Abstract

The photocatalytic removal of Reactive Black 5 (RB5) was investigated using a titanium dioxide-polyethylene terephthalate (TiO2-PET) catalyst under visible (VIS) light. The sol-gel method was employed for the fabrication of the TiO2-coated PET catalyst, which was then characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), and elemental mapping (MAP) analysis. This study examined the reaction kinetics using the one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach and evaluates the effects of various parameters, including pH (3–11), catalyst dosage (0.1–1 g L− 1), contact time (15–120 min), RB5 concentration (10–50 mg L− 1), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content (2–100 mM), purging gases, organic compound types, and ionic strength, on the photocatalytic removal of RB5. Under optimal conditions (pH= 3, [RB5]°= 20 mg L− 1, nanocatalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1), 99.99% of the dye was removed after 120 min. Increasing the RB5 concentration (10–50 mg L− 1) resulted in a decrease in the observed reaction rate constant (kobs) from 0.052 to 0.0017 min− 1, while the calculated electrical energy per order (EEO) increased from 11.08 to 338.82 kWh m− 3. Furthermore, the total operating cost of the light emitting diode (LED)/TiO2-PET process (3 USD kg− 1) was lower than that of other photocatalytic processes, including LED/TiO2 (4.73 USD kg− 1), LED/PET (40 USD kg− 1), and LED (63.16 USD kg− 1). The removal of RB5 was negatively affected by the presence of H2O2, O2 and N2 gases, organic compounds, and ionic species. Radical quenching experiments confirmed that hydroxyl radicals (·OH) were the dominant reactive species responsible for RB5 degradation. The RB5 removal efficiency using the LED/TiO2-PET method (99.99%) was significantly higher than that of the LED/TiO2 method (63.42%). Desorption experiments demonstrated excellent catalyst stability, maintaining catalytic activity for up to five sequential cycles. GC-MS analysis identified several intermediate degradation products, including 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid, benzoic acid (2-amino-, methyl ester), benzene [(methylsulfonyl) methyl], phenol, 4-naphthalenedione, acetic acid, and propionic acid. Moreover, the removal efficiency in drinking water samples was approximately 63.31%, whereas for real textile wastewater samples, it reached 96.66%. Toxicity tests conducted on the final treated solutions confirmed no toxicity toward Daphnia magna, demonstrating the effectiveness of the LED/TiO2-PET method in degrading both RB5 dye and its toxic by-products.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-95091-x.

Keywords: Textile wastewater, Visible light, Nanocomposite, Daphnia magna

Subject terms: Environmental sciences, Chemical engineering

Introduction

The global issue of water pollution is driven by the increasing production of chemicals across various industries and the rapid growth of the world’s population1–5. Wastewater discharged from textiles, leather, pharmaceuticals, and paper industries contains various dyes6–8. Textile production is a major source of color-causing pollutants, as even trace amounts of dyes (less than 1 part per million) can significantly alter water clarity, gas solubility, and other characteristics of rivers, lakes, and other water bodies9–11. Azo dyes dominate the dye industry, accounting for over 70% of total annual production. Characterized by nitrogen double bonds (N = N) in their chemical structure, they are among the most widely used commercial reactive dyes12,13. The vivid coloration of wastewater not only creates an unpleasant appearance but also poses a threat to both the environment and human health14,15. Remazol Black B (Reactive Black 5) is a toxic, mutagenic, and poorly biodegradable compound with potential carcinogenic effects16,17. Reducing or eliminating the release of colored wastewater is essential16,17. Traditional methods for treating dye-contaminated water have historically relied on adsorption18, filtration19, photo degradation, biodegradation20 and coagulation21. However, due to the chemical stability of dyes, these treatments often have drawbacks, including high costs, limited effectiveness, and an inability to fully degrade contaminants9,22,23. Instead, they typically transfer pollutants from liquid to solid form, generating secondary waste that requires further processing22,23. To overcome these challenges, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have gained popularity as effective alternatives24–28. AOPs facilitate the oxidation and degradation of organic contaminants through methods such as photocatalysis, ultraviolet (UV)/H2O2, UV/O3, UV/ZnO, UV/TiO2, and Fenton-based processes, including UV/Fenton29–34. The utilization of TiO2 photocatalysis as an AOPs for the degradation of hazardous organic compounds is gaining popularity due to its non-toxic nature, photochemical stability, and cost-effectiveness35–38. Although TiO2 photocatalysts offer several advantages, there are also some drawbacks associated with TiO2 photocatalysis, including low efficiency in utilizing light irradiation and difficulties in separating the photocatalyst from the treated solution after the process39. To tackle these limitations and enhance photocatalytic efficiency, loading photocatalysts onto suitable fine adsorbents can be advantageous. This approach helps concentrate pollutants around the photocatalysts, facilitating the rapid and efficient decomposition of organic pollutants, while also simplifying the overall photocatalytic process39,40. Due to its widespread use in the production of single-use mineral water bottles and its non-biodegradable properties, PET has become a major environmental concern. However, since thermoplastic polymers can be melted and reformed, they are easily recyclable. In addition, PET can be used as a support for nanoparticles, enabling the production of nanocomposites with enhanced physicochemical properties36,41,42. During the previous study, visible-light photocatalysts were irradiated using a Xenon (Xe) lamp equipped with a UV cut-off filter. To prevent overheating, the lamp was cooled with water. It is important to note that UV light leakage from the filter may impact the performance of the photocatalysts9. Recent research has shown promising results by utilizing energy-efficient LED sources to design compact photocatalytic reactors for industrial effluent treatment. The use of LEDs allows for the emission of pure visible light and enables the development of small, space-saving equipment for various applications43. There are many reports on the removal of RB5 using TiO2 nanoparticles as a photocatalyst9,44,45. However, limited information is available regarding the removal efficiency and kinetics of RB5 using illuminated TiO2-PET. In the field of environmental photocatalysis, most studies have focused on TiO2 nanoparticles, where higher photocatalytic efficiency is observed due to the large surface-to-volume ratio resulting from reduced particle size. However, in practical photocatalytic processes, separating these finely powdered photocatalysts from photoreactors is challenging. Ongoing efforts have aimed at finding low-cost, highly active, and easily recyclable TiO2-based photocatalysts. TiO2-PET nanocomposites can be easily separated from the solution, overcoming the disadvantages of TiO2 nanoparticles as nanocatalysts. This study examined the efficacy of using TiO2 immobilized on PET in an LED system for the removal of RB5 from aqueous solutions. Various operational variables, including pH, catalyst dosage, RB5 concentration, different gases, H2O2 amount, organic and anion compounds, and radical scavengers, were investigated to determine their effects. The efficiency of various systems, reusability, kinetic models, and energy consumption were evaluated under constant conditions. The effectiveness of RB5 removal from both drinking water and textile effluent was assessed under optimized conditions. A cost evaluation was conducted using Operational Cost (OC), intermediate analysis was performed using gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy (GC–MS, Varian 4000), and toxicity bioassays were conducted with Daphnia magna.

Materials and methods

Materials

All the materials used in this study were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). RB5 (C26H21N5O19S6Na4), with a purity of more than 95%, was acquired from Alvan Sabet Co., Iran. The chemical structure has been presented in Table S1. A Namanoorasia Co. LB 15/A80 model LED lamp with a 15 W power rating was used as the light source for the photocatalytic removal of RB5. The same photocatalytic reactor used in a prior experiment was employed in this process46.The pH of the solution was measured using a Metrohm (Switzerland) pH meter, and adjustments were made with either HCl (0.1 N) or NaOH (0.1 N).

Synthesis of the TiO2-PET nanocomposite and characterizations

The process began by collecting PET bottles from waste recycling facilities, washing them with deionized water, and allowing them to air-dry at room temperature40. Subsequently, the bottles were broken into small pieces measuring 1–3 mm. Ten grams of shredded PET were combined with 2 weight% hydrogen peroxide and placed in a hydrothermal autoclave reactor. The reactor was then placed in an oven and heated to a temperature of 180 °C, which was maintained for 7 h. Afterward, the reactor was allowed to cool overnight, and the resulting PET products were removed, dried, powdered, and used to create a TiO2-PET nanocomposite. A colloidal suspension of TiO2 was prepared by dissolving titanium tetra-isopropoxide (TTIP, Sigma Aldrich) in isopropanol at a 1:13 molar ratio37. This solution was placed into a beaker containing 50 mL of 0.1 M HNO3. The PET samples were then submerged in the acid TiO2 precursor and heated in a reflux condenser for 120 min at 80 °C while stirring. After the samples were removed and rinsed, they were placed in an Elma sonic ultrasound bath at low frequency (37 kHz) for two minutes to remove any unbound TiO2. A schematic diagram of the synthesis of the TiO2 nanoparticles-coated PET is shown in Fig. S1.

Characterizing and analytical methods

To determine the crystal structure of PET, TiO2, and the TiO2-PET nanocomposite at room temperature, XRD was employed. The average particle size of the catalyst was calculated using the Debye–Scherrer formula. The identification of functional groups on the surface of PET, TiO2 nanoparticles, and TiO2-PET nanocomposite was performed using FT-IR analysis. SEM was used to determine the surface morphology of the samples, while EDX-MAP was employed to determine the material composition of the samples. The pHpzc of the samples was evaluated using the technique described by Shirzad-Siboni et al.47. To assess the surface charge properties of the TiO2-PET nanocomposites, the pHpzc was measured by preparing a 1 L solution of 0.1 M NaNO3 and dividing it into 10 separate solutions with pH values ranging from 2 to 11. HCl and NaOH of the appropriate molarity were added to adjust the pH. Then, 0.2 g of TiO2-PET nanocomposites was added to the solutions and shaken at 170 rpm for 48 h. After centrifuging the mixtures, the final pHs were measured and plotted against the initial pHs. The pHpzc was determined at the point where the line of final pH intersected the line of initial pH. The transformation products of RB5 were investigated to understand the reaction pathways. GC-MS was used to identify the products. Samples were pretreated using the liquid–liquid extraction method with trichloroethylene solvent to extract possible intermediate products of the dye oxidation. A HP-5 column (30 m length, 0.25 mm internal diameter, 0.25 μm film thickness) was employed. The temperature was initially set to 100 °C for 5 min, then incrementally raised to 280 °C at a rate of 10 °C per minute, with helium as the carrier gas at a rate of 1 mL min− 1. The ionization mode was electron impact (70 eV), and data were collected in full scan mode (m/z 50–1000). The injection temperature and MS source temperature were set to 280 °C and 230 °C, respectively.

