Abstract

The emergence of resistance to antituberculosis drugs is a relevant matter worldwide, but the retrieval of antibiograms for Mycobacterium tuberculosis is severely delayed when phenotypic methods are used. Genotypic methods allow earlier detection of resistance, although conventional approaches are cumbersome or lack sensitivity or specificity. We aimed to design a new real-time PCR method to detect rifampin (RIF)- and isoniazid (INH)-resistant M. tuberculosis strains in a single reaction tube. First, we characterized the resistant isolates in our area of Spain by DNA sequencing. Some mutation was found within the rpoB core region in all the RIF-resistant (RIFr) strains. Forty-six percent of the INH-resistant (INHr) strains showed a mutation in katG codon 315, and most of these were associated with high MICs. Eighteen of the RIFr, INHr, and multidrug-resistant strains sequenced were tested by our real-time PCR assay; and full concordance of the results of the PCR with the sequencing data was obtained. In addition, a blind test was performed with a panel of 15 different susceptible and resistant strains from throughout Spain, and our results were also in 100% agreement with the sequencing data. Ours is the first assay based on rapid-cycle PCR able to simultaneously detect in a single reaction tube a large variety of mutations associated with RIF resistance (12 different mutations affecting 8 independent codons, including the most prevalent mutations at positions 526 and 531) and the most frequent INH resistance mutations. Our design could be a model for new, rapid genotypic methods able to simultaneously detect a wide variety of antibiotic resistance mutations.

The emergence of resistance to antituberculosis (anti-TB) drugs is a relevant matter worldwide and has been reported in several studies (5, 18, 20). The standard treatment for TB is a multidrug regimen that is based on isoniazid (INH) and rifampin (RIF), the drugs most efficaceous against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. The development of resistance to these two drugs, however, means that the efficacy of standard anti-TB treatment is reduced by up to 77% (12).

The detection of resistant M. tuberculosis strains is generally performed by phenotypic assays, which require the isolate to be cultured in the presence of the different drugs. This usually means unacceptable delays in the detection of resistance and makes it difficult to adhere to the recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the reporting of resistance patterns within 28 days of receipt of the specimen in the laboratory (25).

Methods that guarantee the early detection of resistant M. tuberculosis strains are required in order to avoid delays in the initiation of effective therapies and to prevent the transmission of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains, which have been responsible for notorious outbreaks (1, 4, 7).

The molecular basis of resistance to anti-TB drugs is becoming clearer (2, 19). More than 95% of RIF-resistant (RIFr) strains are associated with mutations within an 81-bp region of the rpoB gene (17). Between 60 and 70% of the INH-resistant (INHr) strains encode mutations in katG, and a specific mutation (in codon 315 of the katG gene) is responsible for many of these cases of resistance (19). These findings have led to the development of different genotypic approaches to the more rapid prediction of resistance in M. tuberculosis, especially resistance to RIF and INH (6, 8, 21, 26). Our aim was to design a new genotypic approach (i) that is based on rapid cycle real-time PCR, (ii) that can simultaneously detect resistance to RIF and INH in a single reaction tube, and (iii) that is able to detect a wide variety of resistance mutations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Selection of strains.

Since 1996, a phenotypic susceptibility assay (MB/BacT [based on the agar proportion method]; Organon Teknika, Durham, N.C.) has been performed in our laboratory for determination of the susceptibility to RIF, INH, ethambutol, and streptomycin of at least one of the M. tuberculosis isolates cultured from each TB episode. The resistance of all strains found to be drug resistant was confirmed by the agar proportion method, and the resistant strains were stored frozen. Among the 816 M. tuberculosis strains cultured from January 1996 to December 2000, 40 INHr and 22 RIFr isolates were obtained. Among them, 26 INHr and 11 RIFr strains were available for analysis. As controls, 20 strains found to be susceptible after testing by the agar proportion method were selected for analysis.

For the blind test, a panel consisting of 15 isolates which represented a selection of resistant strains retrieved from throughout Spain (provided by the Mycobacterium Reference Laboratory, Madrid, Spain) was used.

DNA extraction.

Crude extracts of genomic DNA were obtained from cultures grown in Mycobacterium Growth Indicator Tube (MGIT) medium. For the blind panel, crude extracts were not obtained because the panel consisted of purified DNA. For the extraction of DNA, 1 ml of liquid culture was taken and the bacteria were inactivated by boiling for 10 min. The cells were centrifuged, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of lysis solution (a 1:16 dilution in fresh MGIT medium of reagents 1 and 2 [lysis reagents from the Accuprobe culture identification reagent kit; GenProbe Inc., San Diego, Calif.]). A 100-μl volume of glass beads (diameter, 0.1 μm) was added, and the mixture was sonicated in a bath for 5 min.

MICs.

The MICs of RIF and INH for the resistant strains were obtained by the E-test method (AB BioDisk, Solna, Sweden), according to the technical guidelines for the E-test (E-test technical guide no. 6 [AB BioDisk, N.A., Inc., Piscataway, N.J., 1998]). The plates with the E-test strips were read after 10 days of incubation.

Enzymatic screening of INHr strains.

