Abstract

Background

Effective antiviral therapy is lacking for most viral infections, and when available, is frequently compromised by the selection of resistance. Targeted protein degraders could provide an avenue to more effective antivirals, able to overcome the selection of resistance. The aim of this study was to determine whether adaptation of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro, also described as chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro) or non-structural protein 5 (Nsp5)) inhibitors into degraders leads to increased antiviral activity, including activity against resistant virus.

Methods

We adapted the clinically approved Mpro inhibitor nirmatrelvir into a panel of degraders. Size-matched non-degrading controls were also synthesised to discriminate degradation activity from inhibition activity. Degrader activity was confirmed using an inducible Mpro-HiBiT tag expressing cell line. Antiviral activity against both wildtype and nirmatrelvir-resistant virus was performed using infection of susceptible cell lines.

Results

Here we show three compounds, derived from nirmatrelvir and utilising VHL or IAP ubiquitin ligase recruiters, capable of degrading Mpro protein in a concentration, time and proteasome dependent fashion. These compounds also degrade nirmatrelvir-resistant mutant Mpro. The most potent of these compounds possesses enhanced antiviral activity against multiple wildtype SARS-CoV-2 strains and nirmatrelvir-resistant strains compared to non-degrading controls.

Conclusions

This work demonstrates the feasibility of generating degraders from viral protein inhibitors, and confirms that degraders possess higher antiviral potency and activity against resistant virus, compared to size matched non-degrading enzymatic inhibitors. These findings further support the development of targeted viral protein degraders as antiviral drugs, which may lead to more effective antiviral therapies for the future.

Subject terms: Antiviral agents, Structure-based drug design, SARS-CoV-2

Plain language summary

Viral infections are difficult to treat. Most antiviral drugs currently available work by blocking a viral protein that it requires to infect people or replicate. Unfortunately viruses often stop being killed by this type of drug so they can be ineffective in the long term. Targeted protein degraders are an alternative type of drug that work by removing the entire protein, rather than only blocking the protein. In this study, we made targeted protein degraders against the virus that causes COVID-19 and confirmed that they correctly degrade an important viral protein. We examined how well they can prevent the virus from replicating using infected cells. Our protein degraders were effective against virus that did not respond to drugs that block the protein, suggesting viral protein degraders could be used as more effective drugs in the future.

Pan et al. develop targeted protein degraders against SARS-CoV-2 Main protease. Using cell culture models, they show that the degraders are active against mutated protein and have better activity than size-matched inhibition-only controls against SARS-CoV-2 virus infection, including nirmatrelvir resistant SARS-CoV-2.

Introduction

Viral diseases have an enormous global impact, yet effective antiviral drugs are lacking for most viral infections. Available direct-acting antiviral therapies are often specific to a single virus and are frequently compromised by the selection of resistant viral strains. The impact of emerging coronaviruses has never been more apparent. SARS-CoV-2 and its variants are now endemic in the global population, and variant sarbecoviruses will likely continue to emerge1–3. In response to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, an unprecedented global research effort to accelerate the discovery of antiviral therapeutics was launched, which adopted largely classical antiviral approaches. These included monoclonal antibodies and ligand traps targeting the viral receptor binding or small molecule-based drugs targeting enzymatic viral proteins involved in viral replication4.

One of the most effective of these is the clinically approved small-molecule antiviral agent, nirmatrelvir, which engages the enzymatic pocket of the main viral protease Mpro (also known as chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro) or non-structural protein 5 (Nsp5)), inhibiting essential enzymatic function required for viral replication. The drug was rapidly borne from adaptation of existing Mpro inhibitors designed to treat the related SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV5,6. While effective, nirmatrelvir, like other classes of antiviral agents, has the capacity to promote selection of resistant viruses. Nirmatrelvir resistance can be conferred by mutations in the Mpro enzymatic pocket that inhibit nirmatrelvir binding7–9. Of these mutations, position E166 in Mpro appears to be a hotspot for development of resistance10,11.

One approach to address the shortcomings of conventional direct-acting antivirals is to generate targeted degraders to essential viral proteins, which could be achieved by the conversion of existing small molecule antiviral inhibitors. Targeted protein degraders (TPDs), also known as proteolysis targeting chimeras or PROTACs, are heterobifunctional molecules composed of two active ligands connected by a linker, which harness the host cells own ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway for their activity12. One ligand binds to a target protein and the second ligand binds and recruits an ubiquitin ligase to the target. The target is ubiquitinated and degraded by the host proteasome machinery thereby eliminating the protein, and the TPD is recycled and continues multiple cycles of protein degradation12. TPDs, widely investigated in the oncology field and now also being applied in the inflammatory and neurodegenerative disease fields13, have several unique features that would make them ideal antiviral drugs. They have high potency as their catalytic nature allows a ligand with moderate binding affinity to exert highly potent effects, even at sub-stoichiometric levels14. This key property may also make TPDs resilient to variant and mutated forms of target protein as they do not solely rely on high affinity binding for activity15, potentially bestowing a high barrier to antiviral resistance, as well as broad spectrum activity across viral families. Furthermore, it is anticipated that TPDs may have multiple pharmacological effects, considering that viral proteins are generally highly multifunctional, affecting both viral and host processes16–18.

The chemical synthesis of TPDs can proceed along many lines. Although there are many E3 ligase ligands in the cell, the most widely used in TPD development include cereblon, the von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) protein and the inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAP), which have multiple well characterised binding ligands available. Variations in the conjugation point within the same class of E3 ligase ligands can influence the efficiency of TPD19. Notably, an array of chemical modifications that disrupt E3 ligase binding are known, enabling synthesis of pharmacologically matched non-degrading controls15,20.

With this in mind, we synthesised a panel of Mpro targeting TPDs using a range of Mpro binders, linkers and E3 ligase ligands to determine if Mpro inhibitors could be converted into bona-fide TPDs, and if this resulted in superior antiviral effects compared to control non-degrading Mpro inhibitors which possess enzymatic inhibition only. This resulted in an antiviral TPD lead candidate, BP-198, that specifically degrades the Mpro protein of SARS-CoV-2 via the ubiquitin-proteasome system and conferred a greater antiviral effect against multiple strains of wildtype SARS-CoV-2 than the size-matched non-degrading control, BP-206. Finally, BP-198 was able to degrade Mpro encoding nirmatrelvir resistance mutations and possessed enhanced antiviral activity against nirmatrelvir-resistant SARS-CoV-2 when compared to BP-206 control.

Methods

General reagents, chemicals, kits and antibodies

Unmodified nirmatrelvir was synthesized by adapting published procedures6. Compounds BP-172, BP-174, BP-198, BP-200, BP-202 and BP-206 were prepared as described in Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Schemes S1–S7, and Supplementary Fig. 1. Doxycycline hyclate, polyethylenimine (PEI) and the chemical inhibitor CP-100356 were purchased from Sigma. DMEM + GlutaMAX, DMEM/F12 + GlutaMAX, penicillin/streptomycin, accutase, puromycin, Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail, goat anti-rabbit AF800 secondary antibody and donkey anti-mouse AF680 secondary antibody were purchased from Thermo Fisher. The Fugene HD transfection reagent, Nano-Glo® HiBiT Lytic Detection System and anti-HiBiT mouse monoclonal antibody were purchased from Promega. The ViaLight™ Plus Cell Proliferation and Cytotoxicity BioAssay Kit was purchased from Lonza. The rabbit anti-SARS-CoV-2 3C-Like Protease (Mpro) antibody (51661), rabbit anti-VHL (E3X9K) monoclonal antibody and rabbit anti-GAPDH (14C10) monoclonal antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling. The mouse anti-ubiquitin (P4D1) monoclonal antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The chemical inhibitors MG132 and TAK-243 were purchased from MedChem Express. All restriction enzymes, the Quick Ligation™ Kit, the Q5® Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit and the NEB® Stable Competent E. coli (High Efficiency) cells were purchased from New England Biolabs. All primers were supplied by IDT and all DNA plasmid amplification kits and gel/PCR purification kits were supplied by Macherey-Nagel. CP-100356 was purchased from MedChem Express.

Cell lines and media

HEK293T cells (ATCC) were maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS. LVX HEK Mpro-HiBiT reporter cell lines were cultured in the presence of 2 µg/mL puromycin. VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells (CellBank Australia, JCRB) were maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS and geneticin. Calu-3 cells (ATCC) were maintained in DMEM/F12 with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2. All cell lines routinely tested negative for mycoplasma contamination, authentication was performed by distributor.

