Abstract

China is rich in tea germplasm resources. Catechins and their derivatives were analyzed regarding their associations among species and tea-processing suitability using 114 representative Camellia plants. GCG, ECG, EGC, ECG3″Me, and EGCG were revealed as potentially useful markers for identifying different tea species, while three O-methylated catechins may be appropriate markers for determining the tea-processing suitability of oolong tea. A correlation analysis indicated that the EGCG3″Me content was significantly higher in varieties suitable for oolong tea than in varieties suitable for black and green teas. Catechin (C, GC, CG, and GCG) contents were significantly higher in Camellia ptilophylla Chang than in Camellia sinensis var. sinensis, Camellia sinensis var. assamica, and Camellia sinensis var. pubilimba Chang. Furthermore, 14 specific tea tree resources with a high catechin index and high EGCG, GCG, and EGCG3″Me contents were screened. This research enhances our understanding of associations among catechins and tea germplasm resources.

Keywords: Catechins, Derivatives, Germplasm resources, Associations, Camellia plants, Distribution

Chemical compounds studied in this article: Gallic acid (PubChem CID: 370), (+)-gallocatechin (PubChem CID: 65084), (−)-epigallocatechin (PubChem CID: 72277), (+)-catechin (PubChem CID: 9064), (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (PubChem CID: 65064), (−)-epicatechin (PubChem CID: 72276), (−)-gallocatechin gallate (PubChem CID: 5276890), epigallocatechin-3-O-(4″-O-methyl) gallate (PubChem CID: 401129), epigallocatechin-3-O-(3″-O-methyl)-gallate (PubChem CID: 9804842), (−)-epicatechin gallate (PubChem CID: 107905), catechin gallate (PubChem CID: 5276454), epicatechin-3-O-(4″-O-methyl)-gallate (PubChem CID: 467297), epicatechin-3-O-(3″-O-methyl)-gallate (PubChem CID: 467296)

Highlights

-

•

Thirteen catechin components were obtained from 114 Camellia plants.

-

•

Catechins (C, GC, CG, GCG) were significantly higher in Camellia ptilophylla.

-

•

EGCG3″Me was significantly higher in varieties suitable for oolong tea.

-

•

The compositions of catechins were strong associations among the compounds.

-

•

Fourteen specific tea tree resources were screened from 114 Camellia plants.

1. Introduction

Tea [Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze], which is native to southwestern China, belongs to the genus Camellia (Thea (L.) Dyer) of the family Camelliaceae and is an important economic crop cultivated worldwide. On the basis of morphology, tea plants have been divided into three varieties, namely Camellia sinensis var. sinensis (CSS), Camellia sinensis var. assamica (CSA), and Camellia sinensis var. pubilimba Chang (CSP) (Chen et al., 2006). Diverse tea variety resources are important for the future development of tea breeding programs and the tea industry. Tea is rich in natural metabolites, such as catechins, amino acids, and caffeine, which provide tea with a special and high-quality flavor (Xu et al., 2018) as well as health benefits (Khan & Mukhtar, 2018). Catechins, which are the most important secondary metabolites in tea, have a variety of physiological effects (e.g., antioxidant and anticancer), but they have also been associated with decreases in lipid levels as well as weight loss (Xie et al., 2020). Moreover, catechins can also protect tea trees from biotic and abiotic stresses. For example, catechins can limit the stress-inducing and growth-inhibiting effects of the pathogen responsible for tea cake disease (Yuan et al., 2012). Methylated catechins form when the phenolic hydroxyl group on the benzene ring of catechins is replaced by a methyl group, which mainly occurs at the 3″- and 4″-positions of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) (Jin et al., 2023; Liu, Huang, et al., 2023). Compared with EGCG, methylated EGCG is more stable, with higher oral bioavailability and anti-allergic activity (Forester & Lambert, 2015; Maeda-Yamamoto et al., 2004). Therefore, methylated EGCG is potentially useful for developing anti-allergy drugs as well as novel functional tea products (Sano et al., 2011).

Secondary metabolite contents (e.g., catechins and methylated catechins) in tea are affected by external factors, such as light, temperature, water and fertilizer management, and sampling season conditions, but they are also differentially distributed among tea germplasm resources (Ahammed et al., 2023; Raza et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2021). Because of differences in genetic backgrounds, catechins and their derivatives are differentially distributed among Camellia resources, which is an important basis for classifying Camellia resources (Li et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2014; Mozumder et al., 2025). It also influences the suitability of various tea resources for the processing required for different tea types, thereby affecting the utility and economic value of Camellia germplasm resources. For example, tea resources rich in polyphenolic substances are suitable for making black tea, whereas tea resources with a substantial abundance of aromatic compounds are generally processed to produce oolong tea (Li et al., 2022). Hence, there has been considerable interest in research on the secondary metabolites of tea germplasm resources. A previous study revealed variations in the total catechin content among 119 tea resources (Chen & Zhou, 2005). Another study investigated and elucidated the variations and profiles of major catechins in 403 tea germplasm resources from China (Jin et al., 2014). On the basis of research on tea germplasm resources, the distribution of catechins and methylated catechins in different germplasm resources has been preliminarily determined. Notably, CSA species usually have high epicatechin gallate (ECG) and epicatechin (EC) levels and low EGCG and gallocatechin gallate (GCG) levels (Jin et al., 2014), whereas CSS species, especially those suitable for making oolong tea, typically have relatively large amounts of EGCG3″Me (Lv et al., 2014). Various parameters, including the catechin index (CI) and phenol-ammonia ratio, have been used as evaluation criteria for screening tea resources suitable for the production of black and green teas (Cheng, 1983; Jin et al., 2014). Aroma precursors and physical properties of tea have also been used to screen for oolong tea resources as well as for trial production (Li et al., 2022). These findings have greatly promoted the research, development, and utilization of specific tea tree germplasm resources.

A partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) can establish a model for the relationship between metabolite levels and sample categories. By calculating the variable importance in projection (VIP) value, the importance of each metabolite for the classification of each sample group may be determined, thereby assisting in the screening of metabolic markers (usually using VIP ≥1.0 for screening). Metabolites with high VIP scores are usually considered more important for distinguishing different categories than metabolites with low VIP scores (Liu, Li, et al., 2023; Yan et al., 2023). However, there is a wide variety of catechins and their derivatives in tea. Additionally, their distribution patterns in different tea plants and other related Camellia plants as well as their correlation in different species and tea-processing suitability have not been systematically explored. Thus, the present study collected 114 representative Camellia plants, including 101 tea species, five other tea Camellia plants, and eight wild tea resources. The objectives of this study were to establish an analytical method enabling the simultaneous detection of 13 catechins and their derivatives in tea, systematically elucidate the diversity in catechins and their derivatives and their correlations among different Camellia plants, and explore specific germplasm resources in terms of their catechin and catechin derivative contents. The study results may be important for the systematic evaluation, development, and application of tea germplasm resources.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental materials

A total of 114 representative Camellia resources collected from nine tea-producing provinces in China were grown in tea gardens in Guangdong and Hunan provinces using standard management practices (i.e., without special agronomic practices such as fertilization, shading, and intercropping). Their geographic origins and collection sites in China are shown in Fig. S1. Of these samples, 44 were from Xinxing county, Yunfu city, Guangdong province (22° 50′ N, 112° 31′ E), 29 were from Yingde county, Qingyuan city, Guangdong province (24° 10′ N, 113° 22′ E), 20 were from Beihu district, Chenzhou city, Hunan province (25° 47′ N, 112° 55′ E), 14 were from Changsha county, Changsha city, Hunan province (28° 28′ N, 113° 20′ E), and seven were from Chao'an district, Chaozhou city, Guangdong province (23° 57′ N, 116° 38′ E); specific details are provided in Table S1. Mature leaves were collected from Camellia petelotii (Merr.) Sealy and Camellia sinensis var. sinensis ‘Songzhongchengshuye’ as pairs of clamped leaves, whereas one bud and two leaves were collected from the other samples. In general, the number of CSS, CSA, CSP, CP and TOC were 80, 16, 5, 5, and 8, respectively. All collected materials were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C prior to use.

2.2. Chemicals and reference standards

The standard compounds used for detecting and analyzing catechins and their derivatives were gallic acid (purity ≥98 %), epigallocatechin gallate (purity ≥98 %), epicatechin gallate (purity ≥98 %), epigallocatechin (purity ≥98 %), epicatechin (purity ≥98 %), gallocatechin (purity ≥98 %), catechin gallate (purity ≥98 %), catechin (purity ≥98 %), and gallocatechin gallate (purity ≥98 %), which were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd., whereas epigallocatechin-3-O-(3″-O-methyl)-gallate (purity 98 %), epigallocatechin-3-O-(4″-O-methyl) gallate (purity 98 %), epicatechin-3-O-(3″-O-methyl)-gallate (purity 98 %), and epicatechin-3-O-(4″-O-methyl)-gallate (purity 98 %) were purchased from Shanghai ZZBIO Co., Ltd. Chromatography-grade methanol (≥98 %) and acetonitrile (≥98 %) were purchased from Guangzhou Fantao Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., whereas glacial acetic acid (≥98 %) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

2.3. Detection and analysis of catechins and their derivatives

Conditions for detecting and analyzing polyphenols and catechins in tea were optimized according to GB/T 8313–2018 (Wang et al., 2022). Briefly, 0.1 g (weighed accurately to 0.0001 g) uniformly ground fresh tea powder was added to a 2 mL centrifuge tube (placed in liquid nitrogen in a low-temperature environment), after which 1 mL 70 % methanol solution was added prior to an ultrasonic extraction for 20 min in an ice bath. The sample was transferred to a centrifuge (pre-cooled at 4 °C) and centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a 2 mL centrifuge tube and then the extract solution was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane. Caffeine, catechin, O-methylated catechin, and gallic acid were detected using an HPLC analyzer (Alliance, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) equipped with a ZORBAX Eclipse C18 column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm). The injection volume was 10 μL and the column temperature was 40 °C. mobile phase A consisted of distilled water containing 7 % acetonitrile and 2 % glacial acetic acid, whereas mobile phase B comprised acetonitrile and 2 % glacial acetic acid. The linear gradient elution was completed as follows (flow rate of 1 mL/min): 0–4.8 min, 97 % A; 4.81 min, 100 % A; 4.81–19 min, 100 % A; 19.01–21 min, 90 % A; 21.01–31 min, 82 % A; 31–31.01 min, 80 % A; 31.01–33 min, 75 % A; 33.00–33.01 min, 100 % B; 33.01–63 min, 100 % B; 63–63.1 min, 97 % A; and 63.1–93 min, 97 % A. The UV absorption wavelength was 278 nm. A diode array detector was used for the UV spectroscopic characterization. Qualitative and quantitative analyses were conducted on the basis of authentic standards.

2.4. Data processing and analysis

Sample analyses were replicated three times and standard deviations were calculated. All contents were determined relative to fresh weight (FW) and the ratio of EC + ECG (dihydroxylated catechins) to epigallocatechin (EGC) + EGCG (trihydroxylated catechins) was calculated as the catechin index (CI) (Jin et al., 2014). The criteria used to screen for specific tea tree resources, such as those with high EGCG contents (dry weight > 130 mg/g), high GCG contents (dry weight > 40 mg/g), and high EGCG3″Me contents (dry weight > 10 mg/g), were based on those used in previous studies (Li, 2023; Lv et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2022). A PLS-DA was performed as previously described (Liu, Li, et al., 2023) and the results were plotted using an online tool (https://www.omicstudio.co.uk/tool). A principal component analysis (PCA) was completed and a correlation heat map was constructed as previously described (Huang et al., 2024) and the results were plotted using R. Significance was statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 2017 and Microsoft Excel 2016, with differences between two groups determined according to a two-tailed t-test. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to assess the relationship between catechins and their derivatives, with p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 set as the thresholds for significant and highly significant, respectively. All data are expressed herein as the mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Distribution of catechins and their derivatives in different Camellia plants

To analyze the contents of 13 catechins and their derivatives in 114 Camellia plants, an HPLC-based method was developed to simultaneously detect 13 catechins and their derivatives in fresh leaves. The results showed that the method can be used to determine the contents of 13 catechins and their derivatives in 114 Camellia plants on the basis of standards (Fig. S2A) and samples (Fig. S2B & C). The contents of 13 major catechins and their derivatives, namely gallic acid (GA), Catechin (C), EGC, EGCG, EC, ECG, GCG, Catechin gallate (CG), Gallocatechin (GC), epigallocatechin-3-O-(3″-O-methyl)-gallate (EGCG3″Me), epigallocatechin-3-O-(4″-O-methyl) gallate (EGCG4″Me), Epicatechin-3-O-(3″-O-methyl)-gallate (ECG3″Me), and epicatechin-3-O-(4″-O-methyl)-gallate (ECG4″Me), in the 114 Camellia plants were determined and analyzed. Both GC and EC (nongalloylated catechins) were detected in all 114 Camellia plants, but EGCG, EGC, ECG, ECG3″Me, and GA were also commonly detected (more than 95 % of resources). In contrast, GCG, ECG4″Me, and CG were the least commonly detected compounds (less than 25 % of resources) (Table S2).