Experimental method

This study employed the OFAT approach to explore the influence of various variables on the photocatalytic removal of RB5. The parameters investigated included pH (3–11), catalyst dosage (0.1–1 g L− 1), initial RB5 concentration ([RB5]0) (10–50 mg L− 1), O2 and N2 gases at a 2 L min− 1 flow rate, H2O2 concentration (2–100 mM), type of organic compounds, and type of anions at concentrations of 20 mg L− 1. To conduct the experiment, a stock solution of RB5 with a concentration of 1000 mg L− 1 was prepared by dissolving 1 g of RB5 in distilled water. The removal efficiency of RB5 was compared when exposed to PET-alone, TiO2-alone, TiO2-PET, LED-alone, LED/PET, LED/TiO2, and LED/TiO2-PET under the same reaction conditions. To evaluate the reusability of the catalyst, it was exposed to a 2 M NaOH solution, and the experiment was repeated five times. The pH of the solution was found to be optimum at 3, while the catalyst dosage and [RB5]° were held constant at 0.5 g L− 1 and 20 mg L− 1, respectively. With these conditions fixed, the effects of other parameters were then examined. Experiments were conducted in batches, with constant stirring, at a temperature of 25 ± 1 °C over a period of two hours, under ambient conditions. A solution was prepared by combining RB5 and the TiO2-PET nanocomposite, which was then left in the dark environment for 30 min to reach equilibrium. Afterward, the solution was irradiated with a 15 W LED lamp to conduct the photocatalytic removal of RB5. The TiO2-PET nanocomposite was removed by centrifuging the suspension for 10 min. Subsequently, the concentration of residual RB5 in the supernatant was measured using a HACH-DR 5000 (USA) at λmax = 597 nm48. The kinetic behavior of the process was investigated and modeled using zero-order, first-order, second-order, and Langmuir–Hinshelwood equations. To assess the cost-effectiveness, the EEO was calculated. A summary of the equations and constants employed is presented in Table S2. At the end of the reaction, intermediate products in the photocatalytic degradation of RB5 were identified through GC-MS analysis, and the toxicity in the photocatalytic removal of RB5 was assessed using Daphnia magna. The experiments were conducted under optimal conditions (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1, pH= 3, [RB5]°= 20 mg L− 1, and contact time= 120 min) to determine the toxicity of the treated effluent. Samples were collected, and the results of the bioassay were determined using Daphnia magna. The Daphnia were fed 5 mg L− 1 of rough rice every 2 days40. The assessment followed the guidelines outlined in NBR 12.713 regulations40. Several solutions were selected for testing, subjected to volumetric dilution, and evaluated using 10 samples of Daphnia magna cultured in the laboratory between 2 and 26 h. The diluted solutions were maintained at temperatures between 20 and 25 °C, with exposure times ranging from 12 to 96 h. The number of immobilized organisms was calculated based on their concentrations, and the ratio of immobilized organisms was determined using the gathered data. A Daphnia was considered immobile or deceased if it did not move for 15 s after gentle shaking. The samples selected for examination were characterized by the following attributes:

Different levels of concentration for the PET, TiO2, and TiO2-PET (50, 100, 250, 500, 1000, 2000, 4000, 6000, and 8000 mg L− 1).

Different levels of RB5 (0.5, 1, 3, 5, 15, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mg L− 1).

Different levels of the synthetic effluent and textile industry outlet effluent after treatment (0.5, 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, 25, 50, 75, and 100 volume percentage).

To ensure the accuracy of the evaluation results, control sets of the experiments were conducted. The LC50 and its 95% confidence limits were determined using the probit analysis feature in SPSS software. The toxicity of the substance was measured as LC50 and toxicity units (TU). The toxicity unit value was calculated as 100/LC50, described as the volume proportion.

Results and discussion

Catalyst properties

XRD and FTIR

Figure 1 displays the XRD patterns of the PET, TiO2 and TiO2/PET composite. The XRD study for the PET revealed 2θ values of 18.1°, 23.4° and 25.8° in relation to the (010), (110), and (100) planes, respectively. This indicates that the PET employed had a low crystallinity and a triclinic structure49. Also, the XRD study for the TiO2 nanoparticles revealed 2θ values of 25.33°, 36.01°, 37.90°, 48.06°, 53.96°, 55.06°, 62.70°, 69.01°, and 70.41° in relation to the (101), (103), (004), (200), (105), (211), (204), (116), and (220) planes, respectively50,51. The diffraction patterns revealed that the nanoparticles synthesized were of anatase phase, which was further confirmed using the JCPDS card No. 84-1285. The peak at 25.33° was the most prominent diffraction peak, which indicated the (101) plane of anatase TiO2. The peaks at 53.96 and 55.06° are associated with the rutile structure, while other peaks are attributable to the anatase structure. The evidence suggests that the primary crystal phase of the TiO2 nanoparticles was anatase, with only a small amount of rutile present. The findings of this work are consistent with the research carried out by Liu et al.52. The presence of distinct peaks observed in Fig. 1 confirmed the successful growth of the TiO2 nanoparticles on the PET substrate, thus demonstrating the effectiveness of the TiO2-PET nanocomposite. Based on the Debye–Scherrer formula53, the average sizes of TiO2 and TiO2-PET were calculated to be 12.13 and 19.83 nm, respectively. Figure 2 displays the FT-IR patterns of the PET, TiO2 and TiO2/PET composite. The TiO2 nanoparticles absorption peaks observed at 690.5, 1638.71 and 3454.51 cm− 150. The vibrational energy in the range of 500–600 cm− 1 is attributed to the bending of titanium-oxygen-titanium bands in the TiO2 lattice. The broad band in the range of 3400–3600 cm− 1 is due to the interaction between the hydroxyl groups of water molecules and the TiO2 surface. The peak at 1650 cm− 1 is associated with the bending of the −OH group. There were multiple noticeable absorption peaks at various wavenumbers, as indicated by an analysis of the FT-IR spectrum such as 435.50, 504.64, 726.73, 791.86, 846.54, 872.25, 969.85, 1019.45, 1127.70, 1253.47, 1342.70, 1411.12, 1471.54, 1505.79, 1577.32, 1717.27, 2968.49 and 3430.93 cm− 1 for the PET40. The following vibrations were found to be responsible for the peak at various bands: vibrations of the C–H benzene ring (726.73 cm− 1), ester group (1127.70 and 1253.47 cm− 1), C=O band vibrations (1717.27 cm− 1), C–H vibrations (2968.49 cm− 1), and O–H group (3430.93 cm− 1). The TiO2-PET nanocomposite absorption peaks observed at 513.69, 645.71, 726.8, 783.41, 926.30, 968.93, 1019.41, 1124.04, 1252.93, 1341.46, 1413.48, 1574.10, 1638.84, 1715.75 and 3431.13 cm− 1. The presence of peaks observed in Fig. 2 confirmed the successful growth of the TiO2 nanoparticles on the PET substrate, thus demonstrating the effectiveness of the TiO2-PET nanocomposite.

Fig. 1.

XRD image of the samples.

Fig. 2.

FT-IR image of the samples.

SEM, EDX and MAP

The shape of the samples was examined using SEM (Fig. 3a–c). The TiO2 and TiO2–PET nanocomposite showed a spherical shape, with some particles adhering to one another. The aggregation of nanoparticles results from their mutual attraction through weak interactions, leading to the formation of micron-sized clusters with high surface energy54. The synthesis conditions—such as the surrounding environment, temperature, and surface chemistry—can influence whether nanoparticles form soft or hard agglomerates. To determine the material composition of the samples, EDX-MAP analysis was performed. As shown in Fig. 4a, PET contained 54.96% carbon and 45.04% oxygen, TiO2 nanoparticles comprised 50.83% oxygen and 49.17% titanium, and the TiO2–PET nanocomposite consisted of 32.72% carbon, 41.13% oxygen, and 26.14% titanium. This indicates that the nanocomposite produced was pure, as only carbon, oxygen, and titanium were detected. The elemental mapping results from energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), depicted in Fig. 4b, further confirm that titanium and carbon elements are present in the same regions within the samples, suggesting that TiO2 is effectively coating the surface of PET.

Fig. 3.

SEM image of the samples: (a) PET, (b) TiO2 and (c) TiO2-PET.

Fig. 4.

EDX (a) and MAP (b) image of the samples.

The influence of operating parameters

pH

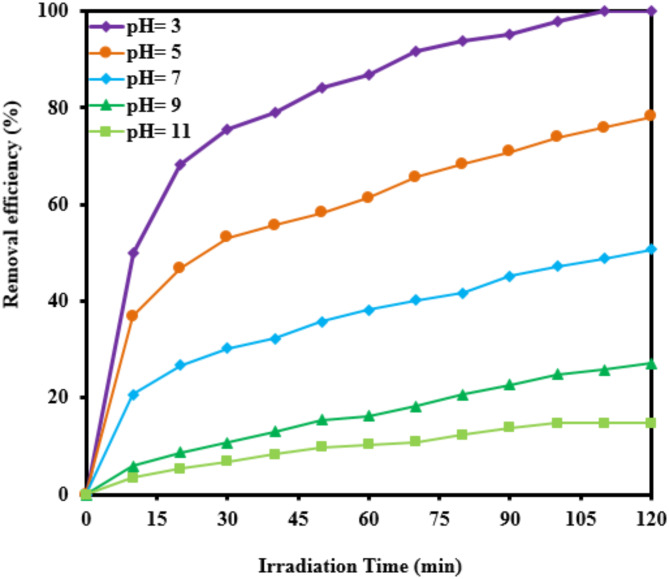

The pH of the solution plays a crucial role in determining the surface charge characteristics of catalysts, which subsequently influences the adsorption and degradation processes of RB5. The photocatalyst’s effectiveness in removing RB5 was evaluated at pH levels ranging from 3 to 11 under identical conditions: a catalyst dosage of 0.5 g L−1 and an initial RB5 concentration of 20 mg L−1. As illustrated in Fig. 5, an increase in pH from 3 to 11 resulted in a decrease in removal efficiency from 99.99 to 14.8%. TiO2, TiO2-PET, and PET were found to have pHpzc values of 6.8, 4.385, and 5.7, respectively. At pH 3 (a strongly acidic environment), the maximum degradation rate constant of RB5 was 0.0328 min−1. However, as the pH increased from 5 (slightly acidic) to 11 (strongly basic), the first-order degradation rate constant of RB5 decreased from 0.0105 to 0.0013 min−1. This decline is attributed to the influence of pH on the surface charge of the nanocomposite. Specifically, TiO2 exhibits a positive charge at pH values below 6.8 and a negative charge at higher pH levels (Eqs. 1–2)9.