Cloning of the Mpro-HiBiT into the pLVX-TetON-PuroR inducible lentiviral vector and mutagenesis

The sequence for SARS-CoV2 3CL protease (Mpro – SARS-CoV-2/Australia/Vic/01/20 strain) was conjugated to a HiBiT tag sequence at the 3′ (C-terminal) end in silco and then synthesised in a pCDNA3.1(+) vector flanked by unique EcoRI/BamHI restriction sites by Genscript. After excising the sequence by restriction digest with EcoRI/BamHI and gel purification, it was ligated into the pLVX-TetOne-PuroR doxycycline inducible 2nd generation lentiviral vector (Takeda) using a Quick Ligation™ Kit and transformed into NEBStable chemically competent E.coli. Clones with successful ligations were detected by miniprep plasmid purification and EcoRI/BamHI digest followed by agarose gel electrophoresis to visualise the liberated insert. After maxiprep of a sequence verified clone, the final construct, pLVX-TetOne-Mpro HiBiT-PuroR was then again verified by sequencing and by restriction digest. To introduce the mutations within Mpro used in this study, the plasmid was first subject to E166V mutagenesis before then introducing any secondary mutations with the primers outlined below using the NEB Q5 site change mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The final mutated constructs were verified by sequencing.

Mpro E166Vmut For: 5′-AGTTGGTAATACCATATGGTGCATG-3′; Mpro E166Vmut Rev: 5′-GGAGTTCATGCTGGCACA-3′. Mpro T21I mut For: 5′-TGTACCACAAATTACTTGTAC-3′; Mpro T21I mut Rev: 5′-ACTACACTTAACGGTCTTTG-3′. Mpro L50F mut For: 5′-TTAGGGTTAAACATGTCTTCAG-3′; Mpro L50F mut Rev: 5′-TTATGAAGATTTACTCATTCG-3′.

Generation of the HEK293T LVX Mpro-HiBiT reporter cell line

Transfection mixes containing pLVX-TetOne-Mpro HiBiT-PuroR (either wildtype Mpro or mutated Mpro) along with the 2nd generation lentiviral packaging plasmids psPAX2 (a gift from Prof. Didier Trono, Addgene #12260) and pMDG.2 (a gift from Prof. Didier Trono, Addgene #12259) in StemPro medium were formed with PEI at a 3:1 (PEI:DNA) ratio for 20 min before adding to 6 × 106 HEK293T cells (wt or VHL KO background) in 100 mm2 dishes. After an overnight incubation at 37 °C, 5% CO2, the media containing PEI was removed and fresh 10 mL medium added and incubation at 37 °C, 5% CO2 resumed. At 24 h time points, the medium containing virus was extracted and filtered 0.45 um with fresh medium being added for a total of three rounds of harvesting. The viral harvests were pooled and subsequently 10 mL of virus supernatant was added to freshly plated HEK293T cells along with 5 μg/mL polybrene and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After an overnight transduction, the viral supernatant was removed and fresh antibiotic-free medium was added before resuming incubation at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 48 h before 2 µg/mL of puromycin was added to select for transductants. After one week of selection, the cell line was expanded and utilised in subsequent assays.

Generation of the VHL knock out HEK293T cell line

The sgRNA sequence for targeting VHL21 was ligated into the pX458 vector (a gift from Prof. Feng Zhang, Addgene #48138) using the unique BbsI insertion site by Quick Ligation™ Kit and miniprepped with DNA clones screened by sequencing for a successful sgRNA insert. Once discovered, the plasmid from a sequence verified clone was then maxiprepped and again sequence verified. The plasmid was then transfected into HEK293T cells using FugeneHD at ratio of 3:1 (Fugene:DNA) and, after 3 days of expansion at 37 °C, 5% CO2, cells were analysed on an Aria flow cytometer and sorted on eGFP positive expression to purify cells positive for the vector. The knock-out of VHL was confirmed by western blotting using an anti-VHL specific rabbit monoclonal antibody.

Nano-Glo® HiBiT lytic detection assay

HEK293T LVX Mpro-HiBiT reporter cells were plated in 96-well flat bottom white opaque plates at 10,000 cells per well in 50 μL medium overnight at 37 °C, 5% CO2. The next day, 50 μL/well of doxycycline (at the desired final concentration) was added to induce Mpro-HiBiT protein expression and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After 24 h of induction, 100 μL/well of drug treatment or control was added to the desired concentration and incubated for the desired time at 37 °C, 5% CO2. At the desired time point, 130 μL of media was extracted from the wells and 50 μL/well of Nano-Glo® HiBiT Lytic Detection working solution was added. After orbital shaking for 1 min to mix, the plate was incubated for 20 min at room temperature before reading the luminescence signal using a FluoStar Optima plate scanner. Data acquired as raw luminescence reads per well.

Vialight proliferation assay

HEK293T LVX Mpro-HiBiT reporter cells were plated and treated as stipulated for the HiBiT assay. At time of testing, 170 μL of media was removed from wells and 50 μL of lysis reagent was added in followed by 1 min of orbital shaking at 500 rpm and another 5 min incubation to ensure complete lysis. Vialight AMR reagent was then added at 50 μL per well followed by orbital shaking at 500 rpm for 1 min to mix. The plate was incubated for 20 min at room temperature before reading the luminescence signal using a FluoStar Optima plate scanner. Data was acquired as raw luminescence reads per well.

Western blot

Cells were harvested using Accutase and centrifuged at 500 x g for 5 min. The supernatants were removed and cells washed in 1 mL of ice-cold PBS and transferred to cold centrifuge tubes. After centrifugation for 5 min at 500 x g at 4 °C, the supernatant was removed and cell pellets lysed at 15 μL/million cells in NP-40 lysis buffer containing Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. After trituration and vortexing for 10 s, lysates were clarified at 21,000 x g for 20 min at 4 °C after which clear supernatants were extracted and subjected to BCA assay for protein quantitation.

Fifty (50) µg of protein was then run on 4-12% gradient bis-tris NuPage SDS-PAGE gels at 150 V for 90 min after which gels were transferred to PVDF membranes using an iBlot apparatus set to Program 3 for 7 min. After blocking in intercept buffer for 1 h, membranes were probed overnight at 4 °C with 1:750 anti-Mpro rabbit polyclonal antibody and 1:1000 anti-HiBiT mouse monoclonal antibody diluted in intercept buffer + 0.1% Tween-20. Membranes were washed three times in TBS + 0.1% Tween-20 after which secondary anti-rabbit AF800 and anti-mouse AF680 secondary antibodies, diluted 1:10,000 in intercept buffer + 0.1% Tween-20, were added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After a final three washes, membranes were scanned on the Licor Odyssey Infrared scanning system. Membranes were subsequently re-probed using 1:10,000 anti-GAPDH rabbit monoclonal antibody for loading controls.

Immunoprecipitation (IP)

Cells were harvested and washed as in western blotting and then lysed in NP-40 lysis buffer containing Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Lysates were clarified and quantitated as in western blotting. For each IP, 1.4 mg of total protein was precleared with magnetic protein G beads for 1 h after which cleared lysates were mixed with 2 µg of anti-HiBiT tag mouse mAb and rotated for 2 h at 4 °C to mix and bind target. Next, 20 μL of protein G magnetic beads was added per IP and incubated overnight at 4 °C with rotation. The next day, IPs were washed 5 times in 1 mL ice cold NP-40 buffer and then mixed with reducing LDS sample buffer and boiled at 95 °C for 10 min to liberate protein from the beads. The sample was separated from the beads on a magnetic rack and loaded onto a 4–12% gradient bis-tris SDS-PAGE gel after which western blotting proceeded as above using 1:750 anti-Mpro rabbit polyclonal antibody and 1:500 anti-pan Ub mouse monoclonal antibody.

Mpro FRET inhibition assay

The SARS-CoV-2 Mpro FRET assay measures the activity of full-length SARS-CoV-2 Mpro to cleave an internally quenched fluorogenic peptide substrate DABCYL-KTSAVLQSGFRKME-EDANS. The fluorescence of the cleaved EDANS peptide (excitation 340 nm/ emission 480 nm) was measured using a fluorescence intensity protocol on an Envision Plate reader (Perkin Elmer). The fluorescent signal is reduced in the presence of inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. The assay was performed in Greiner black 384-well non-binding microplates. SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (a final concentration of 10 nM) was pre-incubated with test compound at different concentrations for 15 min at room temperature in the assay buffer (24 mM HEPES (pH 6.5), 120 mM NaCl, 0.012% TX-100, 1.2 mM BSA, and 1.2 mM DTT). The peptide substrate (final concentration 20 μM) was then added to the mixture, which was incubated for 3 h at room temperature before quenching with 70 mM citric acid. The % activity was calculated based on control wells containing no compound (0 % inhibition/100 % activity) and a control compound (GC-376, 100 % inhibition/0 % activity).

