Highlights

-

•

circHIPK2 expression in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) tissues was higher than that in adjacent normal mucosa (ANM) tissues.

-

•

The expression of MCTS1 in LSCC was higher than that in ANM tissues.

-

•

circHIPK2/miR-889–3p/MCTS1/IL-6 axis regulates the malignant progression of LSCC.

-

•

High expression of circHIPK2 may predict the poor prognosis of LSCC.

Keywords: Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma, Non-coding RNA, circHIPK2, miR-889–3p, MCTS1, IL-6, Tumor microenvironment

Abstract

Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) is a common malignant tumor of the head and neck with a poor prognosis. The role of circRNAs in LSCC remains largely unknown. In this study, quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), Sanger sequencing and fluorescence in situ hybridization were undertaken to detect the expression, localization, and clinical significance of circHIPK2 in LSCC tissues and TU686 and TU212 cells. The functions of circHIPK2 in LSCC were explored through proliferation analysis, EdU staining, colony formation assay, wound healing assay, and Transwell assay. The regulatory mechanisms underpinning circHIPK2, miR-889–3p, and MCTS1 were investigated using luciferase assay, Western blotting, and qRT-PCR. We found that LSCC tissues and cells demonstrated high expression of circHIPK2 that was closely associated with the malignant progression and poor prognosis of LSCC. Knockdown of circHIPK2 inhibited the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells in vitro. Mechanistic studies showed that circHIPK2 competitively bound to miR-889–3p, elevated MCTS1 level, promoted IL-6 secretion, and ultimately accelerated the malignant progression of LSCC. In conclusion, an axis involving circHIPK2, miR-889–3p, MCTS1 and IL-6 regulates the malignant progression of LSCC. circHIPK2 expression may serve as a novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for LSCC.

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) originates from the mucous epithelium of the mouth, pharynx or larynx [1]. Laryngeal cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors of the head and neck, and 85–96 % of cases are diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma [2], with high morbidity and mortality rates [3,4]. Surgical resection, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are effective to cope with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) [2,5], but leaves a 5-year survival rate of only 64 %, because it has already progressed to an advanced stage in about two-thirds of patients at diagnosis [3]. Therefore, it is of great clinical significance to explore novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for LSCC.

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are a group of single-stranded, covalently closed non-coding RNAs produced by the backsplicing of precursor mRNAs. circRNAs are characterized by their tissue specificity, sequence conservation, and structural stability, which facilitates their stable expression in blood, urine, plasma, and even exosomes [6,7]. circRNAs serve as transcriptional regulators, miRNA sponges, or protein binders in cancer progression [[8], [9], [10]]. In addition, circRNAs are clearly associated with clinical features of cancers, advocating their diagnostic and prognostic values [[11], [12], [13]]. Recent studies have shown that circRNAs, rich in miRNA-binding sites, can bind to miRNAs specifically to eliminate the inhibitory effect of miRNAs on target genes and upregulate the expression of target genes, indicating that circRNAs can act as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) [14]. circRNA plays a critical role in modulating the cell cycle [15], apoptosis [16], proliferation [17], invasion, and metastasis [18] of HNSCC, as well as immune escape [19], angiogenesis [20], tumor resistance [21], and the tumor microenvironment (TME) [22]. In our previous studies, we found that circHIPK2 can promote the malignant progression of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by decreasing the expression of parental gene HIPK2 and regulating the wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [23].

Malignant T-cell-amplified sequence 1 (MCTS1), also known as MCT-1, is oncogenic and up-regulated in T-cell lymphoma [24]. A growing body of data suggest that MCTS1 can be targeted to promote genomic instability and tumorigenesis [[25], [26], [27]]. Studies have found that MCTS1 is closely related to the TME; for example, one study has shown that the CD147-MCTS1 complex regulates glucose metabolism in the TME [28]. Another study found that MCTS1 activates the IL-6/IL-6R/Stat3 pathway, promotes M2 macrophage polarization, enhances cell stemness, and thus contributes to the progression of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [27]. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) within the TME play a pivotal role in the progression of LSCC. CAFs secrete a range of growth factors, including EGF and VEGF, as well as cytokines such as IL-6, which collectively promote tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis, immunosuppression, and the recruitment of immune cells [29]. Moreover, CAFs serve as the primary source of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in the TME, contributing to the degradation and remodeling of the extracellular matrix, thereby further stimulating tumor metastasis, angiogenesis, and immunosuppression [30]. Elevated levels of MMP2, MMP9, and MMP13 in LSCC have been associated with invasion, metastasis, and poor prognosis [31,32]. Within tumor cells, messenger molecules secreted by CAFs affect tumor growth, metastasis, and the induction of EMT [33], which is closely linked to the metastatic behavior of LSCC [34].

Study have shown that MCTS1 may be an oncogene for LSCC. It has been found that MCTS1 can interact with proliferation-related protein PA2G4-P48 and prolong its half-life by reducing its polyubiquitination, thereby promoting cell proliferation in HNSCC [35]. However, no relevant studies have been conducted to unravel how circRNAs and MCTS1 interact to govern the development of HNSCC.

In this study, we profiled the expression of circHIPK2 in 24 pairs of LSCC tissues and matched adjacent normal mucosa (ANM) tissues, finding that circHIPK2 expression was abnormally up-regulated in LSCC tissues. In addition, the expression of circHIPK2 was closely related to the clinical characteristics and prognosis of patients with LSCC. In the mechanistical study, we found that circHIPK2 can bind to miR-889–3p to overexpress MCTS1, thereby stimulating the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells.

Materials and methods

LSCC tissues

A total of 24 pairs of LSCC tissues and matched ANM tissues (at 1–3 cm to the edge of cancer) were obtained from patients undergoing surgery at the Affiliated BenQ Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. None patients received chemotherapy or radiotherapy before surgery. The tissue samples were independently diagnosed by two experienced clinical pathologists. Histological types of LSCC were determined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) system, and TNM (Tumor, Node, Metastasis) stage was defined according to the criteria of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC, 8th edition). Fresh specimens were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Affiliated BenQ Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (No. 2024-KL001). Written informed-consent was obtained from each subject prior to recruitment in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cell lines and cell culture

Human LSCC cell lines TU686 and TU212 were purchased from JH-BIO (Shanghai, China) and Fenghbio (Hunan, China). The medium RPMI1640 (Servicebio, Hubei, China) was added with 10 % FBS (TRANSGEN BIO TECH, Beijing, China), and cultured in an incubator at 37 °C and 5 % CO2.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from tissues or cells using the RNAeasy™ Animal RNA Extraction Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA was synthesized using BeyoRT™ II First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (RNase H-) (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

qRT-PCR was performed on an ABI QuantStudio3 instrument using BeyoFast SYBR Green qPCR Mix (2X, High ROX) (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The relative expression levels were calculated by the 2(−△△CT) method. Primers used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Cy3-labeled circHIPK2 probes (5′-GGCCATACCTGTAATATCTGGACTG-3′) and FAM-labeled miR-889–3p (5′-ACAATGGTTGTCCGATATTAA-3′) were synthesized by the Gemma (Shanghai, China). FISH kit was used for FISH (Gemma, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Images were acquired under a fluorescence microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, United States).

Plasmid construction and cell transfection

circHIPK2 overexpression plasmids were generated by lentiviral vector (Bioword Bio, MN, United States). To construct luciferase reporter plasmids, the sequences of wild-type circHIPK2, miR-889–3p binding site mutated circHIPK2, wild-type MCTS1 3′UTR, and miR-889–3p binding site mutated MCTS1 3′UTR were cloned into the GP-miRGLO vector (Gemma, Shanghai, China), respectively. Cell transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, United States) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

siRNAs and miR-889–3p inhibitor

siRNA-targeting circHIPK2 sicircHIPK2 (5′-GUCCAGAUAUUACAGGUAUTT-3′) and negative control (siCtrl) were synthesized by Bioword Bio (MN, United States). miR-889–3p inhibitor and NC, siRNAs-targeting MCTS1 (si-MCTS1: sense: 5′-GGGUAUUAAGAAUCAAUUGTT-3′, antisense: 5′-CAAUUGAUUCUUAAUACCCTT-3′) were synthesized by Gemma (Shanghai, China).

