Abstract

The hypocretin neurons have been implicated in regulating sleep-wake states as they are lost in patients with the sleep disorder narcolepsy. Hypocretin (HCRT) neurons are located only in the perifornical region of the posterior hypothalamus and heavily innervate pontine brainstem neurons, such as the locus coeruleus (LC), which have traditionally been implicated in promoting arousal. It is not known how the hypocretin innervation of the pons regulates sleep-wake states as pontine lesions have never been shown to increase sleep. It is likely that in previous studies specific neurons were not lesioned. Therefore, in this study, we applied saporin-based neurotoxins to the dorsolateral pons and monitored sleep in rats. Anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase-saporin killed the LC neurons but sleep was affected only during a two hour light-dark transition period. Application of hypocretin2-saporin killed fewer LC neurons relative to other adjacent neurons. This occurred because the LC neurons possess the hypocretin receptor 1 but the ligand hypocretin 2 binds to this receptor with less affinity relative to the hypocretin receptor2. The hypocretin2-saporin lesioned rats compared to controls had increased sleep during the dark period and displayed increased limb movements during REM sleep. None of the lesioned rats had sleep onset REM sleep periods or cataplexy. We conclude that the hypocretin innervation to the pons functions to awaken the animal when the lights turn off (via its innervation of the LC), sustains arousal and represses sleep during the rest of the night (via a wider innervation of other pontine neurons), and modulates muscle tone.

Keywords: locus coeruleus, narcolepsy, NREMS, orexin, rat, REMS

Abbreviations: Anti-DBH-sap, anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase-saporin; DBH, dopamine-β-hydroxylase; EEG, electroencephalogram; EMG, electromyogram; HCRT, hypocretin; HCRT2-sap, hypocretin2-saporin; HCRT R1 or 2, hypocretin receptor 1 or 2; LC, locus coeruleus; LDT, laterodorsal tegmental nuclei; NREMS, nonrapid eye movement sleep; PFS, pyrogen-free saline solution; PPT, pedunculopontine tegmental nuclei; REMS, rapid eye movement sleep

Introduction

The sleep disorder narcolepsy is now considered a neurodegenerative disease as there is a massive loss of neurons containing the neuropeptide hypocretin (HCRT) in brains of patients with this disease (Peyron et al., 2000; Thannickal et al., 2000). Consistent with such a neuronal degeneration, MRI scans reveal grey matter loss in the posterior hypothalamus where the HCRT neurons are localized (Draganski et al., 2002). Mice (Chemelli et al., 1999; Hara et al., 2001) and rats (Gerashchenko et al., 2001a; Gerashchenko et al., 2003) with either loss of HCRT or of the HCRT neurons exhibit symptoms of narcolepsy. Canines with narcolepsy possess a mutation in the hypocretin receptor 2 (Lin et al., 1999) and mice with a deletion of this receptor (Willie et al., 2003) show also symptoms of narcolepsy.

As the HCRT-containing neurons project to virtually the entire brain (De Lecea et al., 1998; Peyron et al., 1998), it is important to identify which HCRT projection regulates specific aspects of sleep-wake behaviour. The murine (Willie et al., 2003) and canine (Lin et al., 1999) models of narcolepsy are unsuited for this purpose as the defect is present in the entire animal. To elucidate the role of specific HCRT innervations in specific sleep-wake behaviours it is necessary to make targeted lesions of HCRT receptor bearing neurons. To facilitate this goal economically and across diverse species, we have developed a neurotoxin by conjugating the ribosomal inactivating protein saporin to the ligand hypocretin-2 (HCRT2-sap) to lesion HCRT receptor bearing neurons (Gerashchenko et al., 2001a). It was not feasible to conjugate HCRT1 to saporin because of the presence of disulphide bonds in HCRT1. Previously, we determined that HCRT2-sap binds specifically to the HCRT receptor but not to substance-P receptor bearing cells (Gerashchenko et al., 2001 a), and that it kills HCRT receptor bearing neurons in the tuberomammillary nucleus and lateral hypothalamus (Gerashchenko et al., 2001a).

When HCRT2-sap is applied to the lateral hypothalamus, the lesioned rats display narcoleptic symptoms (Gerashchenko et al., 2001a; Gerashchenko et al., 2003); a finding consistent with data from HCRT null mice (Chemelli et al., 1999; Hara et al., 2001). When HCRT receptor containing neurons in the medial septum are lesioned (Gerashchenko et al., 2001b), only hippocampal theta activity is abolished but there is no narcoleptic symptoms observed indicating that indeed specific HCRT innervations serve specific functions.

A strong candidate region where HCRT could exert a powerful influence is the pontine brainstem, a brain region that has traditionally been regarded as being important for regulating sleep-wake states on the basis of transection, lesion and pharmacological studies (Siegel, 1990). In the dorsolateral region of the pons the electrophysiological activity of the noradrenergic locus coeruleus and putative cholinergic neurons is tightly related to sleep-wake states (Siegel, 1990). HCRT neurons project very heavily to this area (Peyron et al., 1998) and both hypocretin receptors 1 and 2 (HCRT R1 or R2) are present here, although the LC contains primarily HCRT R1 (Greco & Shiromani, 2001). HCRT excites LC neurons in vitro (Horvath et al., 1999) and in vivo increases waking and decreases rapid eye movement sleep (REMS) (Hagan et al., 1999; Bourgin et al., 2000). If HCRT promotes waking and represses REMS as a result of activating HCRT receptor neurons in the dorsolateral pons, then loss of these target neurons should decrease waking and increase REMS. In the present study, we test this hypothesis using HCRT2-sap to lesion specific dorsolateral pontine HCRT receptors bearing neurons. To separate these neurons from the LC, we also utilize antidopamine-β-hydroxylase-saporin (anti-DBH-sap) to lesion only the LC neurons.

Materials and methods

Experiment 1. Lesion of the dorsolateral pontine noradrenergic neurons with antidopamine-β-hydroxylase-saporin (anti-DHB-sap)

Subjects and surgical procedure

Fourteen adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (400–620 g, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington MA) were deeply anaesthetized with a cocktail of 0.75 mg/kg acepromazine, 2.5 mg/kg xylazine and 22 mg/kg ketamine (i.m.) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus. Using a glass micropipette (20 μm tip) each animal was given a bilateral microinjection of pyrogen free saline solution (PFS)(n = 6, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO), 192 IgG-sap (n = 3, 1 μg/μL, Chemicon International, Temecula CA, #MAB390) or anti-DHB-sap (n = 5, 1 μg/μL, Chemicon International, #MAB394) at the following coordinate: A, −0.8; L, ±1.5; V, +2.0 [coordinates based on interaural line; Paxinos & Watson (1986)]. This target was 0.5 mm lateral and ventral to the LC and this adjustment was made so as not to damage the neurons controlling micturition located in Barrington’s nucleus. Moreover based on our past experience with drug delivery, we anticipated that the toxin would spread along the shaft of the pipette and kill neurons dorsal to the injection site in addition to killing neurons at the pipette tip. 192 IgG-saporin was selected as an additional control because like anti-DBH-sap it is a conjugate of a monoclonal antibody and saporin. However 192-IgG-saporin binds only to cells containing the low affinity neuronal growth factor p75 receptor, present solely on forebrain cholinergic and cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Therefore, 192-IgG-saporin was expected to spare noradrenergic LC neurons. The PFS and saporin-conjugated toxins were delivered in a volume of 0.3 μL at a rate of 0.1 μL/5 min using a pressure injector (Picospritzer General Valve, Fairfield NJ). At the same time sleep recording electrodes were implanted as described elsewhere (Gerashchenko et al., 2003). Briefly two screws (Plastic Ones Inc., Roanoke VA) were inserted 2mm on either side of the midline suture and 3 mm anterior to bregma (frontal cortex) the other two screws were located 2 mm on either side of the midline and 6 mm posterior to bregma (occipital cortex). The electroencephalogram (EEG) was recorded from two contralateral (frontal left vs. occipital right and frontal right vs. occipital left) screw electrodes while the electromyogram (EMG) signal was recorded from two multistranded wires inserted bilaterally into the nuchal muscles. All experimental procedures performed on live animals were approved and in full compliance with the guidelines issued by the local committee of animal care. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used.

