Highlights

-

•

Lignocellulose biomass (LCB) is key renewable source for many bio-based products.

-

•

Grape pomace (GP) could be valorised in anaerobic digestion (AD) to produce biogas.

-

•

Presence of poorly-biodegradable elements in LCB limits methane production in AD.

-

•

The structure and dynamics of the GP metagenome were analyzed throughout the AD process.

-

•

Metagenomics will allow to create microbial starters tailored to AD of specific LCBs.

Keywords: Anaerobic digestion, Metagenomics, Lignocellulosic biomasses, Lignin biodegradation, Biogas production

Abstract

This study analysed the effect of the different lignocellulose composition of two crop substrates on the structure and dynamics of bacterial communities during anaerobic digestion (AD) processes for biogas production. To this end, cereal grains and grape pomace biomasses were analysed in parallel in an experimental AD bench-scale system to define and compare their metagenomic profiles for different experimental time intervals. The bacterial community structure and dynamics during the AD process were detected and characterised using high-resolution whole metagenomic shotgun analyses.

Statistical evaluation identified 15 strains as specific to two substrates. Some strains, like Clostridium isatidis, Methanothermobacter wolfeii, and Methanobacter sp. MB1 in cereal grains, and Acetomicrobium hydrogeniformans and Acetomicrobium thermoterrenum in grape pomace, were never before detected in biogas reactors. The presence of bacteria such as Acetomicrobium sp. and Petrimonas mucosa, which degrade lipids and protein-rich substrates, along with Methanosarcina sp. and Peptococcaceae bacterium 1109, which tolerate high hydrogen pressures and ammonia concentrations, suggests a complex syntrophic community in lignin-cellulose-enriched substrates. This finding could help develop new strategies for the production of a tailor-made microbial consortium to be inoculated from the beginning of the digestion process of specific lignocellulosic biomass.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The reorientation of the global energy industry towards renewable sources is one of the major challenges of this century and has become an excellent component of any alternative energy portfolio (Agbonifo, 2021). In particular, anaerobic digestion (AD) among the biochemical conversion of agricultural still represents an economically attractive technology to generate bioenergy and reduce greenhouse gas emissions (Dewil et al., 2006; Subbarao et al., 2023). AD processes naturally occurring in anoxic environments, where biomass is biochemically degraded by anaerobic bacteria in the strict absence of oxygen, generating methane and carbon dioxide as final reaction products (Agregán et al., 2022). Energy crops such as cereal grains (CG) are a common substrate for bioenergy production due to their high biogas potential (Babu et al., 2022; Singidunum University, Belgrade et al., 2021). However, they may cause important environmental burdens due to the requirement of intensive agricultural activities and fertilisers, with negative impacts on soils and water, as well as land use constraints and the impact on other non-energy commodities, such as food (Prasad et al., 2020). Currently, lignocellulosic residual biomass has received extensive attention because it is one of the most abundant organic compounds on earth, it is cheap and geographically distributed (Singhvi and Gokhale, 2019; Zhao et al., 2022). Although anaerobic co-digestion of various agricultural feedstock is a common approach in terms of sustainable biofuel production, the presence of poorly biodegradable components in lignocellulosic biomass dramatically limits methane recovery in AD systems (Blair et al., 2021; Jensen et al., 2021). The main challenge in the use of lignocellulosic materials for biogas production, remains their structure and composition, because it primarily consists of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin, that is extremely recalcitrant against microbial degradation (Khan et al., 2022; Olatunji et al., 2021). Although AD of lignocellulosic material has great potential its efficiency, and thus biogas production, is not always satisfactory due to poor or incomplete digestion (hydrolysis) that often results in economic losses that often make the process non-commercially viable (Raut et al., 2021). Grape pomace (GP), the main solid vinery waste, contains up to 45 % lignin (Jin et al., 2019). Considering that averagely 18 kg of GP is generated per 100 L of wine produced, about 5 million tons of such residue are annually yielded (Rockenbach et al., 2011). Nowadays, a recent European reform in the wine sector (EC Regulation 479/2008) promotes the gradual withdrawal of distillation subsidies and consequently revokes compulsory distillation. This should drive the promotion of integrated, sustainable and standardized alternative protocols for the valorization of solid winery waste.

An alternative valorization of GP could be represented by the production of biogas by AD process (Dinuccio et al., 2010). The structural properties and recalcitrant nature of GP limit the accessibility of hydrolytic microorganisms, thereby limiting the GP bioconversion to biogas (Sirohi et al., 2020). Moreover, it has been demonstrated that, due to high concentration of lignin and aromatic compounds, such as phenols and phenyl alcohols, in GP biodigestion, hydrolysis and acidogenesis phases requires more time than that necessary for easy degradable compounds, contributing to a longer duration of lag phase for transformation and also reducing methane production (Fabbri et al., 2015; Martinez et al., 2016). The GP moisture after pressing is around 20–30 % w/w, and the material is usually characterized by C:N ratio ranges from 40 to 45:1, pH ranges from 3 to 6, and low electrical conductivity (Martínez Salgado et al., 2019). Several mechanical and chemical procedures for saccharification have been established, but definitely there is no turn-key bioenergy lignocellulosic feedstock solution at this time (Gao et al., 2022).

A metagenomic approach has recently been proposed as a means of studying microbial communities and biodiversity involved in the AD process, being a large part of the microbiome in anaerobic digesters still unknown and therefore only classified on higher taxonomic ranks (Akyol et al., 2019). Despite the considerable advancement in research on AD of lignocellulosic biomass over the past decade, a more comprehensive understanding of hydrolytic microorganisms within bacterial consortia will contribute to uncover the rate-limiting phenomena of hydrolysis (Azman et al., 2015). Various strategies have been discussed to optimize the digestion process and highlight areas where improvements can be made with a focus on advancing the understanding on how studies of microbial community structure and function can be used to help design and operate efficient AD systems (Shrestha et al., 2017). Metagenomics offers the possibility of studying the genetic material of difficult-to-culture species within microbial communities with the competence to degrade lignocellulosic biomass (Laudadio et al., 2019). This approach could provide a new opportunity to elucidate lignocellulose degradation mechanisms used by currently lesser-known microbial species. These techniques also provide insights into the composition, functional gene profiling, and metabolic pathway reconstruction of microbial communities, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of their roles in biogas production (Campanaro et al., 2020). Knowledge of the microbiome residing in anaerobic digesters can be further used for the development of more efficient processes in conjunction with the identified consortium and could be essential to minimize process failures and create new strategies for optimizing lignocellulosic-based AD processes (Kumar et al., 2022; Lim et al., 2020; Roopnarain et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2024).

The focus on microbiomes and comparative genomic analyses of microbial communities present in different organic wastes is critical to better understand the molecular basis of AD activities and their use for lignocellulosic degradation without further pre-treatment and to achieve more effective and efficient AD performance for this biomass (Zhang et al., 2019).

In this research, we therefore aimed to (1) determine the biochemical methane potential (BMP) of lignocellulosic grape pomace (GP) as carbon source and compare it with the BMP of cereal grains (CG) in AD trials; (2) apply high-resolution whole metagenomic shotgun (WMS) analysis to explore the composition of microbiome during AD of CG and GP and compare microbial community dynamics; (3) relate microbiology to biogas performance, and investigate differences in reactors’ microbial community dynamics compared to the original inoculum culture.

The results of the present study support the hypothesis that integrating genome- based microbial community analysis with AD process monitoring and control strategies offers new possibilities for optimizing biogas production and ensuring process stability. Furthermore, our results could lay the foundation for producing microbial starter mixtures for AD of specific lignocellulosic biomasses, thus improving biogas production.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Set up and experimental design

Inoculum sludge, CG and GP were obtained from a local biogas production facility (Sesa Spa, Padua, Italy). CG was a mixture of corn silage, ground whole flour and corn cob. Lab scale batch reactor was set up with glass digesters of 250 ml of capacity, equipped with two-ways screw caps. The average pH of the inoculum was 8.0, VS/TS ratio (Volatile Solids, VS; Total Solids, TS) and TS were 82.6 % and 73.5 ± 2.0 g/kg (wet base) respectively. In each digestion test, 60 g of inoculum (seed bacterial culture sludge) was used and mixed with the substrate resulting in 14 trial reactors (seven with CG and seven with GP) to be analysed in parallel during AD and compared with the inoculum in metagenomic profiles. The VS/TS ratio of sample and inoculum in each bottle was 1:1. All reactors were tightly closed with rubber septa, incubated in a water bath (Argolab WB 22, Giorgio Bormac Srl, Modena, Italy) at 55 °C ± 1 °C and manually mixed for about 1 min once a day prior to measurement of biogas volume. The formed biogas was led into 1 % NaOH solution to remove CO2 and the volume of methane determined every 24 h using Dietrich–Frühling calcimeter (Mahmoodi et al., 2018). For reference purposes, the methane yield produced by the inoculum alone was determined and subtracted from the sample yields. Methane yields were expressed as volume of methane Nm3/tonne (normal cube meter per tonne) per corrected unit mass of VS (El-Mashad and Zhang, 2010). Every 5 days, a bottle was withdrawn and used as sample for chemical and genomic analysis. The time points for microbial analysis were selected based on regular intervals relative to the typical duration of the anaerobic digestion process (30 days) as reported by Semeraro et al. (2021). Sampling was suspended after 30 days, when chemical assays revealed that AD activity had concluded. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, with the mean values and corresponding relative standard deviations reported.

2.2. Chemical assays

pH was measured by a calibrated Crison basic 20 pH meter (Crison, Barcelona, Spain) at 20 °C. Total solids (TS), volatile solids (VS) and ashes on dry basis were determined using the combustion method at 105 ± 1 °C for 24 h according to “Standard Methods” (Clesceri et al., 1998). Lignin content was determined by means of the INNVENTIA Test Methods L 2:2016 (Costa et al., 2017). Sugars and volatile acids were analyzed using HPLC LC4000 (Jasco Inc., MD, USA), equipped with refractive index detector (Zappaterra et al., 2022).

