Abstract

Background

Individuals living with long COVID experience a range of symptoms that affect their ability to carry out daily activities or participate in social and community life. This study aimed to analyze association between functional disability and the occurrence of long COVID symptoms, as well as to analyze the effect of symptom persistence time on functional disability.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study using data from the SulCovid-19 study, which interviewed individuals who had COVID-19 between December 2020 and March 2021. The functional disability outcome was assessed using the Basic Activities of Daily Living (BADL) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scales, while the exposures were the symptoms of long COVID. Adjusted analyses between outcomes and exposures, stratified by time after the acute phase of infection, were performed using Poisson regression with robust variance adjustment.

Results

The prevalence of BADL disability was 4.8% (95%CI 4.0;5.6), and for IADL disability, it was 8.4% (95%CI 7.4;9.4). The main symptoms associated with BADL disability were dyspnea, dry cough and sore throat, while for IADL, they were joint pain, muscle pain, loss of sensation, nasal congestion, sore throat and runny nose. When stratified by tertiles of time after the acute phase of infection, a relationship was found between BADL disability and dyspnea, ageusia and, nasal congestion in the 3rd tertile, while only ageusia was found to be related to IADL disability in the 3rd tertile.

Conclusions

Long COVID symptoms were associated wiht limitations in the functional capacity of adults and the seniors. The findings can be used to guide the care and rehabilitation of individuals with disabilities who have had COVID-19, particularly for referral to appropriate health professionals.

Keywords: Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, Functional capacity, Activities of daily living

Introduction

Functional disability is a health indicator that is associated with the presence of chronic diseases, cognitive decline, loss of autonomy and hospitalizations, which is why it has been widely studied [1–4]. Activities of daily living are the measures frequently used to assess functional disability. Its assessment classifies the level of dependence for carrying out daily activities through two different approaches: basic activities of daily living (BADL), which include tasks related to self-care and survival, and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), which indicate the individual’s ability to lead an independent life within the community where they live [2].

Investigation of functional disability occurs predominantly in the seniors population due to its epidemiological relevance [5–9]. The scientific findings are diverse and depend on several factors, such as the age group under investigation, sociodemographic particularities of the sample, presence of morbidities and location of the study [2, 4, 7]. The literature on the subject is extensive, however, in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection, the magnitude of the sequelae produced by the disease at different levels of functional capacity is still under study.

There is extensive literature describing the serious physical effects of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, with studies showing that 70% of those infected may have at least one persistent symptom 60 days or more after diagnosis, onset of symptoms or hospitalization; or 30 days or more after recovery from the acute phase or hospital discharge [10–12]. These circumstances characterize long COVID, which manifests itself through multisystemic disorders that can interfere with health and the ability to carry out functional activities [9, 13].

The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of long COVID are not yet fully understood, but it is believed to involve a combination of immune dysregulation, persistent viral reservoirs, and dysfunction in key physiological pathways. Some individuals experience an exaggerated immune response after the infection resolves, including the persistence of inflammatory markers, such as cytokines, which can lead to chronic inflammation and tissue damage (in the heart, lungs, and brain), contributing to symptoms such as fatigue, difficulty concentrating (“brain fog”), and muscle pain. Another potential mechanism is the continued presence of the virus or its fragments in tissues, leading to viral replication, which could explain persistent symptoms like headaches, fatigue, and neurological deficits [14–15].

Despite advances in knowledge about long COVID and, although there is biological plausibility that justifies functional changes after SARS-CoV-2 infection, there are few studies on the impact of the persistence of symptoms on the population’s ability to perform activities of daily living. Furthermore, it is still unclear whether the time of infection may be associated with changes in functional capacity [16–19]. Therefore, there is a need to understand the possible relationship between functional status and long COVID. The aim of this study was to analyze association between functional disability according to the occurrence of long COVID symptoms and to analyze the effect of symptom persistence time on functional disability.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study with baseline data from the SulCovid-19 Survey, the objective of which was to monitor health indicators in individuals infected with COVID-19. The study was carried out in the city of Rio Grande, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, which is a port city located in the extreme south of Brazil, with an estimated population of almost 213,000 inhabitants [20].

The study participants were individuals aged 18 or over, diagnosed with coronavirus through the RT-PCR test between December 2020 and March 2021, who were symptomatic during the acute phase of infection and received medical care in the municipality of Rio Grande. Participants included individuals from both the public and private healthcare systems; however, participant identification was primarily based on data available from the public healthcare system. Individuals who received treatment in Rio Grande, but were from another city, as well those in the prison system and with severe cognitive limitations that impaired their ability to understand or respond to the questionnaire, were excluded from the study. Cognitive decline, as an exclusion criterion, was specifically defined as the presence of severe cognitive impairment that would prevent individuals from comprehending or adequately responding to the questionnaire. This assessment was conducted by trained interviewers during the data collection process. Individuals who were not found after five telephone contact attempts, one via WhatsApp and three home visits were considered to be losses. The study protocol was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee (CEPAS) of the Federal University of Rio Grande (FURG) (Certificate of Submission for Ethical Appraisal:39081120.0.0000.5324).

In order to identify adults and seniors who had COVID-19 during the period investigated, contact was made with the epidemiological health surveillance service of the city of Rio Grande, creating a list of individuals with positive RT-PCR for COVID-19 and their respective data (name, address, telephone number and presence of symptoms), totaling 4,014 individuals. After excluding those with incomplete telephone and address data, 3,822 were eligible for the study. After preparing the list of individuals eligible for the study, data collection began via telephone calls.

