Abstract

Neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) is a major cause of vision loss worldwide. Current standard of care is repetitive intraocular injections of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors, although responses may be partial and non-durable. We report that circulating sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) carried by apolipoprotein M (ApoM) acts through the endothelial S1P receptor 1 (S1PR1) to suppress choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in mouse laser-induced CNV, modeling nAMD. In humans, low plasma ApoM levels were associated with increased choroidal and retinal pathology. Additionally, endothelial S1pr1 knockout and overexpressing transgenic mice showed increased and reduced CNV lesion size, respectively. Systemic administration of ApoM-Fc, an engineered S1P chaperone protein, not only attenuated CNV to an equivalent degree as anti-VEGF antibody treatment but also suppressed pathological vascular leakage. We suggest that modulating circulating ApoM-bound S1P action on endothelial S1PR1 provides a novel therapeutic strategy to treat nAMD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10456-025-09975-7.

Keywords: Apolipoprotein M, High-density lipoprotein, Sphingosine 1-phosphate, Angiogenesis, Vascular leak, Age-related macular degeneration

Introduction

The leading cause of vision loss among the elderly is age-related macular degeneration (AMD) [1]. In neovascular AMD (nAMD), pathological neovascularization and leakage of the choroidal vessels lead to retinal edema, hemorrhage and subretinal scars ultimately resulting in vision loss [2, 3]. Although the pathogenesis of nAMD involves a complex interplay between choroidal vessels, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and inflammatory cells, excessive production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and subsequent signaling events are known to be one of the major drivers of disease [4, 5].

Drugs that block VEGF signaling have shown favorable outcomes in enhancing visual function of nAMD patients and represent the mainstay of nAMD treatment [6]. However, the need for repetitive intravitreal injections, the resultant adverse effects and poor response of some patients are challenges [7, 8]. Therefore, novel therapeutic targets for nAMD are needed, especially for patients who do not respond to current therapies.

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), a bioactive lipid that signals via its G protein-coupled S1P receptor (S1PR) family is a major player in the vascular system. Endothelial cells (EC) express high levels of S1PR1 which is essential for vascular development and homeostasis. We have shown that S1PR1 restrains VEGF receptor signaling and induces vascular maturation during postnatal retinal angiogenesis [9, 10]. In a mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR), endothelial S1PR1 suppresses pathological neovascularization [11]. In addition, S1PR1 activation enhances VE-cadherin function at adherens junctions and maintains the vascular barrier in the retina [12], lung [13], and the brain [14, 15].

However, the biology of S1P is complex in the retina, because, for instance, S1PR2 action is induced during OIR and drives pathological angiogenesis while dispensable for vascular development [16]. Furthermore, high dose S1P treatment induces VEGF production and HIF1-α upregulation in RPE that expresses S1pr1, S1pr2 and S1pr5 in vitro [17]. During embryonic and postnatal development, proper S1P gradient and signaling appears to be critical for normal development of the neural retinal layers [18]. Given the importance of S1P in neuro/vascular development, a monoclonal antibody targeted against S1P was injected into the vitreous chamber in murine models of neovascularization and was reported to reduce neovascular development [19, 20]. However, the role of S1P in nAMD is not fully understood and rather controversial since, in addition to the preclinical data stated above, clinical trials with sonepcizumab, a humanized S1P neutralizing antibody, had no improvement in visual acuity, visual function and vascular leakage when co-treated with an anti-VEGF regimen but rather displayed higher adverse events including conjunctival and retinal hemorrhage [21].

In contrast to the anti-S1P monoclonal antibody which neutralizes retinal tissue S1P, our recent findings show that circulatory S1P activates endothelial S1PR1 to suppress pathological neovascularization in OIR [11]. Similarly, recent findings in laser-induced CNV using S1PR1 agonists exhibited improvement in vascular hyperpermeability and CNV formation [22, 23].

Circulating S1P is bound to plasma chaperones such as albumin and ApoM [24]. ApoM, a member of the lipocalin family of proteins, contains a lipid-binding pocket that associates with S1P and a tethered signal peptide that allows it to anchor to the HDL particle [25]. ApoM-bound S1P triggers sustained and Gαi-biased signaling and is thought to be a physiological mechanism that maintains the vascular endothelial barriers, NO-dependent control of vascular tone and EC survival [26]. Mice deficient for ApoM exhibit increased vascular leak in pulmonary microvessels and cerebral penetrating arterioles [27, 28]. To study the protective potential of ApoM, we generated a novel engineered S1P chaperone protein, ApoM-Fc [29], which selectively activates vascular S1PRs in a sustained manner to promote endothelial function while sparing lymphocyte S1PR1 that regulates lymphocyte trafficking. ApoM-Fc administration enhances endothelial barrier function, suppresses ischemia–reperfusion injury of the heart, kidney and the brain, and immune complex-mediated and acid-induced lung injury [30, 31]. Importantly, in the context of vascular retinopathies, ApoM-Fc potently protects against pathological retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) [11].

In this report, we investigated the therapeutic concept of endothelial S1PR1 agonism by circulating S1P in laser-induced CNV model that mimics exudative nAMD in humans, utilizing both genetic models and pharmacological approaches using a designer S1P chaperone which can be administered systemically (i.e. subcutaneous administration) to modulate the level of S1P and its receptors in vivo.

Results

Low serum ApoM levels are associated with human choroidal and retinal disease

Circulating ApoM which is associated with HDL particles binds S1P, and signals via endothelial S1PR1 to maintain physiological vascular barrier function [29]. To interrogate the possible association between plasma levels of ApoM and disorders of the choroid and retina (which includes nAMD), we utilized an open access tool that was developed based on an analysis of UK Biobank data from ~ 50,000 individuals [32]. A negative association was found between plasma levels of ApoM and the prevalence of disorders of the choroid and retina (N = 442) with an odds ratio of 0.6 [confidence interval 0.45–0.80] (P = 0.001). We also investigated whether there was an association between plasma levels of ApoM and the incidence of disorders of the choroid and retina (N = 2064). Here, too, a negative association was observed- hazard ratio of 0.75 [confidence interval 0.65–0.86] (P = 3.56 × 10–5). These data raise the possibility that reduced plasma ApoM levels pose a higher risk for the development of nAMD.

Laser-induced CNV is increased in ApoM knockout and decreased in overexpressing ApomTG transgenic mice

