Abstract

The formation of biomolecular condensates via phase separation relates to various cellular functions. Reconstituting these condensates with designed molecules facilitates the exploration of their mechanisms and potential applications. Sequence-designed DNA nanostructures enable the investigation of how structural design influences condensate formation and the construction of functional artificial condensates. Despite the high designability of DNA-based condensates, free nanostructures that do not assemble into condensates remain a challenge. Combining DNA nanostructures with other molecules, such as peptides, represents a promising approach to overcoming the limitations of DNA condensates and gaining a deeper understanding of molecular condensates. Herein, we report the effects of cationic oligolysines with several residues on DNA condensate formation assembled from Y-shaped DNA nanostructures. DNA condensate formation was enhanced by oligolysines at an appropriate L/P ratio, which refers to the ratio of positively charged amine groups in lysine (L) to negatively charged nucleic acid phosphate groups (P). Oligolysines with five residues enhanced condensate formation while maintaining the sequence-specific interaction of DNA. In contrast, oligolysines inhibited condensate formation depending on the L/P ratio and residue number. This was attributed to nanostructure deformation caused by oligolysines. These results suggest that the amount and length of cationic peptides significantly affect the self-assembly of branched DNA nanostructures. This study offers important insights into biomolecular condensates that can guide further development of DNA/peptide hybrid condensates to enhance the functions of artificial condensates for use in artificial cells and molecular robots.

1. Introduction

Weak multivalent interactions between biomolecules lead to the formation of gel- or liquid-like biomolecular condensates via phase separation.1−3 In vitro reconstitution of these condensates is a prominent area of research aimed at elucidating their formation mechanisms and functions.4−7 In living cells, intrinsically disordered regions and low-complexity domains in proteins that do not form specific structures exhibit phase separation and assemble into condensates.1 Given that these condensates are formed through multivalent interactions,8 such as hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and electrostatic interactions, characterizing their underlying mechanisms and functions is challenging. Creating condensates from synthetic biopolymer molecules can improve our understanding of biomolecular condensates and allows the exploration of their potential applications due to their known components and predictable interactions.9−11 In particular, DNA-based approaches provide promising means to investigate, design, and utilize biomolecular condensates.12,13

DNA nanotechnology enables the construction of arbitrarily shaped nanostructures by designing base sequences based on the Watson–Crick base pairing.14,15 DNA (or RNA) nanostructures, often Y- or X-shaped, form condensates (DNA/RNA condensates) through interactions between multiple sticky-ends at the tips of their branched structures.16−28 Condensate formation has been explained with a theoretical phase-separation model.28 The most notable feature of DNA condensates is their high designability; the formation temperature,16,17 physical properties,20,27 and size of the condensates25 can be tuned by changing the sequence of the sticky-ends or the shape of the structure. By leveraging this designability and utilizing sequence-specific molecular recognition, researchers have demonstrated potential applications for DNA condensates, including chemical reactors (artificial organelles)29−31 and sensing and computing functions.21,22,32,33 The activity of DNA condensates is primarily based on specific interactions with target signal molecules, such as nucleic acid strands. However, the nanostructures that do not form condensates remain in the bulk solution.16,22,32 These free nanostructures can consume signal molecules and inhibit the functional expression of the condensates, reducing their efficiency in various applications. However, this phenomenon has not been sufficiently evaluated for DNA condensates.

One approach to decrease the number of free nanostructures involves mixing cationic polymers with DNA nanostructures to weaken the electrostatic repulsion between DNA molecules and enhance greater condensate formation. A mixture of poly-l-lysine (PLL) and DNA forms condensates through phase separation,34−38 wherein the flexibility and rigidity of DNA strands and stacking interactions significantly affect the characteristics of the DNA-PLL condensates. Moreover, previous studies have shown that mixing PLL and genomic DNA induces structural folding of DNA.39 Although phase separation of DNA and PLL mixtures has been investigated in the fields of biochemistry and biophysics, the effects of cationic oligomers and polymers on the formation of DNA condensate assembled from DNA nanostructures have not been adequately explored.

Herein, we evaluate the effects of cationic oligopeptides on condensate formation and sequence-specific interaction. Oligolysines were selected over PLL to focus on residue number, as PLL typically has a wide residue number distribution. We mixed oligolysines with the DNA nanostructures and compared the amount of free nanostructures by fluorescence microscopy. Molecular dynamics simulations were performed to investigate the interactions between oligolysine and DNA nanostructures, revealing the effects of oligolysine at the molecular level. Oligolysine exerted dual effects on condensate formation: enhancement and inhibition (Figure 1). Additionally, the effect of oligolysine on the sequence specificity of DNA condensates was investigated. The results presented in this study demonstrate the pioneering use of hybrid condensates comprising the designed DNA nanostructures and peptides, expanding the potential applications of DNA-based condensates.

Figure 1.

Enhancement and inhibition of DNA condensate formation induced by oligolysine. The Y-shaped DNA nanostructures (Y-motifs) self-assemble into DNA condensates. A certain amount of the Y-motifs remains in bulk solution. Depending on the amount of oligolysine and residue numbers, condensate formation is enhanced (fewer free nanostructures) or inhibited (many free nanostructures).

2. Methods

2.1. Peptide Synthesis

Oligolysines were synthesized using the conventional 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) solid-phase method on CLEAR-Amide Resin (Peptide Institute, Osaka, Japan).40 Oligolysines were subjected to elongation by repeated condensation of Fmoc-l-Lys(Boc)–OH (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and deprotection of the Fmoc groups. The synthetic oligolysines were deprotected and cleaved from the resin by treatment with trifluoroacetic acid containing 5% H2O and 5% triisopropylsilane, followed by lyophilization. The lyophilized powder was resuspended in ultrapure water. The concentrations of oligolysines were determined using a microvolume spectrometer (DS-11FX; DeNovix, Wilmington, DE, USA) by measuring the absorbance at 205 nm.41 The structures of the oligolysines were analyzed using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (Autoflex maX; Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) (Figure S1); 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid was used as the matrix. Mass spectra showed that the dominant signal originated from oligolysines with the intended residue numbers at K5, K10, and K20. The oligolysines were used for experiments without further purification.

