Summary

The macrophage lineage displays extreme functional and phenotypic heterogeneity which appears to due in large part to the ability of macrophages to functionally adapt to changes in their tissue microenvironment. This functional plasticity plays a critical role in their ability to respond to tissue damage and/or infection and to contribute to clearance of damaged tissue and invading microorganisms, to contribute to recruitment of the adaptive immune system, and to contribute to resolution of the wound and of the immune response. Evidence has accumulated that environmental influences, such as stromal function and imbalances in hormones and cytokines, contribute significantly to the dysfunction of the adaptive immune system. The innate immune sytem also appears to be dysfunctional in aged animals and humans. Herein, the hypothesis is presented and discussed that the observed age-associated “dysfunction” of macrophages is the result of their functional adaptation to the age-associated changes in tissue environments. The resultant loss of orchestration of the manifold functional capabilities of macrophages would undermine the efficacy of both the innate and adaptive immune systems. If the macrophages maintain functional plasticity during this dysregulation, they would be a prime target of cytokine therapy that could enhance both innate and adaptive immune systems.

Introduction

It is well documented that both the T lymphocyte and B lymphocyte compartments of the adaptive immune system deteriorate progressively with advancing age (1–6). Research is now focused on the mechanisms underlying that deterioration and on whether function can be enhanced at least transiently (1,5,7–9). The impact of advancing age on the innate immune system still remains to be resolved. The views expressed in previous reviews of the subject range from the opinion that the innate system is not significantly impacted by aging (6) to the opinion that all components of the innate system are significantly impacted (10). The following review focuses on the impact of advancing age on macrophage function. An overview of macrophage biology is presented with an emphasis on the ability of macrophages to functionally adapt to changes in microenvironmental signals. The literature on the impact of aging on macrophages is then reviewed in the context of the hypothesis that macrophage function changes with age in response to age-related changes in tissue environment. The implications of the hypothesis are that macrophage function may change with age in a tissue specific manner, that changes in macrophage function may contribute significantly to decreased clearance of microorganisms and decreased responsiveness of the adaptive immune system, and that these changes in macrophage function may be reversible, at least transiently.

Macrophage Biology: Functional Adaptability to Diverse Signaling Environments

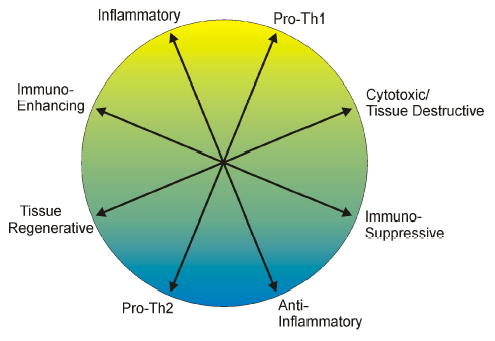

Macrophages can produce an impressive array of cytokines, chemokines, enzymes, arachidonic acid metabolites, and reactive radicals upon activation. Many of these functions appear to antagonize or counter each other. Macrophages can clearly enhance or suppress adaptive immune responses (7,11–21). Macrophages display both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory functions (22–24), produce tissue debriding metalloproteinases and inhibitors of these metalloproteinases (25–27), and produce toxic radicals that contribute to tissue cell destruction as well as cytokines that promote tissue regeneration and wound healing (23,24,28,28–31). All of these functions are not expressed simultaneously but are thought to be regulated such that macrophages display a balanced, harmonious pattern of functions (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Macrophages display a harmonious balance of functions.

Macrophages are capable of displaying many different functional activities, many of which are antagonistic. It is hypothesized that modulating influences such as cytokines, stress hormones, and other factors coordinate the level of expression of each function as well as the balance between the functions.

Multiple roles of macrophages in the inflammatory response

In the classic acute inflammatory response, blood monocytes enter the damaged tissue shortly after neutrophils. Encounter with bacteria, their products, an damaged tissue results in the activation of pro-inflammatory activities, such as the production of TNFα, IL-1, and IL-6 and the secretion of metalloproteinases. As tissue debridement and clearance of bacteria proceed, the stimulus for inflammatory and effector activities at the cleared tissue sites decreases. This decrease in stimulus for inflammatory activity, coupled with the presence of many other factors such as acute phase proteins, glucocorticoids, TGFβ, IL-10, and the phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils, contributes to the down regulation of macrophage inflammatory/cytotoxic activities and the enhanced expression of anti-inflammatory and tissue regenerative activities (28,29,32–34). Thus, during a dynamic inflammatory response, the macrophage population will display a variety of functional patterns, depending on the balance of macrophage modulating ligands present in the tissue microenvironment (24,35).

In addition to the inflammatory, debridement, clearance and tissue regenerative activities mentioned above, macrophages also play a critical liaison role in the communication between the innate and adaptive immune systems. Macrophages can display antigen presenting activity and phenotype (13) and the inflammatory milieu created by macrophages can significantly impact the maturation of myeloid dendritic cells and thus influence the nature of the adaptive immune response that will be elicited (11,30,36). If the invading microorganisms display sufficient virulence to resist clearance by the macrophages, the inflammatory process will be prolonged. T lymphocytes, recruited by macrophage-derived chemokines, will enter the infected tissue site and, if activated, their function will influence the pattern of activities displayed by the macrophages. Thus a function-polarizing synergy can develop between T cells and macrophages wherein the functional pattern displayed by the macrophages influences the nature of the adaptive immune response and the nature of the adaptive immune response (Th1 versus Th2) influences the functional pattern displayed by the macrophages. Th1 cytokines, such as IFNγ and TNFα, promote inflammatory and cytotoxic activities of macrophages. In contrast, Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-10, promote anti-inflammatory and/or tissue regenerative activities (22–24,31,37,38).

Macrophage functional subsets: harmonious patterns of function

Ligation of surface receptors such as CD40, TNFαR, or Toll-like receptors (TLR) on macrophages initiates signal cascades that provide a strong activating stimulus for macrophage function (32,39–49). However, which genes are expressed and the level of expression induced by receptor ligation is strongly influenced by other “modifying” signals in the environment. It was determined decades ago that IFNγ treatment of macrophages strongly upregulated the inflammatory cytokine and cytotoxic effector responses elicited by LPS stimulation (50–52). It has since been demonstrated that IFNγ does not simply amplify all macrophages functions across the board. IFNγ selectively upregulates LPS-induced inflammatory cytokine production and iNOS and oxidase expression while down-regulating other functions, such as arginase and PGE2 and LTC4 production (23,24,31,32,53–57). Similarly, early studies on the impact of IL-4, IL-10, and/or TGFβ on macrophage activation by LPS focused on production of inflammatory cytokines or oxidative radicals and thus determined that these cytokines inhibited or “deactivated” macrophages (24,32,54,58–65). However, closer scrutiny revealed that IL-4, IL-10 and TGFβ, like IFNγ, exerted a selective effect on macrophage functions induced by LPS, down-regulating the expression of some genes but upregulating other genes (22–24,57,66,67).

Twelve years ago, Stein et al. (68) published a seminal report establishing that IL-4 “…induces inflammatory macrophages to adopt an alternative activation phenotype, distinct from that induced by IFN-gamma, characterized by a high capacity for endocytic clearance of mannosylated ligands, enhanced (albeit restricted) MHC class II antigen expression, and reduced proinflammatory cytokine secretion.” The concept of an alternative functional phenotype for macrophages was rapidly embraced by many immunologists. The functions which were upregulated by IL-4 soon was expanded to include increased expression of CD23 in addition to the increased expression of mannose receptor and class II MHC, increased production of select chemokines such as CCL18, CCL22, and CCL17, increased production of IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), and increased expression of arginase and 12,15-lipooxygenase (reviewed in ref. (23)).