CCK8 assay

After a 24h transfection, cells were digested and seeded into 96-well plates (2 × 103/well). At 0, 24, 48, and 72 h after seeding, each well was replaced with 100 μL of fresh complete medium and 10 μL of TransDetect CCK (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), followed by incubation at 37 °C with 5 % CO2 for 1.5 h. The absorbance of the solution was measured at 450 nm using a Molecular Device (San Jose, CA, United States).

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) staining

EdU staining was conducted using EdU-488 Cell Proliferation Detection Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Cells were incubated with RPMI1640 medium containing 50 μM EdU at 37 °C with 5 % CO2 for 2 h. Having been washed with washing liquid for 3 times, the cells were fixed with 100 μL of immunostaining fixing solution at room temperature for 15 min, washed with washing liquid for 3 times, supplemented with 100 μL of immunostaining strong permeable solution, and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Then, the permeable liquid was removed, and the cells were washed twice with 1 mL of washing liquid per well. Afterward, 0.5 mL of Click reaction solution was added to each well, allowing an incubation at room temperature for 30 min away from light. Click reaction liquid was removed, and the cells were washed with washing liquid for 3 times. Next, 100 μL of Hoechst 33,342 was added and incubated for another 10 min away from light. The cells were photographed with an inverted fluorescent microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, United States).

Colony formation assay

The transfected cells were inoculated into a 6-well plate at a density of 600 cells/well, and then cultured for 10 d. Cells were washed with PBS once. Colonies were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature, and stained with 0.1 % crystal violet solution for 15 min at room temperature, followed by image capture.

Transwell migration assay

After a 24h transfection, cells were digested, washed twice with PBS and resuspended in serum-free RPMI1640. Serum-free medium (200 μL) was added to the upper chamber to a density of 5 × 104 cells/well. Then, 600 μL of RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 20 % FBS was added to the lower chamber. After 24 h, the cells in the upper chamber were gently removed with cotton swabs and the lower side of the chamber was washed for 3 times with PBS, fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 20 min, and stained with 0.1 % crystal violet for 10 min at room temperature. Images were captured.

Prediction of RNA interaction

circHIPK2-binding miRNA was predicted using the CircInteractome program (https://circinteractome.nia.nih.gov/). Targetscan human7.2 (https://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/) and miRDB (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/databasecommons/database/id/20 were used to predict the potential binding target genes of miR-889–3p. Survival differential genes of HNSCC were investigated using GEPIA (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/detail.php) database.

Luciferase reporter assay

HEK293T cells were co-transfected with luciferase reporter plasmids and miR-889–3p mimics or NC mimics for 48 h. The luciferase activity was measured using a dual luciferase reporter assay system (Gemma, Shanghai, China) on a multifunctional Molecular Device (BioTek, VT, United States). The luciferase values were normalized and then the relative luciferase activity was calculated.

Xenograft tumorigenesis

Ten SPF-grade male BALB/C nude mice (6–8 weeks) were purchased from Nanjing Medical University Laboratory Animal Center and housed under SPF conditions. Animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanjing Medical University (No. IACUC-2310,097). Every 6 × 106 TU686 cells were suspended in 100 μL of serum-free RPMI1640 and subcutaneously injected into the right axilla of each mouse. The tumor volume was measured from 7 d after injection. The tumor size was measured with a caliper twice a week, and tumor volume was calculated as follows: V (volume) = (length × width2)/2. After 33 d, the mice were killed and the tumors were dissected and weighed.

Western blotting

Protease inhibitor, phosphatase inhibitor (MCE, NJ, United States) and PMSF (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) were added to RIPA lysate in a ratio of 1:100 to extract protein. The protein was isolated with 12 % SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. After blocking the membrane with skim milk to remove background, the membranes were incubated with antibodies against [MCTS1 (1:1000), E-cadherin (1:1000), N-cadherin (1:1000), Vimentin (1:5000), Occludin (1:1000), MMP9 (1:1000), and GAPDH (1:5000) (ABclonal, Hubei, China)] overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with the secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Protein images were captured using the Tanon 5200 Chemiluminescence Imaging System (Tanon, Shanghai, China), and the images were analyzed using ImageJ software version 1.49 (NIH, MD, United States).

ELISA assay

The concentration of cell supernatant IL-6 was determined using Human IL-6 ELISA Kit (ABclonal, Hubei, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The absorbance of the solution was measured at 450 nm using a Molecular Device (San Jose, CA, United States).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad, CA, United States). Comparisons between two groups were performed using the two-tailed Student's t-test. Correlations were analyzed by Pearson's correlation. Chi-square test was used to evaluate the correlation between circHIPK2 and clinicopathological features. Results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). P values of < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

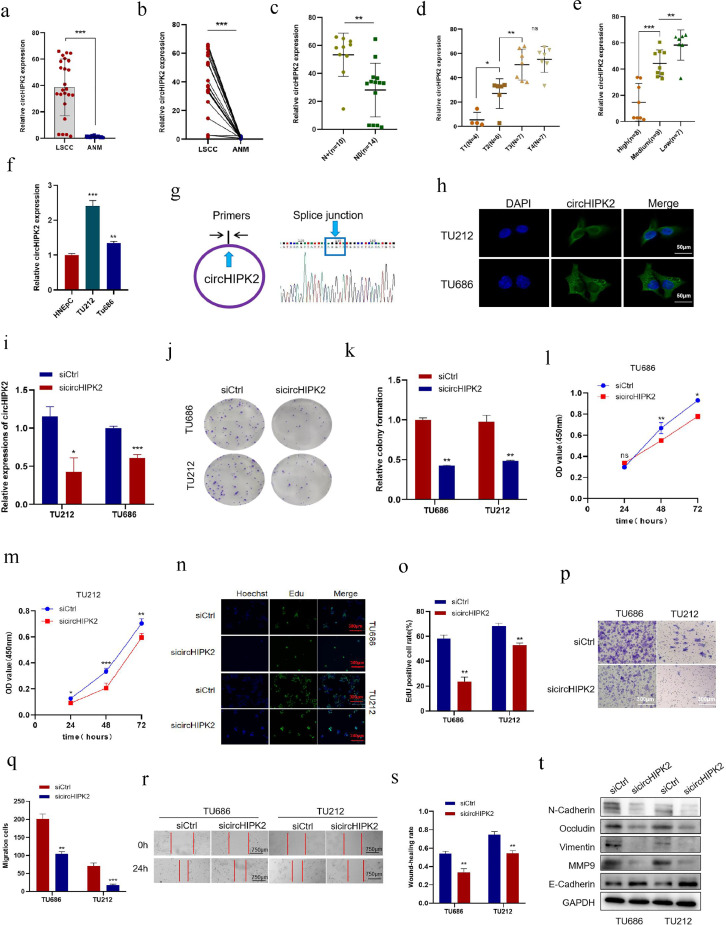

Expression profiles of circHIPK2 in LSCC tissues and cells

In our previous work, we have demonstrated that the level of circHIPK2 increases in nasopharyngeal carcinoma tissues and cell lines. Here, we detected the expression of circHIPK2 in 24 pairs of LSCC and ANM tissues by qRT-PCR. circHIPK2 expression in >85 % of LSCC tissues was significantly higher than that in ANM tissues (Fig. 1a and b). In addition, circHIPK2 expression level was associated with TNM stage. Patients in an advanced stage or with lymph node metastasis had a high expression level of circHIPK2. It is worth noting that the expression level of circHIPK2 gradually increased from T1 to T3 (Fig. 1c and d). The expression of circHIPK2 in poorly differentiated LSCC tissues was higher than that in highly differentiated LSCC tissues (Fig. 1e). However, circHIPK2 expression was not significantly associated with age in LSCC patients (P > 0.05) (Supplementary Table 2). Moreover, qRT-PCR showed that the expression levels of circHIPK2 in LSCC cell lines TU686 and TU212 were significantly higher than those in normal nasal epithelial cell line HNEpC (Fig. 1f). Taken together, an up-regulation of circHIPK2 was closely related to a high malignancy of LSCC, suggesting that circHIPK2 might play a role in promoting tumor progression in LSCC.

Fig. 1.

