Abstract

Background

Social, emotional and behavioural (SEB) problems are among the most common chronic disabilities affecting children growing up in poverty. They also have implications for children’s school success as they affect essential social-emotional learning skills such as the ability to comply with rules, regulate emotions and get along with others. These skills are first learnt before kindergarten, in the context of a supportive, responsive and consistent parenting relationship. To date, school-based interventions to improve young children’s SEB competence and learning have primarily targeted students and teachers. Yet, parents are central partners in promoting these skills. This study seeks to improve children’s SEB competence and kindergarten readiness by strengthening parenting skills and parent engagement in early childhood education during prekindergarten (PreK). This hybrid type 2 effectiveness-implementation trial will rigorously evaluate the effects of an evidence-based parenting programme, the Chicago Parent Program (CPP), in PreK on children’s SEB competence, kindergarten readiness, chronic school absenteeism and grade retention in urban and rural schools serving students from low-income families in Maryland.

Methods

Using a cluster randomised design (n=30 schools, 840 parents; >90% low-income), we will examine the effects of CPP offered universally to PreK parents on parenting skills and parent engagement in children’s education; children’s SEB competence and kindergarten readiness; and chronic absence and grade retention in kindergarten. Schools will be stratified by rural versus urban district, then randomised to CPP or usual practice conditions. Data will be analysed using mixed effects regression models. Using the reach, effectiveness-adoption, implementation, maintenance (RE-AIM) framework and a mixed methods approach, we will assess CPP reach, efficacy, acceptability, adoption, implementation, cost-effectiveness and sustainability when offered in different formats (virtual vs in-person CPP groups) and contexts (urban vs rural). Schools will participate for 2 years with experimental schools offering CPP twice, once in virtual group format and once in an in-person group format (format randomised and counterbalanced). Data will be collected using multiple informants (parents, teachers, district administrative data) and methods (quantitative and qualitative data). Knowledge gained will inform schools in under-resourced urban and rural communities on sustainable, cost-effective strategies for strengthening parent-school connections and improving young children’s SEB competence and academic success.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval has been granted by Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (protocol number 00428221) and the Baltimore City Public Schools (protocol number 2024-013). At the conclusion of the study, results will be summarised and shared with parents, teachers, school principals and district leaders for their perspectives on the outcomes. Final reports will be published in scientific journals and presented at professional meetings.

Trial registration number

Keywords: randomized controlled trial, child, mental health, community child health, parents

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The trial uses a hybrid type 2 effectiveness-implementation design to rigorously test a brief group-based parenting skills programme called the Chicago Parent Program in urban and rural school districts.

The study will compare the strengths and limitations of offering group-based parenting skills programmes virtually versus in-person.

The trial design requires intervention schools to implement the parenting intervention in the Fall term, which is a challenging time for schools to initiate a new programme and may affect recruitment and fidelity.

Background

Social, emotional and behavioural (SEB) problems are among the most common chronic disabilities affecting children in the USA, and they are more than twice as likely to occur among children living in poverty.1 2 SEB problems have implications for children’s kindergarten (K) readiness as they affect essential skills for learning, such as the ability to follow instructions, comply with rules, regulate emotions, solve problems, organise and complete tasks and get along with others. Children who enter K without these skills are also more likely to be chronically absent from school (defined as missing at least 10% of school days) and retained in grade.3 4 Long-term, children with SEB problems are more likely to experience myriad difficulties affecting their mental and physical health, quality of life and economic self-sufficiency.5 6 Indeed, given the significance of K readiness and chronic absenteeism for lifelong health, these two outcomes have become important indicators of child health.7 8

The foundation for SEB skills begins early, before children enter K, in the context of a supportive, responsive and consistent parenting relationship.9 10 To date, universal school-based interventions to improve young children’s SEB skills and social-emotional learning have primarily targeted students and teachers.11 12 Yet, parents are the central figures in young children’s lives.13 Therefore, parents need to be equal partners with schools in promoting these skills. Indeed, a critical lesson learnt from the COVID-19 pandemic is that teachers cannot educate children, especially young children, without strong partnerships with parents.14

To improve children’s SEB skills, a number of schools located in underserved communities in Maryland have been implementing an evidence-based parenting programme called the Chicago Parent Program (CPP).15 16 Although there is substantial evidence demonstrating CPP’s effectiveness for improving parenting skills and children’s externalising behaviour,17,19 its effects on parent engagement in children’s education and early academic outcomes have not been rigorously evaluated despite the programme’s popularity in public schools. This hybrid type 2 effectiveness-implementation trial will evaluate the effects of CPP implemented in prekindergarten (PreK) versus usual practice on parent engagement in PreK and K outcomes in title 1 urban and rural schools serving low-income students.

The Chicago Parent Program

CPP is a 12-session group-based parenting programme for caregivers of young children aged 2–8 years. Validated in multiple clinical trials conducted in urban, predominantly low-income communities, CPP has led to significant improvements in parents’ use of positive parenting skills, and reductions in parents’ use of corporal punishment and in children’s behaviour problems across home and school settings.17,19 The programme is guided by two theories: social learning theory,20 which posits that parents are powerful models and reinforcers of their children’s behaviour; and attachment theory,21 which highlights the centrality of stable, responsive and nurturing adults in children’s lives. Developed in 2002 with an advisory board of parents in Chicago,22 CPP was specifically designed to ensure relevance for families living in underserved communities. CPP uses a detailed Group Leader Manual; over 130 brief video vignettes of real families from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds managing common, often challenging, situations at home and in public settings; a narrator who standardises session content; role play and group activities; weekly skill-building practice assignments and weekly handouts. CPP group leaders help parents clarify their parenting goals, facilitate group discussion and problem-solving among parents, support parents in tailoring strategies to achieve their goals and build support and connections among parents. All CPP group leaders must complete a 14-hour training workshop and pass a post-test prior to implementing the programme. To increase CPP accessibility in low-resource settings, CPP group leaders are only required to have a high school diploma or equivalent to enrol in the training workshop. The programme is available in English and Spanish.

