Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the effect of postoperative pregnancy on maternal-infant outcomes and transplanted kidney function in kidney transplantation (KT) recipients.

Methods

Our study included 104 KT recipients and 104 non-KT women who delivered at four hospitals affiliated with Zhejiang University School of Medicine from December 2015 to November 2023.

Results

In the KT group, kidney function showed a downward trend after delivery, and most patients recovered normal kidney function within 6 months postpartum. Tacrolimus blood concentration during pregnancy averaged (6.1 ± 1.4) μg/L, increasing to (7.1 ± 2.6) μg/L on the second day after delivery, indicating an upward trend in postpartum concentrations. Compared to the non-KT group, the KT group had higher prevalences of gestational hypertension (33.7% vs. 3.3%), gestational diabetes mellitus (21.2% vs. 17.5%), intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (5.8% vs. 1.7%), placental abruption (1.9% vs. 0.8%), and preterm birth rate (79.8% vs. 9.2%) but had a lower prevalence of fetal growth restriction (8.3% vs. 21.7%). Univariate analysis showed that pre-pregnancy estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), penatal eGFR, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia may influence neonatal outcomes. Binary logistic regression analysis showed that preeclampsia (odds ratio [OR] = 133.89, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.27–156.20, P = 0.031) and hypertension during pregnancy (OR = 5.81, 95% CI: 1.02–33.27, P = 0.048) were risk factors, and glomerular filtration rate during pregnancy (OR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.90–0.99, P = 0.026) was a protective factor.

Conclusion

Although pregnancies in KT recipients are considered high-risk, the overall risks are manageable. Strengthening the management of KT recipients with reproductive intent is recommended to improve maternal and infant outcomes.

Keywords: Postpartum kidney function, Kidney transplantation, Post-transplant pregnancy, Maternal and infant outcomes, Pregnancy complications, Infants

What does this study add to the clinical work?

| Additionally, it provides valuable data for guiding clinical decisions in Chinese KT recipients, addressing a critical gap in the literature. It also emphasizes the importance of individualized preconception counseling and close renal function monitoring, especially for those with pre-existing renal insufficiency. This study enhances clinical practice by highlighting the high risks of gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, and preterm birth in kidney transplant recipients, necessitating vigilant monitoring. |

Introduction

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) experience varying degrees of impaired sexual and reproductive function owing to abnormalities in the hypothalamic-pituitary–gonadal axis. This dysfunction is clinically characterized by irregular menstruation, anovulation, decreased libido, vaginal lubrication issues, difficulty achieving orgasms, and infertility [1]. Kidney transplantation (KT) offers women with CKD and ESKD the possibility of pregnancy, as the hypothalamic-pituitary–gonadal axis can return to normal within 6 months of transplantation [2]. Owing to the risk of adverse maternal complications including pre-eclampsia and hypertension; risk of adverse fetal outcomes such as preterm birth, low birth weight, and small for gestational age (SGA) newborns; potential side effects from immunosuppressive drugs; and risk of allograft function deterioration, pregnancy in KT recipients is considered a high-risk—even when graft function is stabilized, hypertension is well controlled, adherence is good, and close medical monitoring is performed [3].

Collecting data on maternal and infant outcomes in pregnant KT recipients can help us better understand the risks associated with pregnancy post-KT. This understanding is crucial for preconception counseling and pregnancy management in women after KT. Currently, most of the international data on pregnancy after KT are derived from European and American populations, with limited data available for Asian populations, particularly the Chinese population. Therefore, in this study, we conducted an 8-year retrospective comparison of pregnancy processes and maternal-infant outcomes between KT and non-KT groups, aiming to provide a more valuable theoretical basis for clinical pregnancy guidance in KT recipients.

