Abstract

To examine the question of strain specificity in oropharyngeal candidiasis associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, oral samples were collected from 1,196 HIV-positive black South Africans visiting three clinics and 249 Candida albicans isolates were selected for DNA fingerprinting with the complex DNA fingerprinting probe Ca3. A total of 66 C. albicans isolates from healthy black South Africans and 46 from healthy white South Africans were also DNA fingerprinted as controls. Using DENDRON software, a cluster analysis was performed and the identified groups were compared to a test set of isolates from the United States in which three genetic groups (I, II, and III) were previously identified by a variety of genetic fingerprinting methods. All of the characterized South African collections (three from HIV-positive black persons, two from healthy black persons, and one from healthy white persons) included group I, II, and III isolates. In addition, all South African collections included a fourth group (group SA) completely absent in the U.S. collection. The proportion of group SA isolates in HIV-positive and healthy black South Africans was 53% in both cases. The proportion in healthy white South Africans was 33%. In a comparison of HIV-positive patients with and without oropharyngeal symptoms of infection, the same proportions of group I, II, III, and SA isolates were obtained, indicating no shift to a particular group on infection. However, by virtue of its predominance as a commensal and in infections, group SA must be considered the most successful in South Africa. Why group SA isolates represent 53 and 33% of colonizing strains in black and white South Africans and are absent in the U.S. collection represents an interesting epidemiological question.

Individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are prone to oropharyngeal yeast infections during disease progression (3, 5, 7, 8, 11, 19). These infections are most probably related to impairment of the immune system (6, 16, 30), but the exact cause is unknown. In specific studies, there have been indications of possible strain and species specificity (4, 25, 27, 29, 33, 34). In addition, it is now well established that antifungal drug-resistant Candida strains often arise in HIV+ patients (9, 10, 22, 32). Recently, it was demonstrated that strains infecting HIV+ patients undergo phenotypic switching on average at higher frequencies and are on average more drug resistant than commensal strains from healthy individuals (32). In that study, it was demonstrated that isolates exhibited these phenotypic changes prior to the first episode of oral thrush, suggesting that changes are already at play in the oropharyngeal region prior to thrush. The combined results therefore suggest that isolates from HIV+ individuals differ on average phenotypically and may differ genotypically from those carried as commensals in healthy individuals.

To test the possibility that genetically distinct strains are associated with oropharyngeal colonization of HIV+ individuals, we collected oral samples from 1,196 HIV+ patients visiting three clinics in South Africa, and performed a genetic analysis of strain relatedness on 249 Candida albicans isolates by using DNA fingerprinting with the complex probe Ca3 (23, 26, 28). A cluster analysis was performed on each of the three collections, and the genetic groups were compared to those obtained in a similar cluster analysis of control isolates from healthy individuals. In addition, the groups identified in these cluster analyses were compared to the three groups of C. albicans isolates (groups I, II, and III) recently distinguished in collections of U.S. isolates by a variety of fingerprinting methods (14, 20). This comparison revealed a new group, or clade, of C. albicans in South Africa (group SA) that (i) is absent in the United States, (ii) accounts for 53% of isolates in HIV+ and healthy black South Africans and 33% of isolates in healthy white South Africans, and (iii) is less closely related to groups I, II, and III than these three groups are to each other. The results, however, reveal no strain specificity for HIV+ oropharyngeal infections. The proportions of group I, II, III, and SA isolates causing oropharyngeal infections were similar to the proportions of these groups in HIV+ individuals exhibiting no signs of infection and were similar to the proportions in healthy black South Africans. The predominance of SA isolates in South Africans, however, suggests that this group is the most successful as a commensal and pathogen in that geographic area.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection and maintenance of isolates.

The isolates from HIV+ patients were collected over a 4-year period from black HIV+ patients attending three government HIV clinics in the Pretoria region, the Pretoria Academic Hospital (P), the Kalafong Hospital (K), and the GaRankuwa Hospital (G). Patients attending these clinics came from a wide geographic area. Control isolates were obtained from healthy black staff working in a semiurban dental hospital, the Medunsa Oral Health Center (GC), as well as individuals working and living in rural areas in Mahonisi (MAH) and Kruger Park (OKP, KP). Isolates were also obtained from healthy white staff members of the University of Pretoria Oral and Dental Hospital (PC) and white patients seeking oral hygiene treatment at the same hospital (UP). Inclusion criteria for healthy controls were absence of any clinical signs or symptoms of oral mucosal infection (erythematous or pseduomembranous candidiasis), no history of current or chronic illness, and no history of routine intake of prescription or other medication. Healthy individuals were questioned about their medical history and weight loss, and a thorough examination was performed of the mouth, head, and neck to exclude individuals with possible infections and swollen lymph nodes. Healthy individuals were not tested for HIV but were assumed HIV−. Samples from HIV+ patients and healthy individuals were obtained by routine swabbing. The dorsal surface of the tongue was chosen as the representative site (2). Swabs were plated on Sabouraud dextrose agar and incubated at 35°C for 4 days. Germ tube formation in 10% serum was tested for all isolates prior to storage in 20% glycerol at−70°C.

DNA fingerprinting.

The complex DNA fingerprinting probe Ca3 (1, 12, 23, 26, 28) was used to assess the genetic relatedness of C. albicans isolates by previously described methods (13, 15, 17, 20, 26). In brief, isolates were plated from storage cultures on yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) plates and a single colony was randomly selected and grown as a streak on YPD agar. Each isolate was from a different test or control individual. DNA was extracted by the method of Scherer and Stevens (24) and digested with EcoRI. Prior to digestion, the DNA concentration was determined with a Sequoia-Turner 45 fluorometer (Barnstead/Thermodyne, Dubuque, Iowa). EcoRI-digested DNA was electrophoresed in a 0.8% agarose gel at 50 V with DNA from the reference strain 3153A in the outer lanes. When the bromophenol blue indicator dye had migrated 16 cm, the DNA was transferred to a Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.) by capillary blotting. Prehybridization was performed as previously described (26) with preboiled salmon sperm DNA. Blots were hybridized overnight with randomly primed 32P-labeled Ca3 probe, washed at 45°C, and autoradiographed on XAR-S film (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, N.Y.) with Cronex Lightning-Plus intensifying screens (Dupont Co., Wilmington, Del.).

Cluster analysis and comparison with U.S. isolates.