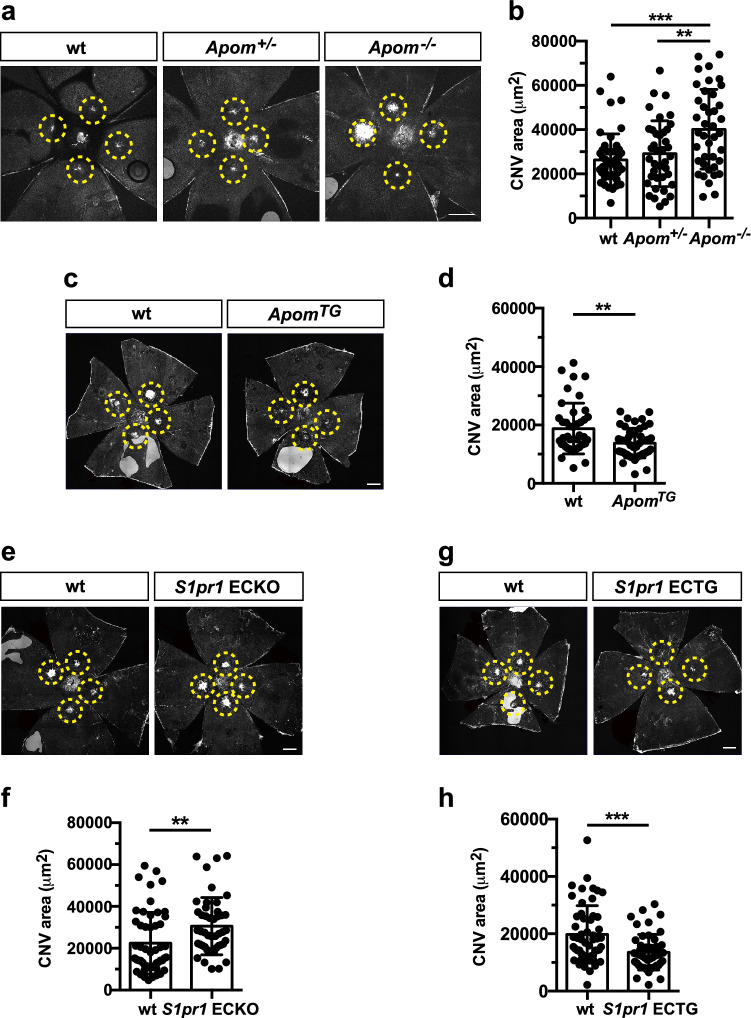

To determine if a causal relationship exists between altered plasma ApoM levels and nAMD, we employed an established laser-induced choroidal neovascularization (CNV) model on ApoM knockout (Apom−/−) and transgenic (ApomTG) mouse strains [24] and quantified CNV. Apom−/− mice exhibited larger neovascular lesion size following laser injury compared to littermate controls (Fig. 1a,b). The CNV lesion from Apom−/− mice contained increased number of EC (Suppl Fig. 1a,b). Exaggerated CNV formation was also observed in mice that lack S1P in red blood cells [33] (Suppl Fig. 1c,d), suggesting that reduced circulating S1P exacerbates CNV. In contrast, smaller CNV lesions were seen in ApomTG mice which have high circulating S1P. (Fig. 1c,d). Together, our results show that the presence of ApoM that controls S1P concentration in the circulatory system is critical for suppressing neovascularization after laser photocoagulation.

Fig. 1.

ApoM-bound S1P action via endothelial S1PR1 attenuates choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in mice. a Representative images of the retina from Apom−/−, Apom+/− and wild type (wt) control mice at day (D)14. b Quantification of IB4-positive CNV area (wt (n = 13 eyes/ 7 mice), Apom+/− (n = 10 eyes/ 5 mice) and Apom−/− (n = 12 eyes/6 mice), One-way ANOVA***, P = 0.0001, **, P = 0.0037). c Representative images of the CNV lesion from ApomTG and littermate control at D14. d Quantification of CNV area (wt (n = 12 eyes/ 7 mice) and ApomTG (n = 13 eyes/ 8 mice), unpaired, two-tailed students t-test (**, P = 0.0013)). e Representative images of the retina from S1pr1 ECKO and littermate control at D14. f Quantification of CNV area (wt (n = 14 eyes/ 8 mice) and S1pr1 ECKO (n = 13 eyes/ 8 mice), unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test (**, P = 0.0056)). g Representative images of the retina from S1pr1 ECTG and wt control at D14. h Quantification of CNV area (wt (n = 14 eyes/ 8 mice) and S1pr1 ECTG (n = 14 eyes/ 7 mice), (unpaired, two-tailed students t-test ***, P = 0.0003)). Data show means ± SD. Scale bar: 500 μm

ApoM-bound serum S1P activates endothelial S1PR1 to inhibit laser-induced CNV

Next, we utilized genetic mouse models of endothelial-specific S1pr modulation. In the retinal vessels, S1pr1,2, and 3 genes are expressed while S1pr4 and 5 are not expressed [10]. We found that the mice deficient for three S1PRs (S1pr1-3) in endothelium exhibited enlarged size of the CNV lesion (Suppl Fig. 2a, b). To investigate the role of endothelial S1PR1 in nAMD, we utilized tamoxifen inducible, endothelial cell-specific S1PR1 genetic loss- and gain of function mouse models. S1pr1 gene deletion in the vascular endothelium (S1pr1 ECKO) exhibited larger CNV lesions, whereas mice that overexpress S1PR1 (S1pr1 ECTG) showed significantly reduced neovascularization (Fig. 1e-h), suggesting the protective role of S1PR1 in nAMD. Taken together, these data allow us to propose that ApoM-bound circulating S1P activates the endothelial S1PR1 to restrain pathological neovascularization after laser photocoagulation.

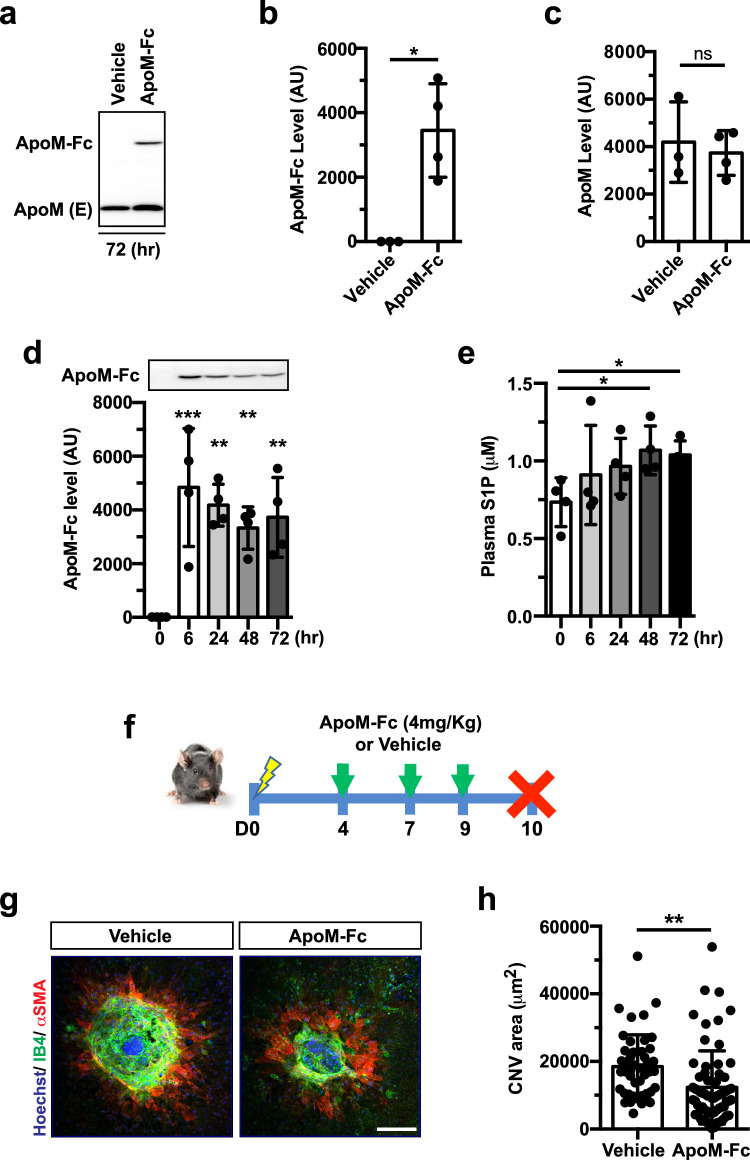

Systemic administration of S1P chaperone raises circulating S1P levels and inhibits laser-induced CNV

To activate the ApoM-S1P-endothelial S1PR1 signaling axis, we used ApoM-Fc, an engineered S1P chaperone that activates the endothelial S1PR1 selectively. When ApoM-Fc (4 mg/Kg) or vehicle was injected intraperitoneally, ApoM-Fc was detected in plasma 72 h after the injection without affecting endogenous ApoM expression (Fig. 2a–c). Kinetic experiments showed that plasma ApoM-Fc peaked at 6 h and remained elevated for up to 72 h (Fig. 2d). Plasma S1P levels increased at 48–72 h, suggesting time-dependent association of administered ApoM-Fc with endogenous S1P (Fig. 2e). Armed with these pharmacokinetic data, mice received ApoM-Fc or vehicle at D4, 7, 9 after laser photocoagulation and the CNV lesions were quantified at D10 (Fig. 2f). ApoM-Fc-treated mice showed significantly decreased CNV lesion size compared to vehicle controls (Fig. 2g,h).

