Abstract

Forty group A streptococcus (GAS) isolates, recovered during a scarlet fever outbreak, were grouped based on their DdeI restriction profiles from emm amplicons. Twenty-seven isolates were identified by sequencing as emm2. The emm2 isolates showed the speA1, speB1, and speC1 alleles. Isolation of this GAS type from scarlet fever outbreaks is uncommon.

The group A streptococcus (GAS) M2 serotype, in addition to the M49, M57, M59, M60, and M61 serotypes, has been associated with pyoderma and acute glomerulonephritis (5, 26). This serotype is also related to uncomplicated infections (10, 11). The M2 serotype had been frequently associated with scarlet fever (5 to 45%) in several countries in the 1930s (24), as well as in isolates recovered in 1940 and 1941 in Ottawa (15). In the 1970s, this serotype was associated with acute glomerulonephritis following a scarlet fever episode in Mexico (23) and elsewhere (1, 6). Nevertheless, the isolation of the M2 serotype from scarlet fever patients has become uncommon according to recent reports, in which the M1, M3, M4, M6, M18, and M22 serotypes were linked to scarlet fever cases (4, 9, 14, 15, 20, 22), while the incidence of emm2 in invasive infections over a 5-year population-based survey in the United States was 1.6% (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/strep/emmdata.htm1#emm2). In this study, a molecular strategy was used to identify and analyze some genes encoding GAS virulence factors in 40 isolates recovered during an outbreak of scarlet fever in an orphanage in Mexico City, Mexico. The outbreak involved nine patients of a total population of 116 children and occurred between October and November 1999. Forty GAS isolates (from 9 patients and 31 contacts) were analyzed. Biochemical identification and antibiotic susceptibility tests were performed with a VITEK system (BioMeriux). Chromosomal DNA was isolated by previously described methods (13).

PCR was used to amplify the genes encoding the M protein (emm), streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxins A (speA) and C (speC), cysteine protease (speB), and streptococcal inhibitor of complement (sic) using primers as previously described (2, 3, 13, 16, 21, 27). The emm restriction patterns were grouped to avoid sequence analysis of the entire set of identical emm types. A first digestion with the DdeI enzyme was performed, followed by a second digestion with selected isolates using the HaeIII and HincII enzymes in order to confirm that these strains had the same restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) pattern. Tests were performed as recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/strep/protocols.html). Two isolatesfrom each emm RFLP group were used for emm gene sequencing. Sequencing of the speA, speB, and speC genes was carried out for isolates ACGP113 and ACGP117 from the major RFLP group (typed as emm2). Strategies for analyzing sequence variations in the emm, speA, speB, and speC genes have been described previously (2, 13, 17, 18, 27). Sequence data were obtained using an Applied Biosystems model 310 automated DNA sequencer. These were then assembled and edited electronically with the EDITSEQ and MEGALING programs (DNASTAR, Madison Wis.) and compared with published sequences of emm, speA, speB, and speC (2, 3, 7, 13, 18, 27).

While all isolates contained the speB and speC genes, the speA gene was detected in 70% of isolates and the sic gene was positive in only two of the isolates (5%), which were identified by sequencing as emm1 (Table 1). The sic gene has been recognized as an important epidemiological marker for this serotype (8, 21).

TABLE 1.

Presence of speA, speB, speC, and sic genes among GAS isolates

| emm type | Total no. of isolates | No. of patients | No. of contacts | No. (%) of isolates with:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| speA | speB and speC | sic | ||||

