Abstract

The microbial oxidative cleavage of chitin, the second most abundant biopolymer in nature, generates a substantial amount of oxidized amino sugar, 2-(acetylamino)-2-deoxy-D-gluconic acid (GlcNAc1A). The catabolism of GlcNAc1A is key to the oxidative chitin degradation pathway. However, the molecular mechanism and evolution underlying this pathway remain elusive. Here, we target OngB, which initiates the GlcNAc1A catabolism, to explore the molecular mechanism driving the evolution of this process. We characterized PpOngB (the OngB from Pseudoalteromonas prydzensis ACAM 620) and its homologs as specific deacetylases for GlcNAc1A and solved the structures of WT PpOngB and its inactive mutant in complex with GlcNAc1A. Structural, mutational, and biochemical analyses revealed that PpOngB utilizes a D-aminoacylase-like (β/α)8-barrel fold to deacetylate GlcNAc1A in a metal-dependent manner. PpOngB and its homologs significantly differ from other known carbohydrate de-N-acetylases in sequences, substrate specificities, and structures. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that PpOngB and its homologs represent a new carbohydrate de-N-acetylase family, forming a sister group of D-aminoacylases involved in the catabolism of N-acetyl-D-amino acids. Further structural analysis suggested that GlcNAc1A deacetylases likely evolved from an ancestral D-aminoacylase, undergoing structural and electrostatic modifications in the catalytic cavity to hydrolyze GlcNAc1A. This study provides insights into the catalytic mechanism and the divergent evolution of GlcNAc1A deacetylases, advancing our understanding of oxidative chitin degradation.

Keywords: carbohydrate deacetylase, catalysis, evolution, oxidative chitin degradation, structural adaption

Chitin is the second most abundant biopolymer after cellulose in nature, providing a significant carbon and nitrogen source for bacterial growth (1, 2, 3). It is an insoluble linear polysaccharide of β-1,4 linked N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (GlcNAc). The crystalline structure and insolubility of chitin, often in conjunction with its embedding in complex matrices, contribute to its resistance to microbial hydrolysis. Since 2010, oxidative degradation initiated by lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMOs) has been recognized as essential to the efficient bioconversion of chitin and other recalcitrant polysaccharides (4, 5, 6, 7, 8). LPMOs create “nicks” on the surfaces of crystalline polysaccharides, promoting further degradation by traditional hydrolytic enzymes (4, 5, 6, 7, 8).

LPMOs require O2 or H2O2 as the final electron acceptor during catalysis (4, 8, 9). Molecular oxygen was introduced in the Earth’s atmosphere during the Great Oxidation Event, approximately 2.4 to 2.1 billion years ago (10, 11, 12). The presence of LPMOs likely emerged after molecular oxygen became available in Earth’s early environment (13). To date, all known chitin-active LPMOs only oxidize chitin to produce C1-oxidized chitooligosaccharides, which feature a terminal 2-(acetylamino)-2-deoxy-D-gluconic acid (GlcNAc1A) (6, 14, 15, 16, 17). GlcNAc1A is a hallmark intermediate of the oxidative chitin utilization pathway, differing from GlcNAc, a product from chitin degradation through the hydrolytic pathway, by both chemical structure and charge (Fig. 1). Recently, we reported the GlcNAc1A catabolic pathway in the Antarctic marine chitinolytic bacterium Pseudoalteromonas prydzensis ACAM 620 based on transcriptomic, gene KO and enzymatic product analyses (18). In this pathway, GlcNAc1A undergoes sequential conversions into 2-keto-3-deoxy phosphogluconate (KDG-6P) by enzymes OngB, OngC, and KdgK (Fig. 1). This pathway, however, diverges from the typical phosphorylation-initiated catabolism of GlcNAc and other monosaccharides (19, 20, 21) by directly deacetylating and deaminating GlcNAc1A without phosphorylation, resembling the N-acetyl-D-amino acid catabolism. The catabolism of GlcNAc1A may have evolved later, following the emergence of LPMOs. Despite its important role in oxidative chitin degradation, our understanding of the molecular mechanism and evolution of the GlcNAc1A catabolism remains quite limited.

Figure 1.

Chitin degradation pathways. The hydrolytic chitin utilization pathway begins with chitinases, which hydrolyze polymeric chitin into chitooligosaccharides. The catabolism of GlcNAc starts with phosphorylation, followed by deacetylation and deamination, ultimately producing fructose-6P. The oxidative chitin utilization pathway is initiated by LPMOs, which oxidize polymeric chitin into chitooligosaccharides with a terminal oxidized sugar, GlcNAc1A. The resulting oxidized chitooligosaccharides (1,5-δ-lactone) exist in pH-dependent equilibrium with their hydrates (aldonic acid). GlcNAc1A is then deacetylated and deaminated directly to produce KDG without phosphorylation activation, resembling the catabolism of N-acetyl-D-amino acids rather than other monosaccharides. OngB, the GlcNAc1A deacetylase that initiates the GlcNAc1A catabolism, is colored in red. GlcN, D-glucosamine; KDG, 2-keto-3-deoxygluconate; GlcNAc, N-acetyl-D-glucosamine; GlcNAc1A, 2-(acetylamino)-2-deoxy-D-gluconic acid; LPMO, lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase.

OngB, functioning as a carbohydrate de-N-acetylase, catalyzes the first step of the GlcNAc1A catabolic pathway by deacetylating GlcNAc1A to form 2-(amino)-2-deoxy-D-gluconic acid (GlcN1A) (Fig. 1). The deacetylation of GlcNAc1A is a key step due to its initiation of the GlcNAc1A pathway. Therefore, further studies on OngB are needed to gain insights into the molecular mechanism and evolution of the GlcNAc1A catabolism.

In the CAZy database, carbohydrate de-N-acetylases are grouped into carbohydrate esterase (CE) families 4, 9, 11, 14, and 18 according to sequence similarities and structural folds (22). CE4 enzymes, characterized by a (β/α)7-barrel fold, deacetylate structural polysaccharides including chitin, poly-β-1,6-GlcNAc, and peptidoglycan (23, 24, 25). CE9 enzymes, with a (β/α)8-barrel structure, catalyze the deacetylation of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcNAc-6P) in the GlcNAc catabolic pathway (26, 27). CE11 enzymes, which have a two-layer sandwich fold, are involved in lipid A biosynthesis by deacetylating UDP-3-O-acyl-GlcNAc (28, 29). CE14 enzymes, with an α/β fold, deacetylate the GlcNAc moiety of oligosaccharides (30), while the only characterized CE18 enzyme is a N-acetyl-galactosamine deacetylase with a (β/α)7-barrel fold distantly related to CE4 enzymes (31). These carbohydrate de-N-acetylases are all metal-dependent hydrolases, sharing a common metal-assisted acid/base mechanism (32, 33, 34). OngB, however, uniquely functions as a GlcNAc1A deacetylase in the GlcNAc1A catabolic pathway and shares no sequence homology with other known carbohydrate de-N-acetylases, suggesting that its structure and catalytic mechanism may differ from those previously reported. Due to the lack of structural information, the catalytic mechanism of GlcNAc1A deacetylases remains unknown. We found that OngB shares significant sequence homology to bacterial D-aminoacylases involved in the N-acetyl-D-amino acid catabolism. It is considered that both L- and D-amino acids existed on primal earth before the emergence of life (35, 36, 37, 38, 39). Thus, it is reasonable to hypothesize that OngB may have evolved from D-aminoacylases, and it is intriguing to uncover the underlying mechanism for driving a D-aminoacylase-like amidohydrolase, OngB, to evolve to hydrolyze the amino sugar, GlcNAc1A.

In this study, we characterized the OngB from P. prydzensis ACAM 620 (PpOngB) and solved the crystal structures of WT PpOngB and its inactive mutant in complex with GlcNAc1A. Based on structural and mutational analyses, the catalytic mechanism of PpOngB was illustrated. Phylogenetic and structural analyses suggested that PpOngB and its homologs define a new family of carbohydrate de-N-acetylases, adopting a D-aminoacylase-like (β/α)8-barrel fold. Furthermore, we explained the evolutionary divergence that enables PpOngB to function as a GlcNAc1A deacetylase. This study provides important clues for understanding the evolution of oxidative chitin degradation, particularly regarding the GlcNAc1A catabolism.

