Abstract

Taurine is an amino acid with several physiological functions and has been shown to be involved in the anti-tumor of human nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) cells. However, the role of taurine metabolism-related genes (TMRGs) in NPC has not been reported. We integrated data from the Genecards, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and Gene Expression Omnibus(GEO) databases to identify differentially expressed genes associated with taurine metabolism in NPC patients. Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG analyses were conducted to investigate the underlying mechanisms. Subsequently, Cox regression and Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression analyses were performed to construct a taurine metabolism-related prognostic signature. Survival, medication sensitivity, and immunological microenvironment evaluations were performed to assess the prognostic utility of the model. Finally, immunohistochemistry (IHC) experiments were performed to validate the model’s prognostic reliability. In addition, we further verified the reliability of our research results through molecular docking and single-cell sequencing. Our prognostic model was based on three pivotal TMRGs (ABCB1, GORASP1, and EZH2). Functional analysis revealed a strong association between TMRGs and miRNAs in cancer. Notably, increased risk scores correlated with worsening tumor malignancy and prognosis. Significant disparities in immune microenvironment, immune checkpoints, and drug sensitivity were observed between the high- and low-risk groups. The protein expression patterns of the selected genes in clinical NPC samples were validated using immunohistochemistry. Molecular docking verified the interaction between these three core genes and taurine, which was further supported by single-cell sequencing showing significant expression variation among different cell clusters in NPC. We had elucidated the functions, therapeutic potential, and prognostic significance of three key genes related to taurine metabolism in NPC through multidimensional research and experimental validation. This research provided valuable insights and potential avenues for improved NPC management.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00726-025-03452-7.

Keywords: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Taurine metabolism, Prognosis, Immune microenvironment, Drug sensitivity prediction, ABCB1, GORASP1

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), an epithelial malignancy originating in the nasopharynx, exhibits a distinct geographic distribution with elevated incidence rates.

in Southeast Asia and Southern China (Huang et al. 2023). The etiology of NPC is multifactorial, involving genetic susceptibility, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, and environmental factors (Renaud et al. 2020). Despite improved survival rates in patients with early-stage disease following advancements in chemoradiation strategies over the past decades, delayed.

diagnosis and advanced disease remain significant challenges (Wang et al. 2022). The 5-year survival.

rate of patients with advanced NPC remains below 40%, with recurrence and distant.

metastasis being the primary contributors to mortality in these patients (Juarez-Vignon Whaley et al. 2023). Consequently, the identification of early diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers is crucial for improving the treatment outcomes of NPC. Taurine, a sulfur-containing amino acid, is the most abundant free amino acid in the human body and exerts diverse biological effects. These effects encompass osmotic regulation, antioxidant activity, immune modulation, neuromodulation, and anti-inflammatory effects (Li et al. 2023; Ahmed et al. 2023; Duszka 2022). Recent studies have established the growth-inhibitory effects of taurine on various cancers and its potential to enhance chemotherapeutic efficacy while mitigating toxic side effects (Baliou et al. 2021). Our previous investigations have demonstrated the inhibitory effects of taurine on NPC cell proliferation and its ability to induce apoptosis both in vitro and in vivo (He et al. 2018, 2019; Okano et al. 2023). However, the relationship between taurine metabolism and the prognosis of NPC remains unexplored. Understanding the association between taurine metabolism and NPC prognosis may facilitate the development of novel metabolism-based cancer therapies. This study aimed to elucidate the mechanism underlying taurine metabolism in NPC and construct a prognostic model based on the key genes associated with this pathway. We hypothesized that this model could refine the therapeutic strategies for NPC. Furthermore, after confirming its prognostic implications, we examined the correlation of the model with immune responses and drug sensitivities, thereby enriching the theoretical framework for NPC treatment.

Results

Identification and enrichment analysis of the taurine metabolism-related DEGs

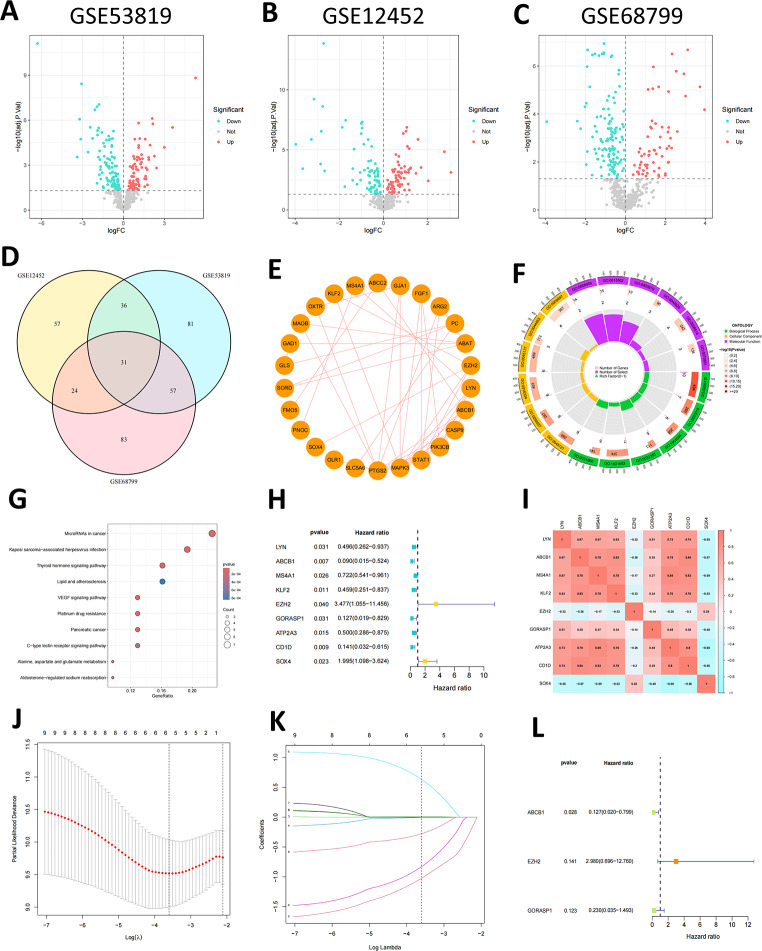

The graphical flow chart outlines the main design of this study (Fig. 1). We used an FDR < 0.05 as the screening criterion and conducted differential analyses on the GSE53819, GSE12452, and GSE68799 datasets, respectively (Fig. 2A-C), and then obtained 31 shared taurine metabolism-related DEGs by intersection (Fig. 2D). The PPI network showed that TMRGs have a wide range of protein interactions (Fig. 2E). Subsequent, GO enrichment analysis revealed that the enriched biological processes.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study

Fig. 2.