In a quasi-experimental study of PreK students in 12 Baltimore City Public Schools whose parents participated in CPP from 2014 to 2017 (n=332), no differences were found in K readiness scores, chronic absence rates or grade retention relative to children enrolled in the district whose parents did not participate in CPP (n=11 996).23 Yet, all 12 study schools wanted to continue using CPP after the study ended, and more urban and rural schools in Maryland sought to adopt CPP. To understand the programme’s popularity despite these null effects, the research team interviewed district leaders and school-based staff who had been using CPP. All described observing or hearing about positive changes in children’s behaviour and in parents’ levels of engagement with teachers and the school. Although CPP was intended to be offered universally to all interested PreK parents, school staff described selectively encouraging some parents to enrol based on personal challenges they knew parents were having or whose children were struggling with classroom behaviour. This finding highlighted a selection bias that could account for the null effects but could not be controlled without a randomised design. The present study uses a more rigorous research design to assess and control for baseline differences in parents’ and teachers’ reports of children’s SEB competence and other family level differences that may affect children’s behaviour and school outcomes.

Parent engagement in early childhood education

Parent engagement is a process in which schools and parents (defined broadly to include multiple caregivers in children’s lives) work together to support children’s learning, developmental well-being and potential for school success.24 It is a broad and complex construct that includes home-based learning activities such as reading to children, establishing routines, holding high expectations for children’s learning and behaviour and supporting problem-solving skills, all topics discussed in the CPP curriculum. Parent engagement also includes establishing trust and two-way communication between parents and school staff.25 26 A premise underlying this study is that when schools meaningfully invest in supporting parents, parents will be more likely to partner with teachers and other school staff in supporting their children’s education and regular attendance. In prior research, 94% of parents participating in school-based CPP groups (68% Black or African-American, 24% Latino; 88% reporting low or very low incomes) reported that having CPP available to them made them ‘feel valued’ by the school; 80% reported they would be ‘much more’ likely to attend other programmes at their child’s school.27

Parent engagement is particularly critical during the early years because parents determine whether and how their children will be exposed to positive and enriching learning opportunities.28 Parents also determine whether their young children will attend school.29 This study will test (a) the effects of CPP in PreK for improving parent engagement in their children’s education, children’s SEB competence at home and in the classroom and academic outcomes in K (ie, K readiness, chronic absence and grade retention in K). It will also test whether parent engagement in PreK mediates the relationships between CPP participation and academic outcomes in K to better understand the role of parent engagement in early learning.

Efficacy of virtual versus in-person CPP formats

In response to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic, many schools that had been offering CPP continued to do so but transitioned from in-person to virtual formats using Zoom. Results of this change appeared to be positive; group leaders reported that virtual CPP groups were feasible and acceptable to their families and the virtual format eliminated barriers previously encountered with in-person groups. These barriers include finding space in their already overcrowded schools, arranging for refreshments and childcare during group sessions and engaging homebound parents caring for other family members or who lacked reliable transportation. Parent attendance in virtual CPP groups was also high; over 90% of enrolled parents attended at least one session and 63% attended all 12 sessions.30 However, it is unclear whether virtual formats differ in their effectiveness, reach, acceptability, cost and sustainability. Format differences may have particular relevance for families in rural settings where they may live further from their child’s school but have less access to high-speed internet relative to those in urban settings.31 Using the RE-AIM framework,32 33 we will compare CPP reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, cost-effectiveness and sustainability in urban and rural schools when parent groups are implemented virtually (using Zoom) vs in-person (in schools).

An important strength of group-based parenting programmes lies in the sense of belonging and social connection they create among parents by revealing and normalising everyday struggles; exchanging knowledge and information among parents who have a range of strengths, skills and psychosocial risk and reducing isolation.30 These benefits are particularly profound for parents who are single and have low incomes, many of whom feel isolated and unsure of themselves and may not feel they have the ‘right’ social capital to advocate for their children’s education.34 35 This study will examine the extent to which CPP groups generate a sense of belonging and connection among parents participating in the CPP groups and whether those feelings vary by virtual vs in-person formats.

Conditional cash transfers

Participation rates in parenting programmes are typically low, particularly in communities struggling with multiple adversities.36 37 Low parent participation rates limit programme reach and increase programme delivery costs, making them hard to sustain in low-resource settings.38 Based on the principles of behavioural economics, conditional cash transfers (CCTs) use cash incentives to strategically ‘nudge’ families with very limited incomes to invest ‘in the human capital of their children’.39 Since 2014, Baltimore City schools have been using a CCT programme to boost parent participation rates in CPP. Parents receive a bank debit card at enrolment (one card per family). Money is electronically transferred onto their card within 48 hours for each parent group attended (US$15) and for each skill-building practice assignment completed (US$5).40 We will continue this practice and assess the cost and impact of CCTs on CPP participation.

Theory of change

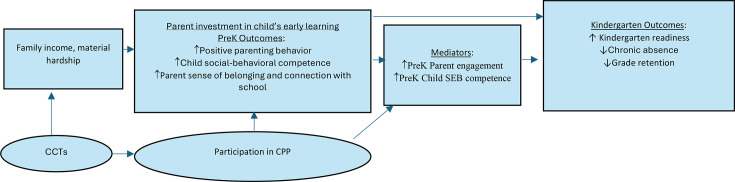

The theory underlying this study is based on the Parent Investment in Early Childhood Model.41 42 According to this model, poverty and material hardship can have negative effects on parents’ abilities to invest in activities and resources that enrich their children’s SEB and learning and their connection with their child’s school. Both problems can adversely affect parent engagement and their commitment to their child’s regular school attendance in K. Chronic absence and low SEB skills make it more difficult for children to learn and increase the likelihood of children being retained in grade in K.

We hypothesise that CPP will support parents’ investments in their children’s early learning through multiple strategies. First, CPP teaches parenting skills demonstrated to promote children’s SEB competence. These skills are taught in the context of a supportive group format, facilitated by trained group leaders from their child’s school. Second, group leaders facilitate parents’ learning from one another, creating a sense of belonging and connection among parents at the same school. Third, CPP communicates to parents that schools are invested in them and in building their social capital, which promotes parent engagement, investment in their children’s education and their children’s regular attendance.43 Finally, parents’ greater skill in supporting their children’s SEB competence and increased engagement in their children’s learning will promote K readiness and reduce the likelihood of children being chronically absent and retained in K. The theory of change guiding this study is represented in figure 1.

Figure 1. Theory of change. CCT, conditional cash transfer; CPP, Chicago Parent Program; PreK, prekindergarten; SEB, social, emotional and behavioral.

Methods/Design

Study design

This study uses a hybrid type 2 effectiveness-implementation design44 to test the effectiveness of CPP (implemented virtually or in-person) compared with usual practice in 30 title 1 urban and rural schools in Maryland (n=840 PreK parents in 60 clusters). Intervention schools will offer CPP twice over 2 years in the Fall term, once virtually and once in-person.