To further confirm the efficacy of the anti-DHB-sap to kill noradrenergic-LC neurons and its fibers, two rats were given a unilateral microinjection (under deep anaesthesia) of anti-DHB-sap to the LC in the same concentration and volume as reported above. These rats were not given sleep recording electrodes but remained alive for the same time after injection as the rats implanted with sleep electrodes. Three weeks after injection of the anti-DHB-sap, rats were killed and brains processed for immunohistochemistry.

Polysomnographic recordings and sleep data analysis

Immediately after surgery, rats were housed individually and behavioural states were continuously recorded for at least 20 days. To allow animals to recover from the surgery, the first sleep recordings that were analysed were made on days 6 and 7. Additionally data from 13th, 14th, 19th and 20th postinjection days were also analysed to determine how long the changes in sleep endured. Polysomnographic recordings were made in an isolated room at 20–23 °C, with a 12-h light: 12-h dark cycle schedule (lights turned on at 07:00 h; 200 lux). Rats had water and food available ad libitum. Contralateral frontal-occipital and nuchal muscles voltages were amplified, filtered (0.3–70 Hz for EEG, 0.1–1 kHz for EMG, Neurodata Acquisition System Model 12, Grass Telefactor, West Warwick RI), digitized (sampling frequency 128 Hz, National Instruments, Austin TX) and stored in a computer using the ICELUS data acquisition software (Mark Opp, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor MI). A technician (E. Winston) blind to the treatment analysed the sleep data on a computer screen in 12 s epochs for wake, nonrapid eye movement sleep (NREMS) and REMS. Waking was identified by the presence of desynchronized EEG activity, high EMG integrated activity coupled with low delta power relative to NREMS. NREMS was characterized by high amplitude-slow wave EEG activity coupled to low EMG activity and high delta power compared to waking. REMS was distinguished by hypersynchronized theta EEG activity, low to absent EMG signal relative to NREMS and high theta-low delta power spectra. After manual scoring of 12 h-long recordings, the ICELUS software automatically produced ASCII files showing the percentage time spent in each behavioural state, bout numbers, and length of bouts of each behavioural state for each hour. Additionally, a Fast Fourier Transformation (every 2 s) was performed on the EEG to determine power in the delta band (0.5–4 Hz) during NREM sleep and theta band (6.0–9.0 Hz) during REM sleep. The EEG data from two consecutive 24-h periods were combined to generate a single value representative of each postinjection week (first, second and third).

EMG activity during waking, NREMS and REMS was analysed by averaging 12s epochs of the integrated EMG activity for each behavioural state during the two consecutive 24-h periods. This provided a single value of integrated EMG activity for each state for each postinjection week. Two-way anova along with Tukey’s test were used for statistical comparisons among groups and postinjection weeks.

Histology

After sleep recordings were completed, rats were killed with an overdose of Nembutal, perfused with 0.9% saline solution (400 mL) followed by 10% phosphate buffered formalin (400 mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO, HT50). The brains were removed, formalin-fixed overnight and then equilibrated in 30% sucrose-phosphate buffer saline at 4 °C. A sliding microtome was used to cut the brains in 30-μm-thick coronal sections. Brains sections were then cryoprotected and stored at −20 °C for subsequent histochemistry or immunohistochemistry. Brainstem tissue was processed for detection of DHB (mouse anti-DHB, 1:50 000, Chemicon International, #AB1585), NADPH-diaphorase and for a specific neuronal marker; NeuN (mouse anti-NeuN, 1:8000, Chemicon International, #MAB377). Dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH) and NADPH-diaphorase stained sections were counterstained with Neutral Red (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO, N-7005).

Tissue from rats with unilateral LC injections was processed for detection of tyrosine hydroxylase (mouse anti-TH, 1:12 000 Chemicon International, #MAB318), and NeuN. Briefly, free-floating sections were first washed several times in phosphate buffered saline, incubated for 1 h in 2% normal serum-0.25% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO), then incubated overnight at room temperature in the primary antibody. The next day sections were incubated in biotin-coupled secondary antibody for 1 h (donkey anti-mouse IgG, 1:500, Chemicon International) followed by incubation in the peroxidase-biotin-avidin complex for 1 h (Vectastain Elite ABC standard Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame CA). The 3,3′-diaminobenzidine-nickel method was used to visualize the reaction product (DAB Kit, Vector Laboratories). As a control some sections were incubated in the secondary antibody only. In the case of NADPH-diaphorase, sections were washed in Tris buffered saline, placed on 0.3% Triton X-100 Tris buffered saline for 1 h and incubated at 37 °C for 45 min in Tris buffered saline containing 1.2mm β-NADPH (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO #N-6505) and 0.12mm Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (Sigma-Aldrich, #N-6876).

Cell counts

To assess the effects of anti-DHB-sap on LC neurons, DHB-immunoreactive (ir) neurons were manually counted by a person unaware of the treatment given to each rat. Only rats that received bilateral injections as well as were sleep recorded were used in this analysis. DBH-ir neurons both in the LC proper as well as in the subcoeruleus region were counted. In each rat, neuronal counts were made from nine sections extending from A, −0.16 to −1.04mm. Total number of DBH-ir cells was determined for each section using an optical grid (500 μm2) placed on the LC. To evaluate the specificity of anti-DHB-sap, NADPH-diaphorase positive cholinergic neurons located in the laterodorsal tegmental nuclei (LDT) as well as the pedunculopontine tegmental nuclei (PPT) were counted. Total number of NADPH-diaphorase positive cells in each rat was counted from ten sections spanning from A, +1.70 to −0.30. Neurons were counted by placing a grid (1000 μm2) either upon the LDT or PPT. One-way analyses of variance coupled with Tukey’s tests were used to test for differences between groups (P < 0.050).

Experiment 2. Lesions of the dorsolateral pons with HCRT2-sap

Seventeen rats were administered with pontine injections. Under deep anaesthesia each rat was given a bilateral microinjection of PFS (n = 6), HCRT2-sap 90ng/μL (n = 6) or HCRT2-sap 60ng/μL (n = 5). The same coordinates as in experiment 1 were used. All injections were pressure-delivered using a glass micropipette in a volume of 0.3 μL at a rate of 0.1 μL/5 min. All rats were supplied with sleep recording electrodes as described in experiment 1 above. Sleep recordings began immediately after the surgery and data analysis was as in experiment 1. The analysis of the EMG integrated activity was also performed as detailed in experiment 1.

At the end of the 3 weeks of sleep recordings, rats were killed (overdose of Nembutal), and the brains removed for histology. Tissue sections (one in five series) were double labelled for DBH and NADPH-diaphorase or NeuN. Double-labelled sections were also counterstained with neutral red. Cell counts of noradrenergic and cholinergic cells were performed as described in experiment 1. Both NeuN labelled (neuronal loss) and neutral red stained sections were used to outline the lesion zones using a mirror-image drawing microscope (Nikkon Eclipse E400). Tissue containing the entire hypothalamus was processed for visualization of hypocretin-immunoreactivity (rabbit anti-OrexinA (hypocretin-1), 1:60 000, Peninsula Laboratories, San Carlos CA) to determine whether there was loss of hypocretin neurons as a result of retrograde transport of the HCRT2-sap.

