Abstract

Activation of the β-adrenergic (β-AR) signaling pathway enhances cardiac function through protein kinase A (PKA)–mediated phosphorylation of target proteins involved in the process of excitation–contraction (EC) coupling. Experimental studies of the effects of β-AR stimulation on EC coupling have yielded complex results, including increased, decreased, or unchanged EC coupling gain. In this study, we extend a previously developed model of the canine ventricular myocyte describing local control of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) calcium (Ca2+) release to include the effects of β-AR stimulation. Incorporation of phosphorylation-dependent effects on model membrane currents and Ca2+-cycling proteins yields changes of action potential (AP) and Ca2+ transients in agreement with those measured experimentally in response to the nonspecific β-AR agonist isoproterenol (ISO). The model reproduces experimentally observed alterations in EC coupling gain in response to β-AR agonists and predicts the specific roles of L-type Ca2+ channel (LCC) and SR Ca2+ release channel phosphorylation in altering the amplitude and shape of the EC coupling gain function. The model also indicates that factors that promote mode 2 gating of LCCs, such as β-AR stimulation or activation of the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), may increase the probability of occurrence of early after-depolarizations (EADs), due to the random, long-duration opening of LCC gating in mode 2.

Keywords: calcium channels, beta-adrenergic signaling, phosphorylation, excitation-contraction coupling

INTRODUCTION

Activation of the β-adrenergic (β-AR) signaling pathway enhances cardiac function during stress or exercise through protein kinase A (PKA)–mediated phosphorylation of target proteins that are directly involved in the process of excitation–contraction (EC) coupling.1 Targets include L-type calcium (Ca2+) channels (LCCs), the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) membrane protein phospholamban (PLB), and ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ release channels (RyRs). A PKA-mediated increase in L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) boosts the trigger signal for Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) and increases overall cellular Ca2+ content. Phosphorylation of PLB relieves its inhibitory regulation of the SR Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA2a pump), thereby enhancing SR Ca2+ uptake, increasing SR Ca2+ content, and accelerating the rate of decline of the cytosolic Ca2+ transient (for review, see Bers2). The functional role of PKA-mediated phosphorylation of RyR remains controversial, with measurements of either increased3 or decreased4 open probability, and no significant effect of RyR phosphorylation on resting SR Ca2+ leak following PLB knockout.5

Experimental studies of the effects of β-AR stimulation on EC gain have yielded complex results, including increased,6 decreased,7 or unchanged8 EC coupling gain. In this study, we use data on β-AR responses of ventricular myocytes to develop models of phosphorylated LCCs and RyRs. To do this, we modify a recently developed computational model of the canine ventricular myocyte, which describes stochastic gating of individual LCCs and RyRs and their interactions within the diadic space. A model describing responses to β-AR agonists is formulated by incorporating the effects of PKA-mediated phosphorylation on LCCs, PLB, RyRs, Ikr,and Iks. The resulting model is then used to assess the effects of specific β-AR–induced changes in LCC and RyR channel gating on properties of EC coupling as well as the integrative behavior of the ventricular myocyte.

METHODOLOGY

Numerical Methods

Simulations are performed using a canine ventricular myocyte model incorporating stochastic gating of LCCs and RyRs.9 This model has been shown to capture fundamental properties of local control of CICR, such as high gain, graded release, and stable release termination. The model incorporates (1) sarcolemmal ion currents of the Winslow et al. canine ventricular cell model;10 (2) continuous-time Markov chain models of the rapidly activating delayed rectifier potassium current Ikr,11 the Ca2+-independent transient outward K current Ito1,12 and the Ca2+-dependent transient outward chloride (Cl−) current Ito2; (3) a continuous-time Markov chain model of ICaL which Ca2+-mediated inactivation occurs via the mechanism of mode-switching;13,14 (4) an RyR channel model adapted from that of Keizer and Smith;14,15 and (5) locally controlled CICR from junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum (JSR) via inclusion of LCCs, RyRs, chloride channels, local JSR, and diadic subspace compartments within Ca2+ release units (CaRUs).