Randomisation is at the school level and attempts to balance the two groups on size, the percent of low-income students and the racial/ethnic distribution reported for each school. School districts are first stratified by urban (Baltimore City, Maryland, n=19 schools) or rural (Cecil County, Maryland, n=11 schools) district. Within rural and urban strata, schools were ordered by size and then randomised to intervention or usual practice using a computer-generated randomisation sequence with a block size of two. Schools that are randomised to the intervention are then randomised to format order with a block size of two to reduce order effects and potential bias associated with schools gaining more experience using CPP. Parents and school staff will not be blinded to allocation due to the nature of the intervention.

Three effectiveness aims and one implementation aim will be evaluated in this study.

Aim 1: test the effects of CPP during PreK for improving children’s SEB competence, parent engagement in early education and parenting skill. H1: relative to usual practice, CPP parents will have greater parent engagement in PreK and more positive parenting skills; CPP children will exhibit improved SEB competence in PreK; these effects will be maintained in K.

Aim 2: test the effects of CPP during PreK for improving children’s school outcomes in K. H2: relative to usual practice, CPP children will score higher on K readiness and be less likely to be chronically absent and retained in grade in K.

Aim 3: examine mechanisms by which CPP improves school outcomes. H3a: PreK postintervention parent engagement will mediate relationships between CPP participation and chronic absence in K. H3b: PreK post-intervention SEB competence will mediate the relationship between CPP participation and K readiness and being retained in grade in K.

Aim 4: guided by the RE-AIM framework, evaluate CPP’s reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, cost-effectiveness and sustainability in schools when implemented in different formats (virtually vs in-person) and contexts (urban vs rural school districts).

Study population

Eligible schools must be located in Baltimore City (an urban school district) or Cecil County (a rural county school district) in Maryland, and be designated as either a title 1 or community school—indicating that at least 40% of the students are from low-income families—or be located in a community designated as high need by the Maryland State Department of Education, based on a score of 0.6 on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Social Vulnerability Index.45 Schools must also have at least one full-day PreK classroom of at least 20 students and have not previously offered CPP in their school.

Principals must agree to their school being randomised and to participating for 2 years in their assigned condition. If randomised to the intervention condition, they must commit at least two staff members to be trained in CPP and to implementing CPP groups in the Fall term of each year. If randomised to the usual practice condition, they must commit to not offering CPP groups in their school for 2 years. To ensure that principals are able to make an informed decision, the study team developed a written description of the study purpose and design. Written in plain language, the document describes the resources the study team will provide to the school to support successful implementation (eg, provide CPP training and materials, manage research consents and data collection, provide incentives). It also includes a list of what each school will need to provide to ensure the success of the study (eg, identify two staff members to complete CPP training and lead CPP groups, allow study team access to PreK families for recruitment, provide space in their school for in-person CPP groups; documents are available from the authors on request).

Schools will be recruited in two waves with approximately half of schools enrolled before the Fall 2024 term (n=16) and the remainder recruited before the Fall 2026 term (n=14). Given the smaller number of rural schools meeting eligibility criteria, more urban than rural schools will be enrolled in the study to meet recruitment targets.

Parent inclusion criteria are: (a) being an English-speaking or Spanish-speaking parent, grandparent or legal guardian of a child aged 4–5 years enrolled in the participating school’s PreK programme, (b) being at least 18 years of age, (c) allowing the study team access to their child’s school ID number and administrative data (ie, attendance, K readiness scores, grade retention) and (d) not having previously participated in CPP. Only one child per parent may be enrolled in the study.

Teacher inclusion criteria include being a PreK or K classroom teacher of a student of a participating parent and consenting to completing study surveys. Teachers who also participate as a parent in a CPP group or as a CPP group leader will be excluded from participation.

Inclusion criteria for CPP group leaders are: (a) completing the CPP group leader training, (b) agreeing to lead CPP groups, (c) being able to speak English or Spanish, (d) having at least a high school diploma or General Equivalency Diploma, (e) consenting to completing surveys and submitting audio-recorded CPP sessions for fidelity monitoring.

School-based personnel inclusion criteria include being a principal, teacher or other school-based staff member involved in CPP implementation and consenting to being interviewed on their perspectives about CPP in the school. School-based staff members who are also enrolled as a study parent will be excluded.

Data safety and monitoring will be managed by a committee of the study investigators, consistent with this study’s overall minimal risk profile. The committee will meet monthly to monitor participant recruitment and retention, adequacy of randomisation procedures, adherence to the intervention protocols and overall quality of CPP implementation, data completeness and serious adverse events (ie, participant death, hospitalisation or life-threatening event). Serious adverse events will be reported to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) within three working days, per the IRB policy. Given the minimal risk of the study, there are no planned interim analyses.

Variables and measures

The study uses multiple measures and informants (parents, teachers, school district administrative data) to assess study outcomes. Data will be collected at five timepoints: PreK baseline (T1), PreK postintervention or 4–5 months postbaseline (T2), end of PreK or 7–8 months postbaseline (T3), Fall of K (T4) and end of K (T5). All parent measures are available in English and Spanish. Primary outcomes include children’s SEB competence reported by teachers and parents, parent engagement, K readiness—social-behavioural domain, chronic absence in K and being retained in K. Secondary outcomes include parenting skills, school community cohesion and overall K readiness (includes language and literacy skills, math skills and physical well-being and motor development). Table 1 summarises the study variables, measures, informants and data collection schedule for addressing aims 1–3. Table 2 lists the qualitative and quantitative data that will be collected to address aim 4.

Table 1. Effectiveness aims, variables, measures, informants and data collection schedule.

| Variable | Measures | Informant(s) | Data collection schedule* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcomes | |||

| SEB† competence | Social Competence and Behaviour Evaluation | Parent, teacher | T1, T2, T3, T4‡ |

| Eyberg Child Behaviour Inventory | Parent | T1, T2, T3, T4 | |

| Parent engagement in early childhood education | Parent-Teacher Involvement Questionnaire | Teacher | T1, T2, T3, T4‡ |

| Parent Engagement in Early Childhood Education | Parent | T1, T2, T3, T4 | |

| Kindergarten social-behavioural readiness | KRA | District Administrative Data | T4 |

| Chronic absence | Chronic absence | District Administrative Data | T5 |

| Retained in grade | Grade retention | District Administrative Data | T5 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Parenting skill | Parenting Questionnaire | Parent | T1, T2, T3, T3 |

| Community school cohesion | School Community Cohesion | Parent | T1, T2, T3, T4 |

| Overall kindergarten readiness | KRA total score | District Administrative Data | T4 |

| Control variables | |||

| Demographic background | Developed by investigators | Parent, teacher | T1, T4‡ |

| Income and Economic Hardship Index | Developed by investigators | Parent | T1, T4 |

| School-based involvement activities | Developed by investigators | Parent | T2, T3 |

T1=baseline assessment (Fall of PreK), T2=4–5 months postbaseline or postintervention for intervention group, T3=8 months postbaseline (end of PreK), T4=12 months postbaseline assessment (Fall kindergarten), T5=end of kindergarten.

