Abstract

We examined the effect of mutation of two sortase genes of Bacillus anthracis, srtA and srtB, on the ability of the bacterium to grow in J774A.1 cells, a mouse macrophage-like cell line. While disruption of either srtA or srtB had no effect on the ability of the bacteria to grow in rich culture media, mutations in each of these genes dramatically attenuated growth of the bacterium in J774A.1 cells. Complementation of the mutation restored the ability of bacteria to grow in the cells. Since the initial events in inhalation anthrax are believed to be uptake of B. anthracis spores by alveolar macrophages followed by germination of the spores and growth of the bacteria within the macrophages, these results suggest that two sortases of B. anthracis may be critical in the early stages of inhalation anthrax.

Bacillus anthracis is a spore-forming, gram-positive, soil-borne organism that causes disease in both animals and humans. Human disease presents in three forms: cutaneous, gastrointestinal, and inhalational anthrax (7). Unless antibiotics are administered early, inhalational anthrax is associated with a high mortality rate (8). The inhalational form of anthrax has become a major concern because of the potential for B. anthracis to be used in the aerosolized form as a bioweapon.

During the very early stages of inhalation anthrax, alveolar macrophages engulf inhaled spores and transport them to the regional lymph nodes. The spores germinate within the macrophages followed by growth of the vegetative bacilli and their release into circulation, where they are capable of replicating to a density of 108 CFU/ml (10, 11). While factors encoded on the two virulence plasmids of B. anthracis, pXO1 and pXO2, clearly play important roles in pathogenesis (9, 13, 15, 19-21, 28), chromosomally encoded factors are also likely to be critical in disease progression. A more complete understanding of the virulence factors of B. anthracis is required in order to expedite development of novel therapeutics and vaccines.

Since surface proteins of bacteria often play important roles in virulence, we hypothesized that such proteins may also play a role in the pathogenesis of B. anthracis. One group of surface proteins that is commonly found in gram-positive bacteria consists of proteins that are attached to the peptidoglycan by a family of proteins known as sortases (22). Such surface proteins contain an N-terminal signal peptide and a C-terminal sorting signal that contains the motif LPXTG (or a slight variation thereof) that is recognized by the sortase. Sortases are transpeptidases that are anchored in the membrane of the bacteria via an N-terminal hydrophobic leader peptide (22). They cleave the substrate protein after the threonine residue of the LPXTG motif and, through a nucleophilic attack of the amino group of the lipid II peptidoglycan precursor, link the protein to the cell wall (24, 27). Loss of sortase activity results in improper localization of the LPXTG-containing surface proteins with resulting loss of function and can lead to an attenuation of virulence (16).

B. anthracis has three putative sortase genes (23, 26). Two of these, BA0688 and BA4783 (26), are named srtA and srtB, respectively, based on their homology to the srtA and srtB genes of Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria monocytogenes (1, 30). The protein encoded by srtA contains the characteristic N-terminal transmembrane region and C-terminal catalytic TLXTC motif that is conserved in all sortase family member proteins. The three-dimensional structure of B. anthracis SrtB has been determined at 1.6-Å resolution and was shown to be very similar to that of S. aureus SrtB (30). A putative active site comprising a Cys-His-Asp catalytic triad has been identified in B. anthracis SrtB and shown to have a spatial arrangement similar to that of the S. aureus SrtB (30). Examination of the B. anthracis genome reveals a number of putative sortase substrates as determined by the presence of an LPXTG motif at the C-terminal end of the predicted protein (26).

In inhalational anthrax, alveolar macrophages are believed to be the primary site for germination of B. anthracis spores (10). The ability of the bacteria to survive and grow within and to escape from this environment is thought to be critical for the disease to proceed. In this study, we examined the effect of mutations of the srtA and srtB genes on the ability of B. anthracis to grow in cultures of J774A.1 cells, a mouse macrophage-like cell line, as a first step in identifying factors that may play an important role in the early stages of disease. We constructed the srt mutations in B. anthracis Sterne 7702 (all strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1). While the Sterne strain of B. anthracis lacks pXO2, one of the two plasmids found in fully virulent strains of B. anthracis, it nonetheless survives and replicates in macrophages (4, 25). Others have shown that escape of the Sterne strain from macrophages is indistinguishable from that of a B. anthracis strain containing both pXO1 and pXO2 (4).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid or strain | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli DH5α | F−ϕ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) phoA supE44λ−thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Invitrogen |

