Abstract

Members of the copper uptake transporter (CTR) family from yeast, plants, and mammals including human are required for cellular uptake of the essential metal copper. Based on biochemical data, CTRs have three transmembrane domains and have been shown to oligomerize in the membrane. Among individual members of the family, there is little amino acid sequence identity, raising questions as to how these proteins adopt a common fold, oligomerize, and participate in copper transport. Using site-directed mutagenesis, tryptophan scanning, genetic complementation, subcellular localization, chemical cross-linking, and the yeast unfolded protein response, we demonstrated that at least half of the third transmembrane domain (TM3) plays a vital role in CTR structure and function. The results of our analysis showed that TM3 contains two functionally distinct faces. One face bears a highly conserved Gly-X-X-X-Gly (GG4) motif, which we showed to be essential for CTR oligomerization. Moreover, we showed that steric constraints reach past the GG4-motif itself including amino acid residues that are not conserved throughout the CTR family. A second face of TM3 contains three amino acid positions that, when mutated to tryptophan, cause predominantly abnormal localization but are still partially functional in growth complementation experiments. These mutations cluster on the face opposite to the GG4-bearing face of TM3 where they may mediate interactions with the remaining two transmembrane domains. Taken together, our data support TM3 as being buried within trimeric CTR where it plays an essential role in CTR assembly.

Copper is essential for life, because the redox and coordination chemistries of copper ions allow them to participate in key processes such as respiration, clearance of free radicals, and mobilization of iron from the diet (1, 2). Yet, an unregulated excess of cellular copper is toxic and represents the causative link for Menkes and Wilson’s diseases, two copper transport disorders affecting the liver and nervous system (3–5). Moreover, imbalances in copper status have also been proposed to play roles in Alzheimer’s disease (6) and prion disorders such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (7, 8). Essential yet potentially toxic, cellular copper concentrations are tightly regulated by the proteins that transport copper across cellular membranes and copper-specific chaperones that escort the metal ion through the cell for delivery to specific target enzymes (2).

Although the mechanisms of intracellular copper trafficking and copper secretion have been studied in significant detail (reviewed in Ref. 9), little is known regarding the mechanisms and regulation of primary copper acquisition. Initial copper uptake into cells occurs through the CTR1 family of integral membrane proteins, which function in copper uptake in organisms as diverse as yeast, plants, and metazoans including mice and humans (9–12). A large subset of the CTRs representing a wide range of evolutionary origin including Candida albicans CTR1, Arabidopsis thaliana COPT1, Schizosaccharomyces pombe CTR4/5, fly CTR1, lizard CTR1, mouse CTR1, and human CTR1 complement a respiratory defect in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that lack high affinity copper uptake systems (11–17). This ability of numerous CTR proteins to functionally replace endogenous S. cerevisiae Ctr1p and Ctr3p has led to a model in which CTRs themselves act as transporters for copper ions across the plasma membrane.

Recent work (18, 19) showed that, in addition to copper, both the yeast and human CTR1 proteins also mediate the uptake of the anticancer agent, cis-platinum(II)diammine dichloride (cis-platin), into yeast and mammalian cells. This finding creates a puzzle, because the cisplatin molecule and copper ions are structurally unrelated and, hence, the mechanism of transport is probably different for the two substrates. Unfortunately, the structure-function relationships remain poorly understood within the CTR family of membrane proteins. However, based on their amino acid sequences, CTR proteins lack nucleotide-binding domains and are predicted to have three transmembrane α-helices. Initial biochemical characterization of CTR proteins showed that they form oligomers in the membrane (10, 14, 20), that the N termini are located in the extracellular space (21–23), and that most of the potential metal binding motifs in the N-terminal domains of CTR-proteins are not strictly required for transport function (22). Yet, the role of the membrane-spanning domains in copper transport is largely unknown and their study is hampered by the fact that sequence identities between CTR proteins from different evolutionary branches are low. In fact, only two sequence motifs, Met-X-X-X-Met and Gly-X-X-X-Gly (GG4) in the second and third trans-membrane domains (TM2 and TM3), respectively, are invariantly conserved within the membrane embedded domain of all of the CTRs. Recent studies revealed that the Met-X-X-X-Met in TM2 plays a vital role in the chemistry of copper sensing and uptake (22, 24), but the role of the GG4 motif in TM3 has not previously been investigated.

The GG4 motif is statistically overabundant in the transmembrane regions of both single-span and multi-span integral membrane proteins (25). Russ and Engelman (34) have shown that the GG4 motif plays a vital role in stabilizing transmembrane helix-helix interactions and the resulting dimerization of the single transmembrane protein glycophorin A. Similarly, a GG4 motif is involved in helix packing at the interface between subunits in the mechanosensitive channels MscS from Escherichia coli and MscL from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (26, 27). Yet, GG4 motifs do not exclusively mediate membrane protein oligomerization as shown by the crystal structure of the tetrameric E. coli GlpF, a member of the multi-membrane-spanning glycero-aquaporin family where GG4-mediated helix-helix interactions stabilize the fold of a monomer (28, 29). The presence of an invariantly conserved GG4 motif in TM3 of all of the known members of the CTR family suggests an important role of TM3 in the structure-function of CTR transporters. In this work, we demonstrated that the GG4 motif is essential for the formation of fully functional copper uptake proteins in the case of two distantly related members of the CTR family, human CTR1 and yeast CTR3. Our results identified two faces of TM3 that point to a central role of this transmembrane helix for the structural organization of CTR proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression Constructs and Yeast Transformation

