Abstract

Tuberculosis, a deadly and contagious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, remains a significant global public health threat. HIV co-infection significantly increases the risk of active TB recurrence and prolongs medical treatment for tuberculosis (TB). The study focuses on using advanced machine learning (ML) techniques to predict TB incidence and HIV-TB co-infection using data from the 2023 World Health Organization (WHO) Global TB burden database. The estimated rate for all types of tuberculosis per 100,000 people (E_inc_100k) and the estimated rate of HIV-positive tuberculosis incidence per 100,000 people (e_inc_tbhiv_100k) are the two main goal factors in the dataset. F1 score, accuracy, precision, recall, and the Receiver Operating Characteristic-Area Under the Curve (ROC-AUC) were among the important metrics used to evaluate the model’s performance. With 99.7% accuracy, 99.80% precision, 99.6% recall, a 99.7% F1 score, and a 99.7% ROC-AUC score, the Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) model outperformed other models for e_inc_100k. The e_inc_tbhiv_100k records outstanding performance from the Gradient Boosting (GB) model, with 98.58% accuracy, 98.32% precision, 98.73% recall, a 98.53% F1 score, and a 98.58% ROC-AUC score. Finally, the study aligns with the UNAIDS and WHO End TB Strategy, indicating a progression in combating TB and TB-HIV co-infection in public health workflow.

Keywords: Explainable AI; HIV; Machine learning; Tuberculosis; WHO, infection

Subject terms: Microbiology, Molecular biology

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is an ancient human disease, with Mycobacterium tuberculin as the causative organism. TB remains a significant threat to humanity and ranks as the second leading cause of mortality among humans following Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS). TB most frequently affects the respiratory system however, it might have adverse effects on different organs in the body. TB transmission is airborne, through tiny droplets emanating from coughs or sneezes from the carrier1. Clinically, TB is presented as pulmonary or consumption tuberculosis (PTB) and extrapulmonary TB (EPTB)2. PTB is contagious and spreads through airborne droplets from coughs, and sneezes. It could be latent or active, however in all cases, proper therapeutic interventions are administered to treat the ailment3. Similarly, EPTB occurs beyond the airways (lungs) but is not limited to lymph, pleura, bones, genital urinary system and central nervous system (CNS)4.

Globally, there was a reduction in the prevalence of TB. But in 2022, there was a rapid surge of 7.5 million newly affected individuals. This significant increase is because of the availability and delivery of healthcare services, possibly due to a substantial accumulation of individuals who contracted tuberculosis in previous years but experienced delayed diagnosis due to COVID-19 disruptions5. In 2021, the Global TB Report recorded 8.2 million cases, however, the year 2020 recorded the highest surge of 9.1 million TB cases. This surge was because WHO began global TB monitoring around the middle of 1990 6. Meanwhile, the global TB report records projected 2025 to end all TB cases. The objective is to decrease the occurrence of TB by 50%, but between the years 2015 and 2022, an 8.7% reduction rate has been achieved. Also, the Global TB Report5 proposed a 75% reduction in the number of deaths associated with TB. So far, a 19% reduction has been achieved between 2015 and 2022. Furthermore, to achieve the 2025 goal, 40 million individuals are expected to be treated across all ages. Also, 6 million individuals living with HIV and co-inhabited with TB were expected to be treated. In all, this 10-year plan (2015 to 2025) budgeted 13 billion United States Dollars (USD) per year for both diagnostic and therapeutic measures of TB. But so far in 2022, an estimated 5.8 billion USD has already been invested in TB research5. Meanwhile, the simultaneous presence of both TB and HIV-TB co-infection illnesses poses distinct challenges since both diseases have a mutual connection that leads to significant negative consequences7. For instance, Africa alone had a significant 25%5 proportion of the overall TB infections7 globally. Africa recorded over 2 million,500,000 individuals that become sick due to TB, accounting for 25% of the global TB incidence, and its death rate exceeded 424,000 out of a global death toll of 1.3 million5. WHO reported that the TB, and HIV-TB statistics in Africa are based on incidence cases for every 1 million population8. On the other hand, 2,017 TB cases were reported among children for every 100, 000 population. The TB-HIV co-infected children are 4 persons in every 100 population8. The incidences are attributed to poverty, malnutrition, and people living in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs)9. Childhood TB has been on the rise since 2022; about 20% of Childhood TB cases have now been identified, although pragmatic steps have already been mapped out during 2024 World TB Day10.

Despite the significant progress in the management of TB, the emergence of drug-resistant strains, particularly Multiple-drug-resistant TB (MDR-TB), is a growing challenge11. Early diagnosis and treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) can lead to a rapid reduction in infection transmission, especially in susceptible individuals like children or those with impaired immune systems. Also, early detection of MDR-TB allows for the implementation of appropriate treatment protocols before the germs develop resistance to further medications, enhancing the likelihood of successful therapy and complete recovery. Timely intervention also reduces the death rate by halting the disease’s progression to critical phases and reducing the likelihood of complications and mortality linked to MDR-TB12. Delayed diagnosis can lead to incomplete or inefficient treatment, reducing the development of further drug-resistant strains.

TB and human immune defiance virus co-infection occurs when both TB and HIV are present in an individual at the same time. The presence of two simultaneous burdens poses intricate challenges based on the diagnosis and treatment as well as TB-HIV infection. In co-infection, the immune system is weakened, thereby hindering TB control13. Again, HIV-positive individuals rapidly accelerate to active TB as compared to individuals with negative HIV status14. More so, this makes the diagnosis very challenging because the symptoms mimic another disease, whereas co-infection with HIV makes the diagnosis more complex. Despite this, HIV influences the efficacy of TB medications. Furthermore, the co-infection is a serious global burden, particularly in regions with endemic HIV status14.

Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) and public health

TB incidence and HIV-TB co-infection are complex pathologies, encompassing a broad spectrum of symptoms spanning from moderate infiltrates to severe lesions, complicates accurate and reliable identification with conventional techniques. XAI presents an appropriate intervention to this health challenge, aiding healthcare professionals in obtaining rapid diagnosis while also providing the professional practical information regarding the predictions made by AI models15. XAI recently has gained popularity in healthcare, facilitating transparent as well as an interpretable ML models. There are different forms of XAI, majorly, Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP), Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME), and Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM), which have been utilized in various models relating to public health. SHAP was employed in public health to explain feature contributions relating to the prediction of disease, thereby making AI results comprehensible, especially to individuals without prior knowledge of AI. LIME explains features associated with specific illness predictions, thus making intricate modelling interpretable, while the Grad-CAM was employed in public health to make visual explanations about AI predictions1. This study employs SHAP and LIME XAI as the most current significant discussions in XAI in public health, for example, the study by Peng, A. et al.16 who utilized SHAP XAI for the early prediction of TB patients comorbid with diabetes, Gichuhi et al.,17 employed ML models and XAI for the detection of risk associated with individuals non adherence to TB drugs in Uganda and Ngema et al.,18 that employed XAI for the viral suppression of HIV patients.

Machine learning in TB incidence and HIV-TB Co-infection

Machine Learning (ML) is a crucial AI component19 that aids in precise predictions by analyzing data. It efficiently handles large datasets, provides valuable insights, and systematically mitigates cumbersomeness20,21. However, the quality of the dataset significantly impacts the accuracy and reliability of predictions, especially in cases of biased datasets. In this study, ML was used to predict TB incidence and HIV-TB co-infection using the WHO TB burden dataset published in 2023. ML helps in creating patterns, promoting personalized therapeutic interventions, and minimizing negative consequences. It also efficiently allocates resources and directs high-risk locations22.

The integration of ML for TB and HIV-TB prediction signifies a notable progression in public health studies, especially using extensive datasets from WHO. In this study, we employ advanced ML methodologies alongside SHAP and LIME XAI, as compared with the conventional statistical techniques which lack transparency in their approaches to decision-making. Models like XGB and Gradient GB, in conjunction with SHAP and LIME, provide a comprehensive interpretable framework that illustrates intricate features like population, case notification, mortality rate, and low and high risk, thus making them easy to understand and actionable. Previous studies predominantly utilized traditional regression-based methods to comprehend the epidemiology of TB and HIV-TB. Although these methodologies offered fundamental insights, they were inadequate in predicting accuracy and explainability for effectively guiding focused public health initiatives. This study combines strong prediction modeling with XAI, facilitating precise risk categorization and the identification of essential epidemiological parameters, addressing the vital need for public health decision-making experts. Using a dataset from WHO improves the worldwide relevance of our study, as the dataset encompasses a wide array of regional, social, and economic factors affecting TB and HIV-TB incidence. This study’s result can accurately identify high-risk areas and facilitate resource prioritization, including targeted case-finding initiatives and the optimized distribution of diagnostic tools in resource-limited environments.

As a result, in the context of this study, we bridged the gap by incorporating XAI techniques into comprehensive ML frameworks, a promising insight using feature variables such as population size and case notification rates. These innovations guarantee interpretability without compromising accuracy.

Literature review

In recent times, there has been renewed interest in TB occurrence and HIV-TB co-infection because it presents notable healthcare challenges across the globe. As a result, researchers have shown an increased interest in TB and HIV-TB co-infections. Among them are studies by Suárez et al.,23 on the incident rate of HIV-TB in the Cologne–Bonn region using 4673 individuals living with HIV and AIDS as the dataset. Suárez et al. recorded incidence rates per 100 patients in sub-Saharan Africa and Germany as 0.181 and 0.053. Also, Agudelo et al.,24 focus on complications experienced by 128 patients with HIV-TB. The result showed that 11.7% of the patients had drug toxicity while 5.5% was recorded as a mortality rate. Similarly, Tiewsoh et al.25 studied the clinical presentation and diagnosis of 58 patients infected with HIV-TB simultaneously. The findings showed that 67% of the patients manifested several clinical symptoms like fever while 32.7% had gastrointestinal tract (GIT) symptoms. 36.2% of the patients had a Cluster of Differentiation (CD4) count of 220 cells/µL, 50% opportunistic infection, and 37.9% oral candidiasis. Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that African scholars play a pivotal role in the study of TB Incidence and HIV-TB co-infection. For instance, Ugwu et al.26 demonstrated the occurrence rate of TB, drug-resistant TB, plus HIV-TB rate in Enugu Nigeria, using 868 individuals across different geo-political zones. Ugwu et al. findings are noteworthy, 20.3% of 868 are HIV serological positive, 16.7% are HIV-TB positive, and 33.3% have only TB. In the same way, Alene et al.,27 studied the geographical distribution of TB-HIV co-infection in Ethiopia using 1,830,880 and 192,359 cases of HIV and TB as datasets. The study reported a high incidence of 14.5% for TB-HIV and 7.34% incidence for HIV-TB, respectively. In the above studies a cross-sectional approach using statistical techniques was utilized. However, the incorporation of ML has several advantages because ML models handle complex data, achieve higher accuracy, and identify features from the data that ordinarily will be evaluated manually using a statistical approach. As a result, the study by Cobre et al.28 using 6418 HIV/AIDS and pulmonary TB patients demonstrated ML application in TB Incidence and HIV-TB co-infection. The result showed several diagnostic biomarkers for HIV/AIDS and TB co-infections.

Meanwhile, the Scopus database recorded 909 studies on TB and HIV co-infection between 2019 and 2024. These studies’ keyword was used to create a bibliometric analysis of TB and HIV co-infection keywords as recorded in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Bibliometric analysis of TB, TB-HIV co-infection Scopus 2024.

In this study, we employ ML models in the evaluation of the occurrence of TB as well as its co-infection with HIV. This study identifies the patterns, potential hazards, and approaches for TB and TB-HIV co-infection intervention.