Methods

Patients and data collection

We retrospectively analyzed data that were prospectively collected from the electronic medical record systems of four hospital districts (Qingchun, Yuhang, Zhijiang, and Chengzhan) at the Zhejiang University School of Medicine First Affiliated Hospital. The system collected demographic, clinical, pregnancy, delivery, and neonatal data for all women presenting at our hospital. We reviewed the records of all women who delivered between December 2015 and November 2023, gathering data on the ages of the study population, number of pregnancies, the interval between KT and pregnancy, mode of delivery, pregnancy comorbidities, renal function status, gestational age at delivery, and perinatal immunosuppression regimen. This data was used to retrospectively analyze maternal conditions during pregnancy and postnatal outcomes for both mother and infant in KT recipients. All data were obtained through the electronic medical record system; therefore, the ethics committee waived the need for informed consent. This study was approved by the hospital ethics committee (IIT20230827A). In this retrospective study, we identified and included 104 women in the KT group who had a confirmed pregnancy after KT and delivered at our hospital. Women who did not have regular maternity checkup in our hospital during pregnancy or who had multiple pregnancies were excluded. For the control group, we matched 104 non-transplant women based on the closest admission time to the KT group. Women with pre-pregnancy diagnoses of renal diseases, cancer, or multiple pregnancies were excluded from the control group.

All women who visit our clinic for pregnancy after KT are supervised by a nephrologist and an obstetrician familiar with the effects of kidney disease on pregnancy. In line with the general principles of managing pregnancy in KT recipients at our institution, the management program includes the following: Increased frequency of prenatal examinations (prenatal examination should be performed every 2–4 weeks, depending on the clinical stability until late pregnancy, and then weekly thereafter); early detection and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria; continuous monitoring of maternal renal function every 4–8 weeks; close monitoring for pre-eclampsia; and fetal monitoring using ultrasonography and fetal heart rate monitoring to assess fetal growth and health status respectively. The definition of fetal growth restriction (FGR) was an estimated fetal weight measurement < 10th percentile. If FGR was found, the patient was instructed to lie on the left side and eat a high-protein diet to enhance nutrition. Furthermore, intermittent oxygen inhalation was provided at 3 L/min, 3 times a day, and for 30 min each time, and subcutaneous injection of low molecular weight heparin (4100 U QD) was administered. After one week of treatment, B-ultrasound was performed, and the results were reviewed again. Termination of pregnancy was considered if there was no significant improvement in FGR. Appropriate treatment of maternal hypertension is administered to maintain the systolic and diastolic blood pressure between 130 and 140 and between 80 and 90 mmHg, respectively. Preterm labor intervention may be required in patients with deteriorating renal function, severe pre-eclampsia, FGR, or poor intrauterine status (e.g., fetal distress). For most women, if labor is not imminent by the due date, elective delivery is required [4, 5].

Outcomes and definitions

Maternal outcomes in this study included renal function and pregnancy comorbidities. Indicators used to assess renal function were estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), serum creatinine (Scr), and ultrasound of the transplanted kidney. Pre-pregnancy eGFR and Scr refer to the most recent values obtained before pregnancy was confirmed; gestational eGFR and Scr are the averages of all values recorded during the entire gestation period; and postpartum eGFR and Scr are the averages of all values within 42 days postpartum. Ultrasound of the transplanted kidney was performed on the second day after delivery. Prenatal blood pressure is the average of all measurements taken from the time of hospital admission for labor until delivery, whereas postpartum blood pressure is the average of all values from delivery until the patient is discharged. Pregnancy comorbidities included gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP), placental abruption, premature rupture of membrane (PROM), hysterorrhexis, postpartum infections, and postpartum hemorrhage (PPH).

Neonatal outcomes included APGAR scores, neonatal birth weight, neonatal preterm birth rate, neonatal mortality, and neonatal comorbidities. APGAR scores were defined as appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration at 1, 5, and 10 min after birth in newborns [5]. Neonatal birth weight is defined as the weight of a neonate within 1 h of birth and can be categorized as follows: ultra-low birth weight for birth weight < 1000 g; very low birth weight for birth weight between 1000 and 1500 g; low birth weight for birthweight between 1500 and 2500 g; normal birth weight for birth weight between 2500 and 4000 g; and macrosomia for birth weight ≥ 4000 g [6]. Neonatal comorbidities included neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, neonatal pneumonia, asphyxia neonatorum, neonatal intracranial hemorrhage, congenital heart disease, and FGR.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as means ± standard deviation for normally distributed data or as medians with interquartile range for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables are presented as numbers (percentages). The normality of distributions was assessed using histograms and the Shapiro–Wilk test. Data were processed using SPSS 20.0 statistical software. Independent-sample t-test was used for normally distributed data to compare basic maternal and neonatal information between the KT and non-KT groups, whereas the Mann–Whitney U test was applied for non-normally distributed data. In the KT group, blood pressure before and after pregnancy was compared using paired-sample t-test, and changes in renal function across different time intervals were analyzed using One-way repeated measures analysis of variance. The neonatal outcomes of the KT group were classified, and the variables were screened using univariate logistic regression analysis. After excluding overlapping variables, the variables with P < 0.1 were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis to analyze the factors affecting fetal outcomes. For all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

