Abstract

Introduction:

Simultaneous interoceptive, emotional, and social cognition deficits are observed across neurodegenerative diseases. Indirect evidence suggests shared neurobiological bases underlying these impairments, termed the allostatic-interoceptive network (AIN). However, no study has yet explored the convergence of these deficits in neurodegenerative diseases or examined how structural and functional changes contribute to cross-domain impairments.

Methods:

A PRISMA Activated Likelihood Estimate (ALE) metanalyses encompassed studies meeting inclusion criteria: interoception, emotion, or social cognition tasks; neurodegenerative diseases (behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), primary progressive aphasias (PPAs) Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s Disease (PD), multiple sclerosis (MS)); and neuroimaging (structural: MRI voxel-based morphometry; functional: fMRI and FDG-PET).

Results:

From 20,593 studies, 170 met inclusion criteria (58 interoception, 65 emotion, and 47 social cognition) involving 7032 participants (4963 patients and 2069 healthy controls). In all participants combined, conjunction analyses revealed AIN involvement of the insula, amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate, striatum, thalamus, and hippocampus across domains. In bvFTD this conjunction was replicated across domains, with further involvement of the temporal pole, temporal fusiform cortex, and angular gyrus. A convergence of interoception and emotion in the striatum, thalamus, and hippocampus in PD and the posterior insula in PPAs was also observed. In AD and MS, disruptions in the AIN were observed during interoception, but no convergence with emotion was identified.

Interpretation:

Neurodegeneration induces dysfunctional AIN across atrophy, connectivity, and metabolism, more accentuated in bvFTD. Findings bolster the predictive coding theories of large-scale AIN, calling for more synergistic approaches to understanding interoception, emotion, and social cognition impairments in neurodegeneration.

Keywords: Interoception, allostasis, emotion, social cognition, metanalysis, neuroimaging

INTRODUCTION

Interoception involves the brain sensing, modeling, and anticipating signals from the body(1–4). This process supports allostasis, the brain’s ongoing processing of bodily resources in response to environmental demands(2, 5, 6). Interoception is increasingly recognized as being involved in emotional and social cognitive processes(3, 5, 7–10) but often from separate lines of evidence(11, 12). Neuroimaging evidence suggests that these domains overlap(7), and form the large-scale Allostatic-Interoceptive Network (AIN)(2, 5, 13). The AIN includes cortical (i.e., prefrontal, orbitofrontal, insular, cingulate, somatosensory cortices, angular gyrus, and precuneus) and subcortical regions (i.e., amygdala, hippocampus, thalamus, striatum, hypothalamus, cerebellum, and brainstem)(2, 5, 13, 14). The convergence of interoception, emotion, and social cognition is not only relevant to brain health(5, 7), but to neurodegenerative diseases. Indeed, recent evidence suggests that impairments across each domain occur in neurodegenerative diseases(15–17), however, no research investigating the convergence of these impairments within the brain exists. Here, we applied a meta-analytic approach to investigate the consistency across studies regarding the effects of neurodegeneration on the structure and function of the AIN across domains.

Impaired interoception, emotion, social cognition, and AIN dysfunctions occur across neurodegenerative diseases to varying degrees(15, 18–20). In behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), atrophy overlaps with AIN regions, including the insula, anterior cingulate cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, hypothalamus, striatum, and cerebellum(13, 14, 21–24). Separate lines of evidence also suggest that interoception, emotion, and social cognition is impaired in bvFTD(16, 18, 25–28), with emerging evidence of convergence between interoception and emotion(15, 17). In other neurodegenerative diseases, the AIN is partially involved, such as in Alzheimer’s disease (AD)(29, 30), primary progressive aphasias (PPAs)(31), Parkinson’s disease (PD)(32, 33) and multiple sclerosis (MS)(34, 35). In these syndromes, interoception, emotion, and social cognition impairments have also been reported(17, 26, 35–42), albeit less consistently than in bvFTD. Importantly, MS has been recently compared with different neurodegenerative diseases(43–45). The inclusion of diverse neurodegenerative diseases with different pathophysiological pathways allows for common and divergent disease patterns to be systematically studied(46, 47). Indeed, a transdiagnostic lesion model approach can uncover how interoception, emotion, and social cognition blend in brain health and disease, and supports dimensional approaches to psychiatry and neurology(12, 46, 48, 49). In tandem, understanding disease-specific profiles may identify earlier diagnostic markers and inform future behavioral interventions.

Despite the emerging evidence, several gaps exist. Most of the evidence is correlational or in healthy populations(5, 7). Within neurodegeneration, convergence has only been inferred from separate domains(16, 25, 26, 28), with few multi-domain assessments(15, 17, 36). A meta-analytic approach enables the synthesis across studies in each domain and provides a higher level of evidence. To date, no current metanalyses within separate neurodegenerative diseases exist, with no transdiagnostic evidence of the combined effects across these domains. Further, no study has investigated how these domains may be influenced by core aspects related to neurodegeneration, including brain volume, connectivity, and metabolism. Finally, how these domains are impacted in neurodegenerative diseases with varied AIN involvement is completely unknown.

To address these gaps, we conducted coordinate-based metanalyses using the anatomical/activation likelihood estimation (ALE) method(50, 51). We performed an extensive literature search via PubMed and PsycINFO databases. From 20,593 studies, we identified 169 reports, including 6985 participants (4937 patients and 2048 healthy controls) that investigated interoception, emotion, or social cognition and their neural bases (i.e., structural and/or functional correlates). Our first aim was to identify common brain regions involved in across domains in a diverse range of neurodegenerative diseases. We predicted that all domains would converge in AIN regions, including the insula, anterior cingulate cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, thalamus, and cerebellum as evidence of shared neurobiological mechanisms across neurodegenerative diseases(2, 5). Our second aim was to identify disease-specific profiles. We hypothesized that convergence across domains would be specifically relevant in bvFTD(13, 15, 16, 26), compared to other neurodegenerative diseases, due to more circumscribed AIN involvement. To achieve these aims, domain-specific, disease-specific, and conjunction analyses were performed.

METHODS

Systematic literature search

A systematic literature review of all neuroimaging studies of interoception, emotion, or social cognition in neurodegenerative diseases was conducted up until 30th August 2023 (Supplementary Figure 1 for methodological workflow, Table 1 for search terms). Search terms resulted in 20,593 publications using PubMed and PsycInfo via Ovid databases. Neuroimaging metanalysis recommendations were followed(52). Following PRISMA reporting guidelines, all publications underwent screening and eligibility checks and met inclusion criteria (Supplementary Figure 2). Reference lists of eligible articles were screened. Corresponding authors were contacted for further information/data if required. All studies were double-blind reviewed by J.L.H and F.C using Rayyan.ai (https://www.rayyan.ai/)(53). Discrepancies were discussed until agreement was met, with a third reviewer (A.I) available.

Table 1.

Search terms used in the current study.

| Concepts | Terms used |

|---|---|

| Neurodegenerative diseases | “Dementia*” OR “Neurodegenerat*” OR “Alzheimer*” OR “behavioural-variant*” OR “Frontotemporal*” OR “Primary Progressive Aphasia*” OR “Progressive non-fluent aphasia” OR “logopen*” OR “Semantic dementia” OR “right-temporal variant*” OR “Amytrophic Lateral Sclerosis” OR “Motor Neuron Disease” OR “Huntington*” OR “Multiple Sclerosis” OR “Multiple System Atrophy” OR “Progressive Supranuclear Palsy” OR “Corticobasal Syndrome” OR “Corticobasal*” OR “Frontotemporal Lobar*” OR “Parkinson*” OR “Pure Autonomic Failure” |

| Neuroimaging | “Neuroimaging*” OR “Functional Neuroimaging*” OR “fMRI*” OR “functional MRI*” OR “PET*” OR “Positron emission tomography*” OR “MRI*” OR “Neural correlate*” OR “Neural bas*” OR “structural neuroimaging*” |

| + Interoception (only) | “intero*” OR “interoception” OR “cardiac interoception” OR “visceral perception” OR “visceral*” OR “body*” OR “bodily*” OR “heartbeat” OR “heartbeat detection” OR “autonomic*” OR “fatigue*” OR “pain*” OR “thermoregulation*” OR “temperature*” OR “touch*” OR “respirat*” OR “breath*” OR “gastric*” OR “stomach*” OR “eating*” OR “psychophysio*” OR “skin conductance*” OR “skin*” OR “pupil*” |

| + Emotion (only) | “emotion*” OR “emotion recognition*” OR “emotion perception*” OR “affective*” OR “affect*” |

| + Social Cognition (only) | “social cognition*” OR “theory of mind*” OR “mentalizing*” OR “mentali*” OR “empathy*” OR “empath*” |

Inclusion criteria included studies with:

English, Spanish, or Portuguese language (only English studies were identified).

