Abstract

We describe here a multiplex reverse transcription-PCR (RTMNPCR) assay designed to detect and differentiate measles virus, rubella virus, and parvovirus B19. Serial dilution experiments with vaccine strains that compared cell culture isolation of measles in B95 cells and rubella in RK13 cells showed sensitivity rates of 0.004 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) for measles virus and 0.04 TCID50 for rubella virus. This RTMNPCR can detect as few as 10 molecules for measles virus and rubella virus and one molecule for parvovirus B19 in dilution experiments with plasmids containing inserts of the primary reaction amplification products. Five pharyngeal exudates from measles patients and 2 of 15 cerebrospinal fluid samples from measles-related encephalitis were found to be positive for measles virus by this RTMNPCR. A total of 3 of 27 pharyngeal exudates from vaccinated children and 2 pharyngeal exudates, plus one urine sample from a case of congenital rubella syndrome, were found to be positive for rubella virus by RTMNPCR, whereas 16 of 19 sera from patients with erythema infectiosum were determined to be positive for parvovirus B19 by RTMNPCR. In view of these results, we can assess that this method is a useful tool in the diagnosis of these three viruses and could be used as an effective surveillance tool in measles eradication programs.

Measles virus (MeV), rubella virus (RUBV), and parvovirus B19 (B19V) are frequent causes of exanthematic diseases (2). Although a mild rash illness is the usual clinical expression for all of these types of infection, serious secondary respiratory infections due to opportunistic pathogens are frequent during measles, as a result of the transitory immunodeficiency brought on by MeV. Other serious complications of MeV infection are postinfection acute measles encephalomyelitis (28), as well as giant cell pneumonia (20) and inclusion body encephalitis in immunodepressed patients (28). Congenital rubella syndrome is the most serious complication of the acute RUBV infections (43), although postinfection encephalopathy (18), arthropathies, and transient depression of thrombocyte counts (43) are other possible complications. Finally, nonimmune hydrops fetalis, arthropathies, and transient aplastic crisis in patients with underlying hemolytic disease (46) are the most frequent complications of B19V acute infection. The ability to establish persistent infections is well known for MeV, and this is the cause of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (28) which has also, albeit rarely, been found to be caused by RUBV (18). Long-term arthritis and chronic anemia in immunodepressed patients (46) are the best-known clinical expressions of persistent infection by B19V, although this has been detected in bone marrow (8) and in the sinovial tissues of healthy individuals (40).

Direct diagnosis by viral isolation in cell cultures is not possible for B19V. This approach is slow and tedious and has low efficiency for MeV and RUBV diagnosis. Serological diagnosis by specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) detection is the method of choice for all of these. Although this method provides an easy and rapid diagnosis, it has some drawbacks. False-positive reactions due to cross-reactivity are not infrequent, even with assays recommended for clinical use (14, 21, 42). The serological response is often poor in immunocompromised patients, and specific IgM is frequently absent in chronic infections (27). PCR has been shown to be an excellent tool for the direct detection of these viruses in clinical samples and, consequently, a useful complement for IgM detection for diagnostic purposes. Several individual PCR techniques have been described for each virus (3, 5, 9, 12, 13, 15–17, 23, 24, 29–31, 34, 37, 39, 41, 45).

The World Health Organization is currently attempting to reduce measles morbidity and mortality worldwide. Some regions are already planning the total eradication of the illness by the end of the first decade of this century (10, 11). An important part of these eradication plans is the surveillance of native measles in each region. This requires not only laboratory diagnosis of all cases which meet the clinical definition but also genotype characterization of the MeV strains involved in each sporadic case or outbreak, so that these may be classified as native or imported (44). Consequently, serologic diagnosis alone is not enough, and direct detection techniques able to produce viral RNA are necessary for monitoring measles eradication plans. Since rash illness caused by RUBV and B19V can be easily confused with measles virus infection, differential diagnosis is recommended for surveillance activities (4, 32), especially in the last stages of the eradication programs when no real measles cases are expected.

We describe here a new reverse transcription multiplex nested PCR (RTMNPCR) with internal control able to simultaneously detect and identify MeV, RUBV, and B19V in clinical samples. The usefulness of the technique for diagnosis and epidemiological surveillance is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus strains.