SEB competence=child’s SEB competence.

Teacher data collected from child’s PreK teacher at T1, T2 and T3; teacher data collected at T4 is from child’s kindergarten teacher.

KRA, Kindergarten Readiness Assessment; SEB, social, emotional and behavioural.

Table 2. Implementation constructs, variables, measures and data collection timepoint*.

| RE-AIM component | Variables and measures | Data collection |

|---|---|---|

| Reach: characteristics of parent participation in CPP |

|

Following T1T1T1 |

| Effectiveness: evaluation of CPP effectiveness from multiple stakeholder perspectives |

|

End of studyT2Following T2 |

| Adoption: extent to which CPP could be successfully integrated into the school |

|

Following T2End of school participation |

| Implementation: assessment of the quality and consistency of CPP delivery |

|

T2T2T2During CPP implementation |

| Maintenance: likelihood of schools being able to sustain CPP |

|

T2End of studyEnd of studyT2End of school participation |

All implementation outcomes will be compared by rural versus urban school districts and CPP format.

CPP, Chicago Parent Program; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Primary outcomes

Children’s SEB competence is defined broadly as children’s abilities to regulate behaviour and emotions, comply with rules, get along with other children and adults, and cooperate in classroom and family contexts. Teachers and parents will each complete the Social Competence and Behaviour Evaluation (SCBE), a 30-item Likert-type scale with three subscales assessing children’s social competence, anger/aggression, and anxiety/withdrawal. SCBE validity and sensitivity to parent-focused intervention have been supported in prior research.46,48 Parents will also complete the 36-item Eyberg Child Behaviour Inventory, a standardised validated measure of children’s externalising behaviour problems demonstrated to detect change in children’s externalising behaviour following brief parenting interventions, including CPP.49

Parent engagement in their children’s education will be assessed by parents and teachers. Parents will complete the Parent Engagement in Early Childhood Education (PEECE) Survey, a 25-item measure of parent engagement in early learning designed for use in low-income parent populations.50 The PEECE Survey includes three subscales measuring the extent to which parents know what their child is learning and hold high expectations for learning, their trust and communication with their child’s school and teacher and the extent to which they are engaged in learning activities at home. PEECE scores have been positively associated with children’s social-behavioural readiness in K and negatively associated with school absenteeism in K. Teachers will complete the 7-item Parent-Teacher Involvement Questionnaire (PTIQ) assessing their perceptions of the quality of the parent’s relationships with the teacher and the school and of the parent’s support of the child’s education. Previous research using the PTIQ has demonstrated its significant associations with children’s reading achievement and academic functioning.51 52

K readiness—social-behavioural readiness will be assessed using the Kindergarten Readiness Assessment V.2.0 (KRA).53 54 The KRA is a statewide assessment providing information about children’s readiness for learning in K along with four domains: language/literacy, math, physical well-being/motor development and social-behavioural readiness. The KRA is assessed for all students in Baltimore City and Cecil County school districts within the first 45 days of school. The social-behavioural domain includes 12 observable teacher-rated items aligning with essential skills for children’s social-behavioural readiness to learn. Although we are particularly interested in social-behavioural readiness (primary outcome), we will also examine the effects of CPP on all KRA domain scores (secondary outcome), as they tend to be inter-related and interdependent.

Chronic absence and grade retention in K will be obtained annually from district administrative records. Grade retention is defined as being retained for another year of K; chronic absence is defined by the Maryland State Department of Education as a student missing >10% of school days in an academic year.50 55

Secondary outcomes

Parenting skills will be measured using the Parenting Questionnaire (PQ), a 40-item parent-report measure of parents’ discipline strategies including their use of praise, consistency in following through on their expectations and use of corporal punishment. In prior research, CPP has led to significant improvements in parenting skills based on PQ scores.17 19

We will measure parents’ sense of belonging and connection with the school using the 5-item School Community Cohesion Survey adapted from the neighbourhood cohesion scale and shown to be related to parental monitoring of children’s behaviour.56 57 Like parent engagement, we hypothesise that CPP will lead to improvements in parents’ sense of belonging and connection with the school.

Overall K readiness will be assessed using the KRA V.2.0 total score to capture children’s readiness for learning along multiple learning domains including language/literacy, math, physical well-being/motor development and social-behavioural readiness. The KRA, a districtwide assessment, is described above.

Parent satisfaction will be measured using the CPP End of Program Satisfaction Form. This includes 16 items measuring aspects of the programme that were most and least beneficial and the extent to which the parent would recommend the programme to other parents. Each item is scored and interpreted separately.

Control variables

Demographic background variables will be collected from parents at baseline. Variables include their caregiver role in relation to the PreK child; the race, ethnicity, age and gender of the parent and PreK child; primary language spoken in the home and parents’ education, employment status, marital status and annual household income. We will also assess nine family economic hardships experienced over the past 12 months related to difficulties paying their rent, mortgage or utility bills; not having health or dental insurance to cover bills; whether they had been evicted or had their utilities turned off and food insecurity. These data will be collected at baseline and in the Fall of K and used to describe the sample, assess for balance following randomisation and control for demographic differences. Demographic background variables will also be collected from PreK teachers at baseline and K teachers in the fall of K and will include their gender, age, race, ethnicity, education and teaching experience at their current school.

To account for the effects of parents participating in school-based parent engagement activities other than CPP (eg, school committees, attending parent workshops), parents will be asked to complete a checklist of school-based activities they have participated in since the start of the school year. This checklist has been developed specifically for this study and will be completed at 4–5 months postbaseline (T2) and at the end of PreK (T3).

Implementation variables

The RE-AIM framework will be used to guide intervention implementation evaluation along five outcomes: reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance.58 The RE-AIM framework is one of the most widely used models for evaluating factors that facilitate or hinder broad dissemination of interventions and their adoption across community and clinical settings.33 Variables and measures addressing aim 4 using the RE-AIM concepts are presented in table 2 and described below.

