Abstract

Inter-alpha-inhibitor protein (IαIp) functions as an endogenous serine protease inhibitor in human plasma, and IαIp levels diminish rapidly during acute inflammatory states. One potential target for IαIp is furin, a cell-associated serine endopeptidase essential for the activation of protective antigen and the formation of anthrax lethal toxin (LT). IαIp blocks furin activity in vitro and provides significant protection against cytotoxicity for murine peritoneal macrophages exposed to up to 500 ng/ml LT. A monoclonal antibody (MAb), 69.31, that specifically blocks the enzymatic activity of IαIp eliminates its protective effect against LT-induced cytotoxicity. IαIp (30 mg/kg of body weight) administered to BALB/c mice 1 hour prior to an intravenous LT challenge resulted in 71% survival after 7 days compared with no survivors among the control animals (P < 0.001). We conclude that human IαIp may be an effective preventative or therapeutic agent against anthrax intoxication.

Our vulnerability to bioterrorism using aerosolized anthrax has become readily evident following the intentional release of anthrax spores in the U.S. mail system in October and November 2001 (10). The development of innovative strategies to treat anthrax and other biological threat pathogens has now become a major research priority (13). Anthrax spores are remarkably stable, and following inhalation, they are carried to regional lymphatic tissues in the mediastinum, where they germinate into vegetative forms and rapidly replicate. The organism possesses an antiphagocytic poly-d-glutamic acid capsule and releases a series of secreted exotoxins that specifically inhibit phagocytic cells, thereby impairing the host response to this invasive microbial pathogen (19, 24, 27). Once symptoms of systemic anthrax become manifest, it is difficult to rescue patients from lethal infection with antibacterial agents alone, as the lethality of invasive anthrax infection is principally related to its exotoxins. Once sufficient quantities of these toxins are released into the circulation, tissue damage and death will inexorably result (3, 6, 8, 14, 19). Specific treatment strategies directed toward the exotoxins of Bacillus anthracis are needed as adjuvant therapy for persons with systemic anthrax.

B. anthracis produces a combination of three exotoxins that function together as A/B toxins (6, 16). Protective antigen (PA), the B moiety of the anthrax toxins, binds to target cells and facilitates the transfer of either lethal factor (LF) or edema factor (alternative A moieties) into the cytosol of target cells (7, 17, 21, 24, 25). These toxins disturb normal cell functioning, as edema factor induces cyclic AMP formation and LF hydrolyzes an important signaling intermediate known as mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MAPKK) (8, 20). Lethal toxin (LT) connotes the combination of both the active component lethal factor and the binding component protective antigen, the cytotoxic exotoxin of B. anthracis. Highly purified, recombinant LT is sufficient to produce a lethal intoxication of mammals and is the primary virulence factor for anthrax pathogenesis (6, 24).

Although most mammalian cells possess anthrax toxin receptors (5, 16), monocyte/macrophage cell lines exhibit the most marked pathological changes when exposed to LT (20). Macrophage-depleted rodents are refractory to the injurious effects of LT (6). In susceptible animals, diffuse edema and hypoxic tissue injury, with major damage evident in the liver, spleen, and lungs, are seen following experimental LT injection, along with a rapid depletion of tissue macrophages (20). Lethal factor is a metallo-enzyme that causes the proteolysis of at least one of the essential MAPKKs (9, 16). MAPKK is an intracellular signaling molecule that appears to be fundamental for the maintenance of viability of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. The delivery of lethal factor into the cytosol of phagocytic cells causes a rapid loss of viability (6).

There are many potential targets for therapeutic intervention against anthrax lethal toxin (23, 24, 29). One potentially promising strategy is the use of inhibitors of furin (16, 22). Furin is an endogenous, membrane-associated, trypsin-like serine endoprotease that is utilized by B. anthracis as a means of activating PA once delivered to target cells (12, 22). Furin cleaves a precursor form of PA into the functionally active fragment PA63 and a soluble fragment known as PA20. Furin-mediated proteolytic activation allows PA63 to assemble seven-member pore structures on cell membranes (6, 16, 30). These PA heptamers act as delivery channels through which either edema factor or lethal factor can enter the cytosol of intoxicated cells (21, 24, 25, 27).