Data collection took place from June 2021 to October 2021, an average of 6.5 months (average 192.8 days) after infection. Electronic questionnaires were used, structured into thematic modules, using the REDCap application. The questionnaires were administered by interviewers, who underwent selection, training and qualification with a total workload of 24 h. The questionnaires took approximately 15–20 min to be answered. In addition to the telephone interviews, home visits were made to collect data in person for those who were afraid to answer the questionnaire by telephone, and for cases where five telephone attempts were unsuccessful. More details about study design and recruitment can be found in Saes et al., (2022) [21].

The outcome of functional incapacity for basic activities of daily living (BADL) was assessed using the Katz scale [22], which identifies limitations in performing the tasks of bathing, dressing, using the toilet, transferring from bed to chair, controlling urination and/or defecation and eating. The response options cover three different levels: does not receive help, receives help, cannot perform alone. Each of the answer options is adapted to the wording of the question.

The functional disability outcome for instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) was assessed using the Lawton and Brody scale [23], which investigates limitations in performing the tasks of using the telephone, using transportation to get around, shopping, preparing one’s own meals, tidying the house, handling small objects and taking medication. The response options quantify the need for help from the following options: no help, partial help and cannot do it alone. For both outcomes, disability was defined based on the response options: receives partial help and/or cannot do it alone for at least one of the items investigated. The outcomes were operationalized as yes/no.

Exposures to long COVID-19 symptoms were assessed using the following question: “Which of these symptoms did you experience after infection with COVID-19?“, with the following answer options: headache, dyspnea, dry cough, cough with phlegm, Shortness of breath, ageusia, anosmia, loss of sensation, fatigue, sore throat, nasal congestion, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, myalgia, arthralgia, memory loss, attention loss and skin changes. All symptoms were self-reported and assessed without the use of a specific validated instrument. To evaluate long COVID symptoms, if the participant answered “yes” to experiencing a symptom during the acute phase, they were asked the follow-up question: “Do you still have this symptom at the moment?“.

Symptoms were also grouped according to the presence of at least one symptom from the respective system: digestive (nausea/vomiting and diarrhea), neurological (headache, memory loss and attention loss), musculoskeletal (myalgia, arthralgia and fatigue/asthenia) and respiratory (dyspnea, dry cough, cough with phlegm, sore throat, nasal congestion) and sensory (ageusia, anosmia and loss of sensation). Long COVID was also operationalized in ordinal form (zero, one, two, three or more symptoms).

The intervening variables were gender (male/female) age (18–59 years/60 years or more) per capita income in the last month in BRL (0-1000/1001–2000/2001–4000/4001 or more), hospitalization due to COVID-19 (no/yes) and presence of at least one morbidity (hypertension, diabetes, osteoporosis, heart problem, eye problem, urinary incontinence, cancer: no/yes). The stratification variable used was the time (in days) after the acute phase of the COVID-19, in tertiles: 1st tertile − 90 to 175 days; 2nd tertile − 176 to 217 days and 3rd tertile − 218 to 277 days.

Descriptive data were presented as proportions and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). The adjusted analyses between outcomes and exposures were carried out using Poisson regression with robust variance adjustment with total outcome and stratified by infection time in tertiles. All associations with a 95%CI without overlap between categories were considered to be statistically significant. After executing the Poisson regression model, multicollinearity was assessed. The data were analyzed using the Stata 16.1 statistical package.

Results

Of the 3,822 adults and seniors eligible for the study, after losses and refusals (631 and 272 respectively), 2,919 subjects were interviewed (76.4% of those eligible). The majority of participants were female (58.6%), aged between 18 and 59 (83.3%), identified as White (77.9%), living with a partner (60.6%), had 9 to 11 years of education (42.2%), reported a monthly income of BRL 1,001 to 2,000 (38.9%), had at least one pre-existing morbidity (65.9%), and had not been hospitalized during the acute phase of the COVID-19 (96.3% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults and the seniors in the SulCovid-19 Study

