Abstract

Approximately 70–80% of breast cancers rely on estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) for growth. The unfolded protein response (UPR), a cellular response to endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS), is an important process crucial for oncogenic transformation. The effect of ERS on ERα expression and signaling remains incompletely elucidated. Here, we focused on the regulatory mechanisms of ERS on ERα expression in ER-positive breast cancer (ER+ BC). Our results demonstrate that ERα protein and mRNA levels in ER+ BC cells are considerably reduced by the ERS inducers thapsigargin (TG) and brefeldin A (BFA) via the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 signaling pathway. ChIP-qPCR and luciferase reporter gene analysis revealed that ERS induction facilitated ATF4 binding to the ESR1 (the gene encoding ERα) promoter region, thereby suppressing ESR1 promoter activity and inhibiting ERα expression. Furthermore, selective activation of PERK signaling or ATF4 overexpression attenuated ERα expression and tumor cell growth both in vitro and in vivo. In conclusion, our results demonstrate that ERS suppresses ERα expression transcriptionally via the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 signaling. Our study provides insights into the treatment of ER+ BC by targeting ERα signaling through selective activation of the PERK branch of the UPR.

Keywords: Breast cancer, ESR1, ERα, Endoplasmic reticulum stress, Unfolded protein response, ATF4

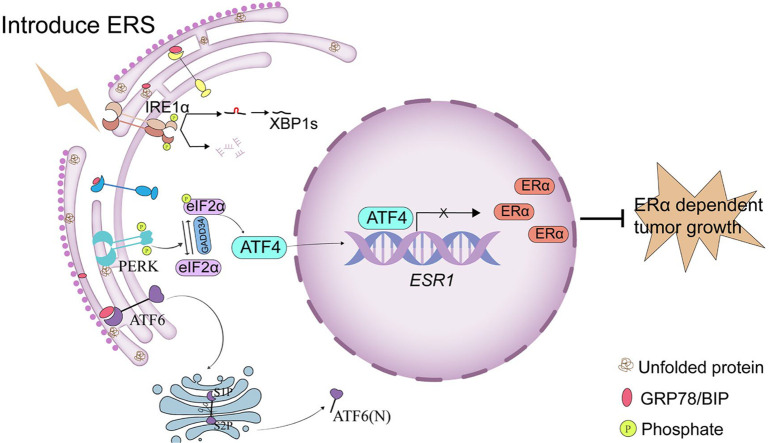

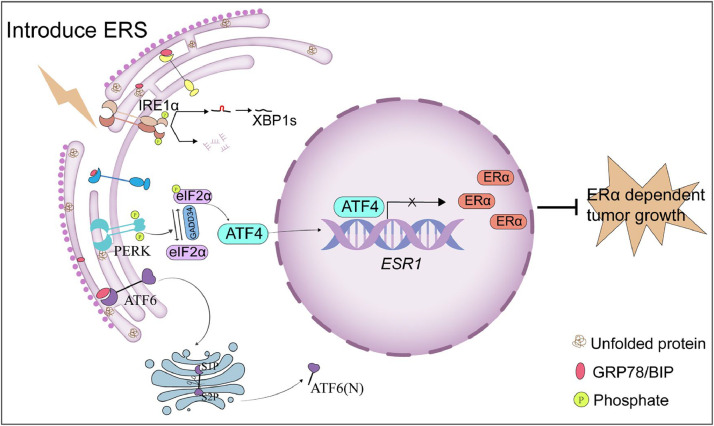

Graphical abstract

ERS activates the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 signaling pathway, leading to ATF4 binding at the ESR1 promoter and repression of transcriptional activity, thereby suppressing ESR1 expression.

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most prevalent and fatal malignancy in women [1]. Based on the expression status of hormone (estrogen or progesterone) receptors (HR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), BC is classified into four molecular subtypes: luminal A, luminal B, HER2-enriched and triple negative breast cancer (TNBC; ER-/PR-/HER2-) [2,3]. Estrogen receptor (ER), the first identified BC biomarker, is expressed in approximately 70–80% of BC cases [4]. Since ERα was first identified by Jensen et al. in 1958 [5], studies have revealed its role in mediating the essential biological functions of estrogen in breast development and tumorigenesis, establishing it as the primary target for endocrine therapy [6]. ERα functions as a transcription factor regulating genes linked to tumor cell proliferation and survival, including insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R), cyclin D1 (CCND1), BCL-2, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Activated ERα signaling induces unique gene expression profiles that influence tumor growth, morphology, and response to endocrine therapy in BC patients [7].

Endoplasmic reticulum, the largest cellular organelle, serves as a platform for protein synthesis, transport, and folding, lipid and steroid synthesis, and calcium storage [8,9]. Numerous external factors and intracellular processes can impair endoplasimc reticulum function, leading to endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS), which is characterized by the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins [10]. Genetic, transcriptional, and metabolic abnormalities prevalent in tumors create unfavorable microenvironments that induce persistent ERS in cancer cells, affecting their function, proliferation, and survival [[11], [12], [13]]. Three endoplasmic reticulum transmembrane proteins – activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), and protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) – serve as ERS sensors in mammalian cells [14]. The immunoglobulin-binding protein (BiP/GRP78) binds to these sensors and maintains their inactive state under normal proteostatic conditions. During ERS, BiP preferentially binds to unfolded/misfolded proteins, dissociating from the sensors and triggering their activation. This initiates the unfolded protein response (UPR), an adaptive program that restores endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis via transcriptional reprogramming, mRNA decay, global translational suppression, ER-associated degradation (ERAD), and autophagy [15]. Activated IRE1 catalyzes non-canonical splicing of X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) mRNA, generating the spliced isoform XBP1s [16]. XBP1s functions as a transcription factor containing a C-terminal basic leucine zipper (b-ZIP) domain, which induces UPR target gene expression [[17], [18], [19]]. Activated PERK phosphorylates eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) at Ser51 [20]. eIF2α phosphorylation attenuates global translation, reducing protein influx into the endoplasmic reticulum and alleviating ERS. Conversely, phosphorylated eIF2α selectively enhances activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) mRNA translation. Under basal conditions, upstream open reading frames (uORFs) in the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) repress ATF4 translation. Phosphorylated eIF2α enables ribosomes to bypass inhibitory uORFs, thereby promoting ATF4 synthesis [21]. Elevated ATF4 activates transcription of C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) and growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible protein 34 (GADD34). ATF6 is a type II endoplasmic reticulum transmembrane protein with an N-terminal cytoplasmic b-ZIP domain [22]. ERS triggers ATF6 translocation to the Golgi apparatus, where site-1 protease (S1P) and site-2 protease (S2P) cleave ATF6 to release its cytoplasmic domain [23]. Consequently, the 50-kDa N-terminal fragment, termed ATF6(N), translocates to the nucleus to act as a transcription factor [22]. Mild ERS activates adaptive responses that restore endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis, promoting cell survival. In contrast, prolonged or severe ERS triggers apoptotic pathways [24,25].

Accumulating evidence suggests that ERS plays a key role in cancer development, and selective activation of ERS/UPR pathways represents a promising therapeutic strategy [[26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]]. Our previous studies demonstrated that the selective EIF2AK3/PERK activator CCT020312 suppresses TNBC and prostate cancer [32]; additionally, the PI3K inhibitor VPS34-IN1 promoted apoptosis in ER+ BC cells by activating the PERK/ATF4/CHOP pathway. These findings support selective ERS induction as a therapeutic strategy for BC [33]. ERα is the primary therapeutic target in ER+ BC. Emerging evidence indicates crosstalk between ERα signaling and ERS/UPR in ER+ BC [34,35]. However, the regulatory mechanisms of ERα signaling under ERS in ER+ BC are not fully elucidated.

