Abstract

The ability to generate a wide spectrum of differentiated cell types from ES cells in culture offers a powerful approach for studying lineage induction and specification and a promising source of progenitors for cell replacement therapy. Although significant efforts are being made to optimize culture conditions for the generation of different cell populations from ES cells, the identification and efficient isolation of specific progenitors for many lineages within these cultures remains a major challenge. By specifically tracking hematopoietic and cardiac development, we demonstrate here that these two lineages arise from distinct mesoderm subpopulations that develop in sequential waves from pre-mesoderm cells. Access to these populations provides a unique approach to isolate and characterize the earliest progenitors of these lineages.

Keywords: cardiogenesis, hematopoiesis, brachyury

When allowed to differentiate in culture, ES cells generate colonies known as embryoid bodies (EBs) that contain a broad spectrum of cell types representing derivatives of the three germ layers (1, 2). Support for the ES cell differentiation system as a valid model of embryonic development has come from studies that demonstrate that the molecular and cellular events associated with the establishment of lineages such as the hematopoietic (3), endothelial (4), neural (5), and skeletal muscle (6) show striking similarities in the EBs and the early embryo. The ES cell/EB model has been particularly useful in elucidating the early events involved in the development of the hematopoietic system and has enabled the identification of a progenitor with characteristics of the hemangioblast, the putative precursor of the hematopoietic and endothelial lineages (7, 8). These progenitors, known as blast colony-forming cells (BL-CFCs), arise within 2–4 days of EB differentiation and express the tyrosine kinase receptor Flk1 (9, 10). When replated in methylcellulose cultures in the presence of VEGF, the BL-CFCs generate colonies with hematopoietic, endothelial, and vascular smooth muscle potential (7, 10, 11). These characteristics suggest that the BL-CFC could represent the in vitro equivalent of the yolk sac hemangioblast (12) and, as such, the earliest commitment step in the differentiation of mesoderm to the hematopoietic and endothelial lineages.

Cardiac development in ES cell differentiation cultures is also well established and is easily detected by the appearance of areas of contracting cells that display characteristics of cardiomyocytes (13). All of the cardiac cell types have been generated from differentiating EBs, and gene expression analyses suggest that their development in culture recapitulates cardiogenesis in the early embryo (14, 15). However, unlike hematopoietic development in the ES cell system, little progress has been made in identifying and characterizing early stage cardiac progenitors and in defining conditions that support the efficient differentiation of this lineage. This lack of progress is directly related to a lack of available markers for embryonic cardiac progenitors. To be able to use the ES cell system as a model for investigating the earliest events regulating cardiac lineage commitment as well as a reliable source of cells for replacement therapy, it is essential to identify markers for the isolation of different stage progenitors and to define conditions for the efficient differentiation of this lineage.

To track the developmental events involved in the induction and specification of mesoderm, we targeted GFP to the brachyury (Bry) locus (16). Brachyury, the founding member of the T-box family of transcription factors, is expressed in all nascent mesoderm and then down-regulated as these cells undergo patterning and specification into derivative tissues (17, 18). Using this model, we identified two populations of GFP+ mesoderm cells early in EB development that differed in their expression of Flk1. The subpopulation that coexpressed Flk1 contained the majority of BL-CFCs found within the EBs at this stage of development. The GFP+ population that did not express Flk1 had few BL-CFCs but did generate these precursors after 20 h of culture. The developmental potential of these two populations suggests that they represent a progression from prehemangioblast mesoderm (GFP+) to hemangioblast mesoderm (GFP+ Flk1+) (16). In the present study, we tested the cardiac potential of these two mesodermal populations and observed that only GFP+ cells developed into cardiomyocytes. We subsequently show that the generation of mesoderm with hematopoietic or cardiac potential was temporally controlled during the course of EB differentiation. Our data further suggest that both sets of mesodermal precursors were sequentially and independently generated from epiblast-like cells.

Materials and Methods

ES Cell Growth and Differentiation. ES cells were maintained and differentiated as described in ref. 16.