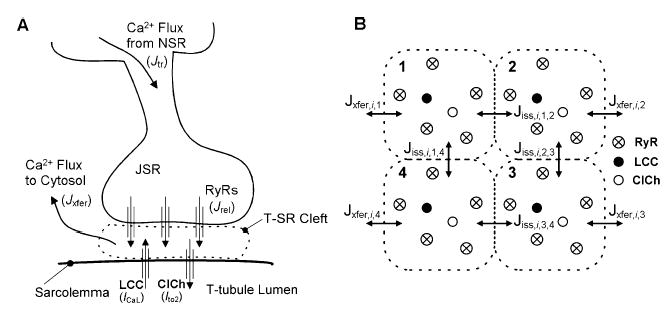

Figure 1A shows a schematic of the CaRU. The CaRU model is intended to mimic the properties of Ca2+ sparks in the T-tubule/SR (T-SR) junction.16 Figure 1B shows a cross-section of the model T-SR cleft, which is divided into four individual diadic subspace compartments arranged on a 2 × 2 grid. Each subspace (SS) compartment contains a single LCC and 5 RyRs in its JSR and sarcolemmal membranes, respectively. All 20 RyRs in the CaRU communicate with a single local JSR volume. The 5:1 RyR to LCC stoichiometry is consistent with recent estimates indicating that a single LCC typically triggers the opening of 4–6 RyRs.17 Each subspace is treated as a single compartment in which Ca2+ concentration is uniform; however, Ca2+ may diffuse passively to neighboring subspaces within the same CaRU. The division of the CaRU into four subunits allows for the possibility that an LCC may trigger Ca2+ release in adjacent subspaces (i.e., RyR recruitment) under conditions where unitary LCC currents are large. The existence of communication among adjacent subspace volumes is supported by the findings that Ca2+ release sites can be coherent over distances larger than that occupied by a single release site,18 and that the mean amplitude of Ca2+ spikes (local SR Ca2+ release events that consist of one or a few Ca2+ sparks19) exhibits a bell-shaped voltage dependence, indicating synchronization of multiple Ca2+ release events within a T-SR junction.7 The choice of four subunits allows for semiquantitative description of diadic Ca2+ diffusion while retaining minimal model complexity.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the CaRU. (A) Trigger Ca2+ influx through LCCs enters the T-SR cleft (diadic space). The rise in local Ca2+ level promotes the opening of RyRs and chloride channels (ClChs). Local Ca2+ diffuses passively from the cleft into the cytosol, and JSR Ca2+ is refilled via passive diffusion from the NSR. (B) The T-SR cleft (shown in cross-section) is composed of four diadic subspace volumes arranged on a 2 × 2 grid, each containing 1 LCC, 1 ClCh, and 5 RyRs. Ca2+ in any subspace may diffuse to a neighboring subspace (Jiss) or to the cytosol (Jxfer). Jiss,i,j,l represents Ca2+ flux from the jth subspace to the lth subspace within the ith CaRU. Similarly Jxfer,i,j represents Ca2+ flux from the jth subspace to the cytosol from the ith CaRU.

ICaL is a function of the total number of channels (NLCC), single-channel current magnitude (i), open probability (po), and the fraction of channels that are available for activation (factive), where ICaL = NLCC × factive × i × po.20 Single LCC parameters are based on experimental constraints on both i and po, as described previously.9 The product NLCC × factive is chosen such that the amplitude of the whole-cell current agrees with that measured experimentally in canine myocytes.21 This approach yields a value of 50,000 for NLCC × factive, consistent with experimental estimates of active LCC density22,23 and corresponding to 12,500 active CaRUs.

One of the bases for local control of SR Ca2+ release is the structural separation of T-SR clefts at the ends of sarcomeres (i.e., RyR clusters are physically separated).24 Each CaRU is therefore simulated independently in accord with this observation. Upon activation of RyRs, subspace Ca2+ concentration increases. This Ca2+ will diffuse freely to either adjacent subspace compartments (Jiss) or into the cytosol (Jxfer) as determined by local concentration gradients. The local JSR compartment is refilled via passive diffusion of Ca2+ from the network SR (NSR) compartment (Jtr).

The algorithm for solving the stochastic ordinary differential equations defining the model has been described previously.9 Briefly, transition rates for each channel are determined by their gating schemes and their dependence on local Ca2+ level. Gating of each channel within a CaRU is simulated by choosing channel occupancy time as an exponentially distributed random variable with parameter determined by the sum of voltage- and/or Ca2+ -dependent transition rates from the current state. Stochastic simulation of CaRU dynamics is used to determine net Ca2+ flux into and out of each local subspace. The summation of all Ca2+ fluxes crossing the CaRU boundaries are taken as inputs to the global model, which is defined by a system of coupled ordinary differential equations. The dynamic equations defining the global model are solved using the Merson modified Runge-Kutta 4th-order adaptive time step algorithm,25 which has been modified to embed the stochastic CaRU simulations within each time step.