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1,208 | 41.4 |

| Female | 1,711 | 58.6 |

| Age (n = 2,904) | ||

| 18 to 59 years | 2,420 | 83.3 |

| 60 years or older | 484 | 16.7 |

Mean age ( ±SD) ±SD) |

43.2 | 15.3 |

| Skin color (n = 2,894) | ||

| White | 2,254 | 77.9 |

| Black/Brown/Yellow | 640 | 22.1 |

| Marital status (n = 2,901) | ||

| With a partner | 1,757 | 60.6 |

| Without a partner | 1,144 | 39.4 |

| Years of education (n = 2,963) | ||

| 0 to 8 years | 728 | 25.4 |

| 9 to 11 years | 1,264 | 44.2 |

| 12 years or more | 871 | 30.4 |

| Income (n = 2,555) | ||

| R$0.00 to 1,000.00 | 668 | 26.1 |

| R$1,001.00 to 2,000.00 | 995 | 38.9 |

| R$2,001.00 to 4,00.00 | 604 | 23.7 |

| R$4,001.00 or more | 288 | 11.3 |

| Morbidities (n = 2,822) | ||

| No | 963 | 34.1 |

| Yes | 1,859 | 65.9 |

| Hospitalization due to COVID-19 (n = 2,395) | ||

| No | 2,307 | 96.3 |

| Yes | 88 | 3.7 |

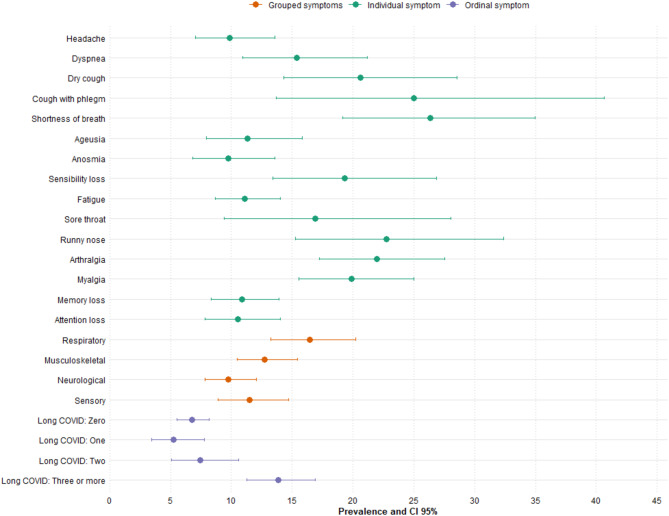

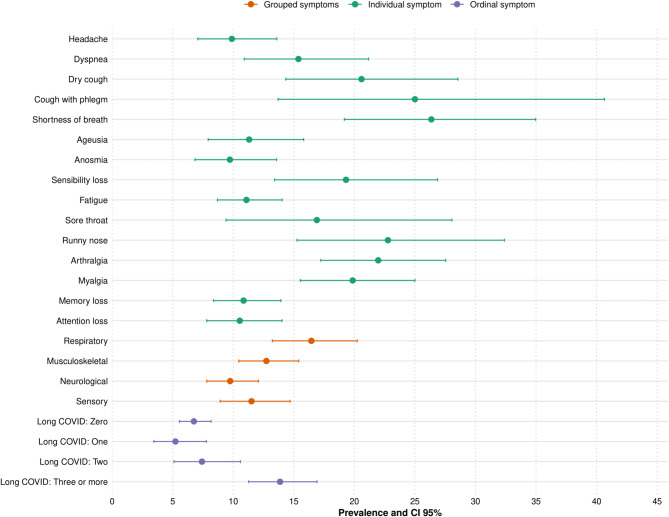

Prevalence of BADL disability was 4.8% (95%CI 4.0;5.6), while IADL disability prevalence was 8.4% (95%CI 7.4;9.4). The most prevalent long COVID symptoms were: fatigue (19.6%; 95%CI 18.3;21.2), memory loss (17.7%; 95%CI 16.5;19.3), attention loss (13.9%; 95%CI 12.7;15.3), headache (11.7%; 95%CI 10.5;12.9), anosmia (11.3%; 95%CI 10.2;12.5) and myalgia (10.1%; 95%CI 9.1;11.3).

Figures 1 and 2 show that the prevalence of functional impairment in BADL was higher among individuals reporting fatigue, myalgia, memory loss, and attention deficits. In IADL, shortness of breath and productive cough also stood out, with prevalences exceeding 30%. In both cases, there was a progressive increase in functional limitations according to self-reported long COVID severity, particularly among individuals with three or more persistent symptoms.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of BADL disability according to the long COVID symptoms

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of IADL disability according to the long COVID symptoms

In the adjusted analysis, a higher probability of disability was identified for BADL among those with individual symptoms such as dyspnea (PR = 2.59 95%CI 1.46;4.57), dry cough (PR = 2.50 95%CI 1.41;4.42), sore throat (PR = 2.67 95%CI 1.08; 6.58), while for IADL the highest probability was for loss of sensation (PR = 1.75 95%CI 1.08;2.85), sore throat (PR = 2.11 95%CI 1.20;3.70), runny nose (PR = 1.77 95%CI 1.18;2.70), nasal congestion (PR = 2.62 95%CI 1.53;4.47), arthralgia (PR = 1.79 95%CI 1.30;2. 46) and myalgia (PR = 1.61 95%CI1.16;2.25), compared to individuals who did not have these symptoms (Table 2).

Table 2.

Disability for BADL and IADL according to individuals symptoms of long covid

| Symptom | BADL | IADL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted* | Crude | Adjusted* | |

| PR (95%CI) | PR (95%CI) | PR (95%CI) | PR (95%CI) | |

| Headache | 1,27 (0,79;2,04) | 1,47 (0,81;2,69) | 1,29 (0,90;1,84) | 1,27 (0.80;2,01) |

| Dyspnea | 2,54 (1,62;3,98) | 2,59 (1,46;4,57) | 1,96 (1,35;1,84) | 1,51 (0.92;2,47) |

| Dry cough | 3,40 (2,11;5,46) | 2,50 (1,41;4,42) | 2,67 (1,80;3,95) | 1,30 (0,78;2,16) |

| Cough with phlegm | 2,41 (0,99;5,89) | 0,87 (0,26;2,92) | 3,08 (1,68;5,63) | 1,32 (0,70;2,49) |

| Shortness of breath | 3,96 (2,51;6,24) | 1,64 (0,85;3,21) | 3,49 (2,43;5,02) | 1,91 (1,24;2,91) |