Results and discussion

Biochemical characterization of PpOngB

Among characterized enzymes, PpOngB is most closely related to the metal-dependent D-aminoacylases from Alcaligenes faecalis (AfDam) (40) and Bordetella bronchiseptica (BbDam) (41), with sequence identities of 46% and 42%, respectively. D-aminoacylases belong to the amidohydrolase superfamily, a structure-based cluster of enzymes that contain a sturdy and versatile triosephosphate isomerase (TIM)-like (β/α)8-barrel fold encompassing the catalytic active site (42, 43, 44). Based on metal-binding ligands, amidohydrolases are classified into nine subtypes (42, 43, 44). Both AfDam and BbDam are subtype V amidohydrolases, characterized by a Cys/His/His metal-binding site and a catalytic Asp residue (40, 41, 44). Sequence alignment indicated that PpOngB contains a typical metal-binding site of subtype V amidohydrolases, formed by Cys97, His222, and His252, with Asp368 likely serving as the catalytic residue (Fig. S1), suggesting that PpOngB is a member of subtype V amidohydrolases.

To investigate the substrate preference of PpOngB, we compared the activities of PpOngB, AfDam, and BbDam against a range of amino sugars and N-acetyl-D-amino acids (Figs. 2 and S2). Consistent with previous reports (40, 41), both AfDam and BbDam displayed deacetylase activities for N-acetyl-D-amino acids but were inactive toward GlcNAc1A or other amino sugars (Fig. S2, C and D), demonstrating their high substrate specificity for N-acetyl-D-amino acids. In contrast, PpOngB exhibited hydrolytic activity exclusively toward GlcNAc1A, with no detectable activity for any N-acetyl-D-amino acids (Fig. 2A), underscoring its strong substrate specificity for GlcNAc1A. We also examined two PpOngB homologs, PaOngB from Pseudoalteromonas arabiensis and PfOngB from Pseudoalteromonas flavipulchra DSM 14401, which share 76% and 57% sequence identities with PpOngB, respectively. Similar to PpOngB, both PaOngB and PfOngB deacetylated only GlcNAc1A (Fig. S2, A and B), further indicating that PpOngB, together with its homologs, functions as a carbohydrate deacetylase rather than a D-aminoacylase.

Figure 2.

Biochemical characterization and overall structural analysis of PpOngB.A, substrate specificity analysis of PpOngB at 30 °C in 10 mM Bis-Tris buffer (pH 7.5) using 10 mM substrate and 0.75 μM enzyme. The specific activity of PpOngB against GlcNAc1A (7.4 U/mg) was taken as 100%. The data shown in the graph are from triplicate experiments (mean ± S.D.). B, relative activities of the apo PpOngB with different metal ions. WT PpOngB was treated with 10 mM DPA to obtain the apo enzyme. The apo PpOngB (1.5 μM) was incubated with 5 μM metal ions for 0.5 h at 4 °C, and then the activity was determined against 10 mM GlcNAc1A in 10 mM metal-free Bis-Tris buffer (pH 7.5) at 30 °C. The enzyme activity of the WT PpOngB was set to 100%. The data shown in the graph are from triplicate experiments (mean ± S.D.) and were analyzed using an independent two-sample t test. ns indicates no statistically significant difference with a p value of 0.193, and ∗∗∗ indicates p < 0.001. C, reconstitution of the apo PpOngB with varying ratios of ZnCl2. The apo PpOngB (1.5 μM) was incubated with varying ratios of ZnCl2 for 20 h at 4 °C and then the activity was determined against 10 mM GlcNAc1A in 10 mM metal-free Bis-Tris buffer (pH 7.5) at 30 °C. The activity of the apo PpOngB with a 1:1 molar ratio of zinc was normalized to 100%. The data shown in the graph are from triplicate experiments (mean ± S.D.). D, structure of PpOngB in one asymmetric unit. The catalytic domain of PpOngB binds one Zn ion and one sulfate molecule. The catalytic residue Asp368 is shown as sticks. E, gel filtration analysis of recombinant PpOngB and markers. PpOngB monomer has a calculated molecular mass of 53.0 kDa. The two protein size markers are ovalbumin (43 kDa) and conalbumin (75 kDa). F, superimposition of the WT PpOngB, the PpOngB-GlcNAc1A complex and D-aminoacylases. PpOngB (cyan), the PpOngB-GlcNAc1A complex (green), AfDam (magenta) and BbDam (slate) are shown in different colors. GalNAc, N-acetyl-D-galactosamine; ManNAc, N-acetyl-D-mannosamine; MurNAc, N-acetylmuramic acid; Neu5Ac, N-acetylneuraminic acid; DPA, dipicolinate; GlcNAc, N-acetyl-D-glucosamine; GlcNAc1A, 2-(acetylamino)-2-deoxy-D-gluconic acid.

PpOngB exhibited the highest activity at 40 °C and remained stable at temperatures below 30 °C (Fig. S3, A and B). PpOngB was highly active at pH 7.0 to 7.5 (Fig. S3C). PpOngB appeared to be a metalloenzyme because 10 mM dipicolinate (DPA) completely abolished its activity against GlcNAc1A (Fig. 2B).

Overall structure of PpOngB

To elucidate the catalytic mechanism of GlcNAc1A deacetylases, we solved the crystal structure of WT PpOngB at a resolution of 1.77 Å resolution. Using molecular replacement with an AlphaFold2-generated model of PpOngB as the initial template, we refined the structure, with relevant statistics summarized in Table S1. Electron density was absent for the N-terminal residues Met1-Ser6 and C-terminal residues Leu483-Asp489. Crystals of PpOngB belongs to the P3121 space group, with one molecule per asymmetric unit (Fig. 2D). Gel filtration analysis confirmed that the WT PpOngB is monomeric in solution (Fig. 2E).

The overall structure of PpOngB is similar to those of subtype V amidohydrolases, most closely resembling the structures of D-aminoacylases AfDam (Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 1M7J) (40, 45) and BbDam (PDB code 3GIP) (41), with RMSDs of 0.81 Å (413 Cα atoms) and 1.16 Å (425 Cα atoms), respectively (Fig. 2F). Like these D-aminoacylases (40, 41), PpOngB comprises a catalytic domain (Gly63-Tyr415) and a smaller β-domain (Gln7-Pro62 and Arg416-Ser482) (Fig. 2D). The β-domain consists of eight β-sheets from both the N and C termini. The catalytic domain adopts a (β/α)8-barrel fold, with an insertion domain (Ser290-His347) containing four β-sheets and two α-helices inserted after β7. Reported carbohydrate de-N-acetylases and D-aminoacylases are all metal-dependent enzymes (32, 33, 34, 40, 41, 45). Although zinc is present in most proteins, other metals like iron, cadmium, cobalt, and copper can occasionally occupy the active site (32, 33, 34, 40, 41, 45). Electron density mapping of PpOngB indicates a metal ion within the active site. Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) revealed zinc as the predominant metal, occupying ∼78% of the PpOngB molecules, while iron and nickel each accounted for ∼5%. Furthermore, treatment of PpOngB with 10 mM DPA resulted in a complete loss in activity, which could be almost fully restored by the addition of Zn2+ (Fig. 2B). These results indicated that PpOngB is a metalloenzyme with a zinc ion bound in the active site. A conserved aspartate, critical for catalysis in AfDam, BbDam, and other subtype V amidohydrolases (40, 41, 44), corresponds to Asp368 in PpOngB. Asp368, located on the loop immediately following β8 from the (β/α)8-barrel and 5.15 Å away from the bound zinc in the active site, is most likely the key catalytic residue of PpOngB (Fig. 2D). In addition, the active site of the WT PpOngB also binds a sulfate molecule (Fig. 2D).

To investigate the interaction of PpOngB with the GlcNAc1A substrate, we mutated Asp368 to alanine. This resulted in full loss of enzymatic activity and enabled cocrystallization of PpOngB with GlcNAc1A. The crystals grew under the same conditions used for the WT protein. We then determined the crystal structure of PpOngB in complex with GlcNAc1A (the PpOngB-GlcNAc1A complex) at a resolution of 2.29 Å (Table S1). This complex formed monomers in the crystal and in solution, with overall structure closely matching that of the WT form (a RMSD of 0.24 Å across 465 Cα atoms) (Fig. 2F).

PpOngB is a mononuclear amidohydrolase

In the structure of WT PpOngB, a single zinc ion is exclusively coordinated at the β site within the active site (Fig. 3). The zinc ion is coordinated by Cys97, His222, and His252, as well as a sulfate molecule mediated by a water molecule (W1), along with a weakly interacting water molecule (W2) (3.46 Å) that is hydrogen bonded to the catalytic Asp368 (Fig. 3A). A five-coordinate zinc ion has also been observed in other zinc-dependent hydrolases (30, 46). In subtype V amidohydrolases, a Zn-coordinated water is essential for hydrolysis and is also hydrogen bonded to the conserved catalytic aspartate residue (42, 44). The distance between water molecule W1 and the catalytic Asp368 exceeds 4.25 Å, suggesting that no hydrogen bond is formed between them. Furthermore, the hydrolysis of GlcNAc1A by PpOngB is not affected by sodium sulfate at concentrations up to 600 mM (Fig. S4), indicating that water molecule W1 is not the hydrolytic water molecule. Instead, water molecule W2 not only coordinates the zinc ion but also forms a hydrogen bond with the side chain of the catalytic Asp368 (Fig. 3A), suggesting that this water molecule functions as the hydrolytic water molecule.