Colony Assay. For the generation of blast cell colonies, cells were plated in 1% methylcellulose containing 10% FCS (Atlas Biologicals, Ft. Collins, CO), VEGF (5 ng/ml), c-kit ligand (1% conditioned medium), IL-6 (5 ng/ml), and 25% D4T endothelial cell conditioned medium (7, 8). Blast colonies were scored after 4 days of culture.

Cardiac Assay. Sorted cells were reaggregated in StemPro-34 SFM serum-free medium (GIBCO)/2 mM l-glutamine (GIBCO/BRL)/transferrin (200 μg/ml)/0.5 mM ascorbic acid (Sigma)/4.5 × 10–4 M monothioglycerol. Cells were cultured for 20 h at a density of 4 × 105 cells per ml in ultra-low-attachment 24-well plates (Costar). Pools of aggregates or single aggregates were transferred to gelatin-coated plates and cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium supplemented with 10% knockout serum replacement (SR; GIBCO). The proportion of aggregates with beating cells was scored after 3 days of culture.

Immunohistochemical Staining. Aggregates or trypsinized colonies were plated on gelatin-coated coverslips and cultured for 2 days in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium with 10% serum replacement. Cells attached to coverslips were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, washed two times in PBS, permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100/PBS, and washed in 10% FCS/0.2% Tween 20/PBS. Cells attached to the coverslips were incubated for 1 h with an antibody against the cardiac isoform of troponin T (Lab Vision, Fremont, CA). Bound antibodies were visualized by using secondary FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Gene Expression Analysis. For gene-specific PCR, total RNA was extracted from each sample with an RNeasy kit and treated with RNase-free DNase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Two micrograms of RNA was reverse-transcribed by using an Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen). The PCRs were performed as described in ref. 16. The primer sequences are available upon request.

Flow Cytometry. EBs were harvested and trypsinized, and single-cell suspensions were analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) or sorted on a Moflo cell sorter (Cytomation, Ft. Collins, CO). Staining with a biotinylated Flk1 mAb was performed by incubating cells with mAb at the appropriate dilution for 30 min on ice in PBS/10% FCS. After one wash, biotinylated mAb were revealed with streptavidin Cy5 (Pharmingen). Anti-α-actinin (sarcomeric) (Sigma) staining was performed on trypsinized reaggregates in the presence of 0.3% saponin; after washing in 0.1% saponin, bound antibody was detected with a goat-anti-mouse FITC antibody (Caltag, South San Francisco, CA).