Material and method

The data utilized in this study was sourced from the WHO database for the 2023 tuberculosis report29 under the WHO TB burden estimates [> 1 Mb]. This data was adopted due to its comprehensiveness, credibility, standardization, and transparency for the easy public access, on the progress and monitoring of diseases at the global level. The study was done using the following details, Time and time of report, 9/19/2024, 10:04:53pm, Operating System (OS), Windows 10 Pro 64-bit, Language used was English, System Processor-11th Gen Intel (R) Core (TM) i7, Inbuilt memory-65,536 MB RAM, Python version 3.10.12 (main, Aug. 29, 2024, 16:56:48) [GCC 11.4.0].

The dataset revealed the annual released comprehensive report of 215 countries on TB burden globally. The countries are grouped according to their regions: Africa (AFR), America (AMR), Eastern Mediterranean (EMR), Europe (EUR), South East Asia (SEA), and Western Pacific (WPR) with the respective participating countries recorded in Table 1.

Table 1.

TB burden distribution of various countries.

| Regional code | AFRa | AMRb | EMRc | EURd | SEAe | WPRf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of countries | 1070 | 1025 | 506 | 1237 | 251 | 828 |

a Africa, b America, c Eastern Mediterranean, d Europe, e South East Asia, f Western Pacific.

Context: The number of nations classified by WHO regional codes in 2023, highlighting their distribution across the six WHO regions.

The dataset was downloaded as a Comma-Separated Values (CSV) file on Microsoft Excel. The downloaded CSV file has 4918 columns and 50 rows. However, for us to study TB incidence and HIV-TB co-infection using the ML model we used eight variables that demonstrated significant characteristics of both TB and HIV diseases. These variables were coded with their brief explanations as seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Dataset variable and explanation.

| Variable code | Explanation |

|---|---|

| e_inc_100k | Estimated rate of all forms of TB cases per 100,000 population |

| e_inc_tbhiv_100k | Estimated rate of all forms of TB cases who are HIV seropositive per 100,000 population |

| e_pop_num | Estimated total population number |

| e_tbhiv_prct | Estimated HIV in incident TB (per cent) |

| e_mort_100k | Estimated mortality of TB cases (all forms) per 100,000 population |

| cfr | Estimated TB case fatality ratio |

| c_newinc_100k | Case notification rate, per 100,000 population |

| c_cdr | Case detection rate (all forms), percent |

Data analysis

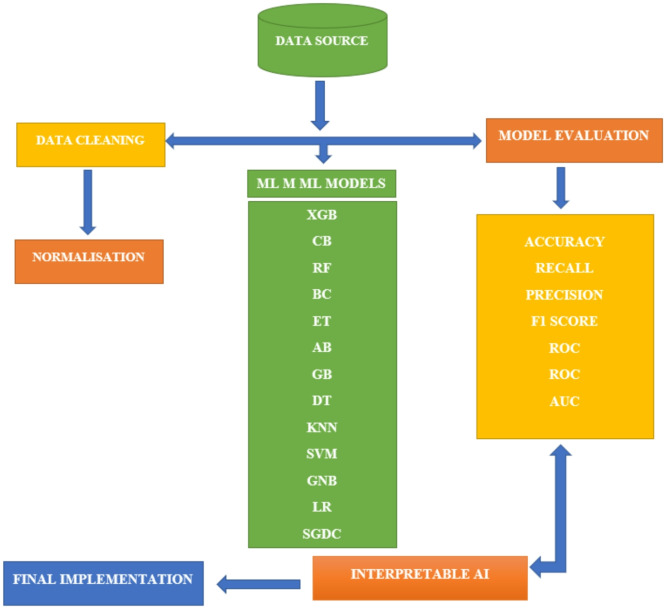

The study’s experimental framework is described in this section. The dataset is analysed using a variety of ML techniques. As shown in Fig. 2, these processes comprise data exploration methods including data collection, data preparation, model construction, evaluation of performance, and XAI deployment.

Fig. 2.

Flow chart showing methodological framework of this study.

In this study, we performed a preliminary analysis of the dataset using Microsoft Excel 2019, MSO) 16.0.10409.20028) with 00414-50000-00000-AA394 and AFEC07C1-E433-4F5C-903D-23F0CF3E040A as the product and Session identity (ID). This includes data preprocessing so to remove outliers. The dataset is also post-processed and then normalized using Python 3.10.2 64-bit. The descriptive features of the entire dataset and the target variables: e_inc_100k and e_inc_tbhiv_100k were plotted using a histogram, as can be seen in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Histogram of the variables.

We performed regression analysis on the dataset, which shows a strong correlation to showcase the relationship of estimated rate of all forms of TB cases per 100,000 population and TB-HIV. The regression statistics show 0.9826 for multiple regressions, R square value of 0.9965 and 0.9656 for adjusted R, and 34.2923 as standard error. Also, the regression statistics proved inadequate to elucidate data intricacies and non-linear correlations, prompting us to use ML models. Despite the regression straightforward modelling approach, it is inadequate for addressing complex patterns and high-dimensional data, especially for TB and HIV-TB predictions.

We split the dataset into training (3687, 7) and testing (1230, 7) before modelling. The dataset is split to prevent overfitting or underfitting of the models, which enhances the optimal performance of the hyperparameters and each of the model’s generalizability. The statistical distribution of the training and testing dataset is recorded in Tables 3, 4, 5, and 6 for both e_inc_100k and e_inc_tbhiv_100k.

Table 3.

