Abstract

Chlamydia pneumoniae is a common human respiratory pathogen that has been associated with a variety of chronic diseases, including atherosclerosis. The role of this organism in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis remains unknown. A key question is how C. pneumoniae is transferred from the site of primary infection to a developing atherosclerotic plaque. It has been suggested that circulating monocytes could be vehicles for dissemination of C. pneumoniae since the organism has been detected in peripheral blood monocytic cells (PBMCs). In this study we focused on survival of C. pneumoniae within PBMCs isolated from the blood of healthy human donors. We found that C. pneumoniae does not grow and multiply in cultured primary monocytes. In C. pneumoniae-infected monocyte-derived macrophages, growth of the organism was very limited, and the majority of the bacteria were eradicated. We also found that the destruction of C. pneumoniae within infected macrophages resulted in a gradual diminution of chlamydial antigens, although some of these antigens could be detected for days after the initial infection. The detected antigens present in infected monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages represented neither chlamydial inclusions nor intact organisms. The use of {N-[7-(4-nitrobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazole)]}-6-aminocaproyl-d-erythro-sphingosine as a vital stain for chlamydiae proved to be a sensitive method for identifying rare C. pneumoniae inclusions and was useful in the detection of even aberrant developmental forms.

Chlamydia pneumoniae is an obligate intracellular parasite whose developmental cycle occurs within a eukaryotic host. As in all chlamydiae, two functionally and morphologically distinct cell types are recognized. The infectious cell type, which is specialized for extracellular survival and transmission, is termed the elementary body (EB), and the intracellular, vegetative cell type is called the reticulate body (RB). Chlamydiae remain within an intracellular vacuole, termed an inclusion, for their entire developmental cycle. Shortly after internalization, EBs begin to reorganize and differentiate into RBs which then multiply by binary fission. Late in the cycle, logarithmic growth of the organism ceases as RBs begin to reorganize as EBs, which are released upon lysis of the host cell (34).

C. pneumoniae is a common human respiratory pathogen. It has been estimated that C. pneumoniae is responsible for up to 10% of all cases of community-acquired pneumonia and 5% of bronchitis and sinusitis cases (27). This organism has also been associated with variety of chronic diseases, including atherosclerosis. C. pneumoniae has been detected in ∼50% of atherosclerotic lesions in patients with cardiovascular disease by PCR, immunocytochemistry, electron microscopy, and culture (reviewed in reference 10). However, the role of this organism in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis remains unknown. One of many questions is how C. pneumoniae is transferred from the site of a primary infection to a developing atherosclerotic plaque. One study demonstrated that in C. pneumoniae-infected mice, bacteria disseminate throughout the body via alveolar and peritoneal macrophages, and the organism was also detected in peripheral blood monocytic cells (PBMCs). In this study the workers proposed that circulating monocytes could be vehicles for dissemination of C. pneumoniae (33). This proposal stimulated investigations of the presence of C. pneumoniae in human PBMCs isolated from blood donors. There have been numerous reports describing C. pneumoniae infection of PBMCs, as well as cytokine production by the cells induced by this organism in vitro (1, 15-17, 20, 25). C. pneumoniae DNA was also detected in PBMCs obtained from patients with cardiovascular disease (6, 8).

In this study we examined the survival of C. pneumoniae within PBMCs isolated from the blood of healthy donors in an effort to differentiate between chlamydiae in a nonreplicative state and dead bacteria. Human monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages were distinguished by the presence of the mannose receptor (MR) (46), which is a specific marker for macrophage differentiation. We found that C. pneumoniae does not survive in cultured monocytes and exhibits only very limited growth in monocyte-derived macrophages. We further demonstrated that most C. pneumoniae EBs are delivered to the lysosomal pathway of infected macrophages and that within these cells the organism is gradually degraded. Although certain chlamydial antigens can be detected for days after the initial infection of monocyte-derived macrophages, these antigens represent neither chlamydial inclusions nor intact organisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification of PBMCs.

PBMCs were isolated from heparinized venous blood of healthy individuals by using a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The whole blood was mixed with 0.9% sodium chloride containing 3% dextran T-500 and incubated at room temperature for 20 min to sediment erythrocytes. After dextran sedimentation the supernatant was centrifuged at 550 × g for 10 min, and cells were then resuspended in 0.9% sodium chloride, underlaid with 10 ml of Ficoll-Paque PLUS (Amersham Biosciences Corp.), and centrifuged for 30 min (26). The PBMCs recovered from the buffy coat were washed twice in Hanks' balanced salt solution, resuspended in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium containing 25 mM HEPES (Invitrogen Corp.), and seeded on glass coverslips in 24-well plates. After 2 h of incubation PBMCs were washed three times with serum-free medium, and isolated cells were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 25 mM HEPES buffer supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum plus 10 μg of gentamicin per ml. The number of monocyte-derived macrophages obtained 8 days after attachment to the coverslips was ∼2 × 105 cells/well, and more than 95% of the cells represented macrophages, as determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis with anti-Mac-1 monoclonal antibody (MAb) (BD Pharmingen).

Cell culture and organisms.

C. pneumoniae AR-39, purchased from the American Type Culture Collection, was propagated in HeLa 229 cells (CCL 2.1; American Type Culture Collection) as previously described (50). Cultures of monocytes, macrophages, or HeLa 229 cells grown on coverslips in 24-well plates were infected with renografin-purified C. pneumoniae in sucrose-phosphate-glutamate buffer at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of ∼1, unless otherwise indicated, by rocking at 37°C for 1.5 h. After infection the inoculum was removed, and the cells were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 25 mM HEPES buffer supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum plus 10 μg of gentamicin per ml at 37°C in an atmosphere consisting of 5% CO2 and 95% humidified air. At various times postinfection, the infected cells were lysed to release infectious EBs. Infected cells were scraped from two coverslips per time with a plastic tip into 0.4 ml of sucrose-phosphate-glutamate buffer, vortexed, and ultrasonically disrupted, and coverslips with fresh monolayers of HeLa cells were infected by centrifugation at 900 × g for 1 h. After 3 days of incubation, the cells were fixed with methanol and stained by indirect immunofluorescence using rabbit antiserum against C. pneumoniae and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin serum. The number of inclusion-forming units per ml was determined. All experiments were repeated at least three times using cells isolated from different donors.

Antibodies.

The anti-mannose receptor monoclonal antibody, isotype immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1), was purchased from BD Pharmingen. Anti-C. pneumoniae AR-39-specific rabbit antiserum was generated in our laboratory. The anti-C. pneumoniae MOMP species-specific MAb GZD1E8, isotype IgG1, was provided by G. Zhong (51). The anti-chlamydial Hsp60 genus-specific MAb A57-B9, isotype IgG1, was previously described by Yuan et al. (54). The anti-chlamydial genus-specific lipopolysaccharide (LPS) MAb EVIH1 (47), isotype IgG2a, was provided by H. Caldwell. The antirickettsial MAb 8-13A4A10, isotype IgG2a, was generated and described by Anacker et al. (3). The monoclonal antibody H4B4, isotype IgG1, to the lysosomal glycoprotein LAMP-2 was obtained from the Developmental Hybridoma Bank. Fluorescent secondary antibodies were purchased from Zymed.