Differences in the contents of catechins and their derivatives among the 114 Camellia plants were analyzed. The mean total catechin content was 32.61 mg/g FW, ranging from 1.50 to 52.16 mg/g FW (Table S2). Among the 13 catechins and their derivatives, EGCG was the most abundant, with a mean content of 18.70 mg/g FW, followed by EGC, ECG, and EC, with mean contents of 6.06, 4.20, and 1.82 mg/g FW, respectively. The coefficients of variation (CVs) were large for GA, GCG, GC, C, CG, EGCG3″Me, EGCG4″Me, ECG3″Me, and ECG4″Me (Table S2), indicative of the diversity among Chinese tea germplasm resources. Conversely, the CVs were small for EGC, EGCG, ECG, and EC, suggestive of the lowest potential for improvement. In addition, the 114 tea resources screened on the basis of specific criteria included three tea resources with high EGCG contents (‘Taoyuan daye’, ‘Nanjiang’, and ‘Baxian’), two tea resources with high GCG contents [‘Huizhoumaoyecha’ (HZMYC) and ‘Gudongyeshengmaoyecha’ (GDYSMYC)], and six tea resources with high EGCG3″Me contents [‘Songzhongchengshuye’ (SZCSY), ‘Songzhongyouye’ (SZYY), ‘Heyeshuixian’ (HYSX), ‘Xiangchayan No. 8’ (XCY8), ‘Dancong No. 27’, and ‘Wuyedancong’ (WYDC)]. Both HYSX and ‘Xiangchayan No. 12’ (XCY12) accumulated relatively large amounts of four methylated catechins (EGCG3″Me, EGCG4″Me, ECG3″Me, and ECG4″Me). These tea resources may be relevant to future research conducted to comprehensively characterize specific tea tree resources in terms of their metabolites.

Of the 114 Camellia plants examined in this study, 109 (CSS, CSA, CSP, and wild tea) had high EGCG, ECG, and EGC contents, with EGCG detected as the most abundant compound, which is consistent with earlier findings (Jin et al., 2014). The three Camellia ptilophylla Chang (CP) tea resources HZMYC, GDYSMYC, and ‘Renhuamaoyecha’ (RHMYC) were characterized by high levels of GCG, C, and GC, with GCG detected as the most abundant compound, which is in accordance with the results of previous studies (Zheng et al., 2022; Ying et al., 2023.). The CI of fresh tea leaves can be used as an indicator of the final quality of black tea (Kottur et al., 2010; Pang et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2018). In this study (Table S4), the CI value of ‘Yingjiuhongjing’ (YJHJ), ‘Huangyu’ (HY), and ‘Yundaqunti’ (YDQT) exceeded 0.7, making these germplasm resources relevant to studies on the molecular mechanism underlying high CI values among tea trees, but they are also potentially useful as parents in breeding programs attempting to develop tea tree varieties with high CI values and theaflavin contents. In addition, the 80 tea germplasm resources belonging to the CSS group in this study had a low overall CI, similar to the results of previous studies (Jin et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2018). The main methylated catechins are EGCG3″Me, EGCG4″Me, ECG3″Me, and ECG4″Me (Sano et al., 1999). Although EGCG3″Me is the most common methylated catechin, it has been detected in very few tea varieties in China (Lv et al., 2014). Notably, EGCG4″Me-containing tea resources are even rarer (Jin et al., 2022). Among the 114 Camellia plants included in this study, 101 contained detectable amounts of EGCG3″Me, but 32 had very low EGCG3″Me contents (<0.1 mg/g FW). Only seven tea Camellia plants had high EGCG3″Me contents (>2.5 mg/g), including SZCSY from Chaozhou (up to 5 mg/g FW). Both HYSX and XCY12 had high EGCG3″Me, EGCG4″Me, ECG3″Me, and ECG4″Me contents, implying they are valuable materials for investigations on the substantial accumulation of methylated catechins, especially 4″-methylated catechins, and the molecular basis of catechin contents in tea trees. The regulatory mechanism underlying the differential enrichment of EGCG3″Me and EGCG4″Me in different tea germplasm resources was recently preliminarily investigated using tea cultivars with high, medium, and low EGCG3″Me and EGCG4″Me contents, revealing that transcription factors, such as WRKY and MADS, may be involved in the regulation of EGCG3″Me and EGCG4″Me biosynthesis (Liu, Huang, et al., 2023; Luo et al., 2022). The biosynthesis of EGCG3″Me and EGCG4″Me depends on the catalytic activities of specific O-methyltransferases, including CsFAOMT1 (Jin et al., 2023). This finding has greatly facilitated research on the biosynthesis of methylated EGCG in tea trees and the underlying regulatory mechanism.

