Abstract

Introduction

Aggressive fibromatosis (AF) of the mandible is a rare, locally invasive tumor with significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. The incidence of AF in the head and neck region is estimated at 2–4 cases per 10 million people annually, with mandibular involvement being even less common. Its infiltrative nature and high recurrence risk necessitate meticulous surgical planning and prolonged follow-up.

Case presentation

A 15-year-old male presented with progressive left mandibular swelling and pain initially misdiagnosed as acute pulpitis. Imaging revealed a large soft tissue mass (64 mm × 68 mm) surrounding the left mandible with local bone destruction. Histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of aggressive fibromatosis. The patient underwent en bloc resection of the affected mandibular body and partial ramus, with preservation of vital structures. Despite conservative resection with 1–1.5 cm surgical margins, the patient experienced recurrence at 14 months post-surgery and underwent subsequent expanded tumor excision with mandibular segmental resection and fibular reconstruction at another institution.

Discussion

This case highlights the importance of accurate diagnosis and appropriate surgical management of mandibular AF. While our initial conservative approach was driven by economic constraints, the eventual recurrence necessitated more extensive surgery, emphasizing the importance of adequate surgical margins for this aggressive lesion.

Conclusion

Mandibular AF requires a comprehensive diagnostic approach and careful surgical planning. Clear surgical margins are essential to minimize recurrence risk, even if reconstruction must be delayed due to economic constraints. Long-term multidisciplinary follow-up is critical in pediatric cases both for tumor surveillance and to address developmental needs.

Keywords: Aggressive fibromatosis, Desmoid tumors, Diagnostic challenges, Surgical management, Recurrence risk, Case report

Highlights

-

•

Mandibular aggressive fibromatosis in pediatric patients is rare and poses diagnostic challenges.

-

•

Immunohistochemistry, including β-catenin and vimentin staining, was crucial for definitive diagnosis.

-

•

Complete surgical excision with clear margins is essential to minimize recurrence risk.

-

•

Long-term follow-up is necessary, with simultaneous reconstruction recommended during surgery.

1. Introduction

Aggressive fibromatosis (AF), also known as desmoid tumor, grade I fibrosarcoma, or fibromatosis of soft tissue, is a rare benign but locally invasive neoplasm characterized by infiltrative growth and a high propensity for recurrence. These tumors typically arise from deep musculoaponeurotic structures, including fascia, muscle, or periosteum, and demonstrate variable biological behavior [[1], [2], [3]]. While AF can occur at any age, it shows a distinct predilection for young individuals [4,5]. In the pediatric population, AF presents unique challenges in management, particularly with regard to the preservation of facial growth potential and functional outcomes [6,7].

The occurrence of AF in the head and neck region represents approximately 10–20 % of all desmoid tumors [8,9], with mandibular involvement being particularly rare. The anatomical complexity of this region, with its dense network of vital structures—including cranial nerves, major blood vessels, and growth centers—significantly complicates surgical management, particularly in pediatric patients [3]. In pediatric patients, mandibular AF poses additional challenges related to facial growth, functional preservation, and aesthetic considerations [4,10].

Clinical presentation of mandibular AF typically includes painless swelling with progressive growth, potentially leading to significant facial asymmetry and functional impairment [4,7]. The diagnostic approach requires a comprehensive evaluation, incorporating clinical examination, advanced imaging, and histopathological analysis. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) plays a crucial role in delineating tumor extent and its relationship to vital structures, while computed tomography (CT) better demonstrates bone involvement [11,12]. Histopathologically, AF is characterized by spindle-shaped fibroblasts within a collagenous matrix, with immunohistochemical analysis typically showing positivity for vimentin and smooth muscle actin, helping differentiate it from other spindle cell lesions [2].

The management of mandibular AF remains challenging, with surgical excision being the primary treatment modality [9]. The goal of achieving complete resection with clear margins must be balanced against the need to preserve vital structures and function, particularly in pediatric patients [13]. Surgical planning must consider both immediate functional outcomes and long-term growth potential [13,14]. While various adjuvant therapies including radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted molecular agents have been explored, their role remains controversial, especially in pediatric patients where long-term effects are of particular concern [15].