Figure 3.

PpOngB deacetylates GlcNAc1A in a metal-dependent manner.A, active site of the WT PpOngB with one Zn ion and one sulfate molecule bound. Sulfate is colored in orange. B, active site of the PpOngB-GlcNAc1A complex with one Zn ion and one GlcNAc1A molecule bound. GlcNAc1A is colored in yellow. C, detailed structure of the WT PpOngB. Sulfate is colored in orange. Residues involved in sulfate binding are shown as sticks, with residues from the (β/α)8-barrel colored in green and those from the insertion domain in slate. D, detailed structure of the PpOngB-GlcNAc1A complex. GlcNAc1A is colored in yellow. Residues involved in GlcNAc1A binding are shown as sticks, with residues from the (β/α)8-barrel colored in cyan and those from the insertion domain in slate. In (A)–(D), the 2Fo-Fc densities for key residues, meatal ions, water molecules, sulfate, and GlcNAc1A are contoured in gray at 1.0 σ, and possible hydrogen bonds are represented by dashed lines. E, enzymatic activities of PpOngB and its mutants. The activities were determined at 30 °C in 10 mM Bis-Tris buffer (pH 7.5) with 50 mM GlcNAc1A as the substrate. The specific activity of WT PpOngB (12.4 U/mg) was taken as 100%. The graph shows data from triplicate experiments (mean ± S.D.). F, proposed catalytic mechanism for PpOngB hydrolyzing GlcNAc1A into acetate and GlcN1A. GlcNAc1A, 2-(acetylamino)-2-deoxy-D-gluconic acid.

In the PpOngB-GlcNAc1A complex, the zinc ion remains bound at the β site, directly coordinated not only by Cys97, His222, and His252 but also by the bound GlcNAc1A molecule (Fig. 3B). Water molecule W2 is absent in the complex (Fig. 3B), likely due to the mutation of the hydrophilic Asp368 to the smaller hydrophobic alanine residue, rather than to the binding of the substrate GlcNAc1A. Mutating any of these residues to alanine led to an extremely low or no enzymatic activity (Fig. 3E), underscoring their essential roles in zinc ion binding. An additional potential binding site, the α site, is also present in PpOngB, which is surrounded by residues His68, His70, Cys79, and Asp368 (Fig. 3A). Previous studies have shown that, under high concentrations of metal ions such as zinc, copper, and cadmium, the α site in AfDam can bind a second metal ion, leading to attenuated enzyme activity (45). However, no electron density corresponding to a bound metal ion at this α site was observed in either the WT or complexed structures of PpOngB, as our crystallization experiments were conducted without the addition of external metal ions. To determine whether the active site in PpOngB requires one or two metal ions to be fully active, the apo enzyme was reconstituted by adding varying ratios of zinc ions. The maximum catalytic activity was observed at approximately a 1:1 molar ratio of zinc (Fig. 2C), demonstrating that PpOngB requires only a single zinc ion for its catalytic activity. Notably, the spatial proximities of His68-Nδ1 (3.35 Å) and His70-Nε2 (3.78 Å) to the catalytic Asp368-Oδ1 suggest that these residues may facilitate the catalysis of PpOngB. Mutation of either His68 or His70 in PpOngB to alanine abolished enzymatic activity completely (Fig. 3E), supporting their roles in catalysis. Based on the binding site(s) of the catalytically essential metal ion(s), amidohydrolases are classified into four types: αβ-binuclear, α-mononuclear, β-mononuclear, and metal-independent subsets (47). Our results indicate that PpOngB falls within the β-mononuclear subset. Furthermore, PpOngB possesses a subtype V metal-binding site composed of Cys97, His222, and His252, which are conserved among AfDam, BbDam, and other subtype V amidohydrolases (Fig. S5).

The substrate-binding mode of PpOngB

In the WT PpOngB, a sulfate molecule from the crystallization solution is bound in the active site (Fig. 3A). This sulfate, coordinated with the zinc ion via a water molecule, may occupy the binding position of the substrate carboxylate group. Sulfate is hydrogen bonded to the side chains of Lys254, Tyr285, Asp368, and Arg379 from the (β/α)8-barrel as well as to the side and main chains of Ser291 from the insertion domain (Fig. 3C), suggesting the roles of these residues in substrate binding.

In the aqueous environment, the amino sugar GlcNAc1A exists in equilibrium between two forms: the fused-ring 1,5-δ-lactone and the open-chain aldonic acid. Under alkaline conditions, GlcNAc1A in its fused-ring form spontaneously converts to the open-chain aldonic acid (4, 14). In buffers with pH values ranging from 6.0 to 8.0, the Km values of PpOngB were similar (Fig. S6A), suggesting that PpOngB has comparable affinities for both forms of GlcNAc1A. However, the kcat values of PpOngB were influenced by pH, with the maximum at pH 7.0 (Fig. S6B). In the structure of the PpOngB–GlcNAc1A complex, a clear electron density for GlcNAc1A in the open-chain aldonic acid form is visible in the catalytic cavity of PpOngB (Fig. 3B). The amide nitrogen atom of GlcNAc1A is spatially close to the catalytic D368A residue, while its amide oxygen atom coordinates the zinc ion (Fig. 3B). GlcNAc1A is further stabilized by hydrogen bond interactions (Fig. 3D). Its amide oxygen forms a hydrogen bond with the side chain of Tyr194, and the amide nitrogen forms a hydrogen bond with the main-chain CO group of Ser291. The α-carboxylate group aligns with the position of the sulfate molecule, forming hydrogen bonds with side chains of Lys254, Tyr285, and Arg379 and the main-chain CO and NH groups of Ser291. The C3-hydroxy group is hydrogen bonded to Ser292, while the C4-hydroxy group interacts with Glu226. The C5- and C6-hydroxy groups form hydrogen bonds with the side chain of Ser290, and the C5-hydroxy group is further stabilized by hydrogen bonding with the amide nitrogen of Gln298. Among these residues, Ser290, Ser291, Ser292, and Gln298 belong to the insertion domain, while the others are from the (β/α)8-barrel, mainly in its protruding loops (Fig. 3D). Additional hydrophobic interactions, involving Leu116 and Leu370, stabilize GlcNAc1A by interacting with the methyl group of its acetamido moiety. Structural superimposition suggested that no significant conformational change was observed for the metal-binding and substrate-binding residues of the WT PpOngB and its complex (Fig. S5). Alanine substitution of the identified residues led to complete or significant loss of enzymatic activity (Fig. 3E), highlighting their crucial roles in substrate binding. Specifically, Q298A and Q298N mutations severely decreased the kcat values of PpOngB and its affinity to GlcNAc1A (Table 1), further confirming the role of Gln298 in substrate binding via its side chain. CD spectroscopy analysis showed that the secondary structures of the mutants exhibit little deviation from that of WT PpOngB (Fig. S7), indicating that the changes in enzymatic activity and kinetic parameters of the mutants result from residue substitution rather than structural changes.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of PpOngB, PaOngB, PfOngB, and PpOngB mutantsa

| Type | Enzyme | Vmax (μmol/min/mg) | Km (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (mM−1 s−1)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | PpOngB | 17.4 ± 1.5 | 9.8 ± 0.8 | 15.4 ± 1.3 | 1.6 |

| PaOngB | 6.3 ± 0.3 | 9.1 ± 0.8 | 5.5 ± 0.3 | 0.6 | |

| PfOngB | 13.4 ± 0.8 | 17.2 ± 1.0 | 11.9 ± 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| PpOngB mutant | Q298A | 7.7 ± 0.7 | 59.7 ± 5.0 | 6.8 ± 0.6 | 0.11 (6.9%) |

| Q298N | 9.4 ± 0.3 | 53.4 ± 2.5 | 8.3 ± 0.3 | 0.16 (10.0%) | |

| S292T | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 54.2 ± 1.8 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.02 (1.3%) |

Reactions were conducted in triplicate in 10 mM Bis-Tris buffer (pH 7.5) at 30 °C using GlcNAc1A as the substrate over a concentration range of 2 to 120 mM.

