Highlights

-

•

Primary peritoneal serous borderline tumors are rare epithelial proliferations with low malignant potential.

-

•

Primary peritoneal serous borderline tumors are often misdiagnosed as undiagnosed diffuse primary ovarian carcinomas.

-

•

Accurate diagnosis guides conservative management and preserves fertility options.

-

•

Minimally invasive surgery ensures effective tumor removal and faster recovery.

-

•

Long-term monitoring is key to detecting rare recurrences and ensuring survival.

Keywords: Primary peritoneal serous borderline tumors, Serous borderline tumors, Primary peritoneal tumor, Serous tumor, Serous borderline tumor, Minimally invasive surgery

Abstract

Primary peritoneal serous borderline tumors (PPSBT) are epithelial proliferations with low malignant potential, but they are rare entities. Due to their rarity, PPSBTs are often misdiagnosed as undiagnosed diffuse primary ovarian carcinomas. This leads to unnecessary and more aggressive treatments. Tough, accurate recognition of PPSBT is crucial in clinical practice. This narrative review examines the current literature to provide practical guidance on the diagnosis and management of PPSBT. A key methodological choice in this review is the inclusion of a clinical case, which serves to contextualize the literature evidence in a real-world scenario. The case involves a 51-year-old asymptomatic woman who underwent laparoscopic excision and staging of a 99x51 mm mass, later confirmed as a PPSBT staged IA sec FIGO. The patient’s recovery was uneventful, and she remains disease-free after two years. This case, one of the few laparoscopically treated examples in the literature, underscores the value of minimally invasive surgery for both excision and staging and reinforces the importance of accurate diagnosis in improving clinical outcomes for PPSBT.

1. Introduction

Primary peritoneal serous borderline tumors (PPSBT) are rare epithelial proliferations with low malignant potential, classified as part of the broader category of Peritoneal Surface Malignancies (PSM). PSM are a heterogeneous group of cancers with significant variation in incidence, sensitivity to systemic therapies, and prognosis. Despite these differences, PSM share a propensity for peritoneal dissemination, posing significant management challenges (Cortés-Guiral et al., 2021).

Within this category, PPSBT represents a distinct and particularly rare subset. One of the main challenges in managing PPSBT is its frequent misdiagnosis, often as peritoneal implants from an undiagnosed primary ovarian carcinoma. This misdiagnosis is facilitated by the fact that PPSBT is often asymptomatic, or when symptoms do appear, they are nonspecific, such as abdominal or pelvic pain (Dallenbach-Hellweg, 1987 Apr, Genadry et al., 1981). Moreover, histologically, PPSBT may resemble other conditions, presenting as focal or diffuse lesions that mimic adhesions or cystic formations. The diagnostic ambiguity is clear when we delve in the historical terminology used before the current nomenclature was established, where PPSBT was referred to as atypical endosalpingiosis (Biscotti and Hart, 1992), primary papillary peritoneal neoplasia (Fox, 1993 Aug), or peritoneal serous micropapillomatosis of low malignant potential (Dallenbach-Hellweg, 1987 Apr).

While patients with PPSBT generally have a favorable prognosis, with low recurrence rates and no reported cancer-related deaths, the frequent misdiagnosis can lead to unnecessarily aggressive treatments, particularly in women of reproductive age. Historically, most cases have been managed via laparotomy, with very few cases treated laparoscopically. This raises critical questions about the optimal management of PPSBT: Is minimally invasive surgery safe for both excision and staging? What is the appropriate follow-up? Does PPSBT require adjuvant therapy?

To address these diagnostic and management challenges, we conducted a narrative review of the literature to provide practical guidance for clinicians navigating the management of PPSBT. Additionally, we present a clinical case of PPSBT managed through laparoscopic excision and staging, one of the few such cases documented in the literature, with a follow-up of two years. This case helps to contextualize the evidence from the literature and offers real-world insights into the diagnosis and management of PPSBT.

2. Materials and methods

This narrative review was conducted to synthesize the current literature on PPSBT, with a focus on providing practical guidance for clinicians navigating the challenges of diagnosis and management. Two research groups, C.M., L.P., R.G., and V.I., A.M.C.S.C., M.B., independently performed literature searches using PubMed and Scopus databases to identify relevant studies.

2.1. Literature search strategy

The search strategy focused on articles related to PPSBT, PSM, and laparoscopic management. Search terms included “Primary Peritoneal Serous Borderline Tumor,” “PPSBT,” “Peritoneal Surface Malignancies,” and “laparoscopy OR (minimally invasive AND (surgery OR technique OR procedure)).” The search encompassed all the studies published, and both peer-reviewed studies and grey literature were included. No strict inclusion or exclusion criteria were applied, allowing for the flexibility necessary in a narrative review. Studies were selected based on their relevance to the diagnostic and management challenges associated with PPSBT, particularly those that provided insights into the risk of misdiagnosis and the evolving role of minimally invasive surgery.

2.2. Justification for inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were chosen based on their contribution to key themes such as misdiagnosis, treatment challenges, and surgical management of PPSBT. The iterative nature of the narrative review allowed for multiple cycles of searching, analysis, and interpretation. This approach ensured that both seminal studies and more recent articles addressing the specific clinical challenges were included. Pivotal studies that contributed significantly to the understanding of PPSBT were prioritized to ensure a comprehensive review.

2.3. Reflexivity and sufficiency

The authors acknowledge that the selection of literature was influenced by their clinical experience in managing PPSBT and that the review does not aim to be exhaustive. Instead, the focus was on selecting studies that provide practical guidance for clinicians. Analysis continued iteratively until thematic saturation was achieved, with sufficient clarity on key issues such as misdiagnosis, treatment approaches, and the use of minimally invasive surgery.

