Abstract

Unpublished randomized controlled trial (RCT) frequency, correlates, and financial impact are not well understood. We sought to characterize the nonpublication of peer-reviewed manuscripts among interventional, therapeutic, multi-arm, phase 3 oncology RCTs. Trials were identified by searching ClinicalTrials.gov, while publications and abstracts were identified through PubMed and Google Scholar. Trial data were extracted from ClinicalTrials.gov and individual publications. Publication was defined as a peer-reviewed manuscript addressing the primary endpoint. Patient accrual cost was extrapolated from experimental data; investigators/sponsors were contacted to determine non-publication reasons. Six hundred eighty-four completed RCTs met inclusion criteria, which accrued 434,610 patients from 1994 to 2015; 638 were published (93.3%) and 46 were unpublished (6.7%). Among the unpublished trials, the time difference from primary endpoint maturity to data abstraction was a median of 6 years (interquartile range, 4 to 8 years). On multiple binary logistic regression analysis, factors associated with unpublished trials included lack of cooperative group sponsorship (odds ratio, 5.91, 95% CI, 1.35 to 25.97; P=.019) and supportive care investigation (odds ratio, 2.90; 95% CI, 1.13 to 7.41; P=.027). The estimated inflation-adjusted average cost of patient accrual for all unpublished trials was $113,937,849 (range, $41,136,883 to $320,201,063). Direct contact with sponsors/investigators led to a 50.0% response rate (n=23 of 46); manuscript in preparation and/or in submission (n=10 of 23) was the most commonly cited reason for nonpublication. In conclusion, approximately 1 in 15 clinical oncology RCTs are unpublished and this has a profound impact on the research enterprise. The cooperative group infrastructure may serve as a blueprint to reduce nonpublication.

Phase 3 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) set the standard for comparing disease interventions that can eventually guide therapy at an individual level and enhance health care value for society as a whole. Given the time and risk associated with patient participation in these trials, there is an ethical imperative to publish and disseminate the research results in keeping with the Declaration of Helsinki.1 However, early reports suggest that nonpublication of trial results occurs with some frequency, ranging anywhere from 9% to 36%.2–8 Irrespective of discipline, factors and trends associated with RCT nonpublication remain opaque given the heterogeneity and limitations with previous studies.6,9–11 As such, we sought to investigate phase 3 cancer clinical trials using a mandatory Web-based registration database to identify and quantify factors associated with trial nonpublication.