Training statistics for e_inc_100k.

| Variable | mean | stdn | mino | 25%p | 50%q | 75%r | maxs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e_inc_100kg | -6.9 × 10− 17 | 1.0 | -0.66 | -0.60 | -0.41 | 0.19 | 7.87 |

| e_pop_numh | -4.8 × 10− 18 | 1.0 | -0.25 | -0.24 | -0.20 | -0.09 | 10.81 |

| e_tbhiv_prcti | 1.8 × 10− 16 | 1.0 | -0.78 | -0.68 | -0.30 | 0.05 | 5.62 |

| e_mort_100kj | 1.7 × 10− 17 | 1.0 | -0.47 | -0.46 | -0.39 | -0.03 | 9.32 |

| cfrk | 4.9 × 10− 17 | 1.0 | -1.24 | -0.63 | -0.33 | 0.43 | 6.35 |

| c_newinc_100kl | 9.3 × 10− 17 | 1.0 | -0.71 | -0.61 | -0.33 | 0.16 | 8.22 |

| c_cdrm | -1.2 × 10− 16 | 1.0 | -3.95 | -0.61 | 0.35 | 0.73 | 8.95 |

Table shows training statistics of e_inc_100k variable using WHO TB burden dataset published in 2023.

g Estimated rate of all forms of TB cases per 100,000 population, h Estimated total population number, i Estimated HIV in incident TB (percent), j Estimated mortality of TB cases (all forms) per 100,000 population, k Estimated TB case fatality ratio, l Case notification rate, per 100,000 population, m Case detection rate (all forms), percent, n Standard Deviation o minimum, p First Quartile (Q1), q Median (Q2), r Third Quartile (Q3), s maximum.

Table 4.

Testing statistics for e_inc_100k.

| Variable | mean | stdn | mino | 25%p | 50%q | 75%r | maxs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e_inc_100kg | -0.01 | 0.97 | -0.66 | -0.60 | -0.42 | 0.24 | 6.10 |

| e_pop_numh | 0.02 | 1.05 | -0.25 | -0.25 | -0.21 | -0.08 | 10.78 |

| e_tbhiv_prcti | 0.02 | 1.04 | -0.78 | -0.69 | -0.30 | 0.05 | 5.62 |

| e_mort_100kj | 0.00 | 0.95 | -0.47 | -0.46 | -0.39 | -0.03 | 7.89 |

| Cfrk | 0.01 | 1.03 | -1.24 | -0.63 | -0.33 | 0.43 | 6.35 |

| c_newinc_100kl | -0.03 | 0.92 | -0.71 | -0.62 | -0.36 | 0.17 | 6.36 |

| c_cdrm | -0.02 | 1.02 | -3.94 | -0.67 | 0.35 | 0.73 | 5.73 |

Table shows testing statistics of e_inc_100k variable using WHO TB burden dataset published in 2023.

g Estimated rate of all forms of TB cases per 100,000 population, h Estimated total population number, i Estimated HIV in incident TB (percent), j Estimated mortality of TB cases (all forms) per 100,000 population, k Estimated TB case fatality ratio, l Case notification rate, per 100,000 population, m Case detection rate (all forms), percent, n Standard Deviation o minimum, p First Quartile (Q1), q Median (Q2), r Third Quartile (Q3), s maximum.

Table 5.

Training statistics for e_inc_tbhiv_100k.

| Variable | mean | stdn | mino | 25%p | 50%q | 75%r | maxs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e_inc_tbhiv_100kt | 3.3 × 10− 17 | 1.0 | -0.33 | -0.33 | -0.30 | 0.002 | 11.91 |

| e_pop_numh | 3.5 × 10− 17 | 1.0 | -0.25 | -0.25 | -0.21 | -0.09 | 10.41 |

| e_tbhiv_prcti | 3.4 × 10− 17 | 1.0 | -0.78 | -0.68 | -0.30 | 0.10 | 5.51 |

| e_mort_100kj | -7.7 × 10− 17 | 1.0 | -0.48 | -0.46 | -0.39 | -0.05 | 9.48 |

| cfrk | 5.4 × 10− 17 | 1.0 | -1.23 | -0.63 | -0.33 | 0.42 | 6.28 |

| c_newinc_100kl | -4.4 × 10− 17 | 1.0 | -0.72 | -0.61 | -0.32 | 0.17 | 8.35 |

| c_cdrm | 2.1 × 10− 16 | 1.0 | -3.90 | -0.60 | 0.36 | 0.74 | 8.90 |

Table shows training statistics e_inc_tbhiv_100k variables using WHO TB burden dataset published in 2023.

t Estimated rate of all forms of TB cases who are HIV seropositive per 100,000 population, h Estimated total population number, i Estimated HIV in incident TB (per cent), j Estimated mortality of TB cases (all forms) per 100,000 population, k Estimated TB case fatality ratio, l Case notification rate per 100,000 population, m Case detection rate (all forms), per cent, n Standard Deviation, o minimum, p First Quartile (Q1), q Median (Q2), r Third Quartile (Q3), s maximum.

Table 6.

Testing statistics for e_inc_tbhiv_100k.

| Variable | mean | stdn | mino | 25%p | 50%q | 75%r | maxs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e_inc_tbhiv_100kt | 0.01 | 1.03 | -0.33 | -0.33 | -0.30 | 0.00 | 10.42 |

| e_pop_numh | -0.02 | 0.90 | -0.25 | -0.25 | -0.21 | -0.10 | 10.41 |

| e_tbhiv_prcti | 0.04 | 0.97 | -0.78 | -0.69 | -0.35 | -0.10 | 4.50 |

| e_mort_100kj | 0.01 | 1.02 | -0.48 | -0.46 | -0.40 | 0.00 | 8.49 |

| Cfrk | -0.02 | 0.99 | 1.23 | -0.63 | -0.33 | 0.40 | 6.28 |

| c_newinc_100kl | 0.05 | 1.05 | -0.72 | -0.60 | -0.32 | 0.21 | 8.50 |

| c_cdrm | 0.03 | 0.99 | -3.90 | -0.54 | 0.36 | 0.74 | 6.23 |

Table shows testing statistics e_inc_tbhiv_100k variables using WHO TB burden dataset published in 2023.

t Estimated rate of all forms of TB cases who are HIV seropositive per 100,000 population, h Estimated total population number, i Estimated HIV in incident TB (percent), j Estimated mortality of TB cases (all forms) per 100,000 population, k Estimated TB case fatality ratio, l Case notification rate per 100,000 population, m Case detection rate (all forms), percent, n Standard Deviation, o minimum, p First Quartile (Q1), q Median (Q2), r Third Quartile (Q3), s maximum.

