Summary

The ever-increasing stream of big data offers potential for deep decarbonization in the transportation sector but also presents challenges in extracting interpretable insights due to its complexity and volume. This overview discusses the application of transportation big data to help understand carbon dioxide emissions and introduces how artificial intelligence models, including machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), are used to assimilate and understand these data. We suggest using ML to interpret low-dimensional data and DL to enhance the predictability of data with spatial connections across multiple timescales. Overcoming challenges related to algorithms, data, and computation requires interdisciplinary collaboration on both technology and data.

Keywords: carbon neutrality, transportation emissions, intelligent transportation system, big data, artificial intelligence

Graphical abstract

The bigger picture

The transportation sector accounts for one-fifth of global CO2 emissions and is one of the most challenging sectors to decarbonize due to its heavy reliance on fossil fuels. As urbanization and economic development accelerate, a critical question arises: how can we effectively decarbonize transportation while sustaining economic growth? A significant barrier is the limited understanding of real-world transportation CO2 emissions, especially their dynamic and localized characteristics, which impedes the development of targeted and effective mitigation strategies. In this era of information explosion, big data and artificial intelligence (AI) hold significant potential to enhance our understanding of transportation emissions. As the global community works to meet the ambitious goals of the Paris Agreement and achieve carbon neutrality, integrating data-driven insights into policy and decision-making becomes increasingly crucial.

This perspective highlights a novel toolkit to comprehend transportation emissions through AI-powered analysis of big data, demonstrating how advanced technologies bridge the gap between scientific innovation and practical solutions. The ability to extract and apply meaningful knowledge from complex data will be indispensable for governments and industries alike, offering a valuable contribution to the global efforts toward deep transportation decarbonization. Meanwhile, such applications present significant challenges and opportunities for data and AI technologies, emphasizing the importance of cross-disciplinary collaboration to foster technological advancements and data sharing, while paving the way for smarter, more efficient pathways toward carbon neutrality.

Big data show significant potential for deep decarbonization in the transportation sector, while advances in artificial intelligence (AI) technologies help extract valuable knowledge from such data. This perspective reviews the applications of big data and AI technologies in transportation, encompassing data accumulation, pattern understanding, and the intricate nexus between transportation activities and carbon emissions, ultimately providing insights for achieving carbon neutrality.

Introduction

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reported that global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reached unprecedented levels from 2010 to 2019, underscoring the urgent need for reductions across all sectors.1 The transportation sector, including aviation, shipping, and on-road vehicles, significantly contributes to economic growth but accounts for 20% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.2 With the expansion of emerging economies, transportation emissions are outpacing most other industries and are projected to double by 2050.3 However, decarbonizing the transportation sector remains particularly challenging due to its dependence on fossil fuels, raising a critical question: does transportation hinder future CO2 emission reduction efforts?

Achieving carbon-neutral transportation necessitates a comprehensive understanding of CO2 emissions. However, the sector’s dynamic nature introduces significant spatiotemporal variability, complicating emission accounting.4 While macro-level data, such as statistical yearbooks, are commonly used for estimating transportation emissions,5,6 this method often misrepresents spatiotemporal distributions, particularly in developing nations where data may be incomplete or unreliable. Over the past decade, advances in environmental informatics have greatly improved emission analysis and applications.7 Data-driven policies play a critical role in enabling countries to meet their Paris Agreement commitments and reach peak carbon emissions. Big data refer to vast, complex, and continuously expanding datasets from diverse sources.8 In transportation, such data span various scales, including roadside sampling (on-road remote sensing), environmental monitoring at tens of meters, and satellite observations covering hundreds of kilometers. The Internet of Things (IoT) advances urban intelligent transportation systems (ITSs),9 enabling the daily transmission of vast transportation data.10 This innovation offers a significant opportunity to address policy assessment challenges and drive deep decarbonization.

The era of big data generates massive volumes of transportation data daily, with storage exceeding petabytes and transmission rates reaching hundreds of terabytes per day.11 However, data collection outpaces our ability to process and analyze it effectively. The key challenge lies in extracting valuable insights from these datasets and integrating them across disciplines (Figure 1). The emergence of novel data sources has driven advances in computing, while recent progress in artificial intelligence (AI) offers new frameworks for analyzing transportation big data.12 Machine learning (ML) efficiently processes large, high-dimensional datasets with relatively simple structures.13 By contrast, deep learning (DL)14 excels in capturing complex spatial and temporal patterns that influence system behavior.15

Figure 1.

The cascade of transportation big data, knowledge, and insight for carbon-neutral transportation

The subsequent sections examine transportation big data and their role in analyzing CO2 emissions. We explore the application of ML in processing such data and emphasize DL’s potential to address their increasing complexity. Finally, we discuss challenges and emerging opportunities at the intersection of AI and transportation research.

Transportation big data

On-board measurements

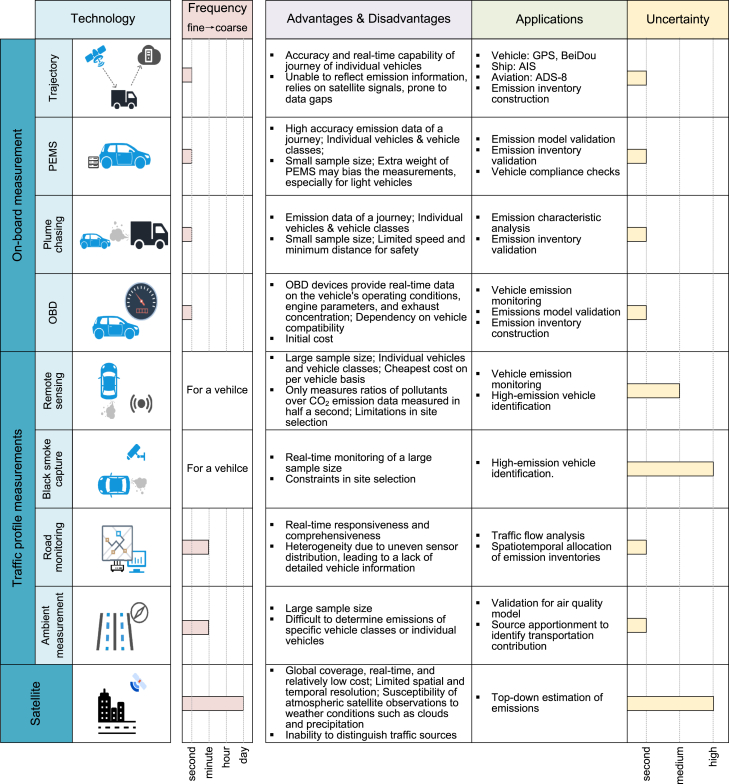

Real-time operational data from vehicles, ships, and aircraft are recorded through sensors and modules, ensuring safety, efficiency, and accuracy (Figure 2). These measurements are crucial for analyzing emission patterns, such as their spatiotemporal distribution and characteristics.

Figure 2.