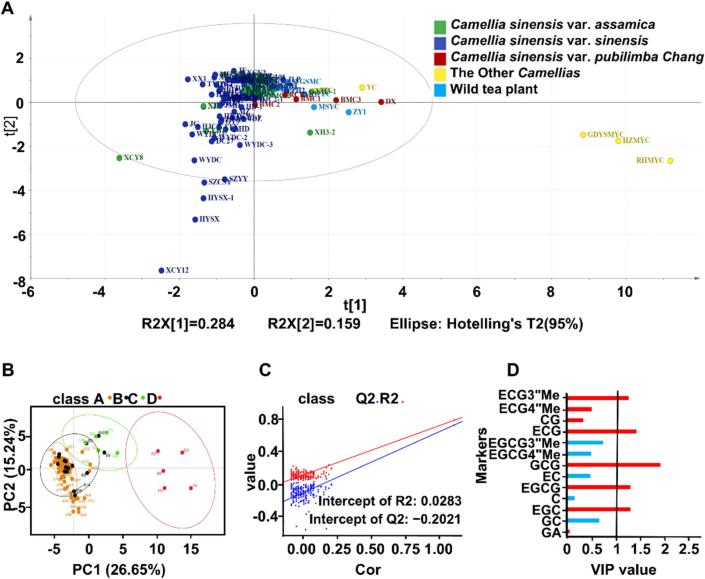

3.2. Cluster analysis of catechins and their derivatives in different germplasm resources

A PCA can decrease the dimensionality of high-dimensional data by extracting the main components of high-dimensional data. On the basis of species–genus relationships, the 114 Camellia plants were divided into the CSS, CSA, CSP, and TOC groups (Table S1). The PCA model was able to clearly separate HZMYC, GDYSMYC, and RHMYC from the TOC group as well as the resources with high EGCG3″Me contents, including SZCSY, SZYY, HYSX, XCY8, and WYDC. Conversely, most of the CSS and CSA resources were not well separated (Fig. 1A). A least squares regression model can clarify the relationship between metabolite contents and sample categories and maximize the differences between taxonomic groups to predict sample categories. Moreover, the variable importance in projection VIP value was calculated to assess the strength of the influence of each metabolite accumulation pattern on the classification of each sample group. This value was also used to screen labeled metabolites (VIP ≥1.0 was usually used as the screening condition). The catechins and their derivatives associated with the differences among species were analyzed by conducting a PLS-DA (Fig. 1B & C), which indicated that CSS (Subgroup A) and CSA (Subgroup B) were not separated, whereas CSP (Subgroup C) and TOC (Subgroup D) were clearly separated from the other two subgroups (Subgroup A & B). This suggests that among the 114 tea Camellia plants, the quality-related composition of CSS and CSA resources was similar, while there were obvious differences between CSP and these two subgroups (CSS and CSA) as well as between TOC and the three other subgroups (CSS, CSA, and CSP). Principal components 1 (PC1) and 2 (PC2) accounted for 26.65 % and 15.24 % of the variability, respectively (Fig. 1B). VIP values, which were calculated according to the PLS-DA model, are commonly used to analyze the correlation between metabolites and sample groups. The following metabolites with a VIP value ≥1 were considered as marker metabolites during the screening process: GCG, ECG, EGCG, EGC, and ECG3″Me (VIP values of 1.94, 1.44, 1.32, 1.32, and 1.28, respectively) (Fig. 1D). Hence, these catechins and their derivatives may be the hallmarks of the differences between species. Previous studies showed that the accumulation of certain secondary metabolites in different genera and specific Camellia plant resources is determined by the genetic background (e.g., low caffeine in Camellia ptilophylla and low EGCG contents in Camellia oleifera as well as high EGCG contents in tea tree cultivars). The abundance of these compounds may serve as an important reference for the taxonomic classification of Camellia plant resources (Li et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2014; Mozumder et al., 2025). The results of the current study are similar to the findings of these earlier studies.

Fig. 1.

Screening of important catechins and derivatives from different Camellia germplasm resources based on principal component analysis (PCA) score plot and partial least square discriminant analysis (PLS-DA).

Screening of important catechins and derivatives from 114 different tea Camellia germplasm resources based on principal component analysis (PCA) score plot and partial least square discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) score plot. (B)Score plot of partial least square discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) plot based on four species including Camellia sinensis var. sinensis (A), Camellia sinensis var. assamica (B), Camellia sinensis var. pubilimba Chang (C) and the other camellias (D). (C) Validation model of PLS-DA with 200 permutation tests (R2 = 0.76, Q2 = 0.70, Intercept R2 = 0.03, Intercept Q2 = −0.20); (D) VIP values of PLS-DA based on four different species. Gallic acid(GA); Gallocatechin (GC); Epigallocatechin (EGC); Catechin (C); Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG); Epicatechin (EC); Gallocatechin gallate (GCG); Epigallocatechin-3-O-(4″-O-methyl) gallate (EGCG4″Me); Epigallocatechin-3-O-(3″-O-methyl)-gallate (EGCG3″Me); Epicatechingallate (ECG); Catechin gallate (CG); Epicatechin-3-O-(4″-O-methyl)-gallate (ECG4″Me); Epicatechin-3-O-(3″-O-methyl)-gallate (ECG3″Me).

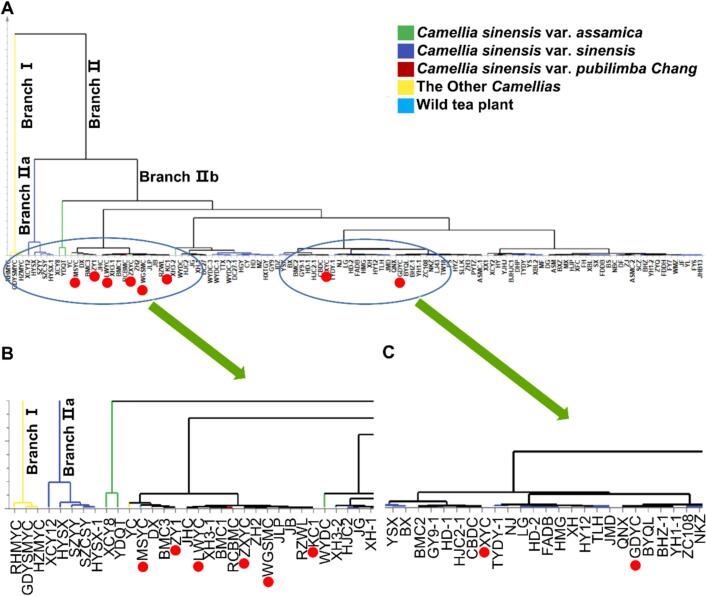

To analyze the classification of the eight wild tea resources, the 114 Camellia plants were clustered and analyzed (Fig. 2) on the basis of the principle that individuals in the same class are highly similar, while individuals in different classes differ substantially. The constructed evolutionary tree was first divided into two large branches (Branch I and II), with branch I containing three copies of CP resources. Branch II was further divided into two large taxa (Branch IIa and IIb), of which branch IIa included five copies of varieties with high EGCG3″Me contents, while branch IIb had all eight copies of wild tea, with Mangshanyecha and Ziya No. 1 clustered in a small branch with Danxia and Baimaocha No. 3; Linwuyecha, Zixingyecha, Wugaishanmicha, and Kucha No. 1 clustered in a small branch with Xianghong No. 3, Baimaocha No. 1, Ruchengbaimaocha, Zhonghuang No. 2, Jiulongpao, Jibai, and Ruanzhiwulong; Xiyecha clustered in a small branch with Baimaocha No. 2, Guanyin No. 9, Huangdan, and Chengbudongcha; and Guidongyecha clustered in a small branch with Qiannianxue, Baiyaqilan, Baihaozao, and other resources. These results suggest that the eight wild tea resources may be tea species, of which Mangshanyecha and Guidongyecha may belong to the CSP and modern CSS groups, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Cluster analysis of 114 different tea Camellia plants based on catechins and their derivatives.

Cluster analysis of 114 different tea Camellia plants based on catechins and their derivatives. (A) Clustering of all 114 accessions tea Camellia plants. (B&C) Clustering of 8 accessions wild type tea plants.

An earlier study demonstrated the utility of a cluster analysis for classifying samples according to the distribution and characteristics of metabolites in different samples (Paradis & Schliep, 2019). Such an analysis is also useful for an attribute-based classification of unknown samples and the elucidation of the correlations and characteristics among samples. Using a similar approach, the clustering characteristics of eight wild tea resources were investigated, which showed that Mangshanyecha and Ziya No. 1 were clustered with CSP resources and had similar catechin and catechin derivative contents. In contrast, Guidongyecha was highly similar to modern CSS resources, which may be relevant to developing and applying these wild resources.