| B. anthracis | ||

| Sterne 7702 | pXO1+, pXO2− toxigenic, unencapsulated | 2 |

| 9131 | pXO1−, pXO2− nontoxigenic, unencapsulated | 5 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1-TOPO | ColE1 ori, Apr, Kmr, lacZα | Invitrogen |

| pHY304 | Emr temperature-sensitive pVE6007Δ derivative, lacZα multiple cloning site of pBluescript | 12 |

| pUTE29 | Apr in E. coli, Tcr in B. anthracis | 14 |

| pHYZ2 | pHY304 that contains an srtA internal fragment lacking both the 5′ and 3′ ends of the gene | This study |

| pHYZ3 | pHY304 that contains a srtB internal fragment lacking both the 5′ and 3′ ends of the gene | This study |

| pEZ31 | pUTE29 that contains the srtA region | This study |

| pEZ34 | pUTE29 that contains the srtB region | This study |

The regions of the B. anthracis chromosome containing srtA (BA0688) and srtB (BA4783) are depicted in Fig. 1. Insertional mutagenesis of the genes was accomplished as follows. PCR products were synthesized using oligonucleotides 1 and 2 for amplification of a portion of the srtA gene and 3 and 4 for amplification of a portion of the srtB gene (all primers used in this study are listed in Table 2). The PCR products were designed to remove the 5′ portion of the gene encoding the signal sequence needed for the insertion of the sortase protein into the membrane and the 3′ portion of the gene encoding amino acid residues predicted to be located in the enzymatic site. The PCR fragments were cloned into the temperature-sensitive vector pHY304 to create pHYZ2 and pHYZ3. The pHY304 vector replicates autonomously at 30°C but not at 37°C. The plasmids were introduced into B. anthracis by electroporation (14). The resultant transformants were selected on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar containing erythromycin at 30°C. Bacteria were then passaged at the nonpermissive temperature (37°C). Single colonies were isolated, and those that grew on BHI agar containing erythromycin (10 μg/ml) were examined by PCR analysis to verify that the plasmid had integrated into the srt gene on the chromosome. Integration of the plasmid into the chromosome by homologous recombination results in the formation of two incomplete copies of the srt gene, each of which would be predicted to encode a nonfunctional protein (Fig. 1). Complementing plasmids were also constructed and introduced into the appropriate mutant strains. Complementation of the srtA mutation was accomplished as follows. The srtA gene plus 776 base pairs upstream of srtA encompassing two putative open reading frames and a potential promoter sequence (Fig. 1) was amplified by PCR using primers 5 and 6. The resulting 1,573-bp product was inserted into pUTE29, a plasmid capable of autonomously replicating in B. anthracis, to create pEZ31. pEZ31 was introduced into B. anthracis Sterne 7702::pHYZ2 by electroporation. Complementation of the srtB mutation was accomplished as follows. PCR fragments were amplified using primers 7 and 8 (to obtain the putative promoter region) and primers 9 and 10 (to obtain the srtB gene) (Fig. 1). The former fragment was cloned into PCR2.1-TOPO, creating pEZ32. pEZ32 and the latter fragment were digested with SacI and XmaI and ligated to form pEZ33, which contains the putative promoter, an in-frame fusion of BA4789 and BA4784, and srtB. The HindIII-SacI fragment of pEZ33 was inserted into pUTE29 to generate pEZ34. pEZ34 was introduced into B. anthracis Sterne 7702::pHYZ3 by electroporation. As indicated, some upstream sequence was included in the complementing clones for both srtA and srtB to ensure that a functional promoter was included; however, it should be noted that the methodology used to create the srtA and srtB mutations would not be expected to affect expression of upstream genes.

FIG. 1.