The strains which were phenotypically resistant to INH were screened for mutations in the codon at position 315 of the katG gene. As a template for katG amplification, 0.5 μl of the crude extract was used and 25 pmol (each) of primers TB86 and TB87 (21) was added to the reaction mixture. The amplicons were detected in agarose gels and afterwards were digested with MspAI at 37°C for 1 h. The restriction products were run together with molecular markers VIII and IX (Roche) in polyacrylamide gels by using the GenePhor system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). The gels were stained with silver (silver staining kit; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Strains without mutations in codon 315 of the katG gene (AGC) gave four products of 7, 46, 68, and 89 bp, while mutants rendered three bands of 7, 89, and 104 due to the loss of a restriction target (13).

DNA sequencing reactions.

DNA sequencing was performed for rpoB (with primers TR8 and TR9 [23]) of the RIFr strains and for katG (with primers TB86 [23] and katGA [5′-CGTACAGGATCTCGAGGAAACTGT-3′]) of the strains with a mutation in codon 315 of the katG gene. Amplicons were obtained and sent to an external laboratory that used an ABI Prism instrument.

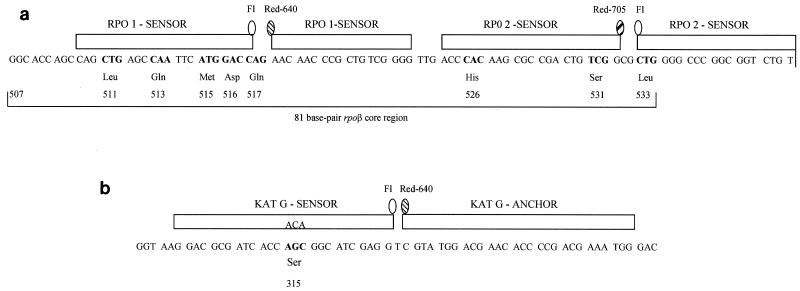

Design of probes for detection of mutations in rpoB.

Pairs of fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) probes were used for the assay. In a novel design, we used each of the two FRET probes in a set as sensors of mutations but did not use the standard anchor-sensor design. In our design, the melting temperature (Tm) of each of the probes in a FRET pair was equivalent so that we could efficiently search for mutations throughout the region covered by the set of probes. We assumed that mutations within the sequence covered by any of the two adjacent probes would lead to changes in the Tm of the probes. Two adjacent pairs of these “dual-sensor” FRET probes were designed to cover the entire rpoB core region (Fig. 1a) One member of the pair of probes (RPO1 probes) was labeled with fluorescein and Red 640 and was specific for the 5′ half of the core, from codons 510 to 523. The other pair of probes (RPO2 probes) was labeled with fluorescein and Red 705 and was specific for the 3′ half of the core, from codons 525 to 539. This different fluorimetric label for each member of the pair of probes allows the independent detection of mutations in each part of the gene through the two different spectrophotometric channels available in the LightCycler instrument (channels F2 and F3). Therefore, our design allows the independent analysis of two portions of rpoB: the 5′ region, which has a low frequency of resistance mutations, and the 3′ region, which has a higher frequency of mutations (including mutations at the hot spots at codons 526 and 531). Both pairs of probes were designed to be homologous to the wild-type (wt) sequence, and thus, the highest Tm in the melting assay is expected for strains that lack mutations. Mutations in the sequence covered by the probes should lead to lower Tms for the probes.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the rpoB (rpoβ) core (a) and katG (b) regions that include the mutations for resistance to RIF and INH. The FRET probes used in the real-time PCR assay are indicated by the boxes above the corresponding complementary sequence. Codon coordinates are indicated as a reference. The mutations studied and the corresponding nucleotide substitutions are indicated below the affected codons. The fluorescein and Red labels are indicated. For the katG region the probe designed to be complementary with ACA in codon 315 is indicated.

Design of probes for detection of mutations in katG.

For the detection of mutations in the katG region, the probe design was standard because, in this case, we were interested in detecting only the most prevalent mutations, which map in one codon (katG codon 315). Therefore, a set of conventional FRET probes was designed (anchor-sensor design). This pair of probes was labeled (Fig. 1b) with fluorescein and Red 640, which means that these probes share both the dye and the fluorimetric channel (channel F2) with the RPO1 probes. In order to allow the simultaneous detection of mutations with these two sets of equally labeled probes in channel F2, the katG-specific probes were designed to have Tms higher than those of the RPO1 probes. This was to rule out the overlap of the fluorescence signals of each set of probes when Tms were measured in the same channel. Additionally, the katG-specific probe sequences were designed to be homologous to a mutant sequence in codon 315 (ACA). Annealing with the wt sequence (AGC) would lead to the lowest Tm, meaning that the presence of mutations (the two most frequent substitutions are ACC and ACA) would increase the Tm of the probe. Once again, this rules out overlap with the RPO1 signal when mutations lead to reductions in the Tms of the RPO1 probes.

All probes were synthesized by TIB MOL BIOL (DNA synthesis service; Roche Diagnostics, Berlin, Germany).

Real-time PCR and fluorimetric detection of mutations.