METHODS

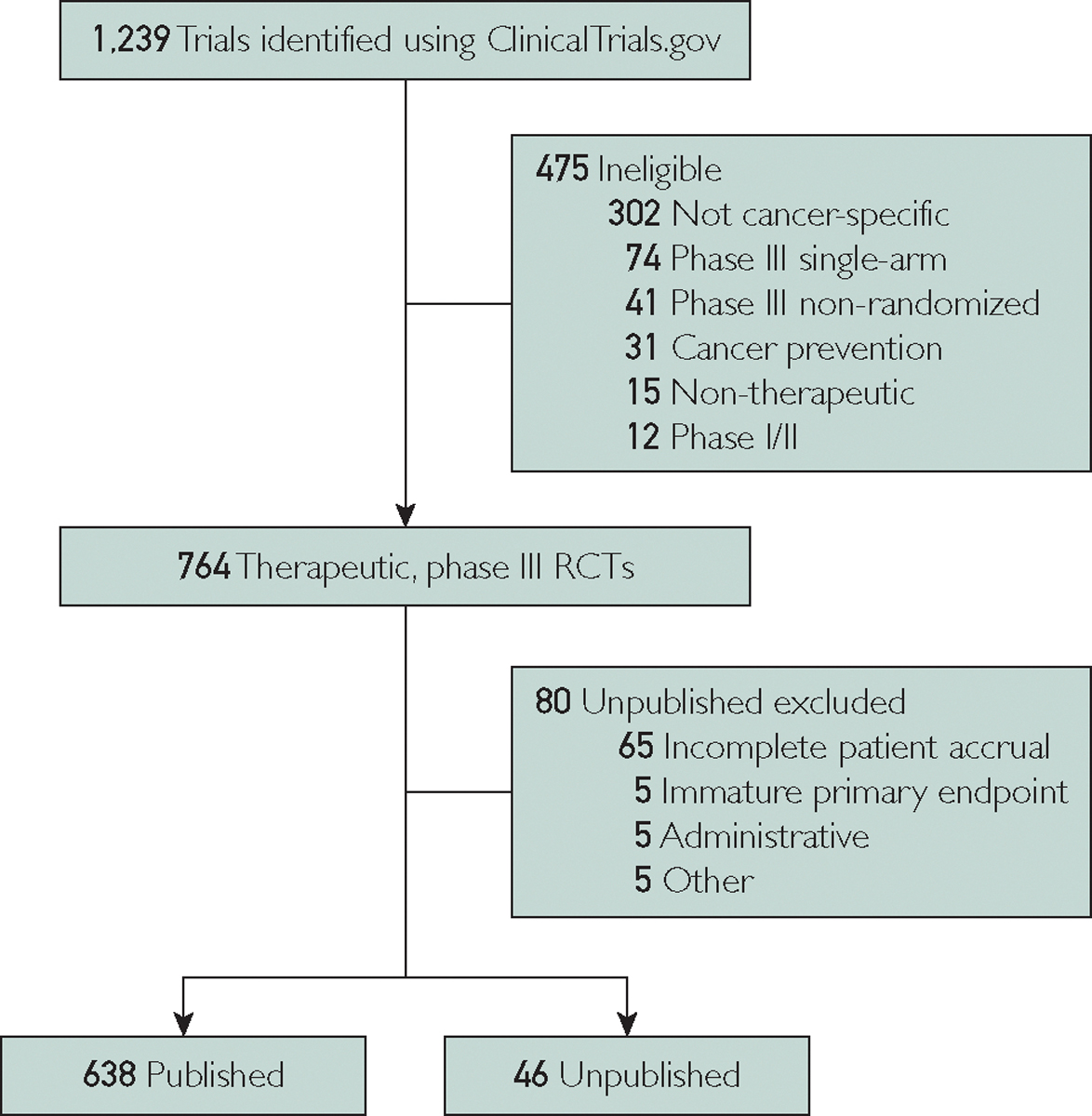

ClinicalTrials.gov was queried using the search term “cancer.” We excluded studies noted as “not yet recruiting.” We included only phase 3 studies with results. This search identified 1239 trials, which were then screened for cancer-specific, interventional, therapeutic, randomized, multi-arm, phase 3 trials that accrued patients from 1994 to 2015, yielding 764 trials (Figure). Data abstraction was finalized February 2020.

FIGURE.

Flowchart of trial screening and inclusion. Of 1239 trials that were identified, 475 were deemed ineligible. The final cohort included 764 phase 3, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with a therapeutic and interventional intent. Of those, 80 were excluded to generate 638 published trials and 46 unpublished trials.

Peer-reviewed manuscripts and meeting abstracts were identified by searching PubMed and Google Scholar. Publication was defined as a peer-reviewed manuscript for the primary endpoint (PEP). Trials were designated as unpublished if no manuscript could be identified or if only a meeting abstract was identified in setting of achieving a mature PEP plus one of the following scenarios: complete patient accrual, incomplete accrual and discontinuation due to safety concerns, and/or incomplete accrual and discontinuation due to sponsor decision. Patient endpoint maturity was defined as a time interval after trial completion being greater than the PEP timeframe specified on ClinicalTrials.gov. The time that has passed since expected PEP maturity for unpublished trials was calculated as the difference from date of manuscript data abstraction and sum of accrual completion date plus expected timeframe of PEP maturity. Trials were censored if results were unpublished due to any of the following: immature PEP, termination for slow/low enrollment, termination for medical supply issue, or termination for administrative reasons (eg, primary investigator leaving institution, lack of funding, and lack of resources).

Given the lack of published trial-level factors, the mean cost of trial enrollment was estimated by extrapolating from experimental data ($6094 per-patient for industry-sponsored trials and $12,233 per-patient for non-industry sponsored trials) and adjusted for inflation from January 1999 to the starting enrollment month and year for each individual trial.12,13 Among the unpublished trials, sponsors/investigators were contacted via electronic mail or phone to confirm the publication status and to determine the reason behind nonpublication.

