Abstract

A culture method utilizing quantitative plating on antibiotic-containing media has been proposed as a technique for the detection of tobramycin-resistant organisms that is more sensitive than standard methods. Typical sputum culture methods quantitate the relative amounts of each distinct morphotype, followed by antibiotic susceptibility testing of a single colony of each morphotype. Sputum specimens from 240 cystic fibrosis patients were homogenized, serially diluted, and processed in parallel by the standard method (MacConkey agar and OF basal medium with agar, polymyxin, bacitracin, and lactose) and by plating on antibiotic-containing media (MacConkey agar with tobramycin added at 25 μg/ml [MAC-25] and 100 μg/ml [MAC-100]). MICs of tobramycin were determined for all Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates by broth microdilution. Growth of P. aeruginosa on MAC-25 was considered to be equivalent to a tobramycin MIC of ≥16 μg/ml, and growth on MAC-100 was considered to be equivalent to a tobramycin MIC of ≥128 μg/ml. Analysis of method-specific detection rates showed that tobramycin-containing medium was more sensitive than the standard method for the detection of tobramycin-resistant P. aeruginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and Achromobacter xylosoxidans but was less sensitive for the detection of Burkholderia cepacia than the standard method. When MICs for P. aeruginosa that grew on tobramycin-containing medium were tested by broth microdilution, the MICs for 28 of 121 strains (23%) growing on MAC-25 and 22 of 56 strains (39%) growing on MAC-100 were MICs <16 and <128 μg/ml, respectively. Addition of a tobramycin-containing MacConkey plate to the routine media for sputum culture may provide additional, clinically relevant microbiologic data.

Patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) typically harbor multiple morphologically distinct strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in their sputum. These morphotypes contribute in different degrees to the total sputum density of P. aeruginosa, and each may have a different level of antibiotic susceptibility. Typical CF sputum culture methods quantitate the relative amounts of each distinct morphotype, followed by antibiotic susceptibility testing of a pure culture of each morphotype. This methodology assumes that the MIC result for a single clone accurately represents the susceptibility of the entire population of that morphotype and that all morphotypes will be represented even if present in small numbers relative to the predominant morphotype. It is possible that this methodology underrepresents the number of antibiotic-resistant P. aeruginosa clones within the sputum sample.

Following the reported efficacy of inhaled tobramycin in CF patients (3, 14) the question of increasing tobramycin resistance among sputum isolates of P. aeruginosa and other gram-negative organisms gained importance. If antibiotic selection occurs related to the chronic use of inhaled drug, the ability to detect even small numbers of tobramycin-resistant isolates in sputum may be significant. As noted above, the methods currently in use may underrepresent tobramycin resistance. Thus, development of a technique that would sample the resistance phenotype of all of the organisms present in a given sputum sample was proposed. A previous study by Maduri-Traczewski et al. utilized a culture method in which each P. aeruginosa clone was tested individually for susceptibility, by directly plating sputum to antibiotic-containing medium (12). They concluded that utilization of antibiotic-containing primary media accurately and promptly detected antibiotic-resistant organisms compared to standard quantitative cultures from which colonies were selected for subsequent MIC testing. The current study specifically examines the utility of tobramycin-containing primary media for the detection of tobramycin-resistant organisms from the sputum of CF patients.

(This work was presented in part at the 14th Annual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference, 9 to 12 November 2000, Baltimore, Md.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimen collection and processing.

