Abstract

Microglia play a dual role in neuroinflammatory disorders that affect millions of people worldwide. These specialized cells are responsible for the critical clearance of debris and toxic proteins through endocytosis. However, activated microglia can secrete pro-inflammatory mediators, potentially exacerbating neuroinflammation and harming adjacent neurons. TREM2, a cell surface receptor expressed by microglia, is implicated in the modulation of neuroinflammatory responses. In this study, we investigated if and how Dehydroervatamine (DHE), a natural alkaloid, reduced the inflammatory phenotype of microglia and suppressed neuroinflammation. Our findings revealed that DHE was directly bound to and activated TREM2. Moreover, DHE effectively suppressed the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, restored mitochondrial function, and inhibited NLRP3 inflammasome activation via activating the TREM2/DAP12 signaling pathway in LPS-stimulated BV2 microglial cells. Notably, silencing TREM2 abolished the suppression effect of DHE on the neuroinflammatory response, mitochondrial dysfunction, and NF-κB/NLRP3 pathways in vitro. Additionally, DHE pretreatment exhibited remarkable neuroprotective effects, as evidenced by increased neuronal viability and reduced apoptotic cell numbers in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells co-cultured with LPS-stimulated BV2 microglia. Furthermore, in our zebrafish model, DHE pretreatment effectively alleviated behavioral impairments, reduced neutrophil aggregation, and suppressed neuroinflammation in the brain by regulating TREM2/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathways after intraventricular LPS injection. These findings provide novel insights into the potent protective effects of DHE as a promising novel TREM2 agonist against LPS-induced neuroinflammation, revealing its potential therapeutic role in the treatment of central nervous system diseases associated with neuroinflammation.

Keywords: Neuroinflammation; 19,20-Dehydroervatamine; TREM2; NF-κB; NLRP3

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Neuroinflammation is a significant pathophysiological process implicated in the etiology and progression of various neurological disorders, including encephalitis and neurodegenerative diseases [1]. Microglia, the resident macrophages within the brain parenchyma, are integral to the neuroinflammatory response in the central nervous system (CNS) [2]. Persistent and excessive activation of microglia leads to the secretion and accumulation of various neurotoxic factors, which can trigger neuroinflammation and exacerbate the progression of neural disease [3]. Given the limited availability of effective pharmacological treatments for CNS diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), exploring agents that target neuroinflammation may provide valuable insights for developing novel therapeutic interventions.

The triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) is highly specific and predominantly expressed by microglia [4]. It contains a transmembrane domain, a short cytoplasmic tail, and an ectodomain [5]. TREM2 has been associated with a variety of cellular functions, including phagocytosis of apoptotic neuronal cells, regulation of inflammatory cytokine production, and the modulation of cellular proliferation and survival [6]. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a critical component of the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria, acts as an activator of the Toll-like receptors (TLRs). Additionally, certain bacterial LPS can serve as an exogenous ligand for TREM2, activating it to attenuate the TLR response, which ultimately suppresses pro-inflammatory reactions [7]. While it is generally accepted that TREM2 exerts an anti-inflammatory effect, the relationship between TREM2 and inflammatory responses is complex. In acute inflammatory responses, TREM2 deficiency has been shown to increase the levels of proinflammatory cytokines [8]. Conversely, overexpressing TREM2 in P301S tau transgenic mouse models reduces the levels of proinflammatory transcripts [9]. However, in chronic and sustained inflammatory responses, TREM2 seems to amplify or promote inflammation. Chronic enhancement of TREM2 signaling has been associated with sustained microglial activation and exacerbation of Aβ-induced tau spreading in an AD mouse model [10]. Therefore, several studies have supported that TREM2 function appears protective during the early stages of neurodegenerative disease [11]. Regardless, these results amply demonstrated that TREM2 can regulate neuroinflammation and inflammatory-mediated neurodegenerative disease. Furthermore, the development of TREM2-targeted antibodies aimed at stimulating TREM2 activation has shown promising effects on microglial function and neuroinflammation [12,13]. Thus, targeting TREM2 activation represents a novel therapeutic strategy for neuroinflammation and neural inflammation-associated CNS diseases.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen have been proven to possess neuroprotective properties; however, long-term NSAID treatment may result in adverse effects [14]. Monoterpene indole alkaloids (MIAs) are abundantly distributed in plants, many of which have demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects [15]. Notably, two widely recognized MIAs, brucine (aspidosperma-type MIAs) and hirsutine (corynantheine-type MIAs), have exhibited anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective activities in rat models [16,17]. 19,20-dehydroervatamine (DHE) and 20-epiervatamine are typical corynantheine-type MIAs found in Tabernaemontana bovina Lour., while their biological activities remain unclear. T. bovina has a long-standing traditional use in the treatment of sore throats, dentalgia, and diarrhea in Guangdong Province, China [18]. In India, T. bovina leaf juice is applied to wounds due to its anti-inflammatory and hemostatic properties [19,20]. Recent pharmacological investigations indicate that MIAs in T. bovina exhibit potential anti-inflammatory properties in LPS-stimulated microglial cells and neuroprotective effects against Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease [[21], [22], [23]]. Based on accumulating evidence supporting the anti-inflammatory efficacy of MIAs in T. bovina, we hypothesize that DHE and 20-epiervatamine may exert an anti-neuroinflammatory effect by suppressing microglial inflammation, thereby reducing the death of neurons.

In the present study, we employed BV2 microglia cells to evaluate the anti-neuroinflammatory potential of DHE and 20-epiervatamine, ultimately selecting DHE for further efficacy and mechanism exploration. The purpose of this study was to investigate the protective effect of DHE against LPS-induced neuroinflammation in BV2 microglial cells and in a zebrafish model. This included investigating the role of DHE in LPS-stimulated microglial hyperactivation and neuronal damage, as well as elucidating the underlying mechanisms involved.

Materials and Methods

Materials

An immortalized mouse BV2 microglial cell line was acquired from the Kunming Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection, Kunming Institute of Zoology. Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Lipopolysaccharide (Escherichia coli 055: B5) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). ELISA kit for PGE2 was obtained from MyBioSource, Inc. (San Diego, USA). Antibody for TREM2 was purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, USA); iNOS, TNF-α, COX-2, DAP12, p-IKKα/β, IKKα, p-IκBα, IκBα, p–NF–κB (p65), NF-κB (p65), NLRP3, ASC, Caspase 1 p20, IL-1β, and PINK1 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA); P62 was purchased from Proteintech, Inc. (Wuhan, China); Parkin and MAP LC3 Ⅰ/Ⅱ were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Texas, USA); Iba1 was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). The primary antibodies were diluted to a 1:1000 ratio for their application in the following Western Blot experiments. HRP-labeled Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L), HRP-labeled Goat Anti-Mouse IgG(H + L), Donkey Anti-Goat IgG(H + L) secondary antibodies, JC-1 probe, and dichloro-dihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) probe were purchased from the Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit was purchased from Meilunbio, Inc. (Dalian, China). DHE and 20-epiervatamine were dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO), stored at −20 °C, and diluted in the medium just before use. The final concentration of DMSO in samples was always ≤0.1 % (v/v). The medium containing the compound was freshly prepared for each treatment. The purity of both DHE and 20-epiervatamine was determined to be 98 % by HPLC analysis.

