Abstract

The aboveground body of higher plants has a modular structure of repeating units, or phytomers. As such, the position, size, and shape of the individual phytomer dictate the plant architecture. The Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ERECTA (ER) gene regulates the inflorescence architecture by affecting elongation of the internode and pedicels, as well as the shape of lateral organs. A large-scale activation-tagging genetic screen was conducted in Arabidopsis to identify novel genes and pathways that interact with the ER locus. A dominant mutant, super1-D, was isolated as a nearly complete suppressor of a partial loss-of-function allele er-103. We found that SUPER1 encodes YUCCA5, a novel member of the YUCCA family of flavin monooxygenases. The activation tagging of YUCCA5 conferred increased levels of free indole acetic acid, increased auxin response, and mild phenotypic characteristics of auxin overproducers, such as elongated hypocotyls, epinastic cotyledons, and narrow leaves. Both genetic and cellular analyses indicate that auxin and the ER pathway regulate cell division and cell expansion in a largely independent but overlapping manner during elaboration of inflorescence architecture.

The aboveground body of higher plants is a consequence of the continual activity of the shoot apical meristem (SAM), which generates repeating units called phytomers. Each phytomer is composed of a node, stem (internode), leaf (lateral organ), and axillary bud, the latter of which allows branching. Modification of the position, size, and shape of the individual phytomer provides immense variations in plant architecture. Such diversity in plant architecture has significance in the domestication and breeding of crop plants. For instance, the maize (Zea mays) teosinte branched1 gene regulates branching pattern, and alteration in the teosinte branched1 expression level played a pivotal role in the domestication of maize (spp. mays) from its wild ancestor, Teosinte (maize spp. Parviglumis; Doebley et al., 1997). Another example is semidwarf varieties of cereals, in which reduction in the internode length has directly contributed to dramatic yield increase (Chrispeels and Sadava, 1994; Peng et al., 1999).

The model plant Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) forms a typical rosette. During the vegetative stage, the Arabidopsis plant produces rosette leaves with no apparent internodal elongation. As the SAM acquires reproductive characteristics, the primary inflorescence stem elongates rapidly (bolting). First, the SAM gives rise to a shoot that has both vegetative and reproductive characteristics, including bracts (cauline leaves), axillary buds, and branches. Subsequently, the SAM generates multiple floral meristems, each of which differentiates a flower at the tip and a pedicel at the base, while the SAM itself maintains its indeterminate state (Schultz and Haughn, 1991).

Molecular-genetic studies have highlighted the in vivo role of phytohormones and growth regulators for normal growth of the inflorescence. For instance, mutants defective in biosynthesis or signaling pathways of auxin, gibberellin, brassinosteroids, and sporamin conferred dwarfism due to reduced cell elongation and/or cell division in the internode (Feldmann et al., 1989; Lincoln et al., 1990; Leyser et al., 1993; Li et al., 1996; Li and Chory, 1997; Azpiroz et al., 1998; Hedden and Proebsting, 1999; Hanzawa et al., 2000; Fridborg et al., 2001; Olszewski et al., 2002). Conversely, elevated response to these phytohormones, either by mutations in the downstream components of the signaling pathways or overexpression of the biosynthetic enzymes, led to extra elongation of the inflorescence (Wang et al., 2001, 2002; Zhao et al., 2001; Olszewski et al., 2002).

Loss-of-function mutations in the Arabidopsis ERECTA (ER) gene dramatically modify inflorescence architecture due to altered organ shape and internodal elongation pattern (Torii et al., 1996; Komeda et al., 1998). Compared to the wild type, the young erecta (er) inflorescence forms flattened and somewhat umbellate floral bud clusters due to reduced internodal and pedicel elongation. At seed set, er forms a compact inflorescence with short and thick internodes, pedicels, and siliques. The ER gene encodes a Leu-rich repeat receptor-like kinase (RLK; Torii et al., 1996). Other members of the Leu-rich repeat-RLK superfamily are known to regulate diverse aspects of development, defense against pathogens, and wounding response, and their known ligands vary from short peptides (e.g. phytosulfokine, systemin, and flagellin peptide) and proteins (CLAVATA3) to steroids (e.g. brassinolide; Matsubayashi et al., 2001; Ryan et al., 2002; Carles and Fletcher, 2003; Diévart and Clark, 2004; Torii, 2004). Although the ligands and downstream targets of ER are not known, recent studies revealed that ER and its two closely related paralogs interact in a synergistic manner in promoting cell proliferation, leading to aboveground organ growth (Shpak et al., 2003, 2004).

ER exhibits strong genetic interactions with multiple phytohormone and growth regulatory pathways. For example, ER was identified as a strong suppressor of dwarfism caused by two gibberellin response mutants, gai and shi (Peng et al., 1997; Fridborg et al., 2001). Indeed, the height of the shi inflorescence was nearly 6 times greater in the presence of functional ER (Fridborg et al., 2001). A similar effect of ER was observed for the dwarf phenotype of the auxin response mutant transport inhibitor resistance3 (tir3)/attenuated shade avoidance1 (Kanyuka et al., 2003). In either case, the cellular basis of ER-mediated suppression has not been investigated. ER also shows dramatic interaction with BREVIPEDICELLUS in specifying inflorescence architecture (Douglas et al., 2002). BREVIPEDICELLUS encodes KNAT1, a KNOTTED-like homeodomein protein that promotes internodal growth via modulating the expression of the lignin biosynthesis genes (Mele et al., 2003).