3.3. Correlation analysis of catechins and their derivatives

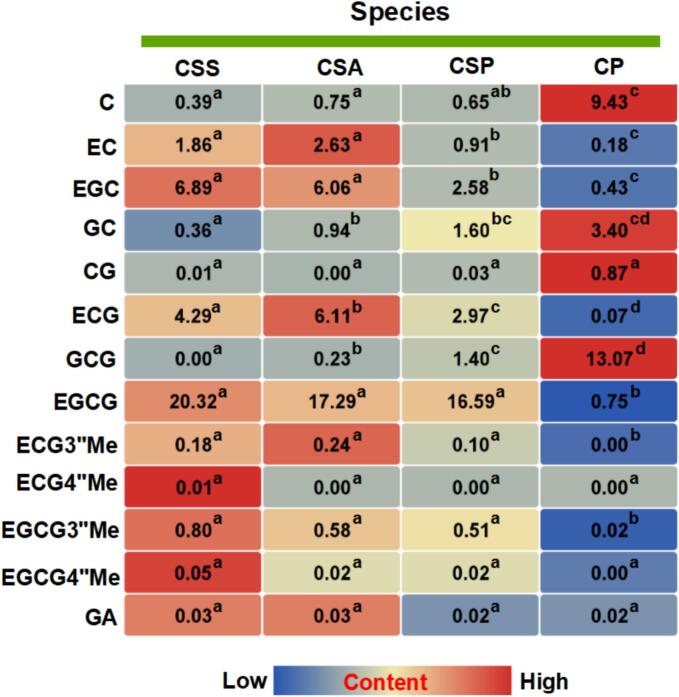

To investigate the associations between catechins and their derivatives in different germplasm resources, 114 tea Camellia plants were categorized into species groups (CSS, CSA, CSP, and CP) (Table S1) and the distributions and associations between catechins and their derivatives in different categories were showed as Fig. 3. An analysis of the compounds in CSS (Group A), CSA (Group B), and CSP (Group C) indicated that the EGCG3″Me, EGCG4″Me, ECG3″Me, ECG4″Me, C, CG EGCG and GA contents did not differ significantly among CSS, CSA, and CSP. In contrast, an examination of nongalloylated catechins revealed the C and GC content was significantly higher in relatively primitive CP than in CSS, CSA and CSP, and the galloylated catechins (GCG, CG) content was also significantly higher in CP than in CSS, CSA and CSP. Furthermore, compared with CSS, CSA, and CSP, CP essentially lacked EC, EGC, ECG, EGCG, EGCG3″Me, EGCG4″Me, ECG3″Me, and ECG4″Me contents.

Fig. 3.

The association of catechins and their derivatives among different species.

The association of catechins and their derivatives among different species. Means distinguished with different letters are significantly different from each other (p ≤ 0.05). Data were expressed as mean (fresh weight) of different species. Notes: CSS means Camellia sinensis var. sinensis; CSA means Camellia sinensis var. assamica; CSP means Camellia sinensis var. pubilimba Chang; CP means Camellia ptilophylla Chang; Gallic acid(GA); Gallocatechin (GC); Epigallocatechin (EGC); Catechin(C); Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG); Epicatechin (EC); Gallocatechin gallate (GCG); Epigallocatechin-3-O-(4″-O-methyl)gallate(EGCG4″Me); Epigallocatechin-3-O-(3″-O-methyl)-gallate (EGCG3″Me); Epicatechingallate (ECG); Catechin gallate(CG); Epicatechin-3-O-(4″-O-methyl)-gallate (ECG4″Me); Epicatechin-3-O-(3″-O-methyl)-gallate (ECG3″Me).

A correlation analysis of 13 catechins and their derivatives in 114 Camellia plants was conducted; correlation coefficients and significant differences are presented in Fig. 4A&B and Table S5, respectively. The correlation between methylated catechins and catechins was explored, which showed that EGCG3″Me was significantly positively correlated with ECG3″Me, EGCG4″Me, ECG4″Me, and EGCG, with correlation coefficients of 0.865, 0.334, 0.211, and 0.195, respectively; EGCG4″Me was significantly positively correlated with ECG4″Me, EGCG3″Me, and ECG3″Me, with correlation coefficients of 0.580, 0.334, and 0.193, respectively; and ECG3″Me was significantly positively correlated with EGCG3″Me, ECG, ECG4″Me, and EGCG4″Me, with correlation coefficients of 0.865, 0.312, 0.199, and 0.193, respectively. None of these four methylated catechins were negatively correlated with any catechin. In addition, among the nongalloylated catechins C, EC, EGC, and GC, there was a significant positive correlation between C and GC. Additionally, C and GC were also significantly positively correlated with the catechin esters CG and GCG, but they were significantly negatively correlated with EGC and EGCG. The catechin esters ECG and EGCG were positively correlated with each other, but they were significantly negatively correlated with nongalloylated catechins, such as C, and the catechin esters GCG and CG.

Fig. 4.

The correlation among catechins and their derivative components.

The correlation among catechins and their derivative components. A: Correlation heat map among catechins and their derivative components. B: The correlation of catechins and their derivative components in the catechins biosynthesis pathway. Note:Gallic acid (GA); Gallocatechin (GC); Epigallocatechin (EGC); Catechin (C); Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG); Epicatechin (EC); Gallocatechin gallate (GCG); Epigallocatechin-3-O-(4″-O-methyl) gallate (EGCG4″Me); Epigallocatechin-3-O-(3″-O-methyl)-gallate (EGCG3″Me); Epicatechingallate (ECG); Catechin gallate (CG); Epicatechin-3-O-(4″-O-methyl)-gallate (ECG4″Me); Epicatechin-3-O-(3″-O-methyl)-gallate (ECG3″Me). Negative value represents negative correlation, Positive value represent positive correlation.

Catechins are common compounds in C. sinensis, but their contents and compositions differ significantly (Li et al., 2022). The main catechins in Camellia oleifera Abel were C, GC, and EC, which was consistent with previous findings (Jiang et al., 2018). The simple catechin EC was significantly more abundant in the relatively primitive CSA than in CSS, while GC was significantly more abundant in the relatively primitive CP, CSA and CSP than in CSS, which was in accordance with published results (Jin et al., 2014; Li et al., 2022; Liu, 1981). This indicates that the content of each catechin in tea is closely related to the genetic background (Fang et al., 2021). In addition, there was no significant correlation among the methylated catechins EGCG3″Me, EGCG4″Me, ECG3″Me, and ECG4″Me in CSS, CSA, and CSP (three large tea plants).

