of the kinetic isotope effect. From this effort, a penta-deutero congener, VU6045422, was developed and evaluated. The C–D dipole afforded a more potent M1 PAM (human EC50 = 192 nM, 80% ACh Max) than its proteocongener VU0467319 (human EC50 = 492 nM, 71% ACh Max) and retained the desired profile of minimal M1 agonism. In 4 h multispecies hepatocyte incubations, VU6045422 was significantly more stable than VU0467319, but was found less stable in liver microsomes. Low dose in vivo PK mirrored the enhanced hepatocyte stability. In rat NOR, VU6045422 displayed an MED of 1 mg/kg PO and excellent multispecies IV/PO PK and high CNS penetration. However, in a dog MTD and pharmacokinetic study, as well as in a rat 14-day toxicology and toxicokinetics study at high doses, the amount of VU6045422 oxidative metabolism did not differentiate significantly from that of VU0467319, and higher levels were projected in humans. This unexpected IVIVC result, coupled with less than dose-proportional increases in exposure and no improvement in solubility, led to the cessation of VU6045422 development. This work highlights the challenges in C–D bioisosterism and identifies that the application of this strategy is not always a panacea. However, VU6045422 represents another exceptional M1 PAM tool compound, with minimal agonism, to study selective M1 activation in rodent models.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank William K. Warren, Jr. and the William K. Warren Foundation for support of their programs and endowing both the Warren Center for Neuroscience Drug Discovery and the William K. Warren, Jr., Chair in Medicine (C.W.L.).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PAM

positive allosteric modulator

- PBL

plasma/brain level

- DMPK

drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics

- AE

adverse event

- M1

muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtype 1

- MED

minimum effective dose

- NOR

novel object recognition

- IND

investigational new drug

- FDA

federal drug administration

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acschemneuro.5c00119.

Additional experimental details, methods for the synthesis and characterization of all compounds (1H NMR, 13C NMR, HRMS, LCMS), in vitro and in vivo DMPK protocols, and supporting figures (PDF)

Author Contributions

C.W.L., P.J.C., C.M.N., J.M.R., O.B., A.L.R., D.W.E., and H.P.C. oversaw the medicinal chemistry, target selection, and interpreted biological/DMPK data. C.W.L. wrote the manuscript. J.L.E., C.H., M.F.L., and A.R.G. performed chemical synthesis. H.P.C., A.L.R., and C.M.N. performed and analyzed in vitro pharmacology assays. P.M.D., C.O., and E.S.B. oversaw rat 14-day and dog MTD studies. Z.X. performed slice electrophysiology (LTD). J.W.D., W.P., and J.M.R. performed in vivo behavior pharmacology assays and in vivo DMPK. O.B. performed in vitro and in vivo DMPK. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Studies were supported by NIH (NIMH, MH082867, MH073676, and MH108498) and Acadia Pharmaceuticals (UNIV61505).

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): The WCNDD and Acadia are actively developing M1 PAMs for clinical development and profit. The M1 PAMs in this paper, while covered by a patent, are no longer under development or being pursued.