Results

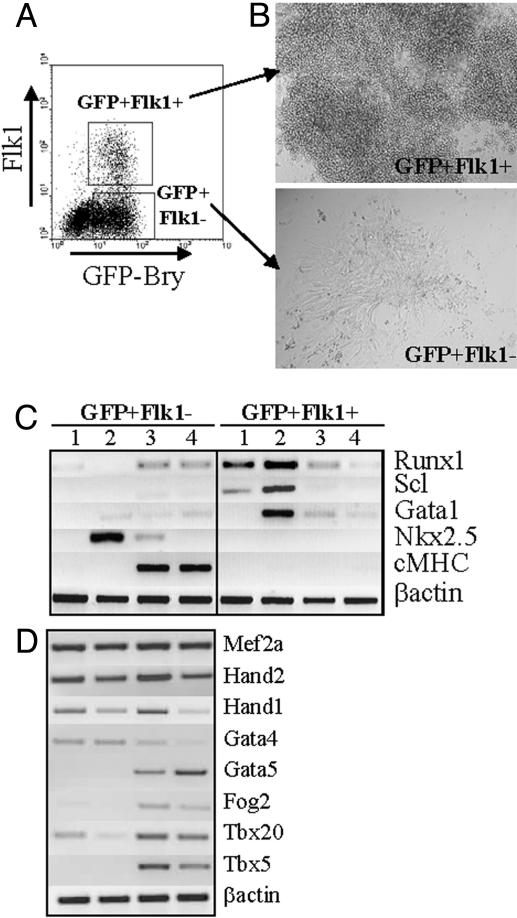

Cardiac Potential Is Restricted to the GFP+Flk1– Subpopulation. To further explore the developmental potential of the two GFP+ subpopulations differentially expressing Flk1, we tested their capacity to generate other mesoderm derivatives: specifically, cardiomyocytes. GFP+Flk– and GFP+Flk1+ fractions were isolated from day-3.25 EBs (Fig. 1A), allowed to reaggregate into EB-like structures, and then plated onto gelatin-coated dishes. After 3 days of culture, both sets of aggregates generated distinct cell outgrowths (Fig. 1B). The GFP+Flk1+-derived aggregates formed a layer of adherent cells covered by small, round, nonadherent cells. When replated with appropriate cytokines, the nonadherent cells generated hematopoietic colonies, indicating that this population contained cells of the hematopoietic lineage (not shown). The GFP+Flk– aggregates generated clusters of adherent cells that began contracting rhythmically within 2–3 days of culture, indicating differentiation to the cardiac lineage. The cardiomyocyte nature of these cells was confirmed by staining with an antibody against the cardiac isoform of the troponin-T protein (not shown). Optimal cardiomyocyte maturation was observed only when the aggregates were plated in serum-free cultures. Relatively few contracting cells developed in cultures supplemented with serum, suggesting that it contains inhibitors that impact the maturation of this lineage.

Fig. 1.

Cardiomyocyte potential of the GFP+Flk– and GFP+Flk1+ fractions. (A) At day 3.25 of differentiation, cells from GFP-Bry EBs were fractionated by cell sorting based on their respective levels of GFP and Flk1 expression. (B) Cells from both fractions were allowed to reaggregate in serum-free conditions for 20 h. Then, EB-like aggregates that formed were cultured on gelatin-coated dishes for several days. Representative colonies generated from aggregates from each fraction are shown. (C) Expression analysis of: freshly isolated GFP+Flk– and GFP+Flk1+ cells (lane 1), aggregates generated from the sorted cells (lane 2), and cells from aggregates cultured for 2 (lane 3) or 4 (lane 4) days. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Expression analysis of genes implicated in cardiomyocyte development performed on the same GFP+Flk– fractions as in lanes 1–4 in C. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

The lineage fate of these two mesodermal subpopulations was evaluated at the molecular level by expression analysis of genes associated with hematopoietic and cardiac development (Fig. 1C). Immediately after isolation, cells from the GFP+Flk1+ fraction, but not from the GFP+Flk– fraction, expressed Runx1 and Scl, transcription factors indicative of the onset of hematopoiesis (lane 1 in Fig. 1C) (19, 20). After aggregation, GFP+Flk1+ cells expressed Gata-1, consistent with further maturation along the hematopoietic lineage (lane 2). Cells within the GFP+Flk– aggregates up-regulated the expression of Nkx2.5, a transcription factor required for cardiac lineage specification (21). After additional culture, GFP+Flk– cells down-regulated Nkx2.5 and up-regulated cardiac myosin heavy chain (cMhc) expression, reflecting further maturation of the cardiomyocytes (lanes 3 and 4). Hematopoietic genes were not expressed in GFP+Flk– aggregates. The GFP+Flk1+ cells lost expression of Runx1 and Gata1 with time, likely reflecting suboptimal conditions for the growth and differentiation of hematopoietic cells. Nkx2.5 and cMhc expression was not detected in the GFP+Flk1+-derived cells. A more detailed analysis of cardiogenic gene expression was performed on the GFP+Flk– population (Fig. 1D). This analysis showed that some of the genes analyzed (mef2a, Hand1, and Hand2) are expressed at all stages of cardiomyocyte formation, whereas other genes are progressively down-regulated (Gata4) or up-regulated (Gata5, Fog2, and Tbx5) during cardiogenesis. Taken together, these findings indicate that the GFP+Flk– population contains early stage cardiac progenitors that undergo differentiation and mature to contracting cardiomyocytes when cultured under appropriate conditions.

It is possible that the lack of cardiac development from the GFP+Flk1+ cells resulted from the presence of inhibitors of this lineage within this population. To address this possibility, we mixed GFP+Flk– cells with cells from the GFP+Flk1+ population at different ratios (1:5–5:1). Cardiac activity was observed in all cultures, including those containing a much higher proportion of GFP+Flk1+ cells than GFP+Flk– cells (at ratios of 5:1). These findings strongly suggest that the lack of cardiomyocte potential in the GFP+Flk1+ population is not due to inhibition of the development of this lineage.