Fig. 5.

Effect of initial pH on the photocatalytic removal of RB5 (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1, [RB5]0= 20 mg L− 1).

|

1 |

|

2 |

At the pH range studied, it is recognized that RB5 predominantly existed in its ionic form because of the low pKa value of the sulfonic group in its structure37,55. It was anticipated that, at basic pH, the negative charges of the catalyst would push away the dye molecules, thereby reducing the effectiveness of degradation. The surface of the catalyst contained a greater amount of positive charges below pHpzc. As a result, the removal of RB5 was enhanced due to the presence of negatively charged RB5 species. Additionally, the generation of hydroxyl radicals by the nanocomposite increased with rising solution pH. However, no significant change in process efficiency was observed when the pH was increased from 9 to 11. A pH of 3 was found to be the most favorable condition for the photocatalytic removal of RB5 using TiO2-PET.

Nanocatalyst dosage

The graph in Fig. 6 illustrates the effectiveness of varying nanocatalyst dosages (0.1–1 g L− 1) in the photocatalytic elimination of RB5, while other parameters, such as pH and initial RB5 concentration, were kept constant at 3 and 20 mg L− 1, respectively. The results indicated that the photodegradation process was most effective at a catalyst dosage of 0.5 g L− 1, after which the performance began to decline. This trend can be attributed to the relationship between the number of active sites available on the catalyst surface and the penetration depth of LED light into the suspension56–58. As the catalyst dosage increased, the number of active sites also went up; however, this is accompanied by increased turbidity, which reduces LED light penetration9,17. Consequently, the portion of the suspension that is photo-activated decreases. Similar observations have been reported by other researchers39,59. A dosage of 0.5 g L− 1 was found to be the most favorable for the photocatalytic removal of RB5 using TiO2-PET.

Fig. 6.

Effect of catalyst dosage on the photocatalytic removal of RB5 (pH= 3, [RB5]0=20 mg L− 1).

Initial RB5 concentration

In this context, the initial RB5 concentrations was changed from 10 to 50 mg L− 1 in the photocatalytic elimination of RB5, while other parameters, such as pH and catalyst dosage, were kept constant at 3 and 0.5 g L− 1, respectively. As shown in Fig. 7, the removal efficiency of RB5 was nearly 100% at an initial concentration of 10 mg L− 1 within the first 90 min. However, as the concentration increased to 20, 30, 40, and 50 mg L− 1, the efficiency declined from 99.99 to 72.01%, 49.75%, and 22.48%, respectively. This decrease in efficiency has been attributed to the increased adsorption of dye molecules on the catalyst surface, which can reduce its photocatalytic activity60–62. Besides, Silva and coworkers9 reported that an excessive amount of dye molecules can absorb UV radiation, preventing the effective stimulation of the TiO2– brass structured particles. As a result, the production of ·OH radicals decreases due to reduced radiation exposure on the catalyst surface. Based on these findings, experiments were conducted using 20 mg L− 1 of RB5, as this concentration was found to yield the optimal decomposition rate.

Fig. 7.

Effect of initial RB5 concentration on the photocatalytic removal of RB5 (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1, pH= 3).

Kinetics study of RB5 degradation

The results of the experiments, taken at various reaction times and different concentrations of the RB5 (10–50 mg L− 1) under the optimum condition (pH= 3 and dosage= 0.5 g L− 1), were evaluated through zero, first, and second-order equations to find the best fit. A summary of the equations and constants employed has been presented in Table S2. The values of k for zero-order, first-order and second-order reactions were ascertained by plotting graphs of  ,

,  ,

,  against interaction duration, respectively60,63. The photocatalytic degradation of RB5 resulted in a strong linear correlation that passed the first-order kinetic model with an impressive coefficient of regression (R2 > 0.9931). The RB5 concentration was increased from 10 to 50 mg L− 1, which consequently led to a considerable decrease in the reaction rate constant (Kobs) from 0.052 to 0.0017 min− 1 (Table 1). Using the Langmuir–Hinshelwood (L–H) model, it is possible to predict the adsorption and photocatalytic characteristics of the photocatalyst. By plotting 1/kobs versus the initial concentration of RB563, the values of KRB5 and kc obtained were 0.1636 L mg− 1 and 0.1309 mg L− 1min− 1, respectively. Aguedach et al.64 reported that Langmuir adsorption constant of RB5 was KRB5= 0.027 L mg− 1 and kc= 0.757 mg L− 1min− 1, respectively, from the photocatalytic degradation RB5 by UV-irradiated TiO2 coated on non-woven paper. Alaton and Balcioglu65 reported that the Langmuir adsorption constant of RB5 was KRB5= 2.01 L mg− 1 and kc= 4.47 mg L− 1 min− 1, respectively, from the photocatalytic degradation RB5 by TiO2/UV-A process. Soltani and Entezari66 stated that the Langmuir adsorption constant of RB5 was KRB5= 0.416 L mg− 1 and kc= 0.936− 1 min− 1, respectively, from the solar photocatalytic removal of RB5 by BiFeO3.

against interaction duration, respectively60,63. The photocatalytic degradation of RB5 resulted in a strong linear correlation that passed the first-order kinetic model with an impressive coefficient of regression (R2 > 0.9931). The RB5 concentration was increased from 10 to 50 mg L− 1, which consequently led to a considerable decrease in the reaction rate constant (Kobs) from 0.052 to 0.0017 min− 1 (Table 1). Using the Langmuir–Hinshelwood (L–H) model, it is possible to predict the adsorption and photocatalytic characteristics of the photocatalyst. By plotting 1/kobs versus the initial concentration of RB563, the values of KRB5 and kc obtained were 0.1636 L mg− 1 and 0.1309 mg L− 1min− 1, respectively. Aguedach et al.64 reported that Langmuir adsorption constant of RB5 was KRB5= 0.027 L mg− 1 and kc= 0.757 mg L− 1min− 1, respectively, from the photocatalytic degradation RB5 by UV-irradiated TiO2 coated on non-woven paper. Alaton and Balcioglu65 reported that the Langmuir adsorption constant of RB5 was KRB5= 2.01 L mg− 1 and kc= 4.47 mg L− 1 min− 1, respectively, from the photocatalytic degradation RB5 by TiO2/UV-A process. Soltani and Entezari66 stated that the Langmuir adsorption constant of RB5 was KRB5= 0.416 L mg− 1 and kc= 0.936− 1 min− 1, respectively, from the solar photocatalytic removal of RB5 by BiFeO3.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters and electrical energy per order obtained at different RB5 concentration (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1 and pH= 3).

| [RB5]0 (mg L− 1) | Zero-order | First-order | Second-order | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k0 (mol L− 1 min− 1) | R 2 | kobs (min− 1) | 1/kobs (min) | R 2 | EEO (kWh m− 3) | k2 (Lmol− 1 min− 1) | R 2 | |

| 10 | 0.0502 | 0.5023 | 0.052 | 19.2308 | 0.9936 | 11.08 | 254.46 | 0.6449 |

| 20 | 0.117 | 0.6785 | 0.0328 | 30.4878 | 0.9931 | 17.561 | 44.292 | 0.2533 |

| 30 | 0.1396 | 0.8185 | 0.0096 | 104.167 | 0.9532 | 60 | 0.0007 | 0.9879 |

| 40 | 0.1328 | 0.8994 | 0.0048 | 208.333 | 0.9517 | 120 | 0.0002 | 0.769 |

| 50 | 0.0754 | 0.8812 | 0.0017 | 588.235 | 0.9057 | 338.824 | 0.0001 | 0.9266 |

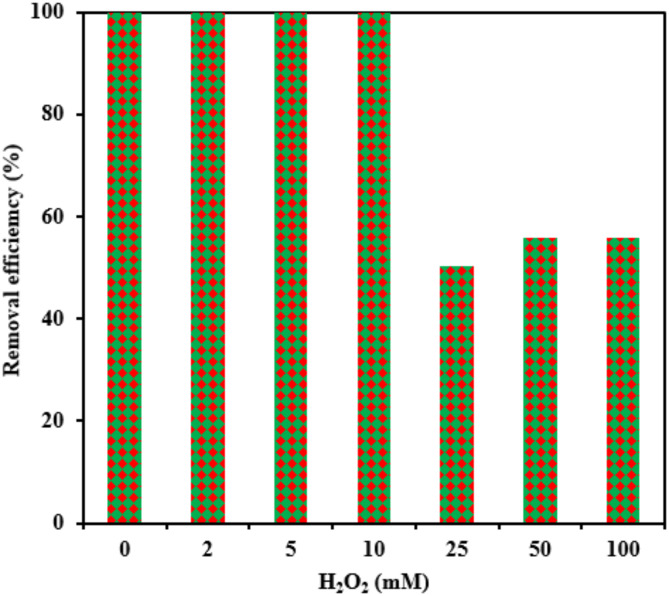

Hydrogen peroxide

The effectiveness of the photocatalyst in eliminating RB5 was evaluated at H2O2 concentrations ranging from 2 to 100 mM, while other parameters, including pH, catalyst dosage, and initial RB5 concentration, were kept constant at 3, 0.5 g L− 1, and 20 mg L− 1, respectively. As shown in Fig. 8, RB5 photo-degradation efficiency reached its maximum at an H2O2 concentration of 10 mM. However, beyond this threshold, degradation efficiency declined. Specifically, as H2O2 concentrations increased from 10 to 100 mM, removal efficiency decreased from 99.99 to 55.86%. The initial enhancement in reaction rate following the addition of H2O2 was attributed to the increased generation of hydroxyl radicals67. Equation (3) suggests that at low concentrations, hydrogen peroxide effectively inhibits electron-hole recombination. Compared to oxygen, hydrogen peroxide has a greater electron-accepting capacity, making it a potential alternative to oxygen as an electron acceptor in photocatalytic reactions.

Fig. 8.