This model provides the ability to investigate the ways in which LCC, RyR, and subspace properties influence CICR and the integrative behavior of the myocyte. However, this ability is achieved at a high computational cost. Three approaches are therefore used to accelerate the computations. First, the pseudorandom number generator used in the original model9 was changed from the Numerical Recipes function ran226 to the Mersenne Twister algorithm,27 resulting in a substantially longer period (219937−1) and reduced computation time (roughly by a factor of 4). Second, we have developed an algorithm for the dynamic allocation of model CaRUs so that a large number of CaRUs are used prior to, during, and shortly after the action potential, and a smaller number of CaRUs are used during diastole. Third, simulation of the stochastic dynamics of the independent functional units may be performed in parallel, resulting in near linear speedup as the number of processors is increased. These modifications enable us to simulate up to one second of model activity in one minute of simulation time when running on 6 IBM Power4 processors each configured with 4 Gbytes of memory.

Model of β-AR Input

β-AR agonists increase LCC availability (factive).28–30 In guinea pig and human ventricular myocytes, baseline values of factive are relatively low and are increased by 2- to 2.5-fold in response to β-AR stimulation (or in heart failure, in which there may be hyperphosphorylation of LCCs).20,28,29,31 These data differ from those in rat, which show considerably higher baseline availability and a smaller change in factive in response to β-AR stimulation.30 We have therefore elected to develop a “baseline” model of β-AR action using data primarily from guinea pig, canine, and human ventricular myocytes. β-AR–induced phosphorylation of LCCs is modeled by including populations of both active (phosphorylated) and inactive (unphosphorylated) LCCs. Model parameters are adjusted based on analyses of slow cycling between active and inactive modes in the presence of the β-AR agonist isoproterenol (ISO), indicating that at 1 μM concentration, ~25% of LCCs are available under control conditions, and that this increases to ~60% in the presence of ISO.28 The fraction of active CaRUs is set equal to the fraction of active LCCs (i.e., active CaRUs contain active LCCs).

Increased PKA-mediated phosphorylation of LCCs in response to β-AR agonists has also been shown to shift the distribution of LCCs into high-activity gating modes.28–30 Mode 0a gating is characterized by infrequent brief openings, whereas mode 1 is characterized by bursts of brief openings, and mode 2 by long-lasting openings. In this study it has been assumed that mode 0a openings do not significantly contribute to whole-cell ICaL (see Herzig et al.28) and are therefore lumped into the inactive population of LCCs. Mode 1 gating of the LCC corresponds to the LCC model control parameter set. Mode 2 gating is defined as a modification of mode 1 parameters based on the data of Yue et al.,29 in which mean LCC open time is increased from 0.5 ms to 5 ms. This is implemented by reducing the exit rate from the mode normal open state (g)14 by a factor of 10. Under control conditions, all active LCCs are assumed to operate in mode 1, while in response to 1 μM ISO 15% of the active population of LCCs are assumed to operate in mode 2 and the remaining 85% are assumed to operate in mode 1.29

β-AR stimulation has also been shown to enhance SERCA2a function,32 reduce inactivation/rectification of IKr,33 and increase amplitude of Iks.34 Functional increase in SERCA2a availability is modeled by simultaneous scaling of both the forward and reverse maximum pump rates Vmaxf and Vmaxr35 by a factor of 3.3. Reduction in the degree of steady state inactivation of IKr is modeled by reducing rates entering the inactivation state (αi and αi3) by a factor of four, and increasing the rates exiting the inactivation state (βi and Ψ) by this same factor.11 Functional upregulation of IKs is modeled by scaling maximal conductance by a factor of two.