Major existing transportation big data

Trajectory data, commonly gathered using the global positioning system (GPS) or similar location sensors, are widely used to track travel paths as well as operational factors, including speed and direction. GPS is frequently deployed in on-road transportation, particularly in taxis and buses, due to its low cost.16 Due to limited vehicle deployment and activity range, trajectory data are often used to allocate aggregate emissions across road networks.17,18,19 Recently, GPS data have helped assess the carbon emission benefits of electrification or fuel transition for passenger vehicles.20 The BeiDou navigation satellite system, which tracks the speed and location of heavy-duty trucks (HDTs),9 offers near-real-time, high-coverage data for billions of HDTs trajectories, surpassing the capabilities of ground-based GPS. This system enables the creation of high-resolution emission inventories for HDTs.4 In non-road sectors, including shipping, the widespread use of the automatic identification system (AIS) has shifted emission inventory calculation methods from static to dynamic, offering a more detailed spatiotemporal analysis of ship CO2 emissions, from local ports to a global scale.21,22 AIS data may occasionally experience signal loss or anomalies due to satellite disruptions, equipment maintenance, or transmission issues. In aviation, growing concern over high-altitude emissions and advances in communication, navigation, and surveillance have led to the use of automatic dependent surveillance broadcast (ADS-B). This open data source allows precise emission characterization during different flight stages using time, longitude, latitude, and altitude.23,24,25 AIS and ADS-B have higher deployment rates than vehicle position systems, with AIS being installed on nearly all types of ships. This broad coverage allows researchers to analyze global dynamics in shipping and aviation, such as assessing the spatial variation of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) impacts (Figures 3A and 3B).26,27

Figure 3.

Applications of big data for characterizing the transportation activity changes

Examples of (A) ships,27 (B) aircraft,26 and (C) vehicles under the impact of COVID-19.

(C) reprinted with permission from Lv et al.28 Copyright 2025 American Chemical Society.

There are also on-road monitoring technologies that provide both real-time pollutant concentrations and GPS data, enabling emissions to be calculated directly from recorded concentrations rather than relying on empirical models. One such system, the portable emissions measurement system (PEMS), collects pollutant concentrations through probes connected to the vehicle tailpipe, along with GPS data, and is widely used to determine operational conditions and emission levels on a second-by-second basis.29,30,31 Similarly, plume-chasing technologies measure real-time emissions by trailing a target vehicle or ship with a lab-equipped vehicle or trailer.32,33 While effective for monitoring emissions,34,35,36 their widespread application across entire fleets and the creation of comprehensive emission inventories are limited by time and cost constraints. Therefore, trajectory signals from these technologies remain underutilized. Originally intended to detect emissions exceeding standards, the on-board diagnostic (OBD) system has advanced to record operating conditions, engine parameters, and exhaust concentrations, aiding in emission inventory development.37,38,39 With the transition from Euro 6 to Euro 7 standards, on-board monitoring systems are expected to complement OBD systems, ensuring real-world emission compliance.40,41

Traffic profile measurements

Traffic flow, pollutant concentrations, and related data are commonly measured through non-on-board technologies. These methods, targeting vehicles, roads, ships, sea surfaces, aircraft, and atmospheric layers, facilitate indirect analysis of real-world emissions and their spatiotemporal distribution.

Remote sensing, developed by the University of Denver,42 is the most widely used vehicle-oriented technology, with datasets available on the Fuel Efficiency Automobile Test website (https://digitalcommons.du.edu/feat/). This roadside method measures pollutant-to-CO2 ratios in exhaust but cannot directly quantify pollutant concentrations. It is primarily employed for regulatory purposes, such as monitoring fleet emissions43,44 or identifying high-emitting vehicles.45,46 Additionally, roadside remote sensing data are utilized to develop emission factors and models,47,48 primarily for common pollutants rather than GHGs. Another method, black smoke capture technology, employs image processing to detect harmful substances in vehicle exhaust. By analyzing colors and optical features, it identifies emissions, with a focus on black smoke as a key pollution indicator. Given the uncertainties in sensors and image processing algorithms, black smoke capture technology is primarily employed to identify high-emitting vehicles.49 However, public datasets on vehicle black smoke emissions are limited due to high deployment costs. An example is the Smoke Vehicles Computer Vision Project (https://universe.roboflow.com/alpha-ai-nwrrb/smoke-vehicles/model/3?webcam=true), which offers black smoke segmentation data and online testing tools.

Road-oriented technologies, now integral to ITS, are categorized into magnetic-frequency-based methods (such as underground loop detectors), wave-frequency-based methods (such as remote traffic microwave sensors and radio-frequency identification), and video monitoring. These systems, installed on key roads, gather data on speed, traffic volume, and lane occupancy, facilitating urban-scale emission allocation, major road emission estimates,28,50 and the identification of emission hotspots.51 While ITS lacks the detailed vehicle data, such as trajectory systems, it offers the widest coverage among on-road traffic data sources, enabling analysis of activity changes in road transport (Figure 3C).28 Ambient measurements, though unable to directly quantify emissions from individual vehicles or fleets, capture road pollutant concentrations with low cost and high temporal resolution.52,53,54,55 When combined with receptor modeling, these measurements can attribute pollutant concentrations to mobile sources, supporting the estimation of their emissions.

Satellite observations

Advances in satellite technology have greatly improved global GHG monitoring and the understanding of anthropogenic CO2 emissions. Early satellites, such as AQUA and ENVISAT (both launched in 2002), pioneered atmospheric chemistry studies. Later missions, including AURA (2004), with enhanced spatial resolution, and METOP-A (2006), featuring the infrared atmospheric sounding interferometer, further advanced CO2 monitoring capabilities. Launched in 2009, GOSAT was the first hyperspectral satellite focused on atmospheric CO2 detection, providing global CO2 and CH4 data for at least 5 years. In 2018, GOSAT-2 enhanced the precision and provided more cloud-free measurements. Since 2009, the US Orbiting Carbon Observatory series (OCO-2, 2014, and OCO-3, 2019) has delivered high spatial resolution, despite longer revisit intervals. Researchers have used OCO-2 data to create multi-annual gridded CO2 datasets.56,57 In 2016, China launched TANSAT, achieving advanced levels in high-resolution atmospheric trace gas detection. Future missions, including France’s Microcarb and the France-Germany MerLin collaboration, will further enhance global GHG monitoring capabilities.

Emission detection using CO2 satellites varies by study scale. At regional or national levels, inverse models, such as variational data assimilation (4D-Var) and ensemble filtering, are typically used to optimize bottom-up emission inventories by minimizing the discrepancy between observed and modeled concentrations from chemical transport models (CTMs).58,59 These approaches often incorporate other satellite observations, such as NO2 column densities from OMI and TROPOMI with improved spatiotemporal resolution, to inverse CO2 emissions by first estimating NOx emissions and converting them into CO2 emissions using CO2 and NOx emission factors.60 This method has resulted in a CO2 emission product derived from TROPOMI NO2 observations.61 At the city scale, Lagrangian-based inversion methods are commonly employed for flux estimation,62,63 as they require fewer simulations and provide greater sensitivity to upwind sources compared with Eulerian approaches. For point sources, emissions can be directly estimated from satellite observations and wind data using methods such as Gaussian plume fitting or mass-balance approaches. These techniques, independent of CTM simulations,64,65 offer reduced computational costs and are more effective in estimating short-term carbon emission variations compared with bottom-up models that depend on annual updates.