CPPreach is defined by the characteristics of parent participation in CPP and will be measured by the per cent of eligible parents enrolled, demographic characteristics of enrolled parents and motivations for enrolling in CPP. Parents’ motivations for enrolling in CPP will be assessed at baseline using the Parent Motivation Form (PMF), a 13-item survey that asked parents to identify all of the reasons that contributed to their decision to enrol (eg, earn extra money, learn new ways to support my child’s school success, meet other parents), and then identify which reason was the most important reason.40 The survey includes one additional item that differentiates the opportunity to participate virtually (“the chance to meet other parents without having to leave my home”) or in-person (“I would enjoy the free meal while attending the parent group”) based on their assigned group. Data will be analysed as frequencies of endorsed responses, providing information on why parents choose to enrol in CPP and whether those responses differ by CPP format.

CPPeffectiveness will be assessed using quantitative and qualitative data obtained from multiple stakeholders. Parents will complete the End of Programme Satisfaction Form at postintervention to assess their perceptions of the extent to which CPP improved their parenting skills, their children’s behaviour, their confidence in supporting their children’s school success; supported their relationships with their children’s teacher and school; created challenges for participation (including technology challenges for virtual groups and transportation challenges for in person groups) and their overall satisfaction with CPP. Each item is rated separately and scored as frequencies of responses. This measure has been used in previous studies to assess parents’ satisfaction with CPP.19 27 Perceived effectiveness will also be assessed from interviews with principals, school staff and CPP group leaders to understand their perceptions of CPP’s benefits and limitations. Interviews will be conducted annually after the CPP groups have ended and analysed using content analysis. Data will be compared by school district (rural vs urban) and CPP format (virtual vs in-person).

CPPadoption will be assessed from interviews with school staff involved in CPP implementation (ie, CPP group leaders, school leadership) to understand whether and how CPP was folded into their normal workflow; perceived benefits and challenges with offering virtual versus in-person CPP; what they learnt over the course of the 2 years of implementation; whether they would want to adopt CPP at their school and why and if CPP were to continue at their school, what they believe is needed to make CPP work well for them. These interviews will be conducted at the end of the second year of each school’s participation to capture staff perceptions based on 2 years of implementation experience. We will also collect data on group leader turnover over the 2 years and differences in implementation challenges by rural versus urban school districts and virtual versus in-person groups.

CPPimplementation will focus on the quality and consistency of CPP delivery and whether they vary by urban versus rural school district and CPP format. Parent data will include CPP dose (number of CPP sessions attended, number of weekly CPP practice assignments submitted) and parent ratings of social connectedness formed within their group as measured by the Social Connectedness in Group Environments Scale. This is a 25-item parent report survey with three subscales measuring parents’ perceptions of cohesion and sense of belonging among group members (n=8 items, α=0.87), extent to which group leaders generated a positive group environment (n=6 items, α=0.90) and negative interactions among group members (n=6 items, α=0.80).59 Items are scored on a 4-point scale of strongly agree to strongly disagree. Scores have been significantly related to group participation rates, magnitude of improvement in child’s behaviour problems and measures of social well-being.30

Quality of parents’ participation in the CPP groups will be assessed after the 11th session by group leaders using the Quality of Participation Form (QPF). The QPF is a 7-item group-leader report of the extent to which parents are actively engaged in the group sessions supportive to other members in the group, open to trying new strategies and able to correctly apply programme principles, and quality of parent participation in the CPP groups. Items are rated from 1 (not at all) to 4 (most of the time) and summed (α=0.83; inter-rater reliability=0.66). QPF scores have been associated with improvements in child behaviour.37

CPP implementation quality will also be assessed by independent raters from a random selection of three audio-recorded CPP sessions per 12-session group using the CPP fidelity checklist.60 The CPP fidelity checklist assesses group leader competence (skill) and adherence to the protocol and has been validated in previous studies demonstrating significant associations with higher CPP attendance, quality of participation and parent satisfaction.60 Weekly optional virtual CPP group leader guidance sessions will be offered to all group leaders to support implementation and address implementation concerns. Group leaders demonstrating low levels of fidelity will receive additional support to improve competence and adherence. Group leaders with persistently low levels of fidelity will be replaced.

Maintenance is defined as the likelihood of schools being able to sustain CPP. Data will include CPP implementation costs and cost-effectiveness of in-person versus virtual CPP groups (including the CCTs for participating in the CPP groups); perceived barriers and facilitators to sustaining CPP in rural and urban schools and principal and school staff perceptions of how CPP contributes to their mission and parent engagement goals.

Data collection procedures

Parents and teachers will be consented using oral consent procedures and data collection will be completed in person, virtually or on the phone depending on the respondent’s preference (sample IRB-approved oral consent scripts are included as online supplemental materials). Parents who wish to complete the surveys independently may do so with a research assistant present to answer questions and ensure there is no missing data. Baseline measures will be collected by research assistants during the first weeks of the Fall term, before CPP groups begin. Teacher surveys will be completed at least 1–2 weeks after school starts to allow time for teachers to get a sense of the child’s classroom behaviour. All data will be coded with a unique identifier and entered into Research Electronic Data Capture, a HIPAA-compliant web-based application used for collection and secure storage of research data. At the conclusion of the study, parent and teacher de-identified survey data will be available for limited data sharing. Interview and fidelity data will not be shared due to difficulties fully de-identifying the transcripts. Student administrative data will not be shared due to data sharing restrictions associated with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.

Parents in the intervention condition will receive a debit card at enrolment (one card per family) for accessing their CCTs. Parents will receive US$15 for each CPP session attended and US$5 for each skill building practice assignment submitted to the group leader. The maximum total parents can receive is US$230, although the average amount typically earned is about US$120.40 Intervention group participants will also receive US$30 for completing surveys at T2, T3 and T4. To control for the benefit that may accrue to intervention parents and children from receiving more financial support, usual practice group participants will receive US$60 for completing each of the T1 and T2 surveys, and US$30 for completing each of the T3 and T4 surveys. All participants will also receive a children’s book at baseline (worth approximately US$5/book). Holiday cards and multiple text reminders will be used to promote retention.

Qualitative data evaluating school-based staff members’ perceptions of CPP effectiveness, successful integration into the school, implementation experiences and likelihood of continuing CPP after the study ends will be obtained from interviews with principals, teachers and CPP group leaders in each of the intervention schools (estimated four staff members per school). Interviews will be conducted by the study team individually or in small groups at the end of each intervention year. K readiness, school attendance and grade retention data will be obtained from the respective districts at the end of the K year and linked via students’ school ID numbers.

