Abstract

Background

Eating disorders (EDs) have traditionally been viewed as a Western phenomenon, but their prevalence in South Asia has risen due to urbanization, globalization, and Westernized beauty ideals. This systematic analysis examines trends and prevalence of Anorexia nervosa (AN) and Bulimia nervosa (BN) using the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) data from 1990 to 2021.

Methods

This analysis used data from the GBD study on age-standardized prevalence rates (ASPRs) for AN and BN, as well as their total percentage changes (TPCs) from 1990 to 2021. Trends were analyzed using Joinpoint regression to identify changes over time and calculate annual percent changes (APCs) and average annual percent changes (AAPCs). Geospatial patterns and temporal changes were visualized using QGIS software. The correlation between the Sociodemographic Index (SDI) and the DALY rate was assessed using R software.

Results

The ASPR of EDs increased significantly from 1990 to 2021, with BN peaking in the 20–24 age group and AN in the 15–19 and 20–24 age groups. Females exhibited the highest rates of increase, while notable rises were also observed in males. Bhutan recorded the highest ASPR for both AN and BN, with varying temporal percentage changes across countries. A significant positive correlation was found between the SDI and DALY rates across 21 global regions, with anorexia nervosa showing the strongest correlation (r = 0.75, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

The rising burden of EDs in South Asia underscores an urgent need for culturally sensitive prevention strategies and public health policies. Targeted interventions addressing sociocultural drivers are essential to mitigate the growing impact of EDs in this region.

Level of evidence

Level V, Descriptive study.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40519-025-01746-z.

Keywords: Appetite disorders, Binge-eating disorder, Food addiction, South Asia, Global Burden of Disease

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) are a set of complex mental health conditions characterized by abnormal eating behaviors and preoccupations with body weight, shape, or food, which can severely impact physical, emotional, and social well-being [1–3]. The weighted mean prevalence of EDs rose significantly from 3.5% during 2000–2006 to 7.8% in 2013–2018 [4]. Among these, Anorexia nervosa (AN) and Bulimia nervosa (BN) are the most prevalent, especially during adolescence, a critical developmental phase marked by significant physical and psychosocial changes [4, 5]. These disorders are disproportionately observed in females, with rates approximately three times higher than in males [6, 7]. Their effects extend beyond psychological distress, often resulting in severe somatic complications, including cardiovascular issues, bone density loss, and gastrointestinal damage [1].

Historically viewed as a Western cultural phenomenon, EDs are now increasingly recognized as a global health issue, with significant rises in prevalence across non-Western regions, including South Asia [8–10]. This shift is attributed to factors such as urbanization, globalization, and the pervasive influence of Western ideals of body image through media and societal changes [11, 12]. Despite traditional South Asian cultural preferences for fuller body types, urban adolescents, particularly girls, are increasingly adopting Western standards of thinness, leading to heightened body dissatisfaction and risky eating behaviors [13].

Existing research highlights alarming trends in South Asia, such as a prevalence of disordered eating patterns among Indian adolescents. Yet, much of the available data are derived from small-scale studies with limited variables, underscoring the need for comprehensive analyses. A thorough understanding of the epidemiology of EDs in this region is crucial to inform diagnosis, prevention, and mental health policy interventions.

This systematic analysis leverages data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study (1990–2021) to examine the prevalence and trends of EDs in South Asia. By exploring the intersection of sociocultural, psychological, and individual factors, the study aims to provide insights that can shape targeted strategies for mitigating the growing burden of these conditions in the region.

Methods

Data source

Data for this study were taken from the GBD 2021 study. The GBD Study employs a comprehensive and systematic methodology to estimate health outcomes across geographies and time. It utilizes secondary data sources, ensuring inclusivity and comparability. Key sources include censuses, population registries, vital registration systems, hospital data, health insurance claims, surveys, disease registries, and published literature. The full methodology of the GBD is provided in the cited reference [14]. For the current study, the data we used include age-standardized prevalence (ASPR) and DALYs (ASDR) per 100,000 for EDs (AN and BN) for males, females, and both genders combined from 1990 to 2021 [15].