| Ageusia | 0,98 (0,55;1,73) | 0,70 (0,29;1,64) | 1,40 (0,96;2,04) | 1,31 (0,86;1,99) |

| Anosmia | 0,87 (0,50;1,51) | 0,74 (0,33;1,63) | 1,19 (0,82;1,72) | 1,24 (0,83;1,87) |

| Loss of sensation | 1,63 (0,88;3,01) | 0,97 (0,37;2,53) | 2,47 (1,67;3,67) | 1,75 (1,08;2,85) |

| Fatigue | 1,53 (1,05;2,22) | 1,08 (0,65;1,79) | 1,44 (1,08;1,92) | 1,20 (0,97;1,67) |

| Sore throat | 3,36 (1,82;6,22) | 2,67 (1,08;6,58) | 2,06 (1,15;3,69) | 2,11 (1,20;3,70) |

| Runny nose | 2,40 (1,29;4,43) | 1,12 (0,54;2,36) | 2,92 (1,90;4,50) | 1,77 (1,18;2,70) |

| Nasal congestion | 2,58 (1,39;4,78) | 1,66 (0,84;3,27) | 2,41 (1,49;3,90) | 2,62 (1,53;4,47) |

| Arthralgia | 2,71 (1,81;4,06) | 1,10 (0,64;1,87) | 3,14 (2,34;4,22) | 1,79 (1,30;2,46) |

| Myalgia | 2,53 (1,70;3,77) | 1,60 (0,95;2,66) | 2,82 (2,10;3,79) | 1,61 (1,16;2,25) |

| Memory loss | 1,31 (0,88;1,96) | 0,94 (0,56;1,57) | 1,39 (1,02;1,87) | 1,19 (0,86;1,65) |

| Attention loss | 1,08 (0,68;1,72) | 0,82 (0,43;1,57) | 1,31 (0,95;1,83) | 1,00 (0,67;1,51) |

BADL: Basic Activities of Daily Living. IADL: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. Adjusted for: sex, age, income, hospitalization and morbidity

With regard to grouped symptoms, the highest probability of limitation for BADL was among those with respiratory symptoms (PR = 1.73 95%CI 1.10;2.72), compared to those without these symptoms. For IADL, the highest probability was among individuals with respiratory (PR = 1.76 95%CI 1.29;2.38), musculoskeletal (PR = 1.50 95%CI 1.13;2.01) and sensory (PR = 1.42 95%CI 1.02;1.98) symptoms. There was an up to 80% greater likelihood of IADL disability among all the pairs and trios of symptoms investigated. A greater occurrence of IADL limitations was also identified among those with three or more long COVID symptoms (PR = 1.65 95%CI1.19;2.29), compared to those with no symptoms (Table 3).

Table 3.

Disability for BADL and IADL according to grouped symptoms of long covid

| Variables | BADL | IADL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | |

| PR (95%CI) | PR (95%CI) | PR (95%CI) | PR (95%CI) | |

| Respiratory | 2,71 (1,91;3,86) | 1,73 (1,10;2,72) | 2,40 (1,83;3,16) | 1,76 (1,29;2,38) |

| Musculoskeletal | 1,96 (1,39;2,75) | 1,37 (0,88;2,13) | 1,86 (1,44;2,41) | 1,50 (1,13;2,01) |

| Neurological | 1,31 (0,92;1,87) | 1,02 (0,65;1,62) | 1,29 (0,98;1,69) | 1,18 (0,87;1,61) |

| Sensory | 1,09 (0,71;1,66) | 0,74 (0,40;1,38) | 1,49 (1,11;2,00) | 1,42 (1,02;1,98) |

| Long covid | ||||

| No symptoms | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| One symptom | 0,90 (0,51;1,59) | 0,92 (0,46;1,81) | 0,81 (0,52;1,26) | 1,13 (0,70;1,83) |

| Two symptoms | 1,34 (0,80;2,26) | 0,93 (0,49;1,77) | 1,16 (0,77;1,75) | 1,22 (0,79;1,87) |

| Three or more symptoms | 2,07 (1,40;3,04) | 1,20 (0,74;1,93) | 2,11 (1,58;2,81) | 1,65 (1,19;2,29) |

BADL: Basic Activities of Daily Living. IADL: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. Adjusted for: sex, age, income, hospitalization and morbidity

When stratified by tertile of time after the acute phase of infection, there was a greater magnitude of association between the occurrence of BADL disability and individual symptoms such as dyspnea, ageusia and nasal congestion in the 3rd tertile (218 to 277 days after infection), while for IADL disability only loss of taste showed a greater magnitude in this tertile (Table 4). As for grouped symptoms, individuals in the 2nd tertile (176 to 217 days after infection) with musculoskeletal symptoms (PR = 2.39 95%CI1.18;4.84) and with 3 or more symptoms (PR = 2.45 95%CI1.05;5.69) were more likely to develop BADL disability than those without symptoms (Table 5).

Table 4.