Percentages in parentheses were calculated relative to wild-type PpOngB.

The catalytic mechanism of PpOngB

Based on our structural and biochemical results on PpOngB, along with known catalytic mechanisms of other carbohydrate de-N-acetylases (26, 34) and D-aminoacylases (40, 41), we propose the mechanism for PpOngB to catalyze the deacetylation of GlcNAc1A (Fig. 3F). PpOngB contains a subtype V mononuclear metal-binding site composed of Cys97, His222, and His252 to coordinate a water molecule in the active site. Upon substrate binding, GlcNAc1A enters the catalytic cavity and is stabilized mainly through hydrogen bond interactions with nine hydrophilic/polar residues from both the (β/α)8-barrel and the insertion domain. These interactions orient the amide bond of GlcNAc1A close to the zinc ion and the coordinated water molecule. Catalysis begins with Asp368 acting as a base, abstracting a proton from the water molecule to generate a nucleophilic hydroxide. This hydroxide ion attacks the amide carbon atom of GlcNAc1A, forming a tetrahedral oxyanion intermediate. Asp368 then switches its role to function as a catalytic acid, donating a proton to the amide nitrogen of the intermediate, which facilitates the cleavage of the amide bond and results in the release of acetate and GlcN1A as products (Fig. 3F). In addition, residues His68 and His70, conserved in PpOngB homologs and other subtype V amidohydrolases (Figs. 3A and S1), likely enhance the proton transfer capacity of Asp368 during the catalytic cycle.

PpOngB and its homologs represent a new carbohydrate de-N-acetylase family with a D-aminoacylase-like fold

To date, all characterized carbohydrate de-N-acetylases are metal-dependent hydrolases (32, 33, 34), which are distributed in five families including CE4, CE9, CE11, CE14, and CE18 (22). These enzymes adopt different structural folds and display different substrate specificities (Fig. 4). Among these families, CE4, CE9, and CE14 enzymes are involved in chitin degradation. CE4 enzymes with a (β/α)7-barrel fold deacetylate structural polysaccharides such as chitin, poly-β-1,6-GlcNAc, and peptidoglycan (23, 24, 25). CE14 enzymes adopt an α/β fold to deacetylate the GlcNAc moiety of oligosaccharides (30), whereas CE9 enzymes, featuring a (β/α)8-barrel structure, specially deacetylate GlcNAc-6P (26, 27, 47). Phylogenetic analysis using either IQ-TREE or RAxML revealed that PpOngB and its homologs form a distinct group separate from known carbohydrate de-N-acetylases, showing a closer relationship to D-aminoacylases than to other carbohydrate de-N-acetylases (Figs. 4, S8 and S9). Moreover, PpOngB and its homologs exhibit unique substrate specificity, selectively deacetylating GlcNAc1A, a hallmark intermediate of the oxidative chitin utilization pathway (Figs. 2, 4 and S2).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic and structural analyses of PpOngB and other carbohydrate de-N-acetylases. The tree, including 150 protein sequences, was constructed by the maximum-likelihood method using IQ-TREE. Bootstrap analysis of 1000 replicates is conducted and values above 80 are shown. A more detailed tree with source strain shown for each sequence is provided in Fig. S8. A representative structural fold is shown for the catalytic domains of each carbohydrate de-N-acetylase family. Close-ups of the active sites show catalytic residues, metal ions, and bound substrates/products/inhibitors. DA, de-N-acetylase; BHA, benzohydroxamic acid; myr-UDP-GlcN, UDP-(3-O-(R-3-hydroxymyristoyl))-glucosamine; PGN, peptidoglycan.

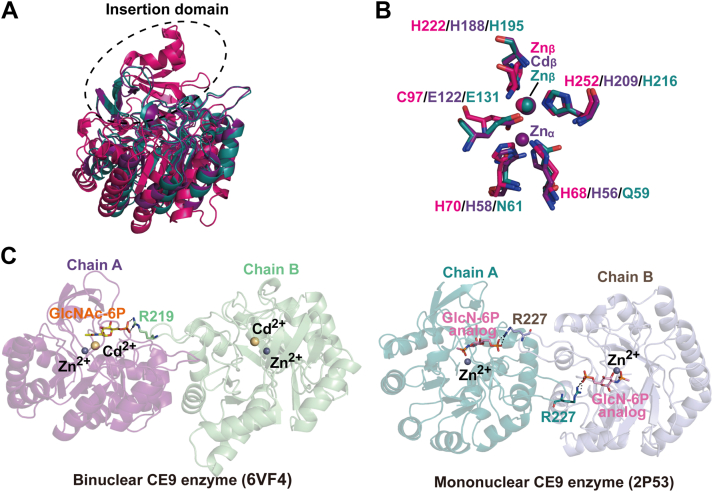

Among carbohydrate de-N-acetylases, only CE9 enzymes adopt the (β/α)8-barrel fold (26, 27, 34), but PpOngB has no sequence homology with CE9 enzymes. While both share the central (β/α)-fold, significant structural differences exist between PpOngB and CE9 enzymes with RMSDs exceeding 10.9 Å. PpOngB possesses a large insertion domain composed of four β-sheets and two α-helices, whereas CE9 enzymes contain small ones comprising only two β-sheets (Fig. 5A). Both PpOngB and CE9 enzymes are metal-dependent amidohydrolases, but their metal-binding sites differ. PpOngB and its homologs have a subtype V mononuclear metal-binding site composed of Cys/His/His, whereas the CE9 family include both mononuclear and binuclear members with a subtype IV metal-binding site comprising Glu/His/His (plus a HxH motif) (Fig. 5B). In PpOngB, the insertion domain is essential for substrate binding in its monomeric form (Fig. 3). In contrast, all characterized CE9 enzymes function as dimers (26, 27, 48), requiring a conserved Arg residue from one monomer to stabilize the phosphate group of the GlcNAc-6P substrate from the other monomer without the involvement of the insertion domain (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Comparative structural analyses of PpOngB and CE9 family GlcNAc-6P deacetylases.A, superimposition of the catalytic domains of PpOngB (magenta) and CE9 family GlcNAc-6P deacetylases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (purple) and E. coli (teal). Insertion domains of PpOngB and CE9 enzymes are marked by a black oval. B, superimposition of the metal-binding residues in PpOngB (magenta) and CE9 family GlcNAc-6P deacetylases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (purple) and E. coli (teal). C, dimerization of GlcNAc-6P deacetylases from the CE9 family. In CE9 enzymes, the bound substrate/product analog in monomer A is stabilized by an arginine residue from monomer B. GlcN-6P, D-glucosamine-6-phosphate; CE, carbohydrate esterase; GlcNAc-6P, N-acetyl-D-glucosamine-6-phosphate.

Together, PpOngB and its homologs significantly differ from other carbohydrate de-N-acetylases in sequences, substrate specificities, and structures. Therefore, we suggest that PpOngB and its homologs represent a new CE family with a D-aminoacylase-like fold.

Structure comparison of PpOngB and D-aminoacylases to reveal the structural basis for the formation of the carbohydrate deacetylase activity of PpOngB

Phylogenetic analysis revealed that PpOngB and its homologs form a separate group from D-aminoacylases (Figs. 4, S8 and S9), suggesting the divergent evolution of GlcNAc1A deacetylases from D-aminoacylase ancestors. Although PpOngB and D-aminoacylases share a similar topological structure, they differ in the shape and electrostatic profile of their catalytic cavities (Fig. 6). For these enzymes, the zinc ion and the catalytic residue Asp are all located near the bottom of their catalytic cavities. AfDam has a hydrophobic catalytic cavity with a negatively charged narrow opening, suitable for accommodating N-acetyl derivatives of hydrophobic amino acids, especially D-methionine (Fig. 6A). BbDam has a positively charged catalytic cavity near the opening, suited for stabilizing the negatively charged γ-carboxylate group of N-acetyl-D-glutamate (Fig. 6A). PpOngB, however, presents a positively charged catalytic cavity with a wide opening, accommodating GlcNAc1A and its four hydroxyl groups at the C3 to C6 positions (Fig. 6A). Compared to the narrow catalytic cavity mouth in AfDam (bound to two acetate molecules), the cavities in PpOngB and BbDam adopt a more open conformation, with loop structures that affect accessibility. In PpOngB, these loops correspond to residues Leu223-Ala229 from the (β/α)8-barrel (loop 1) and Leu294-Asp304 from the insertion domain (loop 2) (Fig. S10). The loop 2 of AfDam is closer to its loop 1, resulting in a more closed cavity, while PpOngB and BbDam maintain an open conformation regardless of substrate or inhibitor binding.