Gel images were analyzed with DENDRON software (Solltech Inc., Oakdale, Iowa) by recently described methods (28). Autoradiogram images were scanned with an Astra 1220U flatbed scanner (UMAX Technologies Inc., Fremont, Calif.). Distortions were removed with the unwarping option of the DENDRON program prior to automatic lane and band detection, linking, and analysis of bands. Band data were edited manually before finalization of the band data files. Patterns obtained for each isolate were compared by computing the similarity coefficient (SAB) by the formula SAB = 2 E/(2 E + a + b), where E is the number of bands shared by strains A and B, a is the number of bands unique to strain A, and b is the number of bands unique to strain B. An SAB of 0.0 and 1.0 indicates total unrelatedness and an identical match, respectively, of all bands between two or more strains. Band data from previously analyzed U.S. isolates (FC) (20) stored in the DENDRON database were compared to those from the South African isolates through genesis of mixed dendrograms (28). An arbitrary SAB threshold of 0.70 was chosen to distinguish groups among isolates. This value was higher than the mean SAB for all tested collections in this study and hence more stringent than the mean SAB threshold value of 0.65 used by Pujol et al. (20) in the original cluster analysis of U.S. isolates.

PCR for IS1 sequence.

Three South African isolates from each of the three groups of C. albicans (groups I, II, and III) originally described by Pujol et al. (20) and 21 randomly selected isolates from the South African group (SA) were amplified by PCR (Labline, Melrose Park, Ill.) (14). The IS1 primers used were 5′-GGG AAT CTG ACT GTC TAA TTA A-3′ and 5′-CTT GGC TGT GGT TTC GCT AGA T-3′. Following initial denaturation at 95°C, 35 cycles of 1-min steps were run at 95, 55, and 72°C. The final elongation was for 5 min at 72°C.

Carbohydrate assimilation.

The ability to assimilate glucosamine (GLN) and N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) was assessed using ID 32C strips (BioMérieux SA, Marcy-l'Etoile, France) as specified by the manufacturer. Ten South African isolates from each of the four groups were randomly selected. In addition, 12 U.S. isolates from a previous study (20) were subjected to assimilation testing.

RESULTS

Test and control collections.

Samples were obtained from 1,196 HIV+ patients attending HIV clinics in three hospitals, Kalofong, Pretoria, and GaRankuwa. The patients attending these hospitals were black and originated from urban, semiurban, and rural regions. The proportion of individuals from each hospital who were colonized with yeast ranged between 61 and 65%, and the proportion of yeast that was C. albicans ranged between 77 and 81% (Table 1). Of the four collections of control isolates, only two (GC and UP) included collection data. Of 83 black semiurban individuals in the GC collection, 60% were colonized with yeast, and 58% of these were colonized with C. albicans (Table 1). Of 79 white urban individuals in the UP collection, 54% were colonized with yeast and 67% of these were colonized with C. albicans (Table 1). For DNA fingerprinting with the Ca3 probe, 178, 33, and 38 isolates were randomly selected from the three HIV+ collections P, K, and G, respectively (Table 1). Nearly all of the isolates in the control collections were DNA fingerprinted (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Collection data for South African isolates

| Health statusa | Description | Collection locationd | No. of samples | % of samples that were yeast positive | % of positive samples containing C. albicans | No. of test isolates | No. of isolates fingerprintedf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+ | Black urban, semiurbanb and rural | Pretoria Academic Hospital (P) (Pretoria, Gauteng) | 91 | 61 | 81 | 46 | 33 |

| Kalafong Hospital (K) (Pretoria, Gauteng) | 997 | 63 | 78 | 490 | 178 | ||

| GaRankura Hospital (G) (GaRankura, Gauteng) | 108 | 65 | 77 | 54 | 38 | ||

| Healthy | Black semiurban | Medunsa Oral and Dental Hospital (GC) (GaRunkuwa, Gauteng) | 83 | 60 | 58 | 29 | 21 |

| Black rural | Kruger Park (OKP, KP), Mahonisi (MAH) (Northern Province) | NAe | NA | NA | 45 | 45 | |

| White urbanc | University of Pretoria Oral and Dental Hospital (UP) (Pretoria, Gauteng) | 79 | 54 | 67 | 29 | 29 | |

| White urban | University of Pretoria Oral and Dental Hospital (PC) (Pretoria, Gauteng) | NA | NA | NA | 17 | 17 |

HIV+ patients had tested positive for the virus; healthy patients were included based on the criteria set forth in Materials and Methods.

Semiurban describes settlements 30 miles outside Pretoria.

UP, University of Pretoria patients attending clinic for biannual oral hygiene treatment; PC, clinic staff.

Abbreviations in parentheses refer to collection groups and are used in dendrograms.

NA, samples obtained from other studies in which the number, percent yeast positive, and proportion of C. albicans were unavailable.

Isolates were randomly selected.

DNA fingerprinting with the Ca3 probe.

Total DNA from each isolate was extracted, digested with EcoRI, and run on an agarose gel. The gel was blotted on a membrane, and the Southern blot was hybridized with labeled Ca3. Each gel, containing 16 lanes, included DNA from the reference strain 3153A in the first and/or last lane to facilitate computer-assisted pattern analysis (28). Each Ca3 hybridization pattern (e.g., Fig. 1A) was digitized into the DENDRON data base, processed, unwarped, and automatically analyzed for band positions (28). The similarity coefficient was then computed for every possible pair of analyzed isolates. Dendrograms were then generated for any group of isolates (e.g., the isolates in a single gel [Fig. 1B]) or for all isolates based on the computed SABs. Models based on band positions and intensities could then be generated for each isolate and placed according to positions in the dendrogram for visual comparisons (Fig. 1C).

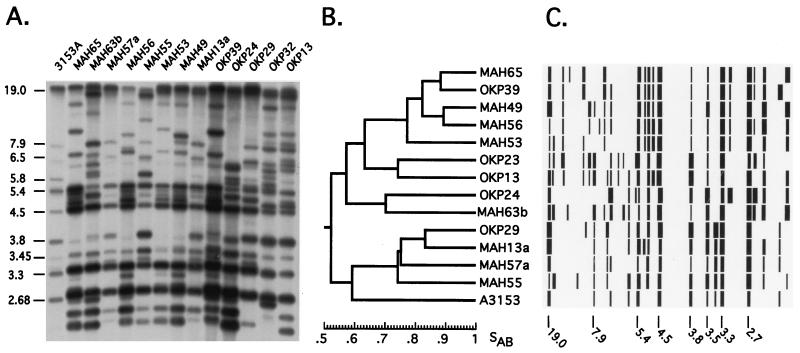

FIG. 1.

