Abstract

Generation-Artificial Intelligence (Gen-AI) is widely used in education and has been shown to improve students’ mathematical abilities. However, dependency on Gen-AI may negatively impact these abilities and should be approached with caution. This study uses Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to determine the relationship between AI literacy, AI trust, AI dependency, and 21st-century skills in preservice mathematics teachers. This research utilizes a self-designed questionnaire with 469 preservice mathematics teachers as respondents. SPSS and AMOS software were used for data analysis. The findings reveal that both AI trust and AI literacy significantly influence preservice mathematics teachers’ dependency on Gen-AI. Furthermore, this dependency on Gen-AI among preservice mathematics teachers has a significant negative effect on their problem-solving ability, critical thinking, creative thinking, collaboration skills, communication skills, and self-confidence. This research provides new information to governments, schools, and teachers that caution should be exercised when attempting to enhance AI literacy and trust in AI among preservice mathematics teachers.

Keywords: Preservice mathematics teacher, ChatGPT, 21st-century skills, Generation-Artificial intelligence

Subject terms: Psychology, Human behaviour

Introduction

In the 21st century, the rapid development of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies has brought revolutionary changes to the education sector, prompting scholars and educators to explore its potential applications in teaching and learning1,2. Generation-Artificial Intelligence (Gen-AI) specifically refers to a class of artificial intelligence models that can use existing data to generate new content reflecting the underlying patterns of real-world data. For example, in education, Gen-AI models are employed to personalize learning experiences by analyzing student performance data and adapting instructional content accordingly. In psychology, these models help in identifying patterns in behavioral data, which can predict mental health trends or therapeutic outcomes. Such applications demonstrate Gen-AI’s capability to reflect complex patterns in diverse domains3. Its four core capabilities—heuristic content generation, dialogue context understanding, sequential task execution, and programming language interpretation—have garnered significant attention4. Heuristic content generation enables the creation of customized educational materials, such as generating unique math problems based on student performance levels. Dialogue context understanding allows Gen-AI to participate in meaningful educational dialogues, adapting its responses based on the context of student inquiries, which can enhance interactive learning platforms. Sequential task execution supports the management of step-by-step learning activities, aiding in the design of structured educational programs that can automatically adjust to the pacing of the student. Lastly, programming language interpretation can facilitate learning in computer science by interpreting and providing feedback on students’ code, thereby supporting hands-on programming education. These capabilities not only highlight Gen-AI’s versatility but also underscore its transformative potential in reshaping educational practices5. This is particularly promising in the realm of mathematics education, where it is expected to provide innovative teaching support and professional development models.

Preservice mathematics students play a crucial role in shaping the future of mathematics education. Their proficiency in applying AI technologies is essential for adapting to innovative educational models and ensuring high standards of educational quality6. Research indicates that Gen-AI models, which leverage vast databases, can provide comprehensive teaching support. This support encompasses various educational domains such as instructional design, classroom simulation, assignment creation, personalized supervision, and ongoing diagnostic assessment7. By optimizing teaching strategies, this technology enhances instructional effectiveness8,9. Furthermore, Gen-AI models assist in organizing educational materials and reducing repetitive tasks, thereby decreasing teachers’ workload and providing immediate learning support to students10,11.

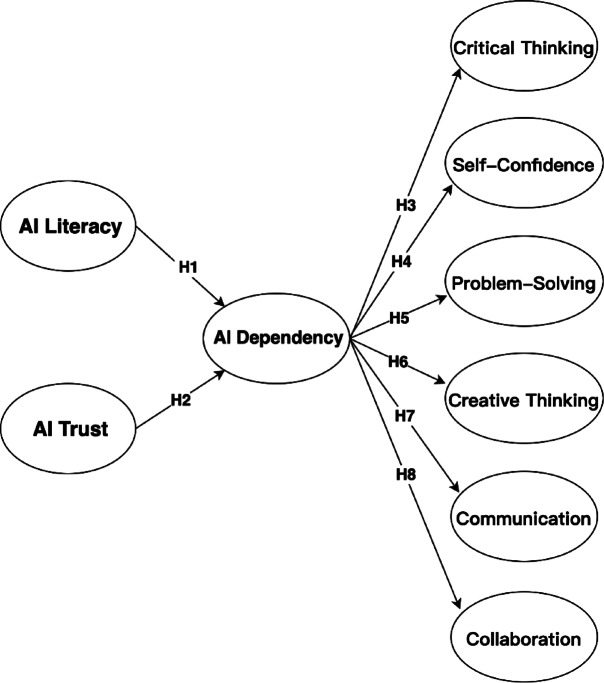

As the integration of Generative Artificial Intelligence (Gen-AI) in education deepens, its potential to both enhance and complicate learning environments becomes increasingly evident. When the Chinese government and higher education institutions aim to enhance AI literacy and trust among preservice mathematics teachers12, concerns also arise about their increasing dependency on AI technologies. This dependency may influence crucial 21st-century skills such as problem-solving, critical thinking, creative thinking, collaboration, communication skills, and self-confidence. Using a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach, this study investigates the following research questions:

Is there a significant relationship between AI literacy and trust and AI dependency among preservice mathematics teachers?

Does AI dependency significantly moderate the relationship between AI literacy, trust in AI, and the development of 21st-century skills such as critical thinking, self-confidence, problem-solving ability, creative thinking, communication skills, and collaboration skills?

The findings of this study may provide new insights for governments, educational institutions, and teachers when conducting seminars aimed at improving AI trust and literacy among preservice mathematics teachers. these seminars, distinct from regular classroom settings, are typically intensive, interactive sessions that focus on specific topics—in this case, AI technologies. Unlike traditional classes that follow a standard curriculum, seminars provide a platform for deeper exploration of AI’s capabilities and implications, facilitating rich discussions and hands-on activities. These insights could be crucial in developing strategies that balance the benefits of AI technologies with the risks associated with their overdependence.

Literature review

The importance of AI literacy and AI trust among preservice mathematics teachers

The rapid advancement of AI has catalyzed significant changes across various sectors, notably propelling the “Industry 4.0” revolution13. In this study, ‘Gen-AI’ refers to generative artificial intelligence applications that are used to enhance educational processes, particularly within the realm of mathematics education. These include, but are not limited to, AI-driven mini-programs like ChatGPT and DeepSeek. ChatGPT is utilized primarily for its ability to generate explanatory content and simulate conversational interactions, making it a valuable tool for creating dynamic learning environments14. DeepSeek, on the other hand, offers advanced data parsing capabilities, aiding in the development of customized learning materials that adapt to the individual needs of students. Both technologies exemplify the practical implementation of Gen-AI in mathematics textbooks, where they contribute to the creation of content that is not only tailored to enhance learning outcomes but also to foster a deeper understanding of mathematical concepts through interactive and personalized learning experiences. The inclusion of these Gen-AI technologies underscores their potential to transform traditional educational practices by integrating cutting-edge AI tools that support both teachers and learners3,14,15.

AI literacy and trust have emerged as pivotal in integrating AI into educational practices16,17. AI literacy is defined as the ability to understand AI’s fundamental technologies and concepts18. This definition extends beyond basic knowledge to include ethical considerations and critical thinking skills, which are particularly crucial for mathematics teachers and preservice mathematics teachers. Such comprehensive literacy influences both the frequency and manner in which AI is applied, subsequently impacting educational quality.

Meanwhile, AI trust varies in definition, focusing on users’ confidence in AI’s reliability and ethical values, and is crucial for AI acceptance in education19,20. It affects technology’s integration into teaching, learning, and assessment, with concerns about AI’s autonomy and complexity sometimes hindering its adoption due to transparency and reliability issues.