A total of 104 pregnancies occurred in 104 patients after KT (Table 1). Of these, four pregnancies (3.8%) occurred within 1 year after KT; 44 pregnancies (42.3%) occurred 2–3 years after KT; 26 pregnancies (25%) occurred 4–5 years after KT; 23 pregnancies (22.2%) occurred 6–10 years after KT; and 7 pregnancies (6.7%) occurred 11 or more years after renal KT. The live birth rate among the 104 renal transplant pregnancies was 85.6% (88.5%). The mode and time of delivery were determined by obstetricians, nephrologists, and patients and their family members. All the patients underwent emergency cesarean section because of varying degrees of renal function deterioration, severe preeclampsia, FGR, or adverse intrauterine status. Vaginal deliveries owing to intermediate induced labor were performed in seven cases (3.8%), and induced abortions were performed in eight cases (6.7%).

Table 1.

General characteristics of KT and non-KT groups

| KT groups | non-KT groups | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | 104 | 104 | – |

| Age, years (mean, SD) | 31.8 (4.3) | 32.7 (3.6) | 0.122 |

| times of pregnancy, times (mean, SD) | 1.7 (0.9) | 1.9 (1.1) | 0.130 |

| cesarean section rate (n%) | 92 (100) | 73 (60.8) | – |

KT, kidney transplantation; SD, standard deviation

Pregnancy comorbidities in the transplanted and non-transplanted groups

A comparison of pregnancy comorbidities between the KT and non-KT groups is shown in Fig. 1. The KT group had a higher prevalence of gestational hypertension (33.7%) compared to that had by the non-KT group (3.8%). The prevalence of maternal preeclampsia during pregnancy was 25% in the KT group versus 2.9% in the non-KT group. There was a statistically significant difference between the systolic and diastolic blood pressures obtained before and after delivery in the KT group (P < 0.05), with the patient’s blood pressure returning to normal levels by the time of discharge (Table 2). Sixty-five patients were required to take oral antihypertensive drugs until the 42-day postpartum follow-up visit for blood pressure observation. The prevalence of GDM was 21.2% in the KT group versus 20.2% in the non-KT group. The prevalence of ICP was 5.8% compared to 1.9% in the non-KT group. The prevalence of placental abruption was 1.9% in the KT group versus 1% in the non-KT group. The prevalence of postpartum PPH was the same in both groups at 1.9%. The prevalence of PROM was 2.9% in the KT group compared to 6.7% in the non-KT group. Uterine rupture and postpartum infection did not occur in either group.

Fig. 1.

Pregnancy comorbidities in the transplanted and non-transplanted groups

Table 2.

Changes in blood pressure before and after delivery in the KT group (X ± s)

| Prenatal period | Postnatal period | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 134.9 ± 19.5 | 120.1 ± 11.8 | 6.164 | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood (mmHg) | 86.0 ± 13.9 | 78.7 ± 9.6 | 4.154 | < 0.001 |

KT, kidney transplantation

Kidney function in during pregnancy

The change in kidney function during pregnancy are presented in Tables 3 and 4). The eGFR decreased slightly from pre-pregnancy to postpartum, whereas serum Scr levels increased from pre-pregnancy to pre-delivery and then decreased postpartum. In the three periods, the renal function grades differed (Table 5). Compared with pre-pregnancy, the postpartum renal function grade showed a downward trend. All KT patients underwent an ultrasound examination of the transplanted kidney on the second day after delivery. B-ultrasound results indicated that 91 patients had good perfusion of the transplanted kidney, 12 patients showed hydronephrosis of the transplanted kidney, and one patient experienced kidney failure. Additionally, three patients experienced failure of the transplanted kidney 2 years after delivery, with one of these patients undergoing a second renal transplantation 4 years after delivery. The remaining patients’ renal function returned to normal within 6 months postpartum. Importantly, no cases of kidney rejection occurred during pregnancy.

