Abstract

Objective:

Severely mentally ill youths are at elevated risk for human immunodeficiency virus infection, but little is known about acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) risk behavior in adolescents who seek outpatient mental health services or about the links between psychiatric problems and particular high-risk behaviors. This pilot study used structural equation modeling to conduct a path analysis to explore the direct and indirect effects of adolescent psychopathology on risky sex, drug/alcohol use, and needle use.

Method:

Ethnically diverse youths (N = 86) and their caregivers who sought outpatient psychiatric services in Chicago completed questionnaires of adolescent psychopathology. Youths reported their relationship attitudes, peer influence, sexual behavior, and drug/alcohol use.

Results:

Different AIDS-risk behaviors were associated with distinct forms of adolescent psychopathology (e.g., delinquency was linked to drug/alcohol use, whereas aggression was related to risky sexual behavior), and peer influence mediated these linkages. Some patterns were similar for caregiver- and adolescent-reported problems (e.g., peer influence mediated the relation between delinquency and drug/alcohol use), but others were different (e.g., caregiver-reported delinquency was associated with risky sex, whereas adolescent-reported delinquency was not).

Conclusions:

Findings underscore the complexity of factors (types of informants and dimensions of psychopathology) that underlie AIDS risk in troubled youths, and they offer specific directions for designing and implementing uniquely tailored AIDS prevention programs, for example, by targeting delinquent behavior and including high-risk peers and important family members in interventions.

Keywords: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, AIDS risk, psychopathology, adolescents, peer influence

Adolescents are among the fastest growing population at risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and mentally ill youths are at even greater risk. Troubled youths engage in many of the same well-known HIV-risk behaviors as their same-age nondisturbed peers, but they do so at higher rates (Brown et al., 1997b). Most of the research, however, is based on youths admitted to psychiatric hospitals, who represent a subgroup of very ill teenagers. Little is known about the rates of risky behavior in the far greater number of youths who seek outpatient mental health services or about the links between psychiatric problems and particular risk behaviors. At present, behavior change is the most effective means of preventing HIV and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and the most effective prevention programs are tailored to specific population needs (Jemmott et al., 1992). Understanding the unique risk factors for youths with psychiatric problems is essential for designing customized interventions for this vulnerable group. This pilot study tested a theoretical model of AIDS risk in psychiatrically disturbed youths, focusing on the direct and indirect associations between adolescent psychopathology and three well-known AIDS-related behaviors: risky sex, drug/alcohol use, and needle use.

Understanding AIDS risk in teenagers who seek psychiatric care is essential. Troubled youths are at elevated risk of infection because they have sexual intercourse, use needles, and abuse substances at higher rates than nondisturbed teenagers (Brown et al., 1997b; DiClemente and Ponton, 1993), and they engage in more self-cutting, sharing cutting utensils, and injection drug use than non–psychiatrically ill youths (DiClemente et al., 1991b). Compared with general population adolescents, hospitalized youths report less frequent condom use, more frequent sexual activity and intravenous drug use, and a higher lifetime prevalence of pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases (DiClemente and Ponton, 1993). Inadequate sexual communication skills, increased susceptibility to peer norms that encourage deviant sexual behavior, and more involvement in prostitution and sex with high-risk partners place these youths at even greater risk (Morris et al., 1995; Rotheram-Borus et al., 1991). Mental health problems are related to HIV risk behavior, and problem behaviors among adolescents (e.g., drug use, minor criminal activity) covary with risky sex (i.e., condom nonuse) (DiClemente et al., 1996; Flisher et al., 2000; Jessor, 1991). Mental health symptoms during adolescence are associated with increased AIDS-risk behavior in young adulthood (Stiffman et al., 1992), and AIDS prevention programs are more effective when they include a mental health treatment component (Rotheram-Borus et al., 1989; Stiffman et al., 1992). Finally, high numbers of youths seek outpatient psychiatric services, which makes them particularly accessible for HIV/AIDS prevention because they are already in a mental health service system. By identifying the unique risk mechanisms associated with these teenagers, customized prevention programs for youths with mental health problems can be designed. This task is made more complex by the fact that risk factors may vary by type of psychopathology, and prevention programming will need to be tailored accordingly. In sum, HIV infection among teenagers in psychiatric care is an emerging public health crisis, but existing research is based solely on hospitalized teenagers, and we do not know whether the patterns are similar for the far greater number of youths who seek outpatient services. This study examines rates of AIDS-risk behavior in adolescents seeking outpatient psychiatric treatment.

Unfortunately, research linking AIDS-risk behavior and specific psychiatric problems has yielded mixed results. Danovsky and Brown (1996) found no associations between specific diagnoses and AIDS-risk behaviors, but other findings support such links. Internalizing problems (low self-esteem, depression, anxiety) are associated with low perceived self-efficacy (Brooks-Gunn and Paikoff, 1997; Brown et al., 1997b), decreased assertiveness, and minimal ability to negotiate safe sex with a partner (McFarlane et al., 1995), whereas avoidant and withdrawn behavior are linked to decreased sexual activity (Tubman et al., 1996). Depression and low self-esteem are also linked to illicit drug use, sexually permissive attitudes, having sexually active friends, sexual behavior, low contraception use, high risk of pregnancy, and nonvirgin status (Dolcini and Adler, 1994; Hayes, 1987; Henggeler et al., 1992; Rotheram-Borus et al., 1989, 1995b; Whitbeck et al., 1993). Moreover, hopelessness and helplessness may reduce adolescents’ motivation to make health-promoting choices (Brooks-Gunn and Paikoff, 1997).

By comparison, research consistently associates externalizing problems (delinquency, impulsivity) with high rates of risky sex, drug/alcohol use, and needle use, especially for highly externalizing teenagers (e.g., delinquents, runaways) (Koopman et al., 1994; Rotheram-Borus and Koopman, 1991; Rotheram-Borus et al., 1989; Stiffman and Cunningham, 1991). These youths engage in a broad array of HIV risk behaviors, including frequent sexual activity; early sexual debut; low rates of condom use; high numbers of sexual partners; high rates of prostitution, drug use, needle sharing, and exchanging sex for drugs, and drug/alcohol use before and during sex (Gillmore et al., 1994; Inciardi et al., 1991; Morris et al., 1992; Weber et al., 1989).

Studies that compare HIV risk behavior among youths with externalizing and internalizing problems are virtually nonexistent. One of the few available investigations compared risk-taking orientation in teenagers in outpatient treatment who had conduct disorder versus those who did not (Lavery et al., 1993). Youths who had conduct disorder reported higher levels of risk behavior and a higher perceived benefit of risk than youths who did not; youths without conduct disorder reported fewer risk behaviors and minimized the degree of risk in their behavior. The non–conduct disorder group was not restricted to internalizing youths; therefore, the findings may not represent comparisons between internalizing and externalizing youths. In another study, teenagers with conduct disorder reported higher rates of risk behavior than did teenagers with an affective disorder (DiClemente et al., 1989); however, participants were psychiatric inpatients, and findings may not generalize to less severely mentally ill youths. Finally, Stiffman et al. (1992) surveyed 602 youths over 3 years to examine changes in AIDS-related behavior from adolescence to young adulthood. Findings revealed similar patterns for diverse problems; higher risk-taking in adulthood was related to symptoms of conduct disorder, depression, anxiety, and substance use during adolescence. However, because participants were not identified as psychiatrically impaired at the outset, the data offer limited insight about risk behavior among youths who receive mental health services.