Recently, Anderson et al. (14,15,69) described a third functional phenotype of macrophages that was clearly distinct from either classically or alternatively activated macrophages. Ligation of FcγR on macrophages prior toactivation of the macrophages with LPS resulting in enhanced IL-10 production and a dramatic decrease in IL-12 production with only moderate effects on the production of other inflammatory cytokines (22,69). Impressively, targeting antigen to FcγR on APC, either by injecting IgG complexed antigen or macrophages coated with complexes of IgG-bound antigen, resulting in strong bias toward Th2 development and away from Th1 development (14,15,70). Perhaps the most important aspect of these studies, in addition to defining unique functional pattern displayed by macrophages, is that ligation of a surface receptor, FcγR, can reverse or modulate the impact of microbial products on Th1/Th2 biasing of the adaptive immune response.

The research literature actually contains many demonstrations of unique functional phenotypes of macrophages. Considering that IFNγ, IL-4, and FcRγR ligation all selectively alter the response pattern induced by LPS stimulation of macrophages, then the functional phenotype induced by LPS stimulation in the absence of those co-stimulants need be considered the fourth (or first?) unique functional phenotype displayed by macrophages. Engulfment of apoptotic neutrophils enhances production of TGFβ and VEGF while reducing LPS-induced production of TNFα, IL-12, and IL-10 (29,33,34). Ligation of the different TLR results in distinctly different patterns of gene expression (48), which yields several more unique patterns of function. Cross-talk between TLR further modifies the signaling cascade, such that ligation of multiple TLR may result in distinctive patterns of gene expression (71). Do IL-4 and IFNγ promote the same alternative and classical functional phenotypes when ligation of TLR other than TLR4 are the activating stimulus? This question has yet to be explored and the answer is likely to reveal additional functional patterns within the repertoire of macrophages.

Gene array analyses have indicated that LPS activation of macrophages induces the expression of more than 250 genes (72–74). One of these studies reported that IL-10 repressed expression of 62 of these genes and enhanced expression of 15 others (72). Another research group reported a gene array study that indicated that the pattern of gene expression elicited by IL-4, IL-10, and TGFβ were distinctly unique (73). A third group has demonstrated that the pattern of gene expression induced by LPS stimulus alone is unique in 4 different strains of mice tested (74). This latter observation is not surprising. Up to this point, the biological response modifiers of macrophage functional phenotypes has been relatively restricted to a few cytokines and TLR. In fact there a many, many physiological factors that significantly impact macrophage function and thus the functional phenotypes displayed upon activation. To mention a few, macrophage function is significantly modified by glucocorticoids and catecholamines (75–78), complement and Fc receptors (22,47,79–87), TLR and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (Nod) proteins (48,49,71,88–90), peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPAR) (91–93) and fatty acid binding proteins (FABP) (94,95), integrins (43,96–99), arachidonic acid metabolites (100–102), histamine (103,104), insulin (105,105,106), and uptake of apoptotic cells (29,33,34). The general effects of these agents on macrophages are summarized in Table 1. The point that needs to be made here is that given the large number of activating receptors on macrophages (CD40-family, TLR family, Nod family, etc.), the even larger array of physiological factors that influence the functional phenotype displayed by the activated macrophages, and the evidence for crosstalk between both the activating receptors and the signal modifying physiological factors, it is evident that the number of unique functional patterns or phenotypes macrophages are capable of displaying could be huge.

Table 1.

Ligands and receptors selectively modulating function patterns expressed by macrophages

| Ligand/Receptor | Functional Impact | References |

|---|---|---|

| TLR & Nod | Selectively stimulate distinct patterns of macrophage function | 48,49,71,88–90 |

| TNFα-R family | Selectively stimulate distinct functional patterns, emphasizing inflammatory function | 39,40,46,184–188 |

| Cytokines | Each cytokine appears to have a unique influence on macrophage function | 22–24,31,37,57,67,72–74 |

| Complement | Ligation of complement receptors enhances inflammatory function of macrophages | 79,80,87,189 |

| Fc receptors | Ligation of different FcR reduce or enhance inflammatory function of macrophages | 22,47,82–84, 86,87, 189,190 |

| Integrins | Enhance pro-inflammatory activities and macrophage emigration | 43,96,97,191 |

| Arachidonic Acid metabolites | Selectively decrease inflammatory cytokine production by macrophages | 100–102 |

| Stress hormones (glucocorticoids and catecholamines) | Differentially inhibit inflammatory cytokines and NO release and enhance IL-10 production | 75–78 |

| PPAR | Selectively inhibit pro-inflammatory functions of macrophages | 91–93 |

| FABP (aP2) | Selectively enhance pro-inflammatory activities | 94,95 |

| Histamine | Selectively inhibits production of some inflammatory cytokines and enhances production of IL-10 | 103,104 |

| Insulin | Augments alternative activation of macrophages by IL-4 | 105,106 |

| IGF | Enhances inflammatory cytokine production | 192 |

| Apoptotic Cells | Engulfment differentially down-regulates some inflammatory functions and differentially upregulates some anti-inflammatory functions and pro-wound resolution activities | 29,33,34 |

Macrophage subsets: differentiation or differential regulation?

It has been general opinion for several decades that the macrophage lineage contains several developmentally distinct sublineages, the most frequently used examples being tissue-specific macrophages such as Kupffer cells and microglial cells (107–109). Whether the alternatively and classically activated macrophage subsets described above also represent developmentally stable subsets (e.g., distinct sublineages) has been implied but has not been formally established. It is clear that chronic infections result in the accumulation of macrophages with distinctive functional characteristics dependent on whether a Th1 or Th2 immune response has been elicited (23,110–114). Thus schistosome and nematode infections that elicit a strong Th2 response also result in infiltrates of macrophages which display some of the characteristics of “alternatively activated” macrophages, such as expression of arginase (110–112). In contrast, toxoplasma and mycobacterial infections, which elicit strong Th1 responses, result in the accumulation of macrophages displaying classical inflammatory and cytotoxic activities (23,113,114). The macrophages which are associated with metastatic tumors usually display an anti-inflammatory, pro-angiogenic functional phenotype (21,115). Do these represent distinct developmentally stable subsets of macrophages or do they represent differential regulation of macrophage function by the different diseased environments? In support of the hypothesis that they represent distinct myeloid sublineages, a number of experiments suggest that clonal variation may exist in myeloid precursors and that responsiveness to select stimuli is acquired and lost during developmental progression of monoblasts to monocytes (116–119). Different strains of mice, even with congenital absence of lymphocytes, display distinct macrophage functional patterns which some investigators have catalogued into “type 1” and “type2” subsets (31). The development of “type 1” and “type 2” macrophages in the absence of lymphocytes has been used as an argument against differential regulation as being the basis for macrophage functional bias. However, gene array analysis has revealed that macrophages from the 3 strains of mice studied (intact, not lymphocyte deficient) display unique functional patterns which only partially overlap with each other (74). In addition, lymphocyte derived cytokines are not the only factors that influence macrophage function. They represent only one of the twelve modulating factors listed in Table 1. Therefore, it can be argued that the different pattern of functional response to a given stimulus by macrophages from mice of different genetic backgrounds may be the result of congenital differences in the basal level of expression of, or responsiveness to, one or more of the modulating agents listed in Table 1 (e.g., congenital basal level of insulin-like growth factor, insulin, histamine, stress hormones, etc.).