Screening of prognostic genes for TMRGs and functional analysis. (A-C) Volcano plot of differentially expressed TMRGs in three GEO-NPC gene sets. (D) A Venn diagram shows 31 shared DEGs obtained through intersection. (E) PPI network of 31-DEGs. (F) GO enrichment analysis. (G) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. (H) Univariate Cox regression analysis to screen 9 prognosis-related TMRGs. (I) Correlation analysis of the 9-TMRGs. (J-K) LASSO analysis of prognosis-related TMRGs. (L) Multifactorial COX regression analysis of 3-TMRGs

(BP) primarily included response to xenobiotic stimulus, vascular process in the circulatory system, response to ketones, response to estradiol, and cellular response to peptides. The cellular components (CC) primarily included membrane raft, membrane microdomain, apical plasma membrane, apical parts of cells, and plasma membrane rafts. Molecular functions (MF) primarily included ABC-type xenobiotic transporter activity, efflux transmembrane transporter activity, RNA polymerase ll core promoter sequence-specific DNA binding, ATPase-coupled transmembrane transporter activity, and organic anion transmembrane transporter activity (Fig. 2F). KEGG analysis suggested that the DEGs were primarily enriched in the miRNAs in cancer, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection, thyroid hormone signaling pathway, lipid and atherosclerosis, VEGF signaling pathway, platinum drug resistance, pancreatic cancer, C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway, alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism, and aldosterone-regulated sodium reabsorption (Fig. 2G).

Construction and validation of the prognostic model

Univariate Cox regression analysis identified nine genes (LYN, ABCB1, MS4A1, KLF2, EZH2, GORASP1, ATP2A3, CD1D, SOX4), which were significantly associated with NPC prognosis (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2H). The results of the co-expression correlation analysis for the nine TMRGs indicated that most of them showed positive correlations (Fig. 2I).

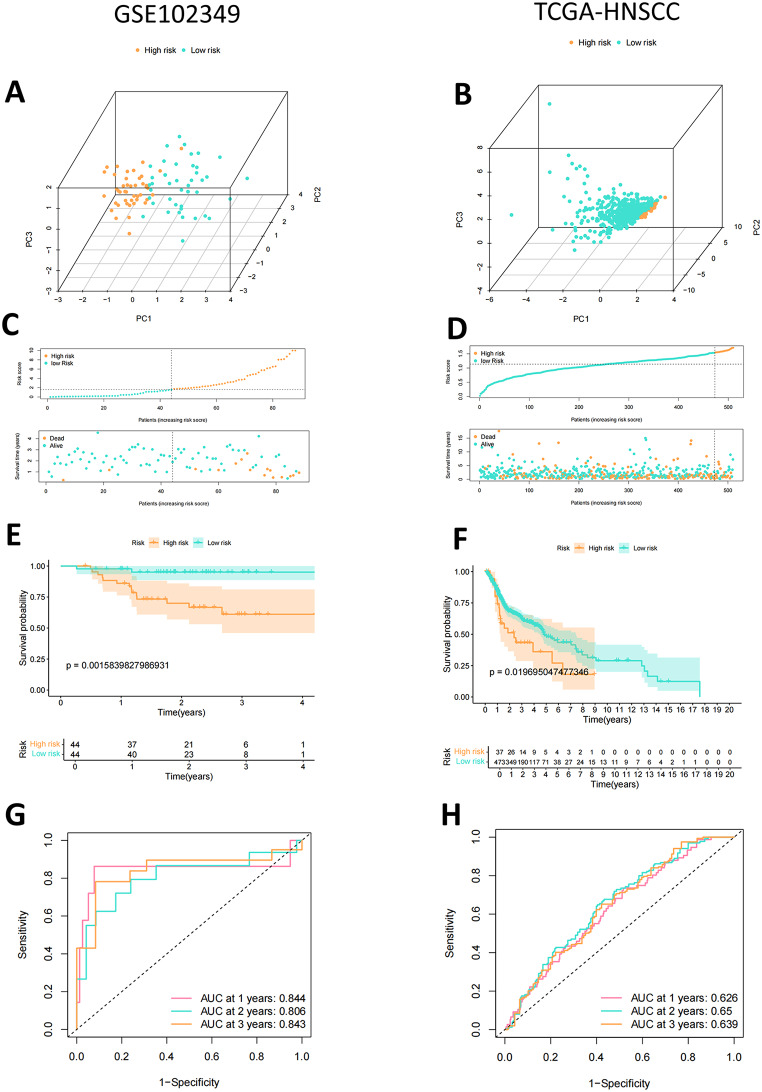

To ensure the stability and clinical applicability of these genes, LASSO Cox regression was applied, further narrowing the list to six genes (ABCB1, KLF2, EZH2, GORASP1, CD1D, SOX4) (Fig. 2J, K). Finally, after multifactorial Cox regression analyses, only three genes (ABCB1, EZH2, and GORASP1) were selected to construct a prognostic signature for NPC (Fig. 2L). In NPC tissues, EZH2 was upregulated, whereas ABCB1 and GORASP1 were downregulated. The lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network diagram based on these three key genes showed that it includes 63 lncRNAs and 13 miRNAs (Supplementary Fig. S1). The risk score was calculated based on their Cox coefficients as follows: Risk score = (-2.06240948810809 × expression level of ABCB1)+ (1.09188225976291 × expression level of EZH2) + (-1.47171691174125 × expression level of GORASP1). Patients with NPC were categorized into high- and low-risk groups based on the median risk score. PCA analysis suggested significant differences between low- and high-risk patients (Fig. 3A). The risk score distribution and survival status plots showed higher mortality in the high-risk group (Fig. 3C), indicating an unfavorable prognosis for these patients. Kaplan–Meier curve analysis revealed significant differences in PFS between the two groups. The low-risk group demonstrated a better PFS than the high-risk group (Fig. 3E). Time-dependent ROC curve analysis indicated that the area under the curve (AUC) values were 0.844, 0.806, and 0.843 for the predicted survival rates at 1, 2, and 3 years, respectively, thus demonstrating robust prognostic power (Fig. 3G). Furthermore, the predictive capacity of the risk score model was validated in the TCGA-HNSCC cohort. NPC patients in the TCGA-HNSCC cohort were categorized into high-and low-risk groups based on the same median risk score value (Fig. 3B). Consistent with the previous results, the high-risk group demonstrated higher mortality (Fig. 3D). The low-risk group demonstrated better OS than the high-risk group (Fig. 3F). The AUC values for 1-year, 2-year and 3-year survival were 0.626, 0.65, and 0.639, respectively (Fig. 3H).

Fig. 3.