This study aimed to identify the mechanisms underlying ERS-mediated suppression of ERα expression in ER+ BC. We demonstrated that activation of PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 signaling pathway mediates the suppression of ERα expression and signaling in ER+ BC cells. Mechanistically, ATF4 directly bound to the ESR1 (the gene encoding ERα) promoter and suppressed its transcriptional activity, thereby inhibiting ERα signaling. Our study provides insights into the treatment of ER+ BC by targeting ERα signaling through selective activation of the PERK branch of the UPR.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Thapsigargin (TG, CAS# 67526-95-8), brefeldin A (BFA, CAS# 20350-15-6), GSK2656157 (CAS# 1337532-29-2), cycloheximide (CHX, CAS# 66-81-9), actinomycin D (ActD, CAS# 50-76-0), and CCT020312 (CAS# 324759-76-4) were purchased from MedChemExpress (Shanghai, China). Antibodies against BiP (Cat# 3177), PERK (Cat# 5683), p-eIF2α (Cat# 3398), eIF2α (Cat# 5324), ATF4 (Cat# 11815), CHOP (Cat# 2895), ATF6 (Cat# 65880), IRE1α (Cat# 3294), XBP1s (Cat# 12782), and ERα (Cat# 8644) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). β-Actin antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and Ki-67 antibody (Cat# AF0198) was obtained from Affinity Biosciences (Zhenjiang, China). Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) was purchased from Bimake (Houston, TX, USA). RIPA lysis buffer, BCA protein assay kit, and dual-luciferase reporter assay kit were obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). PrimeScriptTM RT reagent kit with gDNA eraser (Cat# RR047A) and TB green® Premix Ex TaqTM II (Tli RNaseH Plus) (Cat# RR820A) for RT-qPCR were purchased from Takara (Otsu, Japan). SimpleChIP® Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Cat# 9003) and SimpleChIP® Universal qPCR Master Mix (Cat# 88989) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). PERK siRNA, ATF4 siRNA, CHOP siRNA, ATF6 siRNA, and IRE1α siRNA were purchased from Sangon Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). ATF4-overexpressing lentivirus (LV5-ATF4), negative control lentivirus (LV5-GFP), GV238-Basic, GV238-2000, GV238-1300, GV238-600, GV657-Basic, GV657-ATF4, and GV657-ERα were purchased from GENE (Shanghai, China). NSG mice (4-6 weeks old, weight 18-22 g) were obtained from Shanghai Model Organisms Center, Inc. (Beijing, China). Matrigel was purchased from Corning (Corning, NY, USA).

Cell culture

The human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 (RRID:CVCL_3397) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). T47D (RRID:CVCL_0I95) was obtained from Shanghai Zhong Qiao Xin Zhou Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Cell lines were authenticated by STR profiling, and all experiments were performed with cells within 15 passages. Cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 1% antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C. All experiments were performed with mycoplasma-free cells.

Cell transfection and transduction

Cells were transfected with siRNA or plasmids using Lipo8000TM (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and Opti-MEM I (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) low-serum medium for 6–12 h. The medium was then replaced with normal growth medium, and cells were subjected to further treatment as described in the experimental design.

For lentivirus transduction, cells at 50% confluence were transduced with ATF4-overexpressing lentivirus (LV5-ATF4) or control lentivirus (LV5-GFP) according to the manufacturer's protocol and as previously described [30]. The medium was refreshed with regular growth medium for 72 h, after which cells were processed for subsequent analyses.

Western blotting analysis

Cells were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Protein concentrations were quantified using the BCA Protein Assay Kit. Western blotting was performed as previously described [30]. Briefly, 30 μg of protein was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) after methanol activation. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBST (10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.4) or 5% BSA for 2 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with primary antibodies (1:1000 dilution, unless otherwise indicated) overnight at 4°C. After three washes with TBST, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using ECL substrate and imaged with a chemiluminescence detection system (Tanon, Shanghai, China).

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using RNAiso Plus, followed by cDNA synthesis with the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Takara). RT-qPCR was performed as described previously [30]. Primer sequences for RT-qPCR are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Cell viability assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates (3 × 104/mL) and were treated as indicated. Subsequently, 10 μL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well, and plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a multimode microplate reader (Varioskan LUX, Thermo Scientific).. Cell viability was normalized to the control group and expressed as a percentage.

Real-Time Cell Analysis Using xCELLigence

The xCELLigence real-time cell analysis system (ACEA Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to monitor cellular behavior by measuring impedance changes. MCF-7 (1 × 10⁴ cells/well) and T47D cells (1 × 10⁴ cells/well) were seeded in E-plates, followed by treatment with 12 μM CCT020312 or transfected with an ATF4-overexpressing plasmid. Data are presented as time-dependent curves showing the mean Cell Index (CI) ± standard deviation (SD). The x-axis represents the timeline (hours), and the y-axis represents the normalized CI reflecting cell proliferation.

Double luciferase reporter assay

MCF-7 and T47D cells were seeded in 24-well plates (5 × 104 cells/well) and transfected with 1 μL of Lipo8000TM (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), and 0.5 μg of reporter plasmids of GV238-Basic, GV238-2000, GV238-1300, GV238-600, GV657-ATF4 and CV045-TK Promoter-Renilla Luciferase in 25 μL of Opti-MEM. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were treated with 1 μM TG or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 24 h and harvested for luciferase reporter assay, which was performed with a Dual Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay Kit (RG027, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Relative luciferase activity (Firefly/Renilla luminescence ratio) was calculated and expressed as mean ± SD.

ChIP‒qPCR

The ChIP assay was conducted using a SimpleChIP® Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Magnetic Beads) (Cat# 9003S; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions and as previously described [30]. Briefly, MCF-7 and T47D cells (3 × 106/mL) were seeded in 10-cm dishes and treated the following day with 1 μM TG for 24 h. Cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde at 25°C for 10 min. Then, 0.125 M glycine was added to stop the reaction. Cells were lysed on ice and ultrasonically treated to obtain the genomic DNA fragments. Subsequently, the fragments were immunoprecipitated with anti-ATF4, anti-H3, and anti-IgG antibodies (CST, Danvers, MA, USA). DNA was amplified using PCR with SimpleChIP® Universal qPCR Master Mix (Cat# 88989s; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.). PCR was performed under the following reaction conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, and annealing and extension at 60°C for 60 s (40 cycles). The PCR products were identified using 2.0% agarose gel electrophoresis. The primers used for ChIP-qPCR are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Tissue microarray and Immunofluorescence staining

A commercially available breast cancer (BC) tissue microarray comprising 75 ER+ BC cases was obtained from Shanghai Outdo Biotech Company (Shanghai, China). Tissues were fixed in neutral-buffered formalin and embedded as adjacent 1-mm cores on the microarray. The ER+ BC tissue microarray was incubated with a specific primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. Sections were then incubated for 1 h with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Nuclei were counterstained with 0.1 μg/mL DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich). Fluorescence images were acquired using a Pannoramic MIDI scanner (3DHISTECH Ltd.) and quantified with CaseViewer software.The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Outdo Biotech Company (Ethics Approval No. YB M-05-01). For the detail information on tissue microarray, please see the supplementary file entitled Tissue Microarray.

Xenograft mouse model

The animal experiments were performed in accordance with the National Guidelines for Animal Care and Use and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Chongqing Medical University (IACUC protocol number: 2022124). A subcutaneous xenograft model was established in NSG mice, which were housed in a SPF facility with a 12 h artificial light–dark cycle at Chongqing Medical University, by inoculating MCF-7 cells (2 × 106 cells/100 μL per NSG mouse) stably expressing LV5-GFP or LV5-ATF4 (GENE, Shanghai, China) mixed with Matrigel (1:1). When tumors grew to ∼40–50 mm3, tumor growth in the mice was measured every 3 days. The tumor volume (V) was measured using a slide caliper and calculated using the following formula: V (mm3) = 0.5 × ab2, where a and b represent the long diameter and perpendicular short diameter (mm) of the tumor, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Unpaired two-tailed Student's t test was used for comparisons between two groups. Multiple group comparisons were assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. All experiments were independently repeated at least three times. The correlation between ERα and ATF4 expression in the tissue microarray was assessed by Pearson's correlation coefficient.