Statistical analysis

This study used Joinpoint regression analysis to observe trends in the ASPRs of AN and BN among males, females, and both sexes combined from 1990 to 2021. Joinpoint regression is a statistical modeling approach particularly useful for identifying points in time, where a significant change in the linear trend of data occurs [14]. This method partitions data into linear segments connected at joinpoints, facilitating the detection and quantification of temporal trends. The analysis was conducted using the Joinpoint Regression Program (Version 5.2.0), developed by the National Cancer Institute [16]. This program uses a grid-search method to fit the segmented regression model, allowing for an optimal number of joinpoints to be determined. The heteroscedasticity-corrected errors approach was employed under the assumption of constant variance (homoscedasticity), ensuring robust estimations. Model selection relied on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) with weighted adjustments to account for model complexity and data variability. For each linear segment identified, the Annual Percent Change (APC) was calculated with corresponding empirical quantile-based confidence intervals, offering a precise measure of the rate and direction of change. In addition, the Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC) was derived as a summary measure of trends over the entire study period (1990–2021. Geographical maps depicting the ASPR in 2021 and the total percentage change (TPC) from 1990 to 2021 for AN and BN in South Asia were created using QGIS software [17]. Microsoft Excel was used to create bar charts illustrating the distribution of ASPR for AN and BN across different age groups. Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed using R software to assess the linear or non-linear relationship between the ASDR of EDs and 21 global regions stratified by the Sociodemographic Index (SDI).

Results

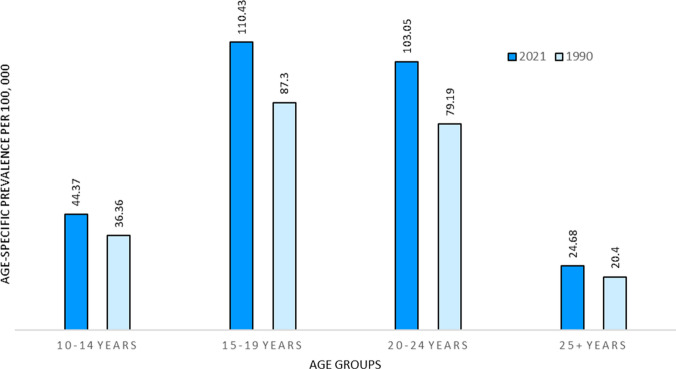

The age-specific rates of BN showed the highest prevalence among the 20–24 age group, with a prevalence rate of 355.46 (95% UI: 165.5–627.1) per 100,000 in 2021 and 237.68 (95% UI: 110.6–419.3) per 100,000 in 1990 (Fig. 1). Meanwhile, the prevalence rate of AN was predominantly distributed among the 15–19 and 20–24 age groups (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Age-specific prevalence rate of Bulimia nervosa in South Asia among different age groups in 1990 and 2021

Fig. 2.

Age-standardised prevalence rate of Anorexia nervosa (AN) in South Asia among different age groups in 1990 and 2021

Joinpoint regression analysis for the ASPR of BN revealed increasing trends across all sexes from 1990 to 2021 (Fig. 3). The highest APC for the ASPR of BN among both sexes combined was observed between 2005 and 2011, with a value of 1.92 (95% CI 1.85–2.07). For males, the highest APC was recorded between 2006 and 2010, at 1.89 (95% CI 1.80–2.01), while for females, it was between 2005 and 2011, with a value of 2.02 (95% CI 1.92–2.25).

Fig. 3.

Joinpoint analysis of age-standardised prevalence rate of Bulimia nervosa (BN) from 1990 to 2021. a For both sexes combined; b for male; c for female

Figure 4 shows increased trends in the ASPR of AN from 1990 to 2021. Between 2014 and 2019, the highest APC for both sexes combined was 1.29 (95% CI 0.88–1.46). For AN, the highest APC in men was recorded between 2017 and 2021, at 1.17 (95% CI 1.03–1.46), while for females, it was between 2015 and 2019, at 1.47 (95% CI 1.41–1.58).

Fig. 4.

Joinpoint analysis of age-standardised prevalence rate of Anorexia nervos (AN) a from 1990 to 2021. a For both sexes combined; b for male; c for female

The AAPC from 1990 to 2021 for both sexes combined was 0.85* (95% CI 0.83–0.86) for AN and 1.35* (95% CI 1.34–1.37) for BN (Table 1). The highest AAPC was observed in females for AN and in males for BN. All p values were statistically significant, with a value of < 0.00001.

Table 1.