Mixed findings linking psychopathology and AIDS risk may be explained by an emphasis in research on broadband mental health problems (internalizing versus externalizing). Broad-band measures combine different types of psychopathology that may show unique relationships with particular outcomes. We sought to clarify the mixed findings by examining links between three well-known AIDS-risk behaviors, broad-band dimensions, and narrow-band syndromes (anxiety/depression, delinquency, aggression).

Indirect links between AIDS-risk and adolescent psychopathology may also explain the mixed findings of past research. For instance, youths with psychiatric problems tend to have strained peer and family relationships (Brown et al., 1997b; DiLorenzo and Hein, 1995). High interpersonal conflict and the absence of family and peer support may lead youths to engage in high-risk behavior to obtain peer approval, avoid rejection (Cochran and Mays, 1989), and satisfy unmet relationship needs such as love, affiliation, and closeness (Sanderson and Cantor, 1995; Sprecher and McKinney, 1987). There is evidence that adolescent psychopathology and substance abuse are associated with increased fear of rejection and difficulty tolerating intimacy (Brown et al., 1997b). Nondisturbed teenagers are susceptible to peer influence with regard to risky behavior and sexual decision-making (Brown et al., 1997a; DiClemente et al., 1996; Romer et al., 1994), but troubled youths may be especially vulnerable because of their heightened sensitivity to maintaining relationships at all cost. Yet, no studies have explored the effect of relationship attitudes on the association of psychopathology and AIDS-risk among troubled youths. Thus this pilot study focused on three potential relationship mediators: peer influence, need for intimacy, and fear of rejection.

This study examined three questions: (1) What are the rates of drug/alcohol use, needle use, and risky sexual behavior among adolescents who seek outpatient mental health services? (2) Are there direct associations between AIDS-risk behaviors and adolescent broad-band and narrow-band problems? (3) Are the associations between AIDS-risk and psychopathology mediated by relationship attitudes? Using data from teenagers seeking outpatient psychiatric services, we tested a path model that assessed the direct and indirect effects of mental health problems on youths’ drug/alcohol use, needle use, and risky sexual practices. Because risk may vary across disorders, we tested the model separately for broad-band (externalizing and internalizing) and narrow-band (delinquency, aggression, and anxiety/depression) problems. We expected higher risk behavior to be associated with more externalizing problems (aggression, delinquency), and elevated rates of externalizing problems to be associated with the three relationship attitudes. We also expected associations between relationship attitudes and heightened AIDS risk. Previous evidence did not support directional hypotheses for internalizing disorders.

METHOD

Overview of Procedures

This study is part of a larger longitudinal study of AIDS-risk behavior in youths in psychiatric care. Participants were youths and caregivers (hereafter referred to as “parents”) who sought outpatient mental health treatment at a hospital in Chicago. At the beginning of treatment, parents and adolescents separately completed well-known measures of adolescent psychopathology, relationship attitudes, and HIV/AIDS-risk behavior as part of the hospital’s routine clinical procedure. Research staff asked teenagers and parents for permission to use the clinical data for research, after reassuring them that research participation was completely voluntary. Interested families reviewed the assent/consent forms, and a high number of adolescents’ and parents’ assented/consented to participate (132/147 = 90%). After completion of the interview, we gave parents and teenagers each an informational pamphlet about AIDS transmission and prevention published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Total testing time was approximately 1.5 hours.

Participants

Parent (N = 81) and adolescent (N = 86) participants are a subset of the larger sample for whom complete data were available. Youths ranged in age from 13 to 20 years (mean = 16.01; SD = 1.61), 55.8% were female, 36.3% scored in the first three levels of the Hollingshead index (Hollingshead, 1975), and the sample was ethnically diverse (40.7% white, 37.2% African/African American, 9.3% Latino, 9.3% biracial, 3.5% Asian). We excluded youths from the study who (1) were identified by the clinic as mentally retarded or as having known organic impairment that might interfere with understanding the questions or the consent/assent process (n = 5); (2) were wards of the Department of Child and Family Services, because their institutional review board denied approval (n = 8); (3) did not speak English (measures are normed for English speakers) (n = 4); and (4) did not live with a guardian or caretaker (n = 4).

Measures

AIDS-Risk Behavior Assessment.

The AIDS-Risk Behavior Assessment (ARBA) is a structured interview designed specifically for use with adolescents to assess their self-reported sexual behavior, drug/alcohol use, and needle use associated with HIV-infection. It was derived from four well-established measures of sexual behavior and drug/alcohol use (Dowling et al., 1994; Institute of Behavioral Science, 1991; Needle et al., 1995; NIDA, 1995; Teplin, 1998, personal communication; Watters, 1994; Weatherby et al., 1994) and assesses alcohol and drug use (e.g., lifetime use, method of use, frequency), needle use (e.g., sharing, tattooing, piercing), and sexual behavior (e.g., lifetime sexual intercourse, frequency, contraceptive use, high-risk sexual behavior) within the past 30 days and the past 3 months. The ARBA uses a skip structure so that initial screening questions answered in the negative are not followed by more detailed items. Youths self-administered the ARBA by using a portable cassette tape player and recorded their responses on a questionnaire, but an interviewer stayed in the room to answer questions and ensure item comprehension. The procedure worked well, was acceptable to youths, and elicited relevant information. A copy of the measure may be obtained from the first author.

Separate scaled scores for drug/alcohol use, needle use, and risky sexual behavior were the outcome variables in the data analyses. The drug/alcohol composite was created by summing the number of drugs used in the past 3 months and assigning one point each if participants injected or booted (injecting a drug partially into a vein, then withdrawing blood into syringe before reinjecting). Only one participant injected or booted, so this score mainly represents the number of substances used in the past 3 months. Needle use ranged in scale from 0 to 5, with 1 point each assigned for injection, booting, tattooing, piercing, and cutting. Because only one participant reported injecting, there was minimal overlap between needle use and drug/alcohol use. Risky sexual behavior was derived by summing the number of sexual partners in the past 3 months, and assigning 1 point each if participants had sex while using drugs/alcohol, without a condom, and with a high-risk partner (sexual history was not known).

Child Behavior Checklist.

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) is a widely used, standardized parent-report measure of 118 child behavior problems. The CBCL is normed for youths aged 4 to 18 and generates raw and T scores for broad-band internalizing (e.g., sadness, anxiety) and externalizing (e.g., fighting, swearing) problems, as well as eight narrow-band syndromes (e.g., depressed/anxious, delinquency). There is extensive evidence for the CBCL’s test-retest reliability, criterion validity, and convergent validity (Achenbach, 1991).