Microscopy.

For transmission electron microscopy, C. pneumoniae-infected PBMCs or HeLa 229 cells were grown on Thermanox coverslips (Fisher Scientific) and fixed with periodate-lysine-paraformaldehyde fixative (9) for 2 h at room temperature. The coverslips were then permeablized with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.12% saponin (Sigma) and incubated overnight with a primary antibody at 4°C. The cultures were then rinsed twice with PBS and incubated at room temperature for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated F(ab′)2 sheep anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.) in PBS containing 0.12% saponin. The coverslips were rinsed in PBS and fixed in 1.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, pH 7.4, plus 5% sucrose for 1 h. They were then rinsed three times with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, plus 7.5% sucrose prior to development with Immunopure metal-enhanced diaminobenzidine substrate (Pierce Chemical Co.). After incubation in the diaminobenzidine substrate, cells were rinsed three times with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 7.5% sucrose and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde-2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer at 4°C for 2 h. Cells were postfixed in 1.0% OsO4-0.8% K4Fe(CN)6 for 15 min, washed with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer and then twice with water, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and embedded in Spurr's resin. Thin sections were cut with an RMC MT-7000 ultramicrotome (Ventana), stained with 1% uranyl acetate and Reynold's lead citrate, and observed at 60 kV with a Philips CM-10 transmission electron microscope (FEI). Images were obtained with an AMT digital camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques) and were processed using the Adobe PhotoShop 7.0 software (Adobe Systems).

For confocal microscopy, HeLa 229 cells or monocyte-derived macrophages cultivated on glass coverslips were infected with C. pneumoniae at an MOI of ∼1. At different times postinfection cells were fixed either with methanol at room temperature for 3 min or with periodate-lysine-paraformaldehyde fixative for 2 h and then permeablized with 0.2% saponin. After incubation with the appropriate primary antibody in PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin or 0.2% saponin, cells were stained with either tetramethyl rhodamine isocyanate-or fluorescein isothiocyanate-goat anti-mouse secondary antibody and/or anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Coverslips were then mounted on glass slides using Mowiol (http://imaging.altervista.org/confocal_protocols/mowiol.html). Fluorescent images were taken with a Zeiss Axiovert Zoom LSM 510 confocal microscope using an excitation wavelength of 488 nm for fluorescein and 543 nm for rhodamine. Intrinsically fluorescent C. pneumoniae EBs were generated by labeling the organism with Cell Tracker Green CMFDA (Molecular Probes, Inc.) as described previously (7).

C6-NBD-ceramide labeling.

Fluorescent {N-[7-(4-nitrobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazole)]}-6-aminocaproyl-d-erythro-sphingosine (C6-NBD-ceramide) (Molecular Probes, Inc.) was complexed with 0.034% defatted bovine serum albumin (dfBSA) in minimal essential medium as described previously (39) to obtain complexes containing ∼5 μM dfBSA and ∼5 μM C6-NBD-ceramide. HeLa 229 cells and monocyte-derived macrophages were infected with C. pneumoniae at an MOI of ∼20. At different times postinfection, the infected cells were incubated with the dfBSA-C6-NBD-ceramide complex at 4°C for 30 min and then rinsed with 10 mM HEPES-buffered calcium- and magnesium-free Puck's saline, pH 7.4. The infected cultures were then incubated at 37°C for 5 h in minimal essential medium containing 0.34% dfBSA to “back-exchange” excess probe from the plasma membrane. Cultures on coverslips were rinsed in 10 mM HEPES-buffered calcium- and magnesium-free Puck's saline, pH 7.4, before mounting for fluorescent microscopy (19).

RESULTS

Development of C. pneumoniae in monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages.

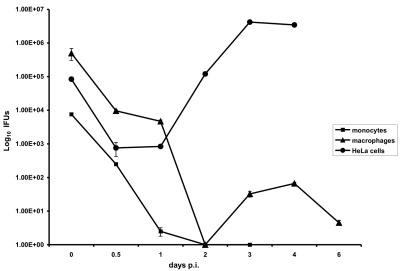

Monocytes obtained from human PBMCs 2 days after isolation and monocyte-derived macrophages obtained from human PBMCs 8 days after isolation were infected with C pneumoniae. A one-step growth curve for the organism was constructed in order to determine the ability of C. pneumoniae to develop and produce infectious progeny in these cells compared to HeLa 229 cells (Fig. 1). In infected monocytes, C. pneumoniae exhibited a dramatic loss in infectivity, which reached zero by 48 h postinfection, and the number of inclusion-forming units was not increased even at 72 h postinfection, demonstrating that in this cell type C. pneumoniae does not complete its developmental cycle. In C. pneumoniae-infected macrophages, the number of infectious units decreased during the initial 15 h postinfection, indicating either that EBs were converted to RBs or the organism was eradicated. A steady decline in the number of recoverable inclusion-forming units was observed up to 48 h postinfection. Infectious progeny EBs were recovered from C. pneumoniae-infected macrophages at 72 h postinfection, and the number peaked at 96 h postinfection; however, the number did not increase even to the level in the infectious inoculum. For comparison, in C. pneumoniae-infected HeLa cells the number of recoverable EBs was much greater than the number in macrophages at 48, 72, and 96 h postinfection (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

One-step growth curve for C. pneumoniae in monocytes, monocyte-derived macrophages, and HeLa cells. In monocytes, the number of inclusion-forming units (IFUs) declined to 0 by 48 h postinfection (p.i.). In monocyte-derived macrophages, there was an initial decline in the number of inclusion-forming units over the first 48 h postinfection and there was an increase in the number of inclusion-forming units by 72 h and 96 h postinfection, indicating that there was differentiation of RBs to EBs. However, the recovery of infectious progeny from macrophages was much lower than the recovery of EBs from infected HeLa cells. The data are the results of a representative experiment with cells from a single donor performed in triplicate.