Results

Experiment 1. Lesions of the dorsolateral pons with anti-DBH-sap

Anatomical findings

As shown in Fig. 1, anti-DBH-sap injected into the LC killed the DBH-ir neurons in the LC. Figure 2 summarizes the neuronal counts and when compared to PFS-injected rats, there was a significant decrease in number of DBH-ir neurons in the LC in anti-DBH-sap lesioned rats (F19 = 29.775, P < 0.001). DBH-ir neurons outside the LC, such as those located in the A7 and A5 clusters were spared. The lesion of the noradrenergic somata of the LC was also accompanied by a loss of DBH-ir fibers throughout the forebrain (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Effects of anti-DBH-sap on noradrenergic neurons in the LC. Photo A depicts a coronal section of the pons containing the LC in a rat administered with PFS. Panel D is an enlargement of the LC nucleus from the same rat shown in A. Panels B and C represent two examples of LC lesions following a unilateral (panel B) or bilateral microinjection of anti-DBH-sap in the LC. The tissue was reacted for visualization of DBH immunoreactivity and NADPH-diaphorase activity (to identify cholinergic neurons). Cells stained in black were positive for dopamine-β-hydroxylase whereas blue stained cells (evident in photos D and E and highlighted by arrows) represent NADPH-diaphorase activity. The tissue was also counterstained with neutral red (red cells). Anti-DBH-sap lesioned the noradrenergic LC neurons but not the adjacent cholinergic neurons (photo E). Scale bar in B applies to A and C and scale bar in E applies to D.

Fig. 2.

Effects of saporin-conjugated neurotoxins on number of noradrenergic LC neurons (DBH-ir+) and cholinergic (identified as NADPH+) neurons in the lateral dorsal tegmental nucleus. ***P< 0.001 vs. PFS, *P< 0.015 vs. PFS.

To further confirm that anti-DBH-sap lesioned the noradrenergic neurons the tissue was reacted for identification of tyrosine hydroxylase as well as for the neuronal marker, NeuN. As shown in Fig. 3, anti-DBH-sap lesioned noradrenergic neurons in the LC and did not simply blocked expression of catecholamines.

Fig. 3.

Effects of anti-DBH-sap on the expression of two proteins normally present in LC neurons. Photos A and B identify LC neurons labelled with tyrosine hydroxylase. Photo A identifies the LC in the side contralateral to the anti-DBH-sap injection while photo B is from the side given anti-DBH-sap in the LC. Photo C identifies NeuN labelled neurons in the LC and adjacent dorsolateral pontine tegmentum. In photo C, no NeuN labelled neurons are evident in the LC receiving anti-DBH-sap relative to the contralateral side (LC is marked by an arrow in photo C) indicating that the neurotoxin killed LC neurons rather than only inhibiting the activity of the enzyme DBH present in LC neurons.

Anti-DBH-sap injections in the LC did not lesion the cholinergic neurons adjacent to it (Fig. 1D and E). The total number of NADPH-positive (cholinergic) neurons within the LDT–PPT area was not significantly altered between anti-DBH-sap and PFS-injected rats (Fig. 2). We also did not notice a visible loss of NeuN labelled neurons in the LDT–PPT. The specificity of anti-DBH-sap to kill only DBH neurons is based on the high affinity of the antibody for its antigen DBH The specificity of anti-DBH-sap to kill noradrenergic LC neurons has been demonstrated by others (Wrenn et al., 1996; Jasmin et al., 2003) but the effect on brainstem cholinergic neurons was not examined previously.

The effects of another antibody-based saporin conjugate was tested. 192IgG-sap injections to the LC did not lesion the noradrenergic-LC neurons or the cholinergic cells in the LDT–PPT (Fig. 2).

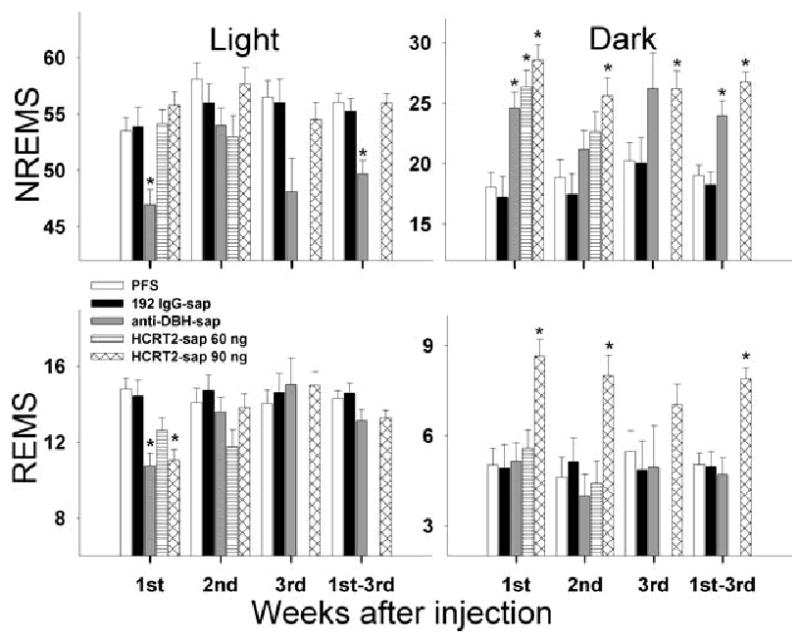

Effects on sleep after anti-DBH-sap lesions of the dorsolateral pons

Figure 4 summarizes the percentage wake, NREMS and REMS in anti-DBH-sap treated rats in two-hour blocks over a 24-h period, while Fig. 5 summarizes this data for the 12-h light and 12-h dark periods. Table 1 summarizes the sleep-wake averages over 24 h. In the first week after anti-DBH-sap injection, there was a significant (P < 0.001) reduction in NREMS (−12.17%) and REMS (−27.25%) during the light period (Figs 4 and 5) and an increase in NREMS during the lights off period (36.3% vs. PFS P < 0.05). In the second week, neither NREMS nor REMS were significantly different from controls (Figs 4 and 5). In the third week the main difference in sleep occurred during the transition period when the lights turned on or off. NREMS in anti-DBH-sap treated rats was significantly lower than control rats during the first two hours of the light period and higher during the first four hours of the dark period (Fig. 4). Thus, by the third week, the main difference that was evident was that anti-DBH-sap rats, compared to PFS-injected rats, were awake more when the lights turned on (when they should be asleep), and asleep more when the lights turned off (when they should be awake).

Fig. 4.

Effects of anti-DBH-sap lesions of the LC on percentage wake, NREMS and REMS over a 3-week period. The data are double plotted, with the dark bar representing the dark period. The primary effect at 3 weeks after anti-DBH-sap injection was during the light–dark transition period. The lesioned animals were awake more (and had less NREMS) during the two-hour period after the lights turned on, and they were awake less (and had more NREMS) when the lights turned off. Asterisks denote P < 0.05 anova. PFS n = 6, anti-DBH-sap n = 5.

Fig. 5.

Effects of saporin-conjugated neurotoxins on sleep-wake states (mean percentage ± SEM) during the 12-h light and dark periods. There was no data from HCRT2-sap 60 ng during the third week as the sleep recording electrodes became disconnected from many of the rats in this group. 1st–3rd represents the average of the 3-week period. Asterisk denotes P < 0.001 vs. PFS treated rats.

Table 1.