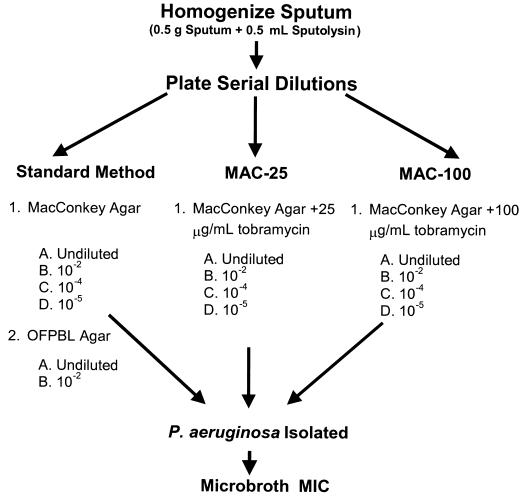

Sputum specimens were collected from 240 CF patients from seven CF clinics across the United States during 1999. All participants and their families gave informed consent in accordance with experimental guidelines of the US Department of Health and Human Services and the institutions at which the study was performed. To be eligible for the study, patients were required to be able to produce sputum, to have a history of P. aeruginosa in the lower respiratory tract, and, if they were currently receiving aerosolized antibiotics, the specimen had to be collected at least 12 h after their last dose. Sputum was processed as described in Fig. 1. Briefly, each sputum sample was homogenized using dithiothreitol (Sputolysin; Calbiochem-Behring, La Jolla, Calif.) and serially diluted in sterile physiologic saline, and 0.1-ml aliquots of each dilution were plated to MacConkey agar (MAC), MacConkey agar with tobramycin at 25 μg/ml (MAC-25) and 100 μg/ml (MAC-100), and a selective agar for Burkholderia cepacia (OFPBL [19]) (media were purchased from Remel, Lenexa, Kans.). All plates were incubated at 37°C for at least 72 h. Quantitation of all gram-negative bacilli was performed on all medium types. Each morphologically distinct isolate (texture [mucoid, rough versus smooth], colony size, color) of P. aeruginosa was enumerated separately and subcultured for MIC determination. Broth microdilution tobramycin (0.12 to 512 μg/ml) susceptibility testing was performed on all gram-negative bacilli using a semiautomated system (Sensititre; Trek Diagnostics, Westlake, Ohio) and manual reading of end points following 18 to 24 h of incubation (3). Organisms were identified by standard techniques, including the use of a biochemical panel for the identification of non-P. aeruginosa, gram-negative, non-lactose fermenters (16).

FIG. 1.

Diagram of the processing of sputum from 240 patients at seven CF centers in the United States. All samples were sent to a single laboratory (Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center, Seattle, Wash.), where they were processed by both the standard method and the antibiotic-containing-medium method (MAC-25 and MAC-100). Tobramycin MICs were determined for all morphologically distinct P. aeruginosa isolates and for all other non-lactose-fermenting gram-negative bacilli.

Statistical analysis.

Preliminary range finding experiments using strains of P. aeruginosa with known tobramycin MICs showed that MacConkey agar containing tobramycin at 25 μg/ml would inhibit the growth of 93% of P. aeruginosa isolates for which the tobramycin MICs were <16 μg/ml and support the growth of more than 75% of P. aeruginosa isolates for which the tobramycin MICs were ≥16 μg/ml. Similarly, MAC-100 would suppress the growth of most P. aeruginosa isolates for which the tobramycin MICs are <128 μg/ml while supporting the growth of most P. aeruginosa isolates for which the tobramycin MICs are ≥128 μg/ml. Thus, growth of P. aeruginosa on MAC-25 was considered to be equivalent to a tobramycin MIC of ≥16 μg/ml, and growth of P. aeruginosa on MAC-100 was considered to be equivalent to a tobramycin MIC of ≥128 μg/ml. The method-specific detection rate for each method (standard method [MAC and OFPBL], MAC-25, and MAC-100) was calculated by dividing the number of patients with a given organism detected by that method by the number of patients with that organism detected by all methods.

The percentage of patients whose sputum grew tobramycin-resistant P. aeruginosa detected by the standard method (broth microdilution MIC, ≥16 μg/ml) was compared with the percentage of patients whose sputum grew P. aeruginosa on MAC-25 by using a two-sided, one-sample McNemar test.

RESULST

Patient population.

The study included an equal number of male and female patients; the mean age was 20.4 years. Overall, 59.6% of patients received aminoglycosides by either the intravenous or aerosol route within the 8 weeks prior to providing sputum for this study (Table 1). Two hundred eighteen of 240 patients had P. aeruginosa detected from their sputum on MacConkey agar without added tobramycin. Mean P. aeruginosa density in sputum for these patients was 7.1 log10 CFU/g (standard deviation, 1.5 log10 CFU/g).

TABLE 1.