Interoception, emotion, or social cognition assessments in neurodegeneration (e.g., behavioural tasks or questionnaire data).

Coordinate-based structural (i.e., voxel-based morphometry, VBM or surface-based morphometry, SBM) or functional (i.e., fMRI, FDG-PET) outcomes.

Coordinates reported in standard brain spaces (Montreal Neurological Institute, MNI or Talairach & Tournoux, TAL).

Contrasts that compared: neurodegeneration to healthy controls; control/baseline to an experimental task in patients; brain structure/function to symptoms in patients.

Statistical analysis

Anatomical/Activation Likelihood Estimate (ALE)

Multiple ALE metanalyses were conducted (version 3.0.2, http://brainmap.org)(50, 51, 54). Neuroimaging results included studies reporting: 1) deactivations or decreases only (structural or functional); 2) activations only (increases in functional activity1) in patients relative to controls during behavioral tasks of interoception, emotion, or social cognition, or at rest. For functional imaging, task-based and resting-state connectivity metrics were considered together due to evidence of shared neural correlates between task and resting-state networks(55–58). This strategy has been employed in neurodegenerative diseases previously to maximize power in areas where limited research is currently available(14, 22). Cluster coordinates (X,Y,Z), statistical thresholds, and effect sizes where possible were extracted from each study. All TAL-based coordinates were converted to MNI-based coordinates in GingerALE(50). MNI coordinates, sample size, and contrasts were entered into GingerALE. The GingerALE algorithm estimates the likelihood (but not effect size) that a peak change will occur in any given voxel across the brain. This algorithm models the probability distribution of each foci estimating both within- and between-study variability and calculates the above-chance clustering between experiments (i.e., random-effect analysis) rather than between foci (i.e., fixed-effects analysis)(50, 51). Reported foci are treated as spatial probability distributions (Gaussian probabilities) centered at the foci and studies are weighted by sample size (tighter Gaussian functions) to account for spatial uncertainty(50, 51). Cluster analyses were performed to identify significant domain-specific clusters. Conjunction analyses identified overlapping brain regions associated with each domain using Ginger-ALE (i.e., two-way conjunctions) and FSL suite (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk., three-way conjunctions)(see eMethods).

Statistical significance for the domain-specific metanalyses were reported at both i) cluster-level inference family-wise error (FWE) p<.05 with 5000 permutations, with a cluster-forming threshold at p<.001, and ii) whole-brain voxel-wise uncorrected, p<.001, cluster extent 200mm3. Domain-convergent metanalyses were reported at FWE p<.05, 5000 permutations.

Disease-specific profiles

Disease-specific profiles were investigated in domains where n>5 studies were available (domain-specific and domain-convergent) following procedures outlined above. PPA subtypes (i.e., progressive non-fluent aphasia, left- and right-lateralized semantic dementia) were combined due to limited data available. Interoception and emotion metanalyses were conducted in AD, PD, and PPAs, and in interoception only in MS due to insufficient data. In bvFTD, AD, and PPAs, results reported focused on deactivations/reduced integrity only, due to insufficient or non-existent activation data.

Publication bias and heterogeneity

We repeated our main domain-specific metanalyses to analyze publication bias and heterogeneity using Seed-based d mapping (SDM; 59). This technique accounts for sample sizes, brain coordinates, and effect sizes. Heterogeneity was assessed via I2(60) and publication bias was assessed via Egger’s tests and visualized by funnel plots(59–61).

RESULTS

Systematic search

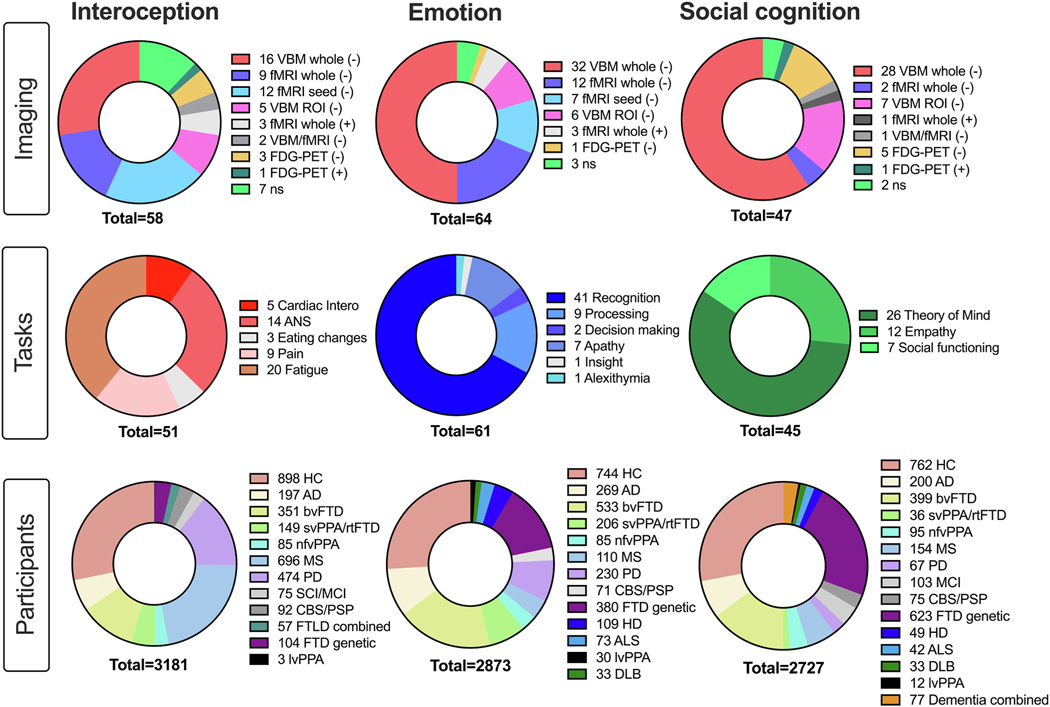

One hundred and seventy publications were included across domains, including 7032 participants (4963 patients and 2069 healthy controls; Figure 1, Supplementary Tables 1-8 for study information). Most studies reported deactivations/reduced structural integrity (94.7%) and used structural imaging (57.6%).

Figure 1:

Studies included in the metanalysis across domains detailing imaging techniques, tasks used, and number of participants per domain. Note total N across domains > total N reported in text due to 15 studies contributing to more than 1 domain. Abbreviations: Imaging: ns = non-significant; Tasks: ANS = Autonomic nervous system; Intero = Interoception; Participants (in order): HC = Healthy control; AD = Alzheimer’s disease; bvFTD =behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia; svPPA = semantic-variant primary progressive aphasia; rtvFTD = right temporal variant frontotemporal dementia; nfv-PPA = non-fluent variant primary progressive aphasia; MS = Multiple sclerosis; PD = Parkinson’s Disease; CBS/PSP = Corticobasal syndrome, progressive supranuclear palsy; SCI/MCI = Subjective cognitive impairment/Mild cognitive impairment; FTLD combined = frontotemporal lobar degeneration; FTD genetic = presymptomatic MAPT, GRN, C972orf mutation carriers; HD = Huntington’s Disease; ALS = Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis; lvPPA = logopenic-variant primary progressive aphasia; Dementia combined = AD, FTD sample.