RESULTS

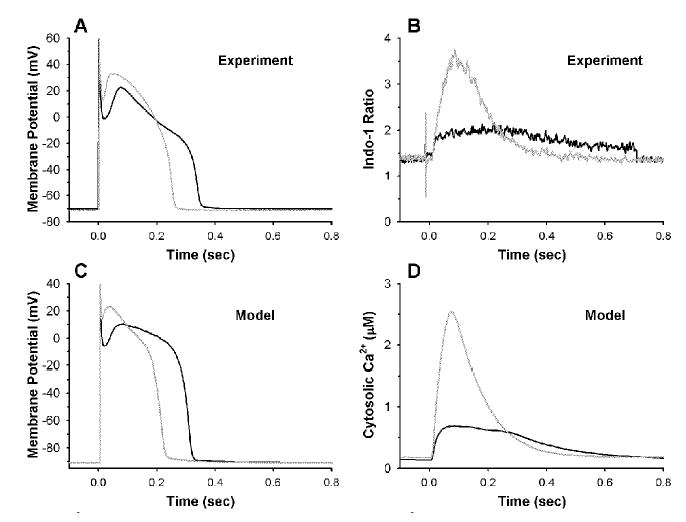

Figure 2 shows the ability of the baseline β-AR model to reproduce experimental data on responses to 1 μM ISO. Simultaneous measurements of action potentials (APs) and Ca2+ transients are shown in Figures 2A and B, respectively, for control (black lines) and following application of ISO (gray lines). Action potential duration (APD) in response to ISO (Fig. 2A) is shortened by ~30%, the plateau potential becomes ~10–15 mV more depolarized, and phase 1 notch depth and duration are reduced. In addition, ISO produces ~3-fold increase in Ca2+-transient amplitude and speeds the relaxation rate of the Ca2+ transient ~3-fold (Fig. 2B). The AP generated by the baseline β-AR model (Fig. 2C) exhibits shortening of duration, depolarization of AP plateau, and reduction in phase 1 notch depth and duration similar to that seen experimentally (Fig. 2A). Peak amplitude of the model Ca2+ transient (Fig. 2D) is increased ~3-fold, and the rate of decay of the transient is increased (shortening its overall duration), as seen in experiments (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Model and experimental APs and Ca2+ transients for control (black) and β-AR stimulation (gray). (A) Representative APs measured in isolated canine myocytes in control bath (black) and ISO (gray). (B) Indo-1 fluorescence ratio measured simultaneously with the APs in Fig. 1A (B. O’Rourke, unpublished data). (C) Control (black) and β-AR stimulated (gray) model APs. (D) Model cytosolic Ca2+ concentration (μM) corresponding to the APs in Fig. 1C.

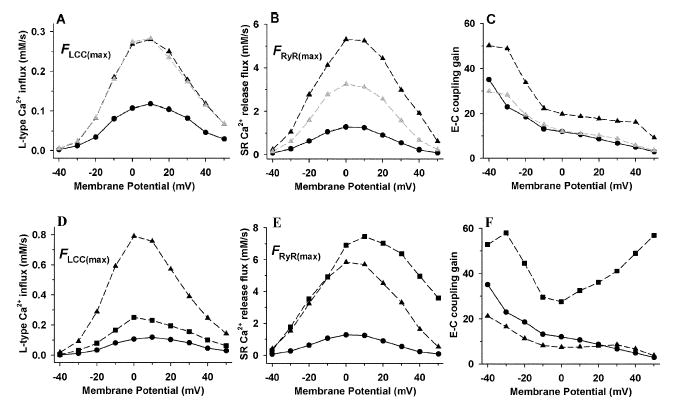

EC coupling properties of the baseline β-AR versus the control model are shown in Figures 3A–C. Peak LCC Ca2+ influx FLCC(max) (Fig. 3A) and Peak RyR Ca2+ release flux FRyR(max) (Fig. 3B) are shown in response to a 200-ms voltage clamp step. EC coupling gain, defined as the ratio of peak SR release flux to peak LCC Ca2+ influx FRyR(max)/FLCC(max),36 is shown in Figure 3C. Under control conditions (black circles), the voltage dependence of FLCC(max) is bell shaped and peaks at +10 mV with amplitude of 0.118 mM s−1 (3.85 pA pF−1). The control voltage dependence of FRyR(max) is also bell shaped and peaks at 0 mV with amplitude of 1.28 mM s−1 corresponding to a gain of ~12. Since peak FRyR(max) occurs at a more negative potential than peak FLCC(max)9, the control gain function is monotonically decreasing with increasing voltage.7,36 β-AR stimulation (black triangles) increases FLCC(max) at all potentials by ~2.5-fold, consistent with the associated increase in model LCC availability. FRyR(max) shows an ~5-fold increase due to the combination of increased LCC influx and augmented SR Ca2+ load. The enhanced SR Ca2+ release yields increased gain at all potentials. In order to dissect the roles of altered LCC gating versus SR Ca2+ load on EC coupling gain, the simulations were repeated using the baseline β-AR model, but with initial SR Ca2+ concentrations set to control levels (gray triangles). Under these conditions, FLCC(max) is nearly identical to that for highly loaded SR, but FRyR(max) is reduced considerably, resulting in a gain that is similar to control at all potentials. The increase in EC coupling gain arising from β-AR stimulation may therefore be attributed to the increase in SR Ca2+ load associated with the effects of enhanced SERCA2a function in this model, rather than to the changes in LCC gating properties. In addition, peak ICaL is essentially unaffected by SR Ca2+ load (Fig. 3A) since Ca2+ -mediated inactivation of an LCC can occur only after sufficient Ca2+ has entered the local microdomain, and therefore primarily influences the late component of ICaL.