Figure 6.

Comparative structural analyses of PpOngB and D-aminoacylases.A, electrostatic surfaces of the catalytic cavities of PpOngB and D-aminoacylases, with positively charged regions shown in blue and negatively charged regions in red. The bound substrate/product/inhibitor is shown as sticks in different colors. The structural formula of the optimal substrate catalyzed by PpOngB, AfDam, and BbDam is also shown at the top. B, superposition of the active sites of PpOngB (cyan), AfDam (magenta), and BbDam (slate). Residues from the insertion domain are boxed. The GlcNAc1A in PpOngB is shown as cyan lines, and the phosphate inhibitor (N-phosphonomethyl-D-glutamic acid) from BbDam in slate lines. For clarity, only the metal ions at the β site are shown. C, an overview of the conservation of residues forming the catalytic cavities of PpOngB and its homologs and D-aminoacylases. Residues are numbered according to PpOngB. Residues forming the catalytic cavities of AfDam-like and BbDam-like D-aminoacylases are marked by solid and open circles, respectively. D, enzymatic activities of AfDam and its mutants. The activities were determined at 40 °C in 10 mM Bis-Tris buffer (pH 7.0) with 10 mM N-acetyl-D-methionine as the substrate. E, enzymatic activities of BbDam and its mutants. The activities were determined at 30 °C in 50 mM Hepes buffer (pH 8.0) with 10 mM N-acetyl-D-glutamate as the substrate. In (D) and (E), the graphs show data from triplicate experiments (mean ± S.D.), which were analyzed using an independent two-sample t test. ∗∗, p < 0.01; ∗∗∗, p < 0.001. GlcNAc1A, 2-(acetylamino)-2-deoxy-D-gluconic acid.

In PpOngB, residues Leu116, Tyr194, Tyr285, Lys254, Ser291, Asp368, Leu370, and Arg379 are involved in the coordination of the acetamido and α-carboxylate groups of GlcNAc1A (Fig. 3). Their counterparts in AfDam are involved in the binding of two acetate molecules, which occupy the positions of the acetate product and the α-carboxylate group of the substrate, respectively (40). These residues as well as metal ligands are strictly conserved in PpOngB-like, AfDam-like, and BbDam-like sequences (Fig. 6, B and C), suggesting a shared mechanism between GlcNAc1A deacetylases and D-aminoacylases for anchoring substrate acetamido and α-carboxylate groups. However, differences arise in substrate specificity due to variation in residues that bind other parts of the substrate. AfDam features a hydrophobic cavity, with residues Phe191, Met254, Leu298, Met346, and nearby hydrophobic/aromatic residues, suited for hydrophobic side chains of N-acetyl derivatives of D-methionine and other hydrophobic D-amino acids (40). Among these residues, except for Leu298, the others are largely conserved in BbDam. In BbDam, the counterpart of hydrophobic Leu298 in AfDam is replaced by a hydrophilic Arg295 to coordinate the γ-carboxylate group of N-acetyl-D-glutamate (41). By contrast, PpOngB is occupied by small/polar residues corresponding to Ala193, Ala256, Gln298, and Gly348 at the equivalent positions of the catalytic cavity (Fig. 6B), creating a slightly hydrophilic environment favorable for the hydroxyl groups of GlcNAc1A. Gln298, conserved in PpOngB and its homologs, stabilizes the C5-hydroxy group of GlcNAc1A via hydrogen bonding, which is replaced by a conserved hydrophobic Leu in AfDam-like sequences and a conserved basic Arg in BbDam-like sequences (Fig. 6, B and C). Mutating the residue at this site to alanine or other residues with opposite hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity in PpOngB, AfDam, and BbDam resulted in marked reduction or loss of enzymatic activities (Figs. 3E, 6, D and E), demonstrating the key role of this residue in determining substrate specificities of GlcNAc1A deacetylases and D-aminoacylases. Another key residue, Ser292, stabilizes the C3-hydroxy group of GlcNAc1A. This residue is replaced by threonine conserved in AfDam-like and BbDam-like sequences (Fig. 6, B and C), where its additional methyl group contributes hydrophobicity and impacts substrate recognition. Mutation of Ser292 to threonine in PpOngB significantly reduced its enzymatic activity and catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km), and conversely in AfDam and BbDam, Thr mutations had similar effects (Figs. 3E, 6, D and E, and Table 1). Both Ser292 and Gln298 and their counterparts are positioned in/near the loop 2 of the insertion domains of PpOngB and D-aminoacylases, emphasizing the role of this region in substrate recognition.

Based on the phylogenetic and structural analyses above, we propose that GlcNAc1A deacetylases might share a common D-aminoacylase ancestor with D-aminoacylases such as AfDam and BbDam and underwent a divergent evolution. The ancestral D-aminoacylase adopted structural modifications in its catalytic cavity, especially in electrostatics, to evolve into a GlcNAc1A deacetylase (Fig. 7A). Further analysis of the structures of functional homologs to PpOngB, AfDam, and BbDam, predicted by AlphaFold3 (49), indicated that structural modifications in the catalytic cavities drive the functional shift between GlcNAc1A deacetylases and D-aminoacylases (Fig. 7, B–D). The affinities of PpOngB and its homologs for GlcNAc1A are 1 to 2 orders of magnitude lower than those of AfDam (45) and BbDam (41) for N-acetyl-D-amino acids (Table 1), also supporting the hypothesis that GlcNAc1A deacetylases evolved later from D-aminoacylases. PpOngB-like sequences are abundant in marine Gammaproteobacteria and also found in terrestrial Gammaproteobacteria (18), suggesting that the emergence of GlcNAc1A deacetylases from D-aminoacylases is important for oxidative chitin degradation. Our study on GlcNAc1A deacetylases offers valuable insights into the evolution of the GlcNAc1A catabolic pathway, enhancing our understanding of oxidative chitin degradation.

Figure 7.

The proposed molecular mechanism driving the formation of the carbohydrate deacetylase activity of PpOngB and its homologs from D-aminoacylases.A, a proposed mechanism underlying the evolution of PpOngB. Structural modifications in the catalytic cavity of an ancestral D-aminoacylase, especially in electrostatics, are proposed to drive the evolution of PpOngB into a GlcNAc1A deacetylase. The bound substrates in PpOngB and D-aminoacylases are highlighted in orange. Key residue changes in the catalytic cavities of D-aminoacylases and PpOngB, which lead to their different electrostatic properties, are indicated in cyan (AfDam), slate (BbDam), and magenta (PpOngB), respectively. Interactions between AfDam and N-acetyl-D-methionine are shown based on molecular docking analysis. Possible hydrogen bonds are represented by dashed lines. B, superposition of the active sites of PpOngB (cyan), PaOngB (pale cyan), and PfOngB (deep teal) suggesting that PpOngB-like enzymes have similarly polar catalytic cavities. The bound GlcNAc1A in PpOngB is shown as cyan lines. C, superposition of the active sites of AfDam (magenta) and its homolog, AxDam (pink), suggesting that AfDam-like enzymes have similarly hydrophobic catalytic cavities. The two acetate molecules bound in AfDam are shown as magenta lines. D, superposition of the active sites of BbDam (slate) and its homolog, D-AGase (light blue), suggesting that BbDam-like enzymes have similar catalytic cavities with positively charged openings. The bound phosphate inhibitor in BbDam is shown as slate lines. In (B)–(D), the structures of two PpOngB homologs (PaOngB and PfOngB), an AfDam homolog (AxDam) and a BbDam homolog (D-AGase) are predicted using AlphaFold3, highlighting residues associated with their differently charged catalytic cavities in boxes. ACT, acetate; GlcNAc1A, 2-(acetylamino)-2-deoxy-D-gluconic acid.

Conclusions

Our biochemical characterization of PpOngB and its homologs confirms their specificity as GlcNAc1A deacetylases. Structural and mutational analyses identify essential residues involved in substrate binding and catalysis within PpOngB. This enzyme utilizes a D-aminoacylase-like (β/α)8-barrel fold for GlcNAc1A deacetylation in a metal-dependent manner. It is a β-mononuclear amidohydrolase with a subtype V metal-binding site. Phylogenetic and structural comparisons position PpOngB and its homologs as a new family of carbohydrate de-N-acetylases. The evolutionary adaptation of PpOngB likely stems from structural modifications in the catalytic cavity of an ancestral D-aminoacylase, particularly in electrostatic properties, allowing PpOngB to specialize as a GlcNAc1A deacetylase. Our study on GlcNAc1A deacetylases provides new insights into the mechanism of chitin catabolism via oxidative degradation. This study also establishes a connection between amino sugar catabolism and amino acid catabolism, shedding light on the evolution of oxidative chitin degradation, especially for the GlcNAc1A catabolism.