Establishment and validation of TMRGs prognostic signature for patients with NPC. (A-B) PCA analysis. (C-D) Risk score distribution and survival status of NPC samples based on the risk score. (E-F) Kaplan-Meier curves of survival between patients in the high- and low-risk group. (G-H) Time-dependent ROC curves of 1-, 2-, and 3-years of NPC patients. (GSE102349: A, C, E, G. TCGA-HNSCC: BDFH)

Immune activity and tumor microenvironment

The CIBERSORT algorithm was applied to the GSE102349 dataset to investigate the relationship between the three-gene prognostic risk model and immune cell infiltration in NPC. Figure 4A illustrates the proportions of the 22 immune cell types across the samples. Significant differences were observed in six immune cell subtypes between the high- and low-risk groups: naive B cells, memory B cells, gamma delta T cells, activated NK cells, activated dendritic cells, and activated mast cells. Specifically, naive B cells, memory B cells, and gamma delta T cells were more abundant in the low-risk group, whereas activated NK cells, activated dendritic cells, and activated mast cells exhibited increased infiltration densities in the high-risk group (Fig. 4B). Spearman correlation analysis showed that risk score was positively related to NK cells activated, T cells follicular helper, Dendritic cells activated, Plasma cells, and Mast cells activated, while negatively associated with T cells regulatory (Tregs), T cells gamma delta, B cells naive, B cells memory (Fig. 4C, D). Using the ssGSEA algorithm, we found higher infiltration levels of most cell types, including activated B cells, activated CD4 + T cells, activated CD8 + T cells, activated dendritic cells, immature B cells, eosinophils, macrophages, neutrophils, and regulatory T cells, in the low-risk group (Fig. 4E). Differences in immune cell infiltration may lead to alterations in immune function, so we performed a ssGSEA score comparison of immune function. Antigen-Presenting Cell Co-Inhibition (APC-co-inhibition), Antigen-Presenting Cell Co-stimulation (APC-co-stimulation), C-C Chemokine Receptor (CCR), Check-point, Cytolyticactivity, human leukocyte antigen (HLA), Inflammation-promoting, major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-class-I), Parainflammation, T cell co-inhibition, T cell co-stimulation, Type I Interferon Response (Type I-IFN-Reponse), Type I Interferon Response (Type-Il-IFN-Reponse) immune function scores were significantly greater in the low-risk group versus high-risk group (Fig. 4F). Further analysis of stromal, immune, and ESTIMATE scores revealed significantly higher values in the low-risk group than in the high-risk group (Fig. 4G). Moreover, the IPS results indicated significant differences in risk scores among major histocompatibility complex IPS (MHC-IPS), effector cells IPS (EC-IPS), suppressor cells IPS (SC-IPS), and checkpoints IPS (CP-IPS) (Fig. 4H). The low-risk group was accompanied by a higher score in MHC_IPS and EC-IPS. Additionally, while the weighted averaged z-scores IPS (AZ-IPS) and the IPS Integrated Profile Score (IPS-IPS) did not reach statistical significance, the trends were consistent with higher values in the low-risk group. These findings imply that patients with low-risk scores may have a more active and intensive immune response, which is associated with a better prognosis. Analysis of immune checkpoint gene expression between the high- and low-risk groups demonstrated higher expression levels of CTLA4, BTLA, and PDCD1 in the low-risk group (Fig. 4I). These findings suggest that the three-gene prognostic risk model may serve as a valuable tool for assessing NPC immunotherapy responses and guiding clinical decision making.

Fig. 4.

Identification of the immune landscape between the two risk groups. (A) CIBERSORT algorithm analysis reveals the abundance of 22 infiltrating immune cell types across two risk groups. (B) The differences of immune cells infiltration between two risk groups in boxplots. (C-D) The correlations between immune cells infiltration and risk scores. (E-F) Box plot of the expression levels of 23 immune cell types 13 immune functions between two risk groups by ssGSEA. (G) Comparisons of the stromal, immune and ESTIMATE score in the two risk groups. (H) Comparisons of the IPS in the two risk groups. (I)The expression levels of immune checkpoints between two risk groups

Drug sensitivity analysis

To investigate the potential clinical utility of TMRGs in precision NPC treatment, the IC50 values were calculated for each patient in both groups. Six representative drugs are presented in Fig. 5 (p < 0.001). Notably, the IC50 values for Gefitinib (Fig. 5A) and ATRA (Fig. 5B) were significantly higher in the high-risk group than those in the low-risk group, suggesting that patients in the high-risk group may not benefit from these drugs. Conversely, Docetaxel (Fig. 5C), Erlotinib (Fig. 5D), Gemcitabine (Fig. 5E), Doxorubicin (Fig. 5F) may be potential candidates for the treatment of high-risk patients.

Fig. 5.

Drug sensitivity analysis between two risk groups. (A) Gefitinib. (B) ATRA. (C) Docetaxel. (D) Erlotinib. (E) Gemcitabine. (F) Doxorubicin

Verification of GORASP1 and ABCB1 protein expression in clinical samples using immunohistochemistry

Given its role in NPC, EZH2 is associated with tumor proliferation and poor prognosis, serving as an independent prognostic biomarker[12–13]. This study focused on verifying ABCB1 and GORASP1 protein expressions in clinical samples. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on tumor tissues from 36 NPC patients, adjacent tissues, and 24 normal nasopharyngeal samples. The results demonstrated that ABCB1 and GORASP1 protein expression was significantly downregulated in NPC tissues compared to normal nasopharyngeal epithelial tissues (Fig. 6A, B p < 0.0001). ROC curve analysis of immunohistochemistry staining scores confirmed the diagnostic potential of ABCB1 (AUC = 0.9079) and GORASP1 (AUC = 0.9482) in NPC (Fig. 6C). Besides, We further analyzed the relationship between the gene IHC score of NPC patients and pathological characteristics (Fig. 6D). The results indicated that ABCB1 has statistical significance in T- stage and Stage (p < 0.05), and it may be related to T- stage. However, the lack of statistical significance in the relationship between the score of GORASP1 IHC and pathological characteristics in NPC patients may be attributed to the small sample size (T: p = 0.3845, N: p = 0.298, Stage: p = 0.1282). These findings, consistent with previous transcriptome differential analyses, validate the prognostic value of ABCB1 and GORASP1 in NPC.

Fig. 6.