2.2. DNA Condensate Assembly

DNA strands used in this study were purchased from Eurofins Genomics (Tokyo, Japan). Fluorophore-modified DNAs were of high-performance liquid chromatography purification grade; the others were oligonucleotide purification cartridge grade. DNA was stored in distilled water at −20 °C until use. DNA concentration was measured using a microvolume spectrometer at 280 nm absorbance. DNA sequences are listed in Table S1. The Y-motifs comprised Y-1, Y-2, and Y-3, and 10% of Y-2 was replaced with Y-2_Alexa488, lacking sticky ends, for visualization. For the assembly of DNA condensates, necessary DNA was mixed in a test tube at 2.5 μM of each strand (exceptions: 2.25 μM Y-2 and 0.25 μM Y-2_Alexa488) with a buffer comprising 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 150 mM NaCl (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan). When appropriate, different amounts of oligolysine were added to the solutions to obtain the desired L/P ratio. The DNA concentration was retained to minimize impacts on the size and growth behavior of the condensates.25 The total negative charge of the Y-motif was 126 (three strands of 42 nucleotides). We considered 10% Y-2_Alexa488 as the standard Y-2 strand for simple calculations. The test tube was placed on a thermal cycler (MiniAmp Thermal Cycler; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and the temperature was lowered from 85 to 25 °C at a rate of −1 °C/s.

2.3. Visualizing DNA Condensates

Glass observation chambers were constructed to visualize the sample solution after thermal annealing. Glasses and coverslips measuring 22 mm × 40 mm and 22 mm × 22 mm, respectively, with a thickness of 0.17 mm, were obtained from Matsunami Glass (Kishiwada, Japan). Glass and coverslips were assembled using double-sided tape. To avoid the adsorption of DNA and oligolysines, a 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution was immersed in the slit between the glass and the coverslip. After 10 min, the BSA solution in the glass observation chamber was washed with ultrapure water and dried under an airflow. The sample solution was immersed into a slit between the BSA-coated glass and the coverslip, followed by sealing with manicure paste. Samples in the observation chamber were visualized under a fluorescence microscope (IX73; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Alexa405 and Alexa488 signals were visualized using objective lenses (20×, LUCPlanFLN, Olympus, or 40×, UPlanFLN, Olympus) and a mercury lamp with U-FUNA and U-FBNA filter cubes, respectively. The images were acquired using a CMOS camera (ORCA-Spark; Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). A stage heater (TPi-110RX; Tokai Hit, Fujinomiya, Japan) was used to alter the sample temperature. For imaging ATTO550 modified oligolysines and DNA condensates, a confocal laser scanning microscope (FV1000; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used. Alexa488 and ATTO550 were visualized at excitation wavelengths of 473 and 559 nm, respectively.

2.4. Intensity Ratio Analysis

Image analysis was performed using the open-access software platform Fiji (ImageJ). First, all images with the Alexa488 signal were converted to 12 bit intensity depth. The images were treated using a median filter with a filter radius of five pixels. Finally, the maximum and minimum intensities within a square of 600 pixels at the center of the images were calculated. The obtained intensity values were used to calculate the intensity ratio (minimum/maximum). All analyzed images from three experiments were captured under the same conditions (20× objective lens, 30 ms exposure time, and 24 camera-gain value).

2.5. Co-localization Analysis

Co-localization was analyzed using Fiji and its plugin, the Just Another Co-localization Plugin (JACoP), on the Bioimaging and Optics Platform.42 The acquired images to visualize Alexa405 or Alexa488 signals were converted to 12 bit intensity depths. The JACoP plugin was used for image analysis with the Otsu’s autothreshold selection method to calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient.

2.6. All-Atom Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

All-atom MD simulations were performed with the CHARMM36m force field43 using LAMMPS software.44 A Y-motif model with three 8-bp arms and three 4 nt sticky ends was placed in a periodic simulation box. An oligolysine model was randomly added to the system. Three oligolysine lengths, including 5-mer, 10-mer, and 20-mer poly-l-lysine (denoted as K5, K10, and K20, respectively), were used; the number of oligolysines varied based on the targeted L/P ratio. The system was solvated by adding water. The salt concentration was set to 150 mM NaCl, and the corresponding Na+ and Cl– ion concentration was added. A summary of the simulation systems is provided in Table S2. After steepest-descent energy minimization, each system underwent a 100 ns NPT run at a temperature of 300 K and a pressure of 1 atm; trajectory data were collected every 10 ps. The temperature was maintained using a Nosé–Hoover thermostat45,46 and the pressure was controlled using a Parrinello–Rahman barostat.47,48 Nonbonded interactions were calculated with a cutoff distance of 1.2 nm. The particle–particle particle mesh (PPPM) method49 was used to calculate long-range electrostatic interactions. The motion equations were integrated using the Verlet algorithm50 with a 2 fs time step, along with the SHAKE algorithm51 to constrain the hydrogen bond lengths.

The RMSD for phosphate atoms was calculated for the average structure of the Y-motif from the last 50 ns of the system without oligolysine; the average values and standard deviations of the RMSD for the last 50 ns were obtained. The average end-to-end distance of the Y-motif was defined as the distance between the phosphate atoms at the edges of each arm. The average angle was defined as the two vectors extending from the center of mass of the phosphate atoms at the branch point to the edges of each arm. VMD52 was used to generate the images.