2.4. Inclusion of a clinical case

To enhance the practical relevance of this review, we included a clinical case of a 51-year-old asymptomatic woman who underwent laparoscopic excision and staging of a 99x51 mm mass, later confirmed as PPSBT (FIGO stage IA). This case is one of the few documented instances of laparoscopic management for both excision and staging. The patient's post-operative follow-up, which shows no recurrence after two years, provides a real-world scenario to contextualize the literature evidence and offers valuable insights into the safe and effective management of PPSBT using minimally invasive techniques.

3. Case report

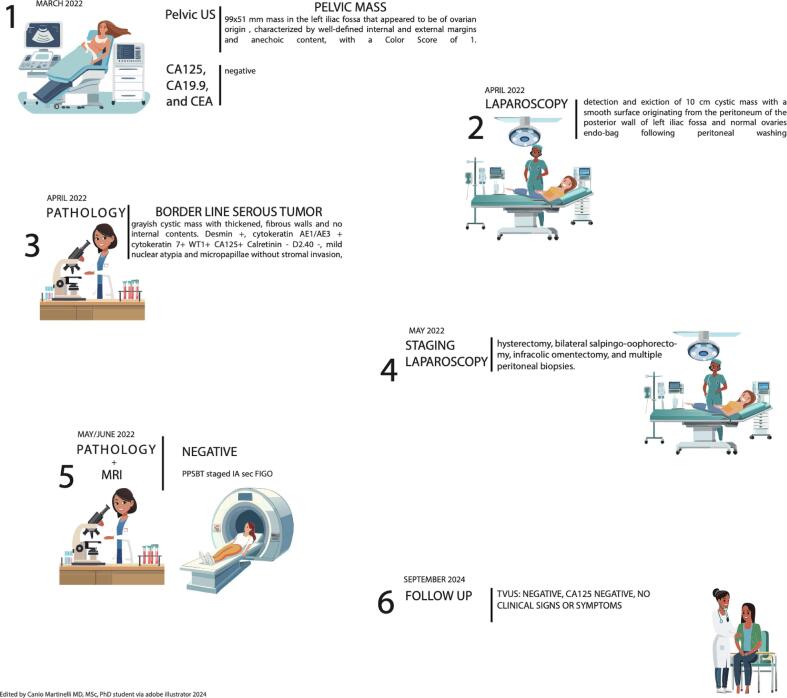

In March 2022, a 51-year-old asymptomatic woman was referred to our department (Unit of Obstetrics and Gynecology, S. Antonio Abate Hospital, Erice, Trapani, Italy) after a routine ultrasound by her primary gynecologist incidentally detected a 10 cm mass in the left iliac fossa that appeared to be of ovarian origin. Her medical history included obesity, smoking, hypertension, and elephantiasis of the lower limbs. She also had a first-degree family history of breast and endometrial cancer, though specific details were not available. Menarche occurred at age 12, with regular menstrual cycles thereafter. Her obstetric history was notable for one spontaneous vaginal delivery and two cesarean sections. She had also previously undergone laparoscopic cholecystectomy and bariatric surgery.

Upon admission, a transvaginal pelvic ultrasound confirmed the diagnosis, revealing a 99x51 mm mass in the left iliac fossa, suggestive of ovarian origin. The ultrasound showed well-defined internal and external margins with anechoic content, and a Color Score of 1, indicating benign features in accordance with the B1 simple rules of the IOTA terminology (Fig. 1) (Timmerman et al., 2008 Jun, Timmerman et al., 2016 Apr, Valentin et al., 2013 Jan, Nunes et al., 2014 Nov, Suryawanshi et al., 2024 Aug 21, Vilendecic et al., 2023). The uterus was enlarged with a heterogeneous appearance, suggestive of uterine fibromatosis, while the right ovarian appeared normal. Tumor markers, including CA125, CA 19.9, and CEA, were negative.

Fig. 1.

(a) Pelvic ultrasound scan showing a 99x51 mm mass in the left iliac fossa that appearing to be of ovarian origin, characterized by well-defined internal and external margins and anechoic content. US: Samsung WS80A. (b) Pelvic ultrasound scan showing the mass with no signs of vascularization on Color Doppler. US: Samsung WS80A.

Given the sonographic features were consistent with a benign ovarian lesion, the patient was counseled preoperatively regarding the possibility of a single-stage surgical management, either cystectomy or monolateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Intraoperative frozen section was not routinely available at our center; moreover, the reliability of frozen section in accurately diagnosing borderline tumors is suboptimal (sensitivity approximately 62–75 %), which can lead to overtreatment or undertreatment, especially in suspected borderline pathology. Therefore, in the absence of any gross features suggestive of malignancy, we elected to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy and excise the mass intact, deferring further definitive procedures until final histopathological results were obtained.

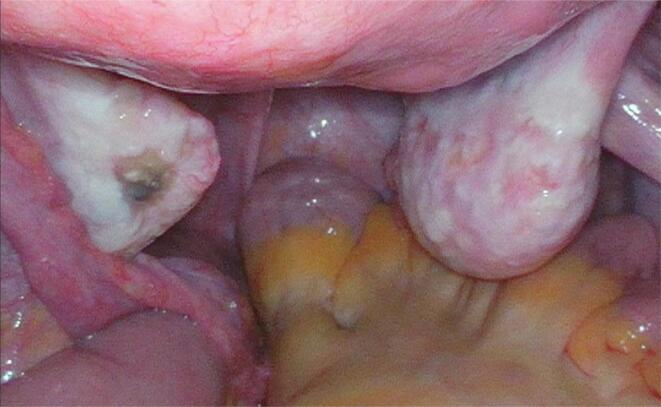

During diagnostic laparoscopy, the intraoperative findings revealed a discrepancy with the preoperative assessment because the 10 cm cystic mass with a smooth surface was discovered to originate from the peritoneum of the posterior wall of the left iliac fossa, rather than the ovary as initially suspected while the uterus and ovaries appeared grossly normal. No other abnormalities were identified in the abdominal or pelvic regions. Therefore the mass was excised intact using an endo-bag following peritoneal washing (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

intraoperative imaging from the first diagnostic laparoscopy revealed normal ovaries and uterus.