Inhibitors of furin have been shown to block the formation of functional PA63 heptameric units and to protect cells from the lethality of anthrax toxin and other bacterial toxins (15). We have screened a series of naturally occurring serine protease inhibitors for the ability to rescue macrophages from LT-induced cytotoxicity. One endogenous protease inhibitor, a member of the inter-alpha-inhibitor protein (IαIp) complex, was highly protective in this macrophage lethality assay and was selected for further study.

IαIp belongs to a family of structurally related serine protease inhibitors found at relatively high concentrations (400 to 800 mg/liter) in human plasma (4, 18). IαIp is a large, multicomponent, covalently linked glycopeptide-proteoglycan complex that functions as a trypsin-type protease inhibitor. Unlike other inhibitor molecules, this family of inhibitors consists of a combination of light and heavy polypeptide chains linked by a chondroitin sulfate chain (11, 26). The major forms found in human plasma are inter-alpha-inhibitor (IαI), which consists of two heavy chains (H1 and H2) and a single light chain (L), and pre-alpha-inhibitor (PαI), which consists of one heavy chain (H3) and one light chain (L). The light chain (also termed bikunin, for bi-Kunitz inhibitor [inhibitor with two Kunitz domains]) is known to broadly inhibit plasma serine proteases (11, 18, 26). The complex has been shown to be important in the inhibition of an array of proteases, including neutrophil elastase, plasmin, trypsin, chymotrypsin, cathepsin G, and acrosin. The data presented herein indicate that IαIp can protect against LT-mediated cellular toxicity in vitro and systemic toxicity in vivo.

(This work was presented in part in abstract form at the IDSA Annual Meeting, San Diego, Calif., 11 October 2003 [abstr. 712].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents.

All chemicals and reagents used for these experiments were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. Inter-alpha-inhibitor proteins were derived from human plasma samples and contained both major forms of IαIp (IαI and PαI) at >95% purity (ProThera Biologics, East Providence, RI). IαIp was first isolated from cryoprecipitated clotting factor VIII/von Willebrand factor concentrate (Octapharma Pharmaceuticals, Vienna, Austria). IαIp was then purified by ion-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography followed by size-exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography (Biosec; Merck) as previously described (18). Recombinant lethal factor and protective antigen were provided as a gift from S. H. Leppla (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Recombinant human furin was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Cytotoxicity assay.

Freshly prepared mouse peritoneal macrophages were obtained from thioglycolate-induced inflammatory ascites in BALB/c mice (1). Macrophages were harvested and incubated overnight in RPMI 1640 medium with streptomycin in a 96-well plate. Purity and viability were determined by phase-contrast microscopy and trypan blue exclusion, with a >95% viability of peritoneal macrophages. Cells were suspended in culture medium at a concentration of 1 × 105/ml and were activated by pretreatment with Escherichia coli O111:B4 lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at 20 ng/ml. IαIp was added at a concentration of 500 ng/ml. Anthrax LT (PA and LF) was added at concentrations of 100 ng/ml, 250 ng/ml, and 500 ng/ml to four wells in addition to appropriate controls. Cell survival was assessed at time zero and after 2 and 4 h by a cell titration method (Promega Life Sciences, Madison, WI) using an optical density reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Heat-inactivated IαIp was generated by boiling the protein for 1 hour at 100°C. The monoclonal antibody 69.31, which binds to an epitope located within the enzymatically active moiety of bikunin (18), was added at 100 μg/ml. The results were performed in triplicate, and the data are presented as means and standard deviations.

Furin inhibition assay.

Fluorometric assays were performed with a 0.5-ml reaction volume containing 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.5 mM fluorescent substrate Abz-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-Gly-Leu-Ala-Tyr(NO2)-Asp (American Peptide Company, Sunnyvale, CA) at 20°C. Ten nanograms of recombinant human furin (rh-furin Gly25-Glu715) was added to cleave the substrate. The fluorescence of the cleaved substrate was measured with a Perkin-Elmer LS 50B fluorometer (320-nm excitation, 425-nm emission) for 10 min. Highly purified IαIp (10, 20, and 30 μg/ml) was added to the reaction to determine if IαIp inhibits the enzymatic hydrolysis of the fluorogenic substrate by furin.