Results

ERS suppresses ERα expression in ER+ BC cells

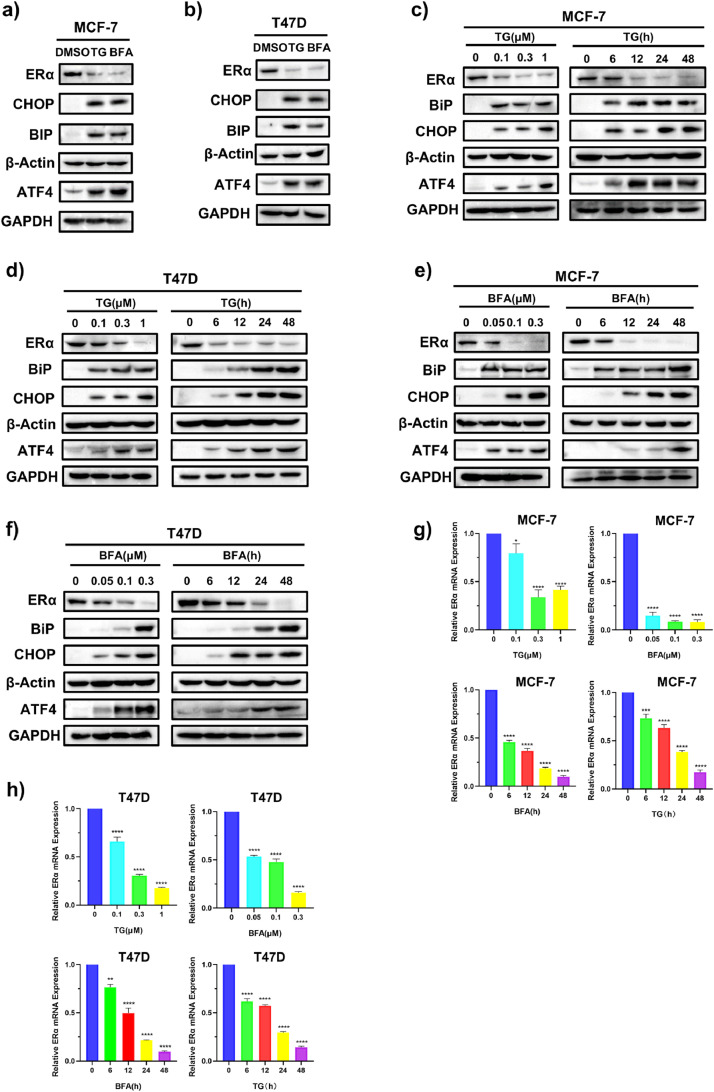

To explore the effects of ERS on ERα expression, ER+ BC cell lines MCF-7 and T47D were treated with two different ERS inducers thapsigargin (TG) and brefeldin A (BFA). Western blotting results showed that the levels of the ERS markers (BiP, CHOP and ATF4) were markedly increased by TG or BFA (Fig. 1a, b, and Supplementary Fig. S1a, b), while ERα levels were downregulated by TG and BFA in dose- and time- dependent manners in both MCF-7 (Fig. 1c, e) and T47D (Fig. 1d, f) cell lines. We also examined the effects of TG and BFA on ERα mRNA levels. RT-qPCR results showed that TG and BFA reduced ERα mRNA levels in dose- and time- dependent manners (Fig. 1g, h), suggesting that ERS suppresses ERα expression at both protein and mRNA levels. Serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 3 (SGK3) and growth regulation by estrogen in breast cancer 1 (GREB1) are two well-known ERα target genes and play import roles in ERα signaling [36,37]. RT-qPCR results showed that TG and BFA also decreased mRNA levels of SGK3 and GREB1 (Supplemental Fig.S1 c), which support that ERS suppresses ERα signaling. Given that ERα signaling is critical for ER+ BC cell growth, we examined the effects of TG and BFA on the cell viability of MCF-7 and T47D cells. As shown in Supplementary Fig.S1d-g, TG and BFA dose-dependently reduced cell viability in both cell lines.

Fig. 1.

ERS inducers decrease ERα protein and mRNA levels in ER+ BC cell lines. (a, b) After exposure to 1 μM TG or 0.3 μM BFA for 24 h, MCF-7 (a) and T47D cells (b) were harvested for western blotting. (c, d) MCF-7 (c) and T47D (d) cells were treated with different concentrations of TG for 24 h or with 1 μM TG for the indicated time, and then cells were collected for western blotting. (e, f) MCF-7 (e) and T47D (f) cells were treated with different concentrations of BFA for 24 h or with 0.3 μM BFA for the indicated time, and then cells were collected for western blotting. (g, h) MCF-7 (g) and T47D (h) cells were treated with different concentrations of TG or BFA for 24 h or 1 μM TG or 0.3 μM BFA for the indicated time. Then, cells were collected for quantitative RT-PCR assay. The relative expression of ERα mRNA was normalized to that of β-Actin and presented as the mean ± SD (n = 4). Student's t test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, or ****p < 0.0001 vs. control. TG, thapsigargin; BFA, brefeldin A.

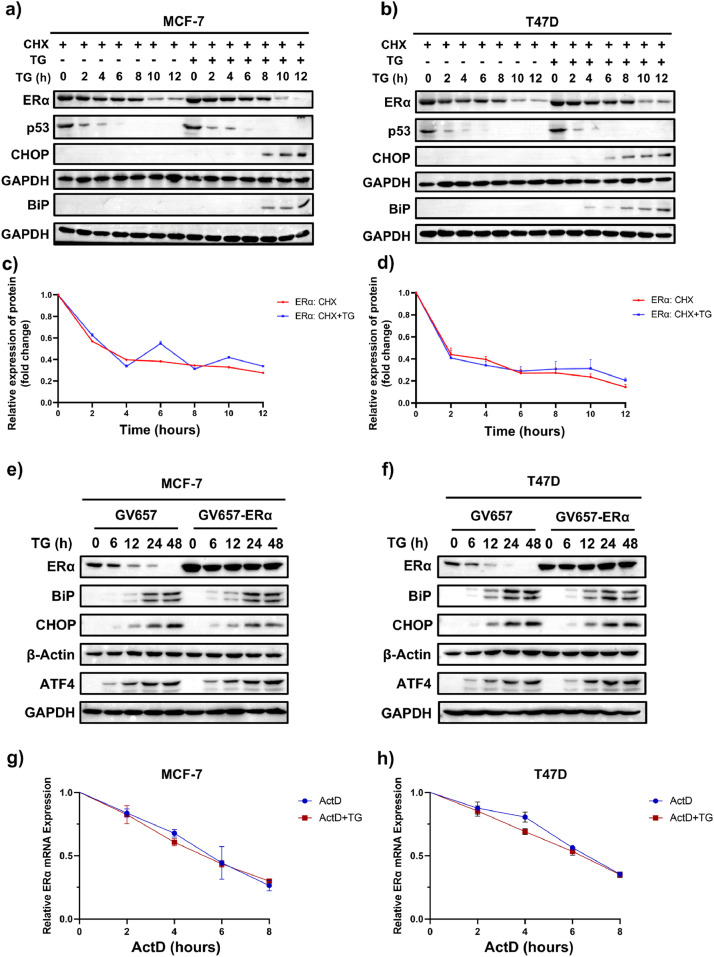

ERS decreases ERα expression at the transcriptional level

To investigate the mechanism underlying ERS-mediated suppression of ERα expression was explored, we first examined whether ERS accelerated the degradation of ERα protein. We applied the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) to investigate whether ERS reduced ERα protein stability. In MCF-7 and T47D cells, ERα protein levels decreased following CHX treatment, and no appreciable change was found in ERα degradation rate in the presence of TG compared to vehicle control (Fig. 2a-d). Additionally, endogenous ERα protein expression, but not exogenously overexpressed ERα protein, progressively dropped following TG intervention in ER+ breast cancer cell lines. (Fig. 2e, f). These findings suggested that TG did not affect ERα protein stability or facilitate its degradation. The transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D (ActD) was then used to assess the impact of ERS on the stability of ERα mRNA. The results demonstrated that TG had no impact on the degradation rate of ERα mRNA in MCF-7 and T47D cells (Fig. 2g, h). Together with the results that ERS inducers reduced ERα mRNA levels (Fig. 1g, h), these findings indicate that ERS inhibits ERα expression by decreasing its mRNA production rather than by enhancing mRNA degradation.

Fig. 2.

ERS downregulates ERα expression at the transcriptional level in ER+ BC cells. (a, b) MCF-7 (a) and T47D (b) cells were pretreated with 100 μg/mL CHX for 1 h and then treated with or without 1 μM TG for the indicated times. After TG treatment, cells were collected for western blotting. p53 is a short live protein served as a control for CHX treatment. (c, d) Quantification of ERα protein normalized to GAPDH in MCF-7 (c) and T47D (d) cells (n=3). (e, f) MCF-7 (e) and T47D (f) cells were transfected with empty vector (GV657) or ERα overexpression vector (GV657-ERα) and then treated with or without TG for the indicated times. Cells were collected for western blotting. (g, h) MCF-7 (g) and T47D (h) cells were pretreated with 1 μg/mL ActD for 0.5 h and then treated with or without 1 μM TG for the indicated time. Then, cells were collected for quantitative RT-PCR assay (n = 4). All data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance determined by Student's t test. The abbreviations TG, BFA, CHX, and ActD stand for thapsigargin, brefeldin A, cycloheximide, and actinomycin D, respectively.