2.3. DNA sample processing

Sludge samples collected from reactors were labelled "cg0" to "cg30" and "gp0" to "gp30" for different experimental time intervals for CG and GP, respectively, and stored at 20 °C until centralized analysis. Samples were collected, transferred into a sterile, DNA-free Eppendorf tube, and frozen at − 20 °C until use. Lysis Buffer (MC501C, Promega) was added to the sample, then transferred to a Lysing matrix B tube (MP Biomedicals), and homogenized following the manufacturer's instructions in a Fast Prep FP120 (MP Biomedicals). Microbial nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) were isolated using the Promega Maxwell® RSC system (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions and frozen at − 20 °C. Purified DNA was quantified by spectrophotometer (Shimadzu BioSpec‐nano) and by Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies) by using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Life Technologies).

DNA was fragmented using NEBNext® dsDNA Fragmentase for 30 min. NEBNext® Multiplex Oligos for Illumina® (Dual Index Primers set 1) were used to produce the library and label it with specific molecular barcodes. The library was generated from 100 ng of genomic DNA, in accordance with the NEBNext® Ultra™ II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina protocol (New England Biolabs). Then, AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) were used for library purification. Finally, the library was quantified using the High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent Technologies) on the Bioanalyzer instrument (Agilent). Sequencing was performed with an Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencer with 2 × 150-bp read, using NextSeq® 500/550 Mid Output Kit v2. The Illumina BaseSpace cloud platform (https://basespace.illumina.com/) was used to convert the raw Illumina output to the Fastq format and to assign reads to each individual (demultiplexing) according to sequencing barcodes. Quality control (QC) of sequencing data was done with FastQC (v.0.12.1, (Andrews, 2010)). Trimmomatic (v.0.36, (Bolger et al., 2014)) was used to trim from raw data bases with poor quality and read with length < 100bp. Parameters were defined as CROP:149, HEADCROP:0, SLIDINGWINDOW:5:20, MINLEN:100.

2.4. Taxonomic profiling

After QC, community taxonomic analysis of processed data was performed using BLASTN (Altschul et al., 1990) and Metagenomic Phylogenetic Analysis software (MetaPhlAn3 v. 3.0.11, (Beghini et al., 2021); MetaPhlAn4 v.4.0.6, (Blanco-Míguez et al., 2023)). BLASTN analysis was conducted using the NCBI “nt” reference database, parameters were set to include only matches with an e-value > 1 × 10–6, a percentage of identity ≥ 95 % and a minimum length > 100 bp. MEGAN6 (v.6.21.5, (Huson et al., 2007)) with default parameters was used for the analysis of BLASTN alignment results; taxonomical data were ranked for genus and species.

The processed data were also analysed with MetaPhlAn3 and MetaPhlAn4, using default parameters to align reads to their respective databases: the internal custom microbial database (mpa_v30_CHOCOPhlAn_201901) for MetaPhlAn3 and the latest version available of the dedicated database (mpa_vOct22_CHOCOPhlAnSGB_202212) for MetaPhlAn4.

Since there is no official classification of prokaryotes, the nomenclature of taxa provided by MetaPhlAn3 were used throughout the main text, figures and tables; in addition, names established by the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria and Prokaryotes were also provided.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Alpha-diversity was used to describe the microbiome diversity within sample and was measured with the Shannon H’ diversity index, Pielou evenness J index and the Margalef d richness index (Chiarucci et al., 2011). PERMANOVA analysis was applied to assess differences in microbial communities among the samples (Anderson, 2001).

In order to identify genera and species that define taxonomical differences between the two matrices, a linear discriminant analysis (LDA) Effect Size (LEfSe) algorithm (Segata et al., 2011) was applied using the LEfSe tool (version 1.0, http://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/galaxy/root/index). LEfSe was specifically designed for group comparisons of microbiome data with a particular focus on detecting change in relative abundance between two or more groups of samples with biological consistency. For this analysis, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to detect, for each taxon, the element with significant differential abundance in different classes (p < 0.05). After this step of feature selection, a LDA model was built with the group label as the dependent variable and observed abundance of taxa selected in above step as independent variables. Based on the obtained model, the effect size of each differentially abundant feature was estimated.

Finally, the LDA score for each taxon was obtained by computing the logarithm (base 10) of the effect size. The rank for each taxon was assigned based on the corresponding LDA score and further feature selection was achieved by setting a threshold for LDA scores. For the present analysis, the threshold on the logarithmic LDA score was set to 2.5 to be more conservative (p < 0.05 and LDA score > 2.5). In order to assess LEfSe results, the RStudio's package MaAsLin2 was used to evaluate the microbial differential abundance (Mallick et al., 2021), with arguments: correction method “BH”, transformation “AST”, normalization “TSS”, standardization “TRUE”.

RStudio v.4.2.2 (RStudio Team, 2020), with ape package, was used for constructing Neighbour Joining (NJ) trees, for principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis distance and to create heatmaps (function natively provided in R).

2.6. Functional analysis

Functional profiles were computed starting from the processed data using HUMAnN 3.0 (HMP Unified Metabolic Analysis Network, v. 3.0.0; (Beghini et al., 2021)). The samples were processed with default parameters and finally merged using the human_join_tables.py script.

To evaluate the metabolic cycles statistically different in the two biomasses analysed, the Welch's t-test implemented in STAMP (v. 2.1.3; (Parks et al., 2014)) was applied and the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was performed to control for false discovery rate.

All pathways found to be significantly enriched between substrates were investigated in depth with the MetaCyc website (https://metacyc.org/) and represented in an heatmap by STAMP.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Biochemical methane potential and microbial diversity

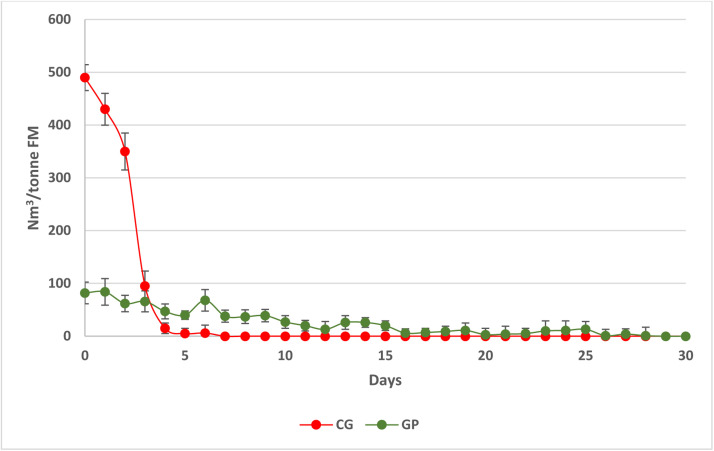

CG and GP were selected as substrates for the present investigation because they represent two biochemically contrasting feedstocks. CG was chosen due to its high starch content and rapid degradability, making it an optimal feedstock for biogas production. In contrast, GP is a widely available and sustainable agro-industrial byproduct that contains a substantial fraction of recalcitrant lignocellulosic material. While its complex composition presents challenges for microbial degradation, its abundance highlights its potential as a promising substrate for biogas production within a circular economy framework. Furthermore, GP was not subjected to any pretreatment prior to anaerobic digestion. This approach facilitates the investigation of microbial dynamics within untreated lignocellulosic biomass, which can aid in identifying naturally occurring microbial consortia. These consortia have the potential to be utilized in the development of microbial starter cultures for the anaerobic digestion of specific lignocellulosic feedstocks, thereby enhancing biogas production. Average daily biogas production from cereal grains and grape pomace AD are shown in Fig. 1. CG had the highest biogas yield, compared with GP. After 5 days of digestion, CG had completely exhausted the substrate, while GP showed a very slow progress and a minimal biogas production within 30 days. The key factor contributing to CG's rapid substrate exhaustion within five days, in contrast to GP's slow progress, is their fundamental biochemical composition difference. CG is starch-rich, whereas GP is predominantly lignocellulosic. Starch is easily hydrolyzed by microbial enzymes, quickly releasing fermentable sugars and facilitating biogas production. This leads to swift depletion of available organic matter within a few days. In contrast, GP's lignin creates structural barriers that significantly hinder microbial enzyme access and hydrolysis. This results in much slower degradation, prolonging fermentable sugar release and leading to minimal biogas production for over 30 days.

Fig. 1.

Biogas yield from cereal grains and grape pomace AD, expressed as Nm3/tonne FM. Each data point is the average (± standard deviation) of measurements from six reactors.

Characterization of CG- and GP-based substrates has been reported in Table 1. For CG-based substrates (Table 1A), all parameters evidenced a rapid digestion process within the initial five-day period.

Table 1.

Chemical characterization of the AD of cereal grains (A) and grape pomace (B) over 30 days. TS, total solids; VS, volatile solids. Data are expressed as kilograms of fresh matter (FM).

| (A) Cereal grains | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day | TS (g/kg FM) | VS (g/kg FM) | pH | Lignin (g/kg FM) | Cellobiose (% FM) | Glucose (% FM) | Acetic acid (% FM) |

| 0 | 145.0 | 121.5 | 8.0 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0 |

| 5 | 57.9 | 31.5 | 6.0 | 0.32 | 0 | 0 | 0.16 |

| 10 | 74.0 | 33.7 | 5.8 | 0.24 | 0 | 0 | 0.17 |

| 15 | 64.1 | 29.4 | 6.0 | 0.27 | 0 | 0 | 0.19 |

| 20 | 59.0 | 35.1 | 5.9 | 0.28 | 0 | 0 | 0.16 |

| 25 | 55.9 | 31.8 | 5.9 | 0.29 | 0 | 0 | 0.20 |

| 30 | 54.5 | 27.5 | 6.0 | 0.29 | 0 | 0 | 0.17 |

| (B) Grape pomace | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day | TS (g/kg FM) | VS (g/kg FM) | pH | Lignin (g/kg FM) | Cellobiose (% FM) | Glucose (% FM) | Acetic acid (% FM) |

| 0 | 150 | 122.2 | 8.0 | 0.59 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.009 |

| 5 | 142 | 115.1 | 8.4 | 0.56 | 0 | 0.05 | 0 |

| 10 | 140 | 113.3 | 8.2 | 0.57 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | 131 | 101.2 | 8.3 | 0.56 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | 138 | 107.9 | 8.2 | 0.58 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | 144 | 113.4 | 8.3 | 0.60 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 30 | 145 | 117.3 | 8.2 | 0.61 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Residual acetic acid from day 5 to day 30 may indicate cessation of methanogenesis due to suboptimal conditions for the metabolism of methanogens, such as pH, which in the case of the CG substrate tends to be acidic, unlike in the GP substrate where the pH remains approximately 8 throughout the process. The accumulation of acetic acid in CG from days 5 to 30 was attributed to disrupted methanogenesis caused by a decline in pH levels. Acetic acid, which is crucial for acetoclastic methanogens, accumulated due to an imbalance in the anaerobic digestion process. As easily degradable substrates became depleted, there was a reduction in hydrolytic and fermentative activity, leading to a buildup of volatile fatty acids (VFAs). This accumulation resulted in a decrease in pH, thereby inhibiting methanogenic activity. Optimal methanogenesis is known to occur at a pH range of 6.5–8; however, when pH levels fall below 6.0, the conversion of acetate to methane is significantly hindered (Latif et al., 2017).