The estimation of transportation CO2 emissions predominantly relies on 4D-Var approaches due to the insufficient temporal-spatial resolution of current CO2 satellite data, which cannot accurately detect dynamic emission plumes in complex, polluted environments, particularly over land where large power or industrial sources dominate. Consequently, bottom-up emission inventories are crucial for providing corrective prior information. In the aviation sector, emissions are relatively small, and satellite observations, primarily focused on the troposphere, struggle to capture the impact of aircraft emissions, which occur mainly in the stratosphere. By contrast, satellites are more effective for estimating shipping CO2 emissions, as vessels operate in open seas with minimal other anthropogenic sources. Examples include CTM-based global emission inventories59 and non-CTM methods for port emissions.66 To broaden satellite applications for estimating CO2 emissions across more transportation sectors, improving satellite data quality, especially temporal-spatial resolution, is crucial.

AI

AI is a field focused on enabling computers to perform tasks that require human intelligence. A subset of AI, ML enhances computer systems by learning patterns from data, while DL, a specialized form of ML, uses deep neural networks to represent complex data patterns. These methods have become powerful tools for data mining. Advances in detection and characterization technologies have significantly expanded transportation data volume, driving the adoption of AI. Common ML models are now widely supported by libraries in Python, R, and MATLAB, with PyTorch and TensorFlow being the most popular DL frameworks.

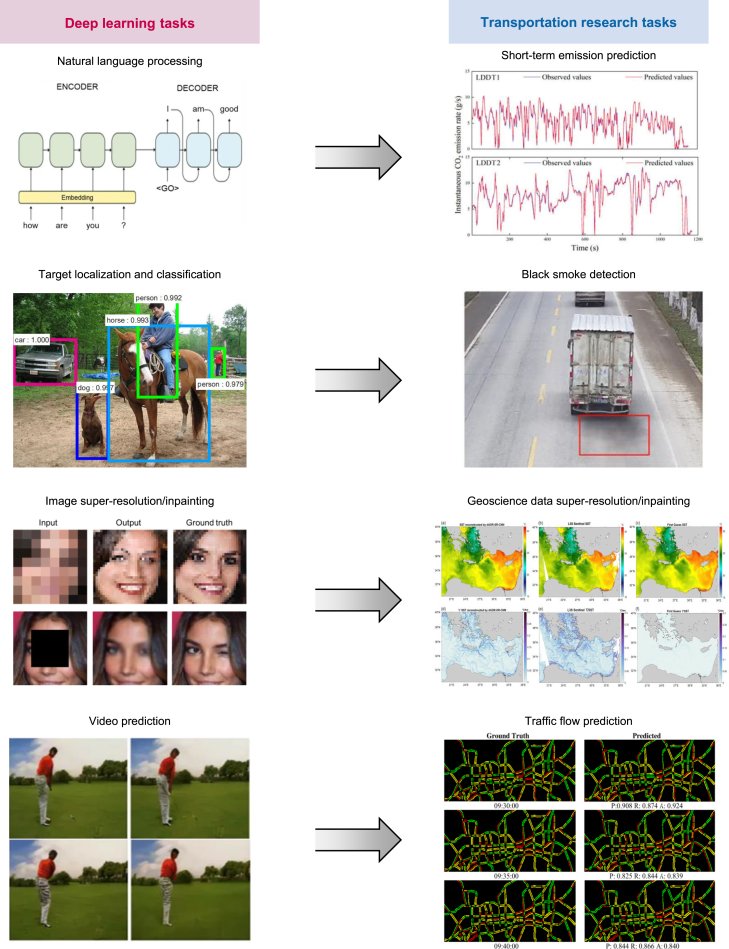

AI models are generally classified into discrete models for classification and continuous models for regression. While ML is widely used in transportation, DL remains in its nascent stages but offers great promise for addressing challenges such as classification, anomaly detection, regression, and state predictions involving spatial or temporal dependencies. The similarity between the data types typically processed by classical DL applications and those in transportation and Earth sciences underscores the potential for incorporating DL into traffic science. As depicted in Figure 4, classification and regression are key challenges common across various fields, such as natural language processing, computer vision, and transportation science. This section outlines the primary AI applications in transportation emissions, categorized by transportation big data types.

Figure 4.

Applications of classical deep learning for transportation problems

Images for short-term emission prediction, geoscience data super-resolution/inpainting, and traffic flow prediction are from Li et al.,67 Fanelli et al.,68 and Ranjan et al.69

Applications in transportation emissions

The collection of operational data from on-board measurements, including PEMS, plume chasing, and OBD, has revealed discrepancies between empirical data and theoretical model predictions. Research indicates that engine-related factors,70,71 along with external variables, such as road gradient,72 road type,73 and atmospheric temperature,74 significantly influence vehicle emissions and are often overlooked in traditional models.70,71 Studies relying on mathematical statistics and linear regression for single-factor correlation analysis often overlook the complex interactions influencing mobile source emissions. This limitation has spurred the adoption of ML methods paired with interpretable models, such as ensemble tree algorithms, like random forest75 and gradient boosting machine,76 valued for their clarity through treelike flowchart representations. These models quantify each factor’s contribution to real-world vehicle emissions, offering critical insights to enhance empirical models. Artificial neural networks (ANNs) are also widely used, providing superior predictive accuracy compared with tree-based models but lacking interpretability.77,78,79 Recent innovations, such as the Shapley additive explanations26 framework, have improved ML interpretability by assigning importance values to features and being broadly applicable. In addition, some studies estimate fuel consumption to derive emission predictions.80,81,82

AI models are also applied to time-series prediction using on-board measurements. Mobile source emissions display long-term temporal dependencies, and delays between emission measurements and engine conditions can cause persistent errors despite time alignment. As a result, relying solely on current data may be insufficient for accurate predictions. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) address this issue by leveraging previous states to inform current state learning, making them well suited for time-series data.83 RNNs are limited by the vanishing and exploding gradient problem, which hinders their performance on long time-series data. To overcome this, long short-term memory networks (LSTMs)84 and other RNN variants were developed. LSTMs are highly effective in capturing sequential dependencies, making them particularly useful in applications such as natural language processing. In atmospheric science, LSTMs have been used for real-time air pollution85 and carbon emission predictions.86 Similarly, for vehicle emissions, LSTMs, their variants, and hybrid models have been employed for emission forecasting.67,87,88

Trajectory and road network monitoring data are used to develop emission inventories with spatiotemporal attributes or supplement existing ones. However, widespread sensor deployment across road networks is prohibitively expensive, resulting in geographic sparsity, and trajectory data also often face signal loss and quality issues. AI approaches addressing these challenges include traffic flow prediction,89 data reconstruction,90 trajectory prediction,91 and transportation mode recognition.92,93 These studies leverage ML techniques to reframe ITS data and incorporate them with emission models, producing high-resolution emission inventories. In addition, large-scale ITS datasets have been directly used to predict traffic-related CO2 emissions.94,95

With the evolution of data characterization from one-dimensional to more complex, high-dimensional forms, big data offer a more detailed understanding of transportation modes, allowing for in-depth analysis of intricate spatial relationships. In two-dimensional data, processes at specific points are often impacted by factors related to the system’s state that are not directly observable. For instance, determining if pollutant levels, such as vehicle black smoke, exceed permissible limits cannot be based solely on the local pixel values of the smoke. It also necessitates accounting for surrounding pixels, such as those representing the background or shadows. Traditional ML methods rely on handcrafted domain-specific features,96 such as terrain shapes and image textures, to incorporate spatial backgrounds and address temporal dependencies. These features serve as inputs for ML tasks, such as localization, classification, and detection. While handcrafted features offer interpretative control, they are limited by time-consuming, domain-specific processes and suboptimal utilization of spatial dependencies.