Definitive histopathological analysis revealed a grayish cystic mass with thickened, fibrous walls and no internal contents. Microscopic examination demonstrated a cyst wall composed of connective tissue with numerous smooth muscle bundles (Desmin + ) and lined by stratified cylindrical ciliated epithelium (cytokeratin AE1/AE3 + cytokeratin 7 + WT1 + CA125 + Calretinin − D2.40 -), exhibiting mild nuclear atypia and micropapillae without stromal invasion, consistent with primary peritoneal serous borderline tumor. Cytology from peritoneal washing, were negative for malignancy.

Considering the nature of the lesion and the age of the patient, a second laparoscopy was subsequently performed for comprehensive surgical staging, including a hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, infracolic omentectomy, and multiple peritoneal biopsies. All specimens, including those from the uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes, omentum, and peritoneal biopsies were negative for malignancy.

To investigate presence of metastasis, post-operative abdominal and pelvic MRI demonstrated no residual intra-abdominal disease or visceral metastasis, confirming FIGO stage IA PPSBT. The patient’s recovery was uneventful, with no side effects following either surgery. She was discharged in good condition five days post-surgery, having recovered quickly. Ongoing follow-up, including pelvic examinations, transvaginal ultrasounds, and CA-125 testing, has shown no recurrence up to September 2024 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

This timeline illustrates the diagnostic and therapeutic pathway for a patient diagnosed with a borderline serous ovarian tumor between March 2022 and September 2024. (Cortés-Guiral et al., 2021)(1) In March 2022, a pelvic ultrasound identified a well-defined, predominantly anechoic 9 × 5.1 cm (approx.) mass in the left iliac fossa suspicious for ovarian origin; serum tumor markers (CA125, CA19.9, and CEA) were negative. (Dallenbach-Hellweg, 1987 Apr) In April 2022, laparoscopic exploration revealed and resected a smooth-walled 10 cm cystic lesion arising from the peritoneum of the posterior left iliac fossa, while the ovaries appeared normal. (Genadry et al., 1981) Pathological examination confirmed a borderline serous tumor exhibiting thickened fibrous walls, mild nuclear atypia, and micropapillary features without stromal invasion (immunohistochemistry: positive for Desmin, cytokeratins AE1/AE3 and 7, WT1, and CA125; negative for calretinin and D2-40). (Biscotti and Hart, 1992) In May 2022, a second laparoscopic procedure was performed for staging, including total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, infracolic omentectomy, and multiple peritoneal biopsies. (Fox, 1993 Aug) Subsequent MRI and final pathology (May/June 2022) showed no residual disease, and the borderline serous tumor was staged as IA according to FIGO. (Timmerman et al., 2008 Jun) At follow-up in September 2024, transvaginal ultrasound and serum CA125 remained negative, and the patient reported no clinical signs or symptoms.

4. Narrative review

4.1. Historical background

The identification of PPSBT emerged in the mid-20th century, observing atypical epithelial proliferations in the peritoneum that closely resembled serous ovarian tumors. Initially they were termed “atypical endosalpingiosis” (Talia et al., 2019), but these lesions were frequently misclassified due to their overlapping histological features with other peritoneal pathologies, particularly primary ovarian carcinomas. This misclassification often resulted in the application of aggressive treatments designed for malignant conditions, complicating both diagnosis and management (Hutton and Dalton, 2007 Jan). As surgical practices expanded, driven by increased patient access, more frequent procedures, and greater surgeon expertise, the opportunity to encounter and study these tumors grew. Over time, this growing experience, combined with refined histopathological analyses, helped reveal the unique features of PPSBT, allowing us to better distinguish them from more malignant tumors. This growing understanding led to the adoption of the term “Primary Peritoneal Serous Borderline Tumor,” a designation that more accurately reflects the tumor’s borderline malignant potential and primary peritoneal origin (Seidman and Kurman, 2000). The shift in terminology was pivotal, marking PPSBT as a distinct entity reflecting the need of a diagnostic and therapeutic strategies that differs from borderline ovarian tumor and malignant ovarian carcinomas.

4.2. Epidemiology

PPSBT is such an exceptionally rare neoplasm that incidence and prevalence data are primarily derived from case reports and small case series. It accounts for less than 1 % of all serous tumors, including those of both ovarian and peritoneal origins (Pape et al., 2020). Due to its rarity, PPSBT is often discovered incidentally during surgeries. For example, Lin et al. (Lin et al., 2007) reported a case where PPSBT was incidentally found during surgery for adnexal torsion. The low incidence rate, coupled with its frequent incidental discovery, complicates efforts to accurately estimate its true prevalence (Hutton and Dalton, 2007 Jan). The condition predominantly affects women of reproductive age, although it can also occur in postmenopausal women. This demographic pattern aligns with the broader epidemiology of serous borderline tumors (Hauptmann et al., 2016).