Insertional mutagenesis of srtA and srtB. The regions of the B. anthracis genome encompassing the srtA (A) and srtB (B) genes are shown. Gene designations are from Read et al. (26). While srtA (BA0688) is located in a region of the chromosome devoid of genes encoding putative LPXTG-containing substrates, srtB (BA4783) is located approximately 6 kb from BA4789, which encodes a potential substrate (see the text). Insertional mutagenesis of the srt genes was accomplished as diagrammed. A portion of the srt gene (gray-shaded box) lacking critical regions at both the 5′ and 3′ ends was inserted into a temperature-sensitive plasmid. At the nonpermissive temperature, plasmid-encoded drug resistance is maintained only if the plasmid recombines with the chromosome. Homologous recombination results in the formation of two incomplete copies of the srt gene, each of which is predicted to encode a nonfunctional protein (see the text). Asterisks indicate the positions of the primers used to generate PCR fragments used in the complementing plasmids (see the text for details).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this studya

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| 1 | 5′-GGCGCAAGCTTGATGGATATCAAGCTGAAAAG-3′ |

| 2 | 5′-GGCGCGGATCCTGATTTCATCTTTCCCATGA-3′ |

| 3 | 5′-GGCGCAAGCTTTGATCACCTGCTGTTACTGTTG-3′ |

| 4 | 5′-GGCGCGGATCCCGTAAAGTAATGGCCGAAGC-3′ |

| 5 | 5′-GGCGGAAGCTTGTAAAGTTGGATTTTTTTGTGAAAATA-3′ |

| 6 | 5′-GGCGGTCTAGAAAAGATGAGGGATTTCCC-3′ |

| 7 | 5′-GGCGGAAGCTTAGAAAAGAGGCTTTCTATAATAGA-3′ |

| 8 | 5′-GGCGGCCCGGGTATCTGACGATTCATCTTTACTA-3′ |

| 9 | 5′-GGCGGGAGCTCTATAGAATAGGAGAAACGTTACCAC-3′ |

| 10 | 5′-GGCGCCCGGGTCTTTTTAGATGAACCGACA-3′ |

The underlined bases are restriction sites added to the sequence to facilitate cloning. Primers were designed using the genome sequence of the B. anthracis Ames strain (Genbank accession no. AE016879).

To determine if a defect in either of the srt genes has an effect on the growth rate of B. anthracis Sterne 7702 in vitro, we compared the growth of the srtA and srtB mutant strains in BHI broth with that of the parental strain. Spores were prepared essentially as described previously (6) and were enumerated visually using a hemacytometer. Equal numbers of spores were used to inoculate BHI broth (50 ml). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in a shaking incubator set at 250 rpm, and aliquots were taken hourly for 9 h. Growth of the bacteria was measured by determining the absorbance of the cultures at 600 nm. No significant difference in the growth rate of either the srtA or srtB mutant strain as compared to the parental strain in BHI broth was observed (data not shown). Throughout the growth of the mutant strains, erythromycin resistance was maintained (data not shown), indicating no detectable loss of the integrated plasmids that disrupted the srtA and srtB genes. Thus, disruption of neither srtA nor srtB affects growth in vitro.

We next examined whether the mutant strains were impaired in their ability to grow in macrophages. In this assay, J774A.1 cells (ATCC TIB-67) were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 overnight. On the day of the experiment, bacterial spores were diluted in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco BRL, Rockville, Md.) supplemented with 10% horse serum (Biosource, Gaithersburg, Md.) and added to triplicate wells containing the J774A.1 monolayers at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. After 1 h at 37°C, the wells were washed three times with prewarmed cell culture medium and then incubated at 37°C with cell culture medium containing gentamicin (10 μg/ml) for an additional 30 min. The monolayer was then washed three times with cell culture medium containing 10% horse serum. The infection was carried out in DMEM supplemented with 10% horse serum to reduce germination of extracellular spores. We have found that the spores do not germinate in this medium over the time course of our experiments (data not shown). At the indicated times extracellular bacteria were enumerated by removing the cell culture medium from the wells, serially diluting (10-fold dilutions) it in a volume of 200 μl, and plating the dilutions on BHI agar and BHI agar containing antibiotics when appropriate. The CFU were determined at each dilution, and CFU per milliliter were then calculated. CFU were determined in the presence and absence of appropriate antibiotics to verify the stability of the constructs over the time course of the experiment. Intracellular bacteria were enumerated as follows. Sterile distilled water (200 μl) was added to the monolayers after the removal of the extracellular media as described above followed by incubation at room temperature for 10 min. The cell monolayers were then observed microscopically to assure complete lysis. The resultant suspension was serially diluted and counted as described above for the extracellular bacteria. The zero time point was taken immediately following the removal of the gentamicin.