AI dependency, defined as an excessive reliance on AI, reflects its instrumental benefits but also highlights potential drawbacks, such as diminished autonomous thinking and learning abilities21. This dependency is becoming a critical topic of study as AI becomes more integrated into daily tasks in educational settings18,22. This dependency is significant because it raises concerns about over-reliance on AI tools among students and educators, which could affect critical thinking skills, decision-making processes, and the development of independent learning strategies. Furthermore, understanding AI dependency is essential for developing effective guidelines and interventions to ensure that AI supports rather than hinders educational outcomes.

AI literacy in mathematics teaching enables educators to utilize advanced tools like AI-assisted mathematical modeling and data analysis, enhancing educational outcomes and fostering critical thinking and ethical awareness among students22–24. Effective teacher training in AI literacy involves not only understanding Gen-AI’s functionalities but also exploring its ethical implications, preparing teachers to apply AI in education responsibly.

Furthermore, AI trust plays a critical role in the educational use of AI, affecting both the acceptance of AI technologies and the overall teaching and learning experience25,26. Higher trust in AI may lead to greater adoption of AI tools in the classroom, provided teachers understand and can predict AI behaviors and outcomes. This trust is essential for reducing uncertainties associated with AI use, thus enhancing its integration into educational practices.

Globally, there is a variance in how well preservice mathematics teachers are prepared in AI literacy, with some regions focusing more on theoretical knowledge than practical applications18,27,28. There is a growing call for educational programs to adopt multidisciplinary approaches that combine AI with subjects like mathematics and computer science, thereby equipping teachers to handle both the opportunities and ethical challenges presented by AI4,29,30.

In summary, fostering AI literacy and trust among preservice mathematics teacher is vital for enabling effective use of AI in teaching, enhancing learning outcomes, and preparing students and teachers to meet the challenges of a digitalized educational landscape.

AI literacy and trust among educators not only influence their own adoption and use of AI technologies but may also significantly affect student dependency on these tools31,32. As teachers become more proficient and trusting of AI, they are likely to integrate these technologies more deeply into their teaching practices6,33,34. This increased exposure may lead students to rely heavily on AI for problem-solving and learning processes, potentially reducing their engagement in critical thinking and independent learning.

This study aims to explore the dynamics between AI literacy, trust in AI, and AI dependency among preservice mathematics teachers. Specifically, it seeks to determine if there is a significant relationship between AI literacy and trust and the level of AI dependency. Additionally, the study will examine whether AI dependency moderates the impact of AI literacy and trust on the development of 21st-century skills such as critical thinking, self-confidence, problem-solving ability, creative thinking, communication skills, and collaboration skills. The hypothesis is that while AI literacy and trust are crucial for the effective integration of technology in education, they could inadvertently lead to increased reliance among students on AI for learning and problem-solving. This research seeks to explore the balance between beneficial use and potential over-dependence, providing insights into how educators can mitigate the risks while maximizing the benefits of AI in teaching environments.

The relationship between AI literacy, AI trust and AI dependency

In examining the relationship between AI literacy, AI trust, and AI dependency, this study utilizes a combined theoretical framework of Self-Efficacy Theory35 and Trust Commitment Theory36. These theories offer a nuanced perspective on the psychological processes that may influence preservice mathematics teachers’ adoption and reliance on AI technologies.

Self-Efficacy Theory, proposed by Bandura37, highlights the influence of individuals’ beliefs in their capabilities to achieve specific outcomes. In the context of AI literacy, this theory is particularly relevant; it posits that preservice mathematics teachers’ self-efficacy regarding their ability to use AI effectively will directly affect their willingness and competence in incorporating AI tools into their teaching practices. This increased self-efficacy in AI can lead to a greater reliance on AI technologies, as teachers who feel capable and confident in their AI skills are more likely to utilize these tools extensively. Such a perspective is crucial for understanding how AI literacy develops among educators and impacts their teaching methodologies, potentially increasing their dependency on AI as a supportive educational tool:

H1: AI literacy has a significant negative relationship with AI dependency among mathematics preservice mathematics teachers.

Trust Commitment Theory highlights the importance of trust in developing and sustaining long-term relationships36, including human interactions with technology. In the context of AI, trust can be understood as the belief in the reliability and effectiveness of AI tools, influencing the degree to which teachers are willing to depend on these technologies in their professional activities.

This hypothesis contends that preservice mathematics teachers who trust AI’s capabilities and ethical standards are more likely to increase their dependency on these tools. Their commitment to using AI is fostered by a trust that the technology will perform as needed without causing harm, leading to greater integration of AI into their daily teaching practices.

H2: trust in AI has a significant positive relationship with AI dependency among mathematics preservice mathematics teachers.

The relationship between AI dependency and 21st century skills

To further elucidate the potential impacts of AI dependency on educational outcomes, additional hypotheses focus on the relationship between AI dependency and various essential 21st-century skills. These skills include critical thinking, self-confidence, problem-solving ability, creative thinking, communication skills, and collaboration skills18. Each of these skills is vital for the comprehensive development of preservice mathematics teachers and their effectiveness in future educational settings38–40.

This hypothesis suggests that increased dependency on AI might inversely affect the critical thinking abilities of preservice mathematics teachers. As AI tools provide ready-made solutions, there is a concern that teachers might engage less in the analytical and reflective processes that underpin critical thinking13,41. The reliance on AI could potentially diminish their ability to independently analyze and evaluate information, leading to poorer decision-making skills.

Hypothesis 3

(H3): AI Dependency has a significant negative relationship with Critical Thinking among mathematics preservice mathematics teachers.

Hypothesis H4 addresses the psychological impact of excessive dependence on AI technologies on pre-service mathematics teachers’ self-confidence. This hypothesis posits that an over-reliance on AI for critical educational tasks such as decision-making and problem-solving might inadvertently undermine teachers’ confidence in their own abilities. If pre-service teachers frequently turn to AI to guide their instructional choices or to resolve pedagogical challenges, there is a risk that they may begin to doubt their capacity to make sound professional judgments independently. This reduced self-confidence could have significant implications for their future teaching practices, potentially leading to a reliance on technology that hinders their development as autonomous and effective educators. By exploring this hypothesis, the study aims to illuminate the subtle yet profound ways in which AI integration might affect the professional identity and efficacy of future educators, emphasizing the need for balanced training that enhances technological proficiency while fostering strong self-reliance and decision-making skills.

Hypothesis 4

(H4): AI Dependency has a significant negative relationship with Self-Confidence among mathematics preservice mathematics teachers.

Hypothesis H5 is grounded in concerns about the potential impact of continuous reliance on AI tools for problem-solving tasks in the education of pre-service mathematics teachers. The assumption underlying this hypothesis is that while AI can significantly aid in addressing routine and complex problems, its pervasive use might inadvertently lead to the atrophy of inherent problem-solving skills among teachers. Over time, this could result in a diminished capacity to engage in creative problem-solving and to independently tackle complex educational challenges without AI support. This hypothesis seeks to explore the long-term effects of AI dependency on the critical cognitive abilities of teachers, particularly their ability to think creatively and solve problems effectively in scenarios where AI tools are not applicable or available. By investigating this hypothesis, the study aims to contribute to the ongoing dialogue on how AI integration in teacher education should be managed to enhance, rather than undermine, essential pedagogical competencies.

Hypothesis 5

(H5): AI Dependency has a significant negative relationship with Problem-Solving Ability among mathematics preservice mathematics teachers.

Hypothesis H6 explores the potential drawbacks of excessive reliance on AI in the realm of education, particularly focusing on the development of creative thinking skills among preservice mathematics teachers. Creativity in teaching is crucial as it involves the ability to devise innovative and effective pedagogical strategies that cater to diverse student needs and learning environments. The hypothesis posits that while AI can provide efficient and often effective standardized solutions, an overdependence on such technology might stifle the development of creativity. This is because AI-driven tools may limit teachers’ opportunities to experiment with novel ideas and approaches, leading them to rely on pre-formulated solutions rather than developing their own creative methodologies. By examining this hypothesis, the study aims to highlight the importance of maintaining a balance between utilizing AI tools for support and fostering an environment that encourages and nurtures creative thinking in teacher education.