4.3. Risk factors

Although PPSBT’s risk factors are not well-defined due to the limited number of documented cases, certain patterns have emerged from the literature. Nulliparity, a history of infertility, and hormonal factors are suspected to be associated with an increased risk of developing PPSBT, similar to what is observed in other gynecological neoplasms (Seidman and Kurman, 2000). Additionally, there is evidence suggesting a possible link with genetic predispositions, particularly BRCA mutations, although these are much more commonly associated with higher-grade serous carcinomas (Vang et al., 2013). Endosalpingiosis, a condition characterized by ectopic benign tubal-type epithelium in the peritoneum, has frequently been associated with PPSBT, potentially indicating a precursor relationship (Talia et al., 2019). Moreover, chronic pelvic inflammation and long-term hormonal exposure are speculated to play a role in the pathogenesis of PPSBT, although environmental factors have not been extensively studied (Seidman and Kurman, 2000).

4.4. Clinical presentation

The elusiveness and rarity of PPSBT are partly due to its nonspecific and often subtle clinical manifestations. In fact, approximately 32 % of PPSBT cases are asymptomatic, and many are incidentally discovered during surgeries performed for unrelated reasons, such as infertility treatments or exploratory laparoscopies, according to Pape et al. (Pape et al., 2020). While when symptomatic, the most commonly reported symptoms include abdominal pain and infertility, with abdominal pain being particularly prevalent as reported also by Bell and Scully (Bell and Scully, 1990). They described 25 cases originally diagnosed as PPSBT in women aged 19 to 53 years, including five postmenopausal patients. Symptomatic cases often presented with infertility or abdominal and pelvic pain, occasionally mimicking chronic pelvic inflammatory disease or small bowel obstruction. In some cases, amenorrhea was also reported. Among the patients, eight had incidental peritoneal lesions discovered during laparotomy performed for unrelated conditions, including benign serous ovarian tumors in five patients, and uterine leiomyomas, ventral hernia, and cesarean section in the remaining three. In 23 of these cases, the tumors appeared as peritoneal adhesions or granularity, while two patients presented with extraovarian masses. In four cases, the lesions extended beyond the pelvis to involve the upper abdominal peritoneum. Additionally, Biscotti and Hart (Biscotti and Hart, 1992) reported on 17 cases of PPSBT in women aged 16 to 67 years. Nine of these cases were incidentally discovered during surgeries for other conditions, including endometriosis, adhesions, or cesarean sections. In the remaining cases, patients presented with chronic pelvic or abdominal pain, with one patient having an adnexal mass, another experiencing small bowel obstruction, and a third presenting with symptoms of endometriosis. In more than half of the cases, the tumors appeared as miliary or granular peritoneal lesions resembling peritoneal carcinomatosis. Other cases involved small peritoneal nodules in three patients, diffuse adhesions in another three, and a solitary pedunculated lesion in one patient. In one case, the tumor presented as a smooth-walled cyst, similar to our case, while another was characterized by an irregular peritoneal surface with blebs. The tumor was diffuse in 13 patients and focal in four, with lesions involving only the pelvis in five patients. In most cases, the lesions extended beyond the pelvis, also involving the upper abdominal peritoneum.

The critical issue is that these symptoms are often too nonspecific to raise immediate suspicion for PPSBT, that is why they are frequently mistaken for more common conditions such as endometriosis or ovarian cysts. Tinelli et al. (Tinelli et al., 2009) reported a case where a 37-year-old woman presenting with acute pelvic pain underwent laparoscopic surgery for suspected endometriosis, only to have PPSBT incidentally diagnosed through histopathological examination of the peritoneal lesions.

Imaging studies, although useful for investigating abdominal and pelvic masses, are not consistently reliable in detecting precisely PPSBT. The first imaging description of PPSBT was offered by Go HS, Hong HS et al. (Go et al., 2012). They described the CT findings of PPSBT in a 62-year-old woman who initially presented with abdominal pain in the right lower quadrant, suspected to be acute appendicitis or diverticulitis. Her medical history included a previous total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for mucinous cystadenoma of the left ovary three years earlier. The CT scan revealed low-attenuation, cyst-like peritoneal lesions, as well as multiple nodular thickenings and plaques. Due to her history of mucinous cystadenoma, the peritoneal lesions were suspected to be pseudomyxoma peritonei from a recurrent mucinous cystic tumor. A laparotomy was performed, and as many peritoneal lesions as possible were removed, including the omentum and appendix and the final pathological diagnosis confirmed PPSBT.

Given its ability to mimic more malignant conditions such as primary ovarian carcinoma, an accurate histopathological diagnosis is mandatory for guiding appropriate management that consist mainly into preventing overtreatment.

4.5. Pathology and histology

PPSBT exhibits distinct histological features that differentiate it from other peritoneal and ovarian neoplasms. Histologically, PPSBT is characterized by non-invasive epithelial proliferations, typically presenting as papillary structures lined by mildly atypical serous epithelium. A key diagnostic feature is the presence of psammoma bodies, concentrically laminated calcified structures (Pape et al., 2020). Immunohistochemically, PPSBT typically expresses epithelial markers such as Ber-EP4 and pancytokeratin, along with hormone receptors like estrogen and progesterone. These markers are instrumental in distinguishing PPSBT from other peritoneal or ovarian tumors, which may have different immunohistochemical profiles (Table 1).