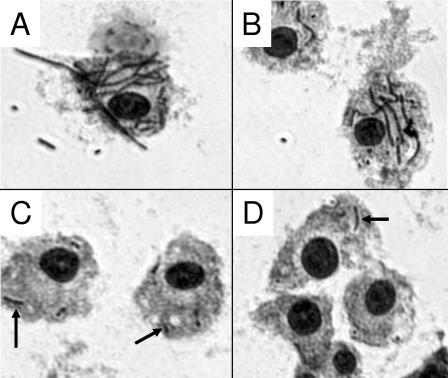

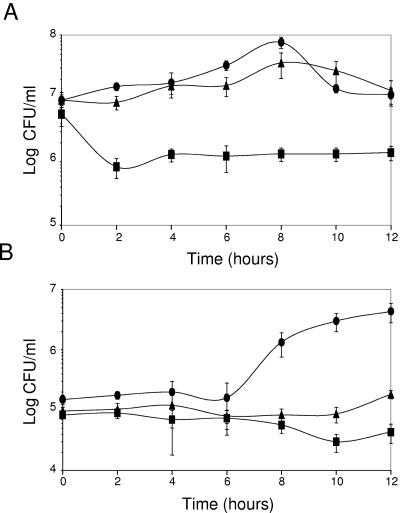

When we examined the ability of the srtA mutant strain to grow in J774A.1 cells using this assay, we obtained the results shown in Fig. 2. The parental strain, B. anthracis Sterne 7702, increased in number intracellularly until 8 h, after which an abrupt decrease in intracellular numbers was observed. This decrease was accompanied by a corresponding increase in extracellular bacteria. The srtA mutant, Sterne 7702::pHYZ2(pUTE29), unlike the parental strain, did not appear to replicate intracellularly over the course of the experiment. Also, no significant increase in extracellular numbers was observed for the srtA mutant strain. Complementation of the srtA mutant with a plasmid containing the srtA region restored intracellular growth to near the levels observed with the parental strain. These results indicate that srtA is essential for growth of B. anthracis within macrophages. Microscopic analysis of the J774A.1 cells during the course of infection further illustrates the striking difference between growth of the parental and mutant strains. As shown in Fig. 3, significant numbers of B. anthracis Sterne bacteria were associated with the macrophages 8 h after initiation of infection; however, very few of the srtA mutant bacteria were observed. The phenotype of the srtA mutant is contrasted with that of B. anthracis 9131, a strain lacking both pXO1 and pXO2. As seen in Fig. 3, a considerable number of B. anthracis 9131 bacteria were associated with the J774A.1 cells 8 h after infection as compared to the srtA mutant.

FIG. 2.

Growth of B. anthracis Sterne 7702 and srtA mutant strains in J774A.1 cells. J774A.1 cells (7.5 × 105 cells/well) were infected at an MOI of 1 with either B. anthracis Sterne 7702 (•), the srtA mutant strain B. anthracis Sterne 7702::pHYZ2(pUTE29) (▪), or the srtA mutant strain complemented with the srtA gene, B. anthracis Sterne 7702::pHYZ2(pEZ31) (▴). At each time point, the number of intracellular (A) and extracellular (B) bacteria were determined as described in the text. Data points and error bars represent mean CFU of the triplicate samples ± standard deviation. The experiment was performed three times, and the results shown are representative of those obtained in each experiment.

FIG. 3.

Micrographs of J774A.1 cells infected with B. anthracis strains. J774A.1 cells were infected at an MOI of 1 with the indicated strains of B. anthracis. After 8 h, the cells were washed, stained with Giemsa, and photographed using an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope. The panels show representative fields (400× magnification) for B. anthracis Sterne 7702 (A), B. anthracis 9131 (a strain lacking both pXO1 and pXO2) (B), the srtA mutant strain B. anthracis Sterne 7702::pHYZ2 (C), and the srtB mutant strain B. anthracis Sterne 7702::pHYZ3 (D). In panels A and B, heavily stained bacteria are readily apparent. In panels C and D, bacteria (some indicated by arrows) are fewer in number.