RTCA-based antiviral assay

RTCA E-Plate View 96-well plates (Agilent) were seeded with VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells at 10,000 cells/well in DMEM media, or Calu-3 cells at 60,000 cells per well in DMEM/F12 media, and cultured in the xCELLigence RTCA eSight instrument (Agilent) at 37 °C, 5% CO2. At 24 h post-seed, duplicate wells were pre-treated with compounds at indicated doses for 2 h prior to addition of SARS-CoV-2 ancestral strain (SARS-CoV-2/Australia/Vic/01/20) at MOI 1. At 2 h post-inoculation, cell culture supernatant was aspirated and replaced with fresh media containing compounds at the indicated doses. For antiviral experiments performed in VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells, media was supplemented with efflux inhibitor CP-100356 (2 μM). Cell impedance was measured every 15 min and cells photographed every 40 min over a 120 h timeframe. Cell impedance values of cells treated with fixed dose TPD versus NDMI controls were used to compare antiviral efficacy. Time-dependant IC50 values were calculated based on standardised cell impedance data taken at fixed timepoints, using Graphpad Prism software. The time to reach 50% reduction in cell impedance (CIT50) was determined from normalised cell index data. Images taken by the RTCA eSight instrument were used to visually confirm the presence of viral CPE.

Yield-based antiviral assay

Calu-3 or VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cultures were pre-treated with compounds at the indicated doses for 2 h prior to infection with Omicron strain SARS-CoV-2/Australia/Vic/61194 (BA.5) at MOI 0.01 at 37 °C for 1 h. Viral inoculum was aspirated and cells were washed four times with culture media before replenishment with media containing each compound at the indicated doses, and continuing incubation at 37 °C, 5% CO2. VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells were also supplemented with efflux inhibitor CP-100356 (2 μM). At 24 h post-infection, cell culture supernatants were collected, clarified (6000 x g, 10 min, 4 °C) and stored at −80 °C. Infectious titer of each supernatant was determined by serial 1:2 dilution of 8 replicates onto VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells in 96-well plates, and cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for five days. The presence of cytopathic effect was evaluated using light microscopy, and tissue culture infectious dose 50% (TCID50) was calculated using the Spearman-Kärber method. Each experiment was performed in duplicate, on separate occasions. Viral yield data was adjusted relative to DMSO control and used to calculate IC50 dose via non-linear regression using TableCurve 2D software (Symantec).

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from clarified (6000 x g, 10 min, 4 °C) cell culture supernatant using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and reverse transcription performed using the BioLine SensiFAST cDNA kit (Bioline, London, United Kingdom)22, alongside serially diluted cell culture supernatant to be used as a standard curve. A real-time PCR assay targeting the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp)/helicase genes was then performed using Precision FAST qPCR Master Mix with LowRox (Primer Design Ltd), forward primer 5′- CGCATACAGTCTTRCAGGCT-3′, reverse primer 5′-GTGTGATGTTGAWATGACATGGTC-3′, and probe 5′- FAM-TTAAGATGTGGTGCTTGCATACGTAGAC-3. Amplification was performed using an ABI 7500 FAST real-time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems) at: 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 45 PCR cycles of 95 °C for 5 sec and 55 °C for 30 sec23. Samples were tested in duplicate with the mean cycle threshold (Ct) value reported. Relative change in viral copies for each sample was extrapolated from the standard curve included in the assay by linear regression, adjusted relative to DMSO control, and IC50 calculated using TableCurve 2D software (Symantec).

Nirmatrelvir resistant antiviral assay

Susceptibility of a nirmatrelvir-resistant SARS-CoV-2 delta strain to BP-198 and BP-206 was determined using a focus reduction assay in VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells (JCRB)9, with the inclusion of efflux inhibitor CP-100356 (2 μM) in cell culture supernatant.

VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells in 96-well plates were infected with SARS-CoV-2 Delta (B.1.617.2) wildtype strain, or SARS-CoV-2 Delta (E166V/L50F) at approximately 400 focus-forming units per well, at 37 °C for 1 h. Inoculum was removed and replaced with culture medium containing serial dilutions of each compound in 1 % Methyl Cellulose (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation), cells incubated for a further 18 h prior to formalin fixation, staining with a SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein antibody at 0.2 ug/mL (clone N45, TAUNS Laboratories, Inc., Japan) and detection using an HRP-labelled goat anti-mouse antibody at 1:1000 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.) and TrueBlue substrate (SeraCare Life Sciences). Focus number was quantified using an Immunospot S6 Analyzer (Cellular Technology), and IC50 calculated using GraphPad Prism 9.3.0 software.

Statistics and reproducibility

GraphPad Prism (v10.1.2) was used for all data processing and statistical analysis if required. The details of the type of statistical test deployed, P-value of significance obtained and the number of independent replicates analysed for each set of data in this study are documented in each relevant section. A one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post multi-comparison test and single pooled variance was used to analyse pairwise data whereas a two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multi-parametric test and single pooled variance was used to compare differences between time-points and treatment groups. A non-linear regression model was used to fit response curves on all viral titration data. A P < 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Synthesis and identification of Mpro targeted TPDs based on nirmatrelvir modification

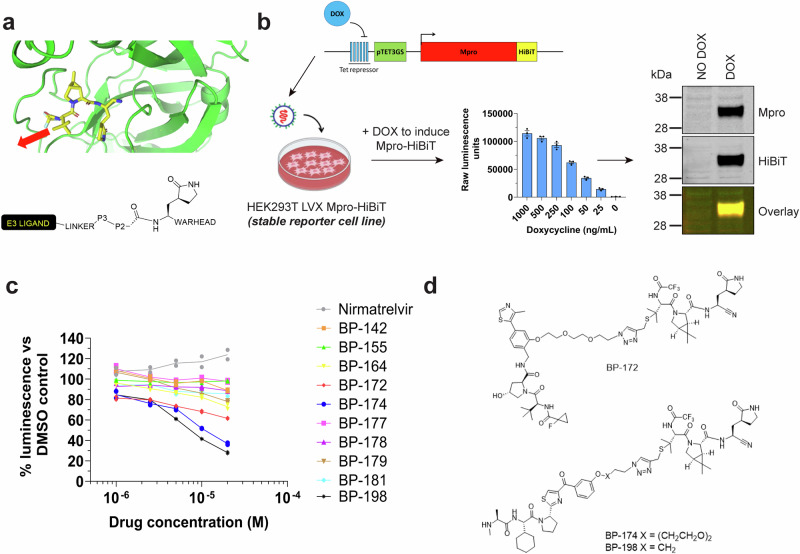

A variety of substrate-mimetic Mpro inhibitors have been co-crystallised with Mpro including PF-00835231 (PDB: 6XHM)5, GC376 (PDB: 6WTJ)24, UAWJ248 (PDB: 6XBI)25, and most-recently nirmatrelvir (PDB: 7RFW)6. When superimposed it is apparent that they have a close topographic alignment associated with P1 and P2 pocket binding but that they diverge in terms of chemical structure and importantly for TPD design, in the likely projected vectors for linker attachment and conjugation to E3 ligase ligands (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1. Targeted protein degrader (TPD) design, screening assay design and candidate hit identification.

a Crystal structure of nirmatrelvir in congress with the Mpro catalytic pocket (generated with PyMOL software using publicly available data PDB: 7RFW6). The solvent accessible P3 motif for linker conjugation is indicated by the red arrow. The schematic below outlines the attachment strategy for linker and recruitment motif to the P3 motif of the substrate-mimetic class of Mpro inhibitors. b Schematic for Mpro-HiBiT doxycycline (DOX) inducible reporter cell-based assay construction and verification used in this study (components of this figure were created with BioRender.com). c HiBiT reporter assay results for screening of multiple nirmatrelvir-based TPD candidates by HEK293T LVX Mpro-HiBiT assay after 24 h of treatment. Data is presented as the % luminescence reads of the matched DMSO control at each concentration. d Structures of the TPD candidates identified from the nirmatrelvir-based HiBiT screen in (c). All experiments were completed to at least n = 2.

We prepared an initial suite of 33 potential TPDs, with variations in Mpro-binding pharmacophores, chemical linkers and E3 ligase targeting ligands (cereblon, VHL and IAP) (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1). The compounds were then tested as Mpro inhibitors using a FRET assay5 to confirm that the binary interaction was conserved. The parental compounds PF-00835231 and nirmatrelvir were shown to exhibit IC50 values of 4.4 nM and 7.3 nM, respectively, which is comparable to values reported in the literature5,6. The nirmatrelvir-based TPDs were all highly potent Mpro binders with all compounds inhibiting Mpro activity in the very low nM range, indicating the tert-butyl moiety of nirmatrelvir was an ideal conjugation point26. Other combinations of Mpro ligand, linker and E3 ligase ligand gave diverse impacts upon binary interactions (Supplementary Table 1). For other compounds, the nitrile-containing analogues suffered a considerable loss in affinities with IC50 values in the µM range (Supplementary Table 1).