Fig. 2.

Intraperitoneal ApoM-Fc administration suppresses CNV lesions. a Representative western blot showing ApoM-Fc and endogenous ApoM level in plasma 72 h after systemic ApoM-Fc (4 mg/kg) administration in mice. b, c Quantification of the bands shown in a. (Vehicle (n = 3 mice) and ApoM-Fc (n = 4 mice), unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test (*, P = 0.0102, ns, P > 0.9999). d ApoM-Fc protein levels in mouse plasma at various time points after a single i.p. injection of ApoM-Fc (n = 4 mice/ time point, one-way ANOVA, ***, P < 0.0001, **, P < 0.001). e S1P levels in plasma at various time points after ApoM-Fc administration (n = 4/ time point, one-way ANOVA, *, P < 0.01). f Experimental scheme for ApoM-Fc regimen. Mice were given ApoM-Fc (4 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle at the time indicated. g Representative images of CNV lesion from vehicle- and ApoM-Fc treated mice at D10. h Quantification of CNV area (Vehicle (n = 14 eyes/ 8 mice) and ApoM-Fc (n = 18 eyes/ 10 mice), unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test **, P = 0.0022). Data are means ± SD. Scale bar: 100 μm

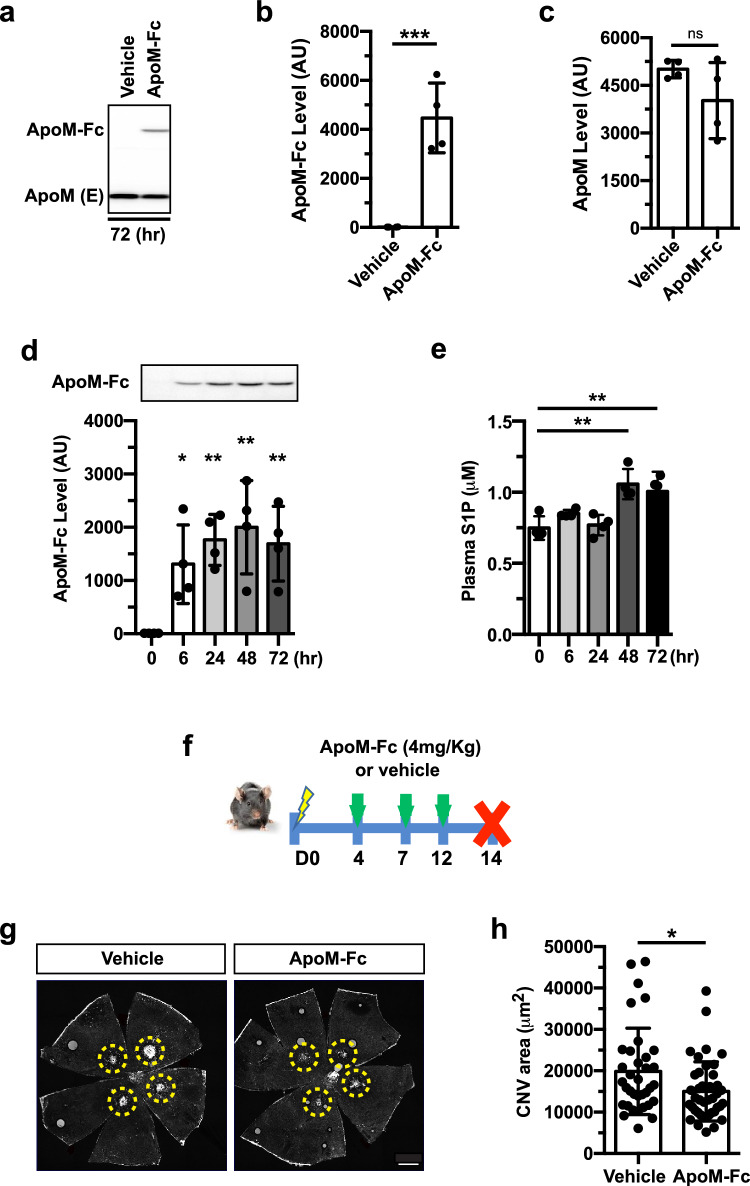

We next tested a clinically relevant delivery route of ApoM-Fc. ApoM-Fc and endogenous ApoM protein bands were observed in mouse plasma by western blot 72 h after the subcutaneous administration of ApoM-Fc (4 mg/kg), as shown in Fig. 3a–c. Time-course experiments revealed its delayed yet sustained ApoM-Fc expression and upregulated S1P level in plasma (Fig. 3d,e). To determine whether the changes of the delivery routes have any effect on the CNV progression, ApoM-Fc or vehicle were given to mice subcutaneously at D4, 7, 12 post-photocoagulation and the eyes were analyzed at D14 (Fig. 3f). The group that received ApoM-Fc showed suppression of CNV compared to the vehicle-treated group (Fig. 3g,h). Taken together, both i.p. and subcutaneous administration of ApoM-Fc were effective in reducing CNV, suggesting its therapeutic potential in the treatment of nAMD.

Fig. 3.

Subcutaneous ApoM-Fc administration attenuates CNV lesions. a Representative western blot showing ApoM-Fc and endogenous ApoM level in plasma 72 h after subcutaneous ApoM-Fc (4 mg/kg) administration in mice. b, c Quantification of bands shown in a. (Vehicle (n = 4 mice) and ApoM-Fc (n = 4 mice), unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test (***, P = 0.0008, ns, P > 0.9999). d ApoM-Fc protein levels in mouse plasma at various time points after a single subcutaneous injection of ApoM-Fc (n = 4 mice/ time point, one-way ANOVA, *, P < 0.01, **, P < 0.001). e S1P levels in plasma at various time points after ApoM-Fc administration (n = 4/ time point, one-way ANOVA, **, P < 0.001). f Experimental scheme for ApoM-Fc regimen. Mice were given ApoM-Fc (4 mg/kg) or vehicle subcutaneous at the time indicated. g Representative images of IB4 staining-positive CNV lesion from vehicle- and ApoM-Fc treated mice at D14. h Quantification of CNV area (Vehicle (n = 9 eyes/ 5 mice) and ApoM-Fc (n = 10 eyes/ 6 mice), unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test *, P = 0.0188). Data are means ± SD. Scale bar: 500 μm