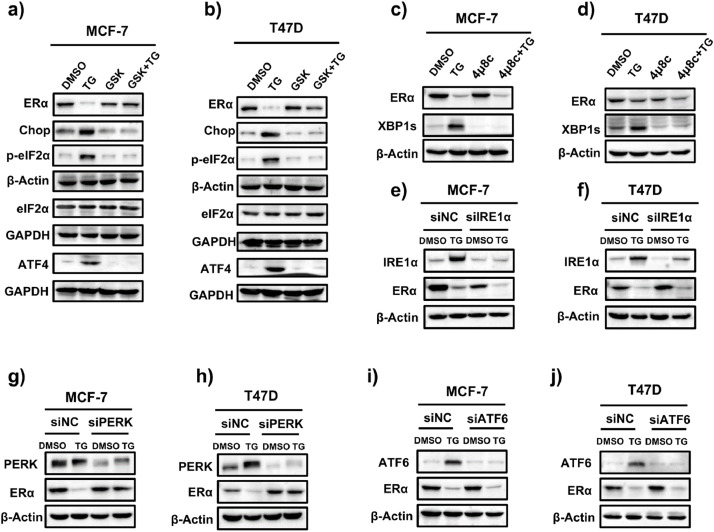

ERS suppresses ERα expression via the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 pathway

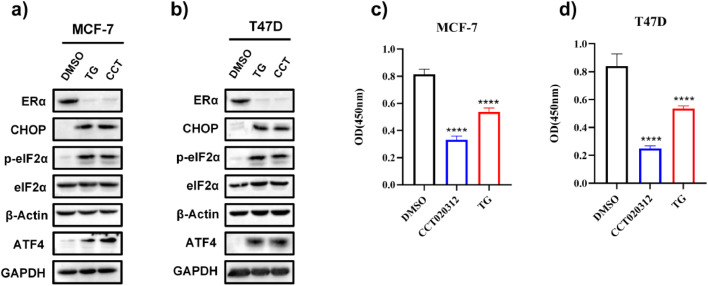

PERK, ATF6, and IRE1α are the three main sensors that become active under ERS. We initially used commercially available IRE1α and PERK inhibitors and studied their effects on ERS-induced ERα downregulation to determine which signaling pathway is responsible. In MCF-7 and T47D cells, TG increased the levels of PERK downstream targets p-eIF2α, ATF4, and CHOP, whereas the PERK inhibitor GSK2656157 blocked the TG-induced elevation in p-eIF2α, ATF4, and CHOP levels (Fig. 3a, b), confirming that GSK2656157 is a PERK inhibitor and can block TG-induced PERK activation. XBP1, a key downstream target of IRE1α, is spliced into its active form (XBP1s) upon IRE1α activation. TG significantly elevated XBP1s levels, and the IRE1α inhibitor 4μ8C blocked the TG-induced increase in XBP1s levels (Fig. 3c, d), confirming that 4μ8C suppresses IRE1α activity. Surprisingly, GSK2656157, but not 4μ8C, successfully hindered TG-induced ERα reduction (Fig. 3a-d), indicating that the PERK pathway mediates ERS-induced ERα downregulation. Furthermore, PERK knockdown, but not IRE1α or ATF6 knockdown, reversed the TG-induced ERα reduction (Fig. 3e-j). These findings support that the PERK pathway, rather than the IRE1α or ATF6 pathways, was involved in the ERS-induced ERα reduction. To further confirm that activating the PERK pathway reduced ERα expression, ER+ BC cells were treated with the selective EIF2AK3/PERK activator CCT020312. As expected, CCT020312 treatment increased p-eIF2α, ATF4, and CHOP levels (Fig. 4a, b) and significantly reduced ERα expression in both cell lines (Fig. 4a, b). Furthermore, CCT020312 treatment reduced the cell viability of MCF-7 and T47D (Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 3.

ERS inhibits ERα expression through the PERK signaling in ER+ BC cell lines. (a, b) MCF-7 (a) and T47D (b) cells were pretreated with 1 μM GSK2656157 (GSK) for 1 h, followed by treatment with or without 1 μM TG for 24 h. Cells were then harvested for western blotting. (c, d) MCF-7 (c) and T47D (d) cells were pretreated with 25 μM 4μ8C for 1 h, followed by treatment with or without 1 μM TG for 24 h. Then cells were collected for western blotting. (e, f) MCF-7 (e) and T47D (f) cells were transfected with control siRNA (siNC) or IRE1α siRNA (siIRE1α) for 24 h, followed by treatment with or without TG for 24 h. Cells were collected for western blotting. (g, h) MCF-7 (g) and T47D (h) cells were transfected with siNC or PERK siRNA (siPERK) for 24 h, followed by treatment with or without TG for 24 h. Cells were collected for western blotting. (i, j) MCF-7 (i) and T47D (j) cells were transfected with siNC or ATF6 siRNA (siATF6) for 24 h, followed by treatment with or without TG for 24 h. Cells were collected for western blotting.

Fig. 4.

The selective EIF2AK3/PERK activator CCT020312 decreases ERα expression and cell viability in ER+ BC cell lines. (a, b) MCF-7 (a) and T47D (b) cells were treated with 14 μM CCT020312 or 1 μM TG for 24 h. Then cells were collected for western blotting. (c, d) MCF-7 (c) and T47D (d) cells were treated with 14 μM CCT020312 or 1 μM TG for 24 h. CCK-8 assay was used to analyse the cell viability (n = 6). One-way ANOVA analysis, ****p < 0.0001 vs. control.

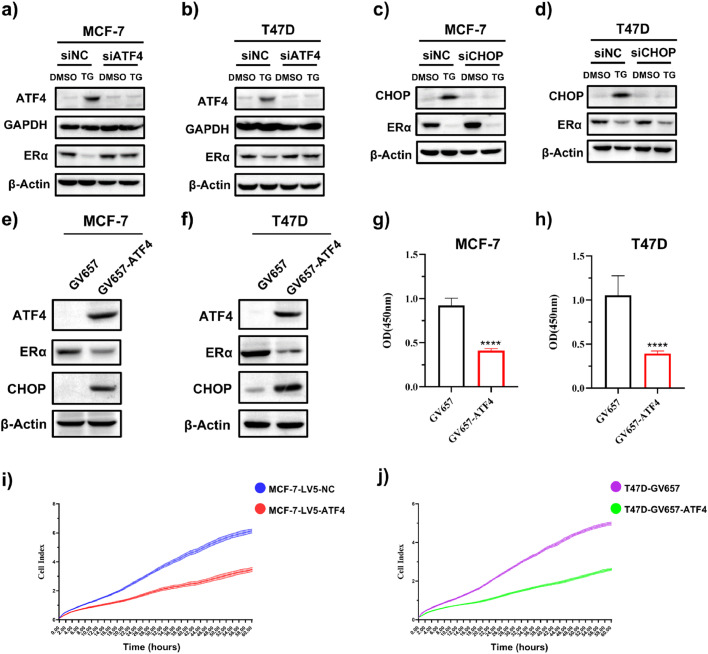

We then studied whether ATF4 and CHOP, which are major transcription factors downstream of the PERK signaling pathway, are involved in regulating ERα expression. MCF-7 and T47D cells were transfected with ATF4- or CHOP-targeting siRNAs to suppress their expression, followed by treatment with TG for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 5a, b, ATF4 knockdown hindered TG-mediated ATF4 upregulation and attenuated TG-induced ERα downregulation. In contrast, CHOP knockdown blocked TG-mediated CHOP elevation but did not reverse ERα downregulation (Fig. 5c, d). These results suggested that the ERS-induced reduction in ERα expression was mediated by ATF4. To further validate ATF4’s role in ERα regulation, we overexpressed ATF4 in MCF-7 and T47D cells. The results demonstrated that expression of CHOP, downstream of ATF4, was upregulated, while ERα levels were significantly decreased in cells transfected with the ATF4 overexpression vector (Fig. 5e, f). Consistent with ERα suppression, ATF4 overexpression markedly decreased the levels of ERα downstream targets SGK3 and GREB1 and cell viability (Fig. 5g–j, and Supplemental data Fig.S2).