C. pneumoniae does not form typical inclusions in monocyte-derived macrophages.

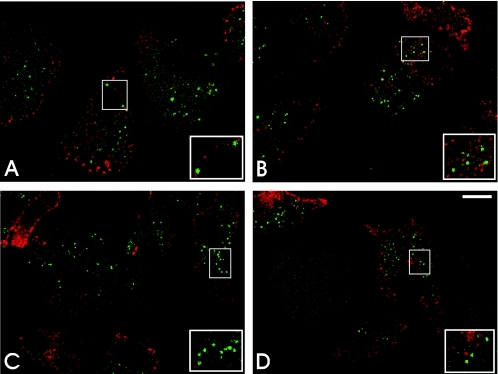

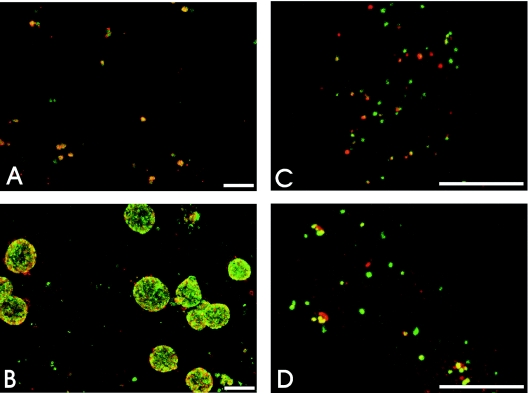

Monocyte-derived macrophages were infected with C. pneumoniae at an MOI of 1, as determined with HeLa cells. Infected cells were then doubly stained at different times postinfection by the indirect immunofluorescence procedure using the anti-mannose receptor monoclonal antibody as a specific marker for human macrophages (46) and an anti-C. pneumoniae rabbit antiserum. The MR was employed as a specific marker for monocyte-derived macrophages. C. pneumoniae attached to and entered MR-positive cells (Fig. 2A), and within these cells the presence of the organisms was detected over a 5-day period after infection (Fig. 2B to D). C. pneumoniae was not detected in most infected macrophages by day 7 after the initial infection (data not shown). Typical mature inclusions of C. pneumoniae were not detected at any time; however, rare small inclusions were occasionally observed (see below).

FIG. 2.

Presence of C. pneumoniae in MR-positive monocyte-derived macrophages. At different times postinfection C. pneumoniae-infected macrophages were fixed and doubly stained for a monocyte/macrophage-specific marker, mannose receptor (red), and with anti-C. pneumoniae rabbit antiserum (green). The confocal micrographs reveal the presence of the organism in MR-positive cells at zero time (A) and at 24 h (B), 72 h (C), and 120 h (D) postinfection with no evidence of replication. The insets are higher magnifications of C. pneumoniae within infected macrophages. Scale bar = 10 μm.

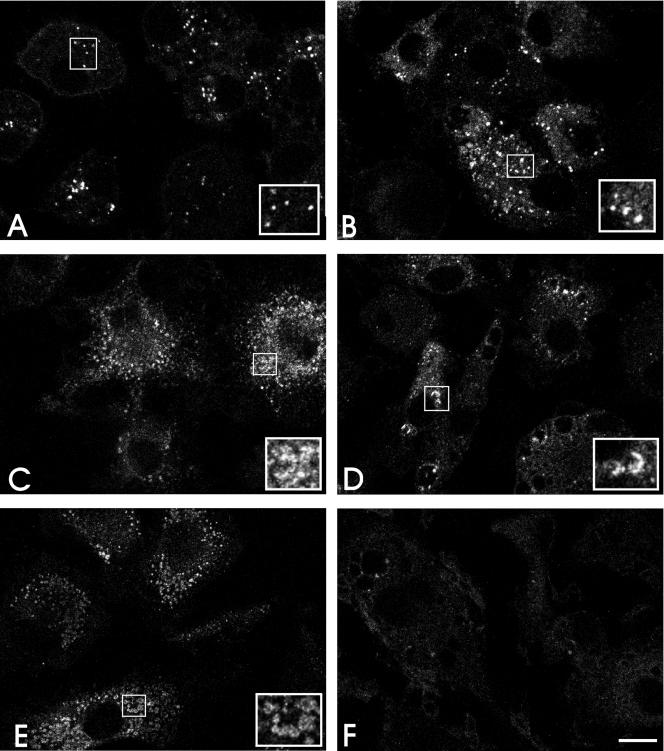

Colocalization of chlamydial antigens in chlamydial inclusions and organisms.

C. pneumoniae-infected HeLa 229 cells, as well as monocyte-derived macrophages, were fixed and doubly stained with anti-C. pneumoniae rabbit antiserum and anti-chlamydial Hsp60 MAb to determine colocalization of chlamydial antigens in the chlamydial inclusions and/or organisms (Fig. 3). In C. pneumoniae-infected HeLa cells at 24 h postinfection, Hsp60 colocalized with antigens recognized by the polyclonal rabbit antiserum in typical chlamydial inclusions (Fig. 3A). However, such colocalization was observed rarely in infected macrophages. In infected macrophages, immunofluorescent staining of Hsp60 was found in structures which, based on their size, more likely represented single chlamydial cells than typical inclusions at 24 h postinfection (Fig. 3B). More commonly, a chlamydial antigen(s) recognized by the rabbit antiserum was detected within punctate vesicles throughout the infected macrophages. By 72 h postinfection mature C. pneumoniae inclusions present in infected HeLa cells displayed immunofluorescent staining of antigens recognized both by anti-Hsp60 and by the polyclonal antibody (Fig. 3C). In infected macrophages C. pneumoniae formed only a few inclusions, which were much smaller than the inclusions observed in HeLa cells (Fig. 3D). These results indicated that the Hsp60 observed in infected macrophages represented exclusively intact and viable C. pneumoniae cells, whereas antigens recognized by only the rabbit antiserum represented intact C. pneumoniae cells, as well as chlamydial antigens remaining in macrophages after degradation of the organisms.

FIG. 3.

(A to D) Colocalization of chlamydial antigens in C. pneumoniae-infected cells. Confocal microscopy of C. pneumoniae inclusions doubly labeled with anti-Hsp60 MAb (red) and anti-C. pneumoniae rabbit antiserum (green) revealed colocalization (yellow) of the antigens to the chlamydial inclusions in HeLa cells at 24 and 72 h postinfection (A and C) and in infected macrophages at 24 and 72 h postinfection (B and D). Only rare inclusions were observed in macrophages (arrows in panel B). (E and F) Colocalization of C. pneumoniae antigens in infected HeLa cells treated with chloramphenicol for 12 h postinfection (F) and in untreated cells (E). Scale bar = 10 μm.

To further investigate and confirm this observation, C. pneumoniae-infected HeLa cells were treated with chloramphenicol (200 μg/ml), an efficient inhibitor of chlamydial protein synthesis (43), for 12 h, and treated and untreated cells were fixed and doubly labeled with anti-C. pneumoniae rabbit antiserum and with anti-Hsp60 MAb. In untreated infected HeLa cells, the antigens clearly costained in the early C. pneumoniae inclusions, demonstrating the presence of viable organisms (Fig. 3E). However, in infected HeLa cells treated with chloramphenicol, chlamydial Hsp60 was not detected on the nonviable C. pneumoniae cells (Fig. 3F).