To screen the Mpro degradation activity of each candidate, we developed a quantitative reporter assay based upon doxycycline (DOX) inducible Mpro-HiBiT tag fusion in HEK293T cells where Mpro-HiBiT could be quantitated within cell lysates using luminescence-based detection (Fig. 1b). Western blot verification of the protein produced after DOX induction demonstrated a single clean 38 kDa band which was reactive with Mpro and HiBiT tag antibodies (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 3, confirming correct and stable expression of HiBiT-tagged Mpro protein. Screening assays were conducted over 24 h with test compound titration from 20 µM to 500 nM followed by luminescent detection of Mpro-HiBiT protein. Most candidates showed moderate reduction of Mpro-HiBiT signal (Supplementary Table 1); however, three candidates stood out in reducing Mpro-HiBiT levels in a concentration-dependent manner – BP-172, BP-174 and BP-198 (Fig. 1c). The compounds all included the nirmatrelvir pharmacophore and BP-172 utilised the VH10119 recruitment motif whilst BP-174 and BP-198 utilised the IAP LCL-16120 recruitment motif. BP-172 and BP-174 contained a PEG2 based triazolyl linker whilst BP-198 contained a shorter alkyl linker (Fig. 1d). It was apparent that the linker selection was important as BP-198 analogues with longer PEG linkers had poor activity and it was notable that BP-155 and BP-181, both pomalidomide-derived cereblon targeting ligands, and VH032-derived VHL recruiters BP-142, 177 and 178 showed poor activity by comparison (Supplementary Table 1).

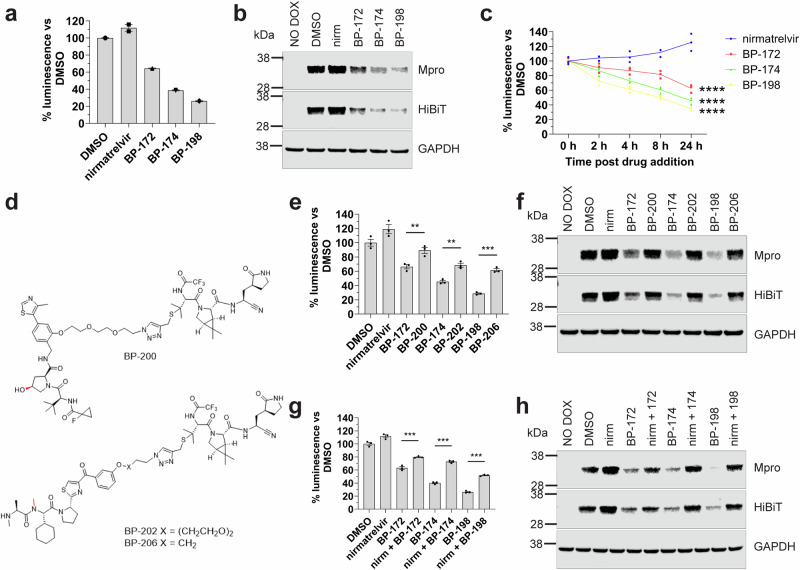

BP-172, BP-174 and BP-198 degrade Mpro in a time dependent manner

A more detailed evaluation of the three best compounds at a fixed dose of 20 µM confirmed significant degradation of Mpro-HiBiT (P < 0.0001 vs DMSO controls) with a maximum reduction of 72% over 24 h observed for the best candidate BP-198 (Fig. 2a). This reduction was not due to loss of cell viability as testing of parallel assays using Vialight technology showed no loss of cell number following drug administration (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Western blot assays performed in parallel showed that the degree of Mpro-HiBiT reduction mirrored that of the HiBiT luminescence assay results compared to DMSO controls (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 3). As bona-fide TPDs are capable of cumulative degradation of target over time, we sought to confirm loss of target over increasing times of treatment. At 20 µM, each TPD registered an initial loss of Mpro-HiBiT protein at 2 h post treatment followed by a steady decline up to 24 h post treatment suggestive of a linear kinetic pattern of degradation, whereas cells treated with unmodified nirmatrelvir demonstrated a steady increase in Mpro-HiBiT, indicating that unmodified nirmatrelvir may stabilise Mpro at high concentrations (Fig. 2c). Together, these results confirm that BP-172, BP-174 and BP-198 are capable of significant and specific reduction of Mpro-HiBiT protein levels in a time dependent manner.

Fig. 2. TPDs are capable of degrading wt Mpro by binding Mpro and recruiting the ubiquitin ligase machinery for Mpro degradation.

a HiBiT detection results and (b) western blot verification results for singular TPD candidate testing at 20 μM for 24 h in the HEK293T LVX Mpro-HiBiT reporter cells. c HiBiT detection results for TPD treated HEK293T Mpro-HiBiT reporter cells over multiple time points post 20 μM drug addition. **** indicates P < 0.0001 vs nirmatrelvir by multi-parametric two-way ANOVA (d) chemical structures of the non-degrading Mpro inhibitors (NDMIs) BP-200, BP-202 and BP-206 to compare to BP-172, BP-174 and BP-198 in this study, respectively. The chemical modifications which inactive the ubiquitin-ligase recruiter ligand domain are highlighted in red. e HiBiT detection results and (f) corresponding western blot results for testing of TPD compared to NDMI controls at 20 μM for 24 h in the HEK293T LVX Mpro-HiBiT reporter cells. g HiBiT detection results and (h) western blot results for singular TPD testing at 20 μM alone or in competition with 20 μM nirmatrelvir for 24 h in the HEK293T LVX Mpro-HiBiT reporter cells. All HiBiT assay results in (a, e, g) are presented as % luminescence vs DMSO controls ± S.E.M. *** indicates P < 0.0001, ** indicates P < 0.001 significant difference to DMSO controls by one-way ANOVA. All experiments were completed to at least n = 2 with experiments completed to n = 3 for statistical analysis.

BP-172, BP-174 and BP-198 specifically engage Mpro and recruit ubiquitin ligase machinery in order to degrade Mpro

TPDs rely on the ubiquitin proteasome system for target protein degradation. Using immunoprecipitation of Mpro-HiBiT following inhibition of the proteasome by MG132 after 4 h of BP-172, BP-174 or BP-198 treatment, we observed evidence of ubiquitination of Mpro-HiBiT following treatment with the more effective TPDs BP-174 and BP-198 (Supplementary Fig. 4b). However, when we attempted to interrogate this mechanism further using standard administration of MG132 or TAK-243 (to inhibit the ubiquitin activating enzyme to prevent ubiquitination of the target) along with TPD for a longer 24 h time, we found these drugs negatively interfered with either the transgene expression and/or cell viability at the projected effective dose for these agents (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Therefore, their use in interrogating the mechanism of TPD action was unsuitable in our reporter system.

To overcome this limitation, we utilised non-degrading Mpro inhibitor (NDMI) controls which are pharmacologically altered variants of each TPD candidate, where the E3 ligase recruitment motif was precisely modified to prevent binding to their E3-ligases, controlling for molecule size and membrane permeability, whilst retaining activity of the nirmatrelvir binding ligand. For BP-172, we introduced a cis-hydroxyl group into the VH101 motif known to disrupt engagement with the VHL E3-ligase preventing ubiquitination27. For BP-174 and BP-198 we introduced an N-methyl “bump” R-group in the LCL-161 ligand known to inhibit binding and recruitment of the IAP E3-ligases20 (Fig. 2d). If our TPDs were utilising E3-ligases to degrade Mpro-HiBiT, the use of these NDMI controls should rescue Mpro-HiBiT protein vs our TPDs alone. After 24 h of treatment (Fig. 2e), we confirmed that the NDMI variants of our TPDs resulted in a significant rescue of Mpro-HiBiT protein (BP-172 vs BP-200, 66% vs 89% P < 0.001; BP-174 vs BP-202, 45% vs 69%, P < 0.0001 and BP-198 vs BP-206, 28% vs 62%, P < 0.0001). Again, we confirmed this result by western blot where we observed a strong rebound of Mpro-HiBiT protein expression to levels similar to the DMSO control in all NDMI compounds vs their TPD counterparts (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Fig. 3).