Cell culture

The BV2 microglial and SH-SY5Y cells were maintained as previously reported [24,25]. Briefly, cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10 % FBS and 1 % PS (v/v) at 37 °C under a 5 % CO2 atmosphere. The BV2 microglial cells were exposed to appropriate concentrations of DHE or 20-epiervatamine for 1 h prior to LPS stimulation (800 ng/ml).

Zebrafish maintenance and experimental design

Tg(Mpo:EGFP) line and AB wild-type zebrafish were purchased from the Zebrafish International Resource Center (University of Oregon, USA) and maintained as described in the Zebrafish Handbook [26]. Briefly, the embryos were collected and maintained in embryo medium (540 μM KCl, 13.7 mM NaCl, 25 μM Na2HPO4, 44 μM KH2PO4, 300 μM CaCl2, 0.1 mM MgSO4, and 42 μM NaHCO3; PH 7.4) at a temperature of 28.5 °C. Zebrafish larvae were treated with different concentrations of DHE at 4 days post-fertilization (4 dpf). After 24 h, zebrafish mortality was assessed based on heartbeat analysis, and survival rates were calculated. Subsequently, 4 dpf zebrafish larvae were immersed in DHE for 24 h. The zebrafish was subsequently microinjected with 1 nl of 1x PBS or 2.5 mg/ml LPS into the brain optic tectum at 5 dpf, following anesthesia with 0.02 % (w/v) tricaine. After 24 h, the 6-dpf larvae were transferred to individual wells of a 96-well plate, with one larva per well. The injection did not have negative effects on the brains of the zebrafish larvae (Fig. S1). AB wild-type zebrafish locomotion behavior was observed using a zebrafish tracking system (ViewPoint Behavior Technology) for a duration of 30 min. The ethical approval for the animal experiments was granted by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of the University of Macau (Permit No. UMARE-021b-2020).

Cell viability assay

BV2 cells were treated with DHE or 20-epiervatamine, or SH-SY5Y cells were treated with LPS or DHE for 24 h. Then the cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/ml MTT solution (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 h. Finally, the absorbance was determined at 540 and 690 nm using a microplate reader (Dynatec MR-7000; Dynatec Laboratories Inc., El Paso, TX, USA).

Nitrite quantification assay

The BV2 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells per well and incubated overnight. Cells were pre-treated with various concentrations of DHE or 20-epiervatamine for 1 h and then treated with LPS (800 ng/ml) for 24 h. The culture medium was collected, and the NO level was measured by Griess reagent (Biyuntian Biotech, Shanghai, China).

Molecular docking

It was possible to get the crystal structure of TREM2 (PDB ID: 5ELI) from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/). ChemDraw 20.0 was used to generate the 2D structure of DHE and 20-epiervatamine, which was then converted into a 3D structure and optimized using Chem3D 20.0. Molecular docking was carried out by AutoDock Vina (v1.2.3) using the binding degree evaluation criteria from previous research [27]. PyMOL (v2.3.0) and Discovery Studio (v21.1.0) were used to visualize and analyze the best binding pose.

Cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA)

Engagement between DHE or 20-epiervatamine in cells was examined by a cellular thermal shift assay. Samples were prepared for the drug-exposed and control groups. After treatment with DHE, 20-epiervatamine, or DMSO for 1 h, cells were washed, resuspended with PBS, and dispensed to 100 μL aliquots. Samples were heated at 37 °C, 41 °C, 45 °C, 49 °C, 53 °C, 57 °C, 61 °C, 65 °C, or 69 °C for 3 min, followed by cooling for 3 min at room temperature. Lastly, the heated lysates were collected and subjected to Western blot analysis.

Cell transfection with shRNA

In this experiment, a lentiviral vector expressing mouse TREM2-shRNA was synthesized by IGEBIO (Guangzhou, China). The sequence of the shRNA that targets TREM2 is 5′-GGAATCAAGAGACCTCCTTCC-3'. The scrambled RNA sequence used as a control has the following sequence: 5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3'. Briefly, BV2 cells were cultured on 6-well plates until 60–70 % confluent for transfection. Then, shRNA was transfected into cells for 48 h using Lipofectamine® 8000 reagent (Invitrogen) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. After that, transfected cells were treated with 25 μM DHE and/or LPS for another 24 h.

ELISA assay

Cells were plated, cultured, and treated as described above. The culture supernatants were collected, and the concentrations of PGE2 (#MBS2662, MyBioSource, Inc.), TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 (#88–7324, #88–7064, and #88–7105, respectively, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the culture medium were quantified by using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Zebrafish samples were prepared by anesthetizing larvae with 0.02 % (w/v) tricaine. Head segments of the larvae, excluding the eyes and yolk sacs, were dissected (30 larvae per group). The total RNA from cells and zebrafish head tissues (excluding the eyes and yolk sac) was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Subsequently, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using Evo M -MLV RT Premix (Accurate Biotechnology (Hunan) Co.). PCR was carried out using the SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II kit. The cDNA of cell samples and zebrafish samples was amplified by PCR with specific primers, as shown in Table S1 and Table S2, respectively. Each cellular sample was normalized to the levels of β-actin protein. For zebrafish samples, mRNA abundance was normalized to elongation factor 1 α (ef1a) levels.

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from BV2 microglial cells and the head portion of larvae without the eye and yolk sac regions (30 larvae per group) using RIPA buffer containing PMSF and a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. The protein concentration was quantified, then 30 μg of total proteins were separated by 10 % SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and then incubated with specific primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After being incubated with HRP-linked secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, the proteins were visualized using an ECL advanced Western blotting detection kit.

Immunofluorescence assay

Cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 3.7 % paraformaldehyde for 20 min, permeabilized with 0.2 % Triton X-100, and blocked with 2 % bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h. After that, the cells were sequentially incubated with rabbit anti–NF–κB p65 antibody at 4 °C overnight, then incubated with secondary antibodies and DAPI at room temperature, and imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Leica).

Determination of mitochondrial membrane potential

Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was assayed using a fluorescent probe JC-1 (5, 5′, 6, 6′-tetrachloro-1, 1′, 3, 3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine iodide) following the manufacturer's protocol. BV2 cells were incubated with 10 μg/ml JC-1 for 30 min at 37 °C, washed with PBS, and resuspended for flow cytometric analysis.

Measurement of intracellular ROS generation

The intracellular ROS concentration of BV2 cells and zebrafish was detected using a DCFH-DA probe, as instructed by the manufacturer. The treated cells were washed with PBS and incubated with 10 μM DCFH-DA at 37 °C for 30 min. Then the cells were washed with PBS and resuspended for flow cytometry analysis (CytoFLEX Flow Cytometer; Beckman Coulter). Besides, for zebrafish, DCFH-DA (10 μM) was administered to larvae and incubated for 30 min in the dark at 28.5 °C. After washing with medium three times, larvae were visualized by Leica M205 FA fluorescence stereo microscopes (Leica mirosysterms Co., Wetzlar, Germany), and the images were analyzed by ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). In the quantitative image analysis, images are processed with an appropriate computational threshold to calculate the average fluorescence intensity within the region of interest (ROI), which encompassed the entire larval body. The image analysis workflow was partially automated, with algorithms facilitating segmentation and minimizing the requirement for manual adjustments to the ROI size or position. Subsequently, the average fluorescence intensity among different groups was compared.