Pearson’s χ2 tests were used for nominal variables and binary logistic regression analysis for continuous variables. Multiple binary logistic regression modeling included any trial factor with P value less than or equal to .20 when comparing the published versus unpublished cohort. All P values were two-sided, with an α of 0.05; analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 24.0).

RESULTS

Of 764 eligible trials, 80 were excluded primarily due to incomplete accrual (Figure); of the remainder, 638 trials were published (93.3% [638 of 684 trials]; total enrollment included 434,610 patients) and 46 trials were unpublished (6.7% [46 of 684 trials], total enrollment included 13,226 patients). Of the unpublished trials, 28.3% (13 of 46 trials) had a meeting abstract whereas the rest did not have an abstract or final peer-reviewed publication. Among the published trials, the time from start of enrollment to publication was a median of 6 years (interquartile range [IQR], 4 to 8 years). Among the unpublished trials, the time difference from PEP maturity to data abstraction was a median of 6 years (IQR, 4 to 8 years). The estimated inflation-adjusted average cost of accrual for the 13,226 patients in the unpublished cohort was $113,937,849 (range, $41,136,883 to $320,201,063).

Factors associated with unpublished trials included lack of cooperative group sponsorship (P=.005), supportive care investigation aimed at reducing disease or treatment-related toxic effects (P<.001), lower trial patient enrollment (P<.001), restricted performance status (P=.002), uni-institutional enrollment (P=.001), and non-inferiority study design (P=.012) (Table 1). On multiple binary logistic regression modeling, lack of cooperative group sponsorship (no sponsorship vs sponsorship odds ratio [OR], 5.91; 95% CI, 1.35 to 25.97; P=.019) and supportive care investigation (supportive care investigation vs not supportive care investigation OR, 2.90; 95% CI, 1.13 to 7.41; P=.027) were independently associated with unpublished trials. Factors that were not independently associated with unpublished trials included patient enrollment (<100 vs ≥100 patient enrollment OR, 2.80; 95% CI, 0.42 to 18.50; P=.29), performance status (not restricted vs restricted to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score 0–1 OR, 2.49; 95% CI, 0.69 to 9.01; P=.16), institutional enrollment (uni-institutional vs multi-institutional OR, 3.84; 95% CI, 0.86 to 17.08; P=.078), and type of study design (non-inferiority vs superiority OR, 2.23; 95% CI, 0.79 to 6.33; P=.13).

TABLE 1.

| Published | Unpublished | P c | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Total trials | 638 | 46 | — |

| Median enrollment start year (IQR) | 2007 (2005–2010) | 2007 (2005–2009) | .64 |

| Median years to trial completion (IQR)d | 4 (2–6) | 4 (2–6) | .91 |

| Patient enrollment number | <.001 | ||

| <100 | 42 (6.6) | 14 (30.4) | |

| ≥100 | 596 (93.4) | 32 (69.6) | |

| ECOG PS restrictione | .002 | ||

| Yes (restricted to 0–1) | 209 (32.8) | 5 (10.9) | |

| No (not restricted to 0–1) | 429 (67.2) | 41 (89.1) | |

| Supportive care investigationf | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 123 (19.3) | 21 (45.7) | |

| No (systemic therapy, surgery, or radiation) | 515 (80.7) | 25 (54.3) | |

| Cooperative group sponsorshipg | .005 | ||

| Yes | 194 (30.4) | 5 (10.9) | |

| No | 444 (69.6) | 41 (89.1) | |

| Multi-institutional | .001 | ||

| Yes | 601 (94.2) | 38 (82.6) | |

| No | 35 (5.5) | 8 (17.4) | |

| Industry sponsorshipg | .60 | ||

| Yes | 492 (77.1) | 37 (80.4) | |

| No | 146 (22.9) | 9 (19.6) | |

| Study design | .012 | ||

| Superiority | 514 (80.6) | 18 (39.1) | |

| Non-inferiority | 53 (8.3) | 6 (13.0) | |

| Disease site | .35 | ||

| Hematologic | 127 (19.9) | 8 (17.4) | |

| Breast | 112 (17.6) | 11 (23.9) | |

| Thoracic | 92 (14.4) | 8 (17.4) | |

| Genitourinary | 74 (11.6) | 6 (13.0) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 82 (12.9) | 1 (2.2) | |

| Other | 151 (23.7) | 12 (26.1) | |

IQR, interquartile range; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status.