Next, in order to prove that BP-172, BP-174 and BP-198 specifically bind to Mpro, resulting in its ubiquitination and degradation, we conducted competition experiments with equimolar amounts of free unmodified nirmatrelvir to compete for the Mpro binding site. Such a competition assay should enable rescue of Mpro-HiBiT levels compared to treatment with our TPDs alone. As shown in Fig. 2g, after 24 h of competition, we observed a significant rescue of Mpro-HiBiT levels by HiBiT assay for all TPD candidates when free unmodified nirmatrelvir was added (63% vs 79% for BP-172, P < 0.0001; 40% vs 72% for BP-174, P < 0.0001 and 26% vs 52% for BP-198, P < 0.0001). Western blots to verify these results demonstrated marked rescue of Mpro-HiBiT protein following competition of the TPDs with free unmodified nirmatrelvir for all candidates (Fig. 2h, Supplementary Fig. 3). Hence, BP-172, BP-174 and BP-198 all specifically engage Mpro-HiBiT target in the cell in order to initiate its degradation.

To further confirm VHL-dependency of BP-172 activity, we generated a genetic VHL knockout (KO) HEK Mpro-HiBiT reporter cell line to test the utilisation of VHL recruitment for BP-172 action. Our analysis shows that when BP-172 and BP-174 (which does not utilise VHL) were administered in the wildtype HEK background, both were capable of degrading Mpro-HiBiT as expected by HiBiT assay (Supplementary Fig. 4d) and western blots (Supplementary Fig. 4e). However, when tested in the VHL KO cellular background, the ability of BP-172 to degrade Mpro-HiBiT was almost completely abolished (wt HEK 51% vs VHL KO HEK 81%, P < 0.0001) whereas the activity of BP-174 was unaffected (wt HEK 49% vs VHL KO HEK 47%, n.s.) (Supplementary Fig. 4d, e), confirming that degradation activity of BP-172 is dependent on VHL. Due to the numerous redundant IAP family members capable of actioning BP-174 and BP-198 activity, we did not attempt to generate a genetic IAP KO cell line for confirmatory studies.

Overall, these results provide evidence that our TPD candidates specifically engage Mpro and recruit the intended VHL or IAP E3-ligases to ubiquitinate and degrade Mpro-HiBiT protein.

BP-174 and BP-198 are effective antivirals with enhanced antiviral effects against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro

Antiviral activity of TPDs and their NDMI controls were compared to distinguish effects related to Mpro degradation from the inherent enzymatic inhibition of Mpro present in both molecules. Initial screens were performed using real time cell analysis (RTCA) of parental strain SARS-CoV-2/Australia/Vic/01/2022 (for simplicity, this strain will be referred to as SARS-CoV-2 (VIC-01)). SARS-CoV-2 (VIC-01)-infected VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells were treated with either TPD or NDMI at equivalent doses and cultured for up to 120 h. Treatment of infected cells with lead candidates BP-198 and BP-172 at 10 µM, 5 µM and 2.5 µM doses resulted in reduced viral cytopathic effect (CPE), measurable as a higher cell index, than their NDMI controls over the course of the assay (Fig. 3a, b) with no detectable cytotoxicity (Supplementary Fig. 5a), the presence of CPE confirmed via visual inspection of RTCA cell images taken across the course of the experiment (Supplementary Fig. 5b). At 1.25 µM and lower doses, the TPDs exhibited comparable antiviral profiles as their NDMI controls (Fig. 3a, b), agreeing with a concentration window where degradation of Mpro begins to take effect (Fig. 1c). To confirm these results in human cells, RTCA analysis was performed in Calu-3 cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 (VIC-01) and treated with 10 μM of each TPD and NDMI control. A higher overall cell index and increase in CIT50 was observed for both BP-174 vs BP-202 (Fig. 3c) and BP-198 vs BP-206 (Fig. 3d). The data was supported by visualisation of CPE (Supplementary Fig. 5c), confirming findings in the VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cell line that the TPDs provide enhanced antiviral effects over their NDMI controls.

Fig. 3. Enhanced real time antiviral activity is observed for TPDs compared to NDMI controls in multiple SARS-CoV-2 cellular infection systems.

a xCELLigence real time cellular response profiles of VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cell model of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the presence of titrated TPD BP-174 vs BP-202 control or (b) BP-198 vs BP-206 control. Dashed lines indicate the TPD and solid lines indicate the matched NDMI control drug. The tables underneath each profile document the time-dependent IC50 in μM ± S.E.M for each drug calculated at several time points post infection. The fold difference in IC50 is the TPD compared to its NDMI control. c xCELLigence real time cellular response profiles of Calu-3 cell model of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the presence of 10 μM TPD BP-174 vs BP-202 control or (d) BP-198 vs BP-206 control. Dashed lines indicate the TPD and solid lines indicate the matched NDMI control. Profiles of uninfected cells treated with each compound at 10 μM are included, confirming lack of toxicity of these compounds. e Analysis of xCELLigence profiles to determine the time taken to reach a half cellular index (CIT50) for each drug at each concentration in VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cell line. Data is graphed as CIT50 for each drug. f Analysis of the titer of progeny Omicron BA.5 virus within supernatants after 24 h of treatment with serial dilutions of TPD BP-198 or BP-206 control. Data is graphed as the viral titer as a percentage of the DMSO control. For each drug response, the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) was calculated ± S.E.M. g Quantitative RT-PCR detection of the Omicron BA.5 viral genome copy number through detection of the RdRp/helicase genes. Data is presented as the amount of viral copies as a % of the DMSO control. All experiments were completed to at least n = 2.

As a kinetic measure of antiviral potency, time-dependent IC50 was calculated based on standardised cell impedance data, taken every 15 min across the course of each experiment shown in Fig. 3a, b. The complete data set is provided (Supplementary Fig. 5d) but, for clarity, IC50 calculated at 10 hourly intervals, as well as the fold reduction in IC50, or potency gain, observed between each TPD and their NDMI counterpart are described in Tables 1, 2. Both TPDs have comparable potency as their NDMI counterparts when measured up to 30 hpi, which progressively increases up to 70 hpi, when BP-174 and BP-198 reach 1.6- and 2.6-fold higher potency than their NDMI counterparts, respectively. This suggests that the TPDs may have a longer-lasting antiviral effect. Another quantitative measure specific for RTCA analysis, is the time taken to reach a 50% reduction in cell index (CIT50)28,29, a longer CIT50 representing enhanced antiviral activity. This analysis showed that both BP-174 and BP-198 had a progressively increasing CIT50 up to the highest 10 µM concentration which was superior to that observed for their NDMI counterparts (Fig. 3e), further confirming enhanced antiviral efficacy of TPD over NDMI control.

Table 1.

Time-dependent IC50 (μM) for TPD BP-174 and NDMI BP-202 calculated at several time points post infection, including the fold change in IC50 for BP-174 relative to BP-202

| Time post infection (hours) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | |

| Drug IC50 (uM) | |||||

| BP-174 | 0.41 | 1.54 | 4.2 | 6.16 | 8.3 |

| BP-202 | 0.41 | 1.69 | 5.76 | 8.73 | 13.47 |

| Fold reduction in IC50 | 1 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

Table 2.

Time-dependent IC50 (μM) for TPD BP-198 and NDMI BP-206 calculated at several time points post infection, including the fold change in IC50 for BP-198 relative to BP-206

| Time post infection (hours) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | |

| Drug IC50 (uM) | |||||

| BP-198 | 0.78 | 2.09 | 3.7 | 5.8 | 6.93 |

| BP-206 | 0.7 | 2.38 | 7.03 | 12.75 | 17.81 |

| Fold reduction in IC50 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.6 |

We then assessed our best TPD candidate, BP-198, and its matched NDMI control, BP-206, for their effects on viral yield of a more recent and widely circulating Omicron lineage SARS-CoV-2/VIC/61194 (BA.5) (this strain will be described as SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.5) in human Calu-3 cells. Cells were infected at MOI 0.001 after which the virus was removed and culture continued in the presence of BP-198 or BP-206 at multiple titrated doses. After 24 h, the infectious titer of progeny virus within supernatants was measured by endpoint dilution and calculation of 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) using the Spearman-Kärber method30, and standardised viral titer used to determine IC50. No toxicity was detected in Calu-3 cells at the dose range tested (Supplementary Fig. 5e).