Expression profiles of circHIPK2 in LSCC tissues and cells, knockdown circHIPK2 inhibits the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells. a, b: circHIPK2 expression levels in 24 pairs of LSCC and ANM samples were detected by qRT-PCR. c-e: Correlation analysis between circHIPK2 expression level and LSCC clinical parameters. High circHIPK2 expression was significantly correlated with N stage (c), T stage (d), and pathological differentiation (e). f: Expression levels of circHIPK2 in normal control HNEpC cells and LSCC cells TU686 and TU212 were detected by qRT-PCR. g: The splicing site of circHIPK2 was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. h: The localization of circHIPK2 in TU686 and TU212 cells was determined by FISH method with the scale = 50 μm. i: circHIPK2 siRNA was transfected into TU212 and TU686 cells, and the expression level of circHIPK2 was detected by qRT-PCR. j, k: circHIPK2 knockdown inhibited colony-forming abilities of TU212 and TU686 cells. l, m: sicircHIPK2 was transfected into TU212 and TU686 cells, and the cell proliferation capacity was detected by CCK8 at a specified time point. n, o: Cell proliferation after circHIPK2 knockdown was detected by EdU staining. p, q: Knocking down circHIPK2 inhibited TU212 and TU686 migration. r, s: Wound healing time of TU212 and TU686 cells after circHIPK2 knockdown was detected. t: After knocking down circHIPK2, the expression levels of migration marker proteins were detected by Western blotting. *P < 0.05, ⁎⁎P < 0.01,⁎⁎⁎P < 0.001.

The reverse splicing sites circular structure of circHIPK2 was verified by RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing (Fig. 1g). In addition, FISH showed that circHIPK2 was mainly localized in the cytoplasm of TU212 and TU686 cells (Fig. 1h).

circHIPK2 promotes the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells

The high expression of circHIPK2 in LSCC tissues indicates that circHIPK2 may exert a tumorigenic effect in LSCC cells. We transfected TU212 and TU686 cells with circHIPK2 overexpression plasmids and siRNAs, respectively, to observe the biological phenotypic changes of LSCC cells. After LSCC cell lines TU212 and TU686 were transfected with siRNAs, qRT-PCR showed that siRNAs significantly knocked down the expression of circHIPK2 (Fig. 1i). Then, we examined the proliferation and migration of TU212 and TU686 cells transfected with sicircHIPK2. Colony formation assay exhibited that knockdown of circHIPK2 decreased the clonogenic capacity of LSCC cells (Fig. 1j, k). CCK8 analysis showed that the viability of TU212 and TU686 cells decreased after circHIPK2 knockdown (Fig. 1l, m). EdU staining showed weaker proliferation of LSCC cells after circHIPK2 knockdown (Fig. 1n, o). Wound healing and migration assays revealed that circHIPK2 knockdown significantly decreased the ability of TU212 and TU686 cells to migrate (Fig. 1p-s). Western blotting disclosed that circHIPK2 knockdown decreased the expression of migration-related proteins in TU212 and TU686 cells (Fig. 1t). These results indicated that circHIPK2, as an oncogene, could promote the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells.

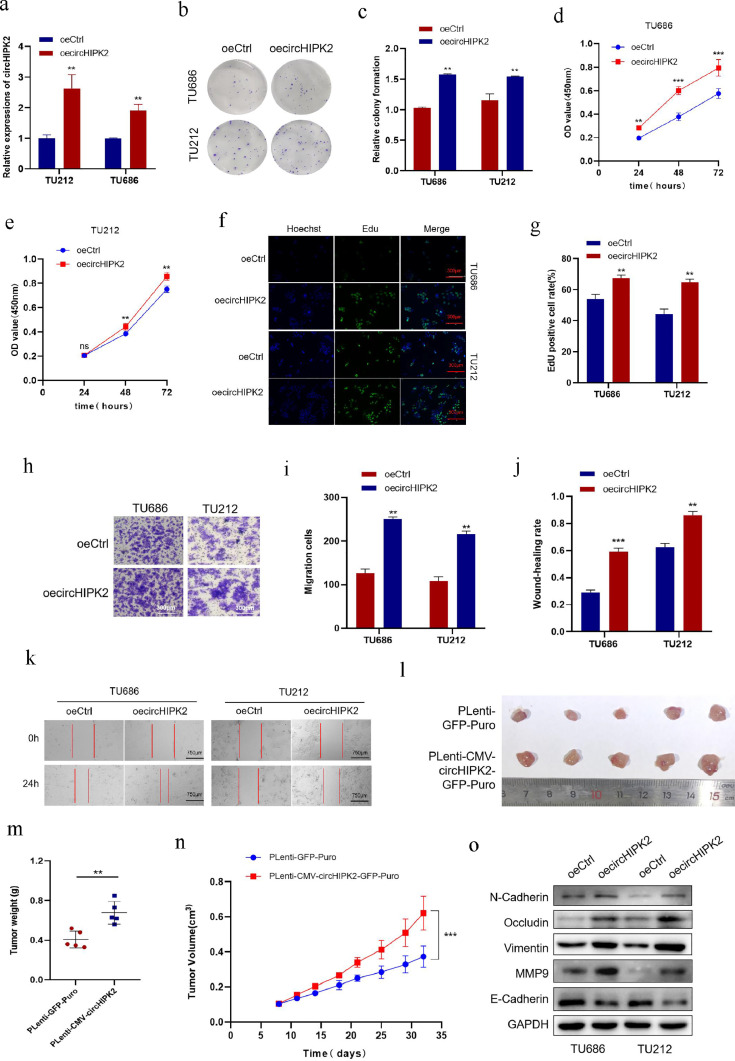

At the same time, we constructed circHIPK2 overexpression plasmids, and qRT-PCR detected that the expression level of circHIPK2 was significantly increased after transfection with circHIPK2 overexpression plasmids (Fig. 2a). We performed the same functional experiments on TU212 and TU686 cells overexpressing circHIPK2. Contrary results from circHIPK2 knockdown were noticed. Colony formation assay showed that circHIPK2 overexpression increased cell clonogenic ability (Fig. 2b, c). CCK8 assay showed that the activity of LSCC cells increased after circHIPK2 overexpression (Fig. 2d, e). EdU experiment showed that the proliferation of LSCC cells increased after circHIPK2 overexpression (Fig. 2f, g). Wound healing and Transwell migration assays showed that circHIPK2 overexpression significantly improved the ability of TU212 and TU686 cells to migrate (Fig. 2h-k). Western blotting results showed circHIPK2 overexpression increased the expression of migration markers of TU212 and TU686 cells (Fig. 2o).

Fig. 2.

Overexpression of circHIPK2 promotes the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells. a: circHIPK2 overexpression plasmids were transfected into TU212 and TU686 cells, and the expression level of circHIPK2 was detected by qRT-PCR. b, c: Overexpression of circHIPK2 promoted colony-forming abilities of TU212 and TU686 cells. d, e: circHIPK2 was overexpressed, and cell proliferation was detected by CCK8 at a specified time point. f, g: Cell proliferation after circHIPK2 overexpression was detected by EdU staining. h, i: Overexpression of circHIPK2 improved the migration ability of TU212 and TU686 cells. j, k: Wound healing time of TU212 and TU686 cells after circHIPK2 overexpression was detected. l: In vivo experiment, a subcutaneous tumor formation model of nude mice was constructed with circHIPK2 overexpression and control cells. m, n: Comparison of tumor weight and volume between circHIPK2 overexpression and control cells. o: After circHIPK2 overexpression, the expression levels of migration marker proteins were detected by Western blotting. *P < 0.05, ⁎⁎P < 0.01,⁎⁎⁎P < 0.001.

Next, we successfully constructed pLenti-CMV-circHIPK2-GFP-Puro lentiviral vector as well as stably overexpressed circHIPK2 in TU686 cell line for in vivo experiments. The results showed that the volume and weight of subcutaneous tumor in the circHIPK2 overexpression plasmids group were larger than those in the control group (Fig. 2l-n). These results further suggested that circHIPK2 could promote the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells. Above, we demonstrate that circHIPK2 is highly expressed in LSCC tissues and cells. It remodels the TME by facilitating the EMT process and the expression of tight junction-related proteins, thereby promoting cell proliferation and migration.