To better understand how ER promotes inflorescence growth, it is necessary to identify genes that interact with the ER pathway. We initiated an activation-tagging screen to isolate dominant, extragenic suppressors of the er inflorescence phenotype using a partial loss-of-function allele er-103. The strategy is based on a random insertion of 4× cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S enhancers that, if inserted in cis-regulatory elements, will lead to up-regulation of nearby open reading frames (Kakimoto, 1996; Weigel et al., 2000). We discovered that the activation tagging of YUCCA5, a previously undescribed member of YUCCA family genes encoding a putative flavin monooxygenase, led to elevated auxin levels and a nearly complete suppression of er-103 inflorescence elongation defects. Our detailed developmental and cellular analyses highlighted the complex interplay of auxin and the ER-mediated pathway in the elaboration of inflorescence architecture.

RESULTS

Isolation of suppressor of er1-Dominant as a Suppressor of er-103

To identify genes whose overexpression suppresses the er phenotype, a gain-of-function activation-tagging screen was performed using the intermediate allele er-103 (Torii et al., 1996). Approximately 6,000 T1 Basta-resistant plants were visually screened for suppressed flower-clustering phenotype at bolting. One line, 38May2, displayed an inflorescence phenotype nearly identical to that of the wild-type ER (Fig. 1, A–C). A genetic analysis of the subsequent T2 generation revealed that the suppressor is dominant and tightly linked to Basta resistance, indicating that it is activation tagged by the 4×CaMV enhancer (see “Material and Methods”). The mutant was named suppressor of er1-Dominant (super1-D).

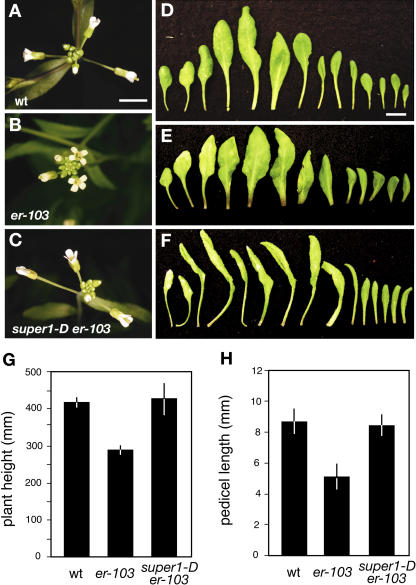

Figure 1.

super1-D is a genetic suppressor of er-103. A to C, Inflorescence top view of wild-type (A), er-103 (B), and super1-D er-103 (C) plants at bolting. Flowers of wild-type and super1-D er-103 plants display dramatic pedicel elongation, while the inflorescence tip of er-103 forms a characteristic flat, disc shape due to reduced internodal and pedicel elongation. Images are taken under the same magnification. Scale bar, 5 mm. D to F, Rosette leaves of 4-week-old wild type (D), er-103 (E), and super1-D er-103 (F). Leaves were dissected from the primary shoot axis and laid out in the sequence of development (left, base; right, apex). Images are taken under the same magnification. Scale bar, 1 cm. G and H, Morphometric analysis of full-grown 7-week-old wild-type, er-103, and super1-D er-103 plants. G, Plant height (n = 8). H, Lengths of mature pedicels on the main stem (n = 35; seven measurements per stem). Bars represent the mean; error bars = sd.

super1-D Suppresses Internodal and Pedicel Elongation Defects of er-103

We subsequently analyzed the morphological phenotype of super1-D er-103 during vegetative and reproductive development (Fig. 1). Unlike wild-type plants, er-103 plants develop a compact rosette leaf with a short petiole and round blade (Fig. 1, D and E; Torii et al., 1996). The super1-D mutation suppressed the rosette phenotype of er-103 and further conferred characteristic leaf morphology including elongated petioles and long, narrow blades that often curled down (Fig. 1F).

The inflorescence architecture of super-1D er-103 highly resembles that of the wild type. Flower buds of the wild type fold on to each other to cover the SAM, and older flowers have elongated pedicels (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the inflorescence tip of er-103 forms a characteristic disc-shaped, flat surface due to defective elongation of internodes and pedicels (Fig. 1B). super1-D suppressed the flower-clustered phenotype of er-103 (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, mature super1-D er-103 plants are as tall as wild-type plants (Fig. 1G), and elongation of er-103 pedicels is fully rescued by super1-D (Fig. 1H). In addition, super1-D conferred reduced fertility (data not shown). These results indicate that overexpression of SUPER1 by activation tagging suppresses stem and pedicel elongation defects of er but also confers additional developmental phenotypes, such as altered leaf shape and reduced fertility.