Supplementary Material

References

- Greenlee W.; Clader J.; Asberom T.; McCombie S.; Ford J.; Guzik H.; Kozlowski J.; Li S.; Liu C.; Lowe D.; Vice S.; Zhao H.; Zhou G.; Billard W.; Binch H.; Crosby R.; Duffy R.; Lachowicz J.; Coffin V.; Watkins R.; Ruperto V.; Strader C.; Taylor L.; Cox K. Muscarinic agonists in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Farmaco 2001, 56, 247–250. 10.1016/S0014-827X(01)01102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher A. Muscarinic receptor agonists in Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs 1999, 12, 197–214. 10.2165/00023210-199912030-00004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clader J. W. Recent advances in cholinergic drugs for Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Opin. Drug Discovery Dev. 1999, 2, 311–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannan S. K.; Sawchak S.; Miller A. C.; Lieberman J. A.; Paul S. M.; Brier A. Muscarinic Cholinergic Receptor Agonist and Peripheral Antagonist for Schizophrenia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384 (8), 717–726. 10.1056/NEJMoa2017015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melancon B. J.; Tarr J. C.; Panarese J. D.; Wood M. R.; Lindsley C. W. Allosteric modulation of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor: improving cognition and a potential treatment for schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Discovery Today 2013, 18 (23–24), 1185–1199. 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges T. M.; LeBois E. P.; Hopkins C. R.; Wood M. R.; Jones J. K.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W. Antipsychotic potential of muscarinic allosteric modulation. Drug News Perspect. 2010, 23, 229–240. 10.1358/dnp.2010.23.4.1416977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H. T. M.; van der Westhuizen E. T.; Langmead C. J.; Tobin A. B.; Sexton P. M.; Christopoulos A.; Valant C. Opportunities and challenges for the development of M1 muscarinic receptor positive allosteric modulators in the treatment for neurocognitive deficits. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 181, 2114–2142. 10.1111/bph.15982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn P. J.; Christopolous A.; Lindsley C. W. Allosteric Modulators of GPCRs as a Novel Approach to Treatment of CNS Disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2009, 8, 41–54. 10.1038/nrd2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley C. W. 2013 Philip S. Portoghese Medicinal Chemistry Lectureship: Drug Discovery Targeting Allosteric Sites. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 7485–7498. 10.1021/jm5011786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipe W. D.; Lindsley C. W.; Hallett D.. Quinolone M1 Receptor Positive Allosteric Modulators. U.S. Patent US8,389,545, 2013.