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in DL models excel at automatically identifying complex patterns and relationships. For classification tasks, CNNs are widely employed to detect black smoke from vehicles in surveillance footage,97,98 improving the efficiency of automatic detection for high-emission vehicles. Traditional object detection models, such as Faster R-CNN99 and YOLO,100 are suitable for interdisciplinary research. In regression tasks, CNNs are primarily applied to geoscientific data, offering essential data for CO2 emission calculations rather than directly detecting emissions. Two primary applications are image super-resolution and inpainting. As noted, the current spatial resolution of CO2 satellite observations is inadequate for isolating the impact of traffic-related emissions. Achieving higher resolution is essential to address this limitation. Image super-resolution involves generating high-resolution images from low-resolution ones and has been applied to various remote sensing datasets, including optical satellite101 and climatological data,68,102 particularly for CO2 satellite observations with significant missing values. Image inpainting focuses on filling missing image segments and has been primarily used in photographs, paintings, and satellite images related to geoscience.103,104 For these regression tasks, models utilizing generative adversarial networks (GANs),105 such as SRGAN for super-resolution106 and the GAN-based model for inpainting,106 are recommended. However, the use of super-resolution and inpainting techniques for CO2 satellite observations is limited due to a lack of high-resolution, complete CO2 datasets for training.

In addition, DL extends beyond computer vision to natural language processing by combining CNNs with LSTMs. A notable example is predicting human behavior in videos, which shares significant similarities with transportation problems that involve strong spatiotemporal dependencies, such as detecting suspected black smoke across multiple frames107 and forecasting dynamic traffic flow in road networks.69,108,109

Challenges and frontiers

The use of big data and AI in transportation encounters challenges related to algorithms, data, and computing costs. Current algorithms need enhancements in adaptability and interpretability to manage complex patterns. Reliable big data are crucial for model construction, validation, and optimization. In addition, efficiently processing vast data within limited computational resources remains a significant challenge.

Algorithm

AI models may closely match observed data but can produce physically inconsistent or unreliable predictions due to extrapolation or observational bias. Traditionally, physical modeling and AI have been seen as separate fields with distinct methodologies. Physical models provide direct interpretability and the ability to extrapolate beyond observations, while data-driven approaches can uncover hidden patterns across various datasets. In practice, these methods often complement each other, and the integration of physical models with AI is gaining increasing recognition.110,111 For instance, Liu et al. enhanced the MOVES model by incorporating a random forest trained with PEMS data, thus reducing emission rate biases and enabling its application in other countries.75 By contrast, Seo et al. focused on AI models, training an ANN using engine parameters from a vehicle dynamics model, constrained by real driving emission data.78

Enhancing prediction accuracy is essential but insufficient. While AI models excel in complex tasks, their “black-box” nature complicates interpretation. Due to the complexity of the environment-activity-emission nexus, tracing model decisions to their assumptions is challenging. However, a detailed understanding of model decision-making can be achieved by focusing on three aspects: pre-modeling, modeling-level, and post-modeling interpretability methods. The first two categories involve data preprocessing to analyze data distribution or designing inherently interpretable models, both aiding in optimal modeling solutions. The third category addresses DL models by employing techniques such as hidden layer analysis,112 agent-based modeling,113 and sensitivity analysis.114

Striking a balance between model performance and interpretability is essential. For traffic flow prediction, the primary emphasis is on achieving high prediction accuracy, as these data are typically used to construct emission inventories through classical emission models. However, in emission predictions based on operational conditions, while accuracy remains important, model interpretability becomes critical for understanding the factors influencing emissions.

Big data

AI models, with their complex and deep architectures, demand extensive ground-truth data for development.115 Unlike applications in chemistry, medicine, or biology, transportation science faces challenges with data volume, quality, and balance, limiting the scope of deep integration. Addressing these limitations requires extensive research. To leverage data challenges in transportation science, it is essential to develop standardized annotated databases and establish a comprehensive knowledge-based sample library encompassing diverse attributes for each sample. Key obstacles include the scarcity of openly accessible datasets and the lack of long-term collaborative sharing frameworks. While thousands of studies explore AI applications in transportation, access to raw data remains limited. While satellite observation data are publicly available, they are not tailored to the needs of transportation science. The limited availability of shared data significantly restricts the full potential of AI in transportation science.

Enriching and standardizing annotated databases through the creation of a comprehensive, attribute-rich sample library is essential, as inconsistencies in data collection methods, preprocessing techniques, and reference systems often lead to systematic errors, significantly complicating the data preparation process. Addressing these “data silos” and ensuring seamless integration demand coordinated efforts from governments and relevant stakeholders. In addition to securing high-quality data for current AI methods, it is crucial to innovate AI techniques to adapt to dynamic datasets. Given AI’s dependence on data, algorithms and applications must evolve with shifting data characteristics. For instance, transfer learning enables models to operate effectively when training and test data differ, eliminating the need for complete retraining in the target domain. Just as the growth of DL in computer vision was fueled by high-dimensional data, continuous advances in AI methodologies remain vital.

Computational costs

The increasing computational demands of processing transportation data, characterized by their vast spatiotemporal scale, present significant challenges. With global data volumes rapidly expanding, daily analysis will soon involve managing petabyte-scale datasets. For instance, traffic flow data in megacities, such as Chengdu, China, now exceed hundreds of millions of entries per day. Similarly, high-resolution satellite imagery used in transportation analysis imposes an even greater computational burden on AI systems, further complicating data processing.

High-performance and distributed computing offers a direct solution by leveraging local or geographically dispersed resources for computational tasks. Consequently, these approaches may surpass the capabilities of transportation science researchers. An alternative is lightweight DL, which improves computational efficiency by simplifying model complexity and reducing parameters. Techniques such as pruning, quantization, knowledge distillation, and network optimization reduce computational and storage demands while preserving model performance, making them ideal for resource-limited devices.116,117

Discussion

The integration of transportation big data and AI will transform transportation systems and advance our understanding of transportation CO2 emissions. Advances in big data technologies offer a robust foundation for emission modeling and prediction. Physical models offer theoretical frameworks and parameters, while AI models, through pattern recognition, refine these models, improving predictions to better reflect real-world conditions.

To improve the spatiotemporal resolution of emission inventories, AI models in transportation should leverage expansive foundational big data, particularly ITS data. AI technologies can process or reconstruct these datasets to uncover richer traffic dynamics and effectively support the development of emission inventories with higher spatiotemporal resolution. Simultaneously, satellite technology offers the potential for large-scale CO2 emission estimation beyond traditional ITS data coverage. However, high-quality satellite data reconstruction requires advanced AI capabilities. By embracing the latest advancements in computer science and fostering interdisciplinary innovation, the full potential of big data can be realized for high-resolution insights into transportation emissions.