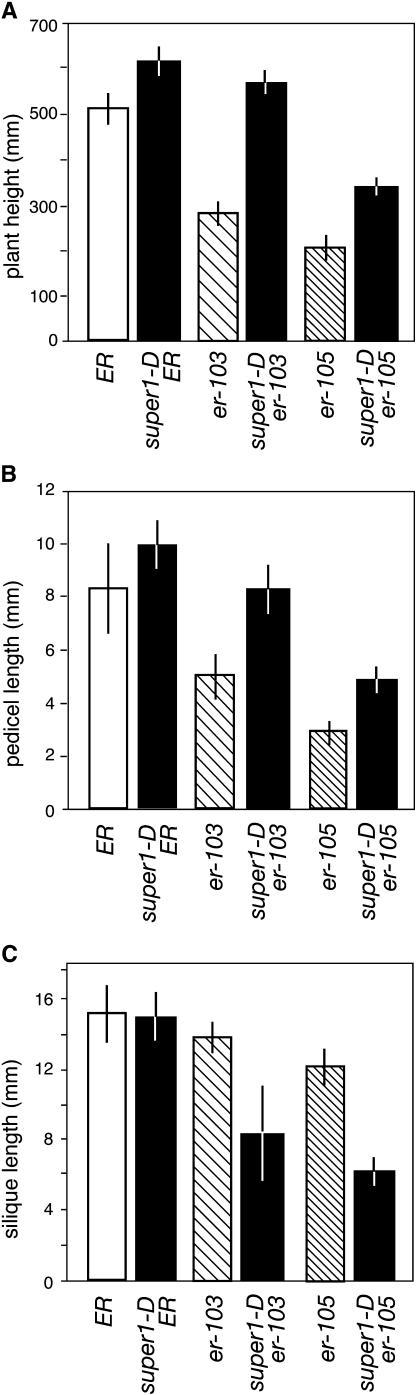

Genetic Interaction of er and super1-D Mutants

To understand the nature of genetic interaction, the super1-D mutation was subsequently introduced into wild-type ER and null er-105 allele backgrounds. It has been shown that the severity of er mutations directly reflects reduction in plant height, pedicel length, and fruit (silique) length in a quantitative manner (Torii et al., 1996, 2003). Wild-type ER plants develop the longest stems, pedicels, and siliques; null er-105 plants develop the shortest; and er-103 plants are intermediate (Fig. 2). As shown in Figure 2, A and B, the super1-D mutation conferred extra elongation of stems and pedicels both in ER and er-105 plants, suggesting the largely additive nature of interaction. Interestingly, the degree of stem and pedicel elongation was greater in er mutants than in a wild type (For stem length, 17%, 50%, and 43% increase in ER, er-103, and er-105, respectively; for pedicel length, 19%, 32%, and 41% increase in ER, er-103, and er-105, respectively.) Thus, er mutants may be more sensitive to the organ elongation effects of super1-D (see “Discussion”).

Figure 2.

Genetic interaction of super1-D with different er alleles. A, Effects of super1-D mutation on final height of wild-type ER, intermediate er-103, and null er-105 alleles. n = 10 per genotype, error bars = sd. B, Effects of super1-D mutation on pedicel length of wild-type ER, intermediate er-103, and null er-105 alleles. n = 40 per genotype, error bars = sd. C, Effects of super1-D mutation on silique length of wild-type ER, intermediate er-103, and null er-105 alleles. n = 40 per genotype, error bars = sd.

In contrast to stems and pedicels, er and super1-D exhibited distinct interaction in fruit development. While the wild-type ER allele suppressed the fertility defects of super1-D er-103, the null er-105 allele enhanced the fertility defect. Notably, super1-D er-105 plants produced short siliques that contain very few seeds (Fig. 2C and data not shown). Thus, a functional ER pathway is required for proper fruit development in the super1-D background. From these findings, we conclude that SUPER1 acts in pathways independent from ER, with possible interplay during the development of specific organs, such as the silique.

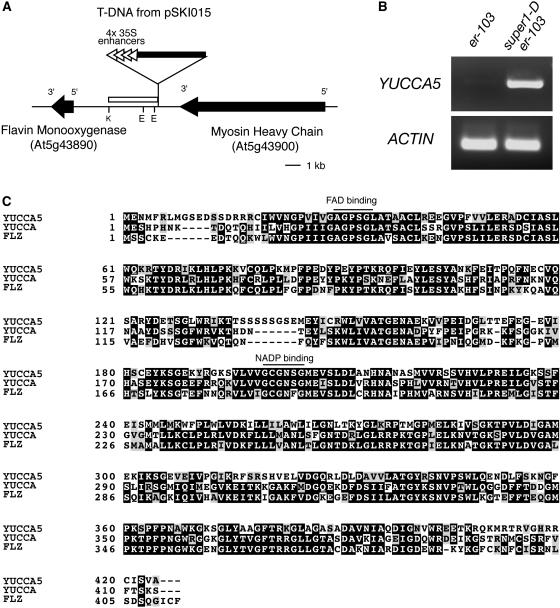

SUPER1 Encodes a YUCCA-Like Putative Flavin Monooxygenase

To gain insights into the molecular nature of the super1-D phenotype, we cloned the genomic DNA fragment flanking the right border of the T-DNA insertion (Fig. 3A). Sequencing analysis revealed that the CaMV35S 4× enhancer elements were inserted approximately 5.6 kb upstream of an open reading frame on Chromosome V (bacterial artificial chromosome F6B6). This corresponds to At5g43890/BAA98069, which encodes a 424-amino acid putative flavin-containing monooxygenase (Fig. 3A). It belongs to the YUCCA family genes implicated in biosynthesis of auxins, with BLAST scores of 1e-127, 1e-162, and 1e-128 to Arabidopsis YUCCA (At4g32540), YUCCA3 (At1g04610), and petunia (Petunia hybrida) FLOOZY (FLZ), respectively (Zhao et al., 2001; Tobeña-Santamaria et al., 2002). A subsequent, reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis revealed that super1-D er-103 inflorescence accumulates transcripts of At5g43890 at a much higher level than er-103, strongly suggesting that SUPER1encodes this YUCCA-like putative flavin monooxygenase (Fig. 3B). Similar to YUCCA, the SUPER1 protein possesses conserved FAD-binding (GAGPSG) and NADH-binding (GCGNSG) motifs (Fig. 3C). The open reading frames of YUCCA, YUCCA2, and FLZ are intercepted by three introns at the same exact positions (Tobeña-Santamaria et al., 2002). In contrast, SUPER1 does not possess any introns. The gene was renamed YUCCA5 following the nomenclature of the YUCCA family genes.