Lignocellulosic biomasses have lower biodegradability and biogas yields compared to starch- or sugar-rich substrates due to their high content of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, which limit microbial accessibility (Kumar et al., 2008). CG, being primarily starch-based, typically exhibit higher biogas yields compared to classical lignocellulosic substrates. Several studies reported methane yields exceeding 350–400 mL CH₄/g VS for starch-rich biomasses, while lignocellulosic residues often achieve lower values, ranging between 150 and 300 mL CH₄/g VS, depending on pre-treatment strategies (Mirmohamadsadeghi et al., 2014; Monlau et al., 2015). Our results are comparable to other lignocellulosic residues such as wheat straw and corn stover, which generally exhibit methane yields in the range of 150–280 mL CH₄/g VS (Kumar et al., 2008).

Table 1B shows compositional parameters of GP-based substrate. As evidenced by the low and slow biogas production rate, high lignin content inhibited anaerobic digestion in fact a previous study demonstrated that demonstrated that a 1 % increase in lignin content would result in a 7.49 L CH4/kg total solid reduction (Nwokolo et al., 2020) and for this reason, several pre-treatment strategies have been developed to break down the complex heterologous lignin network, facilitating enzyme access within the matrix (Semeraro et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2014).

The conversion efficiency and productivity differ significantly between CG and GP, with values calculated at 5.64 and 12.94 Nm3 Biogas/g TS, and 1.13 and 0.44 Nm3 biogas/g TS per day, respectively. The higher productivity observed in CG is attributed to an elevated biogas concentration and the rapid consumption of TS within a 5-day period. Conversely, the anaerobic digestion (AD) process on the GP substrate progresses at a slower rate, with limited TS depletion, thereby substantially reducing overall process productivity. Notably, the conversion efficiency of the GP-based process surpasses that of the GC-based process, suggesting that the cellulolytic microbial species involved are potentially highly efficient biogas producers, which can lead to significant issues for scale-up purposes.

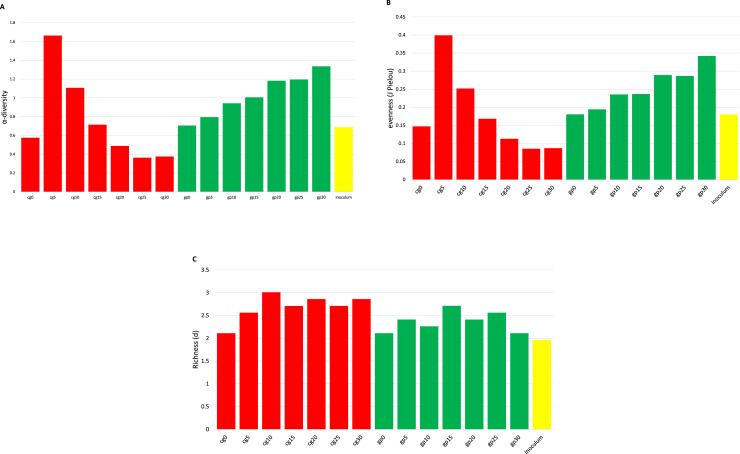

Fig. 2 shows the diversity indices of microbial species in the 15 samples (seven with CG, seven with GP, and inoculum).

Fig. 2.

Diversity inside different matrices during time: 2A) alpha-diversity index, 2B) J Pielou's Evenness index, 2C) Richness index (d).

Alpha diversity, along with J Pielou's evenness, (Fig. 2A and 2B) calculated on individual samples showed a different trend in the two substrates: CG samples (cg0–30) presented a peak corresponding at day 5 of fermentation and then decreased until day 30, while the GP samples showed a linear growth over time. Richness index (Fig. 2C) showed a similar trend in both matrices, growing in the first 10 days, then remaining stable until day 30.

The higher the biogas yield was, the higher was the J Pielou's evenness value observed, corresponding to early days for CG (day 5) and to final days for GP (day30). This common trend between biogas production (see Fig. 1) and the evenness index indicates that the best performing process (in terms of biogas production and methane content) is always positively correlated with greater community uniformity (Merlino et al., 2013). High community evenness is particularly important in a system such as AD, as it indicates greater flexibility of the microbial community within the fermentation system, that enables the community to fully exploit all metabolic pathways, as well as co-metabolic pathways, which are known to play an important in AD performance (Hashsham et al., 2000). Further to this, communities with uneven distributions of diversity tend to be dominated by groups of microorganisms specialised to current conditions, when exposed to external changes (e.g. pH) they are unable to adapt rapidly and require long recovery times. On the contrary, microbial communities with more even distributions of diversity are able to use parallel metabolic pathways and have greater functional stability (Ferguson et al., 2018). Otherwise, a gradual increase in diversity was observed over time in GP substrate samples.

PERMANOVA results indicate a significant difference (p = 0.013) between the two matrices, with the variance explained equal to 40 %. Additionally, the dispersion test confirms the assumption of homogeneity, supporting the robustness of the analysis and the real differences between groups.

3.2. Taxonomical profiling

The processing details of WMS sequencing for all available samples, seven for both CG and GP plus inoculum, are shown in N

Table S1. The throughput of sequencer was quite similar among the 15 samples, even after filtering out low quality sequence (supplementary Table S1).

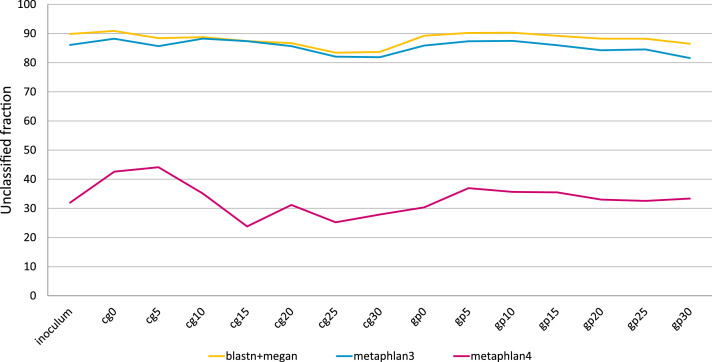

Three different software, differing in their ability to assign reads to specific taxonomic units, were used to build taxonomical profiles: in terms of number of reads classified, BLASTN and MetaPhlAn3 showed similar values, while classification rates increased by an order of magnitude with MetaPhlAn4 (Fig. 3), which was able to improve the metagenomic taxonomic profiling using metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) to define an expanded set of species-level genome bins (Blanco-Míguez et al., 2023). Despite using MAGs for taxonomic analysis may have advantages over the reference-based approach, we have decided to follow the latter methodology because of (i) its precision in the analysis of known strains, which is the main focus for studying an inoculum that could lead to an increase in biogas production from lignocellulosic biomass, (ii) its lower computational requests, and (iii) because MAGs based techniques can only capture a small portion of organisms in complex communities due to inadequate coverage for many taxa (Blanco-Míguez et al., 2023; Young et al., 2021).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of unclassified reads retrieved in taxonomical analyses using BLASTN (yellow), MetaPhlAn3 (blue) and MetaPhlAn4 (pink).

All the three classification showed the same trend, with sample cg0 having the fewest reads classified and sample cg25 with the highest classification rate.

One of the main problems in taxonomic profile reconstruction, obtained from metagenomic analyses, lies in the high percentage of reads that fail to be uniquely assigned to a species and are therefore classified as "unclassified organism" or "uncultured bacterium/archeon”. In the present analyses, the percentage of unclassified reads for BLASTN+MEGAN6 and Methaphlan3 reached 80–90 %, whereas Methaphlan4 enabled a more thorough assignment of reads by adopting the species-level genome bins system, which dramatically reduced the number of unassigned reads (Fig. 3).

Despite the great potential of MetaPhlAn4 in metagenomic data analysis, it did not prove to be an optimal approach for this specific study design because, by targeting generic OTUs rather than individual cultivable strains, it was less effective in identifying specific strains that could then be used to improve and optimize the fermentation system. On the other hand, BLAST-based analysis also had some disadvantages, mainly related to the high computational time requested for analyses and to the redundancy of the database used by BLASTN.

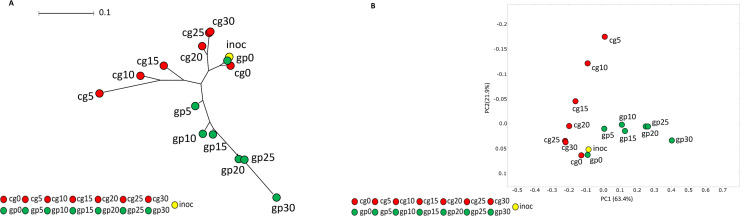

Furthermore, as a first descriptive approach, differences between microbial community during biogas production was analyzed by NJ tree construction on BLASTN results (Fig. 4A) and by PCoA (Fig. 4B) for MetaPhlAn3. Both analyses showed exactly the same trend, revealing different dynamics for the two substrates during fermentation processes: in GP the microbial community changed slowly over time, while CG showed a rapid initial change in microbiome structure, corresponding to a high rate of biogas production, and then the community tended to return to a composition similar to initial inoculum composition.