Fig. 5.

ERS decreases ERα expression through ATF4 in ER+ BC cell lines. (a, b) MCF-7 (a) and T47D (b) cells were transfected with control siRNA (siNC) or ATF4 siRNA (siATF4) for 24 h, followed by treatment with or without TG for 24 h. Cells were harvested for western blotting. (c, d) MCF-7 (c) and T47D (d) cells were transfected with siNC or CHOP siRNA (siCHOP) for 24 h, followed by treatment with or without TG for 24 h. Cells were harvested for western blotting. (e-h) MCF-7 and T47D cells were transfected with empty control plasmid GV657 or ATF4 overexpression plasmid (GV657-ATF4). Cells were harvested for western blotting (e, f) or subjected to CCK-8 assays (n = 6) (g, h). Student's t test, ****p < 0.0001 vs. GV657 control. (i) MCF-7 cells were transduced with control lentivirus (LV5-GFP) or ATF4-expressing lentivirus (LV5-ATF4), and (j) T47D cells were transfected with empty vector control GV657 or GV657-ATF4. Cell proliferation was detected using xCELLigence real-time cell analysis (n = 3).

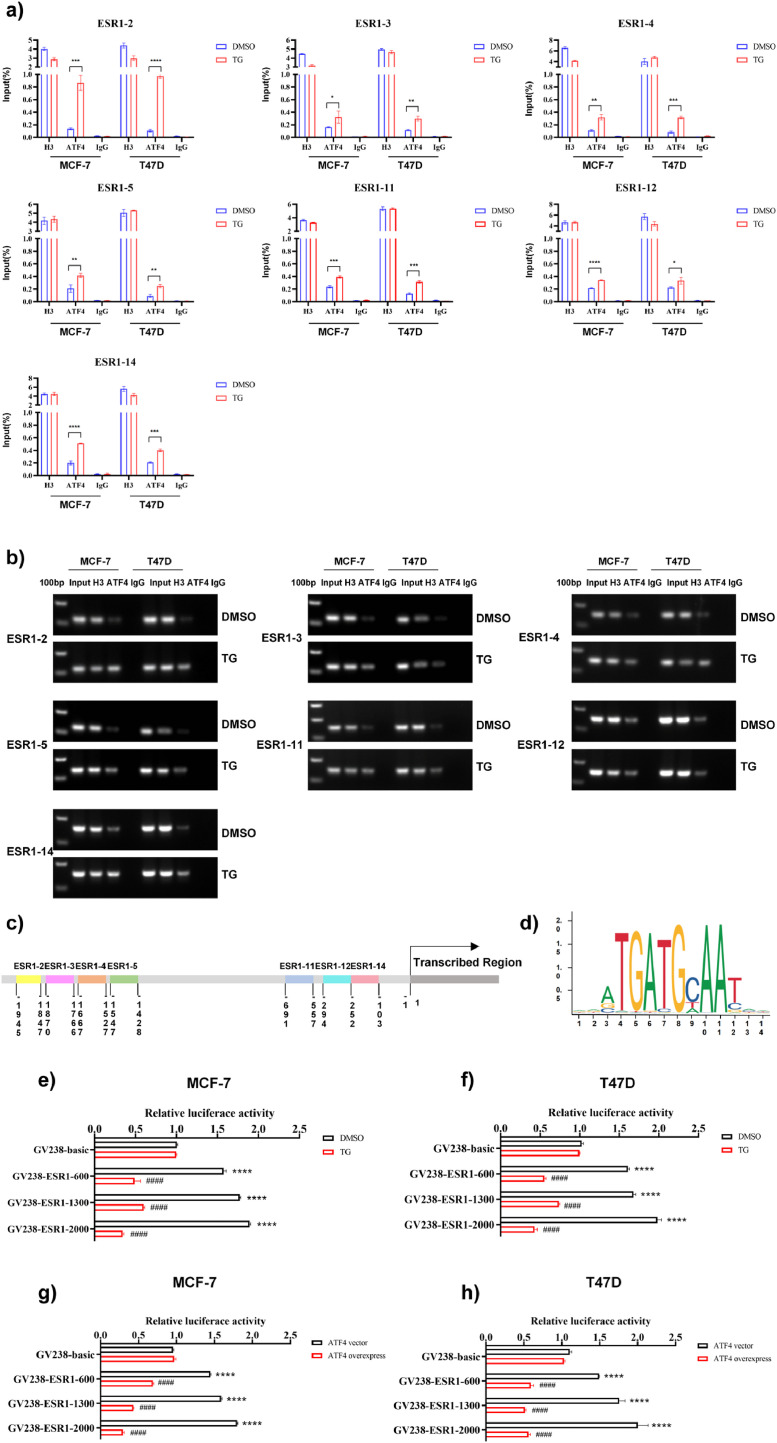

ERS boosts the binding of ATF4 to the ESR1 promoter and suppresses ESR1 promoter activity in ER+ BC cells

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR was carried out to further examine the molecular processes underlying the regulation of ESR1 gene expression by ERS. After immunoprecipitation with anti-ATF4, chromatin DNA from MCF-7 and T47D cells was extracted and purified. Using 14 primer pairs within the ESR1 promoter region, the enriched DNA was determined using real-time PCR, and also sequenced. The outcomes demonstrated that the PCR products (primers ESR1-2: 1945–1847 nt, ESR1-3: 1870–1766 nt, ESR1-4: 1667–1527 nt, ESR1-5: 1547–1428 nt, ESR1-11: 1969–557 nt, primer ESR1-12: 294–154 nt, and primer ESR1-14: 252–103 nt) were identified in the ATF4 immunoprecipitated group (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Fig. 3a). Additionally, the agarose gel electrophoresis assay results suggested that TG increased the binding of the ATF4 protein to these seven ESR1 promoter regions (Fig. 6b, Supplementary Fig. 3b). Furthermore, the results of the promoter and transcription factor-binding site prediction analysis (http://jaspar.genereg.net/analysis) revealed the presence of ATF4 binding sites in the ESR1 promoter region with a relative profile score threshold of >75% (Fig. 6d). These findings suggested that ATF4 may bind to the ESR1 promoter region. We employed luciferase assays to confirm that ATF4 binds to the ESR1 promoter. Different reporters were transfected into MCF-7 and T47D cells and then treated with or without TG. The results revealed that in the absence of TG, the luciferase activities of the reporters GV238-ESR1-2000 (−2000 to 0 nt), GV238-ESR1-1300 (−1300 to 0 nt), and GV238-ESR1-600 (−600 to 0 nt) were significantly higher (p < 0.01) than those of GV238-Basic (Fig. 6e, f), supporting the notion that these regions contained the ESR1 promoter and/or cis-regulatory elements. TG treatment suppressed luciferase activity of these constructs (Fig. 6e, f), further indicating that the –1945 to –1428 nt and –691 to –103 nt regions contain ERS-responsive cis-elements. Similar results were observed when ATF4 overexpression plasmids and ESR1 luciferase reporter plasmids were co-transfected into MCF-7 and T47D cells (Fig. 6g, h). The aforementioned findings demonstrated that ATF4 could bind to the ESR1 promoter region from −1945 to −1428 nt and from −691 to −103 nt, and both ERS and ATF4 overexpression could suppress ESR1 promoter activity.

Fig. 6.

ATF4 binds to the ESR1 promoter region and suppresses ESR1 promoter activity. (a) The ChIP-qPCR assay was conducted with ATF4 antibody in MCF-7 and T47D cells that were treated with or without 1 μM TG for 24 h. DNA enrichment was quantified by qPCR with standard curves generated from serially diluted input DNA and expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Student's t test, ns p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, or ****p < 0.0001 vs. control. (b) ChIP-qPCR products were visualized by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose-gel. (c) Schematic diagram of the ESR1 promoter region showing ATF4 binding sites. (d) The potential binding sites of ATF4 on the ESR1 promoter were predicted by JASPAR. (e, f) MCF-7 (e) and T47D cells (f) were transfected with ESR1 luciferase reporter plasmids or control plasmid GV238-Basic and then treated with 1 μM TG. Luciferase activities were measured using a dual-luciferase reporter assay system according to the manufacturer's protocol. The relative luciferase activity was calculated and expressed as the mean ± SD. Student's t test, ****p < 0.0001 vs. GV238-Basic (DMSO); ####p < 0.0001 vs. corresponding GV238-ESR1 (n = 3). (g, h) ESR1 luciferase reporter plasmids and ATF4 overexpression plasmids or empty vector control were co-transfected into MCF-7 (g) and T47D cells (h). Luciferase activities were measured and the relative luciferase activity was calculated and expressed as the mean ± SD. Student's t test, ****p < 0.0001 vs. GV238-Basic (DMSO); ####p < 0.0001 vs. corresponding GV238-ESR1 (n = 3). ChIP-qPCR, chromatin immunoprecipitation-quantitative PCR.