All neurodegenerative diseases

Interoception

Deactivations/reduced structural integrity in interoception involved the anterior cingulate cortex, anterior and posterior insula, striatum, precentral gyrus, thalamus bilaterally, and the left orbitofrontal cortex and right hippocampus (Figure 3A, Supplementary Table 9, 776 foci). Activations in interoception involved the posterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex, precentral gyrus, angular gyrus, and cerebellum bilaterally, and the left post-central gyrus and left precuneus (Figure 4A, Supplementary Table 9, 203 foci).

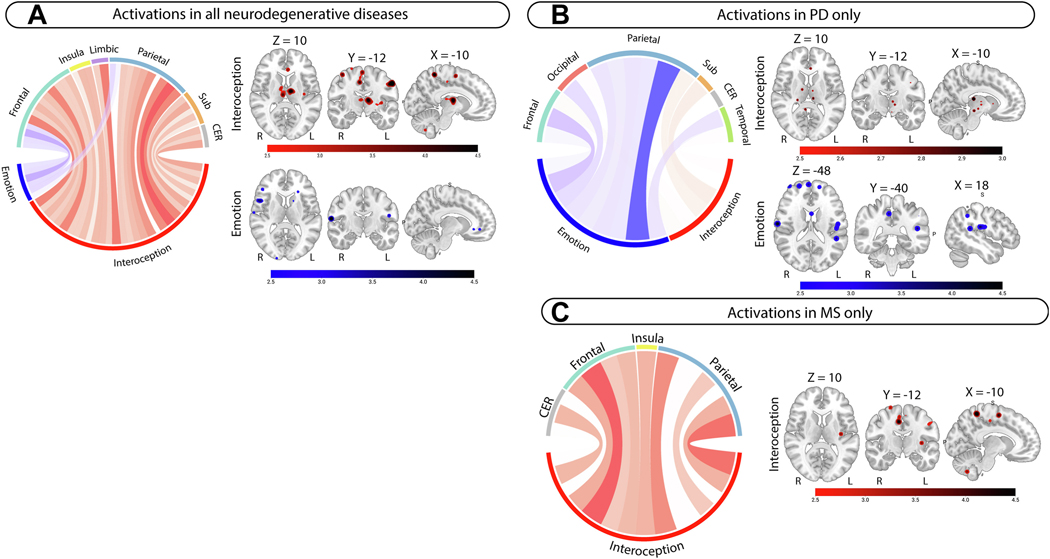

Figure 3.

Metanalyses results for activation contrasts in all neuroimaging modalities and in PD and MS. Left-sided panel shows metanalyses results in all neurodegenerative diseases for A) individual metanalyses; conjunction analyses were not significant. Right-sided panel shows metanalyses results for individual domains specific to B) PD and C) MS. All circular plot display z-scores for brain regions in interoception (red), emotion (blue) in individual metanalyses. Larger z-scores are shown in darker colors for each metanalysis. Clusters are reported at p <.001 uncorrected. All brain slices are displayed in radiological orientation (Right = Left). MNI coordinates are displayed above the first image for each panel unless different coordinates are used (e.g., 5B). Brainstem included in Sub cluster in PD. Abbreviations: CER = Cerebellum; Sub = Subcortical grey matter.

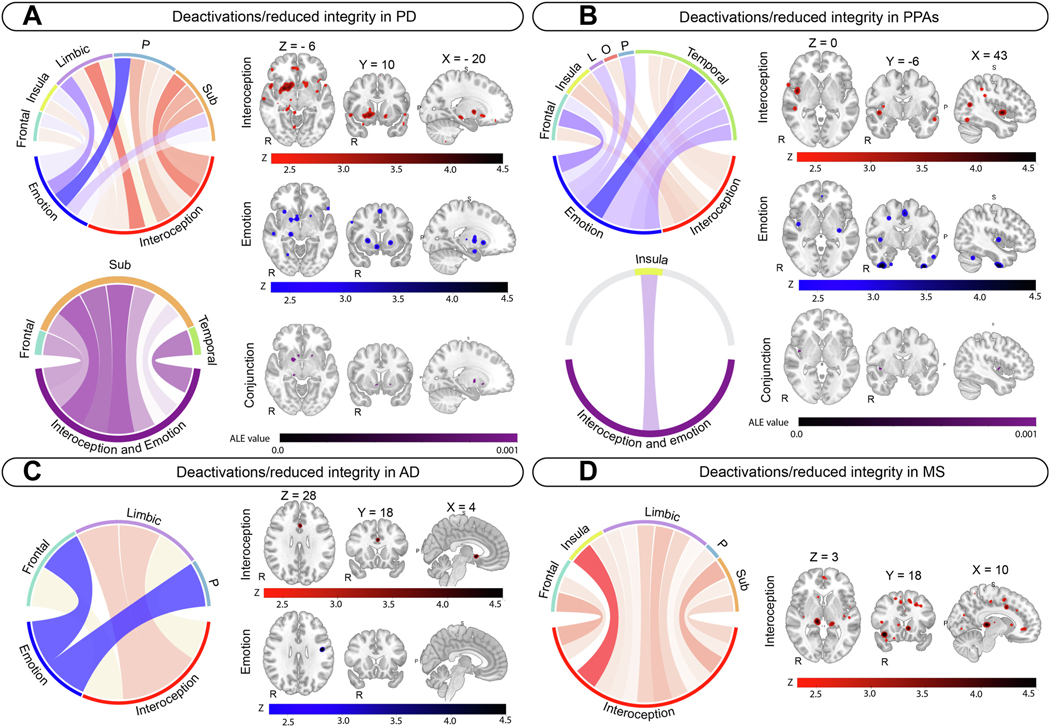

Figure 4.

Disease specific metanalysis results for deactivations/reduced structural integrity for interoception (red) and emotion (blue), and conjunction analyses (purple). A) Parkinson’s disease. B) Primary progressive aphasia. C) Alzheimer’s disease. D) Multiple Sclerosis. A and B show individual metanalysis results and conjunction metanalyses results. C and D show individual metanalysis results only. All individual metanalyses results are reported at p <.001, uncorrected. Circular plots and neuroimaging panels display z-scores for each individual metanalysis, with darker colors representing larger z-scores. Conjunction metanalysis results are reported at p <.05 FWE, with 5000 permutations. Circular plots and neuroimaging panels for conjunction analyses display ALE scores, with darker colors representing larger values. MNI coordinates are displayed above the first neuroimage image for each panel. Neuroimages are displayed in radiological presentation (right = left). Brainstem included in Sub cluster in PD. Abbreviations: L = Limbic, O = Occipital, P = Parietal, Sub = Subcortical grey matter.

Emotion

Deactivations/reduced structural integrity in emotion were observed bilaterally in the temporal pole, anterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex striatum, amygdala, hippocampus, thalamus, and temporal fusiform gyrus, together with the left posterior insula, left middle temporal gyrus, left middle frontal gyrus, right orbitofrontal cortex, and right frontal pole (Figure 3A, Supplementary Table 10, 707 foci). Activations in emotion included the bilateral central opercular cortex, right frontal pole, right inferior frontal gyrus, left postcentral gyrus, and right supramarginal gyrus (Figure 4A, Supplementary Table 10, 66 foci).

Social cognition

Deactivations/reduced structural integrity in social cognition involved the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior insula and paracingulate gyrus bilaterally, and the left posterior insula, right amygdala, left anterior cingulate cortex, left thalamus, right temporal pole (Figure 3A, Supplementary Table 11, 658 foci). Insufficient data was available reporting activations in social cognition (n<5 studies) and therefore not included in further analyses.