Percentage total sleep time (NREMS + REMS) averaged over 24 h in rats given PFS or saporin-conjugated neurotoxins

| Week postinjection | PFS | 192IgG-sap | Anti-DBH-sap | HCRT2-sap 60 ng | HCRT2-sap 90ng |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st week | 45.67 ± 1.32 | 44.95 ± 1.34 | 43.54 ± 1.26 | 49.36 ± 0.84 | 52.03 ± 1.19*** |

| 2nd week | 46.15 ± 0.78 | 46.47 ± 0.91 | 46.44 ± 1.29 | 42. 13 ± 2.64 | 52.55 ± 1.20*** |

| 3rd week | 48.12 ± 0.97 | 48.03 ± 1.36 | 47.15 ± 0.57 | - | 51.37 ± 1.03 |

| Average of 3 weeks | 46.46 ± 0.63 | 46.30 ± 0.71 | 45.06 ± 0.85 | 46.47 ± 1.35 | 51. 99 ± 0.67*** |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. After injections sleep was recorded for 3 weeks. Dorsolateral pontine lesion with HCRT2-sap increased total sleep time compared to PFS rats (***P < 0.001). Many of the rats given the low concentration of HCRT2-sap (60 ng) in the dorsolateral pons lost their sleep electrodes by the third week and as such there is no sleep data for this group.

192 IgG-sap injections within the dorsolateral pons produced no changes in total sleep during the light or dark periods compared to PFS-injected rats (Fig. 5).

Experiment 2. Lesions of the dorsolateral pons with HCRT2-sap

Anatomical findings

Previously, we determined that the HCRT receptors are present on many neurons of the pontine reticular formation (Greco & Shiromani, 2001) and that HCRT2-sap kills HCRT receptor bearing cells (Gerashchenko et al., 2001a). The neurotoxin has a preference for HCRT receptor 2 (HCRT R2) as the ligand HCRT-2 binds with higher affinity to the HCRT R2 over the HCRT receptor 1 (HCRT R1) (Sakurai et al., 1998). In the pons, the LC neurons contain HCRT R1 and few if any HCRT R2 (Greco & Shiromani, 2001; Marcus et al., 2001). Accordingly we found that HCRT2-sap did not significantly decrease the number of noradrenergic LC neurons (Figs 2 and 6A). On the other hand, many of the cholinergic neurons contain both types of receptors (Greco & Shiromani, 2001; Marcus et al., 2001), and HCRT2-sap at a concentration of 90ng/μL, destroyed 37% of the cholinergic neurons within the LDT (see Figs 2 and 6D). Cholinergic neurons in the PPT were not significantly affected by HCRT2-sap (PFS 403 ± 27 vs. HCRT2-sap 350 ± 43 P = 0.325) because the PPT neurons are dispersed over a wide area of the pontine tegmentum where the toxin did not spread (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

Effects of HCRT2-sap on noradrenergic LC and cholinergic LDT-PPT neurons. HCRT2-sap killed more cholinergic neurons relative to noradrenergic LC neurons. Photo A depicts a coronal section of the dorsolateral pons labelled to identify DBH-ir neurons in the LC. The tissue section is from a rat that received HCRT2-sap (90ng/μL) 3 weeks earlier, but the LC is still visible. Panels B and C depict NADPH positive cells in the LDT (B) as well as PPT region (C) of a rat with a PFS injection in the LC. Photos D and E are showing how after HCRT2-sap (90 ng/μL) injection there is a significant loss of LDT cholinergic neurons (D) but not of PPT cholinergic neurons (E). D and E are tissue sections taken from the same rat depicted in A. Cholinergic neurons were identified by NADPH-staining. LDT, lateral dorsal tegmental nucleus; scp, superior cerebellar peduncle; PPT, pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus.

NeuN and Nissl labelling was used to outline the boundaries of the neuronal loss produced by HCRT2-sap (Figs 7 and 8). HCRT2-sap (90ng/μL) ablated neurons within the parabrachial complex (lateral and medial), ventrolateral portion of the laterodorsal tegmental nuclei, dorsolateral portion of pontine reticular nuclei (oral), lateral portion of the dorsomedial tegmental nucleus and also within the subcoeruleus area (alpha and dorsal) (Fig. 8). Despite the significant neuronal loss with HCRT2-sap, clusters of neurons were still present within the lesion zone (Fig. 7C) perhaps because these neurons, like the LC, do not possess the HCRT R2.

Fig. 7.

Effects of HCRT2-sap on NeuN labelled neurons. Photomicrographs are from rats given PFS (panel A) or HCRT2-sap 90 ng/μL (panel B and C) aimed at the locus coeruleus (LC). HCRT2-sap produced a loss of neurons within subcoeruleus alpha (SCα), the medial parabrachial nucleus (MPB), the medial pontine reticular formation, the superior cerebellar peduncle (scp), lateral parabrachial nucleus (LPB) and laterodorsal tegmental nucleus (LDT). When adjacent sections were stained to identify noradrenergic and cholinergic neurons there was a clear loss of cholinergic neurons but not of the LC neurons (see Figs 2 and 6). Panel C is a higher magnification of the lesioned area delineated as a rectangle in B and there are visible neurons within the lesion zone, indicating that even within the lesion area some neurons are spared, perhaps because they did not possess the appropriate HCRT receptor. DMTg, dorsomedial tegmental area; DTg, dorsal tegmental nucleus.

Fig. 8.

Extent of the lesion in the dorsolateral pontine tegmentum produced by the two concentrations of HCRT2-sap. Substantial neuronal loss (shown by loss of NeuN-ir) as well as gliosis response (shown by neutral red) were used to outline lesion areas one month after the injection. Figures depict the rostral (left column), central (middle column) and caudal extents (right column) of the lesion in every rat that received HCRT2-sap (90 ng, n = 6; 60 ng, n = 5). A number located at top left of every series identifies individual rats. Numbers at the bottom of every coronal section indicate the anterior–posterior planes from the interaural line and correspond to drawings from the Paxinos & Watson’s rat brain atlas, (Paxinos & Watson, 1986).

A lower concentration HCRT2-sap (60 ng/μL) produced a smaller lesion zone confined primarily to the subcoeruleus area (Fig. 8). Neither cholinergic nor noradrenergic cells were significantly affected at this concentration (Fig. 2).

Saporin-based toxins can be taken up at terminals and transported retrogradely killing neurons distal to the injection site (Ohtake et al., 1997; Blessing et al., 1998; Llewellyn-Smith et al., 1999). To assess whether HCRT2-sap could have been taken up by presynaptic HCRT receptors on HCRT axons and killed HCRT-containing neurons, lateral hypothalamic sections were labelled to visualize HCRT-ir neurons. Compared to PFS-injected rats, no visible reduction in the number of HCRT-containing neurons was observed, suggesting that sufficient HCRT2-sap might not have been taken up by the presynaptic receptors and transported retrogradely to destroy the cell body. The tuberomammillary nucleus, which contains HCRT R2, was also examined and no visible loss of neurons was found. Neuronal loss in this nucleus does not lead to significant change in sleep (Gerashchenko et al., 200la) and more than 70% of the HCRT-containing neurons need to be destroyed before there is hypersomnia. We would have noticed such an obvious loss of HCRT neurons.

Effects on sleep

Figure 9 summarizes the percentage wake, NREMS and REMS in 2 h blocks over the 24-h period. Figure 5 summarizes the data in 12-h periods. HCRT2-sap (90 ng) produced a significant hypersomnia during the dark period, especially over the last two-thirds of the dark period (Fig. 9). In the first week postinjection HCRT2-sap lesions increased nocturnal total sleep time by 61.4% compared to PFS-injected rats (P < 0.001). By the third week after injection, nocturnal sleep percentage was still 29.1% higher than controls (P < 0.001). The increase in total sleep time during the dark period was due to an increase in both NREMS and REMS (Figs 9 and 5). By the third week, night-time NREMS was still 30% above control levels (P = 0.025 vs. PFS). When averaged over the 3-week period, HCRT2-sap increased nocturnal REMS by 56.5% compared to controls (P < 0.001)(Fig. 5).

Fig. 9.

Effects of HCRT2-sap (90ng/μL) on percentage wake, NREMS and REM sleep. The data (means ± SEM) are double-plotted with the abscissa indicating time in 2-h blocks. Open and closed horizontal bars indicate the light and dark periods. *P < 0.05 anova with Tukey’s test. PFS n = 6, HCRT2-sap n = 6.