Youth Self-Report.

The Youth Self-Report (YSR) is a self-report measure of adolescent behavior and emotional problems that contains 112 self-statements (e.g., “I cry a lot,” “I get in many fights”). The instrument is normed for 11- to 18-year-olds and generates raw and T scores for broad-band internalizing (e.g., sadness, anxiety) and externalizing (e.g., fighting) dimensions, as well as eight narrow-band syndromes (e.g., aggressive, anxious/depressed). Evidence for the YSR’s reliability and validity is extensive (Achenbach, 1991).

Teenage Relationships.

The Teenage Relationships (TR) measure contains scales for fear of rejection and need for intimacy in close relationships. Five items measure youths’ feelings of security and sensitivity to rejection, and eight items assess the desire for intimacy. The fear of rejection scale was developed for older adolescents in dating relationships (Downey and Feldman, 1996), and the intimacy items are from Social Dating Goals scale. Item wording was modified to increase readability, comprehension, and relevance for urban youths 12 to 18 years old. The internal consistency was strong for both scales in this study: 0.78 for fear of rejection and 0.81 for need for intimacy.

Peer Support of Risky Behavior.

The Peer Support of Risky Behavior (PSRB) is a six-item subscale of the Health Questionnaire (HQ) ( Jessor and Jessor, 1977), a widely used and well-validated measure of adolescent health behavior (Costa et al., 1996). This PSRB combines two subscales of the Health Questionnaire measuring peer support and approval of high-risk behavior, including drinking alcohol, smoking marijuana, smoking cigarettes, and having sex. The scale’s internal consistency was strong (0.86) in this study.

RESULTS

ANALYSIS STRATEGY

Data analyses proceeded in three stages using a combination of descriptive statistics and multivariate procedures. In stage 1, we calculated the frequency of AIDS-risk behaviors to determine rates among youths in psychiatric care. In stage 2, we evaluated the properties of potential predictors and criterion measures to determine which variables to include in the analyses (i.e., parent versus youth reports, broad-band versus narrow-band psychopathology, overall risk versus specific risk behaviors). In stage 3, we used structural equation modeling to conduct a path analysis that investigated direct and indirect effects of psychopathology on AIDS-risk. Path analysis has traditionally been done by means of a series of separate multiple regression models for each dependent variable. Instead, we used structural equation modeling to simultaneously test the relationships among the entire set of measured variables. This approach allowed us to estimate not only the individual path coefficients and their levels of statistical significance, but also the proportion of variance explained in each dependent measure and the model’s overall fit to the data (Kline, 1998; Maruyama, 1998).

The path model was estimated using LISREL 8 (Joreskog and Sorbom, 1996), which provides maximum likelihood estimates, standard errors, and associated p values, χ2 statistics, and goodness-of-fit indices. Values of χ2 vary on the basis of sample size and model size (Bollen, 1989); therefore, we used additional indices to assess model fit (Dillon and Goldstein, 1984). A goodness-of-fit index (GFI) of 0.90 or higher was set as evidence of acceptable model fit (Bentler and Bonett, 1980), but we also report the comparative fit index (CFI) for each model test. We also gauged the magnitude of relationships by using d, which expresses the strength of an effect in terms of the equivalent difference between an experimental group’s mean and a control group’s mean divided by a pooled standard deviation. An effect size (d) of 0.20 is considered small, 0.50 is moderate, and 0.80 is large (Cohen, 1988). We used one-tailed tests to interpret significant effects in cases for which specific directional predictions were proposed (tests involving externalizing problems) and two-tailed tests in all other cases (tests involving internalizing problems). Overall, effects were robust; 22 out of 28 path coefficients were statistically significant at a two-tailed level.

Model testing proceeded in two waves. First, we evaluated the direct effects of psychopathology on AIDS-risk behavior while excluding mediating variables from the model; second, we examined the direct and indirect effects of psychopathology on AIDS-risk while including the potential mediating variables of relationship attitudes (peer influence, need for intimacy, fear of rejection). In each analysis, we controlled for the effects of age and gender by first residualizing the outcomes for these demographic effects. On the basis of moderate zero-order correlations between drug/alcohol use and risky sex and between drug/alcohol use and needle use, we allowed for correlated residuals between these variables. We tested each model with and without the correlated residuals and found no substantive differences in the results. However, because including the correlated residuals produced significantly better model fit, we retained them in the path models.

STAGE 1: RATES OF RISK BEHAVIOR

Youths in outpatient psychiatric care reported high rates of important risk behaviors: 54.7% had sexual intercourse, 45.2% had sexual intercourse in the past 3 months, 8.3% had been pregnant, 41.9% used drugs/alcohol in the past month, 23.3% had self-mutilated, 17.4% had tattoos, and 19.8% had pierced their bodies. Among sexually active youths (n = 47), 12.8% had a sexually transmitted disease, 48.9% had sex while using drugs/alcohol, 55.3% had sex without a condom, and 42.6% had sex with a high-risk partner.

STAGE 2: SELECTING PREDICTOR AND CRITERION MEASURES

Consistent with prior research (Achenbach et al., 1987), correlations revealed minimal overlap between youths and parent reports of internalizing and externalizing problems, anxiety/depression, aggression, or delinquency (r = 0.15 to r = 0.41). Similarly, for parents and for adolescents, only modest relationships were present between externalizing and internalizing problems and among the three narrow-band syndromes, with one exception; there was a high correlation between aggression and delinquency for parents (r = 0.64) and for adolescents (r = 0.70) (Table 1). Overlap among the three AIDS-risk behaviors (risky sex, drug/alcohol use, needle use) was modest (Table 1). Taken together, the data did not justify combining parent and youth reports, averaging across types of psychopathology, or creating an overall risk score. Therefore, we tested the model separately for parents and youths and for broadband and narrow-band psychopathology, and we used these variables to predict all three risk behaviors.