Fig. 4.

Dynamics of microbial community during biogas production process represented by: 4A) Neighbour Joining tree from BLASTN output; 4B) plot of principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of microbial composition from MetaPhlAn3 output, the analysis was based on Bray-Curtis matrix distance (species).

The microbial community retrieved in samples from CG fermentation after 5 days (cg5) was far from the starting point (inoculumu-cg0) in both Figs. 4A and 4B; then through time microbial composition in CG returned similar to cg0. Conversely, microbial composition of samples obtained from GP fermentation gradually deviated from the starting point (inoculum-gp0) until day 30 during biogas production process.

Therefore, based on above considerations and on initial descriptive analyses of microbial community dynamics, which showed widely overlapping results between BLASTN and MetaPhlAn3, only the taxonomic profile generated with MetaPhlAn3 will be discussed in detail below, while results of the taxonomic analysis performed with BLASTN+MEGAN6 and MetaPhlAn4 are presented in supplementary materials (supplementary Fig. S2 to S5).

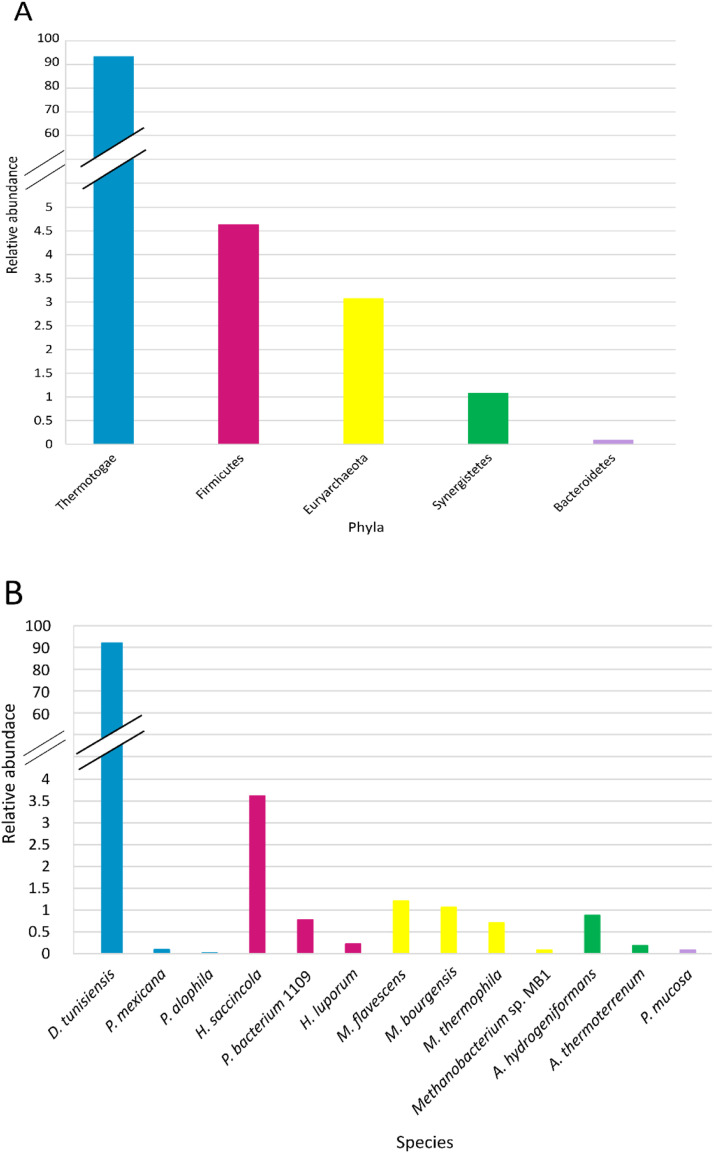

Taxonomical composition of inoculum, in terms of phyla and species, is detailed in Fig. 5A and B; this sample was characterized by the presence of 5 phyla, the most abundant was Thermotogae (over than 65 % of assigned reads), followed by Firmicutes (renamed as Bacillota), Euryarcheota (the only archaeal phylum identified), Synergistetes and Bacteroidetes. Eleven genera and 14 species were identified in the inoculum: Defluviitoga was the most abundant genera and Defluviitoga tunisiensis the dominant species (Fig. 5A and B).

Fig. 5.

Inoculum composition: 5A) phyla, 5B) species obtained with MetaPhlAn3.

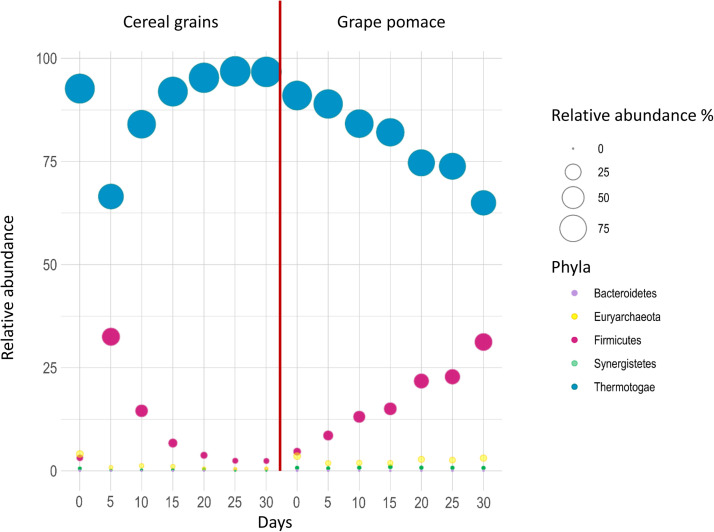

Taxonomic profiles from time 0 to day 30 of both CG and GP samples are showed in Fig. 6, where the distribution of phyla are presented.

Fig. 6.

Taxonomic profiles, in terms of phyla, detected from time 0 to day 30 in the two different substrates (cereal grain and grape pomace) and identified with MetaPhlAn3.

In all samples, as in the inoculum, sequences were classified into 5 phyla (Thermogae, Firmicutes, Euryarchaeota, Synergistetes, and Bacteroidetes), with Thermogae being, consistently, the most abundant phylum followed by Firmicutes, while the other three phyla were present with lower relative abundances.

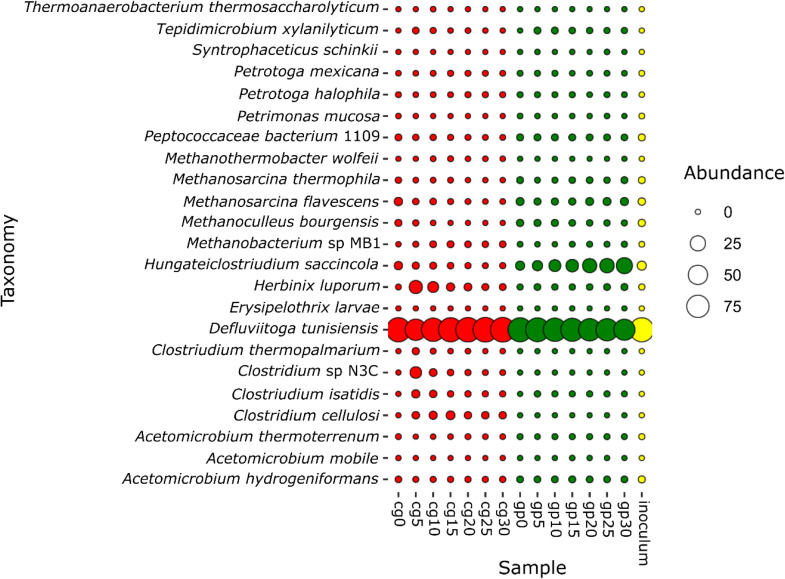

Within the 5 phyla identified in all samples and described above, a total of 16 genera and 23 species were detected. All species identified in both CG and GP are shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

- Taxonomic profile obtained with MetaPhlAn3, in terms of species, detected from time 0 to day 30 from both cereal grains (cg0–30) and grape pomace (gp0–30), plus inoculum.

The most abundant genera were Defluviitoga, Hungateiclostridium (reclassified as Acetovibrio) and Herbinix. The most represented species were: D. tunisiensis in all samples (over 65 % of all samples), Hungateiclostridium saccincola (reclassified as Acetovibrio saccincola) in GP samples and Herbinix luporom in CG samples; all other species had a relative abundance lower than 1 % (Fig. 7).

3.3. Differences in microbial composition among different substrate

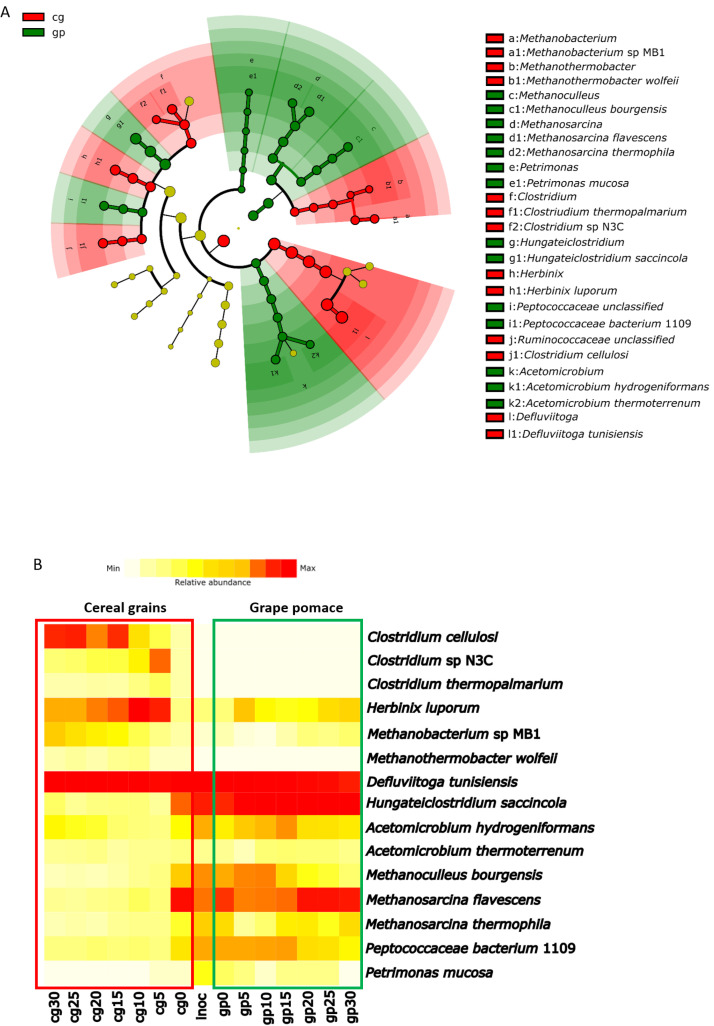

LEfSe analysis was used to verify significant differences between taxonomic profiles of CG and GP samples. A more stringent LDA threshold (set at 2.5) was used to identify the most significantly enriched set of microorganisms, at both genus and species level, that define microbial profiles between different biomasses. Results are shown in Fig. 8A.