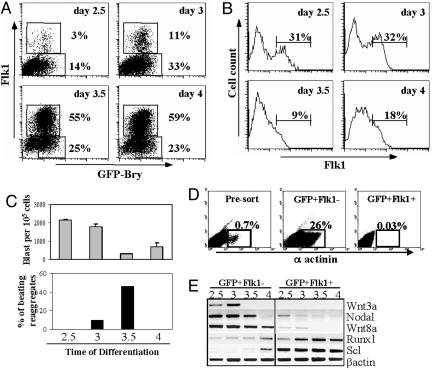

The Formation of Mesoderm with Cardiac and Hematopoietic Potential Is Temporally Controlled. We have previously demonstrated that the GFP+Flk– fraction from day-2.5 to day-3.0 EBs also contains prehemangioblast mesoderm (16). The hemangioblast and cardiac potential in this GFP+Flk– population could arise from bi- or multipotential mesodermal progenitors that are not committed to either fate and generate different lineages under different culture conditions. Alternatively, this GFP+Flk– population may consist of two (or more) distinct subpopulations of mesoderm, one fated to the hemangioblast lineage and one to the cardiac lineage. If the latter interpretation is correct and the EB model does recapitulate mesoderm specification in the embryo, it might be possible to separate these progenitors based on their kinetics of development. To investigate this possibility, we isolated GFP+Flk– cells at four different time points of differentiation (Fig. 2A) and assayed each for their potential to generate Flk1+ cells, BL-CFCs, and cardiomyocytes after reaggregation. All four GFP+Flk– populations generated Flk1+ cells (with either a low or high level of Flk1 expression) and BL-CFCs, although their potential to give rise to these cell types differed significantly. GFP+Flk– cells isolated from day-2.5 and -3.0 EBs generated a distinct Flk1+ subpopulation expressing high levels of the receptor (Fig. 2B). At days 3.5 and 4.0, the reaggregated GFP+Flk– fractions generated fewer Flk1+ cells expressing low levels of the receptor. The earliest GFP+Flk– fractions that generated the Flk1high cells also gave rise to highest numbers of BL-CFCs, indicating robust hematopoietic and vascular potential (Fig. 2C). The BL-CFC potential dropped sharply over the next 12 h and remained low thereafter. The temporal pattern of cardiac development appeared to be opposite that of the BL-CFCs. Aggregates from the earliest GFP+Flk– fractions did not give rise to contracting cells. Ten percent of the day-3.0 aggregates contained contracting cells; almost 50% of those from day-3.5 aggregates displayed this potential, whereas none from the day-4.0 aggregates generated this activity (Fig. 2C). These data support the interpretation that hemangioblast (BL-CFC) and cardiomyocyte lineages derive from distinct subpopulations of mesoderm that are present at different times within the EBs. They also demonstrate that cardiac potential is restricted to a narrow window of mesoderm development that is present within the EBs for 12–18 h. The identification of this cardiac mesoderm stage of development provides unique access to a population of highly enriched cardiomyocyte progenitors that cannot be isolated by any other approach.

Fig. 2.

Hemangioblast and cardiac potential of mesoderm subpopulations isolated at different stages of EB differentiation. (A) At the indicated day of differentiation, GFP-Bry EBs were harvested and dissociated, and the cells were isolated by sorting based on their respective levels of GFP and Flk1 expression. (B) Flk1 expression of cells within aggregates generated from each of the isolated GFP+Flk– subpopulations. (C) BL-CFC potential (gray bars) of aggregates derived from the different GFP+Flk– populations. Blast colonies, the progeny of the BL-CFCs, were scored after 4 days of culture. The cardiac potential (black bars) of the aggregates from each of the GFP+Flk– fractions was also determined. Aggregates were individually deposited into 96-well plates (48 aggregates per time point). The proportion of aggregates with beating cells was scored 4 days later. (D) α-Actinin staining 4 days after reaggregation. Although α-actinin (sarcomeric) stains both cardiac and skeletal muscle cells, no skeletal myosin staining was detected in the aggregates (data not shown). (E) Expression analysis of freshly isolated GFP+Flk– and GFP+Flk1+ cells from each time point. Data are representative of four independent experiments.