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical and histological features of PPSBT and similar diseases.

| Disease/Condition | Immunohistochemical Markers | Histological Features | Study References |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPSBT (Primary Peritoneal Serous Borderline Tumor) | Ber-EP4, Pancytokeratin, Estrogen Receptor (ER), Progesterone Receptor (PR) | Non-invasive papillary structures, psammoma bodies, mild atypia | Pape et al. (Pape et al., 2020),Go et al. (Go et al., 2012) |

| Primary Peritoneal Serous Carcinoma (PPSC) | WT-1, PAX8, Ber-EP4, Calretinin | Poorly differentiated, invasive growth, high mitotic rate | Kawai et al. (2016); Hou et al. (2012) |

| Ovarian Serous Borderline Tumor (SBT) | CA-125, ER, PR, Ber-EP4, WT-1 | Similar to PPSBT but located in ovaries, non-invasive | Seidman & Kurman (Seidman and Kurman, 2000); Hutton & Dalton (2007) |

| Peritoneal Malignant Mesothelioma (PMM) | Calretinin, CK5/6, WT-1, D2-40 | Diffuse growth, thickened pleura, abundant cytoplasm | Comin et al. (2007); Kawai et al. (2016) |

| Endosalpingiosis | Ber-EP4, ER, PR, Calretinin | Benign inclusions, resembles fallopian tube epithelium | Talia et al. (Talia et al., 2019),Tinelli et al. (Tinelli et al., 2009) |

The pathogenesis of PPSBT remains under investigation, with several theories proposed. One widely supported theory suggests that PPSBT may originate from areas of endosalpingiosis, where benign inclusions undergo proliferative changes, leading to the development of borderline tumors (Talia et al., 2019). Another theory posits that PPSBT, and ovarian serous borderline tumors share a common precursor, with the difference in presentation attributed to the primary site of involvement: peritoneal surface versus ovarian tissue.

4.6. Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with PPSBT is generally favorable, with a high survival rate even in cases of recurrence. Bell and Scully (Bell and Scully, 1990) documented the outcomes of 25 patients over an 8-year follow-up period, during which only four cases of recurrence were noted. Two of these recurrences were histologically confirmed as borderline tumors. In one case, a recurrence occurred in the omentum after a patient had undergone total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, partial omentectomy, and chemotherapy. Another recurrence was identified in the peritoneum and preserved ovary following conservative management with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Both patients remained alive and free of clinical evidence of disease at 1.7 and 2 years, respectively, after resection of the recurrent lesions. A third patient experienced recurrence seven years post-surgery, presenting with a pelvic mass following total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and omentectomy. Exploratory laparotomy revealed multiple disseminated tumor nodules in the intestinal wall and peritoneum, which were histologically confirmed as invasive low-grade serous carcinoma. Despite the recurrence, this patient remained alive 12 years after the initial diagnosis with ongoing intra-abdominal disease following bowel resection, lymph node sampling, and adjuvant chemotherapy. In the fourth recurrence, 7.5 years after initial surgery, a patient developed a lung mass and pleural effusion. Cytology revealed a papillary serous tumor with psammoma bodies, consistent with the original borderline serous peritoneal tumor. Despite treatment with combined chemotherapy, the patient succumbed to disseminated disease two years after the recurrence. Interestingly, eight patients who were treated conservatively with partial resections or peritoneal biopsies did not experience any recurrences, further highlighting the generally indolent nature of PPSBT.

Similarly, Biscotti and Hart (Biscotti and Hart, 1992) reported 14 cases with follow-up data, observing recurrences in only two patients. Both patients developed multiple episodes of intestinal obstruction but remained alive 10.9 and 16.2 years after diagnosis without the need for adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

4.7. Treatments

The treatment of PPSBTs is primarily surgical, with the approach tailored to the patient’s age, desire for fertility preservation, and the extent of the disease. The most common surgical procedure is total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy, aiming for the complete resection of visible lesions (R0 resection) (Pape et al., 2020). However, given the favorable prognosis and low recurrence rates associated with PPSBTs, conservative, fertility-sparing surgery is often considered for younger women, particularly when the disease is confined, and fertility preservation is desired (Hutton and Dalton, 2007 Jan, Pape et al., 2020, Lin et al., 2007).

A systematic review by Pape et al. reported that 32.3 % of cases involved fertility-preserving surgery, while 59.4 % involved more radical procedures. Notably, the recurrence rate remains low, typically below 25 %, regardless of whether complete resection is achieved, supporting the viability of conservative surgical approaches (Pape et al., 2020). Lin et al. and Biscotti et al. also emphasized that even with conservative surgeries, long-term outcomes are generally positive, with limited cases of recurrence or progression to low-grade serous carcinoma (Biscotti and Hart, 1992, Lin et al., 2007).

Adjuvant therapies, such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy have occasionally been employed in cases of incomplete surgical resection or widespread disease, but there is no robust evidence demonstrating a clear survival benefit or significant tumor responsiveness in PPSBT. Consequently, these modalities are generally not recommended for PPSBT, largely because of its good prognosis and typically indolent course (Dallenbach-Hellweg, 1987 Apr, Pape et al., 2020). Any potential benefit must be weighed against the morbidity of chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and at present, no consensus guidelines advocate for routine adjuvant treatment in PPSBT. Hormonal therapy, including GnRH analogues and other antihormonal treatments, has been explored in hormone receptor-positive cases, but this approach remains experimental and is not yet considered standard practice (Hutton and Dalton, 2007 Jan, Pape et al., 2020).

4.8. Follow up

Given the potential for a long disease course, meticulous long-term follow-up is essential for all patients. This involves regular pelvic exams, imaging, and monitoring of tumor markers like CA-125. Overall, treatment strategies should balance oncologic control with the preservation of fertility and quality of life, considering the generally favorable prognosis of PPSBTs (Table 2) (Seidman and Kurman, 2000, Pape et al., 2020, Lin et al., 2007).

Table 2.