The Δctr1,3 yeast strain (MATa ura3 lys2 ade2 trp1 his3 leu2 Δctr1::LEU2), also containing a transposon interfering with Ctr3p expression, and the yeast expression plasmid, pDB20-hCTR1-URA3, were obtained from Dr. Jane Gitschier. The pDB20 multiple cloning site was modified by excision of the insert with HindIII and ligation of two overlapping oligonucleotides containing NheI and MluI restriction sites into the HindIII-linearized vector. To allow immunodetection of human CTR1 (hCTR1), the hemagglutinin (HA) tag (MEYPYDVPDYA) was inserted at the N terminus using an oligonucleotide that encodes the HA epitope and anneals to 18 nucleotides of the hCTR1 open reading frame after the first methionine. A reverse oligonucleotide was synthesized that anneals to 21 nucleotides up to and including the stop codon of hCTR1. The forward and reverse oligonucleotides contained NheI and MluI sites, respectively, and were used to perform high fidelity PCR on the original pDB20-hCTR1 plasmid. PCR products were gel-purified, digested with NheI and MluI, and ligated into the modified pDB20 vector. All of the experiments of human CTR1 and mutants in this investigation were performed using the N-terminally tagged HA-hCTR1 construct. The pRS316-yCTR3-GFP-URA3 plasmid, obtained from Dr. Dennis Thiele, was used as a template to produce mutants for complementation and fluorescence localization. This plasmid was also used for subcloning the insert into the p423GPD vector to produce mutants for tryptophan-scanning experiments. The position of the third transmembrane domain was identified using standard hydropathy analysis to generate mutants for tryptophan-scanning experiments. Plasmid mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and all of the constructs used in this study were verified by nucleotide sequencing. Yeast were transformed using lithium acetate, and plasmids were selected for uracil complementation by plating on minimal dextrose (MD) plates containing dextrose (2%), adenine, histidine, lysine, and tryptophan (all 20 mg/liter) but lacking uracil.

Functional Complementation

The Δctr1,3 yeast strain transformed with plasmids expressing HA-hCTR1, HA-hCTR1G167L, HA-hCTR1G171L, yCTR3-GFP, yCTR3G202L-GFP, or yCTR3G206L-GFP were grown in MD medium lacking uracil to an A600 = 1.2–1.5. Assays were set up essentially as described (11, 12). Yeast were washed once with sterile distilled water and adjusted to an A600 of 1.0 in water. Five serial dilutions (1:10 in succession) were spotted onto YPG (yeast peptone glycerol) plates containing glycerol as the only carbon source (1% (w/v) yeast extract, 2% (w/v) bactopeptone, 3% (v/v) glycerol) supplemented with 80 μm bathocuproinedisulfonic acid (BCS; Sigma) for copper depletion, 50 μm copper sulfate for copper excess, or a third condition having no chelator or additional metal to achieve trace copper levels. Plates containing excess copper (50 μm) were incubated at 30 °C for 3–5 days. Copper-depleted plates were incubated at 30 °C for at least 10 days. Plates were illuminated on a fluorescent light box, and images were taken using digital photography. Human CTR1 and GG4 mutants expressed from both pDB20 and p423GPD (for the unfolded protein response) plasmids were verified by functional complementation and yielded identical results (data not shown).

Fluorescence Microscopy

Wild type yCTR3-GFP fusion protein, yCTR3G202L-GFP, yCTR3G206L-GFP, or TM3 tryptophan-scanning mutants expressed from either pRS316 or p423GPD vectors were grown in minimal dextrose medium. Wild type yCTR3-GFP, yCTR3G202L-GFP, and yCTR3G206L-GFP cultures were incubated in 1 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI; Sigma) for 5 min before visualization on a Nikon TE2000 fluorescence microscope using epiillumination. GFP and DAPI images were captured with a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER CCD camera and then colorized and merged with Adobe Photoshop. Tryptophan scanning was performed with wild type yCTR3-GFP fusion and mutants all expressed from the p423GPD vector.

Cross-linking Analysis

Yeast expressing HA-tagged wild type hCTR1 and HA-hCTR1G167L mutants from Δctr1,3 yeast strain were grown in MD medium to an A600 of 1.0–1.2. Crude membranes were prepared from yeast using glass bead lysis or a Z Plus Series cell disrupter (Constant Systems, Ltd). Membranes were first deglycosylated with PNGase F (New England Biolabs) for HA-hCTR1 for 1 h at 37 °C before solubilization with either 1% Triton X-100 or 1 mm dodecyl-β-d-maltoside in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 200,000 × g for 15 min using a TLA-120 rotor and a Beckman tabletop ultracentrifuge. To partially purify the HA-hCTR1G167L mutant, dodecyl-β-d-maltoside-solubilized material was bound to nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin, eluted with 60 mm imidazole, and concentrated using Centricon® YM-100 centrifugal filter devices (Millipore). The homobifunctional cross-linkers, ethylene glycol succinimidylsuccinimate and dithiobis succinimidylpropionate (both from Sigma), were added to detergent-solubilized protein at a final concentration of 0.25–3 mm and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Reactions were halted by the addition of a primary amine (50 mm Tris, pH 8.0) and incubated for an additional 15 min. Western blotting was performed using mouse monoclonal antiserum anti-HA antibody (Covance Research Products, Inc.), which recognizes the HA tag inserted at the N terminus of human CTR1.