Although the contents and compositions of catechins and their derivatives varied significantly among germplasm resources, there were also strong associations among the compounds, including the positive correlations among all four methylated catechins and some positive correlations with their precursors EGCG and ECG. However, the low correlation between 3″-methylated catechins was lower than that between 3″-methylated catechins and 4″-methylated catechins. The biosynthesis of methylated catechins mainly relies on O-methyltransferases (Zhang et al., 2015). Moreover, specific enzymes catalyze reactions involving 3″- and 4″-methylated catechins (Jin et al., 2023; Liu, Huang, et al., 2023). These earlier studies helped to elucidate the mechanism regulating the intrinsic association between methylated catechins. In addition, of the nongalloylated catechins C, EC, EGC, and GC, there were positive correlations between C and GC as well as between EC and EGC. In terms of their biosynthesis, C and GC are synthesized in reactions catalyzed by LAR, whereas EC and EGC are synthesized in reactions catalyzed by ANR (Zhang et al., 2020). Furthermore, there are similarities between ester-type catechins. For example, in addition to being significantly positively correlated, ECG and EGCG are produced in reactions catalyzed by common enzymes, namely ECGT (Liu et al., 2012) and SCPL (Zhao et al., 2023). However, the correlations between nongalloylated catechins and ester-type catechins are relatively complex. The simple catechin C is significantly negatively correlated with the catechin ester EGCG, but is highly significantly positively correlated with the catechin ester GCG, with a correlation coefficient as high as 0.915. Thus, GCG is closely related to precursors and synthases in its metabolic pathway, but it may also be regulated by other factors. This possibility will need to be investigated more thoroughly.

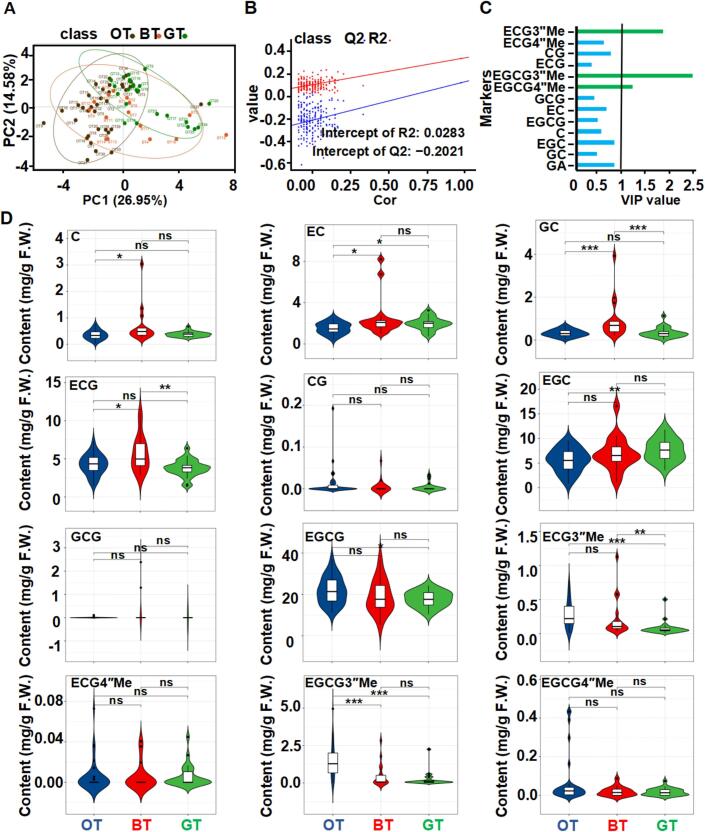

3.4. Correlation analysis between catechins and their derivatives and suitability for tea

To further explore the marker metabolites of different tea types, 17, 32, and 26 resources of representative black, oolong, and green teas with varying quality, respectively, were selected and divided into three groups (Table S1). The catechins and their derivatives related to the diversity in quality among the different teas were analyzed by performing a PLS-DA (Fig. 5A&B). Principal components 1 (PC1) and 2 (PC2) accounted for 26.95 % and 14.58 %. The catechins and their derivatives associated with varietal suitability (VIP ≥1) were EGCG3″Me, ECG3″Me, and EGCG4″Me (VIP values of 2.34, 1.74, and 1.12, respectively) (Fig. 5C). Accordingly, these catechins and their derivatives may be candidate compounds for screening the suitability of different teas.

Fig. 5.

PLS-DA plot and association of catechins and their derivatives based on the tea-processing suitability.

PLS-DA plot and association of catechins and their derivatives based on the tea-processing suitability; (A&B) Validation model of PLS-DA with 200 permutation tests (R2 = 0.35, Q2 = 0.13, Intercept R2 = 0.09, Intercept Q2 = −0.22); (C) VIP values of PLS-DA based on adaptability of different types of tea; (D)The association among catechins and their derivatives based on adaptability of different types of teas. Notes: F.W. means fresh weight; BT means black tea; GT means green tea; OT means oolong tea. Gallic acid (GA); Gallocatechin (GC); Epigallocatechin (EGC); Catechin (C); Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG); Epicatechin (EC); Gallocatechin gallate (GCG); Epigallocatechin-3-O-(4″-O-methyl) gallate (EGCG4″Me); Epigallocatechin-3-O-(3″-O-methyl)-gallate (EGCG3″Me); Epicatechingallate (ECG); Catechin gallate (CG); Epicatechin-3-O-(4″-O-methyl)-gallate (ECG4″Me); Epicatechin-3-O-(3″-O-methyl)-gallate (ECG3″Me). ***. p < 0.001; **. p < 0.01; *. p < 0.05; “ns” mean no significance.

The associations of catechins and their derivatives among different tea varieties were depicted in violin plots (Fig. 5D). The associations of the four methylated catechins among different tea types were analyzed, which showed that the EGCG3″Me content was significantly higher in oolong tea than in black and green teas, whereas the ECG3″Me content was significantly higher in oolong and black teas than in green tea. There were no significant differences between EGCG4″Me and ECG4″Me contents in different tea types. An analysis of the associations among common catechins in different tea types revealed a lack of a significant correlation between CG and GCG in different tea types, but GC and ECG contents were significantly higher in black tea varieties than in green and oolong tea varieties. Moreover, EC was significantly more abundant in green and black tea varieties than in oolong tea varieties, C was significantly more abundant in black tea varieties than in oolong tea varieties, EGC was significantly more abundant in green tea varieties than in oolong tea varieties, and EGCG was significantly more abundant in oolong tea varieties than in green tea varieties. Earlier research indicated CI can be used to evaluate the suitability of a tea variety for the production of black tea, with a high CI value associated with the formation of theaflavin, which was a key quality-related component of black tea (Pang et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2018). Among the 114 Camellia plants analyzed in the current study, YJHJ, HY, and YDQT had the highest CI values (>0.7) (Table S4).