This case report presents an unusual instance of mandibular AF in a 15-year-old male, highlighting the diagnostic challenges and surgical considerations specific to the pediatric population. Through detailed documentation of our diagnostic approach, surgical intervention, and postoperative management, we aim to contribute to the existing literature on pediatric mandibular AF. Particular emphasis is placed on the importance of early diagnosis, careful surgical planning, and the need for long-term follow-up to monitor both tumor recurrence and facial development [6,7].

2. Clinical case

A 15-year-old male student initially presented with left posterior mandibular pain two months prior to admission. He was initially diagnosed with “acute pulpitis of tooth #37” at a local city hospital and underwent pulp extirpation, which failed to provide significant pain relief. Subsequently, he developed progressive left facial swelling, which was treated with traditional Chinese herbal medicine (details unavailable). The swelling gradually worsened, accompanied by intraoral mass formation, tongue displacement, and left lower lip numbness.

One month before presentation, the patient underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at a local prefecture hospital. The MRI revealed a large soft tissue mass (64 mm × 68 mm) surrounding the left mandible with local bone destruction. The mass appeared isointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted and fat-suppressed sequences, with high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted imaging. The tongue and left submandibular gland showed compression and displacement. Multiple lymph nodes were observed along bilateral cervical vessels, with the largest measuring 5 mm × 16 mm (Fig. 1A–D). A biopsy of the left mandibular lesion was performed, revealing a “spindle cell lesion of the left mandible.” The patient was referred to our institution for further pathological consultation and treatment.

Fig. 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of mandibular aggressive fibromatosis. (A–D) Images demonstrating destruction of the left mandibular body and ramus with extensive soft tissue expansion (64 mm × 68 mm) of the left face. The lesion appears isointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted and fat-suppressed sequences, with high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted imaging. Note the compression and displacement of the tongue and left submandibular gland, with multiple lymph nodes observed along bilateral cervical vessels.

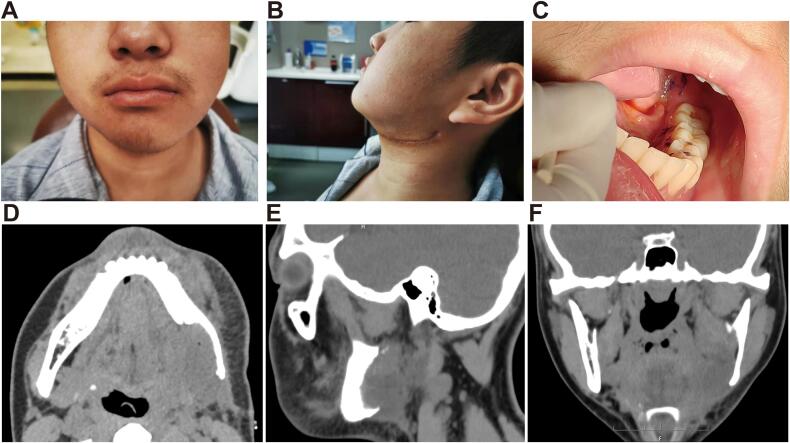

The patient was admitted to our hospital ten days prior to surgery. He denied any family history of similar conditions or history of smoking and alcohol consumption. Physical examination revealed facial asymmetry with significant left mandibular swelling. Palpation identified a firm, immobile mass measuring approximately 7 × 7 cm with poorly defined borders and no significant tenderness. The overlying skin and mucosa showed no obvious erosion. Intraoral examination revealed a firm, non-pedunculated mass measuring approximately 3 × 5 cm extending from tooth #35 to the distal aspect of #38 on the lingual side, covered with white pseudomembrane. The mass was non-tender but bled easily upon palpation. No enlarged lymph nodes were detected in the submental, submandibular, or cervical regions (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative findings of mandibular aggressive fibromatosis. (A) Preoperative view showing facial asymmetry with significant left mandibular swelling and intraoral firm, non-pedunculated mass extending from tooth #35 to the distal aspect of #38 on the lingual side. (B–D) Surgical resection demonstrating that the mandibular mass was continuous with the intraoral component, revealing extensive destruction of cortical and cancellous bone on the lingual aspect of the left mandible. Note the complete en bloc resection of the affected mandibular body and partial ramus with preservation of vital structures.