2.7. Coarse-Grained MD Simulation

Coarse-grained (CG) MD simulations were carried out with the Martini 3.0 force field53 using the LAMMPS software. Atomistic representations of the Y-motif model with an 8-bp arm without sticky ends were converted to CG models using the martinize.py script. Elastic Networks54 were applied to each arm, with a distance cutoff of 1.0 nm using a force constant of 1000 kJ/mol/nm2, to maintain the DNA double helix conformation. Two Y-motif molecules were placed in a periodic simulation box and solvated by adding 48,300 water beads. Following the all-atom MD simulations, CG models for the different oligolysine lengths (K5, K10, and K20) were adopted, and the number of chains varied depending on L/P ratio. The salt concentration was fixed at 150 mM NaCl. A summary of simulation systems is provided in Table S3. After steepest-descent energy minimization, systems were equilibrated for 2 ns with a 10 fs time step at 300 K and a pressure of 1 atm. Production runs using a 20 fs time step were performed for 400 ns in the NPT ensemble at 300 K and 1 atm; trajectory data were collected every 20 ps. The temperature was maintained with a Nosé–Hoover thermostat and the pressure was controlled with a Parrinello–Rahman barostat. Electrostatic interactions were treated using the damped shifted force method55 with a dampening parameter of 0.2 Å–1. A cutoff of 1.1 nm was applied for LJ and electrostatic interactions. The trajectory data from the last 100 ns were used for analysis. The time-averaged contact fraction between Y-motif and each oligolysine was calculated using dr_sasa software56 with a probe radius of 0.264 nm. VMD was used to generate the images.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. DNA Condensate Formation with Oligolysines

The sequence and shape designs of the DNA nanostructures were adopted from a previous study (Table S1).16 The Y-shaped DNA nanostructures (Y-motifs) comprised three 42-nucleotide (nt) DNA strands. Y-motifs with three 8 nt sticky-ends self-assembled into DNA condensates (Figure 1). One strand was modified with a fluorescent molecule (alexa488) for visualization. Peptides with three different numbers of lysine residues (K = 5, 10, or 20) were synthesized by Fmoc solid-phase synthesis (Figure S1).40,41 Oligolysine was mixed with DNA strands and a buffer solution (20 mM Tris–HCl and 150 mM NaCl); the solution was annealed on a thermal cycler to form DNA condensates. Without oligolysine, the Y-motifs formed condensates (Figure 2a), as previously reported.30 At 25 °C, the condensates were in a gel-like state, while at approximately 50 °C they were in a liquid-like state (Figure S2). The maximum and minimum intensities in the fluorescence images were measured, and the intensity ratio was calculated to evaluate the amount of free nanostructures. Without oligolysine, the intensity ratio was 0.35 (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Microscopic observations of DNA condensates with or without oligolysines and evaluation of free nanostructures. (a) Representative fluorescence microscope image of DNA condensates formed without oligolysines (left) and intensity ratio between minimum and maximum intensities in fluorescence images. The data were obtained from three experiments. Error bar represents standard deviation. (b) Representative fluorescence microscope images of DNA condensate prepared with (i) K5, (ii) K10, and (iii) K20. Representative charge ratios (number of positively charged amine oligolysine groups (L) to the number of negatively charged Y-motif phosphate groups (P); L/P ratio) are shown. (c) The intensity ratio of fluorescence microscope images in the presence of K5, K10, and K20 at different L/P ratios. The data were obtained from three experiments. Error bar represents standard deviation; black dashed line: intensity ratio of DNA condensates without oligolysines. (d) Schematic illustration of mixing Y-motifs without sticky ends and oligolysines (left) and representative fluorescence microscope images of K5 at L/P 4, K10 at L/P 2 and 1, and K20 at L/P 1 (right). Scale bars = 20 μm.

The effects of K5 mixed with Y-motifs were evaluated at different concentrations. The ratio of the number of positively charged amine groups of oligolysine (L) to the negatively charged phosphate groups of Y-motifs (P) (lysine/phosphate (L/P) ratio) was assessed. As the experimental conditions were pH 8.0 and lysine has a positive charge below pH 10.5,57 the negatively charged phosphate groups in DNA formed electrostatic interactions with positively charged lysine. When the L/P ratio was 4, with a large excess positive charge in the solution, the fluorescence intensity was strong for the condensate with a very low background [Figure 2b(i)]. The intensity ratio value (0.05) was low, suggesting that condensate formation was enhanced while the amount of free nanostructures dramatically decreased (Figure 2c). This is likely due to the positive charge of the oligolysines weakening the electrostatic repulsion among the DNAs and enhancing the self-assembly of the nanostructures. Co-localization of dye-labeled K5 and DNA condensates was observed (Figure S3), demonstrating that oligolysines and Y-motifs interacted electrostatically and self-assembled into condensates. Notably, no microscale structures were observed when the Y-motifs without sticky ends (SE-less Y-motif) were mixed with oligolysine under 150 mM NaCl (Figures 2d and S4). This suggests that the observed self-assembly was due to sticky end interactions.

At an L/P ratio of 1.0, with equal positive and negative charges, condensates showed weak intensities with high background, indicating that condensate formation was inhibited by oligolysine. Inhibition was observed in the L/P range of 2.0–0.2 in K5 (Figures 2c and S5). A further decrease in the L/P ratio resulted in condensate formation (L/P: 0.07), similar to those without oligolysine (Figure 2a).

Next, we investigated the effect of the number of lysine residues on condensate formation. K10 and K20 were mixed with Y-motifs at various concentrations [Figure 2b(ii,iii), S6 and S7]. When the L/P ratio was changed, the effect trend was similar to that of K5; that is, the enhancement and inhibition of condensate formation were induced at different L/P ratios. In contrast, although the L/P ratio of 1 and 2 in K5 led to inhibition, the L/P ratio of 2 in K10 and K20 enhanced condensate formation (Figure 2b,c). Under the same L/P ratio, different numbers of lysine residues exhibited different effects on condensate formation. Among K5, K10, and K20, K10 and K20 had similar effects on condensate formation (enhancement or inhibition) at certain L/P ratios (Figure 2c). An increase in the amount of oligolysine tended to reduce condensate formation (Figure S8).

K10 and K20 exerted different effects on the condensate formation of the SE-less Y-motif (Figure 2d). When the SE-less Y-motifs were mixed at an L/P ratio of 1 with K20, not K10, condensates were observed. This suggests that the condensates observed with K20 at L/P ratios >1 were not primarily driven by sticky-end interactions but rather by electrostatic interactions between DNA molecules and oligolysines. Additionally, condensate formation was observed in solutions of SE-less Y-motifs with K10 at an L/P ratio of 2, suggesting that under these conditions, the condensate was primarily formed via electrostatic interactions. Taken together, the enhanced condensate formation induced by oligolysines can be classified as either sticky end-based or electrostatic interaction-based, depending on the residue number of oligolysines and the L/P ratio.