Values shown are n (%) unless othewise specified.

P values reflect Pearson’s χ2 test results for nominal trial factors and logistic regression test results for continuous variable trial factors.

Reflects the time between start of enrollment to primary completion date defined as the final data collection date for primary outcome measure.

Trials were divided by PS restriction versus no restriction; PS restriction was defined as Karnofsky performance status 80–100 or ECOG PS of 0–1.

Reflects the modality used for the primary intervention and randomization of a given trial. Supportive care trials were defined as those where the intervention aimed to reduce disease or treatment-related toxic effects as the primary endpoint.

Cooperative groups included National Cancer Institute—designated cooperative groups and non-NCI cooperative groups. Industry funding and cooperative group sponsorship were considered independent variables because some trials were both sponsored by industry and performed through a cooperative group.

Investigators and/or sponsors were contacted directly to determine reasons for non-publication and the responses are summarized in Table 2. Of 46 unpublished trials, 23 (50.0%) replied to our request for publication status. Reasons for nonpublication were varied but most commonly (n=10 of 23) included that a manuscript was either in preparation or submitted to a peer-reviewed journal. Among these 10 trials, the time difference from PEP maturity to data abstraction was a median of 8 years (IQR, 6 to 12 years); only 1 of 10 investigators stated that publication had been delayed due to requirement for additional biomarker testing to improve the quality of the manuscript. Other reasons included lack of time, funds, or resources (n=3 of 23), lack of priority to warrant publication (n=1 of 23), change in company leadership delaying research enterprise (n=1 of 23), and necessity for additional patient sample testing (n=1 of 23). Some responders (n=8 of 23) acknowledged that a final manuscript could not be identified but did not specify a reason for lack of publication. Industry-sponsorship among the nonresponders vs responders was 87.0% (n=20 of 23) vs 73.9% (n=17 of 23), respectively (P=.26).

TABLE 2.

Reasons for Lack of Trial Publication

| Response | Number of times reporteda |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Manuscript in preparation or submitted for consideration | 10 |

| Replied to inquiry without specifying nonpublication reason | 8 |

| Lack of time, funds, or resources | 3 |

| Lack of priority to warrant publication | 1 |

| Change in company leadership delaying research enterprise | 1 |

| Necessity for additional patient sample testing | 1 |

Based on 23 responders. Multiple categories could be selected by each responder.

DISCUSSION

Among phase 3 cancer clinical trials, we report a 7% nonpublication rate. These trials are believed to be largely abandoned given the estimated 6-year difference since reaching PEP maturity. To our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively review the frequency, factors, and financial impact associated with nonpublication among phase 3 oncologic RCTs.

The most pressing concern with unpublished results is the ethical lapse in the social contract between trialists and participants who willingly put themselves at risk by enrolling in RCTs. Despite the time and effort invested by these volunteers, investigators rarely provide direct communication of results at the conclusion of a trial.14 While the practice of sharing trial results directly with patients should be encouraged, the peer-review publication process is the next best available method. Overall, the dissemination of trial results can be of use to society as a whole, and the integrity of the process must be maintained. While nonpublication remains pervasive, the rate appears to have improved over time in light of previous reports showing 9% to 36% unpublished oncology trials and 30% to 31% across other disciplines.3–7,9–11 However, it is difficult to compare and contrast to prior studies given the differences in methodology and definition of publication. Specifically among prior oncology studies, some were limited to single-institution experiences (30% unpublished rate),9 relied on data solely from national meetings (9% to 26% unpublished rate),6,11 analyzed trials before the US Food and Drug Administration Amendment Act of 2007 that mandated reporting of phase 3 RCTs (9% to 26% unpublished rate),6,11,15 included a heterogeneous compendium of phase 1 to 3 trials (36% unpublished rate for phase 3 trials),9 or evaluated trials within a narrow time period (33% unpublished rate).10 Nonetheless, even a small collection of unpublished trials leads to a loss in knowledge to the general scientific community and has the potential to detrimentally impact patient care through publication bias, which influences policy decisions, clinical guidelines, and systematic reviews resulting by omission of data. Furthermore, the monetary losses to the health care system are burdensome — approximately $114 million over 20 years — even by our conservative estimates since we do not account for the increase in the regulatory, imaging, and molecular pathology costs associated with clinical trials since the methodology used to estimate costs was established in 1999.12