Animal model.

Female specific-pathogen-free BALB/c mice were used for animal model experiments. The animals were 8 to 10 weeks old and were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). The experimental protocol was approved by the Brown University Animal Care Committee and followed the IACUC guidelines for biomedical research. The mice were given IαIp (30 mg/kg of body weight) intravenously, followed after 1 hour by an approximately 100% intravenous lethal dose of LT (PA, 50 μg/mouse; LF, 10 μg/mouse). The mice were randomly assigned to the IαIp-treated group (n = 14) or the saline control group (n = 9). As additional controls, five animals/group were given either IαIp (30 mg/kg) followed by a saline challenge or two doses of saline without either IαIp or the LT challenge. Survival was monitored for 7 days after challenge. All animals were subjected to necropsy examination at the end of the experiment.

Histopathologic examination.

The lung and splenic tissues were excised, whereupon the spleen was further analyzed following hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The histologic slides were interpreted by a pathologist who was blinded to the treatment assignment for each animal. Histopathology was scored using a scale from 1 to 4, as follows: 1, normal murine splenic histology; 2, mild cellular loss and necrosis; 3, moderate cellular loss and disruption of splenic architecture; and 4, marked necrosis and cellular loss within the red pulp.

The excised lung tissue was immediately weighed and then desiccated and weighed again to obtain the wet-to-dry ratio as an indicator of lung water and pulmonary edema. A myeloperoxidase (MPO) quantitative stain was performed with the splenic tissue, using a PMB liquid substrate system (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). After weighing of the splenic tissue and mincing of the sample, the myeloperoxidase activity was determined in units of activity/gram of splenic tissue.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical comparisons were made using a nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. The survival differences were determined using Kaplan-Meier survival plots and were analyzed by a rank-sum test. A probability of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

IαIp activity against LT-induced cytotoxicity in murine peritoneal macrophages.

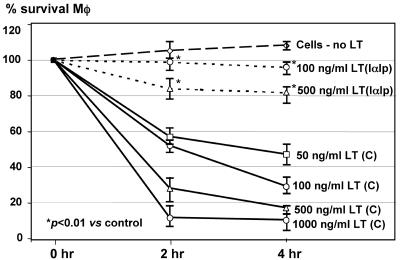

In the cytotoxicity assay, IαIp was effective at enhancing the cell survival of LPS-activated peritoneal macrophages at LT concentrations of 100 ng/ml and 500 ng/ml. IαIp provided a significant degree of protection by increasing cell survival from 25 to 40% to 85 to 100% (Fig. 1). The protective activity of IαIp was abolished by heat inactivation of IαIp or the administration of MAb 69.31, an antibody that binds to the epitope located in the enzymatically active moiety of IαIp (bikunin) (data not shown). This suggests that the epitope recognized by this MAb within the active site of IαIp plays a role in the protective activity of IαIp against LT.

FIG. 1.

Cytotoxicity assay with murine peritoneal macrophages exposed to increasing concentrations of LT ranging from 0 to 500 ng/ml in the presence or absence of IαIp (500 ng/ml). *, P < 0.01 for the percent viability at 100 or 500 ng/ml LT with IαIp versus that without IαIp. C, control; Mφ, macrophage.

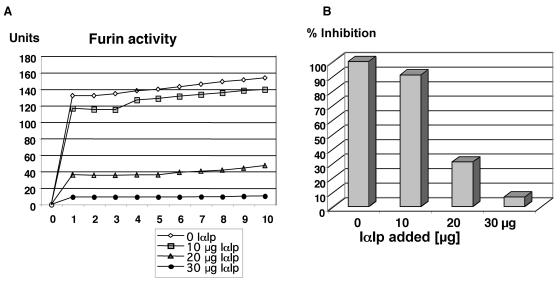

IαIp furin inhibitory activity in vitro.