3.2. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

We constructed all-atom models of the Y-motif and oligolysines with 5, 10, or 20 residues (Figure 3) to obtain insights into the effect of oligolysines on inhibiting condensate formation. In MD simulations, the length of the DNA strands that formed the Y-motif was shortened from 42 to 22 nt due to the limitation of computational resources.

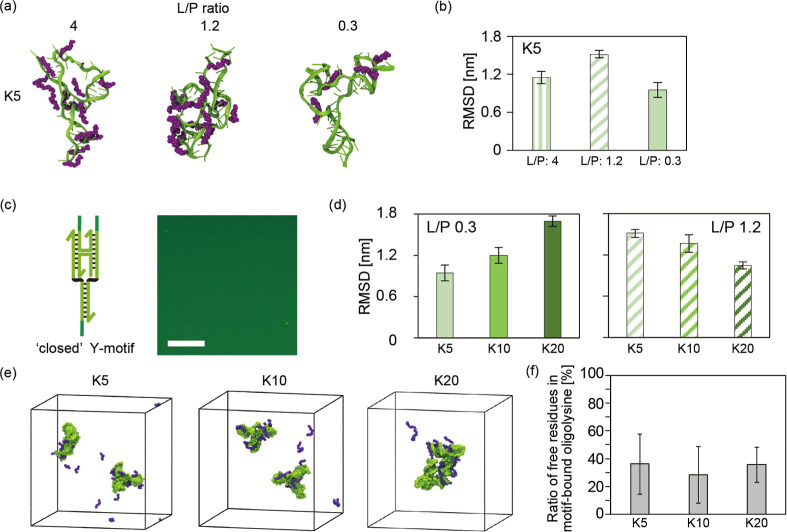

Figure 3.

Conformational changes in the Y-motif (green) induced by interactions with oligolysines (purple). (a) Representative snapshots of all-atom MD simulations in the Y-motif with K5 at different L/P ratios. Only oligolysines attaching to the Y-motif are shown. (b) Comparison of the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the Y-motif mixed with oligolysine from the Y-motif alone. Error bars represent standard deviation. (c) Schematic of a closed Y-motif and a representative fluorescence microscopic image of sample solutions prepared with the closed Y-motif. Scale bar: 20 μm. (d) Comparison of the RMSD of the Y-motif mixed with oligolysine at an L/P of 0.3 or 1.2. (e) Representative snapshots of coarse-grained MD simulations in the sticky end-less (SE-less) Y-motifs with K5, 10, and 20 at an L/P of 1.1. (f) Free residue ratio in oligolysines bound to the motif.

A single Y-motif and 52, 16, or 4 molecules of K5, corresponding to L/P ratios of 4, 1.2, or 0.3, respectively, were mixed. MD simulations revealed that K5 stably bound to the Y-motif (Movies S1,S2 and S3) and induced deformation of the Y-motif (Figure 3a). The degree of deformation was evaluated by measuring the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the Y-motif mixed with oligolysine from the Y-motif alone (Movie S4; Figure 3b). Sixteen K5 (L/P 1.2) showed the highest RMSD values, indicating the greatest deformation degree of the Y-motifs.58 The deformation degree at each L/P ratio was generally consistent with the inhibition of condensate formation observed experimentally. We considered that this deformation was caused by the electrostatic attraction between the negatively charged phosphates in the DNA and positively charged lysine residues. This bridged the two duplexes in the Y-motif, resulting in deformation (Movie S2).

We hypothesized that the deformation induced by oligolysine inhibited condensate formation. The number of sticky ends in DNA nanostructures significantly affects condensate formation.16 In particular, three sticky ends are required for condensate formation.59 The formation of bridges between each duplex altered the end-to-end distances and angles (Figures S9 and S10), causing the sticky end positions to overlap. To confirm that this deformation inhibited condensation, a “closed” Y-motif in which two of the three sticky ends were connected by a crossover was designed (Figure 3c). This was intended to mimic a deformed conformation induced by bridging. Microscopic observations confirmed that the closed Y-motifs formed fewer condensates (Figure 3c), supporting our hypothesis.

The differences observed at L/P ratios of 4, 1.2, and 0.3 in K5 were attributed to the specific L/P ratios that most effectively induced Y-motif deformation. The persistence length of unfolded peptides is approximately 0.4 nm,60 while the distance between amino acids is approximately 0.4 nm.61 K5 is regarded as a flexible 2 nm chains. Circular dichroism spectra showed that the oligolysine adopted random coil conformations under buffer conditions (Figure S11). With a small amount of K5, the probability that K5 bound to one Y-motif duplex would also bind and bridge another duplex was low due to the short length of K5 (Movie S1). In the case of excess K5, the binding of multiple K5 to Y-motif duplexes reduced the likelihood of bridging between helices, as K5 already bound to one duplex can hinder the electrostatic interactions required for the bridging. Thus, the most effective deformation of the Y-motif may occur within a specific L/P ratio range.

To evaluate the effect of residue number on deformation (Figures 3d and S9), a single Y-motif and four K5 molecules, two K10 molecules, or one K20 molecule were mixed in the calculation space, corresponding to the L/P 0.3 condition. Although the same L/P ratio was applied for all conditions, MD simulations showed that a higher residue number resulted in larger RMSD values (Figure 3b). Notably, a single K20 molecule caused deformation (Figure S10). Oligolysines with more residues are longer and carry more positive local charges, making them more likely to engage in bridging between the two duplexes (Movie S3). However, when an L/P of 1.2 was applied for all residue numbers, the opposite effect was observed, with larger residue numbers exhibiting smaller RMSD values (Figure 3d), representing a lower degree of deformation. As discussed above, oligolysines with larger residue numbers bound to the Y-motif resulted in more positive charges locally, which tended to induce intramolecular electrostatic repulsion between lysine residues bound to the Y-motif, as in the difference between L/P 4 and 1.2 for K5 (Figure 3b). Thus, the L/P ratio that efficiently induced deformation varied based on the number of residues. Although the Y-motif size differed from that used experimentally, these MD simulation results representing the deformation of the Y-motifs at different L/P ratios and residue numbers were relatively consistent with the observed trends, suggesting that deformation is a dominant factor in condensate inhibition.