Effect of hydrogen peroxide on the photocatalytic removal of RB5 (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1, pH= 3, [RB5]0= 20 mg L− 1).

|

3 |

At high concentrations, H2O2 has been shown to act as a strong scavenger of hydroxyl radicals (·OH), leading to a reduction in the efficiency of RB5 photocatalytic degradation, as outlined in Eqs. (4–6)67. Similar observations have also been reported in previous studies on dye removal43,45.

|

4 |

|

5 |

|

6 |

Gases

The graph in Fig. 9 illustrates the effectiveness of different gases (bubbling of O2 and N2 gas) in the photocatalytic elimination of RB5 while the other parameters like pH, [RB5]0 and catalyst dosage were kept constant at 3, 20 mg L− 1 and 0.5 g L− 1, respectively. It is evident that removing RB5 from ambient condition was more successful than when exposed to O2 and N2 gas, with the efficiency dropping from 99.99 to 98.33% and 68.19%, respectively. The removal efficiency was higher in an oxygen-rich environment compared to nitrogen exposure. When the catalyst is irradiated with photons of appropriate energy, electrons in the valence band gain sufficient energy to transition to the conduction band, generating electron-hole pairs that migrate to the photocatalyst surface31,43,44. These separated charges initiate oxidation-reduction reactions between oxygen and water molecules, leading to the production of reactive oxygen species such as hydrogen peroxide. Photogenerated holes on the catalyst surface interact with hydroxyl ions, forming highly reactive oxygen species, including OH·, OH2·, and H2O2. Meanwhile, electrons from the reaction are captured by oxygen molecules introduced via bubbling, generating additional oxygen-active species such as O2·−, which further enhances photocatalytic efficiency. In contrast, when nitrogen is bubbled into the reaction suspension, the photocatalytic removal efficiency of RB5 decreases. Unlike oxygen, nitrogen cannot act as an electron acceptor, resulting in the depletion of oxygen molecules from the solution. These findings align with previous studies, which also reported a reduction in RB5 removal efficiency in the presence of nitrogen and oxygen gases31.

Fig. 9.

Effect of purging of different gases on the photocatalytic removal of RB5 (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1, pH= 3, [RB5]0= 20 mg L− 1).

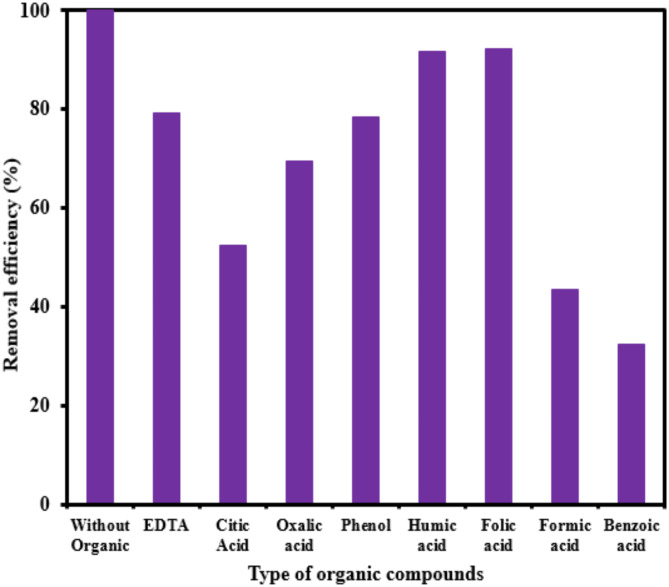

Organic compounds

The graph in Fig. 10 illustrates the effectiveness of different organic compounds (humic acid, oxalic acid, ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA), citric acid, folic acid, formic acid, phenol, benzoic acid) in the photocatalytic elimination of RB5 while the other parameters like pH, [RB5]0 and catalyst dosage were kept constant at 3, 20 mg L− 1, and 0.5 g L− 1, respectively. As the different organic compounds were added to system, the rate of photocatalytic degradation typically decreased. As shown in Fig. 10, by adding humic acid, oxalic acid, EDTA, citric acid, folic acid, phenol, formic acid and benzoic acid to the solution, the efficiency reduced from 99.99 to 91.56, 69.56, 79.23, 52.3, 92.3, 78.36, 43.56 and 32.36%, respectively. The decrease in catalytic activity is thought to be caused by organic compounds taking up space on the catalyst’s active sites, limiting the amount of space available for the desired compound43. A potential cause for the decrease may be that the organic compounds act as electron scavengers. These compounds may react with ·OH radicals, impeding the recombination of holes and electrons. Organic compounds also absorb light within a specific range of wavelengths near the maximum emission of the lamp, hindering photons from reaching the catalyst’s surface. The findings of previous studies support ours, which also observed a decrease in the removal efficiency of reactive dye when humic acid was present68.

Fig. 10.

Effect of different organic compounds on the photocatalytic removal of RB5 (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1, pH= 3, [RB5]0= 20 mg L− 1, organic compounds= 20 mg L− 1).

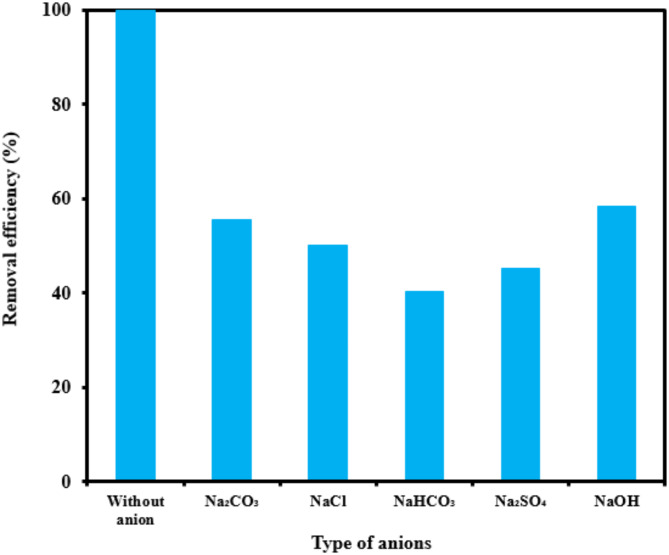

Ionic strength

The graph in Fig. 11 indicates the effectiveness of common inorganic anions (NaOH, NaCl, Na2SO4, Na2CO3 and NaHCO3) in the photocatalytic elimination of RB5 while the other parameters like pH, [RB5]0 and catalyst dosage were kept constant at 3, 20 mg L− 1, and 0.5 g L− 1, respectively. It is clear that all anions lead to a reduction in the rate of photodegradation. As illustrated in Fig. 11, the removal efficiency RB5 decreased from 99.99% to 58.36, 50.23, 45.36, 55.69, and 40.23%, respectively, when NaOH, NaCl, Na2SO4, Na2CO3 and NaHCO3 were added to the solution. These species could inhibit the speed of oxidation by obscuring the active regions on the catalyst or through contesting the photo-oxidizing entities43,69. The inhibitory influence of anions can be attributed to their reaction with positive holes and hydroxyl radicals (Eqs. 7–14), acting as h· and ·OH scavengers, thereby delaying color elimination.

Fig. 11.

Effect of different anions on the photocatalytic removal of RB5 (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1, pH= 3, [RB5]0= 20 mg L− 1, anions= 20 mg L− 1).

|

7 |

|

8 |

|

9 |

|

10 |

|

11 |

|

12 |

|

13 |

|

14 |

Previous studies have suggested that anions are more effective in hindering reaction rates due to their ability to act as scavengers of h+ and ·OH, a finding consistent with the results observed for RB568.

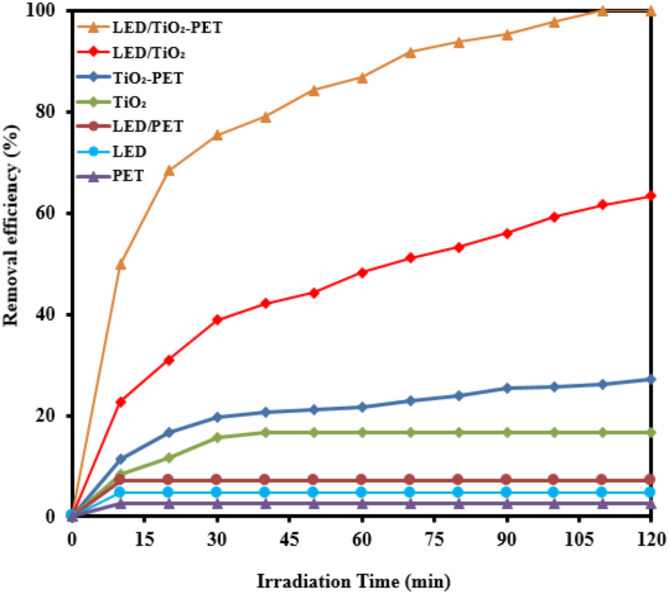

Possible photocatalytic mechanism for RB5 removal by LED/TiO2-PET

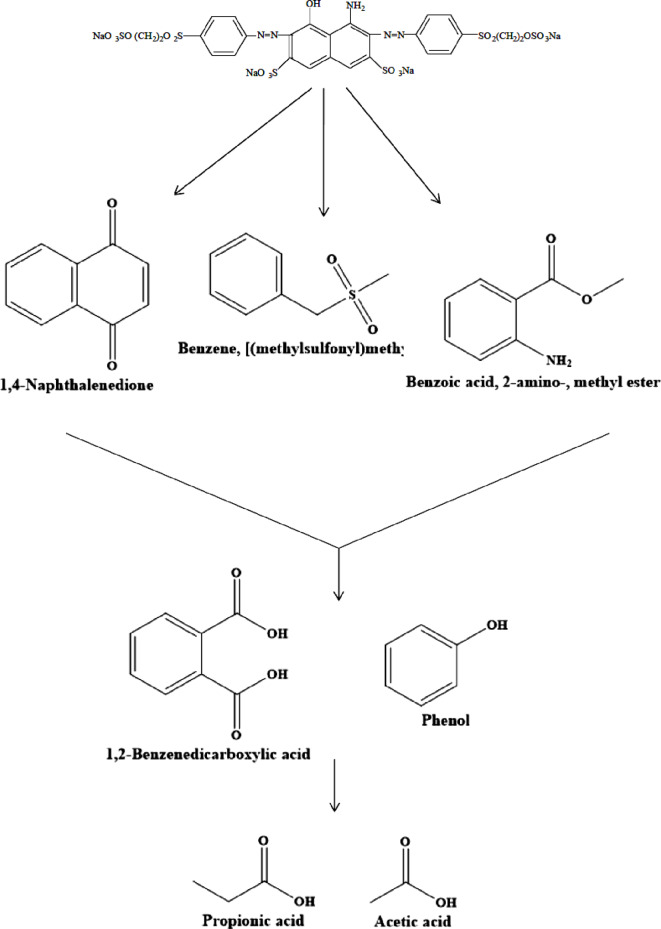

The graph in Fig. 12 presents the effectiveness of different processes in the photocatalytic elimination of RB5 while the other parameters like pH, [RB5]0 and catalyst dosage were kept constant at 3, 20 mg L− 1 and 0.5 g L− 1, respectively. The processes included PET-alone, LED-alone, LED/PET, TiO2−alone, TiO2-PET, LED/TiO2 and LED/TiO2-PET. It is evident that LED/TiO2-PET was the most effective in terms degradation RB5, with a rate of 99.99%. Moreover, in the presence of other processes such as PET-alone, LED-alone, LED/PET, TiO2−alone, TiO2-PET and LED/TiO2 the removal efficiency of RB5 decreased to 2.74, 4.7, 7.2, 16.53, 27.16, 63.42%, respectively. To investigate the types of radicals produced during the photocatalytic activity, radical quenching experiments were conducted in optimized conditions parameters like pH, [RB5]0 and catalyst dosage were kept constant at 3, 20 mg L− 1, and 0.5 g L− 1, respectively. Ammonium oxalate, benzoquinone, and tert-butyl alcohol was used as h+, and ·OH, respectively70. As shown in Fig. 13, in the present of ammonium oxalate, benzoquinone, and tert-butyl alcohol scavengers, the removal efficiency of RB5 went up from 48.029 to 98.17%, 31.14–74.34% and 19.86–58.059% in irradiation time from 10 to 120 min, respectively. While, at the same contact time, the removal efficiency increased from to 49.85–99.99% in the absence of scavenger. The findings suggest that ·OH and