Schwarz MeV and RA27/3 RUBV vaccine strains (Beecham, Madrid, Spain), as well as a sample known to contain B19V, were used for standardization and dilution experiments. A B19V panel from the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (Hertfordshire, United Kingdom), used for an international B19V PCR quality control (36), was used for evaluation, as well as an international MeV genotype panel (1, 44) prepared by the WHO Measles Reference Laboratory at the Centers for Disease Control (Atlanta, Ga.), including the following strains: Edmonston-wt.USA/54 (A), Chicago.USA/89/1 (D3), Palau.BLN/93 (D5), Bangkok.THA/93/1 (D5), “JM”.USA/77 (C2), New Jersey.USA/94/1 (D6), Hunan.CHN/93/7 (H), Montreal.CAN/89 (D4), and Yaounde.CAE/83/14 (B1). Individual wild isolates of parainfluenzaviruses 1, 2, 3, 4A, and 4B, adenovirus 5, parotitis virus, respiratory syncytial viruses A and B, and East equine encephalitis virus (togavirus) from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III collection were used to evaluate the specificity of the assay.

Clinical samples.

Results for the various groups of clinical samples are presented in Table 1). Five pharyngeal swabs and four sera from five children involved in a measles outbreak in Soria, Spain, in 1992 made up group 1. Group 2 included 22 cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and 11 serum samples from patients suffering from measles-related encephalitis. Three urine samples, three RUBV IgM-positive sera, and two pharyngeal exudates from one newborn infant with congenital rubella syndrome, as well as one IgM-positive mother’s serum, made up group 3. In this group, one urine sample, one pharyngeal exudate, and one serum sample were collected 15 days after birth, and one urine sample, one pharyngeal exudate, and one serum sample were collected 37 days after birth. The last urine and serum samples were collected 38 days after birth. Group 4 included 27 pharyngeal exudates and four urine samples from 26 vaccinated children taken between days 10 and 14 after vaccination with rubella, measles, and parotitis vaccines. Group 5 consisted of 19 serum samples (14 were B19V IgM positive, and 5 were B19V IgM negative) from 19 patients affected by an erythema infectiosum outbreak in Soria, Spain, in 1998.

TABLE 1.

Results with clinical samples of MeV, RUBV, and B19V as determined by RTMNPCR

| Virus, group (origin), and specimen type | Total no. | No. positivea | No.negative | IgM resultb | Preservation temp (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeV | |||||

| Group 1 (measles outbreak) | −70 (after several days at −4) | ||||

| Pharyngeal exudates | 5 | 5 | 0 | ||

| Serum | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 Pos | |

| Group 2 (neurological MeV cases) | −20 (frozen and thawed several times) | ||||

| CSF | 22 | 2 | 20 | ||

| Serum | 11c | 0 | 11 | 3 Pos, 5 Neg, 3 ND | |

| Group 4 (vaccinated children) | −70 | ||||

| Pharyngeal exudates | 27 | 0 | 27d | ||

| Urine samples | 4 | 0 | 4 | ||

| RUBV | |||||

| Group 3 (congenital rubella syndrome) | −70 (after several days at −4°C) | ||||

| Newborn pharyngeal exudate | 2 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Newborn serum | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 Pos | |

| Newborn urine | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Mother’s serum | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 Pos | |

| Group 4 (vaccinated children) | −70 | ||||

| Pharyngeal exudate | 27 | 3 | 24d | ||

| Urine samples | 4 | 0 | 4 | ||

| B19 | |||||

| Group 5 (erythema infectiosum), serum | 19 | 16 | 3 | 14 Pos | −20 |

Positive only to the specified virus and negative to the remaining ones.

tPos, positive; Neg, negative; ND, not done.

Four additional samples from this group did not show internal control band (see the text).

Includes one herpes simplex virus sample and one enterovirus sample.

Storing conditions were different for each group of samples: samples from groups 2 and 5 were frozen at −20°C, but samples from group 2 were frozen and thawed an unknown number of times for serological tests, as well as serum from groups 1 and 3. Samples, other than serum, from groups 1, 3, and 4 were stored at −70°C, but samples from group 4 were divided into aliquots and frozen immediately upon arrival at the laboratory. Samples from groups 1 and 3, on the other hand, were kept for several days at 4°C before being frozen.