The nocturnal increase in sleep induced by HCRT2-sap lesion was due to a significant increase in the number of bouts of NREMS (+35.6%, P < 0.05 vs. PFS) and REMS (+61.7%, P < 0.02). The length of the NREMS and REMS bouts was not changed, but there was a significant decrease in the length of the wake bouts at night (P = 0.041).

Rats administered with lower concentration of HCRT2-sap (60 ng/μL) in the dorsolateral pons had increased night-time amounts of NREMS during the first week postinjection (31.7% vs. PFS) (Fig. 5). The increase in nocturnal NREMS amounts also produced an increase in total sleep time during the first week (38.5% vs. PFS, P = 0.004). During the subsequent weeks, sleep levels were not significantly different from controls. Thus, the lower concentration of HCRT2-sap (60 ng/μL) only produced short-term changes in sleep.

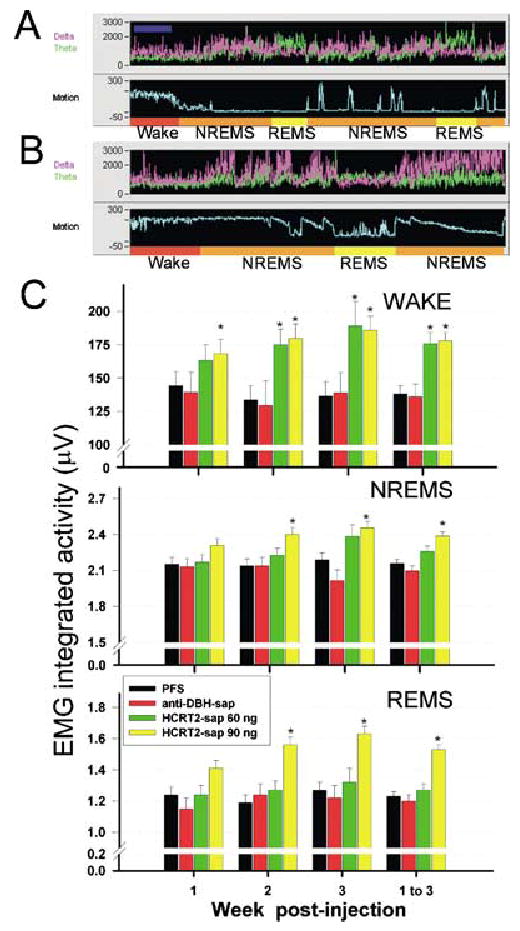

Effects of HCRT2-sap on muscle tone

We observed that a few days after injection and consistent with the time course of neuronal death (Gerashchenko et al., 2001a), rats administered with the high concentration of HCRT2-sap (90 ng/μL) began to display increased limb movements during REMS (Fig. 10A vs. Fig. 10B). To provide empirical evidence we analysed the integrated EMG from all rats and found that the rats given HCRT2-sap (90 ng/μL) had a progressive increase in muscle tone during REMS bouts compared to controls (+29% by the third week, Fig. 10C). The progressive and significant increase in muscle tone was also evident during waking (+36% by the third week) and to a lesser degree during NREMS (12% by the third week, Fig. 10C). Rats given the low concentration of HCRT2-sap in the dorsolateral pons also had increased muscle tone during waking (+39%) but not during NREMS or REMS (Fig. 10C). Rats given PFS had the normal decline in EMG integrated activity from waking to NREMS to REMS (Fig. 10A, P < 0.05) indicating that EMG tone declined in sleep and was lowest in REMS (significant difference compared to NREMS, P < 0.05). PFS and anti-DBH-sap treated rats had a uniform level of muscle tone during REMS, NREMS and waking over the 3-week recording period attesting to the sensitivity of the integrated EMG to measure muscle tone (Fig. 10C).

Fig. 10.

Effects of HCRT2-sap on integrated muscle tone during REM sleep. Panels A and B depict 2 min segments of a sleep-wake recording in rats given PFS (panel A) or HCRT2-sap (panel B) to the dorsolateral pons. Each panel (A and B) consists of a recording of power of the EEG in the delta (0.3–4 Hz, magenta trace) and theta bands (4–12 Hz, green trace), and integrated activity of the nuchal muscles (Motion, light blue). The sleep-wake state determination, based on the relationship of the EEG (not shown here), power and EMG activity, is indicated at the bottom of each panel. Rats given HCRT2-sap displayed increased muscle tone during REM sleep (panel B). It was not unusual to witness rats displaying tread behaviour while in REM sleep, a phenomenon akin to REM sleep behaviour disorder. Panel C depicts the effects of HCRT2-sap or anti-DBH-sap on integrated muscle tone during specific behavioural states over the 3-week recording period. EMG activity was recorded from flexible wires inserted in the nuchal muscles, and the integrated EMG activity (integrated every second and averaged over 12 s) is represented in the ordinate scale. EMG data are means ± SEM. PFS n = 6, anti-DBH-sap n = 5, HCRT2-sap 60 ng/μL n = 5, HCRT2-sap 90 ng/μL n = 6. *P< 0.05 vs. PFS. Dark blue bar located on the left corner at the top panel indicates 2 min.

Sleep onset REMS episodes were never seen following HCRT2-sap, or anti-DBH-sap lesions. Unambiguous incidences of cataplexy were also not clearly evident.

Discussion

The pontine brainstem has played a central role in theories of sleep-wake generation since the pioneering studies by Bremer (1935) and Moruzzi & Magoun, (1949). After the discovery of REMS, Jouvet (Jouvet, 1962) used the transection method to determine that this sleep state was also generated from this region. Since then numerous studies have investigated this region to identify the critical neurons responsible for generating wake, NREMS and REMS. The key neurons that have emerged include the serotonergic dorsal raphe, the noradrenergic LC, the cholinergic pontine neurons in the LDT and PPT nuclei, pontine GABA interneurons and glutamatergic neurons. Electrophysiology studies have found that the noradrenergic LC and serotonergic dorsal raphe neurons are most active during waking, less active during NREMS, and they stop firing during REMS (Hobson et al., 1975; McGinty & Harper, 1976). As these neurons decrease firing, putative cholinergic/cholinoceptive cells in the LDT and PPT nuclei and in the medial pontine reticular formation increase discharge rates (Shiromani et al., 1987; el Mansari et al., 1989; Steriade et al., 1990). It is hypothesized that the reciprocal discharge of these neuronal populations is regulated by input from local GABA and glutamate neurons and the coordinated interactions between these neurons regulates the three behavioural states (summarized in Siegel, 1990).

Over the years a number of studies have lesioned various areas of the pons utilizing electrolytic, chemical or excitotoxins to identify the relative roles of specific pontine nuclei in sleep-wake states (Carli & Zanchetti, 1965; Jones et al., 1977; Jones, 1979; Sastre et al., 1981; Webster & Jones, 1988). However, the neuronal phenotypes implicated in sleep-wake states overlap each other, making it difficult to lesion specific neurotransmitter containing neurons. In the present paper, more selective immunotoxins were used to target specific neuronal populations.