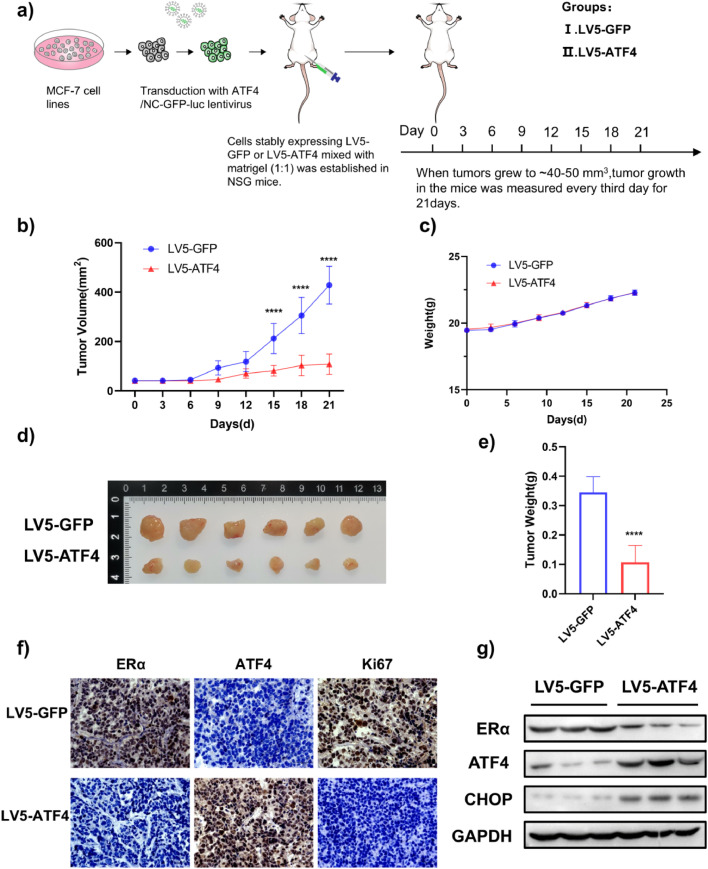

ATF4 overexpression inhibits ERα expression and tumor growth in vivo

We next explored the correlation between ATF4 and ERα in vivo. We assessed ERα and ATF4 mRNA expression levels in clinical samples of breast tumors (n = 1085) from the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) datasets (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/). The results showed that ATF4 mRNA expression levels were lower in invasive breast cancer than in normal breast tissues. Conversely, ERα mRNA expression levels were higher in invasive breast cancer (Fig. S4a, b). Additionally, the correlation between ERα and ATF4 was explored by ER+ BC tissue microarray. As shown in Fig. S3c and d, ERα and ATF4 had a negative correlation (r = −0.4629) in ER+ BC (Fig. S4c, d).

To validate these findings in vivo, MCF-7 cells stably overexpressing ATF4 were orthotopically implanted into NSG mice (Fig. 7a). Compared to control xenograft mice, tumor volumes were lower in mice with ATF4 overexpression (Fig. 7b, d, e). There were no differences in body weights between any of the groups (Fig. 7c). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed significantly lower Ki-67 (proliferation marker) and ERα expression in ATF4-overexpressing tumors compared to controls (Fig. 7f). ATF4 overexpression reduced ERα expression, which was further confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 7g). Taken together, these findings revealed that ATF4 overexpression inhibited ERα expression and tumor cell growth in vivo.

Fig. 7.

ATF4 overexpression inhibits ERα expression and tumor growth in an MCF-7 orthotopic xenograft model. (a) Schematic of the experimental design for the MCF-7 orthotopic xenograft model. (b) Effect of ATF4 overexpression on the growth of MCF-7 xenograft tumors. Tumor volume was measured every 3 days and presented as the mean ± SD. Student's t test, ****p < 0.0001 vs. LV5-GFP, n = 6. (c) Body weight changes in mice during the 21-day study period (n = 6). (d) Representative image of tumors from each group. (e) Tumor weight was measured at the end of the study. Student's t test, ****p < 0.0001 vs. LV5-GFP, n = 6. (f) Immunohistochemical staining of Ki-67 and ERα in tumor sections. Scale bar: 50 μm. (g) Representative tumor tissues from each group were prepared and subjected to western blot analysis.

Discussion

BC is the most prevalent, most commonly diagnosed, and leading cause of cancer-related death in women [1]. The most effective target for endocrine therapy is the ERα, which is expressed in the majority of BC cases [38,39]. ERα is responsible for initiating a network of signaling pathways that drive breast tissue differentiation and proliferation [6,40]. ER+ BC patients normally receive endocrine therapy. Endocrine therapy suppresses ER+ BC progression through two primary mechanisms: 1) blocking estrogen binding to ERα or promoting its degradation, mediated by selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs, e.g., tamoxifen) and selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs, e.g., fulvestrant); 2) reducing estrogen levels via aromatase inhibitors (AIs), which inhibit peripheral estradiol synthesis in postmenopausal women [[41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46]]. Endocrine therapies significantly improve the prognosis of ER+ BC patients by targeting ERα signaling. However, de novo or acquired resistance to endocrine therapy remains a major clinical challenge [47]. ESR1-mutant breast cancer poses significant therapeutic challenges, as ERα mutations driving constitutive transcriptional activity and reduced anti-estrogen sensitivity are key contributors to endocrine resistance [48]. Molecular dynamics simulations of ERα ligand-binding domain (LBD) mutations (e.g., Y537S and D538G) revealed that these mutations induce conformational changes in ERα structure. These mutations enhance hydrogen bonding within the LBD, stabilizing the agonist-bound conformation of ERα [49]. Therefore, developing new classes of pharmacological inhibitors to target mutant ERα is imperative. We propose that transcriptional suppression of ESR1 may overcome resistance driven by ERα mutations.

As a transcription factor, ERα drives the expression of genes involved in tumor proliferation and growth, while its own expression is tightly controlled by upstream transcriptional regulators. For example, Twist Family BHLH Transcription Factor 1 (TWIST), a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor and a mesenchymal marker, has been shown to bind to the ESR1 promoter and suppress ERα transcription [50]. FOXC1 competes with GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA3) for the same binding regions in the cis-regulatory elements upstream of the ESR1 and thereby downregulates ERα expression and consequently reduces its transcriptional activity [51].

ATF4, a member of the cAMP-responsive element-binding protein family of basic zipper-containing proteins [52,53], is a transcription factor that regulates the cellular response to stress including UPR activated by ERS, the cellular response to low oxygen levels, and the amino acid response (AAR) activated by amino acid deprivation [54,55]. ERS, amino acid limitation, hypoxia, and oxidative stress all activate ATF4 via both p-eIF2α-dependent and p-eIF2α-independent mechanisms [54]. ATF4 controls genes involved in amino acid transport and metabolism, protection against oxidative stress, and protein homeostasis [56]. However, ATF4 can also induce apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and senescence [55,57]. During ERS, ATF4 activation hinges on the PERK-eIF2α axis, which subsequently prompts ATF4 to induce the expression of CHOP and several other related proteins involved in autophagy, antioxidant defense, and cell death pathways [58,59].

Wang et al. previously reported that upregulation of SGK3 is essential for preventing extensive ERS by maintaining endoplasmic reticulum calcium pump (SERCA2b) function during acquiring aromatase inhibitor resistance, thus sustaining ERα signaling by preventing overactivation of the PERK arm [37]. Our previous studies demonstrated that the selective EIF2AK3/PERK activator CCT020312 inhibited the development of triple-negative breast and prostate cancers [32]. Additionally, the PI3K-targeting inhibitor VPS34-IN1 promoted apoptosis in ER-positive breast cancer cells by activating the PERK/ATF4/CHOP signaling pathway, suggesting that modulating ERS may be a potential strategy for the treatment of breast cancer [33]. However, the effect of ERS on ERα expression remains not fully elucidated. Given that ERα is still a critical player in ER+ breast cancer including endocrine-resistant ER+ BC [60,61], we proposed a therapeutic strategy to reduce ERα expression transcriptionally by leveraging the UPR-mediated suppression of protein synthesis. Our findings demonstrated that ERα mRNA and protein levels in ER+ breast cancer cell lines were significantly reduced following treatment with ERS inducers (TG and BFA). Furthermore, we identified that ERS inhibits ERα transcription via the PERK branch and thus reduces ERα expression.