| emm2 | 27 | 8 | 19 | 27 (100) | 27 (100) | |

| emm12 | 9 | 9 | 9 (100) | |||

| emm1 | 2 | 2 | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | |

| emm22 | 1 | 1 | 1 (100) | |||

| emm89 | 1 | 1 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | ||

| Total | 40 | 9 | 31 | 29 (72.5) | 40 (100) | 2 (5) |

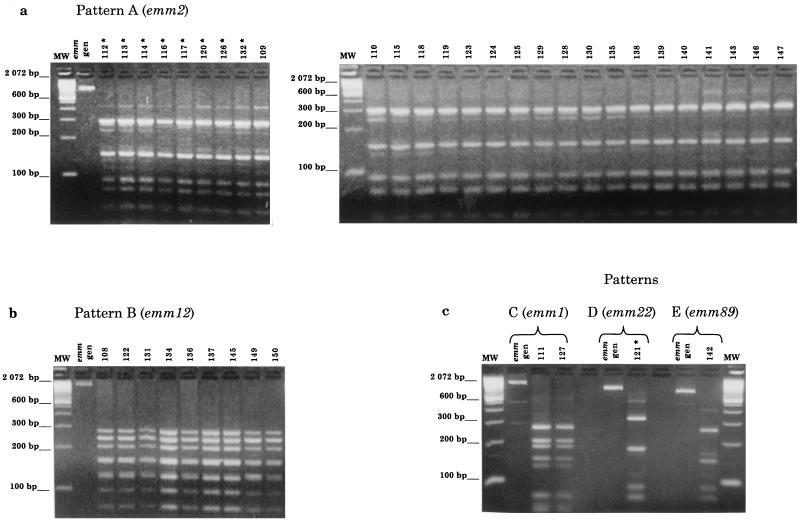

The 40 GAS isolates were grouped into five different emm RFLP patterns, designated A to E (Fig. 1). Twenty-seven isolates (8 from patients and 19 from contacts) shared pattern A and were identified as type emm2 by DNA sequence analysis (Table 2). Nine isolates from contacts were identified as type emm12 (pattern B), two were identified as type emm1 (pattern C), and another was identified as type emm89 (formerly pt4245) (pattern E). One isolate from a patient was identified as type emm22 (pattern D) (Fig. 1). The emm alleles identified were identical to those deposited in GenBank (Table 2).

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of emm amplicon RFLP patterns, using DdeI enzyme, of 40 GAS strains isolated from a scarlet fever outbreak. (a) Pattern A (emm2), 27 isolates (8 patients [*] and 19 contacts). (b) Pattern B (emm12), nine isolates (contacts). (c) Pattern C (emm1), two isolates (contacts); pattern D (emm22), one isolate (patient [*]); and pattern E (emm89), one isolate (contact). The emm type was identified by DNA sequence analysis. Lanes MW, size marker (100-bp ladder).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of 5′ emm sequences (147 bp) from five emm RFLP patterns with emm reference sequences in GenBank

| emm RFPL pattern (no. of isolates) | Closest emm sequencing matcha (GenBank accession no.) |

|---|---|

| A (27) | emm2 (U11958) |

| B (9) | emm12 (U11937) |

| C (2) | emm1 (U11940) |

| D (1) | emm22 (U11955) |

| E (1) | emm89 (formerly pt4245) (U11966) |

The closest match indicated corresponds to 100% identity.

The evidence showing that the GAS emm2 type was responsible for this outbreak was as follows: (i) most of the isolates (27 of 40 [67%]) shared the same emm RFLP pattern, which was identified by sequencing as emm2; (ii) all isolates except one from patients (8 of 9) were grouped as emm2; and (iii) all isolates grouped as emm2 were positive for the speA gene (Table 1). The last outbreak of scarlet fever caused by the M2 serotype was a classroom outbreak in Compton, Calif., reported by Anthony et al. in 1974 (1). It is likely that the M2 serotype remains in the population, causing uncomplicated infections such as pharyngitis and scarlet fever (10, 11). However, little is known about the characteristics of GAS isolates involved in scarlet fever episodes in Mexico.

The sequence variation analysis of speA, speB, and speC in the emm2 isolates showed the presence of the speA1 (GenBank accession no. X61558), speB1 (GenBank accession no. L26125), and speC1 (GenBank accession no. M97156) alleles, respectively. The speA1 allele is the most frequent allelic variant among isolates of different emm types and has been previously associated with the M2 serotype (17, 18). However, Bessen et al. demonstrated the absence of speA in five different emm2 isolates dating from 1941 to 1995 (3). The speB1 allele encodes the mature SpeB1 variant, which represents a conserved speB allele in GAS (25).