Locus coeruleus lesions and sleep

The lesions produced by the anti-DBH-sap were specific to the LC noradrenergic neurons and adjacent cholinergic neurons were not destroyed. The LC receives an especially heavy innervation of hypocretin fibers (Peyron et al., 1998) and HCRT excites LC neurons as well (Hagan et al., 1999; Horvath et al., 1999). We used anti-DBH-sap to test whether the HCRT-LC activation is key to maintaining waking and inhibiting REMS as hypothesized. Lesions of the LC with anti-DBH-sap did not increase total sleep time or increase REM sleep, a finding consistent with other previous studies where the LC was lesioned (Roussel et al., 1976; Jones et al., 1977; Webster & Jones, 1988; Gonzalez et al., 1998) or where DBH was genetically removed (Hunsley & Palmiter, 2003). In the present study, the primary long-term consequence of LC lesions was increased sleep only during the dark transition period and increased waking for a few hours after the lights turned on. This is consistent with recent data that the LC receives time-of-day information from the circadian oscillator, the suprachiasmatic nucleus, via the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (Aston-Jones et al., 2001). Another region of the brain that may receive time-of-day information is the histamine neurons in the tuberomammillary nucleus because mice deficient in histamine (histidine decarboxylase null mice) also display sleep abnormalities only during the lights on and off transition periods (Parmentier et al., 2002). This suggests that both the noradrenergic LC and the histamine neurons, which to date have been implicated in arousal because these neurons are most active during waking relative to sleep, may modulate waking levels at certain circadian times, perhaps via input from the lateral hypothalamus.

HCRT2-sap lesions of the dorsolateral pons and sleep

HCRT2-sap, which kills HCRT receptor bearing neurons (Gerashchenko et al., 2001a) increased both NREMS and REMS over the long-term period when it was applied to the dorsolateral pons. As previous lesion studies never found increased total sleep time and/or increased REM sleep with pontine lesions, we conclude that the HCRT2-sap is destroying specific HCRT receptor bearing neurons that stimulate waking and inhibit REMS. The chemical identity of these neurons is not known, but some might be sensitive to GABA as microinjection of bicuculline, a GABAA antagonist, in the same region as in the present study increases REMS while the agonist, muscimol, increases waking (Camacho-Arroyo et al., 1991; Xi et al., 1999; Pollock & Mistlberger, 2003). These neurons could also be cholinoceptive, as carbachol stimulation in this region triggers REMS in cats (Shiromani et al., 1992) and rats (Gnadt & Pegram, 1986; Shiromani & Fishbein, 1986; Bourgin et al., 1995).

Hypocretin fibers innervate the entire pons and there is a heavy concentration of both HCRTR1 and HCRTR2 on neurons in this region (Greco & Shiromani, 2001). HCRT release onto dorsolateral pontine neurons during waking could serve to increase activity of other wake-active neurons in the pons. Our results suggest that the HCRT signal to the dorsolateral pons helps to sustain waking over the second half of the night, as hypersomnia was evident in the last two-thirds of the dark wake-active period. This idea is consistent with cerebrospinal fluid measurements in rats (Fujiki et al., 2001; Yoshida et al., 2001) and monkeys (Zeitzer et al., 2003) which show peak HCRT levels during the end of the wake-active period. HCRT2-sap induced destruction of the dorsolateral pontine neurons could have decreased the generalized activation of the pontine wake-active neurons, allowing forebrain sleep-active neuronal activity to predominate, thereby increasing NREMS. Because HCRT is also released during REMS in the pons (Kiyashchenko et al., 2002) activation of the dorsolateral pontine neurons would be inhibitory to REMS, and their lesion with HCRT2-sap would increase REMS. Destruction of these neurons by HCRT2-sap serves the same purpose as bicuculline in that when these neurons are prevented from being active, REMS on neurons are disinhibited and REMS is triggered.

The extent of the lesion with the HCRT2-sap are quite similar to the excitotoxic and electrolytic lesions in previous studies, both in size and location in the pons (Carli & Zanchetti, 1965; Jones et al., 1977; Jones, 1979; Sastre et al., 1981; Webster & Jones, 1988). In previous lesion studies, the primary effect on sleep was increased waking and/or a decrease in REM sleep, and this may have occurred because of destruction of both the REMS-on and REMS-off neurons. Indeed, with excitotoxic lesions of the LDT-PPT mesopontine cholinergic neurons there was a significant decline in REM sleep but not of waking (Webster & Jones, 1988). With such lesions one would have expected a decline in waking and an increase in sleep as these neurons are hypothesized to regulate waking. In the present study, the specificity of the HCRT2-sap may have limited damage to the HCRT receptor bearing neurons and that is why this is the first study to find an increase in NREMS and REMS after dorsolateral pontine lesions.

This is similar to the lateral and posterior hypothalamus where many investigators (Ranson, 1939; Nauta, 1946; Swett & Hobson, 1968; McGinty, 1969; Danguir & Nicolaidis, 1980; Shoham & Teitelbaum, 1982; Sallanon et al., 1988; Denoyer et al., 1991; Jurkowlaniec et al., 1994) made lesions in an attempt to follow-up on the discovery made by von Economo (1930) that lesions of the posterior hypothalamus resulted in hypersomnia. However, the electrolytic and excitotoxic lesions of the posterior hypothalamus typically increased waking and decreased sleep. As a result, this portion of the brain was ignored in models of sleep-wake regulation until the key discovery of hypocretin and its linkage with narcolepsy. We utilized HCRT2-sap to lesion lateral hypothalamic neurons and found narcolepsy in rats (Gerashchenko et al., 2001a Gerashchenko et al., 2003). In that study, as in the present study, the appropriate behavioural response, i.e. increased sleep, was obtained only when the appropriate toxin was used to destroy neurons.

Unfortunately, there is no discrete target site in the pons that is key to sleep regulation, but rather the HCRT-innervation is diffuse and spread over a wide area of the dorsolateral pons. The pontine region ventral to the LC has been considered to be important in regulating REMS (Sakai et al., 2001). However, our results suggest that small HCRT2-sap lesions of this region do not increase sleep. Rather, a loss of neurons over a wide area of the dorsolateral pons produced the nocturnal hypersomnia. This is consistent with electrophysiological and anatomical data that there is extensive overlap between neuronal phenotypes in this region.

HCRT2-sap and REM sleep behaviour disorder

The HCRT2-sap (90 ng/μL) lesioned rats had increased muscle tone with the rats displaying extensive limb movements during REMS. Anti-DBH-sap lesioned rats did not display such behaviour. Previously, electrolytic (Hendricks et al., 1982b) and more recently excitotoxic lesions (Sanford et al., 1994) of the dorsolateral pons were found to produce animals with increased muscle tone during REMS. In fact, some cats with small electrolytic lesions of the dorsolateral pons may walk while in REMS (Hendricks et al., 1982a). A similar disorder called REMS behaviour disorder is present in humans (Schenck et al., 1993), although a specific lesion in the dorsolateral pons has not been found. Interestingly, HCRT2-sap (90 ng/μL) lesioned rats also had increased muscle tone during NREMS and waking. The lower concentration of HCRT2-sap (60 ng/μL) had increased muscle tone only during waking. This is consistent with findings that there is a strong correlation between volume of total lesion within the dorsolateral pons and higher EMG amplitude during REMS (Webster & Jones, 1988).

The increased muscle tone during NREMS and REMS is consistent with findings from human narcoleptics where increased muscle tone is present during NREMS and REMS (Schenck et al., 1993). Periodic leg movements (PLM) during NREMS are frequently part of the narcoleptic symptomatology as well (Chakravorty & Rye, 2003). Narcoleptic dogs, which carry a mutation of the HCRT R2, exhibit motor abnormalities similar to PLM (Okura et al., 2001). Mice with a deletion of the HCRT R2 also have occasionally increased phasic activity during NREMS attacks (Willie et al., 2003). Interestingly, Schenck et al. 2003 report that patients with REM sleep behaviour have increased NREMS. In the present paper, we found increased NREMS in rats with increased EMG tone, which is consistent with the findings in patients with REMS behaviour disorder.