Average annual percentage change of age-standardised prevalence rate of eating disorders in South Asia from 1990 to 2021

| Gender | Years | Average annual percentage change (95% C.I) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anorexia nervosa | p value | Bulimia nervosa | p value | ||

| Both | 1990–2021 | 0.85* (0.83–0.86) | < 0.000001 | 1.35* (1.34–1.37) | < 0.000001 |

| Male | 1990–2021 | 1.17* (1.03–1.46) | < 0.000001 | 1.28* (1.27–1.29) | < 0.000001 |

| Female | 1990–2021 | 0.88* (0.88–0.89) | < 0.000001 | 1.4* (1.39–1.42) | < 0.000001 |

*Indicates AAPC is significantly different from zero at the alpha = 0.05 level

The ASPR of BN was highest in Bhutan in 2021, at a rate of 143.57 (95% UI: 92.69–209.08) per 100,000, followed by India and Pakistan (Fig. 5a). However, the TPC observed in Bhutan and India was similar, at approximately 56% from 1990 to 2021 (Fig. 5b). The lowest TPC was observed in Pakistan, with a value of 23.65%.

Fig. 5.

Map of South Asia showing age-standardised prevalence and total percentage change in prevalence rate of Bulimia nervosa (BN) from 1990 to 2021

In Fig. 6a, Bhutan showed the highest ASPR for AN in 2021, though it did not vary significantly from other countries. Other countries exhibited ASPRs for AN in the range of 30.67–34.01 per 100,000. Bhutan also showed the highest TPC for the ASPR of AN from 1990 to 2021, followed by India (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Map of South Asia showing age-standardised prevalence and total percentage change in prevalence rate of Anorexia nervos (AN) a from 1990 to 2021

Figure 7 shows a significant positive correlation between ASDR and SDI, with varying strengths across different eating disorders. For combined eating disorders, ASDR exhibits a significant correlation with SDI (r = 0.68, p < 0.001). Among individual disorders, ASDR for anorexia nervosa shows the strongest correlation with SDI (r = 0.75, p < 0.001). Similarly, ASDR for bulimia nervosa demonstrates a positive correlation with SDI (r = 0.63, p < 0.001).

Fig. 7.

Age-standardized DALY rate (ASDR) for eating disorders from 1990 to 2021 in 21 regions, stratified by Socio-Demographic Index (SDI). The black line represents the expected values based on ASDR and SDI from 1990 to 2021. a Eating disorders; b Anorexia nervosa; c Bulimia nervosa

Discussion

This systematic analysis presents compelling evidence of the rising burden of EDs in South Asia, a trend largely consistent with the broader global rise but also uniquely shaped by regional sociocultural dynamics. The increase in age-standardized ASPR of AN and BN from 1990 to 2021 underscores a significant public health concern that mirrors the complex interplay of globalization, urbanization, and cultural shifts towards Western ideals of thinness and beauty [18, 19].

The distinct rise in ASPR, particularly among younger demographics, highlights the critical vulnerability of this group. Adolescence and early adulthood are formative periods marked by heightened self-awareness and susceptibility to societal pressures, which are now amplified by pervasive media portrayals of ideal body images [20, 21]. This study's findings suggest that these influences are progressively dismantling traditional South Asian norms that once celebrated more diverse body types, replacing them with more restrictive Western standards that valorize thinness [22].

The Joinpoint regression analysis reveals a continuous increase in ED prevalence across both sexes, with the highest increases noted in younger females. This is indicative of the gendered nature of EDs, where societal pressures concerning body image are disproportionately directed towards women [23]. However, the increasing trends in males highlight that EDs are not exclusively female disorders and that male body image concerns are also deserving of attention.

The geographical variability observed, with countries like Bhutan showing significantly higher rates of increase compared to others like Pakistan, may reflect differential exposure to and integration of Western cultural norms [19, 24, 25]. It could also indicate varying degrees of health literacy, urbanization rates, and accessibility to media content across these regions [26, 27]. This suggests that localized public health strategies are essential in addressing the specific needs and challenges of each region.

The strong positive correlation between ASDR and SDI in eating disorders aligns with prior findings, particularly for AN (r = 0.75), which is more prevalent in high-SES populations. Koch et al. (2022) found that high parental income and education increased AN risk, possibly due to sociocultural pressures and perfectionism. BN (r = 0.63) follows a similar but weaker trend. The correlation for combined disorders (r = 0.68) suggests better diagnosis in high-SDI countries but also highlights barriers to effective treatment [28, 29].

The healthcare system in South Asia struggles to diagnose, treat, and prevent EDs. There are few trained professionals and mental health facilities, making treatment difficult. Specialized ED treatment centers are limited. Many people are unaware of EDs, and stigma prevents them from seeking help. Referral rates are low, and services are not widely used. Policies for early detection and treatment need improvement. More awareness programs, better resources, and stronger policies are needed to ensure people get help in time [22].