Table 3.

Pregnancy and renal function in the KT group (n = 104)

| Pre-pregnancy (X ± s) | Prenatal (X ± s) | Postpartum (X ± s) | F | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR (mL/min) | 78.8 ± 23.2 | 76.5 ± 25.4 | 75.4 ± 24.6 | 3.184 | 0.025 |

| Scr (μmol/L) | 93.5 ± 28.5 | 95.3 ± 30.1 | 95.2 ± 33.4 | 0.367 | 0.693 |

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Scr, serum creatinine

Table 4.

Two-by-two comparison of eGFR and Scr at three time periods (n = 104)

| Time | (eGFR) | (eGFR) P | (Scr) | (Scr) P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-pregnancy and prenatal | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 0.183 | -1.8 ± 2.3 | 0.443 |

| Pre-pregnancy and postpartum | 3.5 ± 1.7 | 0.128 | -3.8 ± 3.2 | 0.683 |

| Prenatal and postpartum | 1.1 ± 1.2 | 1.000 | -0.4 ± 1.9 | 1.000 |

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Scr, serum creatinine

Table 5.

Number of people with different grades of kidney function over three time periods (n = 104)

| eGFR (mL/min) | Pre-pregnancy (n,%) | Prenatal (n,%) | Postpartum (n,%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| > 90 | 30 (28.9%) | 33 (31.7%) | 23 (22.1%) |

| 60–89 | 47 (45.2%) | 36 (34.6%) | 48 (46.2%) |

| 30–59 | 26 (25%) | 34 (32.6%) | 30 (28.8%) |

| < 29 | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (0.9%) | 3 (2.9%) |

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate

Changes in immunosuppressive regimen and blood concentrations during pregnancy in the KT group

During pregnancy, 100 patients were on an immunosuppressive regimen of tacrolimus and prednisone combined with azathioprine. Two patients received a combination of cyclosporine and methylprednisolone with azathioprine, and the remaining two patients were on tacrolimus and prednisone combined with imipramine. The FK506 concentration during pregnancy was (6.1 ± 1.4) μg/L, except for two patients whose immunizing drug was cyclosporine. On the second postpartum day, the FK506 blood concentration was (7.1 ± 2.6) μg/L, indicating a trend toward higher levels after delivery.