Key findings and pitfalls in PPSBT.

| Section | Key Findings | Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|

| Historical Background | PPSBT was historically misclassified as other peritoneal pathologies. Over time, surgical and histopathological advancements helped to distinguish PPSBT as a unique entity. | Early misclassification often led to overtreatment, applying aggressive therapies meant for malignancies. Diagnosis and management were complicated by its overlap with other tumors. |

| Epidemiology | PPSBT is an exceptionally rare neoplasm, accounting for less than 1 % of all serous tumors. It primarily affects women of reproductive age. | Due to its rarity and incidental discovery, accurate prevalence estimates are difficult. The data is primarily based on case reports and small series, lacking large-scale studies. |

| Risk Factors | Nulliparity, infertility, hormonal factors, and possible BRCA mutations have been proposed as risk factors. Endosalpingiosis may be a precursor. | The rarity of documented cases makes it difficult to confirm associations with genetic or environmental factors. Potential risk factors remain poorly defined and speculative. |

| Clinical Presentation | Approximately 32 % of cases are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally. When symptomatic, abdominal pain and infertility are the most common. | Nonspecific symptoms mimic other conditions, such as endometriosis or ovarian cysts, often leading to misdiagnosis. Imaging studies are not always reliable for detecting PPSBT. |

| Pathology and Histology | Histologically characterized by non-invasive epithelial proliferations and psammoma bodies. It shares features with other borderline tumors. | Overlap with other peritoneal or serous tumors complicates histopathological diagnosis, which can lead to inappropriate treatment strategies. |

| Prognosis | Generally favorable prognosis, even in cases of recurrence. Rare cases may progress to low-grade serous carcinoma or distant metastasis. | While recurrences are rare, they can occur years after treatment, making long-term follow-up essential. Rare cases of invasive transformation challenge the typical indolent course of the disease. |

| Treatments | Surgery is the primary treatment, with conservative, fertility-preserving approaches available for younger women. Adjuvant therapy is not always beneficial. | The role of adjuvant therapies remains unclear. While surgery is effective, conservative approaches carry some recurrence risk, and the decision for aggressive treatment should be carefully weighed. |

5. Discussion

PPSBT presents significant diagnostic challenges due to their rarity and the difficulty in distinguishing them from other PSM. PPSBT often mimics ovarian cancer, particularly due to histological similarities to peritoneal “implants” in ovarian serous borderline tumors. This overlap often leads to misdiagnosis, especially when PPSBT presents with nonspecific symptoms such as elevated serum CA-125 levels, abdominal pain, or small bowel obstruction (Fox, 1993 Aug, Biron-Shental et al., 2003). In this context, relying solely on intraoperative findings or frozen sections can lead to overtreatment, particularly in younger women where fertility preservation is critical.

The necessity of histological confirmation is further underscored by the challenge of distinguishing PPSBT from other tumors such as primary ovarian serous borderline tumors with implants or high-grade primary peritoneal carcinoma (Hutton and Dalton, 2007 Jan). Microscopic features like psammoma bodies and the absence of submesothelial invasion help differentiate PPSBT from more aggressive malignancies (Bell and Scully, 1990).

Once diagnosed, PPSBT generally has a favorable prognosis, even in cases of recurrence, supporting a less aggressive approach to treatment. Long-term follow-up is critical, particularly due to the limited data available on PPSBT. The guidelines for borderline ovarian tumors recommend observation rather than adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation, as these treatments have not shown significant benefit in similar tumors (Chambers et al., 1988). This brings forth a discussion on whether the existing treatment framework for ovarian borderline tumors can be applied to PPSBT.

The question of surgical approach is another key issue. While most documented cases of PPSBT have been managed via laparotomy, is this still necessary in light of current evidence? If we consider PPSBT’s similarities to borderline ovarian tumors, laparoscopic treatment has emerged as a safe and effective alternative, particularly when the tumor is removed intact using an endobag. Studies have shown that laparoscopy offers lower complication rates, shorter recovery times, and does not increase recurrence risk compared to laparotomy (Ødegaard et al., 2007, Maneo et al., 2004 Aug, Song et al.,, Bourdel et al.,).

The NCCN and ESMO-ESGO guidelines for borderline ovarian tumors advocate for fertility-sparing surgery through minimally invasive techniques, particularly for younger patients (Colombo et al., 2019 May 1, National,, Tozzi et al., 2004 Apr, Gallotta et al., 2014 Dec, Ghezzi et al., 2012 May). With advancements in laparoscopic procedures, the preservation of fertility and reduction of postoperative complications seem achievable without compromising the oncological outcomes. This raises an important question: Should laparoscopy be more widely adopted in the management of PPSBT, especially considering the generally good prognosis and the benefits of minimally invasive surgery?

Our case report, where a PPSBT patient was successfully treated laparoscopically with no recurrence after two years, supports the feasibility and safety of this approach. As more cases of laparoscopic management are documented, it becomes increasingly clear that this approach may offer significant advantages over laparotomy, particularly in terms of patient recovery and long-term outcomes.

Although the clinical presentation, histologic features, and outcomes of PPSBT largely parallel those of ovarian serous borderline tumors, each entity remains separately classified. This distinction stems from their presumed difference in embryologic origin, peritoneal versus ovarian surface epithelium, and the relative rarity of PPSBT, which limits large-scale prospective data. However, in practice, both PPSBT and ovarian serous borderline tumors are often managed with similar principles: complete surgical resection, consideration of minimally invasive approaches, and fertility preservation when feasible. Merging PPSBT and ovarian serous borderline tumors into a unified category, akin to how high-grade ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal carcinomas are classified together, to reduce clinical confusion and potentially broaden the adoption of fertility-sparing and laparoscopic strategies, could be a possibility. Nevertheless, until more robust evidence or updated consensus guidelines emerge, PPSBT is likely to remain a distinct entity in both pathological and clinical classifications.

Given its rarity and debatable histogenesis, possibly linked to the secondary Müllerian system, PPSBT warrants further investigation. A dedicated global registry could centralize clinical and pathologic data, facilitating more rigorous analyses of disease presentation, treatment outcomes, and molecular pathways. Such efforts would not only aid in developing standardized diagnostic and therapeutic protocols but also help clarify whether PPSBT truly arises from pre-existing endosalpingiosis and identify potential biomarkers or targeted interventions to refine patient management (Genadry et al., 1981, Halperin et al., 2001 Oct).