Disability according to symptoms stratified by tertile of time after the acute phase of infection

| Symptom | BADL | IADL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st tertile | 2nd tertile | 3rd tertile | 1st tertile | 2nd tertile | 3rd tertile | ||

| PR (95%CI) | PR (95%CI) | PR (95%CI) | PR (95%CI) | PR (95%CI) | PR (95%CI) | ||

| Headache | 0,67 (0,15;2,98) | 5,04 (1,60;15,9) | 1,04 (0,30;3,64) | 1,98 (0,88;4,46) | 1,15 (0,33;4,01) | 1,04 (0,39;2,75) | |

| Dyspnea | 1,29 (0,29;5,56) | 3,30 (0,93;11,7) | 3,68 (1,06;12,7) | 1,87 (0,72;4,85) | 2,64 (0,90;7,77) | 0,69 (0,15;3,11) | |

| Dry cough | 5,40 (1,73;16,8) | 2,29 (0,61;8,51) | 2,05 (0,60;7,09) | 2,30 (0,78;6,77) | 1,18 (0,33;4,12) | 1,11 (0,33;3,71) | |

| Cough with phlegm | * | * | 1,92 (0,40;9,03) | 0,99 (0,13;7,50) | 2,45 (0,51;11,7) | 0,92 (0,21;4,09) | |

| Shortness of breath | 2,51 (0,71;8,93) | 0,96 (0,12;7,37) | 1,34 (0,30;6,04) | 3,84 (1,63;9,03) | 1,30 (0,30;5,59) | 1,15 (0,35;3,86) | |

| Ageusia | 0,42 (0,06;1,75) | 1,94 (0,72;5,23) | 2,36 (1,25;4,45) | 1,72 (0,87;3,43) | 1,75 (0,89;3,44) | 6,86 (3,80;12,40) | |

| Anosmia | 0,89 (0,22;3,68) | 1,29 (0,43;3,82) | 0,37 (0,05;2,75) | 1,19 (0,59;2,40) | 1,67 (0,76;3,66) | 0,94 (0,37;3,25) | |

| Loss of sensation | 8,85 (4,21;18,61) | 1,24 (1,03;17,4) | 1,30 (0,38;4,42) | 1,94 (0,88;4,26) | 3,70 (1,20;11,4) | 0,76 (0,23;2,54) | |

| Fatigue | 0,93 (0,35;2,44) | 1,30 (0,50;3,34) | 1,28 (0,58;2,85) | 1,71 (0,96;3,07) | 0,94 (0,42;2,07) | 0,82 (0,45;1,50) | |

| Sore throat | 1,36 (0,34;5,34) | 8,25 (2,09;32,5) | 1,06 (0,16;6,95) | 1,03 (0,25;4,26) | 8,36 (3,47;20,14) | 1,37 (0,65;2,87) | |

| Runny nose | 1,21 (0,38;3,87) | 2,64 (0,54;12,89) | 0,89 (0,25;3,15) | 2,93 (1,43;5,99) | 2,06 (0,72;5,86) | 1,31 (0,47;3,65) | |

| Nasal congestion | 1,73 (4,01;7,44) | 2,21 (0,33;14,87) | 2,58 (1,11;5,98) | 4,80 (1,09;11,03) | 2,66 (0,64;11,00) | 1,44 (0,60;3,49) | |

| Arthralgia | 0,58 (0,15;2,24) | 2,24 (0,88;5,67) | 0,96 (0,41;2,25) | 1,72 (0,94;3,15) | 2,20 (1,14;4,22) | 1,35 (0,73;2,47) | |

| Myalgia | 1,69 (0,58;4,91) | 4,85 (2,15;10,83) | 0,60 (0,21;1,74) | 1,31 (0,63;2,73) | 2,25 (1,10;4,58) | 1,05 (0,55;1,99) | |

| Memory loss | 0,73 (0,24;2,20) | 0,95 (0,37;2,44) | 1,02 (0,44;2,39) | 1,38 (0,75;2,53) | 0,93 (0,43;2,00) | 1,24 (0,66;2,31) | |

| Attention loss | 0,60 (0,16;2,27) | 1,28 (0,50;3,29) | 0,31 (0,04;2,25) | 1,13 (0,53;2,44) | 0,93 (0,43;2,03) | 0,86 (0,32;2,29) | |

BADL: Basic Activities of Daily Living. IADL: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. Adjusted for: sex, age, income, hospitalization and morbidity. 1st tertile: 90 to 175 days; 2nd tertile: 176 to 217 days and 3rd tertile: 218 to 277 days. *statistical program did not perform estimates

Table 5.

Disability according to grouped symptoms stratified by tertile of time after the acute phase of infection

| Variables | BADL | IADL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st tertile | 2nd tertile | 3rd tertile | 1st tertile | 2nd tertile | 3rd tertile | |

| PR (CI95%) | PR (CI95%) | PR (CI95%) | PR (CI95%) | PR (CI95%) | PR (CI95%) | |

| Respiratory | 1,89 (0,87;4,09) | 1,94 (0,77;4,86) | 1,78 (0,87;3,62) | 2,57 (1,48;4,46) | 2,03 (1,04;3,98) | 1,31 (0,76;2,28) |

| Musculoskeletal | 1,48 (0,61;3,57) | 2,39 (1,18;4,84) | 1,06 (0,50;2,26) | 0,96 (0,61;1,52) | 1,84 (1,02;3,34) | 0,92 (0,52;1,63) |

| Neurological | 0,55 (0,20;1,50) | 1,48 (0,63;3,47) | 1,06 (0,50;2,26) | 1,66 (0,94;2,92) | 1,06 (0,51;2,23) | 1,19 (0,67;2,12) |