Neonatal outcomes

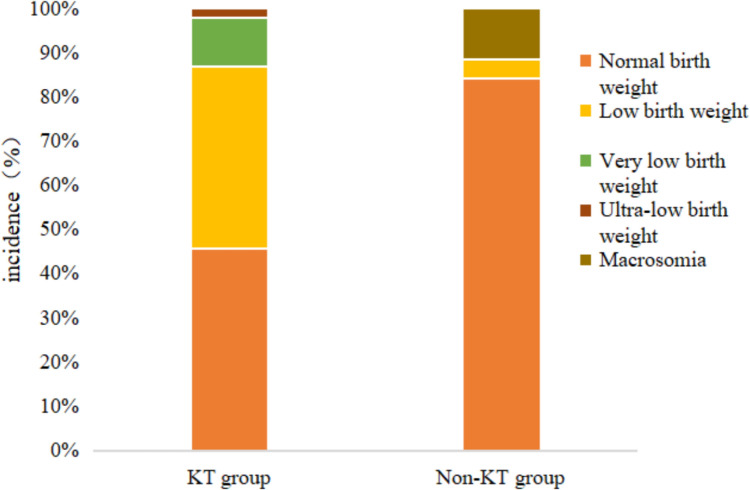

In the KT group, 104 pregnancies resulted in the delivery of eight full-term babies (7.7%), 84 preterm babies (80.8%), four induced abortions (3.8%), and eight vaginal deliveries following intermediate induced labor (7.7%). Among the induced labor cases, one had chromosomal abnormalities, two had intrauterine fetal death, and one was associated with maternal renal function abnormalities (Fig. 2). In the non-KT group, 109 out of the 120 pregnancies (90.8%) resulted in full-term deliveries, whereas 11 (9.2%) were preterm deliveries. Out of 120 newborns in the non-KT group, 104 (86.7%) were healthy, and the prevalence of FGR was 8.3%. Of 92 newborns in the KT group, 18 (19.6%)were healthy, and the prevalence of FGR was 21.7%. The remaining neonates were sent to the neonatal intensive care unit with one or more comorbidities (Fig. 3), but all of them survived the neonatal period. The gestational age, birth weight, and APGAR scores of the neonates in both groups are shown in Table 6, with the distribution of birth weights presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 2.

Pregnancy outcomes in the KT group

Fig. 3.

Neonatal comorbidities in the KT group

Table 6.

General condition of newborns

| General condition | KT group | Non-KT group | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age (week, median [IQR]) | 34.2 (2.6) | 39.1 (1.8) | < 0.001 |

| Birth weight (g, mean ± SD) | 2260.4 ± 593.4 | 3315.0 ± 535.5 | < 0.001 |

| 1-min APGAR score, median [IQR] | 8 (2) | 10 (0) | < 0.001 |

| 5-min APGAR score, median [IQR] | 9 (1) | 10 (0) | < 0.001 |

| 10-min APGAR score, median [IQR] | 10 (0) | 10 (0) | < 0.001 |

IQR, interquartile range; APGAR, appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration; KT, kidney transplantation; SD, standard deviation

Fig. 4.

Birth weight distribution of newborns

To clarify the influence of maternal factors on neonatal outcomes, the KT group was further divided into the healthy and unhealthy neonates group according to the condition of the delivered fetus. Variables with P < 0.10 in univariate analysis (Table 7), including eGFR before pregnancy, eGFR during pregnancy, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia, were included in the binary logistic regression analysis. The results showed that preeclampsia (odds ratio [OR] = 133.89, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.27–156.20, P = 0.031) and hypertension during pregnancy (OR = 5.81, 95% CI: 1.02–33.27, P = 0.048) were risk factors, and high eGFR during pregnancy (OR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.90–0.99, P = 0.026) was a protective factor.

Table 7.

Univariate analysis of maternal factors on neonatal outcomes

| Items | Healthy newborn group (n = 18) | Unhealthy newborn group (n = 74) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age/years, x ± s | 31.39 ± 4.13 | 31.89 ± 4.23 | 0.646 |

| Times of pregnancy/ times | 1.61 (1.26, 1.96) | 1.58 (1.39, 1.78) | 0.888 |

| Interval duration/years, x ± s | 4.50 (2.84, 6.16) | 4.97 (4.29, 5.65) | 0.549 |

| Pre-pregnancy eGFR /(mL/min), x ± s | 89.23 ± 16.39 | 75.59 ± 21.75 | 0.019 |

| Prenatal eGFR /(ml/min), x ± s | 91.00 ± 18.42 | 71.64 ± 22.84 | 0.003 |

| GDM, n (%) | 1 (5.56) | 19 (25.68) | 0.236 |

| Gestational hypertension, n (%) | 2 (11.11) | 29 (39.19) | 0.075 |

| Preeclampsian, n (%) | 1 (5.56) | 22 (29.73) | 0.063 |

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate, DM, gestational diabetes mellitus

Discussion

Several factors, including immunosuppressive medications (calcineurin phosphatase inhibitors and corticosteroids), allograft function, donor type, obesity, alcohol, smoking, and elevated renin levels, contribute to the development of gestational hypertension and diabetes in KT recipients [7]. In this study, the incidence of postoperative gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, and GDM in the KT group was significantly higher at 33.7%, 25%, and 21.2%, respectively, compared to 3.3%, 2.5%, and 17.5% in the non-KT group. These rates are also considerably higher than those in the general Chinese maternity population, where the incidence rates are 5%, 4.6%, and 8.8%, respectively [8, 9]. This highlights the increased risk of hypertension-related disorders in pregnancies of renal transplant recipients. International comparisons reveal similar trends. A study in the United Kingdom [10] reported a 24% incidence of pre-eclampsia in KT recipients compared to 4% in controls, whereas a US meta-analysis showed pre-eclampsia in 27% and a GDM prevalence in 8% of KT pregnancies, compared to 4% for both conditions in the general population [11].