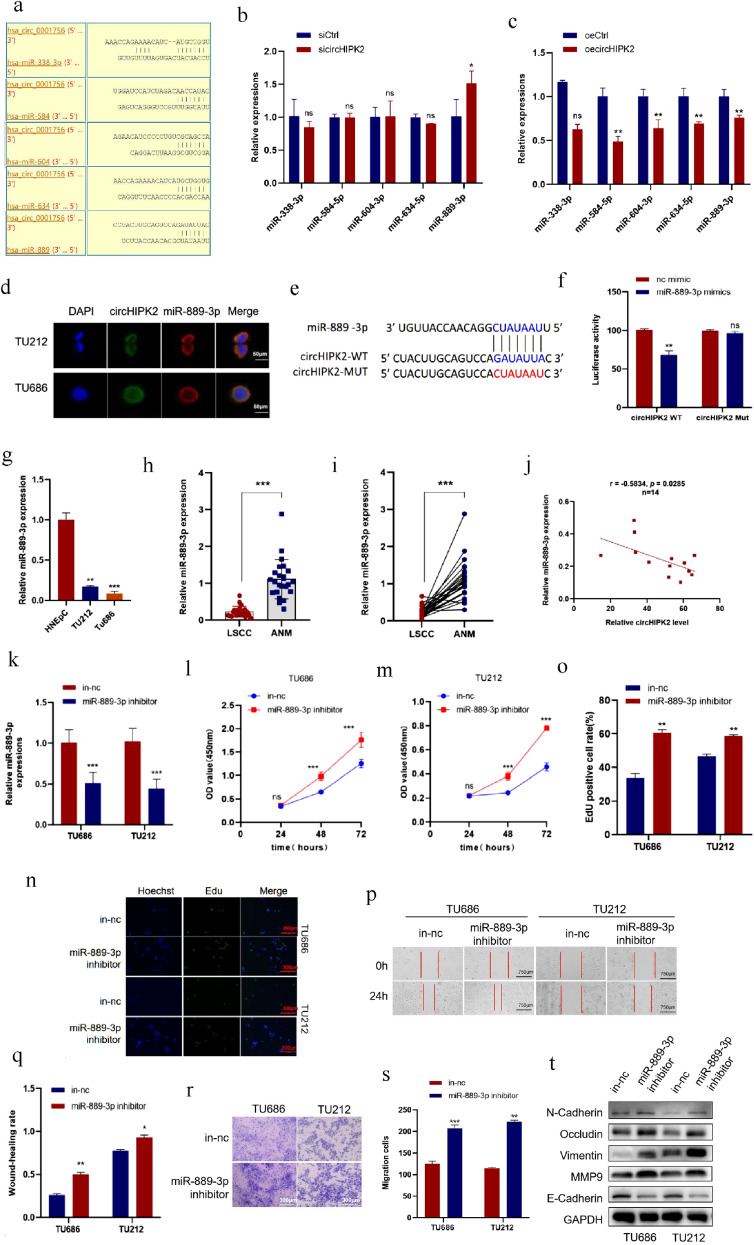

circHIPK2 acts as a miRNA sponge of miR-889–3p and the expression of miR-889–3p was down-regulated in LSCC tissues and cells

Studies have found that circRNAs can function as miRNA sponges to competitively bind to miRNAs, thereby abrogating the inhibitory effect of miRNAs on downstream target genes. Since circHIPK2 is distributed in the cytoplasm, we studied whether it functions as a miRNA sponge in LSCC cells. Using Circinteractome (https://circinteractome.irp.nia.nih.gov/) to predict potential circHIPK2-targeting miRNAs, we selected the top 5 miRNAs with the highest score according to context+ score percentile, including has-miR-889, has-miR-338–3p, has-miR-584, has-miR-604, and has-miR-634 (Fig. 3a). qRT-PCR results showed that only miR-889–3p expression was significantly decreased after circHIPK2 overexpression, whereas circHIPK2 knockdown increased miR-889–3p expression in TU686 cells (Fig. 3b, c). Next, we investigated whether circHIPK2 interacts with miR-889–3p. FISH assay found that circHIPK2 and miR-889–3p co-localized in TU686 and TU212 cells (Fig. 3d). circHIPK2 luciferase reporter plasmids were constructed with wild-type (circHIPK2-WT) or mutant (circHIPK2-Mut) miR-889–3p binding sites (Fig. 3e). We observed that the luciferase activity was obviously decreased in cells co-transfected with miR-889–3p mimics and circHIPK2-WT, but not in those con-transfected with circHIPK2-Mut (Fig. 3f). These data suggested that circHIPK2 served as a sponge for miR-889–3p. qRT-PCR showed that the expression of miR-889–3p in LSCC cells was lower than that in normal nasal epithelial cell line HNEpC (Fig. 3 g), and the expression of miR-889–3p in LSCC tissue was also lower than that in ANM tissues (Fig. 3h, i). In addition, Pearson correlation analysis showed that the expression level of miR-889–3p in 14 pairs of LSCC tissues was negatively correlated with the expression of circHIPK2 (Fig. 3j).

Fig. 3.

circHIPK2 acts as a miRNA sponge for miR-889–3p in LSCC cells and miR-889–3p inhibits the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells. a: Bioinformatic analysis was used to predict the potential miRNAs targeted by circHIPK2. b: circHIPK2 was knocked down and the enrichment of miRNAs was detected by qRT-PCR. c: circHIPK2 was overexpressed, and miRNAs enrichment was detected by qRT-PCR. d: The localization of circHIPK2 and miR-889–3p in TU212 and TU686 cells was detected by FISH assay with the scale = 50 μm. e, f: HEK293T cells were co-transfected with miR-889–3p mimics and wild-type or mutant circHIPK2 luciferase reporter vectors to detect luciferase reporter activity. g: The expression levels of miR-889–3p in HNEpC cells and LSCC TU212 and TU686 cells were detected by qRT-PCR. h, i: The expression level of miR-889–3p in 24 pairs of LSCC and ANM samples was detected by qRT-PCR. j: The expression level of circHIPK2 in 14-pair LSCC tissues was negatively correlated with that of miR-889–3p. k: TU212 and TU686 cells were transfected with miR-889–3p inhibitor, and the expression level of miR-889–3p was detected by qRT-PCR. l, m: The expression of miR-889–3p was inhibited, and cell viability was detected by CCK8 at a specified time point. n, o: Cell proliferation after inhibition of miR-889–3p were detected by EdU staining. p, q: Wound healing time of TU212 and TU686 cells after miR-889–3p inhibition was detected. r, s: After inhibiting miR-889–3p, the migrative ability of TU212 and TU686 cells was improved. t: After miR-889–3p was inhibited, the expression levels of migration marker proteins were detected by Western blotting. *P < 0.05, ⁎⁎P < 0.01,⁎⁎⁎P < 0.001.

miR-889–3p inhibits the malignant differentiation of LSCC cells

The above results suggest that miR-889–3p may play an important role in LSCC. Therefore, we investigated the functions of miR-889–3p in LSCC cells. TU686 and TU212 cells were transfected with miR-889–3p inhibitor or inhibitor negative control (in-nc), then the transfection efficiency was verified by qRT-PCR, which revealed that miR-889–3p expression in TU686 and TU212 cells was suppressed (Fig. 3k). CCK8 assay (Fig. 3l, m) and EdU staining (Fig. 3n, o) indicated that the proliferation of TU686 and TU212 cells decreased after inhibition on miR-889–3p. Wound healing assay showed that downregulation of miR-889–3p accelerated wound healing in LSCC cells (Fig. 3p, q). Transwell assay showed that the migration of LSCC cells was significantly potentiated after inhibiting miR-889–3p (Fig. 3r, s). Western blotting assay showed that the expression of TU686 and TU212 cells migration markers increased after miR-889–3p was inhibited (Fig. 3t). In summary, these data suggested that miR-889–3p inhibited the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells.

miR-889–3p reverses the tumor-promoting effects of circHIPK2 in LSCC cells

To identify whether circHIPK2 promotes LSCC cell proliferation and migration by interacting with miR-889–3p, we conducted a rescue experiment. TU686 cell was co-transfected with sicircHIPK2 and miR-889–3p inhibitor (Fig. 4a). CCK8 and colony formation assays showed that when miR-889–3p was inhibited with miRNA inhibitor, the proliferative and colony-forming ability of LSCC cells was significantly enhanced (Fig. 4b-d). Apparently, transfection with miR-889–3p inhibitor reversed the cell viability having been decreased by circHIPK2 (Fig. 4b-d). Wound healing and Transwell assays showed that miR-889–3p inhibition reversed the migratory abilities of TU686 cells having been weakened by circHIPK2 knockdown (Fig. 4e-h). Taken together, these results indicated that circHIPK2 promoted the malignant progression of LSCC cells mainly by abolishing the antitumor effect of miR-889-3p.