The use of big data and AI in transportation science offers both challenges and opportunities for innovation. Interdisciplinary collaboration is key to advancing technology and facilitating data sharing. Addressing privacy and security concerns, along with establishing technical standards, is essential for building trust in AI and big data applications. Unified standards will ensure system interoperability, driving efficiency and intelligent integration within the industry.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42325505 and U2233203 to H.L.), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2022YFC3704200), the Tsinghua University Initiative Scientific Research Program, the Tsinghua University-Toyota Research Center, and the International Council on Clean Transportation.

Author contributions

Z. Luo and H.L. conceptualized the article. All authors wrote the original draft and reviewed and edited the article. H.L. provided funding acquisition.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Biographies

About the authors

Zhenyu Luo is a postdoctoral researcher in environmental science and engineering at Tsinghua University. He earned his PhD in environmental science and engineering from Tsinghua University and his ME and BE degrees in information engineering from the Nanjing Research Institute of Electronics Technology and Northwestern Polytechnical University, respectively. His research interests include the interaction between transportation activities and air pollution, satellite data analysis and emissions inversion, and artificial intelligence prediction.

Tingkun He is a doctoral student at the School of Environment at Tsinghua University. He received a BE in environmental engineering from the Harbin Institute of Technology. His research interest is in the area of emission simulation from ammonia-fueled ships based on AIS big data and its shock on the planetary nitrogen boundary through marine-atmosphere exchange.

Zhaofeng Lv holds a PhD in environmental science and engineering and is currently a postdoctoral researcher at Tsinghua University. His research focuses on the development of emission inventories for key industries, air quality modeling, and the application of big data and artificial intelligence in environmental studies. He has led projects under the National Natural Science Foundation of China and sub-projects under the National Key R&D Program.

Junchao Zhao received his PhD in environmental science and engineering from Tsinghua University and received his MS and BS degrees in environmental engineering from Northwest A&F University. His research focuses on carbon and air pollutant emissions from vehicles and their impacts on atmospheric environments and human health.

Zhining Zhang received her PhD in environmental science and engineering from Tsinghua University. Her research focused on the multi-pollutant emissions and atmospheric impacts within transport sectors.

Yongyue Wang is a PhD candidate at the School of Environment, Tsinghua University. He obtained his BS degree in environmental science from Nankai University. His primary research focuses on detailed simulation of air pollution at the urban street scale and accurate assessment of population exposure. He has a keen interest in the coupled development of small-scale supervision models and the construction of population mobility exposure characteristics.

Wen Yi is a PhD candidate at Tsinghua University. Her research interest is in the area of shipping emission inventory, international shipping decarbonization pathways, Arctic shipping emission projections, and associated atmospheric impacts. She has earned a BE in environmental engineering from Renmin University of China.

Shangshang Lu is a master’s student at the School of Environment, Tsinghua University, and previously earned a bachelor’s degree in environmental engineering from Tsinghua University. His research focuses on the assessment of medium- and long-term emission reduction measures in global shipping.

Kebin He is an academician of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, the director of the Tsinghua University Institute for Carbon Neutrality, and a professor and doctoral supervisor at the School of Environment, Tsinghua University. His research focuses on the identification of atmospheric particulate matter and complex pollution, the emission characteristics of complex sources, multi-pollutant coordinated control, and the synergy between air pollution control and greenhouse gas mitigation.

Huan Liu is a professor and doctoral supervisor at the School of Environment, Tsinghua University. She has been recognized in prestigious talent programs, including the National Natural Science Foundation of China Outstanding Youth Fund and the Newton Advanced Fellowship. Her research focuses on improving the understanding and predictability of contemporary atmospheric environments through the coupling of material flows, transportation, and atmospheric systems, including the interactions between transportation activities, air pollution, and climate change; decision-making for air pollution prevention and control; and forecasting and pathway development for net-zero emission transportation systems.

References

- 1.Shukla P.R., Skea J., Slade R., Al Khourdajie A., Van Diemen R., McCollum D., Pathak M., Some S., Vyas P., Fradera R. Climate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of Working Group III to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2022;10 https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ritchie, H. (2020).Cars, planes, trains: where do CO2 emissions from transport come from? https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions-from-transport/.