We next examined whether mutations in srtB of B. anthracis might affect survival or growth of the organism in macrophages. We infected J774A.1 cells with spores of B. anthracis Sterne 7702 and the srtB mutant strain Sterne 7702::pHYZ3(pUTE29). We determined both intracellular and extracellular bacterial counts over the course of a 12-h infection as described above (Fig. 4). The srtB mutant strain exhibited a decreased ability to grow intracellularly as compared to the parental strain. Complementation of the mutant strain with the srtB region restored the ability of the mutant strain to grow within the macrophages to a level near that of B. anthracis Sterne 7702. These results suggest that the SrtB protein is essential for the ability of B. anthracis to grow in J774A.1 cells. Microscopic analysis of the infection of J774A.1 cells with the B. anthracis strains is shown in Fig. 3. As seen in the figure, fewer srtB mutant bacteria were found associated with the macrophages 8 h after the initiation of infection as compared to either the parental B. anthracis Sterne strain or B. anthracis 9131.

FIG. 4.

Growth of B. anthracis Sterne 7702 and srtB mutant strains in J774A.1 cells. J774A.1 cells (1 × 106 cells/well) were infected at an MOI of 1 with either B. anthracis Sterne 7702 (•), or the srtB mutant strain B. anthracis Sterne 7702::pHYZ3 (pUTE29) (▪), or the srtB mutant strain complemented with the srtB gene, B. anthracis Sterne 7702::pHYZ3 (pEZ34) (▴). At each time point, the number of intracellular (A) and extracellular (B) bacteria was determined as described in the text. Data points and error bars represent mean CFU of the triplicate samples ± standard deviation. The experiment was performed three times, and the results shown are representative of those obtained in each experiment.

Our results indicate that disruption of either the srtA or srtB gene results in an inability of the bacteria to grow in J774A.1 cells, since the mutant bacteria do not increase in number during the course of the infection. The microscopic appearance of the mutant spores did not differ from that of the parental spores (data not shown), nor did the defect appear to affect uptake of mutant spores, since the number of mutant bacteria present at the initial time point did not differ significantly from that of the parental Sterne strain or from that of the strain complemented with the appropriate srt gene (Fig. 2 and 4). Moreover, the defect does not appear to be a general germination defect, since mutant spores germinate as well as parental Sterne spores in BHI medium (data not shown), although we cannot discount the possibility that the mutant spores have a germination defect that is specific to the intracellular environment of the macrophage.

The srtA genes of a number of gram-positive bacteria have been shown to be necessary for proper localization of multiple LPXTG-containing proteins (22). Incorrect localization and presentation of these proteins due to mutations in the srtA gene can attenuate the virulence of the bacteria. For example, disruption of srtA of S. aureus diminished the ability of the bacteria to cause acute infection in mice (16). Mutation of the srtA gene of L. monocytogenes impaired the ability of the bacteria to colonize the liver and spleen of mice (1). Our results suggest that SrtA of B. anthracis is likely involved in the correct localization of one or more proteins essential for intracellular growth of the bacteria, an early step in the infectious process. The genome sequence of B. anthracis reveals multiple potential SrtA substrates (26) containing the LPXTG motif characteristic of SrtA substrates in other gram-positive bacteria. Two such B. anthracis LPXTG-containing proteins have been recently studied and were shown to be capable of binding collagen (29). We do not know whether these two proteins might contribute in any way to the phenotype that we observed with our srtA mutant strains.

SrtB proteins of gram-positive bacteria also anchor critical proteins to the bacterial cell surface. SrtB of S. aureus is the most extensively characterized protein belonging to this class of sortase (17, 18, 30). The srtB of S. aureus is found within a region of the genome encoding proteins important for iron acquisition. SrtB of S. aureus tethers IsdC, a protein involved in iron transport, to the cell wall via its NPQTN sequence (18). Mutational analysis of the srtB gene of S. aureus reveals that it is important for persistence of infections in mice (18). The srtB of B. anthracis is located just downstream from BA4789, which is predicted to encode a protein exhibiting considerable homology with IsdC of S. aureus (26). The amino acid sequence of this protein contains an NPKTG sequence that is a potential target for SrtB. Three other genes in this region, BA4784 to BA4786, are predicted to encode proteins that share homology with iron compound ABC transporters (26). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that the SrtB of B. anthracis might be necessary for proper localization of a protein involved in iron acquisition. Cendrowski et al. recently demonstrated that disruption of a gene encoding a protein necessary for siderophore biosynthesis resulted in attenuation of the growth of B. anthracis within macrophages (3), illustrating that iron acquisition systems can be critical during the intracellular stage of this disease.