Immunofluorescence assay

In brief, cells were washed, fixed, permeabilized, and blocked. After that, the cells were sequentially incubated with rabbit anti-p65 antibody (1:500; Cell Signaling Technology) at 4 °C overnight. Then, cells were incubated with secondary antibodies and DAPI at room temperature. Finally, the samples were imaged using the DMi8 inverted fluorescent microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Neuroprotective assay and apoptosis detection

SH-SY5Y (1 × 104 cells/well) or BV2 cells (1 × 104 cells/well) were seeded in 96-well plates and allowed to adhere for 24 h prior to treatments. Subsequently, BV2 cells were pre-treated with different concentrations of DHE (6–25 μM) for 1 h before the addition of LPS (800 ng/ml) for 24 h. The supernatant was then collected and transferred to SH-SY5Y cell cultures, which were incubated for another 24 h. Finally, the cell viability of the SH-SY5Y cells was evaluated using the MTT assay.

BV2 cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were seeded onto a poly-lysine-coated 0.4 μm porous insert on the upper chamber of transwell permeable supports, and SH-SY5Y cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were cultured on the bottom of the 24-well plate (Corning Inc.). In coculture conditions, BV2 cells were treated with various concentrations of DHE for 1 h before LPS stimulation and coculturing with SH-SY5Y cells for 24 h. Subsequently, the SH-SY5Y cells were incubated for 15 min in the dark with 10 μL of propidium iodide and 5 μL of FITC-labeled Annexin V. Cell apoptosis was measured using a flow cytometer, and the proportions (%) of apoptosis cells were quantified by FlowJo software.

Fluorescent colocalization of mitophagolysosomes

In brief, BV2 cells were pre-treated with different concentrations of DHE for 1 h and then exposed to LPS for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were stained with Lyso-Tracker Red (C1046, Beyotime, China) and Mito-Tracker Green (C1048, Beyotime, China), followed by counterstaining with Hoechst 33,342, all in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Microglia were then washed 3 times with PBS and observed under a confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP8, Germany).

Data and statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (Graphpad Software Inc.). The data were presented as mean ± SD. The Shapiro-Wilk method was used to evaluate the normality of the data, which confirmed that it followed a normal distribution. The comparisons among multiple groups were performed with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the post-hoc Dunnett and Tukey tests. ∗/#p < 0.05, ∗∗/##p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗/###p < 0.001 were considered statistically significant.

Results

DHE directly bound to TREM2 to inhibit LPS-induced NO production in BV-2 microglial cells

Two corynantheine-type alkaloids, DHE and 20-Epiervatamine (Fig. 1A-A′), were extracted, separated, and identified from T. bovina (Figs. S2–S3). Cellular toxicity assays showed that DHE (25 μM) and 20-Epiervatamine (12 μM) displayed no significant cytotoxicity in BV2 cells (Fig. S4). The anti-inflammatory effects of DHE and 20-Epiervatamine were further assessed by measuring nitric oxide (NO) released from activated microglia. Results highlighted that LPS administration significantly elevated NO levels, whereas both DHE and 20-Epiervatamine substantially reduced NO production in a dose-dependent manner. Notably, DHE exhibited greater potency in suppressing NO production, achieving a 90 % inhibition rate at 25 μM, compared to a 62 % reduction by 20-epiervatamine at 12 μM (Fig. 1B-B’).

Fig. 1.

DHE directly bound to TREM2 to inhibit LPS-induced NO production in BV-2 microglial cells. (A, A′) Chemical structure of DHE and 20-Epiervatamine. (B, B′) The production of NO in the cell culture supernatant was determined by the Griess reagent assay; n = 4. (C, C′) Molecular docking of DHE (C) or 20-Epiervatamine (C′) to TREM2. (D) CETSA was carried out as described above. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. Representative images are shown. (E) The average Tm value of 6, 12, and 25 μM of DHE and 12 μM of 20-Epiervatamine. (F–I) The CETSA curves of TREM2 in BV2 cells were determined in the absence and presence of DHE (6, 12, and 25 μM) or 20-Epiervatamine (12 μM). Each band intensity of TREM2 was normalized with respect to that obtained at 37 °C. n = 3–4. Data are presented as mean ± SD analyzed by one-way ANOVA. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 vs. the LPS-treated group; ###p < 0.001 vs. the control group.

Emerging evidence indicates that TREM2 expression by brain microglia can improve microglial phagocytosis ability and reduce inflammation [28]. Therefore, we explored whether DHE or 20-Epiervatamine could potentially target TREM2. Molecular docking analysis revealed a higher binding energy for DHE with TREM2 (−7.3 kcal/mol) compared to 20-epiervatamine (−6.8 kcal/mol). Moreover, two hydrogen bonds were formed between the oxygen of DHE and the side chains of Arg47 and Arg77 of TREM2 (Fig. 1C-C’). Furthermore, CETSA analysis demonstrated that the thermostability of TREM2 in the DHE or 20-Epiervatamine group was higher than that in the control group. Notably, the addition of 12 μM DHE stabilized the Tm value of TREM2 by 9.2 °C but only by 5.4 °C with 12 μM 20-Epiervatamine (Fig. 1D–I). These collective findings suggest a stronger binding affinity of DHE for TREM2, leading to its selection for further investigation into its potential anti-neuroinflammatory effects.

DHE suppressed LPS-induced activation of proinflammatory mediators and prevented the release of inflammatory cytokines by targeting TREM2

As shown in Fig. 2A, LPS alone significantly increased the secretion of PGE2, while DHE dose-dependently decreased LPS-induced PGE2 production. Additionally, the increases in both protein and mRNA levels of iNOS and COX-2 induced by LPS were effectively suppressed by pretreatment with DHE (Fig. 2B–E). Furthermore, DHE inhibited the secretion and expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6), while enhancing the production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (Fig. 2F–H). Subsequently, we explored whether the binding of TREM2 enhances the anti-neuroinflammatory activity of DHE. The result showed that LPS did not markedly activate TREM2 and DAP12 expression, which were significantly improved by treatment with DHE (Fig. 2I–J). Transfection with TREM2 shRNA in BV2 cells markedly knocked down the expression of TREM2 and DAP12 compared to the control-shRNA group (Fig. 2K-L). Further examination of TREM2-deficient BV2 microglial cells revealed that TREM2-shRNA significantly increased the production of NO and the expressions of TNF-α and IL-6, all of which were attenuated by DHE (Fig. 2M − O). Conversely, the expression of IL-10, which was elevated by DHE, decreased in TREM2-deficient cells (Fig. 2P).

Fig. 2.