Figure 3.

SUPER1 encodes YUCCA5, a previously undescribed member of YUCCA family putative flavin monooxygenases. A, Genomic organization at the T-DNA insertion site. The black arrows indicate open reading frames in the direction of 5′ to 3′. The orientations of 4×35S enhancers are indicated by white triangles. The white bar indicates a flanking sequence recovered by inverse-PCR. K, KpnI; E, EcoRI. B, Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis shows that YUCCA5 transcript levels are elevated in super1-D er-103 inflorescence. The actin fragment was amplified simultaneously as a control. C, Amino acid sequence alignment of YUCCA5 with YUCCA and FLZ, two well-studied members of the YUCCA family of putative flavin monooxygenases. The conserved FAD- and NADP-binding motifs are underlined.

Overexpression of YUCCA5 Confers Suppression of the er-103 Phenotype

To gain direct evidence that the suppression of the er-103 phenotype is due to YUCCA5 overexpression, the full-length cDNA of YUCCA5 was placed under the constitutive CaMV35S promoter and transformed into er-103 plants. As shown in Figure 4, the transgenic plants recapitulated the suppressed inflorescence phenotype of er-103. Furthermore, additional phenotypes, such as narrow leaf blades and reduced fertility, were also recapitulated (data not shown). From these results, we conclude that elevated expression of YUCCA5, a new member of the YUCCA family of putative flavin monooxygenases, confers all aspects of the super1-D phenotype.

Figure 4.

Expression of YUCCA5 cDNA driven by the dual CaMV 35S promoter recapitulated the er-103 suppression phenotype. Shown are inflorescences of 5-week-old wild-type (A), er-103 (B), and transgenic er-103 (C) plants expressing CaMV35S::YUCCA5. Images are taken under the same magnification. Double arrow bars indicate the internode length between the inflorescence tip and the node-bearing flower turning into stage 17. Scale bar, 5 mm.

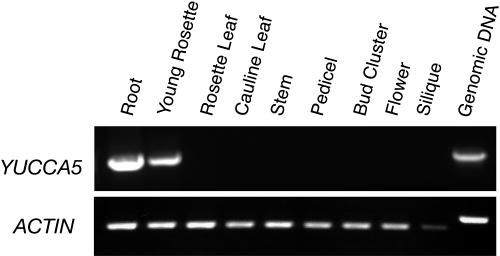

YUCCA5 Is Normally Expressed in Roots and Young Vegetative Tissues

We next investigated the expression levels of YUCCA5 in different organs by RT-PCR. YUCCA5 was predominantly expressed in roots and young vegetative tissues, while it was under detectable levels in reproductive tissues, such as inflorescence stems, pedicels, and floral buds (Fig. 5). Our result was consistent with the expression profiles of YUCCA5 obtained using the Arabidopsis full genome chip array (Affymetrix ATH1: analysis by AtGenExpress [http://web.uni-frankfurt.de/fb15/botanik/mcb/AFGN/atgenex.htm]; virtual northern analysis by Expression Angler [http://bbc.botany.utoronto.ca/ntools/cgi-bin/ntools_expression_angler.cgi]).

Figure 5.

Expression of YUCCA5 in different organs of wild-type Arabidopsis plants. The actin cDNA fragment was amplified as a control for 26 cycles. YUCCA5 cDNA was amplified for 45 cycles.

Overexpression of YUCCA5 by super1-D Results in Elevated Auxin Level and Response