Real-time PCR allows the simultaneous detection of the PCR products while the amplification reaction is running. It uses different fluorescence reagents that bind specifically or nonspecifically to DNA, allowing the PCR to be monitored through the measurement of the fluorescent signal. If labeled DNA probes are used, the PCR signal corresponds specifically to the amplification of the target. Different probes can be designed to discriminate between wt or mutant variants with the same DNA template. Therefore, real-time PCR allows genetic data to be obtained at the same time as the amplification of the DNA.

In our study we used FRET probes for the detection of mutations. FRET probes consist of two probes that are designed to hybridize adjacent to each other when they find their specific complementary sites. One end of one of the probes is labeled with fluorescein, and the adjacent end of the other probe is labeled with another fluorescent dye. The LightCycler instrument activates the fluorescein, causing activation of the adjacent dye, which emits fluorescence at a different wavelength (640 or 705 nm). The emission of a signal at 640 or 705 nm occurs only if the probes are bound to their specific targets.

The detection of mutations within the DNA regions covered by the FRET probes is based on the differential patterns of denaturation of the probes which are bound either to homologous sequences or to sequences with a mutation. The Tms in each of the cases will be different. Therefore, differences in the Tms for the probes with respect to those obtained when assaying the probes with wt sequences indicate the presence of a mutation in the DNA region covered by the probes.

Design of the real-time PCR.

For the real-time PCR, the rpoB and katG amplicons were first coamplified in the same reaction tube. Three pairs of probes were also included in the same reaction tube for the simultaneous analysis of the rpoB (probes RPO1 and RPO2) and katG (probe KATG) regions. When the amplification was completed, a melting step was performed, in which the temperature of the tube was slowly increased to analyze the melting pattern of each pair of probes. Melting of the RPO1 and KATG probes (labeled with fluorescein and Red 640) was monitored in channel F2 of the LightCycler instrument, and melting of the RPO2 probes (labeled with fluorescein and Red 705) was monitored in channel F3.

The Tm of each of the probes for the wt sequence was empirically calculated as the average value of the Tms obtained in nine independent assays. If a mutation was present, a mismatch would occur between the probe and the target and the Tm of the probe would deviate with respect to the reference value for the wt. The standard deviations of the Tms for probes RPO1, RPO2, and KATG were 0.22, 0.09, and 0.17°C. In all cases in which the deviations in the Tm were higher than two times the standard deviation, a mutation was suspected.

Experimental procedure.

We used 2 μl of a 1:100 dilution from the crude extract as a template for the PCR. The rpoB and katG genes were coamplified in the same reaction tube with primers TR8, TR9 (rpoB), and TB86 and katGA (katG) (23) and with primer katGA (5′-CGTACAGGATCTCGAGGAAACTGT-3′). The efficient coamplification of both targets was previously tested in polyacrylamide gels, in which two products of the expected sizes of 157 and 210 bp were detected. The reaction mixture for the PCR was composed of 2 μl of reaction mixture (LC FastStart plus deoxynucleotide mix; Roche), 10 pmol of each of the primers, 4 mM MgCl2, and three sets (pairs) of FRET probes (two sets to cover rpoB [RPO1 and RPO2 probes] and the other pair to cover the katG region [each of the Red-labeled probes at a concentration of 0.2 μM and each of the fluorescein-labeled probes at a concentration of 0.1 μM]), which were added to the same reaction mixture for the simultaneous detection of mutants encoding resistance to either RIF or INH. The final reaction volume was 20 μl. Prior to PCR a preincubation step (95°C for 7 min) was performed to activate the FastStart enzyme. The PCR consisted of 40 cycles with the following thermal sequence: 95°C for 10 s, 55°C for 8 s, and 72°C for 20 s. The reaction was performed in capillary tubes in a LightCycler instrument.

The melting step involved two sequential melting reactions, and the measurements were taken only during the second melting step. A post-PCR melting step was introduced before the definitive measurements because, for reasons unknown to us, the quality of the melting profiles was higher after this “training” step. For the first melting step the profile was 95°C for 5 s, 65°C (annealing temperature) for 30 s, 40°C for 0 s, and 95°C for 0 s. For the second melting step the profile was 95°C for 5 s, 60°C (annealing temperature) for 30 s, 40°C for 0 s, and 95°C for 0 s, with a rate of increase of 0.2°C/s and the continuous acquisition of fluorescence in the last step. Temperature increases for melting were fixed at 20°C/s for all steps except the fluorescence acquisition step, for which a rate of increase of 0.2°C/s was selected in order to monitor precisely the melting of the probe.

RESULTS

Characterization of RIFr strains.

Of all the M. tuberculosis strains cultured in our laboratory over the last 5 years, 2.7% have been phenotypically resistant to RIF. Eleven of these RIFr strains (Table 1, isolates 1 to 11) were available for characterization, and a mutation within the rpoB core region was found in all resistant strains. A high degree of genotypic variability was detected, with seven different mutations found for the 11 RIFr strains. Mutations were located at four independent codons (Table 1, codons 515, 516, 526, and 531), and 526 and 531 were the two most frequently affected codons (9 of 11 strains). RIF MICs ranged from 12 to >256 μg/ml, and the higher MICs were not associated with any specific mutation or codon.