Longer oligolysines under the same L/P ratio enhanced electrostatically driven condensate formation (Figure 2d). To investigate this phenomenon, we constructed coarse-grained (CG) models of the SE-less Y-motif and oligolysines, which simplify molecular representations, reducing computational costs and enabling efficient analysis of intermolecular interactions. Similar to the all-atom model, the DNA strands were shortened, but the structural deformation of the motif was not accounted for. In the CG-MD simulations, two SE-less Y-motifs were mixed with K5, K10, or K20 at an L/P ratio of 1.1 (Figure 3e). Oligolysines were bound to the surface of the SE-less Y-motifs, similar to the all-atom MD simulation. Additionally, only K20 connected two motifs (Figure 3e).

To reveal the effects of residue number on the motif connection, the free residues (no interaction with the DNA backbone) in oligolysines bound to the SE-less Y-motifs were measured. Approximately 30% of their residues remained unbound regardless of whether K5, K10, or K20 was used (Figure 3f). Hence, the longer oligolysines had more free residues capable of interacting with other DNA backbones, including those from other motifs. These unbound residues in longer oligolysines increased the likelihood of interacting with another Y-motif. Consistent with this, previous reports have shown that longer oligolysines or PLL can electrostatically induce DNA condensation at lower concentrations than their shorter counterparts.62,63

3.3. Effect of Oligolysine on Sequence-Specific Interactions

Although condensate formation was enhanced at certain L/P ratios, cationic oligomers may inhibit sequence-specific hybridization due to nonspecific electrostatic interactions. Therefore, by mixing Y-motifs and K5 with orthogonal Y-motifs (orthY-motifs; Figure 4), which have noncomplementary sequences to the Y-motif, we verified that the DNA condensate retained its sequence-specificity. The thermodynamic parameters of the orthY-motif’s sticky-end hybridization were similar to those of the Y-motif. The orthY- motifs were labeled with Alexa405 to distinguish them from the Y-motifs. The Y- and orthY-motifs individually self-assembled into two types of DNA condensates (green and blue condensates; Figure 4a), as previously reported.16,64

Figure 4.

Confirmation of sequence specificity in DNA condensates. (a) Schematics of sequence-specific self-assembly of the Y- and orthogonal Y-motifs (orthY-motifs) (left); fluorescence microscopic image representing the sequence-specific formation of two types of DNA condensates (right). (b) Fluorescence microscopic images representing the two types of DNA condensates formed with K5 at an L/P of 3.3 and 1.8. (c) Pearson correlation coefficients between blue and green signals in the images. (d) Magnified microscopic images of DNA condensates with K5 at an L/P of 3.3 and 1.8. Scale bars: 10 μm in (a) and (d), 20 μm in (b).

When K5 was mixed to obtain an L/P of 3.3 or 1.8, the Y and orthY-motifs formed two types of condensates (Figure 4b). The intensity ratio analysis suggested that condensate formation was enhanced under both L/P conditions (Figure S12). However, microscopy revealed several overlapping regions of blue and green fluorescence at L/P 3.3 (Figure 4b, left), indicating colocalization. The Pearson correlation coefficients (PCCs) of only the motifs and L/P 1.8 were −0.1 and 0.1, respectively, whereas the PCC for L/P 3.3 was 0.6 (Figure 4c). Imaging at a higher magnification revealed that the two condensates were adhered at L/P 3.3, and each was hemispherical (Figure 4d). This resulted in large complexes comprising two different condensates (Figure S13). While we primarily focused on K5, stronger connecting effects were observed with K10 and K20, leading to the complete mixing of Y- and orthY-motifs (Figure S14). Two types of Y-motifs with noncomplementary sequences can be connected by a cross-linker DNA nanostructure that hybridizes to the two Y-motifs.16,65 A small amount of cross-linker induced the partial attachment of two types of DNA condensates, each forming a hemisphere. Oligolysine may have bridged the Y- and orthY- motifs by electrostatic interactions, leading to the complex formation of the Y- and orthY-motifs. These small amounts of complex nanostructures may act as cross-linkers, resulting in the attachment of two condensates.

4. Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that, depending on the L/P ratio and residue numbers, oligolysines with 5, 10, and 20 residues exert opposing effects, enhancing and inhibiting DNA condensate formation. The enhancement occurs due to a decrease in the electrostatic repulsion of DNA by cationic lysines. The enhancement mechanism varies depending on the residue number and L/P ratio, whether sticky end-based or electrostatic interaction-based. Meanwhile, the inhibitory effect is likely due to Y-motif deformation caused by the interaction between the Y-motif and oligolysines. More lysine residues tend to induce Y-motif deformation. The sequence-specific formation of DNA condensates with 5-residue oligolysines is retained despite oligolysine enhancing condensate formation via electrostatic interactions. Greater oligolysines may induce complex formation of Y- and orthY-motifs, leading to the partial attachment of the two condensate.

Lysine and arginine (natural cationic amino acids) interact differently with double-stranded DNA.66 To determine whether the results in this study are oligolysine-specific, the effect of oligoarginine peptides on DNA condensate formation merits further investigation. Herein, we have focused exclusively on cationic oligopeptides. Meanwhile, amino acids exhibit high variation with versatile interactions, such as hydrophobic and π-interactions, which may interact with DNA bases. Investigating the effects of oligopeptides with hydrophobic or aromatic residues, including leucine, phenylalanine, and tyrosine, on DNA condensate formation can enhance the understanding of combining DNA nanostructures and peptides.

Peptides form condensates and their properties can be altered by their amino acid sequences.10 As DNA-binding peptides can specifically interact with DNA depending on their base sequences,67,68 the association of the designed DNA nanostructures and peptides allows for the construction of hybrid molecular condensates based on base and amino acid sequences. Additionally, peptides serve as functional molecules in living cells. Thus, combining DNA programmability with peptide functionality can lead to the creation of highly functional and programmable biomolecular condensates. These hybrid condensates may offer a new platform for designing artificial organelles for synthetic cells. Hence, this study provides fundamental insights into the formation of hybrid condensates using designed DNA nanostructures and peptides.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Dr. Hiroshi Sakamoto for his contribution to peptide synthesis and Mr. Tomoichiro Kusumoto and Mr. Uemura Shota for their technical assistance with peptide analysis. This work was supported in part by MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI (grant numbers JP20H05970, JP20K19918, JP23K17860, JP24H00070, JP24K03034, and JP24H01152 to Y.S., JP23H01336 and JP23H04396 to T.M., and JP21H05887 and JP23H04427 to J.T.) and JST FOREST Program (JPMJFR2344 to Y.S. and JPMJFR212H to T.M.).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.5c01928.