His past medical history was unremarkable, with no genetic disorders, prior surgeries, or family history of similar conditions. The patient lives with his parents in an urban setting, attending regular schooling, with good social support and no psychosocial concerns. He denied any history of trauma, smoking, alcohol consumption, or substance abuse.

Our institution's pathological consultation, including immunohistochemistry, suggested a benign fibrous proliferative lesion. Based on the clinical presentation, imaging characteristics, and pathological findings, we established a preliminary diagnosis of aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumor). Other differential diagnoses considered included low-grade spindle cell sarcomas (such as fibrosarcoma or leiomyosarcoma), which were excluded due to the absence of cellular atypia, active mitosis, or necrosis. Fibrous dysplasia (FD) and ossifying fibroma (OF) were also considered but ruled out due to the lack of typical “ground-glass” appearance or calcification on imaging. Neurogenic tumors (schwannoma/neurofibroma) were also considered but deemed less likely due to the absence of typical imaging features such as the “target sign” or cystic changes.

After explaining to the patient and family that the lesion was a “benign but locally aggressive tumor” with high recurrence potential, we initially proposed surgical treatment including mandibular resection with simultaneous reconstruction using titanium plates and vascularized free bone flaps (fibula or iliac). However, due to financial constraints and concerns about surgical risk, the family opted for a lump-only resection procedure with consideration of aesthetic reconstruction in adulthood.

After exclusion of surgical contraindications, the patient underwent surgery under general anesthesia. A submandibular approach was utilized for adequate exposure of the lesion. The surgical excision included removal of the tumor with surrounding normal soft tissue margin of approximately 1.5 cm (including involved muscles and the submandibular gland), while carefully preserving the facial nerve and its branches. Regarding bone resection, we employed a relatively conservative approach, removing approximately 1 cm of mandibular body and part of the left mandibular ramus. This conservative bone resection approach was adopted to balance adequate tumor removal with preservation of sufficient bone to maintain basic jaw function and prevent pathological fracture complications. The resection extended from the region of tooth #34 to the left mandibular angle (Fig. 2B–C).