The present study found that kidney function showed a downward trend after delivery and most patients’ renal function returned to normal within 6 months postpartum, although five patients experienced graft failure 2 years postpartum. These patients had significant pre-existing renal insufficiency before pregnancy, suggesting that although pregnancy generally does not significantly impact patients with good renal transplant function, it does adversely affect recipients with severe pre-existing renal insufficiency owing to the increased physiological demands during pregnancy. A comparison with a similar study by Shah et al. [3] showed that long-term renal function and graft survival rates in KT patients were similar between pregnant and non-pregnant groups, supporting the notion that pregnancy does not have long-term adverse effects on the transplanted kidney or patient survival. However, this study’s findings differ for recipients with significantly impaired renal function before pregnancy. Given the retrospective nature of this study, further research is needed to assess the long-term effects of pregnancy on the transplanted kidney.

Immunosuppressive drug regimens are usually tailored to individual needs and transplant center protocols, making it challenging to assess drug variability. However, close monitoring of drug concentrations is essential. In this study, FK506 doses were increased during pregnancy and decreased after delivery to maintain therapeutic levels, reflecting the physiological changes in pregnant women. The unbound concentration of FK506 nearly doubled during pregnancy and the postpartum period compared to the pre-pregnancy period [12]. Renal blood flow increases by approximately 35% and eGFR by 50% during late pregnancy, elevating drug clearance [13]. The mean oral apparent clearance (CL/F) of FK506 can reach (47.4 ± 12.6) L/h during the second and third trimesters, 39% higher than that in the postpartum period [14]. Maintaining appropriate drug levels is crucial, emphasizing the need for dynamic dose adjustments based on perinatal monitoring. It has been suggested that the dose of FK506 should be increased to 25% of the pre-pregnancy dose to maintain effective therapeutic concentrations but it should be rapidly decreased after delivery to ensure patient blood levels [15]. Therefore, KT patients need to closely monitor perinatal blood concentration changes and dynamically adjust the dosage according to the monitoring results to maintain the blood concentration.

Although fertility is typically restored after KT, pregnancy and live birth rates remain significantly lower than those in the general population [16, 17]. China’s 2020 Statistical Bulletin of Health Care Development [18] reports a national live birth rate of 99.46%, whereas a Canadian study [11] of 30,078 female KT recipients reported a live birth rate of 55%. In this study, the live birth rate was 85%, higher than that in foreign studies but lower than that in the general population. However, the preterm birth rate was 80%, markedly exceeding China’s overall preterm birth rate of 7.3% [19].

Compared with other studies in China, a 7-year single-center study [20] in Sichuan Province reported a neonatal preterm birth rate of 75% and a 4% induced abortion rate, similar to our findings of 80% and 3.8%, respectively. Internationally, a British study found a 52% preterm delivery rate in KT recipients compared to 8% in the general population [21]. In Poland, a 31-year study [2] reported a 10% spontaneous abortion rate and a 6.5% intrauterine death rate, compared to 4.8% and 1.9% in our study. The higher preterm delivery rate in this study may be owing to the common practice of cesarean sections in KT recipients to reduce risks to the transplanted kidney; however, this approach often results in premature births and poor neonatal outcomes. Although the pelvic-transplanted kidneys of most patients do not obstruct the birth canal [22], medical staff often choose cesarean section over vaginal delivery to better control the risks to both mothers and infants. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on healthcare access may have exacerbated these challenges [23].

Our results show that pre-pregnancy eGFR, prenatal eGFR, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia may be the influencing factors of neonatal outcomes. The binary logistic regression analysis showed that preeclampsia and hypertension during pregnancy were risk factors, and high eGFR during pregnancy was a protective factor. This is consistent with the results of a related study [24]. In the future, we will focus on monitoring the blood pressure and renal function of kidney transplant patients during pregnancy to reduce the incidence of and improve neonatal outcomes.