Summary of demographic characteristics and aminoglycoside antibiotic use in this study

| Parameter (unit) | Value |

|---|---|

| Gender [no. (%)] | |

| Female | 121 (50.4) |

| Male | 119 (49.6) |

| Age (yr) | |

| Mean (SD) | 20.4 (8.8) |

| Range | 6–57 |

| Sputum density of P. aeruginosa (log10 CFU/g)a | |

| Mean (SD) | 7.1 (1.5) |

| Range | 1.3–9.7 |

| Aminoglycoside use in the previous 8 weeks [no. (%)] | |

| Overallb | 143 (59.6) |

| Intravenous | 71 (29.6) |

| Tobramycin solution for inhalation | 104 (43.3) |

| Other aerosol aminoglycosides | 21 (8.8) |

Of a total of 240 patients, 218 had P. aeruginosa detected. Data shown are for these 218 patients.

Some patients received both intravenous and aerosolized aminoglycosides; thus, the overall number is less than the sum of intravenous, tobramycin solution for inhalation, and other aerosol aminoglycosides.

Detection of tobramycin-resistant organisms.

By all methods, 124 of 240 (52%) patients had a tobramycin-resistant P. aeruginosa detected. However, using standard methodology alone, only 58 of 240 (24%) had P. aeruginosa isolates for which the MIC was ≥16 μg/ml. For the 58 patients with resistant P. aeruginosa detected on MAC, the resistant colonies represented, on average, 70% of the total CFU count (median, 97%; range, 0.2 to 100%). Tobramycin-containing medium was much more sensitive for the detection of resistant P. aeruginosa at both the 16-μg/ml level (MAC-25 versus MAC, 98 versus 47%) and the 128-μg/ml levels (MAC-100 versus MAC, 100 versus 21%) (Table 2). Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Achromobacter xylosoxidans were also detected more frequently on tobramycin-containing media. Conversely, B. cepacia was detected more frequently by the standard method (MAC or OFPBL) than on either MAC-25 or MAC-100.

TABLE 2.

Method-specific detection ratesa(n = 240)

| Organism | Total no. detected | No. (%) of organisms detected by method

|

Pb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | MAC-25 | MAC-100 | |||

| P. aeruginosa Resistant (MIC ≥ 16 μg/ml) | 124 | 58 (47) | 121 (98)c | NA | 0.001 |

| High level resistant (MIC ≥ 128 μg/ml) | 56 | 12 (21) | NA | 56 (100)d | |

| B. cepacia | 8 | 8 (100) | 4 (50) | 1 (12) | |

| S. maltophilia | 49 | 30 (61) | 41 (84) | 41 (84) | |

| A. xylosoxidans | 30 | 20 (67) | 25 (83) | 21 (70) | |

Calculated as the number detected by a method/the total number detected.

Two-sample, one-sided McNemar test.

Includes isolates from all patients from whom P. aeruginosa was isolated on MAC-25, including the 28 isolates that had confirmatory tobramycin MICs of <16 μg/ml.

Includes isolates from all patients from whom P. aeruginosa was isolated on MAC-100, including the 22 isolates that had confirmatory tobramycin MICs of <128 μg/ml.

Density of tobramycin-resistant P. aeruginosa.