In this model, BP-198 had a 2.1-fold higher potency than BP-206 (IC50 11.8 μM vs 24.6 μM respectively) (Fig. 3f) against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.5 which was similar to the advantage observed against the SARS-CoV-2 (VIC-01) parental strain from our RTCA analyses shown in Fig. 3b. Confirmation of enhanced antiviral activity of BP-198 over BP-206 came from quantitative RT-PCR detection of released viral genomes (Fig. 3g) where BP-198 again had a higher potency in reducing viral genome number compared to BP-206 (IC50 11.4 μM vs >20 μM respectively), correlating well with the infectious titer results shown in Fig. 3f. Similar to the RTCA findings, the enhanced activity of BP-198 occurred at the doses where effective degradation is observed in our Mpro-HiBiT model (Fig. 1c), and is invariably higher or equivalent to BP-206, never lower.

Together, these findings show that our TPDs have enhanced antiviral activity than their NDMI counterparts, against both SARS-CoV-2 parental and Omicron BA.5 strains confirming that the additional degradation of Mpro confers greater antiviral activity than enzymatic inhibition of Mpro alone.

TPDs are effective in degrading Mpro harbouring nirmatrelvir resistance mutations

One of the predicted powers of TPD-based antivirals over traditional antivirals is the ability to overcome antiviral resistance, as TPDs do not require high affinity binding for efficacy. To determine if our TPD panel could degrade nirmatrelvir-resistant Mpro, we introduced several published nirmatrelvir-resistant mutations E166V, E166V + T21I and E166V + L50F8, into our Mpro-HiBiT expression system, and generated reporter cell lines harbouring these mutated proteins. Titration of TPDs BP-172, BP-174 and BP-198 vs these three nirmatrelvir-resistant Mpro forms confirmed the TPDs were still capable of degrading mutant Mpro-HiBiT target, shown using HiBiT assay (Fig. 4a) and western blotting (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 3). The loss of activity for the TPDs was less than a 2-fold reduction in capability for all TPDs at the 20 µM dose compared to the 100-218-fold loss of binding activity published for nirmatrelvir7. Hence, TPDs of Mpro are capable of effectively degrading nirmatrelvir-resistant forms of Mpro.

Fig. 4. Enhanced antiviral activity is observed for TPDs compared to NDMI controls in nirmatrelvir-resistant SARS-CoV-2 variants harbouring Mpro mutations.

a HiBiT detection results and (b) western blot verification results for singular TPD testing at 20 μM for 24 h in the HEK293T LVX Mpro-HiBiT reporter cells harbouring either wtMpro or mutated variants of Mpro (E166V, E166V + T21I and E166V + L50F). HiBiT assay results are presented as % luminescence vs DMSO controls. c, d Focus reduction assays in Calu-3 cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant harbouring either wildtype Mpro (c) or Mpro containing nirmatrelvir-resistant mutations E166V + L50F (d) and treated with increasing doses of either nirmatrelvir, the TPD BP-198 or the NDMI BP-206 control. Data is presented as the number of foci per dose of drug as a % of the DMSO control. The IC50 dose response for each drug was quantitated by linear regression analysis ± 95% CI. ** indicates a P = 0.0019 significant difference between BP-198 and BP-206 by multi-parametric two-way ANOVA. n.s = not significant. All experiments were completed to at least n = 2 with experiments completed to n = 3 for statistical analysis.

BP-198 is effective against nirmatrelvir-resistant SARS-CoV-2 in vitro

Next, we examined antiviral activity against a nirmatrelvir-resistant recombinant virus in an infection model, where a wildtype SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) clone (henceforth described as SARS-CoV-2 Delta (WT)) was modified using a BAC-based reverse genetics system to introduce Mpro mutations L50F/E166V. This clone (SARS-CoV-2_Delta (L50F/E166V)) was previously confirmed to possess a high level of resistance to nirmatrelvir in vitro, associated with reduced viral fitness9.

To determine whether TPDs maintain activity against this nirmatrelvir resistant virus, our best TPD candidate BP-198 and NDMI control BP-206 were evaluated for activity against SARS-CoV-2 Delta (WT), and SARS-CoV-2 Delta (L50F/E166V) infection in VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells using a focus reduction assay9.

No significant difference in antiviral activity was detected between BP-198 and BP-206 against SARS-CoV-2 Delta (WT) (Fig. 4c); however, when antiviral activity was assessed against the nirmatrelvir-resistant (L50F/E166V) strain, BP-198 again exhibited 2.7-fold higher potency than BP-206 (IC50 12.7 μM vs 34.6 μM respectively, P = 0.0019) (Fig. 4d). We next assessed the degree of resistance to each compound conferred by the L50F/E166V strain by comparing activities of each compound against the WT and L50F/E166V strains.

Under these conditions, SARS-CoV-2 Delta (L50F/E166V) exhibited a 261-fold reduction in susceptibility to unmodified nirmatrelvir compared to wild type SARS-CoV-2 Delta (IC50 18.3 μM vs 0.07 μM, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 6) confirming the high level of resistance conferred by these mutations. In comparison, BP-198 only had a 25-fold reduction in activity (0.5 µM vs 12.7 µM, respectively), much lower than the 261-fold reduction in activity observed for unmodified nirmatrelvir, and 75-fold reduction observed for the NDMI control BP-206. These findings confirm that BP-198 has enhanced antiviral activity over NDMI control against nirmatrelvir resistant virus.

Discussion

This study provides important confirmation that inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro can be adapted into TPDs leading to antiviral effects that go beyond that shown by enzymatic inhibition alone, and importantly are effective against mutant forms of target which are highly resistant to the parental inhibitor.

The development of the robust quantitative cell-based assay for recombinantly expressed Mpro described here was a critical component of the screening cascade to discover these TPDs. We were able to rapidly screen test compounds against minimally modified Mpro protein with the addition of short 11 amino acid HiBiT tag, providing a quantitative luminescence-based data set which closely matched western blot data and with low associated cell toxicity. This ensured any degradation activity we observed was against protein which was as close as possible to natively produced viral Mpro.

In our study, we deliberately and without bias synthesised a wide range of potential TPDs. A range of Mpro inhibitor pharmacophores, covalent reversible (nitrile, hydroxymethyl ketone) and irreversible (chloromethyl ketone) warheads, polar and non-polar linkers of variable length and diverse target E3 ligase motifs were all included. These all inhibited Mpro enzyme activity in a cell-free FRET assay; however, binary potency did not translate into TPD potency, with most compounds showing marginal effects in lowering Mpro protein in the initial cell-based screen.

Nonetheless, a few compounds stood out with robust dose and time-dependent reductions in Mpro. The most potent three compounds were all derived from nirmatrelvir - BP-172, a VH101 derived VHL based recruiter, as well as BP-174 and BP-198, both LCL-161 derived IAP-targeting recruiters (so called specific and non-genetic IAP-dependent protein erasers or SNIPERs31), with TPD efficiency at 24 h seemingly dependent upon either permeability, the competition between binary and ternary complexes and/or productivity of ternary complex formation. Our experiments confirmed that these nirmatrelvir-based TPDs functioned in a genuine heterobifunctional manner, with engagement of Mpro and recruitment of the ubiquitin ligase machinery and proteasomal degradation crucial to eliminating the target. To our knowledge, our work here is the first description of SNIPER-based TPDs that successfully degrade viral proteins, confirming that these classes of ubiquitin ligases can be harnessed to expand the repertoire capable of degrading viral proteins. Sang et al recently reported a cereblon-targeting molecule also built off a nirmatrelvir-like scaffold, HP21120632. Interestingly, HP211206 reduced Mpro in transfected-HEK cells but with a quite slow 48 h onset of action. Additionally, another GC-376-based pomalidomide conjugate, PROTAC 1, induced a modest reduction of recombinant Mpro at micromolar doses after 24 h33. However, the mechanism of target loss was not confirmed in either of these studies, and their antiviral effects not verified. Whilst this paper was under review, a cereblon-recruiting Mpro degrader, MPD2, and the VHL-based degraders P2 and P3 were reported which degraded recombinant Mpro by the Ub-proteasome system, with some preliminary data suggesting antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 wildtype virus34,35 and an eGFP-labelled E166V Mpro variant virus34. However, antiviral data were lacking a matched NDMI control to discriminate inherent enzymatic inhibition of the parental molecule, and phenotypic nirmatrelvir resistance of the eGFP - E166V variant was not confirmed.

Nirmatrelvir is a much smaller, highly effective, optimized enzymatic inhibitor with a superior pharmacokinetic profile for cellular permeability and solubility than our lead TPD. For this reason, a direct comparison of our much larger TPD against unmodified nirmatrelvir, which does not factor in these pharmacokinetic profile limitations and differences, would not offer a precise determination of differences between the two for our virological studies. However, converting nirmatrelvir into the precisely matched NDMI controls to account for these extenuating factors such as molecule size and membrane permeability whilst retaining the full target engagement capabilities of the nirmatrelvir pharmacophore, enabled a direct comparison between enzymatic inhibition alone (BP-206) and inhibition plus target degradation (BP-198). This approach was central in our study to confirm that conversion of existing potent enzymatic inhibitors to TPDs to degrade Mpro resulted in a 2.1–2.6-fold enhanced antiviral potency over enzymatic inhibition alone. Importantly, this enhanced activity was only detectable in the dose range at which degradation of Mpro was also observed in our reporter assays, strengthening the association between degradation of the target and additional effectiveness.