Domains by imaging modality and whole-brain analyses only

Separate analyses based on whole-brain coordinates only (excluding ROI studies) and on different imaging modalities (e.g., structural vs. functional) were conducted (Supplementary Table 21-28). In brief, significant clusters identified in whole-brain analyses were largely consistent with those including ROIs. Further, similar brain regions were observed across functional and structural modalities. Notable differences from the main analyses included no significant clusters observed for functional imaging in social cognition.

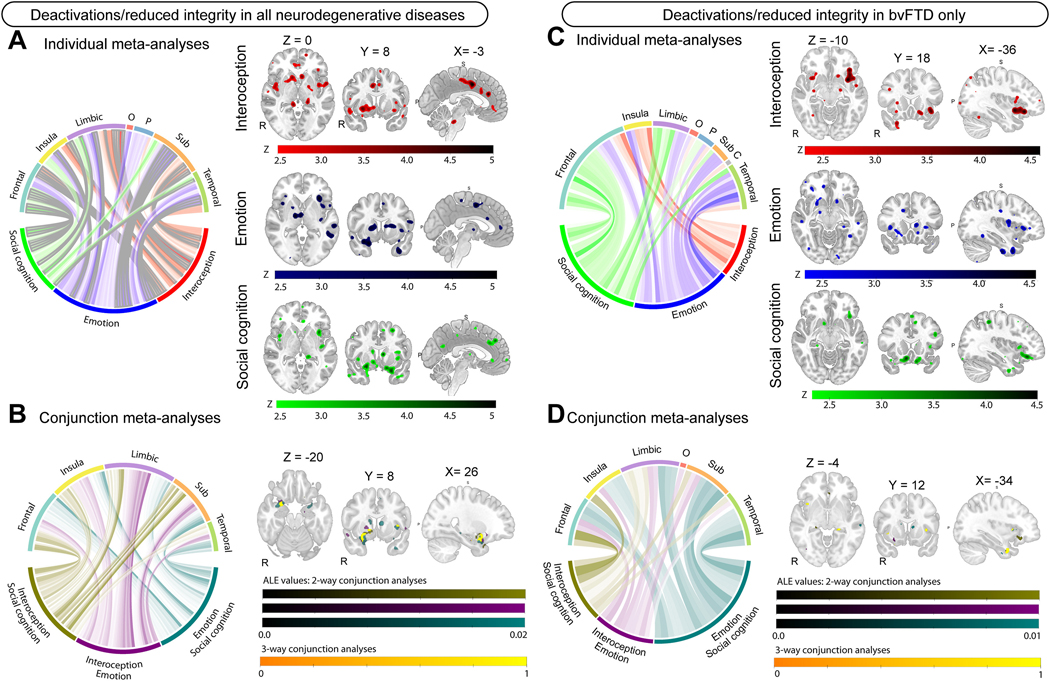

Convergence of domains

Deactivation/reduced structural integrity in interoception and emotion involved the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior and posterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex, striatum, amygdala, hippocampus, and thalamus bilaterally, and the right temporal pole, right temporal fusiform cortex, right medial prefrontal cortex, and left supplementary motor cortex (Figure 2B, Supplementary Table 12). No convergence for activations was observed.

Figure 2.

Metanalyses results for deactivations/reduced structural integrity contrasts in all neuroimaging modalities and in bvFTD. Left-sided panel shows metanalyses results in all neurodegenerative diseases for A) individual metanalyses; and B) conjunction metanalyses. Right-sided panel shows metanalyses results specific to bvFTD for C) individual metanalyses; and D) conjunction metanalyses. For A and C: Circular plot displaying z-scores for brain regions in interoception (red), emotion (blue), and social cognition (green) in individual metanalyses. Larger z-scores are shown in darker colors for each metanalysis. Clusters significant at p <.05 FWE corrected are outlined in grey, with p <.001 uncorrected showing no outline. For B and D: Circular plot display ALE-scores for two-way conjunction analyses, with larger ALE-scores shown in darker colors. Interoception-social cognition (olive; color bar 1); Interoception-Emotion (purple, color bar 2); Emotion-social cognition (teal, color bar 3), Interoception-Emotion-Social cognition (yellow, color bar 4). Color bars represent ALE scores for significant clusters (color bars 1–3) and a binary outcome of the three way-analysis (color bar 4). All regions are displayed at p <.001, uncorrected. All brain slices are displayed in radiological orientation (Right = Left). MNI coordinates are displayed above brain slices. Abbreviations: C = Cerebellum; O = Occipital; P = Parietal; Sub = Subcortical grey matter.

Deactivation/reduced structural integrity in interoception and social cognition involved the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior and posterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex, middle temporal gyrus, striatum, hippocampus and thalamus bilaterally, and the right amygdala, and left supplementary motor cortex (Figure 2B, Supplementary Table 12).

Deactivation/reduced structural integrity in emotion and social cognition involved the temporal pole, amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, anterior and posterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex, thalamus, and hippocampus bilaterally, and the right subcallosal cortex, right frontal pole, right medial prefrontal cortex, left temporal fusiform cortex, and left supplementary motor cortex (Figure 2B, Supplementary Table 12).

Deactivation/reduced structural integrity in all three domains involved the anterior and posterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, hippocampus, parahippocampus, and thalamus bilaterally, and the right temporal pole, right amygdala, and right striatum (Figure 2B, Table 2).

Table 2.

Convergent brain regions involved in interoception, emotion, and social cognition across neuroimaging modalities in all neurodegenerative diseases.

| Area | Side | Cluster | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Deactivations/reduced integrity | |||||

| Temporal pole, orbitofrontal cortex, parahippocampal gyrus, anterior insula, putamen, amygdala | R | 1 | 26 | 8 | -24 |

| Accumbens, pallidum, putamen and caudate | R | 2 | 12 | 8 | -10 |

| Anterior insula | L | 3 | -38 | 4 | 0 |

| Anterior cingulate cortex | L | 4 | -6 | -6 | 44 |

| Hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, thalamus | L | 5 | -18 | -36 | -6 |

| Anterior insula | L | 6 | -38 | -4 | -12 |

| Posterior insula | R | 7 | 44 | -4 | 0 |

| Amygdala, hippocampus | R | 8 | 22 | -8 | -16 |

| Orbitofrontal cortex, insula | R | 9 | 30 | 18 | -14 |

| Hippocampus, thalamus | R | 10 | 24 | -34 | -8 |

| Orbitofrontal cortex, anterior insula | L | 11 | -36 | 26 | -8 |

| Hippocampus | R | 12 | 28 | -8 | -24 |

| Hippocampus | R | 13 | 32 | -14 | -14 |

| Temporal pole | R | 14 | 32 | 16 | -26 |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | R | 15 | 28 | -12 | -30 |

| Orbitofrontal cortex | L | 16 | -16 | 14 | -14 |

Note. Results include all imaging modalities, and whole-brain and ROI-based approaches. Conjunction analyses were only possible in studies reporting deactivations/decreased integrity due to insufficient data in social cognition reporting activations.

Diagnosis-specific metanalyses

bvFTD

Interoception, emotion, and social cognition

Interoception in bvFTD involved the anterior insula and orbitofrontal cortex bilaterally, and the right temporal pole, posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, and cerebellum (Figure 3C, Supplementary Table 13, 110 foci). Emotion in bvFTD involved the anterior insula, orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, thalamus, middle and superior temporal gyri bilaterally, and the left temporal pole and left temporal fusiform cortex (Figure 3C, Supplementary Table 14, 259 foci). Social cognition in bvFTD involved the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, frontal pole, middle frontal gyrus, paracingulate gyrus bilaterally, and the right temporal pole and caudate (Figure 3C, Supplementary Table 15, 300 foci).