Fig. 8.

8A) Cladogram plotted from LEfSe analysis, comparing all CG samples with all GP samples. Taxonomic levels are represented by rings with phyla in the outermost ring and species in the innermost ring. Each circle represents a member within that level, the dimension of each node is proportional to relative abundance of the represented taxon. Taxa with enriched level in samples from CG are coloured in red, those enriched in samples from GP are coloured in green; unenriched taxa are ochre coloured; 8B) Relative abundance of strains resulted significantly different in LEfSe analysis between substrates, represented as an heatmap. Abundancy values were showed with a shade colour scale from white (0 %) to red (100 %).

LEfSe analysis showed that, in total, 12 genera and 15 species represent the biomarkers that significantly discriminate taxonomic profiles of the two matrices, specifically: 6 genera and 7 species enriched in samples from CG; 6 genera and 8 species enriched in samples from GP. Relative abundances among all samples of these 15 species was used to generate the heatmap represented in Fig. 8B As previously described, D. tunisiensis was largely (relative abundance >65 %) present in all samples during all phases of biogas production (Fig. 8B), but resulted statistical most abundant in CG community samples (Fig. 8A). Samples from CG were also significantly enriched by the presence of Clostridium cellulosi, Clostridium sp. N3C, Clostridium thermopalmarium, Methanobacterium sp. MB1 and Methanothermobacter wolfeii (Fig. 8A). During first days (cg5–15) of production of biogas in samples from cereal grains the substrate is rich in readily degradable starch, favoring the growth of hydrolytic and fermentative bacteria such as H. luporum, Clostridium sp. N3C, C. thermopalmarium and M. wolfeii (Fig. 8B). These species efficiently break down starch into simpler sugars and fermentable intermediates, driving the rapid production of biogas. However, once the starch is exhausted, microbial selection is driven by the residual organic matter. Even in cereal grains, a small fraction of lignocellulosic material is present, and in the absence of readily fermentable carbohydrates, lignocellulose-degrading bacteria such as C. cellulosi can proliferate during late phases of biogas production in CG samples. Simultaneously, the increased presence of Methanobacterium sp. MB1, which can utilize hydrogen and CO₂ produced during the degradation of more recalcitrant substrates during the late phases, suggests a shift in methanogenic pathways (cg20–30, Fig. 8B).

The second most abundant species detected in all samples was H. saccincola, which was one of the most common species at the beginning of biogas production process (inoculum, cg0, gp0) and remained significantly highly abundant during all time in grape pomace samples (Fig. 8B). Samples from GP were also enriched by Acetomicrobium hydrogeniformans, Acetomicrobium thermoterrenum, Methanoculleus bourgensis, Methanosarcina flavescens, Methanosarcina thermophila, Peptococcaceae bacterium 1109 and Petrimonas mucosa (Fig. 8A and B). A. hydrogeniformans, M. bourgensis and P. bacterium 1109 presented the same dynamic: they were abundant during first stages (gp5–15) of fermentation and then their abundance decreased. Conversely A. thermoterrenum, M. thermophila and P. mucosa showed a progressive increase during last days of biogas production (gp20–25). M. flavescens exhibited a different growth dynamic: it was very abundant at the beginning (gp0), its abundance slightly decreased during the later stages of fermentation (gp5–15) and then increased again in the last ten days (gp20–30, Fig. 4B).

Since biogas production rate had its peak during first days of fermentation process a comparison of early time samples (5–10–15 days), on both substrates, were performed with LEfSe (see supplementary Figure S1). Principal results of this analysis were similar to the general comparison between samples (CG vs GP Fig. 8A), but this analysis also revealed the presence of Clostridium isatidis as significantly enriched in CG samples, and Petrotoga halophila enriched in GP samples.

In recent years, it has emerged that different methods for microbiome differential abundance tests can lead to substantially different results (Nearing et al., 2022). We therefore further analysed MetaPlhAn3 data with MaAsLin2, which allows both arcsine square root data transformation and correction of false discovery rate for multiple testing. MaAsLin2 results on the general microbial composition (CG vs GP) essentially confirmed LEfSe analyses (see Supplementary Table S2): all strains detected as significantly more abundant in GP samples in Fig. 8A were confirmed by MaAsLin2 analyses except for P. mucosa which showed a borderline value (corrected p-value 0.064); as for strains characterising CG samples, C. cellulosi, Methanobacterium MB1 and M. wolfeii were confirmed as significant, while C. sp. N3C and C. thermoplamarium showed a nominal borderline significance (0.054 and 0.053, respectively) which was lost after BH correction. No other strains emerged as significant in both biomass using MaAsLin2.

The comparison between biomasses at early stage (5–10–15 days) of fermentation performed with MaAsLin2 (Supplementary Table S3) was slightly less consistent with LEfSe results: although all 15 significant strains in LEfSe analysis exceed the significance threshold of MaAsLin2 only 11 reached the nominal significance (Supplementary Table S3). This lower level of agreement between LEfSe and MaAsLin2 analyses on early-stage samples may be due to the fact that halving the number of analysed samples increases the impact of structural zeros on standard errors and, more generally, on statistical analysis.

3.4. Structure of microbial community in key microbiological steps of AD process

In recent years, various molecular biological techniques (including genomics, metagenomics, meta-transcriptomics, metaproteomics and metabolomics) were applied to investigate composition and dynamics of AD microbiome and to understand its implications for biogas production processes (Campanaro et al., 2020; De Vrieze et al., 2021; Hassa et al., 2018).

Aim of this work was to compare, through WMS approach, the different dynamics of the microbiome during GP and CG fermentation with the objective of identifying effective approaches to optimize biogas production and ensure process stability in GPs.

Even though the two substrates showed different microbiome structure and dynamics over time, they were both characterized by very high levels of D. tunisiensis (Fig. 8B), confirming the capacity of this bacterium to metabolize both hexoses and pentoses to VFA, CO2 and H2, serving as substrate for methanogenesis (Maus et al., 2016). High abundances of D. tunisiensis were already detected in a thermophilic laboratory fermenter (Maus et al., 2016), highlighting the broad spectrum of substrates (polymers, oligosaccharide, acids and alcohols) that D. tunisiensis was capable of metabolizing therein including the ability to degrade cellulose since genes encoding non-cellulosomal cellulases were identified in its genome. Li et al. (2019) confirmed the cellulose-degrading ability of D. tunisiensis, showing how this microorganism was predicted to participate in AD of a variety of carbohydrates and produces acetate, H2 and CO2 and Basak et al. (2022a) pointed out that the crucial role played by D. tunisiensis in biogas production is due to its strong cellulolytic activity and ability to degrade crystalline cellulose, xylan, and various hemicellulosic monosaccharides. Its high abundance indicates increased polymer degradation, particularly in digesters with untreated biomass (Basak et al., 2022c). This cellulose-degrading bacterium is an efficient fermenter, producing H₂, CO₂, and VFAs, mainly acetate, from complex polysaccharides like cellulose and starch (Ben Hania et al., 2012). Its rapid assimilation of carbohydrates and direct conversion of monosaccharides into acetate and hydrogen, rather than to propionate and butyrate, reduce the abundance of syntrophs but enhance hydrogenotrophic archaeal activity, further boosting hydrogen production (Li et al., 2019). Overall, the prevalence of D. tunisiensis positively impacts biogas yield by accelerating biomass degradation and optimizing hydrogen and acetate production, essential components of the anaerobic digestion process.

Other research supported the idea that the high H2-producing ability of D. tunisiensis significantly influenced the proportion of hydrogenotrophic archaeal species that, syntrophically associated with this bacterium, can utilize CO2 and H2 for methanogenesis (Stolze et al., 2016).

Next to D. tunisiensis, two other bacteria, H. luporum and H. saccincola, also characterized at high levels CG and GP respectively (Fig. 4B). With regard to H. luporum, although its relative abundance was significantly higher in CG, its levels in GP were >3 % making it a relatively abundant species in this matrix as well. The complete genome sequence of H. luporum was reported in 2016 (Koeck et al., 2016) and its characterization showed that the bacterium was able to digest cellulosic and hemicellulosic substrates. Also, Maus et al. (2017) described H. luporum to be involved in thermophilic degradation of lignocellulosic biomass representing, together with C. cellulosi, an important cellulose degrader.

In 2019 Rettenmaier et al. (2019) showed that H. saccincola was closely related to Hungateiclostridium thermocellum, a well-known key cellulolytic such as C. cellulosi and Herbinix hemicellulosilytica. Recently, a study aimed to characterize the synergism of a hydrolytic/cellulolytic bacterial consortium isolated from biogas fermenters proposed that enzymatic activity of H. thermocellum liberates soluble mono- and oligosaccharides from cellulose and hemicellulose, thereby promoting growth of saccharolytic bacteria. Microbial synergism is supposed to accelerate biomethane production in AD of plant fibers. As some microorganisms metabolize, they produce substrates necessary for those in subsequent stages. Hydrolytic microorganisms, for instance, break down polymeric molecules into monomers for microorganisms involved in later stages (Ahuja et al., 2024; Rettenmaier et al., 2020).