TABLE 1.

Real-time PCR data for the resistant strains selected from our collection and sequencing data obtained for all mutant strains

| Isolate no. | Gene and codon no. affected | Nucleotide substitution | Amino acid substitution | Deviation of Tm (°C) from that for wta

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPO1 probe (65.2°C) | RPO2 probe (65.1°C) | KATG probe (69.9°C) | ||||

| 1 | rpoB 531 | TCG→TTG | Ser→Leu | −6.41 | ||

| katG 315 | AGC→ACC | Ser→Thr | +2.70 | |||

| 2 | rpoB 526 | CAC→TAC | His→Tyr | −1.42 | ||

| katG 315 | AGC→ACC | Ser→Thr | +2.80 | |||

| 3 | rpoB 526 | CAC→CTC | His→Leu | −0.66 | ||

| 4 | rpoB 531 | TCG→TTG | Ser→Leu | −6.41 | ||

| katG 315 | AGC→ACA | Ser→Thr | +2.80 | |||

| 5 | rpoB 531 | TCG→TGG | Ser→Trp | −6.92 | ||

| 6 | rpoB 526 | CAC→GAC | His→Asp | −3.03 | ||

| 7 | rpoB 531 | TCG→TGG | Ser→Trp | −6.76 | ||

| 8 | rpoB 531 | TCG→TTG | Ser→Leu | −6.52 | ||

| 9 | rpoB 516 | GAC→GTC | Asp→Val | −2.48 | ||

| katG 315 | AGC→ACC | Ser→Thr | +2.80 | |||

| 10 | rpoB 526 | CAC→GAC | His→Asp | −3.19 | ||

| 11 | rpoB 515-516 | Deletion TG-G | Asp-Asn→Met | −8.39 | ||

| 12-18 | katG 315 | AGC→ACC/ACA | Ser→Thr | +2.80 | ||

Deviations in the Tms for the probes (RPO1, RPO2, and KATG) compared with the reference value for the wt (given in parentheses).

Characterization of INHr strains.

Of all the M. tuberculosis strains cultured in our laboratory over the last 5 years, 4.9% were phenotypically resistant to INH. Twenty-six INHr strains were available for characterization. A mutation at codon 315 in katG was found in 46% (12 of 26) of the resistant strains. High INH MICs (>3 μg/ml) were obtained for 92% of the resistant strains with a mutation in codon 315 of katG. INH MICs were low (<1 μg/ml) for 65% of the resistant strains without this mutation.

Genotypic detection of resistance by real-time PCR.

In order to analyze the ability of our real-time PCR design to rapidly detect resistance to RIF and INH in a single-tube format, a set of strains selected from among those previously characterized by DNA sequencing was chosen for analysis. The selection was composed of seven RIFr strains (Table 1, isolates 3, 5 to 8, and 10 to 11), seven INHr strains with mutations at katG codon 315 (Table 1, isolates 12 to 18), and four MDR strains (Table 1, isolates 1, 2, 4, and 9) strains. In addition, 10 RIF-susceptible and 10 INH-susceptible strains were included as controls for specificity.

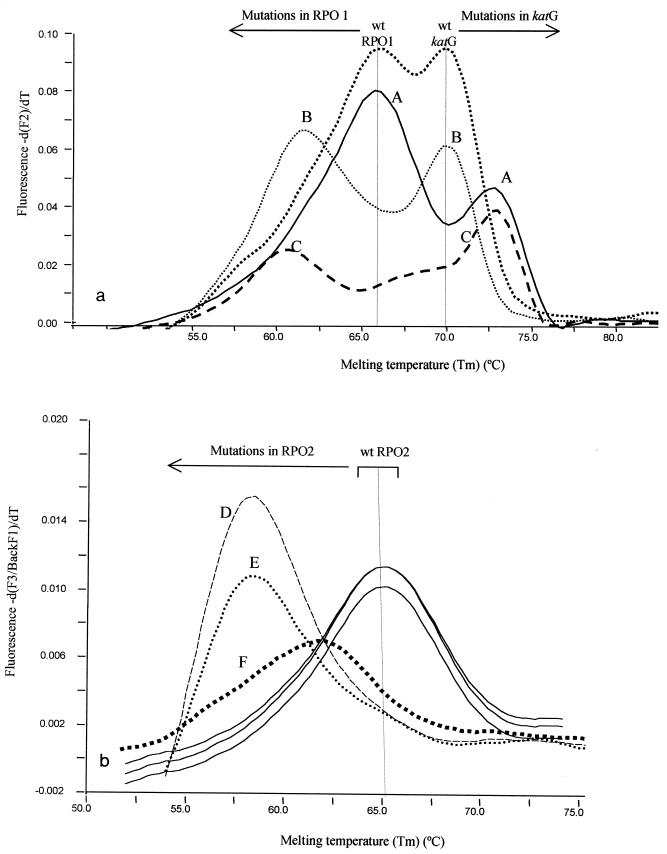

For all susceptible strains Tms were within the range obtained for the reference wt strains. All strains with a mutation in rpoB or katG were efficiently detected by the measurement of deviations (more than two times the standard deviation) in the Tms of the probes compared with the value obtained for the wt reference strain. These deviations indicated the existence of a mismatch (nucleotide substitution) between the probe and the template. Representative melting patterns are shown in Fig. 2a and b.