Example of Ca3 fingerprint analysis of C. albicans isolates from South African collections. (A) EcoRI-digested DNA of each strain was separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, blotted, and hybridized with the complex C. albicans-specific DNA probe Ca3. Control strain 3153A was run in the first lane to assist in computer-assisted normalization (28). (B) Hybridization patterns were automatically normalized to the internal 3153A control pattern, and the global Ca3 reference pattern in the database, and lanes and bands were automatically identified, generating a matrix of band positions and intensities for all analyzed isolates. The similarity coefficient (SAB) between the patterns of every pair of isolates in a collection was computed, and a dendrogram based on the SAB values was generated. In this case, a dendrogram was generated for the isolates in panel A. (C) Each pattern was then converted into a model of band position and intensity and placed according to its position in the dendrogram. The molecular sizes in kilobases are noted to the left of the hybridization patterns in panel A and under the patterns in panel C.

In a comparison of clustering by Ca3 fingerprinting, randomly amplified polymorphic DNA, and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, it was demonstrated that all three methods separated a collection of 26 isolates from the United States into three clusters or groups (groups I, II, and III), with a few ungrouped “outliers” (20). A subsequent analysis of the same collection combined with an additional collection of U.S. isolates by a different DNA fingerprinting technique again separated the isolates into the same three major clusters (14). Since the Ca3 fingerprints of these isolates were obtained by the same methods used in the present study and stored in a DENDRON data file, we were able to generate mixed dendrograms (28) based on the SABs computed between the isolates in the present study and the U.S. isolates analyzed in the Pujol et al. study (20).

An analysis of the C. albicans isolates from HIV+ patients at Pretoria Academic Hospital reveals a South African-specific group.

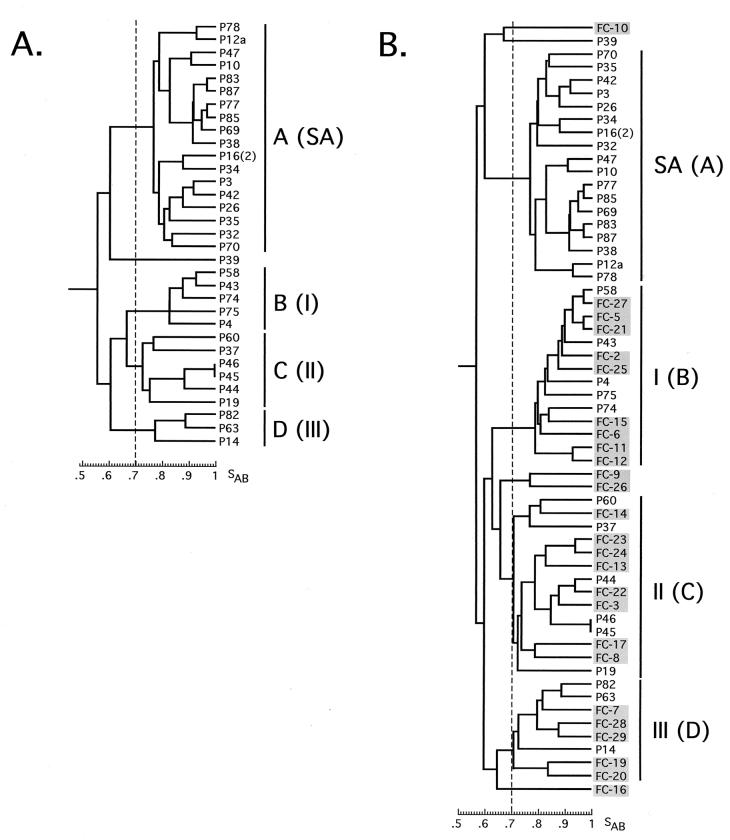

Of the 91 C. albicans isolates collected from HIV+ patients visiting the Pretoria Academic Hospital (Table 1), we fingerprinted 33. The mean SAB (± standard deviation) of this collection was 0.66 ± 0.13. Using an arbitrary SAB threshold of 0.70, four groups (A through D) were readily distinguishable in a dendrogram of these isolates (Fig. 2A). Only 1 of the 33 isolates, P39, did not fall into one of the four groups. To test the relationships between the four groups identified in this collection and the three groups identified in U.S. isolates by Pujol et al. (20) and verified by Lott et al. (14), a mixed dendrogram was generated from the collection of isolates from HIV+ patients and 26 isolates from the Pujol et al. study (20) (which included 9 isolates from group I, 8 isolates from group II, 5 isolates from group III, and 4 outliers [i.e., members of no group]). Four major groups were again distinguishable at an arbitrary threshold of 0.70 (Fig. 2B). All group B isolates in the collection of isolates from HIV+ patients at the Pretoria Academic Hospital mixed with group I isolates of the Pujol et al. collection, all group C isolates mixed with group II isolates, and all group D isolates mixed with group III isolates (Fig. 2B). However, the 18 group A isolates (55%) did not mix with any of the group I, II, or III isolates or the outliers in the Pujol collection (Fig. 2B). The group A isolates formed an independent group (Fig. 2B). Again, only one isolate from an HIV+ individual, P39, did not group (Fig. 2B). We therefore renamed groups B, C, and D of the collection of isolates from HIV+ patients groups I, II, and III, respectively, and we renamed group A “group SA,” for “group South Africa” (Fig. 2B). The proportions of isolates from HIV+ patients visiting the Pretoria Hospital in each of the four groups (groups I, II, III, and SA) are presented in Table 2.

FIG. 2.

(A) A cluster analysis of the Pretoria Academic Hospital isolates from HIV+ black individuals (P) reveals four groups, labeled A, B, C, and D. (B) P isolates plus U.S. isolates from the Pujol et al. (20) collection (FC) reveal four groups, with three (B, C, and D) equivalent to groups I, II, and III of the U.S. collection and the fourth (group A) representing a new South African-specific group (SA). An arbitrary threshold was set at SAB = 0.70.

TABLE 2.