TABLE 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlation Matrix of Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Internalizing | — | .33b | .29b | .14 | .86d | .16 | .06 | .17 | .21 | .24a | .25a | 56.85 | 11.66 |

| 2. Externalizing | .59d | — | .91d | .87d | .31b | .40d | .32b | .36c | .49d | .17 | .12 | 60.90 | 11.88 |

| 3. Aggression | .38c | .80d | — | .70d | .32b | .37d | .19 | .28b | .38d | .21 | .08 | 60.24 | 9.27 |

| 4. Delinquency | .34b | .80d | .64d | — | .16 | .38d | .42d | .39d | .53d | .11 | .09 | 63.56 | 9.32 |

| 5. Anxiety/depression | .65d | .32b | .46d | .25a | — | .19 | .04 | .12 | .22a | .23a | .18 | 59.31 | 10.03 |

| 6. Risky sexual behavior | −.01 | −.05 | −.07 | .17 | .17 | — | .66d | .48d | .55d | .14 | −.09 | 2.98 | 2.90 |

| 7. Drug/alcohol use | .09 | .01 | −.14 | .19 | .06 | .63d | — | .53d | .67d | .02 | −.12 | 1.29 | 1.44 |

| 8. Needle use | .16 | .10 | −.07 | .25a | .07 | .43d | .48d | — | .44d | .15 | .04 | 0.69 | 1.01 |

| 9. Peer influence | .09 | .02 | −.17 | .19 | .05 | .54d | .67d | .46d | — | .07 | .08 | 14.63 | 3.96 |

| 10. Need for intimacy | −.04 | .06 | .13 | −.01 | .01 | .08 | −.04 | .07 | .04 | — | −.15 | 3.81 | 0.78 |

| 11. Fear of rejection | .04 | −.01 | −.10 | −.03 | −.05 | −.05 | −.08 | .12 | .10 | −.14 | — | 1.94 | 1.69 |

| 12. Mean | 61.44 | 61.57 | 61.90 | 64.07 | 61.19 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 13. SD | 11.85 | 12.64 | 10.80 | 10.69 | 9.67 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Note: Tabled above the diagonal are statistics for adolescent reports (N = 86). Tabled below the diagonal are statistics for parent reports (N = 81).

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001;

p < .0001.

STAGE 3: PATH ANALYSIS OF ADOLESCENTS’ AIDS-RISK BEHAVIOR

Direct Effects of Adolescent Psychopathology on AIDS-Risk Behavior

We tested the direct effects of psychopathology on AIDS-risk behavior for broad-band (externalizing and internalizing) and narrow-band (delinquency, aggression, anxiety/depression) problems separately for parents and adolescents. Mental health symptoms were exogenous predictors, and the three AIDS-risk behaviors (residualized for sex and age) were endogenous outcomes. Analyses yielded an interesting pattern of results for parents and youths and for broad-band and narrow-band problems.

Broad-Band Measures

Adolescent-reported internalizing problems were not significantly associated with any AIDS-risk behavior, whereas externalizing problems were positively associated with all three AIDS-risk outcomes in the expected direction: greater externalizing problems were related to more drug/alcohol use (β = .32, p < .0022, d = 0.44), needle use (β = .30, p < .0036, d = 0.42), and risky sex (β = .37, p < .0004, d = 0.53). The overall fit of the model was good, χ21 (N = 86) = 12.97, p = .0003, GFI = 0.95, CFI = 0.86, but the variance explained in drug/alcohol use (R2 = 0.09), needle use (R2 = 0.08), and risky sex (R2 = 0.12) was relatively low. Parent-reported externalizing and internalizing problems were not significantly associated with any AIDS-risk behavior, even though the model fit the data well, χ21 (N = 81) = 12.15, p = .0005, GFI = 0.95, CFI = 0.86.

Narrow-Band Measures.

Findings were similar for youths’ self-reported narrow-band syndromes. Delinquency and aggression, but not anxiety/depression, were related to AIDS-risk, with increased delinquency associated with greater drug/alcohol use (β = .46, p < .0007, d = 0.50) and greater needle use (β = .26, p < .042, d = 0.27), and higher levels of aggression related to more risky sex (β = .30, p < .023, d = 0.31). The model fit the data well, χ21 (N = 86) = 13.07, p = .0003, GFI = 0.96, CFI = 0.92, but explained only a modest amount of variance in drug/alcohol use (R2 = 0.15), needle use (R2 = 0.10), and risky sex (R2 = 0.13).

In contrast to the absence of findings for parent-reported broad-band psychopathology, parent-reported narrow-band problems were linked to risky behavior. Delinquency and aggression were associated with AIDS-risk behavior, but in distinct ways. Like adolescent reports, parent-reported delinquency was related to higher rates of all three AIDS-risk behaviors: drug/alcohol use (β = .40, p < .0025, d = 0.45), needle use (β = .39, p < .0029, d = 0.44), and risky sex (β = .28, p < .027, d = 0.10). Parent-reported aggression was not significantly related to risky sex, but it was associated with less drug/alcohol use (β = −.34, p < .016, d = 0.34) and less needle use (β = −.29, p < .038, d = 0.28); that is, parents’ perceptions of increased aggression were related to decreased risk. Parent-reported anxiety/depression approached significance in relation to risky sex (β = .23, p < .058, d = 0.30) in the expected direction. Model fit was excellent, χ21 (N = 81) = 8.38, p = .004, GFI = 0.97, CFI = 0.94, but, again, the variance explained in drug/alcohol use (R2 = 0.10), needle use (R2 = 0.10), and risky sex (R2 = 0.09) was modest.

Effects of Adolescent Psychopathology on AIDS-Risk Behavior Mediated by Peer Influence, Fear of Rejection, and Need for Intimacy