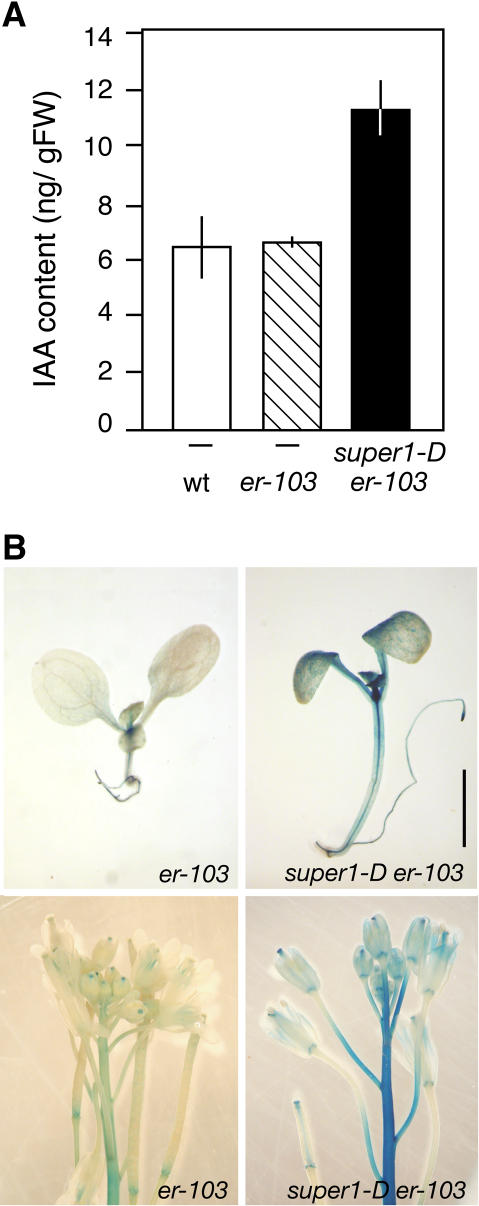

It has been shown that elevated expression of YUCCA, YUCCA3, and FLZ results in overproduction of auxin, and that recombinant YUCCA protein can catalyze the rate-limiting step in Trp-dependent auxin biosynthesis (Zhao et al., 2001; Tobeña-Santamaria et al., 2002). To test whether YUCCA5 plays a role in auxin biosynthesis, we measured the amounts of free indole acetic acid (IAA) in seedlings of wild type, er-103, and super1-D er-103. As shown in Figure 6A, the super1-D mutation led to a roughly 70% increase in free IAA amount in germinating seedlings. On the other hand, er-103 seedlings had normal amounts of free IAA (Fig. 6A), suggesting that growth defects by er-103 mutation are not caused by the reduction in free auxin levels.

Figure 6.

Activation-tagged YUCCA5 by super1-D mutation confers elevated levels of auxin and increased auxin distribution and response in elongating tissues. A, Free IAA content (nanogram/gram fresh weight) in seedlings of wild type, er-103, and super1-D er-103. Error bars = sd. B, The reporter construct AtAux2-11::GUS visualizing auxin distribution and response in 6-d-old seedlings (top) and 5-week-old inflorescence tips (bottom) of er-103 (left) and super1-D er-103 (right), respectively. Scale bar, 2 mm.

To understand the relationship between elevated auxin levels and the suppressed er-103 inflorescence phenotype by super1-D, we sought to visualize cellular auxin distribution and response using genetic tools. For this purpose, we used a reporter construct that expresses the β-glucuronidase (GUS) gene under the 0.6-kb promoter of auxin-responsive gene AtAux2-11/IAA4 (Wyatt et al., 1993). This promoter can respond to a range of auxin concentration from 10−8 to 10−4 m (Wyatt et al., 1993). The well-known reporter construct, DR5::GUS (Ulmasov et al., 1997), did not drive strong GUS expression in the inflorescence and floral tissues; thus, it was not used in this study (data not shown).

The super1-D mutation led to increased AtAux2-11::GUS activity both in seedlings and inflorescences. In seedlings, the elongation zone of hypocotyls and petioles, as well as developing leaves, showed extensive staining (Fig. 6B). Fully expanded cotyledons also displayed increased GUS activity. At the reproductive stage, inflorescence stems at the tip and elongating pedicels exhibited strong staining (Fig. 6B). GUS activity diminished in older pedicels and stems that are no longer elongating (Fig. 6B; data not shown). These results demonstrate that overexpression of YUCCA5 by super1-D leads to elevated levels of free auxin and, importantly, that increased auxin distribution and response in elongating regions of internodes and pedicels likely cause the suppressed er-103 phenotype.

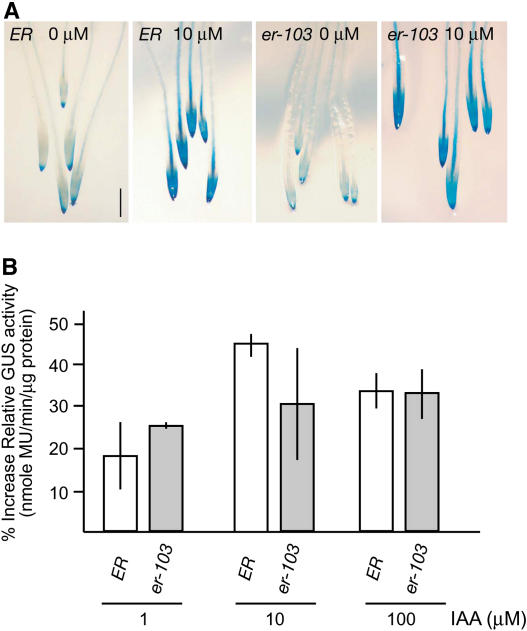

er Mutation Does Not Significantly Alter Auxin Response

While super1-D dramatically suppressed the elongation defects of er-103, the wild-type plants with additional super1-D mutation exhibited only a modest increase in inflorescence and pedicel elongation (Fig. 2). This is not due to reduction in YUCCA5 overexpression by outcrossing into wild-type plants, as YUCCA5 transcripts are equally up-regulated in the wild-type ER background (data not shown). One possibility is that er mutant plants may be defective in responding to normal levels of endogenous auxin to promote organ growth, but they can respond to increased auxin levels resulting from YUCCA5 overexpression. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed induction kinetics of Aux2-11::GUS by exogenous IAA in wild-type and er-103 plants. A 6-h incubation with IAA resulted in increased GUS activity both in wild-type and er-103 seedlings carrying Aux2-11::GUS (Fig. 7). While the GUS induction was most striking in the root tips, entire rosettes displayed some increase in the GUS staining (Fig. 7A and data not shown). However, we did not detect any clear difference in GUS induction levels between wild-type and er-103 seedlings, either by quantitative GUS activity assay or by GUS tissue staining. These results indicate that the er mutation does not significantly alter auxin response and further imply that suppression of the er phenotype by YUCCA5 involves interaction at downstream processes, such as cell proliferation and elongation.

Figure 7.