As shown in Fig. 2, highly purified IαIp was able to inhibit the hydrolysis of the substrate Abz-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-Gly-Leu-Ala-Tyr (NO2)-Asp by recombinant human furin in a concentration-dependent manner. The levels of IαIp needed to inhibit >85% of the furin enzymatic activity in this in vitro assay were within the therapeutic range of experimental IαIp treatment regimens used in small animal models (32).

FIG. 2.

(A) Furin inhibition assay with increasing concentrations of IαIp inhibiting recombinant human furin activity over time, as measured by the generation of a fluorometric substrate. (B) Percent inhibition of furin activity as a function of increasing concentrations of IαIp (0 to 30 μg/ml) after 10 min of incubation with the fluorometric substrate.

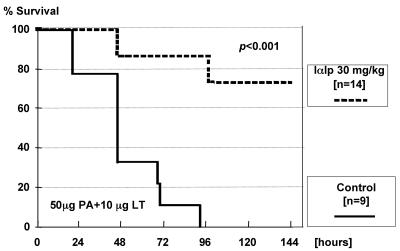

In vivo protection of IαIp following LT challenge.

The activity of IαIp in vivo was tested by LT challenge studies with BALB/c mice. A pretreatment with 30 mg/kg IαIp 1 hour before a lethal dose of LT (PA, 50 μg per mouse; LF, 10 μg per mouse) was effective in this mouse model of anthrax intoxication. Survival was monitored for up to 7 days; all mice in the control group succumbed within 96 h, while 71% (10 of 14) of the IαIp-treated mice were long-term survivors. The difference between both groups was statistically significant (P < 0.001). Kaplan-Meier plots of these data are shown in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival plots for BALB/c mice treated with IαIp (n = 14) or saline (n = 9) 1 hour before a 100% lethal challenge dose of LT given intravenously.

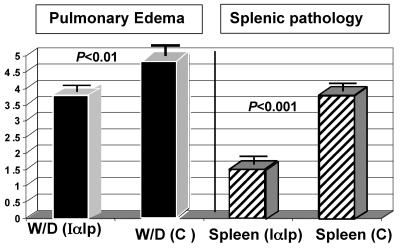

Effects of IαIp on histopathologic changes induced by LT.

Lung and spleen tissues were excised from the experimental animals, and significant differences were observed in the splenic histological architecture and the wet/dry weight ratio of lung tissue (a measure of vascular leakage). The results of these analyses are shown in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

Pulmonary edema indexes and splenic pathology scores to compare the saline-treated control group with the IαIp-treated group following LT challenge. W/D, wet-to-dry weight ratio; C, control (saline). Splenic pathology was assessed histologically (by H&E staining) according to the following scoring system: 1, normal; 2, mild cellular loss; 3, moderate pathology; and 4, marked pathology.

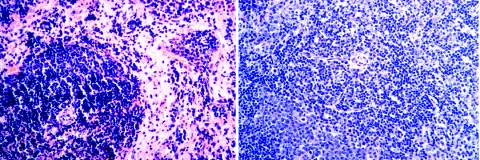

The administration of IαIp protected mice against LT-induced tissue injury in lung and spleen tissues. Statistically significant differences in both measured parameters were achieved between the treatment and control groups (for wet/dry weight ratios, P < 0.01; for splenic histology scores, P < 0.001). Representative H&E-stained sections of splenic tissue from mice treated with LT and saline (control) or with LT and IαIp are shown in Fig. 5. As expected, the splenic histology in saline control-treated or IαIp-treated animals without LT challenge revealed no pathological changes (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Histopathology of the spleen. The images show a penicillary artery surrounded by preserved white pulp with an extensive loss of red pulp cellular elements from an LT-plus-saline-treated control animal (left) and one with normal surrounding white pulp and slightly hypercellular red pulp from an LT-plus-IαIp-treated animal (right) (H&E stain). Magnification, ×20.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, a measure of the splenic monocyte/macrophage cell density (28), showed a highly significant (P < 0.0001) reduction following LT treatment. The median (with 95% confidence intervals) value for MPO activity measured in saline-treated control animals was 6.5 (4.7 to 8.8) MPO activity units/g. The IαIp treatment of LT-treated animals nearly corrected the MPO values to normal levels (5.75 [4.55 to 8.1] activity units/gram of spleen tissue for the group receiving LT plus IαIp versus 1.9 [1.25 to 2.25] activity units/gram of spleen tissue for the group receiving LT plus saline).