Cluster analysis of the different groups of isolates fingerprinted with the Ca3 probe

| Health statusa | Description | Hospital | Total no. finger- printed | % of isolates in:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | Group II | Group III | Group SA | No group | ||||

| HIV+ | Black, urban, semi- urban,b rural | Pretoria (P) | 33 | 15 | 18 | 9 | 55 | 3 |

| Kalafong (K) | 178 | 20 | 19 | 2 | 52 | 7 | ||

| GaRankuwa (G) | 38 | 13 | 11 | 5 | 58 | 13 | ||

| Total | 249 | 18 | 17 | 4 | 53 | 7 | ||

| Healthy | Black semiurban | Medunsa (GC) | 21 | 24 | 14 | 5 | 48 | 10 |

| Black rural | Kruger Park (OKP, KP), Mahonisi (MAH) | 45 | 20 | 9 | 9 | 56 | 7 | |

| Total | 66 | 21 | 11 | 8 | 53 | 8 | ||

| White urbanc | University of Pretoria (PC, UP) | 46 | 13 | 22 | 20 | 33 | 13 | |

| Mixed | U.S. individuals (Pujol collection, FC)d | 22 | 37 | 27 | 18 | 0 | 18 | |

See Table 1, footnote a.

See Table 1, footnote b.

See Table 1, footnote c.

The Pujol et al. (20) collection was from the United States and included isolates from healthy individuals, HIV+ individuals, and vaginitis patients. The proportions in this case correspond to the 22 isolates obtained from unrelated hosts.

An analysis of C. albicans isolates from HIV+-patients at Kalafong and GaRankuwa hospitals reveals the same South African-specific group.

The same DNA fingerprint analysis was performed on 178 isolates from HIV+ patients visiting the Kalafong Hospital and on 38 isolates from HIV+ patients visiting the GaRankuwa Hospital. The average SABs for the two collections were 0.66 ± 0.13 and 0.66 ± 0.12, respectively. The results are summarized in Table 2. In both collections, isolates separated into groups I, II, III, and SA (Table 2). The proportions in the SA group of both the Kalafong and GaRankuwa collections were similar to those in the Pretoria Academic Hospital collection (Table 2).

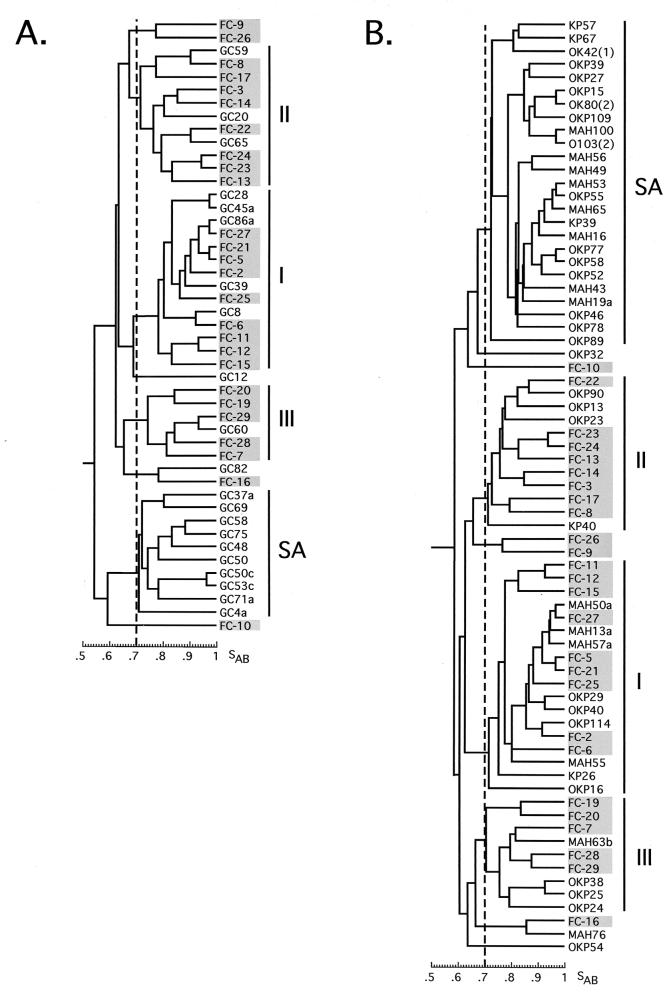

Isolates from healthy black control populations.

For control collections, isolates from healthy black semiurban staff members of the Medunsa Oral and Dental Clinic (GC isolates), and healthy black rural individuals living and working in the Kruger Park (OK and K isolates) and Mahonisi (MAH isolates) area were Ca3 fingerprinted. The average SABs for the two collections were 0.64 ± 0.12 and 0.68 ± 0.12, respectively. Both collections separated into the same four groups observed in the three collections of isolates from HIV+ patients (Table 2; Fig. 3A, and Fig. 3B, respectively). In addition, the proportions of isolates from healthy black semiurban and healthy black rural individuals in the four groups were similar to the proportions of isolates from HIV+ individuals in the four groups (Table 2). Indeed, the proportions of isolates from black HIV+ and from black healthy individuals in group SA were 53% in both cases (Table 2). In the combined dendrogram of isolates from healthy black semiurban individuals (GC isolates) and U.S. isolates from the Pujol et al. collection (FC isolates) in Fig. 3A and in the combined dendrogram of isolates from healthy rural individuals (OKP, KP, and MAH isolates) and U.S. isolates from the Pujol et al. collection (FC isolates) in Fig. 3B, it is clear that the SA and FC isolates never mix in a common cluster.

FIG. 3.

(A) Cluster analysis of the Medunsa isolates from healthy black semiurban individuals (GC) plus U.S. isolates (FC). (B) Cluster analysis of Kruger Park (OKP and KP) and Mahonisi (MAH) isolates from healthy black rural individuals plus U.S. isolates (FC).