Induction of GUS activity in wild-type and er-103 seedlings carrying AtAux2-11::GUS reporter construct. A, Histochemical staining of GUS activity in the root tip of wild-type ER and er-103 after a 6-h treatment with 10 μm IAA. Images are taken at the same magnification. Scale bar, 0.5 mm. B, Quantitative GUS fluorimetric activity assays of wild-type ER and er-103 seedlings treated with 1, 10, and 100 μm IAA for 6 h. Bar graphs represent the mean of two independent induction experiments. For each induction, the enzymatic reactions were repeated three times per genotype. Bars = se.

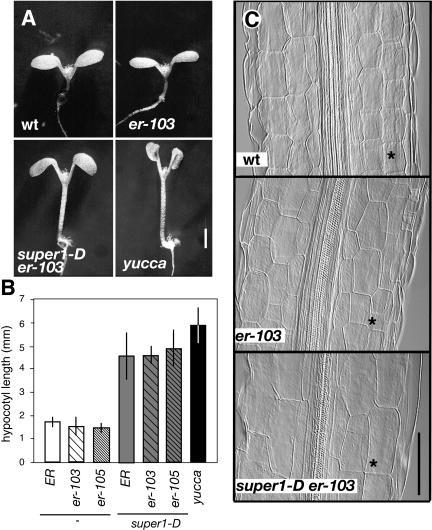

super1-D Is Epistatic to er during Seedling Development and Confers Hypocotyl Cell Elongation

The activation-tagged allele of YUCCA was originally isolated from its seedling-long hypocotyls and epinastic cotyledons, both of which are characteristics of auxin overproduction (Zhao et al., 2001). We next tested whether super1-D also confers seedling auxin overproduction phenotypes. For this purpose, the phenotypic severity was compared between super1-D and a recapitulated yucca line, which drives YUCCA cDNA under the CaMV35S promoter (Zhao et al., 2001). The original yucca-D plants are nearly sterile (Zhao et al., 2001) and thus were not used for the analysis. The super1-D mutation indeed conferred elongated hypocotyls (Figs. 5B and 6A). However, hypocotyl length of super1-D was shorter than that of yucca recapitulated lines (Student's t test; t value = 4.143, P = 0.0003). Unlike yucca recapitulated lines, super1-D seedlings did not exhibit severe cotyledon epinasty, suggesting that the effects conferred by activation-tagged YUCCA5 are rather moderate (Fig. 8A).

Figure 8.

The seedling phenotype of super1-D is epistatic to er, and super1-D confers hypocotyl cell elongation. A, Six-day-old seedlings of wild type (wt: top left), er-103 (top right), super1-D er-103 (bottom left), and recapitulated yucca line (bottom right). Scale bar, 2 mm. B, Hypocotyl length of the wild-type ER, intermediate er-103, null er-105 seedlings with and without the presence of super1-D mutation. Hypocotyl length of the recapitulated yucca line was plotted as a comparison. n = 16, error bars = sd. C, Cellular morphology of hypocotyls of 6-d-old wild type (wt: top), er-103 (middle), and super1-D er-103 (bottom) seedlings. The cortex tissue is indicated by asterisks. Images are taken at the same magnification. Scale bar, 100 μm.

We next analyzed the genetic interaction of er and super1-D during seedling development. We found that the null er-105 mutation resulted in a very subtle yet statistically significant reduction in hypocotyl length (P = 0.0013). Overexpression of YUCCA5 by the super1-D mutation led to elongated hypocotyls regardless of the presence or absence of er mutations (Fig. 8, A and B). Thus, with respect to the long hypocotyl phenotype, super1-D appears epistatic to er. The cellular basis of super1-D-mediated hypocotyl elongation was subsequently investigated. As shown in Figure 8C, both epidermal and cortex cell files show significant elongation under the super1-D background. The results indicate that super1-D confers a long hypocotyl phenotype by increasing cell elongation.

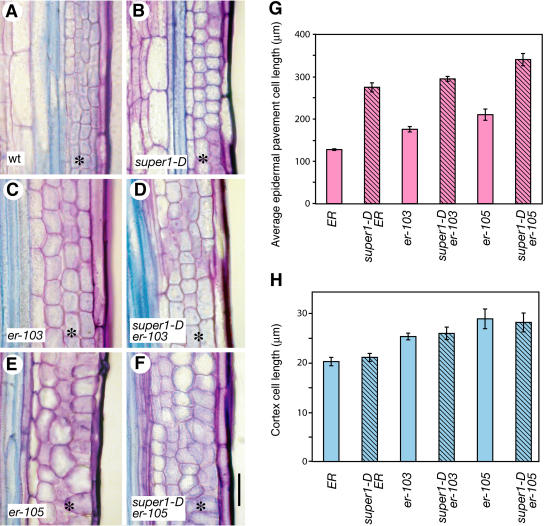

Cellular Phenotype of Mature Pedicels

Unlike hypocotyl elongation, er and super1-D exhibited largely additive effects as well as complex interactions during internode and pedicel elongation, and this led to a complete rescue of er-103 inflorescence architecture (Figs. 1 and 2). To understand the cellular basis of the phenotypic rescue, we next examined the cellular phenotype of mature pedicels. It has been shown that the short pedicel phenotype of er-105 is due primarily to a reduced number of cortex cells, which are abnormally expanded (Shpak et al., 2003). As shown in Figure 9, the severity of the er mutation correlated with an increase in the size of both the epidermal pavement and cortex cells. Interestingly, the effects of super1-D for these two cell types were completely distinct. The super1-D mutation led to elongation of the pedicel epidermal pavement cells of wild-type ER, er-103, and er-105 (P = 0.0058, P = 0.0005, and P = 0.042 for the comparison of ER and super1-D ER, er-103 and super1-D er-103, and er-105 and super1-D er-105, respectively; Fig. 9G). The extent of increased epidermal cell elongation of er mutants by super1-D roughly correlated with the increased pedicel length (Figs. 2B and 9G). By contrast, the presence of super1-D had no effects on cortex cell size (P = 0.48, P = 0.66, and P = 0.79 for the comparison of ER and super1-D ER, er-103 and super1-D er-103, and er-105 and super1-D er-105, respectively; Fig. 9H). The results suggest that super1-D suppresses pedicel elongation defects of er by promoting elongation of the epidermal pavement cells, which is accompanied by an increase in cortex cell numbers.