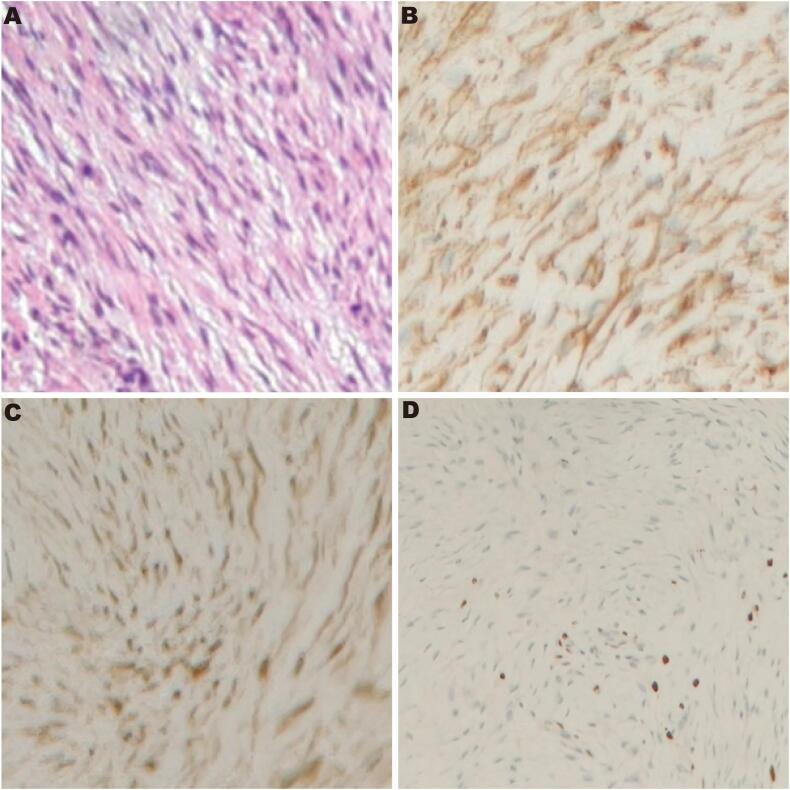

Under hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, aggressive fibromatosis (AF) exhibits a proliferation of spindle-shaped fibroblastic cells arranged in long fascicles or a storiform pattern. The nuclei are elongated or oval, with fine chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli, showing minimal cytologic atypia and a low mitotic rate (Fig. 3A). Postoperative immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of aggressive fibromatosis, showing positivity for vimentin (Vim+), positivity for β-catenin, with a Ki-67 proliferation index of approximately 3–5 % (Fig. 3C–D).

Fig. 3.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis confirming the diagnosis of aggressive fibromatosis. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (×100) showing proliferation of spindle-shaped fibroblastic cells arranged in long fascicles with minimal cytologic atypia and low mitotic rate. (B) Positive immunohistochemical staining for vimentin (×100), confirming the mesenchymal origin of the tumor cells. (C) Positive nuclear staining for β-catenin (×100), a characteristic finding in aggressive fibromatosis. (D) Ki-67 immunostaining (×100) demonstrating a proliferation index of approximately 3–5 %, consistent with the low proliferative activity typical of aggressive fibromatosis.

Postoperative management included seven days of intravenous antibiotics (ceftriaxone plus metronidazole) for oral flora coverage, daily oral care with chlorhexidine mouthwash, and soft brush cleaning of remaining teeth. The patient was maintained on a liquid diet (nasogastric) for 7 days to avoid masticatory movements.

At the two-week postoperative follow-up, the patient demonstrated favorable recovery with minimal facial asymmetry. Clinical examination revealed only slight residual swelling on the left side (Fig. 4A–B) and excellent intraoral healing with intact mucosa and no signs of infection, dehiscence, or recurrent disease (Fig. 4C). Two-week postoperative CT imaging confirmed complete tumor excision with clear surgical margins. The images demonstrated preservation of critical structures including the mandibular ramus and condyle, with the expected surgical defect in the left mandibular body corresponding to our planned resection margins (Fig. 4D–F). At the one-month postoperative follow-up, the patient showed good wound healing with no signs of recurrence. The patient was also seen at a three-month follow-up with continued good healing and no clinical signs of recurrence. The patient and his family were highly satisfied with the surgical outcome. Despite our recommendation for postoperative radiotherapy as adjuvant treatment to reduce recurrence risk, the family declined this option due to the patient's young age and financial constraints.

Fig. 4.

Postoperative assessment at one-month follow-up. (A) Frontal view showing acceptable facial symmetry with mild residual swelling on the left side. (B) Left lateral view demonstrating the healed submandibular surgical approach with minimal scarring. (C) Intraoral view showing well-healed mucosa with no signs of recurrence or infection. (D–F) Postoperative CT scan in axial, sagittal, and coronal views, respectively, demonstrating complete tumor resection with preservation of the mandibular ramus and condyle, though with significant bone defect in the left mandibular body region as expected after the resection procedure.

Unfortunately, the patient did not return for subsequent scheduled follow-ups. Through telephone follow-up conducted prior to this manuscript submission, we learned that the patient experienced tumor recurrence at 14 months post-surgery. He subsequently sought treatment at West China Hospital of Stomatology Sichuan University, where he underwent expanded tumor excision with mandibular segmental resection and fibular reconstruction. According to the family, the patient has been followed at that institution for over two years with no evidence of recurrence since the second surgery.