DHE suppressed LPS-induced activation of proinflammatory mediators and prevented the release of inflammatory cytokines by targeting TREM2. Cells were pretreated with DHE for 1 h and then exposed to LPS for another 24 h. (A) PGE2 production was determined by ELISA; n = 4. (B, D) The mRNA levels of iNOS and COX-2 were detected by RT-PCR analysis; n = 3. (C, E) Protein levels of iNOS and COX-2 were measured by Western blot analysis; n = 3. (F) Secretion levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 in the cell culture medium were determined by relative ELISA; n = 4. (G) The mRNA levels of TNF-α and IL-6 were assessed by RT-PCR analysis; n = 3. (H) Protein levels of TNF-α were evaluated by Western blot analysis; n = 3. TREM2 (I) and DAP 12 (J) protein expression were detected by Western blot analysis and quantified by ImageJ. After TREM2 was knocked down using shRNA, microglial cells were treated with DHE in the presence or absence of LPS to determine TREM2 (K) and DAP12 (L) protein expression levels. The supernatant of BV2 cells was then used to measure NO production (M), TNF-α (N), IL-6 (O), and IL-10 (P) via Griess reagent and ELISA assay, respectively; n = 3–4. Data are presented as the mean ± SD analyzed by one-way ANOVA. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 vs. the LPS-treated group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, and ###p < 0.001 vs. the control group; N.S. = not significant.

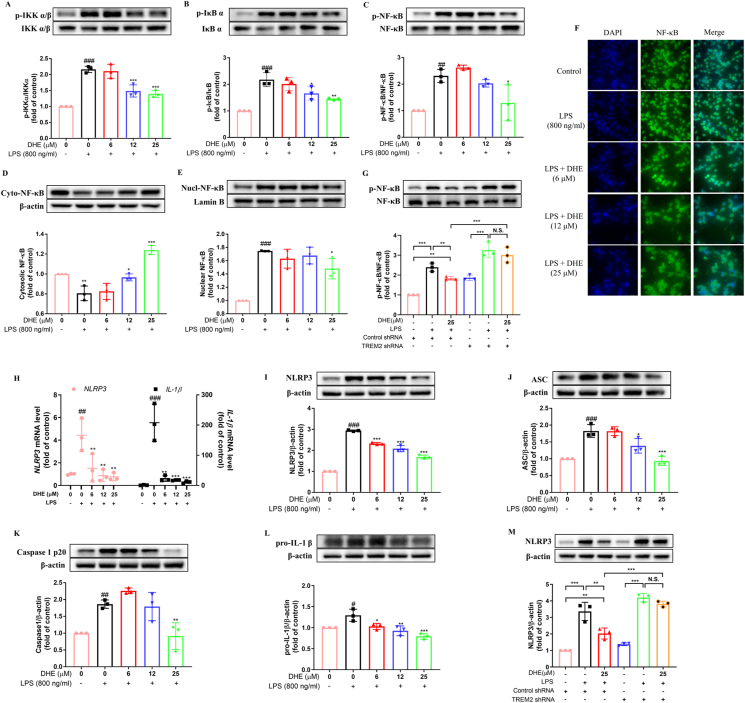

DHE inhibited the activation of NF-κB signaling and the NLRP3 inflammasome in LPS-treated BV2 microglial cells by targeting TREM2

The researchers have proved that activation of NF-κB triggers the transcription of NLRP3 and that TREM2 mitigates neuroinflammation by regulating mitophagy and the NLRP3 inflammasome in mice [29,30]. Thus, we investigated the effects of DHE on the activation of the NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway. The findings indicated that LPS exposure resulted in a notable increase in the phosphorylation of IKKα/β, IκBα, and NF-κB, whereas pretreatment with DHE dramatically decreased their expression levels (Fig. 3A–C). Additionally, Western blot analysis and immunofluorescence analysis indicated that the protein levels of NF-κB p65 in the nucleus were considerably elevated, while the cytoplasmic levels were remarkably decreased following LPS administration in microglial cells. This trend was significantly reversed by pretreatment with DHE (Fig. 3D–F). However, the administration of TREM2-shRNA effectively abolished the inhibitory effects of DHE on NF-κB expression (Fig. 3G). In addition, the mRNA expression of NLRP3 and IL-1β, as well as the protein levels of NLRP3, ASC, cleaved caspase-1, and downstream pro-IL-1β, were significantly increased in response to LPS stimulation. Treatment with DHE, however, obviously reduced NLRP3 and IL-1β mRNA expression. Equally, DHE also dramatically reduced the protein expression levels of NLRP3, ASC, cleaved caspase-1, and pro-IL-1β (Fig. 3H-L). However, when TREM2 activation was blocked, the LPS + DHE + TREM2 shRNA group exhibited significantly higher levels of NLRP3 protein compared to the LPS + DHE + control shRNA group. This implies that silencing TREM2 abolished the inhibitory effect of DHE on NLRP3 expression in LPS-stimulated BV2 cells (Fig. 3M).

Fig. 3.

DHE inhibited the activation of NF-κB signaling and the NLRP3 inflammasome in LPS-treated BV2 microglial cells via TREM2 activation. Cells were pretreated with DHE for 1 h and then exposed to LPS for another 24 h. (A–D) The levels of total/phosphorylated IKKα/β (A), IκB α (B), and P65 (C) were measured by Western blot. (D–E) The expression levels of total NF-κB p65 in the cytoplasmic fraction (D) and nuclear fraction (E) were quantified by Western blot. (F) The nuclear translocation of p65 was evaluated by immunofluorescence analysis. Cells were stained with anti-p65 antibody (green) and DAPI (blue). (G) Cells were transfected with negative control shRNA or TREM2 shRNA, and then the NF-κB p65 expression level in BV2 cells after treatment with DHE or LPS was assessed by Western blot analysis. (H) The mRNA levels of NLRP3 and IL-1β were detected by RT-PCR analysis. (I–L) Protein levels of NLRP3 (I), ASC (J), cleaved caspase-1 (K), and pro-IL-1β (L) were measured by Western blot analysis. (M) Cells were transfected with TREM2 shRNA or a negative control shRNA, and after being treated with DHE or LPS, the level of NLRP3 expression in BV2 cells was determined by Western blot analysis (∗∗p < 0.01 and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the one-way ANOVA). Data are presented as the mean ± SD analyzed by one-way ANOVA. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 vs. the LPS-treated group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, and ###p < 0.001 vs. the control group; N.S. = not significant; n = 3.