Interestingly, upon further testing, we observed a possible strain-specific enhancement of the TPD’s antiviral effect. Although we could demonstrate enhanced antiviral activity of BP-198 over BP-206 in both SARS-CoV-2 (VIC-01) and Omicron BA.5 strains, under the conditions used here, BP-198 and BP-206 were found to have equivocal effects against SARS-CoV-2 Delta WT. There are multiple reasons this may have occurred -including the focus-formation assay used in the Delta study measures single foci of infection and cells were not pre-treated with compounds prior to infection. In contrast, the antiviral assays used to examine VIC-01 and Omicron BA.5 can incorporate ongoing rounds of replication over 24 h, and cells were pre-treated with compound prior to infection. In addition to this, the Delta strain is generally more cytopathic that the ancestral and Omicron BA.5 strains used here, and has higher replication rates than Omicron when compared in both Vero/TMPRSS2 and Calu-3 cell lines36. It follows that the high replicative Delta model used in the resistance study may have higher intracellular Mpro levels, potentially altering the kinetics at which ideal ternary complex formation and detectable enhanced antiviral activity occur. Further optimisation of viral MOI and experimental conditions are warranted to better resolve this.

Nonetheless, the equivocal findings for BP-198 and BP-206 against SARS-CoV-2 Delta WT set the stage for comparison of these two drugs against the comparator Delta strain precisely modified to encode nirmatrelvir resistant mutations E166V/L50F. Consistent with previous studies37,38, we found these mutations conferred a high level of resistance to unmodified nirmatrelvir (261-fold reduced potency compared to WT). In contrast, despite still resulting in a roughly equipotent IC50 to unmodified nirmatrelvir, BP-198 only had a 25-fold reduced potency when tested against this nirmatrelvir-resistant strain, and maintained a 2.7-fold increase in potency compared to BP-206, confirming that our TPD confers high antiviral potency against nirmatrelvir-resistant virus infection compared to size matched NDMI controls and retains a greater ability to maintain potency against the virus. Again, this occurred in the precise concentration window where degradation of Mpro was observed in our expression model.

The E166V Mpro mutation alone decreases the binding efficacy of nirmatrelvir but comes at a cost to viral fitness, reducing protease activity and viral replication rates7,8. Evolutionary compensation can occur through selection of the T21I and/or L50F mutations8. The dual E166V/L50F mutant virus used in this study has been selected clinically39, is capable of outcompeting wildtype virus in the presence of nirmatrelvir. Although clinical resistance to nirmatrelvir does not appear to be a major problem, it was important to test our TPDs for activity against nirmatrelvir resistant Mpro and replicating virus, their maintained activity providing valuable evidence that antiviral TPDs may be able to circumvent emergence of clinical antiviral resistance, as has been described for oncology TPD therapeutics40. Further support for the utility of TPDs in circumventing antiviral resistance comes from a study where the hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3 protease inhibitor telaprevir was converted into a TPD41 and found to have a 3-fold loss in activity against an HCV variant that conferred 10-fold loss in activity against telaprevir. In that study a comparison with the matched non-degrading control was not performed.

Whilst this paper was under revision, two other antiviral TPD papers targeting dengue virus envelope protein and the human immunodeficiency virus Nef-1 protein were published34,42, highlighting the burgeoning importance of this class of therapeutic as an approach for antiviral therapy. Of note, the dengue TPD study demonstrated that, as the envelope protein is conserved amongst the family Flaviviridae, the TPD was capable of 1.1–7.6-fold enhanced antiviral effect against other flavivirus members such as Zika virus, Japanese encephalitis virus and West Nile virus compared to non-degrading controls; however, a loss of activity was found against yellow fever virus34. Therefore, TPDs might be capable of enhanced therapeutic effect against multiple viral family members. Preliminary evidence of this has also been observed for the TPD P2 and P3 against other coronaviruses HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43 although the effect on viral yield was not confirmed35. The mechanism by which TPDs may confer activity against broad families may resemble the same mechanism by which TPDs may be able to overcome antiviral resistance; they are able to maintain selectivity and potency even with the sub-optimal target binding that can occur due to selection of resistance or evolutionary variation. Further work on these promising aspects of TPD technology is therefore warranted.

Antiviral TPDs is an emerging field, with few studies employing the use of pharmacologically matched non-degrading controls. The recent paper published on a dengue virus-targeting TPD derived from a parental drug with much lower inherent antiviral activity than nirmatrelvir, has shown using non-degrading controls an increased antiviral activity of between 4 and 6-fold40 for the TPD compared to matched non-degrading controls which is quite similar to our study here. The non-degrading controls used in that study had very similar antiviral activity as the parental molecule in isolation, whereas in our study both TPD and non-degrading control have less antiviral activity than unmodified nirmatrelvir against wildtype viral strains, despite having comparable Mpro binding activity to nirmatrelvir in a cell-free FRET system, which points to cellular permeability of our current molecules being an issue.

Whilst the potency of BP-198 is in line with, or superior to, other Mpro TPD candidates, we don’t precisely know why the TPD has a modest 2.1-2.7 fold potency over the NDMI in our viral assays. We can speculate that the nirmatrelvir warhead present on both BP-198 and BP-206 is already very good at inhibiting most of the primary functions of Mpro to inhibit viral replication. However, the additional effects of BP-198 rely on degradation of Mpro, which only occur at a higher 10 µM onward concentration of drug. Hence, for viral therapy, we believe that target selection, the capability of the parental drug to inhibit the primary function of that target, the extent of any additional auxiliary functions outside of the primary inhibited function which contribute to viral replication and subsequent drug pharmacokinetic optimisation may be crucial considerations to determine the magnitude of any benefit of parental drug to TPD conversion.

It is important to take note of the limited efficacy of the lead BP-198 compound compared to unmodified nirmatrelvir against wildtype virus which we attribute to poor cellular permeability of the larger TPD, as binary affinity for Mpro was retained when tested in a cell-free Mpro inhibition assay. This potentially would also manifest as limited oral bioavailability of the compound (a potentially impediment to their use against viral infection) such that along with further optimization of ternary complex driven ubiquitination physicochemical properties will need to be addressed. In TPD development, the target protein ligand and ubiquitin ligase recruiter are often fixed; linker optimization can potentially improve the pharmacokinetic profile of our lead TPD candidate BP-198. For example, linker rigidification could stabilise the ternary complex and minimise the loss of entropy upon binding, whereas the incorporation of tertiary aliphatic nitrogen could improve solubility43,44. These linker properties are key to bioavailability and are often found in numerous TPDs currently in clinical trials13. Interestingly, efficacy compared to unmodified nirmatrelvir was comparable against nirmatrelvir-resistant mutants suggesting that either the binding affinity of the TPDs for modified Mpro form was conserved or that the TPD activity was less dependent upon the binary affinity (as has been proposed for HCV TPDs41). Hence, the TPDs developed here will require optimisation to improve permeability, ternary complex stability and productivity (ubiquitination) before they could be developed into pre-clinical candidate.

Overall, this study represents an important step amongst other first-line studies in discovering the advantages of TPDs for broader antiviral therapy. The initial findings we describe here show an ability to further enhance antiviral effect, and importantly possess activity against clinically relevant Mpro mutations that confer resistance to the parental inhibitor nirmatrelvir. Altogether further optimisation of BP-198, while requiring enhancement on several fronts, offers the opportunity to create a new modality in treating SARS-CoV-2 infection. Further application of this technology in the virology field is warranted and may yet yield more effective therapies for the future.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Wei Zhou for his contributions to this study and Dr. Jason Dang for acquiring HRMS data. B.P. was a recipient of a Monash Graduate Scholarship and Monash International Tuition Scholarship. N.W. is a recipient of a Peter Doherty Institute seed fund. J.S. is the recipient of an Australian NHMRC Emerging Leadership Fellowship.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: B.P., P.E.T., S.A.G., N.W.; Methodology: B.P., S.J.M., M.K., D.E.A., S.Y., Y.K., P.E.T., S.A.G., N.W.; Investigation: B.P., S.J.M., M.K., K.E.J., D.R.T., B.M., S.Y., Y.K., S.A.G., N.W.; Visualization: P.E.T., S.A.G., N.W.; Funding acquisition: J.S., P.E.T., S.A.G., N.W.; Project administration: P.E.T., S.A.G., N.W.; Supervision: J.S., S.Y., Y.K., P.E.T., S.A.G., N.W.; Writing – original draft: B.P., P.E.T., S.A.G., N.W.; Writing – review & editing: B.P., J.S., P.E.T., S.A.G., N.W.