In this study, we found that mutations in the srtA and srtB genes of B. anthracis result in dramatic attenuation of the growth of the organisms within J774A.1 cells. This phenotype is in contrast to the phenotypes observed with certain other genetic lesions of B. anthracis that have previously been reported. In particular, loss of the pXO1 plasmid which encodes a number of proteins, including the anthrax toxin proteins, resulted in an altered phenotype in macrophages; however, in this case, the bacteria are able to grow and replicate within the macrophage, but they do not readily escape from the cell into the culture medium as seen in Fig. 3 and as described previously (4, 25).

B. anthracis is perhaps the most feared of all potential bacterial bioweapons. The disease, if diagnosed early, can be controlled by a number of antibiotics. However, because of the possibility of the release of genetically engineered strains of the organism which have altered antibiotic sensitivity, identification of other potential drug targets is a high priority. Others have suggested that sortases may be potentially good targets for therapeutic intervention (30). Our work underscores and adds support to that idea, since defects in two of the srt genes of B. anthracis result in dramatic attenuation of the growth of the organism in macrophages, a step that is thought to be critical in the infectious process.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Rubens for generously providing the pHY304 plasmid and A. Pomerantsev for helpful discussions.

Editor: J. D. Clements

REFERENCES

- 1.Bierne, H., S. K. Mazmanian, M. Trost, M. G. Pucciarelli, G. Liu, P. Dehoux, L. Jansch, F. Garcia-del Portillo, O. Schneewind, and P. Cossart. 2002. Inactivation of the srtA gene in Listeria monocytogenes inhibits anchoring of surface proteins and affects virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 43:869-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cataldi, A., E. Labruyere, and M. Mock. 1990. Construction and characterization of a protective antigen-deficient Bacillus anthracis strain. Mol. Microbiol. 4:1111-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cendrowski, S., W. MacArthur, and P. C. Hanna. 2004. Bacillus anthracis requires siderophore biosynthesis for growth in macrophages and mouse virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 51:407-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon, T. C., A. A. Fadl, T. M. Koehler, J. A. Swanson, and P. C. Hanna. 2000. Early Bacillus anthracis-macrophage interactions: intracellular survival and escape. Cell. Microbiol. 2:453-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Etienne-Toumelin, I., J. C. Sirard, E. Duflot, M. Mock, and A. Fouet. 1995. Characterization of the Bacillus anthracis S-layer: cloning and sequencing of the structural gene. J. Bacteriol. 177:614-620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finlay, W. J. J., N. A. logan, and A. D. Sutherland. 2002. Bacillus cereus emetic toxin production in cooked rice. Food Microbiol. 19:431-439. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedlander, A. M. 1999. Clinical aspects, diagnosis and treatment of anthrax. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedlander, A. M., S. L. Welkos, M. L. Pitt, J. W. Ezzell, P. L. Worsham, K. J. Rose, B. E. Ivins, J. R. Lowe, G. B. Howe, P. Mikesell, and W. B. Lawrence. 1993. Postexposure prophylaxis against experimental inhalation anthrax. J. Infect. Dis. 167:1239-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green, B. D., L. Battisti, T. M. Koehler, C. B. Thorne, and B. E. Ivins. 1985. Demonstration of a capsule plasmid in Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 49:291-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guidi-Rontani, C., M. Weber-Levy, E. Labruyere, and M. Mock. 1999. Germination of Bacillus anthracis spores within alveolar macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 31:9-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanna, P. C. 1998. Anthrax pathogenesis and host response. Curr. Topics Microbiol. Immunol. 225:13-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones, A. L., R. H. V. Needham, and C. E. Rubens. 2003. The delta subunit of RNA polymerase is required for virulence of Streptococcus agalactiae. Infect. Immun. 71:4011-4017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein, F., D. R. Hodges, B. G. Mahlandt, W. I. Jones, B. W. Haines, and R. E. Lincoln. 1962. Anthrax toxin: causative agent in the death of rhesus monkeys. Science 138:1331-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koehler, T. M., Z. Dai, and M. Kaufman-Yarbray. 1994. Regulation of the Bacillus anthracis protective antigen gene: CO2 and a trans-acting element activate transcription from one of two promoters. J. Bacteriol. 