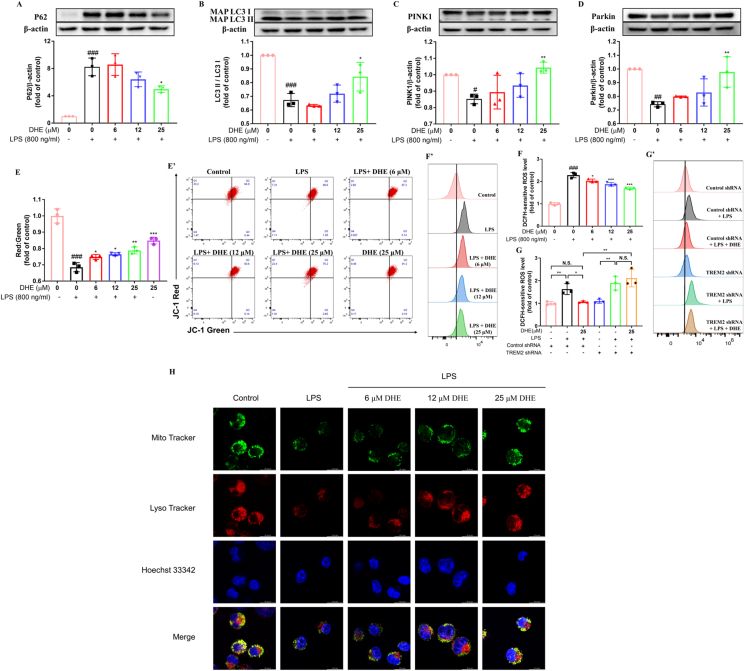

DHE promoted mitophagy and attenuated LPS-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in LPS-treated BV2 cells via TREM2 activation

Mitophagy, a mechanism critical for the removal of damaged mitochondria, plays a significant role in regulating the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [31]. Therefore, the effect of DHE on microglial mitophagy and mitochondrial function was investigated. The results revealed a significant decrease in the expression of microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3)-II, accompanied by a substantial increase in p62, an autophagy substrate, in BV2 cells following LPS treatment. Notably, treatment with DHE successfully reversed these alterations (Fig. 4A–B). Furthermore, DHE pretreatment exhibited a restorative effect on the expression of mitophagy-related proteins, including PINK1 and Parkin, within the mitochondria of LPS-treated microglial cells (Fig. 4C–D). Additionally, mitophagy was further detected by the colocalization of MitoTracker (mitochondria) and LysoTracker (lysosome). We found a decrease in the fluorescence dots of mitochondria and lysosomes in LPS-stimulated microglia. DHE treatment, however, displayed an increased colocalization of lysosomes with mitochondria, indicating enhanced mitophagosome formation for the clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria (Fig. 4H). Collectively, these findings suggest that DHE can promote mitophagy in LPS-treated BV2 cells. Next, we investigated the impact of DHE on mitochondrial function in LPS-treated BV2 cells. Flow cytometric analysis demonstrated that the down-regulated levels of polarized functional mitochondria induced by LPS were effectively restored upon treatment with DHE (Fig. 4E-E′). Moreover, DHE treatment significantly prevented the robust increase of intracellular ROS induced by LPS in BV2 cells (Fig. 4F-F′). However, TREM2-shRNA treatment completely reversed this protective effect of DHE in LPS-induced BV2 cells (Fig. 4 G-G’).

Fig. 4.

DHE promoted mitophagy and attenuated LPS-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in LPS-treated BV2 cells. Cells were pretreated with DHE for 1 h and then exposed to LPS for another 24 h. (A–D) Protein levels of P62 (A), LC3 (B), PINK1 (C), and Parkin (D) were measured by Western blot analysis. (E, E′) Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was evaluated by flow cytometry after staining cells with JC-1. (F, F′) Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production was quantified by flow cytometry using DCFH-DA staining in BV2 cells. (G, G′) Following transfection of cells with TREM2 shRNA, intracellular ROS production in BV2 cells treated with DHE or LPS was assessed by flow cytometry (∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗p < 0.01 by the one-way ANOVA). (H) Representative colocalization images after LysoTracker staining for lysosomes and MitoTracker staining for mitochondria in BV2 cells treated with DHE (6, 12, 25 μM) and/or LPS. Data are presented as the mean ± SD analyzed by one-way ANOVA. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 vs. the LPS-treated group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, and ###p < 0.001 vs. the control group; N.S. = not significant; n = 3.

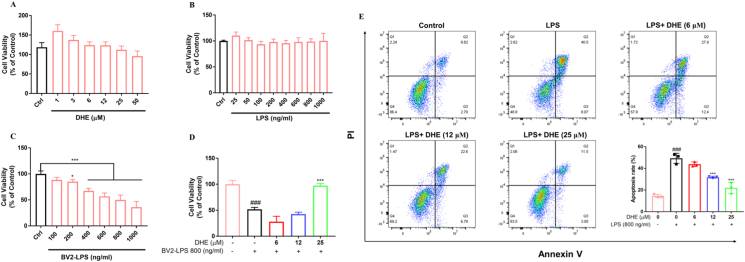

DHE exhibited neuroprotective effects on SH-SY5Y cells against LPS-stimulated microglia-mediated neurotoxicity

A co-culture system of BV2 cells and SH-SY5Y cells was established to investigate the potential of DHE in alleviating the harmful impacts of activated microglia on neurons. The results indicated that DHE (1–50 μM) or LPS (25–1000 ng/ml) treatment did not exhibit cytotoxicity toward SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 5A–B). Conversely, significant cellular toxicity was found in SH-SY5Y cells treated with BV2-LPS conditioned medium (BV2-LPS; 200–1000 ng/ml) for 24 h (Fig. 5C). Pretreatment with DHE (25 μM) provided significant protection against the cell loss induced by BV2-LPS (800 ng/ml) conditioned media (Fig. 5D). Additionally, an in vitro co-culture model was created using trans-well chambers to mimic the brain environment interaction between SH-SY5Y and BV2 cells. Flow cytometric analysis indicated that LPS reduced the number of healthy SH-SY5Y cells and increased late apoptosis. However, pretreatment with DHE decreased the percentage of cells undergoing late apoptosis and improved the percentage of healthy SH-SY5Y cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

DHE exhibited neuroprotective effects on SH-SY5Y cells against LPS-stimulated microglia-mediated neurotoxicity. (A, B) SH-SY5Y cells were treated with the indicated DHE (A) or LPS (B) concentrations. (C) SH-SY5Y cells were treated with conditioned medium from BV2 cells that had been exposed to 25–1000 ng/ml of LPS for 24 h, and the cell viability was detected by the MTT assay. (D) SH-SY5Y cells were treated with condition medium from BV2 microglia exposed to LPS (800 ng/ml) for 24 h after pretreatment with DHE (6, 12, 25 μM) for 1 h. The cell viability was detected by the MTT assay. (E) SH-SY5Y cells were co-cultured with BV2 cells in the presence of DHE (6, 12, 25 μM) for 1 h, followed by LPS stimulation for 24 h. Apoptosis was quantified by flow cytometry. Data are presented as the mean ± SD analyzed by one-way ANOVA. ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 vs. the LPS-treated group, ###p < 0.001 vs. the control group; n = 3.