Peer review

Peer review information

This manuscript has been previously reviewed at another Nature Portfolio journal. The manuscript was considered suitable for publication without further review at Communications Medicine.

Data availability

Source data for all figures are accessible within the Supplementary Data file. For each figure, the corresponding source data has been labelled as the figure number, for example, the source data for Fig. 1 has been labelled as “Fig. 1” within the data file. Bespoke materials are available under a material transfer agreement (MTA). Correspondence – PET, SAG, NW.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Philip E. Thompson, Sam A. Greenall, Nadia Warner.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s43856-025-00863-1.

References

- 1.Carlson, C. J. et al. Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature607, 555–562 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hale, V. L. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in free-ranging white-tailed deer. Nature602, 481–486 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irving, A. T., Ahn, M., Goh, G., Anderson, D. E. & Wang, L. F. Lessons from the host defences of bats, a unique viral reservoir. Nature589, 363–370 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li, G., Hilgenfeld, R., Whitley, R. & De Clercq, E. Therapeutic strategies for COVID-19: progress and lessons learned. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.22, 449–475 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman, R. L. et al. Discovery of Ketone-Based Covalent Inhibitors of Coronavirus 3CL Proteases for the Potential Therapeutic Treatment of COVID-19. J. Med Chem.63, 12725–12747 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owen, D. R. et al. An oral SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) inhibitor clinical candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Science374, 1586–1593 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duan, Y. et al. Molecular mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 resistance to nirmatrelvir. Nature622, 376–382 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iketani, S. et al. Multiple pathways for SARS-CoV-2 resistance to nirmatrelvir. Nature613, 558–564 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiso, M. et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of SARS-CoV-2 strains resistant to nirmatrelvir. Nat. Commun.14, 3952 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu, Y. et al. Naturally Occurring Mutations of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Confer Drug Resistance to Nirmatrelvir. ACS Cent. Sci.9, 1658–1669 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ip, J. D. et al. Global prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease mutations associated with nirmatrelvir or ensitrelvir resistance. eBioMedicine91, 104559 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paiva, S. L. & Crews, C. M. Targeted protein degradation: elements of PROTAC design. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol.50, 111–119 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bekes, M., Langley, D. R. & Crews, C. M. PROTAC targeted protein degraders: the past is prologue. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.21, 181–200 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bondeson, D. P. et al. Catalytic in vivo protein knockdown by small-molecule PROTACs. Nat. Chem. Biol.11, 611–617 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bondeson, D. P. et al. Lessons in PROTAC Design from Selective Degradation with a Promiscuous Warhead. Cell Chem. Biol.25, 78–87.e75 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.den Boon, J. A. et al. Multifunctional Protein A Is the Only Viral Protein Required for Nodavirus RNA Replication Crown Formation. Viruses14, 2711 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng, P., Wu, Z. & Wang, A. The multifunctional protein CI of potyviruses plays interlinked and distinct roles in viral genome replication and intercellular movement. Virol. J.12, 141 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faust, T. B., Binning, J. M., Gross, J. D. & Frankel, A. D. Making Sense of Multifunctional Proteins: Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Accessory and Regulatory Proteins and Connections to Transcription. Annu. Rev. Virol.4, 241–260 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zoppi, V. et al. Iterative Design and Optimization of Initially Inactive Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) Identify VZ185 as a Potent, Fast, and Selective von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) Based Dual Degrader Probe of BRD9 and BRD7. J. Med Chem.62, 699–726 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohoka, N. et al. In Vivo Knockdown of Pathogenic Proteins via Specific and Nongenetic Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein (IAP)-dependent Protein Erasers (SNIPERs). J. Biol. Chem.292, 4556–4570 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng, X. et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screens using isogenic cells reveal vulnerabilities conferred by loss of tumor suppressors. Sci. Adv.8, eabm6638 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caly, L. et al. Isolation and rapid sharing of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) from the first patient diagnosed with COVID-19 in Australia. Med J. Aust.212, 459–462 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin, G. E. et al. Maintaining genomic surveillance using whole-genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 from rapid antigen test devices. Lancet Infect. Dis.22, 1417–1418 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vuong, W. et al. Feline coronavirus drug inhibits the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 and blocks virus replication. Nat. Commun.11, 4282 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sacco, M. D. et al. Structure and inhibition of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease reveal strategy for developing dual inhibitors against M(pro) and cathepsin L. Sci Adv6, 10.1126/sciadv.abe0751 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Gadd, M. S. et al. Structural basis of PROTAC cooperative recognition for selective protein degradation. Nat. Chem. Biol.13, 514–521 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zengerle, M., Chan, K. H. & Ciulli, A. Selective Small Molecule Induced Degradation of the BET Bromodomain Protein BRD4. ACS Chem. Biol.10, 1770–1777 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang, Y., Ye, P., Wang, X., Xu, X. & Reisen, W. Real-time monitoring of flavivirus induced cytopathogenesis using cell electric impedance technology. J. Virol. Methods173, 251–258 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oeyen, M., Meyen, E., Doijen, J. & Schols, D. In-Depth Characterization of Zika Virus Inhibitors Using Cell-Based Electrical Impedance. Microbiol Spectr.10, e0049122 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramakrishnan, M. A. Determination of 50% endpoint titer using a simple formula. World J. Virol.5, 85–86 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohoka, N. et al. Derivatization of inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) ligands yields improved inducers of estrogen receptor alpha degradation. J. Biol. Chem.293, 6776–6790 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sang, X. et al. A Chemical Strategy for the Degradation of the Main Protease of SARS-CoV-2 in Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 27248–27253 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grifagni, D. et al. Development of a GC-376 Based Peptidomimetic PROTAC as a Degrader of 3-Chymotrypsin-like Protease of SARS-CoV-2. ACS Med. Chem. Lett.15, 250–257 (2024) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alugubelli, Y. R. et al. Discovery of First-in-Class PROTAC Degraders of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease. J. Med Chem.67, 6495–6507 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng, S. et al. Development of novel antivrial agents that induce the degradation of the main protease of human-infecting coronaviruses. Eur. J. Med. Chem.275, 116629 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao, H. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant shows less efficient replication and fusion activity when compared with Delta variant in TMPRSS2-expressed cells. Emerg. Microbes Infect.11, 277–283 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou, Y. et al. Nirmatrelvir-resistant SARS-CoV-2 variants with high fitness in an infectious cell culture system. Sci. Adv.8, eadd7197 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moghadasi, S. A., Biswas, R. G., Harki, D. A. & Harris, R. S. Rapid resistance profiling of SARS-CoV-2 protease inhibitors. npj Antimicrobials Resistance1, 9 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zuckerman, N. S., Bucris, E., Keidar-Friedman, D., Amsalem, M. & Brosh-Nissimov, T. Nirmatrelvir Resistance—de Novo E166V/L50V Mutations in an Immunocompromised Patient Treated With Prolonged Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir Monotherapy Leading to Clinical and Virological Treatment Failure—a Case Report. Clin. Infect. Dis.78, 352–355 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buhimschi, A. D. et al. Targeting the C481S Ibrutinib-Resistance Mutation in Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Using PROTAC-Mediated Degradation. Biochemistry57, 3564–3575 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Wispelaere, M. et al. Small molecule degraders of the hepatitis C virus protease reduce susceptibility to resistance mutations. Nat. Commun.10, 3468 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emert-Sedlak, L. A. et al. PROTAC-mediated degradation of HIV-1 Nef efficiently restores cell-surface CD4 and MHC-I expression and blocks HIV-1 replication. Cell Chem. Biol.31, 658–668 e614 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu, X. et al. Discovery of XL01126: A Potent, Fast, Cooperative, Selective, Orally Bioavailable, and Blood-Brain Barrier Penetrant PROTAC Degrader of Leucine-Rich Repeat Kinase 2. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 16930–16952 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Troup, R. I., Fallan, C. & Baud, M. G. J. Current strategies for the design of PROTAC linkers: a critical review. Explor Target Antitumor Ther.1, 273–312 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Source data for all figures are accessible within the Supplementary Data file. For each figure, the corresponding source data has been labelled as the figure number, for example, the source data for Fig. 1 has been labelled as “Fig. 1” within the data file. Bespoke materials are available under a material transfer agreement (MTA). Correspondence – PET, SAG, NW.