Fig. 4.

miR-889–3p reverses the tumor-promoting effects of circHIPK2 on LSCC cells. a: TU686 cells were transfected with sicircHIPK2 or co-transfected with sicircHIPK2 and miR-889–3p inhibitors. circHIPK2 and miR-889–3p expression was detected by qRT-PCR. b: TU686 cell was transfected with sicircHIPK2 or co-transfected with sicircHIPK2 and miR-889–3p inhibitor. Cell proliferation was determined by CCK8 assay. c, d: Colony formation assay was performed to evaluate the proliferative ability of TU686 cell transfected with sicircHIPK2 or co-transfected with sicircHIPK2 and miR-889–3p inhibitor. e, f: Effects of sicircHIPK2 and miR-889–3p inhibitor on the migration of TU686 cells was evaluated by Transwell migration assays. g, h: TU686 cells were transfected with sicircHIPK2 or co-transfected with sicircHIPK2 and miR-889–3p inhibitor. Cell wound healing time was determined. *P < 0.05, ⁎⁎P < 0.01,⁎⁎⁎P < 0.001.

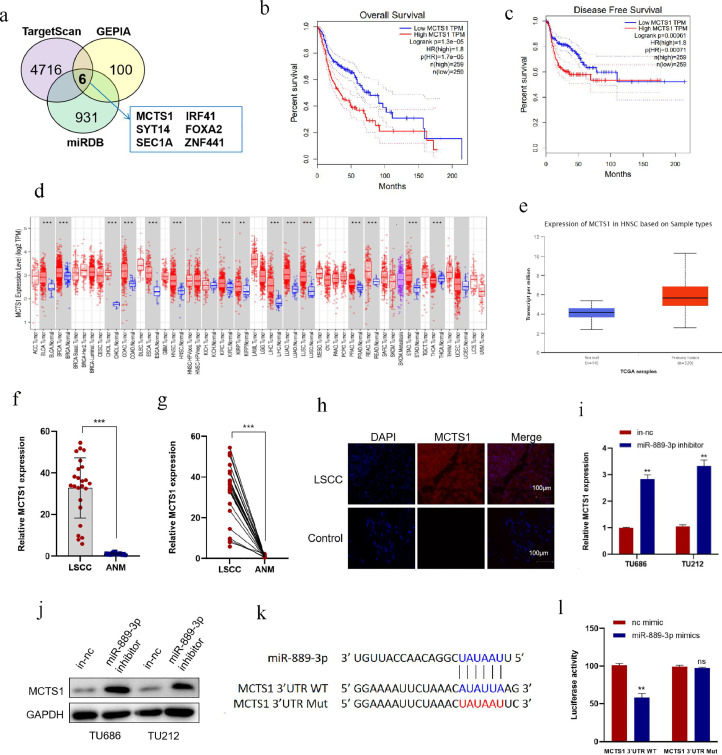

MCTS1 is a direct target of miR-889–3p and is highly expressed in LSCC

The function of miRNA is mainly to cause the degradation or translation inhibition of target genes by binding to target genes, so as to regulate the post-transcriptional expression of genes [36]. However, the target genes of miR-889–3p are still unclear. Therefore, we predicted the target of miR-889–3p by miRDB (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/databasecommons/database/id/20) and TargetScan (https://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/). A total of 869 overlapped genes were obtained from these two online tools, and then mapped with 100 genes related with HNSCC survival in the GEPIA database (Tumor group, 519; Normal group, 44). Finally, 6 genes were obtained (Fig. 5a). According to the GEPIA analysis, a high level of MCTS1 had adverse prognostic effects on both overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) of HNSCC (Fig. 5b, c). Therefore, MCTS1 was chosen for analyses based on the UALCAN database. The results showed that MCTS1 expression elevated in most tumors, including HNSCC (Fig. 5d, e). qRT-PCR indicated that the expression of MCTS1 in LSCC tissues was significantly higher than that in ANM tissues (Fig. 5f, g). Immunofluorescence assay showed that the expression of MCTS1 in LSCC was significantly higher than that in the control group by (Fig. 5h). In addition, downregulation of miR-889–3p significantly increased the expression of MCTS1 at mRNA and protein levels in TU686 and TU212 cells (Fig. 5i, j).

Fig. 5.

MCTS1 is a direct target of miR-889–3p and highly expressed in LSCC. a: Bioinformatic analysis to predict the target genes of miR-889–3p based on miRDB and TargetScan, then mapped with HNSCC survival in the GEPIA database. b, c: The relationship between MCTS1 expression and prognosis of HNSCC was analyzed by GEPIA. d: The expression level of MCTS1 in pancarcinoma in TCGA database was analyzed by UNLCAN. e: The expression level of MCTS1 in HNSCC in TCGA database was analyzed by UNLCAN. f, g: The expression of MCTS1 in LSCC and ANM was detected by qRT-PCR. h: Tissue immunofluorescence assay was used to detect the expression of MCTS1 in LSCC and negative control. i, j: After transfecting miR-889–3p inhibitor with TU212 and TU686 cells, the mRNA and protein levels of MCTS1 were detected by qRT-PCR and Western blotting. k, l: miR-889–3p mimics and MCTS1 3′UTR WT or Mut luciferase reporter plasmids were co-transfected into HEK293T cells to detect luciferase activity. *P < 0.05, ⁎⁎P < 0.01,⁎⁎⁎P < 0.001.

To demonstrate that miR-889–3p interacts directly with the 3′ UTR of MCTS1, we constructed wild-type (WT) MCTS1 3′ UTR and miR-889–3p binding-site mutant (Mut) luciferase reporter plasmids. The WT and Mut reporter vectors were co-transfected with miR-889–3p mimics in cells. Luciferase reporter assay showed that miR-889–3p mimics significantly decreased the luciferase activity of WT, while the luciferase activity of the Mut group was not significantly changed (Fig. 5k, l), indicating that miR-889–3p suppressed MCTS1 expression by directly binding to the 3′ UTR of MCTS1 mRNA. At the same time, we can conclude that miR-889–3p binds and negatively regulates MCTS1.