Our findings show factors associated with successful publication of trial results, most notably cooperative group sponsorship, which translated to a 97.5% publication rate (194 of 199 trials). The association of trial publication with cooperative group sponsorship is likely multifactorial and related to, among other factors, multiple invested parties at national and institutional levels (eg, multiple committees overseeing data, including a dedicated publication committee); robust trial design that results from processes that optimize input from scholars, patients, and other stakeholders; data sharing policies for federally funded research that encourage collaboration; and structured publication guidelines (eg, setting a priori publication guidelines and timetables).16,17 Although no laws mandate clinical trial manuscript publication, industry/community/academic partners might benefit from understanding the cooperative group infrastructure that leads to publication accountability. Especially as we move forward to minimize unpublished trials, the cooperative group structure may serve as a framework not only within the oncology community, but for other medicine disciplines.

Notably, supportive care investigations appear to suffer from higher rates of nonpublication than trials assessing other interventions. Supportive care studies can be particularly difficult to design and execute as a result of heterogeneity in the patient population, types of interventions, and assessment tools.18 Moreover, supportive care trials are known to have relatively high patient attrition rates due to symptom burden, thereby making accrual and trial completion more challenging.19 This impact on accrual is noteworthy as we also show that a higher participant enrollment was associated with trial publication, in keeping with previous reports.7,10 These findings relate to larger trials being more likely to accrue sufficient patients for analysis, subject to scrutiny if left unpublished, or given journal preference due to scope and quantitatively driven assessments of scientific merit.

The present study also explored the direct sponsor- and investigator-level reasons contributing to unpublished trials. Unlike previous studies that noted lack of time, funds, or other resources as the main reason for nonpublication, we found that this was not the case in our trial cohort.11 Instead, we were encouraged to observe responders were most likely to cite that the manuscript was in preparation or submitted but not accepted. Interestingly, among the trials with a manuscript in preparation or submitted, the time since expected PEP maturity was actually longer (8 years) than the time for all unpublished trials (6 years); only one investigator extrapolated on the reasons behind the delay. When comparing to other studies that directly contacted investigators, the difference in the reported reasons for nonpublication may be related to the lower response rate in our study compared with the work by Krzyzanowska et al,11 which relied on abstracts from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Unlike meeting abstracts, which list individual investigators who can be readily contacted, ClinicalTrials.gov data often lists generic industry or cooperative group contact information as the sole points of contact, as was the case in the majority of the nonresponders in our study. Similarly, we received a number of generic replies from individuals representing industry sponsors who were not directly involved with the trials in question; these individuals uniformly did not offer specific reasons for nonpublication.

Study Limitations

Multiple study limitations should be noted when interpreting these results. Our initial search parameters were limited to trials “with results” to ensure that we identified trials that had any accrual and a mature PEP. However, this approach could underestimate unpublished trials that were not compliant with mandatory results reporting on ClinicalTrials.gov. We would not expect this effect to be large given that reporting of phase 3 results on ClinicalTrials.gov is mandatory per the US Food and Drug Administration Amendment Act of 2007, and, as shown here, investigations were allowed extended intervals (median 6 years after PEP maturity) after anticipated trial completion to report their results.15 Unlike previous studies, we specifically censored trials that did not meet accrual goals or lacked PEP maturity as we could not make a determination if the PEP was powered sufficiently to allow for meaningful analysis. However, these limitations primarily relate to the estimate of incidence of unpublished studies. Analyses of the correlates of unpublished studies are less vulnerable to those limitations, in our opinion, as the factors that lead to a trial’s successful reporting would not be expected to vary systematically in the trials we included vs trials that were not captured in our dataset. Finally, the clinical trial costs were estimated and extrapolated given the lack of individual unpublished trial data and research protocols, which likely underestimates the true costs associated with trial accrual.

CONCLUSION

The failure to publish randomized controlled trials has a negative impact on research enterprise and patient care. The general scientific community should consider implementing safeguards (eg, multi-stakeholder committees, creating mandates tied to federal grant funding, encouraging direct communication of results to trial participants, or making use of preprints) to limit the nonpublication of clinical trial data.

Grant Support:

This research was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Support Grant P30 CA016672.

Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- PEP

primary endpoint

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

Footnotes

Potential Competing Interests: Dr Koong reports stock ownership in Aravive. Dr Das reports personal fees from Adlai Nortye. Dr Jagsi reports stock ownership and a board advisory role in Equity Quotient; personal fees from Amgen and Vizient; and grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Debbie’s Dream Foundation, the Greenwall Foundation, and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan. Dr Fuller reports honoraria from the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio and Elekta AB; royalties from Demos Medical Publishing; travel expenses/accomodations from Oregon Health and Science University, Great Baltimore Medical Center, University of Illinois Chicago, Elekta AB, and the Translational Research Institute of Australia; and grants from the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health. The remaining authors report no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Dario Pasalic, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX.

C. David Fuller, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX.

Walker Mainwaring, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX.

Timothy A. Lin, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD.

Austin B. Miller, The University of Texas Health Science Center, McGovern Medical School, Houston, TX.

Amit Jethanandani, The University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Medicine, Memphis, TN.

Andres F. Espinoza, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX.

Aaron J. Grossberg, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR.

Reshma Jagsi, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Prajnan Das, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX.

Albert C. Koong, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX.

Claus Rödel, University of Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany; German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany; German Cancer Consortium, Frankfurt, Germany; Frankfurt Cancer Institute, Frankfurt, Germany.

Emmanouil Fokas, University of Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany; German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany; German Cancer Consortium, Frankfurt, Germany; Frankfurt Cancer Institute, Frankfurt, Germany.

Charles R. Thomas, Jr, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR.

Bruce D. Minsky, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX.

Ethan B. Ludmir, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(3):252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whittington CJ, Kendall T, Fonagy P, Cottrell D, Cotgrove A, Boddington E. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in childhood depression: systematic review of published versus unpublished data. Lancet. 2004;363(9418):1341–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roddick AJ, Chan FTS, Stefaniak JD, Zheng SL. Discontinuation and non-publication of clinical trials in cardiovascular medicine. Int J Cardiol. 2017;244:309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pica N, Bourgeois F. Discontinuation and nonpublication of randomized clinical trials conducted in children. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20160223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tam VC, Tannock IF, Massey C, Rauw J, Krzyzanowska MK. Compendium of unpublished phase III trials in oncology: characteristics and impact on clinical practice. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(23):3133–3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Shbool G, Latif H, Farid S, et al. Publication rate and characteristics of lung cancer clinical trials. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1914531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson AL, Fladie I, Anderson JM, Lewis DM, Mons BR, Vassar M. Rates of discontinuation and nonpublication of head and neck cancer randomized clinical trials. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(2):176–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapman PB, Liu NJ, Zhou Q, et al. Time to publication of oncology trials and why some trials are never published. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YP, Liu X, Lv JW, et al. Publication status of contemporary oncology randomised controlled trials worldwide. Eur J Cancer. 2016;66:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krzyzanowska MK, Pintilie M, Tannock IF. Factors associated with failure to publish large randomized trials presented at an oncology meeting. JAMA. 2003;290(4):495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emanuel EJ, Schnipper LE, Kamin DY, Levinson J, Lichter AS. The costs of conducting clinical research. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(22):4145–4150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bureau of Labor Statistics US. Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator. https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl2019. Accessed July 3, 2020.

- 14.Partridge AH, Winer EP. Informing clinical trial participants about study results. JAMA. 2002;288(3):363–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips AT, Desai NR, Krumholz HM, Zou CX, Miller JE, Ross JS. Association of the FDA Amendment Act with trial registration, publication, and outcome reporting. Trials. 2017;18(1):333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health and Human Services US, National Institutes of Health, Office of Extramural Research. NIH Data Sharing Policy. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/data_sharing.

- 17.NRG. NRG Oncology Publications Policy and Guidelines. https://www.nrgoncology.org/Clinical-Trials/Publications2013. Accessed July 3, 2020.

- 18.Bouca-Machado R, Rosario M, Alarcao J, Correia-Guedes L, Abreu D, Ferreira JJ. Clinical trials in palliative care: a systematic review of their methodological characteristics and of the quality of their reporting. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hui D, Glitza I, Chisholm G, Yennu S, Bruera E. Attrition rates, reasons, and predictive factors in supportive care and palliative oncology clinical trials. Cancer. 2013;119(5):1098–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]