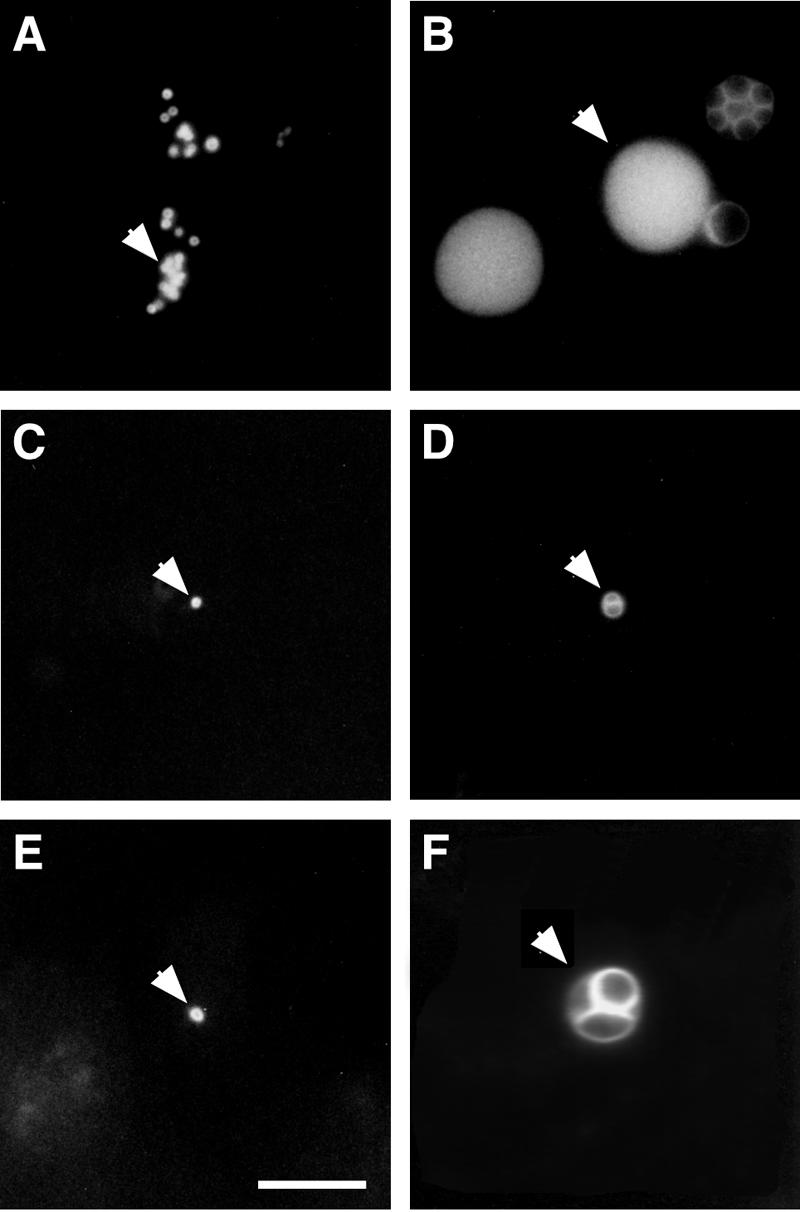

Evidence of C. pneumoniae transcription and translation in infected macrophages.

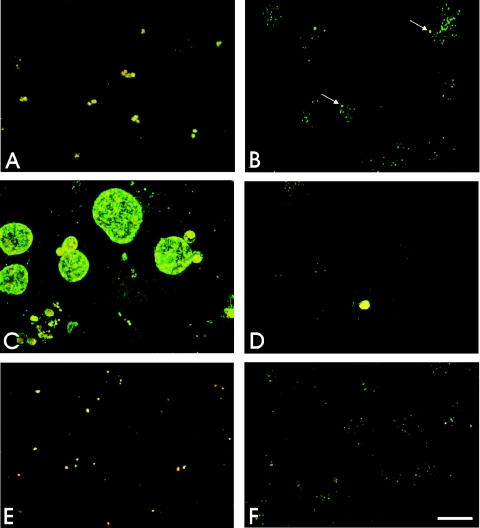

Members of the genus Chlamydia specifically acquire a typical eukaryotic lipid, sphingomyelin, from their hosts (18, 19, 40, 52). A fluorescent vital stain for the Golgi apparatus, C6-NBD-ceramide, is delivered from the Golgi apparatus of an infected host cell to a chlamydial inclusion. C6-NBD-ceramide, like endogenous ceramide, is processed to sphingomyelin or glucosylceramide within the Golgi apparatus prior to transport to the plasma membrane via a vesicle-mediated process (29, 38). Chlamydial uptake of sphingomyelin from the host requires initiation and continuation of chlamydial protein synthesis to maintain fusogenicity with sphingomyelin-containing vesicles (42, 43). The ability of C. pneumoniae to initiate and maintain active protein synthesis in infected macrophages was investigated by examining acquisition of sphingomyelin from the eukaryotic host cell. In C. pneumoniae-infected HeLa cells, the earliest time postinfection at which host sphingomyelin was detected within the chlamydial inclusions was 4 h (52). Monocyte-derived macrophages and HeLa cells were infected with C. pneumoniae at an MOI of 20. HeLa cells were tested in parallel as a positive control. C. pneumoniae-infected cells were labeled with C6-NBD-ceramide, and the delivery of the fluorescent analog from the host to the parasite was monitored (Fig. 4). The fluorescent probe was detected by 5 h postinfection in a large number of early C. pneumoniae inclusions in infected HeLa cells (Fig. 4A). However, very few C6-NBD-ceramide-positive inclusions were found in C. pneumoniae-infected macrophages at the same time (Fig. 4C). By 48 h postinfection in infected HeLa cells, the fluorescent probe was present in typical C. pneumoniae inclusions, which increased in size, indicating that there was active multiplication of RBs in this permissive cell line (Fig. 4B). However, in C. pneumoniae-infected macrophages, the number of small inclusions stained with C6-NBD-ceramide remained low (Fig. 4D) and was approximately the same as the number of inclusions costained with anti-C. pneumoniae and anti-Hsp 60 MAb, as shown above. Neither the number nor the size of the inclusions increased with the time postinfection (Fig. 4E). The latest time after the initial infection of macrophages when the C. pneumoniae inclusions were detected by fluorescent C6-NBD-ceramide was 96 h, but by 120 h postinfection fluorescent staining of the organisms could no longer be detected (data not shown). These results demonstrate that few C. pneumoniae EBs are able to initiate transcription and translation in macrophages to form small inclusions, which generally do not progress to a productive infection. Even in HeLa cells in which C. pneumoniae development was inhibited by the presence of ampicillin, the resultant atypical inclusions containing one or a few aberrantly large RBs took up and were labeled by C6-NBD-ceramide, confirming the ability of the chlamydiae and demonstrating fusogenicity with sphingomyelin-containing vesicles even by aberrant developmental forms (Fig. 4F). C6-NBD-ceramide thus appears to be a useful reagent for the identification of viable chlamydiae even under atypical development conditions.

FIG. 4.

Host sphingomyelin uptake in C. pneumoniae-infected cells. HeLa cells and monocyte-derived macrophages were simultaneously infected with C. pneumoniae at an MOI of 20. The infected cells were labeled with C6-NBD-ceramide and subjected to 4 h of back-exchange. (A to E) Uptake of fluorescent sphingomyelin by C. pneumoniae at 5 h (A) and 48 h (B) postinfection in HeLa cells and at 5 h (C), 48 h (D), and 72 h (E) postinfection in macrophages. (F) C6-NBD-ceramide labeling of C. pneumoniae-infected HeLa cells after 48 h in the presence of 50 μg/ml ampicillin, as previously described (50). The arrows indicate C. pneumoniae inclusions. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Presence of C. pneumoniae in LAMP-2-positive phagosomes.