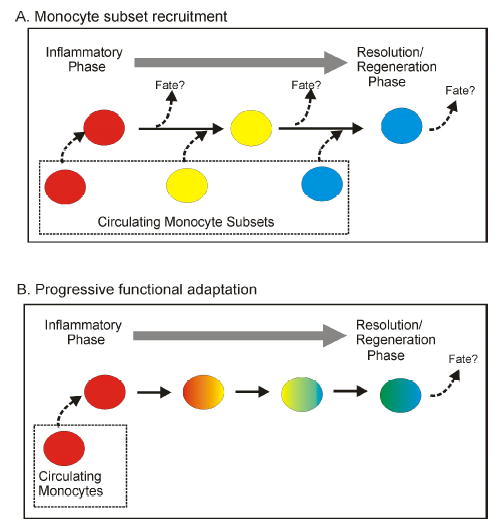

In support of a role for differential regulation in the functional heterogeneity of macrophages are the observations that the functional pattern displayed by macrophages is very plastic and mutable. The functional pattern displayed by macrophages treated with IL-4 depends on whether the macrophages were treated with IL-4 prior to or concurrently with the activating signal. Thus, prior treatment with IL-4 results in elevated TNFα and reduced IL-10 production upon LPS stimulation whereas the opposite result is obtained if IL-4 treatment is concurrent with LPS stimulation (66,120). We have shown the same temporal impact applies to the effects of treatment of macrophages with IL-10 or with IFNγ (Stout et al., submitted for publication). More directly to the point, a variety of macrophage populations, including peritoneal macrophages, bone marrow derived macrophages, splenic macrophages, and transformed macrophage lines, can be sequentially converted from one functional phenotype to a second phenotype to a third phenotype by sequentially altering the in vitro cytokine environment (Stout et al., submitted for publication). This is not without precedent in vivo. It appears that the “suppressor” macrophage subset which accumulates in tumor bearing mice can be targeted by cytokine therapy and induced to display inflammatory function [3567, Watkins and Stout, unpublished data]. Tissues macrophages which are considered specialized sublineages of macrophages, such as alveolar macrophages, Kupffer cells and microglia, can change their functional pattern, as evidenced by the response to infectious or inflammatory insult (107–109,121). Microglia display a unique ramified morphology in the brain and support neuronal survival by producing cytokines such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor and TGFβ (109,121). In vitro or during inflammatory responses in the brain, microglia lose their characteristic morphology and become migratory macrophages producing oxidative radicals and inflammatory cytokines (108,122). Even myeloid dendritic cells have been shown, in vitro and in vivo, to change into a surface and functional phenotype more characteristic of macrophages, including nitric oxide production and loss of expression of their defining membrane protein, CD11c (13,16,17). Whether these specialized macrophage subsets are differentially regulated in a reversible fashion or represent differentiated sublineages with a limited degree of functional plasticity has not been established. The level of functional adaptivity or plasticity displayed by the macrophage lineage(s) needs to be directly and formally tested. Whether the different functional patterns displayed by macrophages represent development of stable subsets or reversible differential regulation impacts our perception of the mechanics of both acute and chronic inflammation. During the progression of acute inflammation, are precursors for the inflammatory subset recruited first, followed later by recruitment of precursors for the functional subset that promotes healing or are common precursors recruited that, during the course of the response, shift their function from inflammatory/cytotoxic to wound resolution in response to changes in the tissue environment (Fig. 2)? Are the macrophage subsets which accumulate in chronic responses, such as occurs with cancer or nematode infections, stably differentiated or can their function be changed by appropriate alteration of the signaling environment? The answers to these questions will formulate how we address therapeutic intervention in reducing inflammatory dysfunction in the elderly.

Figure 2. Macrophages can functionally adapt to their tissue environment.

It is not clear to what degree the functional heterogeneity of macrophages results from differentiation into sublineages or results from differential regulation by microenvironmental signals in the tissue. It is hypothesized that in many cases, including inflammation and development of at least some tissue histiocyte characteristics, macrophages can progress through a series of functional patterns, adapting to progressive changes that occur in damaged or infected tissue.

Immunosenescence in the macrophage lineage

The inflammatory response in aged rodents and humans

Although chronic inflammatory pathologies are common in the elderly (123–129), the inflammatory response appears to lack normal orchestration, which reduces its overall efficacy in the context of infectious disease and wound healing. Reports on the impact of advanced age on the recruitment of monocytes into excisional wound sites vary from observations of no significant effect to observations of long delays in attainment of peak monocyte numbers (10,130–132). Chemotactic activity decreases with advanced age, as does macrophage production of chemokines such as MIP-1α/β and MIP-2 (131,133). Phagocytosis and clearance of infectious organisms is also reduced with advanced age (131,134–137). Expression of class II MHC and antigen presentation by macrophages have been reported to be reduced in aged rodents and humans (138–142). The production of fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), epithelial growth factor (EGF), and transforming growth factor-beta (TGFβ-3) are reduced and/or delayed, as is the expression of their corresponding receptors (132,143). The result is a delay and/or deficiency in re-epithelialization, collagen deposition, and angiogenesis in excisional wounds of the elderly. All of these deficiencies in the inflammatory response are not due solely to deficiencies in macrophage inflammatory function. The tissue itself contributes to the disharmonious response. The expression of cell adhesion molecules on the vascular endothelium is decreased in the elderly (130) and responsiveness (receptor expression) to VEGF and EGF is reduced (143,144). Thus the communication between the tissue cells and the innate immune system appears to be impaired. Given the functional adaptibility of macrophages and their dependency on environmental (tissue-derived) signals to orchestrate the progression of their functional response, this disruption of communication likely contributes significantly to the observed functional “deficiencies” in macrophages participating in inflammatory responses in the elderly.

The impact of aging on macrophage function

Although inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 are elevated in the plasma of aged animals and humans (123,145), the production of inflammatory cytokines by peritoneal macrophages from mice and rats decreases with age. Stimulation of macrophages from aged rodents with LPS results in significantly lower production of IL-1 (146,147), TNFα (10,147–149), and IL-6 (10,148), as well as lower production of chemokines such as MIP-1α and MIP-1β (131) compared to macrophages from young rodents. The production of oxidative radicals also appears to decline with age. The expression of iNOS and production of nitric oxide is reduced in macrophages from aged rodents (10,150–156). Similarly the generation of reactive oxygen intermediates (oxidative burst) is lower in peritoneal macrophages from aged rodents compared to young rodents (10,151,155–158). There is some controversy concerning the basis for the decline in production of inflammatory cytokines and oxidative radicals in response to LPS stimulation. Renshaw et al. (159) reported that the expression of TLR on macrophages was reduced with advancing age and that this was the basis for the reduced cytokine production upon stimulation with LPS. Boehmer et al. (148) reported that TLR expression was not impacted by advanced age and that the basis for the reduced cytokine production was impaired intracellular signaling, specifically a reduction in LPS-induced phosphorylation of the p38 and JNK mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPK). One point that need be held to the forefront is that the overall responsiveness of macrophages to LPS stimulation is not reduced. The influence of aging appears to be selective. Macrophages from aged mice have increased levels of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and produce elevated levels of PGE2 upon stimulation with LPS (160,161). LPS induction of IL-10 production also appears to be elevated in macrophages from aged rodents and humans (162,163). It thus appears that aging selectively impacts LPS-induced signaling cascades such that some functions are depressed and others are elevated. Another example of a signaling deficiency that appears in advanced age is responsiveness to IFNγ. Although expression of the receptor for IFNγ appears to be normal (156), IFNγ-induced phosphorylation of MAPK and STAT-1 is reduced in aged rodents (156,164). Part of this deficiency is due to IFNγ-independent decrease to total STAT-1 protein in macrophages from aged rodents (164). The basis of this reduced STAT-1 level in macrophages from aged rodents has not been resolved.