Convergence of domains

Interoception and emotion in bvFTD involved the anterior insula, temporal fusiform cortex, and hippocampus bilaterally, and the right orbitofrontal cortex, and left amygdala and thalamus (Figure 3C, Supplementary Table 16). Interoception and social cognition in bvFTD involved the bilateral anterior cingulate cortex, left orbitofrontal cortex, left anterior insula, left temporal pole and temporal fusiform cortex, and right thalamus and hippocampus (Figure 3C, Supplementary Table 16). Emotion and social cognition in bvFTD involved the caudate, temporal pole, and temporal fusiform cortex bilaterally, and the left anterior insula, left hippocampus, left anterior cingulate cortex, left superior temporal gyrus and middle temporal gyrus, and the right amygdala, right putamen, and right orbitofrontal cortex (Figure 3C, Supplementary Table 16). Convergence in all domains in bvFTD involved the anterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex, temporal pole, frontal pole bilaterally, and the left temporal fusiform cortex, left parahippocampal gyrus, left hippocampus, left thalamus and left angular gyrus (Figure 3D, Table 3)

Table 3.

Convergent brain regions involved in interoception, emotion, and social cognition across neuroimaging modalities in bvFTD.

| Area | Side | Cluster | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Deactivations/reduced structural integrity | |||||

| Temporal fusiform cortex, temporal pole | L | 1 | -34 | 0 | -40 |

| Temporal fusiform cortex, parahippocampal gyrus | L | 2 | -26 | -12 | -42 |

| Temporal pole, orbitofrontal cortex, anterior insula | R | 3 | 28 | 8 | -24 |

| Superior frontal gyrus | R | 4 | 18 | 30 | 54 |

| Hippocampus, thalamus | L | 5 | -20 | -32 | -8 |

| Anterior insula | L | 6 | -36 | 12 | 0 |

| Anterior insula | R | 7 | 40 | 12 | -4 |

| Frontal pole, inferior frontal gyrus | L | 8 | -46 | 40 | 0 |

| Posterior cingulate cortex | R | 9 | 12 | -22 | 38 |

| Anterior cingulate cortex | L | 10 | -6 | 44 | 4 |

| Supramarginal gyrus, angular gyrus | L | 11 | -44 | -48 | 14 |

| Middle frontal gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus | R | 12 | 44 | 14 | 30 |

| Anterior Insula | L | 13 | -36 | 22 | -2 |

| Putamen | L | 14 | -28 | 8 | 8 |

| Frontal pole | R | 15 | 36 | 46 | 20 |

| Anterior insula | L | 16 | -32 | 8 | 8 |

| Paracingulate gyrus | L | 17 | -6 | 52 | 8 |

Note. Results include all imaging modalities, and whole-brain and ROI-based approaches. Conjunction analyses were only possible in studies reporting deactivations/decreased integrity due to insufficient data in social cognition reporting activations.

PD

Interoception and emotion

Deactivations (functional only2) in interoception in PD involved the bilateral anterior cingulate cortex, and the right posterior insula, amygdala, striatum, and parietal opercular cortex (Figure 4A, Supplementary Table 17, 367 foci). Deactivations/reduced structural integrity in emotion in PD involved the right anterior insula, amygdala, and orbitofrontal cortex, and the left postcentral gyrus, putamen, and brainstem (Figure 4A, Supplementary Table 18, 43 foci). Activations in interoception in PD involved the right frontal pole, middle frontal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, and brainstem, and the left post central gyrus, and cerebellum (Figure 3B, Supplementary Table 17, 86 foci). Activations in emotion in PD involved the frontal poles and central opercular cortices bilaterally, and the left planum temporale and post central gyrus (Figure 3B, Supplementary Table 18, 22 foci). Convergence for deactivations/reduced structural integrity involved the bilateral putamen and pallidum, right accumbens, thalamus, hippocampus, planum temporale, and central opercular cortex in PD (Figure 4A, Supplementary Table 19). No convergence in activations was observed in PD.

PPAs

Interoception and emotion

Interoception in PPAs involved the bilateral posterior insula and the right planum temporale and central opercular cortex, lingual gyrus, temporo-occipital fusiform cortex, and left inferior and middle temporal gyri (Figure 4B, Supplementary Table 17, 49 foci). Emotion in PPAs involved the temporal fusiform cortex and anterior cingulate cortex bilaterally, and the right frontal pole and left temporal pole, superior temporal gyrus and left inferior frontal gyrus (Figure 4B, Supplementary Table 18, 50 foci). Interoception and emotion in PPAs involved the right posterior insula (Figure 4B, Supplementary Table 19).

AD

Interoception and emotion

Interoception in AD involved the right subcallosal cortex and accumbens, and the left anterior cingulate cortex and superior frontal gyrus (Figure 4C, Supplementary Table 17, 71 foci), whereas emotion involved the right precentral and post central gyrus (Figure 4C, Supplementary Table 18, 43 foci). No convergence was observed.

MS

Interoception

Deactivations/reduced structural integrity in interoception studies in MS involved the anterior cingulate cortex, thalamus, posterior cingulate cortex, and supplementary motor cortex bilaterally, and the right anterior insula and inferior frontal gyrus and left posterior insula, frontal pole, and striatum (Figure 4D, Supplementary Table 17, 201 foci). Activations in interoception in MS involved the postcentral gyrus, supplementary motor cortex, and cerebellum bilaterally, and the left posterior insula and precuneus (Figure 3C, Supplementary Table 17, 53 foci).

Publication bias and heterogeneity

Our main metanalyses were replicated in interoception, emotion, and social cognition separately using SDM (Supplementary Tables 29-33). Majority of clusters showed low-to-moderate between-study heterogeneity (I2=0.03–41.51%). Considerable between-study heterogeneity was observed in one cluster in interoception (I2 = 60.10%), 4 clusters in emotion (I2=51.93–67.49%) and with substantial heterogeneity observed in 1 cluster in social cognition (I2 = 78.95%). Funnel plots were symmetric and potential publication bias tests were not statistically significant (all p’s>0.05; Supplementary Tables 34-38, Supplementary Figures 3-6).

DISCUSSION

Our metanalyses reveals multidomain dysfunctional allostatic-interoception in neurodegeneration. This finding supports recent predictive coding theories of allostatic-interoceptive processing(5, 13, 19) and complements previous brain health metanalyses(7, 62). Regarding our first aim, we observed consistent dysfunction of the AIN contributing to interoceptive, emotional, and social cognition impairment in cortical, “predictive” regions, such as the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex, and amygdala(5, 13) and subcortical or “relay” regions, such as the posterior insula, striatum, hippocampus, and thalamus in neurodegeneration(5, 13). Addressing our second aim, we replicated these findings in bvFTD across domains, supporting previous hypotheses(16, 63, 64). We consider how these findings inform our theoretical and clinical understanding of allostatic-interoception in neurodegeneration.

Our novel findings indicate that the AIN plays a crucial role in allostatic-interoceptive processing and socio-emotional functioning in neurodegeneration. This evidence supports recent theoretical models of predictive coding in neurodegeneration(13, 19, 65), complimenting previous evidence from computational models, non-human primate studies, and healthy populations studies of the AIN(5, 7, 62, 66) and can refine our understanding of the social brain(10, 67). In the predictive allostatic-interoceptive coding framework, interoceptive and allostatic processes are intertwined. These processes anticipate and respond to environmental demands and perform internal regulatory functions throughout the lifespan, supported by the AIN(19). In neurodegeneration, whole-body manifestations of dysfunctional allostatic-interoception may occur across multiple pathways (e.g., neural, inflammation, microbiome, cardiometabolic, and immune pathways) during the disease course resulting in maladaptive responses to the environment(1, 13, 49, 68, 69). The predictive coding framework of allostatic-interoception offers a synergetic perspective(12) to consider brain-body communication across dimensions and timescales in the continuum of brain health and disease across the lifespan(19) and departs from traditional, compartmentalized theories of brain function(11). This framework represents a substantial advance in our understanding of brain function and supports dimensional approaches across psychiatric and neurological populations(19, 48).