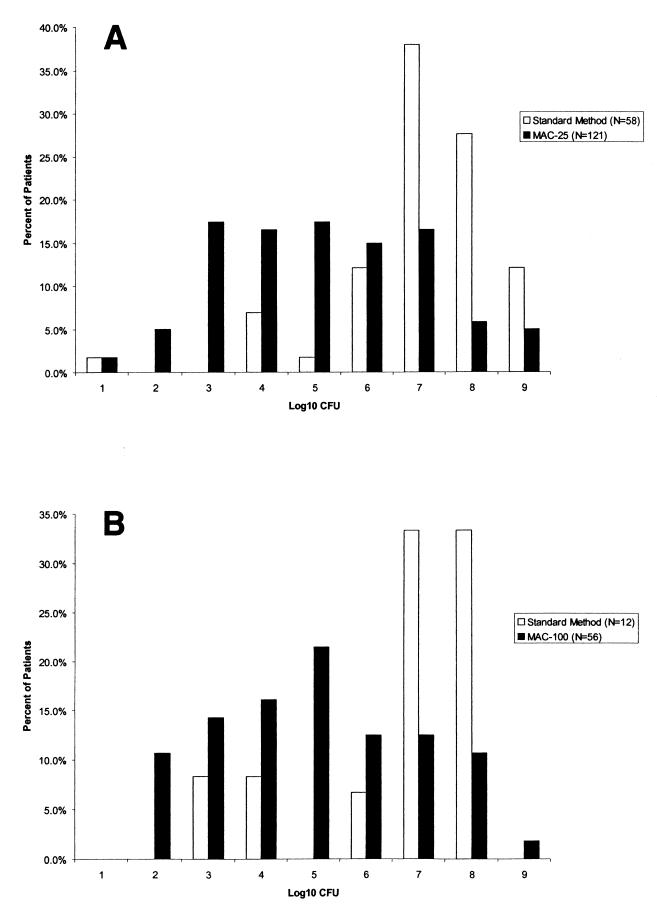

Seventy of 121 (58%) patients with resistant P. aeruginosa detected on the MAC-25 plates had colony counts of less than 106 CFU/g of sputum compared with 5 of the 58 patients (9%) with resistant P. aeruginosa (tobramycin MIC, ≥16 μg/ml) detected by the standard method (Fig. 2A). Colony counts of resistant P. aeruginosa were higher when it was detected on both MAC and MAC-25 (38 of 55 patients [69%] had counts of >106 CFU/g) than when it was detected on MAC-25 only (13 of 69 patients [19%]). Similar findings were noted for the MAC-100 plates (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

(A) Density of resistant P. aeruginosa detected by the standard method and on MAC-25 (defined as tobramycin MIC of ≥16 μg/ml by broth microdilution for standard method and as growth on plate for MAC-25). (B) Density of high-level-resistant P. aeruginosa detected by the standard method and by MAC-100 (defined as tobramycin MIC of ≥128 μg/ml by broth microdilution for standard method and as growth on plate for MAC-100).

False-positive rates on antibiotic-containing media.

P. aeruginosa that grew on either MAC-25 or MAC-100 had confirmatory broth microdilution susceptibility testing performed. On MAC-25, 93 of 121 isolates had confirmatory tobramycin MICs of ≥16 μg/ml, and on MAC-100, 34 of 56 isolates had confirmatory tobramycin MICs of ≥128 μg/ml, for false-positive rates of 23 and 39%, respectively.

Laboratory notes.

There were several notable findings regarding the techniques used for this study. First, drug-containing media (MAC-25 and MAC-100) required longer incubation (at least 72 h) for organisms to grow adequately for identification and quantitation. Second, colonies were much smaller and more difficult to differentiate on the drug-containing media. Third, on plates where undiluted sputum was plated, instances occurred where the mucus in the sputum appeared to protect the organisms from the antibiotic in the plate, resulting in false-positive growth.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that the addition of tobramycin to primary plating media increases the sensitivity for detection of tobramycin-resistant P. aeruginosa from CF sputum. Resistance to tobramycin was much higher in this group of patients than would be expected. Fifty-two percent of patients had a P. aeruginosa isolate with a tobramycin MIC of ≥16 μg/ml (as detected by either method) in the current study, compared with the 13% of patients observed from a similar CF population at baseline in the inhaled-tobramycin clinical trials (3). This high number may reflect the fact that 59.6% of patients had received either intravenous or inhaled aminoglycosides within 8 weeks of providing a sputum sample for the study. However, when only the data from the standard method was considered, 24% of patients had P. aeruginosa isolates for which the tobramycin MICs were ≥16 μg/ml. This number is comparable to the 23% of patients reported to have tobramycin-resistant P. aeruginosa following 6 months of inhaled treatment with tobramycin (3).