Furthermore, we used a correlation matrix to display the strength and direction of the relationship between the variables in the dataset. The correlation matrix of the training and testing dataset offers significant information on the target variables (e_inc_100k and e_inc_tbhiv_100k) as shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Correlation matrix e_inc_100k and e_inc_tbhiv_100k.

Model development and simulation

Globally TB and HIV continue to pose a significant health threat to the entire population. It has been recorded that the co-infection of the duo complicates both therapeutic and diagnostic processes. Similarly, statistical approaches have limitations in the analysis of TB incidence alongside its co-infection with HIV. As a result, we employed state-of-the-art (SOTA) ML models to obtain more profound insights into the incidence. These SOTA ML models: Gradient Boosting (GB), CatBoost (CB), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), Extra Trees (ET), Random Forest (RF), AdaBoost (AB), Bagging Classifier (BC), Decision Tree (DT), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Stochastic Gradient Descent Classifier (SGDC), Gaussian Naïve Bayes (GNB) were used in this study for the prediction of TB incidence and HIV-TB co-infection. We employed the advantages of the aforementioned models to develop a model that is robust, informative, and interpretable and that could predict the intricacies of TB-HIV co-infection epidemiology. The SOTA models used in this study can be classified as boosting, ensemble, and singly categorized models. The boosting models combine sequentially different weak models as a single model30. They include GB, CB, and XGB, which could reduce errors during training sections, thus improving the predictive ability of the TB incidence. The boosting models, especially XGB, are rapid and efficient. Additionally, the models could be classified as ensemble models which exhibit collaborative ability to create a more accurate and robust solution. This model involves a cohort of specialists working together to address complex issues, leveraging their unique perspectives and knowledge to reach a more effective solution. The ensemble models include ET, RF, and AB. Next are the singly categorized models. They are DT, KNN, LR, SVM, SGDC, and GNB. DTs are flowchart-like representations showing the attributes and decision rules of the dataset. DTs are highly interpretable in handling categorical datasets. The KNN model is simple, non-parametric, and employed according to KNN features31 while LR is another popular simple model, linear, interpretable, and more efficient. Meanwhile, SVM is used as a classification model because it can deal with high-dimensional data by locating the hyperplane separating the feature spaces of the dataset32. SGDC, a classification algorithm repeatedly adjusts model parameters to reduce the loss function. It is applied to hinge or to log loss for SVM and LR respectively33. SDGC performs excellently in large datasets. GNB necessitates that the dataset features adhere to a Gaussian distribution. Above all, GNB performed excellently in a large number of dimensions. Overall, the dataset is then simulated in the Python library and each of the SOTA is applied to the dataset using Python codes. The SOTA model’s efficacy was evaluated using metrics such as Accuracy (%), Precision (%), Recall (%), F1 Score (%), and ROC AUC Score (%). The results of the simulation are recorded in the result section.

Result

The overall results after the simulation of the dataset into the Python library were recorded in Tables 7 and 8.

Table 7.

Result of e_inc_100k variable performances.

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1 Score (%) | ROC AUC Score (%) u |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGB | 99.70 | 99.80 | 99.60 | 99.70 | 99.70 |

| CB | 99.70 | 99.60 | 99.80 | 99.70 | 99.69 |

| RF | 99.59 | 99.80 | 99.40 | 99.60 | 99.60 |

| BC | 99.59 | 99.80 | 99.40 | 99.60 | 99.60 |

| ET | 99.49 | 99.60 | 99.40 | 99.50 | 99.49 |

| AB | 99.29 | 99.40 | 99.20 | 99.30 | 99.29 |

| GB | 99.19 | 99.60 | 98.80 | 99.20 | 99.19 |

| DT | 98.58 | 98.40 | 98.80 | 98.60 | 98.57 |

| KNN | 65.65 | 66.07 | 66.33 | 66.20 | 65.64 |

| SVM | 60.26 | 68.37 | 40.28 | 50.69 | 60.55 |

| GNB | 50.91 | 63.79 | 7.41 | 13.29 | 51.54 |

| LR | 50.71 | 50.71 | 100.0 | 67.30 | 50.00 |

| SGDC | 49.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 50.00 |

Table shows e_inc_100k variable performances using the WHO TB burden dataset published in 2023 to predict TB Incidence and HIV-TB co-infection.

GB: Gradient Boosting, CB: CatBoost, XGB: XGB, ET: Extra Trees, RF: Random Forest, AB: AdaBoost, BC: Bagging Classifier, DT: Decision Tree, KNN: K-Nearest Neighbors, LR: Logistic Regression, SVM: Support Vector Machine, SGDC: Stochastic Gradient Descent Classifier, GNB: Gaussian Naive Bayes, u Receiver Operating Characteristic - Area Under the Curve.

Table 8.

Result of e_inc_tbhiv_100k variable performances.

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1 Score (%) | ROC AUC Score (%) u |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GB | 98.58 | 98.32 | 98.73 | 98.53 | 98.58 |

| CB | 98.58 | 98.94 | 98.1 | 98.52 | 98.56 |

| XGB | 98.27 | 98.31 | 98.1 | 98.2 | 98.27 |

| ET | 98.27 | 98.51 | 97.89 | 98.2 | 98.26 |

| RF | 98.07 | 98.72 | 97.26 | 97.98 | 98.04 |

| AB | 97.87 | 97.48 | 98.1 | 97.79 | 97.87 |

| BC | 97.76 | 98.29 | 97.05 | 97.66 | 97.74 |

| DT | 96.85 | 97.84 | 95.57 | 96.69 | 96.8 |

| KNN | 61.59 | 60.67 | 57.59 | 59.09 | 61.44 |

| LR | 51.83 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 50.00 |

| SVM | 50.51 | 49.18 | 82.7 | 61.68 | 51.64 |

| SGDC | 48.17 | 48.17 | 100.0 | 65.02 | 50.0 |

| GNB | 48.07 | 48.05 | 95.99 | 64.04 | 49.76 |

Table shows e_inc_tbhiv_100k variable performances using the WHO TB burden dataset published in 2023 to predict TB Incidence and HIV-TB co-infection.