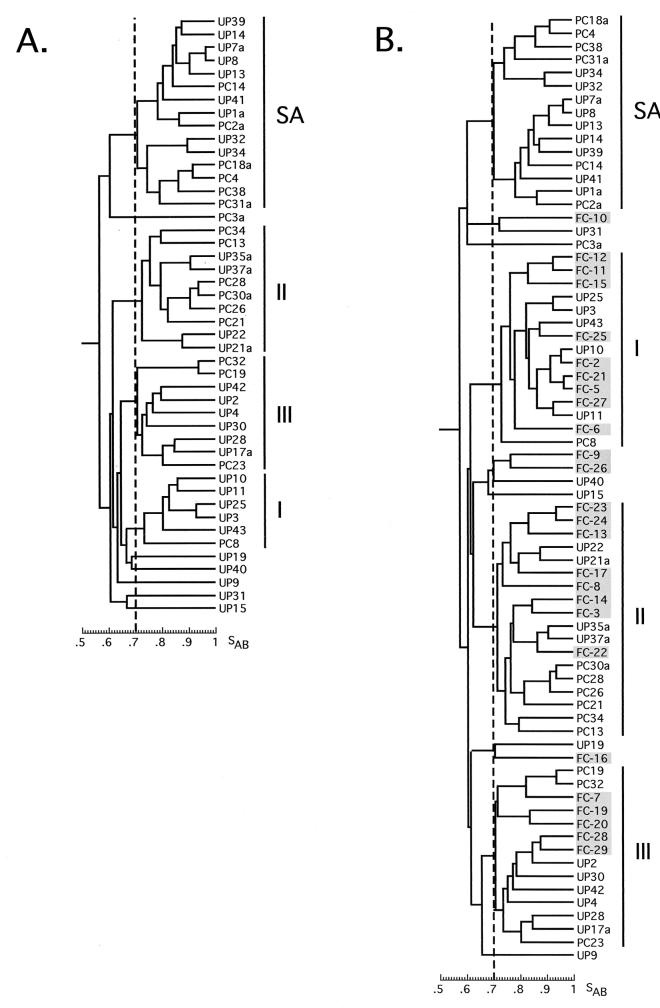

Isolates from the healthy white control populations.

Isolates were also obtained from white urban staff and patients seeking oral hygiene treatment at the University of Pretoria Oral and Dental Hospital. This collection of 46 fingerprinted isolates separated into four groups (Fig. 4A), three of which cogrouped with U.S. isolates in groups I, II, and III, and a fourth group that was devoid of U.S. isolates, the SA group (Fig. 4B). The proportion of isolates in the SA group (33%) was lower than the proportion in the groups from HIV+ individuals (55, 52, and 58%) or the black healthy individuals (48 and 56%). This difference was tested by Fisher's exact test and found to be statistically significant (P > 0.05). Additionally, the proportion of isolates from healthy white individuals in group III was significantly higher than that in the HIV+ and healthy black individuals (Table 2).

FIG. 4.

(A) Cluster analysis of Pretoria isolates from healthy white urban individuals (UP and PC). (B) Cluster analysis of UP and PC isolates plus U.S. isolates (FC).

The SA groups of the South African collections cocluster.

To be sure that the group SA isolates in the separate collections coclustered, mixed dendrograms were generated for every combination of South African collections in this study. A dendrogram was also generated for all 361 South African isolates DNA fingerprinted in this study. In all cases, the SA isolates from the different collections coclustered (data not shown).

SA group fingerprint patterns.

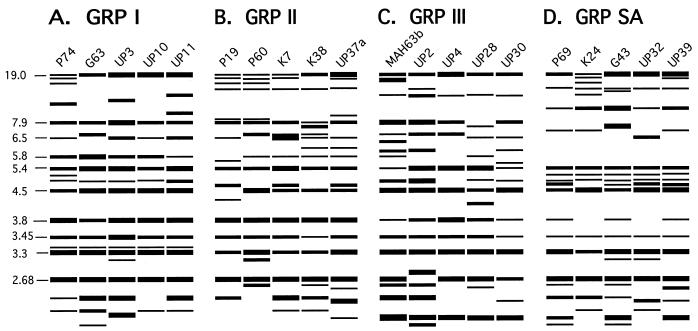

The node separating the SA cluster from the three other clusters (groups I, II, and III) was the deepest rooted in every dendrogram generated for the different South African collections (Fig. 2 to 4). When modeled fingerprint patterns of randomly selected isolates in the SA group were compared to those of randomly selected group I, II and III isolates, there were noticeable differences (Fig. 5). The SA patterns possessed fewer bands in the 5.4- to 6.5-kb region and two more bands in the 4.5- to 5.4-kb region, on average, than did the patterns for groups I, II, and III. To compare the general patterns of group I, II, III, and SA isolates, we used the DENDRON program to measure the proportion of isolates in each group exhibiting bands at 42 molecular sizes ranging from 2.05 to 19.00 kb. In Table 3, data are presented for the bands which are highly invariant for all four groups and the bands which exhibit major differences between groups (30%). First, it should be noted that the patterns of group SA isolates contain five of the six highly invariant bands (5.4, 4.5, 3.5, 3.3, and 2.7 kb) in the Ca3 hybridization pattern of group I, II, and III isolates (Table 3). However, none of the group SA isolates contained the band at 7.9 kb and the large majority of these isolates did not contain the band at 3.8 kb. Both of these bands were highly invariant in isolates from groups I, II, and III (Table 3). Second, of the 13 cases in which one group varied dramatically from the other three, 9 involved dramatic differences in the SA group while only 2 involved a difference in group I, only 1 involved a difference in group II, and only 1 involved a difference in group III (Table 3). These results suggest that groups I, II, and III are more closely related to each other than they are to group SA.

FIG. 5.

DENDRON-generated models of Ca3 fingerprinting patterns of randomly selected isolates from group I (A), group II (B), group III (C), and group SA (D). Molecular sizes in kilobases are presented to the left of the models. Model band widths reflect band intensities.

TABLE 3.