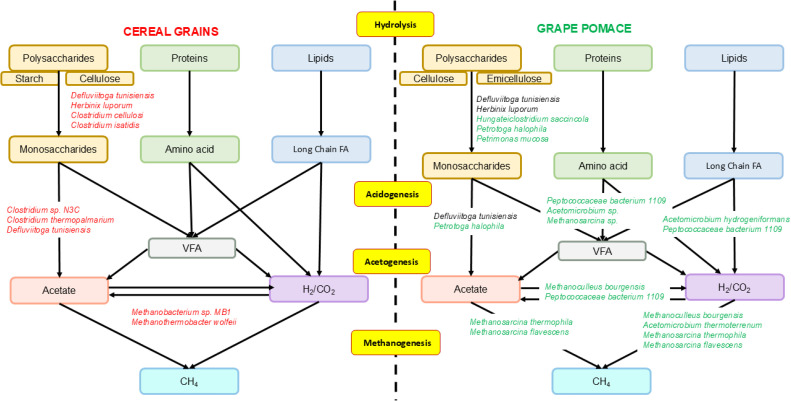

Present results seem to confirm the importance of this metabolic synergy, in fact in both matrices the co-presence of cellulolytic, saccharolytic and hydrolytic bacteria was confirmed: in CGs, H. luporum was simultaneously present with by a consortium of Clostridia among which the non-cellulolytic Clostridium sp. N3C and C. thermopalmarium strains, while the cellulolytic H. saccincola and H. luporum in GP were accompanied with non-cellulolytic Acetomicrobium sp. and P. mucosa (Fig. 9) as we will discuss below.

Fig. 9.

Functional groups of microorganisms observed in hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis and methanogenesis processes. Microorganisms that increased in abundance in CG are marked in red, and those that increased in abundance in GP are marked in green.

A further general consideration of overall microbiome dynamics between biomasses regards the process of methanogenesis, which is carried out by two different types of archea: M. wolfeii and Methanobacterium sp. MB1 characterised CGs while, M. thermophila and M. flavescens were more represented in GP and, reasonably, all increased their relative abundance toward the terminal phase of AD cycle, indicating their role in acetoclastic and hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis (Fig. 9). It is interesting to note that these results are consistent with other studies (Basak et al., 2022c, 2022b) that indicated how, in both anaerobic digester sludge (ADS) and acclimated consortium (AC) seed digesters, Methanosarcina abundance increases significantly during the exponential phase of the digestion. The authors also reported that the dominance and distribution of Methanosarcina in the exponential phase strongly suggests that acetoclastic methanogenesis is involved in the biomethanation of lignocellulosic biomasses.

To date, while the role of Methanosarcina in AD is fairly well described in literature, while present analysis is one of the first studies that identify the archea Methanobacterium sp. MB1 with a main role in methanogenesis from CG. Regarding M. wolfeii some recent analyses well describe its role and functional characteristics in biogas plants (Ale Enriquez and Ahring, 2024; Hassa et al., 2023, 2019).

3.4.1. Dynamics of microbial community in AD process for cereal grains

Exploring structure and dynamics of CG microbial community in more detail, comparing early (5–10–15 days) samples between CG and GP, LEfSe analysis (Supplementary Fig. S1) revealed that C. isatidis was significantly enriched in CG. Little is known about C. isatidis, but its role in AD results from a 1999 study (Padden et al., 1999) indicating this clostridium strain as capable of fermenting a variety of substrates, including either monosaccharides or starch. Moreover, we observed that during early days (cg5–15) there was a higher abundance of Clostridium sp. N3C and C. thermopalmarium (see supplementary figure S1), both are non-cellulolytic, hydrogen-producing bacteria and both seemed to contribute to butyrate production (Du et al., 2010; Maus et al., 2017). The co-existence of cellulolytic strains, such as C. isatidis and H. luporum, and hydrogen producers, such as Clostridium sp. N3C and C. thermopalmarium seen in the present study highlights that these strains, by taking advantage of their specific metabolic capacities, offers a promising new way to improve the conversion efficiency of cellulose to hydrogen. In fact, using cellulolytic bacteria for hydrogen production often results in a low hydrogen yields, due to bacteria's poor growth rates and pH sensitivity (Desvaux, 2006, 2005).

Present analysis is one of the first studies that identify Methanobacterium sp. MB1 associated with M. wolfeii during the later stages (cg20–30, Fig. 8B) suggests that hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis was occurring. These two archaea are both hydrogenotrophic methanogens that use formate, hydrogen, and carbon dioxide as substrates for methanogenesis and require acetate for growth (Maus et al., 2017). Furthermore, it cannot be ruled out that C. cellulosi might form a syntrophic association with these hydrogenotrophic methanogens, in particular with Methanobacterium sp. MB1 since both these prokaryotes showed a similar growth in their abundance in final stages of the fermentation process.

3.4.2. Dynamics of microbial community in AD process for grape pomace

As described (Fig. 4A and B) the structure of the microbial community changed slowly over time in GP, maintaining biogas production capacity longer, albeit at lower levels, than CGs (Fig. 1). Next to the two cellulolytic bacteria already discussed, D. tunisiensis and H. saccincola, which were present at high abundance throughout GP digestion as well, this matrix was characterized by the presence of A. hydrogeniformans, M. bourgensis and P. bacterium 1109, that typified first days of AD and A. thermoterrenum, M. thermophila, M. flavescent and P. mucosa showing a progressive increase during last days of AD (Fig. 8B).

Acetomicrobium genus, identified in 2016 and initially classified as Anaerobaculum, was reported in biogas production reactors, and their role was attributed to digestion of fats and proteins (Litti et al., 2021), as well as glucose fermentation to acetate, CO2 and H2 (Ben Hania et al., 2016). However, to date, little or no information is available in literature about the two species here detected, i.e. A. hydrogeniformans and A. thermoterrenum. Their presence in GP digestion could be explained considering the high concentration of promptly digestible lipids (7–15 %) and proteins (8–16 %) that characterized this substrate (Spinei and Oroian, 2021). In fact, in A. hydrogeniformans genome a thermostable esterase was identified presenting high catalytic activity with a preference towards short-acyl-chain esters(Cook et al., 2018), while A. thermoterrenum was involved in glycerol conversion (Magalhães et al., 2020), both processes being related to lipid metabolism during AD.

Moreover, it is interesting to notice that both species of Acetomicrobium observed in this study potentially act as syntrophic partner with homoacetogenic or syntrophic acetate-oxidizing bacteria (SAOB) (Li et al., 2022), and with acetoclastic or hydrogenotrophic methanogens (HM) even if their role in these syntrophic communities still remains enigmatic (Dyksma et al., 2020). A strong association between SAOB and HM is well documented and, compared to acetoclastic methanogenesis, methane production from the association between SAOB and HM is thermodynamically favoured at high temperatures (Dolfing, 2014). In this regard, the co-presence of A. hydrogeniformans and M. bourgensis, a known syntrophic partner of SAOB bacteria (Manzoor et al., 2016), detected in this study at early stages of GP AD (Figs. 8B and 9) might explain how the system was able to synthesize methane via the hydrogenotrophic pathway even in early stages of fermentation of this biomass.

P. halophila and P. bacterium 1109 species were also identified in our GP substrate. So far, Petrotoga species has been isolated only from oil reservoirs, whereas P. bacterium 1109 was typically classified as belonging to acetogenic community, highly abundant in most biogas plants (Singh et al., 2021a). With network analyses, Buettner et al. (2019) demonstrated that P. bacterium 1109 was a key module in both hydrogenotrophic and acetoclastic methanogens, highlighting possible SAOB behaviour. An additional ability of P. bacterium 1109 appears to be the conversion of propionate to methane, through cooperation between P. bacterium and the methanogen M. bourgensis (Singh et al., 2021b). This ability is based on the characteristics of P. bacterium 1109, an ammonia-tolerant acetate-oxidizing syntrophic bacterium, that can operate even in presence of inhibitory concentrations of ammonia resulting from protein catabolism (Singh et al., 2021b).

The later GP fermentation stages, were characterized by the presence of two relevant Methanosarcina species, M. flavescens and M. thermophila. M. flavescens is a hydrogenotrophic and acetoclastic methanogen species that could utilize acetate, methanol, moni-, di- and trimethylamine as carbon and energy sources (Kern et al., 2016), and can also proliferates at increased shear velocity when acetic acid is the major VFA component (Cayetano et al., 2020); conversely, M. thermophila is a better-known thermophilic archea that was referred to as acetoclastic methanogen but that can grow well also by utilizing methanol or methylated amines and slowly utilizing H2/CO2 (Lerm et al., 2012). Both Methanosarcina identified in GP substrate belonged to the physiological group designated as “type I”, characterized by the presence of c-type cytochrome which confers on them the ability to consume H2 as an electron donor and to possess an energy converting hydrogenase necessary for acetate metabolism through H2 cycling (Zhou et al., 2021). This ability enables them to withstand high hydrogen partial pressures, compared with methanogens present in CG substrate, lacking cytochrome c (Thauer et al., 2008). This could be presumably due to the prevalence of catabolic pathways (Ling et al., 2022; Wagner et al., 2013) of protein and lipids in GP that increase hydrogen partial pressure (Fig. 9).

Another bacterium that could play an important role in this microbial community is P. mucosa, also observed at higher abundance in later stages of AD of GP of present investigation (Fig. 8B). Based on integrated omics analyses it was also observed that P. mucosa encoded a diverse set of glycosyl-hydrolyses involved in carbohydrate metabolism (Maus et al., 2020). Under these conditions, it may play an important role in conversion of lignocellulosic biomass and also proteins for subsequent methane production (Maus et al., 2020).