Experimental procedures

Gene cloning and mutagenesis

The PpongB gene was amplified from the genomic DNA of the marine bacterium P. prydzensis ACAM 620 and cloned into the vector pET-22b, which includes a His tag. Using the plasmid pET22b-PpongB as a template, site-directed mutations in PpOngB (Table S2) were introduced by a modified QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis method (50). Similarly, two homologs of PpongB, PaongB (GenBank accession no. WP_209438165), and PfongB (GenBank accession no. WP_039496229) from marine bacteria P. arabiensis and P. flavipulchra DSM 14401, respectively, were cloned. Additionally, we synthesized two D-aminoacylase-encoding genes, Afdam (40) and Bbdam (41), and constructed their mutants. All primers used in this study are listed in Table S2. All recombinant plasmids were verified by sequencing.

Protein expression and purification

Proteins including PpOngB, PaOngB, PfOngB, AfDam, BbDam, and their mutants were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3). Cells were cultured at 37 °C until the absorbance at 600 nm reached 0.6 and then induced by the addition of 0.2 mM IPTG at 16 °C for 20 h. Cells were collected and disrupted using the JN-02C French press (JNBIO) in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 100 mM NaCl and 5 mM imidazole. The recombinant proteins were initially purified by nickel affinity chromatography (QIAGEN) and subsequently fractionated by anion exchange on a SOURCE 15Q column (GE HealthCare). The target protein was then collected using gel filtration on a Superdex G-200 column (GE HealthCare). Conalbumin (75 kDa) and ovalbumin (43 kDa) were used as protein size standards. Protein concentration was determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the purified proteins were stored at −80 °C.

ICP-MS analysis

Purified PpOngB was desalted into metal-free buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.0). It was then digested in concentrated nitric acid to a final concentration of 10%. After filtering the sample, it was analyzed using ICP-MS (PerkinElmer). In addition to the standard calibrating solutions, buffer-spiked standards were used to minimize any interference from the buffer during metal analysis.

Biochemical characterization

The standard reaction system (50 μl) contained 10 mM Bis-Tris buffer (pH 7.5), 10 mM GlcNAc1A (Aladdin), and an appropriate concentration of enzyme. Reactions were incubated at 30 °C for 15 min and terminated by boiling for 15 min. The resulting primary amine products were measured using the ninhydrin reagent (51). Briefly, 20 μl of the reaction mixture was mixed with 100 μl of the ninhydrin-sodium citrate reagent and boiled for 20 min. After adding 500 μl of a 50% n-propanol solution, the reaction product was detected at 600 nm. One unit of enzyme activity (U) is defined as the amount of enzyme required to release 1 μmol of primary amine per min.

The optimum temperature for PpOngB activity was determined ranging from 10 to 60 °C at pH 7.5. For the thermostability assay, the enzyme was preincubated at 30 °C, 35 °C, and 40 °C for different time intervals, and the residual activity was measured at pH 7.5 and 30 °C. The optimum pH for PpOngB activity was determined ranging from pH 5.0 to 10.0 with Britton–Robinson buffer at 30 °C. Substrate specificity assays of PpOngB, PaOngB, PfOngB, AfDam, and BbDam were performed using various substrates, including amino sugars GlcNAc1A, GlcNAc, GalNAc, ManNAc, MurNAc, Neu5Ac, GlcNAc-GlcNAc1A, and (GlcNAc)2 as well as N-acetyl-D-amino acids such as N-acetyl-D-arginine, N-acetyl-D-glutamate, N-acetyl-D-serine, N-acetyl-D-alanine, N-acetyl-D-leucine, N-acetyl-D-methionine, N-acetyl-D-phenylalanine, N-acetyl-D-proline, N-acetyl-D-tryptophan, and N-acetyl-D-valine.

Enzyme kinetic assays of PpOngB, PaOngB, PfOngB, and PpOngB mutants were performed in 10 mM Bis-Tris buffer (pH 7.5) at 30 °C using GlcNAc1A as substrate over a concentration range of 2 to 120 mM. Kinetic parameters were calculated through nonlinear regression fitted directly to the Michaelis–Menten equation using Origin 9.0 software. The overall secondary structures of WT PpOngB and its mutants were studied at 25 °C using a J-810 CD spectropolarimeter (JASCO). CD spectra were collected from 200 to 250 nm at a scanning rate of 200 nm/min with a path length of 0.1 cm. The protein concentrations for CD spectroscopy assays were set at 0.1 mg/ml.

Preparation of the apo enzyme and its metal reconstruction

Trace metals in 10 mM Bis-Tris buffer (pH 7.5) were removed by a Chelex 100 chelating ion exchange resin (Bio-Rad) to prepare the metal-free buffer. To prepare the metal-free PpOngB, the WT enzyme (0.4 mg/ml) was dialyzed against 10 mM DPA in 10 mM metal-free Bis-Tris buffer (pH 7.5) using a 3.3 kDa molecular weight cutoff dialysis cassette, with three changes of the dialysis buffer over 2 days at 4 °C. The apo PpOngB was then desalted using a PD-10 desalting column (GE HealthCare) equilibrated with 10 mM metal-free Bis-Tris buffer (pH 7.5) to remove DPA.

To study the effect of different metal ions on PpOngB activity, the apo enzyme (1.5 μM) was incubated with 5 μM metal ions for 0.5 h at 4 °C, and its activity was determined with 10 mM GlcNAc1A substrate in 10 mM metal-free Bis-Tris buffer (pH 7.5) at 30 °C. For the metal reconstitution study, aliquots of the apo enzyme (1.5 μM) were incubated with 0 to 6 molar equivalents of ZnCl2 for 20 h at 4 °C. The enzymatic activity of the reconstituted protein was determined with 10 mM GlcNAc1A substrate in 10 mM metal-free Bis-Tris buffer (pH 7.5) at 30 °C.

Crystallization, data collection, and structure determination

The protein concentrations of PpOngB and its inactive mutant D368A for crystallization were 8.0 mg/ml in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) containing 100 mM NaCl. To obtain the crystals of the D368A mutant in complex with GlcNAc1A (the PpOngB–GlcNAc1A complex), D368A mutant was mixed with GlcNAc1A at a molar ratio of 1: 50 and then incubated at 4 °C for 4 h before crystallization. The crystals of the WT PpOngB and the PpOngB-GlcNAc1A complex suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained at 18 °C after 1 week in the buffer containing 0.5 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate (pH 6.0), and 1.0 M lithium sulfate monohydrate by the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method. All the X-ray diffraction data of crystals were collected on the BL19U1 beamline at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility using the PILATUS3 6M detector (52). Processing and scaling of raw data were performed using the HKL3000 program (53). The crystal structure of PpOngB was solved by molecular replacement using Phenix (54), with its modeled structure predicted by AlphaFold2 (55) as the staring model. Subsequent refinement was performed using Phenix (54) and Coot (56) alternately. The structure of the PpOngB-GlcNAc1A complex was determined using the crystal structure of PpOngB as the staring model. The qualities of the final models are summarized in Table S1. All the structure figures were processed using PyMOL program.

Protein structure prediction

Based on blasting analysis, the D-aminoacylase AxDam from Achromobacter xylosoxidans (formerly Alcaligenes xylosoxydans subsp. xylosoxydans A-6) (57) was identified as a homolog of AfDam with 86% sequence identity, which could deacetylate N-acetyl-D-methionine. Another D-aminoacylase, D-AGase, from A. xylosoxidans (58) was recognized as a homolog of BbDam with 80% sequence identity. D-AGase was characterized as a functional N-acyl-D-glutamate amidohydrolase (58). The structures of PaOngB, PfOngB, AxDam, and D-AGase were predicted using AlphaFold3 (49) and compared to analyze the catalytic cavities of PpOngB-like, AfDam-like and BbDam-like enzymes. In addition, Molegro Virtual Docker 6.0 (59) was used to conduct AfDam (PDB code 1M7J) and N-acetyl-D-methionine docking. The default docking parameters were adopted except that the number of runs, the max iterations, and the population size in each run were set to 50, 3000, and 100, respectively. Cluster analysis was performed on different poses with a RMSD threshold of 1.0 Å. The conformation with the lowest estimated binding energy was selected as the best probable binding mode.