Investigators typically do not measure muscle tone during waking, presumably because of possible contamination due to movement artifacts. In our study, it is unlikely that such contamination could have accounted for the increased muscle tone in the HCRT2-sap treated rats as these rats were awake less (and asleep more) compared to the saline controls. Wake-related movement artifact would also be present in saline and anti-DBH-sap rats, but there was no change in muscle tone in these rats over the 3-week experimental period. The increased muscle tone in the HCRT2-sap (90 ng/μL) lesioned rats suggests that the HCRT innervation of the dorsolateral pons might serve to coordinate muscle tone such that when this innervation is lost there is a release of muscle tone. The participation of GABA neurons in the release of ‘oneiric’ behaviour is suggested by the finding that injection of bicuculline to this region produces the emergence of locomotor activity during REMS (Pollock & Mistlberger, 2003).

From this study we conclude that the HCRT innervation of the dorsolateral pons serves an important function in that the input to the LC awakens the animal at the light–dark transition while innervation of other non-LC neurons in the dorsolateral pons sustains waking and inhibits sleep during the last two-thirds of the active period as well as modulates muscle tone during REMS.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jill Winston for providing excellent technical assistance and Elizabeth Winston for analysing the sleep data. Supported by NIH grants NS30140, AG09975, AG15853, MH55772, and Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- Aston-Jones G, Chen S, Zhu Y, Oshinsky ML. A neural circuit for circadian regulation of arousal. Nature Neurosci. 2001;4:732–738. doi: 10.1038/89522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blessing WW, Lappi DA, Wiley RG. Destruction of locus coeruleus neuronal perikarya after injection of anti-dopamine-B-hydroxylase immunotoxin into the olfactory bulb of the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1998;243:85–88. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgin P, Escourrou P, Gaultier C, Adrien J. Induction of rapid eye movement sleep by carbachol infusion into the pontine reticular formation in the rat. Neuroreport. 1995;6:532–536. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199502000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgin P, Huitron-Resendiz S, Spier AD, Fabre V, Morte B, Criado JR, Sutcliffe JG, Henriksen SJ, De Lecea L. Hypocretin-1 modulates rapid eye movement sleep through activation of locus coeruleus neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7760–7765. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07760.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer F. Isolated brain and physiology of sleep. CR Soc Biol. 1935;118:1235–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Arroyo I, Alvarado R, Manjarrez J, Tapia R. Microinjections of muscimol and bicuculline into the pontine reticular formation modify the sleep-waking cycle in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1991;129:95–97. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90728-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carli G, Zanchetti A. A study of pontine lesions suppressing deep sleep in the cat. Arch Ital Biol. 1965;103:751–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty S, Rye D. Narcolepsy in the older adult: epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Drugs Aging. 2003;20:361–376. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200320050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemelli RM, Willie JT, Sinton CM, Elmquist JK, Scammell T, Lee C, Richardson JA, Williams SC, Xiong Y, Kisanuki Y, Fitch TE, Nakazato M, Hammer RE, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell. 1999;98:437–151. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danguir J, Nicolaidis S. Cortical activity and sleep in the rat lateral hypothalamic syndrome. Brain Res. 1980;185:305–321. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS, Frankel WN, van den Pol AN, Bloom FE, Gautvik KM, Sutcliffe JG. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denoyer M, Sallanon M, Buda C, Kitahama K, Jouvet M. Neurotoxic lesion of the mesencephalic reticular formation and/or the posterior hypothalamus does not alter waking in the cat. Brain Res. 1991;539:287–303. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91633-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draganski B, Geisler P, Hajak G, Schuierer G, Bogdahn U, Winkler J, May A. Hypothalamic gray matter changes in narcoleptic patients. Nature Med. 2002;8:1186–1188. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Economo C. Sleep as a problem of localization. J Nervous Mental Dis. 1930;71:249–259. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki N, Yoshida Y, Ripley B, Honda K, Mignot E, Nishino S. Changes in CSF hypocretin-1 (orexin A) levels in rats across 24 hours and in response to food deprivation. Neuroreport. 2001;12:993–997. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200104170-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerashchenko D, Blanco-Centurion C, Greco MA, Shiromani PJ. Effects of lateral hypothalamic lesion with the neurotoxin hypocretin-2-saporin on sleep in Long–Evans rats. Neuroscience. 2003;116:223–235. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00575-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerashchenko D, Kohls MD, Greco M, Waleh NS, Salin-Pascual R, Kilduff TS, Lappi DA, Shiromani PJ. Hypocretin-2-saporin lesions of the lateral hypothalamus produce narcoleptic-like sleep behavior in the rat. J Neurosci. 2001a;21:7273–7283. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07273.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerashchenko D, Salin-Pascual R, Shiromani PJ. Effects of hypocretin-saporin injections into the medial septum on sleep and hippocampal theta. Brain Res. 2001b;913:106–115. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02792-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnadt JW, Pegram GV. Cholinergic brainstem mechanisms of REM sleep in the rat. Brain Res. 1986;384:29–41. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez MM, Debilly G, Valatx JL. Noradrenaline neurotoxin DSP-4 effects on sleep and brain temperature in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1998;248:93–96. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco MA, Shiromani PJ. Hypocretin receptor protein and mRNA expression in the dorsolateral pons of rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;88:176–182. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan JJ, Leslie RA, Patel S, Evans ML, Wattam TA, Holmes S, Benham CD, Taylor SG, Routledge C, Hemmati P, Munton RP, Ashmeade TE, Shah AS, Hatcher JP, Hatcher PD, Jones DN, Smith MI, Piper DC, Hunter AJ, Porter RA, Upton N. Orexin A activates locus coeruleus cell firing and increases arousal in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10911–10916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara J, Beuckmann CT, Nambu T, Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Sugiyama F, Yagami K, Goto K, Yanagisawa M, Sakurai T. Genetic ablation of orexin neurons in mice results in narcolepsy, hypophagia, and obesity. Neuron. 2001;30:345–354. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks JC, Morrison AR, Mann GL. Different behaviors during paradoxical sleep without atonia depend on pontine lesion site. Brain Res. 1982a;239:81–105. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90835-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks JC, Morrison AR, Mann GL. Different behaviors during paradoxical sleep without atonia depend on pontine lesion site. Brain Res. 1982b;239:81–105. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90835-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson JA, McCarley RW, Wyzinski PW. Sleep cycle oscillation: reciprocal discharge by two brainstem neuronal groups. Science. 1975;189:55–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1094539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath TL, Peyron C, Diano S, Ivanov A, Aston-Jones G, Kilduff TS, van den Pol AN. Hypocretin (orexin) activation and synaptic innervation of the locus coeruleus noradrenergic system. J Comp Neurol. 1999;415:145–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsley MS, Palmiter RD. Norepinephrine-deficient mice exhibit normal sleep-wake states but have shorter sleep latency after mild stress and low doses of amphetamine. Sleep. 2003;26:521–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasmin L, Boudah A, Ohara PT. Long-term effects of decreased noradrenergic central nervous system innervation on pain behavior and opioid antinociception. J Comp Neurol. 2003;460:38–55. doi: 10.1002/cne.10633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BE. Elimination of paradoxical sleep by lesions of the pontine gigantocellular tegmental field in the cat. Neurosci Lett. 1979;13:285–293. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(79)91508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BE, Harper ST, Halaris AE. Effects of locus coeruleus lesions upon cerebral monoamine content, sleep-wakefulness states and the response to amphetamine in the cat. Brain Res. 1977;124:473–196. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90948-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouvet M. Recherches sur les structures nerveuses et les mechanismes responsables des differentes phases du sommeil physiologique. Arch Ital Biol. 1962;100:125–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkowlaniec E, Trojniar W, Tokarski J. Daily pattern of EEG activity in rats with lateral hypothalamic lesions. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1994;45:399–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyashchenko LI, Mileykovskiy BY, Maidment N, Lam HA, Wu MF, John J, Peever J, Siegel JM. Release of hypocretin (orexin) during waking and sleep states. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5282–5286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05282.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Faraco J, Li R, Kadotani H, Rogers W, Lin X, Qiu X, de Jong PJ, Nishino S, Mignot E. The sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 gene. Cell. 1999;98:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Martin CL, Arnolda LF, Minson JB. Retrogradely transported CTB-saporin kills sympathetic preganglionic neurons. Neuroreport. 1999;10:307–312. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199902050-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el Mansari M, Sakai K, Jouvet M. Unitary characteristics of presumptive cholinergic tegmental neurons during the sleep-waking cycle in freely moving cats. Exp Brain Res. 1989;76:519–529. doi: 10.1007/BF00248908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus JN, Aschkenasi CJ, Lee CE, Chemelli RM, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M, Elmquist JK. Differential expression of orexin receptors 1 and 2 in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435:6–25. doi: 10.1002/cne.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty DJ. Somnolence, recovery and hyposomnia following ventromedial diencephalic lesions in the rat. Electroencephalog Clin Neurophysiol. 1969;26:70–79. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(69)90035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty DJ, Harper RM. Dorsal raphe neurons: depression of firing during sleep in cats. Brain Res. 1976;101:569–575. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90480-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moruzzi G, Magoun HW. Brain stem reticular formation and activation of the EEG. Electroenceph Clin Neurophysiol. 1949;1:455–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauta JH. Hypothalamic regulation of sleep in rats. An experimental study. J Neurophysiol. 1946;9:285–316. doi: 10.1152/jn.1946.9.4.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtake T, Heckers S, Wiley RG, Lappi DA, Mesulam MM, Geula C. Retrograde degeneration and colchicine protection of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons following hippocampal injections of an immunotoxin against the P75 nerve growth factor receptor. Neuroscience. 1997;78:123–133. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00520-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okura M, Fujiki N, Ripley B, Takahashi S, Amitai N, Mignot E, Nishino S. Narcoleptic canines display periodic leg movements during sleep. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;55:243–244. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2001.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier R, Ohtsu H, Djebbara-Hannas Z, Valatx JL, Watanabe T, Lin JS. Anatomical, physiological, and pharmacological characteristics of histidine decarboxylase knock-out mice: evidence for the role of brain histamine in behavioral and sleep-wake control. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7695–7711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07695.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos, G. & Watson, C. (1986) The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press, New York.