| Sensory | 0,42 (0,10;1,76) | 1,77 (0,69;4,53) | 0,68 (0,22;2,12) | 2,04 (1,16;3,61) | 2,00 (1,00;4,04) | 0,66 (0,28;1,53) |

| Long covid | ||||||

| Without symptom | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| One symptom | 1,34 (0,46;3,94) | 1,01 (0,25;4,13) | 0,41 (0,05;3,15) | 1,92 (0,80;4,58) | 0,99 (0,30;3,26) | 0,98 (0,37;2,58) |

| Two symptoms | 1,39 (0,40;4,79) | 0,88 (0,30;2,53) | 0,93 (0,28;3,16) | 1,64 (0,61;4,46) | 1,48 (0,68;3,23) | 0,92 (0,37;2,29) |

| Three or more symptoms | 0,95 (0,35;2,53) | 2,45 (1,05;5,69) | 1,07 (0,50;2,32) | 2,77 (1,41;5,42) | 2,17 (0,97;4,90) | 0,88 (0,48;1,64) |

BADL: Basic Activities of Daily Living. IADL: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. Adjusted for: sex, age, income, hospitalization and morbidity. 1st tertile: 90 to 175 days; 2nd tertile: 176 to 217 days and 3rd tertile: 218 to 277 days

Discussion

This study assessed the prevalence of functional disability in adults and seniors with long COVID. The individual symptoms associated with BADL disability were dyspnea and dry cough, while for IADL they were loss of sensation, sore throat, runny nose, nasal congestion, myalgia and arthralgia. The grouped symptoms associated with BADL disability were respiratory symptoms, while for IADL they were respiratory, musculoskeletal and sensory symptoms, and the presence of three or more long COVID symptoms was associated with IADL disability. When stratified by tertile of time after the acute phase of infection, there was an association between BADL disability and dyspnea, ageusia and nasal congestion, and between IADL and ageusia in the third tertile.

Prevalence of functional disability for basic and instrumental activities of daily living was lower than that reported in other studies that used the same assessment instruments, but with a sample that was not infected by SARS-CoV-2, since they were studies carried out before the pandemic [5–9]. This finding may be related to the average age of the sample in this study, since most of these surveys were carried out exclusively with seniors. A longitudinal study conducted in China showed that prevalence of BADL disability in the seniors was approximately 11%, with a relative annual increase of 0.12% between the years evaluated, while prevalence of IADL disability was close to 25%, with a relative annual increase of almost 2% [8]. In Brazil, prevalence of BADL functional disability ranged from 8% [9] 36% [5], while for IADL it was close to 45% [7].

Functional capacity governs motor kinetic requirements related to cardiopulmonary and neuromusculoskeletal interrelations [2]. This persistent symptomatology can compromise the homeostasis of these systems in carrying out daily activities [24]. Our findings as to the most frequent symptoms corroborate those of other authors [24, 25], especially in relation to fatigue, which was the most prevalent symptom for both IADL and BADL. Persistent fatigue is common in long COVID and has multifactorial causes, including biological, psychological and environmental factors. The physiological explanation of this process refers to the possibility of coronavirus infection causing a cascade of reactions with repercussions on the metabolism of the central nervous system, which becomes less active, and muscle mitochondrial dysfunction can contribute to its physical dimension [25].

Given the lack of studies on disability in individuals mostly infected with the mild form of COVID-19, it is worth noting that the literature has presented some studies on the subject in hospitalized patients. A multicenter study that included patients admitted to five hospitals in Madrid/Spain, diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection during the first wave of the pandemic, showed that a greater number of symptoms in the acute phase of COVID-19 infection were associated with functional limitations in all activities of daily living [16]. In Brazil, a study of seniors who received post-discharge telemonitoring after COVID-19 showed that individuals hospitalized for COVID-19 have high levels of disability, with 40.3% of the sample having difficulty standing for more than 10 min, 31.1% needing walking aids and 24% having difficulty moving any limb [26].

Many aspects of the pathophysiology and/or health/disease process of COVID-19 have yet to be elucidated. Research into this issue outside of the hospital context, with a focus on the functional disability generated, is still a scientific gap. This circumstance dictates that the discussion of the results be comparative with a clinical context that resembles the symptomatological manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection, which is why we bring up the example of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This disease, like COVID-19, is characterized by lung inflammation and compromises activities of daily living due to dyspnea and musculoskeletal dysfunction [27].

The mechanisms that explain the impact of dyspnea on activities of daily living are complex, but dynamic volume restriction induced by lung hyperinflation and the consequent neuro-mechanical uncoupling of the respiratory system is the most widely accepted hypothesis [28]. With COVID-19, studies have described the occurrence of hyperventilation during exercise, i.e. excessive stimulation of the respiratory center in the brainstem which causes the sensation of air hunger [29, 30], consequently causing impairment to functional activities.

Difficulty in performing activities of daily living due to musculoskeletal pain is already well established in the literature, with the same mechanism as musculoskeletal pain after COVID. Pain has an impact on the quality of life and functionality of these individuals [31–34].