Immunohistochemistry analysis (ABCB1, GORASP1). (A) Immunohistochemistry staining of ABCB1, GORASP1 in NPC and normal nasopharyngeal tissue. (B) Protein expression levels of prognostic characteristic genes. (C) The ROC curve of immunohistochemistry staining scores. (D) The relationship between the gene IHC score of NPC patients and pathological characteristics

Molecular Docking of taurine and NPC core target protein

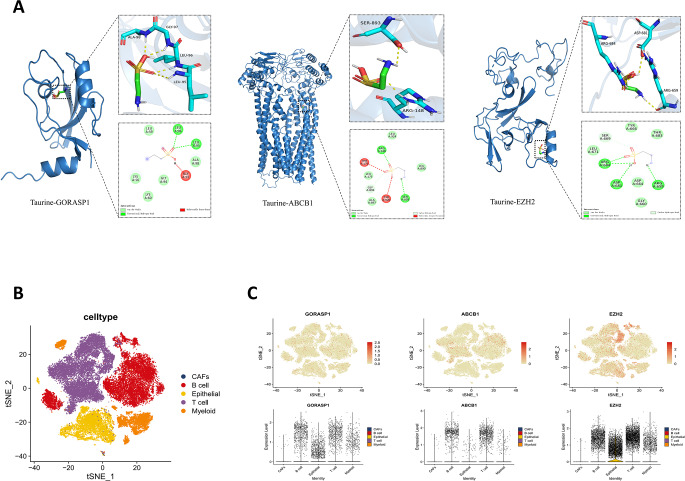

The docking results showed that taurine had low binding energy values with ABCB1(− 4.0), EZH2(− 3.6), and GORASP1(− 3.6), indicating strong affinities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Binding energies of taurine Docking with 3 selected target receptor protein molecules

Figure 7A shows taurine’s interactions with target proteins. It binds to ABCB1, EZH2 and GORASP1, forming hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions. In ABCB1, bonds are with SER893, ARG148 and TYR920; in EZH2, with ARG684, ASP681 and ARG659; in GORASP1, with LEU96 and LEU95. These results offer structural insights into taurine’s molecular interactions with its core genes.

Fig. 7.

Molecular docking and Single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis in NPC. (A) Visualization of docking between taurine and key targets molecules. (B) The t-SNE cell plot of 5 cell clusters. (C) The t-SNE cell plot and violin plot show the distribution and differences of key genes among cell clusters

Single-cell sequencing analysis of potential targets in NPC

In order to fully grasp cell type distribution in NPC and gene expression differences related to tumor development, we analyzed single - cell sequencing data. The t - SNE cell plot revealed five color - coded cell types: B cells, CAFs, epithelial cells, myeloid cells, and T cells (Fig. 7B). Also, GORASP1, ABCB1, and EZH2 expression and distribution were visualized. Using the t - SNE cell plot and violin plots, we clearly saw key gene expression differences across cell types (Fig. 7C). GORASP1 was mostly in B cells, epithelial cells, T cells, and myeloid cells; ABCB1 was mostly in B cells and T cells; EZH2 was mostly in B cells, epithelial cells, myeloid cells, and T cells. These results clarify key gene functions in specific cell types and expression differences among them.

Methods

Data acquisition

We downloaded expression matrices and clinical information for NPC from four Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets, GSE53819 (Bao et al. 2014), GSE12452 (Hsu et al. 2012), GSE68799, and GSE102349 (Zhang et al. 2017) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). To ensure reliable differential analysis, we selected datasets with control group sample sizes of > 10, minimizing potential sampling errors. The GSE102349 dataset included complete progression-free survival (PFS) data for 88 of the 113 patients. No publicly available datasets with prognostic information for patients with NPC were identified in addition to GSE102349. Additionally, a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) dataset from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), comprising 518 tissue samples with comprehensive clinical data, served as a validation cohort. We performed standard processing on the GEO and TCGA datasets, which included the removal of low-quality samples and the normalization of expression values. The Genecards (https://www.genecards.org/) and KEGG Database (https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html) were searched using the keyword “taurine” and 610 genes associated with taurine metabolism were obtained (Table S1).

Identification and enrichment analysis of taurine metabolism-related differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

We used the “limma” package in R to screen for taurine metabolism-related DEGs between tumor samples and adjacent tissues across the three NPC gene sets. The common DEGs were identified by intersecting the results from each dataset. The STRING (version 12.0, https://cn.string-db.org) database was used to construct protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks. The networks were then visualized using Cytoscape software (version 3.6.1).Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO) pathway enrichment analyses were conducted on the identified DEGs using the “cluster profile” R package to investigate the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Construction and validation of the prognostic model

We developed a prognostic model by using a three-step approach. First, univariate analysis revealed that taurine metabolism-related genes (TMRGs) were significantly associated with prognosis. Second, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox regression was conducted using the “glmnet” R package to prevent overfitting. Finally, multivariate Cox regression analysis was conducted to establish an.

optimized risk score model. To build a lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory network using risk score model genes, miRNA-mRNA and miRNA-lncRNA interactions were predicted with Target Scan, miRDB3 and SpongeScan. The predicted miRNAs were intersected, and the network was visualized using the “igraph” package. The risk score was calculated using the following formula: Risk score = expression of gene a × coefficient a + expression of gene b × coefficient b + expression of gene c × coefficient c +. + expression of gene n × coefficient n (Wu et al. 2022). In all cohorts, the samples were divided into low- and high-risk groups based on the risk score (median cut-off value). To evaluate the grouping accuracy, principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted for the risk genes. The PFS between the two risk subgroups was compared using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated using the “survivalROC” R package. The predictive model was externally validated using the HNSCC dataset.

Immune analysis

Differences in immune cell infiltration between the two risk groups were analyzed and compared using single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) and CIBERSORT. Spearman correlation analysis was used to explore the relationships between the risk model and immune status. The ESTIMATE algorithm was used to evaluate the immune score, stromal score, and ESTIMATE score. The difference in response to immunotherapy between the two risk groups was calculated using an immunophenotypic score (IPS). Additionally, the expression levels of immune checkpoint genes were compared between the two risk groups.

Drug sensitivity analysis

Half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for frequently used chemotherapeutic agents were calculated using the “pRRophetic” R package (Geeleher et al. 2014). Drug sensitivities were compared between the risk groups and statistical significance was assessed using the Wilcoxon test.

Immunohistochemistry staining assay

Paraffin-embedded tissue samples were obtained from 36 patients with NPC and 24 individuals with normal nasopharyngeal epithelia. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Guilin Medical University (2021KJJ10). Written informed consent was provided by all participants, including their parents or legal guardians, for subjects under 16 years of age. Paraffin-embedded NPC and corresponding non-cancerous tissues were consecutively sectioned at a thickness of 4 μm and mounted on poly-L-lysine-coated slides. The slides were baked at 80 °C for 30 min in an oven to deparaffinize and rehydrate the tissue sections. Heat-induced antigen retrieval was performed in a pressure cooker with 10 mM Tris-citrate buffer (pH 7.0). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating the slides with 3% hydrogen peroxide at room temperature for 15 min. The slides were then incubated with anti-GORASP1 (bs-7802R, Bioss, Beijing, China) and anti-ABCB1 (#22336-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) at 37 °C for 70 min. After washing with PBS, the slides were incubated with the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (kit-5020, MAIXIN BIOTECH, Fuzhou, China) at room temperature for 20 min, followed by development using a diaminobenzidine (DAB) kit (DAB-1031, MAIXIN BIOTECH, Fuzhou, China). Finally, the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, rinsed with running water, air-dried, and sealed. Two pathologists (Wenqi Luo and Ruwei Mo) evaluated immunostaining for each sample. The staining intensity was graded on a scale of 0 (absent), 1 (weak), 2 (moderate), or 3 (strong). The percentage of positive cells was scored as 0 (0%), 1 (1–25%), 2 (26–50%), 3 (51–75%), or 4 (76–100%). The final immunoreactivity.

score, ranging from 0 to 12, was calculated by multiplying the staining intensity score with the percentage score. Staining was evaluated using a pathological slice scanner (KF-PRO-020; KFBIO Technology Inc., Zhejiang, China).