GB: Gradient Boosting, CB: CatBoost, XGB: XGB, ET: Extra Trees, RF: Random Forest, AB: AdaBoost, BC: Bagging Classifier, DT: Decision Tree, KNN: K-Nearest Neighbors, LR: Logistic Regression, SVM: Support Vector Machine, SGDC: Stochastic Gradient Descent Classifier, GNB: Gaussian Naive Bayes, u Receiver Operating Characteristic - Area Under the Curve.

Discussion

As recorded in this study, 13 models (GB, CB, XGB, ET, RF, AB, BC, DT, KNN, LR, SVM, SGDC, and GNB) were used to evaluate TB and HIV–TB co-infection. The values in Tables 7 and 8 were recorded in 14 rows and 6 columns labelled Model, Accuracy (%), Precision (%), Recall (%), F1 Score (%), and ROC AUC Score (%). For e_inc_100k, XGB, CB, RF, BC and ET are the top 5 performing models. However, the XGB model demonstrated exceptional performance among all other models, with an accuracy of 99.7%, precision of 99.80%, recall of 99.60%, F1 score of 99.70%, and ROC AUC score of 99.70% as recorded in Table 7. Additionally, for e_inc_tbhiv_100k, GB, CB, XGB, ET and RF are also the 5 performing models. GB demonstrated exceptional performance in accuracy (98.58%), precision (98.32%), recall (98.73%), F1 Score (98.53%), and ROC AUC Score (98.58%) as can be seen in Table 8. XGB and CB had excellent performance because of their iterative characteristics that allow models to improve their accuracy. Despite its boosting effects, it prevents overfitting because TB incidence cuts across diverse geographical locations. Again, the XGB and CB models are robust, in handling the different features of the dataset such as the number of seropositive patients, the incident ratio of HIV and TB, the estimated fatality and other forms of cases. On the other hand, SGDC and GNB performed poorly because of their inability to handle the complex nature of the dataset as a result, they could not handle the imbalances of TB incidence and HIV-TB co-infection; to ascertain the robustness of the best-performing models, we compared our results with other published studies. As a result, we found out that the study by Duffy et al.34 employed a similar model: XGB, RF, SVM, and KNN like our study. However, our study performed better compared to Duffy et al. study. First, we used the 4917 datasets unlike 550. Again, the model showed that XGB had 97% and 93% as AUC values for HIV negative and positive. Further classification showed that the AUC values of all cases of TB and latent TB in HIV (positive and Negative) are 93%, and then the AUC value of all TB and latent TB cases in co-infection with other diseases was 92%. as compared with our study’s XGB AUC value of 99.7% and 98.3% for e_inc_100k and e_inc_tbhiv_100k respectively. Next is RF, which recorded an AUC value of 95% for all TB cases irrespective of latent in HIV positive and negative individuals and 89% for all cases of TB in both HIV status and other co-infection, unlike our study that recorded 98.0%. However, our study failed to perform optimally in terms of KNN as compared with Duffy et al. which showed an excellent value of 93% and 89% respectively for all TB cases co-infected with HIV and other diseases unlike ours which recorded an AUC value of 65.7% and 61.4% for both e_inc_100k and e_inc_tbhiv_100k. Similarly, Eka Janarwati et al.,35 used the Carmel algorithm (CA) and Ensemble techniques (ET) to offer methods utilized to detect TB from HIV-positive patients. In the study, the RF, AdaBoost, and XGB models were employed just like ours. According to Eka Janarwati et al. XGB was the best model based on accuracy and F-1 score values at 89% and 75% respectively. However, our study showed superior performance of XGB with accuracy values of 99.7, 98.3 for e_inc_100k and e_inc_tbhiv_100k and F-1sore of 99.7% and 98.5%.

Meanwhile, using a spider plot, we demonstrated the characteristics of the top 5 performing models: XGB, CB, RF, BC, and ET for the e_inc_100k and GB, CB, XGB, ET, and RF for e_inc_tbhiv_100k evaluation. The top 5 performing were plotted to show the performances according to the metrics. As can be seen from Fig. 5, the plot has 5 axes corresponding to these models: XGB, CB, RF, BC, and ET; GB, CB, XGB, ET and RF with the apex of the ring corresponding to 100%. All the models according to the figure are almost 100% indicating similarity in performance across the dataset (TB and HIV). In summary, the figure indicates that the models have similar characteristics in the prediction of TB and HIV co-infection.

Fig. 5.

The best-performing model for e_inc_100k and e_inc_tbhiv_100k.

Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI)

XAI encompasses a collection of procedures and techniques that enable human users to understand and have confidence in the outcomes and output generated by ML algorithms. The field of XAI focuses on addressing the black box which the model cannot explain. Primarily XAI enhances the model comprehensibility as well as transparency based on AI which can be understood by end users. This gives confidence to the AI’s decision-making process, thus providing a basis for evaluating decisions. In this, we used the SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) method which provides detailed explanations for the results of models in this study. The study utilized the XGB model to evaluate and interpret the SHAP, a tool that highlights the combined impact of both positive and negative factors from an initial value, resulting in a projected outcome. The XAI of XAI for e_inc_100k and e_inc_tbhiv_100k are represented in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

XAI for e_inc_100k and e_inc_tbhiv_100k.

In other for us to demonstrate our model’s trustworthiness, we also employed LIME XAI to explain the robustness of our study. The LIME XAI Fig. 7 has prediction probabilities, contributions, indicated as low or high risk, the features, and values.

Fig. 7.

LIME XAI showing the probabilities as low or high risk.

Prediction probabilities are blue (low risk) and white bars (high risk). Numbers (positive/negative) are the extent to which the feature contributes to making prediction.

The bars (blue and orange) are positive and negative (high) risk contributions. The length of each bar depicts the sizes of individual parameter contribution. The value as recorded in Table 9 summarizes the LIME XAI. Therefore, for SHAP XAI, as recorded in in this shows the overall significance contributions made by the features and at specific detailed instances while LIME explains each of the parameters based on their high or low risk. On top of that the XAI’s used in this study were in agreement with epidemiological results indicating our model trustworthiness.