Five allelic variants (speC1 to speC5) have been described for speC (3, 12, 19), and a strong association has been observed between emm patterns and speC alleles (3). The speC1 and speC2 alleles are the most common in GAS strains (>80%). While Bessen et al. described an association between the M2 type and the speC4 allele (3), the emm2 isolates analyzed in this study contained the speC1 allele variant. This shows a variation of speC alleles between organisms belonging to the same emm type. The same emm type could show different speC alleles, as described by Kapur et al. for the reference sequences of speC1 and speC2 (GenBank accession no. M97156 and M97157) being from the M3 type (12). There may be two different lineages of emm2, and it would be interesting to analyze the speA and speC genes in more M2 isolates to discover the allelic variation in this and other GAS M serotypes.

This study demonstrates the benefit of molecular methods in identifying and characterizing GAS strains involved in this scarlet fever outbreak, in which an uncommon GAS emm2 type with conserved alleles of the speA, speB, and speC genes was responsible.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant 28046M from the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACyT).

We thank Miguel Angel Fernández (Facultad de Medicina, UNAM) for providing the strains and Laura Ongay (Instituto de Fisiología Celular, UNAM) for performing the sequencing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anthony, B. F., T. Yamauchi, J. S. Penso, I. Kamei, and S. S. Chapman. 1974. Classroom outbreak of scarlet fever and acute glomerulonephritis related to type 2 (M-2, T-2) group A Streptococcus. J. Infect. Dis. 129:336–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beall, B., R. Facklam, and T. Thompson. 1996. Sequencing emm-specific PCR products for routine and accurate typing of group A streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:953–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bessen, D. E., M. W. Izzo, T. R. Fiorentino, R. M. Caringal, S. K. Hollingshead, and B. Beall. 1999. Genetic linkage of exotoxin alleles and emm gene markers for tissue tropism in group A streptococci. J. Infect. Dis. 179:627–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannaday, P., T. McNitt, K. Horn, H. Goodpasture, and L. O. Gentry. 1976. A family outbreak of serious streptococcal infection. JAMA 236:585–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham, M. W. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:470–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dillon, H. C. 1968. Acute glomerulonephritis following skin infection due to streptococci of M-type 2. Lancet 1:543–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauser, A. R., and P. M. Schlievert. 1990. Nucleotide sequence of the streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin type B gene and relationship between the toxin and the streptococcal proteinase precursor. J. Bacteriol. 172:4536–4542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoe, N. P., K. Nakashima, S. Lukomski, D. Grigsby, M. Liu, P. Kordari, S. J. Dou, X. Pan, J. Vuopio-Varkila, S. Salmelinna, A. McGeer, D. E. Low, B. Schwartz, A. Schuchat, S. Naidich, D. De Lorenzo, Y. X. Fu, and J. M. Musser. 1999. Rapid selection of complement-inhibiting protein variants in group A Streptococcus epidemic waves. Nat. Med. 5:924–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsueh, P. R., L. J. Teng, P. I. Lee, P. C. Yang, L. M. Huang, S. C. Chang, C. Y. Lee, and K. T. Luh. 1997. Outbreak of scarlet fever at a hospital day care center: analysis of strain relatedness with phenotypic and genotypic characteristics. J. Hosp. Infect. 36:191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson, D. R., D. L. Stevens, and E. L. Kaplan. 1992. Epidemiologic analysis of group A streptococcal serotypes associated with severe systemic infections, rheumatic fever, or uncomplicated pharyngitis. J. Infect. Dis. 166:374–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan, E. D., D. R. Johnson, and C. D. Rehder. 1994. Recent changes in group A streptococcal serotypes from uncomplicated pharyngitis: a reflection of the changing epidemiology of severe group A infections? J. Infect. Dis. 170:1346–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapur, V., K. Nelson, P. M. Schlievert, R. K. Selander, and J. M. Musser. 