Degradation Assay

Δctr1,3 yeast strain transformed with pDB20 HA-tagged hCTR1 wild type, HA-hCTR1G167L, and HA-hCTR1G171L mutants were grown to A600 = 1.0. Cycloheximide (100 μg/ml final) dissolved in Me2SO was added to halt protein synthesis, and 1-ml samples were removed from the culture at 0, 1, and 3 h. Total protein was extracted essentially as described (30). Samples were spun in a tabletop centrifuge, and the resulting cell pellet was washed once with distilled water. To disrupt the membranes, cells were resuspended in 2 m NaOH, 1.12 m β-mercaptoethanol and incubated for 15 min on ice with occasional vortexing. To precipitate protein, 75 μl of 100% trichloroacetic acid was added and incubated for an additional 20 min on ice. Samples were spun at 16,000 × g in a tabletop centrifuge for 5 min, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample-loading buffer containing 2 mm dithiothreitol for Western blotting.

Yeast-unfolded Protein Response Assay

The pSZ1 plasmid containing the 22-base pair unfolded protein response element (UPRE) upstream of the coding segment for β-galactosidase was provided by Dr. Mark Hochstrasser. pSZ1 was transformed into S. cerevisiae Δctr1,3 yeast strain using selection on minimal dextrose plates lacking uracil. A single clone was used for all of the subsequent transformations of the p423GPD expression vector containing HA-tagged wild type and mutant human CTR1 on MD plates lacking histidine and uracil. Random clones (n = 3) of each construct were selected and grown in minimal dextrose to a mid-log growth phase. Secondary cultures for each mutant were grown from equivalent amounts of cells inoculated from the primary culture and subjected to the UPR assay when A600 ≤ 0.6. The UPR assay was performed as previously described for bacteria (31, 32), including the formula for calculating β-galactosidase activity: β-galactosidase units = 1000 × A420 − (1.75 × A550)/[time of reaction (min) × volume (0.1 ml) × A600].

RESULTS

Requirement of the GG4 Motif for Growth Complementation

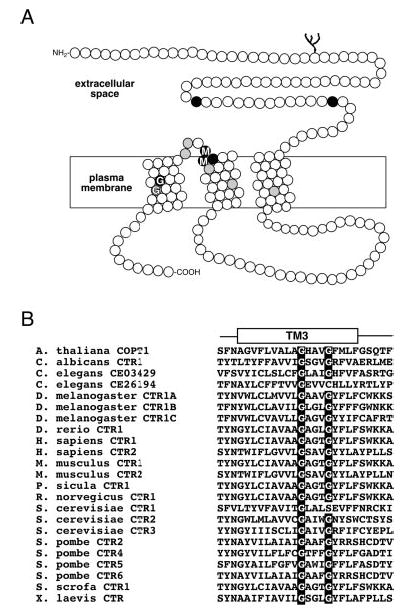

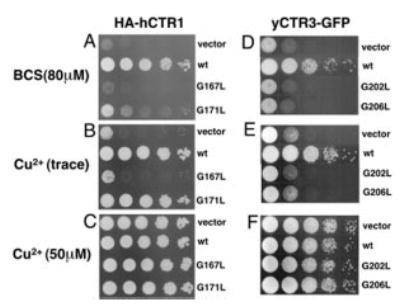

Fig. 1A depicts the human high affinity copper uptake transporter with its extracellular N terminus, three transmembrane domains, and intracellular C terminus. Within TM3, all of the members of the family have a conserved GG4 motif (Fig. 1B). Because this sequence motif is intimately involved in stabilizing helix-helix interactions in other membrane proteins (33–35), we reasoned that the GG4 motif plays a crucial role in the structure and, consequently, the function of the CTR copper uptake transporters. To test this hypothesis, we first disrupted the GG4 motif of tagged hCTR1 and yCTR3 by individually replacing each glycine (hCTR1, Gly167 and Gly171; yCTR3, Gly202 and Gly206) with leucine and then determined whether the mutant proteins were still able to rescue a growth defect of a yeast strain incapable of high affinity copper uptake (Δctr1,3). Fig. 2 demonstrates that the tagged wild type proteins HA-hCTR1 and yCTR3-GFP were able to support the growth of the Δctr1,3 strain, even under copper-depleted conditions using the copper chelator BCS. In contrast, the HA-hCTR1G167L and yCTR3G202L-GFP mutants in which the first glycine in the GG4 motif had been replaced by leucine were not able to complement the growth defect (Fig. 2, panels A and D, respectively). Interestingly, the replacement of the second glycine residue affected the function of the human and yeast proteins in different ways. The yCTR3G206L-GFP mutant was completely non-functional by complementation, whereas a partially functional phenotype was observed in the case for the corresponding HA-hCTR1G171L mutant. The latter mutant grew on trace amounts of copper (neither excess copper nor chelator added, Fig. 2, panel B) but exhibited very poor growth in the presence of BCS. The apparent differences in growth were not attributed to a lack of protein expression, because Western blot analysis and fluorescence microscopy confirmed that each clone expressed its respective CTR mutant (Figs. 3 and 5A). Moreover, the fact that all of the yeast clones grew well in the presence of excessive copper indicated that none of the CTR constructs tested was toxic to the cell (Fig. 2, panels C and F) and that growth of the Δctr1,3 strain on trace amounts of copper or in the presence of BCS was solely dependent on the expression of functional copper transporter at the plasma membrane.