- 3.Sims R., Schaeffer R., Creutzig F., Cruz-Núñez X., D’Agosto M., Dimitriu D., Figueroa Meza M.J., Fulton L., Kobayashi S., Lah O., et al. Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change: Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press; 2014. Transport. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng F., Lv Z., Qi L., Wang X., Shi M., Liu H. A big data approach to improving the vehicle emission inventory in China. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2801. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16579-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao J., Lv Z., Qi L., Zhao B., Deng F., Chang X., Wang X., Luo Z., Zhang Z., Xu H., et al. Comprehensive Assessment for the Impacts of S/IVOC Emissions from Mobile Sources on SOA Formation in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022;56:16695–16706. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.2c07265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo Z., Wang Y., Lv Z., He T., Zhao J., Wang Y., Gao F., Zhang Z., Liu H. Impacts of vehicle emission on air quality and human health in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;813 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang S., Xu L.D., Zhu Y., Ahati J., Pei H., Yan J., Liu Z. An integrated system for regional environmental monitoring and management based on internet of things. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2014;10:1596–1605. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reichstein M., Camps-Valls G., Stevens B., Jung M., Denzler J., Carvalhais N., Prabhat f. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature. 2019;566:195–204. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0912-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X., Ge M., Dai X., Ren X., Fritsche M., Wickert J., Schuh H. Accuracy and reliability of multi-GNSS real-time precise positioning: GPS, GLONASS, BeiDou, and Galileo. J. Geod. 2015;89:607–635. doi: 10.1007/s00190-015-0802-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y. 2018 International Conference on Intelligent Transportation, Big Data Smart City. IEEE; 2018. Big data technology and its analysis of application in urban intelligent transportation system; pp. 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agapiou A. Remote sensing heritage in a petabyte-scale: satellite data and heritage Earth Engine© applications. International Journal of Digital Earth. 2017;10:85–102. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allam Z., Dhunny Z.A. On big data, artificial intelligence and smart cities. Cities. 2019;89:80–91. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gómez-Chova L., Tuia D., Moser G., Camps-Valls G. Multimodal classification of remote sensing images: A review and future directions. Proc. IEEE. 2015;103:1560–1584. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cadle S.H., Stephens R.D. Remote sensing of vehicle exhaust emission. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1994;28:258A–264A. doi: 10.1021/es00055a715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma L., Liu Y., Zhang X., Ye Y., Yin G., Johnson B.A. Deep learning in remote sensing applications: A meta-analysis and review. ISPRS J. Photogrammetry Remote Sens. 2019;152:166–177. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang J., Liu F., Wang Y., Wang H. Uncovering urban human mobility from large scale taxi GPS data. Phys. Stat. Mech. Appl. 2015;438:140–153. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia C., Xiang M., Fang K., Li Y., Ye Y., Shi Z., Liu J. Spatial-temporal distribution of carbon emissions by daily travel and its response to urban form: A case study of Hangzhou, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;257 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo X., Dong L., Dou Y., Zhang N., Ren J., Li Y., Sun L., Yao S. Analysis on spatial-temporal features of taxis' emissions from big data informed travel patterns: a case of Shanghai, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017;142:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nyhan M., Sobolevsky S., Kang C., Robinson P., Corti A., Szell M., Streets D., Lu Z., Britter R., Barrett S.R., Ratti C. Predicting vehicular emissions in high spatial resolution using pervasively measured transportation data and microscopic emissions model. Atmos. Environ. 2016;140:352–363. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen B.Y., Liu Q., Gong W., Tao J., Chen H.-P., Shi F.-R. Evaluation of energy-environmental-economic benefits of CNG taxi policy using multi-task deep-learning-based microscopic models and big trajectory data. Travel Behav. Soc. 2024;34 doi: 10.1016/j.tbs.2023.100680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yi W., Wang X., He T., Liu H., Luo Z., Lv Z., He K. High-resolution global shipping emission inventory by Shipping Emission Inventory Model (SEIM) Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2024;2024:1–31. doi: 10.5194/essd-2024-258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo Z., Lv Z., Zhao J., Sun H., He T., Yi W., Zhang Z., He K., Liu H. Shipping-related pollution decreased but mortality increased in Chinese port cities. Nat. Cities. 2024;1:295–304. doi: 10.1038/s44284-024-00050-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quadros F.D.A., Snellen M., Sun J., Dedoussi I.C. Global civil aviation emissions estimates for 2017–2020 using ADS-B data. J. Aircraft. 2022;59:1394–1405. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filippone A., Parkes B., Bojdo N., Kelly T. Prediction of aircraft engine emissions using ADS-B flight data. Aeronaut. J. 2021;125:988–1012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J., Zhang S., Zhang X., Wang J., Wu Y., Hao J. Developing a high-resolution emission inventory of China’s aviation sector using real-world flight trajectory data. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022;56:5743–5752. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c08741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teoh R., Engberg Z., Shapiro M., Dray L., Stettler M.E.J. The high-resolution Global Aviation emissions Inventory based on ADS-B (GAIA) for 2019–2021. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024;24:725–744. doi: 10.5194/acp-24-725-2024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yi W., He T., Wang X., Soo Y.H., Luo Z., Xie Y., Peng X., Zhang W., Wang Y., Lv Z., et al. Ship emission variations during the COVID-19 from global and continental perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2024;954 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.176633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lv Z., Wang X., Deng F., Ying Q., Archibald A.T., Jones R.L., Ding Y., Cheng Y., Fu M., Liu Y., et al. Source–receptor relationship revealed by the halted traffic and aggravated haze in Beijing during the COVID-19 lockdown. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:15660–15670. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c04941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallus J., Kirchner U., Vogt R., Benter T. Impact of driving style and road grade on gaseous exhaust emissions of passenger vehicles measured by a Portable Emission Measurement System (PEMS) Transport. Res. Transport Environ. 2017;52:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2017.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vojtisek-Lom M., Zardini A.A., Pechout M., Dittrich L., Forni F., Montigny F., Carriero M., Giechaskiel B., Martini G. A miniature Portable Emissions Measurement System (PEMS) for real-driving monitoring of motorcycles. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2020;13:5827–5843. doi: 10.5194/amt-13-5827-2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kousoulidou M., Fontaras G., Ntziachristos L., Bonnel P., Samaras Z., Dilara P. Use of portable emissions measurement system (PEMS) for the development and validation of passenger car emission factors. Atmos. Environ. 2013;64:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.09.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H., Zhang S., Wu X., Wen Y., Li Z., Wu Y. Emission Measurements on a Large Sample of Heavy-Duty Diesel Trucks in China by Using Mobile Plume Chasing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023;57:15153–15161. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.3c03028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau C.F., Rakowska A., Townsend T., Brimblecombe P., Chan T.L., Yam Y.S., Močnik G., Ning Z. Evaluation of diesel fleet emissions and control policies from plume chasing measurements of on-road vehicles. Atmos. Environ. 2015;122:171–182. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pirjola L., Pajunoja A., Walden J., Jalkanen J.-P., Rönkkö T., Kousa A., Koskentalo T. Mobile measurements of ship emissions in two harbour areas in Finland. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2014;7:149–161. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ausmeel S., Eriksson A., Ahlberg E., Sporre M.K., Spanne M., Kristensson A. Ship plumes in the Baltic Sea Sulfur Emission Control Area: chemical characterization and contribution to coastal aerosol concentrations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020;20:9135–9151. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westerlund J., Hallquist M., Hallquist Å.M. Characterization of fleet emissions from ships through multi-individual determination of size-resolved particle emissions in a coastal area. Atmos. Environ. 2015;112:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.04.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lv Z., Zhang Y., Ji Z., Deng F., Shi M., Li Q., He M., Xiao L., Huang Y., Liu H., He K. A real-time NOx emission inventory from heavy-duty vehicles based on on-board diagnostics big data with acceptable quality in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023;422 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hao L., Ren Y., Lu W., Jiang N., Ge Y., Wang Y. Assessment of Heavy-Duty Diesel Vehicle NOx and CO2 Emissions Based on OBD Data. Atmosphere. 2023;14:1417. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang L., Zhang S., Wu Y., Chen Q., Niu T., Huang X., Zhang S., Zhang L., Zhou Y., Hao J. Evaluating real-world CO2 and NOX emissions for public transit buses using a remote wireless on-board diagnostic (OBD) approach. Environ. Pollut. 2016;218:453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Müller V., Pieta H., Schaub J., Ehrly M., Körfer T. On-Board Monitoring to meet upcoming EU-7 emission standards–Squaring the circle between effectiveness and robust realization. Transport Eng. 2022;10 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barbier A., Salavert J.M., Palau C.E., Guardiola C. Analysis of the Euro 7 on-board emissions monitoring concept with real-driving data. Transport. Res. Transport Environ. 2024;127 doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2024.104062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawson D.R., Groblicki P.J., Stedman D.H., Bishop G.A., Guenther P.L. Emissions from lit-use motor vehicles in Los Angeles: A pilot study of remote sensing and the inspection and maintenance program. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 1990;40:1096–1105. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ko Y.-W., Cho C.-H. Characterization of large fleets of vehicle exhaust emissions in middle Taiwan by remote sensing. Sci. Total Environ. 2006;354:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y., Borken-Kleefeld J. Real-driving emissions from cars and light commercial vehicles–Results from 13 years remote sensing at Zurich/CH. Atmos. Environ. 2014;88:157–164. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pujadas M., Domínguez-Sáez A., De la Fuente J. Real-driving emissions of circulating Spanish car fleet in 2015 using RSD Technology. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;576:193–209. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y., Bishop G.A., Stedman D.H. Automobile emissions are statistically gamma distributed. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1994;28:1370–1374. doi: 10.1021/es00056a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou Y., Wu Y., Zhang S., Fu L., Hao J. Evaluating the emission status of light-duty gasoline vehicles and motorcycles in Macao with real-world remote sensing measurement. J. Environ. Sci. 2014;26:2240–2248. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ning Z., Chan T.L. On-road remote sensing of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) vehicle emissions measurement and emission factors estimation. Atmos. Environ. 2007;41:9099–9110. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang H., Chen K., Li Y. Automatic Detection Method for Black Smoke Vehicles Considering Motion Shadows. Sensors. 2023;23:8281. doi: 10.3390/s23198281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen X., Jiang L., Xia Y., Wang L., Ye J., Hou T., Zhang Y., Li M., Li Z., Song Z., et al. Quantifying on-road vehicle emissions during traffic congestion using updated emission factors of light-duty gasoline vehicles and real-world traffic monitoring big data. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;847 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kheirbek I., Haney J., Douglas S., Ito K., Matte T. The contribution of motor vehicle emissions to ambient fine particulate matter public health impacts in New York City: a health burden assessment. Environ. Health. 2016;15:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12940-016-0172-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hall D.L., Anderson D.C., Martin C.R., Ren X., Salawitch R.J., He H., Canty T.P., Hains J.C., Dickerson R.R. Using near-road observations of CO, NOy, and CO2 to investigate emissions from vehicles: Evidence for an impact of ambient temperature and specific humidity. Atmos. Environ. 2020;232 doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zavala M., Herndon S.C., Wood E.C., Onasch T.B., Knighton W.B., Marr L.C., Kolb C.E., Molina L.T. Evaluation of mobile emissions contributions to Mexico City's emissions inventory using on-road and cross-road emission measurements and ambient data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009;9:6305–6317. doi: 10.5194/acp-9-6305-2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parrish D.D., Trainer M., Hereid D., Williams E.J., Olszyna K.J., Harley R.A., Meagher J.F., Fehsenfeld F.C. Decadal change in carbon monoxide to nitrogen oxide ratio in US vehicular emissions. J. Geophys. Res. 2002;107 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fujita E.M., Croes B.E., Bennett C.L., Lawson D.R., Lurmann F.W., Main H.H. Comparison of emission inventory and ambient concentration ratios of CO, NMOG, and NOx in California's South Coast Air Basin. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 1992;42:264–276. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sheng M., Lei L., Zeng Z.-C., Rao W., Song H., Wu C. Global land 1° mapping dataset of XCO2 from satellite observations of GOSAT and OCO-2 from 2009 to 2020. Big Earth Data. 2023;7:170–190. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sheng, M., Lei, L., Zeng, Z.-C., Weiqiang, R., Hao, S., and Wu, C. (2021).Global land 1° mapping XCO2 dataset using satellite observations of GOSAT and OCO-2 from 2009 to 2020. Version V4. Harvard Dataverse. 10.7910/DVN/4WDTD8. [DOI]