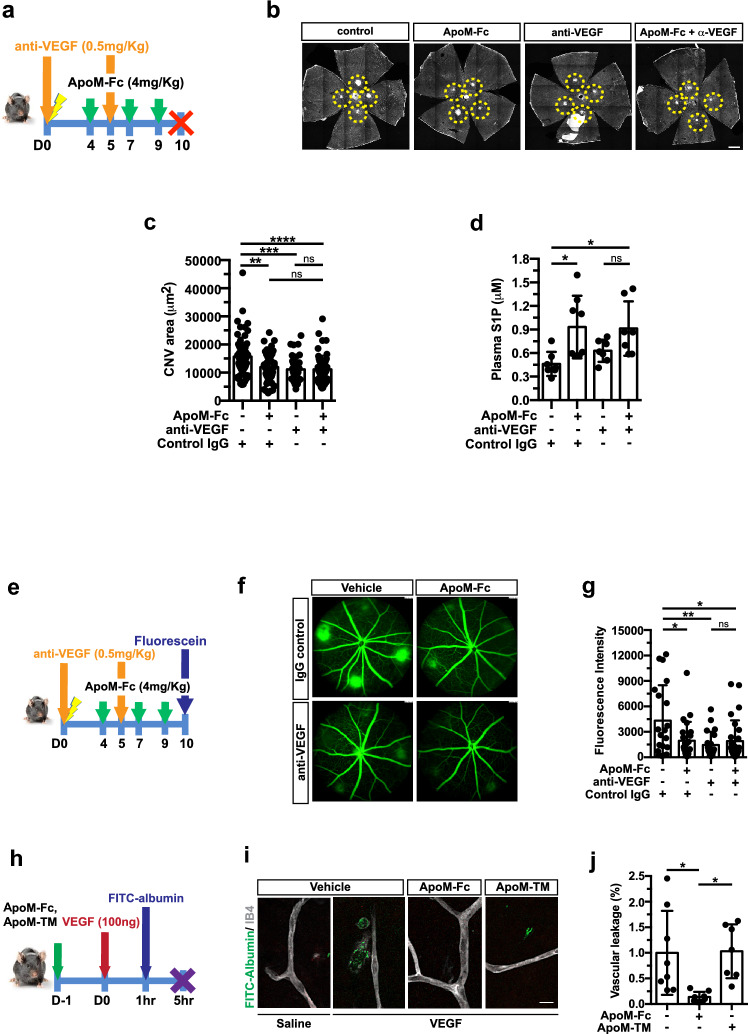

S1P chaperone treatment attenuated CNV and vascular leakage

Agents that block VEGF are efficacious in treating nAMD patients [34, 35]. We asked whether ApoM-Fc treatment achieves similar efficacy as anti-VEGF regimen and whether ApoM-Fc would provide enhanced efficacy when combined with anti-VEGF. We administered anti-VEGF mIgG2a antibody (anti-VEGF B20-4.1.1., referred to as anti-VEGF hereafter, 0.5 mg/kg) i.p. at D0 and 5 [36] either alone or together with ApoM-Fc administration i.p. at D4, 7 and 9 and mice were analyzed at day 10 (Fig. 4a). As shown in Fig. 4b,c, the ApoM-Fc treated group exhibited reduced CNV as effectively as the anti-VEGF treated group, ~ 24% and ~ 29%, respectively. However, the group which received both ApoM-Fc and anti-VEGF treatment did not show any additional suppressive effect (~ 29%) on neovascular lesions. As expected, circulating S1P in plasma was increased in the ApoM-Fc treated groups (Fig. 4d). We also used a higher dose of anti-VEGF (5 mg/kg) at D0 while following the same ApoM-Fc injection schedule (Suppl Fig. 3a). ApoM-Fc treatment achieved similar suppression of CNV as anti-VEGF treatment (Suppl Fig. 3b,c) but did not provide additional efficacy in reducing neovascular lesions. These results suggest that ApoM-Fc is an effective agent to attenuate neovascularization in laser-induced mouse model of CNV.

Fig. 4.

ApoM-Fc and anti-VEGF antibody reduces CNV lesion size and vascular leakage. a Experimental scheme for ApoM-Fc regimen and α-VEGF treatment. Mice were given either ApoM-Fc (4 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle or anti-VEGF (0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) at D0 and D5. b Representative images of IB4 staining-positive CNV lesions from treatment group at D10. Scale bar: 500 μm. c Quantification of CNV area (control (n = 17 eyes/ 10 mice), ApoM-Fc (n = 16 eyes/ 10 mice), anti-VEGF (n = 11 eyes/ 6 mice) and ApoM-Fc + anti-VEGF (n = 16 eyes/ 10 mice), One-way ANOVA ****, P < 0.0001, ***, P = 0.0004, **, P = 0.0020, ns, P > 0.9999). d Plasma S1P measurement at D10 (control (n = 7 mice), ApoM-Fc (n = 8 mice), α-VEGF (n = 7 mice) and ApoM-Fc + anti-VEGF (n = 7 mice), One-way ANOVA *, P < 0.01, ns, P > 0.9999). e Experimental scheme for ApoM-Fc regimen and anti-VEGF treatment and fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) at D10. f Representative images of fluorescein angiogram of IgG control-, ApoM-Fc-, anti-VEGF-, and both ApoM-Fc and anti-VEGF-treated mice 10 days after CNV induction. g Corrected fluorescence intensity normalized by optic nerve head area (control (n = 6 eyes/ 4 mice), ApoM-Fc (n = 7 eyes/ 4 mice), anti-VEGF (n = 7 eyes/ 4 mice) and ApoM-Fc + anti-VEGF (n = 8 eyes/ 5 mice), One-way ANOVA **, P = 0.0075, *, P < 0.01, ns, P > 0.9999). h Mice were given ApoM-Fc (4 mg/kg) or ApoM-TM (4 mg/kg) i.p. 24 h prior to intraocular injection of VEGF (0.1 µg/ eye), followed by FITC-albumin. i Representative images of vehicle-, ApoM-Fc- and ApoM-TM-treated retina. Scale bar: 20 μm. j Quantification of VEGF-induced vascular leakage (vehicle (n = 8 mice), ApoM-Fc (n = 7 mice), ApoM-TM (n = 8 mice), One-way ANOVA *, P < 0.01). Data show means ± SD

Next, we performed fundus fluorescein angiography to examine vascular leakage in the CNV lesions after treatment with ApoM-Fc, anti-VEGF, or combination thereof (Fig. 4e). Significant inhibition of vascular leak was observed in all treatment groups, even though the combination of ApoM-Fc and anti-VEGF did not provide additional suppressive activity (Fig. 4f,g).

ApoM-Fc inhibits CNV- and VEGF-induced vascular permeability

To determine whether ApoM-Fc treatment can directly antagonize VEGF-induced vascular leak, ApoM-Fc and triply-mutated ApoM (ApoM-TM; non-S1P binding mutant) were given i.p. one day prior to intraocular VEGF injection followed by FITC-albumin tracer leakage assessment (Fig. 4h). The presence of both ApoM-Fc and ApoM-TM in mouse plasma 24 h after the administration was confirmed (Suppl Fig. 4a,b). VEGF-induced vascular leak in the retina was completely inhibited by ApoM-Fc but not ApoM-Fc-TM (Fig. 4i,j). These results suggest that ApoM-Fc inhibits choroidal neovascularization and vascular permeability by counteracting VEGF action.

Discussion

S1P signaling via its 5 S1PRs drives complex biology in multiple organ systems including the retina. A large body of evidence supports the concept that circulating HDL-bound S1P signaling via the endothelial S1PR1 restrains vascular leak, inhibits excessive vascular sprouting induced by VEGF and promotes endothelial survival and function [9, 10]. We hypothesized that this pathway would provide a novel therapeutic strategy to control nAMD-associated vascular leak and vasoproliferation. Our findings from genetic mouse models of Apom KO and TG as well as endothelial S1PR1 loss-, and gain of function systems indeed support this hypothesis. None of the S1P pathway genes or ApoM have been identified as genetic modifiers of AMD in humans. However, HDL metabolism-related genes such as cholesterylester transfer protein (CETP), the lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) were found to be associated with AMD incidence [37, 38].