IgM detection.

Rubella virus- and measles virus-specific IgM antibodies were detected by indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Dade-Behring, Berlin, Germany), while B19V-specific IgM was detected by μ-chain capture ELISA (Biotrin, Dublin, Ireland). Before being tested with indirect methods, the samples were treated with an antihuman IgG (RF Absorbens; Dade-Behring) to remove IgG in order to avoid false positives due to rheumatoid factors. All of the methods were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Isolation in cell culture.

All samples were treated with a mixture of antibiotics and antifungals before inoculation into cell cultures. Urine samples were also neutralized with sodium hydroxide. Then, 200 μl of treated sample was inoculated into each tube. Tubes were preserved with minimal essential medium (Gibco-BRL/Life Technologies, Inc.) plus gentamicin, penicillin, and streptomycin. Samples from group 4 were inoculated in both RK13 and Vero cells. Tubes were monitored for cytophatic effect (CPE) twice a week. After 10 days without CPE, both Vero and RK13 tubes were passed to fresh RK13 cells. Any tube showing CPE and all subcultures after 10 days were monitored for the presence of MeV or RUBV by using immunofluorescence with MeV (Anti-Measles; Biosoft, Paris, France)- and RUBV (Mouse Anti-rubella Monoclonal Antibody; Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, Calif.)-specific monoclonal antibodies, followed by a final immunostaining with fluorescein-labeled anti-mouse conjugate (Anti-Mouse IgG FITC Conjugate; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). RK13 cell supernatants were analyzed by using PCR.

Primer design.

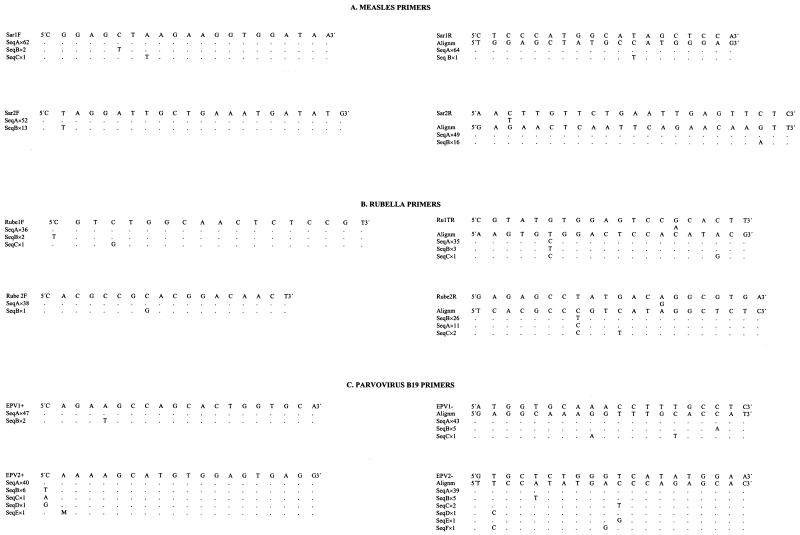

Genomic sequences of the MeV nucleoprotein coding gene, the RUBV E1 glycoprotein gene and the B19V VP1 and VP2 capsid protein genes were obtained from genomic databases. Sequences of the same virus were aligned by using the MEGALIGN application of the DNASTAR (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.) package, and alignments were used for primer design (Fig. 1). Primers were synthesized by a commercial customer service (Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany).

FIG. 1.