To quantify the extent of cardiomyocyte enrichment in this population, cells from cultures generated from the day-3.5 GFP+Flk–, GFP+Flk1+, and presort fractions were evaluated for α-actinin expression by flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 2D). α-Actinin-expressing cells were detected in cultures of GFP+Flk– cells within 2 days of plating of the aggregates, coincident with the onset of the appearance of contracting cells. Between 25% and 30% of the entire population expressed α-actinin by day 4, indicating that a significant proportion of the cells within the culture represent cardiomyocytes. Less than 1% of the population generated from unsorted EB cells expressed α-actinin, and no positive cells were detected in the cultures derived from the GFP+Flk1+ fraction. The low number of α-actinin cells in the cultures generated from the unfractionated population suggests that EBs contain cell types that inhibit the maturation of the cardiomyocyte lineage. These observations highlight the importance of isolating appropriate progenitor populations from mixed EB populations at early stages of development.

To further substantiate differences between the GFP+Flk– subpopulations, they were analyzed for expression of genes that are important in early mesoderm commitment and specification to the hematopoietic lineages. The corresponding GFP+Flk1+ fractions isolated at the same time points were included in these analyses. Two members of the Wnt family, Wnt3a and Wnt8a, which are expressed in the primitive streak (22, 23) and thought to play an important role in hematopoietic and cardiac specification (24, 25), were expressed in the GFP+Flk– but not in the GFP+Flk1+ populations (Fig. 2E). The expression pattern of Wnt3a was most striking, because it was present in the early GFP+Flk– populations containing the highest BL-CFC potential and down-regulated to undetectable levels by day 3.5 with the acquisition of cardiac potential. Expression of nodal, a member of the TGF-β superfamily of factors and essential for mesoderm induction in the embryo, was also restricted to the earliest GFP+Flk– populations (26). Runx1 and Scl were expressed predominantly in GFP+Flk1+ fractions, a finding that is consistent with the fact that these populations contain hematopoietic and vascular progenitors. Findings from these expression studies, together with the previous biological analyses, provide strong evidence that the GFP+Flk– populations isolated at different times of EB differentiation differ in developmental potential and, as such, represent distinct subpopulations of mesoderm.

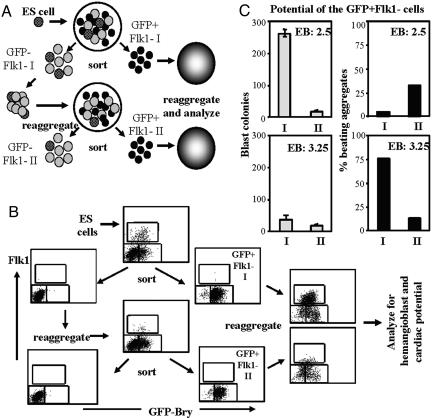

Mesoderm Subpopulations Are Sequentially Generated from Brachyury Negative Cells. The mesoderm subpopulations described here could develop from a common uncommitted population of mesoderm generated at an early time point within the EBs. In this scenario, the observed temporal patterns would reflect differences in the time required for specification and maturation of the hemangioblast and cardiac lineages from this uncommitted mesoderm. Alternatively, these mesoderm subpopulations may represent distinct lineages, each generated at specific times from premesodermal cells. We have previously demonstrated that GFP+Flk– cells are generated from a premesoderm EB population that does not express GFP or Flk1 (GFP–Flk–) (16). To distinguish between the above possibilities, we analyzed the hematopoietic and cardiac potential of successive waves of mesoderm derived from GFP–Flk– fractions isolated at different time points during ES cell differentiation (Fig. 3A). The goal of these experiments was to determine whether GFP+Flk– subpopulations derived from separate GFP–Flk– fractions would display similar or distinct developmental potential. To access distinct waves of mesoderm, GFP+Flk– and GFP–Flk– fractions (GFP+Flk– I and GFP–Flk– I) were isolated from EBs, and the cells of each fraction were allowed to reaggregate for 20 h. GFP+Flk– aggregates were analyzed for both hemangioblast and cardiac potential. The aggregated GFP–Flk– cells generated a GFP+Flk– subpopulation and more GFP–Flk– cells (Fig. 3A), which were both isolated (GFP–Flk– II and GFP+Flk– II). GFP+Flk– II cells were allowed to reaggregate, and the aggregates were assayed for hemangioblast and cardiac potential.