Hypothesis 6

(H6): AI Dependency has a significant negative relationship with Creative Thinking among mathematics preservice mathematics teachers.

Effective communication skills are foundational for successful teaching, enabling educators to convey complex concepts clearly and interact meaningfully with students. However, the increasing integration of AI technologies in educational settings raises important questions about the potential impacts on these essential skills. Hypothesis H7, therefore, is developed from concerns highlighted in recent literature that suggests AI dependency could inadvertently diminish the need for preservice mathematics teachers to engage in and develop complex communication skills. Specifically, the hypothesis posits that reliance on AI-driven communication tools, which often handle interactions without requiring the depth and nuances of human engagement, might reduce opportunities for preservice mathematics teachers to practice and refine their interpersonal communication skills. This aspect of the study aims to explore the implications of such technological dependencies, examining whether the conveniences of AI might compromise the development of critical teacher competencies in effectively communicating within the classroom environment.

Hypothesis 7

(H7): AI Dependency has a significant negative relationship with Communication Skills among mathematics preservice mathematics teachers.

Finally, Hypothesis H8 addresses the potential consequences of excessive reliance on AI tools within the context of teacher training for preservice mathematics teachers. The concern underpinning this hypothesis is that while AI technologies offer substantial benefits in terms of resource efficiency and individualized learning, their overutilization might inadvertently reduce the need for direct peer-to-peer interaction and teamwork. Collaboration and teamwork are not only vital for the professional development of teachers but are also essential skills in modern educational settings where group work and interactive learning environments are increasingly common. This hypothesis proposes that if AI tools are used to the extent that they replace traditional collaborative learning activities, there could be fewer opportunities for preservice teachers to develop and enhance these crucial skills. The investigation of this hypothesis aims to shed light on how the integration of AI in educational practices should be balanced to support, rather than replace, essential interpersonal learning experiences.

Hypothesis 8

(H8): AI Dependency has a significant negative relationship with Collaboration Skills among mathematics preservice mathematics teachers.

By testing these hypotheses (Fig. 1), the study seeks to identify the potential drawbacks of AI dependency in teacher education, particularly how it might negatively impact the development of critical skills needed for effective teaching. The findings will be crucial for designing educational programs that balance AI integration with skill development, ensuring that preservice mathematics teachers are well-prepared to utilize technology effectively while maintaining strong professional competencies.

Fig. 1.

Research conceptual model.

Methodology

Research design

This study utilizes a correlational research design, employing Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to investigate intricate relationships among AI literacy, trust in AI, AI dependency, and the cultivation of 21st-century skills in preservice mathematics teachers. This approach is particularly well-suited to our research objectives, as it allows for the analysis of potential direct and moderating effects among variables, directly addressing our research questions about the dynamics between AI literacy, trust in AI, and AI dependency, as well as their impact on developing critical thinking, self-confidence, problem-solving ability, creative thinking, communication skills, and collaboration skills.

Data collection and participants

This study was conducted at Qinghai Normal University, recognized for its pioneering integration of Gen-AI into teacher education. The research involved pre-service mathematics teachers who participated in a structured series of seminars and workshops. These educational events were delivered by a blend of the university’s faculty and external AI experts from the technology sector, ensuring comprehensive exposure to both theoretical and practical aspects of AI. The series ranged from introductory sessions on AI basics to advanced, interactive workshops focusing on programming AI tools and creating AI-enhanced teaching materials. The invitation to participate in these sessions was extended to all mathematics education students at the university, though our study only included those who registered and actively participated. These seminars, while part of ongoing educational enhancements at Qinghai Normal, served a dual purpose as a practical field for this study, allowing us to evaluate the real-world applicability of Gen-AI in educational settings. Only attendees who volunteered to complete our post-event online survey, distributed via the university’s digital platforms, were included in the analysis, ensuring that our data reflected the engagement and insights of those most invested in Gen-AI applications. This purposive sampling method aligned well with the study’s aim to delve deeply into the impact of Gen-AI on teaching practices, making the findings both relevant and reliable.

During these sessions, participants used Gen-AI tools to create educational content, automate the generation of mathematical problems, and develop interactive tutorials or simulations. For their final tasks, they were required to produce a learning media project using Gen-AI, which involved creating AI-generated content that was documented and reviewed as part of our data collection. This provided practical insights into how pre-service teachers apply AI in educational contexts, enriching our understanding of AI’s integration into teaching practices.

Qinghai Normal University was selected for this study due to its leadership in incorporating AI technologies into teacher education in China. The diverse demographic profile of the participants, including variations in age, location, and educational levels, reflected the broad spectrum of pre-service teachers at the institution. This diversity allowed the study to explore the implications of Gen-AI across different educational and cultural contexts, enhancing the generalizability and relevance of the findings. Ethical clearance was secured, and all data collected were treated with strict confidentiality, used solely for research purposes.

AI Literacy and Trust: Items assessed respondents’ knowledge of AI principles, their proficiency with AI tools, and their trust in AI’s effectiveness and reliability.

AI Dependency: This scale measured the extent to which participants relied on AI for teaching and problem-solving.

21st-Century Skills Development: Items here gauged the enhancement of skills such as critical thinking, self-confidence, problem-solving, creativity, communication, and collaboration through the use of AI technologies.

Each item on the survey used a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), to capture the intensity of participants’ attitudes and perceptions. This survey was administered online, allowing participants to fill out the form at their convenience during or after the instructional sessions. The final task for participants involved the creation of a learning media project using Gen-AI tools, which was then documented and reviewed, providing practical insights into the application of AI in educational settings. This task not only served as a data collection method but also as a practical demonstration of participants’ ability to integrate AI into teaching.

To ensure ethical rigor, ethical clearance was obtained from the university’s review board, and all data were treated with strict confidentiality. The diverse demographic profile of the 469 participants, including variations in age, educational background, and geographic location, enriched the study by allowing an exploration of Gen-AI implications across various educational and cultural contexts.

Instrument

This study employed a quantitative research approach, utilizing a rigorously developed survey instrument grounded in prior validated research. The survey was meticulously reviewed for content validity by three experts in mathematics education, technology, and AI, each holding a Ph.D. and affiliated with universities in the top 100 of the QS World University Rankings. These experts, with a minimum of three years of experience in AI technologies and over five years in teaching, evaluated the relevance and accuracy of the survey questions. They provided critical feedback on the clarity, relevance, and coherence of the survey questions, suggesting modifications to enhance the precision and applicability of the items to preservice mathematics teachers’ training in AI.

To ensure inclusivity and accuracy in understanding across different linguistic backgrounds, a Chinese version of the questionnaire was developed alongside the original English version. This bilingual approach was intended to accommodate the diverse linguistic backgrounds of the participants, particularly those who are native Chinese speakers. The translation process was conducted by a bilingual expert in mathematics education, ensuring that the translation was not only linguistically accurate but also culturally relevant. The translated items were subsequently back-translated into English by another independent expert to verify the accuracy of the translation. These efforts ensured that all participants could fully comprehend and accurately respond to the survey, thus enhancing the validity of their responses.

A pilot study was conducted with 50 preservice mathematics teachers who were asked to complete the questionnaire. This initial pilot helped to refine the instrument and assess its validity in a practical setting. The questionnaire utilized a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) to measure various constructs related to AI literacy, trust in AI, AI dependency, and 21st-century skills development.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was chosen as the initial method to assess construct validity due to the exploratory nature of the study. Since the constructs being measured were being adapted and retested in a new context preservice mathematics teachers’ interaction with AI technologies EFA was appropriate to explore the underlying factor structure without imposing a preconceived model. This approach allowed for the identification and confirmation of the factor structure based on empirical data rather than theoretical expectations.