The optimal time for conception after KT remains debated. The American Society of Transplantation [25] recommends conception within 1–2 years post-transplantation, whereas European guidelines suggest a delay of 2 years [22]. Early conception increases the risk of pre-eclampsia and preterm labor, whereas delaying conception leads to advanced maternal age, increasing the risk of miscarriage and missed reproductive opportunities [2]. A study by Rose [26] that included 729 KT recipients indicated an increased risk of transplant failure within the first 3 years post-transplantation, suggesting that young recipients should delay conception. Similarly, Gonzalez et al. [27] found that the lowest live birth rate and the highest neonatal mortality rate occurred in pregnancies that occurred within 2–3 years post-KT. In this study, the mean interval between renal transplantation and pregnancy was 4 years, with a mean maternal age of 31 years and a live birth rate of 85%. However, determining the optimal time for conception is challenging owing to the limitations of the study’s retrospective design, small sample size, and potential reporting bias from voluntary registry data. It is usually recommended that women wait at least 1 year after a living-related donor transplant and at least 2 years after a deceased donor transplant before attempting pregnancy. This waiting period helps reduce the risk of immunotherapy-induced complications and rejection. Additionally, the transplanted kidney should have a stable function with a blood creatinine level below 1.5 mg/dL and a urinary protein excretion rate under 500 mg/d [11].

This study has some limitations. First, the retrospective study only included renal transplant recipients from pregnancy to delivery without tracking neonatal growth and development. Second, the study’s small, regionally limited sample size may not be representative, necessitating larger, multicenter studies.

In conclusion, although pregnancy in renal transplant recipients is considered high-risk, the overall risk remains manageable. It is recommended to enhance the management of renal transplant patients with reproductive intent, monitor relevant indicators throughout the pregnancy in real-time, intervene early when necessary, and suggest appropriate intervals for post-transplantation pregnancy to improve maternal and infant outcomes. With the advancement of the “Internet + healthcare” model in China and the era of medical big data, we plan to establish a real-time communication and intervention management platform for pregnant post-KT recipients in future studies, aiming to improve disease management and maternal and infant outcomes.

Author contributions

Yan Zhang and Lily Zhang made significant contributions to the design and implementation of the study; Yan Zhang, Tongwei Zhu, Lulu Fang, and Lily Zhang conducted the data collection and analysis, and Yan Zhang drafted the article; Weicong Xia critically reviewed the article's intellectual content from its content;All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project was funded by a grant from the Zhejiang Province Medical and Health Science and Technology Program (2023RC161) for a research project on pregnancy in renal transplant recipients.