Molecular Docking of taurine with core targets

To probe Taurine’s binding with core gene proteins, molecular docking was done. Core target protein crystal structures from the RCSB PDB were processed in PyMOL (removing water and ligands), then imported to AutoDock Tools v1.5.7 for hydrogenation, charge and non - polar hydrogen optimization. AutoDock Vina docked them via command - line, with set grid and GA params. PyMOL and Discovery Studio 2019 visualized results, showing Taurine’s binding affinities and mechanisms with key proteins.

Single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis

The scRNA - seq dataset GSE150430 from GEO was analyzed using the Seurat R program. It covers 15 primary NPC tumor samples. PCA evaluated principal component significance between tissues/cells, and t-SNE visualized the datasets. Also, the distribution of ABCB1, GORASP1, EZH2 in cell clusters was explored.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.4.1) and GraphPad Prism (version 5.01). The unpaired t-test was used in immunohistochemistry analysis. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests. (ns, no significantly. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001)

Discussion

In this study, we identified 31 shared taurine metabolism-related DEGs by screening data from the GEO database. Based on these results, we selected three genes to construct a prognostic model for NPC. The predictive efficiency of this model was subsequently validated using TCGA cohort. In both cohorts, patients with NPC classified in the high-risk group exhibited significantly shorter survival times than those in the low-risk group.

Functional analyses revealed that taurine metabolism-related DEGs were significantly enriched in pathways related to xenobiotic stimulus response, membrane raft organization, ABC-type xenobiotic transporter activity, and microRNAs in cancer. These functional annotations suggested that taurine metabolism may influence NPC progression by modulating miRNA-mediated molecular functions. MicroRNAs play dual roles as oncogenes or tumor suppressors in various cancers, influencing not only primary tumor formation but also disease progression and metastasis of the disease(Rhman and Owira 2022). Additionally, miRNAs have been implicated in diverse cellular activities, including immune response, circadian rhythm, and viral replication (Gantier et al. 2007; Calame 2007; Cheng et al. 2007; Jopling et al. 2005). Previous studies have identified miRNAs involved in nasopharyngeal epithelial carcinogenesis, NPC cell apoptosis, proliferation, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, migration, and invasion as well as their association with clinical prognosis (Tan et al. 2015). For instance, EBV miRNAs are involved in the occurrence and development of NPC, affecting tumor cell apoptosis, proliferation, invasion, and metastasis by regulating the expression of both viral and host genes (Vojtechova and Tachezy 2018). MiR-155 stimulates NPC cell proliferation, colony formation, migration, and invasion by downregulating the expression of JMJD1A and BACH1(Zhu et al. 2014). Conversely, some miRNAs serve as metastasis inhibitors; miR-200a inhibits the growth, migration, and invasion of C666-1 cells, and regulates EMT (Xia et al. 2010). MiR-200b exerts tumor-suppressive effects on NPC carcinogenesis by suppressing Notch1 expression (Yang et al. 2013). MiR-9 is commonly downregulated in NPC, and its ectopic expression dramatically inhibits the proliferative, migratory, and invasive capacities of NPC cells both in vitro and in vivo. Low plasma levels of miR-9 were significantly correlated with increased lymphatic invasion and advanced TNM stage (Gao et al. 2013; Lu et al. 2014a, b). The expression changes of these miRNAs correspond to the invasive and metastatic characteristics of NPC, demonstrating their important role in NPC development and supporting our hypothesis.

NPC is highly correlated with EBV infection and is pathologically characterized by the heavy infiltration of immune cells around and within tumor lesions, suggesting the existence of a remarkably complex tumor microenvironment in NPC(Chen et al. 2020). Our analysis revealed significant differences in the abundance of various immune cell populations between the high- and low-risk groups. Specifically, naive B cells, memory B cells, and gamma delta T cells were significantly higher in the low-risk score group, whereas activated NK cells, dendritic cells, and mast cells were negatively correlated with the risk score. Memory B cells play a crucial role in humoral immunity (Mahalingam et al. 2021). In patients with NPC, a reduction in the number of these cells indicates compromised humoral immunity (Liao et al. 2024). Low expression of memory B cells has been associated with poor prognosis in NPC (Zou et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2020). Gamma delta T cells are believed to recognize tissue injury caused by infections, tumors, and chemical and physical agents and have demonstrated capacity against tumors (Zheng et al. 2001). These cells play a role in host defense against NPC and have been shown to kill NPC cells in vitro (Zheng et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2003). Natural killer (NK) cells, as part of the innate immune system, play a crucial role in the response to viral infections and malignant cell transformation. NK cells and their subpopulations significantly contribute to the anti-EBV immune defense during NPC tumorigenesis and exhibit anticancer potential (Li et al. 2024). Dendritic cells play an essential role in immunity and are used in cancer immunotherapy. However, NPC cells have been shown to interfere with dendritic cell maturation and direct cytokine production toward immunosuppressive responses (Chao et al. 2014). Mast cells have been recognized as key orchestrators of anti-tumor immunity and as modulators of the cancer stroma (Lichterman and Reddy 2021). The density of tumor-infiltrating mast cells in NPC increases with the tumor stage, and high tumor-infiltrating mast cell infiltration is associated with poor prognosis (Chen et al. 2015). These findings validate the reliability of our results. Furthermore, we observed that compared to the high-risk group, the low-risk group had higher immune, stromal, and ESTIMATE scores, suggesting that patients with a lower risk profile had a more active and robust immune system. Consequently, it was expected that the high-risk group would have a poorer prognosis. The composition of the TME has been shown to affect the response to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), which leverages the infiltration of immune cells within the tumor to stimulate an effective antitumor immune response (Petitprez et al. 2020). In this study, we identified significant disparities in the expression of multiple immune checkpoints between high- and low-risk patients. These findings imply that stratification based on metabolic risk scores might be a promising biomarker for predicting response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy. However, further studies are required to validate these potential clinical applications.