FIG. 2.

Representative experimental melting patterns for wt, RIFr, INHr, and MDR isolates, as measured in fluorimetric channels F2 (a) and F3 (b). The graphs show the result of taking the first negative derivative of the melting curve for the probes to obtain the point at which the slope changes (Tm). The Tm regions for wt and mutant isolates are indicated above the curves. (a) Measurement of the fluorescent signals from RPO1 and katG-specific probes. For the wt strain two peaks corresponding to each of the two probes are shown. A, representative result for an INHr isolate (the Tm of the katG-specific probes deviates with respect to that for the wt; the Tm of the RPO1 probes does not deviate with respect to that for the wt); B, representative result for an RIFr isolate with a mutation in RPO1 (the Tm for the RPO1 probes is deviated compared to the reference wt value; the Tm for the katG-specific probes is not deviated with respect to the wt value); C, representative result for an MDR isolate (simultaneous deviations both for the Tm of the RPO1 probes and for the Tm of the katG-specific probes). (b) Measurement of the fluorescent signal from the RPO2 probes. The results for three representative RIFr strains with mutations in RPO2 (peaks D, E, and F) are shown. In all of the strains, deviations in the Tm with respect to that for the wt were observed.

Mutations in codons 515 and 516 in rpoB were detected as a result of the reduction in the Tm of the RPO1 probes (Tm reductions, −2.48 to −8.39°C) (Table 1; Fig. 2a). Mutations in codons 526 and 531 in rpoB were also detected as a result of the reductions in the Tms of the RPO2 probes (Table 1; Fig. 2b) compared with the Tms obtained for the wt strain (Tm reductions, −0.66 to −6.92°C).

With regard to INHr, all mutations in codon 315 of the katG gene were detected by an increase in the Tm of the katG-specific probe (from 2.7 to 2.95°C; Table 1 and Fig. 2a) compared with the values obtained for the wt reference strain.

Four isolates (isolates 1, 2, 4, and 9) were MDR strains, and deviations in the Tms were consistently found simultaneously with the rpoB- and katG-specific probes (Table 1).

Thus, in our assay, the detection of deviations in the Tms of the probes higher than 0.5°C (more than two times the standard deviation) indicated the presence of a mutation. Full concordance was found between the results of our real-time PCR assay and the sequencing data. Our results were reproducible when the amount of DNA was varied (±1 log) or when crude cell extracts or purified DNA was assayed.

Blind analysis of a panel of resistant M. tuberculosis strains.

In order to test the validity of our assay under conditions resembling those found in clinical practice, a blind panel containing 15 strains was analyzed. The panel was composed of purified chromosomes from M. tuberculosis-susceptible and -resistant strains compiled at a national reference laboratory. Our aim was to use our assay to blind test strains for a wider selection of mutations associated with resistance.

The analysis (Table 2) indicated the presence of deviations in the Tms of the probes specific for rpoB, which suggests mismatches, for 11 strains. Deviations in the Tms were detected for five isolates (isolates C1, C2, C3, C4, and C6) with the RPO1 probes covering the 5′ half of rpoB (Tm reductions, −2.38 to −8.08°C; Table 2) and for the remaining six isolates (isolates C7 to C9 and C11 to C13) with the RPO2 probes, which were homologous to the 3′ half of rpoB (Tm reductions, −0.72 to −6.99°C; Table 2). Five of these isolates (isolates C1, C4, C6, C7, and C9) also had mutations in katG, as indicated by a reproducible increment in the Tm of the katG-specific probe, and the isolates therefore corresponded to MDR strains (Table 2). For the remaining four isolates (isolates C5, C10, C14, and C15), the Tms of the probes were within the range of the standard deviation for the wt reference strains, and therefore, they were not considered mutants. These real-time PCR results were compared with the sequencing data, and 100% concordance was obtained. Full agreement was obtained both according to the presence or the absence of mutations and according to the positions of the different mutations for RIFr. It is of special interest that the test succeeded in detecting a great variety of mutations for RIFr without varying the experimental conditions. Twelve different mutations at eight independent codons were detected, including the most frequent mutations in codons 526 and 531.

TABLE 2.

