Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) virus is transmitted to humans by Hyalomma ticks or by direct contact with the blood of infected humans or domestic animals. CCHF virus has been reported from the Near, Middle, and Far East (countries such as Iraq, Pakistan, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Oman, and China [1, 6-8, 11]) and from several African countries (4, 9). Besides, there are several reports on CCHF virus in the former Yugoslavia (5, 10), but CCHF virus strains from this area have not been characterized up to now. We describe here a case of CCHF in the year 2000 in Kosovo that preceeded an outbreak in the same region in 2001 (2).

On 23 May 2000, a farmer's wife (age, 17 years) living near Pristina, Kosovo, was bitten by a tick in the left femoral region while working in her garden. The tick was later identified as a member of the Hyalomma species at our institute. The disease started on 28 May with chills, myalgia, nausea, anorexia, vomiting, headache, and backache. The victim visited an outpatient clinic in Prizren, where broad-range antibiotic therapy was initiated because a septic infection could not be excluded. On 30 May, she developed massive hemorrhage with hematemesis (7 to 8 times per day), melena, hematuria, metrorrhagia, and petechia. She was hospitalized in a medical ward with no special isolation measures in a difficult clinical condition on 31 May, without palpable pulse or measurable blood pressure, with a body temperature of 39.7°C, and with severe hemorrhagic manifestations (petechiae, melena, hematemesis, and metrorrhagia). On 1 June, epistaxis and gingival bleeding were additionally observed and the high fever continued (40.1°C). The patient was fully orientated, without neurological symptoms, but prostrate. She complained of back pain and headache. Her eyes showed signs of hemorrhagic conjunctivitis and her gingiva and tongue were covered with hemorrhagic crusts, but the petechiae in the pectoral region were already in remission. Large ecchymoses appeared at the sites of venipuncture. The heart had a sinusal rhythm (90 beats/min) and weak tones, without noise. The abdomen was tender on palpation and the liver was palpable and slightly enlarged, but the spleen was not palpable. Diuresis was evident, with 1,500 ml of urine excreted per day. On 3 June she developed a polyuria (4,500 ml per day). The next day, the hemorrhagic diathesis had almost disappeared with only a light residual metrorrhagia. Blood pressure was 100/70 mmHg (pulse frequency, 60 beats/min). She was feeling better. Supportive therapy given to the patient during the course of the disease consisted of hydration and control of temperature. No blood transfusions were administered. No secondary cases have occurred in the hospital where the patient was treated.

Laboratory data.

On 31 May, the patient's platelet count was 30,000 platelets/ml, the bleeding time was 120 s, and the clotting time was 7 min 17 s (normal time, <6 min). On 1 and 2 June, the creatinine level was 480 μmol/liter (normal range, 50 to 89 μmol/liter), the platelet count was 116,000 platelets/μl, the aspartate amino transferase (AST) level was 547 U/liter, and the alanine amino transferase (ALT) level was 90 U/liter. On 12 June the AST level was 11 U/liter, the ALT level was 16 U/liter, and the creatinine level was 60 μmol/liter.

Virological data.

Serum samples of the patient were transported to the Bernhard-Nocht Institute without cooling and with several days of delay, due to the adverse situation of civil war in the Kosovo region. All manipulations with infectious material were performed in our biosafety level 4 facilities. In the first serum sample drawn on day 3 of the illness, no antibodies to CCHF virus were detected by indirect immunofluorescence assay (IIFA), while a virus RNA concentration of 7.7 × 105 genome equivalents per ml was found by real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR in plasma (one-step RT-PCR with SybrGreen detection of PCR-products [our unpublished data]). On 12 June, the RT-PCR result was negative, but high titers of immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG antibodies against CCHF virus (1:320 and 1:1,280, respectively) were detected by IIFA.

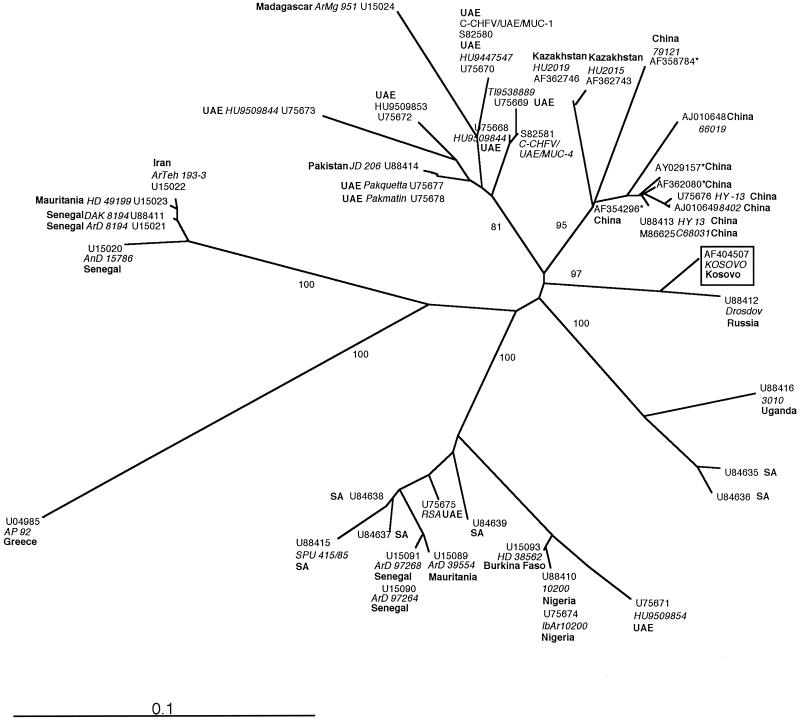

The amplified viral cDNA was sequenced and aligned with previously published data obtained from GenBank. Phylogenetic analysis including all 45 isolates available was performed with an S gene fragment commonly used for this purpose (Fig. 1). Seven major genetic groups could be distinguished with high bootstrap support. The Kosovo isolate and a strain isolated from the Black Sea region 33 years ago constituted a distinct new group. Taken together, our data indicate the presence of a distinct strain of CCHF virus circulating in the Kosovo-Black Sea region. Further investigations on its virulence and strain diversity will be of interest, as new cases are likely to emerge from this region.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of 46 partial sequences (219 bp) of the S segment of CCHF virus. The sequences were aligned and analyzed with the Phylip 3.57 software package (J. Felsenstein, University of Washington), using the neighbour-joining and maximum-likelihood (results not shown) algorithms. Both methods identified the same seven major genetic groups. The bootstrap values (percentages of 100 replicates) for each group are depicted at the respective branches. The geographic origin (boldface type), the GenBank accession number, and the additional strain denomination, if available (in italics) are given at the terminal branches for each isolate. Strains from the Middle and Far East and from different African regions cluster in clearly separated groups. Higher phylogenetic diversity among strains from the United Arabian Emirates (UAE) is attributable to importation of CCHF virus-infected livestock and ticks from African and Middle Eastern countries (6). SA, South Africa.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The Kosovo isolate sequence has been submitted to GenBank under accession no. AF404507.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altaf, A., S. Luby, A. J. Ahmed, N. Zaidi, A. J. Khan, S. Mirza, J. McCormick, and S. Fisher-Hoch. 1998. Outbreak of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in Quetta, Pakistan: contact tracing and risk assessment. Trop. Med. Int. Health 3:878-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. 2001. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) in Kosovo-update 5. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 3.Butenko, A. M., E. A. Tkachenko, M. P. Chumakov, et al. 1968. Isolation and study of Astrkhan strain (Drozdov) of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus and results of serodiagnosis of the infection. In Proceedings of the 15th Meeting of Institute of Poliomyelitis and Viral Encephalitis, Moscow, Soviet Union.

- 4.Chapman, L. E., M. L. Wilson, D. B. Hall, B. LeGuenno, E. A. Dykstra, K. Ba, and S. P. Fisher-Hoch. 1991. Risk factors for Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in rural northern Senegal. J. Infect. Dis. 164:686-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gligic, A., L. Stamatovic, R. Stojanovic, M. Obradovic, and R. Boskovic. 1977. [The first isolation of the Crimean hemorraghic fever virus in Yugoslavia]. Vojnosanit Pregl 34:318-321. (In Russian.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez, L. L., G. O. Maupin, T. G. Ksiazek, P. E. Rollin, A. S. Khan, T. F. Schwarz, R. S. Lofts, J. F. Smith, A. M. Noor, C. J. Peters, and S. T. Nichol. 1997. Molecular investigation of a multisource outbreak of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in the United Arab Emirates. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 57:512-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwarz, T. F., H. Nitschko, G. Jager, H. Nsanze, M. Longson, R. N. Pugh, and A. K. Abraham. 1995. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in Oman. Lancet 346:1230.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scrimgeour, E. M., A. Zaki, F. R. Mehta, A. K. Abraham, S. Al-Busaidy, H. El-Khatim, S. F. Al-Rawas, A. M. Kamal, and A. J. Mohammed. 1996. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in Oman. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 90:290-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swanepoel, R., J. K. Struthers, A. J. Shepherd, G. M. McGillivray, M. J. Nel, and P. G. Jupp. 1983. Crimean-congo hemorrhagic fever in South Africa. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 32:1407-1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vesenjak-Hirjan, J., V. Punda-Polic, and M. Dobe. 1991. Geographical distribution of arboviruses in Yugoslavia. J. Hyg. Epidemiol. Microbiol. Immunol. 35:129-140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yen, Y. C., L. X. Kong, L. Lee, Y. Q. Zhang, F. Li, B. J. Cai, and S. Y. Gao. 1985. Characteristics of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (Xinjiang strain) in China. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 34:1179-1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]