Primers. (A) Measles primers. Sar1F and Sar1R are first-reaction primers. Sar2F and Sar2R are second-reaction primers. Both the band size of each pair of primers and the position of each primer following sequence K01711 (Edmonston strain) are given. (B) Rubella primers. Rube1F and Ru1TR are first-reaction primers. Rube2F and Rube 2R are second-reaction primers. Both the band size of each pair of primers and the position of each primer following sequence M15240 (Therien strain) are given. (C) Parvovirus B19 primers. EPV1+ and EPV1− are first-reaction primers. EPV2+ and EPV2− are second-reaction primers. Both the band size of each pair of primers and the position of each primer following sequence N000883 (Gallinella, unpublished) are given. Accession numbers of the sequences used in the alignments and other pertinent data are given below for each virus. For the upper sequences of panel A, the band size was 443 bp (primer Sar1F is between positions 680 and 700 and primer Sar1R is between positions 1105 and 1123). For the lower sequences of panel A, the band size was 229 bp (primer Sar 2F is between positions 851 and 872 and primer Sar2R is between positions 1057 and 1079; position following sequence K01711 (Edmonston strain), Cattaneo 1989). The accession numbers of the sequences included in the alignment were as follows: AF045205, AF045206, AF045207, AF045208, AF045209, AF045210, AF045211, AF045212, AF045213, AF045214, AF045215, AF045216, AF045217, AF045218, D63925, D63927, E04903, K01711, L46728, L46730, L46740, L46744, L46733, L46746, L46748, L46750, L46753, L46756, L46760, L46764, L46758, M89921, M89922, S58435, U01974, U01976, U01977, U01978, U01987, U01988, U01989, U01990, U01991, U01992, U01993, U01994, U01995, U01996, U01998, U01999, U03650, U03653, U03656, U03658, U03661, U03664, U03668, U29317, X01999, X13480, X16566, X16567, X16568, X16569, Z66517. For the upper sequences of panel B, the band size was 380 bp (primer Rube1F is between positions 8745 and 8762 and primer Ru1TR is between positions 9106 and 9125). For the lower sequence of panel B, the band size was 289 (primer Rube2F is between positions 8808 and 8825 and primer Rube2R is between positions 9077 and 9097; position following sequence M15240, Therien strain, Frey 1986). The accession numbers were as follows: AB003337, AB003338, AB003339, AB003340, AB003341, AB003342, AB003343, AB003344, AB003345, AB003346, AB003347, AB003348, AB003349, AB003350, AB003351, AB003352, AB003355, D00156, D50673, D50674, D50675, D50676, D50677, L16228, L16229, L16230, L16231, L16232, L16233, L16234, L16235, L16236, L78917, L19420, L19421, M15240, M30776, X05259, X14871. For the upper sequences of panel C, the band size was 211 bp (primer EPV1+ is between positions 3323 and 3342 and primers EPV1− is between positions 3514 and 3533) For the lower sequences of panel C, the band size was 94 bp (primer EPV2+ is between positions 3366 and 3385 and primer EPV2− is between positions 3440 and 3459; position following complete sequence of strain HV, N000883, Gallinella [unpublished]). The accession numbers were as follows: AB015949, AB015950, AB015951, AB015952, AB015953, AB015959, AB030673, AB030693, AB030694, AF113323, AF161223, AF161224, AF161225, AF161226, AF161228, AF162273, AF221904, AF221905, AF264149, N000883, M13178, U31358, U38506, U38507, U38508, U38509, U38510, U38511, U38512, U38513, U38514, U38515, U38516, U38517, U38518, U38546, U53593, U53594, U53595, U53596, U53597, U53598, U53599, U53600, U53601, Z68146, Z70528, Z70560, Z70599.

Extraction method and specimen treatment.

Genomic material was extracted from clinical samples according to a previously described protocol based on guanidinium thiocyanate extraction and further alcohol precipitation (6). As a part of the internal control system, 500 molecules of a previously described plasmid (7) per ml were also included in the lysis buffer.

RT and amplification.

A coupled RT-amplification reaction was performed by using the Access RT-PCR System kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.). A total of 5 μl of extract was added to a PCR mixture covered with mineral oil containing 3 mM MgSO4; 500 μM concentrations of dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP; 0.5 μM concentrations of measles virus-, rubella virus-, and parvovirus B19-specific primary reaction primers (Fig. 1); 10 μl of AMV/Tfl 5× reaction buffer; 5 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase; and 5 U of Thermus flavus DNA polymerase to a final volume of 50 μl. A pair of primers specific for the internal control plasmid (7) was also included to a final concentration of 0.2 μM in each case. Tubes were placed in an Autocycler Plus Thermocycler (Linus; Cultek S.L.) programmed as follows: 45 min at 48°C for RT and 2 min at 94°C for reverse transcriptase inactivation and cDNA denaturation, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min of denaturation at 93°C, 1 min of annealing at 50°C, and 1 min of elongation at 72°C. Elongation was extended to 5 min in the last cycle.