DISCUSSION

IαIp is a naturally occurring serine protease inhibitor that regulates the activity of a wide spectrum of endogenous proteases (18, 26). One target protease of IαIp may be furin, an enzyme essential to the assembly of LT in anthrax pathogenesis. We hypothesize that IαIp as a protease inhibitor regulates furin activity. In the presence of LT, the IαIp-mediated limitation of furin activity may prevent the assembly of the PA63 heptameric pore structure which is necessary to transport the A toxin moiety (lethal factor in these experiments) into the cytosol of target cells. Bikunin is the active component of IαIp possessing its protease inhibitor functions. Bikunin contains Arg-X-X-Arg sites that are likely to bind to furin (22). As systemic inflammation and the consumption of IαIp progress over the course of a generalized infection such as disseminated anthrax infection, the loss of this endogenous inhibitor of furin may result in a derepression of furin activity. This may accelerate the processing and delivery of LT to target sites, with potentially fatal consequences. IαIp is highly protective against cytotoxicity in a cell culture assay of freshly isolated and LPS-activated peritoneal macrophages, and IαIp provides a survival benefit against an otherwise lethal dose of LT in this susceptible mouse strain.

In our previous study (1) and another recent report (20), pulmonary edema and pleural effusions were frequently observed following LT administration to mice. Lung water levels were markedly elevated in LT-treated animals, while IαIp significantly attenuated the amount of pulmonary edema fluid in this animal model. Macrophage loss and histopathologic changes were also reduced significantly with the administration of IαIp treatment.

Hepatic IαIp synthesis is down regulated during severe inflammation, and one of the major forms of IαIp (IαI) is considered a negative acute-phase protein (18, 26, 32). Recently, a significant decrease in IαIp levels in the plasma of patients and newborns with clinically proven sepsis was demonstrated (2, 18). In adult septic patients, the magnitude of the decrease in the IαIp level correlates with an excessive mortality rate (18). Moreover, in an experimental animal model of polymicrobial intra-abdominal sepsis, IαIp administration maintained hemodynamic stability, prevented organ injury, and improved survival (32).

Circulating levels of IαIp are “consumed” during systemic bacterial infections, and it is likely that a similar process occurs during anthrax infection, leading to decreased plasma levels of IαIp. The restoration of IαIp levels by administration of this physiologic furin inhibitor should limit LT-mediated tissue injury in persons with systemic anthrax infection, thus providing the opportunity for active antimicrobials to clear this highly fatal infection.

The present experiments indicate that IαIp enhances survival after an LT challenge by furin inhibition. IαIp is a direct furin inhibitor in vitro (Fig. 2). In the cytotoxicity assay, the protective effect of IαIp was lost by the addition of an antibody against human bikunin (MAb 69.31) or when heat-inactivated and denatured IαIp was used. These findings indicate the need for functional IαIp protease inhibitor activity for protection against LT-related intoxication.

In addition to IαIp-mediated furin inhibition, there are several other possible mechanisms by which IαIp might afford protection against lethal anthrax infection (6, 18). IαIp has anti-inflammatory effects attributed to its ability to inactivate plasmin, a protein which participates in fibrinolysis but also activates latent metalloproteinases which degrade the extracellular matrix. Plasmin also provides feedback in a positive manner to increase the cleavage of plasminogen to plasmin. Modulating the effects of plasmin may modulate multiple pathological processes that are possibly involved in anthrax pathogenesis.

IαIp is also known to avidly bind TSG6, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)/interleukin 1-inducible protein. TSG6 has marked anti-inflammatory effects when bound to IαIp (31). Other anti-inflammatory molecules such as an interleukin 1 inhibitor and a TNF inhibitor (8) have protective effects against experimental anthrax infection. It is possible that some of the beneficial effects of IαIp in vivo are related to the anti-inflammatory capacities of the IαIp/TSG6 complex.