- 58.Yang S., Lei L., Zeng Z., He Z., Zhong H. An assessment of anthropogenic CO2 emissions by satellite-based observations in China. Sensors. 2019;19:1118. doi: 10.3390/s19051118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vinken G.C.M., Boersma K.F., Van Donkelaar A., Zhang L. A. and Zhang, L., 2014. Constraints on ship NO x emissions in Europe using GEOS-Chem and OMI satellite NO 2 observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014;14:1353–1369. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zheng B., Geng G., Ciais P., Davis S.J., Martin R.V., Meng J., Wu N., Chevallier F., Broquet G., Boersma F., et al. Satellite-based estimates of decline and rebound in China’s CO2 emissions during COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Adv. 2020;6 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd4998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dou X., Wang Y., Ciais P., Chevallier F., Davis S.J., Crippa M., Janssens-Maenhout G., Guizzardi D., Solazzo E., Yan F., et al. Near-real-time global gridded daily CO2 emissions. Innovation. 2022;3 doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu D., Lin J.C., Fasoli B., Oda T., Ye X., Lauvaux T., Yang E.G., Kort E.A. A Lagrangian approach towards extracting signals of urban CO 2 emissions from satellite observations of atmospheric column CO 2 (XCO 2): X-Stochastic Time-Inverted Lagrangian Transport model (“X-STILT v1”) Geosci. Model Dev. (GMD) 2018;11:4843–4871. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang E.G., Kort E.A., Wu D., Lin J.C., Oda T., Ye X., Lauvaux T. Using space-based observations and Lagrangian modeling to evaluate urban carbon dioxide emissions in the Middle East. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2020;125 doi: 10.1029/2019JD031922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bovensmann H., Buchwitz M., Burrows J.P., Reuter M., Krings T., Gerilowski K., Schneising O., Heymann J., Tretner A., Erzinger J. A remote sensing technique for global monitoring of power plant CO 2 emissions from space and related applications. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2010;3:781–811. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nassar R., Hill T.G., McLinden C.A., Wunch D., Jones D.B.A., Crisp D. Quantifying CO2 emissions from individual power plants from space. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017;44:10045–10053. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luo Z., He T., Yi W., Zhao J., Zhang Z., Wang Y., Liu H., He K. Advancing shipping NO x pollution estimation through a satellite-based approach. PNAS Nexus. 2024;3 doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li S., Tong Z., Haroon M. Estimation of transport CO2 emissions using machine learning algorithm. Transport. Res. Transport Environ. 2024;133 doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2024.104276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fanelli C., Ciani D., Pisano A., Buongiorno Nardelli B. Deep learning for the super resolution of Mediterranean sea surface temperature fields. Ocean Sci. 2024;20:1035–1050. doi: 10.5194/os-20-1035-2024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ranjan N., Bhandari S., Zhao H.P., Kim H., Khan P. City-wide traffic congestion prediction based on CNN, LSTM and transpose CNN. IEEE Access. 2020;8:81606–81620. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang Z., Liu Y., Wu L., Martinet S., Zhang Y., Andre M., Mao H. Real-world gaseous emission characteristics of Euro 6b light-duty gasoline-and diesel-fueled vehicles. Transport. Res. Transport Environ. 2020;78 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yu Q., Yang Y., Xiong X., Sun S., Liu Y., Wang Y. Assessing the impact of multi-dimensional driving behaviors on link-level emissions based on a Portable Emission Measurement System (PEMS) Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2021;12:414–424. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang L., Hu X., Qiu R., Lin J. Comparison of real-world emissions of LDGVs of different vehicle emission standards on both mountainous and level roads in China. Transport. Res. Transport Environ. 2019;69:24–39. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang H., Wu Y., Zhang K.M., Zhang S., Baldauf R.W., Snow R., Deshmukh P., Zheng X., He L., Hao J. Evaluating mobile monitoring of on-road emission factors by comparing concurrent PEMS measurements. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;736 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhai Z., Tu R., Xu J., Wang A., Hatzopoulou M. Capturing the variability in instantaneous vehicle emissions based on field test data. Atmosphere. 2020;11:765. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu R., He H.-d., Zhang Z., Wu C.-l., Yang J.-m., Zhu X.-h., Peng Z.-r. Integrated MOVES model and machine learning method for prediction of CO2 and NO from light-duty gasoline vehicle. J. Clean. Prod. 2023;422 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhu X.-h., He H.-d., Lu K.-f., Peng Z.-r., Gao H.O. Characterizing carbon emissions from China V and China VI gasoline vehicles based on portable emission measurement systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2022;378 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Donateo T., Filomena R. Real time estimation of emissions in a diesel vehicle with neural networks. E3S Web Conf. 2020;197:6020. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Seo J., Yun B., Park J., Park J., Shin M., Park S. Prediction of instantaneous real-world emissions from diesel light-duty vehicles based on an integrated artificial neural network and vehicle dynamics model. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;786 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ay C., Seyhan A., Bal Beşikçi E. Quantifying ship-borne emissions in Istanbul Strait with bottom-up and machine-learning approaches. Ocean Eng. 2022;258 doi: 10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.111864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yan R., Mo H., Wang S., Yang D. Analysis and prediction of ship energy efficiency based on the MRV system. Marit. Pol. Manag. 2023;50:117–139. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yan R., Wang S., Du Y. Development of a two-stage ship fuel consumption prediction and reduction model for a dry bulk ship. Transport. Res. E Logist. Transport. Rev. 2020;138 doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2020.101930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shahariar G.M.H., Bodisco T.A., Surawski N., Komol M.M.R., Sajjad M., Chu-Van T., Ristovski Z., Brown R.J. Real-driving CO2, NOx and fuel consumption estimation using machine learning approaches. Energy (Calg.) 2023;1 doi: 10.1016/j.nxener.2023.100060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Arsie I., Marra D., Pianese C., Sorrentino M. Real-time estimation of engine NOx emissions via recurrent neural networks. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2010;43:228–233. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Di Mascio P., Di Vito M., Loprencipe G., Ragnoli A. Procedure to determine the geometry of road alignment using GPS data. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012;53:1202–1215. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xayasouk T., Lee H., Lee G. Air pollution prediction using long short-term memory (LSTM) and deep autoencoder (DAE) models. Sustainability. 2020;12:2570. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang X., Yan C., Liu W., Liu X. Research on Carbon Emissions Prediction Model of Thermal Power Plant Based on SSA-LSTM Algorithm with Boiler Feed Water Influencing Factors. Sustainability. 2022;14 [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xie H., Zhang Y., He Y., You K., Fan B., Yu D., Lei B., Zhang W. Parallel attention-based LSTM for building a prediction model of vehicle emissions using PEMS and OBD. Measurement. 2021;185 doi: 10.1016/j.measurement.2021.110074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Al-Nefaie A.H., Aldhyani T.H.H. Predicting CO2 Emissions from Traffic Vehicles for Sustainable and Smart Environment Using a Deep Learning Model. Sustainability. 2023;15:7615. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lv Y., Duan Y., Kang W., Li Z.X., Wang F. Traffic Flow Prediction With Big Data: A Deep Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 2015;16:865–873. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wen Y., Wu R., Zhou Z., Zhang S., Yang S., Wallington T.J., Shen W., Tan Q., Deng Y., Wu Y. A data-driven method of traffic emissions mapping with land use random forest models. Appl. Energy. 2022;305 doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117916. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang Y., Watanabe D., Hirata E., Toriumi S. Real-Time Management of Vessel Carbon Dioxide Emissions Based on Automatic Identification System Database Using Deep Learning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021;9:871. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mäenpää H., Lobov A., Martinez Lastra J.L. Travel mode estimation for multi-modal journey planner. Transport. Res. C Emerg. Technol. 2017;82:273–289. doi: 10.1016/j.trc.2017.06.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stenneth L., Wolfson O., Yu P.S., Xu B. Proceedings of the 19th ACM SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems. Association for Computing Machinery; 2011. Transportation mode detection using mobile phones and GIS information; pp. 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Khajavi H., Rastgoo A. Predicting the carbon dioxide emission caused by road transport using a Random Forest (RF) model combined by Meta-Heuristic Algorithms. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023;93 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2023.104503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lu X., Ota K., Dong M., Yu C., Jin H. Predicting transportation carbon emission with urban big data. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Comput. 2017;2:333–344. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lee J., Weger R.C., Sengupta S.K., Welch R.M. A neural network approach to cloud classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Rem. Sens. 1990;28:846–855. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang C., Wang H., Yu F., Xia W. 2021 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Industrial Design. IEEE; 2021. A high-precision fast smoky vehicle detection method based on improved Yolov5 network; pp. 255–259. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Khan S.H., Bennamoun M., Sohel F., Togneri R. 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE; 2014. Automatic feature learning for robust shadow detection; pp. 1939–1946. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ren S., He K., Girshick R., Sun J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017;39:1137–1149. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Redmon J. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE; 2016. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pouliot D., Latifovic R., Pasher J., Duffe J. Landsat Super-Resolution Enhancement Using Convolution Neural Networks and Sentinel-2 for Training. Remote Sens. 2018;10:394. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stengel K., Glaws A., Hettinger D., King R.N. Adversarial super-resolution of climatological wind and solar data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:16805–16815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1918964117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dong J., Yin R., Sun X., Li Q., Yang Y., Qin X. Inpainting of remote sensing SST images with deep convolutional generative adversarial network. Geosci. Rem. Sens. Lett. IEEE. 2019;16:173–177. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kadow C., Hall D.M., Ulbrich U. Artificial intelligence reconstructs missing climate information. Nat. Geosci. 2020;13:408–413. doi: 10.1038/s41561-020-0582-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Goodfellow I., Pouget-Abadie J., Mirza M., Xu B., Warde-Farley D., Ozair S., Courville A., Bengio Y. Generative adversarial nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014;27 [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ledig C., Theis L., Huszár F., Caballero J., Cunningham A., Acosta A., Aitken A., Tejani A., Totz J., Wang Z. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE; 2017. Photo-realistic single image super-resolution using a generative adversarial network; pp. 4681–4690. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cao Y., Lu X. Learning spatial-temporal representation for smoke vehicle detection. Multimed. Tool. Appl. 2019;78:27871–27889. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bogaerts T., Masegosa A.D., Angarita-Zapata J.S., Onieva E., Hellinckx P. A graph CNN-LSTM neural network for short and long-term traffic forecasting based on trajectory data. Transport. Res. C Emerg. Technol. 2020;112:62–77. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cao M., Li V.O., Chan V.W. 2020 IEEE 91st Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2020-Spring) IEEE; 2020. A CNN-LSTM model for traffic speed prediction; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Karpatne A., Atluri G., Faghmous J.H., Steinbach M., Banerjee A., Ganguly A., Shekhar S., Samatova N., Kumar V. Theory-guided data science: A new paradigm for scientific discovery from data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2017;29:2318–2331. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Camps-Valls G., Martino L., Svendsen D.H., Campos-Taberner M., Muñoz-Marí J., Laparra V., Luengo D., García-Haro F.J. Physics-aware Gaussian processes in remote sensing. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018;68:69–82. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ham Y.-G., Kim J.-H., Luo J.-J. Deep learning for multi-year ENSO forecasts. Nature. 2019;573:568–572. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1559-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chen R., Chen H., Ren J., Huang G., Zhang Q. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. IEEE; 2019. Explaining neural networks semantically and quantitatively; pp. 9187–9196. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang S., Ren Y., Xia B., Liu K., Li H. Prediction of atmospheric pollutants in urban environment based on coupled deep learning model and sensitivity analysis. Chemosphere. 2023;331 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.138830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yuan Q., Shen H., Li T., Li Z., Li S., Jiang Y., Xu H., Tan W., Yang Q., Wang J., et al. Deep learning in environmental remote sensing: Achievements and challenges. Rem. Sens. Environ. 2020;241 [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lan Z. Albert: A lite BERT for self-supervised learning of language representations. arXiv. 2019 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1909.11942. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Howard A.G. MobileNets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv. 2017 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1704.04861. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]