Table 9.

Summary of LIME XAI description.

| Dataset Features | Direction of contribution | Positive/negative contribution | Feature risk explanation | Size of prediction Probability | Feature Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e_mort_100k | <= -0.46 | very high positive | Low | 0.43 | -0.48 |

| c_newinc_100k | <= -0.62 | positive | Low | 0.32 | -0.68 |

| cfr | <= -0.62 | very high negative | high | 0.21 | -0.92 |

| c_cdr | 0.35 < c_cdr < = 0.72 | slight positive | Low | 0.07 | 0.72 |

| e_pop_num | -0.21 < e_pop_num <= | negative | high | 0.06 | -0.18 |

| e_tbhiv_prct | -0.67 < e_tbhiv_prct <= | very low positive | Low | 0.04 | -0.64 |

Ultimately, the results from this study when integrated into public health workflow constitutes a progression in the fight against TB and TB-HIV co-infection as recommended by United Nations Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS and WHO End TB Strategy.

Limitations

This study’s main limitation is centered on the WHO TB burden dataset. The dataset lacked regional disparities and intricate details of localized data. As a result, may affect the accuracy of the ML models. Also, the result of this study may not be fully utilized in areas with dominant epidemiological characteristics, varied medical systems, and social and economic factors that are not represented in the dataset. These were mitigated by using an explainable AI for a universal interpretation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the comparative study on tuberculosis incidence and HIV-TB co-infection using the ML model. We used the ML model in the identification of patterns and areas associated with a high prevalence of this multiple infection. In this study, e_inc_100k and e_inc_tbhiv_100k showed that Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) performed excellently based on accuracy as 99.7%, Precision as 99.80%, Recall as 99.6% (%), F1 Score as 99.7% and 99.7% as Receiver Operating Characteristic - Area Under the Curve (ROC-AUC) Score (%). Similarly, e_inc_tbhiv_100k showed that Gradient Boosting (GB) performed excellently based on Accuracy (%) as 98.58, Precision (%) as 98.32, Recall (%) as98.73, F1 Score (%) as 98.53 and ROC AUC Score (%) as 98.58.

Additionally, the result of this study could be implemented into public health workflow. The excellent performances of XGB and GB will enable epidemiologist decision makers and other healthcare professionals to adequately allocate resources but not limited drugs, diagnostic resources, awareness campaigns for individuals that need them most. This also ensures timely intervention in cases of outbreak. On top of that, SHAP values are also very significant to the epidemiologist showcasing driving factors (mortality, size, and case rate) to TB and TB_HIV co infections.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their appreciation to King Saud University for funding the publication of this research through the Research Support Program (RSP2025R167), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Abbreviations

- TB

Tuberculosis

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- SOTA

State-of-the-art

- ML

Machine learning

- XAI

Explainable artificial intelligence

- WHO

World Health Organization

- ROC-AUC

Receiver Operating Characteristic-Area Under curve

- AIDS

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

- PTB

Pulmonary tuberculosis

- EPTB

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis

- LMICs

Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- MDR-TB

Multiple-drug-resistant TB

- CD4

Cluster of Differentiation

- AFR

Africa

- AMR

America

- EMR

Eastern Mediterranean

- EUR

Europe

- SEA

South East Asia

- WPR

Western Pacific

- e_inc_100k

Estimated rate of all forms of TB cases per 100,000 population

- e_inc_tbhiv_100k

Estimated rate of all forms of TB cases who are HIV seropositive per 100,000 population

- e_pop_num

Estimated total population number

- e_tbhiv_prct

Estimated HIV in incident TB (percent)

- e_mort_100k

Estimated mortality of TB cases (all forms) per 100,000 population

- cfr

Estimated TB case fatality ratio

- c_newinc_100k

Case notification rate, per 100,000 population

- c_cdr

Case detection rate (all forms), percent

- Std

Standard Deviation

- min

Minimum

- 25%

First Quartile (Q1)

- 50%

Median (Q2)

- 75%

Third Quartile (Q3)

- Max

Maximum

- GB

Boosting

- CB

CatBoost

- XGB

Extreme Gradient Boosting

- ET

Extra Trees

- RF

Random Forest

- AB

AdaBoost

- BC

Bagging Classifier

- DT

Decision Tree

- KNN

K-Nearest Neighbors

- LR

Logistic Regression

- SVM

Support Vector Machine

- SGDC

Stochastic Gradient Descent Classifier

- GNB

Gaussian Naïve Bayes

- CA

Carmel algorithm

- ET

Ensemble techniques

- SHAP

Shapley Additive exPlanations

Author contributions

Conceptualization, writing of initial draft, data, simulation, and technical editing were done by D.I.E., B.B.D, A.G.U, methodology interpretation of result was done by A.G.U, H.A, and D.U.O. In contrast, the entire supervision was done by, D.U.O, S.A, and H.A.

Funding

This project is funded by the Research Support Program (RSP2025R167), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data availability

The data can be found in https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/data.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Coleman, M., Martinez, L., Theron, G., Wood, R. & Marais, B. Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission in High-Incidence Settings—New paradigms and insights. Pathogens11, 1228 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banta, J. E., Ani, C., Bvute, K. M., Lloren, J. I. C. & Darnell, T. A. Pulmonary vs. extra-pulmonary tuberculosis hospitalizations in the US [1998–2014]. J. Infect. Public. Health. 13, 131–139 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan, H. et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis as a risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Transl Med.9, 390 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Djannah, F., Massi, M. N., Hatta, M., Bukhari, A. & Hasanah, I. Profile and histopathology features of top three cases of extra pulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) in West Nusa Tenggara: A retrospective cross-sectional study. Ann. Med. Surg.75, 103318 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global tuberculosis report. (2023). https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240083851

- 6.Menzies, N. A. et al. Progression from latent infection to active disease in dynamic tuberculosis transmission models: A systematic review of the validity of modelling assumptions. Lancet Infect. Dis.18, e228–e238 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olivier, C., Luies, L. W. H. O. & Goals Beyond: managing HIV/TB Co-infection in South Africa. SN Compr. Clin. Med.5, 251 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wondmeneh, T. G. & Mekonnen, A. T. The incidence rate of tuberculosis and its associated factors among HIV-positive persons in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis.23, 613 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foo, C. D. et al. Integrating tuberculosis and noncommunicable diseases care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs): A systematic review. PLOS Med.19, e1003899 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Tuberculosis Day. WHO | Regional Office for Africa (2024). https://www.afro.who.int/regional-director/speeches-messages/world-tuberculosis-day-2024 (2024).