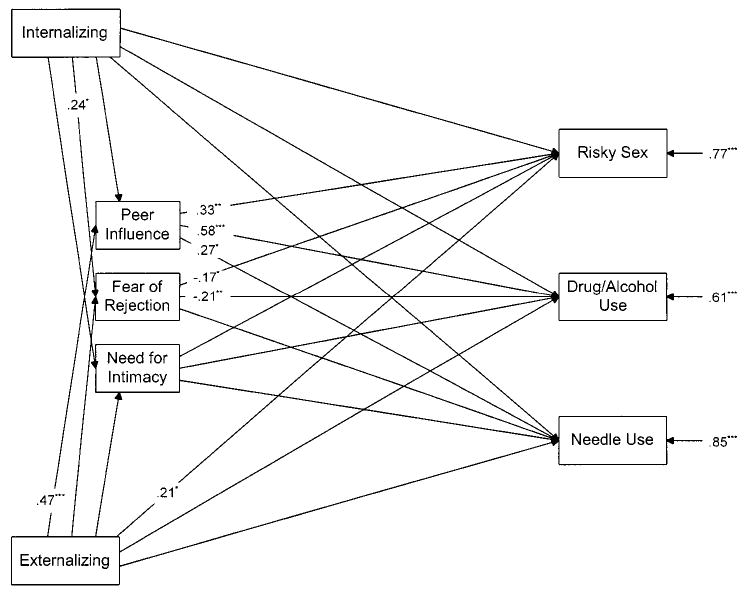

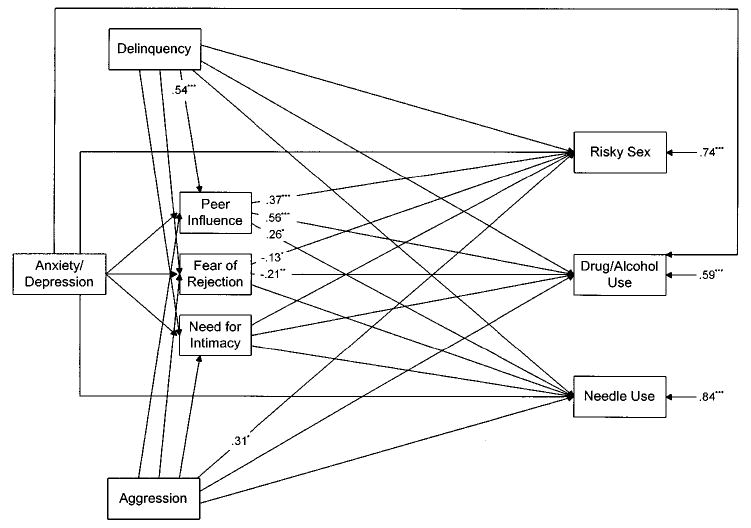

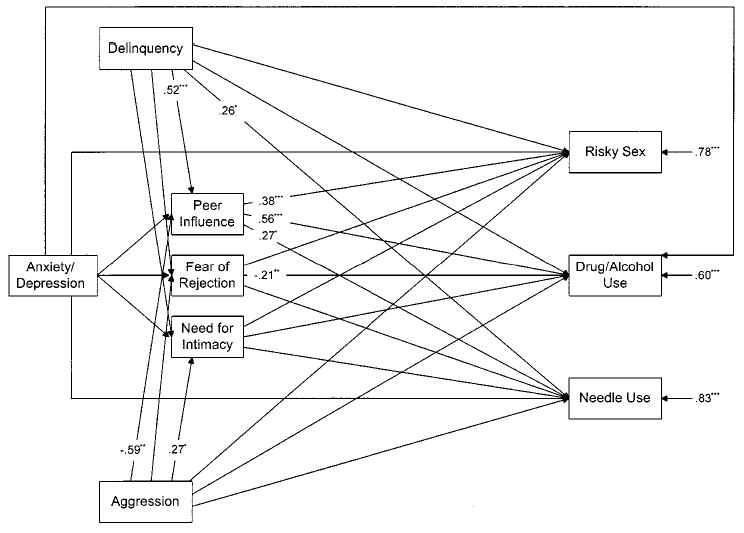

We used Baron and Kenny’s (1986) guidelines to test three potential mediators of the direct effect of psychopathology on AIDS-risk behavior (i.e., peer influence, fear of rejection, and need for intimacy) referred to generally as relationship attitudes. In accordance with Baron and Kenny’s approach, a relationship attitude was considered a mediator when (1) psychopathology (the predictor, A) was correlated both with AIDS-risk behavior, the outcome variable, C (A ↔ C), and with the mediator, B (A ↔ B); (2) the mediator was correlated with AIDS-risk behavior (B ↔ C); (3) the paths between psychopathology and the mediator and between the mediator and AIDS-risk behavior were significant when both of these paths were included in the model; and (4) the presence of the mediator either reduced the strength of the direct effect (partial mediation) or rendered the direct effect statistically nonsignificant (full mediation). We tested mediation only for paths that yielded significant direct effects without the mediators in the model, but all variables were included in the model to control for their effects. Thus we tested two mediation models for youth-reports: (1) externalizing problems associated with all three AIDS-risk behaviors (Fig. 1), and (2) delinquency related to drug/alcohol use and needle use, and aggression associated with risky sexual behavior (Fig. 2). In addition, we tested one mediation model for parent-reported narrow-band syndromes, delinquency associated with all three outcomes, and aggression related to drug/alcohol use and needle use (Fig. 3). Each model included all three potential mediators.

Fig. 1.

Mediational path model linking the adolescent-reported, broad-band measure of psychopathology (i.e., externalizing problems) to AIDS-risk behaviors through relationship attitudes (N = 86). Data are standardized path coefficients that attained statistical significance in the model, as well as the proportion of unexplained residual variance for each of the three AIDS-risk behaviors. For presentational clarity, we omitted path coefficients for those linkages that were statistically nonsignificant, as well as the unexplained residual variance for each relationship attitude. These data are available on request. AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Fig. 2.

Mediational path model linking adolescent-reported, narrow-band measures of psychopathology (i.e., delinquency and aggression) to AIDS-risk behaviors through relationship attitudes (N = 86). Data are standardized path coefficients that attained statistical significance in the model, and the proportion of unexplained residual variance for each of the three AIDS-risk behaviors. For presentational clarity, we omitted path coefficients for those linkages that were statistically nonsignificant, as well as the unexplained residual variance for each relationship attitude. These data are available on request. AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Fig. 3.

Mediational path model linking parent-reported, narrow-band measures of psychopathology to AIDS-risk behaviors through relationship attitudes (N = 86). Data are standardized path coefficients that attained statistical significance in the model, and the proportion of unexplained residual variance for each of the three AIDS-risk behaviors. For presentational clarity, we omitted path coefficients for those linkages that were statistically non-significant, as well as the unexplained residual variance for each relationship attitude. These data are available on request. AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Broad-Band Measures.

The first mediation model revealed a consistent pattern for youth-reported externalizing problems. Externalizing symptoms were not associated with fear of rejection or need for intimacy, but they were highly related to peer influence (β = .47, p < .0000, d = 0.78). Peer influence, in turn, was strongly related to all three AIDS-risk behaviors: drug/alcohol use (β = .58, p < .0000, d = 0.86), needle use (β = .27, p < .011, d = 0.35), and risky sex (β = .33, p < .0013, d = 0.47). Model fit was acceptable, χ24 (N = 86) = 14.10, p = .007, GFI = 0.96, CFI = 0.93, and the variance explained in drug/alcohol use (R2 = 0.39), needle use (R2 = 0.15), and risky sex (R2 = 0.23) was moderate. Whereas the direct effects of externalizing problems on drug/alcohol use (β = .05) and needle use (β = .16) were nonsignificant in the mediated model, the effect on risky sex was reduced but not eliminated (β = .21, p < .033, d = 0.28). These findings offer strong evidence that peer influence fully mediated the link between adolescent-reported externalizing problems, drug/alcohol use, and needle use, but only partially mediated the effect on risky sex.

Narrow-Band Measures.

Analyses of the indirect effects of youth-reported delinquency on drug/alcohol use and needle use yielded a similar pattern: delinquency was not associated with fear of rejection or need for intimacy, but it was strongly related to peer influence (β = .54, p < .0000, d = 0.66), and peer influence was highly associated with increased drug/alcohol use (β = .56, p < .0000, d = 0.91) and needle use (β = .26, p < .016, d = 0.33). Furthermore, direct effects of delinquency on drug/alcohol use (β = .16, not significant [NS]) and needle use (β = .12, NS) disappeared in the mediated model, supporting full mediation. By contrast, aggression was not significantly associated with any of the mediators, and its direct effect on risky sex remained significant in the presence of the mediators (β = .31, p < .014, d = 0.34). Model fit was acceptable, χ24 (N = 86) = 13.45, p = .009, GFI = 0.97, CFI = 0.95, and the variance explained in drug/alcohol use (R2 = 0.41), needle use (R2 = 0.16), and risky sex (R2 = 0.26) was moderate. Thus peer influence fully mediated the effects of delinquency on drug/alcohol use and needle use, but there was no mediation of effects for aggression and risky sex.