For the nested reaction, 1 μl of the primary amplification products was added to 49 μl of a new PCR mixture containing 4 mM MgCl2; 500 μM concentrations of dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP; a 0.2 μM concentration of nested instead of primary reaction primers (Fig. 1); a 0.2 μM concentration of internal control-specific nested reaction primers (7), 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer II (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc.), and 0.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Amplitaq DNA Polymerase; Roche Molecular Systems). The thermal program consisted of a first cycle of 2 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, 1 min of annealing at 55°C, and 1 min of elongation at 72°C. Elongation was extended to 5 min in the last cycle. MgCl2, deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and primer concentrations were selected for both primary and nested amplifications as a result of standardization experiments, as well as hybridization and denaturation temperatures.

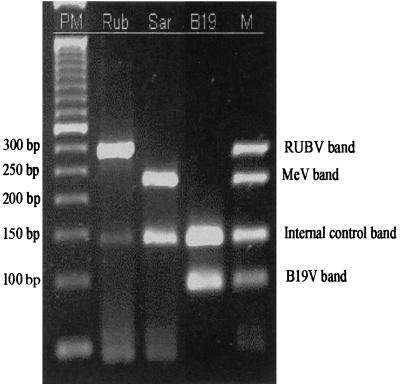

PCR products were visualized and sized by gel electrophoresis in 2% agarose containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide per ml in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer and were visualized under UV light. Expected band sizes were 289 bp for RUBV, 229 bp for MeV, and 94 bp for B19V. Positive samples showed the specific RUBV, MeV, or B19V band and the 140-bp internal control band. When only the internal control band appeared, samples were considered negative. Samples that showed no band were retested, and those that lacked any band after repeat testing were assumed to contain enzyme inhibitors.

Standard precautions were taken to avoid carryover contamination. Pipetting was performed with aerosol-resistant tips, and different biosafety cabinets were used for sample extraction and first amplification or nested amplification. Amplicon detection was performed in a different room.

PCR product cloning.

Primary amplification products from vaccine strains of measles virus and rubella virus, as well as from the laboratory strain of parvovirus B19, were purified by using the GeneClean II kit and were ligated into pGEM-T plasmid vectors with the pGEM-T plasmid vector system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Plasmids were transformed into high-efficiency competent cells (Epicurian coli SL1-Blue; Stratagene Cloning Systems, La Jolla, Calif.) by electroporation. Transformants were selected in Luria broth-ampicillin-IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside-X-Gal) (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) plates, and the presence of the expected insert was confirmed by PCR. Plasmids were purified with the Wizard Plus SV Minipreps kit (Promega). The number of plasmid copies in the final suspensions was estimated by UV spectroscopy at an optical density of 260 nm.

RESULTS

Sensitivity and specificity.

DNA bands of the expected size were obtained for all MeV, RUBV, and B19V viruses (Fig. 2), and no cross-amplification was observed with the other viruses. Serial 10-fold dilution experiments made with vaccine strains comparing PCR with RUBV isolation in RK13 cells, and MeV in B95 cells showed sensitivity rates of 0.04 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) for RUBV and 0.004 TCID50 for MeV.

FIG. 2.

RT-PCR results on gel. Lanes: PM, 50-bp DNA ladder (Gibco-BRL); Rub, RUBV; Sar, MeV; B19, B19V, M, homemade molecular weight with a mix of RUBV, MeV, and B19V amplification products.

In dilution experiments made with plasmids containing inserts of the primary reaction amplification products, PCR was able to detect as few as 10 molecules for MeV and RUBV and 1 molecule for B19V.

Clinical specimens.

All five pharyngeal exudates from measles patients were MeV positive, whereas all four serum samples were negative in group 1 (Table 1). MeV RNA was detected in 2 of 22 CSF samples from group 2, but no amplification was obtained with any of the 11 sera. Two pharyngeal exudates taken 15 and 37 days after birth and one urine taken 37 days after birth from the case of congenital rubella syndrome (group 3) showed the presence of RUBV RNA. As in the case of MeV, no amplification was obtained with any serum. RUBV was detected in three pharyngeal exudates of 27 postvaccinated children from group 4. One of them was positive by culture, another was negative, and the third could not be cultured due to contamination. All children were negative for MeV. Finally, B19V DNA was detected in 16 of 19 sera from patients with erythema infectiosum (group 5); 14 of these 19 sera were positive for parvovirus B19 IgM, 1 was undetermined, and 4 were IgM negative.