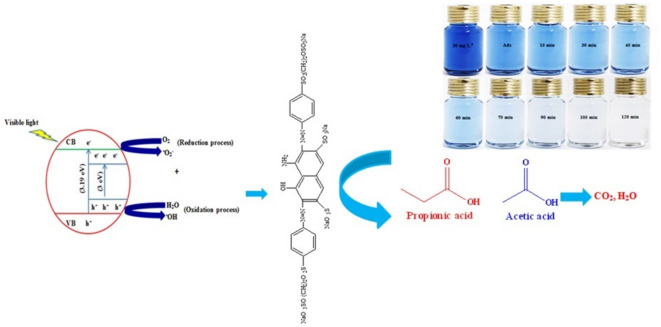

and ·OH, respectively70. As shown in Fig. 13, in the present of ammonium oxalate, benzoquinone, and tert-butyl alcohol scavengers, the removal efficiency of RB5 went up from 48.029 to 98.17%, 31.14–74.34% and 19.86–58.059% in irradiation time from 10 to 120 min, respectively. While, at the same contact time, the removal efficiency increased from to 49.85–99.99% in the absence of scavenger. The findings suggest that ·OH and  were formed in the LED/TiO2-PET process and were the main reactive oxygen species (ROSs) source for the removal of RB5 (Fig. 13). It was found that there was no significant difference in the removal of RB5 when ammonium oxalate was used, suggesting that the reaction of RB5 with h⁺ generated from the reaction of electrons with the TiO2-PET nanocomposite may not be the primary pathway for RB5 removal. Figure 14 illustrates the changes in the absorption spectra of RB5 solutions by the LED/TiO2-PET system at various exposure times. The spectral characteristics of RB5 in the visible region show a significant band at 597 nm. The visible spectrum of RB5 revealed a decrease in the absorption peak at 597 nm, demonstrating the rapid decomposition of the dye molecule. Results showed that the nitrogen double band (–N=N–) of the azo dye was particularly susceptible to oxidation, leading to near complete breakdown over the course of two hours under optimized conditions. A schematic of the proposed pathway for the degradation of RB5 in the LED/TiO₂-PET system was generated based on the observed intermediate products (Fig. 15). The hydroxyl (·OH) radicals generated during the decomposition of the RB5 dye resulted in the cleavage of the –N=N– (azo) bands, producing 1,4-naphthalenedione, benzene, [(methylsulfonyl) methyl], and benzoic acid, 2-amino-, methyl ester. The oxidation of these compounds led to the formation of phenol and 1,2-benzene dicarboxylic acid. In conclusion, the aromatic rings of these compounds underwent further decomposition and degradation, yielding propionic and acetic acids. The illustration in Fig. 16 demonstrates the mechanism of RB5 degradation using the LED/TiO2-PET system. Based on our results, we propose a possible photocatalytic mechanism for the degradation of RB5 by the TiO2-PET hybrid. The UV–Vis spectra and band gap of the TiO₂ nanoparticles and TiO₂-PET nanocomposites were calculated using Tauc plots and are shown in Fig. S2a, b. The band gap energy values of TiO₂ nanoparticles and TiO2-PET nanocomposites were observed to be 3.19 eV and 3 eV, respectively. This reduction in the band gap of the TiO2-PET nanocomposites was attributed to the presence of stacked and porous carbon (according to the EDX results) coated with TiO2 nanoparticles, which develop intermediate states between the conduction band and the valence band across the interface, thus reducing the band gap. The TiO2-PET nanocomposites generate more e⁻ and h⁺ due to the lower band gap, which can produce additional ·OH radicals following the oxidation reaction. Therefore, the increased production of ·OH radicals allows for more degradation of RB5. The enhanced photocatalytic activity of the TiO2-PET nanocomposites is due to the shorter e−/h+ recombination time, narrower band gap (3 eV), and higher surface area compared to pristine TiO2. When the TiO2-PET nanoparticles absorb energy greater than the band gap between the valence and conduction bands, electrons in the VB are excited to the conduction band, leaving behind holes in the VB. These electron-hole pairs have a very short lifespan, typically in the picosecond range, and can migrate to the surface of the semiconductor, facilitating charge transfer (Eq. 15)35,71.

were formed in the LED/TiO2-PET process and were the main reactive oxygen species (ROSs) source for the removal of RB5 (Fig. 13). It was found that there was no significant difference in the removal of RB5 when ammonium oxalate was used, suggesting that the reaction of RB5 with h⁺ generated from the reaction of electrons with the TiO2-PET nanocomposite may not be the primary pathway for RB5 removal. Figure 14 illustrates the changes in the absorption spectra of RB5 solutions by the LED/TiO2-PET system at various exposure times. The spectral characteristics of RB5 in the visible region show a significant band at 597 nm. The visible spectrum of RB5 revealed a decrease in the absorption peak at 597 nm, demonstrating the rapid decomposition of the dye molecule. Results showed that the nitrogen double band (–N=N–) of the azo dye was particularly susceptible to oxidation, leading to near complete breakdown over the course of two hours under optimized conditions. A schematic of the proposed pathway for the degradation of RB5 in the LED/TiO₂-PET system was generated based on the observed intermediate products (Fig. 15). The hydroxyl (·OH) radicals generated during the decomposition of the RB5 dye resulted in the cleavage of the –N=N– (azo) bands, producing 1,4-naphthalenedione, benzene, [(methylsulfonyl) methyl], and benzoic acid, 2-amino-, methyl ester. The oxidation of these compounds led to the formation of phenol and 1,2-benzene dicarboxylic acid. In conclusion, the aromatic rings of these compounds underwent further decomposition and degradation, yielding propionic and acetic acids. The illustration in Fig. 16 demonstrates the mechanism of RB5 degradation using the LED/TiO2-PET system. Based on our results, we propose a possible photocatalytic mechanism for the degradation of RB5 by the TiO2-PET hybrid. The UV–Vis spectra and band gap of the TiO₂ nanoparticles and TiO₂-PET nanocomposites were calculated using Tauc plots and are shown in Fig. S2a, b. The band gap energy values of TiO₂ nanoparticles and TiO2-PET nanocomposites were observed to be 3.19 eV and 3 eV, respectively. This reduction in the band gap of the TiO2-PET nanocomposites was attributed to the presence of stacked and porous carbon (according to the EDX results) coated with TiO2 nanoparticles, which develop intermediate states between the conduction band and the valence band across the interface, thus reducing the band gap. The TiO2-PET nanocomposites generate more e⁻ and h⁺ due to the lower band gap, which can produce additional ·OH radicals following the oxidation reaction. Therefore, the increased production of ·OH radicals allows for more degradation of RB5. The enhanced photocatalytic activity of the TiO2-PET nanocomposites is due to the shorter e−/h+ recombination time, narrower band gap (3 eV), and higher surface area compared to pristine TiO2. When the TiO2-PET nanoparticles absorb energy greater than the band gap between the valence and conduction bands, electrons in the VB are excited to the conduction band, leaving behind holes in the VB. These electron-hole pairs have a very short lifespan, typically in the picosecond range, and can migrate to the surface of the semiconductor, facilitating charge transfer (Eq. 15)35,71.

Fig. 12.

Contribution of each process involved in the photocatalytic removal of RB5 (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1, pH= 3, [RB5]0= 20 mg L− 1).

Fig. 13.

Effect of active scavenger species on the photocatalytic removal of RB5 (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1, pH= 3, [RB5]0= 20 mg L− 1).

Fig. 14.

2 Spectral changes of RB5 solution during illumination in the presence of TiO2-PET (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L-1, pH=3, [RB5]0=20 mg L-1.

Fig. 15.

RB5 decomposition pathways determined by GC-MS data at 280 °C (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1, pH= 3, [RB5]0= 20 mg L− 1).

Fig. 16.

Mechanism of the photocatalytic removal of RB5 using the TiO2-PET under LED visible light irradiation. t = − 1, 50= − 1).

| 15 |

Electrons and holes can move within and between semiconductor particles, recombine, and become inactive, releasing energy in the form of heat or light (Eq. 16).

|

16 |

Generally, the presence of oxygen in the atmosphere will lead to the formation of superoxide radical anions (O−22−). In an aqueous surrounding, the absence of electrons (holes) will cause water molecules or hydroxyl ions (OH−) that have adsorbed on the surface of titanium dioxide to react and form highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (OH) (Eqs. 17–24).

|

17 |

|

18 |

|

19 |

|

20 |

|

21 |

|

22 |

|

23 |

|

24 |

Radicals with high redox capacity can break down the chemical bands in organic compounds, such as C–C and C–O bands, leading to decomposition and oxidation into CO2, H2O, and other inorganic molecules (Eq. 25). Due to their strong oxidative power, they can be used to treat various types of chemicals without producing intermediate products.

|

25 |

A comparison of RB5 degradation using different catalysts, based on removal efficiency and kinetic constants, has been shown in Table S3.