Finally, results yielded the same general pattern of mediation for parent-reported narrow-band syndromes in AIDS risk. Delinquency (β = .52, p < .0001, d = 0.62) and aggression (β = −.59, p < .0000, d = 0.65), but not anxiety/depression, were significantly related to peer influence, and peer influence was associated with all three risk outcomes: drug/alcohol use (β = .56, p < .0000, d = 0.95), needle use (β = .27, p < .011, d = 0.36), and risky sex (β = .38, p < .0004, d = 0.52). Aggression was also significantly associated with need for intimacy (β = .27, p < .047, d = 0.26), but intimacy was not related to any of the outcomes. Model fit was good, χ24 (N = 81) = 8.93, p = .06, GFI = 0.98, CFI = 0.97, and the predictors explained a relatively high proportion of variance in drug/alcohol use (R2 = 0.40), needle use (R2 = 0.17), and risky sex (R2 = 0.22). The direct effect of delinquency on drug/alcohol use (β = .09, NS) and risky sex (β = .09, NS), but not needle use (β = .26, p < .04, d = 0.27), disappeared in the mediated model, suggesting complete mediation for two of the three outcomes, but only partial mediation for the third. Contrary to expectations, parent-reported aggression was negatively related to peer influence, suggesting that increased aggression was associated with less peer influence, but greater peer influence was associated with more risk behavior. The direct effect of aggression on drug/alcohol use (β = .01, NS) and needle use (β = −.13, NS) disappeared in the mediated model, indicating complete mediation by peer influence.

DISCUSSION

This study is one of the first efforts to understand AIDS-risk behavior in teenagers seeking outpatient psychiatric care. Findings revealed high rates of risky behavior in this population and unique links between specific types of psychopathology and different risk behaviors, but they underscore the importance of key contextual factors (i.e., informant, type of psychopathology, kind of risk behavior) in understanding the influence of psychopathology on AIDS risk (Donenberg and Weisz, 1997). Adolescent-reported, but not parent-reported, externalizing problems were significantly related to teenagers’ drug/alcohol use, needle use, and risky sex, and neither parent- nor adolescent-reported internalizing problems were significantly associated with any high-risk behavior. These results are consistent with previous research that links externalizing problems to increased risk behavior (DiClemente et al., 1991a; Lavery et al., 1993; Weber et al., 1989), but this study extends earlier findings to needle use, focuses on adolescents in outpatient psychiatric care, and establishes the specificity of direct influences. As broad dimensions, however, externalizing and internalizing symptoms encompass several distinct problems, and it is unclear how specific externalizing (aggression, delinquency) and internalizing (anxiety/depression) syndromes may be uniquely related to high-risk behavior. More meaningful associations may surface in relation to distinct types of mental health problems, and this may explain the absence of effects for parent-reported broadband psychopathology.

Our analyses of direct links between narrow-band psychopathology and high-risk behavior shed light on this issue. Parent- and adolescent-reported delinquency were both related to greater drug/alcohol and needle use, but only parent-reported delinquency was related to more risky sex. As expected, youth-reported aggression predicted more risky sex, but it was surprisingly unrelated to drug/alcohol or needle use, and parent-reported aggression was associated with less drug/alcohol and needle use. There is extensive evidence that delinquency is part of a larger “deviance syndrome” (Jessor, 1991; Jessor and Jessor, 1977) that includes drug/alcohol use, needle use, and risky sex, but few studies distinguish aggression from delinquency, and findings may not generalize to aggressive youths. Indeed, our data suggest that aggression and delinquency are uniquely associated with risky behavior. The absence of association between greater aggression and needle use and drug/alcohol use, while initially surprising, is understandable. Adolescent delinquency and drug/alcohol use often occur in a social context (Brown et al., 1997b; Miller et al., 2000), but aggressive youths are frequently rejected by peers (Dodge et al., 1991; Little and Garber, 1995) and therefore have less opportunity to engage in these risk behaviors. However, the positive relation between aggression and risky sex may be explained by more nonconsensual sex among aggressive youths, or by the fact that aggressive youths are more impulsive, and impulsivity is associated with more risky sex (DiClemente et al., 1996). These data offer further evidence for specificity at the narrow-band level, underscoring the importance of differentiating related but unique problems (i.e., aggression and delinquency) in understanding high-risk behavior. Increasing specificity by carefully defining and measuring study variables and target behaviors will allow interventionists to address multiple risk behaviors and to tailor programs for youths with particular problems like delinquency.

Our tests of mediation models help clarify the process through which psychopathology influences AIDS-risk behavior. Analyses yielded a highly consistent pattern: in all but one case, peer influence mediated the effects of psychopathology on AIDS-risk. The effects of peer influence on adolescent risk behavior are reported elsewhere (Brown et al., 1997a), but this study extends the research to teenagers receiving psychiatric care and underscores the central role of peers in troubled youths’ high-risk behavior, especially for delinquent teenagers. Because these data are cross-sectional, it is possible that associating with peers who support risky behavior increases the likelihood that youths will be delinquent and that this delinquency will lead to high-risk behavior (i.e., delinquency mediates the relation between peer influence and risky behavior). When imposed on our data, however, this alternative model fit much worse than the initial model for both adolescent reports and parent reports of both broad-band and narrow-band psychopathology. Thus it appears more likely that delinquent youths are influenced by peers who support risky behavior and that, at least partly because of this support, they engage in risky behaviors. Our results are also consistent with evidence that socialized conduct disorder is part of a delinquency profile. Clinically referred youths often have strained interpersonal relationships, and delinquency is associated with low levels of parental monitoring and supervision, coercive family interactions, and family disengagement (Dishion et al., 1993; Loeber, 1990). Troubled youths may engage in high-risk behavior to obtain or maintain peer approval in the absence of guidance and support at home.

Limitations

This was a pilot study, thus results should be interpreted cautiously in light of the relatively low statistical power afforded by the modest sample size. Given the sample size (N = 86), power was 0.60 to detect a medium effect of d = 0.50 with a two-tailed test with α set at .05 (Borenstein and Cohen, 1988; Cohen, 1988). Despite low statistical power, effects were generally of moderate strength, and goodness-of-fit statistics indicated that the models captured nearly all of the available information in the sample covariance matrix. The models tested in this research explained only a modest amount of variance in risky behavior, and, although these links are important, further research is needed to identify other factors associated with AIDS risk in troubled youths. Our results are restricted to adolescents who seek outpatient mental health services, but this group has shown itself to be at especially high risk for HIV (Brown et al., 1997b), and data are desperately needed to guide targeted AIDS prevention programs for this group. These data offer initial directions for this purpose. Findings do not apply to wards of the state, but these youths require careful study given their extensive abuse histories and evidence that abuse increases AIDS risk (Brown et al., 1997c).