Data analytic plan

This study will use an intent-to-treat analysis. Data will be audited for quality and completeness. Data distributions will be evaluated to detect outliers and ensure they meet the assumptions of the planned analyses. T-tests and χ2 analyses will be used to evaluate whether randomisation achieved balance between conditions at baseline. Variables for which the two groups differ will be considered for inclusion as covariates in the analyses. Multiple imputation will be used to handle missing data in the main analyses. Sensitivity analyses will be used to assess any bias introduced through the use of imputation.

Analyses are powered for aims 1, 2 and 3. Based on prior research, we anticipate effect sizes ranging from 0.24 to 0.45 and an intraclass correlation at 0.02. We also anticipate retaining 97% of participants from baseline to end of PreK and 90% of participants from baseline to K. With a sample size of 840 (n=420/condition), 30 schools, small-to-medium effect sizes of 0.24–0.45, two-tailed alphas set at 0.05 and allowing for up to 10% attrition (n=756), we will be able to detect significant differences between groups with a power of 0.698 for effect size d’=0.20, and power of 0.872, 0.960, 0.991 and 0.999 for d’=0.25, d’=0.30, d’=0.35 and d’=0.40, respectively. For analyses stratified by format (virtual vs in-person CPP), we will be able to detect effect sizes of 0.31 or greater with a power of 0.80 and alpha of 0.05. However, the study is not powered to test differences by school district or by parent race/ethnicity. We will conduct stratified analyses and compare effect sizes between these groups to explore whether CPP efficacy varies by rural vs urban setting or parent race/ethnicity.

To test aim 1 hypotheses, we will use mixed effects regression to account for the nested structure of the data (time within child/parent and child/parent within school). All outcomes for aim 1 will be measured at T1, T2, T3 and T4. Regression models will include time, group (CPP vs usual practice) and time by group interaction as predictors of the outcome with robust SEs to account for the clustered nature of the data. Significant group by time interactions will be graphed and interpreted. Separate analyses will be conducted for each outcome. To test the aim 2 hypotheses, mixed effects regression will be used with child/parent nested within school. The outcomes for aim 2 will be measured in K and the model will include group as the main predictor with robust SEs.

To examine aim 3 and the mechanisms by which CPP improves school outcomes, multiple mediation tests will be conducted. First, parent engagement measured at T3 will be the mediator of the group (CPP vs usual practice) on chronic absence. Second, child SEB competence at T3 will be examined as a mediator of the relationship between CPP participation and (a) K readiness and (b) being retained in grade in K. For both mediators, two mediation tests will be performed: one using parent reports of parent engagement and child’s SEB competence and one using teacher reports of parent engagement and child’s SEB competence. For all analyses, we will use the product coefficient method with bootstrapping to estimate the indirect mediation effect.61 Bootstrapping will be used because the distribution of this product usually does not follow a normal distribution and bias-corrected bootstrap methods yield accurate CIs for testing the indirect effect.62 Analyses will be conducted separately for parent and teacher reports to understand how each stakeholder’s perspective may link to K outcomes.

Cost data will include the costs for group leaders, CPP training, administrative coordination, technology and the CCTs. These data will be collected annually from administrative records and expressed in constant-year dollars and appropriately discounted using a 3% discount rate. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios will be calculated using the standard form: , where the numerator is the expectation of the difference in costs between group X (CPP) and group Y (usual practice), and where the denominator is the expectation of difference in effectiveness outcome (OUTC) between CPP and no CPP. The KRA social-behavioural domain score, expressed as a standard z-score, is the principal effectiveness outcome.

Interview data to address aim 4 will be audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim and analysed using content analysis. Transcripts will first be reviewed to develop a broad understanding of how principals, teachers and group leaders perceive the programme in their respective schools and across schools within districts. Text will be coded along emergent themes specific to each of the RE-AIM components by two study team members to assess inter-rater agreement. Disagreements will be resolved with discussion and consensus and by refining coding schema and definitions. Qualitative data from the first implementation year will be compared with that obtained in the second implementation year to gain an understanding of how time and experience may influence perceptions. Themes will also be compared across school districts to gain an understanding of stakeholders’ perspectives by district (rural vs urban), CPP format and schools with different student racial and ethnic compositions.

Quantitative data to assess the RE-AIM components will be summarised descriptively at an item or mean level. For example, participants’ demographic characteristics will be summarised at the item level and compared with the overall characteristics of the PreK students enrolled in the school. Parent motivations for participating in CPP (using the PMF) and parent satisfaction with CPP (using the End of Programme Satisfaction Form) will also be analysed at the item level and compared by CPP format and location in an urban or rural school district. Parents’ perceptions of the social connections formed within their CPP group (using the Social Connectedness in Group Environments Scale) will be summarised as means and compared by CPP format and location in an urban or rural school district. The relationship between CPP dose and school outcomes will be examined using mixed effects regressions.

Qualitative and quantitative data will be integrated to obtain a holistic perspective on CPP’s reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance in urban and rural title 1 schools. Joint displays highlighting themes of convergence and divergence between quantitative and qualitative findings by RE-AIM component will be created. Results will be summarised and shared with parents, teachers, school principals and district leaders for their perspectives on the outcomes. Final reports will be published in scientific journals and presented at professional meetings.

Patient and public involvement statement

Key components of this study were designed with significant public involvement. The study intervention, the CPP, was developed over an 8-month period with an advisory board of parents from underserved communities to ensure the programme would be accessible, relevant and useful for parents with low incomes.16 In addition, the parent-report measure of parent engagement used in this study, the PEECE Survey, was previously designed by members of this team in collaboration with an advisory panel of parents, teachers and school principals from Baltimore City Public Schools. It was designed to address the limitations of existing parent-report engagement measures in schools serving students from low-income families.50

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was granted by Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (protocol number 00428221) and the Baltimore City Public Schools (protocol number 2024013). The Cecil County Public Schools Division of Education Services also reviewed and approved participation in the research.

At the conclusion of the study, results will be summarised and shared with parents, teachers, school principals and district leaders for their perspectives on the outcomes. Final reports will be published in scientific journals and presented at professional meetings. Authorship will be determined in accordance with the guidelines established by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.63

Discussion

School closures during the COVID-19 pandemic have had lingering adverse effects on young children’s SEB competence and K readiness, particularly among children from low-income and under-resourced communities.63 To date, school-based interventions to improve young children’s SEB skills and learning have primarily targeted students and teachers.64 65 Yet parents are the central figures in young children’s lives. This study seeks to improve SEB competence and K outcomes among young children from low-income families by strengthening parenting skills and promoting parent engagement in their children’s education using CPP, a 12-session group-based parenting skills programme.