This study carried out stratification based on the time after the acute phase of COVID-19. This longitudinal analysis can mimic both the progression and the resolution of the disease process in question, in this case the persistence of symptomatic components of COVID-19. This approach has already been investigated by other authors. Alkodaymi et al. carried out a meta-analysis with the aim of estimating the prevalence of persistent symptoms at least 12 weeks after acute COVID-19 in different follow-up periods. In these studies, the authors found that the most commonly reported symptoms were fatigue, dyspnea, sleep disturbance and difficulty concentrating (at follow-up of 3 to < 6 months); effort intolerance, fatigue, sleep disturbance and dyspnea (at follow-up of 6 to < 9 months); fatigue and dyspnea (at follow-up of 9 to < 12 months) and fatigue, dyspnea, sleep disturbance and myalgia (at follow-up > 12 months) [35].

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, due to its cross-sectional design, it is not possible to determine whether functional disabilities were present prior to COVID-19 infection. Second, the absence of a control group of individuals not infected with SARS-CoV-2 limits the ability to compare outcomes and draw definitive conclusions about the impact of COVID-19 on functional disability. Third, the study did not account for the possibility of reinfection, as it focused on individuals who tested positive for COVID-19 between December 2020 and March 2021. Although reinfection was rare during this period due to the early stages of the pandemic and limited circulation of immune-evasive variants, it could have influenced symptom persistence and functional disability outcomes. Additionally, other limitations are related to variations not evaluated in this study that may potentially act as confounders (e.g., vaccination status, comorbidities [Chronic kidney disease, liver diseases, and autoimmune diseases], and occupation).

Additionally, the time between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the onset of symptoms was not assessed, and the questions used to evaluate long COVID symptoms may lack sufficient specificity to rule out positive responses due to other causes. To mitigate this potential bias, participants were asked to report only symptoms that persisted after the acute phase of COVID-19, and those with pre-existing conditions that could explain the symptoms were excluded. However, the possibility of misclassification remains a limitation.

Furthermore, while participants included individuals from both the public and private healthcare systems, recruitment was primarily based on data from the public healthcare system. This approach may have introduced selection bias, as individuals seeking care in the private sector might have different characteristics or access to resources that could influence their symptom profiles and functional outcomes.

Lastly, the vast majority of participants were not hospitalized during the acute phase of COVID-19. While this limits the generalizability of our findings to more severe cases, it also highlights the relevance of our study in addressing the long-term effects of COVID-19 in non-hospitalized individuals, a population that has been less studied but represents a significant proportion of those affected by long COVID.

To address these limitations, future studies should incorporate longitudinal follow-up to track the emergence of disabilities post-COVID-19, include control groups for comparison, and collect data on reinfection and healthcare sector representation to better understand their roles in long COVID and functional limitations, particularly as new variants continue to emerge.

However, this study has strengths, as it is the first to report BADL and IADL disability following SARS-CoV-2 infection and analysis of the persistence of symptoms by tertile in non-hospitalized individuals in Brazil. In addition, the outcome was measured using scales validated in the literature.

Conclusion

The symptoms associated with BADL disability were dyspnea, dry cough and respiratory symptoms. For IADL, they were loss of sensation, sore throat, runny nose, nasal congestion, arthralgia, myalgia and respiratory, musculoskeletal and sensory symptoms, and individuals with 3 or more symptoms. Regarding the infection time tertile, there was association between BADL disability and dyspnea, ageusia and nasal congestion, and IADL disability and ageusia in the third tertile evaluated. This data can be useful for guiding the care/rehabilitation of individuals with disabilities who have had COVID-19, and for referring them to the appropriate professionals.

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out with the support of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel– Brazil (CAPES)– Financing Code 001.

Author contributions

B.P.N., S.M.S.D. and M.O.S. conceptualized the study, analysed the data, and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. Y.P.V. and L.N.S. analysed the data, and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. D.G., L.C., Y.B., J.B., and T.N.G. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Rio Grande do Sul State Research Foundation (FAPERGS), grant number 21/2551-0000107-0.

Data availability

The dataset used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was carried out in accordance with the precepts of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Nuremberg Code, respecting the Standards for Research Involving Human Beings. In compliance with Resolution No. 466, of December 12, 2012, of the National Health Council - CNS, which includes the Guidelines and Regulatory Norms for Research involving human beings, Ethics approval and consent to participate. Ethical approval was secured from the Federal University of Rio Grande– FURG (Opinion: 4.375.697/ CAAE: 39081120.0.0000.5324. The participants were provided with detailed information on the research, including its objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Additionally, they were informed about their right to withdraw from the study at any time without repercussion. All participants agreed to participate in the study, and provided verbal or written consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bleijenberg N, Zuithoff NPA, Smith AK, de Wit NJ, Schuurmans MJ. Disability in the individual ADL, IADL, and mobility among older adults: A prospective cohort study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21:897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campos ACV, de Almeida MHM, Campos GV, Bogutchi TF. Prevalence of functional incapacity by gender in elderly people in Brazil: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol. 2016;19:545–59. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castro DC, Nunes DP, Pagotto V, Pereira LV, Bachion MM, Nakatani AYK. Incapacidade funcional Para atividades básicas de Vida diária de Idosos: Estudo populacional/functional disability for basic activities of daily lives of the elderly: a population study < b>. Ciência, Cuidado e Saúde. 2016;15:109–17.