Some final thoughts are notable. First, we examined HIV risk in relation to symptom counts rather than clinical diagnoses. Clinical diagnoses limit generalizability because many youths who seek outpatient services do not qualify for a clear Axis I diagnosis (indeed, 44% of our sample did not), yet teenagers are seeking help because they are symptomatic. By using symptom ratings, we were able to capture the full range of distress in our sample and represent real patients in real clinical settings. Links between risk behavior and clinical diagnoses may reveal different patterns than those found here and thus warrant future investigation. Second, HIV risk was associated with adolescent delinquency in particular, but risk among nondelinquent teenagers was also high (Table 1) and should be addressed in prevention efforts. This study offers limited insight as to why clinicians often see internalizing youths engaging in high-risk behavior, but it is possible that many of these youths have comorbid externalizing problems that put them at greater AIDS risk. Future research is needed to assess these linkages and identify potential mediators of risk for internalizing youths that were not examined in this study (e.g., family factors). Third, the absence of mediation through fear of rejection and need for intimacy was surprising, although several path coefficients barely missed statistical significance. It is still possible that these variables contribute directly to risk, however, because our study focused primarily on their role as mediators of psychopathology and risk. Furthermore, these variables might achieve statistical significance with a larger sample, but this study suggests that peer influence plays the largest mediational role. Fourth, we explored a limited number of narrow-band syndromes, and there may be unique patterns associated with other emotional and behavior problems. Future studies should assess these potentially important links. Finally, it should be emphasized that these cross-sectional data cannot determine cause-and-effect relationships, but structural equation modeling affords some confidence in the nature of effects beyond simple correlations. Longitudinal research is the next logical step to test causal relationships, and specifically to determine whether peer influence mediates effects over time or is an integral part of the deviance syndrome.

Clinical Implications

Special attention to helping disturbed youths identify and associate with positive peers and involving peer models in prevention efforts, either by including them in the intervention or by using them as group leaders, may enhance program effectiveness. Likewise, group treatment focused on modifying peer attitudes about high-risk and preventive behavior, i.e., decreasing peer support and approval for risk while increasing peer support and approval for prevention, may reduce risky behavior and increase AIDS prevention. In addition, intervening within the broader social context (Bronfenbrenner, 1986; Perrino et al., 2000), such as engaging high-risk peers and important family members in prevention efforts, may prove to be important. Increased parental involvement may diminish youths’ reliance on peers (Warr, 1994), thereby reducing high-risk behaviors. It is noteworthy that some of these strategies have been used successfully with non–clinically disturbed high-risk teenagers (Fang et al., 1998; Rotheram-Borus et al., 1995a).

This study is a critical first step in identifying and understanding AIDS-risk behavior in adolescents involved in outpatient psychiatric care. Three principal conclusions may be drawn from this research: AIDS risk is associated with adolescent psychopathology in unique and important ways, adolescent delinquency shows the strongest associations with risk behavior, and peer influence plays a pivotal role in these linkages. Findings from this pilot study highlight the complexity of factors (types of informants, kinds of risk behavior, dimensions of psychopathology) that underlie AIDS risk in troubled youths, and they offer specific directions for designing and implementing AIDS-prevention programs for this highly vulnerable subgroup.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the administrators and clinical staff at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, and participating parents and adolescents, without whose help this study would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Research was supported by NIMH (R01 MH 58545), the Warren Wright Adolescent Center, and Northwestern Memorial Hospital’s Intramural Grants Program.

References

- Achenbach T (1991), Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry

- Achenbach T, McConaughy S, Howell C. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychol Bull. 1987;101:213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DA. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol Bull. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA (1989), Structural Equations with Latent Variables New York: Wiley

- Borenstein M, Cohen J (1988), Statistical Power Analysis: A Computer Program Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: research perspectives. Dev Psychol. 1986;22:723–742. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Paikoff R (1997), Sexuality and developmental transitions during adolescence. In: Health Risks and Developmental Transactions During Adolescence, Schulenberg J, Maggs J, Hurrelmann K, eds. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp 190–219

- Brown BB, Dolcini MM, Leventhal A (1997a), Transformation in peer relationships of adolescents: implications for health-related behavior. In: Health Risks and Developmental Transactions During Adolescence, Schulenberg J, Maggs J, Hurrelmann K, eds. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp 161–189

- Brown LK, Danovsky MB, Lourie KJ, DiClemente RJ, Ponton LE. Adolescents with psychiatric disorders and the risk of HIV. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997b;36:1609–1617. doi: 10.1016/S0890-8567(09)66573-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, Kessel SM, Lourie KJ, Ford HH, Lipsitt LP. Influence of sexual abuse on HIV-related attitudes and behaviors in adolescent psychiatric inpatients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997c;36:316–322. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Mays VM. Women and AIDS-related concerns: roles for psychologists in helping the worried well. Am Psychol. 1989;44:529–535. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988), Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum

- Costa FM, Jessor R, Fortenberry JD, Donovan JE. Psychosocial conventionality, health orientation, and contraceptive use in adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 1996;18:404–416. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00192-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danovsky MB, Brown LK (1996), HIV risk in psychiatrically diagnosed adolescents. In: Kansas Conference in Clinical Child Psychology Lawrence, KS

- DiClemente RJ, Lanier MM, Horan PF, Lodico M. Comparison of AIDS knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among incarcerated adolescents and a public school sample in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 1991a;81:628–630. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.5.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Lodico M, Grinstead OA, et al. African-American adolescents residing in high-risk urban environments do use condoms: correlates and predictors of condom use among adolescents in public housing developments. Pediatrics. 1996;98:269–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Ponton LE. HIV-related risk behaviors among psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents and school-based adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:324–325. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Ponton LE, Hartley D. Prevalence and correlates of cutting behavior: risk for HIV transmission. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991b;30:725–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Ponton LE, Hartley D, McKenna A (1989), Prevalence of sexual and drug-related risk behavior among psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents. In: Troubled Adolescents and HIV Infection: Issues in Prevention and Treatment, Woodruff JO, Doherty D, Athey JG, eds. Washington, DC: Georgetown University

- Dillon WR, Goldstein M (1984), Multivariate Analysis: Methods and Applications New York: Wiley

- DiLorenzo T, Hein K (1995), Adolescents: the leading edge of the next wave of the HIV epidemic. In: Adolescent Health Problems: Behavioral Perspectives, Wallander JL, Siegel LJ, eds. New York: Guilford

- Dishion T, Patterson G, Kavanagh K (1993), An experimental test of the coercion model: linking theory, measurement, and intervention. In: Preventing Antisocial Behavior: Interventions from Birth Through Adolescence, McCord J, Tremblay R, eds. New York: Guilford, pp 253–282