In our study, three TMRGs (ABCB1, EZH2, and GORASP1) were associated with tumor prognosis, which is consistent with previous findings. ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 1 (ABCB1), belongs to the ATP transporter gene family and is involved in the efflux of various chemotherapeutic drugs (Skinner et al. 2023). The study found that ABCB1 was decrease in NPC (SS and Yao 2008), and Negatively correlated with prognosis(Liang et al. 2025). Polymorphisms in the ABCB1 gene may be responsible for the resistance of NPC cancer stem cells to chemotherapeutic drugs (Chew et al. 2011; Yuan and Zhou 2021). Additionally, the ABCB1 G2677T and C3435T polymorphisms may help predict the response to radiotherapy in patients with NPC (Wang et al. 2007). Curcumin-mediated upregulation of miR-593 results in reduced ABCB1 expression, which may promote radiosensitivity of NPC cells (Fan et al. 2016). Moreover, miR-223-3p enhances the drug sensitivity of breast cancer cells by targeting this gene (Radwan et al. 2024). Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 (EZH2), a histone methyltransferase enzyme, has been linked to the development and progression of various types of cancers, including NPC (Zhong et al. 2013). In the context of NPC, EZH2 has been demonstrated to enhance cell aggressiveness by forming a co-repressor complex with HDAC1, HDAC2, and Snail, which in turn represses the expression of E-cadherin (Tong et al. 2012). Functional studies have revealed that EZH2 upregulation promotes cell proliferation, migration, and tubule formation in endothelial cells, while knockdown of EZH2 suppresses tumor growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis invivo (Lu et al. 2014a, b). Furthermore, overexpression of EZH2 is correlated with increased tumor aggressiveness and poorer prognosis in NPC patients (Tong et al. 2012). Therefore, EZH2 expression may serve as a potential prognostic biomarker for NPC (Alajez et al. 2010). Additionally, EZH2 has been confirmed as a downstream target gene of miR-101-3p, miR-101-3p suppresses tumor progression and increases the sensitivity to cisplatin by inhibiting EZH2 (Wang et al. 2020; Dong et al. 2021; Li et al. 2019). Golgi reassembly stacking protein 1 (GORASP1), is a cis-Golgi protein with roles in Golgi structure, membrane trafficking, and cell signaling. It is cleaved by caspase-3 early in apoptosis, promoting Golgi fragmentation (Cheng et al. 2010). GORASP1 was involved in cancer progression and associated with tumor growth and cell apoptosis (Wang et al. 2019). Our research uncovered a potential link between GORASP1 and miR-27a-3p as well as miR-27b-3p. miR-27a-3p was highly expressed in NPC and associated with tumor progression (Li and Luo 2017). In addition, inhibiting miR-27b-3p could increase sensitivity to chemotherapy (Zhu et al. 2019). These findings strongly supported our study, validating its scientific merit and reliability.

Taurine has been recognized for its qualities, such as antioxidant activity, immune regulation, and anti-tumor properties (Li et al. 2023; Baliou et al. 2021). Research has indicated markedly reduced levels of taurine in the serum and tumors of glioma patients, as well as in those with non-small cell lung cancer and upper tract urothelial carcinomas (Toklu et al. 2023; Hu and Sun 2018; Li et al. 2015). The concentration of taurine in the serum of cancer patients has been found to be intimately connected to their prognosis (Ping et al. 2023; Dong et al. 2017). These observations have suggested that taurine levels may be related to tumor development and progressio.

In this study, we explored the relationships between three core genes and taurine through molecular docking. The docking results showed that taurine had stronger affinity with ABCB1, EZH2, and GORASP1, suggesting a potential functional interaction. This finding was further supported by the work of Elaine F Enright and colleagues, who demonstrated that taurine could bind to ABCB1, thereby reducing the cytotoxicity of cyclosporine A (Enright et al. 2018). Collectively, these observations implied a plausible interaction between taurine and these core genes, which may have had significant biological implications. The tumor microenvironment was closely related to the occurrence, development, and prognosis of NPC (Huang et al. 2023; Renaud et al. 2020; Chen et al. 2020). Through scRNA-seq analysis, we found that the distribution of three core genes (GORASP1, ABCB1, and EZH2) across different cell types had shown significant differences. Based on these findings, we speculated that altered interactions among cell types and distinct expression patterns of core genes may have impacted tumor progression. Future research can further explore the interaction mechanisms of these genes between tumor cells and immune cells, as well as their potential applications in NPC immunotherapy. Additionally, in-depth functional studies of these three genes are also needed, especially their relationship with serum taurine levels in NPC patients, which may offer new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying NPC.

Conclusion

By screening core genes closely related to taurine metabolism, constructing a risk prediction model, and integrating multidimensional approaches such as molecular docking, single-cell sequencing, and experimental validation, we elucidated the pivotal roles of these genes in the progression and prognosis of NPC, as well as the potential clinical application value. Future research will further explore the therapeutic potential of these core genes as targets in NPC, providing new directions for the development of personalized precision medicine strategies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study and performed data analysis and manuscript writing: Z.F., Y.Y., and F.H.; contributed to the data analysis, figure generation and literature search: W.L., J.L., Z.X., L.Z., M.D., D.Z., R.M., X.T., S.Y., and X.H., F.L.; revised the manuscript: N.M., and F.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of guangxi Province, China(NO.2022GXNSFBA035507). & Guangxi Natural Science Foundation Joint Special Project (Guilin Medical University Special) 2025GXNSFHA069022.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Code availability

The authors declare that all codes supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Guilin Medical University (2021KJJ10). Written informed consent was provided by all participants, including their parents or legal guardians, for subjects under 16 years of age.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zhang Feng and Yuhang Yang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ning Ma, Email: maning@suzuka-u.ac.jp.

Feng He, Email: hefeng19880604@outlook.com.