DNA sequences; summary of all-atom simulation systems; summary of coarse-grained simulation systems; MALDI-TOF MS spectra of K5, K10, and K20; microscopic images of DNA condensates formed without oligolysines, visualized at different temperatures; confocal microscope images of DNA condensates and dye-labeled K5-Cys; representative fluorescence microscopic images of mixtures of Y-motifs without sticky ends and K5 oligolysines under 15, 150, and 1500 mM NaCl concentration; representative fluorescence microscopic images of DNA condensates formed with K5 at various L/P ratios; representative fluorescence microscopic images of DNA condensates formed with K10 at various L/P ratios; representative fluorescence microscopic images of DNA condensates formed with K20 at various L/P ratios; size comparison of the DNA condensates at different L/P ratios with the K5 oligolysine; snapshots of MD simulation for the Y-motif and oligolysines of K10 and K20 at an L/P ratio of 1.2 and 0.3; snapshots of MD simulation with or without oligolysines at an l/p ratio of 0.3, representing the end-to-end distance of the three duplexes in the Y-motif; circular dichroism spectra of oligolysines; the intensity ratio of fluorescence microscope images of two types of DNA condensates assembled from Y- and orthY-motifs; adhesion of two types of DNA condensates at an L/P of 3.3; representative fluorescence microscopic images representing the complete mixing of Y- and orthY-motifs in the condensates (PDF)

All-atom MD simulation in the Y-motif (green) with four K5 (purple). Only oligolysines attached to the Y-motif are shown (MP4)

All-atom MD simulation in the Y-motif with sixteen K5 (MP4)

All-atom MD simulation in the Y-motif with one K20 (MP4)

All-atom MD simulation in the Y-motif without oligolysines (MP4)