Our results demonstrate that the ERS-induced ERα reduction is mediated by the PERK pathway rather than the IRE1 and ATF6 pathways. Further mechanistic studies showed that TG and ATF4 overexpression suppressed ESR1 promoter activity and that ATF4 could bind to the ESR1 promoter region from -1945 to -1428 nt and from -691 to -103 nt. Then, we examined the expression of ERα and the inhibitory effects on tumor growth in vivo, using lentivirus-mediated delivery of ATF4 in an orthotopic xenograft model. Our results demonstrated that ATF4 overexpression in an MCF-7 xenograft model significantly inhibited tumor growth and reduced ERα protein levels. The in vivo results were consistent with the findings from in vitro studies. Therefore, we conclude that the reduction in ERα expression induced by ERS is mediated by the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 pathway (Fig. 8). In our previous study, we revealed that VPS34-IN1 can activate the PERK pathway [33]. Consistent with our current findings, VPS34-IN1 downregulated ERα expression in ER+ breast cancer cells, likely via activation of the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 signaling pathway. Our results identify ATF4 as a novel transcription factor regulating ERα expression in BC. While ATF4 typically functions as a transcriptional activator, it has also been reported that ATF4 suppresses the expression of some genes which contain documented ATF4 binding sites near the transcriptional start sites [62]. In this study, we found that ATF4 bound to ESR1 promoter region and suppressed its transcription, although the detailed suppressing mechanism still needs to be revealed. According to previous studies [[63], [64], [65], [66]], a single transcription factor can exhibit dual regulatory functions—both activating and repressing gene expression—depending on contextual determinants including (1) specific DNA binding motifs, (2) interacting co-regulatory partners, (3) cellular microenvironmental conditions, and (4) chromatin architecture of target promoters. MAX, for example, functions as a transcriptional repressor when forming heterodimers with MNT/MXD1, yet functions as an activator upon dimerization with MYC [67]. Given our previous discovery that ERS downregulates androgen receptor (AR) expression via PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 signaling in luminar AR TNBC and prostate cancer, we consider that ATF4 might share the similar transcriptional regulatory mechanism on ESR1 under ERS conditions in ER+ BC.

Fig. 8.

Proposed mechanism of ERS-mediated suppression of ERα expression. ERS activates the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 signaling pathway, leading to ATF4 binding at the ESR1 promoter and repression of its transcriptional activity, thereby suppressing ESR1 expression.

Emerging evidence suggests crosstalk between the ERS/UPR and ERα signaling. Andruska et al. have reported that estrogen activated anticipatory UPR to prepare for proliferation [34], whereas Fan & Jordan demonstrated that estrogen hyperactivates ERα to induce apoptosis through the PERK branch of UPR in endocrine-resistant BC [35]. These studies suggest that estrogen/ERα can activate UPR/ERS and lead to divergent biological effects (e.g. proliferation and apoptosis) dependent on cellular context (hormone-responsive or endocrine-resistant BC cells). In the current study, we found that ERS downregulated ERα expression through the PERK branch of UPR, and selective activation of PERK branch by small-molecule compound CCT020312 resulted in reduced ERα expression and suppressed cell viability in ER+ BC cells. Our study provides new insights into the crosstalk between ERS/UPR and ERα signaling.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our investigation demonstrates that ESR1 is a novel ERS response gene and that the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 signaling pathway mediates ERS-induced downregulation of ERα expression. Our findings provide mechanistic insights into how ERS suppresses ERα expression and signaling in ER+ BC. Targeting the UPR represents a promising therapeutic strategy for the treatment of ER+ BC.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yuanli Wu: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Gang Wang: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Ruixue Yang: Investigation, Software. Duanfang Zhou: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision. Qingjuan Chen: Writing – review & editing. Qiuya Wu: Investigation. Bo Chen: Supervision, Investigation. Lie Yuan: Investigation. Na Qu: Investigation. Hongmei Wang: Software. Moustapha Hassan: Writing – review & editing. Ying Zhao: Writing – review & editing. Mingpu Liu: Investigation. Zhengze Shen: Funding acquisition. Weiying Zhou: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81874100, 82373901), the Innovation Research Group in Colleges and Universities Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (No. CXQT20012), the CQMU Program for Youth Innovation in Future Medicine (W0067), the Chongqing Natural Science Foundation Innovation and Development Joint Fund (2022NSCQ-LZX0068), and the Chongqing Postdoctoral Science Foundation (CSTB2023NSCQ-BHX0026).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.neo.2025.101165.

Contributor Information

Zhengze Shen, Email: shenpharm@163.com.