FIGURE 3.

Panels A–C show effects of β-AR stimulation using the baseline model on macroscopic peak LCC Ca2+ influx FLCC(max) (A), peak RyR Ca2+ release flux FRyR(max) (B), and EC-coupling gain defined as FRyR(max)/FLCC(max) (C) Responses include control (black circles), the baseline β-stimulated model (black triangles), and the β-stimulated model with initial control conditions for SR Ca2+ load (gray triangles). Panels D–F show effects of LCC open frequency and RyR Ca2+ sensitivity associated with β-AR stimulation on macroscopic peak LCC Ca2+ influx (D), peak RyR Ca2+ release flux (E), and EC coupling gain (F). Responses include control (circles), increased LCC open frequency (4 × f, triangles), and increased RyR Ca2+ sensitivity (10 × k12, squares).

The baseline β-AR model described thus far assumes that β-AR stimulation redistributes active LCCs among modes 1 and 2 without any change to the kinetics that define each mode.28,29 In rat ventricular myocytes, Chen-Izu et al.30 have found that increased open probability of LCCs in response to β-AR stimulation is associated with ~3- to 4-fold increase in mode 1 open frequency (i.e., number of open events per sweep). Figures 3D–F show model behavior when mode 1 open frequency is increased 4-fold within the baseline β-AR model (triangles) versus control (circles). Figures 3D–F show model FLCC(max), FRyR(max) and EC coupling gain in response to the same protocol described for Figures 3A–C. Increased mode 1 open frequency leads to dramatic increases in both LCC Ca2+ influx and SR Ca2+ release flux during β-AR stimulation compared to control. In addition, FLCC(max) peaks at 0 mV compared to 10 mV in control. A β-AR-induced negative shift in the peak of the L-type Ca2+ current I-V relation is often observed experimentally.7,37 While FRyR(max) is increased as a result of increased trigger Ca2+ influx, the gain of EC coupling is decreased by up to 50% at potentials more negative than 10 mV, due to local saturation of the trigger Ca2+ signal. A similar reduction in EC coupling gain has been observed by Song et al.7 in response to norepinephrine in rat ventricular myocytes.

The data of Marx et al.3 suggest that defective regulation of RyR in failing myocytes is associated with PKA-mediated hyperphosphorylation of the channel, leading to increased sensitivity to Ca2+-dependent activation as a result of the dissociation of FKBP12.6, a protein that is normally bound to the RyR. Consequences of RyR hyperphosphorylation may include systolic hypersensitivity to trigger Ca2+ and/or diastolic leak of Ca2+, contributing to SR depletion.38 We investigate the possible consequences of PKA-induced increases of RyR Ca2+ sensitivity by scaling the initial rate of opening (k12) in the RyR model.15 Results on EC coupling gain are shown in Figures 3D–F (squares). FLCC(max) (Fig. 3D) displays an increase in magnitude similar to that when RyR Ca2+ sensitivity is unaltered (Fig. 3A), indicating that enhanced sensitivity of RyR to Ca2+ has little effect on the amplitude of FLCC(max). However, FRyR(max) (Fig. 3E) is increased at all potentials compared to control, displaying a shift in its peak toward more positive potentials. The dramatic increase in SR Ca2+ release flux at the more positive potentials is indicative of the loss of tight control of CICR. This phenomenon is evident in the EC coupling gain curve (Fig. 3F, squares), where gain is increased at all potentials, yielding a U-shaped function. A similar gain function has been observed by Viatchenko-Karpinski and Györke6 in response to β-AR stimulation by ISO in rat myocytes, where both an increase in the ability of individual sparks to ignite adjacent release sites and an increase in the efficiency of ICaL to trigger Ca2+ release (i.e., increased fidelity) were reported. These observations are consistent with an increased Ca2+ sensitivity of RyR activation.