DHE ameliorated LPS-induced motor deficits and neuroinflammation via the TREM2 signaling pathway in the zebrafish larvae model

The in vivo anti-neuroinflammatory effect of DHE was investigated using zebrafish due to their similarity to humans in phagocytic processes and inflammatory factors. The acute toxicity assay demonstrated that DHE had no significant impact on the survival rate of 4 dpf zebrafish larvae at concentrations of 25 μM or lower (Fig. S5). Subsequently, AB wild-type zebrafish larvae were pretreated with DHE (25 μM) at 4 dpf for 24 h; after that, LPS was injected into the head of the larvae, and biological analyses were carried out. Herein, 2.5 mg/ml of LPS markedly decreased the total swimming distance. However, treatment with DHE (25 μM) significantly improved the swimming distance of zebrafish, suggesting that DHE can reduce LPS-induced behavioral deficits in zebrafish (Fig. 6A–B). The expression of key pro-inflammatory cytokines in the LPS-stimulated zebrafish model was then assessed. As illustrated in Fig. 6C–F, the mRNA expression levels of iNOS, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α were markedly increased following exposure to LPS, but DHE treatment partially inhibited their expression. Surprisingly, 25 μM of DHE decreased the IL-1β expression to ∼22 % of that observed in the LPS-treated group, comparable to control levels. In addition, we investigated the impact of DHE on neutrophil infiltration in the brain, a hallmark of acute inflammatory response, using the Tg (Mpo:EGFP) zebrafish line. As shown in Fig. 6G-G′, neutrophils significantly migrated to the head to participate in neuroinflammation following LPS treatment, while DHE (25 μM) effectively prevented the recruitment of neutrophils in the zebrafish brain. Besides, our result demonstrated that ROS levels were significantly increased upon LPS exposure. However, pretreatment with DHE inhibited the ROS accumulation induced in zebrafish larvae (Fig. 6H-H’). Moreover, western blotting analysis results revealed that DHE significantly enhanced the expression of TREM2 and DAP12 while decreasing the levels of NLRP3 and phosphorylation of NF-κB induced by LPS (Fig. 6I-L).

Fig. 6.

DHE ameliorated LPS-induced motor deficits and neuroinflammation via the TREM2 signaling pathway in the zebrafish larvae model. The 4 dpf zebrafish larvae were pretreated with DHE (25 μM) for 24 h, followed by LPS stimulation for an additional 24 h. (A) The total distances moved by the zebrafish larvae were plotted and recorded every minute for 30 min; n = 10. (B) The total behavioral locomotion distance over 30 min in zebrafish larvae was quantitatively analyzed, and the zebrafish swimming track was represented at the top; n = 10. (C–F) The mRNA expression levels of iNOS (C), IL-6 (D), IL-1β (E), and TNF-α (F) were analyzed by qPCR; n = 4. (G, G′) The neutrophil migration in the brain of Tg (Mpo:EGFP) zebrafish larvae was visualized (G′), and the number of neutrophils in the brain was quantified (G); n = 7. (H, H′) ROS levels were observed by fluorescence microscopy (H′) and quantified by image analysis (H); n = 7. (I–L) Protein levels of TREM2 (I), DAP12 (J), NF-κB (K), and NLRP3 (L) were determined by Western blot analysis; n = 3. The data are presented as the mean ± SD; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 vs. the LPS-treated group; ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 vs. the control group.

Discussion

Increasing evidence implicates neuroinflammation as a contributor to various nervous system diseases, such as neurodegenerative disease and neuropathic pain diseases [[32], [33], [34]]. Current estimates suggest that neurodegenerative diseases impact around 15 % of the global population [35], underscoring the urgent need for treatments that target neuroinflammation-related neurological diseases. Inhibiting inflammatory responses triggered by overactivated microglia is considered a promising therapeutic strategy for these disorders. In the current study, we demonstrate for the first time that DHE acts as a novel exogenous ligand of TREM2, effectively suppressing overactivated microglia and the generation of pro-inflammatory mediators, thereby exerting neuroprotective effects in BV2 microglial cells and zebrafish.

Natural plants are a crucial source of drug discovery. Evidence suggests that heterocyclic alkaloids containing a monoterpene indole framework, prevalent in numerous plants, exhibit anti-inflammatory characteristics [36]. In addition, several studies have shown that MIAs extracted from T. bovina display anti-neuroinflammatory activity and neuroprotective potential [21,23,37]. However, a significant proportion of the biological activities associated with MIAs, particularly the corynantheine-type MIAs within this species, has yet to be adequately explored. Among the corynantheine-type MIAs identified in T. bovina, DHE and 20-epiervatamine are notable. Research has indicated that 20-epiervatamine can inhibit Na+ currents in various cell lines and synaptosomes by modulating channel gating mechanisms [38]. In contrast, there is a scarcity of research on the biological activities of DHE. Although certain corynantheine-type MIAs, such as reserpine, exhibit neuroactive properties and anti-inflammatory effects [39], the potential anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects of DHE and 20-epiervatamine have not been extensively explored. In this study, DHE and 20-epiervatamine, two MIAs identified in T. bovina, were investigated for their anti-neuroinflammatory activities and potential mechanisms. Our findings revealed that DHE more effectively inhibited NO generation in LPS-stimulated BV2 cells compared to 20-epiervatamine. Structure-activity relationship analysis suggests that this enhanced activity may be attributed to the presence of the 7-ethylidene group in DHE. In addition, molecular docking and CETSA analysis demonstrated that DHE exhibited a higher affinity for TREM2 compared to 20-epiervatamine, indicating its greater potential as a neuroinflammatory inhibitor.

TREM2 is an important modulator of microglial function, although its endogenous ligand remains unclear [40]. It is widely accepted that TREM2 interacts with the DNAX-activating protein of 12 kDa (DAP12) to form a receptor complex on the plasma membrane of the microglial cell [41]. Besides, TREM2, similar to TLRs, binds LPS and intrinsic ligands released during neuronal degeneration, resulting in the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues within the ITAM motif of DAP12 [7]. Numerous studies have revealed that TREM2 enhances phagocytosis of apoptotic neurons and suppresses the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α in microglia. However, several research studies have indicated that Trem2−/− mice show decreased nerve damage, increased microglia number at the lesion site, and suppressed the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the non-lesional site [[42], [43], [44], [45]]. The crucial function of TREM2 in neuroinflammation is still debated, but it is well established that TREM2/DAP12-mediated signaling acts as a prominent switch that transforms microglia from a disease-associated state to a homeostatic state [46]. In our study, DHE significantly upregulated the expression levels of TREM2 and DAP12 to suppress the over-activation of microglia in LPS-stimulated BV2 cells and zebrafish larvae. Additionally, computer simulations and the CETSA assay suggested that DHE could bind to TREM2. Recent findings have highlighted the importance of Arg77 and Arg47 in maintaining ligand interactions, as well as the structural and functional stability of TREM2 [47]. Phosphatidylserine, a ligand for TREM2, primarily interacts with TREM2 in the surface region of the CDR2 loop via key residues Arg77 and Arg47 [48]. Our data indicated DHE targeted TREM2 by forming carbon hydrogen bonds with the amino groups of Arg77 and Arg47, suggesting DHE can bind to the essential residues to activate TREM2. Furthermore, TREM2 was silenced to validate the role of TREM2 in the anti-inflammatory activity of DHE, and the results showed that TREM2 knockdown abolished the effect of DHE in reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines induced by LPS. These findings suggest that DHE from T. bovina may serve as a potential TREM2 agonist for the treatment of neuroinflammation.