It is noteworthy that GP substrate digestion here described highlights the development of a more diversified bacterial consortium than CG, resulting in a more complex and varied combination of synergistic behaviors. Composition of the starting matrix has an impact on predominant microbial groups present in biogas digesters. Modifications in chemical composition necessitate the involvement of distinct microbial enzymes to break down components like starch, lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose (Nwokolo et al., 2020). Thus, the different chemical compositions of matrices here examined, led to selecting distinct microbial strains, which significantly affected the biogas production results observed between biomasses, results primarily due to lignocellulosic nature of GP. Indeed, this biomass class presents a significant challenge to degradation processes. This is due to a number of factors, including its heterogeneous structure, recalcitrant nature and the limited accessibility of polysaccharides to enzymes, which is primarily due to the presence of lignin (Salehian et al., 2013). In this study, detection of bacteria as Acetomicrobium sp. and P. mucosa, involved in degradation of lipids and protein-rich substrates, together with Methanosarcina sp. and P. bacterium 1109, able to tolerate high hydrogen pressures and high ammonia concentration derived by amino acid degradation, seems to confirm the preference towards more rapidly-fermentable biomass components, as proteins and lipids, rather than lignocellulose. Moreover, in late AD stages, the co-presence here observed of M. bourgensis with P. bacterium 1109, which relative abundance was seen as positively correlated to pH and is able to hydrolyze substrates efficiently even at pH ≥ 7.7, could be indicative of an adapted microbial community (Buettner et al., 2019).

Ultimately, current analyses are based on whole metagenomic shotgun sequencing, a robust method that provides a unique framework for assessing bacterial diversity and detecting the abundance of microorganisms in various environments. Over the past decade, one of the most beneficial outcomes of shotgun metagenomics projects has been the ability to assemble complete or near-complete genomes of high quality, including de novo assembly and binning of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs). In recent years, many thousands MAGs have been reported in literature, for a variety of environments and host-associated microbiota, including humans. MAGs have helped us better understand microbial populations and their interactions with environments where they live; moreover, most MAGs belong to novel species, therefore helping to decrease the so-called microbial dark matter. However, questions about the biological reality of MAGs have not, in general, been properly addressed.

Conversely, these findings pave the ground for creating a tailor-made microbial consortium, which could be inoculated at the beginning of fermentation process to enhance biogas yield during anaerobic digestion of lignocellulosic biomasses.

3.5. Functional profiles characterizing AD dynamics in the two substrates

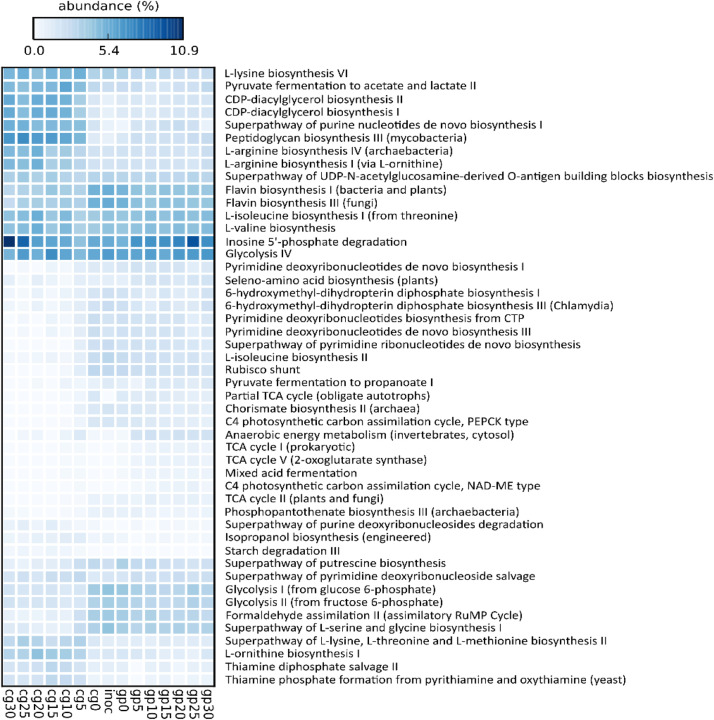

The statistical analysis on the MetaCyc pathways highlighted 48 significant elements, over the 233 identified through HumaNn3 analysis, potentially contributing to the differentiation of AD dynamics between the two substrates. The results of the functional analysis are shown in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Dynamic of functional profiles detected from time 0 to day 30 from both cereal grains (cg0–30), grape pomace (gp0–30) and inoculum. The heatmap shows only the MetaCyc pathways resulted significantly (p < 0.05) enriched across the digestion period in each matrix.

Pathways related to amino acid metabolism, as well as purine and pyrimidine metabolism, were uniformly distributed between the two substrates. Regarding carbohydrate metabolism, the CG group was characterized by a significant enrichment of the starch degradation pathway (p < 0.009), which was essentially absent in the GP group, and by the fermentation of pyruvate to acetate and lactate pathway (p < 0.003).

The presence of these pathways is consistent with the microbial composition of CG, particularly with the presence of Clostridium strains, known for their amylolytic capabilities. These bacteria efficiently degrade starch into fermentable sugars, which are subsequently converted into pyruvate. Under anaerobic conditions, Clostridium species can then ferment pyruvate into lactate and acetate, key intermediates in anaerobic digestion. The production of acetate is particularly relevant as it serves as a crucial substrate for methanogenic archaea, such as Methanobacterium sp. MB1 and M. wolfeii, which rely on acetate and hydrogen to sustain methane production.

Additionally, the enrichment of these fermentation pathways suggests an active microbial network specialized in carbohydrate breakdown and organic acid metabolism, promoting efficient energy conversion in the CG system. This metabolic specialization could be linked to the nature of the CG substrate, favoring a microbial community capable of rapidly utilizing polysaccharides and directing fermentation toward acetate and lactate production, key steps in the overall anaerobic digestion process.

The GP group was characterized by additional carbon metabolism pathways, such as mixed acid fermentation (p < 0.005), pyruvate fermentation to propanoate (p < 0.003), and partial TCA cycle (p < 0.03). The significant presence of these pathways can be directly linked to the previously observed microbial composition and substrate characteristics.

Mixed acid fermentation reflects the diversity of metabolic strategies adopted by GP microorganisms to exploit available resources, particularly through the fermentation of sugars and amino acids, leading to the production of organic acids and gases. In this context, bacteria such as A. hydrogeniformans and A. thermoterrenum, known for their ability to metabolize lipids and proteins, could contribute to the production of acetate, CO₂, and H₂, supporting fermentative and methanogenic processes.

Pyruvate fermentation to propanoate can be attributed to the activity of propionigenic and acetogenic bacterial communities, such as P. bacterium 1109, which is involved in propionate conversion to methane through interactions with M. bourgensis. This process is essential for carbon recycling and system stability, facilitating the availability of precursors for methanogenesis.

Finally, the partial TCA cycle suggests an incomplete yet active metabolic pathway for generating intermediates usable in fermentation and methanogenesis. The co-presence of M. flavescens and M. thermophila, capable of utilizing acetate and other methylated compounds for methane production, highlights the role of these pathways in metabolite balance during the different stages of GP AD. Additionally, the increase in P. mucosa in the later stages may be related to the degradation of complex carbohydrates and proteins, further contributing to fermentative and methanogenic metabolism.

5. Conclusions

Comparing CG and GP substrates with WMS analysis, we identified 15 specific species, detecting some new strains: in GP, showing higher species-complexity, potentially syntrophic interactions between cellulolytic H. saccincola, non-cellulolytic Acetomicrobium sp., and HMs M. bourgensis and Methanosarcina sp. in both early and late AD stages were detected; in CG: the cellulolytic C. isatidis, a Clostridium that could play an important role during early-stage of cellulose degradation in synergy with M. wolfeii was observed. The present study observed the occurrence of cellulolytic strains, such as C. isatidis and H. luporum, alongside hydrogen-producing strains, including Clostridium sp. N3C and C. thermopalmarium. Actually, is well established that these strains commonly inhabit anaerobic digesters that process cellulose-rich substrates, and the results of this study represent a first evidence that these strains have the potential to increase the efficiency of cellulose to hydrogen conversion due to their distinct metabolic capabilities when operating in a synergistic manner. In fact, using cellulolytic bacteria for hydrogen production often results in a low hydrogen yields, due to bacteria's poor growth rates and pH sensitivity and the co-existence of these bacteria with hydrogen producers can overcome this limiting factor.

Our study explores the dynamic of microbiome composition during AD of two renewable resources, demonstrating how its structure varies within different biomasses and fermentation stages. It is important to be aware that the metabolic functions suggested by analyses presented herein are only theoretical. In order to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the metabolic potential of microorganisms during different AD phases, a more detailed molecular analysis of the functions performed by the various microbiomes is required.

It is worth noting, however, the results presented by Basak et al. (2021) that demonstrated a strong correlation between digester performance parameters, in terms of methane production, and the relative abundance of the key mcrA gene quantified by qPCR. At the same time, they also found a strong positive correlation between abundances of archaeal OTUs (Euryarchaeota) and cumulative CH4 production and yield. This study thus establishes a functional relationship between the results obtained from metagenomic analysis and molecular exploration of key genes involved in acidogenic and methanogenic metabolism.

Present analyses are based on whole metagenomic shotgun, a powerful method that provides a unique background for exploring both taxonomic composition and functional potential of different microbial communities. This will permit us to gain a deeper understanding of functional proficiencies of these microorganisms.

Integrating multi-omics approaches into a single framework for studying the biology of complex microbiological systems is a promising approach both for creating more predictable biotechnological applications and for application to understand metabolism, regulation and dynamics of key microbial members in these systems.

Present results constitute an initial effort to identify and develop microbial consortia tailored for degrading various types of substrates in anaerobic digestion (AD) processes in order to try to maximize biogas production efficiency from different organic materials such as from lignocellulosic feedstocks. Creating specialized microbial consortia can significantly increase biogas yield, enhancing overall AD process efficiency as previously demonstrated on maize silage (Poszytek et al., 2016).