Phylogenetic analysis

Characterized carbohydrate de-N-acetylases and their homologs from CE families 4, 9, 11, 14, and 18 were retrieved from the CAZy database. For each family, the source strains of selected protein sequences represented 6 to 14 of the most abundant bacterial/eukaryotic groups within this family at the genus level, with sequence identities within each family ranging from ≤27% to ≥88%. AfDam-like and BbDam-like D-aminoacylases, sharing intragroup sequence identities between 50% and 96%, were downloaded from the NCBI nr database. Based on the distribution of PpOngB in marine and terrestrial bacteria (18), PpOngB-like sequences were obtained from the NCBI nr database, sharing sequence identities between 50% and 99%. The selected D-aminoacylases and PpOngB-like sequences covered at least six of the most abundant bacterial genera containing AfDam-like, BbDam-like, or PpOngB-like sequences. To reveal the relationship between PpOngB-like sequences and other carbohydrate de-N-acetylases as well as D-aminoacylases, a total of 150 selected protein sequences were aligned using MAFFT v7.471 (60) with the -auto option, and trimmed using trimAl v1.4 (61) with the -gappyout option. Maximum likelihood trees were constructed using IQ-TREE v2.1.2 (parameters: -m LG + F + R10 -bb 1000 -bnni -seed 500) (62, 63) and RAxML v8.2.4 (parameters: raxmlHPC-PTHREADS-AVX -m PROTGAMMAAUTO -p 12,345 -x 12345 -N autoMRE) (64, 65), respectively. The resulting phylogenetic trees were visualized using the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v5 (66).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) 29.0. An independent two-sample t test was performed for pairwise comparisons.

Data availability

Atomic coordinates and structure factors of the wild-type PpOngB and the PpOngB-GlcNAc1A complex have been deposited in Protein Data Bank (PDB) under the accession numbers 9KB1 and 9KB3, respectively.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staffs from BL19U1 beamline of the National Facility for Protein Science Shanghai and Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility, for assistance during data collection. We also thank Xiaoju Li and Xueyun Geng of the Core Facilities for Life and Environmental Sciences, State Key laboratory of Microbial Technology of Shandong University for help and guidance on using the X-ray single crystal diffractometer. Additionally, we would like to thank Xianzhe Gong from the Institute of Marine Science and Technology, Shandong University, for his assistance with the phylogenetic analysis.

Author contributions

J.-P. W., X.-M. Z., X.-L. L., and W.-X. J. investigation; J.-P. W., X.-M. Z., X.-L. L., and W.-X. J. methodology; J.-P. W. data curation; J.-P. W. visualization; J.-P. W. writing–original draft; C. G., H.-Y. C., and H.-T. D. formal analysis; C. G., H.-Y. C., and H.-T. D. validation; Q.-L. Q., X.-L. C., and P.-Y. L. supervision; Q.-L. Q., Y.-Z. Z., and P.-Y. L. funding acquisition; X.-L. C. and P.-Y. L. writing–review and editing; Y.-Z. Z. and P.-Y. L. conceptualization.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC2807503 to Q.-L. Q.), the Marine S&T Fund of Shandong Province for Qingdao Marine Science and Technology Center (2022QNLM030004–3 to Y.-Z. Z.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42176229 to P.-Y. L., 42376106 to P.-Y. L., 32330001 to Y.-Z.Z., W2441012 to Y.-Z. Z., and 32400108 to W.-X. J.), Shandong Postdoctoral Science Foundation (SDBX2023009 to W.-X. J.), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023TQ0188 to W.-X. J.), the Taishan Scholars Program of Shandong Province, China (tsqn202306092 to Y.-Z. Z.), and the SKLMT Frontiers and Challenges Project (SKLMTFCP-2023–06 to Y.-Z. Z.).

Biography

Jing-Ping Wang is a doctoral student at the State Key Laboratory of Microbial Technology, Shandong University. Her work focuses on the molecular mechanisms and evolution of oxidative chitin degradation, particularly the catabolism of 2-(acetylamino)-2-deoxy-D-gluconic acid (GlcNAc1A). Through biochemical, structural and phylogenetic analyses, she uncovered the catalytic mechanism of GlcNAc1A deacetylase and its divergent evolution from D-aminoacylases. Her work highlights a novel carbohydrate de-N-acetylase family, providing insights into microbial adaptation to chitin utilization.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Joseph Jez

Contributor Information

Yu-Zhong Zhang, Email: zhangyz@sdu.edu.cn.

Ping-Yi Li, Email: lipingyipeace@sdu.edu.cn.