The mechanism by which TREM2 inhibits inflammation is still not fully understood, but it is undeniable that NF-κB is crucial to this process. Several studies have shown that TREM2 can suppress NF-κB activation and exhibit anti-inflammatory properties when co-expressed with DAP12 [49]. Consistently, our study demonstrated that DHE reduced the expression of the NF-κB signaling pathway upon LPS stimulation both in the brain of zebrafish and BV-2 cells. However, this effect was abolished by the treatment of TREM2-shRNA, indicating the involvement of the NF-κB pathway in TREM2-modulated inflammatory responses. Besides, the NLRP3 pathway, a downstream pathway of NF-κB, regulates several inflammatory diseases. Previous studies have reported that the NLRP3 inflammasome activation involves two primary steps: pro-IL-1β and NLRP3 are synthesized through transcriptional activation of NF-κB; subsequently, the inflammasome oligomerizes, leading to the cleavage of caspase-1 and the release of biologically active IL-1β [50]. Here, we demonstrated that DHE inhibited the expression of NLRP3, ASC, mature caspase-1, and IL-1β in LPS-stimulated microglial cells. Furthermore, defective mitophagy can impair mitochondrial function, resulting in the release of mtROS and mtDNA, which subsequent overactivation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in microglia. Enhancing autophagy (mitophagy) can degrade damaged mitochondria and maintain cellular homeostasis [51]. Our results revealed that DHE promoted microglial autophagy, alleviated mitochondrial damage, and suppressed the generation of cellular ROS. However, TREM2-shRNA could also block the effect of DHE on NLRP3 signaling and ROS production. These data indicated that DHE enhanced TREM2 expression to suppress inflammatory responses in LPS-induced BV2 cells via NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathways.

In conclusion, our results demonstrated the therapeutic potential of DHE as a promising TREM2 agonist for alleviating LPS-induced neuroinflammation in microglial cells and zebrafish models. DHE directly targeted and activated TREM2 in microglial cells, leading to the suppression of NF-κB signaling and NLRP3 inflammasome formation. Consequently, this resulted in the reduction of pro-inflammatory factors and the mitigation of mitochondrial dysfunction, ultimately protecting nerve cells from damage. These findings highlight the potential of DHE as a TREM2 agonist for the treatment of CNS disorders associated with neuroinflammation.

Author Contributions

Lin Li, Benqin Tang and Simon Ming-yuen Lee designed the study; Lin Li, Yulin He and Nan Xu performed the experiments and acquired data; Lin Li, Nan Xu, Binrui Yang, Jun Du, Liang Chen, Xiaowen Mao, Bing Song, and Zhou Hua analyzed data; Lin Li, Mingsui Tang, Benqin Tang and Simon Ming-yuen Lee contributed to manuscript preparation. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The data used and/or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Development Fund (FDCT) of Macao SAR (No.: 0058/2019/A1 and 0016/2019/AKP), Shenzhen-Hong Kong-Macao Science and Technology Innovation Project (Category C) of Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Committee (No.: EF038/ICMS-LMY/2021/SZSTIC), and National Natural Science Foundation for Young Scientists of China (No. 81803398), and Chinese Medicine Guangdong Laboratory (Hengqin Laboratory) (HOCML-B-2024001), and University of Macau Multi-Year Research Grant (MYRG-CRG-2022-00006-FST).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurot.2024.e00479.

Contributor Information

Benqin Tang, Email: tangbenqincy@gmail.com.