The EFA revealed a clear and robust factor structure, with all items loading significantly on their expected factors. The factor loadings were all above the acceptable threshold of 0.50, ensuring that each construct was adequately represented by its corresponding items. This confirmed the validity of the constructs tailored to measure AI literacy, trust in AI, and dependency, as well as their influence on 21st-century skills.

Reliability analysis using Cronbach’s Alpha was conducted to confirm the internal consistency of the scales. The results indicated satisfactory reliability, with alpha coefficients ranging from 0.78 to 0.89 across all scales, which is above the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70 for social science research, confirming the reliability of the measures.

Data analysis

In this study, data were analyzed using Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM), conducted through AMOS 23.0 software42. CB-SEM was chosen over Partial Least Squares SEM (PLS-SEM) because it is better suited for theory testing and confirmation where the primary goal is to assess the model fit. CB-SEM allows for rigorous hypothesis testing of the relationships between observed and latent variables, which is critical in this study given its focus on established constructs of AI literacy, trust, and dependency. Additionally, CB-SEM handles reflective measurement models more appropriately, where theory suggests that indicators are caused by the construct, aligning well with our theoretical framework. The analysis began with a normality test using SPSS 25.0 to ensure data suitability for further SEM processing.

Following this, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was carried out to validate the measurement model43, confirming the structure and interrelations of the constructs involved. We assessed convergent validity, ensuring that items that are supposed to measure the same construct were indeed related. Discriminant validity was also checked to make certain that different constructs were not overly similar, thus confirming that each represents unique aspects as intended. Reliability of the model was evaluated by examining the consistency of the items within each construct. After establishing the measurement model, we assessed the overall model fit by evaluating a range of fit indices, which helped determine how well the model captured the underlying data. The study concluded with structural model testing and hypothesis testing, analyzing how the constructs relate to each other. During hypothesis testing, relationships among constructs were examined by looking at path coefficients, standard errors, and corresponding p-values. Effect sizes and 2 values were calculated to quantify the explained variance and assess the strength of these relationships, providing a comprehensive understanding of the impact and significance of each construct within the model.

Findings

Assessment of the measurement model

The assessment of the measurement model is divided into two parts: validity and reliability44. In our study, discriminant validity, which helps determine the distinctiveness of indicators related to different constructs, was evaluated from multiple perspectives.

First, we considered the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values, which ideally should exceed the 0.6 threshold to indicate adequate variance captured by the construct relative to the variance due to measurement error, as detailed in Table 143. Our results generally meet this criterion, suggesting that the constructs are well-defined by their indicators.

Table 1.

Construct validity and reliability and factor loadings.

| Construct | Items | Factor loadings | Cronbach’s alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI dependency | AI dependency 1 | 0.722 | 0.811 | 0.706 | 0.651 |

| AI dependency 2 | 0.785 | ||||

| AI dependency 3 | 0.704 | ||||

| AI literacy | AI literacy 1 | 0.806 | 0.842 | 0.845 | 0.681 |

| AI literacy 2 | 0.868 | ||||

| AI literacy 3 | 0.845 | ||||

| AI trust | AI trust 1 | 0.865 | 0.876 | 0.877 | 0.705 |

| AI trust 2 | 0.797 | ||||

| AI trust 3 | 0.738 | ||||

| Collaboration | Collaboration 1 | 0.830 | 0.840 | 0.841 | 0.643 |

| Collaboration 2 | 0.797 | ||||

| Collaboration 3 | 0.822 | ||||

| Communication | Communication 1 | 0.824 | 0.857 | 0.857 | 0.666 |

| Communication 2 | 0.840 | ||||

| Communication 3 | 0.815 | ||||

| Creative thinking | Creative thinking 1 | 0.795 | 0.865 | 0.866 | 0.683 |

| Creative thinking 2 | 0.815 | ||||

| Creative thinking 3 | 0.802 | ||||

| Critical thinking | Critical thinking 1 | 0.730 | 0.845 | 0.846 | 0.647 |

| Critical thinking 2 | 0.795 | ||||

| Critical thinking 3 | 0.802 | ||||

| Problem-solving | Problem-solving 1 | 0.717 | 0.858 | 0.857 | 0.667 |

| Problem-solving 2 | 0.833 | ||||

| Problem-solving 3 | 0.801 | ||||

| Self-confidence | Self-confidence 1 | 0.815 | 0.833 | 0.835 | 0.629 |

| Self-confidence 2 | 0.756 | ||||

| Self-confidence 3 | 0.830 |

Secondly, the Fornell-Larcker criterion45, the correlations between constructs should not exceed the square root of their respective AVEs (Table 2). While our study largely adheres to this criterion, indicating satisfactory discriminant validity, there are instances where the correlations approach the upper limits, suggesting a need for careful interpretation of these relationships.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity result—Fornell-Larcker criterion.

| AI dependency | AI literacy | AI trust | Collaboration | Communication | Critical thinking | Creative thinking | Problem-solving | Self-confidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI dependency | 0.806 | ||||||||

| AI literacy | 0.643 | 0.762 | |||||||

| AI trust | 0.633 | 0.744 | 0.840 | ||||||

| Collaboration | − 0.752 | − 0.719 | − 0.710 | 0.802 | |||||

| Communication | − 0.734 | − 0.788 | − 0.778 | 0.796 | 0.816 | ||||

| Critical thinking | − 0.767 | − 0.715 | − 0.805 | 0.724 | 0.803 | 0.826 | |||

| Creative thinking | − 0.744 | − 0.696 | − 0.786 | 0.704 | 0.781 | 0.812 | 0.804 | ||

| Problem− solving | − 0.756 | − 0.706 | − 0.796 | 0.715 | 0.793 | 0.824 | 0.802 | 0.817 | |

| Self− confidence | − 0.728 | − 0.683 | − 0.773 | 0.791 | 0.767 | 0.797 | 0.776 | 0.787 | 0.793 |

Lastly, the Composite Reliability values in our study typically surpass the 0.70 benchmark, and often exceed 0.80, as recommended by Hair et al. (2019). This indicates that the constructs demonstrate good internal consistency and reliability.

While these indicators collectively suggest that our measurement model possesses good validity and reliability, it is important to approach these findings with caution. The proximity of some correlations to their respective thresholds invites a more conservative interpretation and suggests potential areas for further investigation to confirm the robustness of the construct definitions and their empirical distinctiveness.

Assessment of the structural model

Table 3 illustrates the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results used to assess the model’s goodness-of-fit. The Chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (CMIN/df) is 2.786, which is comfortably within the acceptable range of 1 to 3, as specified by previous studies46–48. This indicates that the model provides an adequate fit to the data. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is recorded at 0.077, and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) at 0.050, both of which are below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.08. These metrics suggest a satisfactory fit, with low error estimates enhancing the model’s credibility.

Table 3.

Evaluation of CFA.

| Index | Estimated model | Recommended criteria47 |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN/df | 2.786 | 1 < x < 3 |

| RMSEA | 0.077 | < 0.08 |

| GFI | 0.814 | > 0.80 |

| AGFI | 0.879 | > 0.80 |

| PGFI | 0.684 | > 0.05 |

| SRMR | 0.050 | < 0.08 |

| NFI | 0.878 | > 0.80 |

| TLI | 0.897 | > 0.80 |

| CFI | 0.907 | > 0.80 |

Moreover, the fit indices including the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) at 0.814, the Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI) at 0.879, the Normed Fit Index (NFI) at 0.878, the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) at 0.897, and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) at 0.907 all surpass the minimum acceptance criteria of 0.80. Notably, the CFI’s value is particularly high, reinforcing the model’s strong consistency with the observed data.