Reusability

The stability and recyclability of TiO2-PET catalysts in the photodegradation of RB5 dye were evaluated by conducting five successive cycles of RB5 dye removal under LED irradiation in optimal conditions (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1, [RB5]0= 20 mg L− 1, pH= 3). The samples from the photocatalytic reactions were thoroughly rinsed multiple times with deionized water and a 2 M NaOH solution as a desorbing agent, followed by heating in an oven until completely dry, and then set aside for use in future operations. The results shown in Fig. 17 indicate that, even after 120 min, the removal efficiency of RB5 remained consistent after five repetitions of the experiment. The crystalline structure of TiO2-PET was also analyzed using XRD measurements taken before and after five cycles. The structure of the catalyst remained unchanged and was comparable to the initial sample (Fig. 1). The study demonstrates that TiO₂-PET could be a practical material for the elimination of RB5 dye through photocatalysis, due to its excellent photosensitivity and high reusability. The durability of the catalyst was further assessed at different pH levels of the solution. The pHPZC indicated that the nanocomposite was stable under acidic conditions (pH > 2).

Fig. 17.

i2Reusability test for the photocatalytic removal of RB5 within five repeated cycles (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1, pH= 3, [RB5]0=20 mg L− 1).

Treatment of an actual water sample containing RB5

To assess the efficacy of the LED/TiO2-PET technique for removing RB5 from actual water, 20 mg L− 1 of RB5 was added to a water sample collected from Rasht City’s distribution system in Iran. The properties of the real water sample are described in Table S472. As shown in Fig. 18, synthetic water demonstrated better removal efficiency for RB5 than drinking water. The scavenging of hydroxyl radicals by anions such as sulfate, chloride, carbonate, and bicarbonate is responsible for the inhibition, which occurs through Eqs. (7–14)73. These ions could also interfere with the active sites on the TiO2-PET surface, hindering the catalyst’s ability to interact with RB5 and the associated molecules. Evidence suggests that the oxidizing power of the radical anions generated is weaker than that of hydroxyl radicals. The pH level of the real water, influenced by the presence of carbonate and bicarbonate ions, may be higher than that of distilled water, which could contribute to the reduced photodegradation efficiency in real water compared to distilled water. The solution’s specific conductivity increased from 0.76 to 0.92 after the LED/TiO2-PET process, likely due to the formation of sulfate, phosphate, and nitrate during the photocatalytic removal of RB5.

Fig. 18.

Investigation of the efficiency of LED/TiO2-PET process in removal of RB5 from real drinking water (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1, [RB5]0= 20 mg L− 1).

RB5 removal from textile industry wastewater

This study assessed the effectiveness of TiO2-PET photocatalysis in removing RB5 from wastewater samples collected from the textile industry in Rasht, Iran. Table 2 provides an overview of the composition of the textile effluent before and after treatment. Prior to the experiments, the wastewater sample was allowed to settle for 24 h, after which it was filtered. The filtered sample was then used in the photocatalytic removal of RB5. The initial measurements of the textile wastewater showed a COD of 1480 mg L− 1, BOD of 325 mg L− 1, TSS of 1250 mg L− 1, color of 90 PCU, and a pH value of 8.5. After treatment through LED/TiO2-PET, the COD, BOD, TSS, and color of the final product were reduced to 115 mg L− 1, 45 mg L− 1, 129 mg L− 1, and 3 PCU, respectively, all of which are below the National Environmental Quality Standards (NEQS) established for textile effluent. The effectiveness of LED/TiO2-PET in removing color from actual textile wastewater is presented in Fig. 19; the process was found to be 96.66% successful in decreasing the color parameter from 90 PCU to 3 PCU. The removal of color from textile industry wastewater also contributed to a reduction in COD and BOD, as the complex dyes were broken down into simpler molecules that are less harmful and more easily biodegraded during wastewater treatment by the LED/TiO2-PET process. As a result of this research, the levels of COD, BOD, and TSS were reduced to 115 mg L− 1, 45 mg L− 1, and 129 mg L− 1, respectively, which correspond to removal rates of 92.22, 86.15, and 89.68%. Similar observations have also been reported for the removal of dyes23,74.

Table 2.

Characteristics of real textile effluent before and after the treatment at LED/TiO2-PET process (dose= 0.5 g L−1 within 120 min).

| Parameters (mg L− 1) | Before treatment | After treatment | National environmental quality standards (NEQS) of textile effluent |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 8.5 | 6.8 | 7 |

| COD | 1480 | 115 | 150 |

| BOD | 325 | 45 | 80 |

| TSS | 1250 | 129 | 150 |

| TDS | 2850 | 2770 | 3500 |

| Color (PCU) | 90 | 3 | 7 |

Fig. 19.

Decolonization using of the LED/TiO2-PET process and its comparison with National Environmental Quality Standards (NEQS) of Textile Effluent (catalyst dosage= 0.5 g L− 1).

Toxicity

The Table 3 displays the results of an acute toxicity test, including the 12 to 96-h LC50 values and confidence limits, as well as the TU value. After the treatment, the 48-h LC50 values were 2.991% for the textile industry outlet effluent, 102.87% for the synthetic effluent, 5238.05 mg L− 1 for TiO2-PET, 11.19 mg L− 1 for RB5, 2081.19 mg L− 1 for PET, and 1210.75 mg L− 1 for TiO2. Table 3 shows that TiO2-PET nanocomposite are not hazardous to aquatic life, suggesting that this catalyst could be employed in photocatalytic processes without adversely affecting aquatic species. The result illustrates that the photocatalytic process by means of the LED/TiO2-PET caused the decrease of toxicity of effluent significantly. Nunes et al. stated that Sr0.95Bi0.05TiO3 is an effective photocatalyst for decomposing the AO7 dye under visible light, and it can likewise effectively eliminate the toxic metabolites, thus yielding a final solution that is not harmful to D. magna. Mengelizadeh et al.10 reported GO-CoFe2O4 for the degradation of RB5, results from Daphnia pulex toxicity tests indicated that the treated effluent needed additional catalytic treatment and better stabilization because of the presence of cobalt ions and intermediates. Kunz et al.75 explained that ozonation was used for the degradation of RB5. The results from Vibrio fischeri toxicity tests indicated that the increase in toxicity after treatment was due to the presence of copper ions formed by the intermediates following oxidation.

Table 3.

The findings of the acute toxicity test 12 to 96-h LC50values, confidence limits and TU.

| Samples | PET | TiO2 | TiO2-PET | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (h) | LC50 (mg L− 1) |

95% Confidence Limits | TU | NOEC (mg L− 1) | 100% mortality | LC50 (mg L− 1) | 95% Confidence Limits | TU | NOEC (mg L− 1) | 100% mortality | LC50 (%) | 95% Confidence Limits | TU | NOEC (%) | 100% mortality | |||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||||||||||

| 12 | 7811.35 | 4665.92 | 31,808.6 | 0.012 | 324.33 | 188,132.15 | 4249.51 | 2614.603 | 9094.171 | 0.0235 | 153.140 | 117,921 | 12,452 | 6939.159 | 2,023,332.785 | 0.008 | 984.836 | 157,441 |

| 24 | 4249.51 | 2614.6 | 9049.17 | 0.023 | 153.139 | 117,921.21 | 2233.45 | 1382.749 | 3888.415 | 0.0447 | 77.668 | 64,226.6 | 9987.35 | 5329.034 | 79,326.809 | 0.01 | 320.046 | 311,665 |

| 48 | 2081.19 | 1299.41 | 3512.55 | 0.048 | 81.31 | 53,266.14 | 1210.75 | 765.922 | 1890.262 | 0.0825 | 64.999 | 22,552.7 | 5238.05 | 3041.115 | 14,309.278 | 0.019 | 129.815 | 211,356 |

| 72 | 921.91 | 559.52 | 1480.06 | 0.108 | 35.23 | 24,121.3 | 921.65 | 544.541 | 1730.052 | 0.108 | 31.369 | 27,078.5 | 3229.54 | 1836.278 | 7442.097 | 0.03 | 47.658 | 218,849 |

| 96 | 519.51 | 291.04 | 894.51 | 0.192 | 12.73 | 21,186.39 | 526.688 | 337.52 | 807.396 | 0.189 | 48.784 | 5686.33 | 1606.92 | 957.702 | 2809.524 | 0.0622 | 39.445 | 65,463.4 |

| Samples | RB5 | Synthetic effluent | Textile industry outlet effluent after treatment | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (h) | LC50 (mg L− 1) |

95% confidence limits | TU | NOEC (mg L− 1) | 100% mortality | LC50 mg L− 1) | 95% confidence limits | TU | NOEC (mg L− 1) | 100% mortality | LC50 (%) | 95% confidence limits | TU | NOEC (%) | 100% mortality | |||

| Lower bound | Upper bound | Lower bound | Upper bound | Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||||||||||

| 12 | 20.72 | 17.14 | 25.45 | 4.82 | − 3.56 | 45 | 185.409 | – | – | 0.539 | 35.421 | 970.502 | 7.809 | 4.97 | 11.674 | 12.805 | 0.448 | 135.983 |

| 24 | 13.58 | 11.17 | 16.9 | 7.36 | − 1.6 | 28.77 | 142.708 | – | – | 0.7 | 29.952 | 679.904 | 4.589 | 2.893 | 6.858 | 21.791 | 0.346 | 60.805 |

| 48 | 11.19 | 8.99 | 14.22 | 8.93 | − 3.4 | 25.78 | 102.87 | 76.045 | 669.571 | 0.972 | 24.121 | 437.714 | 2.991 | 1.84 | 4.561 | 33.433 | 0.263 | 34.07 |

| 72 | 8.87 | 6.91 | 11.5 | 11.27 | − 4.41 | 22.17 | 80.603 | 60.941 | 141.926 | 1.24 | 20.393 | 318.586 | 2.337 | 1.379 | 3.789 | 42.789 | 0.192 | 28.441 |

| 96 | 7.18 | 5.22 | 10 | 13.92 | − 6.37 | 20.74 | 64.827 | 48.144 | 99.131 | 1.542 | 17.489 | 240.299 | 1.757 | – | – | 56.91 | 0.167 | 18.465 |

Cost analysis

It is essential to assess the economics of the RB5 degradation approach to determine its feasibility for large-scale commercialization. The costs associated with this technique include capital, operating, and maintenance expenses. The operating cost is influenced by factors such as the characteristics of the contaminant, its concentration, contact time, amount of catalyst used, and the arrangement of the reactor. An economic assessment was conducted to evaluate the operational expenditures related to the photocatalytic degradation of RB5 from aqueous solutions using various processes (LED, LED/PET, LED/TiO2, LED/TiO2-PET) under optimal conditions (pH= 3, TiO2-PET= 0.5 g L− 1, contact time= 120 min, [RB5]₀= 20 mg L− 1, LED light power = 15 W). The operating cost of removing RB5 from aqueous solutions was calculated in US Dollars (USD) per kilogram (kg) based on Eqs. (26) and (27)60.