circHIPK2 promotes malignant progression of LSCC by targeting MCTS1/IL-6

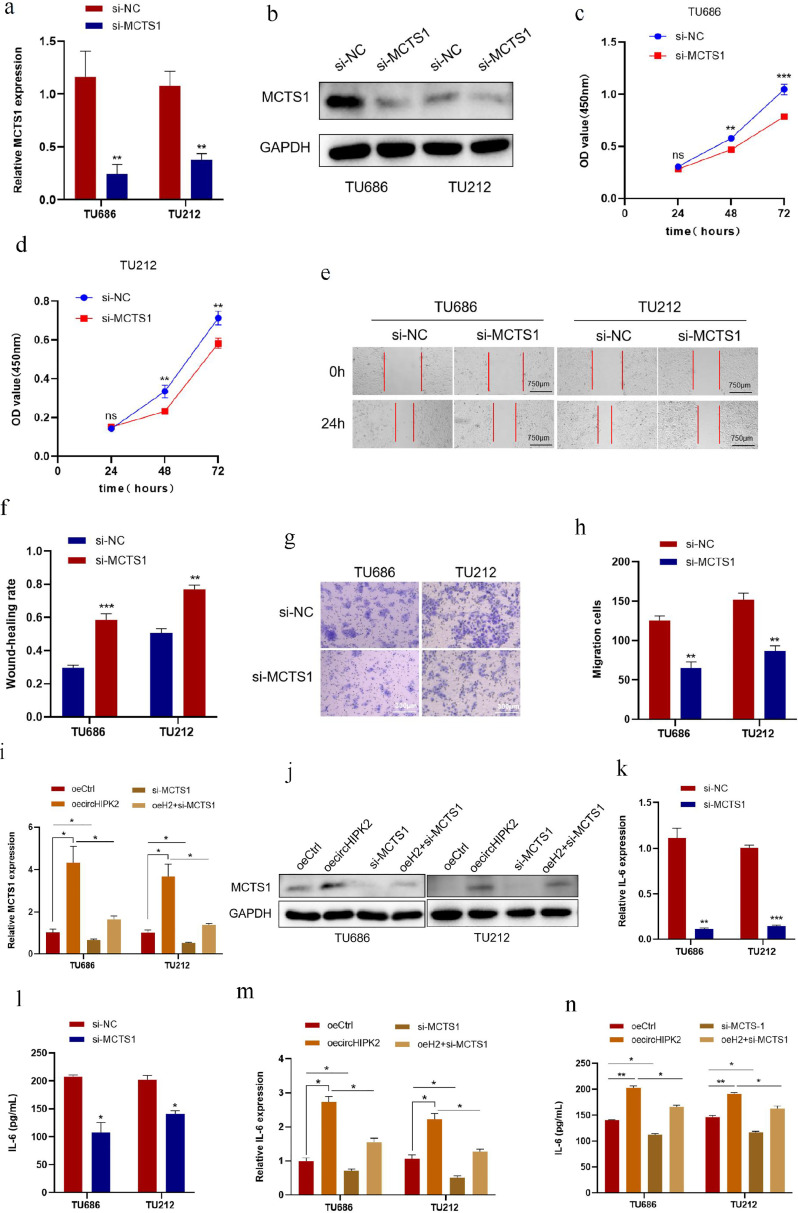

The above results suggested that MCTS1 is highly expressed in LSCC tissues and negatively regulated by miR-889–3p. We hypothesized that the function of MCTS1 on LSCC should be opposite to that of miR-889–3p and positively correlated with circHIPK2. To test this hypothesis, we used siRNA knockdown of MCTS1. qRT-PCR and Western blotting results showed that after transfection of siRNA into TU686 and TU212 cells, the mRNA and protein levels of MCTS1 were significantly decreased (Fig. 6a, b). CCK8, Wound healing and Transwell assays suggested that the proliferation and migration of TU686 and TU212 cells were inhibited after knocking down MCTS1 (Fig. 6c-h)

Fig. 6.

circHIPK2 promotes malignant progression of LSCC by targeting MCTS1/IL-6. a, b: si-MCTS1 was transfected into TU686 and TU212 cells, and the levels of MCTS1 mRNA and protein were detected by qRT-PCR and Western blotting. c, d: TU686 and TU212 cells were transfected with si-MCTS1, and CCK8 assay was used to detect cell proliferation at specified time points. e, f: Wound healing time after transfection of TU686 and TU212 cells with si-MCTS1 was detected. g, h: si-MCTS1 was transfected into TU686 and TU212 cells, and the migrative ability of the cells was detected by Transwell migration assay. i, j: circHIPK2 overexpression plasmids were transfected into TU686 and TU212 cells alone or together with si-MCTS1, and MCTS1 mRNA and protein levels were detected by qRT-PCR and Western blotting. k, l: si-MCTS1 were transfected into TU686 and TU212 cells, and the expression and concentration of IL-6 were detected by qRT-PCR and ELISA. m, n: circHIPK2 overexpression plasmids were transfected into TU686 and TU212 cells alone or together with si-MCTS1, and the expression and concentration of IL-6 were detected by qRT-PCR and ELISA. *P < 0.05, ⁎⁎P < 0.01,⁎⁎⁎P < 0.001.

To investigate whether circHIPK2 promotes the malignant progression of LSCC cells by regulating its downstream target gene MCTS1, we co-transfected si-MCTS1 and circHIPK2 overexpression plasmids into TU686 and TU212 cells. qRT-PCR and Western blotting results showed that circHIPK2 overexpression caused an increase in MCTS1 protein and mRNA levels in LSCC cells, while MCTS1 knockdown reversed the increase in MCTS1 induced by circHIPK2 overexpression at protein and mRNA levels (Fig. 6i, j).

MCTS1 undertakes a critical role in the TME. IL-6 is abundant in the TME and, as a common cytokine, is abnormally secreted to facilitate tumor progression. It has been reported that MCTS1 can suppress TNBC by modulating the IL-6/IL-6R pathway. Additionally, IL-6 promotes tumor growth and survival through its regulation of the inflammatory response within the TME [37,38]. We evaluated whether IL-6 could be regulated by circHIPK2 and MCTS1 in LSCC by qRT-PCR and ELISA assays. After knocking down MCTS1, qRT-PCR results indicated that the IL-6 mRNA level in LSCC cells decreased; ELISA results showed that the concentration of IL-6 in the supernatant of TU686 and TU212 cells decreased, and the ability of cells to secrete IL-6 decreased (Fig. 6k, l). At the same time, we found that circHIPK2 overexpression could increase the concentrations of IL-6 and IL-6 mRNA expression in TU686 and TU212 cells. After co-transfection with circHIPK2 overexpression plasmids and si-MCTS1, the concentration of IL-6 in the superserum of TU686 and TU212 cells was significantly decreased, and the expression of IL-6 mRNA was also downregulated; meanwhile, the effect of circHIPK2 in promoting IL-6 secretion in LSCC cells was reversed (Fig. 6m, n).

These results indicated that circHIPK2 could promote the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells by targeting to regulate the expression of MCTS1 and promoting the secretion of downstream IL-6.

Discussion

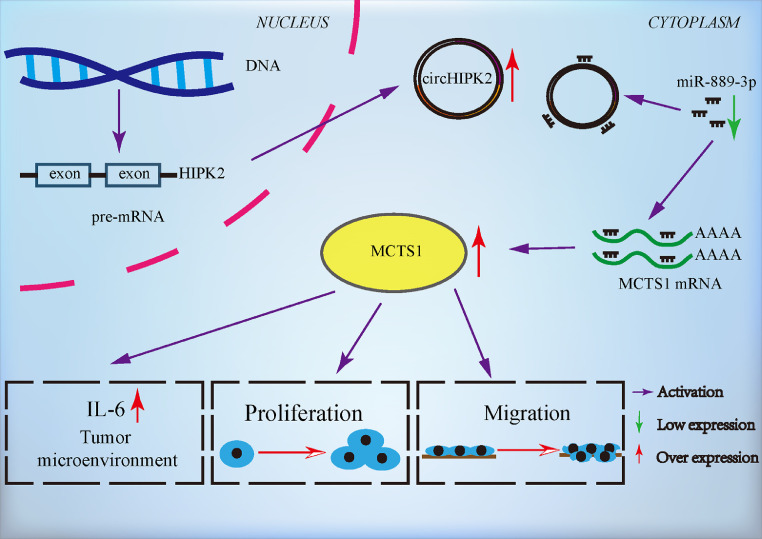

Recent studies have shown that circRNAs play a crucial role in the tumorigenesis, progression, and metastasis of malignant tumors [39,40]. In the present study, we validated the expression of circHIPK2 in LSCC and matched ANM tissues. CircHIPK2 was highly expressed in LSCC tissues, and its expression level was correlated with clinical pathophysiological features of LSCC patients. circHIPK2 enhanced the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells through the upregulation of EMT-associated proteins, MMP9, and tight junction proteins, all of which play critical roles in promoting tumor metastasis in the TME. circHIPK2 bound to miR-889–3p to attenuate its inhibitory effect on the target gene MCTS1, thereby eliciting overexpression of MCTS1 and promoting the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Schematic illustration of the regulatory mechanism of the circHIPK2/miR-889–3p/MCTS1 axis in LSCC malignant progression. circHIPK2 promoted the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells, and bound to miR-889–3p to attenuate its inhibitory effect on target gene MCTS1, eliciting the overexpression of MCTS1 and promoting the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells.

A study in 2020 has shown that knocking down circHIPK2 in neural stem cells (NSCs) promotes the targeted differentiation of NSCs into neurons, and sicircHIPK2-NSCs increases neuronal plasticity in the ischaemic brain, confers durable neuroprotection, and significantly reduces functional deficits [41]. Another study of gut microbiota and depression demonstrated that circHIPK2 expression was inhibited after transplantation of gut microbiota into NLRP3 KO mice, which significantly improved the astrocyte dysfunction in mice and relieved the symptoms of depression [42]. This discovery is echoed by another study, in which patients with major depressive disorder and healthy controls were recruited, and circHIPK2 was identified as a potential biomarker to diagnose major depressive disorder and predict its outcomes [43]. A study has explored the upstream regulator of circHIPK2, implying that autophagy inducer rapamycin could suppress astrocytic inflammation by inactivating the circHIPK2-SIGMAR1 axis [44]. circHIPK2 has been validated to promote the progression of non-small cell lung cancer and colon cancer [45,46]. In previous studies, we have found that circHIPK2 downregulates the expression of parental gene HIPK2 and promotes the proliferation of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells [23]. Taken together, circHIPK2 is a pathogenic driver in inflammation, tumor and other diseases.