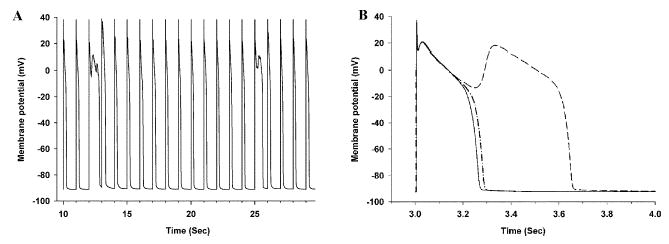

Figure 4A shows long-term response of the baseline β-AR model to 1-Hz pacing. Membrane potential (ordinate; mV) is plotted as a function of time (abscissa; Sec). Two early after-depolarizations (EADs) occur during the 30 s of simulated activity. A series of simulations with a duration of 100 s was performed. The fraction of LCCs gating in mode 2 was varied in these simulations, taking on values of 0, 7.5%, and 15%. The number of EADs occurring during each of these simulations was 0, 2, and 5, respectively. These data therefore suggest that EADs do not occur when the fraction of channels gating in mode 2 is zero, and that the rate of EAD occurrence increases as the fraction of LCCs gating in mode 2 is increased. Figure 4B shows results of three simulations in which the fraction of LCCs gating in mode 2 was set to 15%. Model parameters, initial conditions on state variables governed by ordinary differential equations, and initial states of each channel were identical in each of the three runs. The only difference between runs is that the pseudorandom number generator seeds used to produce channel open times were initialized to different values prior to each run. Thus, each simulation produces channel state transitions that are distinct realizations of the same stochastic process. It can be seen that one of the three runs produced an EAD, whereas two did not. These data indicate that in the baseline β-AR model (a) EADs are not generated when the fraction of LCCs gating in mode 2 is zero, (b) the rate of occurrence of EADs increases as the fraction of LCCs gating in mode 2 increases, and (c) when the fraction of LCCs gating in mode 2 is greater than zero, EADs occur randomly as a consequence of the underlying nature of stochastic channel gating.

FIGURE 4.

(A) Membrane potential (ordinate; mV) as a function of time (abscissa; Sec) for the baseline β-AR model in response to 1 Hz pacing. (B) Membrane potential (ordinate; mV) as a function of time (abscissa; Sec) for three AP simulations in which model parameters, initial conditions on state variables governed by ordinary differential equations, and initial states of each channel are identical; however, the pseudorandom number generator seeds used to produce channel open times are initialized to different values prior to each simulation.

SUMMARY

The local control of the canine ventricular myocyte model of Greenstein and Winslow9 was modified to study the role of phosphorylation-induced changes in LCC- and RyR-gating properties, and LCC availability in response to β-AR stimulation. The model is based on experimental data describing ventricular myocyte responses to the β-AR agonist ISO at a concentration of 1 μM, and includes (a) increased availability of LCCs, (b) a shift of LCC gating from mode 1 to mode 2, (c) increased SERCA2a function, (d) reduced inactivation/rectification of IKr, and (e) increased amplitude of IKs.

Model APs and Ca2+ transients were compared to those measured experimentally. Results indicate that model APs and Ca2+ transients (Fig. 2) are in close agreement with experimental data. Specifically, model APs exhibit a raised plateau potential and shortened duration, and model Ca2+ transients exhibit increased peak amplitude and accelerated relaxation. The rise in AP plateau is in response to increased ICaL, whereas the shortening of the AP is attributed to the increased functional magnitude of IKr. Increases in Ca2+ transient amplitude and rate of cytosolic Ca2+ removal are due to enhanced SERCA2a function.