This hybrid type 2 effectiveness-implementation study employs a cluster-randomised design with multiple informants and methods to rigorously examine the cost-effectiveness of CPP for strengthening parenting skills and parent engagement in their children’s education and improving three costly K outcomes affecting long-term academic success—readiness to learn, chronic absenteeism and grade retention. We will also assess CPP impacts by geography (urban vs rural school districts) and CPP delivery format (in-person vs virtual group formats). Results will have implications for CPP cost, uptake and sustainability in schools located in under-resourced communities.

Project status

The study design required that schools be enrolled and randomised by mid-summer before each academic year. This would enable (a) schools to identify and train those staff who would lead CPP groups in their school, (b) research staff time to recruit and enrol new PreK parents early in the Fall term when schools tend to offer multiple school-based parent events and (c) CPP groups to commence by October to have the greatest impact during the PreK year. However, study funding arrived later than expected. This created challenges for re-establishing agreements with the school districts (one district dropped out and had to be replaced) and recruiting schools according to design. As a result, the timeline was revised to use the first study year for planning and engaging schools, which enabled the team to recruit a new rural school district, and successfully enrol and randomise 16 schools. In April 2024, all 11 eligible schools in the rural Cecil County school district agreed to participate in the study and were randomised to intervention (n=5) or usual practice (n=6) conditions. In May 2024, five eligible Baltimore City public schools volunteered to participate and were randomised to intervention (n=3) or usual practice (n=2). Parent and teacher enrolment began in September 2024.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Jennifer Bennett, Michelle Kessler, Sequoia Jackson, Lily Stavisky, Grace McIlmoyle, Tiana Morel, Nicole Fortune Hernandez and Kainat Khan for assistance with start-up and data collection; Kwane Wyatt, Erin Cunningham and the Fund for Educational Excellence for their support with CPP coordination in Baltimore City Public Schools; Getachew Kassa for assistance with editing the manuscript; Eric Slade for his contributions to drafting portions of the study proposal and the parents, principals, staff and district leadership in the Cecil County Public Schools and Baltimore City Public Schools for their partnership in implementing and participating in this study.

Footnotes

Funding: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, #R01 HD108160

Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2025-099204).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the 'Methods' section for further details.

References

- 1.Halfon N, Houtrow A, Larson K, et al. The changing landscape of disability in childhood. Future Child. 2012;22:13–42. doi: 10.1353/foc.2012.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson LR, Holbrook JR, Bitsko RH, et al. Differences in Health Care, Family, and Community Factors Associated with Mental, Behavioral, and Developmental Disorders Among Children Aged 2–8 Years in Rural and Urban Areas — United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66:1–11. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6608a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davoudzadeh P, McTernan ML, Grimm KJ. Early school readiness predictors of grade retention from kindergarten through eighth grade: A multilevel discrete-time survival analysis approach. Early Child Res Q. 2015;32:183–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darney D, Reinke WM, Herman KC, et al. Children with co-occurring academic and behavior problems in first grade: distal outcomes in twelfth grade. J Sch Psychol. 2013;51:117–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehrlich SB, Gwynne JA, Allensworth EM. Pre-kindergarten attendance matters: Early chronic absence patterns and relationships to learning outcomes. Early Child Res Q. 2018;44:136–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster EM, Jones DE. The high costs of aggression: public expenditures resulting from conduct disorder. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1767–72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.061424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaminski JW, Barrueco S, Kelleher KJ, et al. Vital Signs for Pediatric Health: School Readiness. NAM Perspect. 2023;2023:10. doi: 10.31478/202306b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson SB, Edwards A, Cheng T, et al. Vital Signs for Pediatric Health: Chronic Absenteeism. NAM Perspect. 2023;2023:10. doi: 10.31478/202306c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathis ETB, Bierman KL. Dimensions of Parenting Associated with Child Prekindergarten Emotion Regulation and Attention Control in Low-income Families. Soc Dev. 2015;24:601–20. doi: 10.1111/sode.12112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Parenting matters: supporting parents of children ages 0-8. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blewitt C, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Nolan A, et al. Social and Emotional Learning Associated With Universal Curriculum-Based Interventions in Early Childhood Education and Care Centers: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:e185727. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones SM, Doolittle EJ. Social and Emotional Learning: Introducing the Issue. Future Child. 2017;27:3–11. doi: 10.1353/foc.2017.0000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanders MR, Turner KMT. In: Handbook of parenting and child development across the lifespan. Sanders MR, Morawska A, editors. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. The importance of parenting in influencing the lives of children; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perera RM, Hashim AK, Weddle HR. Family engagement is critical for schools COVID-19 recovery efforts. Brookings Institution; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breitenstein S, Gross D, Bettencourt AF. In: Effective approaches to reducing physical punishment and teaching discipline. Gershoff E, Lee S, editors. American Psychological Association; 2019. The chicago parent program; pp. 109–19. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gross D, Garvey C, Julion WA, et al. In: Handbook of parent training: helping parents prevent and solve problem behaviors. 3rd. Briesmeister J, Schaefer C, editors. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2007. Preventive parent training with low-income, ethnic minority families of preschoolers; pp. 5–24. edn. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breitenstein SM, Gross D, Fogg L, et al. The Chicago Parent Program: comparing 1-year outcomes for African American and Latino parents of young children. Res Nurs Health. 2012;35:475–89. doi: 10.1002/nur.21489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gross D, Belcher HME, Budhathoki C, et al. Reducing Preschool Behavior Problems in an Urban Mental Health Clinic: A Pragmatic, Non-Inferiority Trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58:572–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross D, Garvey C, Julion W, et al. Efficacy of the Chicago parent program with low-income African American and Latino parents of young children. Prev Sci. 2009;10:54–65. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0116-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY, US: W H Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co; 1997. p. 604. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biglan A. The nurture effect: how the science of human behavior can improve our lives and our world. Oakland, CA, US: New Harbinger Publications; 2015. p. 253. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gross D, Garvey D, Julion W, et al. In: Handbook of parent training: helping parents prevent and solve problem behaviors. Briesmeister JM, Schaefer CE, editors. John Wiley & Sons; 2007. Preventive parent training with low-income ethnic minority parents of preschoolers; pp. 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bettencourt AF, Gross D, Schock N, et al. Embedding a Parenting Skills Program in Public PreK: Outcomes of a Quasi-experimental Mixed Methods Study. Early Educ Dev. 2024;35:1614–37. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2023.2247954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gross D, Bettencourt AF, Taylor K, et al. What is Parent Engagement in Early Learning? Depends Who You Ask. J Child Fam Stud. 2020;29:747–60. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01680-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christenson SL, Sheridan SM. Schools and families: creating essential connections for learning. New York: Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheridan SM, Witte AL, Holmes SR, et al. A randomized trial examining the effects of Conjoint Behavioral Consultation in rural schools: Student outcomes and the mediating role of the teacher–parent relationship. J Sch Psychol. 2017;61:33–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bettencourt AF, Gross D, Breitenstein S. Evaluating Implementation Fidelity of a School-Based Parenting Program for Low-Income Families. J Sch Nurs. 2019;35:325–36. doi: 10.1177/1059840518786995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bierman K, Morris PA, Abenavoli RM. Parent engagement practices improve outcomes for preschool children. University Park, PA: Edna Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center, Pennsylvania State University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson CD, Lee MG, Dearing E, et al. Reducing Student Absenteeism in the Early Grades by Targeting Parental Beliefs. Am Educ Res J. 2018;55:1163–92. doi: 10.3102/0002831218772274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plesko CM, Yu Z, Tobin K, et al. A mixed-methods study of parents’ social connectedness in a group-based parenting program in low-income communities. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2024;94:1–14. doi: 10.1037/ort0000695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Camero E. ChangeLab Solutions; 2023. Broadband connection in rural communities. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glasgow RE, Estabrooks PE. Pragmatic Applications of RE-AIM for Health Care Initiatives in Community and Clinical Settings. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E02. doi: 10.5888/pcd15.170271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lareau A, Horvat EM. Moments of Social Inclusion and Exclusion Race, Class, and Cultural Capital in Family-School Relationships. Sociol Educ. 1999;72:37. doi: 10.2307/2673185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor ZE, Conger RD. Promoting Strengths and Resilience in Single-Mother Families. Child Dev. 2017;88:350–8. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baker CN, Arnold DH, Meagher S. Enrollment and attendance in a parent training prevention program for conduct problems. Prev Sci. 2011;12:126–38. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garvey C, Julion W, Fogg L, et al. Measuring participation in a prevention trial with parents of young children. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29:212–22. doi: 10.1002/nur.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gross D, Johnson T, Ridge A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of childcare discounts on parent participation in preventive parent training in low-income communities. J Prim Prev. 2011;32:283–98. doi: 10.1007/s10935-011-0255-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernald LCH, Kagawa RMC, Knauer HA, et al. Promoting child development through group-based parent support within a cash transfer program: Experimental effects on children’s outcomes. Dev Psychol. 2017;53:222–36. doi: 10.1037/dev0000185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gross D, Bettencourt AF. Financial Incentives for Promoting Participation in a School-Based Parenting Program in Low-Income Communities. Prev Sci. 2019;20:585–97. doi: 10.1007/s11121-019-0977-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gershoff ET, Aber JL, Raver CC, et al. Income is not enough: incorporating material hardship into models of income associations with parenting and child development. Child Dev. 2007;78:70–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00986.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raver CC, Gershoff ET, Aber JL. Testing equivalence of mediating models of income, parenting, and school readiness for white, black, and Hispanic children in a national sample. Child Dev. 2007;78:96–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00987.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sommer TE, Sabol TJ, Chase-Lansdale PL, et al. Promoting Parents’ Social Capital to Increase Children’s Attendance in Head Start: Evidence From an Experimental Intervention. J Res Educ Eff. 2017;10:732–66. doi: 10.1080/19345747.2016.1258099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Landes SJ, McBain SA, Curran GM. An introduction to effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs. Psychiatry Res. 2019;280:112513. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.CDC Social vulnerability index - place and health - geospatial research, analysis, and services program (GRASP) 2024