Figure 9.

Cellular basis of super1-D-mediated pedicel elongation. A to F, Longitudinal sections of mature pedicels from wild type (wt; A), super1-D (B), er-103 (C), super1-D er-103 (D), er-105 (E), and super1-D er-105 (F). The er mutations led to a reduced number of enlarged cortex cells (asterisks), while super1-D mutation promotes pedicel elongation without increasing the cortex cell size. Bars = 50 μm. G, Average epidermal pavement cell length. For each genotype, pedicel epidermal strips were prepared from three individual plants. Fifteen pavement cells were measured from each epidermal strip. Bars = se. H, Cortex cell length. Bar represent the average (n = 20 for each genotype). Bars = se.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we isolated a dominant suppressor of er by activation tagging and further identified that suppression of the er inflorescence phenotype was due to overexpression of YUCCA5, a previously undescribed member of the YUCCA family of putative flavin monooxygenases. Our findings highlight an intersection of auxin and ER-RLK signaling that is important for plant growth and elaboration of inflorescence architecture.

Activation Tagging of YUCCA5 Confers Elevated Auxin Levels and Elongated Inflorescence

Among 10 Arabidopsis YUCCA family members, SUPER1/YUCCA5 belongs to a subfamily with two additional members, At1g04180 (AAC16744) and BAS3/At4g28720 (CAA22980). These subfamily members possess either no intron (YUCCA5 and BAS3) or one intron (At1g04180), as opposed to three introns in conserved locations in orthotypical YUCCA members (e.g. YUCCA2, THREAD/YUCCA4, and petunia FLZ; Tobeña-Santamaria et al., 2002). Our finding, that overexpression of YUCCA5 by super1-D mutation conferred increased free IAA levels, extends the role of this YUCCA subfamily for auxin biosynthesis. In contrast, activation tagging of BAS3, the closest homolog of YUCCA5, had been reported to confer short hypocotyls, a phenotype opposite to super1-D (Zhao et al., 2001).

Although their IAA contents have not been quantified, the activation tagging/overexpression of other YUCCA members, namely YUCCA2, YUCCA3, and THREAD/YUCCA4 also conferred a signature phenotype of yucca: elongated hypocotyls, epinastic leaves, severely weak and lanky inflorescences, increased apical dominance, and reduced fertility (Zhao et al., 2001; Marsch-Martinez et al., 2002). In contrast, the phenotype of super1-D was notably milder. For instance, the super1-D hypocotyls were shorter than that of yucca-D, and the super1-D cotyledons did not exhibit strong epinasty. Similarly, the adult phenotypes of super1-D in the presence of functional ER are vigorous and fertile with larger rosettes and inflorescences.

The difference in the growth phenotype between super1-D and other YUCCA overexpressors may reflect redundant but distinct roles of each YUCCA member during plant growth and development. One possibility is that the activation-tagged YUCCA5 leads to a relatively moderate increase in free IAA amounts in the inflorescence. This may be because the YUCCA5 enzyme is not as active as the other members. Alternatively, the super1-D mutation may not drive high expression of YUCCA5 as compared to other activation-tagged YUCCA genes. In wild-type plants, YUCCA5 is predominantly expressed in young vegetative tissues and roots (Fig. 5). Further analysis to correlate tissue-specific accumulation of activation-tagged transcripts and IAA among different yucca family mutants will be necessary to clarify these two possibilities. The recently developed technique of microscale IAA quantification in tissue sections (Mori et al., 2005) may enable direct comparison of tissue-specific auxin accumulation to the developmental phenotypes.

It has been reported that loss-of-function mutations in YUCCA and YUCCA2 confer no visible phenotype, most likely due to redundancy (Zhao et al., 2001). Therefore, a targeted disruption of multiple YUCCA-family genes including YUCCA5 by generating higher-order mutant/cosuppression lines may be required to further address the developmental roles of YUCCA-family genes and their interaction with ER.

Intersection of ER- and Auxin-Mediated Control of Inflorescence Architecture

While our screen did not identify novel ER-signaling components, it highlighted the intersection of ER- and auxin-mediated organ growth and internodal elongation, which in turn translates to inflorescence architecture. Previous studies have shown that both ER and auxin are required for elongation of the inflorescence and that they display synergism. For instance, a large-scale genetic screen for clustered, er-like inflorescence phenotype led to the isolation of 10 novel er-like1 mutants that are allelic to tir3 (Lease et al., 2001). Conversely, er was identified as an enhancer of attenuated shade avoidance1, which is also allelic to tir3 (Kanyuka et al., 2003). tir3 was originally isolated as a mutant resistant to the auxin polar transport inhibitors (Ruegger et al., 1997). TIR3 encodes a calossin-like protein BIG that is required for normal auxin distribution, presumably by affecting the cellular localization of the PIN family auxin efflux carriers (Gil et al., 2001). The complete suppression of the compact inflorescence phenotype of er-103 by activation tagging of YUCCA5 provides supporting evidence for complementary action of ER and auxin in promoting inflorescence elongation.