Anthrax intoxication induces neutrophilia (3, 10). IαIp, by neutralizing elastase and cathepsin G, may control potential damage initiated by these enzymes found in the granules of neutrophils. Alternatively, IαIp has a von Willenbrand factor-like sequence found in one of its heavy chains (4, 26). The anthrax PA binding site on eukaryotic cells has a type A von Willenbrand factor domain motif (5). It is possible that the heavy chain of IαIp also serves as a receptor decoy for PA of anthrax toxin and promotes the clearance of PA from the circulation.

In summary, IαIp may be a safe and uniquely well-suited agent for use in cases of both anthrax intoxication and systemic bacterial sepsis. IαIp is an endogenous human plasma protein, and a related member of the IαIp family known as urinary trypsin inhibitor has been used to treat systemic inflammatory states in patients in Japan for many years (18). The safety profile of this plasma glycoprotein complex in humans is already well established. Determining the precise mechanism(s) of action afforded by IαIp against lethality from anthrax toxins and performing an assessment of its protective efficacy in actual infection models with virulent strains of anthrax will necessitate further study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R21-AI53426-01.

Editor: D. L. Burns

REFERENCES

- 1.Artenstein, A., P. Cristofaro, S. M. Opal, J. E. Palardy, and N. Parejo. 2004. Chloroquine enhances survival in Bacillus anthracis intoxication. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1655-1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baek, Y. W., S. Brokat, J. F. Padbury, H. Pinar, D. C. Hixson, and Y.-P. Lim. 2003. Inter-alpha inhibitor proteins in infants and decreased levels in neonatal sepsis. J. Pediatr. 143:11-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borio, L., D. Frank, V. Mani, C. Chiriboga, M. Pollanen, M. Ripple, S. Ali, C. DiAngelo, J. Lee, J. Arden, J. Titus, D. Fowler, T. O'Toole, H. Masur, J. Bartlett, and T. Inglesby. 2001. Death due to bioterrorism-related inhalational anthrax. JAMA 286:2554-2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bost, F., M. Diarra-Mehrpour, and J. Martin. 1998. Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor proteoglycan family; a group of proteins binding and stabilizing the extracellular matrix. Eur. J. Biochem. 252:339-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley, K., J. Mogridge, M. Mourez, R. J. Collier, and J. A. Young. 2001. Identification of the cellular receptor for anthrax toxin. Nature 414:225-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collier, R., and J. Young. 2003. Anthrax toxin. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 19:45-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham, K., D. B. Lacy, J. Mogridge, and R. J. Collier. 2002. Mapping the lethal factor and edema factor binding sites on oligomeric anthrax protective antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7049-7053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon, T., M. Meselson, J. Guillemin, and P. Hanna. 1999. Anthrax. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:815-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duesbery, N., C. P. Webb, S. H. Leppla, V. M. Gordon, K. R. Klimpel, T. D. Copeland, N. G. Ahn, M. K. Oskarsson, K. Fukasawa, K. D. Paull, and G. F. Van de Woude. 1998. Proteolytic inactivation of MAP-kinase-kinase by anthrax lethal factor. Science 289:734-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedlander, A. M. 2001. Tackling anthrax. Nature 414:160-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fries, E., and A. Blom. 2000. Bikunin—not just a plasma proteinase inhibitor. Int. J. Biochem. Cell 32:125-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon, V., K. Klimpel, N. Arora, M. Henderson, and S. H. Leppla. 1995. Proteolytic activation of bacterial toxins by eukaryotic cells is performed by furin and by additional cellular proteases. Infect. Immun. 63:82-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirschberg, R., J. La Montagne, and A. S. Fauci. 2004. Biomedical research—an integral component of national security. N. Engl. J. Med. 350:2119-2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inglesby, T., D. A. Henderson, and J. G. Bartlett, for the Working Group on Civilian Biodefense. 1999. Anthrax as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA 281:1735-1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jean, F., K. Stella, L. Thomas, G. Liu, Y. Xiang, A. J. Reason, and G. Thomas. 