Another indication that age-associated factors are differentially, and possibly indirectly, impacting macrophage function is that aging impacts macrophages in different tissues differently. The degree to which production of inflammatory cytokines and oxidative radicals are impacted by aging vary when macrophages from bone marrow, spleen, alveoli, and peritoneum are compared (74,147,165–168). This suggests that part of the deficiency observed in macrophages from aged animals and humans might be caused by changes in the tissue environment. It is known that the stromal environments of bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes and thymus change with age, resulting in reduced hematopoiesis, thymopoiesis, and peripheral homeostasis (1–5,169–176). Although myeloid dendritic cells in aged rodents and humans appear to be poorly immunogenic (8,10,141,142), fully functional myeloid dendritic cells can be generated in vitro from blood monocytes from aged donors (177). Macrophages generated in vitro from bone marrow cells from aged mice respond identically to macrophages generated from bone marrow from young mice, indicating that there is no age-associated intrinsic defect in the lineage (178). The function of many of the myeloid and lymphoid cells in aged animals can be at least transiently improved by a variety of treatments. IL-7 provides a burst of thymopoietic activity (5). Inflammatory cytokine therapy seems to improve antigen presentation and T cell responses in aged mice (7). Treatment of macrophages from aged donors with IFNγ (56) or with insulin-like growth factor (IGF) (179) significantly improves their inflammatory and effector responses to LPS stimulation. Our group has recently demonstrated that functional balance can be restored in macrophages from aged mice by removing them from the aged environment (Matta et al., manuscript in preparation).

Concluding Remarks

Given the above discussion of the evidence supporting the exquisite functional adaptability of macrophages to environmental changes, the evidence that aging impacts tissue environments, and that age-related changes in macrophage function may be reversible rather than intrinsic, it is suggested that targeting the regulatory factors of the aged environment might restore, at least transiently, the inflammatory and proimmunogenic function of macrophages in the elderly. The problem is that the age-associated factors altering macrophage function are unidentified and may be very numerous (Table 1). Oxidative stress is hypothesized to alter transcription factors (e.g., NFkB) an nuclear receptors (e.g., PPAR’s) and thus alter the ability of macrophages to respond to inflammatory stimuli (180). Anti-oxidants do seem to improve macrophage inflammatory function (161,181,182). Neuroendocrine factors and stress hormones have also been hypothesized to contribute to the immunosenescence and decreased macrophage function (123,183). One approach being used in cancer therapy may also have applicability in age-associated inflammatory deficiencies and that is to target macrophages with cytokines that promote the desired macrophage function (21). The disruption of macrophage functional homeostasis that appears with aging may seem excessively complex. But one fact made clear by Haynes et al. (7), who reported that administration of inflammatory cytokines of the innate immune system enhanced the adaptive immune response of aged mice, is that restoration of the functional balance of macrophages in the elderly will not only improve innate responses but, as a result, improve the function of the adaptive immune system, as well. Given the critical need for improvement of vaccine efficacy and control of infectious disease in the elderly, more research emphasis on the impact of aging on the macrophages and macrophage-derived dendritic cells is clearly needed.

References

- 1.Linton PJ, Haynes L, Tsui L, Zhang X, Swain S. From naive to effector--alterations with aging. Immunol Rev. 1997;160:9–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linton PJ, Haynes L, Klinman NR, Swain SL. Antigen-independent changes in naive CD4 T cells with aging. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1891–1900. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu A, Ehleiter D, Ben Yehuda A, Schwab R, Russo C, Szabo P, Weksler ME. Effect of age on the expressed B cell repertoire: role of B cell subsets. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1035–1039. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.9.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson SA, Cambier JC. Ageing, autoimmunity and arthritis: senescence of the B cell compartment - implications for humoral immunity. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:131–139. doi: 10.1186/ar1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beverley PC, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Is immune senescence reversible? Vaccine. 2000;18:1721–1724. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franceschi C, Bonafe M, Valensin S. Human immunosenescence: the prevailing of innate immunity, the failing of clonotypic immunity, and the filling of immunological space. Vaccine. 2000;18:1717–1720. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00513-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haynes L, Eaton SM, Burns EM, Rincon M, Swain SL. Inflammatory cytokines overcome age-related defects in CD4 T cell responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2004;172:5194–5199. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uyemura K, Castle SC, Makinodan T. The frail elderly: role of dendritic cells in the susceptibility of infection. Mech Ageing Dev. 2002;123:955–962. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(02)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia GG, Miller RA. Age-related defects in CD4+ T cell activation reversed by glycoprotein endopeptidase. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:3464–3472. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plackett TP, Boehmer ED, Faunce DE, Kovacs EJ. Aging and innate immune cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:291–299. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unanue ER. Studies in listeriosis show the strong symbiosis between the innate cellular system and the T-cell response. Immunol Rev. 1997;158:11–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams K, Dooley N, Ulvestad E, Becher B, Antel JP. IL-10 production by adult human derived microglial cells. Neurochem Int. 1996;29:55–64. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(95)00138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hausser G, Ludewig B, Gelderblom HR, Tsunetsugu-Yokota Y, Akagawa K, Meyerhans A. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells represent a transient stage of differentiation in the myeloid lineage. Immunobiology. 1997;197:534–542. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(97)80085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson CF, Mosser DM. A novel phenotype for an activated macrophage: the type 2 activated macrophage. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:101–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson CF, Mosser DM. Cutting edge: biasing immune responses by directing antigen to macrophage Fc gamma receptors. J Immunol. 2002;168:3697–3701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shortman K, Wu L. Are dendritic cells end cells? Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1105–1106. doi: 10.1038/ni1104-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang M, Tang H, Guo Z, An H, Zhu X, Song W, Guo J, Huang X, Chen T, Wang J, Cao X. Splenic stroma drives mature dendritic cells to differentiate into regulatory dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1124–1133. doi: 10.1038/ni1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu D, Meydani SN. Mechanism of age-associated upregulation in macrophage PGE2 synthesis. Brain Behav Immun. 2004;18:487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Apolloni E, Bronte V, Mazzoni A, Serafini P, Cabrelle A, Segal DM, Young HA, Zanovello P. Immortalized myeloid suppressor cells trigger apoptosis in antigen- activated T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2000;165:6723–6730. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koblish HK, Hunter CA, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Lee WM. Immune suppression by recombinant interleukin (rIL)-12 involves interferon gamma induction of nitric oxide synthase 2 (iNOS) activity: inhibitors of NO generation reveal the extent of rIL-12 vaccine adjuvant effect. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1603–1610. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.9.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bingle L, Brown NJ, Lewis CE. The role of tumour-associated macrophages in tumour progression: implications for new anticancer therapies. J Pathol. 2002;196:254–265. doi: 10.1002/path.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mosser DM. The many faces of macrophage activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:209–212. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0602325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stout RD, Suttles J. Functional plasticity of macrophages: reversible adaptation to changing microenvironments. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:509–513. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0504272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lacraz S, Nicod LP, Chicheportiche R, Welgus HG, Dayer JM. IL-10 inhibits metalloproteinase and stimulates TIMP-1 production in human mononuclear phagocytes. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2304–2310. doi: 10.1172/JCI118286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacraz S, Nicod L, Galve-de Rochemonteix B, Baumberger C, Dayer JM, Welgus HG. Suppression of metalloproteinase biosynthesis in human alveolar macrophages by interleukin-4. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:382–388. doi: 10.1172/JCI115872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mostafa ME, Chollet-Martin S, Oudghiri M, Laquay N, Jacob MP, Michel JB, Feldman LJ. Effects of interleukin-10 on monocyte/endothelial cell adhesion and MMP- 9/TIMP-1 secretion. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:882–890. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diegelmann RF, Evans MC. Wound healing: an overview of acute, fibrotic and delayed healing. Front Biosci. 2004;9:283–289. doi: 10.2741/1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucas M, Stuart LM, Savill J, Lacy-Hulbert A. Apoptotic cells and innate immune stimuli combine to regulate macrophage cytokine secretion. J Immunol. 2003;171:2610–2615. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gratchev A, Schledzewski K, Guillot P, Goerdt S. Alternatively activated antigen-presenting cells: molecular repertoire, immune regulation, and healing. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol. 2001;14:272–279. doi: 10.1159/000056357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, Heilman MJ, Hill AM. M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J Immunol. 2000;164:6166–6173. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stout RD, Suttles J. T cell signaling of macrophage activation. Cell contact-dependent and cytokine signals. Austin: R. G. Landes Company; Springer-Verlag, 1995.