LncRNAs, miRNAs and circRNAs can interact to form various post-transcriptional regulatory ceRNA networks [47]. The functions of these networks have been unveiled in many diseases [[48], [49], [50]]. In this study, we found that circHIPK2 is localized to the cytoplasm, suggesting that it has a function of ceRNA. miR-889–3p has been shown to protect against malignant tumors, including lung and cervical cancers [51,52]. Bioinformatics analysis have shown that miR-889–3p may be the target miRNA of circHIPK2. We further demonstrated that the expression level of miR-889–3p in LSCC tissues was significantly lower than that in ANM tissues, and inhibition on miR-889–3p expression promoted the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells. Luciferase reporter assay showed that miR-889–3p bound to circHIPK2, and rescue experiments revealed that inhibition on miR-889–3p reversed the inhibitory effect of circHIPK2 knockdown on LSCC malignant phenotypes. These findings indicate that circHIPK2 sponge miR-889–3p to fulfil its tumor-promoting function on LSCC cells.

MCTS1 is highly expressed in various cancer tissues, such as breast cancer and LSCC [27,53]. In this study, we found that MCTS1 was up-regulated in LSCC tissues. Cell phenotypic tests showed that MCTS1 promoted the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells. Bioinformatic analysis and luciferase reporting assay showed that MCTS1 was the direct target of miR-889–3p. circHIPK2 competitively binds to miR-889–3p, thus weakening the inhibitory effect of miR-889–3p on MCTS1 expression and upregulating MCTS1 expression. We further demonstrated that circHIPK2 promoted malignant progression of LSCC cells through upregulating MCTS1. In addition, MCTS1 is deeply implicated in tumor immunity [25,27,28,54]. IL-6 is a common cytokine, and its abnormal secretion promotes tumor development [55]. After inhibiting the expression of MCTS1, we found that the mRNA level and concentration of IL-6 were also decreased, while the expression of MCTS1 was downregulated. Furthermore, rescue experiments revealed that inhibition on MCTS1 expression could reverse the increase of IL-6 mRNA level and concentration following circHIPK2 overexpression.

Although this study has fully demonstrated that circHIPK2 is highly expressed in LSCC tissues and cells, it can up-regulate the expression of target gene MCTS1 by competitively binding to tumor suppressor miR-889–3p, promote the secretion of IL-6, and improve the TME to promote the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells. However, there are some limitations in this study. Many cytokines can affect the malignant progression of LSCC, and we only detected IL-6, and did not further explore whether circHIPK2 regulates other cytokines. The evidence that IL-6 is regulated by MCTS1 comes from the literature, and there is no relevant high-throughput verification screening, and the relationship between the two still needs to be explored. In addition, whether circHIPK2 creates a favorable TME for LSCC cells through other ways needs further research.

It is important to emphasize that, despite certain limitations in this study, its innovative contributions remain significant and noteworthy. First, this study identifies for the first time the competitive binding of circHIPK2 with miR-889–3p in LSCC. Second, it reveals that circRNA exerts its function through the regulation of the oncogene MCTS1. Third, this study provides evidence that the circHIPK2/miR-889–3p/MCTS1/IL-6 regulatory axis promotes the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells by modulating the TME. These findings provide a scientific basis for the potential use of circHIPK2 as a therapeutic target for LSCC in the future, which may be translated into clinical practice through further investigation.

Conclusion

In summary, circHIPK2 competitively binds to miR-889–3p to eliminate its inhibition on MCTS1, boost IL-6 secretion, and reshape the TME more favorable for LSCC cell proliferation, thus promoting the proliferation and migration of LSCC cells. High expression of circHIPK2 may predict the poor prognosis of LSCC. These findings provide new insights into the mechanism of LSCC progression, and theoretical basis for further clinical research on LSCC.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yang-Guang Sun: Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Zhen-Kun Yu: Writing – original draft, Resources, Formal analysis. Xi Chen: Writing – original draft, Resources, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis. Si-Yao Zhang: Validation, Data curation. Wan-Juan Wu: Visualization, Software, Data curation. Kai Liu: Resources, Project administration, Data curation. Lei Cheng: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Jiangsu Province Capability Improvement Project through Science, Technology and Education (JSDW202203) and Jiangsu Province Hospital Clinical Capacity Enhancement Project (JSPH-MA-2023-1) of China. The authors acknowledge the Nanjing Medical Key Laboratory of Laryngopharynx-Head & Neck Oncology, the Affiliated BenQ Hospital of Nanjing Medical University for providing the experimental platform and technical guidance. We also thank associate professor Yong-Ke Cao at the School of Foreign Languages of Nanjing Medical University for professional English-language proofreading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2025.102390.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

The data that has been used is confidential.