Experimental studies have demonstrated an increase,6 decrease,7 or no change8 of EC coupling gain in response to β-AR stimulation. Simulations performed using the local control myocyte model indicate that characteristic changes in the voltage-dependent EC coupling gain function may be attributed to phosphorylation-induced alterations of specific target proteins. The baseline model of β-AR stimulation displayed no change in gain when SR Ca2+ load was unaltered (Fig. 3C), consistent with the findings of Ginsburg and Bers.8 Increasing LCC open frequency produced a decrease in gain similar to that measured by Song et al.7 Increasing RyR Ca2+ sensitivity produced an increase in gain similar in shape to that measured by Viatchenko-Karpinski and Györke6 (Fig. 3F). These model results suggest that differences in the effects of β-AR stimulation on experimental estimates of the EC coupling gain function reported in the literature may result from differences in the primary downstream targets of β-AR signaling in each of these studies.

The data of Figure 4 indicate that in the baseline β-AR, the rate of occurrence of EADs increases as the fraction of LCC gating in mode 2 increases; and when the fraction of LCC gating in mode 2 is greater than zero, EADs occur randomly as a consequence of the underlying nature of stochastic, long-duration openings of LCC gating in mode 2. β-AR agonists such as ISO are known to induce EADs, even at concentrations producing APD shortening.39,40 In addition, the serine/threonine kinase Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), through phosphorylation of as-yet-unidentified cell membrane proteins, is known to increase the fraction of LCC gating in mode 2 relative to other modes41 and to produce EADs.42 A CaMKII inhibitory peptide AC3-I, which prevents mode 2 gating of LCCs43 eliminates these EADs without affecting APD. Our own simulations (not shown here) indicate that in the normal canine ventricular myocyte model,9 an increase of the fraction of LCC gating in mode 2 is sufficient to induce EADs. These data, therefore, suggest the hypothesis that, in general, factors that promote mode 2 gating of LCCs may be linked with the generation of EADs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 HL60133 and P50 HL52307, the Whitaker Foundation, the Falk Medical Trust, and the IBM Corporation.

References

- 1.Xiao RP, et al. Recent advances in cardiac β2-adrenergic signal transduction. Circ Res. 1999;85:1092–1100. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.11.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marx SO, et al. PKA phosphorylation dissociates FKBP12.6 from the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor): defective regulation in failing hearts. Cell. 2000;101:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80847-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valdivia HH, et al. Rapid adaptation of cardiac ryanodine receptors: modulation by Mg2+ and phosphorylation. Science. 1995;267:1997–2000. doi: 10.1126/science.7701323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, et al. Protein kinase A phosphorylation of the ryanodine receptor does not affect calcium sparks in mouse ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2002;90:309–316. doi: 10.1161/hh0302.105660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Gyorke S. Modulation of the Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release cascade by β-adrenergic stimulation in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol (Lond) 2001;533:837–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song LS, et al. Beta-adrenergic stimulation synchronizes intracellular Ca2+ release during excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2001;88:794–801. doi: 10.1161/hh0801.090461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ginsburg KS, Bers DM. Isoproterenol does not increase the intrinsic gain of cardiac excitation-conctration coupling (ECC) Biophys J. 2001;80:590a. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenstein JL, Winslow RL. An integrative model of the cardiac ventricular myocyte incorporating local control of Ca2+ release. Biophys J. 2002;83:2918–2945. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75301-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winslow RL, et al. Mechanisms of altered excitation-contraction coupling in canine tachycardia-induced heart failure. II Model studies Circ Res. 1999;84:571–586. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazhari R, et al. Molecular interactions between two long-qt syndrome gene products, herg and kcne2, rationalized by in vitro and in silico analysis. Circ Res. 2001;89:33–38. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.093633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenstein JL, et al. Role of the calcium-independent transient outward current Ito1 in shaping action potential morphology and duration. Circ Res. 2000;87:1026–1033. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.11.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imredy JP, Yue DT. Mechanism of Ca2+-sensitive inactivation of L-type Ca2+ channels. Neuron. 1994;12:1301–1318. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jafri MS, Rice & JJ, Winslow RL. Cardiac Ca2+ dynamics: the roles of ryanodine receptor adaptation and sarcoplasmic reticulum load [ published erratum appears in 1998. Biophys. J. 74: 3313] Biophys J. 1998;74:1149–1168. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77832-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keizer J, Smith GD. Spark-to-wave transition: saltatory transmission of calcium waves in cardiac myocytes. Biophys Chem. 1998;72:87–100. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(98)00125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng H, Lederer WJ, Cannell MB. Calcium sparks: elementary events underlying excitation-contraction coupling in heart muscle. Science. 1993;262:740–744. doi: 10.1126/science.8235594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang SQ, et al. Ca2+ signalling between single L-type Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors in heart cells. Nature. 2001;410:592–596. doi: 10.1038/35069083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker I, Zang & WJ, Wier WG. Ca2+ sparks involving multiple Ca2+ release sites along Z-lines in rat heart cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1996;497:31–38. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song L, et al. Direct measurement of SR release flux by tracking ‘Ca2+ spikes’ in rat cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 1998;512:677–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.677bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Handrock R, et al. Single-channel properties of L-type calcium channels from failing human ventricle. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;37:445–455. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hobai IA, O’Rourke B. Decreased sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content is responsible for defective excitation-contraction coupling in canine heart failure. Circulation. 2001;103:1577–1584. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.11.1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose WC, et al. Macroscopic and unitary properties of physiological ion flux through L- type Ca2+ channels in guinea-pig heart cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1992;456:267–284. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonald TF, et al. Voltage-dependent properties of macroscopic and elementary calcium channel currents in guniea pig ventricular myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 1986;406:437–448. doi: 10.1007/BF00583365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franzini-Armstrong C, Protasi F F, Ramesh V. Shape, size, and distribution of Ca2+ release units and couplons in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Biophys J. 1999;77:1528–1539. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77000-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.K ubicek, M. & M. Marek 1983. Computational Methods In Bifurcation Theory and Dissipative Structures. Springer-Verlag. New York.