CF patients typically harbor multiple phenotypically distinct P. aeruginosa organisms, and these organisms frequently have differing antibiotic susceptibility patterns (3, 7, 15, 18). In this study, the relative density of the resistant P. aeruginosa compared to the total colony count of P. aeruginosa was very small for many of the patients from whom tobramycin-resistant P. aeruginosa was isolated. The clinical significance of small numbers of slowly growing tobramycin-resistant P. aeruginosa is unknown. Several published studies of antibiotic treatment for acute exacerbation in CF patients have shown that patients with organisms classified as resistant to the antibiotics they were given responded to treatment as well as those patients with organisms that were classified as susceptible (13, 17; R. Davey, D. Peckham, C. Etherington, and S. Conway. Abstr. 23rd Eur. Cystic Fibrosis Conv., abstr. 409, 2000). This phenomenon is likely the result of multiple factors. First, both susceptible and resistant populations of organisms are present within the lungs of CF patients (18). Second, most aminoglycoside-resistant P. aeruginosa strains from CF patients lack aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes, instead falling into a resistance type termed “impermeability” (11). There is some in vitro evidence that mutants within the impermeability class often show impaired growth in vitro and reduced virulence in animal models (2, 5, 9), suggesting that such strains may be at a competitive disadvantage in the human lung. Finally, antibiotics have been shown to inhibit virulence factors at concentrations below the MIC (4, 6, 8, 10).

There were some patients who would have falsely been reported to have tobramycin-resistant P. aeruginosa had only the results from the tobramycin-containing media been available. These false positives may have been the result of adaptive or transient resistance reverting to susceptibility after a single pass on drug-free media, since a 24 h subculture to blood agar was always performed prior to preparation of the inoculum suspension for the confirmatory broth microdilution MIC test. The phenomenon of adaptive resistance to tobramycin in P. aeruginosa from CF lung infections was reported previously by Barclay et al. (1). Alternatively, when sputum was plated directly on the antibiotic-containing medium, the mucus may have protected the organisms from the antibiotic in the plate, allowing them to grow.

This study focused solely on tobramycin resistance. The previous study by Maduri-Traczewski et al. found that primary culture plates containing ticarcillin and azlocillin increased the sensitivity for detection of resistance to these antibiotics as well (12). Direct susceptibility testing on media containing multiple antibiotics has also been used as a rapid screening test to test for synergy in CF patients; lower counts on drug-containing media compared with non-drug-containing media were considered an indication of synergy (J. Caracciolo, S. Riddell, S. Miller, A. Kerr, and P. Gilligan, Abstr. 96th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 1996, abstr. C-309, 1996). It is likely that many CF patients harbor small subpopulations of P. aeruginosa that are resistant to many of the antibiotics that are routinely and repeatedly used for treatment.

Before a decision to add antibiotic-containing plates to the primary plating is made, the costs in both material and technical time should be carefully weighed against the possible benefit of increased detection of resistant organisms. Currently tobramycin-containing MacConkey agar is not available commercially, so plates must either be prepared in-house or be specially ordered. Importantly, because B. cepacia was not detected as well on the tobramycin-containing media and given the significance of this pathogen in the CF patient population, the need to plate to a B. cepacia selective agar would not be obviated by the addition of tobramycin-containing MacConkey agar. In addition, the longer incubation time required for growth on the tobramycin-containing plates and the small, difficult-to-differentiate colonies would increase laboratory technologist time for reading each culture. Finally, because of the false-positive results observed with directly plated sputum, dilution of the sputum in saline may be required prior to plating.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Chiron Corporation, Seattle, Wash.