Fig. 1. Topology of human CTR1 and highly conserved Gly-X-X-X-Gly motif.

A, diagram of a human CTR1 monomer shows the extracellular N terminus, three putative transmembrane domains, and an intracellular C terminus. Amino acid positions represented as black circles are invariantly conserved in CTRs from yeast, plants, and metazoans, and those in gray are >90% identical in the family. Two conserved amino acid motifs in the entire family of CTR copper uptake proteins, Met-X-X-X-Met in TM2 and Gly-X-X-X-Gly (GG4) motif in TM3, are indicated. B, multiple amino acid sequence alignment of the third TM domain reveals a nearly invariant conservation of the GG4 motif in all of the known members of the CTR copper uptake family.

Fig. 2. Effect of GG4 mutations on human CTR1 and yeast CTR3 function.

Yeast deficient in high affinity copper uptake (Δctr1,3) were transformed with vector only, HA-tagged wild type human CTR1 (wt), and GG4 mutants HA-hCTR1G167L (G167L) and HA-hCTR1G171L (G171L), wild type yeast CTR3-GFP fusion wt, and the corresponding yeast CTR3 GG4 mutants G202L and G206L. Yeast transformants were grown in minimal dextrose medium before two washes with double distilled water. All of the cultures were then adjusted to A600 = 1.0 and plated in serial 1:10 dilutions on plates containing glycerol as the sole non-fermentable carbon source. A, copper depletion for HA-hCTR1 was acheived with 80 μm copper chelator BCS. B, neither copper nor BCS was added to the plates. C, excess copper (50 μm). D, E, and F, same as A, B, and C, respectively, but with yCTR3-GFP.

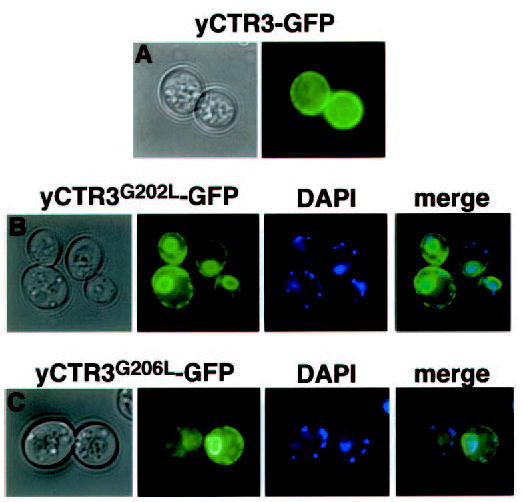

Fig. 3. Fluorescence localization of wild type and GG4 mutants G202L and G206L of yeast CTR3-GFP.

Colonies of yeast transformants of the same constructs used in complementation experiments were spotted directly on glass coverslips for fluorescence microscopy. Bright-field and corresponding fluorescence images are shown. A, plasma membrane localization of wild type yCTR3-GFP fusion protein. GG4 mutants G202L (panel B) and G206L (panel C) are trapped in a perinuclear intracellular compartment as revealed by DAPI staining of nuclear DNA and a ring at the periphery of the cell. Accumulation of GFP-tagged mutant proteins in both regions is indicative of ER localization in yeast. Smaller DAPI-stained points represent mitochondrial DNA.

Fig. 5. Processing of GG4 mutants and induction of the unfolded protein response.

A, yeast cultures expressing the indicated constructs were grown to mid-log phase before protein synthesis was halted with cycloheximide. Samples were removed from the culture at the indicated time points, and total protein extracts were subjected to Western blot using an anti-HA primary antibody. Note that a nearly overexposed blot demonstrates the lack of any higher order glycosylation for the G167L mutant compared with wild type and G171L. The doublet of bands observed for the G167L mutant corresponds to unglycosylated and core-glycosylated species, respectively. Recall in Fig. 4 that complex glycosylation (seen as high molecular mass smearing) as well as core glycosylation (as a distinct band that migrated at ~28 kDa), could be reduced to a single band (~23 kDa) upon exposure to PNGase F. B, yeast transformed with both pSZ1-UPRE-LacZ and an expression plasmid carrying either wild type G167L or G171L were subjected to β-galactosidase assay to determine the extent of induction of the unfolded protein response (n = 3–4 randomly selected colonies/condition).