|

26 |

|

27 |

The results of a cost comparison and energy efficiency calculated for the photocatalytic degradation of RB5 are presented in Table 4. The total energy consumed for 120 min of RB5 treatment using LED-based system is 0.03 kWh. In addition, the total operating cost for the LED/TiO2-PET (3 USD kg− 1) process was less than that for other photocatalytic processes including LED/TiO2 (4.73 USD kg− 1), LED/PET (40 USD kg− 1) and LED (63.16 USD kg− 1). The energy efficiency calculated for the LED/TiO2-PET (1.18 × 10− 7 mg J− 1) process was higher than other photocatalytic processes including LED/TiO2 (7.49 × 10− 8 mg J− 1), LED/PET (8.57 × 10− 9 mg J− 1) and LED (5.5 × 10− 9 mg J− 1). The findings for the EEO of the various concentration and processes studied in this work have been shown in Tables 1 and 4, respectively. The EEO rose drastically from 11.08 to 338.824 kWh m− 3 as the RB5 concentration was increased from 10 to 50 mg L− 1. EEO (kWh m− 3) value for LED/TiO2-PET (5561.26) process was lower that for LED/TiO2 (68689.4), LED/PET (923153.2) and LED (1431898.7) processes. Thus, the LED/TiO2-PET process is more economical than LED/TiO2, LED/PET and LED. LED/TiO2-PET is seen to be an economical and efficacious catalyst for the removal of RB5, based on cost-effectiveness analysis and its capacity for degradation. Khan et al.17 reported that EEO for visible light/Fe-TiO2 was 207 KWh m− 3, while the cost was 33 USD for removal of RB5. Mohagheghian et al.76 reported that EEO for visible light/ZnO-Perlite was 20.65 KWh m− 3 while the cost was 3.11 USD kg− 1 for removal of RB5. Akbarzadeh et al.77 reported operational cost 8.7205 USD kg− 1 for removal of methylene blue in the UV/Vanadium-TiO2 process.

Table 4.

Comparison of cost analysis and energy efficiency for photocatalytic removal of RB5.

| System | RB5 removal (%) | EEO (kWh m− 3) | Total power consumed (kWh) | Total operation cost (USD kg− 1) | Energy delivered/volume (J L− 1) | Energy efficiency (mg J− 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LED | 4.7 | 1,431,898.7 | 0.03 | 63.16 | 1.692 × 108 | 5.5 × 10− 9 |

| LED/PET | 7.2 | 923,153.2 | 0.03 | 40 | 1.692 × 108 | 8.57 × 10− 9 |

| LED/TiO2 | 63.41 | 68,689.4 | 0.03 | 4.73 | 1.692 × 108 | 7.94 × 10− 8 |

| LED/TiO2-PET | 99.99 | 5561.26 | 0.03 | 3 | 1.692 × 108 | 1.18 × 10− 7 |

Conclusions

The TiO2 coated on PET was successfully synthesized using a simple co-precipitation method. The formation of TiO2 on PET was confirmed through XRD, FT-IR, SEM, and EDX-MAP analysis. Maximum RB5 removal (99.99%) was achieved under the following conditions: pH 3, irradiation time of 120 min, catalyst dosage of 0.5 g L− 1, and RB5 dye concentration of 20 mg L− 1. The presence of H2O2, purging gases, organic compounds, and ionic strength negatively affected RB5 removal. According to the Langmuir–Hinshelwood kinetic model, the values for KRB5 and KC were 0.1636 L mg− 1 and 0.1309 mg L− 1 min− 1, respectively. Radical quenching tests identified OH· as the most active radical in RB5 removal. Additionally, the total operating cost for the LED/TiO₂-PET process was 3 USD kg− 1, which is lower than that of other photocatalytic processes. The reusability of TiO₂ coated on PET was evaluated, showing successful reuse up to 5 cycles. The major photocatalytic pathway for the azo-dye Reactive Black 5 was proposed based on the identification of by-products using GC-MS. Acute toxicity tests carried out using Daphnia magna demonstrated that the produced nanocatalyst did not exhibit harmful effects on aquatic organisms, indicating its safe use for wastewater treatment. The TiO₂-coated PET-based photocatalytic treatment was efficient for RB5 removal under visible light irradiation, making it a viable option for treating textile effluents containing dyes.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

AcknowledgmentThis article is based on an integrated research project with code number 15818455 and Irandoc code 1759804, which was part of the master’s dissertation of Seyedeh-Khadijeh Mousavi. The authors would like to acknowledge the University of Guilan and the Department of Environmental Science, Faculty of Natural Resources, for their financial support of this research. Additionally, the authors express their gratitude to the Vice Chancellor of Research and Technology, as well as the Research Center of Health and Environment at Guilan University of Medical Sciences (GUMS), Rasht, Iran, for providing essential support throughout this work.