Supporting information

References

- 1.Muzzarelli R.A.A. Pergamon Press; UK: 1977. Chitin. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gooday G.W. The ecology of chitin degradation. Adv. Microb. Ecol. 1990;11:387–430. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manno C., Fielding S., Stowasser G., Murphy E.J., Thorpe S.E., Tarling G.A. Continuous moulting by Antarctic krill drives major pulses of carbon export in the north Scotia Sea, Southern Ocean. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:6051. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19956-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaaje-Kolstad G., Westereng B., Horn S.J., Liu Z., Zhai H., Sorlie M., et al. An oxidative enzyme boosting the enzymatic conversion of recalcitrant polysaccharides. Science. 2010;330:219–222. doi: 10.1126/science.1192231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eibinger M., Sattelkow J., Ganner T., Plank H., Nidetzky B. Single-molecule study of oxidative enzymatic deconstruction of cellulose. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:894. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01028-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forsberg Z., Sorlie M., Petrovic D., Courtade G., Aachmann F.L., Vaaje-Kolstad G., et al. Polysaccharide degradation by lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2019;59:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabbadin F., Urresti S., Henrissat B., Avrova A.O., Welsh L.R.J., Lindley P.J., et al. Secreted pectin monooxygenases drive plant infection by pathogenic oomycetes. Science. 2021;373:774–779. doi: 10.1126/science.abj1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munzone A., Eijsink V.G.H., Berrin J.G., Bissaro B. Expanding the catalytic landscape of metalloenzymes with lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2024;8:106–119. doi: 10.1038/s41570-023-00565-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bissaro B., Streit B., Isaksen I., Eijsink V.G.H., Beckham G.T., DuBois J.L., et al. Molecular mechanism of the chitinolytic peroxygenase reaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117:1504–1513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1904889117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canfield D.E., Ngombi-Pemba L., Hammarlund E.U., Bengtson S., Chaussidon M., Gauthier-Lafaye F., et al. Oxygen dynamics in the aftermath of the Great Oxidation of Earth's atmosphere. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:16736–16741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315570110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo G., Ono S., Beukes N.J., Wang D.T., Xie S., Summons R.E. Rapid oxygenation of Earth's atmosphere 2.33 billion years ago. Sci. Adv. 2016;2 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olejarz J., Iwasa Y., Knoll A.H., Nowak M.A. The great oxygenation event as a consequence of ecological dynamics modulated by planetary change. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:3985. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23286-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Decembrino D., Cannella D. The thin line between monooxygenases and peroxygenases. P450s, UPOs, MMOs, and LPMOs: a brick to bridge fields of expertise. Biotechnol. Adv. 2024;72 doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2024.108321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loose J.S.M., Forsberg Z., Fraaije M.W., Eijsink V.G.H., Vaaje-Kolstad G. A rapid quantitative activity assay shows that the colonization factor GbpA is an active lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase. Febs Lett. 2014;588:3435–3440. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabbadin F., Hemsworth G.R., Ciano L., Henrissat B., Dupree P., Tryfona T., et al. An ancient family of lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases with roles in arthropod development and biomass digestion. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:756. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03142-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skane A., Minniti G., Loose J.S.M., Mekasha S., Bissaro B., Mathiesen G., et al. The fish pathogen Aliivibrio salmonicida LFI1238 can degrade and metabolize chitin despite gene disruption in the chitinolytic pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021;87 doi: 10.1128/AEM.00529-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao R.A., Reyre J.L., Tamburrini K.C., Haon M., Tranquet O., Nalubothula A., et al. The Ustilago maydis AA10 LPMO is active on fungal cell wall chitin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023;89 doi: 10.1128/aem.00573-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang W.X., Li P.Y., Chen X.L., Zhang Y.S., Wang J.P., Wang Y.J., et al. A pathway for chitin oxidation in marine bacteria. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:5899. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33566-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang C., Rodionov D.A., Li X., Laikova O.N., Gelfand M.S., Zagnitko O.P., et al. Comparative genomics and experimental characterization of N-acetylglucosamine utilization pathway of Shewanella oneidensis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:29872–29885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605052200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodionov D.A., Yang C., Li X., Rodionova I.A., Wang Y., Obraztsova A.Y., et al. Genomic encyclopedia of sugar utilization pathways in the Shewanella genus. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:494. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leyn S.A., Gao F., Yang C., Rodionov D.A. N-acetylgalactosamine utilization pathway and regulon in proteobacteria: genomic reconstruction and experimental characterization in Shewanella. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:28047–28056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.382333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drula E., Garron M.L., Dogan S., Lombard V., Henrissat B., Terrapon N. The carbohydrate-active enzyme database: functions and literature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:D571–D577. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L., Xia Y., Li Y., Zhou Y., Su X., Yan X., et al. Inhibition of chitin deacetylases to attenuate plant fungal diseases. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:3857. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-39562-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little D.J., Milek S., Bamford N.C., Ganguly T., DiFrancesco B.R., Nitz M., et al. The protein BpsB is a poly-beta-1,6-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine deacetylase required for biofilm formation in Bordetella bronchiseptica. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:22827–22840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.672469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blair D.E., Schuttelkopf A.W., MacRae J.I., van Aalten D.M. Structure and metal-dependent mechanism of peptidoglycan deacetylase, a streptococcal virulence factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:15429–15434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504339102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vincent F., Yates D., Garman E., Davies G.J., Brannigan J.A. The three-dimensional structure of the N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase, NagA, from Bacillus subtilis: a member of the urease superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:2809–2816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahangar M.S., Furze C.M., Guy C.S., Cooper C., Maskew K.S., Graham B., et al. Structural and functional determination of homologs of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase (NagA) J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:9770–9783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coggins B.E., McClerren A.L., Jiang L., Li X., Rudolph J., Hindsgaul O., et al. Refined solution structure of the LpxC-TU-514 complex and pKa analysis of an active site histidine: insights into the mechanism and inhibitor design. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1114–1126. doi: 10.1021/bi047820z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clayton G.M., Klein D.J., Rickert K.W., Patel S.B., Kornienko M., Zugay-Murphy J., et al. Structure of the bacterial deacetylase LpxC bound to the nucleotide reaction product reveals mechanisms of oxyanion stabilization and proton transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:34073–34080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.513028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maynes J.T., Garen C., Cherney M.M., Newton G., Arad D., Av-Gay Y., et al. The crystal structure of 1-D-myo-inosityl 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-alpha-D-glucopyranoside deacetylase (MshB) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals a zinc hydrolase with a lactate dehydrogenase fold. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:47166–47170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bamford N.C., Le Mauff F., Van Loon J.C., Ostapska H., Snarr B.D., Zhang Y., et al. Structural and biochemical characterization of the exopolysaccharide deacetylase Agd3 required for Aspergillus fumigatus biofilm formation. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2450. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16144-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura A.M., Nascimento A.S., Polikarpov I. Structural diversity of carbohydrate esterases. Biotechnol. Res. Innov. 2017;1:35–51. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burger M., Chory J. Structural and chemical biology of deacetylases for carbohydrates, proteins, small molecules and histones. Commun. Biol. 2018;1:217. doi: 10.1038/s42003-018-0214-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pascual S., Planas A. Carbohydrate de-N-acetylases acting on structural polysaccharides and glycoconjugates. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2021;61:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujii N., Saito T. Homochirality and life. Chem. Rec. 2004;4:267–278. doi: 10.1002/tcr.20020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deamer D.W., Dick R., Thiemann W., Shinitzky M. Intrinsic asymmetries of amino acid enantiomers and their peptides: a possible role in the origin of biochirality. Chirality. 2007;19:751–763. doi: 10.1002/chir.20434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brack A. From interstellar amino acids to prebiotic catalytic peptides: a review. Chem. Biodivers. 2007;4:665–679. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller S.L. A production of amino acids under possible primitive earth conditions. Science. 1953;117:528–529. doi: 10.1126/science.117.3046.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Service R.F. New origin of life theory may explain biomolecular handedness. Science. 2024;383:937–938. doi: 10.1126/science.ado9325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liaw S.H., Chen S.J., Ko T.P., Hsu C.S., Chen C.J., Wang A.H., et al. Crystal structure of D-aminoacylase from Alcaligenes faecalis DA1. A novel subset of amidohydrolases and insights into the enzyme mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:4957–4962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210795200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cummings J.A., Fedorov A.A., Xu C., Brown S., Fedorov E., Babbitt P.C., et al. Annotating enzymes of uncertain function: the deacylation of D-amino acids by members of the amidohydrolase superfamily. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6469–6481. doi: 10.1021/bi900661b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seibert C.M., Raushel F.M. Structural and catalytic diversity within the amidohydrolase superfamily. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6383–6391. doi: 10.1021/bi047326v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khurana J.L., Jackson C.J., Scott C., Pandey G., Horne I., Russell R.J., et al. Characterization of the phenylurea hydrolases A and B: founding members of a novel amidohydrolase subgroup. Biochem. J. 2009;418:431–441. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugrue E., Fraser N.J., Hopkins D.H., Carr P.D., Khurana J.L., Oakeshott J.G., et al. Evolutionary expansion of the amidohydrolase superfamily in bacteria in response to the synthetic compounds molinate and diuron. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81:2612–2624. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04016-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lai W.L., Chou L.Y., Ting C.Y., Kirby R., Tsai Y.C., Wang A.H., et al. The functional role of the binuclear metal center in D-aminoacylase: one-metal activation and second-metal attenuation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:13962–13967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spencer J., Murphy L.M., Conners R., Sessions R.B., Gamblin S.J. Crystal structure of the LasA virulence factor from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: substrate specificity and mechanism of M23 metallopeptidases. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;396:908–923. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hall R.S., Brown S., Fedorov A.A., Fedorov E.V., Xu C., Babbitt P.C., et al. Structural diversity within the mononuclear and binuclear active sites of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7953–7962. doi: 10.1021/bi700544c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kroef V., Ruegenberg S., Horn M., Allmeroth K., Ebert L., Bozkus S., et al. GFPT2/GFAT2 and AMDHD2 act in tandem to control the hexosamine pathway. Elife. 2022;11 doi: 10.7554/eLife.69223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wee J., Wei G.-W. Benchmarking AlphaFold3's protein-protein complex accuracy and machine learning prediction reliability for binding free energy changes upon mutation. ArXiv. 2024 [preprint] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xia Y., Chu W., Qi Q., Xun L. New insights into the QuikChange process guide the use of Phusion DNA polymerase for site-directed mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Friedman M. Applications of the ninhydrin reaction for analysis of amino acids, peptides, and proteins to agricultural and biomedical sciences. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:385–406. doi: 10.1021/jf030490p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Z., Pan Q., Yang L., Zhou H., Xu C., Yu F., et al. Automatic crystal centring procedure at the SSRF macromolecular crystallography beamline. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2016;23:1323–1332. doi: 10.1107/S160057751601451X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Minor W., Cymborowski M., Otwinowski Z., Chruszcz M. HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution--from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:859–866. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906019949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adams P.D., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Hung L.W., Ioerger T.R., McCoy A.J., Moriarty N.W., et al. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jumper J., Evans R., Pritzel A., Green T., Figurnov M., Ronneberger O., et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wakayama M., Katsuno Y., Hayashi S., Miyamoto Y., Sakai K., Moriguchi M. Cloning and sequencing of a gene encoding D-aminoacylase from Alcaligenes xylosoxydans subsp. xylosoxydans A-6 and expression of the gene in Escherichia coli. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1995;59:2115–2119. doi: 10.1271/bbb.59.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wakayama M., Ashika T., Miyamoto Y., Yoshikawa T., Sonoda Y., Sakai K., et al. Primary structure of N-acyl-D-glutamate amidohydrolase from Alcaligenes xylosoxydans subsp. xylosoxydans A-6. J. Biochem. 1995;118:204–209. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bitencourt-Ferreira G., de Azevedo W.F., Jr. Molegro virtual docker for docking. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019;2053:149–167. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9752-7_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Katoh K., Standley D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Capella-Gutierrez S., Silla-Martinez J.M., Gabaldon T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nguyen L.T., Schmidt H.A., von Haeseler A., Minh B.Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gong X., Xu L., Langwig M.V., Chen Z., Huang S., Zhao D., et al. Globally distributed marine Gemmatimonadota have unique genomic potentials. Microbiome. 2024;12:149. doi: 10.1186/s40168-024-01871-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gong X., Del Rio A.R., Xu L., Chen Z., Langwig M.V., Su L., et al. New globally distributed bacterial phyla within the FCB superphylum. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:7516. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34388-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Letunic I., Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W242–W245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Atomic coordinates and structure factors of the wild-type PpOngB and the PpOngB-GlcNAc1A complex have been deposited in Protein Data Bank (PDB) under the accession numbers 9KB1 and 9KB3, respectively.