Real-time PCR data for resistant strains from the blind panel and sequencing data for all mutant strains

| Isolate no. | Gene and codon no. affected | Nucleotide substitution | Amino acid substitution | Deviation in Tm (°C) from that for wta

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPO1 probes (65.2°C) | RPO2 probes (65.1°C) | KATG probes (69.9°C) | ||||

| C1 | rpoB 511 | CTG→CCG, | Leu→Pro, | −5.13 | ||

| rpoB 516 | GAC→GGC | Asp→Gly | ||||

| katG 315 | AGC→ACC | Ser→Thr | +2.80 | |||

| C2 | rpoB 513 | CAA→CGA | Gln→Arg | −3.90 | ||

| C3 | rpoB 515-516 | Deletion TG-G | Asp-Asn→Met | −8.08 | ||

| C4 | rpoB 516-517 | Deletion GAC-CAG | −4.72 | |||

| katG 315 | AGC→ACC | Ser→Thr | +2.90 | |||

| C6 | rpoB 516 | GAC→GTC | Asp→Val | −2.38 | ||

| katG 315 | AGC→AAC | Ser→Asn | +2.90 | |||

| C7 | rpoB 526 | CAC→TGC | His→Cys | −4.08 | ||

| katG 315 | AGC→AAC | Ser→Asn | +2.90 | |||

| C8 | rpoB 526 | CAC→GAC | His→Asp | −2.88 | ||

| C9 | rpoB 526 | CAC→TAC | His→Tyr | −1.15 | ||

| katG 315 | AGC→ACC | Ser→Thr | +2.90 | |||

| C11 | rpoB 531 | TCG→TTG | Ser→Leu | −6.56 | ||

| C12 | rpoB 531 | TCG→TGG | Ser→Trp | −6.99 | ||

| C13 | rpoB 533 | CTG→CCG | Leu→Pro | −0.72 | ||

Deviations in the Tms for the probes (RPO1, RPO2, and KATG) compared with the reference value for the wt (given in parentheses).

DISCUSSION

Mutations encoding resistance to anti-TB drugs have been widely described, and there is a consensus on the most frequent mutations associated with INH resistance (14, 27). The same is true for RIF resistance (which results most frequently from changes in codons 526 and 531 in the rpoB gene), but different investigators have found miscellaneous additional genetic changes (in some cases, these changes are related to certain geographic settings) which lead to high degrees of variability in RIF resistance mutations (3, 9, 10, 17).

Different genotypic assays have been proposed for the detection of mutations associated with resistance to anti-TB drugs. DNA sequencing-based approaches are considered the reference assays, but they are too cumbersome. Other genotypic methods not based on DNA sequencing are restricted to the detection of only the most frequent mutations. The efficiencies of these methods can vary depending on the genetic compositions of the resistant M. tuberculosis strains in different geographic contexts. Furthermore, the rapidly increasing extent of movement of populations between different countries and continents means that the concepts of “major mutations” or “endemic mutations” may soon no longer be applicable.

The need for additional genotypic methodologies able to detect the larger numbers of mutations associated with resistance to anti-TB drugs has led us to develop a new genotypic system for rapid detection of resistance to RIF and INH. Our system not only can detect the most frequent mutations but can also search the entire rpoB resistance-determining core sequence and detect a wide variety of mutations in this region. Furthermore, the most prevalent mutations for INHr, which are associated with high-level resistance, are also detected in the same reaction tube. Our design takes advantage of rapid-cycle PCR and real-time fluorimetric detection in a LightCycler instrument. The detection of mutations with real-time PCR devices is usually based on fluorescent probes that are optimized to detect specific mutations. Formats that use molecular beacons and FRET probes are the ones most frequently applied to LightCycler instruments (22), although both beacons and FRET probes have limitations in terms of their ability to search simultaneously for different mutations. Beacons cover short DNA regions, and therefore, several probes would be required to fully explore a region such as the rpoB core. In the format with FRET probes, pairs of probes are used; one long probe acts as an anchor, and a short adjacent probe works as the sensor of a specific mutation that maps in the DNA sequence for which it is specific. This means that the number of mutations that can be detected in each reaction is limited. These standard formats are therefore unsuitable when it is necessary to search for several different mutations, as is the case for RIF resistance.

An assay design with a LightCycler instrument for the detection of mutations that encode RIF and INH resistance has recently been published (26), although it is limited in that it can predict only certain mutations in two different codons within the rpoB core. We propose an alternative way of adapting real-time approaches for evaluation of a genetic locus by searching for several different mutations. In our design we use each of the two paired FRET probes as sensors without using the standard anchor-sensor design. Mutations within the sequence covered by either of the two probes would lead to changes in the Tm of the probe, which in turn should increase the sensitivity of the assay.

Our new design has proved to be efficient in detecting 12 different mutations in eight different codons along the whole rpoB core region without modifying the experimental protocol. Thus, our approach provides an efficient means of searching for a wide variety of mutations other than the most frequent ones. This means that it is specially adapted to (i) the detection of emerging mutations associated with resistance within these loci and (ii) the search for resistance in different geographic settings, in which isolates could have different compositions in the loci that encode resistance.

Furthermore, we are now optimizing this real-time PCR to detect resistant strains in heterogeneous populations. Using in vitro mixtures between wt and mutant chromosomes as a template, we can detect the mutant subpopulation if it represents at least 20% of the population (data not shown).

It could be argued that this method is limited in terms of its clinical applications because (i) not all possible mutations that encode resistance to RIF have been tested for by our assay and (ii) some of the potentially detectable mutations may not be related to resistance. In this sense, we believe that the wide variety of mutations assayed (deletions and substitutions, which map in different relative positions within the regions studied) allows us to be confident about the efficiency of our method in detecting other minor mutations that were not represented in our collection. The misassignment of strains as resistant by the detection of mutations that do not code for resistance has been found to be unlikely (15) because in previous studies it has been reported that less than 2% of mutations are silent (24).