Author contributions

M.M.G.: Supervisor, design of the project, visualization, conceptualization, investigation, methodology, software, data curation, writing- original draft, responding to reviewers and revising the manuscript. S.-K.M.: Design of the project, methodology, software, data curation. M.S.-S.: Supervisor, design of the project, visualization, conceptualization, investigation, methodology, software, data curation, writing-original draft, responding to reviewers and revising the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wagh, S. S. et al. Rapid photocatalytic dye degradation, enhanced antibacterial and antifungal activities of silver stacked zinc oxide garnished on carbon nanotubes. Sci. Rep.14, 14045. 10.1038/s41598-024-64746-6 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vijayarengan, P. et al. Highly efficient visible light active iron oxide-based photocatalysts for both hydrogen production and dye degradation. Sci. Rep.14, 18299. 10.1038/s41598-024-69413-4 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taghavi Fardood, S., Ganjkhanlu, S., Moradnia, F. & Ramazani, A. Green synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic activity of superparamagnetic MgFe2O4@ ZnAl2O4 nanocomposites. Sci. Rep.14, 16670. 10.1038/s41598-024-67655-w (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asgari, G., Seid-Mohammadi, A., Rahmani, A., Shokoohi, R. & Abdipour, H. Concurrent elimination of arsenic and nitrate from aqueous environments through a novel nanocomposite: Fe3O4-ZIF8@ eggshell membrane matrix. J. Mol. Liq. 411, 125810. 10.1016/j.molliq.2024.125810 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asgari, G. et al. The catalytic ozonation of Diazinon using nano-MgO@ CNT@ Gr as a new heterogenous catalyst: the optimization of effective factors by response surface methodology. RSC Adv.10, 7718–7731. 10.1039/C9RA10095D (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khedr, A. I. & Ali, M. H. Eco-friendly fabrication of copper oxide nanoparticles using Peel extract of citrus aurantium for the efficient degradation of methylene blue dye. Sci. Rep.14, 29156. 10.1038/s41598-024-79589-4 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asgari, G., Shabanloo, A., Salari, M. & Eslami, F. Sonophotocatalytic treatment of AB113 dye and real textile wastewater using ZnO/persulfate: modeling by response surface methodology and artificial neural network. Environ. Res.184, 109367. 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109367 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagheri, M., Roshanaei, G., Asgari, G., Chavoshi, S. & Ghasemi, M. Application of carbon-doped nano-magnesium oxide for catalytic ozonation of real textile wastewater: fractional factorial design and optimization. Desalin. Water Treat.175, 79–89. 10.5004/dwt.2020.24893 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 9.da Silva, É. F. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of RB5 textile dye using immobilized TiO2 in brass structured systems. Catal. Today. 383, 173–182. 10.1016/j.cattod.2021.02.006 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mengelizadeh, N., Mohseni, E. & Dehghani, M. H. Heterogeneous activation of peroxymonosulfate by GO-CoFe2O4 for degradation of reactive black 5 from aqueous solutions: optimization, mechanism, degradation intermediates and toxicity. J. Mol. Liq. 327, 114838. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114838 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdipour, H. & Asgari, G. Enhanced methylene blue degradation and miniralization through activated persulfate coupled with magnetic field. Clean. Eng. Technol.23, 100822. 10.1016/j.clet.2024.100822 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marhalim, M. A. A. et al. Enhanced performance of lanthanum orthoferrite/chitosan nanocomposites for adsorptive photocatalytic removal of reactive black 5. Korean J. Chem. Eng.38, 1648–1659. 10.1007/s11814-021-0835-z (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu, Y. H., Kuo, Y. S., Liu, W. C. & Chou, W. L. Photoelectrocatalytic activity of perovskite YFeO3/carbon fiber composite electrode under visible light irradiation for organic wastewater treatment. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng.128, 227–236. 10.1016/j.jtice.2021.08.029 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dadashi, R., Bahram, M., Farhadi, K., Asadzadeh, Z. & Hafezirad, J. Photodecoration of tungsten oxide nanoparticles onto eggshell as an ultra-fast adsorbent for removal of MB dye pollutant. Sci. Rep.14, 14478. 10.1038/s41598-024-65573-5 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Ansari, S. H., Gomaa, H., Abdel-Rahim, R. D., Ali, G. A. & Nagiub, A. M. Recycled gold-reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite for efficient adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of crystal violet. Sci. Rep.14, 4379. 10.1038/s41598-024-54580-1 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, F. et al. Peroxymonosulfate enhanced photocatalytic degradation of reactive black 5 by ZnO-GAC: key influencing factors, stability and response surface approach. Sep. Purif. Technol.279, 119754. 10.1016/j.seppur.2021.119754 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan, M. S. et al. Synthesis and characterization of Fe-TiO2 nanomaterial: performance evaluation for RB5 decolorization and in vitro antibacterial studies. Nanomater11, 436. 10.3390/nano11020436 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balci, B. et al. Sequential Fe2O3-powdered activated carbon/activated sludge process for the removal of reactive black 5 and chemical oxygen demand from simulated textile wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Res.17, 11. 10.1007/s41742-022-00500-y (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Semiz, L. Removal of reactive black 5 from wastewater by membrane filtration. Polym. Bull.77, 3047–3059. 10.1007/s00289-019-02896-8 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucas, M. S., Amaral, C., Sampaio, A., Peres, J. A. & Dias, A. A. Biodegradation of the Diazo dye reactive black 5 by a wild isolate of Candida oleophila. Enzyme Microb. Technol.39, 51–55. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2005.09.004 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tlaiaa, Y. S., Naser, Z. A. R. & Ali, A. H. Comparison between coagulation and electrocoagulation processes for the removal of reactive black dye RB-5 and COD reduction. Desalin. Water Treat.195, 154–161. 10.5004/dwt.2020.25914 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren, H. T. et al. Photocatalytic oxidation of aqueous ammonia by Ag2O/TiO2 (P25): new insights into selectivity and contributions of different oxidative species. Appl. Surf. Sci.504, 144433. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.144433 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ambaye, T. G. & Hagos, K. Photocatalytic and biological oxidation treatment of real textile wastewater. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng.5, 1–11. 10.1007/s41204-020-00094-w (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamad, H. et al. Cellulose-based materials in tailoring a novel defective titanium–carbon–phosphorus hybrid composites for highly efficient photocatalytic activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.270, 132304. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132304 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samy, M. et al. Efficient degradation of polyethylene (PE) plastics by a novel vacuum ultraviolet-activated periodate system: operating parameters, by-products, and toxicity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.12, 114848. 10.1016/j.jece.2024.114848 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaber, M. M., Samy, M., Azam, A. & Shokry, H. Remediation of paracetamol-contaminated water by novel burned Hookah charcoal residues via persulfate activation under visible light: optimization, mechanism, and real pharmaceutical wastewater application. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.12, 114399. 10.1016/j.jece.2024.114399 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asgari, G., Seidmohammadi, A., Salari, M., Ramavandi, B. & Faradmal, J. Catalytic ozonation assisted by rGO/C-MgO in the degradation of humic acid from aqueous solution: modeling and optimization by response surface methodology, kinetic study. Desalin. Water Treat.174, 215–229. 10.5004/dwt.2020.24869 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asgari, G., Seidmohammadi, A., Rahmani, A. R., Samarghandi, M. R. & Faraji, H. Application of the UV/sulfoxylate/phenol process in the simultaneous removal of nitrate and Pentachlorophenol from the aqueous solution. J. Mol. Liq. 314, 113581. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113581 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arslan, I., Balcioglu, I. A. & Tuhkanen, T. Advanced oxidation of synthetic dyehouse effluent by O3, H2O2/O3 and H2O2/UV processes. Environ. Technol.20, 921–931. 10.1080/09593332008616887 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laohaprapanon, S., Matahum, J., Tayo, L. & You, S. J. Photodegradation of reactive black 5 in a ZnO/UV slurry membrane reactor. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng.49, 136–141. 10.1016/j.jtice.2014.11.017 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wongkalasin, P., Chavadej, S. & Sreethawong, T. Photocatalytic degradation of mixed Azo dyes in aqueous wastewater using mesoporous-assembled TiO2 nanocrystal synthesized by a modified sol–gel process. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 384, 519–528. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2011.05.022 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shabil Sha, M. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes using reduced graphene oxide (rGO). Sci. Rep.14, 3608. 10.1038/s41598-024-53626-8 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sayed, M. M. et al. The enhanced photocatalytic performance of CPAA doping with different concentrations of titanium oxide nanocomposite against MB dyes under simulated sunlight irradiations. Sci. Rep.14, 12768. 10.1038/s41598-024-61983-7 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samy, M., Tang, S., Zhang, Y. & Leung, D. Y. Understanding the variations in degradation pathways and generated by-products of antibiotics in modified TiO2 and ZnO photodegradation systems: A comprehensive review. J. Environ. Manag.370, 122402. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122402 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lian, P., Qin, A., Liao, L. & Zhang, K. Progress on the nanoscale spherical TiO2 photocatalysts: mechanisms, synthesis and degradation applications. Nano Sel.2, 447–467. 10.1002/nano.202000091 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marcelino, R. B., Amorim, C. C., Ratova, M., Delfour-Peyrethon, B. & Kelly, P. Novel and versatile TiO2 thin films on PET for photocatalytic removal of contaminants of emerging concern from water. Chem. Eng. J.370, 1251–1261. 10.1016/j.cej.2019.03.284 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeghioud, H. et al. Photocatalytic performance of TiO2 impregnated polyester for the degradation of reactive green 12: implications of the surface pretreatment and the microstructure. J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem.346, 493–501. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2017.07.005 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahmoodi, F., Jalilzadeh Yengejeh, R., Tirgir, F. & Sadeghi, M. Removal of 1-naphthol from water via photocatalytic degradation over N,S-TiO2/ silica sulfuric acid under visible light. J. Adv. Environ. Health Res.10, 59–72. 10.32598/jaehr.10.1.1242 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou, K. et al. Synthesized TiO2/ZSM-5 composites used for the photocatalytic degradation of Azo dye: intermediates, reaction pathway, mechanism and bio-toxicity. Appl. Surf. Sci.383, 300–309. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.04.155 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pourrahmati-Shiraz, M., Mohagheghian, A. & Shirzad-Siboni, M. Synthesis of ZnO immobilized on recycled polyethylene terephtalate for sonocatalytic removal of cr (VI) from synthetic, drinking waters and electroplating wastewater. J. Environ. Manag.324, 116395. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116395 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ribeiro, L. N. et al. Residue-based TiO2/PET photocatalytic films for the degradation of textile dyes: A step in the development of green monolith reactors. Chem. Eng. Process Process. Intensif.147, 107792. 10.1016/j.cep.2019.107792 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghobashy, M. M. Combined ultrasonic and gamma-irradiation to prepare TiO2@ PET-g-PAAc fabric composite for self-cleaning application. Ultrason. Sonochem. 37, 529–535. 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.02.014 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohagheghian, A., Ayagh, K., Godini, K. & Shirzad-Siboni, M. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of Fe3O4-WO3-APTES for Azo dye removal from aqueous solutions in the presence of visible irradiation. Part. Sci. Technol.37, 358–370. 10.1080/02726351.2017.1376363 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Konstantinou, I. K. & Albanis, T. A. TiO2-assisted photocatalytic degradation of Azo dyes in aqueous solution: kinetic and mechanistic investigations: a review. Appl. Catal. B. 49, 1–14. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2003.11.010 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daneshvar, N., Salari, D. & Khataee, A. Photocatalytic degradation of Azo dye acid red 14 in water on ZnO as an alternative catalyst to TiO2. J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem.162, 317–322. 10.1016/S1010-6030(03)00378-2 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shirzad Siboni, M., Samadi, M. T., Yang, J. K. & Lee, S. M. Photocatalytic removal of cr (VI) and Ni (II) by UV/TiO2: kinetic study. Desalin. Water Treat.40, 77–83. 10.1080/19443994.2012.671144 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shirzad-Siboni, M., Khataee, A., Vafaei, F. & Joo, S. W. Comparative removal of two textile dyes from aqueous solution by adsorption onto marine-source waste shell: kinetic and isotherm studies. Korean J. Chem. Eng.31, 1451–1459. 10.1007/s11814-014-0085-4 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rice, E. W. & Bridgewater, L. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, vol. 10 (American Public Health Association, 2012).

- 49.Ko, S., Kwon, Y. J., Lee, J. U. & Jeon, Y. P. Preparation of synthetic graphite from waste PET plastic. J. Ind. Eng. Chem.83, 449–458. 10.1016/j.jiec.2019.12.018 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naimi-Joubani, M., Shirzad-Siboni, M., Yang, J. K., Gholami, M. & Farzadkia, M. Photocatalytic reduction of hexavalent chromium with illuminated ZnO/TiO2 composite. J. Ind. Eng. Chem.22, 317–323. 10.1016/j.jiec.2014.07.025 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahmad, M. M., Mushtaq, S., Qahtani, A., Sedky, H. S., Alam, M. W. & A. & Investigation of TiO2 nanoparticles synthesized by Sol-Gel method for effectual photodegradation, oxidation and reduction reaction. Cryst11, 1456. 10.3390/cryst11121456 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu, Z., Wang, R., Kan, F. & Jiang, F. Synthesis and characterization of TiO2 nanoparticles. Asian J. Chem.2610.1016/j.ceramint.2010.04.006 (2014).

- 53.Patterson, A. The scherrer formula for X-ray particle size determination. Phys. Rev.56, 978. 10.1103/PhysRev.56.978 (1939). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sarimov, R. M. et al. Investigation of aggregation and disaggregation of self-assembling nano-sized clusters consisting of individual iron oxide nanoparticles upon interaction with HEWL protein molecules. Nanomater12, 3960. 10.3390/nano12223960 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siboni, M. S., Samarghandi, M., Yang, J. K. & Lee, S. M. Photocatalytic removal of reactive black-5 dye from aqueous solution by UV irradiation in aqueous TiO2: equilibrium and kinetics study. J. Adv. Oxid. Technol.14, 302–307. 10.1515/jaots-2011-0216 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ganesan, S., Kokulnathan, T., Sumathi, S. & Palaniappan, A. Efficient photocatalytic degradation of textile dye pollutants using thermally exfoliated graphitic carbon nitride (TE–g–C3N4). Sci. Rep.14, 2284. 10.1038/s41598-024-52688-y (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dhariwal, N. et al. Synergistic photocatalytic breakdown of Azo dyes coupled with H2 generation via Cr-doped α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Sci. Rep.14, 19916. 10.1038/s41598-024-65672-3 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samy, M. et al. Novel approach to photocatalytic removal of linezolid by advanced Nano-Biochar/Bismuth oxychloride hybrid. ACS Omega. 9, 30963–30974. 10.1021/acsomega.4c04007 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chong, M. N., Cho, Y. J., Poh, P. E. & Jin, B. Evaluation of titanium dioxide photocatalytic technology for the treatment of reactive black 5 dye in synthetic and real Greywater effluents. J. Clean. Prod.89, 196–202. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.11.014 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Balakrishnan, A., Gopalram, K. & Appunni, S. Photocatalytic degradation of 2, 4-dicholorophenoxyacetic acid by TiO2 modified catalyst: kinetics and operating cost analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.28, 33331–33343. 10.1007/s11356-021-12928-4 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bhatt, D. K. & Patel, U. D. Photocatalytic degradation of reactive black 5 using Ag3PO4 under visible light. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 149, 109768. 10.1016/j.jpcs.2020.109768 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kansal, S. K., Kaur, N. & Singh, S. Photocatalytic degradation of two commercial reactive dyes in aqueous phase using nanophotocatalysts. Nanoscale Res. Lett.4, 709–716. 10.1007/s11671-009-9300-3 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khan, M. S. et al. Graphene quantum Dot and iron co-doped TiO2 photocatalysts: synthesis, performance evaluation and phytotoxicity studies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.226, 112855. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112855 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aguedach, A., Brosillon, S. & Morvan, J. Photocatalytic degradation of azo-dyes reactive black 5 and reactive yellow 145 in water over a newly deposited titanium dioxide. Appl. Catal. B. 57, 55–62. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2004.10.009 (2005). [Google Scholar]