- 46.Jeon L, Buettner CK, Grant AA, et al. Early childhood teachers’ stress and children’s social, emotional, and behavioral functioning. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2019;61:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2018.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kotler JC, McMahon RJ. Differentiating anxious, aggressive, and socially competent preschool children: validation of the Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation-30 (parent version) Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:947–59. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.LaFreniere PJ, Dumas JE. Social competence and behavior evaluation in children ages 3 to 6 years: The short form (SCBE-30) Psychol Assess. 1996;8:369–77. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.8.4.369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eyberg S, Pincus D. Eyberg child behavior inventory: professional manual: psychological assessment resources. 1991

- 50.Gross D, Bettencourt AF, Holmes Finch W, et al. Developing an equitable measure of parent engagement in early childhood education for urban schools. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2022;141:106613. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kohl GO, Lengua LJ, McMahon RJ, et al. Parent Involvement in School Conceptualizing Multiple Dimensions and Their Relations with Family and Demographic Risk Factors. J Sch Psychol. 2000;38:501–23. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(00)00050-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Loughlin-Presnal J, Bierman KL. How do parent expectations promote child academic achievement in early elementary school? A test of three mediators. Dev Psychol. 2017;53:1694–708. doi: 10.1037/dev0000369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.WestEd Ready for kindergarten: kindergarten readiness assessment technical report: fall 2014. 2014

- 54.Maryland State Department of Education . Maryland State Department of Education; 2019. 2018 kindergarten readiness assessment results. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jeon L, Dewey N, Zhao X, et al. Kindergarten success fact book 2022. Baltimore city kindergarten classes of 2016-17 and 2021-22. Baltimore MD: Baltimore Education Research Consortium; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim ES, Kawachi I. Perceived Neighborhood Social Cohesion and Preventive Healthcare Use. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53:e35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–24. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, et al. RE-AIM Planning and Evaluation Framework: Adapting to New Science and Practice With a 20-Year Review. Front Public Health. 2019;7:64. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilson PA, Hansen NB, Tarakeshwar N, et al. Scale development of a measure to assess community-based and clinical intervention group environments. J Community Psychol. 2008;36:271–88. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Breitenstein SM, Fogg L, Garvey C, et al. Measuring implementation fidelity in a community-based parenting intervention. Nurs Res. 2010;59:158–65. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181dbb2e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium. Commun Monogr. 2009;76:408–20. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mackinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence Limits for the Indirect Effect: Distribution of the Product and Resampling Methods. Multivariate Behav Res. 2004;39:99. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.ICMJE International committee of medical journal editors: defining the role of authors and contributors. 2025

- 64.Hammerstein S, König C, Dreisörner T, et al. Effects of COVID-19-Related School Closures on Student Achievement-A Systematic Review. Front Psychol. 2021;12:746289. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.746289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pas ET, Ryoo JH, Musci RJ, et al. A state-wide quasi-experimental effectiveness study of the scale-up of school-wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. J Sch Psychol. 2019;73:41–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]