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.S.; Methodology: T. M., Y.S.; Investigation: O.H., J.K., Y.O., M.S., T.M; Visualization: O.H., J.K., Y.O., T.M., Y.S.; Writing—Original Draft: O.H. T.M., T.J.; Writing—Review & Editing: O.H., T.M., Y.O., T.J., Y.S; Funding acquisition: J.T., T.M., Y.S. There are no conflicts to declare.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Shin Y.; Brangwynne C. P. Liquid phase condensation in cell physiology and disease. Science 2017, 357 (6357), eaaf4382 10.1126/science.aaf4382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Ji X.; Li P.; Liu C.; Lou J.; Wang Z.; Wen W.; Xiao Y.; Zhang M.; Zhu X. Liquid-liquid phase separation in biology: mechanisms, physiological functions and human diseases. Sci. China:Life Sci. 2020, 63 (7), 953–985. 10.1007/s11427-020-1702-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banani S. F.; Lee H. O.; Hyman A. A.; Rosen M. K. Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18 (5), 285–298. 10.1038/nrm.2017.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Choi J. M.; Holehouse A. S.; Lee H. O.; Zhang X.; Jahnel M.; Maharana S.; Lemaitre R.; Pozniakovsky A.; Drechsel D.; Poser I.; Pappu R. V.; Alberti S.; Hyman A. A. A Molecular Grammar Governing the Driving Forces for Phase Separation of Prion-like RNA Binding Proteins. Cell 2018, 174 (3), 688–699 e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feric M.; Vaidya N.; Harmon T. S.; Mitrea D. M.; Zhu L.; Richardson T. M.; Kriwacki R. W.; Pappu R. V.; Brangwynne C. P. Coexisting Liquid Phases Underlie Nucleolar Subcompartments. Cell 2016, 165 (7), 1686–1697. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson A. G.; Elnatan D.; Keenen M. M.; Trnka M. J.; Johnston J. B.; Burlingame A. L.; Agard D. A.; Redding S.; Narlikar G. J. Liquid droplet formation by HP1alpha suggests a role for phase separation in heterochromatin. Nature 2017, 547 (7662), 236–240. 10.1038/nature22822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A.; Vale R. D. RNA phase transitions in repeat expansion disorders. Nature 2017, 546 (7657), 243–247. 10.1038/nature22386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima K. K.; Vibhute M. A.; Spruijt E. Biomolecular Chemistry in Liquid Phase Separated Compartments. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019, 6, 21. 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L. W.; Lytle T. K.; Radhakrishna M.; Madinya J. J.; Velez J.; Sing C. E.; Perry S. L. Sequence and entropy-based control of complex coacervates. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8 (1), 1273. 10.1038/s41467-017-01249-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshareedah I.; Moosa M. M.; Pham M.; Potoyan D. A.; Banerjee P. R. Programmable viscoelasticity in protein-RNA condensates with disordered sticker-spacer polypeptides. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12 (1), 6620. 10.1038/s41467-021-26733-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster B. S.; Reed E. H.; Parthasarathy R.; Jahnke C. N.; Caldwell R. M.; Bermudez J. G.; Ramage H.; Good M. C.; Hammer D. A. Controllable protein phase separation and modular recruitment to form responsive membraneless organelles. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9 (1), 2985. 10.1038/s41467-018-05403-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y.; Takinoue M. Pioneering artificial cell-like structures with DNA nanotechnology-based liquid-liquid phase separation. Biophys. Physicobiol. 2024, 21 (1), e210010 10.2142/biophysico.bppb-v21.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udono H.; Gong J.; Sato Y.; Takinoue M. DNA Droplets: Intelligent, Dynamic Fluid. Adv. Biol. 2023, 7 (3), e2200180 10.1002/adbi.202200180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman N. C. Nucleic acid junctions and lattices. J. Theor. Biol. 1982, 99 (2), 237–247. 10.1016/0022-5193(82)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Tseng Y. D.; Kwon S. Y.; D’Espaux L.; Bunch J. S.; McEuen P. L.; Luo D. Controlled assembly of dendrimer-like DNA. Nat. Mater. 2004, 3 (1), 38–42. 10.1038/nmat1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y.; Sakamoto T.; Takinoue M. Sequence-based engineering of dynamic functions of micrometer-sized DNA droplets. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6 (23), eaba3471 10.1126/sciadv.aba3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biffi S.; Cerbino R.; Bomboi F.; Paraboschi E. M.; Asselta R.; Sciortino F.; Bellini T. Phase behavior and critical activated dynamics of limited-valence DNA nanostars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110 (39), 15633–15637. 10.1073/pnas.1304632110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon B. J.; Nguyen D. T.; Abraham G. R.; Conrad N.; Fygenson D. K.; Saleh O. A. Salt-dependent properties of a coacervate-like, self-assembled DNA liquid. Soft Matter 2018, 14 (34), 7009–7015. 10.1039/C8SM01085D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen D. T.; Saleh O. A. Tuning phase and aging of DNA hydrogels through molecular design. Soft Matter 2017, 13 (32), 5421–5427. 10.1039/C7SM00557A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y.; Takinoue M. Sequence-dependent fusion dynamics and physical properties of DNA droplets. Nanoscale. Adv. 2023, 5 (7), 1919–1925. 10.1039/D3NA00073G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S.; Osmanovic D.; Dizani M.; Klocke M. A.; Franco E. Dynamic control of DNA condensation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15 (1), 1915. 10.1038/s41467-024-46266-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do S.; Lee C.; Lee T.; Kim D. N.; Shin Y. Engineering DNA-based synthetic condensates with programmable material properties, compositions, and functionalities. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8 (41), eabj1771 10.1126/sciadv.abj1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura K.; Masumoto K.; Igami Y.; Fujioka T.; Kimizuka N. In situ observation of spherical DNA assembly in water and the controlled release of bound dyes. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8 (9), 2726–2732. 10.1021/bm070357w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh O. A.; Jeon B. J.; Liedl T. Enzymatic degradation of liquid droplets of DNA is modulated near the phase boundary. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117 (28), 16160–16166. 10.1073/pnas.2001654117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S.; Osmanovic D.; Klocke M. A.; Franco E. The Growth Rate of DNA Condensate Droplets Increases with the Size of Participating Subunits. ACS Nano 2022, 16 (8), 11842–11851. 10.1021/acsnano.2c00084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham G. R.; Chaderjian A. S.; N Nguyen A. B.; Wilken S.; Saleh O. A. Nucleic acid liquids. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2024, 87 (6), 066601. 10.1088/1361-6633/ad4662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T.; Do S.; Lee J. G.; Kim D. N.; Shin Y. The flexibility-based modulation of DNA nanostar phase separation. Nanoscale 2021, 13 (41), 17638–17647. 10.1039/D1NR03495B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilken S.; Chaderjian A.; Saleh O. A. Spatial Organization of Phase-Separated DNA Droplets. Phys. Rev. X 2023, 13 (3), 031014. 10.1103/physrevx.13.031014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J.; Walther A. Programmable and Chemically Fueled DNA Coacervates by Transient Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation. Chem. 2020, 6 (12), 3329–3343. 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. M.; Li S.; Tang A. A.; Klocke M. A.; Gobry M. V.; Fabrini G.; Di Michele L.; Rothemund P. W. K.; Franco E. Modular RNA motifs for orthogonal phase separated compartments. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15 (1), 6244. 10.1038/s41467-024-50003-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrini G.; Farag N.; Nuccio S. P.; Li S.; Stewart J. M.; Tang A. A.; McCoy R.; Owens R. M.; Rothemund P. W. K.; Franco E.; Di Antonio M.; Di Michele L. Co-transcriptional production of programmable RNA condensates and synthetic organelles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2024, 19, 1665–1673. 10.1038/s41565-024-01726-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J.; Tsumura N.; Sato Y.; Takinoue M. Computational DNA Droplets Recognizing miRNA Sequence Inputs Based on Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32 (37), 2202322. 10.1002/adfm.202202322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Udono H.; Fan M.; Saito Y.; Ohno H.; Nomura S. M.; Shimizu Y.; Saito H.; Takinoue M. Programmable Computational RNA Droplets Assembled via Kissing-Loop Interaction. ACS Nano 2024, 18 (24), 15477–15486. 