1998. Alpha antitrypsin Portland, a bioengineered serpin highly selective for furin: application as an antipathogenic agent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7293-7298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lacy, D., and R. Collier. 2002. Structure and function of anthrax toxin. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 271:61-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacy, D., M. Mourez, A. Fouassier, and R. J. Collier. 2002. Mapping the anthrax protective antigen binding site on the lethal and edema factors. J. Biol. Chem. 277:3006-3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim, Y.-P., K. Bendelja, S. Opal, E. Siryaporin, D. Hixson, and J. Palardy. 2003. Correlation between mortality and the levels of inter-alpha inhibitors in the plasma of patients with severe sepsis. J. Infect. Dis. 188:919-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayer, T., S. Bersoff-Matcha, J. Earls, S. Harper, D. Pauze, M. Nguyen, J. Rosenthal, D. Cerva, Jr., G. Druckenbrod, D. Hanfling, N. Fatteh, A. Napoli, A. Nayyar, and E. L. Berman. 2001. Clinical presentation of inhalational anthrax following bioterrorism exposure. JAMA 286:2549-2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moayeri, M., D. Haines, H. Young, and S. H. Leppla. 2003. Bacillus anthracis lethal toxin induces TNF-alpha-independent hypoxia-mediated toxicity in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 112:670-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mogridge, J., K. Cunningham, D. B. Lacy, M. Mourez, and R. J. Collier. 2002. The lethal and edema factors of anthrax toxin bind only to oligomeric forms of the protective antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7045-7048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molloy, S., P. Bresnahan, S. H. Leppla, K. Klimpel, and G. Thomas. 1992. Human furin is a calcium-dependent serine endoprotease that recognizes the sequence Arg-X-X-Arg and efficiently cleaves anthrax toxin protective antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 267:16396-16402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mourez, M., R. S. Kane, J. Mogridge, S. Metallo, P. Deschatelets, B. R. Sellman, G. M. Whitesides, and R. J. Collier. 2001. Designing a polyvalent inhibitor of anthrax toxin. Nat. Biotechnol. 19:958-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mourez, M., D. Lacey, K. Cunningham, R. Legmann, B. Sellman, and J. Mogridge. 2002. 2001: a year of major advances in anthrax toxin research. Trends Microbiol. 10:287-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nassi, S., R. J. Collier, and A. Finkelstein. 2002. PA 63 channel of anthrax toxin: an extended beta-barrel. Biochemistry 41:1445-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salier, J., P. Rouet, G. Raguenez, and M. Daveau. 1996. The inter-alpha-inhibitor family: from structure to regulation. Biochem. J. 315:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Starnbach, M., and R. Collier. 2003. Anthrax delivers a lethal blow to host immunity. Nat. Med. 9:996-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki, K., H. Ota, S. Sasagawa, T. Sakatani, and T. Fujikura. 1983. Assay method for myeloperoxidase in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Anal. Biochem. 132:345-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tonello, F., M. Seveso, O. Marin, M. Mock, and C. Montecucco. 2002. Screening inhibitors of anthrax lethal factor. Nature 418:386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varughese, M., A. Teixeira, S. Liu, and S. Leppla. 1999. Identification of a receptor-binding region within domain 4 of the protective antigen component of anthrax toxin. Infect. Immun. 67:1860-1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wisniewski, H., J. Hua, D. Poppers, D. Naime, J. Vilcek, and B. Cronstein. 1996. TNF/IL-1-inducible protein TSG-6 potentiates plasmin inhibition by inter-alpha-inhibitor and exerts a strong anti-inflammatory effect in vivo. J. Immunol. 156:1609-1615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang, S., Y.-P. Lim, M. Zhou, P. Salvemini, H. Schwinn, D. Josic, D. Koo, I. H. Chaudry, and P. Wang. 2002. Administration of human inter-alpha-inhibitor maintains hemodynamic stability and improves survival during sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 30:617-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]