Fig. 3.

Developmental potential of sequential waves of mesoderm. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental procedure used to generate successive waves of mesoderm (GFP+Flk– I and GFP+Flk– II) from GFP-negative cell populations (GFP–Flk– I and GFP–Flk– II). (B) FACS profiles of the different populations from a typical experiment initiated from EBs at day 2.5 of differentiation. Each subpopulation was analyzed for expression of GFP and Flk1. (C) BL-CFC (gray bars) and cardiac (black bars) potential of the GFP+Flk– I and GFP+Flk– II populations derived from EBs harvested either at day 2.5 or 3.25 of differentiation. Cardiac potential was evaluated from the culture of individual aggregates in microtiter wells. Forty-eight aggregates were analyzed for each subpopulation. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Two sets of experiments were carried out, initiated at day 2.5 or 3.25 of EB differentiation. Fig. 3B shows the FACS plots of an experiment initiated at day 2.5. After reaggregation, the GFP+Flk– I fraction from day-2.5 EBs generated a significant Flk1high population and large numbers of blast colonies but very few beating aggregates (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the GFP+Flk– II fraction derived from the day-2.5 GFP–Flk– I cells gave rise to a small Flk1low population (Fig. 3B) and few blast colonies but did generate a substantial number of beating aggregates (Fig. 3C). From the experiment initiated at day 3.25 of EB differentiation, both GFP+Flk– fractions gave rise to small Flk1low populations after reaggregation (not shown). The GFP+Flk– I population displayed limited blast colony potential but did give rise to a high frequency (>70%) of beating aggregates (Fig. 3C). The GFP+Flk– II population derived from the GFP–Flk– I population at this stage gave rise to few blast colonies and few beating aggregates (Fig. 3C). The potential of this GFP+Flk– II population is currently unknown. These results demonstrate that two mesoderm populations generated at different times have different potential and support the interpretation of temporal specification of mesoderm within the ES cell/EB system.

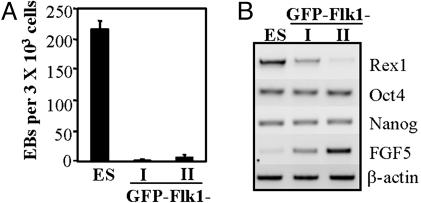

The GFP–Flk1– Subpopulation Represents an Epiblast-Like Stage of Development. Analysis of the GFP–Flk– populations revealed that they consisted of cell types that are more differentiated than ES cells. When cultured in methylcellulose, cells from the GFP–Flk– I and II fractions generated significantly fewer EBs than a population of undifferentiated ES cells (Fig. 4A). Gene expression analysis further revealed that the GFP–Flk– subpopulations were progressively down-regulating the transcription factor Rex1 while up-regulating FGF5, a gene expressed in the epiblast of the embryo. The expression of Nanog and Oct4 remain unchanged in the different populations (Fig. 4B), consistent with the fact that both genes are still expressed in epiblast cells of the gastrulating embryo (27, 28). These observations indicate that the GFP–Flk– populations are not simply residual ES cells but appear to consist of cells that represent a developmental progression spanning the epiblast stage, intermediate between ES cells and mesoderm.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of the GFP–Flk– subpopulations. (A) Undifferentiated ES cells and cells from GFP–Flk– I and GFP–Flk– II populations were tested for their ability to generate secondary EBs in methylcellulose cultures. Secondary EBs were scored after 6 days of culture. (B) Comparative gene expression analysis of ES cells and the two GFP–Flk– populations.