6. Conclusions

PPSBT is a rare, low-malignant potential neoplasm that develops primarily from the peritoneal epithelium. It shares many histological features with ovarian micropapillary serous carcinomas with invasive implants. However, PPSBT can be diagnosed with certainty when the ovaries are either not involved, or present with benign lesions such as serous cystadenoma.

Clinical and pathological staging with imaging and explorative surgery are currently the only ways to distinguish PPSBT from micropapillary serous carcinomas with invasive implants. Patients affected by PPSBT have a good prognosis, with a reported survival rate of 95 % and very low recurrence rates. Laparoscopic treatment should be considered a viable option. Our case report represents one of the very few documented instances of laparoscopic treatment for PPSBT.

While a case of lung metastasis has been described, we believe it would be prudent to perform comprehensive chest and abdominal CT scans during follow-up for these patients. We also recommend that additional cases like ours be shared to enhance the available knowledge regarding the treatment and follow-up of this neoplasm.

8. Institutional review board statement

Not applicable for review study.

9. Informed consent statement

This manuscript describes a retrospective, descriptive case report that did not involve any experimental interventions or alter the patient’s treatment. All personally identifiable information has been removed, ensuring that the patient cannot be identified. In accordance with Italian data protection regulations (D.Lgs. 196/2003 and GDPR), the patient provided specific written informed consent authorizing the use and publication of her anonymized clinical information. This consent was obtained at the Presidio Ospedaliero S. Antonio Abate di Trapani (Via Cosenza, 82, 91,016 Erice TP, Italy). As this is a single-patient case report with anonymized data, and no additional procedures were performed, separate ethics committee approval was not required.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Vito Iannone: Validation, Project administration, Investigation, Formal analysis. Canio Martinelli: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Patrizia Maiorano: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Roberta Granese: Validation, Formal analysis. Alessia Maria Chiara Scaparra Caronna: Investigation, Formal analysis. Maddalena Borriello: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Luigi Alfano: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. Salvatore Cortellino: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Antonio Giordano: Visualization, Validation, Supervision. Alfredo Ercoli: Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Cortés-Guiral D., Hübner M., Alyami M., et al. Primary and metastatic peritoneal surface malignancies. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2021;7:91. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallenbach-Hellweg G. Atypical endosalpingiosis: a case report with consideration of the differential diagnosis of glandular subperitoneal inclusions. Pathol. Res. Pract. 1987 Apr;182(2):180–182. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(87)80101-2. PMID: 3601792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genadry R., Poliakoff S., Rotmensch J., Rosenshein N.B., Parmley T.H., Woodruff J.D. Primary papillary peritoneal neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58:730–734. N/A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biscotti C.V., Hart W.R. Peritoneal serous micropapillomatosis of low malignant potential (serous borderline tumours of the peritoneum): a clinicopathologic study of 17 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1992;16:467–475. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox H. Primary neoplasia of the female peritoneum. Histopathology. 1993 Aug;23(2):103–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1993.tb00467.x. PMID: 8406381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman D., Testa A.C., Bourne T., Ameye L., Jurkovic D., Van Holsbeke C., Paladini D., Van Calster B., Vergote I., Van Huffel S., Valentin L. Simple ultrasound-based rules for the diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun;31(6):681–690. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365. PMID: 18504770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman D., Van Calster B., Testa A., Savelli L., Fischerova D., Froyman W., Wynants L., Van Holsbeke C., Epstein E., Franchi D., Kaijser J., Czekierdowski A., Guerriero S., Fruscio R., Leone F.P.G., Rossi A., Landolfo C., Vergote I., Bourne T., Valentin L. Predicting the risk of malignancy in adnexal masses based on the simple rules from the international ovarian tumor analysis group. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016 Apr;214(4):424–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.01.007. Epub 2016 Jan 19 PMID: 26800772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin L., Ameye L., Franchi D., Guerriero S., Jurkovic D., Savelli L., Fischerova D., Lissoni A., Van Holsbeke C., Fruscio R., Van Huffel S., Testa A., Timmerman D. Risk of malignancy in unilocular cysts: a study of 1148 adnexal masses classified as unilocular cysts at transvaginal ultrasound and review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2013 Jan;41(1):80–89. doi: 10.1002/uog.12308. Epub 2012 Dec 17 PMID: 23001924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes N., Ambler G., Foo X., Naftalin J., Widschwendter M., Jurkovic D. Use of IOTA simple rules for diagnosis of ovarian cancer: meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2014 Nov;44(5):503–514. doi: 10.1002/uog.13437. Epub 2014 Oct 13 PMID: 24920435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryawanshi S.V., Dwidmuthe K.S., Savalkar S., Bhalerao A. Diagnostic efficacy of ultrasound-based international ovarian tumor analysis simple rules and assessment of the different neoplasias in the adnexa model in malignancy prediction among women with adnexal masses: A systematic review. Cureus. 2024 Aug 21;16(8) doi: 10.7759/cureus.67365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilendecic Z., Radojevic M., Stefanovic K., Dotlic J., Likic Ladjevic I., Dugalic S., Stefanovic A. Accuracy of IOTA simple rules, IOTA ADNEX Model, RMI, and subjective assessment for preoperative adnexal mass evaluation: The experience of a tertiary care referral hospital. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 2023;88(2):116–122. doi: 10.1159/000529355. Epub 2023 Jan 30 PMID: 36716716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talia K.L., Fiorentino L., Scurry J., McCluggage W. A clinicopathologic study and descriptive analysis of “atypical endosalpingiosis.”. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2019;39(3):254–260. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton R.L., Dalton S.R. Primary peritoneal serous borderline tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007 Jan;131(1):138–144. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-138-PPSBT. PMID: 17227115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman J., Kurman R. Ovarian serous borderline tumors: A critical review of the literature with emphasis on prognostic indicators. Hum. Pathol. 2000;31(5):539–557. doi: 10.1053/HP.2000.8048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape J., Samartzis E.P., Choschzick M., et al. Primary peritoneal serous borderline tumors as a therapeutic challenge: a systematic review of the literature. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2020;2:316–326. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00232-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pin-Yao Lin, Shir-Hwa Ueng, Mao-Jung Tseng, Primary Peritoneal Serous Borderline Tumor Presenting as an “Adnexal Torsion” Gynecologic Emergency, Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Volume 46, Issue 3, 2007, Pages 308-310, ISSN 1028-4559, 10.1016/S1028-4559(08)60043-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hauptmann S., Friedrich K., Redline R., Avril S. Ovarian borderline tumors in the 2014 WHO classification: Evolving concepts and diagnostic criteria. Virchows Arch. 2016;470(2):125–142. doi: 10.1007/s00428-016-2040-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vang R., Shih I., Kurman R. Fallopian tube precursors of ovarian low- and high-grade serous neoplasms. Histopathology. 2013;62(1):44–58. doi: 10.1111/his.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell D.A., Scully R.E. Serous borderline tumours of the peritoneum. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:230–239. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199003000-00004. N/A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinelli A, Malvasi A, Pellegrino M. An incidental peritoneal serous borderline tumor during laparoscopy for endometriosis. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2009;30(5):579-82. PMID: 19899422. Doi:N/A. [PubMed]