Future research should focus on longitudinal studies to better understand the trajectories of EDs in South Asia. Such studies could explore deeper into the sociocultural, economic, and individual psychological factors driving these trends. In addition, there is a critical need for developing and implementing culturally appropriate prevention and intervention programs [30]. These programs should not only aim at increasing awareness and education about EDs but also at building resilience against the socio-cultural pressures that foster unhealthy body images.

Furthermore, policy interventions must be sensitive to the cultural context of South Asia. Strategies that include engagement with community leaders and the use of culturally resonant messaging may be more effective in altering the current trajectories of ED prevalence. Integrating mental health services with routine health care visits could also help in early identification and management of EDs, reducing the long-term health impacts associated with these disorders.

A key limitation of this study is the significant differences and uncertainties in data collection across countries within the GBD study, stemming from variations in data availability, quality, and processing methods. Many low- and middle-income countries lack complete vital registration systems and instead rely on verbal autopsy, which has inherent limitations. In regions without recent censuses, population estimates remain uncertain. In addition, data processing steps, such as reclassifying vague causes of death, can impact results. The reliance on cohort data from high-income countries for risk estimations may not fully account for regional differences, further contributing to potential biases [31].

In conclusion, the rising burden of EDs in South Asia reflects a complex interplay of globalization, urbanization, and shifting sociocultural norms favouring Western beauty ideals. The increasing prevalence, particularly among younger demographics and females, highlights the urgent need for targeted interventions. Limited healthcare resources, stigma, and low awareness hinder effective diagnosis and treatment. Future research should focus on longitudinal studies to understand regional risk factors better. Implementing culturally sensitive prevention strategies, integrating mental health services, and strengthening policies can help mitigate the growing impact of EDs and improve public health outcomes in the region.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the IHME and all collaborators of the Global Burden of Disease Study for providing the data for this present study.

Author contributions

P.S.: Conceptualization (lead); writing—original draft (lead); formal analysis (lead); writing—review and editing(equal); Software; Methodology. V.K.: Conceptualization (lead); writing—original draft (lead); formal analysis (lead); writing—review and editing(equal); Software; Methodology. M.N.K.: conceptualization, Software (lead); writing—review and editing (equal). L.B.: Methodology (lead); writing—review and editing (equal). S.B.: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing—original draft (supporting); Writing – review and editing (equal); K.V.: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing—original draft (supporting); Writing—review and editing (equal). L.M.: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing—original draft (supporting); Writing—review and editing (equal). R.A.: Methodology (lead); writing—review and editing (equal). G.B.: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing—original draft (supporting); Writing—review and editing (equal). M.S.: Conceptualization (lead); writing—original draft (lead); formal analysis (lead); writing—review and editing(equal). Vaibhav Jaiswal: Conceptualization; Writing—review and editing (equal). R.S.: Conceptualization; Writing—review and editing (equal). M.G.: Conceptualization; Writing—review and editing (equal). Conceptualization (supporting); Writing—original draft (supporting). S.K.: Conceptualization (lead); writing—original draft (lead). S.A.: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing—original draft. S.S: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing—review and editing. D.J.: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing—original draft. E.M.: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing –review and editing.

Funding

No funding.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Approval of the research protocol by an Institutional Reviewer Board

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Animal studies

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prakasini Satapathy, Vijay Kumara and Mahalaqua Nazli Khatib contributed equally as first authors.

References

- 1.Treasure J, Duarte TA, Schmidt U (2020) Eating disorders. Lancet 395:899–911. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30059-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eating Disorders: What You Need to Know. National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/eating-disorders. Accessed 16 Dec 2024.