Translational studies of plasma S1P and ApoM levels in AMD patients have not been fully explored. However, recent release and analysis of UK biobank plasma proteomics data suggest that reduced circulating ApoM levels pose a higher risk for developing diseases of the choroid and the retina, among which nAMD is included [32]. Recent reports revealed that reduced plasma S1P in neonatal ROP patients showed inverse correlation with disease severity [39], and an association of a specific allele of APOM gene with diabetic microvascular disease in an Egyptian cohort [40]. Low ApoM levels in plasma have been seen in type 2 diabetes and maturity onset diabetes of young patients [41], even though its causal relationships in diabetic vascular complications of the eye have not yet been addressed. In addition, clinical use of S1PR functional antagonists that reduce S1PR1 levels on the cell surface by facilitating receptor endocytosis and degradation is linked to significant adverse events such as macular edema and visual impairment [42, 43]. Collectively, these studies suggest that plasma ApoM-bound S1P is a protective factor in retinal and choroidal vessels with high therapeutic potential, while clinical use of S1PR1 inhibitors poses a significant risk to retinal function and vision.

Although the laser-induced mouse CNV model is widely used to investigate the efficacy of therapeutics that influence the early stages of nAMD, this preclinical animal model cannot fully recapitulate the intricate processes seen in nAMD patients, partly due to anatomical differences between mice and humans [44]. Nevertheless, our work focused on endothelial S1PR1 signaling illustrates that plasma ApoM-S1P suppresses vascular leakage and neovascular lesion growth in the laser-induced CNV model. In addition to the use of genetic loss and gain of function models, we also demonstrate that systemic administration of ApoM-Fc is efficacious. Based on previous work from our laboratory [9, 10], we suggest that S1PR1-induced adherens junction assembly in the choroidal EC is likely to be a key mechanism involved.

The limitations of our study include the lack of analysis of S1P action on inflammatory cells such as neutrophils and macrophages which are recruited to the injury site at an early stage. Activation of S1PR2 and/or S1PR3 expressed by immune, myeloid and other parenchymal cells upon ApoM-Fc application could lead to pathological events such as exaggerated inflammatory signaling and RPE/ choroidal fibrosis. These possibilities will need to be examined in future studies. It is noteworthy that ApoM-Fc is more selective for S1PR1 than pro-inflammatory S1PR2 and S1PR3 in transfected cells with ectopic expression of S1PRs [29]. If inflammatory and fibrotic signaling pathways are induced by excessive ApoM-Fc administration, ApoA1-ApoM, a second generation S1P chaperone that we designed recently, may be useful in obviating these potentially adverse events [45]. This recombinant protein suppresses inflammation by the ApoA1 moiety in addition to stimulating the S1PR1-dependent vascular barrier function. In that regard, the recent demonstration that S1PR signaling promotes Norrin/ Wnt / ß-catenin signaling in developing endothelium [12] could be an additionally important aspect of ApoM-Fc treatment. Finally, the durability of benefit following ApoM-Fc administration and dose–response studies need to be determined in appropriate preclinical models of nAMD.

Systemic administration of ApoM-Fc has been shown to attenuate cardiovascular injury, CNS ischemic injury, and fibrosis (lung, liver, kidney) and pathological retinopathy [11, 29]. ApoM-Fc offers numerous advantages, including its long systemic stability and its ability to direct S1P-signaling toward sustained S1PR1 activation without affecting lymphocyte trafficking [29]. Indeed, we speculate that systemic self-administration of ApoM-Fc via a subcutaneous route, if proven to be efficacious in humans, would offer significant advantages to the current intravitreal treatment of anti-VEGF blocking therapeutics. We observed that the addition of systemic ApoM-Fc to anti-VEGF treatment did not further increase suppression of neovascularization and vascular leakage, despite equal potency to anti-VEGF when used alone. These findings suggest shared yet distinctive molecular- and spatiotemporal mechanisms between an anti-VEGF agent and S1P/ S1PR1 agonism. It is well established that S1P via the action of S1PR1 enhances VE-cadherin-mediated junctional assembly and stabilizes EC-mural cell interaction [11, 46]. Therefore, one can surmise that S1P carried by ApoM could facilitate proper junctional localization through endothelial S1PR1, which stabilizes choriopapillary EC and ultimately reduces vascular permeability while intravitreal anti-VEGF treatment immediately reduces VEGF-A signaling. This concept merits further investigation. Given that VEGF-A level in the eye is maintained to provide proper neuronal function and maintenance [47], ApoM-Fc therapy could achieve an advantage over an anti-VEGF regimen as it does not interfere with VEGF receptor signaling. Therefore, ApoM-Fc treatment can be an attractive alternative to treat patients who undergo incomplete response to anti-VEGF agents. Additionally, finding biomarkers that delineate such responses to the different therapies would help tailor the treatments.

Taken together, our results suggest that systemic ApoM-Fc administration is a potential therapeutic treatment, and shows an equivalent degree of efficacy as anti-VEGF treatment to reduce CNV in a preclinical mouse model. Beyond confirming ApoM-Fc as a potent therapeutic to counter neovascularization and excessive vascular leak, our study also emphasizes the potential of activating protective pathways to restore functional endothelium, complementary to blocking an excess of growth factors. Future development efforts need to focus on potential systemic adverse effects and optimal therapeutic regimen in relevant preclinical models of nAMD. Given that many nAMD patients are refractory to current therapies, further therapeutic development studies of ApoM-Fc are warranted.

Methods

Animals

All mouse experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Boston Children’s Hospital. Specific pathogen-free C57BL6/J mice (#000664, 8- 10 weeks old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Transgenic mouse models used in this study are the following: Apolipoprotein M transgenic (ApomTG) and Apom-null (Apom−/−) [24], SphK RBCKO (SphK EpoR-Cre) [33], S1pr1f/f (a kind gift from Dr. Richard Proia, NIDDK, NIH) and S1pr1f/stop/f [10], Cdh5-CreERT2 [48] (a kind gift from Dr. Ralf Adams, Max Plank Institute) mice. Mouse strains harboring tamoxifen-inducible, endothelial cell-specific S1pr1 gene regulation were generated by crossing the S1pr1f/f and S1pr1f/stop/f to Cdh5-CreERT2 that yields S1pr1f/f; Cdh5-CreERT2 (S1pr1 loss-of-function, S1pr1 ECKO) and S1pr1f/stop/f; Cdh5-CreERT2 (S1pr1 gain-of-function, S1pr1 ECTG), respectively [10, 11]. 1.5 mg (mg) of tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich, #5648) dissolved in corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich, #C8267) was injected i.p. for 5 consecutive days to induce or delete S1pr1 gene in mice in both Cre+ and Cre− littermates at 8—10 weeks old. Both males and females were used.

Antibody and recombinant ApoM-Fc biologic treatment

Murine anti-VEGF antibody (B20.4.1.1.) [49] was kindly provided by Genentech. ApoM-Fc or ApoM-TM were expressed in CHO cells and purified by affinity and gel filtration chromatography as described previously [29]. Antibodies including isotype control (rat IgG2a, α-trinitrophenol, BioXCell, #BE0089) and ApoM-Fc biologics were diluted in sterile saline and injected i.p. or subcutaneously as described in the experimental schemes. For combination treatment of ApoM-Fc and anti-VEGF, ApoM-Fc was administered at concentration of 4 mg/Kg body weight at D4, 7, and 9 and anti-VEGF at 0.5 mg/Kg on the day of laser photocoagulation (day 0) and D5. Male mice were used for acute vascular permeability assay and laser-induced CNV concerning anti-VEGF, ApoM-Fc or ApoM-TM treatment.

Laser induced choroidal neovascularization

CNV was induced in mice via laser photocoagulation as described previously [50]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (120 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Pupils were dilated with a topical application of Tropicamide (Somerset Therapeutics, #NDC 70069–121-01). A green argon laser (incident power of 300 mW and pulse duration of 70 ms), coupled with the Micron IV imaging-guided system (Phoenix Research Laboratories), was used to apply laser burns to four distinct areas of the fundus in each eye. Sterile eye lubricant (Optixcare, Aventix) was applied to both eyes and mice were placed on a prewarmed plate until recovery. CNV lesion was quantified 10 to 14 days post-photocoagulation.