Within our study, we also observed increased functional connectivity within some AIN regions in interoception, such as the posterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex, angular gyrus, precuneus, postcentral gyrus, and cerebellum. The presence of both activations and deactivations/atrophy within the AIN could reflect compensatory neural mechanisms and highlights the need to consider the non-linear and dynamic process of neurodegeneration(19, 66, 70). The non-linear cumulative burden of responding to environmental stressors together with biological predispositions can lead to allostatic overload(6, 13). Systematic investigation of allostatic overload markers together with network dynamics and disease profiles is needed to understand this relationship. Our study provides evidence that widespread AIN dysfunction contributes to both impaired higher-order socio-emotional processes and atypical allostatic-interoception in neurodegeneration simultaneously.

Our findings support the allostatic-interoceptive dysfunction as a core feature of bvFTD(13, 19). Multi-modal allostatic-interoceptive deficits in bvFTD span electrophysiological, peripheral, neuroanatomical, and behavioral levels(13, 15, 17, 18), together with evidence of allostatic overload(18) and maladaptive social behavior(71). In bvFTD, degeneration of AIN regions is observed across pathological causes(72) and in early disease stages(24). The allostatic-interoceptive coding framework proposes that maladaptive/dysregulated behaviors in bvFTD are likely due to abnormal predictive coding at multiple brain levels(5, 13, 19). Supporting this framework, we observed reduced functional and/or structural integrity of higher order “predictive” brain regions such as the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior insula, amygdala, and anterior cingulate cortex, as well as with lower-level relay regions, including the posterior insula, striatum, thalamus, and hippocampus in bvFTD(5, 13). Of clinical relevance, allostatic-interoceptive abnormalities can occur approximately 10–15 years before bvFTD diagnosis(73), whereas social cognitive impairments can occur approximately 5 years before bvFTD diagnosis(74). This evidence indicates that allostatic-interoceptive measures could function as very early biomarkers of neurodegenerative processes. These biomarkers could support precision medicine approaches to early therapeutic interventions and address modifiable risk factors in neurodegeneration. Further, bvFTD often presents with multiple psychiatric manifestations, with ~50% of cases receiving a prior psychiatric diagnosis(75), with overlapping AIN alterations in gray matter observed in both bvFTD and primary psychiatric disorders(76). Therefore, altered allostatic-interoceptive processing may represent a transdiagnostic feature across psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases(19, 48) supporting dimensional approaches in psychiatry and neurology. These proposals remains an open question for future longitudinal research to investigate.

In other neurodegenerative diseases, partial convergence of interoception and emotion was observed within some AIN regions. This finding aligns with the more circumscribed AIN atrophy in other dementia syndromes compared to bvFTD, where earlier and widespread AIN damage is observed(13, 23, 24). In PPAs, reduced connectivity/integrity of the posterior insula and anterior temporal lobes were observed in interoception, and convergence with emotion observed in the posterior insula. These findings emphasize the non-language features in PPAs(37, 41, 42, 77) and call for more interoception research in PPA subtypes. In PD, decreased functional activity was observed in AIN regions including the posterior insula, striatum, anterior cingulate cortex, and amygdala, and convergence with emotion observed in subcortical structures including the striatum, thalamus, and hippocampus. This finding supports the AIN in the pathophysiology of dysautonomia in PD beyond the peripheral nervous system and provides a potential mechanism linking autonomic dysfunction and emotional disturbances observed in PD(15, 17, 78). Interestingly, in PD and MS, both increases/decreases were observed in parts of the AIN, further highlighting the dynamic processes involved in neurodegeneration and compensatory processes that may occur in the disease course(19, 70). Further, in PD, this finding could reflect dynamic shifts in heart-brain coupling reflecting shifts in dopaminergic tone(79), however this remains speculative and requires future research. In AD, reduced involvement of the anterior cingulate cortex and striatum was observed during interoception, with no convergence with emotion. As the AIN is a large-scale domain-general network(5), it is also possible that AIN dysfunctions may lead to interoceptive predictive coding errors underlying other symptoms such as memory, language, motor control impairment and reward-oriented behaviours in neurodegeneration(13, 48, 65, 68, 80), however this remains speculative and an open avenue for future research.

Several limitations should be noted. First, neuroimaging techniques that do not provide coordinate-based outcomes were not eligible for inclusion, including white matter tractography, electroencephalography, and magnetoencephalography, which may contribute towards our understanding of interoception, emotion, and social cognition. Second, in the ALE analysis, activations/anatomical peaks are weighted only by each study’s sample size, which can vary in neurodegenerative diseases. GingerALE overcomes this limitation by treating each foci as the center of the probability distribution and accounting for both between-subject and between-experiment variability(50). This approach balances potential type I and type II errors(81). Other measurements, such as cluster sizes and variable statistical thresholds applied for group-level comparisons, may influence the results. To address this issue, we replicated our metanalyses using SDM and obtained similar results when considering effect sizes associated with each study, highlighting the robustness of our meta-analytic findings Further, although our overall results were well-powered, with many foci and participants considered, the lack of research currently available in some neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., subtypes of PPAs) likely influenced our power to detect effects in these subgroups. Indeed, the limited research within PPA subtypes impeded our ability to conduct separate metanalyses, however, as more studies emerge this will be important for our understanding of nonlanguage symptoms observed in PPAs(31, 41, 42). In addition, although publication bias was minimal within each respective metanalysis, the majority of studies reported deactivations only. Further, imaging studies included in the current study were cross-sectional, limiting our ability to comment on causal relationships. Taken together, the lack of longitudinal research and research investigating both activations and deactivations in specific neurodegenerative diseases currently available limits our understanding of the dynamic and non-linear processes likely occurring during neurodegeneration(19). Additionally, interoception, emotion, and social cognition have not been routinely investigated within the same paradigm. Future research harnessing advanced connectivity methods, such as spatiotemporal brain dynamics and spectral dynamic causal modelling, in tailored paradigms to investigate interoception, emotion, and social cognition is needed to directly assess predictive coding frameworks of allostatic-interoception. Additionally, we combined task-based and resting-state connectivity studies due to evidence of substantial network overlap(55–58, 67) and to maximize power(14, 22), however, future research should incorporate modality-specific analyses as more studies become available. Finally, commenting on specific neurodegenerative processes contributing to allostatic-interoception, emotion, and social cognition deficits is beyond the scope of this study. Future research using well-characterized neurodegenerative diseases and fine-grained analysis techniques is needed to uncover this relationship.

Our findings provide the most comprehensive metanalysis of neuroimaging data, covering interoception, emotion, and social cognition in a large transdiagnostic neurodegenerative cohort. We identified key structures within the AIN that are simultaneously involved in altered interoception, emotion and social cognition, with particular relevance for bvFTD. This study presents the first lesion-based metanalysis of the AIN in neurodegeneration, providing critical evidence that supports synergetic predictive coding frameworks in health and disease. Our findings suggest that AIN dysfunction could represent an early indicator of neurodegeneration, particularly in bvFTD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement statement

We would like to thank the authors of studies included in this metanalysis for their kind assistance in providing information when required. We would also like to thank all the participants and their families for participating in the studies included in this metanalysis.

Funding sources

JLH is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship granted by the multi-partner consortium to expand dementia research in Latin America (ReDLat). FC is supported by a PhD grant funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology with reference 2023.00362.BD. AI is supported by grants from CONICET; ANID/FONDECYT Regular (1210195 and 1210176 and 1220995); ANID/FONDAP/15150012; ANID/PIA/ANILLOS ACT210096; FONDEF ID20I10152, ID22I10029; ANID/FONDAP 15150012; Takeda CW2680521 and the MULTI-PARTNER CONSORTIUM TO EXPAND DEMENTIA RESEARCH IN LATIN AMERICA [ReDLat, supported by Fogarty International Center (FIC), National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Aging (R01 AG057234, R01 AG075775, R01 AG=21051, R01 AG083799, CARDS-NIH), Alzheimer’s Association (SG-20–725707), Rainwater Charitable Foundation – The Bluefield project to cure FTD, and Global Brain Health Institute)].