Major band differences between the patterns of group I, II, III, and SA isolates in the present collectiona

| Band size (bp)b | % of isolates exhibiting band in:

|

Group(s) in which % was:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I (n = 64) | Group II (n = 60) | Group III (n = 25) | SA (n = 183) | Highc | Lowc | |

| 15.7 | 8 | 80 | 8 | 95 | II, SA | I, III |

| 14.1 | 14 | 3 | 40 | 9 | III | I, II, SA |

| 13.1 | 9 | 0 | 8 | 40 | SA | I, II, III |

| 11.1 | 16 | 15 | 4 | 84 | SA | I, II, III |

| 8.6 | 13 | 83 | 0 | 1 | II | I, III, SA |

| 7.9 (m) | 95 | 95 | 80 | 0 | I, II, III | SA |

| 6.8 | 3 | 63 | 40 | 2 | II, III | I, SA |

| 6.5 | 92 | 90 | 26 | 4 | I, II | III, SA |

| 6.1 | 20 | 47 | 61 | 7 | II, III | SA |

| 5.8 | 92 | 77 | 32 | 3 | I, II | III, SA |

| 5.6 | 8 | 23 | 32 | 4 | I, II, III, SA | |

| 5.4 (M) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | I, II, III, SA | |

| 5.1 | 22 | 13 | 4 | 85 | SA | I, II, III |

| 4.9 | 89 | 12 | 92 | 79 | I, III, SA | II |

| 4.7 | 3 | 92 | 0 | 85 | II, SA | I, III |

| 4.5 (M) | 98 | 98 | 100 | 100 | I, II, III, SA | |

| 3.8 (m) | 100 | 100 | 80 | 34 | I, II, III, SA | |

| 3.5 (M) | 100 | 98 | 92 | 92 | I, II, III, SA | |

| 3.4 | 91 | 0 | 4 | 3 | I | II, III, SA |

| 3.3 (M) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | I, II, III, SA | |

| 3.1 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 53 | SA | I, II, III |

| 2.7 (M) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | I, II, III, SA | |

| 2.3 | 73 | 13 | 0 | 41 | I, SA | II, III |

| 2.2 | 20 | 27 | 100 | 59 | III, SA | I, II |

The DENDRON software program was used to compute the proportion of isolates in each group exhibiting a band at 42 molecular band sizes. Only bands that are relatively invariant or monomorphic and bands showing major differences between groups (i.e., greater than 30% between two or more groups) are described. Bands which show a large difference in only one group are presented in bold italic type.

Bands that are monomorphic or highly invariant in all groups are denoted in parentheses by M, and bands that are monomorphic or highly invariant only in groups I, II, and III are denoted in parentheses by m.

When more than 34% of isolates possessed a particular band, the proportion was deemed high, and when less than 34% possessed a particular band, the proportion was deemed low.

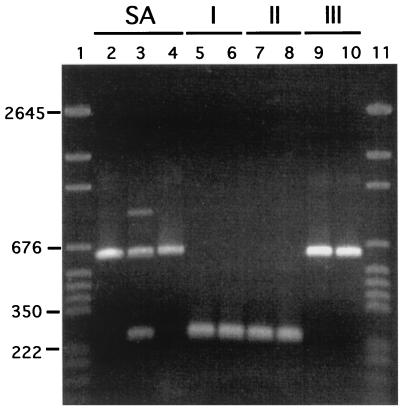

SA isolates contain IS1.

Lott et al. (14) demonstrated the presence of the IS1 element in the 25S rRNA gene of a majority of group III isolates and its complete absence in group I and group II isolates. We therefore tested 21 SA isolates and 3 isolates each from groups I, II, and III for the IS1 element by using PCR with specific primers. A total of 13 of the 21 SA isolates and all 3 group III isolates contained IS1. The three group I and three group II isolates did not contain IS1. In Fig. 6, the PCR products are presented for three positive SA isolates, two positive group III isolates, two negative group I isolates, and two negative group II isolates. Only the group SA and group III isolates possess the 626-bp band containing the 379-bp IS1 group I intron. These results demonstrate that as in the case of group III isolates, the IS1 element is still present in a majority of group SA isolates.

FIG. 6.

IS1 is present in group III (lanes 9, 10) and group SA (lanes 2, 3, and 4) isolates but not in group I (lanes 5 and 6) and group II (lanes 7 and 8) isolates. IS1 was amplified with IS1-specific primers (14). The IS1-containing amplification product was 626 bp, and the amplification product lacking IS1 was 247 bp. Standards were run in lanes 1 and 11 (pGEM DNA markers from Promega, Madison, Wis.), and select standard sizes are noted to the left of the gel in kilobases.

Assimilation of NAG.

Recently, atypical strains of C. albicans from Angola and Madagascar were characterized for genetic relatedness (18, 31). They were demonstrated to be unable to assimilate NAG or GLN and to be slow growing at 37°C. We therefore tested 10 random isolates from each group for their capacity to assimilate NAG and GLN and for their rate of growth at 37°C. All of the tested isolates in group SA as well as in groups I and III and all but one isolate in group II assimilated NAG and GLN. None of the isolates grew slowly at 37°C. These results distinguish the isolates in the SA group from the atypical Angola and Madagascar isolates.

No group association with oropharyngeal candidiasis.

The proportions of isolates from HIV+ patients with and without oropharyngeal candidiasis (erythematous or pseudomembranous) are summarized according to hospital in Table 4. Group proportions were similar in individuals with and without clinical signs of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Fisher's exact tests of groups in the three hospital collections revealed no statistically significant differences.

TABLE 4.

Proportions of isolates from HIV+ patients with and without oral candidiasis in the four genetic groups

| Hospital | Disease state | Total no. of isolates | % of isolates in:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | Group II | Group III | Group SA | No group | |||

| Pretoria | No infection | 20 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 50 | 5 |

| Infection | 13 | 15 | 15 | 8 | 62 | 0 | |

| Kalafong | No infection | 122 | 18 | 20 | 3 | 53 | 6 |

| Infection | 56 | 25 | 16 | 0 | 50 | 9 | |

| GaRankuwa | No infection | 28 | 11 | 14 | 7 | 54 | 14 |

| Infection | 10 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 70 | 10 | |

| Total | No infection | 170 | 17 | 18 | 5 | 53 | 7 |

| Infection | 79 | 22 | 14 | 3 | 54 | 8 | |

DISCUSSION

Identification of a South African clade of C. albicans.

In 1997, Pujol et al. (20) characterized a test collection of U.S. isolates of C. albicans and demonstrated through cluster analysis three genetically distinct groups (groups I, II, and III). In this study, it was demonstrated that three independent genetic fingerprinting methods (Ca3, randomly amplified polymorph DNA, and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis) separated a majority of isolates into the same three groups. Lott et al. (14) verified these three groups by using a fourth DNA fingerprinting method. Here, using Ca3 fingerprinting, we have identified four groups in South African isolates from black HIV+ patients, black healthy individuals, and white healthy individuals. Since we used exactly the same Ca3 fingerprinting procedures and the same computer-assisted methods to analyze and store the data as did Pujol et al. (20), we generated mixed dendrograms of the South African and U.S. isolates in order to identify group I, II, and III isolates in the former collection. The results were unambiguous. Isolates in three of the four South African groups coclustered with isolates from the three U.S. groups, identifying those groups as I, II, and III. Isolates that were outliers (i.e., did not group) in the U.S. collection remained outliers in the mixed dendrograms. However, no U.S. isolates grouped with South African isolates in the fourth group. This South African-specific group was labeled group SA. It represents more than half of all isolates from HIV+ and healthy black individuals.