This study has been reported in line with the SCARE 2023 criteria [16].

3. Discussion

Aggressive fibromatosis (AF), also referred to as desmoid tumor, is a rare, benign yet locally invasive tumor that originates in the connective tissue, often from musculoaponeurotic structures. This tumor is characterized by infiltrative growth, frequent recurrence, and a tendency to invade adjacent tissues, though it does not metastasize [8,17]. While AF can occur at various sites, its involvement in the mandible, although infrequent, presents significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges [15,18].

In our case, the patient presented with a progressively enlarging mass in the left submandibular region, which was diagnosed as invasive fibromatosis following histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluation. AF involving the mandible, though rare, poses significant clinical challenges due to its aggressive growth pattern and the difficulty of achieving clear surgical margins while preserving vital structures such as the mandibular bone and soft tissues [3,7]. The clinical presentation of AF is often characterized by painless swelling or asymmetry, which can lead to diagnostic confusion, as seen in this case, where other differential diagnoses such as fibrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, and ossifying fibroma were considered initially [6].

The diagnosis of AF is primarily based on histopathological examination, which reveals spindle-shaped fibroblastic cells within a collagenous stroma. Immunohistochemical staining, such as positivity for vimentin and β-catenin, plays a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis and distinguishing AF from other spindle cell lesions [2,12]. In our case, the immunohistochemistry results, including positive staining for vimentin and β-catenin, as well as partial positivity for Ki-67, confirmed the diagnosis of invasive fibromatosis, consistent with previous reports of AF [4,19].

Surgical excision remains the mainstay of treatment for AF [20]. However, due to the infiltrative nature of the tumor, achieving clear surgical margins can be challenging, especially in the head and neck region where the involvement of critical anatomical structures is common. Despite this, complete excision is crucial to reduce the risk of recurrence [10]. In pediatric patients, such as the case presented here, maintaining the integrity of facial structures is particularly important due to the ongoing development of the facial skeleton [3,7]. Conservative resection techniques, such as marginal mandibulectomy, have been advocated in some cases to preserve mandibular continuity and function, while still achieving adequate tumor control [7].

Recurrence of AF is common, particularly when complete surgical excision is not achieved. It is reported that recurrence rates for AF in the head and neck region range from 30 % to 80 % [18,21], with higher rates observed in pediatric patients [1,4].In our case, despite what appeared to be adequate surgical margins (1–1.5 cm) at the time of initial surgery, tumor recurrence was observed at 14 months post-surgery. This underscores both the infiltrative nature of aggressive fibromatosis and the particular challenges of achieving complete tumor clearance in the anatomically complex mandibular region. Our experience aligns with previous studies suggesting that more aggressive resection may be necessary even in pediatric patients, where growth and developmental concerns must be balanced against oncological principles [15].

Adjuvant therapies, including radiotherapy, have been advocated to reduce recurrence risk in cases where complete surgical excision cannot be guaranteed [22,23]. However, the use of such modalities in pediatric patients remains controversial due to concerns about long-term effects on growth and development, as well as secondary malignancy risk [23]. In our case, postoperative radiotherapy was recommended as adjuvant treatment to reduce recurrence risk, particularly given our conservative surgical approach. However, the patient's family declined this option due to concerns about the patient's young age and financial constraints. We did not recommend chemotherapy or molecular targeted therapy in this case due to limited evidence for their efficacy in pediatric mandibular aggressive fibromatosis and potential toxicity concerns.

In conclusion, AF of the mandible presents significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. While surgery remains the primary treatment modality, careful consideration must be given to preserving function and aesthetics, particularly in children. The high recurrence rate emphasizes the need for long-term follow-up and, in some cases, adjuvant treatment to manage recurrence [24,25]. This case adds to the growing body of literature highlighting the importance of early diagnosis, adequate surgical resection, and vigilant postoperative monitoring in the management of aggressive fibromatosis [25,26].