On the basis of an analysis of different tea types, only the EGCG3″Me content was significantly higher in oolong tea varieties than in black and green tea varieties, whereas the ECG3″Me content was significantly higher in oolong tea varieties than in green tea varieties, which were considered by a previous study to be mostly EGCG3″Me-containing oolong tea varieties (Chen et al., 2018). These observations suggest that varieties suitable for producing oolong tea may serve as important references for screening germplasm resources with high EGCG3″Me contents. Although methylated EGCG is biologically active and stable, its biological function in tea plants is unclear. There are reports suggesting that O-methylated flavonoids influence plant stress resistance (Förster et al., 2021), implying that methylated EGCG in tea trees may be useful for developing anti-allergy drugs and new functional tea products, as well as they may also serve as candidate substances for screening for high stress resistance among tea tree resources.

4. Conclusion

In this study, a method for simultaneously detecting 13 catechins and their derivatives in tea was developed and used to comprehensively examine the distribution patterns of all 13 catechins and their derivatives in 114 Camellia plants (Fig. 6A). Of the analyzed compounds, GCG, ECG, EGC, ECG3″Me, and EGCG were revealed to be candidate compounds for classifying different species and genera. Moreover, candidate compounds for classifying different tea types with varying quality were also screened. EGCG3″Me, EGCG4″Me, and ECG3″Me were identified as candidate compounds for assessing the suitability of different tea types. In addition, the associations between catechins and their derivatives in different genera and tea types were thoroughly analyzed. Three specific resources with high CI values, three with high EGCG contents, six with high EGCG3″Me contents, and two with high GCG contents were screened (Fig. 6B). The study findings provide a foundation for future research, development, and use of specific tea germplasm resources.

Fig. 6.

Schematics of the association and distribution of catechins and their derivatives among 114 Camellia plants.

Schematics of the association and distribution of catechins and their derivatives among 114 Camellia plants. A: Distribution and association of catechins and their derivatives; B: Specific tea germplasm resources