The proportion of group SA isolates differs between healthy blacks and healthy whites.

The proportion of SA isolates in HIV+ individuals sampled at the Pretoria, Kalafong, and GaRankuwa hospitals was 55, 52, and 58%, respectively. The proportion was 48% in healthy black individuals sampled at the Medunsa Oral and Dental Hospital and 56% in healthy black individuals sampled at the Kruger Park and Mahonisi area. The average proportion of SA isolates in the collections from HIV+ black patients and healthy black individuals was 53% in both cases. However, the proportion of SA isolates from healthy white individuals was 33%. The difference between this group and the other groups was statistically significant. If group SA isolates also prove to be absent from Europe, then the decreased proportion of SA isolates among white South Africans would suggest that their yeast carriage characteristics straddle the fence between U.S./European and black South African carriage. We are presently testing European isolates for the presence of group SA isolates and plan to do the same for collections across the African continent.

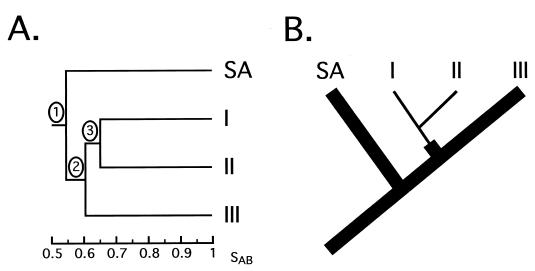

Group I, II, and III isolates are more closely related to each other than to group SA isolates.

In the dendrograms generated for each of the South African collections, the node separating group SA from groups I, II, and III was more deeply rooted than the nodes separating groups I, II, and III. For example, while the node value between the SA isolates and the other three groups (groups I, II, and III) was 0.55 in the Pretoria Academic Hospital collection of isolates from HIV+ individuals, the nodes separating groups I, II, and III ranged between 0.60 and 0.66 (Fig. 2A). This result suggests that group SA diverged from a progenitor of groups I, II, and III. A model that reflects the structure of these dendrograms is presented in Fig. 7A. This difference, based on dendrogram structure, was supported by an analysis of major band differences between the four groups. In this case, a major band difference was defined as a dramatic increase or decrease in the proportion of isolates of one group containing a band (Table 3). While groups I, II, and III exhibited two, one, and one major band differences, respectively, group SA exhibited nine.

FIG. 7.

(A) Model of node hierarchy observed in the dendrograms generated for all of the South African collections. (B) Tree representing the evolution of the four groups of C. albicans, based on node hierarchy in the dendrograms (panel A) and the presence of IS1. This tree is based on the one developed by Lott et al. (14) for the relationship of groups I, II, and III. The thinner branches reflect complete loss of IS1 from a group.

Lott et al. (14) also demonstrated that while a majority of group III isolates contained the IS1 sequence in the 25S rRNA gene, all group I and II isolates lacked IS1. This and additional differences led them to propose a tree in which group III isolates belonged to an older, more diverse evolutionary group than the more closely related group I and II isolates. We have demonstrated that the majority of SA isolates, like group III isolates (14), contain IS1. These results, combined with the above analysis of dendrogram nodes, suggest a tree in which first group SA and a progenitor of groups I, II, and III diverge and then group III and a progenitor of groups I and II diverge (Fig. 7B). The loss of IS1 is noted by narrower branches (Fig. 7B).

Relationship between groups and infectivity.

We have found no evidence that any particular strain is more virulent than any other in respect to causing infection. In all cases, the same proportion of each group was found in black HIV+ patients with and without symptoms of oropharyngeal infection. However, if we assume that the success of this opportunistic pathogen is based on its capacity both to live as a commensal and to cause infection, we can broaden our definition of virulence to include commensalism plus infection (i.e., all colonization). In that case, we can conclude that in South Africa, group SA isolates are predominant both in commensalism and in infection and, by that criterion, the most successful. If this is the case, and given that one-half of the commensals in black South Africans and one-third of the commensals in white South Africans are group SA isolates, one wonders why SA isolates have not achieved the same success worldwide.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to W. F. P. van Heerden and R. Senekal, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, who participated in the collection of isolates.