Our assay has proved to be reproducible without requiring standardization of the DNA concentration. In addition, only slight variations were found when highly purified DNA templates were compared with others from crude extracts. In all cases, the deviations of the Tms for the mutants were more than two times the standard deviation. Of 13 RIFr mutants (including those with the most prevalent mutations in codons 526 and 531), 11 had Tm deviations higher than 1°C and only 2 had Tm deviations below 1°C. These corresponded to two infrequent mutations (CCG at codon 533 and CTC at codon 526). In addition, it is worth noting that these two mutants (mutants C13 and 3), despite their slight Tm deviations, were not mistaken for the wt in our assay due to the large decrease in the fluorescence signal, which reflects mismatches in the annealing of the probe.

Ours is the first system able to simultaneously detect multiple mutations for RIF resistance and mutations for INH resistance in a single tube. It enables us to reduce costs and to simplify the analysis of MDR strains by saving chromosomal template and guaranteeing the standardization of all the different detection reactions. Thus, the presence of three independent sets of probes in the same reaction tube allows them to act as internal controls for the amplification and hybridization steps.

It could also be argued that our method is limited for the detection of INHr strains, as it is designed to detect mutations only in codon 315 in the katG gene. This mutation was found in nearly 50% of all resistant strains in our population of strains. The potential bias of having analyzed a major endemic clone is ruled out by the unique fingerprints obtained for all strains with this mutation (data not shown). The mutations in codon 315 in the katG gene were found to be clearly associated with high INH MICs, as commented upon by others (14, 27). Mutations in codon 315 of the katG gene are also found to be markers for MDR M. tuberculosis and are successfully transmitted within the population (27). In our opinion, all these aspects firmly justify our focus on this mutation and minimize the need to search for other mutations that encode resistance to INH.

Furthermore, there are limitations in the detection of some RIF-resistant strains. We were not able to detect those mutations that map outside the rpoB core. No mutations outside the core were detected in our population of a nationwide selection of resistant strains, and reports on the roles of these mutations are sporadic (10).

Some investigators have proposed that mutations in codon 531 (TTG and TGG) of rpoB are associated with a high level of resistance to RIF (3, 17). In addition, mutations in this codon are associated with resistance not only to RIF but also to all rifampins (28), making the detection of these mutations especially worthwhile. In our design, the positioning of the FRET dye close to codon 531 in the RPO2 set of probes makes these probes especially efficient in detecting mutations in this codon. Moreover, by paying attention to the melting profiles we were able to discriminate between different nucleotide substitutions at this position.

The role of rpoB mutations in the development of resistance to RIF has also been proposed for other bacteria, e.g., Helicobacter and Legionella (11, 16). Genotypic approaches, such as ours, which are not specialized in detecting a specific set of mutations could easily be applied to the analysis of the potential role of rpoB in the development of resistance in different groups of microorganisms.

In conclusion, genotypic systems for the detection of antibiotic resistance should no longer focus exclusively on the most frequent resistance mutations. Our design could be a model for new, rapid, and flexible genotypic methods of exploring antibiotic resistance by taking into consideration the genetic variability of resistance.

Additional studies are required to evaluate the flexibility of systems like ours in detecting resistance mutations in different geographic settings.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. S. Jimenez (Mycobacterium Reference Laboratory, Madrid, Spain) for providing the panel of resistant strains.

We are indebted to Thomas O'Boyle for revision of the English in the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anonymous. 1990. From the Centers for Disease Control. Outbreak of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis—Texas, California, and Pennsylvania. JAMA 264:173-174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanchard, J. S. 1996. Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65:215-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaves, F., M. Alonso-Sanz, M. J. Rebollo, J. C. Tercero, M. S. Jimenez, and A. R. Noriega. 2000. rpoB mutations as an epidemiologic marker in rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 4:765-770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edlin, B. R., J. I. Tokars, M. H. Grieco, J. T. Crawford, J. Williams, E. M. Sordillo, K. R. Ong, J. O. Kilburn, S. W. Dooley, K. G. Castro, et al. 1992. An outbreak of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among hospitalized patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 326:1514-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espinal, M. A., A. Laszlo, L. Simonsen, F. Boulahbal, S. J. Kim, A. Reniero, S. Hoffner, H. L. Rieder, N. Binkin, C. Dye, R. Williams, and M. C. Raviglione. 2001. Global trends in resistance to antituberculosis drugs. World Health Organization-International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease Working Group on Anti-Tuberculosis Drug Resistance Surveillance. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:1294-1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felmlee, T. A., Q. Liu, A. C. Whelen, D. Williams, S. S. Sommer, and D. H. Persing. 1995. Genotypic detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis rifampin resistance: comparison of single-strand conformation polymorphism and dideoxy fingerprinting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1617-1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischl, M. A., R. B. Uttamchandani, G. L. Daikos, R. B. Poblete, J. N. Moreno, R. R. Reyes, A. M. Boota, L. M. Thompson, T. J. Cleary, and S. Lai. 1992. An outbreak of tuberculosis caused by multiple-drug-resistant tubercle bacilli among patients with HIV infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 117:177-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gamboa, F., P. J. Cardona, J. M. Manterola, J. Lonca, L. Matas, E. Padilla, J. R. Manzano, and V. Ausina. 1998. Evaluation of a commercial probe assay for detection of rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis directly from respiratory and nonrespiratory clinical samples. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 17:189-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia, L., M. Alonso-Sanz, M. J. Rebollo, J. C. Tercero, and F. Chaves. 1813. Mutations in the rpoB gene of rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Spain and their rapid detection by PCR-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1813-1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heep, M., B. Brandstatter, U. Rieger, N. Lehn, E. Richter, S. Rusch-Gerdes, and S. Niemann. 2001. Frequency of rpoB mutations inside and outside the cluster I region in rifampin-resistant clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:107-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heep, M., U. Rieger, D. Beck, and N. Lehn. 2000. Mutations in the beginning of the rpoB gene can induce resistance to rifamycins in both Helicobacter pylori and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1075-1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heymann, S. J., T. F. Brewer, M. E. Wilson, and H. V. Fineberg. 1999. The need for global action against multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. JAMA 281:2138-2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiepiela, P., K. S. Bishop, A. N. Smith, L. Roux, and D. F. York. 2000. Genomic mutations in the katG, inhA and aphC genes are useful for the prediction of isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Kwazulu Natal, South Africa. Tuber. Lung Dis. 80:47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marttila, H. J., H. Soini, E. Eerola, E. Vyshnevskaya, B. I. Vyshnevskiy, T. F. Otten, A. V. Vasilyef, and M. K. Viljanen. 1998. A Ser315Thr substitution in KatG is predominant in genetically heterogeneous multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates originating from the St. Petersburg area in Russia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2443-2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musser, J. M. 1995. Antimicrobial agent resistance in mycobacteria: molecular genetic insights. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:496-514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nielsen, K., P. Hindersson, N. Hoiby, and J. M. Bangsborg. 2000. Sequencing of the rpoB gene in Legionella pneumophila and characterization of mutations associated with rifampin resistance in the Legionellaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2679-2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohno, H., H. Koga, T. Kuroita, K. Tomono, K. Ogawa, K. Yanagihara, Y. Yamamoto, J. Miyamoto, T. Tashiro, and S. Kohno. 1997. Rapid prediction of rifampin susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 155:2057-2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pablos-Mendez, A., M. C. Raviglione, A. Laszlo, N. Binkin, H. L. Rieder, F. Bustreo, D. L. Cohn, C. S. Lambregts-van Weezenbeek, S. J. Kim, P. Chaulet, and P. Nunn. 1998. Global surveillance for antituberculosis-drug resistance, 1994-1997. World Health Organization-International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease Working Group on Anti-Tuberculosis Drug Resistance Surveillance. N. Engl. J. Med. 338:1641-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rattan, A., A. Kalia, and N. Ahmad. 1998. Multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis: molecular perspectives. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 4:195-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reichman, L. B. 1996. Multidrug resistance in the world: the present situation. Chemotherapy (Basel) 42(Suppl. 3):2-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Scarpellini, P., S. Braglia, P. Carrera, M. Cedri, P. Cichero, A. Colombo, R. Crucianelli, A. Gori, M. Ferrari, and A. Lazzarin. 1999. Detection of rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by double gradient-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2550-2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stefan Meuer, C. W., and K.-I. Nakagawara (ed.). 2001. Rapid cycle real-time PCR: methods and applications. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 23.Telenti, A., N. Honore, C. Bernasconi, J. March, A. Ortega, B. Heym, H. E. Takiff, and S. T. Cole. 1997. Genotypic assessment of isoniazid and rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a blind study at reference laboratory level. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:719-723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Telenti, A., P. Imboden, F. Marchesi, D. Lowrie, S. Cole, M. J. Colston, L. Matter, K. Schopfer, and T. Bodmer. 1993. Detection of rifampicin-resistance mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lancet 341:647-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tenover, F. C., J. T. Crawford, R. E. Huebner, L. J. Geiter, C. R. Horsburgh, Jr., and R. C. Good. 1993. The resurgence of tuberculosis: is your laboratory ready? J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:767-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torres, M. J., A. Criado, J. C. Palomares, and J. Aznar. 2000. Sep. Use of real-time PCR and fluorimetry for rapid detection of rifampin and isoniazid resistance-associated mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3194-3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Soolingen, D., P. E. de Haas, H. R. van Doorn, E. Kuijper, H. Rinder, and M. W. Borgdorff. 2000. Mutations at amino acid position 315 of the katG gene are associated with high-level resistance to isoniazid, other drug resistance, and successful transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the Netherlands. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1788-1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams, D. L., L. Spring, L. Collins, L. P. Miller, L. B. Heifets, P. R. Gangadharam, and T. P. Gillis. 1998. Contribution of rpoB mutations to development of rifamycin cross-resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1853-1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]