- Peyron C, Faraco J, Rogers W, Ripley B, Overeem S, Charnay Y, Nevsimalova S, Aldrich M, Reynolds D, Albin R, Li R, Hungs M, Pedrazzoli M, Padigaru M, Kucherlapati M, Fan J, Maki R, Lammers GJ, Bouras C, Kucherlapati R, Nishino S, Mignot E. A mutation in a case of early onset narcolepsy and a generalized absence of hypocretin peptides in human narcoleptic brains. Nature Med. 2000;6:991–997. doi: 10.1038/79690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Tighe OK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, Kilduff TS. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock MS, Mistlberger RE. Rapid eye movement sleep induction by microinjection of the GABA-A antagonist bicuculline into the dorsal subcoeruleus area of the rat. Brain Res. 2003;962:68–77. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03956-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranson SW. Somnolence caused by hypothalamic lesions in the monkey. Arch Neurol Psychiat. 1939;41:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Roussel B, Pujol JF, Jouvet M. Effects of lesions in the pontine tegmentum on the sleep stages in the rat. Arch Ital Biol. 1976;114:188–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai K, Crochet S, Onoe H. Pontine structures and mechanisms involved in the generation of paradoxical (REM) sleep. Arch Ital Biol. 2001;139:93–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, Arch JR, Buckingham RE, Haynes AC, Carr SA, Annan RS, McNulty DE, Liu WS, Terrett JA, Elshourbagy NA, Bergsma DJ, Yanagisawa M. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:573–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallanon M, Sakai K, Buda C, Puymartin M, Jouvet M. Increase of paradoxical sleep induced by microinjections of ibotenic acid into the ventrolateral part of the posterior hypothalamus in the cat. Arch Ital Biol. 1988;126:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford LD, Morrison AR, Mann GL, Harris JS, Yoo L, Ross RJ. Sleep patterning and behaviour in cats with pontine lesions creating REM without atonia. J Sleep Res. 1994;3:233–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1994.tb00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre JP, Sakai K, Jouvet M. Are the gigantocellular tegmental field neurons responsible for paradoxical sleep? Brain Res. 1981;229:147–161. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90752-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenck CH, Callies AL, Mahowald MW. Increased percentage of slow wave sleep in REM sleep behavior disorder (RED): a reanalysis of previously published data from a controlled study of RED reported in SLEEP. Sleep. 2003;26:1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenck CH, Hurwitz TD, Mahowald MW. Symposium: Normal and abnormal REM sleep regulation: REM sleep behaviour disorder: an update on a series of 96 patients and a review of the world literature. J Sleep Res. 1993;2:224–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1993.tb00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiromani PJ, Armstrong DM, Bruce G, Hersh LB, Groves PM, Gillin JC. Relation of pontine choline acetyltransferase immunoreactive neurons with cells which increase discharge during REM sleep. Brain Res Bull. 1987;18:447–455. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(87)90019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiromani PJ, Fishbein W. Continuous pontine cholinergic micro-infusion via mini-pump induces sustained alterations in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;25:1253–1261. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiromani PJ, Kilduff TS, Bloom FE, McCarley RW. Cholinergically induced REM sleep triggers Fos-like immunoreactivity in dorsolateral pontine regions associated with REM sleep. Brain Res. 1992;580:351–357. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90968-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoham S, Teitelbaum P. Subcortical waking and sleep during lateral hypothalamic ‘somnolence’ in rats. Physiol Behav. 1982;28:323–333. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(82)90082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JM. Mechanisms of sleep control. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1990;7:49–65. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199001000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Datta S, Pare D, Oakson G, Curro Dossi RC. Neuronal activities in brain-stem cholinergic nuclei related to tonic activation processes in thalamocortical systems. J Neurosci. 1990;10:2541–2559. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-08-02541.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swett CP, Hobson A. The effects of posterior hypothalamic lesions on behavioral and electrographic manifestations of sleep and waking in cats. Arch Ital Biol. 1968;106:283–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thannickal TC, Moore RY, Nienhuis R, Ramanathan L, Gulyani S, Aldrich M, Cornford M, Siegel JM. Reduced number of hypocretin neurons in human narcolepsy. Neuron. 2000;27:469–474. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00058-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster HH, Jones BE. Neurotoxic lesions of the dorsolateral pontomesencephalic tegmentum-cholinergic cell area in the cat. II Effects upon sleep-waking states. Brain Res. 1988;458:285–302. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90471-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Tokita S, Williams SC, Kisanuki YY, Marcus JN, Lee C, Elmquist JK, Kohlmeier KA, Leonard CS, Richardson JA, Hammer RE, Yanagisawa M. Distinct narcolepsy syndromes in orexin receptor-2 and orexin null mice. Molecular genetic dissection of non-REM and REM sleep regulatory processes. Neuron. 2003;38:715–730. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrenn CC, Picklo MJ, Lappi DA, Robertson D, Wiley RG. Central noradrenergic lesioning using anti-DBH-saporin: anatomical findings. Brain Res. 1996;740:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00855-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi MC, Morales FR, Chase MH. Evidence that wakefulness and REM sleep are controlled by a GABAergic pontine mechanism. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:2015–2019. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.4.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Fujiki N, Nakajima T, Ripley B, Matsumura H, Yoneda H, Mignot E, Nishino S. Fluctuation of extracellular hypocretin-1 (orexin A) levels in the rat in relation to the light–dark cycle and sleep–wake activities. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:1075–1081. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitzer JM, Buckmaster CL, Parker KJ, Hauck CM, Lyons DM, Mignot E. Orcadian and homeostatic regulation of hypocretin in a primate model: implications for the consolidation of wakefulness. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3555–3560. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03555.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]