These indices collectively not only affirm that the model is adequate but also underscore its parsimony, indicating that it does not overfit the data. This robust fit forms a reliable foundation for subsequent analyses and supports the study’s theoretical assertions.

The results of the structural model evaluation suggest that AI dependency among preservice mathematics teachers is influenced by their AI literacy and trust in AI. Furthermore, this AI dependency reduces the 21st-century skills of preservice mathematics teachers, as detailed in Fig. 2. This highlights the importance of considering what form of AI literacy is appropriate for preservice mathematics teachers to ensure that it does not negatively impact their 21st-century skills.

Fig. 2.

Final model with standardized estimates. COLL, COMM, CR, CT, PS, and SC represent collaboration, communication, critical thinking, creative thinking, problem-solving skills, and self-confidence, respectively.

The statistical analysis presented in Table 4 offers a robust examination of the relationships hypothesized in our study. The data reveal a significant direct effect of AI literacy on AI dependency (β = 0.505, M = 0.518, STDEV = 0.120, t = 4.221, p < 0.001), affirming Hypothesis H1. Similarly, AI trust also significantly influences AI dependency, albeit to a slightly lesser extent (β = 0.374, M = 0.364, STDEV = 0.100, t = 3.738, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis H2.

Table 4.

Hypotheses testing results.

| β | Mean | STDEV | T statistics | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: AI literacy → AI dependency | 0.505 | 0.518 | 0.120 | 4.221 | 0.000 |

| H2: AI trust → AI dependency | 0.374 | 0.364 | 0.100 | 3.738 | 0.000 |

| H3: AI dependency → critical thinking | − 0.973 | − 0.975 | 0.077 | 12.665 | 0.000 |

| H5: AI dependency → problem-solving | − 1.043 | − 1.051 | 0.071 | 14.767 | 0.000 |

| H4: AI dependency → self-confidence | − 0.980 | − 0.982 | 0.072 | 13.608 | 0.000 |

| H6: AI dependency → creative thinking | − 1.016 | − 1.021 | 0.075 | 13.514 | 0.000 |

| H7: AI dependency → communication | − 0.954 | − 0.966 | 0.087 | 10.961 | 0.000 |

| H8: AI dependency → collaboration | − 0.934 | − 0.938 | 0.084 | 11.075 | 0.000 |

Furthermore, the results indicate that AI dependency has a substantial negative impact on various 21st-century skills, confirming Hypotheses H3 through H8. Specifically, AI dependency profoundly affects critical thinking (β = -0.973, M = -0.975, STDEV = 0.077, t = 12.665, p < 0.001), highlighting a significant deterioration in this skill as dependency increases. Similarly, problem-solving skills are negatively influenced by AI dependency (β = -1.043, M = -1.051, STDEV = 0.071, t = 14.767, p < 0.001), suggesting a major decline in this essential capability. Self-confidence, too, is significantly compromised (β = -0.980, M = -0.982, STDEV = 0.072, t = 13.608, p < 0.001).

Additional 21st-century skills negatively correlated with AI dependency include creative thinking (β = -1.016, M = -1.021, STDEV = 0.075, t = 13.514, p < 0.001), communication (β = -0.954, M = -0.966, STDEV = 0.087, t = 10.961, p < 0.001), and collaboration (β = -0.934, M = -0.938, STDEV = 0.084, t = 11.075, p < 0.001). These findings underscore the significant risks associated with an over-reliance on AI in educational settings, particularly in terms of diminishing critical educational outcomes.

These results underscore the importance of cautious integration of AI tools in educational settings to ensure they support rather than hinder the development of critical competencies in future educators. The findings advocate for educational strategies that not only enhance AI literacy and trust among preservice teachers but also carefully monitor and moderate their dependency on these technologies to preserve and promote essential 21st-century skills.

The statistical analysis in Table 5 delineates the indirect effects of AI literacy and AI trust on 21st-century skills, mediated through AI dependency. Both AI literacy and AI trust exhibit significant negative impacts on skills such as collaboration, communication, critical thinking, creative thinking, problem-solving, and self-confidence. This mediation analysis underscores how the influence of AI literacy and AI trust on these skills occurs primarily through their effect on increasing AI dependency among preservice mathematics teachers.

Table 5.

Indirect effect.

| β | Mean | STDEV | T statistics | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI literacy → AI dependency → collaboration | − 0.416 | − 0.425 | 0.090 | 4.609 | 0.000 |

| AI literacy → AI dependency → communication | − 0.456 | − 0.467 | 0.100 | 4.544 | 0.000 |

| AI trust → AI dependency → collaboration | − 0.359 | − 0.349 | 0.094 | 3.818 | 0.000 |

| AI literacy → AI dependency → creative thinking | − 0.472 | − 0.482 | 0.101 | 4.651 | 0.000 |

| AI trust → AI dependency → communication | − 0.393 | − 0.382 | 0.100 | 3.913 | 0.000 |

| AI literacy → AI dependency → critical thinking | − 0.461 | − 0.470 | 0.100 | 4.594 | 0.000 |

| AI trust → AI dependency → creative thinking | − 0.407 | − 0.395 | 0.104 | 3.912 | 0.000 |

| AI literacy → AI dependency → problem-solving | − 0.467 | − 0.477 | 0.101 | 4.602 | 0.000 |

| AI trust → AI dependency → critical thinking | − 0.397 | − 0.385 | 0.102 | 3.890 | 0.000 |

| AI literacy → AI dependency → self-confidence | − 0.453 | − 0.464 | 0.099 | 4.567 | 0.000 |

| AI trust → AI dependency → problem-solving | − 0.402 | − 0.390 | 0.103 | 3.913 | 0.000 |

| AI trust → AI dependency → self-confidence | − 0.391 | − 0.380 | 0.100 | 3.907 | 0.000 |

Specifically, the Beta coefficients indicate that AI literacy consistently exerts a stronger indirect influence than AI trust across most skills, demonstrating a more pronounced negative mediation effect. For example, the impact of AI literacy on collaboration (β = -0.416, mean = -0.425, STDEV = 0.090, t = 4.609, p < 0.001) and on communication (β = -0.456, mean = -0.467, STDEV = 0.100, t = 4.544, p < 0.001) exceeds that of AI trust (collaboration: β = -0.359, mean = -0.349, STDEV = 0.094, t = 3.818, p < 0.001; communication: β = -0.393, mean = -0.382, STDEV = 0.100, t = 3.913, p < 0.001).

Further analysis reveals similar trends in other domains, with AI literacy’s influence on creative thinking (β = -0.472, mean = -0.482, STDEV = 0.101, t = 4.651, p < 0.001) and critical thinking (β = -0.461, mean = -0.470, STDEV = 0.100, t = 4.594, p < 0.001) also surpassing the effects mediated by AI trust (creative thinking: β = -0.407, mean = -0.395, STDEV = 0.104, t = 3.912, p < 0.001; critical thinking: β = -0.397, mean = -0.385, STDEV = 0.102, t = 3.890, p < 0.001).

These findings illustrate the critical nature of the mediating role of AI dependency, highlighting the necessity for educational strategies that not only foster AI literacy and trust but also address the potential for dependency to negatively impact the development of key educational competencies. Educators should consider interventions that emphasize balanced AI use to mitigate these indirect negative effects, ensuring that AI tools are employed in ways that support rather than undermine essential 21st-century skills.

In addition to the methodological approach, it is important to note the explanatory power of our statistical model, as evidenced by the 2 values obtained from the analysis. These values indicate a substantial proportion of variance explained in each of the dependent constructs by the independent variables, specifically AI dependency and its influence on various educational skills. The 2 value for AI dependency is 0.762, demonstrating a strong impact on the dependent variables. Furthermore, the 2 values for the constructs related to educational skills are notably high: creative thinking at 0.890, self-confidence at 0.862, problem-solving ability at 0.914, critical thinking at 0.934, communication skills at 0.873, and collaboration skills at 0.726. These values suggest that the model is highly effective in capturing the influence of AI dependency on these crucial educational outcomes, offering robust insights into how AI integration affects pre-service teachers’ capabilities across different dimensions of their professional development.