Discussion

The ability to track mesoderm induction and specification through the use of the GFP-Bry-targeted ES cells highlights the power of the ES cell/EB model system for elucidating the basic events regulating early development. In the present study, we have identified distinct mesoderm subpopulations with hemangioblast and cardiac fates that develop within EBs in a defined kinetic pattern. We demonstrated that these subpopulations of mesoderm are generated as successive waves from a premesodermal brachyury-negative population. The sequential appearance of hemangioblast and cardiac mesoderm in the EBs recapitulates the temporal specification of these populations in vivo (29), suggesting that developmental regulation of this germ layer in the ES cell/EB model may be similar to that of the early embryo. The generation of distinct waves of mesoderm with different biological potential provides direct evidence that these populations are induced with specific fates and do not acquire them after migration to inductive environments.

The cardiac mesoderm population that we have identified likely represents one of the earliest stages of cardiac development because the cells do not yet express Nkx2.5. Expression of Nkx2.5 is up-regulated after 24 h of aggregation, and contracting cells appear within 3 days of adherent culture. Differentiation of the lineage from the mesoderm stage in culture provides a unique model for studying the molecular and cellular events that regulate cardiogenesis. Up to 30% of the cells generated from the GFP+Flk– cardiac mesoderm were of the cardiac lineage, based on expression of α-actinin. Quantitative analyses in previous studies have estimated a low frequency (1% and 5%) of cardiac development in unmanipulated ES cell differentiation cultures (30). The frequency of cardiac cells in our cultures is at least 5- to 25-fold higher. By combining brachyury with other surface markers or targeted selectable markers, it should be possible to further enrich for progenitors representing different stages of cardiac development.

One of the most promising applications of the ES cell-derived cardiac differentiation is as a source of cells for replacement therapy for cardiovascular disease. Transplantation studies to date have used populations of relatively mature contracting cells physically isolated from differentiation cultures or isolated based on expression of selectable markers (31–35). In these studies, only low numbers of donor cells could be detected in the hearts of recipients, and only limited improvement in cardiac function was observed (34, 35). Given the low level of engraftment, it is unclear to what extent the improvement is due to the contractile function of the cells rather than to nonspecific beneficial effects such as secreted cytokines, etc. The GFP+Flk– cardiac mesoderm population identified here represents a unique population for cell replacement therapy for several reasons. First, it is enriched for cardiomyocyte potential. Second, it contains early stage progenitors that will proliferate as they mature after transplantation. This proliferative capacity has the potential to expand the size of the graft significantly, providing sufficient cells for repair of the damaged tissue. Third, these immature cells hypothetically have a greater ability to integrate electrically into the cardiac conduction system.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 HL 48834, R01 HL65169, R01 HL71800-01, Human Frontiers in Science Grant RG0345/1999-M 103, and Sonderforschungsbereich 497-Projekt A7 (H.J.F.).

Author contributions: V.K., G.L., and G.K. designed research; V.K., G.L., and S.S. performed research; H.J.F. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; V.K. and G.L. analyzed data; and V.K. and G.K. wrote the paper.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: EB, embryoid body; BL-CFC, blast colony-forming cell; Bry, brachyury.