Weiying Zhou, Email: wyzhou0118@cqmu.edu.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Kumar N., Gulati H.K., Sharma A., et al. Most recent strategies targeting estrogen receptor alpha for the treatment of breast cancer. Mol. Divers. 2021;25(1):603–624. doi: 10.1007/s11030-020-10133-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grabher BJ. Breast cancer: evaluating tumor estrogen receptor status with molecular imaging to increase response to therapy and improve patient outcomes. J. Nucl. Med. Technol. 2020;48(3):191–201. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.119.239020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossing M., Pedersen C.B., Tvedskov T., et al. Clinical implications of intrinsic molecular subtypes of breast cancer for sentinel node status. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):2259. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81538-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freelander A., Brown L.J., Parker A., et al. Molecular biomarkers for contemporary therapies in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Genes. (Basel) 2021;12(2) doi: 10.3390/genes12020285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engelsman E., Korsten C.B., Persijn J.P., et al. Human breast cancer and estrogen receptor. Arch. Chir. Neerl. 1973;25(4):393–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tecalco-Cruz A.C., Ramírez-Jarquín J.O., Estrogen Cruz-Ramos E. Receptor alpha and its ubiquitination in breast cancer cells. Curr. Drug Targets. 2019;20(6):690–704. doi: 10.2174/1389450119666181015114041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anbalagan M., Rowan BG. Estrogen receptor alpha phosphorylation and its functional impact in human breast cancer. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2015;418 Pt 3:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwarz D.S., Blower MD. The endoplasmic reticulum: structure, function and response to cellular signaling. Cellul. Molec. Life Sci. 2016;73(1):79–94. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2052-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schönthal AH. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: its role in disease and novel prospects for therapy. Scientifica (Cairo) 2012;2012 doi: 10.6064/2012/857516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khaled J., Kopsida M., Lennernäs H., et al. Drug resistance and endoplasmic reticulum stress in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cells. 2022;11(4) doi: 10.3390/cells11040632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckerling A., Ricon-Becker I., Sorski L., et al. Stress and cancer: mechanisms, significance and future directions. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2021;21(12):767–785. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00395-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walczak A., Gradzik K., Kabzinski J., et al. The role of the ER-induced UPR pathway and the efficacy of its inhibitors and inducers in the inhibition of tumor progression. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/5729710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khanna M., Agrawal N., Chandra R., et al. Targeting unfolded protein response: a new horizon for disease control. Expert. Rev. Mol. Med. 2021;23:e1. doi: 10.1017/erm.2021.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ron D., Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev. Molec. Cell Biol. 2007;8(7):519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hetz C., Zhang K., Kaufman RJ. Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Molec Cell Biol. 2020;21(8):421–438. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0250-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schröder M., Kaufman RJ. The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:739–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.So J. Roles of endoplasmic reticulum stress in immune responses. Mol. Cells. 2018;41(8):705–716. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2018.0241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park S., Kang T., So J. Roles of XBP1s in transcriptional regulation of target genes. Biomedicines. 2021;9(7) doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9070791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto K., Suzuki N., Wada T., et al. Human HRD1 promoter carries a functional unfolded protein response element to which XBP1 but not ATF6 directly binds. J. Biochem. 2008;144(4):477–486. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvn091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harding H.P., Zhang Y., Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature. 1999;397(6716):271–274. doi: 10.1038/16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Todd D.J., Lee A., Glimcher LH. The endoplasmic reticulum stress response in immunity and autoimmunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8(9):663–674. doi: 10.1038/nri2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haze K., Yoshida H., Yanagi H., et al. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10(11):3787–3799. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okada T., Haze K., Nadanaka S., et al. A serine protease inhibitor prevents endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cleavage but not transport of the membrane-bound transcription factor ATF6. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(33):31024–31032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu J., Kaufman RJ. From acute ER stress to physiological roles of the unfolded protein response. Cell Death. Differ. 2006;13(3):374–384. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madden E., Logue S.E., Healy S.J., et al. The role of the unfolded protein response in cancer progression: from oncogenesis to chemoresistance. Biol. Cell. 2019;111(1):1–17. doi: 10.1111/boc.201800050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen H., Zhong Y., Yin Y., et al. A marine-derived small molecule induces immunogenic cell death against triple-negative breast cancer through ER stress-CHOP pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022;18(7):2898–2913. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.70975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y., Xie X., Liao S., et al. A011, a novel small-molecule ligand of σ(2) receptor, potently suppresses breast cancer progression via endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy. Biomed. PharmacOther. 2022;152 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen X., Cubillos-Ruiz JR. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signals in the tumour and its microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2021;21(2):71–88. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-00312-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X., Zheng J., Chen S., et al. Oleandrin, a cardiac glycoside, induces immunogenic cell death via the PERK/elF2α/ATF4/CHOP pathway in breast cancer. Cell Death. Dis. 2021;12(4):314. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03605-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim S.Y., Hwang S., Choi M.K., et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of the small molecule AMC-04 on apoptosis: roles of the activating transcription factor 4-C/EBP homologous protein-death receptor 5 pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020;332 doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2020.109277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boudreau M.W., Duraki D., Wang L., et al. A small-molecule activator of the unfolded protein response eradicates human breast tumors in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021;13(603) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abf1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X., Zhou D., Cai Y., et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress inhibits AR expression via the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 pathway in luminal androgen receptor triple-negative breast cancer and prostate cancer. NPJ. Breast. Cancer. 2022;8(1):2. doi: 10.1038/s41523-021-00370-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Q., Zhou D., Shen Z., et al. VPS34-IN1 induces apoptosis of ER+ breast cancer cells via activating PERK/ATF4/CHOP pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023;214 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2023.115634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andruska N., Zheng X., Yang X., et al. Anticipatory estrogen activation of the unfolded protein response is linked to cell proliferation and poor survival in estrogen receptor α-positive breast cancer. Oncogene. 2015;34(29):3760–3769. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan P., Jordan VC. PERK, beyond an unfolded protein response sensor in estrogen-induced apoptosis in endocrine-resistant breast cancer. Molec. Cancer Res. 2022;20(2):193–201. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-21-0702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y., Zhou D., Phung S., et al. SGK3 is an estrogen-inducible kinase promoting estrogen-mediated survival of breast cancer cells. Molec. Endocrinol. (Baltimore, Md.) 2011;25(1):72–82. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y., Zhou D., Phung S., et al. SGK3 sustains ERα signaling and drives acquired aromatase inhibitor resistance through maintaining endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. u S. a. 2017;114(8):E1500–E1508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1612991114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gajadeera N., Hanson RN. Review of fluorescent steroidal ligands for the estrogen receptor 1995-2018. Steroids. 2019;144:30–46. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma D., Kumar S., Narasimhan B. Estrogen alpha receptor antagonists for the treatment of breast cancer: a review. Chem. Cent. J. 2018;12(1):107. doi: 10.1186/s13065-018-0472-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Habara M., Shimada M. Estrogen receptor α revised: expression, structure, function, and stability. Bioessays. 2022;44(12) doi: 10.1002/bies.202200148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDonnell D.P., Wardell S.E., Norris JD. Oral selective estrogen receptor downregulators (SERDs), a breakthrough endocrine therapy for breast cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58(12):4883–4887. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herzog S.K., Fuqua SAW. ESR1 mutations and therapeutic resistance in metastatic breast cancer: progress and remaining challenges. Br. J. Cancer. 2022;126(2):174–186. doi: 10.1038/s41416-021-01564-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Droog M., Beelen K., Linn S., et al. Tamoxifen resistance: from bench to bedside. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013;717(1-3):47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garner F., Shomali M., Paquin D., et al. RAD1901: a novel, orally bioavailable selective estrogen receptor degrader that demonstrates antitumor activity in breast cancer xenograft models. Anticancer Drugs. 2015;26(9):948–956. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Downton T., Zhou F., Segara D., et al. Oral selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs) in breast cancer: advances, challenges, and current status. Drug design. Develop. Therapy. 2022;16:2933–2948. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S380925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carausu M., Bidard F., Callens C., et al. ESR1 mutations: a new biomarker in breast cancer. Expert. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2019;19(7):599–611. doi: 10.1080/14737159.2019.1631799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wardell S.E., Nelson E.R., Chao C.A., et al. Evaluation of the pharmacological activities of RAD1901, a selective estrogen receptor degrader. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2015;22(5):713–724. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hou Y., Peng Y., Li Z. Update on prognostic and predictive biomarkers of breast cancer. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2022;39(5):322–332. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2022.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Toy W., Shen Y., Won H., et al. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations in hormone-resistant breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 2013;45(12):1439–1445. doi: 10.1038/ng.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vesuna F., Lisok A., Kimble B., et al. Twist contributes to hormone resistance in breast cancer by downregulating estrogen receptor-α. Oncogene. 2012;31(27):3223–3234. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu-Rice Y., Jin Y., Han B., et al. FOXC1 is involved in erα silencing by counteracting GATA3 binding and is implicated in endocrine resistance. Oncogene. 2016;35(41):5400–5411. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiao Y., Deng Y., Yuan F., et al. An ATF4-ATG5 signaling in hypothalamic POMC neurons regulates obesity. Autophagy. 2017;13(6):1088–1089. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2017.1307488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koyanagi S., Hamdan A.M., Horiguchi M., et al. cAMP-response element (CRE)-mediated transcription by activating transcription factor-4 (ATF4) is essential for circadian expression of the Period2 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(37):32416–32423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.258970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wortel I.M.N., van der Meer L.T., Kilberg M.S., et al. Surviving stress: modulation of ATF4-mediated stress responses in normal and malignant cells. Trends. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017;28(11):794–806. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ishizawa J., Kojima K., Chachad D., et al. ATF4 induction through an atypical integrated stress response to ONC201 triggers p53-independent apoptosis in hematological malignancies. Sci. Signal. 2016;9(415):ra17. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aac4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harding H.P., Zhang Y., Zeng H., et al. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol. Cell. 2003;11(3):619–633. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frank C.L., Ge X., Xie Z., et al. Control of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) persistence by multisite phosphorylation impacts cell cycle progression and neurogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(43):33324–33337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.140699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wei W., Li Y., Wang C., et al. Diterpenoid Vinigrol specifically activates ATF4/DDIT3-mediated PERK arm of unfolded protein response to drive non-apoptotic death of breast cancer cells. Pharmacol. Res. 2022;182 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang C., Santofimia-Castaño P., Liu X., et al. NUPR1 inhibitor ZZW-115 induces ferroptosis in a mitochondria-dependent manner. Cell Death. Discov. 2021;7(1):269. doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00662-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gates L.A., Gu G., Chen Y., et al. Proteomic profiling identifies key coactivators utilized by mutant ERα proteins as potential new therapeutic targets. Oncogene. 2018;37(33):4581–4598. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0284-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jeselsohn R., Buchwalter G., De Angelis C., et al. ESR1 mutations—A mechanism for acquired endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015;12(10):573–583. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mahmood N., Choi J., Wu P.Y., et al. The ISR downstream target ATF4 represses long-term memory in a cell type-specific manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. u S. a. 2024;121(31) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2407472121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lambert S.A., Jolma A., Campitelli L.F., et al. The Human transcription factors. Cell. 2018;175(2):598–599. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levine M., Tjian R. Transcription regulation and animal diversity. Nature. 2003;424(6945):147–151. doi: 10.1038/nature01763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boyer L.A., Lee T.I., Cole M.F., et al. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005;122(6):947–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frietze S., Farnham PJ. Transcription factor effector domains. SubCell Biochem. 2011;52:261–277. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9069-0_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Amati B., Land H. Myc-Max-Mad: a transcription factor network controlling cell cycle progression, differentiation and death. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1994;4(1):102–108. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.