- Ma L.; Seager M.; Wittman M.; Bickel N.; Burno M.; Jones K.; Graufelds V. K.; Xu G.; Pearson M.; McCampbell A.; Gaspar R.; Shughrue P.; Danzinger A.; Regan C.; Garson S.; Doran S.; Kreatsoulas C.; Veng L.; Lindsley C. W.; Shipe W.; Kuduk S.; Jacobson M.; Sur C.; Kinney G.; Seabrook G. R.; Ray W. J.; et al. Selective activation of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor achieved by allosteric potentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 15950–15955. 10.1073/pnas.0900903106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirey J. K.; Brady A. E.; Jones P. J.; Davis A. A.; Bridges T. M.; Jadhav S. B.; Menon U.; Christain E. P.; Doherty J. J.; Quirk M. C.; Snyder D. H.; Levey A. I.; Watson M. L.; Nicolle M. M.; Lindsley C. W.; Conn P. J. A selective allosteric potentiator of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor increases activity of medial prefrontal cortical neurons and can restore impairments of reversal learning. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 14271–14286. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3930-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beshore D. C.; Di Marco C. N.; Chang R. K.; Greshock T. J.; Ma L.; Wittman M.; Seager M. A.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Fuerst J.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T.; Ray W. J.; Kuduk S. D. MK-7622: A first-in-class M1 positive allosteric modulator development candidate. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 652–656. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran S. P.; Dickerson J. W.; Plumley H. C.; Xiang Z.; Maksymetz J.; Remke D. H.; Doyle C. A.; Niswender C. M.; Engers D. W.; Lindsley C. W.; Rook J. M.; Conn P. J.; et al. M1 positive lacking agonist activity provide the optimal profile for enhancing cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 1763–1771. 10.1038/s41386-018-0033-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davoren J. E.; Garnsey M.; Pettersen B.; Brodeney M. A.; Edgerton J. R.; Fortin J.-P.; Grimwood S.; Harris A. R.; Jenkison S.; Kenakin T.; Lazzaro J. T.; Lee C.-W.; Lotarski S. M.; Nottebaum L.; O’Neil S. V.; Popiolek M.; Ramsey S.; Steyn S. J.; Thorn C. A.; Zhang L.; Webb D. Design and synthesis of γ- and δ-lactam M1 positive allosteric modulators (PAMs): convulsion and cholinergic toxicity of M1-selective PAM with weak agonist activity. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 6649–6663. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran S. P.; Cho H. P.; Maksymetz J.; Remke D.; Hanson R.; Niswender C. M.; Lindsley C. W.; Rook J. M.; Conn P. J. PF-06827443 displays robust allosteric agonist and positive allosteric modulator activity in high receptor reserve and native systems. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 2218–2224. 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook J. M.; Abe M.; Cho H. P.; Nance K. D.; Luscombe V. B.; Adams J. J.; Dickerson J. W.; Remke D. H.; Garcia-Barrantes P. M.; Engers D. W.; Engers J. L.; Chang S.; Foster J. J.; Blobaum A. L.; Niswender C. M.; Jones C. K.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W. Diverse Effects on M1 Signaling and Adverse Effect Liability within a Series of M1 Ago-PAMs. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 866–883. 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook J. M.; Berton J. L.; Cho H. P.; Gracia-Barrantes P. M.; Moran S. P.; Maksymetz J. T.; Nance K. D.; Dickerosn J. W.; Remke D. H.; Chang S.; Harp J. M.; Blobaum A. L.; Niswender C. M.; Jones C. K.; Stauffer S. R.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W. A novel M1 PAM VU0486846 exerts efficacy in cognition models without displaying agonist activity or cholinergic toxicity. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 2274–2285. 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engers J. L.; Childress E. S.; Long M. F.; Capstick R. A.; Luscombe V. B.; Cho H. P.; Dickerson J. W.; Rook J. M.; Blobaum A. L.; Niswender C. M.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W. VU6007477, a novel M1 PAM based on a pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine carboxamide core devoid of cholinergic side effects. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 2641–2646. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sako Y.; Kurimoto E.; Mandai T.; Suzuki A.; Tanaka M.; Suzuki M.; Shimizu Y.; Yamada M.; Kiruma H. TAK-071, a novel M1 positive allosteric modulator with low cooperativity, improves cognitive function in rodents with few cholinergic side effects. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 950–960. 10.1038/s41386-018-0168-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poslunsey M. S.; Wood M. R.; Han C.; Stauffer S. R.; Panarese J. D.; Melancon B. J.; Enger J. L.; Dickerson J. W.; Peng W.; Noetzel M. J.; Cho H. P.; Rodriguez A. L.; Morrison R.; Crouch R. D.; Bridges T. M.; Blobaum A. L.; Boutaud O.; Daniels J. S.; Burnstein E.; Kates M. J.; Castelhano A.; Rook J. M.; Niswender C. M.; Jones C. K.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W. Discovery of VU0467319/VU319/ACP-319: an M1 positive allosteric modulator candidate that advanced into clinical trials. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2025, 16, 95–107. 10.1021/acschemneuro.4c00769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley A. C.; Key A. P.; Blackford J. U.; Rook J. M.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W.; Jones C. K.; Newhouse P. A. Cognitive performance effects following a single dose of the M1 muscarinic positive allosteric modulator VU319. Alzheimer’s Dementia 2020, 16, e045339 10.1002/alz.045339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conley A. C.; Key A. P.; Blackford J. U.; Rook J. M.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W.; Jones C. K.; Newhouse P. A. Functional activity of the muscarinic positive allosteric modulator VU319 during a Phase 1 single ascending dose study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 29, S43. 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.01.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03220295?term=NCT03220295&rank=1 (accessed Sep 30, 2024).

- Pirali T.; Serafini M.; Cargnin S.; Genazzani A. A. Applications of deuterium in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5276–5297. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Orsi D. L.; Engers J. L.; Long M. F.; Capstick R. A.; Mauer M. A.; Presley C. C.; Vinson P. N.; Rodriguez A. L.; Han A.; Cho H. P.; Chang S.; Jackson M.; Bubser M.; Blobaum A. L.; Boutaud O.; Nader M. A.; Niswender C. M.; Conn P. J.; Jones C. K.; Lindsley C. W.; Han C. Development of VU6036864: a triazolopyridine-based high-quality antagonist tool compound of the M5 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 14394–14413. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c01193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.