- Dodge KA, Coie JD, Pettit GS, Price JM. Peer status and aggression in boys’ groups: developmental and contextual analyses. Child Dev. 1991;61:1289–1309. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcini MM, Adler NE. Perceived competencies, peer group affiliation, and risk behavior among early adolescents. Health Psychol. 1994;13:496–506. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.6.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donenberg G, Weisz J. Experimental tasks and speaker effects on parent-child interactions of aggressive and depressed/anxious children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1997;25:367–387. doi: 10.1023/a:1025733023979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling S, Johnson ME, Fisher DG. Reliability of drug users’ self-report of recent drug use. Assessment. 1994;1:382–392. [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Feldman S. The implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70:1327–1343. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Stanton B, Li A, Feigelman S, Baldwin R. Similarities in sexual activity and condom use among friends within groups before and after a risk-reduction intervention. Youth Soc. 1998;29:431–450. doi: 10.1177/0044118x98029004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flisher AJ, Kramer RA, Hoven CW, et al. Risk behavior in a community sample of children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:881–887. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200007000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillmore MR, Morrison MD, Lowery C, Baker SA. Beliefs about condoms and their association with intentions to use condoms among youths in detention. J Adolesc Health. 1994;15:228–237. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(94)90508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes CD, ed. (1987), Risking the Future: Adolescent Sexuality, Pregnancy, and Childbearing Washington, DC: National Academy Press [PubMed]

- Henggeler SW, Melton GB, Rodriguez JR (1992), Pediatric and Adolescent AIDS: Research Findings From the Social Sciences Newbury Park, CA: Sage

- Hollingshead AB (1975), Four Factor Index of Social Status New Haven, CT: Yale University Department of Sociology

- Inciardi JA, Pottieger AE, Forney MA, Chitwood DD, McBride DC. Prostitution, IV drug use, and sex for crack exchanges among serious delinquents: risks for HIV infection. Criminology. 1991;29:221–235. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Behavioral Science (1991), Denver Youth Survey Youth Interview Schedule Boulder: University of Colorado; www.colorado.edu/IBS

- Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Reductions in HIV risk-associated sexual behaviors among black male adolescents: effects of an AIDS prevention intervention. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:372–377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12:597–605. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL (1977), Problem Behavior and Psychosocial Development: A Longitudinal Study of Youth New York: Academic Press

- Joreskog KG, Sorbom DG (1996), LISREL 8: User’s Reference Guide Chicago: Scientific Software International

- Kline RB (1998), Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling New York: Guilford

- Koopman C, Rosario M, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Alcohol and drug use and sexual behaviors placing runaways at risk for HIV infection. Addictive Behav. 1994;19:95–103. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavery B, Siegel AW, Cousins JH, Rubovits DS. Adolescent risk-taking: an analysis of problem behaviors in problem children. J Exp Child Psychol. 1993;55:277–294. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1993.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little SA, Garber J. Aggression, depression, and stressful life events predicting peer rejection in children. Dev Psychopathol. 1995;7:845–856. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R. Development and risk factors of juvenile antisocial behavior and delinquency. Clin Psychol Rev. 1990;10:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama GM (1998), Basics of Structural Equation Modeling Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

- McFarlane AH, Bellisimo A, Norman GR. The role of family and peers in self-efficacy: links to depression in adolescence. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1995;65:402–410. doi: 10.1037/h0079655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MA, Alberts JK, Hecht ML, Trost MR, Krizek RL (2000), Adolescent Relationships and Drug Use Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum

- Morris RE, Baker CJ, Huscroft S (1992), Incarcerated youth at risk for HIV infection. In: Adolescents and AIDS: A Generation in Jeopardy, DiClemente RJ, ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, pp 52–71

- Morris RE, Harrison EA, Knox GW, Tromanjauser E, Marquis DK, Watts LL. Health risk behavioral survey from 39 juvenile correctional facilities in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 1995;17:334–344. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00098-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (1995), Prevalence of Drug Use in the DC Metropolitan Area Adult and Juvenile Offender Populations: 1991 Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services

- Needle R, Fisher DG, Weatherby N, et al. Reliability of self-reported HIV risk behaviors of drug users. Psychol Addict Behav. 1995;9:242–250. [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Gonzalez-Soldevilla A, Pantin G, Szapocnik J. The role of families in adolescent HIV prevention: a review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2000;3:81–96. doi: 10.1023/a:1009571518900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer D, Black M, Ricardo I, et al. Social influences on the sexual behavior of youth at risk of HIV exposure. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:977–985. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.6.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Becker JV, Koopman C, Kaplan M. AIDS knowledge and beliefs, and sexual behavior of sexually delinquent and non-delinquent (runaway) adolescents. J Adolescence. 1991;14:229–244. doi: 10.1016/0140-1971(91)90018-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Koopman C. Sexual risk behaviors, AIDS knowledge, and beliefs about AIDS among runaways. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:208–210. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.2.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Koopman C, Bradley J (1989), Barriers to successful AIDS prevention programs with runaway youth. In: Troubled Adolescents and HIV Infection: Issues in Prevention and Treatment, Woodruff JO, Doherty D, Athey JG, eds. Washington, DC: Georgetown University

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Mahler KA, Rosario M. AIDS prevention with adolescents. AIDS Education Prev. 1995a;7:320–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Rosario M, Reid H, Koopman C. Predicting patterns of sexual acts among homosexual and bisexual youth. Am J Psychiatry. 1995b;152:588–595. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.4.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson CA, Cantor N. Social dating goals in late adolescence: implications for safer sexual activity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;68:1121–1134. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S, McKinney K (1987), Barriers in the initiation of intimate heterosexual relationships and strategies for intervention. J Soc Work Hum Sexuality 5:97–110 (special issue: Intimate Relationships: Some Social Work Perspectives on Love)

- Stiffman AR, Cunningham R (1991), The epidemiology of child and adolescent mental health disorders. In: National Association of Deans and Directors of Schools of Social Work, Gibbs JT, ed. Berkeley: University of California Press

- Stiffman AR, Dore P, Earls F, Cunningham R. The influence of mental health problems on AIDS-related risk behaviors in young adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180:314–320. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubman JG, Windle M, Windle RC. Cumulative sexual intercourse patterns among middle adolescents: problem behavior precursors and concurrent health risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 1996;18:182–191. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00128-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warr M. Parents, peers, and delinquency. Soc Forces. 1994;72:247–264. [Google Scholar]

- Watters JK (1994), Street Youth at Risk for AIDS (final report). Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse

- Weatherby NL, Needle R, Cesari H. Validity of self-reported drug use among injection drug users and crack cocaine users recruited through street outreach. Educ Program Plann. 1994;17:347–355. [Google Scholar]

- Weber FT, Elfenbein DS, Richards NL, Davis AB, Thomas J. Early sexual activity of delinquent adolescents. J Adolesc Health Care. 1989;10:398–403. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(89)90218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Conger RD, Kao M. The influence of parental support, depressed affect, and peers on the sexual behaviors of adolescent girls. J Fam Issues. 1993;14:261–278. [Google Scholar]