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author contributions (CRediT statement).

JLH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – Original draft, Visualization; FC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing; MM: Software, Formal analysis, Data Curation; FR: Methodology, Software, Writing – Review & Editing; AL: Visualization, Writing – Review & Editing; FA: Visualization, Writing – Review & Editing; YC: Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing; CPD: Writing – Review & Editing; SB: Writing – Review & Editing; AI: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – Review & Editing. All authors contributed to reviewing/editing and final approval of the manuscript.

Note, no studies reported increased grey matter intensity in patients vs. controls

No studies reported reduced structural integrity associated with interoception in PD.

References

- 1.Berntson GG, Khalsa SS (2021): Neural circuits of interoception. Trends in neurosciences. 44:17–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen WG, Schloesser D, Arensdorf AM, Simmons JM, Cui C, Valentino R, et al. (2021): The emerging science of interoception: sensing, integrating, interpreting, and regulating signals within the self. Trends in neurosciences. 44:3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman M, Bliss-Moreau E, Lindquist K (2024): The neurobiology of interoception and affect. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quigley KS, Kanoski S, Grill WM, Barrett LF, Tsakiris M (2021): Functions of interoception: From energy regulation to experience of the self. Trends in neurosciences. 44:29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleckner IR, Zhang J, Touroutoglou A, Chanes L, Xia C, Simmons WK, et al. (2017): Evidence for a large-scale brain system supporting allostasis and interoception in humans. Nature human behaviour. 1:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sterling P (2012): Allostasis: a model of predictive regulation. Physiology & behavior. 106:5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adolfi F, Couto B, Richter F, Decety J, Lopez J, Sigman M, et al. (2017): Convergence of interoception, emotion, and social cognition: a twofold fMRI meta-analysis and lesion approach. Cortex. 88:124–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nord CL, Garfinkel SN (2022): Interoceptive pathways to understand and treat mental health conditions. Trends in cognitive sciences. 26:499–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quadt L, Critchley HD, Garfinkel SN, Tsakiris M, De Preester H (2018): Interoception and emotion: Shared mechanisms and clinical implications. The interoceptive mind: From homeostasis to awareness. 123. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiller D, Alessandra N, Alia-Klein N, Becker S, Cromwell HC, Dolcos F, et al. (2024): The human affectome. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 158:105450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibanez A (2022): The mind’s golden cage and cognition in the wild. Trends in cognitive sciences. 26:1031–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibanez A, Kringelbach ML, Deco G (2024): A synergetic turn in cognitive neuroscience of brain diseases. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Migeot JA, Duran-Aniotz CA, Signorelli CM, Piguet O, Ibáñez A (2022): A predictive coding framework of allostatic–interoceptive overload in frontotemporal dementia. Trends in Neurosciences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, Kumfor F, Landin‐Romero R, Irish M, Hodges JR, Piguet O (2018): Cerebellar atrophy and its contribution to cognition in frontotemporal dementias. Annals of neurology. 84:98–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hazelton JL, Fittipaldi S, Fraile-Vazquez M, Sourty M, Legaz A, Hudson AL, et al. (2023): Thinking versus feeling: How interoception and cognition influence emotion recognition in behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. Cortex. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van den Stock J, Kumfor F (2017): Behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia: at the interface of interoception, emotion and social cognition. Cortex. 115:335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salamone PC, Legaz A, Sedeño L, Moguilner S, Fraile-Vazquez M, Campo CG, et al. (2021): Interoception primes emotional processing: Multimodal evidence from neurodegeneration. Journal of Neuroscience. 41:4276–4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birba A, Santamaría-García H, Prado P, Cruzat J, Ballesteros AS, Legaz A, et al. (2022): Allostatic interoceptive overload in frontotemporal dementia. Biological Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ibanez A, Northoff G (2023): Intrinsic timescales and predictive allostatic interoception in brain health and disease. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews.105510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rouse MA, Binney RJ, Patterson K, Rowe JB, Lambon Ralph MA (2024): A neuroanatomical and cognitive model of impaired social behaviour in frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 147:1953–1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang M, Landin-Romero R, Matis S, Dalton MA, Piguet O (2024): Longitudinal volumetric changes in amygdala subregions in frontotemporal dementia. Journal of Neurology.1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamalian A, Khodadadifar T, Saberi A, Masoudi M, Camilleri JA, Eickhoff CR, et al. (2022): Convergent regional brain abnormalities in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: A neuroimaging meta‐analysis of 73 studies. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring. 14:e12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piguet O, Petersén Å, Yin Ka Lam B, Gabery S, Murphy K, Hodges JR, et al. (2011): Eating and hypothalamus changes in behavioral‐variant frontotemporal dementia. Annals of neurology. 69:312–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seeley WW, Crawford R, Rascovsky K, Kramer JH, Weiner M, Miller BL, et al. (2008): Frontal paralimbic network atrophy in very mild behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Archives of neurology. 65:249–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dermody N, Wong S, Ahmed R, Piguet O, Hodges JR, Irish M (2016): Uncovering the neural bases of cognitive and affective empathy deficits in Alzheimer’s disease and the behavioral-variant of frontotemporal dementia. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 53:801–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.García-Cordero I, Sedeño L, De La Fuente L, Slachevsky A, Forno G, Klein F, et al. (2016): Feeling, learning from and being aware of inner states: interoceptive dimensions in neurodegeneration and stroke. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 371:20160006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumfor F, Honan C, McDonald S, Hazelton JL, Hodges JR, Piguet O (2017): Assessing the “social brain” in dementia: applying TASIT-S. Cortex. 93:166–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumfor F, Hazelton JL, Rushby JA, Hodges JR, Piguet O (2019): Facial expressiveness and physiological arousal in frontotemporal dementia: phenotypic clinical profiles and neural correlates. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 19:197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapleau M, Aldebert J, Montembeault M, Brambati SM (2016): Atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease and semantic dementia: an ALE meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease. 54:941–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, et al. (2011): The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia. 7:263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, et al. (2011): Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 76:1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jubault T, Brambati SM, Degroot C, Kullmann B, Strafella AP, Lafontaine A-L, et al. (2009): Regional brain stem atrophy in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease detected by anatomical MRI. PloS one. 4:e8247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tremblay C, Rahayel S, Vo A, Morys F, Shafiei G, Abbasi N, et al. (2021): Brain atrophy progression in Parkinson’s disease is shaped by connectivity and local vulnerability. Brain Communications. 3:fcab269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiang FL, Wang Q, Yu FF, Romero RS, Huang SY, Fox PM, et al. (2019): Localised grey matter atrophy in multiple sclerosis is network-based: a coordinate-based meta-analysis. Clinical radiology. 74:816. e819–816. e828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonzalez Campo C, Salamone PC, Rodríguez-Arriagada N, Richter F, Herrera E, Bruno D, et al. (2020): Fatigue in multiple sclerosis is associated with multimodal interoceptive abnormalities. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 26:1845–1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hazelton JL, Devenney E, Ahmed R, Burrell J, Hwang Y, Piguet O, et al. (2023): Hemispheric contributions toward interoception and emotion recognition in left-vs right-semantic dementia. Neuropsychologia. 188:108628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hazelton JL, Irish M, Hodges JR, Piguet O, Kumfor F (2017): Cognitive and affective empathy disruption in non-fluent primary progressive aphasia syndromes. Brain Impairment. 18:117–129. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Landin-Romero R, Kumfor F, Lee AY, Leyton C, Piguet O (2024): Clinical and cortical trajectories in non-fluent primary progressive aphasia and Alzheimer’s disease: A role for emotion processing. Brain Research.148777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Radlak B, Cooper C, Summers F, Phillips LH (2021): Multiple sclerosis, emotion perception and social functioning. Journal of neuropsychology. 