The GG4 Motif Is Required for CTR Processing and Oligomerization

Because mutation of the first position of the GG4 motif completely blocked growth complementation for both hCTR1 and yCTR3 but did not interfere with their expression, we reasoned that these mutations result in a bona fide structural defect that prevents the proteins from functioning in copper uptake. To test this hypothesis, we exploited that yCTR3-GFP is functional in high affinity copper uptake in yeast (20). This fusion protein was used to determine the localization of both the unmutated copper transporter and G202L and G206L mutants in living yeast cells. Fig. 3 demonstrates that yCTR3-GFP (panel A) but not yCTR3G202L-GFP or yCTR3G206L-GFP (panels B and C, respectively) was localized to the plasma membrane in the Δctr1,3 yeast strain. The yCTR3G202L-GFP and yCTR3G206L-GFP exhibited mislocalization to an intracellular compartment likely to be the endoplasmic reticulum based on the characteristic staining of both a perinuclear ring, revealed by DNA staining with DAPI, as well as a ring at the periphery of the cell. Thus, the failure of yCTR3G202L and yCTR3G206L-GFP to complement growth of a yeast strain deficient in high affinity copper uptake was attributed to a sorting/trafficking defect of these yCTR3 mutants.

Both hCTR1 and yCTR3 have been shown to exist as trimers in the phospholipid membrane (20, 36). Therefore, mislocalization of mutant CTR proteins having a mutated GG4 motif suggested a structural defect that might interfere with proper oligomerization. We tested the hypothesis that hCTR1G167L would not be able to obtain its native trimeric state using the homobifunctional cross-linker, ethylene glycol succinimidylsuccinimate, which has been successfully used to demonstrate a trimeric state for both yCTR3 and hCTR1 (20, 36). Fig. 4 indicates that HA-tagged wild type (panel A) but not HA-hCTR1G167L (panel B) can be efficiently cross-linked to the native trimeric state in detergent-solubilized yeast crude membrane preparations. In all of the cross-linking experiments, the band corresponding to the G167L monomer always gradually disappeared when exposed to increasing concentrations of cross-linker and the bands for the defined oligomeric species were never observed. Experiments performed with partially purified HA-hCTR1G167L using the slightly lower molecular weight cross-linker dithiobis succinimidylpropionate revealed the formation of a very high molecular weight product that failed to migrate into the gel (Fig. 4, panel C). Moreover, the gel filtration of an N-linked glycosylation-deficient double mutant HA-hCTR1N15Q-G167L resulted in a mixture of multiple molecular species that eluted from the column across the entire elution profile (data not shown). Together, these results suggested that the high molecular weight cross-linking product of the G167L mutant reflected an inability of properly folded monomers to form a defined oligomer. Therefore, we concluded that the introduction of the larger side chain of leucine into the first position of the GG4 motif (Gly167) of TM3 of hCTR1 disrupts the formation of functional oligomers.

Fig. 4. Chemical cross-linking of human CTR1 wild type and GG4 mutant G167L.

Membranes prepared from yeast overexpressing HA-tagged human CTR1 wild type (wt) (A) or HA-hCTR1G167L mutant (B) were solubilized with Triton X-100 detergent and subjected to chemical cross-linking. Solubilized material was incubated in increasing concentrations of the ethylene glycol succinimidylsuccinimate (EGS) cross-linker before being subjected to Western blot using an anti-HA primary antibody. HA-tagged wild-type human CTR1 required removal of N-linked glycosylation by treatment with PNGase F prior to exposure to EGS to clearly resolve oligomeric states. Partially purified HA-hCTR1G167L was concentrated before exposure to increasing concentrations of the slightly lower molecular weight cross linker dithiobis succinimidylpropionate (DSP) (panel C). Filled ovals displayed to the right of the images indicate the expected migration positions for monomer, dimer, and trimer species of hCTR1.

Misassembled hCTR1G167L Initiates the Unfolded Protein Response

Western blot analysis revealed a striking difference in the biochemical processing of HA-hCTR1G167L when compared with either HA-wild type or HA-hCTR1G171L mutant. As was seen in Fig. 4A, the larger molecular mass smear due to fully N-glycosylated HA-tagged wild type hCTR1 could be reduced to a single approximate 23-kDa band when treated with the deglycosylating enzyme PNGase F. Fig. 5, panel A, demonstrates that both HA-wild type and HA-hCTR1G171L mutant were fully N-glycosylated but that HA-hCTR1G167L, which was completely non-functional in the complementation assay, fails to undergo complex glycosylation. This failure to undergo Golgi-dependent complex glycosylation was not due to a less efficient processing in the ER, because full glycosylation was never observed for HA-hCTR1G167L, even when samples were analyzed up to 3 h after halting de novo protein synthesis. This behavior is in agreement with the intracellular retention observed independently for the corresponding yCTR3G202L-GFP mutant (Fig. 3) and suggested that the HA-hCTR1G167L and yCTR3G202L-GFP mutants both were misfolded/misassembled in vivo, causing them to fail quality control mechanisms of the cell, presumably in the ER.