References

- 1.Smith, A. G. (2001) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 17, 435–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keller, G. M. (1995) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 7, 862–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keller, G., Kennedy, M., Papayannopoulou, T. & Wiles, M. V. (1993) Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 473–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vittet, D., Prandini, M. H., Berthier, R., Schweitzer, A., Martin-Sisteron, H., Uzan, G. & Dejana, E. (1996) Blood 88, 3424–3431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bain, G., Kitchens, D., Yao, M., Huettner, J. E. & Gottlieb, D. I. (1995) Dev. Biol. 168, 342–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohwedel, J., Maltsev, V., Bober, E., Arnold, H. H., Hescheler, J. & Wobus, A. M. (1994) Dev. Biol. 164, 87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi, K., Kennedy, M., Kazarov, A., Papadimitriou, J. C. & Keller, G. (1998) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 125, 725–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishikawa, S. I., Nishikawa, S., Hirashima, M., Matsuyoshi, N. & Kodama, H. (1998) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 125, 1747–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthews, W., Jordan, C. T., Gavin, M., Jenkins, N. A., Copeland, N. G. & Lemischka, I. R. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 9026–9030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faloon, P., Arentson, E., Kazarov, A., Deng, C. X., Porcher, C., Orkin, S. & Choi, K. (2000) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 127, 1931–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ema, M., Faloon, P., Zhang, W. J., Hirashima, M., Reid, T., Stanford, W. L., Orkin, S., Choi, K. & Rossant, J. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 380–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huber, T. L., Kouskoff, V., Fehling, H. J., Palis, J. & Keller, G. (2004) Nature 432, 625–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boheler, K. R., Czyz, J., Tweedie, D., Yang, H. T., Anisimov, S. V. & Wobus, A. M. (2002) Circ. Res. 91, 189–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maltsev, V. A., Rohwedel, J., Hescheler, J. & Wobus, A. M. (1993) Mech. Dev. 44, 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sachinidis, A., Kolossov, E., Fleischmann, B. K. & Hescheler, J. (2002) Herz 27, 589–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fehling, H. J., Lacaud, G., Kubo, A., Kennedy, M., Robertson, S., Keller, G. & Kouskoff, V. (2003) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 130, 4217–4227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kispert, A. & Hermann, B. G. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 4898–4899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kispert, A. & Herrmann, B. G. (1994) Dev. Biol. 161, 179–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okuda, T., van Deursen, J., Hiebert, S. W., Grosveld, G. & Downing, J. R. (1996) Cell 84, 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begley, C. G., Aplan, P. D., Denning, S. M., Haynes, B. F., Waldmann, T. A. & Kirsch, I. R. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 10128–10132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyons, I., Parsons, L. M., Hartley, L., Li, R., Andrews, J. E., Robb, L. & Harvey, R. P. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 1654–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouillet, P., Oulad-Abdelghani, M., Ward, S. J., Bronner, S., Chambon, P. & Dolle, P. (1996) Mech. Dev. 58, 141–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takada, S., Stark, K. L., Shea, M. J., Vassileva, G., McMahon, J. A. & McMahon, A. P. (1994) Genes Dev. 8, 174–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider, V. A. & Mercola, M. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 304–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marvin, M. J., Di Rocco, G., Gardiner, A., Bush, S. M. & Lassar, A. B. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 316–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conlon, F. L., Lyons, K. M., Takaesu, N., Barth, K. S., Kispert, A., Herrmann, B. & Robertson, E. J. (1994) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 120, 1919–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hart, A. H., Hartley, L., Ibrahim, M. & Robb, L. (2004) Dev. Dyn. 230, 187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pelton, T. A., Sharma, S., Schulz, T. C., Rathjen, J. & Rathjen, P. D. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kinder, S. J., Tsang, T. E., Quinlan, G. A., Hadjantonakis, A. K., Nagy, A. & Tam, P. P. (1999) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 126, 4691–4701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zandstra, P. W., Bauwens, C., Yin, T., Liu, Q., Schiller, H., Zweigerdt, R., Pasumarthi, K. B. & Field, L. J. (2003) Tissue Eng. 9, 767–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klug, M. G., Soonpaa, M. H., Koh, G. Y. & Field, L. J. (1996) J. Clin. Invest. 98, 216–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muller, M., Fleischmann, B. K., Selbert, S., Ji, G. J., Endl, E., Middeler, G., Muller, O. J., Schlenke, P., Frese, S., Wobus, A. M., et al. (2000) FASEB J. 14, 2540–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanno, S., Kim, P. K., Sallam, K., Lei, J., Billiar, T. R. & Shears, L. L., II (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 12277–12281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Min, J. Y., Yang, Y., Converso, K. L., Liu, L., Huang, Q., Morgan, J. P. & Xiao, Y. F. (2002) J. Appl. Physiol. 92, 288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Min, J. Y., Yang, Y., Sullivan, M. F., Ke, Q., Converso, K. L., Chen, Y., Morgan, J. P. & Xiao, Y. F. (2003) J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 125, 361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]