We thank the following principal investigators (PI) and study coordinators for their support of this study: H. Eigen (PI), M. Blagburn, and D. Terrill, Indiana University and Medical Center; R. Anbarm (PI), D. Lindner, and L. Grabowski, SUNY Health Science Center; S. Nasr (PI) and E. Sakmar, University of Michigan; C. Ren (PI) and L. Maffia, University Hospital, Children’s Medical Center at Stonybrook; R. Gibson (PI), S. McNamara, and P. Joy, Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center, Seattle, Wash.; P. Hiatt (PI), L. Morris, and D. Treece, Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital; M. McCarty (PI) and D. Harrington, Deaconess Medical Center, CF Clinic, Spokane, Wash. Most importantly, we thank the patients who volunteered to participate in the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barclay, M. L., E. J. Begg, S. T. Chambers, P. E. Thornley, P. K. Pattemore, and K. Grimwood. 1996. Adaptive resistance to tobramycin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection in cystic fibrosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 37:1155–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryan, L. E., A. J. Godfrey, and T. Schollardt. 1985. Virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains with mechanisms of microbial persistence for β-lactam and aminoglycoside antibiotics in a mouse infection model. Can. J. Microbiol. 31:377–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns, J. L., J. M. Van Dalfsen, R. M. Shawar, K. L. Otto, R. L. Garber, J. M. Quan, A. B. Montgomery, G. M. Albers, B. W. Ramsey, and A. L. Smith. 1999. Effect of chronic intermittent administration of inhaled tobramycin on respiratory microbial flora in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 179:1190–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geers, T. A., and N. R. Baker. 1987. The effect of sublethal concentrations of aminoglycosides on adherence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to hamster tracheal epithelium. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 19:561–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerber, A. U., and W. A. Craig. 1982. Aminoglycoside-selected subpopulations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: characterization and virulence in normal and leukopenic mice. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 100:671–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilligan, P. H. 1991. Microbiology of airway disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:35–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Govan, J. R. W., C. Doherty, and S. Glass. 1987. Rational parameters for antibiotic therapy in patients with cystic fibrosis. Infection 15:300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Govan, J. R. W., D. W. Martin, and V. P. Deretic. 1992. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and cystic fibrosis: the role of mutations in muc loci. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 79:323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Govan, J. R. W., and S. Glass. 1990. The microbiology and therapy of cystic fibrosis lung infections. Rev. Med. Microbiol. 1:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grimwood, K., M. To, H. R. Rabin, and D. E. Woods. 1989. Inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme expression by subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacLeod, D. L., L. E. Nelson, R. M. Shawar, B. B. Lin, L. G. Lockwood, J. E. Dirks, G. H. Miller, J. L. Burns, and R. L. Garber. 2000. Aminoglycoside-resistance mechanisms for cystic fibrosis Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates are unchanged by long-term, intermittent, inhaled tobramycin treatment. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1180–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maduri-Traczewski, M., C. L’Heureux, L. Escalona, A. Macone, and D. Goldmann. 1986. Facilitated detection of antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas in cystic fibrosis sputum using homogenized specimens and antibiotic-containing media. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 5:299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLaughlin, F. J., W. J. Matthews, Jr., D. J. Strieder, B. Sullivan, A. Taneja, P. Murphy, and D. A. Goldmann. 1983. Clinical and bacteriological responses to three antibiotic regimens for acute exacerbations of cystic fibrosis: ticarcillin-tobramycin, azlocillin-tobramycin, and azlocillin-placebo. J. Infect. Dis. 147:559–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramsey, B. W., M. S. Pepe, J. M. Quan, K. L. Otto, A. B. Montgomery, J. Williams-Warren, M. Vasiljev-K, D. Borowitz, C. M. Bowman, B. C. Marshall, S. Marshall, and A. L. Smith. 1999. Intermittent administration of inhaled tobramycin in patients with cystic fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 340:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seale, T. W., H. Thirkill, M. Tarpay, M. Flux, and O. M. Rennert. Serotypes and antibiotic susceptibilities of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from single sputa of cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 9:72–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Shigei, J. 1992. Test methods used in the identification of commonly isolated aerobic gram-negative bacteria, p. 1.19.1-1.19.110. In H. D. Isenberg (ed.), Clinical microbiology procedures handbook, vol. 1. American Society for Microbiology, Washington D.C.

- 17.Smith, A. L., C. Doershuk, D. Goldmann, E. Gore, B. Hilman, M. Marks, R. Moss, B. Ramsey, G. Redding, T. Rubio, J. Williams-Warren, R. Wilmott, H. D. Wilson, and R. Yogev. 1999. Comparison of a β-lactam alone versus β-lactam and an aminoglycoside for pulmonary exacerbation in cystic fibrosis. J. Pediatr. 134:413–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomassen, M. J., C. A. Demko, B. Boxerbaum, R. C. Stern, and P. J. Kuchenbrod. 1979. Multiple isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with differing antimicrobial susceptibility patterns from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 140:873–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welch, D. F., M. J. Muszynski, C. H. Pai, M. J. Marcon, M. M. Hribar, P. H. Gilligan, J. M. Matsen, P. A. Ahlin, B. C. Hilman, S. A. Chartrand. 1987. Selective and differential medium for recovery of Pseudomonas cepacia from the respiratory tracts of patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:1730–1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]