Four sera from group 1 and four sera from group 2 lacked of internal control band in PCR screening. All four sera from group 1 were negative on repetition, three sera from group 2 could not be tested again, while the remaining one did not show internal control band on repetition and, consequently, the presence of inhibitors was suspected. These last four samples were not considered for analysis and are not shown in Table 1).

DISCUSSION

The multiplex PCR described here has been shown to be able to detect RNA from MeV and RUBV, as well as DNA from B19V in one single reaction. Although several studies describing individual PCR methods can be found for each virus (3, 9, 12, 13, 15, 16, 19, 22–25, 30, 31, 33, 37–39, 41, 45), no one has been able to detect all of these simultaneously. Nested PCR has allowed us to achieve very high sensitivity versus virus isolation in cell cultures, as well as in cDNA plasmid dilution experiments. Sensitivity is critical for diagnosis, especially for certain samples that usually contain small amounts of virus, as is the case of spinal fluid. The high sensitivity showed in these experiments correlated with the results obtained for pharyngeal exudates from a measles outbreak, as well as with pharyngeal exudates and urine samples from a congenital rubella case and serum samples from an erythema infectiosum outbreak. All of these results concur with previous studies (3, 9, 13, 19, 22–25, 30, 31, 33, 37–39, 41, 45). The recovery rates of RV in pharyngeal samples after vaccination with attenuated virus was poor but were similar to those previously observed in other studies (3). However, our viral detection rate for serum samples from measles and rubella cases, as well as for spinal fluids from MeV-related neurological diseases, was lower than expected compared to some published data (26, 29, 30). Nevertheless, another work concludes that MeV RNA amplification from sera is infrequent, especially after the first week of symptoms (35). RNA degradation due to improper storage could also account for these poor results, since all of these serum samples were stored at −20°C for many years and were frozen and thawed an unknown number of times. In contrast, the PCR-positive pharyngeal exudates and urine samples from these same cases were stored at −70°C and remained frozen until PCR testing. However, Kreis and Schoub (26) obtained three positive results in 14 sera with similar characteristics. Further analysis with fresh samples is required to establish the ability of the technique described here to detect MeV and RUBV in serum and spinal fluid.

Since the target plasmid for the internal control system used here was included in the lysis buffer, this must be carried out during the whole extraction procedure, enabling detection of handling errors. This is very important, since pellets are frequently not apparent and could be easily discarded with the supernatants in precipitation steps. Moreover, the use of a limited number of plasmid molecules makes it possible to monitor the presence of any factor affecting the sensitivity of the reaction in any individual tube. Consequently, the possibility of false negatives is significantly reduced by the use of this internal control system.

In conclusion, the multiplex PCR method described here is useful for the diagnosis of viral exanthematic diseases as a complement of IgM detection, which remains the method of choice for these three viruses. Nevertheless, RTMNPCR is especially indicated for monitoring measles eradication plans, since it enables not only detection of samples with available measles RNA for genotyping but also provides differential diagnosis for the most common exanthematic viruses, without any additional cost. Since most countries are using a combined vaccine for rubella, measles, and mumps, rubella prevalence is expected to be dramatically decreased along with measles eradication. Consequently, additional studies are needed to establish the best composition of multiplex PCR methods for the diagnosis of viral exanthemes in the future.

Acknowledgments

This study was undertaken at the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, partly during a stay by the first author, who belonged to the staff of the Microbiology Unit of the Nuestra Señora del Pino Hospital in Las Palmas (Gran Canaria, Canary Islands). The study also received financial support from a fellowship from the Spanish Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bellini, W. J., and P. A. Rota. 1998. Genetic diversity of wild-type measles viruses: implications for global measles elimination programs. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 4:29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolognia, J., and I. M. Braverman. 1994. Skin manifestations of internal disease, p.300. In K. J. Isselbacher, E. Braunwald, J. D. Wilson, J. B. Martin, A. S. Fauci, and D. L. Kasper (ed.), Principles of internal medicine, 13th ed., vol. 1. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, NY.