The conclusion that mutations in the GG4 motif blocked an ER-dependent processing step in the maturation of CTR proteins was furthermore supported by the finding that only the fully non-functional mutants invoked the yeast UPR. The UPR-assay uses the 22-bp UPRE nucleotide sequence fused to β-galactosidase reporter on plasmid DNA (37, 38). We co-transformed the Δctr1,3 yeast strain with this plasmid and either hCTR1 wild type, G167L, or G171L mutant and then quantified β-galactosidase activity to measure the UPR. Neither the wild type nor G171L mutant of hCTR1 triggered the UPR; however, the G167L mutant initiated nearly a 10-fold induction of the UPR over wild type (Fig. 5, panel B). Similarly, the non-functional GG4-mutants of the yCTR3 (G202L and G206L) both triggered the UPR (data not shown). Thus, the expression of misfolded/misassembled GG4 mutant proteins caused stress to the endoplasmic reticulum sufficient to activate the UPR machinery of the yeast cell. From these results, we concluded that Gly167 of hCTR1 and Gly202/Gly206 of yCTR3 were critical for assembly of functional trimers and maturation of CTR proteins in the ER.

Tryptophan Scanning of TM3 Reveals Two Non-overlapping Helix Faces with Different Roles in CTR Structure

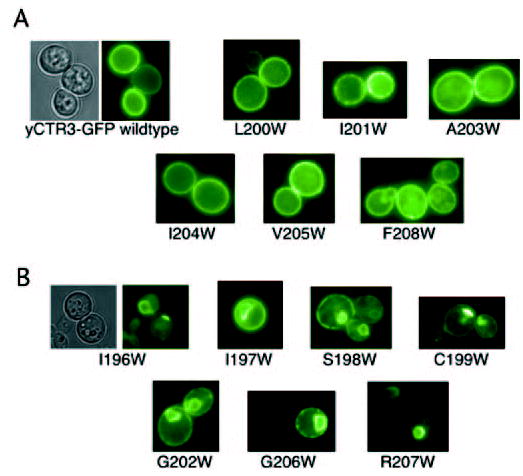

The finding that the GG4 motif contributes to CTR oligomerization raised the question whether additional residues on TM3 were also required for CTR function. To address this question, we subjected approximately two-thirds of TM3 of yCTR3-GFP to tryptophan-scanning mutagenesis. The bulky size of the tryptophan side chain provides a convenient tool to assess whether a particular position along a transmembrane helix is sterically constrained. Fig. 6 shows the results obtained by scanning TM3 of yCTR3-GFP from residues 196 to 208. Six different positions, when mutated to tryptophan, exhibited plasma membrane localization that was identical to wild type (L200W, I201W, A203W, I204W, V205W, and F208W) and were functional in the complementation assay (data not shown). Seven positions (I196W, I197W, S198W, C199W, G202W, G206W, and R207W) had an intracellular localization similar to the GG4 mutant G202L that was trapped in the perinuclear endoplasmic reticulum. Four of these mutants failed to complement yeast growth under copper-limiting conditions. However, three mutants (I196W, I197W, and R207W) partially rescued copper uptake in the Δctr1,3 strain (data not shown) despite being mostly mis-localized. To interpret both the tryptophan-scanning mutagenesis and complementation results, a helical wheel diagram summarizing both sets of data was generated (Fig. 7). All three positions where introduction of tryptophan interfered with efficient processing in the ER but did not completely abolish function based on complementation were located on one face of TM3. Similarly, the four positions where introduction of tryptophan resulted in a non-functional phenotype (neither supporting growth complementation nor permitting localization to the plasma membrane) also clustered on a single but opposite face of TM3.

Fig. 6. Fluorescence localization of tryptophan-scanning mutants of the third transmembrane domain of yeast CTR3-GFP fusion.

Thirteen separate constructs were synthesized by subcloning the wild-type yCTR3 into the p423GPD vector and performing site-directed mutagenesis to replace each amino acid position from 196 to 208 with tryptophan. Mutants were transformed, picked from minimal dextrose selective plates, and subjected to fluorescence microscopy. A, class of six mutants exhibited localization that was identical to wild type. B, second class of mutants revealed abnormal localization to intracellular compartments.

Fig. 7. Helical wheel diagram summarizing the results of tryptophan-scanning mutagenesis and complementation experiments.

A helical wheel was generated for the middle 13 positions of TM3 (amino acid residues 196–208). Gray circles represent amino acid positions where introduction of a tryptophan residue did not interfere with localization to the plasma membrane and function of the mutant protein in the complementation assay. Three dotted circles identify amino acid positions that caused mislocalization when mutated to tryptophan but were partially functional in the complementation assay. Black circles represent positions where introduction of tryptophan resulted in mislocalization and completely abolished function in complementation experiments. Under the helical wheel, the native sequence of yCTR3 is displayed. The same color-coded circles summarizing the fluorescence localization and complementation results obtained for each tryptophan mutant are placed above each amino acid letter.