Immunostaining of RPE/ choroid flat mount

Mice were euthanized at the time indicated. Eyes were enucleated and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 2 h at room temperature (RT). The posterior eye cups containing the RPE, choroid, sclera were dissected under stereomicroscope and permeabilized with 0.8% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h at RT. The CNV lesions were stained with Alexa-fluorophore conjugated GS lectin IB4 (Invitrogen, 2.5 μg/ml), Alexa Flour488-conjugated, anti-ERG (Abcam, #ab196374), Cy3-conjugated, anti-smooth muscle actin α (αSMA, Millipore Sigma, #C6198), Hoechst (Invitrogen, #H21486) in PBlec buffer (0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM MnCl2, 1% Triton X-100 in PBS (pH 6.8)) [10] overnight at 4 °C. After thorough washing in PBlec buffer, flatmounts were prepared with scleral side down in permount mounting medium (FisherSci, #SP15-100) and coverslipped before imaging.

Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA)

Vascular leak was evaluated by quantifying hyperfluorescent lesions 10 days after laser-burn. After anesthetizing the mice, both eyes were dilated, and mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 1% AK-FLUOR® (NDC 17478-101-12, Akorn, Lake Forest, IL, USA) diluted in 0.9% sodium chloride. Vascular leak was captured using the Micron IV retinal imaging system (Phoenix Research Laboratories), and fluorescent fundus photographs were captured 5 min after fluorescein injection and used for vascular permeability quantification.

Acute vascular permeability

VEGF-A-induced retinal vascular permeability was performed as described [51]. Briefly, 7–9 weeks old male C57Bl6/J were treated with ApoM-Fc, ApoM-TM (S1P non-binding mutant) [29] or an equal volume of saline at 4 mg/kg via i.p. injection. 24 h later, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (1–4% isoflurane/ 100% oxygen) through a mouse gas anesthesia head holder. Pupils were dilated with a solution of 1% tropicamide phenylephrine hydrochloride and applied with 0.5% proparacaine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution on each eye. Intraocular injections were performed by inserting a NANOFIL Syringe (10uL, World Precision Instruments) into the vitreous humor. The needle was aimed to penetrate the eyeball near its equator under a dissection microscope to introduce a total of 100 ng recombinant VEGF (R&D systems, #293-VE) in a volume of 0.5 μl (or saline) to avoid increases in intraocular pressure. After the injection, eyes were treated with 0.5% antibiotic ophthalmic ointment. After 1 h, mice were treated with FITC-Albumin (Sigma Aldrich, #A9771, 10 mg/kg) intravenously via a retro-orbital route to assess vascular leak. After 4 h, mice were euthanized, eyes were enucleated and fixed using 4% PFA in PBS. Retinas were dissected out and stained for Alexa647-conjugated GS-isolectin (IB4, Invitrogen, #I32450), flat-mounted and imaged following the published protocol [10].

Plasma collection, S1P extraction and S1P measurement

Blood samples were collected from either submandibular vein (for non-terminal) via cheek punch or vena cava (for terminal) in 1–5 μl of 0.5 M EDTA- containing tubes. Samples were centrifuged at 2000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. Plasma (supernatants) was collected and stored at -80 °C until S1P measurement. Plasma S1P was extracted and measured by UHPLC-MS/MS as previously described [52]. Briefly, 100 μL of plasma were diluted in TBS Buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 0.15 M NaCl) followed by 100 μL of precipitation solution (20 nM D7-S1P in methanol) to extract S1P. After centrifugation at 18,000 rpm for 5 min, supernatants were transferred to vials for UHPLC-MS/MS analysis (see below). C18-S1P (Avanti Lipids) was dissolved in methanol to obtain a 1 mM stock solution. Standard samples were prepared in 4% fatty acid free BSA (Sigma Aldrich, #A6003) in TBS at final concentration of 1 mM. Before analysis, the 1 mM S1P solution was diluted with 4% BSA in TBS to obtain 0.5 mM, 0.25 mM, 0.125 mM, 0.0625 mM, 0.03125 mM, 0.0156 mM, and 0.0078 mM. S1P in diluted samples (100 mL) were extracted with 100 mL of methanol containing 20 nM of D7-S1P. Precipitated samples were centrifuged and the supernatants were transferred to vials for mass spectrometric analysis. The internal deuterium-labeled D7-S1P standard (Avanti Lipids, 200 nM stock) was prepared in methanol.

The samples were analyzed with the Orbitrap Exploris 480 mass spectrometer fronted with a FLEX ion source coupled to Vanquish Horizon UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a reverse phase column (XSelect CSH C18 XP column 2.5 µm, 2.1 mm X 50 mm, Waters) maintained at 55 °C in positive ion mode. The gradient solvents were as follows: Solvent A (water/methanol/formic acid 97/2/1 (v/v/v)) and Solvent B (methanol/acetone/water/formic acid 68/29/2/1 (v/v/v/v)). The analytical gradient was run at 0.4 mL/min from 50 to 100% Solvent B for 5.4 min, 100% for 2.6 min, followed by one minute of 50% Solvent B. A targeted MS2 strategy (also known as parallel reaction monitoring, PRM) was performed to isolate S1P (380.26 m/z) and D7-S1P (387.30 m/z) using a 1.6 m/z window, and the HCD-activated (stepped CE 20, 30, 40%) MS2 ions were scanned in the Orbitrap at 60 K. The area under the curve (AUC) of MS2 ions (S1P, 264.2686 m/z; D7-S1P, 271.3125 m/z) was calculated using Skyline46. Quantitative linearity was determined by plotting the AUC of the standard samples (C18-S1P) normalized by the AUC of internal standard (D7-S1P); (y) versus the spiked concentration of S1P (x). Correlation coefficient (R2) was calculated as the value of the joint variation between x and y. A linear regression equation was used to determine analyte concentrations.

Immunoblot analysis

The content of exogenous and endogenous ApoM proteins in mouse plasma was detected using anti-ApoM-specific immunoblot analysis [29]. Briefly, 1 μl of mouse plasma was heated to 95 °C for 5 min in 2 × Laemmli’s sample buffer containing 10% β-mercaptoethanol. Samples were loaded on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad, #1610156) and transferred to PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, #1620177). Equal loading was confirmed by Ponceau S staining. Blots were incubated in blocking buffer (Intercept blocking buffer, LI-COR, #927-60001) for 1 h at RT, followed by incubation with rabbit monoclonal anti-ApoM antibody (Abcam, EPR2904, #ab91656) overnight at 4 °C. Signals were detected by probing with goat anti-Rabbit IgG-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (R&D Systems, #HAF017) for 30 min at RT and Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore Sigma, #WBKLS0500), and visualized with Azure 600 Imaging System (Azure Biosystems).

Confocal microscopy and image processing

All images were taken under the same setting on LSM800 confocal microscope (Zeiss) equipped with Zen2.1 (Zeiss) software. EC plan-Neofluar 10x/0.3 or a Plan-Apochromat 20x/0.8 objectives were used to obtain z-stacked, tile scan images. CZI files were imported into RGB Tiff files and were quantified using Image J software.

Quantification of CNV, fluorescence intensity

CNV lesion size was quantified by IB4 staining positive area. RGB Tiff files were imported into ImageJ to generate binary images. The maximal border of each CNV legion was manually selected using the freehand selection tool under digital magnification and determine the area recorded in pixels. Exclusion criteria were applied as described previously [36]. Pixeled areas were converted to μm2 using the scale bar.

For fluorescence intensity quantification, binary images were generated using image thresholding function in ImageJ software. The fluorescent area of each CNV lesion as well as the optic nerve head was measured in pixels. Corrected fluorescent intensity was calculated by pixel intensities of individual CNV lesions normalized by the intensity of the optic nerve head area [53].