- 3.Bosma, T. J., K. M. Corbett, S. O’Shea, J. E. Banatvala, and J. M. Best. 1995. PCR for detection of rubella virus RNA in clinical samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1075–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlson, J., H. Artsob, M. Douville-Fradet, P. Duclos, M. Fearon, S. Ratnam, G. Tipples, P. Varughese, B. Ward, and J. Sciberras. 1998. Measles surveillance: guidelines for laboratory support. Working Group on Measles Elimination. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 24:33–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carriere, C., P. Boulanger, and C. Delsert. 1993. Rapid and sensitive method for the detection of B19 virus DNA using the polymerase chain reaction with nested primers. J. Virol. Methods 44:221–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casas, I., L. Powell, P. E. Klapper, and G. M. Cleator. 1995. New method for the extraction of viral RNA and DNA from cerebrospinal fluid for use in the polymerase chain reaction assay. J. Virol. Methods 53:25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casas, I., A. Tenorio, J. M. Echevarria, P. E. Klapper, and G. M. Cleator. 1997. Detection of enteroviral RNA and specific DNA of herpesviruses by multiplex genome amplification. J. Virol. Methods 66:39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassinotti, P., G. Burtonboy, M. Fopp, and G. Siegl. 1997. Evidence for persistence of human parvovirus B19 DNA in bone marrow. J. Med. Virol. 53:229–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassinotti, P., M. Weitz, and G. Siegl. 1993. Human parvovirus B19 infections: routine diagnosis by a new nested polymerase chain reaction assay. J. Med. Virol. 40:228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control. 1998. Advances in global measles control and elimination: summary of the 1997 international meeting. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 47:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control. 1999. Global measles control and regional elimination, 1998–1999. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 48:1124–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chadwick, N., I. Bruce, M. Davies, B. van Gemen, R. Schukkink, K. Khan, R. Pounder, and A. Wakefield. 1998. A sensitive and robust method for measles RNA detection. J. Virol. Methods 70:59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clewley, J. P. 1989. Polymerase chain reaction assay of parvovirus B19 DNA in clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:2647–2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Ory, F., M. E. Guisasola, A. Téllez, and C. E. Domingo. 1996. Comparative evaluation of commercial methods for the detection of parvovirus B19-specific immunoglobulin M. Serodiagn. Immunother. Infect. Dis. 8:117–120. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durigon, E. L., D. D. Erdman, G. W. Gary, M. A. Pallansch, T. J. Torok, and L. J. Anderson. 1993. Multiple primer pairs for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of human parvovirus B19 DNA. J. Virol. Methods 44:155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eggerding, F. A., J. Peters, R. K. Lee, and C. B. Inderlied. 1991. Detection of rubella virus gene sequences by enzymatic amplification and direct sequencing of amplified DNA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:945–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erdman, D. D., E. L. Durigon, and B. P. Holloway. 1994. Detection of human parvovirus B19 DNA PCR products by RNA probe hybridization enzyme immunoassay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2295–2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frey, T. K. 1997. Neurological aspects of rubella virus infection. Intervirology 40:167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fridell, E., A. N. Bekassy, B. Larsson, and B. M. Eriksson. 1992. Polymerase chain reaction with double primer pairs for detection of human parvovirus B19 induced aplastic crises in family outbreaks. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 24:275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffin, D. E., and W. J. Bellini. 1996. Measles virus, p.1267–1312. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed., vol. 1. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 21.Helfand, R. F., J. L. Heath, L. J. Anderson, E. F. Maes, D. Guris, and W. J. Bellini. 1997. Diagnosis of measles with an IgM capture EIA: the optimal timing of specimen collection after rash onset. J. Infect. Dis. 175:195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hornsleth, A., K. M. Carlsen, L. S. Christensen, M. Gundestrup, E. D. Heegaard, and J. Myhre. 1994. Estimation of serum concentration of parvovirus B19 DNA by PCR in patients with chronic anaemia. Res. Virol. 145:379–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho-Terry, L., G. M. Terry, and P. Londesborough. 1990. Diagnosis of foetal rubella virus infection by polymerase chain reaction. J. Gen. Virol. 71:1607–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koch, W. C., and S. P. Adler. 1990. Detection of human parvovirus B19 DNA by using the polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:65–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovacs, B. W., D. E. Carlson, B. Shahbahrami, and L. D. Platt. 1992. Prenatal diagnosis of human parvovirus B19 in nonimmune hydrops fetalis by polymerase chain reaction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 167:461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreis, S., and B. D. Schoub. 1998. Partial amplification of the measles virus nucleocapsid gene from stored sera and cerebrospinal fluids for molecular epidemiological studies. J.Med. Virol. 56:174–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurtzman, G. J., B. J. Cohen, A. M. Field, R. Oseas, R. M. Blaese, and N. S. Young. 1989. Immune response to B19 parvovirus and an antibody defect in persistent viral infection. J. Clin. Investig. 84:1114–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liebert, U. G. 1997. Measles virus infections of the central nervous system. Intervirology 40:176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuzono, Y., M. Narita, N. Ishiguro, and T. Togashi. 1994. Detection of measles virus from clinical samples using the polymerase chain reaction. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 148:289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakayama, T., T. Mori, S. Yamaguchi, S. Sonoda, S. Asamura, R. Yamashita, Y. Takeuchi, and T. Urano. 1995. Detection of measles virus genome directly from clinical samples by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction and genetic variability. Virus Res. 35:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patou, G., D. Pillay, S. Myint, and J. Pattison. 1993. Characterization of a nested polymerase chain reaction assay for detection of parvovirus B19. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:540–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramsay, M. 1997. Strategic plan for the elimination of measles in the European Region. Seventh meeting of national programme managers. World Health Organization, Berlin, Germany.