4. Conclusion

This case report presents a rare instance of pediatric mandibular aggressive fibromatosis, demonstrating the critical importance of accurate diagnosis and appropriate surgical management. The initial conservative surgical approach, driven by economic constraints, ultimately resulted in recurrence at 14 months, necessitating more extensive secondary surgery with segmental mandibulectomy and reconstruction. This underscores the importance of obtaining clear surgical margins even in pediatric cases, where preservation of facial structures must be balanced against the high recurrence risk. Our experience suggests that while a conservative approach with 1–1.5 cm margins may appear adequate, the infiltrative nature of aggressive fibromatosis in the mandibular region may necessitate more radical resection or adjuvant therapy to prevent recurrence. Despite limited follow-up at our institution, the eventual successful outcome after secondary surgery highlights the value of a staged treatment approach when necessary. For clinicians managing similar cases, we recommend comprehensive diagnostic imaging, consideration of adjuvant therapy despite limited evidence, and close long-term follow-up to monitor for recurrence and address developmental needs in pediatric patients.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Conceptualization: Jiangying Yang; Data Collection: Jiangying Yang, Manuscript Drafting: Jiangying Yang; Literature Review: Xudong Tian, Ke Zhou; Surgical Assistance: Yadong Wu, Ke Zhou; Manuscript Review: Xudong Tian, Ke Zhou; Critical Revision of the Manuscript: Xudong Tian, Yadong Wu; Corresponding Author Responsibilities: Yadong Wu. All the authors approved the final article.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents/legal guardian for publication and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Ethics statement

This case report was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional ethics committee. Patient and his patient's parents/legal consents for publication were obtained prior to submission.

Guarantor

Hong Ma

Copyright transfer

We, the authors, hereby transfer all copyright ownership of the manuscript to International Journal of Surgery Case Reports upon its acceptance for publication.

Funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests related to this manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