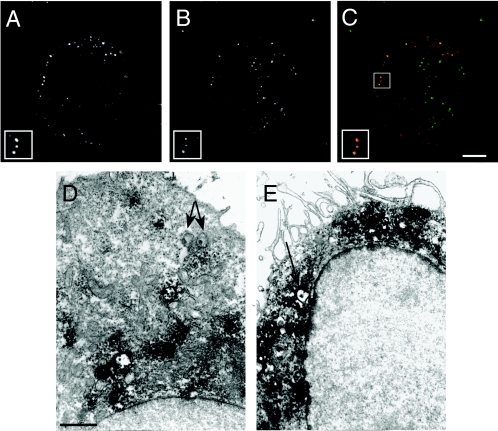

Chlamydial inclusions do not interact with the endocytic or lysosomal pathways (2, 23, 48, 52). However, inhibition of chlamydial transcription and translation ultimately leads to fusion of Chlamydia-containing vesicles with lysosomes (2, 43). To investigate the interaction of C. pneumoniae with the lysosomal pathway in human macrophages, monocyte-derived macrophages were infected with Cell Tracker Green-labeled C. pneumoniae, and at 2 h postinfection the infected cells were fixed and stained with antibody recognizing the lysosomal glycoprotein LAMP-2. As shown in Fig. 5A, B, and C, the majority of the C. pneumoniae EBs colocalized with LAMP-2. The presence of the organism within LAMP-2-positive phagosomes demonstrated that C. pneumoniae was associated with lysosomes in infected macrophages. This observation was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 5D and E). Elementary bodies were frequently observed in LAMP-2-positive vesicles in infected macrophages (Fig. 5E), whereas similar colocalization was not observed in C. pneumoniae-infected HeLa cells (Fig. 5D), in which the organism survived and replicated.

FIG. 5.

Interaction of C. pneumoniae with LAMP-2-positive vesicles. Monocyte-derived macrophages infected with C. pneumoniae were fixed and labeled with anti-LAMP-2 MAb at 2 h postinfection. (A to C) Confocal micrographs revealing colocalization of LAMP-2 with Cell Tracker Green-labeled chlamydiae (A). C. pneumoniae-infected macrophages identifying the organisms (A) and stained for the LAMP-2 marker (B). (C) Composite image showing LAMP-2 (red) and the EBs (green). The insets are higher magnifications of C. pneumoniae colocalizing with LAMP-2-positive vesicles. Scale bar = 10 μm. (D and E) Transmission electron micrographs of C. pneumoniae EBs not colocalizing with LAMP-2-containing vesicles within an infected HeLa cell (D) and colocalizing with LAMP-2-positive vesicles within an infected macrophage (E). The arrows indicate C. pneumoniae EBs. Scale bar = 1 μm.

Dissociation of C. pneumoniae antigens in infected macrophages.

HeLa cells and monocyte-derived macrophages infected with C. pneumoniae were doubly labeled with chlamydial genus-specific anti-LPS MAb and anti-C. pneumoniae polyclonal rabbit antiserum. In infected HeLa cells at 24 h and 72 h postinfection, all chlamydial inclusions colocalized LPS with antigens recognized by the rabbit antiserum (Fig. 6A and B). However, in infected macrophages the colocalization was observed sporadically at both times postinfection (Fig. 6C and D). These results demonstrated that in C. pneumoniae in macrophages there was a gradual dissociation of the surface antigens of the organism and that the majority of the positive staining in infected macrophages probably represented various vesicles containing different surface components of C. pneumoniae. It was also evident that the antigens recognized by the anti-C. pneumoniae polyclonal antibody detected in infected macrophages for several days after the initial infection did not represent chlamydial LPS.

FIG. 6.

Colocalization of chlamydial LPS with other chlamydial antigens in C. pneumoniae-infected cells. C. pneumoniae-infected HeLa cells and monocyte-derived macrophages were stained with anti-chlamydial LPS MAb (red) and anti-C. pneumoniae polyclonal antibody (green). Confocal micrographs revealed colocalization of the antigens in the chlamydial inclusions in infected HeLa cells at 24 and 72 h postinfection (A and B). However, such colocalization was rarely detected in infected macrophages at 24 and 72 h postinfection (C and D), demonstrating that there was dissociation of C. pneumoniae LPS and other antigens of the organism within these cells. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Distribution of chlamydial LPS in C. pneumoniae-infected macrophages.

In mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages infected with heat-killed Chlamydia trachomatis, the microorganism underwent dramatic proteolytic degradation, resulting in spreading of the chlamydial LPS throughout the infected cells shortly after infection (47). Therefore, we investigated whether a similar pattern of chlamydial LPS distribution occurred after infection of monocyte-derived macrophages with live C. pneumoniae (Fig. 7). Indirect immunofluorescent staining with chlamydial genus-specific anti-LPS monoclonal antibody detected intact organisms associating with macrophages immediately after infection (Fig. 7A). At 24 h postinfection the LPS began to dissociate from C. pneumoniae and was observed in what appeared to be clusters of vesicles present throughout the infected macrophages (Fig. 7B, C, and D). By 96 h postinfection, the intensity of fluorescent staining of LPS-positive vesicles had dramatically decreased (Fig. 7E), and the LPS was not detectable in most infected cells by 120 h postinfection, indicating that there was complete degradation or elimination of the antigen (Fig. 7F). These results confirmed that the majority of C. pneumoniae cells infecting macrophages did not survive in these cells and that eradication of the organism by macrophages seemed to be a gradual process requiring up to several days.

FIG. 7.

Distribution of chlamydial LPS in C. pneumoniae-infected monocyte-derived macrophages. C. pneumoniae-infected macrophages were fixed and stained with anti-chlamydial LPS MAb at different times postinfection. Confocal micrographs of immunofluorescent LPS revealed an interaction of C. pneumoniae with macrophages at zero time (A), and gradual disintegration of chlamydial LPS within infected cells was observed at 24 h (B), 48 h (C) 72 h (D), and 96 h (E) postinfection. Chlamydial LPS was not detected in a majority of infected macrophages by 120 h postinfection. (F). Scale bar = 10 μm.

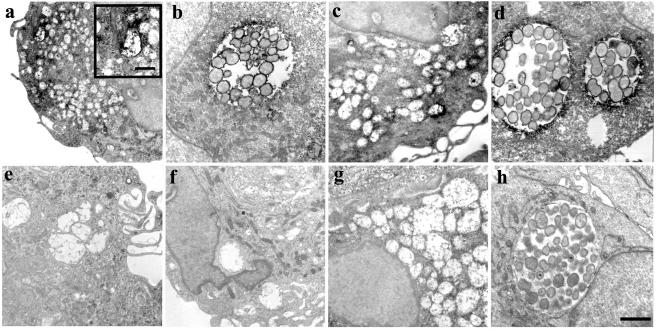

Ultrastructural analysis of C. pneumoniae antigens within infected macrophages.