Simon Ming-yuen Lee, Email: simon-my.lee@polyu.edu.hk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Fernández-Calle R., Vicente-Rodríguez M., Gramage E., Pita J., Pérez-García C., Ferrer-Alcón M., et al. Pleiotrophin regulates microglia-mediated neuroinflammation. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0823-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greve H.J., Mumaw C.L., Messenger E.J., Kodavanti P.R.S., Royland J.L., Kodavanti U.P, et al. Diesel exhaust impairs TREM2 to dysregulate neuroinflammation. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-02017-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo M.-L., Liao K., Periyasamy P., Yang L., Cai Y., Shannon E. Callen SE, et al. Cocaine-mediated microglial activation involves the ER stress-autophagy axis. Autophagy. 2015;11(7):995–1009. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1052205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu M., Yang Y., Peng J., Zhang Y., Wu B., He B., et al. Effects of Alpinae Oxyphyllae Fructus on microglial polarization in a LPS-induced BV2 cells model of neuroinflammation via TREM2. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023;302:115914. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J.-T., Zhang Y. TREM2 regulates innate immunity in Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1148-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun H., Feng J., Tang L. Function of TREM1 and TREM2 in liver-related diseases. Cells. 2020;9(12):2626. doi: 10.3390/cells9122626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gervois P., Lambrichts I. The emerging role of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 as a target for immunomodulation in ischemic stroke. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1668. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu S., Cao X., Wu Z., Deng S., Fu H., Wang Y., et al. TREM2 improves neurological dysfunction and attenuates neuroinflammation, TLR signaling and neuronal apoptosis in the acute phase of intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022:14. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.967825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang T., Zhang Y.-D., Chen Q., Gao Q., Zhu X.-C., Zhou J.-S., et al. TREM2 modifies microglial phenotype and provides neuroprotection in P301S tau transgenic mice. Neuropharmacology. 2016;105:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain N., Lewis C.A., Ulrich J.D., Holtzman D.M. Chronic TREM2 activation exacerbates Aβ-associated tau seeding and spreading. J Exp Med. 2022;220(1) doi: 10.1084/jem.20220654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang J., Fu Z., Zhang X., Xiong M., Meng L., Zhang Z. TREM2 ectodomain and its soluble form in Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-01878-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlepckow K., Monroe K.M., Kleinberger G., Cantuti-Castelvetri L., Parhizkar S., Xia D., et al. Enhancing protective microglial activities with a dual function TREM 2 antibody to the stalk region. EMBO Mol Med. 2020;12(4) doi: 10.15252/emmm.201911227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price B.R., Sudduth T.L., Weekman E.M., Johnson S., Hawthorne D., Woolums A., et al. Therapeutic Trem2 activation ameliorates amyloid-beta deposition and improves cognition in the 5XFAD model of amyloid deposition. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-01915-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kempuraj D., Thangavel R., Natteru P.A., Selvakumar GP., Saeed D., Zahoor H., et al. Neuroinflammation induces neurodegeneration. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery and spine. 2016;1(1) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohammed A.E., Abdul-Hameed Z.H., Alotaibi M.O., Nahed O., Bawakid N.O., Sobahi T.R., et al. Chemical diversity and bioactivities of monoterpene indole alkaloids (MIAs) from six Apocynaceae genera. Molecules. 2021;26(2):488. doi: 10.3390/molecules26020488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin W., Wang T.-S., Yin F.-Z., Cai B.-C. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties of brucine and brucine N-oxide extracted from seeds of Strychnos nux-vomica. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;88(2-3):205–214. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung H.Y., Nam K.N., Woo B.-C., Kim K.-P., Kim S.-O., Lee E.H. Hirsutine, an indole alkaloid of Uncaria rhynchophylla, inhibits inflammation-mediated neurotoxicity and microglial activation. Mol Med Rep. 2013;7(1):154–158. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J., Ao Y.L., Yao N., Bai W.-X., Fan C.-L., Ye W.-C., et al. Three new monoterpenoid indole alkaloids from Ervatamia pandacaqui. Chem Biodivers. 2018;15(10) doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201800268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pratchayasakul W., Pongchaidecha A., Chattipakorn N., Chattipakorn S. Ethnobotany & ethnopharmacology of Tabernaemontana divaricata. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127(4):317–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh M.K., Usha R., Hithayshree K.R., Bindhu O.S. Hemostatic potential of latex proteases from Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R. Br. ex. Roem. and Schult. and Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson ex. FA Zorn) Forsberg. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;39:43–49. doi: 10.1007/s11239-013-1012-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang B-q, Li Z-w, Li L., Li B.-J., Bian Y.-Q., Yu G.-D., et al. New iboga-type alkaloids from Ervatamia officinalis and their anti-inflammatory activity. Fitoterapia. 2022;156:105085. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2021.105085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kai T., Zhang L., Wang X., Jing A., Zhao B., Yu X., et al. Tabersonine inhibits amyloid fibril formation and cytotoxicity of Aβ (1–42) ACS Chem Neurosci. 2015;6(6):879–888. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z.-W., Huang X.-J., Xiao H.-L., Liu G., Zhang J., Shi L., et al. New iboga-type alkaloids from Ervatamia hainanensis. RSC Adv. 2016;6(36):30277–30284. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C., Bian Y., Feng Y., Tang F., Wang L., Hoi M.P.M., et al. Neuroprotective effects of BHDPC, a novel neuroprotectant, on experimental stroke by modulating microglia polarization. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2019;10(5):2434–2449. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou Z.-C., Fu J.-J., Dang Y.-Y., Zhang Q., Wang X.-F., Chen H.-B., et al. Pinocembrin-7-methylether protects SH-SY5Y cells against 6-hydroxydopamine-induced neurotoxicity via modulating Nrf2 induction through AKT and ERK pathways. Neurotox Res. 2021;39(4):1323–1337. doi: 10.1007/s12640-021-00376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westerfield M. 2000. The zebrafish book: a guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish.http://zfin.org/zf_info/zfbook/zfbk.html [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y., Fan Z., Yang M., Wang Y., Cao J., Khan A., et al. Protective effects of E Se tea extracts against alcoholic fatty liver disease induced by high fat/alcohol diet: in vivo biological evaluation and molecular docking study. Phytomedicine. 2022;101:154113. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nizami S., Hall-Roberts H., Warrier S., Cowley S.A., Di Daniel E. Microglial inflammation and phagocytosis in Alzheimer's disease: potential therapeutic targets. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176(18):3515–3532. doi: 10.1111/bph.14618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chivero E.T., Guo M.-L., Periyasamy P., Liao K., Callen S.E., Buch S. HIV-1 Tat primes and activates microglial NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuroinflammation. J Neurosci. 2017;37(13):3599–3609. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3045-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang W., Zhao B., Gao W., Song W., Hou J., Zhang L., et al. Inhibition of PINK1-mediated Mitophagy contributes to postoperative cognitive dysfunction through activation of Caspase-3/GSDME-dependent pyroptosis. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2023;14(7):1249–1260. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.2c00691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu Y., Tang Y., Lu J., Zhang W., Zhu Y., Zhang S., et al. PINK1-mediated mitophagy protects against hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury by restraining NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;160:871–886. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.González H., Pacheco R. T-cell-mediated regulation of neuroinflammation involved in neurodegenerative diseases. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12974-014-0201-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marshall S.A., McKnight K.H., Blose A.K., Lysle D.T., Thiele T.E. Modulation of binge-like ethanol consumption by IL-10 signaling in the basolateral amygdala. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2017;12(2):249–259. doi: 10.1007/s11481-016-9709-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wedel S., Mathoor P., Rauh O., Heymann T., Ciotu C., Fuhrmann D.C., et al. SAFit2 reduces neuroinflammation and ameliorates nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):254. doi: 10.1186/s12974-022-02615-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Schependom J., D’haeseleer M. Advances in neurodegenerative diseases. J Clin Med. 2023;12(5):1709. doi: 10.3390/jcm12051709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koyama K., Hirasawa Y., Nugroho A.E., Hosoya T., Hoe T.C., Chan K.-L., et al. Alsmaphorazines A and B, novel indole alkaloids from Alstonia pneumatophora. Org Lett. 2010;12(18):4188–4191. doi: 10.1021/ol101825f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu Y., Zhao S.-M., Bao M.-F., Cai X.-H. An Aspidosperma-type alkaloid dimer from Tabernaemontana bovina as a candidate for the inhibition of microglial activation. Org Chem Front. 2020;7(11):1365–1373. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frelin C., Vigne P., Ponzio G., Romey G., Tourneur Y., Husson H.P., et al. The interaction of ervatamine and epiervatamine with the action potential Na+ ionophore. Mol Pharmacol. 1981;20(1):107–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J., Li J.-X., Jiang H., Li M., Chen L., Wang Y.-Y., et al. Phytochemistry and biological activities of corynanthe alkaloids. Phytochemistry. 2023:113786. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2023.113786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xue T., Ji J., Sun Y., Huang X., Cai Z., Yang J., et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate, a novel TREM2 ligand, promotes microglial phagocytosis to protect against ischemic brain injury. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12(4):1885–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kobayashi M., Konishi H., Sayo A., Takai T., Kiyama H. TREM2/DAP12 signal elicits proinflammatory response in microglia and exacerbates neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2016;36(43):11138–11150. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1238-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krasemann S., Madore C., Cialic R., Baufeld C., Calcagno N., Fatimy R.E., et al. The TREM2-APOE pathway drives the transcriptional phenotype of dysfunctional microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunity. 2017;47(3):566–581. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saber M., Kokiko-Cochran O., Puntambekar S.S., Lathia J.D., Lamb B.T. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 deficiency alters acute macrophage distribution and improves recovery after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34(2):423–435. doi: 10.1089/neu.2016.4401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang T., Yu J.-T., Zhu X.-C., Tan L. TREM2 in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;48:180–185. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8424-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li R., Zhang J., Wang Q., Cheng M., Lin B. TPM1 mediates inflammation downstream of TREM2 via the PKA/CREB signaling pathway. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):257. doi: 10.1186/s12974-022-02619-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Konishi H., Kiyama H. Microglial TREM2/DAP12 signaling: a double-edged sword in neural diseases. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:206. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sudom A., Talreja S., Danao J., Bragg E., Kegel R., Min X., et al. Molecular basis for the loss-of-function effects of the Alzheimer’s disease–associated R47H variant of the immune receptor TREM2. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(32):12634–12646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dash R., Munni Y.A., Mitra S., Choi H.J., Jahan S.I., Chowdhury A., et al. Dynamic insights into the effects of nonsynonymous polymorphisms (nsSNPs) on loss of TREM2 function. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):9378. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13120-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yao H., Coppola K., Schweig J.E., Crawford F., Mullan M., Paris D. Distinct signaling pathways regulate TREM2 phagocytic and NFκB antagonistic activities. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:457. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xia C.-Y., Guo Y.-X., Lian W.-W., Yan Y., Ma B.-Z., Cheng Y.-C., et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome in depression: potential mechanisms and therapies. Pharmacol Res. 2023;187:106625. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qiu J., Chen Y., Zhuo J., Zhang L., Liu J., Wang B., et al. Urolithin A promotes mitophagy and suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation in lipopolysaccharide-induced BV2 microglial cells and MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease model. Neuropharmacology. 2022;207:108963. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2022.108963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used and/or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.