DISCUSSION

CTR proteins seemingly defy the paradigm in which constraints on protein structure and/or function result in sequence conservation. Specifically, over its length of 190 residues, hCTR1 shares only 14 residues with >80% other CTR proteins. Of these residues, eight are distributed over the ~63 amino acids that make up the three predicted TMs. Thus, even within their most conserved region, sequence conservation is low and, in some cases, falls below the 25% sequence identity cutoff for which two protein structures would be expected to adopt the same overall fold (39–41). How can a conservation of function and oligomerization be reconciled with such low homology at the amino acid sequence level? In part, this question is answered by the specific structure of CTR proteins because in the context of a trimer formed of subunits that themselves are three-helix bundles, a significant number of residues within the membrane-spanning domains are expected to be exposed to phospholipid. Thus, other than being hydrophobic, these lipid-exposed residues need not be strictly conserved to support the formation of functional CTR proteins. However, the fact that oligomerization of CTR proteins is required for function imposes constraints on the structure because oligomerization relies on a defined packing interface between subunits. Notably, two of the few highly conserved residues within CTR proteins form a GG4 motif, a motif that has recently emerged as an important feature of helix-helix interactions in integral membrane proteins (34, 35, 42, 43).

The GG4 motif is overabundant in the amino acid sequences of the membrane-spanning domains of integral membrane proteins (25) and has been shown to mediate homo-oligomerization of the erythrocyte single pass membrane protein glycophorin A (GpA, Protein Data Bank code 1AFO) (33) as well as the polytopic bacterial mechanosensitive channel MscS (Protein Data Bank code 1MXM) (26) and yeast β-factor G-protein coupled receptor Ste2p (43). Moreover, in the mechanosensitive channel MscL, a derivative of the GG4 motif, AVXXG, is at the heart of subunit-subunit contacts that allow the five inner helices of MscL to pack closely enough for the valine to close off the pore in the closed state of the channel (Protein Data Bank code 1MSL) (27). However, the contributions of the GG4 motif to membrane protein folding and oligomerization are multi-faceted. This is evident from the high resolution crystal structures of the polytopic bacterial glycerol facilitator, GlpF (Protein Data Bank code 1FX8) (28), and the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump (Protein Data Bank code 1SU4) (44). In both cases, the GG4 motif is not involved in monomer-monomer contacts to drive oligomerization but instead stabilizes the protein fold within monomers, which then assemble into tetramers (for GlpF) and dimers (for Ca2+ pump) through interfaces that do not contain GG4 motifs. The presence of such a motif in the third transmembrane domain of the CTR family strongly suggested an important role in structural stability for this family of copper uptake proteins. However, because of its dual-natured role in individual examples in molecular biology, it was not predictable how the GG4 motif contributes to structure and function in the CTR family of membrane proteins.

To clarify the role of the GG4 motif in the CTR family of membrane proteins, we carried out a mutational analysis of the GG4 motif in two distantly related CTR proteins, hCTR1 and yCTR3 (<20% sequence identity overall, ~30% sequence identity in the membrane-embedded region), and investigated the importance of non-conserved residues in TM3 of yCTR3 for function. Our main findings were as follows. Firstly, the GG4 motif is essential for the formation of fully functional trimers yet displays some plasticity since hCTR1 but not yCTR3 tolerated a leucine substitution in the second position of the GG4 motif. Secondly, steric constraints extend beyond the GG4 motif itself, including amino acids Ser198 and Cys199 of yCTR3 (Fig. 7) that are not conserved among different CTR proteins. The existence of these additional steric constraints along the same helix face suggested that the contribution of the GG4 motif to CTR oligomerization or folding was subject to long range fine-tuning, as has been observed in other cases (45), and may explain why CTR4 and CTR5 from the yeast S. pombe cannot form functional trimers independently of each other (14). In the S. pombe CTR4, the residues corresponding to the essential positions of yCTR3Ser-188 and yCTR3Cys-189 are Phe236 and Leu237. The large size of these side chains may be detrimental to formation of a homo-trimer and may be intrinsically rescued by forming a hetero-oligomer with S. pombe CTR5 in which the equivalent residues are Phe143 and Gly144. Thirdly, TM3 is involved in contacts with at least two other α-helices in the final structure of CTRs, because tryptophan scanning revealed a second helical face containing mutants that were partially functional yet displayed various degrees of trafficking defects (Fig. 6). These mutants (I196W, I197W, and R207W) cluster on the face of TM3 that is opposite to the GG4-bearing face (Fig. 7). The clear spatial segregation among mutants that completely abolished function and those that did not suggests that the two faces of TM3 serve different roles in the formation of functional CTR proteins. Of the two faces, the GG4-containing face of TM3 clearly serves a more important role for the assembly of mature CTR and it is tempting to hypothesize that this face is involved in intersubunit contacts in the final structure of the copper transporter.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Dennis Thiele, Dr. Jane Gitschier, and Dr. Mark Hochstrasser for providing yeast strains and plasmids used in this study. We thank Dr. Peter Takizawa and Brian Dunn for help with fluorescence microscopy and Thomas Yae for technical assistance. We also thank members of the Unger laboratory for excellent discussions and critical review of the paper.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by NRSA Predoctoral Fellowship F32 NS45550 (to S. G. A.), a Hellman Family Fellowship, and Public Health Service Grants GM66145 and DA017088 (to V. M. U.).