Acute retinal vascular permeability was accessed by acquiring 4–5 fields of view (FOV) per retinal flat mount and all FOV was averaged for each flat mount. Vascular leak was defined as percentage of pixel intensity per total area, assuming that fluorescence within the blood vessels would be cleared out during 4 h of circulation [51]. Vascular leak was shown as fold change compared to saline-treated controls.

Human study participants and cohort analysis

The UK Biobank is a cohort study of approximately 500,000 individuals who were 40–69 years old at baseline. Enrollment occurred from 2006 to 2010. The diagnostic data for disorders of the choroid and retina were linked to UK electronic health records and classified according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 codes. Prevalent and incident disease were defined as events that occurred before and after the subject’s baseline visit, the same time that blood samples were collected [32]. The UK Biobank Pharma Proteomic Project conducted a blood-based proteomic profiling of a randomly selected subset of UK Biobank participants. The average age of the 53,026 participants was 56.8 years and median follow up was 14.8 years. The Olink Explore™ Proximity Extension Assay in combination with next-generation sequencing was used to quantify 2,923 unique proteins in plasma. ApoM was one of the plasma proteins that was quantified. A detailed analysis of plasma proteins linked to prevalent and incident diseases was carried out [32]. An open-access comprehensive proteome-phenome resource (https://proteome-phenome-atlas.com/) was provided that enabled the interrogation of associations between plasma levels of ApoM and prevalent and incident disorders of the choroid and retina. Associations between levels of plasma proteins and disease endpoints were determined using logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards regression for prevalent and incident disease, respectively. Regressions were performed with the adjustment of participants’ information at baseline including sex, age, townsend deprivation index, ethnicity, body mass index, fasting time, smoking status, season of blood collection and blood age.

Statistics

Data are shown as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 9 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Significant differences were determined by Student’s t test when comparing 2 groups of samples or one-way ANOVA with multiple comparison procedures using Bonferroni test for more than 2 groups comparison.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by NIH grants EY031715 and AG078602 to TH and American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship 25POST1356140 to T.F.D. We thank Genentech Inc. for their kind gift of the anti-VEGF antibody.

Author contributions

BJ- conduct experiments, analyze data, prepare figures, write manuscript (entire manuscript) HY—conduct experiments (laser injury model) AK—conduct experiments, analyze data, prepare figures (S1P measurements) TFD—conduct experiments, analyze data, prepare figures (VEGF-induced vascular leak) MA—provide instrumentation access, funding acquisition (LC/MS/MS) TK—conduct experiments (S1P measurements in LC/MS/MS) SAS- method development, provide instrumentation access- (S1P measurements in LC/MS/MS) AJD— provided expertise in the analysis of UK biobank plasma proteomics data ZF—experimental design, editing of manuscript CN—conception of project, experimental design, conduct experiments, analysis of data, prepare figures (initial CNV experiments) LEHS—conception of project, editing of manuscript TH -conception and directing of project, experimental design, writing and editing of manuscript, funding acquisition.

Funding

Funding was supported by National Institutes of Health, EY031715.

Data availability

Original data of this manuscript has been deposited to the DRYAD repository 10.5061/dryad.z8w9ghxpp.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

TH and LEHS are listed as inventors on patent applications on ApoM-Fc. TH and AJD are founders of Apovita Therapeutics, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Colin Niaudet, Email: colin.niaudet@inserm.fr.

Lois E. H. Smith, Email: lois.smith@childrens.harvard.edu

Timothy Hla, Email: timothy.hla@childrens.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Ambati J, Atkinson JP, Gelfand BD (2013) Immunology of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Rev Immunol 13(6):438–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell P, Liew G, Gopinath B, Wong TY (2018) Age-related macular degeneration. Lancet 392(10153):1147–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guillonneau X, Eandi CM, Paques M, Sahel JA, Sapieha P, Sennlaub F (2017) On phagocytes and macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res 61:98–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biasella F, Plossl K, Baird PN, Weber BHF (2023) The extracellular microenvironment in immune dysregulation and inflammation in retinal disorders. Front Immunol 14:1147037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleckenstein M, Keenan TDL, Guymer RH, Chakravarthy U, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Klaver CC et al (2021) Age-related macular degeneration. Nat Rev Dis Primers 7(1):31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khanna S, Komati R, Eichenbaum DA, Hariprasad I, Ciulla TA, Hariprasad SM (2019) Current and upcoming anti-VEGF therapies and dosing strategies for the treatment of neovascular AMD: a comparative review. BMJ Open Ophthalmol 4(1):e000398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Usui-Ouchi A, Friedlander M (2019) Anti-VEGF therapy: higher potency and long-lasting antagonism are not necessarily better. J Clin Invest 129(8):3032–3034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young M, Chui L, Fallah N, Or C, Merkur AB, Kirker AW et al (2014) Exacerbation of choroidal and retinal pigment epithelial atrophy after anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina 34(7):1308–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaengel K, Niaudet C, Hagikura K, Lavina B, Muhl L, Hofmann JJ et al (2012) The sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor S1PR1 restricts sprouting angiogenesis by regulating the interplay between VE-cadherin and VEGFR2. Dev Cell 23(3):587–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung B, Obinata H, Galvani S, Mendelson K, Ding BS, Skoura A et al (2012) Flow-regulated endothelial S1P receptor-1 signaling sustains vascular development. Dev Cell 23(3):600–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niaudet C, Jung B, Kuo A, Swendeman S, Bull E, Seno T et al (2023) Therapeutic activation of endothelial sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 by chaperone-bound S1P suppresses proliferative retinal neovascularization. EMBO Mol Med 15(5):e16645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanagida K, Engelbrecht E, Niaudet C, Jung B, Gaengel K, Holton K et al (2020) Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor signaling establishes AP-1 gradients to allow for retinal endothelial cell specialization. Dev Cell 52(6):779-93e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oo ML, Chang SH, Thangada S, Wu MT, Rezaul K, Blaho V et al (2011) Engagement of S1P (1)-degradative mechanisms leads to vascular leak in mice. J Clin Invest 121(6):2290–2300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanagida K, Liu CH, Faraco G, Galvani S, Smith HK, Burg N et al (2017) Size-selective opening of the blood-brain barrier by targeting endothelial sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114(17):4531–4536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nitzsche A, Poittevin M, Benarab A, Bonnin P, Faraco G, Uchida H et al (2021) Endothelial S1P (1) signaling counteracts infarct expansion in ischemic stroke. Circ Res 128(3):363–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skoura A, Sanchez T, Claffey K, Mandala SM, Proia RL, Hla T (2007) Essential role of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 2 in pathological angiogenesis of the mouse retina. J Clin Invest 117(9):2506–2516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terao R, Honjo M, Aihara M (2017) Apolipoprotein M inhibits angiogenic and inflammatory response by sphingosine 1-phosphate on retinal pigment epithelium cells. Int J Mol Sci 19(1):112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang C, Bian G, Ren P, Xiang J, Song J, Yu C et al (2018) S1P transporter SPNS2 regulates proper postnatal retinal morphogenesis. FASEB J 32(7):3597–3613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caballero S, Swaney J, Moreno K, Afzal A, Kielczewski J, Stoller G et al (2009) Anti-sphingosine-1-phosphate monoclonal antibodies inhibit angiogenesis and sub-retinal fibrosis in a murine model of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization. Exp Eye Res 88(3):367–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie B, Shen J, Dong A, Rashid A, Stoller G, Campochiaro PA (2009) Blockade of sphingosine-1-phosphate reduces macrophage influx and retinal and choroidal neovascularization. J Cell Physiol 218(1):192–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lpath IRP. Efficacy and Safety Study of iSONEP With & Without Lucentis/Avastin/Eylea to Treat Wet AMD (Nexus). ClinicalTrialsgov 2015.