Discussion

AI tools offer substantial advantages in the classroom, including personalized learning experiences that can adapt to individual student needs, increased efficiency in handling administrative tasks, and the ability to provide immediate feedback to learners2,18,49–51. These capabilities can enhance teaching methods and improve learning outcomes by allowing preservice teachers to engage more deeply with content and to tailor their teaching strategies more precisely to their students’ needs. However, while the integration of AI in teacher education holds promising potential for fostering innovative pedagogical approaches, this study also identifies significant concerns. This paper explores the significant relationships between AI literacy, trust, and AI dependency among preservice mathematics teachers, as well as how AI dependency significantly moderates the relationship between AI literacy and trust and the development of 21st-century skills. The study employs a combined theoretical framework of Self-Efficacy Theory35 and Trust Commitment Theory36, which posits that AI literacy is associated with increased dependency, while AI trust also relates to dependency. These theories provide a robust basis for examining the dual impact of AI literacy and trust—not only on dependency but also on how such dependency influences the acquisition and application of essential skills for the 21st century.

First, The demographic profile of the participant teachers, as shown in Table 6, reveals significant insights into the study’s context and its implications. The majority of participants are female (68.02%) and younger (84.43% between 18 and 22 years old), reflecting the current trends in the demographic makeup of pre-service mathematics teachers in Qinghai, China. Notably, a substantial proportion of participants come from rural areas (59.06%), which may influence their exposure to and familiarity with AI technologies compared to their urban counterparts.

Table 6.

Profile of the participant teachers.

| Characteristics | Group | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 150 | 31.98 |

| Female | 319 | 68.02 | |

| Age | 18–22 years old | 396 | 84.43 |

| 23–25 years old | 55 | 11.73 | |

| 26–29 years old | 18 | 3.84 | |

| Home location | Rural areas | 277 | 59.06 |

| Urban areas | 192 | 40.94 | |

| Level education | First-year undergraduate | 130 | 27.72 |

| Second-year undergraduate | 163 | 34.75 | |

| Third-year undergraduate | 86 | 18.34 | |

| Fourth-year undergraduate | 46 | 9.81 | |

| First-year master’s student | 26 | 5.54 | |

| Second-year master’s student | 18 | 3.83 |

This demographic information is crucial as it suggests that AI literacy and its impact on AI dependency could vary significantly across different gender, age, and home location groups. For instance, younger teachers who are more accustomed to digital technologies might adapt more quickly to AI tools, potentially leading to greater dependency. Furthermore, the high representation of females in the study could reflect broader educational trends and has implications for how AI training programs are tailored to meet diverse needs.

The relationship between AI literacy and AI dependency observed in our study indicates that as pre-service mathematics teachers become more familiar and proficient with AI tools, they increasingly rely on these technologies for various educational tasks. This is evident in their utilization of AI for preparing lesson plans, analyzing student data, and crafting teaching strategies. However, while previous studies highlights the transformative potential of AI in education emphasizing the need for AI literacy, prompt engineering proficiency, and enhanced critical thinking28,41, our findings introduce a cautionary perspective on the dependency on AI. Walter advocates for integrating AI skills into curricula to support personalized learning and address diverse educational needs. In contrast, our research suggests that an over-reliance on AI could potentially undermine these very benefits by fostering dependency that may not always enhance student skills effectively. This apparent contradiction may stem from differences in the underlying assumptions about the role and impact of AI in educational settings. Whereas Walter views AI as a tool for augmenting educational practices, our study warns of the risks where such tools might limit skill development rather than enhance it, particularly when students or educators become overly reliant on AI technologies without sufficient critical engagement. Exploring these divergences further could help educators balance the implementation of AI with the need to develop robust, independent problem-solving skills among students.

However, it is important to note that this increasing dependency contradicts previous research which suggested that higher literacy always enhances skills positively. In our context, the increasing reliance on AI could potentially stifle the development of independent problem-solving and critical thinking skills among pre-service teachers, particularly those from rural backgrounds who may have had less initial exposure to such technologies.

Furthermore, AI trust significantly impacts the extent to which pre-service mathematics teachers rely on AI tools, as demonstrated in our findings (H2). As these teachers develop greater trust in the reliability, effectiveness, and utility of AI technologies, their dependency on these tools for critical educational tasks increases. This includes reliance on AI for selecting teaching methods and implementing classroom simulations. This relationship is supported by the Trust Commitment Theory36, which posits that increased trust in a system enhances reliance on its capabilities. Thus, as preservice teachers grow more confident in AI’s functionalities, they are more likely to integrate these tools into their daily teaching practices, trusting that AI will enhance their instructional effectiveness and decision-making processes.

Subsequently, it has been proven that AI dependency reduces 21st-century skills, including problem-solving ability, critical thinking, creative thinking, collaboration skills, communication skills, and self-confidence (H3-H8). Additionally, AI trust has been shown to have an indirect effect on the reduction of preservice mathematics teachers’ 21st-century skills. The evidence points out that among the various skills impacted, problem-solving and creative thinking are the most affected. This suggests that while AI tools can provide immediate solutions and assist with content delivery52,53, their overuse may inhibit preservice mathematics teachers’ ability to think independently and devise innovative solutions to pedagogical challenges. Such an outcome not only affects the quality of teacher preparation but could also have long-term effects on their future students.

Moreover, the indirect effect of AI trust on diminishing these skills further complicates the narrative54. It implies that even a well-intentioned integration of AI into teacher education, if not critically monitored and balanced with active skill development, can lead to a passive learning attitude where reliance on technology supersedes the development of personal expertise and critical educational practices.

This part of the discussion urges educational stakeholders to reconsider how AI tools are integrated into teacher training programs. It advocates for a balanced approach where AI literacy and trust are coupled with strong pedagogical practices that actively promote the development of 21st-century skills55. By doing so, preservice mathematics teachers can be better prepared to navigate the complexities of modern classrooms, ensuring that they remain agile and innovative educators despite the pervasive influence of AI.

Implications

This study offers several theoretical contributions, including a comprehensive exploration of the relationships between AI literacy, AI trust, and AI dependency, which are subsequently proven to have a negative impact on preservice mathematics teachers’ 21st-century skills. Additionally, this research demonstrates that AI literacy does not always have a beneficial effect in reducing AI dependency. In fact, for preservice mathematics teachers, AI literacy is the predominant factor that leads to dependency on AI tools.

This research also provides educational implications for various stakeholders. For educators, the findings of this study suggest the need for caution and the use of appropriate methods when enhancing AI literacy and AI trust to avoid increasing preservice mathematics teachers’ dependency on AI tools. For example, educators might consider integrating critical thinking exercises that challenge students to evaluate the limitations and potential biases of AI tools, thereby promoting a more balanced and critical approach to using technology. Additionally, this research informs preservice mathematics teachers that AI dependency can diminish their 21st-century skills, hence the use of AI tools and dependency on AI should be carefully monitored and managed.

To effectively integrate AI tools into the training of preservice mathematics teachers and to mitigate the risk of AI dependency, this study proposes several practical strategies that can be implemented within teacher education programs. Firstly, AI tools should be incorporated into problem-solving exercises to enhance both AI literacy and critical problem-solving skills. For example, educators could design tasks where AI generates solutions to complex mathematical problems, and students critically evaluate the correctness and feasibility of these solutions. This method ensures that preservice teachers engage deeply with the material and learn to view AI outputs with a critical eye, assessing them just as they would human-generated solutions.