- Go H., Hong H., Kim J.W., Woo J. CT appearance of primary peritoneal serous borderline tumour: A rare epithelial tumour of the peritoneum. Br. J. Radiol. 2012;85(1009):e22–e25. doi: 10.1259/bjr/26458228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biron-Shental T., Klein Z., Edelstein E., Altaras M., Fishman A. Primary peritoneal borderline tumor. A case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2003;24:96–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers J.T., Merino M.J., Kohorn E.I., Schwartz P.E. Borderline ovarian tumors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:1088–1094. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90419-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ødegaard E., Staff A.C., Langebrekke A., Engh V., Onsrud M. Surgery of borderline tumors of the ovary: retrospective comparison of short-term outcome after laparoscopy or laparotomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(5):620–626. doi: 10.1080/00016340701286934. PMID: 17464594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maneo A., Vignali M., Chiari S., Colombo A., Mangioni C., Landoni F. Are borderline tumors of the ovary safely treated by laparoscopy? Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Aug;94(2):387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.05.003. PMID: 15297177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song T, Kim MK, Jung YW, Yun BS, Seong SJ, Choi CH, Kim TJ, Lee JW, Bae DS, Kim BG. Minimally invasive compared with open surgery in patients with borderline ovarian tumors. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bourdel N, Huchon C, Abdel Wahab C, Azaïs H, Bendifallah S, Bolze PA, Brun JL, Canlorbe G, Chauvet P, Chereau E, Courbiere B, De La Motte Rouge T, Devouassoux-Shisheboran M, Eymerit-Morin C, Fauvet R, Gauroy E, Gauthier T, Grynberg M, Koskas M, Larouzee E, Lecointre L, Levêque J, Margueritte F, Mathieu D'argent E, Nyangoh-Timoh K, Ouldamer L, Raad J, Raimond E, Ramanah R, Rolland L, Rousset P, Rousset-Jablonski C, Thomassin-Naggara I, Uzan C, Zilliox M, Daraï E. Borderline ovarian tumors: Guidelines from the French national college of obstetricians and gynecologists (CNGOF). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Colombo N., Sessa C., du Bois A., Ledermann J., McCluggage W.G., McNeish I., Morice P., Pignata S., Ray-Coquard I., Vergote I., Baert T., Belaroussi I., Dashora A., Olbrecht S., Planchamp F., Querleu D. ESMO-ESGO Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference Working Group. ESMO-ESGO consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: pathology and molecular biology, early and advanced stages, borderline tumours and recurrent disease†. Ann Oncol. 2019 May 1;30(5):672–705. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz062. PMID: 31046081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Ovarian Cancer/Fallopian Tube Cancer/Primary Peritoneal Cancer (Version 3.2024). Accessed on 8/28/2024. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1453.

- Tozzi R., Köhler C., Ferrara A., Schneider A. Laparoscopic treatment of early ovarian cancer: surgical and survival outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Apr;93(1):199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.01.004. PMID: 15047236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallotta V., Ghezzi F., Vizza E., Chiantera V., Ceccaroni M., Franchi M., Fagotti A., Ercoli A., Fanfani F., Parrino C., Uccella S., Corrado G., Scambia G., Ferrandina G. Laparoscopic staging of apparent early stage ovarian cancer: results of a large, retrospective, multi-institutional series. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 Dec;135(3):428–434. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.09.006. Epub 2014 Sep 16 PMID: 25230214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi F., Malzoni M., Vizza E., Cromi A., Perone C., Corrado G., Uccella S., Cosentino F., Mancini E., Franchi M. Laparoscopic staging of early ovarian cancer: results of a multi-institutional cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012 May;19(5):1589–1594. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2138-9. Epub 2011 Nov 16 PMID: 22086443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin R., Zehavi S., Hadas E., Habler L., Bukovsky I., Schneider D. Immunohistochemical comparison of primary peritoneal and primary ovarian serous papillary carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001 Oct;20(4):341–345. doi: 10.1097/00004347-200110000-00005. PMID: 11603217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]