- 4.Pashmdarfard M, Azad A. Assessment tools to evaluate activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) in older adults: A systematic review. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2020;34:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farías-Antúnez S, Lima NP, Bierhals IO, Gomes AP, Vieira LS, Tomasi E. Incapacidade funcional Para atividades básicas e instrumentais Da Vida diária: Um Estudo de base populacional com Idosos de Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, 2014. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2018;27:e2017290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliveira A, Nossa P, Mota-Pinto A. Assessing functional capacity and factors determining functional decline in the elderly: A Cross-Sectional study. Acta Med Port. 2019;32:654–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinto AH, Lange C, Pastore CA, de Llano PMP, Castro DP, dos Santos F. Capacidade funcional Para atividades Da Vida diária de Idosos Da estratégia de Saúde Da Família Da Zona rural. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2016;21:3545–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan M, Qin T, Yin P. Disabilities in activities of daily living and in instrumental activities of daily living among older adults in China, 2011–15: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394:S82. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veloso MV, Sousa NF, da Medina S, de PB L, de Barros MB. Income inequality and functional capacity of the elderly in a City in southeastern Brazil. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2020;23:e200093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Y-M, Shang Y-M, Song W-B, Li Q-Q, Xie H, Xu Q-F, et al. Follow-up study of the pulmonary function and related physiological characteristics of COVID–19 survivors three months after recovery. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25:100463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, et al. Post-acute COVID–19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27:601–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boaventura P, Macedo S, Ribeiro F, Jaconiano S, Soares P. Post-COVID–19 Condition: Where Are We Now? Life (Basel). 2022;12:517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Liu Y, Gu X, Li H, Zhang H, Xu J. Mechanisms of long COVID: an updated review. Chin Med J Pulm Crit Care Med. 2023;1(4):231–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gheorghita R, Soldanescu I, Lobiuc A, Sturdza OAC, Filip R, Constantinescu-Bercu A, Dimian M, Mangul S, Covasa M. The knowns and unknowns of long COVID-19: from mechanisms to therapeutical approaches. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1344086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Martín-Guerrero JD, Navarro-Pardo E, Rodríguez-Jiménez J, Pellicer-Valero OJ. Post-COVID functional limitations on daily living activities are associated with symptoms experienced at the acute phase of SARS-CoV–2 infection and internal care unit admission: A multicenter study. J Infect. 2022;84:248–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asadi-Pooya AA, Akbari A, Emami A, Lotfi M, Rostamihosseinkhani M, Nemati H, et al. Risk factors associated with long COVID syndrome: A retrospective study. Iran J Med Sci. 2021;46:428–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nasserie T, Hittle M, Goodman SN. Assessment of the frequency and variety of persistent symptoms among patients with COVID–19: A systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2111417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pun BT, Badenes R, Heras La Calle G, Orun OM, Chen W, Raman R, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for delirium in critically ill patients with COVID–19 (COVID-D): a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:239–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Cidades e Estados - Rio Grande. https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/rs/rio-grande/panorama. Accessed 1 Apr 2024.

- 21.Saes M, de Rocha O, Rutz JQS, Silva AAM, Camilo CN, de Oliveira L et al. Aspectos metodológicos e resultados da linha de base do monitoramento da saúde de adultos e idosos infectados pela covid–19 (Sulcovid–19). 2023.

- 22.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW, STUDIES OF ILLNESS IN THE AGED. THE INDEX OF ADL: A STANDARDIZED MEASURE OF BIOLOGICAL AND PSYCHOSOCIAL FUNCTION. JAMA. 1963;185:914–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma P, Bharti S, Garg I. Post COVID fatigue: can we really ignore it? Indian J Tuberc. 2022;69:238–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castanares-Zapatero D, Chalon P, Kohn L, Dauvrin M, Detollenaere J, de Maertens C et al. Pathophysiology and mechanism of long COVID: a comprehensive review. Ann Med. 2022;54:1473–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Leite VF, Rampim DB, Jorge VC, de Lima MdoCC, Cezarino LG, da Rocha CN, et al. Persistent symptoms and disability after COVID–19 hospitalization: data from a comprehensive telerehabilitation program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102:1308–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones PW. Activity limitation and quality of life in COPD. COPD. 2007;4:273–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Donnell DE, Laveneziana P. Dyspnea and activity limitation in COPD: mechanical factors. COPD. 2007;4:225–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aparisi Á, Ybarra-Falcón C, García-Gómez M, Tobar J, Iglesias-Echeverría C, Jaurrieta-Largo S, et al. Exercise ventilatory inefficiency in Post-COVID–19 syndrome: insights from a prospective evaluation. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wirth KJ, Scheibenbogen C. Dyspnea in Post-COVID syndrome following mild acute COVID–19 infections: potential causes and consequences for a therapeutic approach. Med (Kaunas). 2022;58:419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stamm TA, Pieber K, Crevenna R, Dorner TE. Impairment in the activities of daily living in older adults with and without osteoporosis, osteoarthritis and chronic back pain: a secondary analysis of population-based health survey data. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weldam SW, Lammers J-WJ, Decates RL, Schuurmans MJ. Daily activities and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: psychological determinants: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woo J, Leung J, Lau E. Prevalence and correlates of musculoskeletal pain in Chinese elderly and the impact on 4-year physical function and quality of life. Public Health. 2009;123:549–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lemos B, de O, Cunha AMR, Cesarino CB, Martins MRI. The impact of chronic pain on functionality and quality of life of the elderly. BrJP. 2019;2:237–41. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alkodaymi MS, Omrani OA, Fawzy NA, Shaar BA, Almamlouk R, Riaz M, et al. Prevalence of post-acute COVID–19 syndrome symptoms at different follow-up periods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28:657–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.