Additionally, it is crucial to develop exercises that allow preservice teachers to critique AI applications, particularly focusing on identifying and discussing potential biases. These activities could involve case studies highlighting instances where AI tools have exhibited bias or failed in educational settings. Such discussions will encourage future educators to recognize the limitations of AI and consider the ethical dimensions of using such technologies in their teaching practices.

Workshops on balanced technology use are also recommended. These workshops would demonstrate effective ways to integrate AI tools into mathematics education, emphasizing that these tools should complement rather than replace traditional teaching methods. By providing real-world examples and hands-on experiences, these workshops can help preservice teachers understand how to utilize AI responsibly and effectively.

Furthermore, teacher training programs should offer clear guidelines on the ethical use of AI in the classroom. These guidelines would serve as a resource for preservice teachers, outlining best practices and ethical considerations for integrating AI tools. This resource would help ensure that teachers remain critical and informed users of technology, aware of both its potential and its pitfalls.

Lastly, the incorporation of regular assessments of AI literacy within teacher training curricula can ensure that preservice teachers not only become proficient in using AI tools but also remain aware of their limitations. These assessments can help educators monitor the progress and understanding of their students, making adjustments to the curriculum as needed to address any areas of weakness.

Implementing these strategies will provide preservice mathematics teachers with a comprehensive education in AI, equipping them with the skills and knowledge necessary to use AI tools thoughtfully and effectively in their future classrooms. This approach will foster a generation of teachers who are not only technologically adept but also ethically aware and critically engaged.

Limitations

This study acknowledges several limitations that merit consideration, each accompanied by recommendations for future research. First, the reliance on self-reported data, which may introduce biases such as social desirability or respondent inaccuracy, could affect the validity of the findings regarding AI literacy, trust, and dependency. Future studies might incorporate more objective measures or triangulate data sources to mitigate these biases.

Second, while our research focused on the effects of AI literacy and AI trust on AI dependency and 21st-century skills, other factors that could influence these outcomes were not examined. For example, variables such as individual differences in technology readiness or institutional support for AI integration might also play significant roles. Future research could apply our framework to explore the impact of these additional variables on AI dependency and its broader implications for preservice mathematics teachers’ professional competence, including TPACK knowledge.

Third, our participant pool was exclusively comprised of preservice mathematics teachers, limiting the generalizability of our findings to other teacher groups or educational contexts. Diverse samples could reveal different characteristics and findings, enriching the understanding of AI’s impact across broader educational landscapes.

Finally, this study’s cross-sectional design does not allow for tracking the long-term effects of AI use in teaching. The incorporation of longitudinal data in future research would be valuable in understanding how AI dependency and its effects on skill development evolve over time. Additionally, while this study employed a quantitative approach, integrating qualitative methods could provide deeper insights into the nuanced experiences and perceptions of AI among preservice teachers. Future studies might benefit from a mixed-methods approach to capture a more comprehensive picture of the dynamics observed.

Conclusions

Enhancing AI literacy and trust among preservice mathematics teachers is crucial for developing 21st-century skills. However, the findings from this study reveal a nuanced picture. While increasing AI literacy and trust is generally beneficial, in certain contexts, it may inadvertently raise AI dependency. This increased dependency can negatively impact essential 21st-century skills, such as problem-solving ability, critical thinking, creative thinking, collaboration, communication skills, and self-confidence. These results offer valuable insights for stakeholders, educational institutions, and teachers, highlighting the need for balanced approaches in integrating AI technologies into teacher training programs.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the participants who assisted with the data collection.

Author contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Dongli Zhang and Tommy Tanu Wijaya; methodology, Tommy Tanu Wijaya; software, Ying Wang and Mingyu Su; formal analysis, Xinxin Li; investigation, Dongli Zhang; resources, Tommy Tanu Wijaya and Dongli Zhang; data curation, Ying Wang and Mingyu Su; writing—original draft preparation, Dongli Zhang; writing—review and editing, Tommy Tanu Wijaya and Xinxin Li; visualization, Ying Wang and Mingyu Su; supervision, Tommy Tanu Wijaya; project administration, Xinxin Li; funding acquisition, Xinxin Li. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Qinghai Normal University Teaching Research Project (No. qhnujy202226) and the Gansu Province Project on Interdisciplinary Literacy Assessment of Secondary School Mathematics Teachers in the Context of High-Quality Educational Development (No. 2025CXZX-343).

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality and privacy-related issues but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board school of mathematical sciences, Qinghai Normal University, Xining, China (#, 2024-11-27).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tommy Tanu Wijaya, Email: 11132024035@bnu.edu.cn.

Ying Wang, Email: 2023103058@nwnu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Zhao, Y. & Gao, L. Classroom design and application of art design education based on artificial intelligence. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Web Eng.10.4018/IJITWE.334008 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li, M. Integrating artificial intelligence in primary mathematics education: investigating internal and external influences on teacher adoption. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ.10.1007/s10763-024-10515-w (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ilieva, G. et al. Effects of generative chatbots in higher education. Inf14(9), 1–26. 10.3390/info14090492 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dwivedi, Y. K. et al. So what if ChatGPT wrote it?’ multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102642 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habib, S., Vogel, T., Anli, X. & Thorne, E. How does generative artificial intelligence impact student creativity? J. Creat.34(1), 100072. 10.1016/j.yjoc.2023.100072 (2024).

- 6.Wijaya, T. T., Su, M., Cao, Y., Weinhand, R. & Houghton, T. Examining Chinese preservice mathematics teachers ’ adoption of AI chatbots for learning: unpacking perspectives through the UTAUT2 model. Educ. Inf. Technol. (2024).

- 7.Kshetri, N. The future of education: generative artificial intelligence’s collaborative role with teachers. IT Prof.25(6), 8–12. 10.1109/MITP.2023.3333070 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu, J., Zheng, R., Gong, Z. & Xu, H. Supporting teachers’ professional development with generative AI: the effects on higher order thinking and self-efficacy. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol.17, 1279–1289. 10.1109/TLT.2024.3369690 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vera, M. M. S. Artificial intelligence as a teaching resource: uses and possibilities for teachers. EDUCAR60(1), 33–47. 10.5565/rev/educar.1810 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldman, S. R., Taylor, J., Carreon, A. & Smith, S. J. Using AI to support special education teacher workload. J. Spec. Educ. Technol.39(3), 434–447. 10.1177/01626434241257240 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zainurrahman, P., Purnawarman, P. & Muslim, A. B. Ethically utilizing GenAI tools to alleviate challenges in conventional feedback provision. J. Acad. ETHICS. 10.1007/s10805-024-09578-9 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meng, X., Shi, L., Yao, L., Zhang, Y. & Cui, L. Developing and validating measures for AI literacy tests: from self-reported to objective measures. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell.10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122463 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang, C., Liu, Z., Aravind, B. R. & Hariharasudan, A. Synergizing language learning: SmallTalk AI in Industry 4.0 and Education 4.0. PeerJ. 10.7717/peerj-cs.1843 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Farazouli, A., Cerratto-Pargman, T., Bolander-Laksov, K. & McGrath, C. Hello GPT! Goodbye home examination? An exploratory study of AI chatbots impact on university teachers’ assessment practices. Assess. Eval High. Educ.10.1080/02602938.2023.2241676 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruiz-Rojas, L. I., Salvador-Ullauri, L. & Acosta-Vargas, P. Collaborative working and critical thinking: adoption of generative artificial intelligence tools in higher education. Sustainability10.3390/su16135367 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang, Y. Balancing: The effects of AI tools in educational context 2. The concerns of using AI tools for academic writing. Front. Humanit. Soc. Sci.3(8), 7–10 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sciences, E., Republic, C. & Republic, C. A systematic review of AI literacy scales. Npj Sci. Learn.10.1038/s41539-024-00264-4 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wijaya, T. T., Yu, Q., Cao, Y., He, Y. & Leung, F. K. S. Behavioral sciences latent profile analysis of AI literacy and trust in mathematics teachers and their relations with AI dependency and 21st-century skills. Behav. Sci.14, (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Nazaretsky, T., Cukurova, M. & Alexandron, G. An instrument for measuring teachers’ trust in AI-based educational technology. In LAK22: 12th International Learning Analytics and Knowledge Conference, 56–66. 10.1145/3506860.3506866 (2022).