Additional files

Supplementary material of this article can be found in online version of the paper.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All the authors have agreed to the publication.

Availability of data and materials

WMS sequencing data has been deposited into public database NCBI, and the BioProject accession number is PRJNA1037512. For revision purposes the data can be accessed through this link to a google drive folder: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1nyHMLj4iQVqiPzPu-b4-7sXmaA1TKF9-?usp=drive_link All metadata available are presented in Table 1

Funding

The study was supported by research grants of the University of Ferrara (Scapoli, FAR 2019-2020; Sabbioni, FAR 2019-20; Tamburini, FAR 2020-21).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nicoletta Favale: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Stefania Costa: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Daniela Summa: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Silvia Sabbioni: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Elisabetta Mamolini: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Elena Tamburini: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Chiara Scapoli: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr. Alberto Carrieri, University of Ferrara, for helping to define all bioinformatics analysis methodologies and for the valuable technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.crmicr.2025.100383.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

WMS sequencing data has been deposited into public database NCBI, and the BioProject accession number is PRJNA1037512

References

- Agbonifo P.E. Renewable energy development: opportunities and barriers within the context of global energy politics. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy. 2021;11:141–148. doi: 10.32479/ijeep.10773. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agregán R., Lorenzo J.M., Kumar M., Shariati M.A., Khan M.U., Sarwar A., Sultan M., Rebezov M., Usman M. Anaerobic digestion of lignocellulose components: challenges and novel approaches. Energies. 2022;15:8413. doi: 10.3390/en15228413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja V., Sharma C., Paul D., Dasgupta D., Saratale G.D., Banu J.R., Yang Y., Bhatia S.K. Unlocking the power of synergy: cosubstrate and coculture fermentation for enhanced biomethane production. Biomass Bioenergy. 2024;180 doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2023.106996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akyol Ç., Ince O., Bozan M., Ozbayram E.G., Ince B. Biological pretreatment with Trametes versicolor to enhance methane production from lignocellulosic biomass: a metagenomic approach. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019;140 doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ale Enriquez F., Ahring B.K. Phenotypic and genomic characterization of methanothermobacter wolfeii strain BSEL, a CO 2 -capturing archaeon with minimal nutrient requirements. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024 doi: 10.1128/aem.00268-24. e00268-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990 doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral. Ecol. 2001;26:32–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9993.2001.01070.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, S., 2010. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data.

- Azman S., Khadem A.F., Van Lier J.B., Zeeman G., Plugge C.M. Presence and role of Anaerobic hydrolytic microbes in conversion of lignocellulosic biomass for biogas production. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;45:2523–2564. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2015.1053727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babu S., Singh Rathore S., Singh R., Kumar S., Singh V.K., Yadav S.K., Yadav V., Raj R., Yadav D., Shekhawat K., Ali Wani O. Exploring agricultural waste biomass for energy, food and feed production and pollution mitigation: a review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022;360 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak B., Ahn Y., Kumar R., Hwang J.-H., Kim K.-H., Jeon B.-H. Lignocellulolytic microbiomes for augmenting lignocellulose degradation in anaerobic digestion. Trends Microbiol. 2022;30:6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2021.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak B., Patil S., Kumar R., Ha G.-S., Park Y.-K., Ali Khan M., Kumar Yadav K., Fallatah A.M., Jeon B.-H. Integrated hydrothermal and deep eutectic solvent-mediated fractionation of lignocellulosic biocomponents for enhanced accessibility and efficient conversion in anaerobic digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2022;351 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak B., Patil S.M., Kumar R., Ahn Y., Ha G.-S., Park Y.-K., Ali Khan M., Jin Chung W., Woong Chang S., Jeon B.-H. Syntrophic bacteria- and methanosarcina-rich acclimatized microbiota with better carbohydrate metabolism enhances biomethanation of fractionated lignocellulosic biocomponents. Bioresour. Technol. 2022;360 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak B., Patil S.M., Saha S., Kurade M.B., Ha G.-S., Govindwar S.P., Lee S.S., Chang S.W., Chung W.J., Jeon B.-H. Rapid recovery of methane yield in organic overloaded-failed anaerobic digesters through bioaugmentation with acclimatized microbial consortium. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;764 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beghini F., McIver L.J., Blanco-Míguez A., Dubois L., Asnicar F., Maharjan S., Mailyan A., Manghi P., Scholz M., Thomas A.M., Valles-Colomer M., Weingart G., Zhang Y., Zolfo M., Huttenhower C., Franzosa E.A., Segata N. Integrating taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling of diverse microbial communities with bioBakery 3. eLife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.65088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Hania W., Bouanane-Darenfed A., Cayol J.-L., Ollivier B., Fardeau M.-L. Reclassification of anaerobaculum mobile, anaerobaculum thermoterrenum, anaerobaculum hydrogeniformans as acetomicrobium mobile comb. nov., acetomicrobium thermoterrenum comb. nov. And acetomicrobium hydrogeniformans comb. nov., respectively, and emendation of the genus acetomicrobium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016;66:1506–1509. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Hania W., Godbane R., Postec A., Hamdi M., Ollivier B., Fardeau M.-L. Defluviitoga tunisiensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a thermophilic bacterium isolated from a mesothermic and anaerobic whey digester. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2012;62:1377–1382. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.033720-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair E.M., Dickson K.L., O'Malley M.A. Microbial communities and their enzymes facilitate degradation of recalcitrant polymers in anaerobic digestion. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021;64:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2021.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Míguez A., Beghini F., Cumbo F., McIver L.J., Thompson K.N., Zolfo M., Manghi P., Dubois L., Huang K.D., Thomas A.M., Nickols W.A., Piccinno G., Piperni E., Punčochář M., Valles-Colomer M., Tett A., Giordano F., Davies R., Wolf J., Berry S.E., Spector T.D., Franzosa E.A., Pasolli E., Asnicar F., Huttenhower C., Segata N. Extending and improving metagenomic taxonomic profiling with uncharacterized species using MetaPhlAn 4. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023;41:1633–1644. doi: 10.1038/s41587-023-01688-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buettner C., Von Bergen M., Jehmlich N., Noll M. Pseudomonas spp. Are key players in agricultural biogas substrate degradation. Sci. Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49313-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanaro S., Treu L., Rodriguez-R L.M., Kovalovszki A., Ziels R.M., Maus I., Zhu X., Kougias P.G., Basile A., Luo G., Schlüter A., Konstantinidis K.T., Angelidaki I. New insights from the biogas microbiome by comprehensive genome-resolved metagenomics of nearly 1600 species originating from multiple anaerobic digesters. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2020;13:25. doi: 10.1186/s13068-020-01679-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayetano R.D.A., Park J.-H., Kim S.-H. Effect of shear velocity and feed concentration on the treatment of food waste in an anaerobic dynamic membrane bioreactor: performance monitoring and microbial community analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2020;296 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarucci A., Bacaro G., Scheiner S.M. Old and new challenges in using species diversity for assessing biodiversity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2011;366:2426–2437. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clesceri L.S., Clesceri L.S., American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, Water Pollution Control Federation . 20. ed. American Public Health Association; Washington, DC: 1998. Standard methods: For the Examination of Water and Wastewater. ed. [Google Scholar]

- Cook L.E., Gang S.S., Ihlan A., Maune M., Tanner R.S., McInerney M.J., Weinstock G., Lobos E.A., Gunsalus R.P. Genome sequence of acetomicrobium hydrogeniformans OS1. Genome Announc. 2018;6 doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00581-18. e00581-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa S., Dedola D., Pellizzari S., Blo R., Rugiero I., Pedrini P., Tamburini E. Lignin biodegradation in pulp-and-paper mill wastewater by selected white Rot fungi. Water (Basel) 2017;9:935. doi: 10.3390/w9120935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Vrieze J., Heyer R., Props R., Van Meulebroek L., Gille K., Vanhaecke L., Benndorf D., Boon N. Triangulation of microbial fingerprinting in anaerobic digestion reveals consistent fingerprinting profiles. Water Res. 2021;202 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desvaux M. Unravelling carbon metabolism in Anaerobic cellulolytic bacteria. Biotechnol. Prog. 2006;22:1229–1238. doi: 10.1021/bp060016e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desvaux M. Clostridium cellulolyticum : model organism of mesophilic cellulolytic clostridia. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005;29:741–764. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewil R., Appels L., Baeyens J. Energy use of biogas hampered by the presence of siloxanes. Energy Convers. Manag. 2006;47:1711–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2005.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinuccio E., Balsari P., Gioelli F., Menardo S. Evaluation of the biogas productivity potential of some Italian agro-industrial biomasses. Bioresour. Technol. 2010;101:3780–3783. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.12.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolfing J. Thermodynamic constraints on syntrophic acetate oxidation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:1539–1541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03312-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du R., Li S., Zhang X., Wang L. [Cellulose hydrolysis and ethanol production by a facultative anaerobe bacteria consortium H and its identification] Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao Chin. J. Biotechnol. 2010;26:960–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyksma S., Jansen L., Gallert C. Syntrophic acetate oxidation replaces acetoclastic methanogenesis during thermophilic digestion of biowaste. Microbiome. 2020;8:105. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00862-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Mashad H.M., Zhang R. Biogas production from co-digestion of dairy manure and food waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2010;101:4021–4028. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri A., Bonifazi G., Serranti S. Micro-scale energy valorization of grape marcs in winery production plants. Waste Manag. 2015;36:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson R.M.W., Coulon F., Villa R. Understanding microbial ecology can help improve biogas production in AD. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;642:754–763. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z., Alshehri K., Li Y., Qian H., Sapsford D., Cleall P., Harbottle M. Advances in biological techniques for sustainable lignocellulosic waste utilization in biogas production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022;170 doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2022.112995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashsham S.A., Fernandez A.S., Dollhopf S.L., Dazzo F.B., Hickey R.F., Tiedje J.M., Criddle C.S. Parallel processing of substrate correlates with greater functional stability in methanogenic bioreactor communities perturbed by glucose. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:4050–4057. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.9.4050-4057.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]