To determine the localization of chlamydial LPS and other antigens within C. pneumoniae-infected cells on the ultrastructural level, macrophages and HeLa cells were infected at an MOI of ∼100, and at 40 h postinfection the cells were stained with anti-chlamydial LPS MAb or anti-C. pneumoniae rabbit antiserum and processed for transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 8). All antigens tested in infected HeLa cells localized to the typical C. pneumoniae inclusions containing mostly reticulate bodies (Fig. 8b and d). No such inclusions were observed in C. pneumoniae-infected macrophages. The antibodies detected chlamydial antigens within small, vesicle-like structures resembling neither EBs nor RBs (Fig. 8a and c). The specificity of staining demonstrated by electron microscopy was controlled by staining uninfected macrophages with anti-chlamydial LPS (Fig. 8e) and anti-C. pneumoniae rabbit antiserum (Fig. 8g) and by staining C. pneumoniae-infected macrophages (Fig. 8f) and HeLa cells (Fig. 8h) with irrelevant, antirickettsial MAb.

FIG. 8.

Transmission electron micrographs of C. pneumoniae-infected and uninfected macrophages and HeLa cells stained with anti-chlamydial LPS MAb and anti-C. pneumoniae rabbit antiserum at 40 h postinfection. Chlamydial LPS detected throughout an infected macrophage represented undefined structures different from intact chlamydiae (a). Such a staining pattern was absent in an uninfected macrophage (e). In an infected HeLa cell the anti-LPS MAb indicated the organisms within an inclusion (b). Staining with anti-C. pneumoniae rabbit antiserum detected the presence of a chlamydial antigen(s) in an infected macrophage (c), and no staining was present in an uninfected macrophage (g). Positive staining of a typical C. pneumoniae inclusion with the polyclonal antibody was observed in an infected HeLa cell (d). No staining was observed in a C. pneumoniae-infected macrophage (f) and a HeLa cell (h) with irrelevant, antirickettsial MAb. Scale bar = 2 μm. Scale bar in the inset = 0.5 μm.

DISCUSSION

C. pneumoniae has been intensively investigated for possible roles in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Although C. pneumoniae enhances the severity of the disease in animal model systems (13, 28, 31, 32, 35, 41), the precise role and contribution of the organism to the onset and progression of cardiovascular disease remain unknown. C. pneumoniae is believed to enter through the respiratory tract, where the primary infection is established and from which the organism is disseminated. It has been suggested that C. pneumoniae is transmitted from the respiratory system to developing atherosclerotic lesions via circulating PBMCs (33). We employed a combination of infectivity assays, vital stains, and specific antibodies with immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy to analyze the ability of cultured PBMCs to support C. pneumoniae replication. We found that in vitro PBMCs supported only minimal replication of C. pneumoniae, thus supporting the possibility that other mechanisms of dissemination may be more relevant in vivo.

Intracellular pathogens employ sophisticated strategies to successfully invade and survive within their eukaryotic hosts. For many of these pathogens, including Chlamydia spp., avoidance of fusion with and/or destruction by lysosomes is essential. Chlamydiae replicate within vacuoles that do not interact with the endocytic pathway of the host cell (2, 23, 48, 52) but are fusogenic with exocytic vesicular traffic from the Golgi apparatus (18, 23, 40, 52). A significant number of C. pneumoniae cells taken up by macrophages fused with LAMP-2-positive vesicles within 2 h after infection. Rather than typical chlamydial inclusions, numerous phagolysosomes containing the organisms were observed. Consequently, a gradual proteolytic degradation of the bacteria was initiated. We observed dissociation of chlamydial LPS and other antigenic determinants from the organism and their presence within vesicle-like structures throughout the infected macrophages for several days after the initial infection. Similar patterns of proteolytic degradation of chlamydiae by professional phagocytes were reported by Su et al., who inoculated bone marrow-derived macrophages with heat-killed C. trachomatis (47). Due to the persistence of the chlamydial antigen, it is important to emphasize that when professional phagocytes such as macrophages are infected with C. pneumoniae, it is essential to distinguish between a typical inclusion and a phagosome containing chlamydial antigens.

Although the mechanisms of inhibition of C. pneumoniae growth in macrophages were not investigated in detail, the inhibition appeared to be correlated with rapid fusion of lysosomes with the chlamydial phagosome. In permissive cultured cells, vesicles containing endocytosed C. trachomatis EBs are dissociated from the endocytic pathway and are very slow to acquire lysosomal markers, even when EB protein synthesis is inhibited by chloramphenicol (43). It is possible that professional phagocytes mount a more aggressive antichlamydial response to put the phagocytosed EBs into a terminal lysosomal pathway before chlamydial protein synthesis can be initiated to create a protected intracellular niche.

EBs frequently contain mRNA trapped in their nucleoids from previous developmental cycles (5, 12, 44). Therefore, rather than employing reverse transcription-PCR to detect active chlamydial transcription as an indicator of viability, we utilized labeling of C. pneumoniae inclusions in infected macrophages and HeLa cells with a fluorescent vital stain for the Golgi apparatus, C6-NBD-ceramide. All chlamydial species acquire sphingomyelin from their hosts (19, 40, 52). In order to initiate and maintain fusogenicity with sphingomyelin-containing vesicles, chlamydiae must be transcriptionally and translationally active (42, 43). Even persistent forms of C. pneumoniae in HeLa cells induced by treatment with ampicillin incorporate host sphingomyelin into aberrant inclusions. In C. pneumoniae-infected macrophages, only a very low number of the organisms were found to acquire sphingomyelin. In permissive cell types, the ability of chlamydiae to acquire sphingomyelin is an early function detectable by 2 to 6 h postinfection (18, 52). The failure to observe sphingomyelin incorporation suggests that the vast majority of C. pneumoniae EBs in PBMCs did not progress sufficiently into the early developmental cycle to initiate sphingomyelin uptake. This finding is consistent with the observation that EBs are observed within vesicles bearing lysosomal markers soon after infection.

Although circulating monocytes are the most-studied mononuclear phagocytes in humans and culture of these cells is well established, it is necessary to take in account cellular events that occur during incubation of primary monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages in vitro. Monocytes are initially activated by their adherence to a solid substrate; however, many of the activation parameters return to their basal levels after 24 h of culture (14, 21, 22, 36, 45, 49). Adherence and spreading of monocytes to culture dishes induce spontaneous differentiation to macrophages, which involves a number of physical and biochemical changes of the cells (11, 30). The characteristic morphological changes generally observed during conversion of a monocyte to a macrophage include an increase in cell size, as well as development of a higher cytoplasm-to-nucleus ratio (24). Furthermore, a number of receptors are upregulated, and some novel receptors, including the mannose receptor, become expressed (46). It is known that the ability of different C. trachomatis biovars to survive and multiply in primary mononuclear phagocytes depends upon the length of time in culture (53). A significant increase in production of infectious progeny was observed by day 8 after isolation of mononuclear phagocytes (53), a time which corresponds to complete conversion of monocytes to macrophages (4, 37).