This research was supported by NIH grant AI2392 to D.R.S. and a Fogarty International Research Fellowship (TWO5473) to E.B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, J., T. Srikantha, B. Morrow, S. H. Miyasaki, T. C. White, N. Agabian, J. Schmid, and D. R. Soll. 1993. Characterization and partial nucleotide sequence of the DNA fingerprinting probe Ca3 of Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:1472-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arendorf, T. M., and D. M. Walker. 1980. The prevalence and intra-oral distribution of Candida albicans in man. Arch. Oral Biol. 25:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brawner, D. L., and A. J. Hovan. 1995. Oral candidiasis in HIV-infected patients. Curr. Top. Med. Mycol. 6:113-125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman, D., D. Sullivan, B. Harrington, K. Haynes, M. Henman, D. Shanley, D. Bennett, G. Moran, C. McCreary, and L. O'Neill. 1997. Molecular and phenotypic analysis of Candida dubliniensis: a recently identified species linked with oral candidosis in HIV-infected and AIDS patients. Oral Dis. 3:S96-S101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman, D. C., D. E. Bennett, D. J. Sullivan, P. J. Gallagher, M. C. Henman, D. B. Shanley, and R. J. Russell. 1993. Oral Candida in HIV infection and AIDS: new perspectives/new approaches. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 19:61-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coogan, M. M., S. P. Sweet, and S. J. Challacombe. 1994. Immunoglobulin A (IgA), IgA1 and IgA2 antibodies to Candida albicans in whole and parotid saliva in human immunodeficiency virus infection and AIDS. Infect. Immun. 63:892-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glick, M., B. C. Muzyka, D. Lurie, and L. M. Salkin. 1994. Oral manifestations associated with HIV-related disease as markers for immune suppression and AIDS. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol 77:344-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenspan, D., J. S. Greenspan, M. Schiodt, and J. J. Pindborg (ed.). 1990. AIDS and the mouth, p. 85-90. Munksgaared, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 9.Hunter, K. D., J. Gibson, P. Lockhart, A. Pithie, and J. Bagg. 1998. Fluconazole-resistant Candida species in the oral flora of fluconazole-exposed HIV-positive patients. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 85:558-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson, E. M., D. W. Warnock, J. Luker, S. R. Porter, and C. Scully. 1995. Emergence of azole drug resistance in Candida species from HIV-infected patients receiving prolonged fluconazole therapy for oral candidosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 35:103-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein, R. S., C. A. Harris, C. R. Small, B. Moll, M. Lesser, and G. H. Friedland. 1984. Oral candidiasis in high-risk patients as the initial manifestation of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 311:354-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lockhart, S., J. J. Fritch, A. S. Strudevant Meier, K. Schröppel, T. Srikantha, R. Galask, and D. R. Soll. 1995. Colonizing populations of Candida albicans are clonal in origin but undergo microevolution through C1 fragment reorganization as demonstrated by DNA fingerprinting and C1 sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1501-1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lockhart, S., C. Pujol, S. Joly, and D. R. Soll. 2001. Development and use of complex probes for DNA fingerprinting the infectious fungi. J. Med. Mycol. 39:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lott, T. J., D. A. Logan, B. P. Holloway, R. Fundyga, and J. Arnold. 1999. Towards understanding the evolution of the human commensal yeast, Candida albicans. Microbiology 145:1137-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marco, F., S. Lockhart, M. Pfaller, C. Pujol, M. S. Rangel-Frausto, T. Wiblin, H. M. Blumberg, J. E. Edwards, W. Jarvis, L. Saiman, J. E. Patterson, M. G. Rinaldi, R. P. Wenzel, the NEMIS Study Group, and D. R. Soll. 1999. Elucidating the origins of nosocomial infections with Candida albicans by DNA fingerprinting with the complex probe Ca3. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2817-2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nielsen, H., K. D. Bentsen, L. Hojtved, E. H. Willemoes, F. Scheutz, M. Schiodt, K. Stoltze, and J. J. Pindborg. 1994. Oral candidiasis and immune status of HIV-infected patients. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 23:140-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfaller, M. A., S. R. Lockhart, C. Pujol, J. A. Swails-Wenger, S. A. Messer, M. B. Edmond, R. N. Jones, R. P. Wenzel, and D. R. Soll. 1998. Hospital specificity, region specificity and fluconazole resistance of Candida albicans bloodstream isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1518-1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinto de Andrade, M., G. Schonian, A. Forsch, L. Rosado, I. Costa, M. Muller, W. Presber, G. Mitchell, and H. J. Tietz. 2000. Assessment of genetic relatedness of vaginal isolates of Candida albicans from different geographical origins. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 290:97-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powderly, W. G., K. H. Mayer, and J. R. Perfect. 1999. Diagnosis and treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients with HIV: a critical reassessment. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 15:1405-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pujol, C., S. Joly, S. R. Lockhart, S. Noel, M. Tibayrenc, and D. R. Soll. 1997. Parity among the randomly amplified polymorphic DNA method, multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, and southern blot hybridization with the moderately repetitive DNA probe Ca3 for fingerprinting Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2348-2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pujol, C., F. Renaud, M. Mallie, T. de Meeus, and J. M. Bastide. 1997. Atypical strains of Candida albicans recovered from AIDS patients. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 35:115-121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Revankar, S. G., W. R. Kirkpatrick, R. K. McAtee, O. P. Dib, A. W. Fothergill, S. W. Redding, M. G. Rinaldi, and T. F. Patterson. 1996. Detection and significance of fluconazole resistance in oropharyngeal candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J. Infect. Dis. 174:821-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadhu, C., M. J. McEachern, E. P. Rustchenko-Bulgac, J. Schmid, D. R. Soll, and J. Hicks. 1991. Telomeric and dispersed repeat sequences in Candida yeasts and their use in strain identification. J. Bacteriol. 173:842-850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scherer, S., and D. A. Stevens. 1987. Application of DNA fingerprinting methods to epidemiology and taxonomy of Candida species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:675-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmid, J., F. C. Odds, M. J. Wiselka, K. G. Nicholson, and D. R. Soll. 1992. Genetic similarity and maintenance of Candida albicans strains in a group of AIDS patients demonstrated by DNA fingerprinting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:935-941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmid, J., E. Voss, and D. R. Soll. 1990. Computer-assisted methods for assessing strain relatedness in Candida albicans by fingerprinting with the moderately repetitive sequence Ca3. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:1236-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schorling, S. R., H. C. Kortinga, M. Froschb, and F. A. Muhlschlegel. 2000. The role of Candida dubliniensis in oral candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 26:59-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soll, D. R. 2000. The ins and outs of DNA fingerprinting the infectious fungi. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:332-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sullivan, D. J., T. J. Westerneng, K. A. Haynes, D. E. Bennett, and D. C. Coleman. 1995. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of a novel species associated with oral candidosis in HIV-infected individuals. Microbiology 141:1507-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sweet, S. P., S. J. Challacombe, and J. R. Naglik. 1995. Whole and parotid saliva IgA and IfA-subclass responses to Candida albicans in HIV infection. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 37:1031-1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tietz, H. J., A. Kussner, M. Thanos, M. Pinto de Andrade, W. Presber, and G. Schonian. 1995. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of unusual vaginal isolates of Candida albicans from Africa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2462-2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vargas, K. G., S. A. Messer, M. A. Pfaller, S. R. Lockhart, J. T. Stapleton, J. Hellstein, and D. R. Soll. 2000. Elevated phenotypic switching and drug resistance of Candida albicans from human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals prior to the first thrush episode. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3595-3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu, J., T. G. Mitchell, and R. Vilgalys. 1999. PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analyses reveal both extensive colonality and local genetic differences in Candida albicans. Mol. Ecol. 8:59-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu, J., R. Vilgalys, and T. G. Mitchell. 1999. Lack of genetic differentiation between two geographically diverse samples of Candida albicans isolated from patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J. Bacteriol. 181:1369-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]