- 11.Alara, J. A. & Alara, O. R. An overview of the global alarming increase of multiple drug resistant: A major challenge in clinical diagnosis. Infect. Disord - Drug TargetsDisorders. 24, 26–42 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan, W., Lu, Y., Chen, R., An, Q. & Yu, Z. Prevention and prognosis of Drug-Resistant tuberculosis. in Diagnostic Imaging of Drug Resistant Pulmonary Tuberculosis (eds Lu, P. X., Lu, H. & Yi, Y.) 257–267 (Springer Nature, Singapore, doi:10.1007/978-981-99-8339-1_17. (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heidary, M. et al. Tuberculosis challenges: Resistance, co-infection, diagnosis, and treatment. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol.12, 1–17 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shamu, S. et al. Study on knowledge about associated factors of tuberculosis (TB) and TB/HIV co-infection among young adults in two districts of South Africa. PLOS ONE. 14, e0217836 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joseph, T., Kenneth, M. H., Rose, N. & Explainable AI for transparent and trustworthy tuberculosis diagnosis: From Mere pixels to actionable insights. East. Afr. J. Inf. Technol.7, 341–354 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng, A. et al. Explainable machine learning for early predicting treatment failure risk among patients with TB-diabetes comorbidity. Sci. Rep.14, 6814 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gichuhi, H. W., Magumba, M., Kumar, M. & Mayega, R. W. A machine learning approach to explore individual risk factors for tuberculosis treatment non-adherence in Mukono district. PLOS Glob Public. Health. 3, e0001466 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ngema, F., Whata, A., Olusanya, M. & Mhlongo, S. XAI-Driven Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Models for Predicting HIV Viral Suppression in Ugandan Patients (Preprint). Preprint at (2024). 10.2196/preprints.68196

- 19.Mustapha, M. T., Ozsahin, I. & Ozsahin, D. U. Chapter 1 - Introduction to machine learning and artificial intelligence. in Artificial Intelligence and Image Processing in Medical Imaging (eds Zgallai, W. A. & Ozsahin, D. U.) 1–19 (Academic, doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-95462-4.00001-7. (2024).

- 20.Moustafa, I. M. et al. Utilizing machine learning to predict post-treatment outcomes in chronic non-specific neck pain patients undergoing cervical extension traction. Sci. Rep.14, 11781 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clement, J. C., Ponnusamy, V., Sriharipriya, K. C. & Nandakumar, R. A. Survey on mathematical, machine learning and deep learning models for COVID-19 transmission and diagnosis. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng.15, 325–340 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang, A., Xing, L., Zou, J. & Wu, J. C. Shifting machine learning for healthcare from development to deployment and from models to data. Nat. Biomed. Eng.6, 1330–1345 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suárez, I. et al. Incidence and risk factors for HIV-tuberculosis coinfection in the Cologne–Bonn region: A retrospective cohort study. Infection10.1007/s15010-024-02215-y (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agudelo, C. A. et al. Outcomes and complications of hospitalised patients with HIV-TB co‐infection. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 26, 82–88 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiewsoh, J. B. A., Antony, B. & Boloor, R. HIV-TB co-infection with clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment, outcome and its relation to CD4 count, a cross-sectional study in a tertiary care hospital in coastal Karnataka. J. Fam Med. Prim. Care. 9, 1160 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ugwu, K. O., Agbo, M. C. & Ezeonu†, I. M. Prevalence of tuberculosis, drug-resistant tuberculosis and HIV/TB co-infection in Enugu, Nigeria. Afr. J. Infect. Dis.15, 24–30 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alene, K. A., Viney, K., Moore, H. C., Wagaw, M. & Clements, A. C. A. Spatial patterns of tuberculosis and HIV co-infection in Ethiopia. PLOS ONE. 14, e0226127 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cobre, A. F. et al. Use of biochemical tests and machine learning in the search for potential diagnostic biomarkers of COVID-19, HIV/AIDS, and pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Braz Chem. Soc.35, e (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Global Tuberculosis Programme. https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/data

- 30.Mosavi, A. et al. Ensemble boosting and bagging based machine learning models for groundwater potential prediction. Water Resour. Manag. 35, 23–37 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang, T. & Chi, G. A heterogeneous ensemble credit scoring model based on adaptive classifier selection: an application on imbalanced data. Int. J. Finance Econ.26, 4372–4385 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandra, M. A. & Bedi, S. S. Survey on SVM and their application in image classification. Int. J. Inf. Technol.13, 1–11 (2021).33527094 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaye, B., Zhang, D. & Wulamu, A. Sentiment classification for employees reviews using regression vector- stochastic gradient descent classifier (RV-SGDC). PeerJ Comput. Sci.7, e712 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duffy, F. J., Thompson, E. G., Scriba, T. J. & Zak, D. E. Multinomial modelling of TB/HIV co-infection yields a robust predictive signature and generates hypotheses about the HIV + TB + disease state. PLOS ONE. 14, e0219322 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eka Janarwati, A. M. & Kurniawan, I. Hasmawati Implementation of Camel Algorithm-Ensemble Method for Tuberculosis Detection on HIV Patients based on Gene Expression Data. in ASU International Conference in Emerging Technologies for Sustainability and Intelligent Systems (ICETSIS) 698–702 (2024). (2024). 10.1109/ICETSIS61505.2024.10459706

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be found in https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/data.