15:500–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salamone PC, Esteves S, Sinay VJ, García‐Cordero I, Abrevaya S, Couto B, et al. (2018): Altered neural signatures of interoception in multiple sclerosis. Human brain mapping. 39:4743–4754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hardy CJ, Taylor‐Rubin C, Taylor B, Harding E, Gonzalez AS, Jiang J, et al. (2024): Symptom‐led staging for semantic and non‐fluent/agrammatic variants of primary progressive aphasia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 20:195–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hardy CJ, Taylor‐Rubin C, Taylor B, Harding E, Gonzalez AS, Jiang J, et al. (2024): Symptom‐based staging for logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia. European Journal of Neurology. 31:e16304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abrevaya S, Fittipaldi S, García AM, Dottori M, Santamaria-Garcia H, Birba A, et al. (2020): At the heart of neurological dimensionality: Cross-nosological and multimodal cardiac interoceptive deficits. Psychosomatic medicine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Varma-Doyle AV, Lukiw WJ, Zhao Y, Lovera J, Devier D (2021): A hypothesis-generating scoping review of miRs identified in both multiple sclerosis and dementia, their protein targets, and miR signaling pathways. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 420:117202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giovannoni G (2017): Should we rebrand multiple sclerosis a dementia? Multiple sclerosis and related disorders. 12:79–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ibanez A, Zimmer ER (2023): Time to synergize mental health with brain health. Nature Mental Health. 1:441–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prado P, Medel V, Gonzalez-Gomez R, Sainz-Ballesteros A, Vidal V, Santamaría-García H, et al. (2023): The BrainLat project, a multimodal neuroimaging dataset of neurodegeneration from underrepresented backgrounds. Scientific Data. 10:889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santamaría-García H, Migeot J, Medel V, Hazelton JL, Teckentrup V, Romero-Ortuno R, et al. (2024): Allostatic interoceptive overload across psychiatric and neurological conditions. Biological Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quadt L, Critchley HD, Garfinkel SN (2018): The neurobiology of interoception in health and disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1428:112–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eickhoff SB, Laird AR, Grefkes C, Wang LE, Zilles K, Fox PT (2009): Coordinate-based activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of neuroimaging data: A random-effects approach based on empirical estimates of spatial uncertainty. Human Brain Mapping. 30:2907–2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eickhoff SB, Bzdok D, Laird AR, Kurth F, Fox PT (2012): Activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis revisited. NeuroImage. 59:2349–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muller VI, Cieslik EC, Laird AR, Fox PT, Radua J, Mataix-Cols D, et al. (2018): Ten simple rules for neuroimaging meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 84:151–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A (2016): Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic reviews. 5:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Turkeltaub PE, Eickhoff SB, Laird AR, Fox M, Wiener M, Fox P (2012): Minimizing within-experiment and within-group effects in activation likelihood estimation meta-analyses. Human Brain Mapping. 33:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cole MW, Ito T, Bassett DS, Schultz DH (2016): Activity flow over resting-state networks shapes cognitive task activations. Nature neuroscience. 19:1718–1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith SM, Fox PT, Miller KL, Glahn DC, Fox PM, Mackay CE, et al. (2009): Correspondence of the brain’s functional architecture during activation and rest. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences. 106:13040–13045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kraus BT, Perez D, Ladwig Z, Seitzman BA, Dworetsky A, Petersen SE, et al. (2021): Network variants are similar between task and rest states. Neuroimage. 229:117743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elliott ML, Knodt AR, Cooke M, Kim MJ, Melzer TR, Keenan R, et al. (2019): General functional connectivity: Shared features of resting-state and task fMRI drive reliable and heritable individual differences in functional brain networks. NeuroImage. 189:516–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Radua J, Mataix-Cols D, Phillips ML, El-Hage W, Kronhaus DM, Cardoner N, et al. (2012): A new meta-analytic method for neuroimaging studies that combines reported peak coordinates and statistical parametric maps. Eur Psychiatry. 27:605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Albajes-Eizagirre A, Solanes A, Fullana MA, Ioannidis JP, Fusar-Poli P, Torrent C, et al. (2019): Meta-analysis of voxel-based neuroimaging studies using seed-based d mapping with permutation of subject images (SDM-PSI). JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments).e59841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ma T, Li ZY, Yu Y, Hu B, Han Y, Ni MH, et al. (2022): Gray and white matter abnormality in patients with T2DM-related cognitive dysfunction: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Diabetes. 12:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schulz SM (2016): Neural correlates of heart-focused interoception: a functional magnetic resonance imaging meta-analysis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 371:20160018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johnen A, Bertoux M (2019): Psychological and cognitive markers of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia–A clinical neuropsychologist’s view on diagnostic criteria and beyond. Frontiers in neurology. 10:433908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ibañez A, Manes F (2012): Contextual social cognition and the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 78:1354–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kocagoncu E, Klimovich-Gray A, Hughes LE, Rowe JB (2021): Evidence and implications of abnormal predictive coding in dementia. Brain. 144:3311–3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Petzschner FH, Garfinkel SN, Paulus MP, Koch C, Khalsa SS (2021): Computational models of interoception and body regulation. Trends in neurosciences. 44:63–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alcalá-López D, Smallwood J, Jefferies E, Van Overwalle F, Vogeley K, Mars RB, et al. (2018): Computing the social brain connectome across systems and states. Cerebral cortex. 28:2207–2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Franco-O’Byrne D, Santamaría-García H, Migeot J, Ibáñez A (2024): Emerging Theories of Allostatic-Interoceptive Overload in Neurodegeneration. Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Savitz J, Harrison NA (2018): Interoception and inflammation in psychiatric disorders. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging. 3:514–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Palop JJ, Chin J, Mucke L (2006): A network dysfunction perspective on neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 443:768–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Piguet O, Kumfor F, Hodges J (2017): Diagnosing, monitoring and managing behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Medical Journal of Australia. 207:303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Perry DC, Brown JA, Possin KL, Datta S, Trujillo A, Radke A, et al. (2017): Clinicopathological correlations in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 140:3329–3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ahmed RM, Ke YD, Vucic S, Ittner LM, Seeley W, Hodges JR, et al. (2018): Physiological changes in neurodegeneration—mechanistic insights and clinical utility. Nature Reviews Neurology. 14:259–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Russell LL, Greaves CV, Bocchetta M, Nicholas J, Convery RS, Moore K, et al. (2020): Social cognition impairment in genetic frontotemporal dementia within the GENFI cohort. cortex. 133:384–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ducharme S, Dols A, Laforce R, Devenney E, Kumfor F, Van Den Stock J, et al. (2020): Recommendations to distinguish behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia from psychiatric disorders. Brain. 143:1632–1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ulugut H, Trieu C, Groot C, van’t Hooft JJ, Tijms BM, Scheltens P, et al. (2023): Overlap of neuroanatomical involvement in frontotemporal dementia and primary psychiatric disorders: a Meta-analysis. Biological Psychiatry. 93:820–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fittipaldi S, Ibanez A, Baez S, Manes F, Sedeno L, García AM (2019): More than words: Social cognition across variants of primary progressive aphasia. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 100:263–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Horsager J, Borghammer P (2024): Brain-first vs. body-first Parkinson’s disease: An update on recent evidence. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders.106101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Candia-Rivera D, Chavez M, de Vico Fallani F (2024): Measures of the coupling between fluctuating brain network organization and heartbeat dynamics. Network Neuroscience.1–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chokesuwattanaskul A, Jiang H, Bond RL, Jimenez DA, Russell LL, Sivasathiaseelan H, et al. (2023): The architecture of abnormal reward behaviour in dementia: multimodal hedonic phenotypes and brain substrate. Brain Communications. 5:fcad027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bossier H, Seurinck R, Kühn S, Banaschewski T, Barker GJ, Bokde AL, et al. (2018): The influence of study-level inference models and study set size on coordinate-based fMRI meta-analyses. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 11:745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.