The abbreviations used are: CTR, copper uptake transporter; TM, transmembrane; GG4, Gly-X-X-X-Gly; hCTR, human CTR; yCTR, yeast CTR; HA, hemagglutinin; GFP, green fluorescent protein; MD, minimal dextrose; BCS, bathocuproinedisulfonic acid; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; UPR, unfolded protein response; UPRE, UPR element; PNGase F, protein N-glycosidase F.

References

- 1.Linder, M. C. (1991) Biochemistry of Copper, Plenum Press, New York

- 2.Pena MM, Lee J, Thiele DJ. J Nutr. 1999;129:1251–1260. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.7.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiDonato M, Sarkar B. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1360:3–16. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(96)00064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaefer M, Gitlin JD. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G311–G314. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.2.G311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strausak D, Mercer JF, Dieter HH, Stremmel W, Multhaup G. Brain Res Bull. 2001;55:175–185. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00454-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovell MA, Robertson JD, Teesdale WJ, Campbell JL, Markesbery WR. J Neurol Sci. 1998;158:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin K, Yang DS, Yang Y, Chishti MA, Meng LJ, Kretzschmar HA, Yip CM, Fraser PE, Westaway D. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19121–19131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.25.19121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zanusso G, Farinazzo A, Fiorini M, Gelati M, Castagna A, Righetti PG, Rizzuto N, Monaco S. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40377–40380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100458200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dancis A, Yuan DS, Haile D, Askwith C, Eide D, Moehle C, Kaplan J, Klausner RD. Cell. 1994;76:393–402. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90345-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dancis A, Haile D, Yuan DS, Klausner RD. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25660–25667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kampfenkel K, Kushnir S, Babiychuk E, Inze D, Van Montagu M. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28479–28486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.47.28479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou B, Gitschier J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7481–7486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marvin ME, Williams PH, Cashmore AM. Microbiology. 2003;149:1461–1474. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou H, Thiele DJ. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20529–20535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou H, Cadigan KM, Thiele DJ. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48210–48218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309820200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riggio M, Lee J, Scudiero R, Parisi E, Thiele DJ, Filosa S. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1576:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00337-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J, Prohaska JR, Dagenais SL, Glover TW, Thiele DJ. Gene (Amst) 2000;254:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishida S, Lee J, Thiele DJ, Herskowitz I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14298–14302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162491399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin X, Okuda T, Holzer A, Howell SB. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:1154–1159. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.5.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pena MM, Puig S, Thiele DJ. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33244–33251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005392200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisses JF, Kaplan JH. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29162–29171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puig S, Lee J, Lau M, Thiele DJ. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26021–26030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klomp AE, Juijn JA, van der Gun LT, van den Berg IE, Berger R, Klomp LW. Biochem J. 2003;370:881–889. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo Y, Smith K, Lee J, Thiele DJ, Petris MJ. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17428–17433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401493200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Senes A, Gerstein M, Engelman DM. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:921–936. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bass RB, Strop P, Barclay M, Rees DC. Science. 2002;298:1582–1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1077945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang G, Spencer RH, Lee AT, Barclay MT, Rees DC. Science. 1998;282:2220–2226. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu D, Libson A, Miercke LJ, Weitzman C, Nollert P, Krucinski J, Stroud RM. Science. 2000;290:481–486. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5491.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleiger G, Grothe R, Mallick P, Eisenberg D. Biochemistry. 2002;41:5990–5997. doi: 10.1021/bi0200763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, Nijbroek G, Sullivan ML, McCracken AA, Watkins SC, Michaelis S, Brodsky JL. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1303–1314. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.5.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider D, Engelman DM. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3105–3111. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206287200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller, J. H. (1992) A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

- 33.MacKenzie KR, Prestegard JH, Engelman DM. Science. 1997;276:131–133. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russ WP, Engelman DM. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:911–919. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senes A, Ubarretxena-Belandia I, Engelman DM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9056–9061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161280798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee J, Pena MM, Nose Y, Thiele DJ. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4380–4387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedlander R, Jarosch E, Urban J, Volkwein C, Sommer T. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:379–384. doi: 10.1038/35017001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mori K, Sant A, Kohno K, Normington K, Gething MJ, Sambrook JF. EMBO J. 1992;11:2583–2593. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brenner SE, Chothia C, Hubbard TJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6073–6078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rost B. Protein Eng. 1999;12:85–94. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson CA, Kreychman J, Gerstein M. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:233–249. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee SF, Shah S, Yu C, Wigley WC, Li H, Lim M, Pedersen K, Han W, Thomas P, Lundkvist J, Hao YH, Yu G. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4144–4152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309745200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Overton MC, Chinault SL, Blumer KJ. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49369–49377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308654200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toyoshima C, Nakasako M, Nomura H, Ogawa H. Nature. 2000;405:647–655. doi: 10.1038/35015017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Melnyk RA, Kim S, Curran AR, Engelman DM, Bowie JU, Deber CM. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16591–16597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313936200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]