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yong Luo: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Jiaming Chen: Investigation, Formal analysis. Jianlong Li: Resources. Linghong Zhou: Resources, Conceptualization. Xiaoyi Wei: Supervision. Jinghua Xue: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32202547), the Guangdong S&T Program (2022B1111230001), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2023JJ30562, 2023JJ50061), the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (2023RC3190) and the Research Foundation of Education Bureau of Hunan Province (23B0783). We thanks to the Tea Research Institute of Hunan Academy of Agricultural Sciences for providing tea plant cultivars.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2025.102461.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Ahammed G.J., Wu Y.X., Wang Y.M., Guo T.M., Shamsy R., Li X. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG): A unique secondary metabolite with diverse roles in plant-environment interaction. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2023;209, Article 105299 doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2023.105299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Yu F.L., Yang Y.J. China Agricultural Science & Technology Press (in Chinese); Beijing: 2006. Germplasm and genetic inprovement of tea plant; pp. 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Zhou Z.X. Variations of main quality components of tea genetic resources [Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze] preserved in the China National Germplasm tea Repository. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 2005;60:31–35. doi: 10.1007/s11130-005-2540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Zhang X., Cheng L., Zheng X., Zhang Z. The evaluation of the quality of Feng Huang oolong teas and their modulatory effect on intestinal microbiota of high-fat diet-induced obesity mice model. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 2018;69:842–856. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2017.1420757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Q.K. Biochemical index of tea productive adaptability: Phenol-ammonia ratio (in Chinese) China Tea. 1983;1:39. [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z.T., Yang W.T., Li C.Y., Li D., Dong J.J., Zhao D.…Liang Y.R. Accumulation pattern of catechins and flavonol glycosides in different varieties and cultivars of tea plant in China. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2021;97, Article 103772 doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2020.103772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forester S.C., Lambert J.D. The catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitor, tolcapone, increases the bioavailability of unmethylated(−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate in mice. Journal of Functional Foods. 2015;17:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förster C., Handrick V., Ding Y., Nakamura Y., Paetz C., Schneider B.…Köllner T.G. Biosynthesis and antifungal activity of fungus-induced O-methylated flavonoids in maize. Plant Physiology. 2021;188:167–190. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiab496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Li Y., Zhou F., Xiao T., Shang B., Niu L.…Zhu M. Insight into the chemical compositions of Anhua dark teas derived from identical tea materials: A multi-omics, electronic sensory, and microbial sequencing analysis. Food Chemistry. 2024;441, Article 138367 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.138367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X.L., Huang K.Y., Zheng G.S., Hou H., Wang P.Q., Jiang H.…Xia T. CsMYB5a and CsMYB5e from Camellia sinensis differentially regulate anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis. Plant Science. 2018;270:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J.Q., Dai W.D., Zhang C.Y., Lin Z., Chen L. Genetic, morphological, and chemical discrepancies between Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze and its close relatives. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2022;108, Article 104417 doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2022.104417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J.Q., Liu Y.F., Ma C.L., Ma J.Q., Hao W.J., Xu Y.X.…Liang C. A novel F3’5’ H allele with 14 bp deletion is associated with high catechin index trait of wild tea plants and has potential use in enhancing tea quality. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2018;66:10470–10478. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b04504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J.Q., Ma J.Q., Ma C.L., Yao M.Z., Chen L. Determination of catechin content in representative Chinese tea germplasms. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2014;62:9436–9441. doi: 10.1021/jf5024559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J.Q., Qu F.R., Huang H., Liu Q.S., Wei M.Y., Zhou Y.…Chen L. Characterization of two O-methyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of O-methylated catechins in tea plant. Nature. Communications. 2023;14, Article 5075 doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-40868-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan N., Mukhtar H. Tea Polyphenols in Promotion of Human Health. Nutrients. 2018;11:Article 39. doi: 10.3390/nu11010039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottur G., Venkatesan S., Senthil Kumar R.S., Murugesan S. Diversity among various forms of catechins and its synthesizing enzyme(phenylalanine ammonia lyase) in relation to quality of black tea(Camellia spp.) Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2010;90:1533–1537. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.L., Xiao Y.Y., Zhou X.C., Liao Y.Y., Wu S.H., Chen J.M.…Zeng L.T. Characterizing the cultivar-specific mechanisms underlying the accumulation of quality-related metabolites in specific Chinese tea (Camellia sinensis) germplasms to diversify tea products. Food Research International. 2022;161, Article 111824 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.Y. Master Thesis of Zhejiang University in China; 2023. Hainan tea plants phylogenetic analysis and specific germplasm resources selection (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Chen Z., Zhang Y., Gao X., Luo W., Li B. Interactions among chemical components of cocoa tea (Camellia ptilophylla Chang), a naturally low caffeine-containing tea species. Food & Function. 2014;5:1175–1185. doi: 10.1039/c3fo60720h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.X. Primitive type of tea plant. Journal of Tea. 1981;4:2–4. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.S., Li J.L., Li H.X., Xue J.H., Wang M., Jian G.T.…Zeng L.T. Differences in the quality of black tea (Camellia sinensis var. Yinghong no. 9) in different seasons and the underlying factors. Food Chemistry-X. 2023;20 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2023.100998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.J., Huang K.L., Ke J.P., Chen C.H., Bao G.H., Wan X.C. Novel Camellia sinensis O-methyltransferase regulated by CsMADSL1 specifically methylates EGCG in cultivar “GZMe4”. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2023;71:6706–6716. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c06031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.J., Gao L.P., Liu L., Yang Q., Liu Z.W., Nie Z.Y.…Xia T. Purification and characterization of a novel galloyltransferase involved in catechin galloylation in the tea plant (Camellia sinensis) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287:44406–44417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.403071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Huang X.X., Song X.F., Wen B.B., Xie N.C., Wang K.B.…Liu Z.H. Identification of a WRKY transcriptional activator from Camellia sinensis that regulates methylated EGCG biosynthesis. Horticulture Research. 2022;9, Article uhac024 doi: 10.1093/hr/uhac024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv H.P., Yang T., Ma C.Y., Wang C.P., Shi J., Zhang Y.…Lin Z. Analysis of naturally occurring 3″-methyl-epigallocatechin gallate in 71 major tea cultivars grown in China and its processing characteristics. Journal of Functional Foods. 2014;7:727–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2013.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda-Yamamoto M., Inagaki N., Kitaura J., Chikumoto T., Kawahara H., Kawakami Y.…Kawakami T. O-methylated catechins from tea leaves inhibit multiple protein kinases in mast cells. Journal of Immunology. 2004;172:4486–4492. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozumder N., Lee J.E., Hong Y.S. A comprehensive understanding of Camellia sinensis tea metabolome: from tea plants to processed teas. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology. 2025 doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-111523-121252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang D.D., Liu Y.F., Sun Y.N., Tian Y.P., Chen L.B. Menghai Huangye, a novel albino tea germplasm with high theanine content and a high catechin index. Plant Science. 2021;311, Article 110997 doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2021.110997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis E., Schliep K. ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:526–528. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza A., Chaoqun C., Luo L., Asghar M.A., Li L., Shoaib N., Yin C. Combined application of organic and chemical fertilizers improved the catechins and flavonoids biosynthesis involved in tea quality. Scientia Horticulturae. 2024;337, Article 113518 doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sano M., Suzuki M., Miyase T., Nakamura Y., Yoshino K., Tachibana H., Maeda-Yamamoto M. 2011. Inhibitory effects of O-methylated catechin derivatives on mouse type-I allergy. Shizuoka: Proceedings of the 2001 International conference on O-CHA (tea) culture and science, SessionIII, health and benefits; pp. 159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Sano M., Suzuki M., Miyase T., Yoshino K., Maeda-Yamamoto M. Novel antiallergic catechin derivatives isolated from oolong tea. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1999;47:1906–1910. doi: 10.1021/jf981114l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Yang J., Li J.L., Zhou X.C., Xiao Y.Y., Liao Y.Y.…Zeng L.T. Effects of temperature and light on quality-related metabolites in tea [Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze] leaves. Food Research International. 2022;161, Article 111882 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.H., Zhu W.F., Cheng X., Lu Z.Q., Liu X.Y., Wan C.K., Liu L.L. The effects of circadian rhythm on catechin accumulation in tea leaves. Beverage Plant Research. 2021;1, Article 8 doi: 10.48130/BPR-2021-0008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L.W., Cai S., Zhao T.S., Li M., Tian Y. Green tea derivative (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) confers protection against ionizing radiation-induced intestinal epithelial cell death both in vitro and in vivo. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2020;161:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.Q., Zhang Y.N., Chen J.X., Wang F., Du Q.Z., Yin J.F. Quantitative analyses of the bitterness and astringency of catechins from green tea. Food Chemsirty. 2018;258:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Q., He D., Walker D.I., Uppal K., Wang X., Orimoloye H.T.…Heck J.E. The neonatal blood spot metabolome in retinoblastoma. EJC Paediatric Oncology. 2023;2, Article 100123 doi: 10.1016/j.ejcped.2023.100123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Chen Z.W., Qiao D.H., Guo Y., Li Y., Liang S.H. Diversity analysis of tea polyphenols and catechins of 115 tea plant germplasms in Guizhou and its screening of specific resource(in Chinese) Acta Agriculturae Boreali-Occidentalis Sinica. 2022;31:1470–1480. doi: 10.7606/j.issn.1004-1389.2022.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ying C.T., Chen J.W., Chen J.H., Zheng P., Zhou C.B., Sun B.M., Liu S.Q. Differential accumulation mechanisms of purine alkaloids and catechins in Camellia ptilophylla, a natural theobromine-rich tea. Beverage Plant Research. 2023;3, Article 15 doi: 10.48130/BPR-2023-0015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L., Wang L.J., Han Z.J., Jiang Y.Z., Zhao L.L., Liu H.…Luo K.M. Molecular cloning and characterization of PtrLAR3, a gene encoding leucoanthocyanidin reductase from Populus trichocarpa, and its constitutive expression enhances fungal resistance in transgenic plants. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2012;63:2513–2524. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.Y., Zhang Y.J., Qiu H.J., Guo Y.F., Wan H.L., Scossa F.…Wen W.W. Genome assembly of wild tea tree DASZ reveals pedigree and selection history of tea varieties. Nature Communications. 2020;11, Article 3719 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17498-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Lv H.P., Ma C.Y., Guo L., Tan J.F., Peng Q.H., Lin Z. Cloning of a caffeoyl-coenzyme a O-methyltransferase from Camellia sinensis and analysis of its catalytic activity. Journal of Zhejiang University Science B. 2015;16:103–112. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1400193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Yao S.B., Zhang X., Wang Z.H., Jiang C.J., Liu Y.J.…Xia T. Flavan-3-ol galloylation-related functional gene cluster and the functional diversification of SCPL paralogs in Camellia sp. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2023;71:488–498. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c06433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X.Q., Dong S.L., Li Z.Y., Lu J.L., Ye J.H., Tao S.K.…Liang Y.R. Variation of major chemical composition in seed-propagated population of wild cocoa tea plant Camellia ptilophylla Chang. Foods. 2022;12:123. doi: 10.3390/foods12010123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.