- 3.Chew KK, Temples HS (2022) Adolescent eating disorders: early identification and management in primary care. J Pediatr Health Care 36:618–627. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2022.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galmiche M, Déchelotte P, Lambert G, Tavolacci MP (2019) Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Nutr 109:1402–1413. 10.1093/ajcn/nqy342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silén Y, Keski-Rahkonen A (2022) Worldwide prevalence of DSM-5 eating disorders among young people. Curr Opin Psychiatry 35:362–371. 10.1097/yco.0000000000000818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaikh MA, Kayani A (2014) Detection of eating disorders in 16–20 year old female students–perspective from Islamabad, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc 64:334–336 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Culbert KM, Sisk CL, Klump KL (2021) A narrative review of sex differences in eating disorders: is there a biological basis? Clin Ther 43:95–111. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kayano M et al (2008) Eating attitudes and body dissatisfaction in adolescents: cross-cultural study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 62:17–25. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01772.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis-Smith H et al (2020) Adaptation and validation of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire in English among urban Indian adolescents. Int J Eat Disord 54:187–202. 10.1002/eat.23431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pike KM, Dunne PE (2015) The rise of eating disorders in Asia: a review. J Eat Disord. 10.1186/s40337-015-0070-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaikh NI, Patil SS, Halli S, Ramakrishnan U, Cunningham SA (2016) Going global: Indian adolescents’ eating patterns. Public Health Nutr 19:2799–2807. 10.1017/s1368980016001087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piko BF, Patel K, Kiss H (2023) Risk of disordered eating among a sample of Indian adolescents: the role of online activity, social anxiety and social support. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Health 18:315–321. 10.1177/09731342231163391 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiang K, Kong F (2024) Passive social networking sites use and disordered eating behaviors in adolescents: the roles of upward social comparison and body dissatisfaction and its sex differences. Appetite 198:107360. 10.1016/j.appet.2024.107360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Protocol for the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors study (GBD). Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. https://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/Projects/GBD/GBD_Protocol.pdf. Accessed 20 Dec 2024.

- 15.Santomauro DF et al (2021) The hidden burden of eating disorders: an extension of estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 8:320–328. 10.1016/s2215-0366(21)00040-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joinpoint Trend Analysis Software. National Cancer Institute. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/. Accessed 20 Dec 2024.

- 17.QGIS Training Manual. QGIS. https://docs.qgis.org/3.34/en/docs/training_manual/index.html. Accessed 20 Dec 2024.

- 18.Gorrell S, Trainor C, Le Grange D (2019) The impact of urbanization on risk for eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 32:242–247. 10.1097/yco.0000000000000497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shekriladze I, Tchanturia K. In Encyclopedia of Feeding and Eating Disorders Ch. Chapter 204–1. 2016: 1–4.

- 20.Holmes S (2023) ‘It’s always that idea that everyone’s trying to look like something’: revisioning sociocultural factors in eating disorders through Photovoice. Womens Stud Int Forum 99:102753. 10.1016/j.wsif.2023.102753 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoodbhoy Z, Zahid N, Iqbal R (2015) Eating disorders in South Asia: should we be concerned? Nutr Bull 40:331–334. 10.1111/nbu.12177 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaidyanathan S, Menon V. In Eating Disorders Ch. Chapter 16–1. 2023: 1–20.

- 23.Goel NJ, Thomas B, Boutté RL, Kaur B, Mazzeo SE (2021) Body image and eating disorders among south Asian American women: what are we missing? Qual Health Res 31:2512–2527. 10.1177/10497323211036896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller MN, Pumariega AJ (2001) Culture and eating disorders: a historical and cross-cultural review. Psychiatry 64:93–110. 10.1521/psyc.64.2.93.18621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song S, Stern CM, Deitsch T, Sala M (2023) Acculturation and eating disorders: a systematic review. Eat Weight Disord. 10.1007/s40519-023-01563-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wales J, Brewin N, Raghavan R, Arcelus J (2017) Exploring barriers to South Asian help-seeking for eating disorders. Ment Health Rev J 22:40–50. 10.1108/mhrj-09-2016-0017 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bullivant B, Rhydderch S, Griffiths S, Mitchison D, Mond JM (2020) Eating disorders “mental health literacy”: a scoping review. J Ment Health 29:336–349. 10.1080/09638237.2020.1713996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koch SV et al (2022) Associations between parental socioeconomic-, family-, and sibling status and risk of eating disorders in offspring in a Danish national female cohort. Int J Eat Disord 55:1130–1142. 10.1002/eat.23771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nevonen L, Norring C (2013) Socio-economic variables and eating disorders: a comparison between patients and normal controls. Eat Weight Disord 9:279–284. 10.1007/bf03325082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaidyanathan S, Kuppili PP, Menon V (2019) Eating disorders: an overview of Indian research. Indian J Psychol Med 41:311–317. 10.4103/ijpsym.Ijpsym_461_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray CJL (2022) The global burden of disease study at 30 years. Nat Med 28:2019–2026. 10.1038/s41591-022-01990-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.