Data availability

Raw data were generated at Zhejiang University School of Medicine First Affiliated Hospital. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (Yan) on request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Zhejiang University School of Medicine First Affiliated Hospital (IIT20230827A). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study by the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Montagud-Marrahi E, Cuadrado-Payán E, Hermida E et al (2022) Preemptive simultaneous pancreas kidney transplantation has survival benefit to patients. Kidney Int 102:421–430. 10.1016/j.kint.2022.04.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dębska-Ślizień A, Gałgowska J, Bułło-Piontecka B et al (2020) Pregnancy after kidney transplantation with maternal and pediatric outcomes: a single-center experience. Transplant Proc 52:2430–2435. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2020.01.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah S, Venkatesan RL, Gupta A et al (2019) Pregnancy outcomes in women with kidney transplant: meta analysis and systematic review. BMC Nephrol 20:24. 10.1186/s12882-019-1213-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rojas R, Palmer BF (2024) Sexual and reproductive health after kidney transplantation. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/sexual-and-reproductive-health-after-kidney-transplantation?search=%E8%82%BE%E7%A7%BB%E6%A4%8D%E6%9C%AF%E5%90%8E%E5%A6%8A%E5%A8%A0&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- 5.Snir A, Zamstein O, Wainstock T, Sheiner E (2024) Long-term neurological outcomes of offspring misdiagnosed with fetal growth restriction. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 10.1007/s00404-024-07525-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang K, Si S, Chen R et al (2021) Preterm birth and birth weight and the risk of type 1 diabetes in Chinese children. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 12:603277. 10.3389/fendo.2021.603277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vannevel V, Claes K, Baud D et al (2018) Pre-eclampsia and long-term renal function in women who underwent kidney transplantation. Obstet Gynecol 131:57–62. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo YF, Yang N (2022) Intensive blood pressure control advised by Chinese experts. Chin J Hypertens 2:113–117. 10.16439/j.issn.1673-7245.2022.02.004 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agius A, Sultana R, Camenzuli C, Calleja-Agius J, Balzan R (2018) An update on the genetics of pre-eclampsia. Minerva Ginecol 70:465–479. 10.23736/S0026-4784.17.04150-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandra A, Midtvedt K, Åsberg A, Eide IA (2019) Immunosuppression and reproductive health after kidney transplantation. Transplantation 103:e325–e333. 10.1097/TP.0000000000002903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gill JS, Zalunardo N, Rose C, Tonelli M (2009) The pregnancy rate and live birth rate in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 9:1541–1549. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02662.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein CL, Josephson MA (2022) Post-transplant pregnancy and contraception. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 17:114–120. 10.2215/CJN.14100820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiramatsu Y, Yoshida S, Kotani T et al (2018) Changes in the blood level, efficacy, and safety of tacrolimus in pregnancy and the lactation period in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 27:2245–2252. 10.1177/0961203318809178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H, Jeong JC, Yang J et al (2015) The optimal therapy of calcineurin inhibitors for pregnancy in kidney transplantation. Clin Transplant 29:142–148. 10.1111/ctr.12494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez Suarez ML, Kattah A, Grande JP, Garovic V (2019) Renal disorders in pregnancy: core curriculum 2019. Am J Kidney Dis 73:119–130. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golocan-Alquiza IFG, Cabanayan-Casasola CB, Faustino KM, Flores ME (2019) Patient and graft outcomes among Filipino post-kidney transplant pregnancies. Transplant Proc 51:2718–2723. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.02.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKay DB, Josephson MA (2008) Pregnancy after kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3(Suppl 2):S117–S125. 10.2215/CJN.02980707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.China government website.Health care.Statistical bulletin on the development of health care in China in 2020 (2020).Available at:http://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2021-07/22/content_5626526.

- 19.Chen C, Zhang JW, Xia HW et al (2019) Preterm birth in China between 2015 and 2016. Am J Public Health 109:1597–1604. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fen XB, Xu TT, Song TR et al (2021) A retrospective cohort study of postoperative pregnancy in renal transplant recipients. Chin J Organ Transplant 42:269–273. 10.3760/cma.j.cn421203-20210405-00120 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bramham K, Nelson-Piercy C, Gao H et al (2013) Pregnancy in renal transplant recipients: a UK national cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8:290–298. 10.2215/CJN.06170612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.European best practice guidelines for renal transplantation. Section IV: Long-term management of the transplant recipient. IV.10. Pregnancy in renal transplant recipients.(2002). Available at: https://europepmc.org/article/MED/12091636 [PubMed]

- 23.China government website.Health care.Notice on Further Promoting the "Internet + Healthcare" "Five-one" Service Action (2020).Available at: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-12/10/content_5568777.htm

- 24.Gosselink ME, van Buren MC, Kooiman J et al (2022) A nationwide Dutch cohort study shows relatively good pregnancy outcomes after kidney transplantation and finds risk factors for adverse outcomes. Kidney Int 102(4):866–875. 10.1016/j.kint.2022.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKay DB, Josephson MA, Armenti VT et al (2005) Reproduction and transplantation: report on the AST consensus conference on reproductive issues and transplantation. Am J Transplant 5:1592–1599. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00969.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rose C, Gill J, Zalunardo N, Johnston O, Mehrotra A, Gill JS (2016) Timing of pregnancy after kidney transplantation and risk of allograft failure. Am J Transplant 16:2360–2367. 10.1111/ajt.13773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzalez Suarez ML, Parker AS, Cheungpasitporn W (2020) Pregnancy in kidney transplant recipients. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 27:486–498. 10.1053/j.ackd.2020.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data were generated at Zhejiang University School of Medicine First Affiliated Hospital. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (Yan) on request.