176:586-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makino, S., I. Uchida, N. Terakado, C. Sasakawa, and M. Yoshikawa. 1989. Molecular characterization and protein analysis of the cap region which is essential for encapsulation in Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 171:722-730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazmanian, S. K., G. Liu, E. R. Jensen, E. Lenoy, and O. Schneewind. 2000. Staphylococcus aureus sortase mutants defective in the display of surface proteins and in the pathogenesis of animal infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:5510-5515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazmanian, S. K., E. P. Skaar, A. H. Gaspar, M. Humayun, P. Gornicki, J. Jelenska, A. Joachmiak, D. M. Missiakas, and O. Schneewind. 2003. Passage of heme-iron across the envelope of Staphylococcus aureus. Science 299:906-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazmanian, S. K., H. Ton-That, K. Su, and O. Schneewind. 2002. An iron-regulated sortase anchors a class of surface protein during Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:2293-2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moayeri, M., and S. H. Leppla. 2004. The roles of anthrax toxin in pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7:19-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mock, M., and T. Mignot. 2003. Anthrax toxins and the host: a story of intimacy. Cell. Microbiol. 5:15-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mourez, M., D. B. Lacy, K. Cunningham, R. Legmann, B. R. Sellman, J. Modridge, and R. J. Collier. 2002. 2001: A year of major advances in anthrax toxin research. Trends Microbiol. 10:287-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navarre, W. W., and O. Schneewind. 1999. Surface proteins of gram-positive bacteria and mechanisms of their targeting to the cell wall envelope. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:174-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pallen, M. J., A. C. Lam, M. Antonio, and K. Dunbar. 2001. An embarrassment of sortases - a richness of substrates? Trends Microbiol. 9:97-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perry, A. M., H. Ton-That, S. K. Mazmanian, and O. Schneewind. 2002. Anchoring of surface proteins to the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. III. Lipid II is an in vivo peptidoglycan substrate for sortase-catalyzed surface protein anchoring. J. Biol. Chem. 277:16241-16248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pickering, A. K., and T. J. Merkel. 2004. Macrophages release tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-12 in response to intracellular Bacillus anthracis spores. Infect. Immun. 72:3069-3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Read, T. D., S. N. Peterson, N. Tourasse, L. W. Baillie, I. T. Paulsen, K. E. Nelson, H. Tettelin, D. E. Fouts, J. A. Eisen, S. R. Gill, E. K. Holtzapple, O. A. Okstad, E. Helgason, J. Rilstone, M. Wu, J. F. Kolonay, M. J. Beanan, R. J. Dodson, L. M. Brinkac, M. Gwinn, R. T. DeBoy, R. Madpu, S. C. Daugherty, A. S. Durkin, D. H. Haft, W. C. Nelson, J. D. Peterson, M. Pop, H. M. Khouri, D. Radune, J. L. Benton, Y. Mahamoud, L. Jiang, I. R. Hance, J. F. Weidman, K. J. Berry, R. D. Plaut, A. M. Wolf, K. L. Watkins, W. C. Nierman, A. Hazen, R. Cline, C. Redmond, J. E. Thwaite, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, B. Thomason, A. M. Friedlander, T. M. Koehler, P. C. Hanna, A. B. Kolsto, and C. M. Fraser. 2003. The genome sequence of Bacillus anthracis Ames and comparison to closely related bacteria. Nature 423:81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ton-That, H., G. Liu, S. K. Mazmanian, K. F. Faull, and O. Schneewind. 1999. Purification and characterization of sortase, the transpeptidase that cleaves surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus at the LPXTG motif. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12424-12429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welkos, S. L. 1991. Plasmid-associated virulence factors of non-toxigenic (pX01-) Bacillus anthracis. Microb. Pathog. 10:183-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu, Y., L. Xiaowen, Y. Chen, T. M. Koehler, and M. Hook. 2004. Identification and biochemical characterization of two novel collagen binding MSCRAMMs of Bacillus anthracis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:51760-51768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang, R., R. Wu, G. Joachimiak, S. K. Mazmanian, D. M. Missiakas, P. Gornicki, O. Schneewind, and A. Joachimiak. 2004. Structures of sortase B from Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus anthracis reveal catalytic amino acid triad in the active site. Structure (Cambridge) 12:1147-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]