- 22.Nakamura S, Yamamoto R, Matsuda T, Yasuda H, Nishinaka A, Takahashi K et al (2024) Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1/5 selective agonist alleviates ocular vascular pathologies. Sci Rep 14(1):9700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sorenson CM, Farnoodian M, Wang S, Song YS, Darjatmoko SR, Polans AS et al (2022) Fingolimod (FTY720), a sphinogosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist, mitigates choroidal endothelial proangiogenic properties and choroidal neovascularization. Cells 11(6):969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christoffersen C, Obinata H, Kumaraswamy SB, Galvani S, Ahnstrom J, Sevvana M et al (2011) Endothelium-protective sphingosine-1-phosphate provided by HDL-associated apolipoprotein M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(23):9613–9618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Axler O, Ahnstrom J, Dahlback B (2008) Apolipoprotein M associates to lipoproteins through its retained signal peptide. FEBS Lett 582(5):826–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galvani S, Sanson M, Blaho VA, Swendeman SL, Obinata H, Conger H et al (2015) HDL-bound sphingosine 1-phosphate acts as a biased agonist for the endothelial cell receptor S1P1 to limit vascular inflammation. Sci Signal 8(389):ra79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christensen PM, Liu CH, Swendeman SL, Obinata H, Qvortrup K, Nielsen LB et al (2016) Impaired endothelial barrier function in apolipoprotein M-deficient mice is dependent on sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1. FASEB J 30(6):2351–2359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathiesen Janiurek M, Soylu-Kucharz R, Christoffersen C, Kucharz K, Lauritzen M (2019) Apolipoprotein M-bound sphingosine-1-phosphate regulates blood-brain barrier paracellular permeability and transcytosis. Elife. 10.7554/eLife.49405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swendeman SL, Xiong Y, Cantalupo A, Yuan H, Burg N, Hisano Y et al (2017) An engineered S1P chaperone attenuates hypertension and ischemic injury. Sci Signal. 10.1126/scisignal.aal2722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burg N, Swendeman S, Worgall S, Hla T, Salmon JE (2018) Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 signaling maintains endothelial cell barrier function and protects against immune complex-induced vascular injury. Arthritis Rheumatol 70(11):1879–1889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ding BS, Yang D, Swendeman SL, Christoffersen C, Nielsen LB, Friedman SL et al (2020) Aging suppresses sphingosine-1-phosphate chaperone ApoM in circulation resulting in maladaptive organ repair. Dev Cell 53(6):677-90e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng YT, You J, He Y, Zhang Y, Li HY, Wu XR et al (2025) Atlas of the plasma proteome in health and disease in 53,026 adults. Cell 188(1):253-71e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiong Y, Yang P, Proia RL, Hla T (2014) Erythrocyte-derived sphingosine 1-phosphate is essential for vascular development. J Clin Invest 124(11):4823–4828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karasu B, Celebi ARC (2022) The efficacy of different anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents and prognostic biomarkers in monitoring of the treatment for myopic choroidal neovascularization. Int Ophthalmol 42(9):2729–2740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peden MC, Suner IJ, Hammer ME, Grizzard WS (2015) Long-term outcomes in eyes receiving fixed-interval dosing of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents for wet age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 122(4):803–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gjolberg TT, Wik JA, Johannessen H, Kruger S, Bassi N, Christopoulos PF et al (2023) Antibody blockade of Jagged1 attenuates choroidal neovascularization. Nat Commun 14(1):3109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neale BM, Fagerness J, Reynolds R, Sobrin L, Parker M, Raychaudhuri S et al (2010) Genome-wide association study of advanced age-related macular degeneration identifies a role of the hepatic lipase gene (LIPC). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(16):7395–7400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen W, Stambolian D, Edwards AO, Branham KE, Othman M, Jakobsdottir J et al (2010) Genetic variants near TIMP3 and high-density lipoprotein-associated loci influence susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(16):7401–7406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nilsson AK, Andersson MX, Sjobom U, Hellgren G, Lundgren P, Pivodic A et al (2021) Sphingolipidomics of serum in extremely preterm infants: Association between low sphingosine-1-phosphate levels and severe retinopathy of prematurity. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 1866(7):158939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tageldeen MM, Badrawy H, Abdelmeguid M, Zaghlol M, Gaber N, Kenawy EM (2021) Apolipoprotein M gene polymorphism Rs805297 (C-1065A): association with type 2 diabetes mellitus and related microvascular complications in South Egypt. Am J Med Sci 362(1):48–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frances L, Croyal M, Ruidavets JB, Maraninchi M, Combes G, Raffin J et al (2024) Identification of circulating apolipoprotein M as a new determinant of insulin sensitivity and relationship with adiponectin. Int J Obes (Lond) 48(7):973–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zarbin MA, Jampol LM, Jager RD, Reder AT, Francis G, Collins W et al (2013) Ophthalmic evaluations in clinical studies of fingolimod (FTY720) in multiple sclerosis. Ophthalmology 120(7):1432–1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia-Martin E, de Ruiz GE, Satue M, Gil-Arribas L, Jarauta L, Ara JR et al (2021) Progressive functional and neuroretinal affectation in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimod. J Neuroophthalmol 41(4):415-e23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salas A, Badia A, Fontrodona L, Zapata M, Garcia-Arumi J, Duarri A (2023) Neovascular progression and retinal dysfunction in the laser-induced choroidal neovascularization mouse model. Biomedicines 11(9):2445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin YC, Swendeman S, Moreira IS, Ghosh A, Kuo A, Rosario-Ferreira N et al (2024) Designer high-density lipoprotein particles enhance endothelial barrier function and suppress inflammation. Sci Signal 17(824):eadg9256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paik JH, Skoura A, Chae SS, Cowan AE, Han DK, Proia RL et al (2004) Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor regulation of N-cadherin mediates vascular stabilization. Genes Dev 18(19):2392–2403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tolentino M (2011) Systemic and ocular safety of intravitreal anti-VEGF therapies for ocular neovascular disease. Surv Ophthalmol 56(2):95–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pitulescu ME, Schmidt I, Benedito R, Adams RH (2010) Inducible gene targeting in the neonatal vasculature and analysis of retinal angiogenesis in mice. Nat Protoc 5(9):1518–1534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fuh G, Wu P, Liang WC, Ultsch M, Lee CV, Moffat B et al (2006) Structure-function studies of two synthetic anti-vascular endothelial growth factor Fabs and comparison with the Avastin Fab. J Biol Chem 281(10):6625–6631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gong Y, Li J, Sun Y, Fu Z, Liu CH, Evans L et al (2015) Optimization of an image-guided laser-induced choroidal neovascularization model in mice. PLoS ONE 10(7):e0132643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dorweiler TF, Singh A, Ganju A, Lydic TA, Glazer LC, Kolesnick RN et al (2024) Diabetic retinopathy is a ceramidopathy reversible by anti-ceramide immunotherapy. Cell Metab 36(7):1521-33e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kuo A, Checa A, Niaudet C, Jung B, Fu Z, Wheelock CE et al (2022) Murine endothelial serine palmitoyltransferase 1 (SPTLC1) is required for vascular development and systemic sphingolipid homeostasis. Elife. 10.7554/eLife.78861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wigg JP, Zhang H, Yang D (2015) A quantitative and standardized method for the evaluation of choroidal neovascularization using MICRON III fluorescein angiograms in rats. PLoS ONE 10(5):e0128418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Original data of this manuscript has been deposited to the DRYAD repository 10.5061/dryad.z8w9ghxpp.