- 1.Peña S., Brickman T., StHilaire H., Jeyakumar A. Aggressive fibromatosis of the head and neck in the pediatric population. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.10.058. (PMID: 24290952) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woods T.R., Cohen D.M., Islam M.N., Rawal Y., Bhattacharyya I. Desmoplastic fibroma of the mandible: a series of three cases and review of literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9(2):196–204. doi: 10.1007/s12105-014-0561-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee J.W., Bewley A.F., Senders C.W. Marginal versus segmental mandibulectomy for pediatric desmoid fibromatosis of the mandible - two case reports and review of the literature. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;109:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl. (PMID: 29728178) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D.L.van Broekhoven, D.J.Grünhagen, M.A.den Bakker, T.van Dalen, C.Verhoef. Time trends in the incidence and treatment of extra-abdominal and abdominal aggressive fibromatosis: a population-based study. Ann. Surg. Oncol., 22(9) (Sep 2015) 2817–2823, doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4632-y (PMID: 26045393). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Friedrich R.E., Grzyska U., Scheuer H.A., Zustin J. Desmoid-type infantile fibromatosis of the mandible: case report with long-term follow-up. In Vivo. 2010;24(6):877–881. (PMID: 21164048) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.S.Mohammadi, S.Mohammadi, F.Khosraviani, A Submandibular Fibromatosis; A Case Report and Review of Literature, Med J Islam Repub Iran, 36 (Aug 20 2022) 94, doi:10.47176/mjiri.36.94 (PMID: 36419942; PMCID: PMC9680815). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Zhou Y., Zhang Z., Fu H., Qiu W., Wang L., He Y. Clinical management of pediatric aggressive fibromatosis involving the mandible. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2012;59(4):648–651. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24145. (PMID: 22556010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato K., Kawana M., Nonomura N., Takahashi S. Desmoid-type infantile fibromatosis in the mandible: a case report. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2000;21(3):207–212. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(00)85026-7. (PMID: 10834557) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.K.S.Steuer, Pediatric fibromatosis requiring mandibular resection and reconstruction, AORN J, 62(2) (Aug 1995) 212, 215–224, 226, doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)63653-3 (PMID: 7486970). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.L.Seper, H.Bürger, J.Vormoor, U.Joos, J.Kleinheinz, Agressive fibromatosis involving the mandible--case report and review of the literature, Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod., 99(1) (Jan 2005) 30–38, doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.03.026 (PMID: 15599346). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Slootweg P.J., Müller H. Localized infantile myofibromatosis. Report of a case originating in the mandible, J Maxillofac Surg. 1984;12(2):86–89. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(84)80217-9. (PMID: 6585459) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arya A.N., Saravanan B., Subalakshmi K., Appadurai R., Ponniah I. Aggressive fibromatosis of the mandible in a two-month old infant. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2015;14(Suppl. 1):235–239. doi: 10.1007/s12663-012-0460-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeblaoui Y., Bouguila J., Haddad S., Helali M., Zaïri I., Zitouni K., et al. Fibromatose agressive mandibulaire [J] Rev. Stomatol. Chir. Maxillofac. Apr 2007;108(2):153–155. doi: 10.1016/j.stomax.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watzinger F., Turhani D., Wutzl A., Fock N., Sinko K., Sulzbacher I. Aggressive fibromatosis of the mandible: a case report. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2005;34(2):211–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom. (PMID: 15695054) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D.De Santis, Fibromatosis of the mandible: case report and review of previous publications, Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg., 36(5) (Oct 1998) 384–8, doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(98)90652-0 (PMID: 9831061). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Maria N., Kerwan A., Franchi T., Agha R.A., et al. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2023;109(5):1136–1140. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000373. (PMID: 37013953; PMCID: PMC10389401) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altmann S., Lenz-Scharf O., Schneider W. Therapeutic options for aggressive fibromatosis. Handchir. Mikrochir. Plast. Chir. 2008;40(2):88–93. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-965738. (PMID: 18437666) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carr R.J., Zaki G.A., Leader M.B., Langdon J.D. Infantile fibromatosis with involvement of the mandible. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1992;30(4):257–262. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(92)90271-j. (PMID: 1510902) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curry D.E., Al-Sayed A.A., Trites J., Wheelock M., Acott P.D., Midgen C., et al. Oral losartan after limited Mandibulectomy for treatment of Desmoid-type fibromatosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2023;102(2):49–52. doi: 10.1177/0145561320987641. (PMID: 33491484) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krokidis M., Raissaki M., Mantadakis E., Giannikaki E., Velegrakis G., Kalmanti M., et al. Infantile fibromatosis of the mandible: a case report. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2008;37(3):167–170. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/51942076. (PMID: 18316509) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bede S.Y., Ismael W.K., Abdullah B.H. Submandibular juvenile fibromatosis. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2013;24(4):e411–e413. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318292c956. (PMID: 23851885) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melrose R.J., Abrams A.M. Juvenile fibromatosis affecting the jaws. Report of three cases, Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980;49(4):317–324. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(80)90141-3. (PMID: 6928578) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bektas M., Bell T., Khan S., Tumminello B., Fernandez M.M., Heyes C., et al. Desmoid tumors: a comprehensive review. Adv. Ther. 2023;40(9):3697–3722. doi: 10.1007/s12325-023-02592-0. (PMID: 37436594) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.S.Buitendijk, C.P.van de Ven, T.G.Dumans,J.C. den Hollander, P.J.Nowak, W.J.Tissing, et al. Pediatric aggressive fibromatosis: a retrospective analysis of 13 patients and review of literature. Cancer 104(5) (Sep 1 2005) 1090–1099. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21275 (PMID: 16015632). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Turner B., Alghamdi M., Henning J.W., Kurien E., Morris D., Bouchard-Fortier A., et al. Surgical excision versus observation as initial management of desmoid tumors: a population based study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019;45(4):699–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso. (PMID: 30420189) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinno H., Zadeh T. Desmoid tumors of the pediatric mandible: case report and review. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2009;62(2):213–219. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31817f020d. (PMID: 19158537) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.