- 33.Golpon HA, Fadok VA, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Scerbavicius R, Sauer C, Welte T, Henson PM, Voelkel NF. Life after corpse engulfment: phagocytosis of apoptotic cells leads to VEGF secretion and cell growth. FASEB J. 2004;18:1716–1718. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1853fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cvetanovic M, Ucker DS. Innate immune discrimination of apoptotic cells: repression of proinflammatory macrophage transcription is coupled directly to specific recognition. J Immunol. 2004;172:880–889. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGrath MS, Kodelja V. Balanced macrophage activation hypothesis: a biological model for development of drugs targeted at macrophage functional states. Pathobiology. 1999;67:277–281. doi: 10.1159/000028079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allavena P, Piemonti L, Longoni D, Bernasconi S, Stoppacciaro A, Ruco L, Mantovani A. IL-10 prevents the differentiation of monocytes to dendritic cells but promotes their maturation to macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:359–369. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199801)28:01<359::AID-IMMU359>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Munder M, Eichmann K, Modolell M. Alternative metabolic states in murine macrophages reflected by the nitric oxide synthase/arginase balance: competitive regulation by CD4+ T cells correlates with Th1/Th2 phenotype. J Immunol. 1998;160:5347–5354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munder M, Eichmann K, Moran JM, Centeno F, Soler G, Modolell M. Th1/Th2-regulated expression of arginase isoforms in murine macrophages and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:3771–3777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stout RD, Suttles J. The many roles of CD40 in cell-mediated inflammatory responses. Immunol Today. 1996;17:487–492. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10060-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner DH, Stout RD, Suttles J. Role of the CD40-CD40 ligand interaction in CD4+ T cell contact-dependent activation of monocyte IL-1 synthesis. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:3148–3154. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suttles J, Evans M, Miller RW, Poe JC, Stout RD, Wahl LM. T cell rescue of monocytes from apoptosis: role of the CD40-CD40L interaction and requirement for CD40-mediated induction of protein tyrosine kinase activity. J Leukocyte Biol. 1996;60:651–657. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stout RD, Suttles J, Xu J, Grewal IS, Flavell RA. Impaired T cell-mediated macrophage activation in CD40 ligand-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1996;156:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian L, Noelle RJ, Lawrence DA. Activated T cells enhance nitric oxide production by murine splenic macrophages through gp39 and LFA-1. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:306–309. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bermudez LE, Young LS. Tumor necrosis factor alpha stimulates mycobactericidal/mycobacteriostatic activity in human macrophages by a protein kinase C-independent pathway. Cell Immunol. 1992;144:258–268. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(92)90243-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winston BW, Lange-Carter CA, Gardner AM, Johnson GL, Riches DWH. Tumor necrosis factor α rapidly activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade in a MAPK kinase kinase-dependent, c-Raf-1-independent fashion in mouse macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1614–1618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riches DW, Chan ED, Winston BW. TNF-alpha-induced regulation and signalling in macrophages. Immunobiology. 1996;195:477–490. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(96)80017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rose DM, Winston BW, Chan ED, Riches DW, Gerwins P, Johnson GL, Henson PM. Fc gamma receptor cross-linking activates p42, p38, and JNK/SAPK mitogen-activated protein kinases in murine macrophages: role for p42MAPK in Fc gamma receptor-stimulated TNF-alpha synthesis. J Immunol. 1997;158:3433–3438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vogel SN, Fitzgerald KA, Fenton MJ. TLRs: differential adapter utilization by toll-like receptors mediates TLR-specific patterns of gene expression. Mol Interv. 2003;3:466–477. doi: 10.1124/mi.3.8.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adams DO, Hamilton TA. The cell biology of macrophage activation. Ann Rev Immunol. 1984;2:283–318. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.02.040184.001435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Drysdale BE, Agaarwal S, Shin HS. Macrophage mediated tumoricidal activity: mechanisms of activation and cytotoxicity. Prog Allergy. 1988;40:111–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Collart MA, Belin D, Vassalli J-D, de Kossodo S, Vassalli P. Gamma-interferon enhances macrophage transcription of the tumor necrosis factor/cachectin, interleukin 1, and urokinase genes, which are controlled by short-lived repressors. J Exp Med. 1986;164:2113–2118. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.6.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gazzinelli RT, Oswald IP, Hieny S, James SL, Sher A. The microbicidal activity of interferon-gamma-treated macrophages against Trypanosoma cruzi involves an L-arginine- dependent, nitrogen oxide-mediated mechanism inhibitable by interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor-beta. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2501–2506. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stout RD, Suttles J. T cell signaling of macrophage function in inflammatory disease. Front Biosci. 1997;2:d197–206. doi: 10.2741/a183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nathan CF, Murray HW, Wiebe ME, Rubin BY. Identification of gamma interferon as the lymphokine that activates human macrophage oxidative metabolism and anti-bacterial activity. J Exp Med. 1983;158:670. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.3.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayakawa H, Sato A, Yagi T, Uchiyama H, Ide K, Nakano M. Superoxide generation by alveolar macrophages from aged rats: improvement by in vitro treatment with IFN-gamma. Mech Ageing Dev. 1995;80:199–211. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(95)01573-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goerdt S, Politz O, Schledzewski K, Birk R, Gratchev A, Guillot P, Hakiy N, Klemke CD, Dippel E, Kodelja V, Orfanos CE. Alternative versus classical activation of macrophages. Pathobiology. 1999;67:222–226. doi: 10.1159/000028096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bogdan C, Vodovotz Y, Nathan C. Macrophage deactivation by interleukin 10. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1549–1555. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fiorentino DF, Zlotnik A, Mosmann TR, Howard M, O’Garra A. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147:3815–3822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oswald IP, Wynn TA, Sher A, James SL. Interleukin 10 inhibits macrophage microbicidal activity by blocking the endogenous production of tumor necrosis factor alpha required as a costimulatory factor for interferon gamma-induced activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8676–8680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oswald IP, Gazzinelli RT, Sher A, James SL. IL-10 synergizes with IL-4 and transforming growth factor-beta to inhibit macrophage cytotoxic activity. J Immunol. 1992;148:3578–3582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abramson SL, Gallin JI. IL-4 inhibits superoxide production by human mononuclear phagocytes. J Immunol. 1990;144:625–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Appelberg R, Orme IM, Pinto de Sousa MI, Silva MT. In vitro effects of interleukin-4 on interferon-gamma-induced macrophage activation. Immunology. 1992;76:553–559. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cheung DL, Hart PH, Vitti GF, Whitty GA, Hamilton JA. Contrasting effects of interferon-gamma and interleukin- 4 on the interleukin-6 activity of stimulated human monocytes. Immunology. 1990;71:70–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hart PH, Vitti GF, Burgess DR, Whitty GA, Piccoli DS, Hamilton JA. Potential antiinflammatory effects of interleukin 4: suppression of human monocyte tumor necrosis factor α, interleukin 1 and prostaglandin E2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3803–3807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.D’Andrea A, Ma X, Aste Amezaga M, Paganin C, Trinchieri G. Stimulatory and inhibitory effects of interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 on the production of cytokines by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: priming for IL-12 and tumor necrosis factor alpha production. J Exp Med. 1995;181:537–546. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goerdt S, Orfanos CE. Other functions, other genes: alternative activation of antigen- presenting cells. Immunity. 1999;10:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stein M, Keshav S, Harris N, Gordon S. Interleukin 4 potently enhances murine macrophage mannose receptor activity: a marker of alternative immunologic macrophage activation. J Exp Med. 1992;176:287–292. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Anderson CF, Gerber JS, Mosser DM. Modulating macrophage function with IgG immune complexes. J Endotoxin Res. 2002;8:477–481. doi: 10.1179/096805102125001118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Anderson CF, Lucas M, Gutierrez-Kobeh L, Field AE, Mosser DM. T cell biasing by activated dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:955–961. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dobrovolskaia MA, Medvedev AE, Thomas KE, Cuesta N, Toshchakov V, Ren T, Cody MJ, Michalek SM, Rice NR, Vogel SN. Induction of in vitro reprogramming by Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 agonists in murine macrophages: effects of TLR “homotolerance” versus “heterotolerance” on NF-kappa B signaling pathway components. J Immunol. 2003;170:508–519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lang R, Patel D, Morris JJ, Rutschman RL, Murray PJ. Shaping gene expression in activated and resting primary macrophages by IL-10. J Immunol. 2002;169:2253–2263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Williams L, Jarai G, Smith A, Finan P. IL-10 expression profiling in human monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:800–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wells CA, Ravasi T, Faulkner GJ, Carninci P, Okazaki Y, Hayashizaki Y, Sweet M, Wainwright BJ, Hume DA. Genetic control of the innate immune response. BMC Immunol. 2003;4:5–23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Elenkov IJ, Chrousos GP. Stress hormones, proinflammatory and antiinflammatory cytokines, and autoimmunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;966:290–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tanaka KF, Kashima H, Suzuki H, Ono K, Sawada M. Existence of functional beta1- and beta2-adrenergic receptors on microglia. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:232–237. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zinyama RB, Bancroft GJ, Sigola LB. Adrenaline suppression of the macrophage nitric oxide response to lipopolysaccharide is associated with differential regulation of tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-10. Immunology. 2001;104:439–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01332.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lorton D, Lubahn C, Bellinger DL. Potential use of drugs that target neural-immune pathways in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2003;2:1–30. doi: 10.2174/1568010033344499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bacle F, Haeffner-Cavaillon N, Laude M, Couturier C, Kazatchkine MD. Induction of IL-1 release through stimulation of the C3b/C4b complement receptor type one (CR1, CD35) on human monocytes. J Immunol. 1990;144:147–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Medvedev AE, Flo T, Ingalls RR, Golenbock DT, Teti G, Vogel SN, Espevik T. Involvement of CD14 and complement receptors CR3 and CR4 in nuclear factor-kappaB activation and TNF production induced by lipopolysaccharide and group B streptococcal cell walls. J Immunol. 1998;160:4535–4542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lipschitz DA. Age-related declines in hematopoietic reserve capacity. Semin Oncol. 1995;22:3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yuasa T, Kubo S, Yoshino T, Ujike A, Matsumura K, Ono M, Ravetch JV, Takai T. Deletion of fcgamma receptor IIB renders H-2(b) mice susceptible to collagen-induced arthritis. J Exp Med. 1999;189:187–194. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Imamichi T, Sato H, Iwaki S, Nakamura T, Koyama J. Different abilities of two types of Fcgamma receptor on guinea-pig macrophages to trigger the intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and O2− generation. Mol Immunol. 1990;27:829–838. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(90)90148-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sutterwala FS, Noel GJ, Salgame P, Mosser DM. Reversal of proinflammatory responses by ligating the macrophage Fcgamma receptor type I. J Exp Med. 1998;188:217–222. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alonso A, Carvalho J, Alonso-Torre SR, Nunez L, Bosca L, Crespo MS. Nitric oxide synthesis in rat peritoneal macrophages is induced by IgE/DNP complexes and cyclic AMP analogues. J Immunol. 1995;154:6475–6483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Armant M, Rubio M, Delespesse G, Sarfati M. Soluble CD23 directly activates monocytes to contribute to the antigen-independent stimulation of resting T cells. J Immunol. 1995;155:4868–4875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Armant M, Ishihara H, Rubio M, Delespesse G, Sarfati M. Regulation of cytokine production by soluble CD23: costimulation of interferon-τ secretion and triggering of tumor necrosis factor-α release. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1005–1011. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Girardin SE, Philpott DJ. Mini-review: the role of peptidoglycan recognition in innate immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1777–1782. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Philpott DJ, Girardin SE. The role of Toll-like receptors and Nod proteins in bacterial infection. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Royet J, Reichhart JM. Detection of peptidoglycans by NOD proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:610–614. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chinetti G, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): nuclear receptors at the crossroads between lipid metabolism and inflammation. Inflamm Res. 2000;49:497–505. doi: 10.1007/s000110050622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ricote M, Valledor AF, Glass CK. Decoding transcriptional programs regulated by PPARs and LXRs in the macrophage: effects on lipid homeostasis, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:230–239. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000103951.67680.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ricote M, Huang JT, Welch JS, Glass CK. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor(PPARgamma) as a regulator of monocyte/macrophage function. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:733–739. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Makowski L, Boord JB, Maeda K, Babaev VR, Uysal KT, Morgan MA, Parker RA, Suttles J, Fazio S, Hotamisligil GS, Linton MF. Lack of macrophage fatty-acid-binding protein aP2 protects mice deficient in apolipoprotein E against atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2001;7:699–705. doi: 10.1038/89076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Makowski L, Hotamisligil GS. Fatty acid binding proteins--the evolutionary crossroads of inflammatory and metabolic responses. J Nutr. 2004;134:2464S–2468S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.9.2464S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bellingan GJ, Xu P, Cooksley H, Cauldwell H, Shock A, Bottoms S, Haslett C, Mutsaers SE, Laurent GJ. Adhesion molecule-dependent mechanisms regulate the rate of macrophage clearance during the resolution of peritoneal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1515–1521. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lecoanet-Henchoz S, Plater-Zyberk C, Graber P, Gretener D, Aubry JP, Conrad DH, Bonnefoy JY. Mouse CD23 regulates monocyte activation through an interaction with the adhesion molecule CD11b/CD18. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2290–2294. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schmal H, Czermak BJ, Lentsch AB, Bless NM, Beck-Schimmer B, Friedl HP, Ward PA. Soluble ICAM-1 activates lung macrophages and enhances lung injury. J Immunol. 1998;161:3685–3693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Geng Y, Zhang B, Lotz M. Protein tyrosine kinase activation is required for lipopolysaccharide induction of cytokines in human blood monocytes. J Immunol. 1993;151:6692–6700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Huang JT, Welch JS, Ricote M, Binder CJ, Willson TM, Kelly C, Witztum JL, Funk CD, Conrad D, Glass CK. Interleukin-4-dependent production of PPAR-gamma ligands in macrophages by 12/15-lipoxygenase. Nature. 1999;400:378–382. doi: 10.1038/22572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Aronoff DM, Canetti C, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits alveolar macrophage phagocytosis through an E-prostanoid 2 receptor-mediated increase in intracellular cyclic AMP. J Immunol. 2004;173:559–565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rouzer CA, Kingsley PJ, Wang H, Zhang H, Morrow JD, Dey SK, Marnett LJ. Cyclooxygenase-1-dependent prostaglandin synthesis modulates tumor necrosis factor-alpha secretion in lipopolysaccharide-challenged murine resident peritoneal macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34256–34268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Elenkov IJ, Webster E, Papanicolaou DA, Fleisher TA, Chrousos GP, Wilder RL. Histamine potently suppresses human IL-12 and stimulates IL-10 production via H2 receptors. J Immunol. 1998;161 :2586–2593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Marone G, Granata F, Spadaro G, Genovese A, Triggiani M. The histamine-cytokine network in allergic inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:S83–S88. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)01881-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liang CP, Han S, Okamoto H, Carnemolla R, Tabas I, Accili D, Tall AR. Increased CD36 protein as a response to defective insulin signaling in macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:764–773. doi: 10.1172/JCI19528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hartman ME, O’Connor JC, Godbout JP, Minor KD, Mazzocco VR, Freund GG. Insulin receptor substrate-2-dependent interleukin-4 signaling in macrophages is impaired in two models of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28045–28050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404368200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Laskin DL, Weinberger B, Laskin JD. Functional heterogeneity in liver and lung macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Guillemin GJ, Brew BJ. Microglia, macrophages, perivascular macrophages, and pericytes: a review of function and identification. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:388–397. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0303114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hanisch UK. Microglia as a source and target of cytokines. Glia. 2002;40:140–155. doi: 10.1002/glia.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hesse M, Modolell M, La Flamme AC, Schito M, Fuentes JM, Cheever AW, Pearce EJ, Wynn TA. Differential regulation of nitric oxide synthase-2 and arginase-1 by type 1/type 2 cytokines in vivo: granulomatous pathology is shaped by the pattern of L-arginine metabolism. J Immunol. 2001;167:6533–6544. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Loke P, Nair MG, Parkinson J, Guiliano D, Blaxter M, Allen JE. IL-4 dependent alternatively-activated macrophages have a distinctive in vivo gene expression phenotype. BMC Immunol. 2002;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Loke P, MacDonald AS, Robb A, Maizels RM, Allen JE. Alternatively activated macrophages induced by nematode infection inhibit proliferation via cell-to-cell contact. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30 :2669–2678. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200009)30:9<2669::AID-IMMU2669>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Steinman RM, Inaba K. Myeloid dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:205–208. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hamerman JA, Aderem A. Functional transitions in macrophages during in vivo infection with Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J Immunol. 2001;167:2227–2233. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena P, Sica A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:549–555. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rutherford MS, Witsell A, Schook LB. Mechanisms generating functionally heterogeneous macrophages: chaos revisited. J Leukoc Biol. 1993;53:602–618. doi: 10.1002/jlb.53.5.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Witsell AL, Schook LB. Macrophage heterogeneity occurs through a developmental mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:1963–1967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Takahashi K, Naito M, Takeya M. Development and heterogeneity of macrophages and their related cells through their differentiation pathways. Pathol Int. 1996;46:473–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1996.tb03641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kambayashi T, Jacob CO, Strassmann G. IL-4 and IL-13 modulate IL-10 release in endotoxin-stimulated murine peritoneal mononuclear phagocytes. Cell Immunol. 1996;171:153–158. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kempermann G, Neumann H. Neuroscience. Microglia: the enemy within? Science. 2003;302:1689–1690. doi: 10.1126/science.1092864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Liu B, Hong JS. Role of microglia in inflammation-mediated neurodegenerative diseases: mechanisms and strategies for therapeutic intervention. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:1–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.035048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Franceschi C, Bonafe M, Valensin S, Olivieri F, De Luca M, Ottaviani E, De Benedictis G. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;908:244–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kerr LD. Inflammatory arthropathy: a review of rheumatoid arthritis in older patients. Geriatrics. 2004;59:32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cassetta M, Gorevic PD. Crystal arthritis. Gout and pseudogout in the geriatric patient. Geriatrics. 2004;59 :25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Krabbe KS, Pedersen M, Bruunsgaard H. Inflammatory mediators in the elderly. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:687–699. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Casserly I, Topol E. Convergence of atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease: inflammation, cholesterol, and misfolded proteins. Lancet. 2004;363:1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15900-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hakim FT, Flomerfelt FA, Boyiadzis M, Gress RE. Aging, immunity and cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tracy RP. Emerging relationships of inflammation, cardiovascular disease and chronic diseases of aging. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27 (Suppl 3):S29–S34. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ashcroft GS, Horan MA, Ferguson MW. Aging alters the inflammatory and endothelial cell adhesion molecule profiles during human cutaneous wound healing. Lab Invest. 1998;78:47–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Swift ME, Burns AL, Gray KL, DiPietro LA. Age-related alterations in the inflammatory response to dermal injury. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1027–1035. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Swift ME, Kleinman HK, DiPietro LA. Impaired wound repair and delayed angiogenesis in aged mice. Lab Invest. 1999;79:1479–1487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ortega E, Garcia JJ, De la FM. Modulation of adherence and chemotaxis of macrophages by norepinephrine. Influence of ageing. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;203:113–117. doi: 10.1023/a:1007094614047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Antonini JM, Roberts JR, Clarke RW, Yang HM, Barger MW, Ma JY, Weissman DN. Effect of age on respiratory defense mechanisms: pulmonary bacterial clearance in Fischer 344 rats after intratracheal instillation of Listeria monocytogenes. Chest. 2001;120:240–249. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Albright JW, Albright JF. Ageing alters the competence of the immune system to control parasitic infection. Immunol Lett. 1994;40:279–285. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(94)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Bradley SF, Kauffman CA. Aging and the response to Salmonella infection. Exp Gerontol. 1990;25:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(90)90012-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Mancuso P, McNish RW, Peters-Golden M, Brock TG. Evaluation of phagocytosis and arachidonate metabolism by alveolar macrophages and recruited neutrophils from F344xBN rats of different ages. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:1899–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Seth A, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS, Subbarao B, Udhayakumar V. Macrophages but not B cells from aged mice are defective in stimulating autoreactive T cells in vitro. Mech Ageing Dev. 1990;52:107–124. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(90)90118-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Garg M, Luo W, Kaplan AM, Bondada S. Cellular basis of decreased immune responses to pneumococcal vaccines in aged mice. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4456–4462. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4456-4462.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Effros RB, Walford RL. The effect of age on the antigen-presenting mechanism in limiting dilution precursor cell frequency analysis. Cell Immunol. 1984;88:531–539. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(84)90184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Haruna H, Inaba M, Inaba K, Taketani S, Sugiura K, Fukuba Y, Doi H, Toki J, Tokunaga R, Ikehara S. Abnormalities of B cells and dendritic cells in SAMP1 mice. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1319–1325. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Zissel G, Schlaak M, Muller-Quernheim J. Age-related decrease in accessory cell function of human alveolar macrophages. J Investig Med. 1999;47:51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ashcroft GS, Horan MA, Ferguson MW. The effects of ageing on wound healing: immunolocalisation of growth factors and their receptors in a murine incisional model. J Anat. 1997;190 ( Pt 3):351–365. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1997.19030351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kraatz J, Clair L, Rodriguez JL, West MA. Macrophage TNF secretion in endotoxin tolerance: role of SAPK, p38, and MAPK. J Surg Res. 1999;83:158–164. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1999.5587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Saurwein-Teissl M, Blasko I, Zisterer K, Neuman B, Lang B, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. An imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, a characteristic feature of old age. Cytokine. 2000;12:1160–1161. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Inamizu T, Chang MP, Makinodan T. Influence of age on the production and regulation of interleukin-1 in mice. Immunology. 1985;55:447–455. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Wallace PK, Eisenstein TK, Meissler JJ, Jr, Morahan PS. Decreases in macrophage mediated antitumor activity with aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 1995;77:169–184. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(94)01524-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Boehmer ED, Goral J, Faunce DE, Kovacs EJ. Age-dependent decrease in Toll-like receptor 4-mediated proinflammatory cytokine production and mitogen-activated protein kinase expression. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:342–349. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0803389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Corsini E, Battaini F, Lucchi L, Marinovich M, Racchi M, Govoni S, Galli CL. A defective protein kinase C anchoring system underlying age-associated impairment in TNF-alpha production in rat macrophages. J Immunol. 1999;163:3468–3473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Hayakawa H, Sato A, Yagi T, Uchiyama H, Ide K, Nakano M. Superoxide generation by alveolar macrophages from aged rats: improvement by in vitro treatment with IFN-gamma. Mech Ageing Dev. 1995;80:199–211. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(95)01573-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Alvarez E, Machado A, Sobrino F, Santa MC. Nitric oxide and superoxide anion production decrease with age in resident and activated rat peritoneal macrophages. Cell Immunol. 1996;169:152–155. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Hoellman JR, Suttles J, Stout RD. Panning T cells on vascular endothelial cell monolayers: a rapid method for enriching naive T cells. Immunobiology. 2001;203:769–777. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(01)80005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Khare V, Sodhi A, Singh SM. Effect of aging on the tumoricidal functions of murine peritoneal macrophages. Nat Immun. 1996;15:285–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Kissin E, Tomasi M, McCartney-Francis N, Gibbs CL, Smith PD. Age-related decline in murine macrophage production of nitric oxide. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1004–1007. doi: 10.1086/513959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Alvarez E, Machado A, Sobrino F, Santa Maria C. Nitric oxide and superoxide anion production decrease with age in resident and activated rat peritoneal macrophages. Cell Immunol. 1996;169 :152–155. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Ding A, Hwang S, Schwab R. Effect of aging on murine macrophages. Diminished response to IFN-gamma for enhanced oxidative metabolism. J Immunol. 1994;153:2146–2152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Alvarez E, Santa MC, Machado A. Respiratory burst reaction changes with age in rat peritoneal macrophages. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1179:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Alvarez E, Conde M, Machado A, Sobrino F, Santa Maria C. Decrease in free-radical production with age in rat peritoneal macrophages. Biochem J. 1995;312:555–560. doi: 10.1042/bj3120555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Renshaw M, Rockwell J, Engleman C, Gewirtz A, Katz J, Sambhara S. Cutting edge: impaired Toll-like receptor expression and function in aging. J Immunol. 2002;169:4697–4701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Hayek MG, Mura C, Wu D, Beharka AA, Han SN, Paulson KE, Hwang D, Meydani SN. Enhanced expression of inducible cyclooxygenase with age in murine macrophages. J Immunol. 1997;159:2445–2451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Wu D, Mura C, Beharka AA, Han SN, Paulson KE, Hwang D, Meydani SN. Age-associated increase in PGE2 synthesis and COX activity in murine macrophages is reversed by vitamin E. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C661–C668. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.3.C661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Spencer NF, Norton SD, Harrison LL, Li GZ, Daynes RA. Dysregulation of IL-10 production with aging: possible linkage to the age-associated decline in DHEA and its sulfated derivative. Exp Gerontol. 1996;31:393–408. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(95)02033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Sadeghi HM, Schnelle JF, Thoma JK, Nishanian P, Fahey JL. Phenotypic and functional characteristics of circulating monocytes of elderly persons. Exp Gerontol. 1999;34:959–970. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(99)00065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Yoon P, Keylock KT, Hartman ME, Freund GG, Woods JA. Macrophage hypo-responsiveness to interferon-gamma in aged mice is associated with impaired signaling through Jak-STAT. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Kohut ML, Senchina DS, Madden KS, Martin AE, Felten DL, Moynihan JA. Age effects on macrophage function vary by tissue site, nature of stimulant, and exercise behavior. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:1347–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Shimada Y, Ito H. Heterogeneous aging of macrophage-lineage cells in the capacity for TNF production and self renewal in C57BL/6 mice. Mech Ageing Dev. 1996;87:183–195. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(96)01704-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Matsui S, Yamashita N, Mino T, Taki H, Sugiyama E, Hayashi R, Maruyama M, Kobayashi M. Role of the endogenous prostaglandin E2 in human lung fibroblast interleukin-11 production. Respir Med. 1999;93:637–642. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(99)90103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Wang CQ, Udupa KB, Xiao H, Lipschitz DA. Effect of age on marrow macrophage number and function. Aging (Milano ) 1995;7:379–384. doi: 10.1007/BF03324349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Doria G, Mancini C, Utsuyama M, Frasca D, Hirokawa K. Aging of the recipients but not of the bone marrow donors enhances autoimmunity in syngeneic radiation chimeras. Mech Ageing Dev. 1997;95:131–142. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(97)01871-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Timm JA, Thoman ML. Maturation of CD4+ lymphocytes in the aged microenvironment results in a memory-enriched population. J Immunol. 1999;162:711–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Stephan RP, Lill-Elghanian DA, Witte PL. Development of B cells in aged mice: decline in the ability of pro-B cells to respond to IL-7 but not to other growth factors. J Immunol. 1997;158:1598–1609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Mu XY, Thoman ML. Aging affects the regeneration of the CD8+ T cell compartment in bone marrow transplanted mice. Mech Ageing Dev. 2000;112:113–124. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(99)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Cheleuitte D, Mizuno S, Glowacki J. In vitro secretion of cytokines by human bone marrow: effects of age and estrogen status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2043–2051. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.6.4848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Stephan RP, Reilly CR, Witte PL. Impaired ability of bone marrow stromal cells to support B- lymphopoiesis with age. Blood. 1998;91:75–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Aydar Y, Balogh P, Tew JG, Szakal AK. Follicular dendritic cells in aging, a “bottle-neck” in the humoral immune response. Ageing Res Rev. 2004;3:15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Aydar Y, Balogh P, Tew JG, Szakal AK. Altered regulation of Fc gamma RII on aged follicular dendritic cells correlates with immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif signaling in B cells and reduced germinal center formation. J Immunol. 2003;171:5975–5987. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Lung TL, Saurwein-Teissl M, Parson W, Schonitzer D, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Unimpaired dendritic cells can be derived from monocytes in old age and can mobilize residual function in senescent T cells. Vaccine. 2000;18:1606–1612. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00494-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Chen LC, Pace JL, Russell SW, Morrison DC. Altered regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in macrophages from senescent mice. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4288–4298. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4288-4298.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Burgess W, Liu Q, Zhou J, Tang Q, Ozawa A, VanHoy R, Arkins S, Dantzer R, Kelley KW. The immune-endocrine loop during aging: role of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1999;6:56–68. doi: 10.1159/000026365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Lavrovsky Y, Chatterjee B, Clark RA, Roy AK. Role of redox-regulated transcription factors in inflammation, aging and age-related diseases. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35:521–532. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Poynter ME, Daynes RA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha activation modulates cellular redox status, represses nuclear factor-kappaB signaling, and reduces inflammatory cytokine production in aging. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32833–32841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Spencer NF, Poynter ME, Im SY, Daynes RA. Constitutive activation of NF-kappa B in an animal model of aging. Int Immunol. 1997;9:1581–1588. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.10.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Mosley RL. Aging, immunity and neuroendocrine hormones. Adv Neuroimmunol. 1996;6:419–432. doi: 10.1016/s0960-5428(97)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]