References

- 1.Johnson D.E., Burtness B., Leemans C.R., Lui V.W.Y., Bauman J.E., Grandis J.R. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2020;6:92. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00224-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lv Y., Wang Y., Zhang Z. Potentials of lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA networks as biomarkers for laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Hum. Cell. 2023;36:76–97. doi: 10.1007/s13577-022-00799-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim D.H., Kim S.W., Han J.S., Kim G.J., Basurrah M.A., Hwang S.H. The Prognostic Utilities of Various Risk Factors for Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023:59. doi: 10.3390/medicina59030497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santos A., Santos I.C., Dos Reis P.F., Rodrigues V.D., Peres W.A.F. Impact of Nutritional Status on Survival in Head and Neck Cancer Patients After Total Laryngectomy. Nutr. Cancer. 2022;74:1252–1260. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2021.1952446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baird B.J., Sung C.K., Beadle B.M., Divi V. Treatment of early-stage laryngeal cancer: a comparison of treatment options. Oral Oncol. 2018;87:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xue C., Li G., Zheng Q., Gu X., Bao Z., Lu J., et al. The functional roles of the circRNA/Wnt axis in cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2022;21:108. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01582-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang A., Zheng H., Wu Z., Chen M., Huang Y. Circular RNA-protein interactions: functions, mechanisms, and identification. Theranostics. 2020;10:3503–3517. doi: 10.7150/thno.42174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L., Yi J., Lu L.Y., Zhang Y.Y., Wang L., Hu G.S., et al. Estrogen-induced circRNA, circPGR, functions as a ceRNA to promote estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cell growth by regulating cell cycle-related genes. Theranostics. 2021;11:1732–1752. doi: 10.7150/thno.45302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He D., Yang X., Kuang W., Huang G., Liu X., Zhang Y. The novel circular RNA Circ-PGAP3 promotes the proliferation and invasion of triple negative breast cancer by regulating the miR-330-3p/Myc axis. Onco. Targets Ther. 2020;13:10149–10159. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S274574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong W., Dai Z.H., Liu F.C., Guo X.G., Ge C.M., Ding J., et al. The RNA-binding protein RBM3 promotes cell proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating circular RNA SCD-circRNA 2 production. EBioMedicine. 2019;45:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng K., Wang S. Circular RNAs: the crucial regulatory molecules in colorectal cancer. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2020;216 doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2020.152861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen C., Wu Z., Wang Y., Gao S., Da L., Xie L., et al. Downregulated hsa_circ_0077837 and hsa_circ_0004826, facilitate bladder cancer progression and predict poor prognosis for bladder cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2020;9:3885–3903. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu P., Zou Y., Li X., Yang A., Ye F., Zhang J., et al. circGNB1 facilitates triple-negative breast cancer progression by regulating miR-141-5p-IGF1R. Axis. Front. Genet. 2020;11:193. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao X., Cai Y., Xu J. Circular RNAs: biogenesis, mechanism, and function in human cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20 doi: 10.3390/ijms20163926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Z., Huang C., Zhang A., Lu C., Liu L. Overexpression of circRNA_100290 promotes the progression of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma through the miR-136-5p/RAP2C axis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020;125 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.109874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L., Wei Y., Yan Y., Wang H., Yang J., Zheng Z., et al. CircDOCK1 suppresses cell apoptosis via inhibition of miR‑196a‑5p by targeting BIRC3 in OSCC. Oncol. Rep. 2018;39:951–966. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.6174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duan X., Shen N., Chen J., Wang J., Zhu Q., Zhai Z. Circular RNA MYLK serves as an oncogene to promote cancer progression via microRNA-195/cyclin D1 axis in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Biosci. Rep. 2019:39. doi: 10.1042/BSR20190227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He J., Chen S., Wu X., Jiang D., Li R., Mao Z. Hsa_circ_0081534 facilitates malignant phenotypes by sequestering miR-874-3p and upregulating FMNL3 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Auris Nasus. Larynx. 2022;49:822–833. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2022.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia L., Wang Y., Wang C.Y. circFAT1 promotes cancer stemness and immune evasion by promoting STAT3 activation. Adv. Sci. 2021;8 doi: 10.1002/advs.202003376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan C., Tan F., Wu J., Zeng Z., Guo W., Huang H., et al. CircCCNB1 inhibits vasculogenic mimicry by sequestering NF90 to promote miR-15b-5p and miR-7-1-3p processing in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mol. Oncol. 2025 doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.13821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu L., Lu B., Li Y. Circular RNA circ_0008450 regulates the proliferation, migration, invasion, apoptosis and chemosensitivity of CDDP-resistant nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by the miR-338-3p/SMAD5 axis. Anticancer Drugs. 2022;33:e260–ee72. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000001197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ge J., Meng Y., Guo J., Chen P., Wang J., Shi L., et al. Human papillomavirus-encoded circular RNA circE7 promotes immune evasion in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2024;15:8609. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-52981-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang D., Huang H., Sun Y., Cheng F., Zhao S., Liu J., et al. CircHIPK2 promotes proliferation of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by down-regulating HIPK2. Transl. Cancer Res. 2022;11:2348–2358. doi: 10.21037/tcr-22-1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prosniak M., Dierov J., Okami K., Tilton B., Jameson B., Sawaya B.E., et al. A novel candidate oncogene, MCT-1, is involved in cell cycle progression. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4233–4237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y., Wang B., Gui S., Ji J. Multiple copies in T-cell malignancy 1 (MCT-1) promotes the Stemness of non-small cell lung cancer cells via activating interleukin-6 (IL-6) signaling through suppressing MiR-34a expression. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019;25:10198–10204. doi: 10.12659/MSM.919690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang M., Ma B., Liu X. MCTS1 promotes laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma cell growth via enhancing LARP7 stability. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2022;49:652–660. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.13640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weng Y.S., Tseng H.Y., Chen Y.A., Shen P.C., Al Haq A.T., Chen L.M., et al. MCT-1/miR-34a/IL-6/IL-6R signaling axis promotes EMT progression, cancer stemness and M2 macrophage polarization in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:42. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0988-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirk P., Wilson M.C., Heddle C., Brown M.H., Barclay A.N., Halestrap A.P. CD147 is tightly associated with lactate transporters MCT1 and MCT4 and facilitates their cell surface expression. EMBO J. 2000;19:3896–3904. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canning M., Guo G., Yu M., Myint C., Groves M.W., Byrd J.K., et al. Heterogeneity of the head and neck squamous cell carcinoma immune landscape and its impact on immunotherapy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019;7:52. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peltanova B., Raudenska M., Masarik M. Effect of tumor microenvironment on pathogenesis of the head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:63. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0983-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel B.P., Shah S.V., Shukla S.N., Shah P.M., Patel P.S. Clinical significance of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in patients with oral cancer. Head Neck. 2007;29:564–572. doi: 10.1002/hed.20561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luukkaa M., Vihinen P., Kronqvist P., Vahlberg T., Pyrhönen S., Kähäri V.M., et al. Association between high collagenase-3 expression levels and poor prognosis in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2006;28:225–234. doi: 10.1002/hed.20322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiori M.E., Di Franco S., Villanova L., Bianca P., Stassi G., De Maria R. Cancer-associated fibroblasts as abettors of tumor progression at the crossroads of EMT and therapy resistance. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:70. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0994-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y., McAndrews K.M., Kalluri R. Clinical and therapeutic relevance of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021;18:792–804. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00546-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun L., Xing G., Wang W., Ma X., Bu X. Proliferation-associated 2G4 P48 is stabilized by malignant T-cell amplified sequence 1 and promotes the proliferation of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. JDS. 2023;18:1588–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2023.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He B., Zhao Z., Cai Q., Zhang Y., Zhang P., Shi S., et al. miRNA-based biomarkers, therapies, and resistance in Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020;16:2628–2647. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.47203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wan S., Zhao E., Kryczek I., Vatan L., Sadovskaya A., Ludema G., et al. Tumor-associated macrophages produce interleukin 6 and signal via STAT3 to promote expansion of human hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1393–1404. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He G., Karin M. NF-κB and STAT3 - key players in liver inflammation and cancer. Cell Res. 2011;21:159–168. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kristensen L.S., Jakobsen T., Hager H., Kjems J. The emerging roles of circRNAs in cancer and oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022;19:188–206. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00585-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lei M., Zheng G., Ning Q., Zheng J., Dong D. Translation and functional roles of circular RNAs in human cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2020;19:30. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-1135-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang G., Han B., Shen L., Wu S., Yang L., Liao J., et al. Silencing of circular RNA HIPK2 in neural stem cells enhances functional recovery following ischaemic stroke. EBioMedicine. 2020;52 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y., Huang R., Cheng M., Wang L., Chao J., Li J., et al. Gut microbiota from NLRP3-deficient mice ameliorates depressive-like behaviors by regulating astrocyte dysfunction via circHIPK2. Microbiome. 2019;7:116. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0733-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu X., Fan Z., Yang T., Li H., Shi Y., Ye L., et al. Plasma circRNA HIPK2 as a putative biomarker for the diagnosis and prediction of therapeutic effects in major depressive disorder. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2024;552 doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2023.117694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang R., Cai L., Ma X., Shen K. Autophagy-mediated circHIPK2 promotes lipopolysaccharide-induced astrocytic inflammation via SIGMAR1. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023;117 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.109907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ren M., Song X., Niu J., Tang G., Sun Z., Li Y., et al. The malignant property of circHIPK2 for angiogenesis and chemoresistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Exp. Cell. Res. 2022;419 doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2022.113276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tong G., Cheng B., Wu X., He L., Lv G., Wang S. circHIPK2 has a potentially important clinical significance in colorectal cancer progression via HSP90 ubiquitination by miR485-5p. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2022;32:33–42. doi: 10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.2022042925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tay Y., Rinn J., Pandolfi P.P. The multilayered complexity of ceRNA crosstalk and competition. Nature. 2014;505:344–352. doi: 10.1038/nature12986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin C., Ma M., Zhang Y., Li L., Long F., Xie C., et al. The N(6)-methyladenosine modification of circALG1 promotes the metastasis of colorectal cancer mediated by the miR-342-5p/PGF signalling pathway. Mol. Cancer. 2022;21:80. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01560-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yao B., Zhu S., Wei X., Chen M.K., Feng Y., Li Z., et al. The circSPON2/miR-331-3p axis regulates PRMT5, an epigenetic regulator of CAMK2N1 transcription and prostate cancer progression. Mol. Cancer. 2022;21:119. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01598-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ding N., You A.B., Yang H., Hu G.S., Lai C.P., Liu W., et al. A Tumor-suppressive molecular axis EP300/circRERE/miR-6837-3p/MAVS Activates type I IFN pathway and antitumor immunity to suppress colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023;29:2095–2109. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-3836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu Q., Li Y., Li L., Guo M., Zou C., Xu Y., et al. MicroRNA-889-3p restrains the proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transformation of lung cancer cells via down-regulation of Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 1. Bioengineered. 2021;12:10945–10958. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.2000283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao X., Dong W., Luo G., Xie J., Liu J., Yu F. Silencing of hsa_circ_0009035 suppresses cervical cancer progression and enhances radiosensitivity through MicroRNA 889-3p-dependent regulation of HOXB7. MCB. 2021;41 doi: 10.1128/MCB.00631-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ma B., Wei X., Zhou S., Yang M. MCTS1 enhances the proliferation of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma via promoting OTUD6B-1 mediated LIN28B deubiquitination. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023;678:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2023.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eichner R., Heider M., Fernández-Sáiz V., van Bebber F., Garz A.K., Lemeer S., et al. Immunomodulatory drugs disrupt the cereblon-CD147-MCT1 axis to exert antitumor activity and teratogenicity. Nat. Med. 2016;22:735–743. doi: 10.1038/nm.4128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jones S.A., Jenkins B.J. Recent insights into targeting the IL-6 cytokine family in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018;18:773–789. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.