References

- Ahmed K, Choi H-N, Yim J-E (2023) The impact of taurine on obesity-induced diabetes mellitus: mechanisms underlying its effect. Endocrinol Metabolism 38(5):482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alajez N, Shi W, Hui A, Bruce J, Lenarduzzi M, Ito E, Yue S, O’sullivan B, Liu F (2010) Enhancer of Zeste homolog 2 (ezh2) is overexpressed in recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma and is regulated by mir-26a, mir-101, and mir-98. Cell Death Dis 1(10):85–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliou S, Goulielmaki M, Ioannou P, Cheimonidi C, Trougakos IP, Nagl M, Kyriakopoulos AM, Zoumpourlis V (2021) Bromamine t (bat) exerts stronger anti-cancer properties than taurine (tau). Cancers 13(2):182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y, Cao X, Luo D, Sun R, Peng L, Wang L, Yan Y, Zheng L, Xie P, Cao Y et al (2014) Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor signaling is critical in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell growth and metastasis. Cell Cycle 13(12):1958–1969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calame K (2007) Microrna-155 function in B cells. Immunity 27(6):825–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao P-Z, Hsieh M-S, Cheng C-W, Hsu T-J, Lin Y-T, Lai C-H, Liao C-C, Chen W-Y, Leung T-K, Lee F-P et al (2014) Dendritic cells respond to nasopharygeal carcinoma cells through Annexin a2-recognizing dc-sign. Oncotarget 6(1):159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Li X, Zhao F, Huang H, Lu J, Liu X (2015) Distribution and prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating mast cells in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za zhi = chinese. J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 50(4):306–311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-P, Yin J-H, Li W-F, Li H-J, Chen D-P, Zhang C-J, Lv J-W, Wang Y-Q, Li X-M, Li J-Y et al (2020) Single-cell transcriptomics reveals regulators underlying immune cell diversity and immune subtypes associated with prognosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cell Res 30(11):1024–1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H-YM, Papp JW, Varlamova O, Dziema H, Russell B, Curf-man JP, Nakazawa T, Shimizu K, Okamura H, Impey S et al (2007) Microrna modulation of circadian-clock period and entrainment. Neuron 54(5):813–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J, Betin V, Weir H, Shelmani G, Moss D, Lane J (2010) Caspase cleavage of the golgi stacking factor grasp65 is required for fas/cd95-mediated apoptosis. Cell Death Dis 1:e82 Technical report, Epub 2011/03/04 (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew S-C, Singh O, Chen X, Ramasamy RD, Kulkarni T, Lee EJ, Tan E-H, Lim W-T, Chowbay B (2011) The effects of cyp3a4, cyp3a5, abcb1, abcc2, abcg2 and slco1b3 single nucleotide polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of docetaxel in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 67:1471–1478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J-F, Zheng X-Q, Rui H-B (2017) Effect of taurine on immune function in mice with t-cell lymphoma during chemotherapy. Asian Pac J Trop Med 10(11):1090–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Gao Y, Xie T, Liu H, Zhan X, Xu Y (2021) mir-101-3p serves as a tumor suppressor for renal cell carcinoma and inhibits its invasion and metastasis by targeting ezh2. Biomed Res Int 2021(1):9950749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duszka K (2022) Versatile triad alliance: bile acid, taurine and microbiota. Cells 11(15):2337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright EF, Govindarajan K, Darrer R, MacSharry J, Joyce SA, Gahan CG (2018) Gut microbiota-mediated bile acid transformations alter the cellular response to multidrug resistant transporter substrates in vitro: focus on p-glycoprotein. Mol Pharm 15(12):5711–5727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H, Shao M, Huang S, Liu Y, Liu J, Wang Z, Diao J, Liu Y, Tong L, Fan Q (2016) Mir-593 mediates curcumin-induced radiosensitization of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells via mdr1. Oncol Lett 11(6):3729–3734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantier MP, Sadler AJ, Williams BR (2007) Fine-tuning of the innate immune response by Micrornas. Immunol Cell Biol 85(6):458–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F, Zhao Z-L, Zhao W-T, Fan Q-R, Wang S-C, Li J, Zhang Y-Q, Shi J-W, Lin X-L, Yang S et al (2013) mir-9 modulates the expression of interferon-regulated genes and Mhc class i molecules in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 431(3):610–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeleher P, Cox NJ, Huang RS (2014) Clinical drug response can be predicted using baseline gene expression levels and in vitro drug sensitivity in cell lines. Genome Biol 15:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F, Ma N, Midorikawa K, Hiraku Y, Oikawa S, Zhang Z, Huang G, Takeuchi K, Murata M (2018) Taurine exhibits an apoptosis-inducing effect on human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells through Pten/akt pathways in vitro. Amino Acids 50:1749–1758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F, Ma N, Midorikawa K, Hiraku Y, Oikawa S, Mo Y, Zhang Z, Takeuchi K, Murata M (2019) Anti-cancer mechanisms of taurine in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 1155:533–541 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hsu W-L, Tse K-P, Liang S, Chien Y-C, Su W-H, Yu KJ, Cheng Y-J, Tsang N-M, Hsu M-M, Chang K-P et al (2012) Evaluation of human leukocyte antigen-a (hla-a), other non-hla markers on chromosome 6p21 and risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLoS ONE 7(8):e42767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hu J-M, Sun H-T (2018) Serum proton Nmr metabolomics analysis of human lung cancer following microwave ablation. Radiat Oncol 13:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Yao Y, Deng X, Huang Z, Chen Y, Wang Z, Hong H, Huang H, Lin T (2023) Immunotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: current status and prospects. Int J Oncol 63(2):1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang C-F, Huang H-Y, Chen C-H, Chien C-Y, Hsu Y-C, Li C-F, Fang F-M (2012) Enhancer of Zeste homolog 2 overexpression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an independent poor prognosticator that enhances cell growth. Int J Radiation Oncology* Biology* Phys 82(2):597–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopling CL, Yi M, Lancaster AM, Lemon SM, Sarnow P (2005) Modulation of 21 hepatitis C virus Rna abundance by a liver-specific Microrna. Science 309(5740):1577–1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juarez-Vignon Whaley JJ, Afkhami M, Onyshchenko M, Massarelli E, Sampath S, Amini A, Bell D, Villaflor VM (2023) Recurrent/metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma treatment from present to future: where are we and where are we heading? Curr Treat Options Oncol 24(9):1138–1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Luo Z (2017) Dysregulated mir-27a-3p promotes nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell proliferation and migration by targeting mapk10. Oncol Rep 37(5):2679–2687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Tao J, Wei D, Yang X, Lu Z, Deng X, Cheng Y, Gu J, Yang X, Wang Z et al (2015) Serum metabolomic analysis of human upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. Tumor Biology 36:7531–7537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Xie D, Zhang H (2019) Microrna-101-3p advances cisplatin sensitivity in bladder urothelial carcinoma through targeted Silencing ezh2. J Cancer 10(12):2628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Peng Q, Shang J, Dong W, Wu S, Guo X, Xie Z, Chen C (2023) The role of taurine in male reproduction: physiology, pathology and toxicology. Front Endocrinol 14:1017886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Dai W, Kam N-W, Zhang J, Lee VH, Ren X, Kwong DL-W (2024) The role of natural killer cells in the tumor immune microenvironment of Ebv associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancers 16(7):1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, Fang C, Qiu M (2025) The multi-target mechanism of action of selaginella doederleinii Hieron in the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a network Pharmacology and multi-omics analysis. Sci Rep 15(1):159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao L-J, Tsai C-C, Li P-Y, Lee C-Y, Lin S-R, Lai W-Y, Chen I-Y, Chang C-F, Lee J-M, Chiu Y-L (2024) Characterization of unique pattern of immune cell profile in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma through flow cytometry and machine learning. J Cell Mol Med 2228(12):18404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichterman JN, Reddy SM (2021) Mast cells: A new frontier for cancer immunotherapy. Cells 10(6):1270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Xu X, Liu X, Peng Y, Zhang B, Wang L, Luo H, Peng X, Li G, Tian W et al (2014a) Predictive value of mir-9 as a potential biomarker for nasopharyngeal carcinoma metastasis. Br J Cancer 110(2):392–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Zhao F-P, Peng Z, Zhang M-W, Lin S-X, Liang B-J, Zhang B, Liu X, Wang L, Li G et al (2014b) Ezh2 promotes angiogenesis through Inhibition of mir-1/endothelin-1 axis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncotarget 5(22):11319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalingam S, Peter J, Xu Z, Bordoloi D, Ho M, Kalyanaraman VS, Srinivasan A, Muthumani K (2021) Landscape of humoral immune responses against sars-cov-2 in patients with covid-19 disease and the value of antibody testing. Heliyon 7(4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Okano M, He F, Ma N, Kobayashi H, Oikawa S, Nishimura K, Tawara I, Murata M (2023) Taurine induces upregulation of p53 and beclin1 and has antitumor effect in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Acta Histochem 125(1):151978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitprez F, Meylan M, Reyni`es A, Saut`es-Fridman C, Fridman WH (2020) The tumor microenvironment in the response to immune checkpoint Blockade therapies. Front Immunol 11:784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ping Y, Shan J, Liu Y, Liu F, Wang L, Liu Z, Li J, Yue D, Wang L, Chen X et al (2023) Taurine enhances the antitumor efficacy of pd-1 antibody by boosting cd8 + t cell function. Cancer Immunol Immunother 72(4):1015–1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radwan AM, Abosharaf HA, Sharaky M, Abdelmonem R, Effat H (2024) Functional combination of Resveratrol and Tamoxifen to overcome Tamoxifen-resistance in breast cancer cells. Arch Pharm 357(10):2400261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renaud S, Lefebvre A, Mordon S, Moral`es O, Delhem N (2020) Novel therapies boosting t cell immunity in epstein barr virus-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 21(12):4292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhman MA, Owira P (2022) Potential therapeutic applications of Micrornas in cancer diagnosis and treatment: sharpening a double-edged sword? Eur J Pharmacol 932:175210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner KT, Palkar AM, Hong AL (2023) Genetics of abcb1 in cancer. Cancers 15(17):4236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SS D, Yao K (2008) Expression of atp-binding cassette transporter genes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue bao = J South Med Univ 28(3):449–452 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan G, Tang X, Tang F (2015) The role of Micrornas in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Tumor Biology 36:69–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toklu S, Kemerdere R, Kacira T, Gurses MS, Benli Aksungar F, Tanriverdi T (2023) Tissue and plasma free amino acid detection by lc-ms/ms method in high grade glioma patients. J Neurooncol 163(2):293–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z, Cai M, Wang X, Kong L, Mai S, Liu Y, Zhang H, Liao Y, Zheng F, Zhu W et al (2012) Ezh2 supports nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell aggressiveness by forming a co-repressor complex with hdac1/hdac2 and snail to inhibit e-cadherin. Oncogene 31(5):583–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vojtechova Z, Tachezy R (2018) The role of Mirnas in virus-mediated oncogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 19(4):1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, He W, Zhang L, Zhang S, He H, Jiang H (2003) The ex vivo expansion of gamma delta t cells from the peripheral blood of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma and their cytotoxicity to nasopharyngeal carcinoma lines in vitro. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za zhi = journal. Clin Otorhinolaryngol 17(3):155–158 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Chen L, Fan Q, Yan W, Chen Y, Li Q, Yuan Y (2007) Relationship between radiosensitivity of nasopharyngeal carcinoma and mdr1 gene polymorphism. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue bao = J South Med Univ 27(5):580–583 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Chen X, Yuan D, Yi Y, Luo Y (2019) Golgi reassembly and stacking protein 65 downregulation is required for the anti-cancer effect of Dihydromyricetin on human ovarian cancer cells. PLoS ONE 14(11):0225450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Yang X, Li R, Zhang R, Hu D, Zhang Y, Gao L (2020) Lncrna snhg6 inhibits apoptosis by regulating ezh2 expression via the sponging of mir-101-3p in esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther 6(13):11411–11420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Miao J, Huang H, Chen B, Xiao X, Zhu M, Liang Y, Xiao W, Huang S, Peng Y et al (2022) Long-term survivals, toxicities and the role of chemotherapy in early-stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy: a retrospective study with 15-year follow-up. Cancer Res Treatment: Official J Korean Cancer Association 54(1):118–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Sun W, Zhang H (2022) An immune-related prognostic signature for thyroid carcinoma to predict survival and response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Immunol Immunother 71(3):747–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H, Cheung WK, Sze J, Lu G, Jiang S, Yao H, Bian X-W, Poon WS, Kung H-f, Lin MC (2010) mir-200a regulates epithelial-mesenchymal to stemlike transition via zeb2 and β-catenin signaling. J Biol Chem 285(47):36995–37004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Ni W, Lei K (2013) mir-200b suppresses cell growth, migration and invasion by targeting notch1 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem 32(5):1288–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Zhang P, Zhang H, Lu J (2020) Immunocyte infiltration characteristics of gene expression profile in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and clinical significance. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za zhi = chinese. J Cell Mol Immunol 36(12):1069–1075 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan F, Zhou Z-F (2021) Exosomes derived from taxol-resistant nasopharyngeal carcinoma (npc) cells transferred ddx53 to Npc cells and promoted cancer resistance to taxol. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 25(1) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang L, MacIsaac KD, Zhou T, Huang P-Y, Xin C, Dobson JR, Yu K, Chiang DY, Fan Y, Pelletier M et al (2017) Genomic analysis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma reveals tme-based subtypes. Mol Cancer Res 15(12):1722–1732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B, Lam C, Im S, Huang J, Luk W, Lau S, Yau K, Wong C, Yao K, Ng M (2001) Distinct tumour specificity and il-7 requirements of cd56- and cd56 + subsets of human Γδ t cells. Scand J Immunol 53(1):40–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng BJ, Ng SP, Chua DT, Sham JS, Kwong DL, Lam CK, Ng MH (2002) Peripheral Γδ t-cell deficit in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer 99(2):213–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong J, Min L, Huang H, Li L, Li D, Li J, Ma Z, Dai L (2013) Ezh2 regulates the expression of p16 in the nasopharyngeal cancer cells. Technol Cancer Res Treat 12(3):269–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Wang Y, Sun Y, Zheng J, Zhu D (2014) Mir-155 up-regulation by lmp1 Dna contributes to increased nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell proliferation and migration. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 271:1939–1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, He D, Bo H, Liu Z, Xiao M, Xiang L, Zhou J, Liu Y, Liu X, Gong L et al (2019) The mrvi1-as1/atf3 signaling loop sensitizes nasopharyngeal cancer cells to Paclitaxel by regulating the hippo–taz pathway. Oncogene 38(32):6065–6081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Z, Ha Y, Liu S, Huang B (2020) Identification of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and microenvironment-relevant genes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma based on gene expression profiling. Life Sci 263:118620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

The authors declare that all codes supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.