- 33.Revello, M. G., F. Baldanti, A. Sarasini, M. Zavattoni, M. Torsellini, and G. Gerna. 1997. Prenatal diagnosis of rubella virus infection by direct detection and semiquantitation of viral RNA in clinical samples by reverse transcription-PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:708–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Revello, M. G., A. Sarasini, F. Baldanti, E. Percivalle, D. Zella, and G. Gerna. 1997. Use of reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction for detection of rubella virus RNA in cell cultures inoculated with clinical samples. New Microbiol. 20:197–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riddell, M. A., D. Chibo, H. A. Kelly, M. G. Catton, and C. J. Birch. 2001. Investigation of optimal specimen type and sampling time for detection of measles virus RNA during a measles epidemic. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:375–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saldanha, J., and P. Minor. 1997. Collaborative study to assess the suitability of a proposed working reagent for human parvovirus B19 DNA detection in plasma pools by gene amplification techniques. B19 Collaborative Study Group. Vox Sang 73:207–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwarz, T. F., G. Jager, W. Holzgreve, and M. Roggendorf. 1992. Diagnosis of human parvovirus B19 infections by polymerase chain reaction. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 24:691–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sevall, J. S. 1990. Detection of parvovirus B19 by dot-blot and polymerase chain reaction. Mol. Cell. Probes 4:237–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimizu, H., C. A. McCarthy, M. F. Smaron, and J. C. Burns. 1993. Polymerase chain reaction for detection of measles virus in clinical samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:1034–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soderlund, M., R. von Essen, J. Haapasaari, U. Kiistala, O. Kiviluoto, and K. Hedman. 1997. Persistence of parvovirus B19 DNA in synovial membranes of young patients with and without chronic arthropathy. Lancet 349:1063–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanemura, M., K. Suzumori, Y. Yagami, and S. Katow. 1996. Diagnosis of foetal rubella infection with reverse transcription and nested polymerase chain reaction: a study of 34 cases diagnosed in foetuses. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 174:578–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas, H. I., E. Barrett, L. M. Hesketh, A. Wynne, and P. Morgan-Capner. 1999. Simultaneous IgM reactivity by EIA against more than one virus in measles, parvovirus B19 and rubella infection. J. Clin. Virol. 14:107–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolinsky, J. S. 1996. Rubella, p.899–929. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed., vol. 1. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 44.World Health Organization. 1998. Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI). Standardisation of the nomenclature for describing the genetic characteristics of wild-type measles viruses. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 73:265–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamakawa, Y., H. Oka, S. Hori, T. Arai, and R. Izumi. 1995. Detection of human parvovirus B19 DNA by nested polymerase chain reaction. Obstet. Gynecol. 86:126–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young, N. S. 1996. Parvoviruses, p.2199–2220. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed., vol. 1. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa.