Abstract

The increasing legalization and decriminalization of cannabis for therapeutic and recreational purposes in various regions have influenced public perceptions and attitudes toward cannabidiol (CBD)-containing products, including their use during pregnancy. However, there is a knowledge gap regarding the effect of CBD on fetal development, and the mechanisms by which CBD induces developmental deficits have not been well studied. In this study, we investigated whether the teratogenic effects of CBD on developing zebrafish are mediated through Sonic hedgehog signaling (Shh), a critical pathway in development. Embryonic exposure to CBD reduced hatching and survival rates and suppressed Shh pathway activity, leading to decreased ptch2 expression—a regulatory receptor expressed in response to Shh signaling. Larval swimming activity was impaired by CBD exposure. However, coexposure to CBD and a synthetic Shh pathway activator significantly improved developmental outcomes, including decreased mortality, increased hatching rates, elevated ptch2 expression, and increased locomotor activity. These findings underscore the developmental risks associated with CBD use during pregnancy and highlight the involvement of the Shh signaling pathway in driving these effects. The results of this study can inform regulations for cannabis use during pregnancy and emphasize the need to develop therapeutic guidelines for the safe use of CBD-based treatments.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-99194-3.

Keywords: Cannabidiol, Gastrulation period, Sonic hedgehog signaling, Early development, Zebrafish

Subject terms: Developmental biology, Developmental neurogenesis

Introduction

The recreational use of cannabis has been legalized or decriminalized in several countries, including Canada, the Netherlands, Mexico, Thailand, and some states in the USA and Australia1,2. Therapeutic cannabis is also legal in many regions, including North America and Europe3. In the US, shifts in public policy around recreational and medical cannabis use have increased the social acceptability of cannabis use and increased the cannabis consumption rate among adults4. Similarly, the prevalence of cannabis use has increased in Canada post legalization5,6.

The increased likelihood of cannabis use on a global scale has raised concerns about cannabis-associated health risks in vulnerable users, including pregnant women. For example, a recent study in Canada indicated that 5% of pregnant women used cannabis to treat pregnancy-related issues such as anxiety, nausea, and sleep disorders7. In France, cannabis is the most commonly used illicit drug during pregnancy, with 4% of pregnant women reporting frequent monthly use in 20178. A cross-sectional study in the USA revealed a strong association between cannabis legalization and maternal (preconception, prenatal, and postpartum) cannabis consumption9. In humans, prenatal cannabis exposure is significantly associated with low gestational and birth weights in infants10 and may have long-term effects on the central nervous system (CNS) and cognitive function. Children who were prenatally exposed to cannabis experienced disturbances in sleep, low scores on IQ and memory tests, and attention deficits11. Moreover, more aggressive and oppositional defiant behaviors are observed in children who are prenatally exposed to cannabis than in those who are not exposed12.

The endocannabinoid system (ECS) plays a vital role in pregnancy10. The majority of ECS components, including endocannabinoids (e.g., anandamide (AEA)), endocannabinoid receptors (cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 (CB1R and CB2R)), and endocannabinoid metabolic enzymes, are expressed in reproductive tissues such as the ovaries and uterus, and their expression changes in response to fluctuating steroid hormones13. During early pregnancy, AEA plays a crucial role in the development of the embryo and its implantation in the uterus14. Moreover, dysregulated levels of AEA in the first-trimester placenta can also lead to spontaneous miscarriage15. Medical or recreational use of cannabis during pregnancy may alter ECS regulation, potentially impairing embryo development, inhibiting blastocyte implantation, compromising placentation, and leading to miscarriage16.

Cannabidiol (CBD) is the main nonpsychoactive constituent of cannabis and has therapeutic, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory properties. With the current worldwide trend of cannabis decriminalization and legalization, some pregnant women utilize CBD-containing products to combat a multitude of pregnancy symptoms17. Importantly, CBD can cross the placenta and has been shown to alter fetal development18. In utero exposure of mouse dams to 3 mg/kg CBD during days 5–18 of gestation led to reduced motor and discriminatory abilities in female pups19. In zebrafish, embryonic exposure to CBD during the critical developmental stage of gastrulation resulted in a reduced heart rate, altered motor neuron branching patterns in the trunk musculature, and a decreased escape response rate to sound stimuli20. Despite these findings, the mechanism by which CBD disrupts early development has not been well investigated.

One potential pathway that might be impacted following perturbation of the ECS is the sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling pathway. In fact, recent studies have indicated that there is crosstalk between the ECS and the Shh signaling pathway that regulates neural development and function21,22. The Shh pathway is activated by the Hedgehog (Hh) ligand. When Hh binds to the Patched (Ptch) receptor, it prevents Ptch-mediated suppression of a transmembrane protein named Smoothened (Smo). Free Smo, in turn, activates a signaling cascade in primary cilia by inhibiting adenylyl cyclase (AC). This ultimately leads to the transcription of Shh target genes, which are required for cell proliferation and early development23. Previously, we showed that in developing zebrafish, perturbation of the ECS through the inhibition of catabolic enzymes impaired swimming performance; however, exposure to a Smo agonist improved swimming distance22. Studies suggest that exposure to cannabinoids dysregulates Shh signaling by inhibiting Smo and leads to birth deficits in zebrafish and mice23,24. Stimulation of CB1Rs by cannabinoid exposure in mice led to the formation of novel CB1R-Smo heteromers that inhibit Shh signaling, and exposure to a CB1R antagonist or Hh mRNA reduced cannabinoid-induced birth deficits24. In genetically sensitized mice harboring a subthreshold deficit in the Shh pathway, however, the inhibition of the Shh pathway by in utero exposure to phytocannabinoids (Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)) was independent of CB1Rs25. These findings suggest that cannabinoids may mediate their effects on neurodevelopment through dysregulation of the Shh signaling pathway. The exact mechanism by which cannabinoids inhibit Shh signaling requires further investigation. CBD can also act as a negative regulator of Shh signaling; nevertheless, its mechanism of inhibition of the Shh pathway remains elusive25. In the present study, we investigated whether the teratogenic effects of CBD on developing zebrafish are mediated through dysregulation of the Shh signaling pathway.

Results

Effect of CBD on zebrafish survival and hatching rates is mediated through the sonic hedgehog pathway

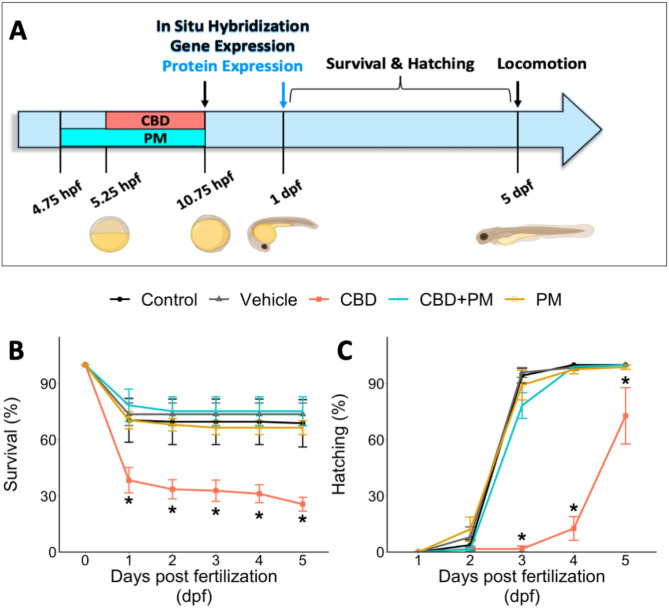

Our previous findings revealed that embryonic exposure to 3 mg/L CBD adversely affects anatomical parameters, including survival and hatching rates20. In this study, we co-exposed embryos to CBD and purmorphamine (PM), a synthetic activator of the Shh signaling pathway, to explore whether the adverse effects of CBD could be mitigated. We measured the survival and hatching rates of developing zebrafish (1–5 days post fertilization (dpf) after exposure to CBD and CBD + PM (a specific agonist of the Smo receptor)) during gastrulation (Fig. 1A). Our results indicated that the different treatments significantly affected zebrafish survival (χ2 (4) = 31.827, p < 0.001; n = 125; Fig. 1B) and hatching (χ2 (4) = 13.797, p = 0.007; n = 125; Fig. 1C) rates. Compared with vehicle treatment, exposure to CBD during gastrulation resulted in a significant reduction in both survival and hatching rates (p < 0.001 and p = 0.011, respectively). However, compared with CBD alone, coexposure to 20 µM PM and CBD significantly increased both survival and hatching rates in developing zebrafish (p < 0.001 and p = 0.041, respectively; Fig. 1B, C). At 5 dpf, the survival rates in the CBD and CBD + PM groups were 26 ± 4% and 75 ± 8% (mean ± SEM), respectively. Higher hatching rates were evident starting at 3 dpf in the CBD + PM treatment group (78.3 ± 6.9%) than in the CBD-treated group (1.7 ± 1.6%). Exposure to PM alone had no significant effect on the survival or hatching rates of developing zebrafish (Fig. 1B, C).

Fig. 1.

Effect of cannabidiol (CBD) on developing zebrafish. (A) Experimental outline demonstrating the exposure paradigm used to investigate whether the sonic hedgehog (Shh) pathway plays a role in CBD-induced effects on developing zebrafish. The embryos were exposed to purmorphamine (PM) or its vehicle, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), at 4.75 hpf for 30 min prior to gastrulation. During gastrulation, embryos were coexposed to CBD or the CBD vehicle, methanol (MeOH). The treated embryos were preserved at 10.75 hpf and 1 dpf to analyze the ptch2 expression pattern via in situ hybridization and qPCR. The expression of ptch2 among the treatment groups was also examined at 1 dpf via confocal microscopy in the transgenic zebrafish ptch2: Kaede line. All treatment groups were monitored daily from 1 to 5 dpf to assess hatching and survival rates. At 5 dpf, the locomotor activity of the embryos was also assessed (zebrafish illustrations were generated using BioRender.com). (B,C) Line graphs showing the survival and hatching rates of developing zebrafish exposed to different treatments: control, vehicle (0.2% DMSO + 0.3 MeOH), 3 mg/L CBD, 20 µM PM, and CBD + PM (n = 125). Asterisks indicate treatment groups that are significantly different from each other (Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test with Bonferroni correction, adjusted alpha ≤ 0.025). The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Exposure to CBD during gastrulation can dysregulate the early transcript expression of ptch2 in the sonic hedgehog pathway

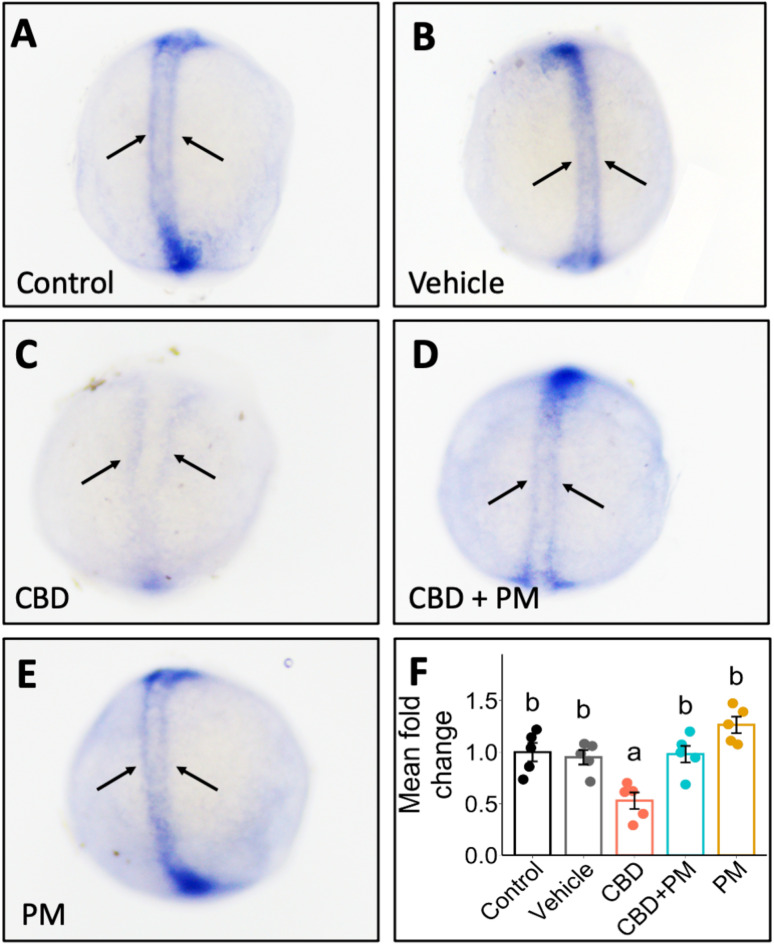

To determine whether CBD exposure during gastrulation can alter the mRNA expression of ptch2 (patched 2), the key receptor in the Shh pathway that regulates the activity of Smo, we performed in situ hybridization using a probe targeting ptch2. The expression of ptch2 is upregulated in response to active Shh signaling and acts as a feedback mechanism to modulate pathway activity.

Our findings revealed that the embryos assessed at the end of gastrulation presented lower ptch2 transcript expression in the CBD-exposed fish than in the vehicle- and control-treated fish (Fig. 2A–C). The expression of ptch2 within adaxial cells, which are precursors to slow muscles, was notably disorganized in CBD-treated embryos. Typically, ptch2 expression resembles two parallel tracts along the neural plate, as demonstrated by the vehicle and control treatments (Fig. 2A,B). However, in CBD-exposed embryos, the pattern was disrupted, resulting in large gaps between the tracts (Fig. 2C). Coexposure to CBD and PM prevented this disorganization, restoring the normal ptch2 expression pattern in 10.75 hpf embryos (Fig. 2D). The ptch2 expression of the fish exposed to CBD + PM or PM alone was similar to that of the control and vehicle-treated fish (Fig. 2D,E).

Fig. 2.

Exposure to CBD during gastrulation altered the expression pattern of ptch2 in 10.75 hpf embryos, ascertained via in situ hybridization, and PM rescued the CBD-induced effects. Zebrafish embryos were treated with (A) embryo medium (control), (B) 0.3% methanol (MeOH) or 0.2% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a vehicle, (C) 3 mg/L CBD, D) 3 mg/L CBD + 20 µM PM, or E) 20 µM PM during gastrulation (5.25–10.75 hpf), and at the end of gastrulation, in situ hybridization was performed to probe for ptch2 (n = 10–20). The arrows indicate adaxial cell organization in representative ptch2 in situ hybridization images of different treatments. (F) Bar graph showing the transcript abundance of ptch2 in embryos, via qPCR, collected at 10.75 hpf after being exposed to CBD, CBD + PM, PM, MeOH + DMSO, or the control during gastrulation (n = 5). Different lower-case letters indicate significant differences (one-way ANOVA was performed followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, p ≤ 0.05, error bars: ± SEM).

Results of the qPCR analysis further confirmed that transcript abundance of ptch2 was significantly affected by treatments (F (4, 20) = 11.160, p < 0.001; n = 5; Fig. 2F). The transcript abundance of ptch2 in the CBD-exposed fish was significantly downregulated, showing a 1.8-fold reduction relative to that in the vehicle-treated embryos at 10.75 hpf (p = 0.009; Fig. 2F). In contrast, there was no significant difference in the ptch2 transcript levels between vehicle- and CBD + PM-treated fish (p = 0.998; Fig. 2F).

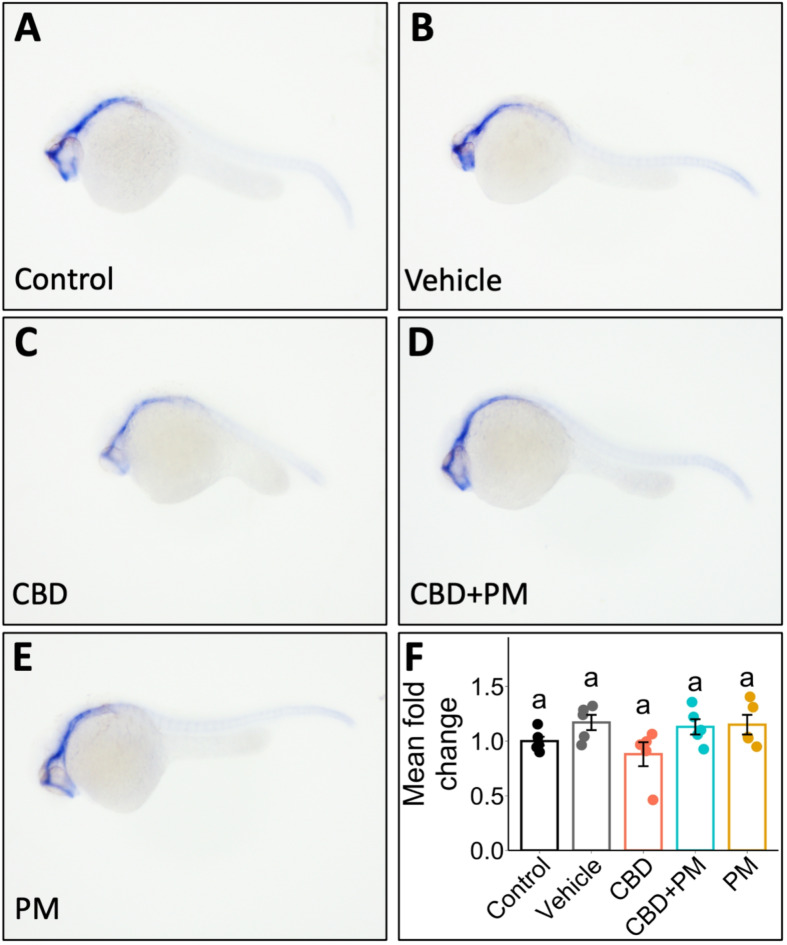

To assess whether the effect of CBD on the transcript abundance of ptch2 persisted over time, we examined ptch2 mRNA expression at 1 dpf in the exposed fish. The in situ hybridization results revealed a reduction in ptch2 expression in CBD-treated embryos (Fig. 3A–E). However, qPCR analysis indicated that despite this apparent trend towards lower values, the transcript abundance of ptch2 at 1 dpf was not significantly affected by the treatments (F (4, 20) = 2.386, p = 0.086; n = 5; Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

The expression of ptch2 in 1 dpf embryos, via in situ hybridization, was affected following CBD exposure during gastrulation. Zebrafish embryos were treated with (A) embryo medium (control), (B) 0.3% methanol (MeOH) and 0.2% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as vehicle, (C) 3 mg/L CBD, (D) 3 mg/L CBD + 20 µM PM, or (E) 20 µM PM during gastrulation (5.25–10.75 hpf). At the end of gastrulation, the embryos were transferred to clean embryo media, and in situ hybridization was performed to probe for ptch2 at 1 dpf (n = 10–20). (F) Bar graph showing the transcript abundance of ptch2 in embryos, via qPCR, collected at 1 dpf after being exposed to CBD, CBD + PM, PM, MeOH + DMSO, or the control during gastrulation (n = 5). Different lower-case letters indicate significant differences (one-way ANOVA was performed followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, p ≤ 0.05, error bars: ± SEM).

Expression of ptch2 was altered in response to CBD exposure during gastrulation in live embryos

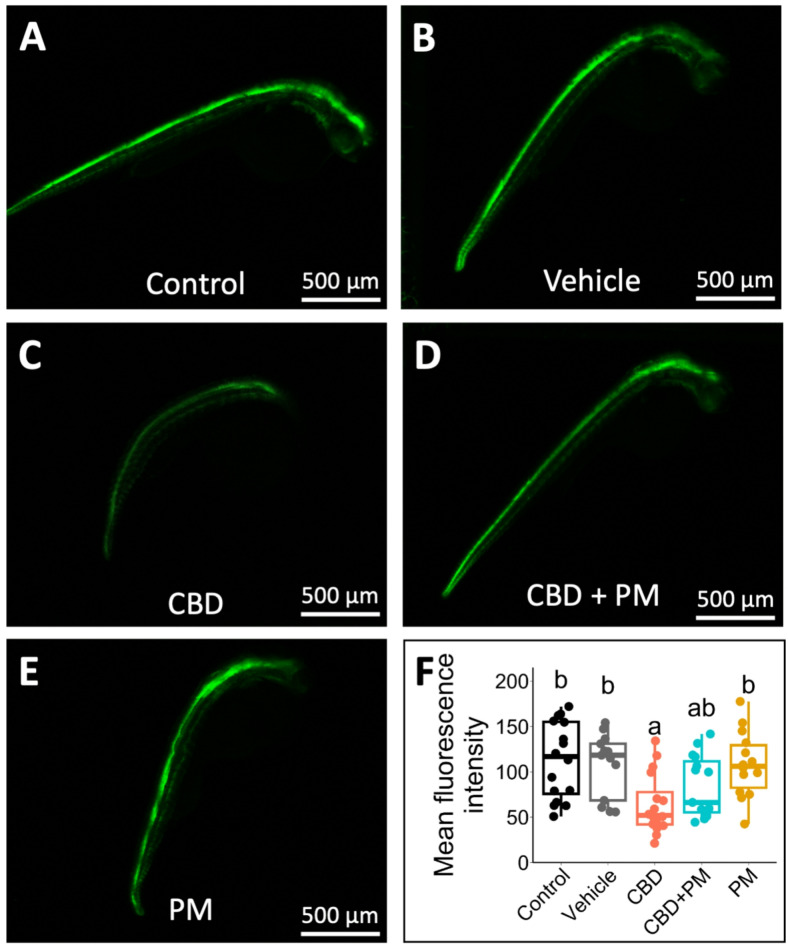

To further validate the changes observed in the ptch2 transcript levels in the CBD-treated fish, we measured ptch2 expression in live ptch2:Kaede transgenic embryos26 via confocal microscopy at 1 dpf. The expression of ptch2 was too low to be detected by confocal microscopy at 10.75 h, which limited our quantification to 1 dpf embryos. In this transgenic line, the Kaede fluorescent protein is engineered into the BAC containing the ptch2 (formerly Ptch1) genome region, which includes upstream and downstream regulatory sequences26. Its expression closely correlates with endogenous ptch2 expression and is responsive to Shh signaling27. Surprisingly, the results revealed that expression ptch2, measured as the mean fluorescence intensity of confocal images, was affected by the treatments (χ2 (4) = 18.17, p = 0.001; n = 13–16; Fig. 4F). The embryos treated with CBD during gastrulation showed decreased ptch2 expression relative to the control (p = 0.002) and vehicle (p = 0.009) treatments at 1 dpf (Fig. 4A–C,F). The mean fluorescence intensities of the confocal images, which indicate Kaede expression, were 64 ± 8, 107 ± 10, and 113 ± 11 in the CBD, vehicle, and control treatment groups, respectively. Therefore, exposure to CBD reduced the activity of the Shh signaling pathway and resulted in reduced expression of ptch2, which is induced by Shh signaling. Compared with CBD treatment alone, coexposure to CBD + PM led to a small increase in the expression of ptch2 (84 ± 9), but this increase was not significant (p = 0.759). Moreover, no significant difference was observed between the CBD + PM treatment group and the control or vehicle groups. These findings from live embryos suggest that 20 µM PM was able to increase ptch2 expression to a certain degree in CBD-exposed zebrafish, a change that may be biologically significant.

Fig. 4.

The expression of ptch2 in transgenic ptch2: Kaede embryos (1 dpf) was affected by CBD exposure during gastrulation. Confocal microscopy images of 1 dpf zebrafish embryos demonstrating how exposure to (A) embryo medium (control, n = 16), (B) 0.3% methanol (MeOH) or 0.2% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a vehicle (n = 13), (C) 3 mg/L CBD (n = 16), (D) 3 mg/L CBD + 20 µM PM (n = 15), or (E) 20 µM PM (n = 14) during gastrulation alters the expression of ptch2. Images were captured at 40X as maximum intensity z-stack compilations. (F) Box plot showing the fluorescence intensity measured from confocal images as an indicator of ptch2 expression after different treatments. The horizontal line within the boxplot represents the median value and is surrounded by the interquartile range. The error bars represent the maximum and minimum values. Different lower-case letters indicate significant differences among treatments (Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test with Bonferroni correction, adjusted alpha ≤ 0.025).

Exposure to CBD during gastrulation affects free swimming activity in zebrafish larvae

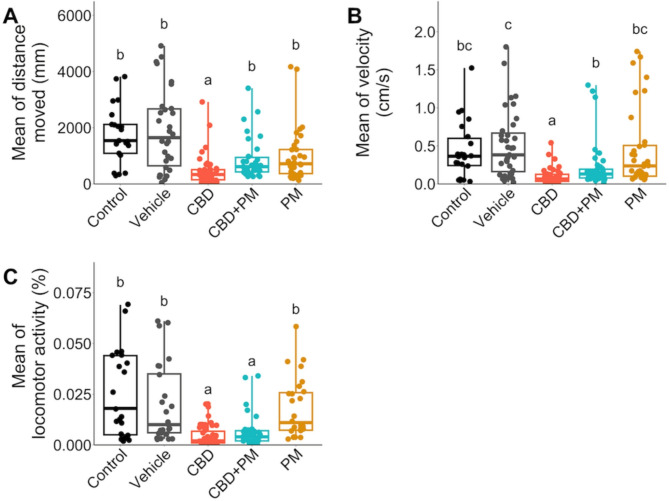

Given the observed CBD-induced disorganization of ptch2 expression within adaxial cells (Fig. 2C), which play a role in muscle formation and patterning, we further investigated whether fish locomotion was affected by CBD. To obtain a comprehensive overview of free-swimming behavior in zebrafish larvae that were exposed to CBD during gastrulation, we analyzed three locomotion parameters in the 5 dpf larvae: total distance traveled (mm), average speed (cm/s), and percentage of activity per hour (Fig. 5). Our findings indicated that all the measured behavioral parameters were significantly lower in the CBD-exposed larvae than in the vehicle-treated larvae (pdistance, velocity, activity < 0.001, adjusted alpha = 0.025; Fig. 5A–C). We also investigated whether coexposure to 20 µM PM and CBD could mitigate the locomotor deficits induced by CBD. Our results showed that the distance traveled and swimming velocity were the two metrics that showed a significant increase in the PM + CBD treated fish compared to those exposed to CBD alone (pdistance = 0.005, pvelocity = 0.024; Fig. 5A,B). There was no significant difference between control and CBD + PM treatments (pdistance = 0.037, pdistance = 0.105, adjusted alpha = 0.025). These findings suggest that the impact of CBD on fish locomotion is mediated, at least in part, through the Shh pathway, as the Smo agonist (PM) partially improved some locomotor parameters in CBD-exposed animals.

Fig. 5.

Exposure to CBD during gastrulation altered zebrafish larvae free swimming activity (locomotion) at 5 dpf. Zebrafish embryos were treated with embryo medium (control), 0.3% MeOH or 0.2% DMSO as a vehicle, 3 mg/L CBD, 3 mg/L CBD + 20 µM PM, or 20 µM PM during gastrulation, and fish locomotion was examined at 5 dpf (n = 21–54). Boxplots showing changes in (A) total distance moved (mm), (B) locomotion velocity during active periods (cm/s), and (C) locomotor activity (percent of pixel changes within an individual well over the period of 1 h). The horizontal line within the boxplot represents the median value and is surrounded by the interquartile range. The error bars represent the maximum and minimum values. Different lower-case letters indicate significant differences among treatments (Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test with Bonferroni correction, adjusted alpha ≤ 0.025).

Discussion

Cannabis use during pregnancy is an increasing concern, especially in regions where cannabis legalization and decriminalization have occurred or are in progress. Although CBD is widely recognized for its potential therapeutic benefits, its safety during pregnancy and its effects on fetal development remain critical areas of ongoing research. Interestingly, previous studies suggest that CBD may induce adverse effects on early development at lower concentrations than THC does28,29, and the LC50 (lethal concentration affecting 50% of the population) for CBD is significantly lower than that of THC in developing zebrafish28. In mouse whole embryo culture, exposure to CBD impaired cranial neural tube closure, potentially leading to the development of exencephaly30. Early exposure (1–10 hpf) of zebrafish embryos to 3 mg/L CBD resulted in decreased neural activity and locomotion29. Exposure to CB1R and CB2R antagonists partially improved the CBD-mediated reduction in locomotor activity in 5 dpf larvae, suggesting that early CBD exposure can disrupt the ECS29. These findings underscore the potential risks associated with CBD use during pregnancy, even at low concentrations, and highlight the importance of understanding the mechanisms underlying its effects on embryonic and fetal development.

In the present study, we aimed to uncover the potential mechanism behind developmental alterations caused by early exposure to CBD in zebrafish. Considering the potential interaction between the ECS and the Shh signaling pathway, we investigated whether one of the major phytocannabinoids, CBD, can modulate Shh signaling in a manner similar to that of endocannabinoids, which act as Smo antagonists31. Our findings provide new evidence that CBD-induced adverse effects on early development are mediated through Shh signaling. Our results indicate that upregulation of the Shh pathway with a pharmacological agonist of the Shh pathway (purmorphamine) inhibits CBD-induced teratogenicity in zebrafish. Shh is a critical pathway that plays a fundamental role in embryonic development and cell differentiation32. In developing zebrafish, knockout of Ptch receptors upregulated the Shh pathway and led to severe developmental deficits, including impaired pectoral fin and eye formation and somite differentiation33,34. The administration of cyclopamine (a pharmacological antagonist of Shh signaling) was able to partially rescue the phenotype in mutant zebrafish33. The Shh signaling pathway is tightly regulated in zebrafish, as any dysregulation can lead to severe adverse effects on early development34. In this study, we observed that early exposure to CBD reduced the expression of ptch2, the negative regulator of Shh, in zebrafish embryos. It is presumed that CBD acts as an inhibitor of the Shh pathway; as a compensatory response to the CBD-induced reduction in Shh signaling, the expression of ptch2 was downregulated through an autoregulatory loop to prevent further downregulation of Shh signaling. Moreover, exposure to the Smo agonist rescued reduced hatching, survival, and locomotion while maintaining ptch2 expression in developing zebrafish. These findings suggest that CBD exerts its developmental effects by downregulating Shh signaling during early development.

Our in situ hybridization results suggested a decrease in ptch2 transcript levels in CBD-treated embryos at 1 dpf (Fig. 3). This finding was further supported by the reduced ptch2 expression observed in the ptch2:Kaede reporter line treated with CBD at 1 dpf (Fig. 4). However, qPCR analysis did not reveal a significant change in the transcript abundance of ptch2 in 1 dpf fish. These discrepancies may be attributed to differences in the sensitivity of the techniques used. For the qPCR analysis, we used total RNA extracted from a pool of embryos. Since ptch2 is expressed primarily in specific regions of developing zebrafish, including midline structures such as the notochord and brain, the effect of CBD treatment may have been diluted in the pooled sample. Our findings highlight the advantage of using spatially specific methods for measuring transcripts, such as the ptch2:Kaede transgenic line, where Kaede functions as a real-time transcriptional reporter, alongside in situ hybridization. These methods enable the detection of subtle transcript changes that may not be captured by qPCR.

We also observed that exposure to CBD led to the disorganization of ptch2 expression within adaxial cells, and coexposure to PM inhibited this disorganization in CBD-exposed animals. In vertebrate embryos, muscle fibers can be broadly categorized into two main types: slow-twitch and fast-twitch muscle fibers35. Slow-twitch fibers are characterized by their ability to sustain contraction over longer periods of time, and during early development, they differentiate from their precursor cells, adaxial cells. It has been reported that Shh signaling is required for the development of slow muscle fibers36. The Shh protein plays a crucial role in the expression and maintenance of key transcription factors, such as MyoD and Myf5, which are essential for slow myogenesis37. Moreover, in vitro studies have indicated that the Shh protein regulates cell fate choice in primary cultures of embryonic zebrafish myoblasts38. While our study focused on ptch2 expression as an indicator of Shh pathway activity, future work involving direct analysis of muscle fiber organization will be necessary to confirm whether these molecular changes translate into structural or functional alterations in slow muscle development.

In the present study, early exposure to CBD also led to behavioral deficits in larval free-swimming activities. These locomotor impairments can potentially be associated with disrupted muscle development induced by CBD. Muscular function and coordination are essential for normal locomotor activities, and any disruptions in muscle development could lead to behavioral deficits in movement39. Nonetheless, further investigations are needed to determine whether early exposure to CBD interferes with slow muscle development in zebrafish. Motor neurons are responsible for transmitting signals from the nervous system to muscles, triggering muscle contractions. It is also plausible that exposure to CBD could impact neuromuscular function in developing zebrafish, leading to impaired muscle contraction and locomotion. The interactions between cannabis compounds, particularly THC and CBD, and the ECS may influence the nervous system’s control over muscle function and coordination. A previous study from our group revealed that brief exposure to THC, the main psychoactive constituent of cannabis, altered synaptic activity at neuromuscular junctions in 5 dpf zebrafish, leading to hyperactivity35. Moreover, early exposure to 3 mg/L CBD led to reduced motor neuron branching within the skeletal musculature of 2 dpf embryos20. The frequency of spontaneous synaptic activity was also reduced as a result of early exposure to CBD20. Since coexposure to a Smo agonist mitigated the effects of CBD on locomotor behavior, the impact of CBD on locomotion may be mediated, at least in part, through its modulation of the Shh signaling pathway. However, further research is necessary to fully elucidate the mechanisms underlying the observed locomotor disruptions during early development.

Survival and hatching rates were significantly reduced by early CBD exposure in developing zebrafish. The ability of PM to mitigate mortality suggests that CBD-induced downregulation of the Shh pathway contributes to developmental toxicity, which can be alleviated by enhancing Shh pathway activity. The inability of embryos to hatch from their chorions may stem from two potential factors: degradation of the chorion or impaired locomotor ability of the zebrafish. During development, the breakdown of the chorion (a protective membrane encasing the developing embryo) is facilitated by the secretion of specialized enzymes known as choriolysins into the perivitelline space40. Development delays may also postpone the secretion of choriolytic enzymes, as demonstrated by embryos raised at low temperatures41. Once the chorion is broken down, the embryo initiates spontaneous movements facilitating hatching. Therefore, the rescue of the CBD-induced reduction in hatching rate by PM may result from enhanced developmental progression, which stimulates the production and secretion of choriolysins and/or improved locomotor ability, enabling the fish to break free from the membrane.

In conclusion, in this study, we demonstrated that CBD has adverse effects on zebrafish development through the suppression of the Shh signaling pathway. Our findings indicate that activating the Shh pathway with an exogenous stimulator of Smo can rescue the CBD-induced effects on key developmental processes, including hatching, survival, and locomotion, in zebrafish. We observed that exposure to CBD reduced and disorganized ptch2 expression in adaxial cells at 10 hpf, and this reduced expression persisted at 1 dpf, as shown in the ptch2:Kaed line exposed to CBD. These findings suggest that the Shh pathway was downregulated due to CBD exposure, leading to a reduction in ptch2 expression as part of a feedback loop. The adverse effects of CBD on key developmental pathways, such as Shh signaling, raise concerns about the safety of CBD-containing products during pregnancy and highlight the urgent need to establish regulations for cannabis use during critical early developmental stages, including pregnancy and infancy. Further investigations are required to explore the downstream and upstream components of the Shh pathway to better understand the full scope of CBD-induced teratogenic effects in zebrafish.

Materials and methods

Test animals and experimental design

In the present study, we used the Tubingen longfin (TL) strain of wild-type zebrafish (Danio rerio) and a transgenic zebrafish strain (ptch2: Kaede line26 donated by Dr. Andrew Waskiewicz, University of Alberta). All animal housing and experimental procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines for the ethical treatment of animals and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Alberta (AUP #00000816). All researchers complied with the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines, and all methods are reported accordingly.

Adult fish were housed in the aquatic facility of the University of Alberta under a standard 14:10 h light:dark cycle at 28 °C. To breed, two females and one male were placed in breeding tanks the evening before egg collection. The fertilized eggs were collected the next morning, transferred to Petri dishes (Fisher Scientific, Canada) containing embryo medium (60 μg/mL saltwater solution, Instant Ocean, pH 7.5), and kept in a 28.5 °C incubator. The embryo medium was changed every 24 h, and dead embryos or larvae were removed. For in situ hybridization experiments, wild-type embryos (postgastrulation) were incubated in a 0.004% 1-phenyl-2-thiourea (PTU, Sigma Aldrich, Canada) solution in embryo medium to inhibit pigmentation.

To examine the involvement of the Shh pathway in CBD-induced effects on early development, embryos were coexposed to CBD and a known Smo agonist, purmorphamine (PM). Prior to exposure, the embryos were separated into groups of 25 and placed in 3.5 mm × 10 mm petri dishes with 4 mL of embryo medium. At 4.75 h postfertilization (hpf, 30 min prior to gastrulation), the embryos were incubated with PM (20 µM; Sigma‒Aldrich, Canada) or its vehicle dimethyl sulfoxide (0.2% DMSO; Sigma‒Aldrich, Canada) (Fig. 1A).

The embryos were preincubated in PM prior to gastrulation to allow activation of the Shh pathway before the administration of CBD. The embryos were subsequently exposed to both PM and CBD throughout the duration of gastrulation. After 30 min of preincubation, 3 mg/L CBD (Sigma‒Aldrich, Canada) or an equivalent amount of methanol (0.3% MeOH), the vehicle for CBD, was added to the appropriate dish at the beginning of gastrulation (5.25 hpf; Fig. 1A). An untreated control group was run simultaneously in the absence of all the test compounds, and the experimental treatments were as follows: control (untreated), vehicle (DMSO + MeOH), CBD, CBD + PM, and PM. Following the exposures, the embryos were returned to the incubator at 28.5 °C for the duration of gastrulation (5.25 hpf to 10.75 hpf). At 10.75 hpf, each plate was rinsed three times with egg mixture and then returned to the incubator to continue development. The wild-type embryo survival and hatching rates were recorded each morning from 1 to 5 dpf. Each treatment had 5 replicates, with 25 fish per replicate (total n = 125 fish per treatment).

The concentration of CBD used was selected in accordance with our previous experiments, which revealed that exposure to 3 mg/L CBD resulted in embryos with morphological abnormalities and a mortality rate of approximately 40% at 1 dpf, leaving enough embryos able to survive until 5 dpf for further testing20. The concentration of PM used was selected on the basis of previous literature42, and our preliminary study suggested that 20 µM PM does not induce adverse effects on developing zebrafish. The period of gastrulation was chosen because it represents a major early developmental event, where proper specification of the three tissue layers and establishment of the embryonic axis are necessary for the development of the whole organism. This timepoint has been shown to be particularly susceptible to teratogens, such as ethanol43,44. Additionally, gastrulation is the time period in which nervous system development is initiated, with the induction of the neural plate45. As such, disrupting this process may have consequences for early neurodevelopment.

Probe synthesis and in situ hybridization

The primer sequences for ptch2 were taken from Thisse and Thisse46 (Table 1). Total RNA from wild-type embryos was isolated via TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions at the end of gastrulation or 24 hpf. Using a Maxima H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher), complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed for 35 cycles via DreamTaq DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher). Next, 1 μg of the PCR product was used as a template for in vitro transcription (IVT). The resulting IVT product (1 μL) was examined via gel electrophoresis to confirm the integrity and yield of the probe transcript. One confirmed probe mixture (5 μL) was added to 995 μL (1:200) of hybridization media (HM, 50% formamide, 5X saline‒sodium citrate (SSC) buffer (20X stock: 3 M NaCl, 300 mM trisodium citrate, pH 7.0), 50 μg/mL heparin (Sigma‒Aldrich, Canada), 500 μg/mL Type II‒C ribonucleic acid from the torula yeast core (tRNA replacement; Sigma‒Aldrich, Canada), 0.1% Tween-20 (Fisher Scientific), and 0.092 M citric acid).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the primer set used in in situ hybridization analysis of zebrafish embryos.

| Target Transcript | zFIN ID | Sequence of primer (5′-3′) | Probe length | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ptch2 | ZDBGENE-98052644 |

F: TCCTGTGCTGTTTCTACAGG R: ATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGA ATGCGCAGAACAAGTTATAG |

740 | Thisse and Thisse46 |

For in situ hybridization analysis, wild-type embryos were collected at either 10.75 hpf or 1 dpf, fixed overnight in 4% PFA at 4 °C, and then probed for ptch2 following a modified protocol described elsewhere46. After fixation, the embryos (n = 10–20) were washed in 100% methanol and stored at -20 °C. The embryos were rehydrated in a series of ascending phosphate-buffered saline solutions with 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST, Sigma‒Aldrich, Canada): MeOH and were subsequently washed several times in PBST (5 × 5 min). The 1 dpf embryos were permeabilized in 10–20 μg/mL proteinase K (Sigma‒Aldrich, Canada), fixed, and washed in PBST47. The embryos were then prehybridized with HM at 65 °C for 1–5 h and then hybridized with 500 µL of probe in HM overnight. To examine background staining in the coloration reaction, a negative control in which embryos were incubated in HM in the absence of a probe was used47.

The following morning, the probe was removed and stored at − 20 °C. The samples were washed at 65 °C in a series of SCC washes at various stringencies to remove unbound probe. The samples were then transferred to a blocking solution (PBST, Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, 2 mg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich), and 2% Sheep Serum (Sigma-Aldrich)). Blocking solution was prepared fresh each time. This blocking step was performed for 1–3 h at room temperature to prevent non-specific binding. Subsequently, the embryos were transferred to a solution of 1:5000 anti-digoxygenin-AP Fab fragments (Millipore Sigma) antibody prepared in blocking solution at 4 °C overnight. After blocking, the embryos were gently transferred to PBST at room temperature to remove unbound antibody. The samples were subsequently rinsed (4 × 5 min) in coloration buffer (Tris–HCl, MgCl2, NaCl, and tween) and incubated in coloration buffer with NBT/BCIP (Millipore Sigma, Canada) for 2–4 h at room temperature. The samples were monitored under a dissecting microscope periodically until staining was observed. The embryos were rinsed in methanol following the coloration reaction, mounted in 100% glycerol and imaged under a dissecting microscope.

Reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis

To provide further support for the results of in situ hybridization, we compared the transcript abundances of ptch2 among different treatments at 10.75 hpf or 24 hpf. Wild-type embryos were collected at the end of the gastrulation period or 24 hpf, and a pool of 30–50 whole embryos was used as one replicate for RNA isolation (n = 5) via the TRIzol reagent. The total RNA purity and quantity were measured via a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For the qPCR analysis, 2 µg of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA via a Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The primer set for the target gene (ptch2) was designed via Primer Express software (version 3.0, Applied Biosystems). The characteristics of the primers used for the qPCR analysis are available in Table 2. The efficiency of the ptch2 primer was determined via a standard serial dilution series of cDNA. Melt curve analysis confirmed primer specificity, with only single PCR products detected.

Table 2.

Primers used for qPCR analysis of the target gene in zebrafish embryos.

| Target Transcript | Sequence of primer (5′-3′) | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| ptch2 |

F: GAGTGCTATTCCTGTGGTCATCCT R: ACGGCTGAACGAGTGTTCCT |

2 |

| 18 s |

F: TCGCTAGTTGGCATCGTTTATG R: CGGAGGTTCGAAGACGATCA |

2.07 |

| Beta-actin (actb) |

F: CTTGGGTATGGAATCTTGCG R: AGCATTTGCGGTGGACGAT |

1.95 |

The transcript abundance of the reference genes ACTB48 and 18S49 did not significantly vary among the samples. Each qPCR mixture, with a total volume of 10 μL, consisted of 5 μL of 2 × SYBR Green qPCR MasterMix (MBSU, University of Alberta), 2.5 μL of 3.2 μM primer, and 2.5 μL of cDNA (loaded in duplicate)48. The qPCRs were amplified and quantified via a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The thermal profile started with a preincubation phase at 95 °C for 2:00 min, followed by an amplification phase (15 s at 95 °C, 1:00 min at 60 °C) for 40 cycles. The abundance of ptch2 transcripts was quantified relative to the geometric means of reference gene transcripts according to the Pfaffl method of relative quantification50.

Confocal microscopy and expression of ptch2

We used the transgenic zebrafish ptch2: Kaede line to measure the expression of ptch2 after different treatments in 1 dpf embryos (n = 13–16 per treatment). In this study, we did not utilize the photoconvertible property of the Kaede protein, as our focus was solely on comparing ptch2 expression across treatments at 1 dpf. All 1 dpf embryos were dechorionated under a dissecting microscope (Leica MZ95), immobilized in 0.01% tricaine (ethyl 3-aminobenzoate methane sulfonate salt, Sigma Aldrich), and placed in an 8-chamber unit (1 fish per chamber, Lab-Tek, #1.5 German borosilicate cover glass system) for live imaging. Embryos from different treatment groups were imaged via a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM710, 40X). Images were compiled via Zeiss LSM710 Image Browser software and are presented as maximum intensity z-stack compilations. To measure ptch2 expression, confocal images were analyzed for mean fluorescence intensity via ImageJ photo analysis software (ImageJ2, version 2.9.0/1.53t).

Behavioral locomotor activity

To track the locomotor activity of 5 dpf-treated larvae (n = 21–54 per treatment), individual fish were placed in single wells of a 96-well plate (Corning Costar, Cell Culture-treated flat bottom microplate, Fisher Scientific) and acclimated to the recording environment for 60 min before locomotion recording. The plates were placed on a black light infrared source, and the movement of each individual larva was tracked for periods of 1 h via a Basler GenlCaM (Basler acA 1300-60) scanning camera with a 75 mm f2.8 C-mount lens provided by Noldus (Wageningen, Netherlands). EthoVision® XT-11.5 software (Noldus) was used to quantify the percentage of locomotor activity (percent of pixel changes within an individual well) over a period of 1 h, average velocity during active periods (mm/s), and total distance traveled (mm). To exclude any samples that were not detected by the software, all videos were reviewed before analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in R, version 4.251. The normality and homogeneity of variances of all the data were tested via the Shapiro–Wilk test and Bartlett test, respectively. To determine the effects of treatments on fish survival and hatching rates, a nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test with Bonferroni correction was used (the significance threshold was adjusted for multiple comparisons). To investigate the impact of treatments on the transcript abundance of ptch2 measured by qPCR, we performed a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. The effects of the various treatments on the expression of ptch2, measured by confocal microscopy, and locomotor activity in developing zebrafish were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test with Bonferroni correction.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the staff of the University of Alberta Aquatic Research facility for their diligent care of the fish used in this study. The authors would also like to extend their appreciation to the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) for their financial support of this study (Grant No. RGPIN-2016-04695 awarded to D. W. Ali).

Author contributions

P.R., H.S., and D.W.A. conceived and designed the research; P.R. and H.S. performed the experiments; P.R. and H.S. analyzed the data; P.R., H.S., and D.W.A. interpreted the results of the experiments; P.R. prepared the figures; P.R. drafted the manuscript; P.R., H.S., and D.W.A. edited and revised the manuscript; P.R., H.S., and D.W.A. approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

All raw data from this study are included in the supplementary materials.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wheeldon, J. & Heidt, J. Cannabis criminology: Inequality, coercion, and illusions of reform. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy29, 426–438 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lancione, S. et al. Non-medical cannabis in North America: An overview of regulatory approaches. Public Health178, 7–14 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abuhasira, R., Shbiro, L. & Landschaft, Y. Medical use of cannabis and cannabinoids containing products–regulations in Europe and North America. Eur. J. Intern. Med.49, 2–6 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammond, C. J., Chaney, A., Hendrickson, B. & Sharma, P. Cannabis use among US adolescents in the era of marijuana legalization: A review of changing use patterns, comorbidity, and health correlates. Int. Rev. Psychiatry32, 221–234 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imtiaz, S. et al. Cannabis legalization and cannabis use, daily cannabis use and cannabis-related problems among adults in Ontario, Canada (2001–2019). Drug Alcohol. Depend.244, 109765 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahji, A., Kaur, S., Devoe, D. & Patten, S. Trends in Canadian cannabis consumption over time: A two-step meta-analysis of Canadian household survey data. Can. J. Addict.13, 6–13 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manning, S. & Drover, A. Parental perceptions and patterns of cannabis use during pregnancy and breastfeeding at a Canadian tertiary obstetrics centre. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can.42, 681 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouquet, E. et al. Adverse events of recreational cannabis use during pregnancy reported to the French addictovigilance network between 2011 and 2020. Sci. Rep.12, 16509 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skelton, K. R., Hecht, A. A. & Benjamin-Neelon, S. E. Recreational cannabis legalization in the US and maternal use during the preconception, prenatal, and postpartum periods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health17, 909 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen, V. H. & Harley, K. G. Prenatal cannabis use and infant birth outcomes in the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. J. Pediatr.240, 87–93 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Genna, N. M., Willford, J. A. & Richardson, G. A. Long-term effects of prenatal cannabis exposure: Pathways to adolescent and adult outcomes. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav.214, 173358 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murnan, A. W. et al. Behavioral and cognitive differences in early childhood related to prenatal marijuana exposure. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol.77, 101348 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maia, J., Fonseca, B., Teixeira, N. & Correia-da-Silva, G. The fundamental role of the endocannabinoid system in endometrium and placenta: Implications in pathophysiological aspects of uterine and pregnancy disorders. Hum. Reprod. Update26, 586–602 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor, A. H., Ang, C., Bell, S. C. & Konje, J. C. The role of the endocannabinoid system in gametogenesis, implantation and early pregnancy. Hum. Reprod. Update13, 501–513 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trabucco, E. et al. Endocannabinoid system in first trimester placenta: low FAAH and high CB1 expression characterize spontaneous miscarriage. Placenta30, 516–522 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Correa, F., Wolfson, M. L., Valchi, P., Aisemberg, J. & Franchi, A. M. Endocannabinoid system and pregnancy. Reproduction152, R191–R200 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarrafpour, S. et al. Considerations and implications of cannabidiol use during pregnancy. Curr. Pain Headache Rep.24, 1–10 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Genna, N. M., Kennon-McGill, S., Goldschmidt, L., Richardson, G. A. & Chang, J. C. Factors associated with ever using cannabidiol in a cohort of younger pregnant people. Neurotoxicol. Teratol.96, 107162 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iezzi, D., Caceres-Rodriguez, A., Chavis, P. & Manzoni, O. J. In utero exposure to cannabidiol disrupts select early-life behaviors in a sex-specific manner. Transl. Psychiatry12, 501 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed, K. T., Amin, M. R., Shah, P. & Ali, D. W. Motor neuron development in zebrafish is altered by brief (5-hr) exposures to THC (∆ 9-tetrahydrocannabinol) or CBD (cannabidiol) during gastrulation. Sci. Rep.8, 10518 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boa-Amponsem, O., Zhang, C., Burton, D., Williams, K. P. & Cole, G. J. Ethanol and cannabinoids regulate zebrafish GABAergic neuron development and behavior in a Sonic Hedgehog and fibroblast growth factor-dependent mechanism. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res.44, 1366–1377 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khara, L. S. & Ali, D. W. The endocannabinoid systemʼs involvement in motor development relies on cannabinoid receptors, TRP channels, and Sonic Hedgehog signaling. Physiol. Rep.11, e15565 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovács, M. V., Charchat-Fichman, H., Landeira-Fernandez, J., Medina, A. E. & Krahe, T. E. Combined exposure to alcohol and cannabis during development: Mechanisms and outcomes. Alcohol110, 1–13 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fish, E. W. et al. Cannabinoids exacerbate alcohol teratogenesis by a CB1-hedgehog interaction. Sci. Rep.9, 1–16 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lo, H.-F., Hong, M., Szutorisz, H., Hurd, Y. L. & Krauss, R. S. Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol inhibits Hedgehog-dependent patterning during development. Development148, dev199585 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang, P., Xiong, F., Megason, S. G. & Schier, A. F. Attenuation of notch and hedgehog signaling is required for fate specification in the spinal cord. PLoS Genet.8, e1002762 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armstrong, B. E., Henner, A., Stewart, S. & Stankunas, K. Shh promotes direct interactions between epidermal cells and osteoblast progenitors to shape regenerated zebrafish bone. Development144, 1165–1176 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carty, D. R., Thornton, C., Gledhill, J. H. & Willett, K. L. Developmental effects of cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in zebrafish. Toxicol. Sci.162, 137–145 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanyo, R. et al. Medium-throughput zebrafish optogenetic platform identifies deficits in subsequent neural activity following brief early exposure to cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Sci. Rep.11, 11515 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gheasuddin, Y. & Galea, G. L. Cannabidiol impairs neural tube closure in mouse whole embryo culture. Birth Defects Res.114, 1186–1193 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khaliullina, H., Bilgin, M., Sampaio, J. L., Shevchenko, A. & Eaton, S. Endocannabinoids are conserved inhibitors of the Hedgehog pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.112, 3415–3420 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carballo, G. B., Honorato, J. R., de Lopes, G. P. F. & de Spohr, T. C. L. S. E. A highlight on Sonic hedgehog pathway. Cell Commun. Signal.16, 1–15 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koudijs, M. J., den Broeder, M. J., Groot, E. & van Eeden, F. J. Genetic analysis of the two zebrafish patched homologues identifies novel roles for the hedgehog signaling pathway. BMC Dev. Biol.8, 1–17 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koudijs, M. J. et al. The zebrafish mutants dre, uki, and lep encode negative regulators of the hedgehog signaling pathway. PLoS Genet.1, e19 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Razmara, P., Zaveri, D., Thannhauser, M. & Ali, D. W. Acute effect of Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol on neuromuscular transmission and locomotive behaviors in larval zebrafish. J. Neurophysiol.129, 833–842 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barresi, M. J., Stickney, H. L. & Devoto, S. H. The zebrafish slow-muscle-omitted gene product is required for Hedgehog signal transduction and the development of slow muscle identity. Development127, 2189–2199 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coutelle, O. et al. Hedgehog signalling is required for maintenance of myf5 and myoD expression and timely terminal differentiation in zebrafish adaxial myogenesis. Dev. Biol.236, 136–150 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norris, W., Neyt, C., Ingham, P. W. & Currie, P. D. Slow muscle induction by Hedgehog signalling in vitro. J. Cell Sci.113, 2695–2703 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dubińska-Magiera, M. et al. Zebrafish: A model for the study of toxicants affecting muscle development and function. Int. J. Mol. Sci.17, 1941 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De la Paz, J. F., Beiza, N., Paredes-Zúñiga, S., Hoare, M. S. & Allende, M. L. Triazole fungicides inhibit zebrafish hatching by blocking the secretory function of hatching gland cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci.18, 710 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carballo, C. et al. Genomic and phylogenetic analysis of choriolysins, and biological activity of hatching liquid in the flatfish Senegalese sole. PLoS ONE14, e0225666 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aanstad, P. et al. The extracellular domain of smoothened regulates ciliary localization and is required for high-level Hh signaling. Curr. Biol.19, 1034–1039 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ethanol induces embryonic malformations by competing for retinaldehyde dehydrogenase activity during vertebrate gastrulation | Disease Models & Mechanisms|The Company of Biologists. https://journals.biologists.com/dmm/article/2/5-6/295/2233/Ethanol-induces-embryonic-malformations-by. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Serrano, M., Han, M., Brinez, P. & Linask, K. K. Fetal alcohol syndrome: Cardiac birth defects in mice and prevention with folate. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.203(75), e7-75.e15 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kimmel, C. B., Ballard, W. W., Kimmel, S. R., Ullmann, B. & Schilling, T. F. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn.203, 253–310 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thisse, C. & Thisse, B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat. Protoc.3, 59–69 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Son, H.-W. & Ali, D. W. Endocannabinoid receptor expression in early zebrafish development. Dev. Neurosci.44, 142–152 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmed, K. T. et al. Expression and development of TARP γ-4 in embryonic zebrafish. Dev. Neurosci.44, 518–531 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Messina, A. et al. Neurons in the dorso-central division of zebrafish pallium respond to change in visual numerosity. Cereb. Cortex32, 418–428 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pfaffl, M. W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res.29, e45–e45 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.R Core, T. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2021).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All raw data from this study are included in the supplementary materials.