We investigated the survival of C. pneumoniae in monocyte-derived macrophages obtained from peripheral blood of healthy donors 8 days after isolation and adherence. Only very small inclusions were observed in monocyte-derived macrophages by 72 h and 96 h postinfection. The number varied between 2 and 10 inclusions per 2 × 105 macrophages, and their presence was detected in MR-positive macrophages, as well as in MR-negative cells (data not shown). These inclusions likely represented mature C. pneumoniae inclusions as modest numbers of infectious progeny were recovered by 72 and 96 h postinfection. In addition, we examined the survival of C. pneumoniae in monocytes obtained from PBMCs cultured for 48 h prior to infection. Thus, the cells were given sufficient time to revert from an activated state to an inactivated state and to express the mannose receptor. C. pneumoniae did not form detectable inclusions in MR-positive monocytes, and proteolytic degradation of the organism was observed rapidly after infection (data not shown). This observation was also confirmed by a one-step growth curve demonstrating that infectious EBs could not be recovered after 48 h postinfection.

We found that the majority of C. pneumoniae cells did not survive within primary monocytes and monocyte derived-macrophages. The organism appeared to enter the lysosomal pathway of the host cell and was gradually degraded. Some C. pneumoniae antigens resisted lysosomal lysis for days after the initial infection, and therefore, identification of chlamydial antigen in these cells did not necessarily indicate that there was an intact organism. Caution should therefore be exercised in evaluating histochemical and immunochemical staining for C. pneumoniae since a vacuolar antigen may not reflect the presence of viable chlamydiae or indicate a productive infection. However, some of the C. pneumoniae cells can survive, multiply, and complete the typical developmental cycle in monocyte-derived macrophages, as determined by a growth curve, although the inclusions are fairly small throughout the entire cycle. Vital staining with C6-NBD-ceramide appears to be a useful technique for demonstrating the presence of viable chlamydiae in cultured cells. Because sphingomyelin uptake is maintained for several hours even after inhibition of chlamydial protein synthesis (42) and because sphingomyelin is incorporated by even aberrant chlamydial developmental forms, C6-NBD-ceramide labeling may even have utility in identifying viable C. pneumoniae in certain clinical specimens.

Acknowledgments

We thank Olivia Steele-Mortimer and Robert Heinzen for critical reviews of the manuscript.