- 20.Stevens, A. F. & Stetson, P. Theory of trust and acceptance of artificial intelligence technology (TrAAIT): an instrument to assess clinician trust and acceptance of artificial intelligence. J. Biomed. Inf.148, 104550. 10.1016/j.jbi.2023.104550 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang, S., Zhao, X., Zhou, T. & Kim, J. H. Do you have AI dependency? The roles of academic self-efficacy, academic stress, and performance expectations on problematic AI usage behavior. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ.10.1186/s41239-024-00467-0 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye, J. H., Zhang, M., Nong, W., Wang, L. & Yang, X. The relationship between inert thinking and ChatGPT dependence: an I-PACE model perspective. Educ. Inf. Technol.10.1007/s10639-024-12966-8 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rapaka, A. et al. Revolutionizing learning – A journey into educational games with immersive and AI technologies. Entertain Comput.10.1016/j.entcom.2024.100809 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan, C. K. Y. & Tsi, L. H. Y. Will generative AI replace teachers in higher education? A study of teacher and student perceptions. Stud. Educ. Eval. 10.1016/j.stueduc.2024.101395 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labadze, L., Grigolia, M. & Machaidze, L. Role of AI chatbots in education: systematic literature review. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ.20(1), 1–17. 10.1186/s41239-023-00426-1 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho, C. C. Using AI-generative tools in tertiary education: reflections on their effectiveness in improving tertiary students’ english writing abilities. Online Learn.28(3), 33–54. 10.24059/olj.v28i3.4632 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du, H., Sun, Y., Jiang, H., Islam, A. Y. M. A. & Gu, X. Exploring the effects of AI literacy in teacher learning: an empirical study. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun.11(1), 1–10. 10.1057/s41599-024-03101-6 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng, D. T. K., Leung, J. K. L., Su, J., Ng, R. C. W. & Chu, S. K. W. Teachers’ AI digital competencies and twenty-first century skills in the post-pandemic world. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev.71(1), 137–161. 10.1007/s11423-023-10203-6 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akpan, I. J., Kobara, Y. M., Owolabi, J., Akpan, A. A. & Offodile, O. F. Conversational and generative artificial intelligence and human-chatbot interaction in education and research. Int. Trans. Oper. Res.32(3), 1251–1281. 10.1111/itor.13522 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamalov, F., Santandreu Calonge, D. & Gurrib, I. New era of artificial intelligence in education: towards a sustainable multifaceted revolution. Sustainability10.3390/su151612451 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khlaif, Z. N. et al. University teachers’ views on the adoption and integration of generative AI tools for student assessment in higher education. Educ. Sci.10.3390/educsci14101090 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cabero-Almenara, J., Palacios-Rodriguez, A., Loaiza-Aguirre, M. I. & Andrade-Abarca, P. S. The impact of pedagogical beliefs on the adoption of generative AI in higher education: predictive model from UTAUT2. Front. Artif. Intell.10.3389/frai.2024.1497705 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dahri, N. A. et al. Investigating AI-based Academic Support Acceptance and its Impact on Students’ Performance in Malaysian and Pakistani Higher Education Institutions 0123456789 10.1007/s10639-024-12599-x (Springer US, 2024).

- 34.Pillai, R., Sivathanu, B., Metri, B. & Kaushik, N. Students’ adoption of AI-based teacher-bots (T-bots) for learning in higher education. Inf. Technol. People. 10.1108/ITP-02-2021-0152 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol.52(1), 1–26 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgan, R. M. & Hunt, S. D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark.58(3), 20–38. 10.1177/002224299405800302 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. (Prentice-Hall, 1986).

- 38.Haviz, M., Maris, I. M., Adripen, Lufri, D. & Fudholi, A. Assessing pre-service teachers’ perception on 21st century skills in Indonesia. J. Turkish Sci. Educ.17(3), 351–363. 10.36681/tused.2020.32 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shidiq, A. S. & Yamtinah, S. Pre-service chemistry teachers’ attitudes and attributes toward the twenty-first century skills. J. Phys. Conf. Ser.1157(4), 6–13. 10.1088/1742-6596/1157/4/042014 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Virtanen, A. et al. Computers in human behavior how pre-service teachers perceive their 21st-century skills and dispositions: A longitudinal perspective Arvel. Comput. Hum. Behav.116, 1–9. 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106643 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walter, Y. Embracing the future of artificial intelligence in the classroom: the relevance of AI literacy, prompt engineering, and critical thinking in modern education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ.10.1186/s41239-024-00448-3 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Latan, H. & Noonan, R. Partial least squares path modeling: basic concepts, methodological issues and applications, partial least squares path model. basic concepts. Methodol. Issues Appl.10.1007/978-3-319-64069-3 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L. & Black, W. C. Multivariate Data Analysis. Vol. 87, no. 4 (Annabel Ainscow, 2019).

- 44.Abdollahi, A., Azadfar, Z., Boyle, C. & Allen, K. A. Religious perfectionism scale: assessment of validity and reliability among undergraduate students in Iran. J. Relig. Heal. 60(5), 3606–3619. 10.1007/s10943-021-01362-y (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res.18(1), 39–50. 10.1177/002224378101800104 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu, Y. et al. Development and validation of the social media perception scale for preservice physical education teachers. Front. Psychol.10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1179814 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wijaya, T. T. & Weinhandl, R. Factorsinfluencing students ’ continuous intentions for using micro-lectures in the post-COVID-19 period: A modification of the UTAUT-2 approach. Electron. 11(1924) (2022).

- 48.Sarfraz, M., Fiaz, K. & Ivascu, L. The international journal of management education factors affecting business school students’ performance during the COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated and mediated model. Int. J. Manag Educ.20(2), 100630. 10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100630 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee, D. & Yeo, S. Computers & education developing an AI-based chatbot for practicing responsive teaching in mathematics. Comput. Educ.191, 104646. 10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104646 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chai, C. S., Wang, X. & Xu, C. An extended theory of planned behavior for the modelling of Chinese secondary school students’ intention to learn artificial intelligence. Mathematics8(11), 1–18. 10.3390/math8112089 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kamalov, F., Calonge, D. S. & Gurrib, I. New era of artificial intelligence in education: towards a sustainable multifaceted revolution. Sustainability. 1–27 (2023).

- 52.Dunder, N., Lundborg, S., Wong, J., Viberg, O. & Machinery, A. C. Kattis vs ChatGPT: assessment and evaluation of programming tasks in the age of artificial intelligence. In Fourteenth International Conference On Learning Analytics & Knowledge, LAK 2024-Learning Analytics in the Age of Artificial Intelligence CL-Kyoto, Japan, 821–827 10.1145/3636555.3636882 (KTH Royal Inst Technol, 2024)

- 53.Liu, R. et al. Teaching CS50 with AI leveraging generative artificial intelligence in computer science education. In Proceedings of the 55th ACM technical symposium on computer science education, SIGCSE 2024 Vol. 1, no. 55th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE), 750–756. 10.1145/3626252.3630938 (Harvard Univ, 2024).

- 54.Gomez, S. C., Garcia-Pernia, M. R., Callejo, L. C. & Echeandia, R. Development of AI competencies for future teachers: a practical experience creating interactive narratives. Digit. Educ. Rev.10.1344/der.2025.46.158-167 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ravšelj, D. et al. Higher education students’ perceptions of ChatGPT: A global study of early reactions. 10.1371/journal.pone.0315011 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed in this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality and privacy-related issues but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.