1992. Molecular population genetic evidence of horizontal spread of two alleles of the pyrogenic exotoxin C gene (speC) among pathogenic clones of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 60:3513–3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapur, V., S. Topouzis, M. W. Majesky, L. L. Li, M. R. Hamrick, R. J. Hamill, J. M. Patti, and J. M. Musser. 1993. A conserved Streptococcus pyogenes extracellular cysteine protease cleaves human fibronectin and degrades vitronectin. Microb. Pathog. 15:327–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knoll, H., J. Sramek, K. Vrbova, D. Gerlach, W. Reichardt, and W. Kohler. 1991. Scarlet fever and types of erythrogenic toxins produced by the infecting streptococcal strains. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 276:94–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musser, J. M., K. Nelson, R. K. Selander, D. Gerlach, J. C. Huang, V. Kapur, and S. Kanjilal. 1993. Temporal variation in bacterial disease frequency: molecular population genetic analysis of scarlet fever epidemics in Ottawa and in eastern Germany. J. Infect. Dis. 167:759–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musser, J. M., V. Kapur, J. Szeto, X. Pan, D. S. Swanson, and D. R. Martin. 1995. Genetic diversity and relationships among Streptococcus pyogenes strains expressing serotype M1 protein: recent intercontinental spread of a subclone causing episodes of invasive disease. Infect. Immun. 63:994–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musser, J. M., V. Kapur, S. Kanjilal, U. Shah, D. M. Musher, N. L. Barg, K. H. Johnston, P. M. Schlievert, J. Henrichsen, D. Gerlach, R. M. Rakita, A. Tanna, B. D. Cookson, and J, C. Huang. 1993. Geographic and temporal distribution and molecular characterization of two highly pathogenic clones of Streptococcus pyogenes expressing allelic variants of pyrogenic exotoxin A (scarlet fever toxin). J. Infect. Dis. 167:337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson, K., P. M. Schlievert, R. K. Selander, and J. M. Musser. 1991. Characterization and clonal distribution of four alleles of the speA gene encoding pyrogenic exotoxin A (scarlet fever toxin) in Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Exp. Med. 174:1271–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norrby-Teglund, A., S. E. Holm, and M. Norgren. 1994. Detection and nucleotide sequence analysis of the speC gene in Swedish clinical group A streptococcal isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:705–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohga, S., K. Okada, K. Mitsui, T. Aoki, and K. Ueda. 1992. Outbreaks of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis in children: correlation of serotype T4 with scarlet fever. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 24:599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perea-Mejia, L. M., K. E. Stockbauer, X. Pan, A. Cravioto, and J. M. Musser. 1997. Characterization of group A Streptococcus strains recovered from Mexican children with pharyngitis by automated DNA sequencing of virulence-related genes: unexpectedly large variation in the gene (sic) encoding a complement-inhibiting protein. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:3220–3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perks, E. M., and R. T. Mayon-White. 1983. The incidence of scarlet fever. J. Hyg. 91:203–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez, R. S. 1973. Tipificación del estreptococo beta hemolítico del grupo A, su importancia en relación con la glomérulonefritis aguda, fiebre escarlatina y otras enfermedades. Bol. Med. Hosp. Infant. 30:949–962. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwentker, F. F., J. H. Janney, and J. E. Gordon. 1943. The epidemiology of scarlet fever. Am. J. Hyg. 38:27–98. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stockbauer, K. E., L. Magoun, M. Liu, E. H. Burns, S. Gubba, S. Renish, X. Pan, S. C. Bodary, E. Baker, J. Coburn, J. M. Leong, and J. M. Musser. 1999. A natural variant of the cysteine protease virulence factor of group A Streptococcus with an arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) motif preferentially binds human integrins alphavbeta3 and alphaIIbbeta3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:242–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stollerman, G. H. 1977. Rheumatic fever. Lancet 349:935–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whatmore, A. M., V. Kapur, D. J. Sullivan, J. M. Musser, and M. A. Kehoe. 1994. Non-congruent relationships between variation in emm gene sequences and the population genetic structure of group A streptococci. Mol. Microbiol. 14:619–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]