10.1021/acsnano.3c12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakya A.; King J. T. DNA Local-Flexibility-Dependent Assembly of Phase-Separated Liquid Droplets. Biophys. J. 2018, 115 (10), 1840–1847. 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieregg J. R.; Lueckheide M.; Marciel A. B.; Leon L.; Bologna A. J.; Rivera J. R.; Tirrell M. V. Oligonucleotide-Peptide Complexes: Phase Control by Hybridization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (5), 1632–1638. 10.1021/jacs.7b03567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia T. Z.; Fraccia T. P. Liquid Crystal Peptide/DNA Coacervates in the Context of Prebiotic Molecular Evolution. Crystals 2020, 10 (11), 964. 10.3390/cryst10110964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fraccia T. P.; Jia T. Z. Liquid Crystal Coacervates Composed of Short Double-Stranded DNA and Cationic Peptides. ACS Nano 2020, 14 (11), 15071–15082. 10.1021/acsnano.0c05083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata M.; Zanchetta G.; Chapman B. D.; Jones C. D.; Cross J. O.; Pindak R.; Bellini T.; Clark N. A. End-to-end stacking and liquid crystal condensation of 6 to 20 base pair DNA duplexes. Science 2007, 318 (5854), 1276–1279. 10.1126/science.1143826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akitaya T.; Seno A.; Nakai T.; Hazemoto N.; Murata S.; Yoshikawa K. Weak interaction induces an ON/OFF switch, whereas strong interaction causes gradual change: folding transition of a long duplex DNA chain by poly-L-lysine. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8 (1), 273–278. 10.1021/bm060634j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira J.; Jelokhani-Niaraki M.; Osada S.; Kato F.; Kodama H. Ion-channel formation assisted by electrostatic interhelical interactions in covalently dimerized amphiphilic helical peptides. Biochemistry 2008, 47 (12), 3705–3714. 10.1021/bi702371e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthis N. J.; Clore G. M. Sequence-specific determination of protein and peptide concentrations by absorbance at 205 nm. Protein Sci. 2013, 22 (6), 851–858. 10.1002/pro.2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolte S.; Cordelieres F. P. A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J. Microsc. 2006, 224 (3), 213–232. 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2006.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J.; Rauscher S.; Nawrocki G.; Ran T.; Feig M.; de Groot B. L.; Grubmuller H.; MacKerell A. D. Jr. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods 2017, 14 (1), 71–73. 10.1038/nmeth.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plimpton S. Fast Parallel Algorithms for Short-Range Molecular Dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 1995, 117 (1), 1–19. 10.1006/jcph.1995.1039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover W. G. Constant-pressure equations of motion. Phys. Rev. A 1986, 34 (3), 2499–2500. 10.1103/PhysRevA.34.2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosé S. A molecular dynamics method for simulations in the canonical ensemble. Mol. Phys. 1984, 52 (2), 255–268. 10.1080/00268978400101201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martyna G. J.; Tobias D. J.; Klein M. L. Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 101 (5), 4177–4189. 10.1063/1.467468. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parrinello M.; Rahman A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981, 52 (12), 7182–7190. 10.1063/1.328693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hockney R. W.; Eastwood J. W.. Computer Simulation Using Particles; Taylor & Francis, Inc: Bristol: Hilger, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Verlet L. Computer ″Experiments″ on Classical Fluids. I. Thermodynamical Properties of Lennard-Jones Molecules. Phys. Rev. 1967, 159 (1), 98–103. 10.1103/PhysRev.159.98. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckaert J.-P.; Ciccotti G.; Berendsen H. J. C. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 1977, 23 (3), 327–341. 10.1016/0021-9991(77)90098-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W.; Dalke A.; Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14 (1), 33–38. 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza P. C. T.; Alessandri R.; Barnoud J.; Thallmair S.; Faustino I.; Grunewald F.; Patmanidis I.; Abdizadeh H.; Bruininks B. M. H.; Wassenaar T. A.; Kroon P. C.; Melcr J.; Nieto V.; Corradi V.; Khan H. M.; Domanski J.; Javanainen M.; Martinez-Seara H.; Reuter N.; Best R. B.; Vattulainen I.; Monticelli L.; Periole X.; Tieleman D. P.; de Vries A. H.; Marrink S. J. Martini 3: a general purpose force field for coarse-grained molecular dynamics. Nat. Methods 2021, 18 (4), 382–388. 10.1038/s41592-021-01098-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periole X.; Cavalli M.; Marrink S. J.; Ceruso M. A. Combining an Elastic Network With a Coarse-Grained Molecular Force Field: Structure, Dynamics, and Intermolecular Recognition. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009, 5 (9), 2531–2543. 10.1021/ct9002114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennell C. J.; Gezelter J. D. Is the Ewald summation still necessary? Pairwise alternatives to the accepted standard for long-range electrostatics. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124 (23), 234104. 10.1063/1.2206581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro J.; Rios-Vera C.; Melo F.; Schuller A. Calculation of accurate interatomic contact surface areas for the quantitative analysis of non-bonded molecular interactions. Bioinformatics 2019, 35 (18), 3499–3501. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira F. C.; Fogg A. G.; Zanoni M. V. Regeneration of poly-L-lysine modified carbon electrodes in the accumulation and cathodic stripping voltammetric determination of the cromoglycate anion. Talanta 2003, 60 (5), 1023–1032. 10.1016/S0039-9140(03)00181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roodhuizen J. A. L.; Hendrikx P.; Hilbers P. A. J.; de Greef T. F. A.; Markvoort A. J. Counterion-Dependent Mechanisms of DNA Origami Nanostructure Stabilization Revealed by Atomistic Molecular Simulation. ACS Nano 2019, 13 (9), 10798–10809. 10.1021/acsnano.9b05650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S.; Dizani M.; Osmanovic D.; Franco E. Light-controlled growth of DNA organelles in synthetic cells. Interface Focus 2023, 13 (5), 20230017. 10.1098/rsfs.2023.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefani D.; Guo C.; Ornago L.; Cabosart D.; El Abbassi M.; Sheves M.; Cahen D.; van der Zant H. S. J. Conformation-dependent charge transport through short peptides. Nanoscale 2021, 13 (5), 3002–3009. 10.1039/D0NR08556A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainavarapu S. R.; Brujic J.; Huang H. H.; Wiita A. P.; Lu H.; Li L.; Walther K. A.; Carrion-Vazquez M.; Li H.; Fernandez J. M. Contour length and refolding rate of a small protein controlled by engineered disulfide bonds. Biophys. J. 2007, 92 (1), 225–233. 10.1529/biophysj.106.091561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayvelt I.; Thomas T.; Thomas T. J. Mechanistic differences in DNA nanoparticle formation in the presence of oligolysines and poly-L-lysine. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8 (2), 477–484. 10.1021/bm0605863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann A.; Richa R.; Ganguli M. DNA condensation by poly-L-lysine at the single molecule level: role of DNA concentration and polymer length. J. Controlled Release 2008, 125 (3), 252–262. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y.; Takinoue M. Capsule-like DNA Hydrogels with Patterns Formed by Lateral Phase Separation of DNA Nanostructures. JACS Au 2022, 2 (1), 159–168. 10.1021/jacsau.1c00450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon B. J.; Nguyen D. T.; Saleh O. A. Sequence-Controlled Adhesion and Microemulsification in a Two-Phase System of DNA Liquid Droplets. J. Phys. Chem. B 2020, 124 (40), 8888–8895. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c06911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin B.; Dans P. D.; Wieczor M.; Villegas N.; Brun-Heath I.; Battistini F.; Terrazas M.; Orozco M. Molecular basis of Arginine and Lysine DNA sequence-dependent thermo-stability modulation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18 (1), e1009749 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo T. A.; Nakata E.; Saimura M.; Kodaki T.; Morii T. A protein adaptor to locate a functional protein dimer on molecular switchboard. Methods 2014, 67 (2), 142–150. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbeck J. J.; Oakley M. G. GCN4 binds with high affinity to DNA sequences containing a single consensus half-site. Biochemistry 2000, 39 (21), 6380–6389. 10.1021/bi992705n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.