- 26.P ress, W.H., S.A. Teukolsky, W.T. Vetterling & B.P. Flannery 1992. Numerical Recipes. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

- 27.Matsumoto M, Nishimura T. Mersenne twister: a 623-dimensionally equidistributed uniform pseudorandom number generator. ACMTMCS. 1998;8:3–30. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herzig S, et al. Mechanisms of β-adrenergic stimulation of cardiac Ca2+ channels revealed by discrete-time Markov analysis of slow gating. Biophys J. 1993;65:1599–1612. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81199-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yue DT, Herzig & S, Marban E. Beta-adrenergic stimulation of calcium channels occurs by potentiation of high-activity gating modes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:753–757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen-Izu Y, et al. Gi-dependent localization of beta 2-adrenergic receptor signaling to L-type Ca2+channels. Biophys J. 2000;79:2547–2556. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76495-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroder F, et al. Increased availability and open probability of single L-type calcium channels from failing compared with nonfailing human ventricle. Circulation. 1998;98:969–976. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simmerman HK, Jones LR. Phospholamban: protein structure, mechanism of action, and role in cardiac function. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:921–947. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.4.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heath BM, Terrar DA. Protein kinase C enhances the rapidly activating delayed rectifier potassium current, IKr, through a reduction in C-type inactivation in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. J Physiol (Lond) 2000;522:391–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kathofer S, et al. Functional Coupling of Human beta 3-Adrenoreceptors to the KvLQTl/MinK Potassium Channel. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26743–26747. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003331200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shannon TR, Ginsburg & KS, Bers DM. Reverse mode of the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium pump and load-dependent cytosolic calcium decline in voltage-clamped cardiac ventricular myocytes. Biophys J. 2000;78:322–333. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76595-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wier WG, et al. Local control of excitation-contraction coupling in rat heart cells. J Physiol. 1994;474:463–471. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kääb S, et al. Ionic mechanism of action potential prolongation in ventricular myocytes from dogs with pacing-induced heart failure. Circ Res. 1996;78:262–273. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marks AR. Ryanodine receptors/calcium release channels in heart failure and sudden cardiac death. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:615–624. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Priori SG, Corr PB. Mechanisms underlying early and delayed afterdepolarizations induced by catecholamines. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:1796–1805. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.6.H1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quadbeck J, Reiter M. Adrenoceptors in cardiac ventricular muscle and changes in duration of action potential caused by noradrenaline and isoprenaline. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1975;288:403–414. doi: 10.1007/BF00501285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dzhura I, et al. Cytoskeletal disrupting agents prevent calmodulin kinase, IQ domain and voltage-dependent facilitation of L-type Ca2+ channels. J Physiol. 2002;545:399–406. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.021881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 42.Wu Y, et al. Calmodulin kinase II and arrhythmias in a mouse model of cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 2002;106:1288–1293. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027583.73268.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dzhura I, et al. Calmodulin kinase determines calcium-dependent facilitation of L-type calcium channels. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:173–177. doi: 10.1038/35004052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]