Editor: D. L. Burns

REFERENCES

- 1.Airenne, S., H. M. Surcel, H. Alakarppa, K. Laitinen, J. Paavonen, P. Saikku, and A. Laurila. 1999. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in human monocytes. Infect. Immun. 67:1445-1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Younes, H. M., T. Rudel, and T. F. Meyer. 1999. Characterization and intracellular trafficking pattern of vacuoles containing Chlamydia pneumoniae in human epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 1:237-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anacker, R. L., R. E. Mann, and C. Gonzales. 1987. Reactivity of monoclonal antibodies to Rickettsia rickettsii with spotted fever and typhus group rickettsiae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:167-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andreesen, R., J. Osterholz, K. J. Bross, A. Schulz, G. A. Luckenbach, and G. W. Lohr. 1983. Cytotoxic effector cell function at different stages of human monocyte-macrophage maturation. Cancer Res. 43:5931-5936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belland, R. J., G. Zhong, D. D. Crane, D. Hogan, D. Sturdevant, J. Sharma, W. L. Beatty, and H. D. Caldwell. 2003. Genomic transcriptional profiling of the developmental cycle of Chlamydia trachomatis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:8478-8483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blasi, F., et al. 1999. Chlamydia pneumoniae DNA detection in peripheral blood mononuclear cells is predictive of vascular infection. J. Infect. Dis. 180:2074-2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boleti, H., D. M. Ojcius, and A. Dautry-Varsat. 2000. Fluorescent labelling of intracellular bacteria in living host cells. J. Microbiol. Methods 40:265-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boman, J., et al. 1998. High prevalence of Chlamydia pneumoniae DNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with cardiovascular disease and in middle-aged blood donors. J. Infect. Dis. 178:274-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown, W. J., and M. G. Farquhar. 1989. Immunoperoxidase methods for the localization of antigens in cultured cells and tissue sections by electron microscopy. Methods Cell Biol. 31:553-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell, L. A., C.-C. Kuo, and J. T. Grayston. 1998. Chlamydia pneumoniae and cardiovascular disease. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 4:571-579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dougherty, G. J., and W. H. McBride. 1989. Monocyte differentiation in vitro, p. 49-58. In M. Zembala and G. L. Asherson (ed.), Human monocytes. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 12.Douglas, A. L., and T. P. Hatch. 2000. Expression of the transcripts of the sigma factors and putative sigma factor regulators of Chlamydia trachomatis L2. Gene 247:209-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fong, I. W., B. Chiu, E. Viira, M. W. Fong, D. Jang, and J. Mahony. 1997. Rabbit model for Chlamydia pneumoniae infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:48-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuhlbrigge, R. C., D. D. Chaplin, J. M. Kiely, and E. R. Unanue. 1987. Regulation of interleukin 1 gene expression by adherence and lipopolysaccharide. J. Immunol. 138:3799-3802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaydos, C. A., J. T. Summersgill, N. N. Sahney, J. A. Ramirez, and T. C. Quinn. 1996. Replication of Chlamydia pneumoniae in vitro in human macrophages, endothelial cells, and aortic artery smooth muscle cells. Infect. Immun. 64:1614-1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gieffers, J., H. Fullgraf, J. Jahn, M. Klinger, K. Dalhoff, H. A. Katus, W. Solbach, and M. Maass. 2001. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in circulating human monocytes is refractory to antibiotic treatment. Circulation 103:351-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Godzik, K. L., E. R. O'Brien, S. K. Wang, and C. C. Kuo. 1995. In vitro susceptibility of human vascular wall cells to infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2411-2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hackstadt, T., D. D. Rockey, R. A. Heinzen, and M. A. Scidmore. 1996. Chlamydia trachomatis interrupts an exocytic pathway to acquire endogenously synthesized sphingomyelin in transit from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane. EMBO J. 15:964-977. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hackstadt, T., M. A. Scidmore, and D. D. Rockey. 1995. Lipid metabolism in Chlamydia trachomatis-infected cells: directed trafficking of Golgi-derived sphingolipids to the chlamydial inclusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:4877-4881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haranaga, S., H. Yamaguchi, G. F. Leparc, H. Friedman, and Y. Yamamoto. 2001. Detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae antigen in PBMNCs of healthy blood donors. Transfusion 41:1114-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haskill, S., A. A. Beg, S. M. Tompkins, J. S. Morris, A. D. Yurochko, A. Sampson-Johannes, K. Mondal, P. Ralph, and A. S. Baldwin, Jr. 1991. Characterization of an immediate-early gene induced in adherent monocytes that encodes I kappa B-like activity. Cell 65:1281-1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haskill, S., C. Johnson, D. Eierman, S. Becker, and K. Warren. 1988. Adherence induces selective mRNA expression of monocyte mediators and proto-oncogenes. J. Immunol. 140:1690-1694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinzen, R. A., M. A. Scidmore, D. D. Rockey, and T. Hackstadt. 1996. Differential interaction with endocytic and exocytic pathways distinguish parasitophorous vacuoles of Coxiella burnetii and Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 64:796-809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan, G., and G. Gaudernack. 1982. In vitro differentiation of human monocytes. Differences in monocyte phenotypes induced by cultivation on glass or on collagen. J. Exp. Med. 156:1101-1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaukoranta-Tolvanen, S. S., A. M. Teppo, K. Laitinen, P. Saikku, K. Linnavuori, and M. Leinonen. 1996. Growth of Chlamydia pneumoniae in cultured human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and induction of a cytokine response. Microb. Pathog. 21:215-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi, S. D., J. M. Voyich, C. L. Buhl, R. M. Stahl, and F. R. DeLeo. 2002. Global changes in gene expression by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes during receptor-mediated phagocytosis: cell fate is regulated at the level of gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:6901-6906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuo, C.-C., L. A. Jackson, L. A. Campbell, and J. T. Grayston. 1995. Chlamydia pneumoniae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:451-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laitinen, K., A. Laurila, L. Pyhala, M. Leinonen, and P. Saikku. 1997. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection induces inflammatory changes in the aortas of rabbits. Infect. Immun. 65:4832-4835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipsky, N. G., and R. E. Pagano. 1985. A vital stain for the Golgi apparatus. Science 228:745-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maoz, H., A. Polliack, V. Barak, S. Yatziv, S. Biran, H. Giloh, and A. J. Treves. 1986. Parameters affecting the in vitro maturation of human monocytes to macrophages. Int. J. Cell Cloning 4:167-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moazed, T. C., L. A. Campbell, M. E. Rosenfeld, J. T. Grayston, and C. C. Kuo. 1999. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection accelerates the progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J. Infect. Dis. 180:238-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moazed, T. C., C. Kuo, J. T. Grayston, and L. A. Campbell. 1997. Murine models of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and atherosclerosis. J. Infect. Dis. 175:883-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moazed, T. C., C.-C. Kuo, T. J. Grayston, and L. A. Campbell. 1998. Evidence of systematic dissemination of Chlamydia pneumoniae via macrophages in the mouse. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1322-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moulder, J. W. 1991. Interaction of chlamydiae and host cells in vitro. Microbiol. Rev. 55:143-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muhlestein, J. B., J. L. Anderson, and E. H. Hammond. 1998. Infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae accelerates the development of atherosclerosis and treatment with azithromycin prevents it in a rabbit model. Circulation 97:663-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Navarro, S., N. Debili, J. F. Bernaudin, W. Vainchenker, and J. Doly. 1989. Regulation of the expression of IL-6 in human monocytes. J. Immunol. 142:4339-4345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman, S. L., R. A. Musson, and P. M. Henson. 1980. Development of functional complement receptors during in vitro maturation of human monocytes into macrophages. J. Immunol. 125:2236-2244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pagano, R. E. 1990. Lipid traffic in eukaryotic cells: mechanisms for intracellular transport and organelle-specific enrichment of lipids. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2:652-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pagano, R. E., and O. C. Martin. 1988. A series of flourescent N-acylsphingosines: synthesis, physical properties, and studies in cultured cells. Biochemistry 27:4439-4445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rockey, D. D., E. R. Fischer, and T. Hackstadt. 1996. Temporal analysis of the developing Chlamydia psittaci inclusion using fluorescent and electron microscopy. Infect. Immun. 64:4269-4278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rothstein, N. M., T. C. Quinn, C. A. Madico, C. A. Gaydos, and C. J. Lowenstein. 2001. Effect of azithromycin on murine atherosclerosis exacerbated by Chlamydia pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 183:232-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scidmore, M. A., E. R. Fischer, and T. Hackstadt. 2003. Restricted fusion of Chlamydia trachomatis vesicles with endocytic compartments during the initial stages of infection. Infect. Immun. 71:973-984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scidmore, M. A., D. D. Rockey, E. R. Fischer, R. A. Heinzen, and T. Hackstadt. 1996. Vesicular interactions of the Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion are determined by chlamydial early protein synthesis rather than route of entry. Infect. Immun. 64:5366-5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shaw, E. I., C. A. Dooley, E. R. Fischer, M. A. Scidmore, K. A. Fields, and T. Hackstadt. 2000. Three temporal classes of gene expression during the Chlamydia trachomatis developmental cycle. Mol. Microbiol. 37:913-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sporn, S. A., D. F. Eierman, C. E. Johnson, J. Morris, G. Martin, M. Ladner, and S. Haskill. 1990. Monocyte adherence results in selective induction of novel genes sharing homology with mediators of inflammation and tissue repair. J. Immunol. 144:4434-4441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stahl, P. 1992. The mannose receptor and other macrophage lectins. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 4:49-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Su, H., and H. D. Caldwell. 1995. The kinetics of chlamydial antigen processing and presentation to T cells by paraformaldehyde-fixed murine bone marrow-derived macrophages. Infect. Immun. 63:946-953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taraska, T., D. M. Ward, R. S. Ajioka, P. B. Wyrick, S. R. Davis-Kaplan, C. H. Davis, and J. Kaplan. 1996. The late chlamydial inclusion membrane is not derived from the endocytic pathway and is relatively deficient in host proteins. Infect. Immun. 64:3713-3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thorens, B., J. J. Mermod, and P. Vassalli. 1987. Phagocytosis and inflammatory stimuli induce GM-CSF mRNA in macrophages through posttranscriptional regulation. Cell 48:671-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolf, K., E. Fischer, and T. Hackstadt. 2000. Ultrastructural analysis of developmental events in Chlamydia pneumoniae-infected cells. Infect. Immun. 68:2379-2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolf, K., E. Fischer, D. Mead, G. Zhong, R. Peeling, B. Whitmire, and H. D. Caldwell. 2001. Chlamydia pneumoniae major outer protein is a surface-exposed antigen that elicits antibody primarily directed against conformation-dependent determinants. Infect. Immun. 69:3082-3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolf, K., and T. Hackstadt. 2001. Sphingomyelin trafficking in Chlamydia pneumoniae-infected cells. Cell. Microbiol. 3:145-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yong, E. C., E. Y. Chi, and C. C. Kuo. 1987. Differential antimicrobial activity of human mononuclear phagocytes against the human biovars of Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Immunol. 139:1297-1302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yuan, Y., K. Lyng, Y. X. Zhang, D. D. Rockey, and R. P. Morrison. 1992. Monoclonal antibodies define genus-specific, species-specific, and cross-reactive epitopes of the chlamydial 60-kilodalton heat shock protein (hsp60): specific immunodetection and purification of chlamydial hsp60. Infect. Immun. 60:2288-2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]