The effects of super1-D in promoting elongation of inflorescences and pedicels, as well as reducing fertility, are more pronounced in er plants than in wild-type plants (see Fig. 2), implying that er plants may be more sensitive to elevated levels of auxin. The mechanism by which er mutation confers elevated response to auxin-mediated growth is not clear. It is highly unlikely that ER directly affects auxin biosynthesis or homeostasis for the following reasons: First, er mutations do not significantly alter the endogenous levels of free IAA (Fig. 4). Second, the er mutations do not affect expression of auxin-responsive promoter activity of AtAux2-11::GUS during vegetative and inflorescence development under normal growth condition (data not shown; Wyatt et al., 1993; Abel et al., 1994; Ulmasov et al., 1997). Third, both wild-type and er-103 mutant plants responded similarly to the IAA application (Fig. 7), suggesting that the er mutations do not confer reduced sensitivity to the auxins. Finally, it has been reported that a single recessive mutation in ecotype Landsberg er confers inflorescence stem segments a responsiveness to IAA-stimulated cell elongation via activation of the plasma membrane proton pump, so-called acid growth (Soga et al., 2000). We repeated their experiments using er alleles in Landsburg as well as Columbia ecotypes, and ruled out the possibility that the er mutation is responsible for increased acid growth (S. Bemis and K. Torii, unpublished data).

The super1-D mutation conferred elongation of the epidermal pavement cells of both wild-type and er mutant pedicels to a similar extent (Fig. 9), while elongation of wild-type pedicels was not nearly as dramatic as er mutant pedicels (Fig. 2). This implies that it is not simply the extent of the epidermal cell elongation that specifies the overall elongation of pedicels as a whole. Unlike the epidermis, the cortex cell size was not altered by the super1-D mutation (Fig. 9). Therefore the sensitivity of er to super1-D may involve auxin-mediated cell proliferation.

Perhaps both auxin and ER promote inflorescence growth via largely independent pathways but with overlaps in their ultimate downstream processes (e.g. cell proliferation). Thus the excessive activity of either pathway may partly mask the loss of the other. Plant growth is under the control of both environmental stimuli and developmental programs. Multiple environmental and endogenous pathways may overlap or be redundant. Recently, the cross talk of hormone-signaling pathways has emerged as a central theme in plant growth regulation, as exemplified by the recent finding that interaction of auxin and brassinosteroids in promoting seedling growth occurs via transcriptional control of downstream targets (Goda et al., 2004; Nemhauser et al., 2004). Further studies, such as a genome-wide comparison of gene expression by auxin- and ER-signaling pathways may reveal the molecular basis of their intersections during growth and development of inflorescence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Col) was used as the wild type. The yucca recapitulated line is a generous gift from Dr. Yunde Zhao (University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA) and Dr. Joanne Chory (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA), and the AtAux2-11::GUS line is a generous gift from Dr. Masao Tasaka (NAIST, Ikoma, Japan). er-103, er-105, yucca, and AtAux2-11::GUS lines are all in the Col background. Plants were grown on soil mixtures (Sunshine Mix4:Vermiculite:Perlite = 2:1:1 with 0.85 mg/cm3 of Osmocoat14-14-14) under 18/6 light-dark cycle at 21°C. For plate cultures, seeds were surface sterilized with 30% bleach and 0.01% Triton X-100 (Sigma) for 12 min and subsequently washed five times with sterile distilled water. Seedlings were grown in Murashige and Skoog media supplemented with 1% (w/v) Suc.

Genotyping

The er-105 mutation was detected by using a primer pair ERg2248 (AAG AAG TCA TCT AAA GAT GTG A) and er-105rc (AGC TGA CTA TAC CCG ATA CTG A), and the absence of the wild-type allele was confirmed by a primer pair ERg2248 and ERg3016rc (AGA ATT TTC AGG TTT GGA ATC TGT). er-103 plants were genotyped using a primer pair ERg3588 (GAC TTG TCC TAC AAT CAG CTA ACT) and ERg4056rc (TAG ACC AGT CAG CTT GTT ACT GTG). The amplified fragment was subsequently digested with NlaIII to detect 3 cleaved amplified polymorphic sequences (CAPS): Bands obtained for wild type are 209 bp, 150 bp, 70 bp, and 65 bp; bands for er-103 are 274 bp, 150 bp, and 70 bp.

Isolation of super1-D Mutant and Recovery of the T-DNA Flanking Sequence

er-103 plants were vacuum infiltrated with the vector pSKI015 (a generous gift from Dr. Detlef Weigel; Weigel et al., 2000). super1-D was isolated as a suppressor from batch 38. An analysis of the subsequent generation revealed a segregation of Basta resistance to Basta-sensitive approximately 2:1 (suppressed phenoytpe: er-103 phenotype = 43:21; BastaR:BastaS = 43:21; all suppressed plants were BastaR and all er-103 phenotype plants were BastaS), indicating that it is activation tagged and presumably homozygous lethal. This was further confirmed by analysis of the F3 populations, where none of the populations derived from 15 independent super1-D plants carried homogygous Basta resistance. Therefore, morphological analysis was performed using the super1-D/+ plants.

The genomic DNA was isolated from 2-week-old super1-D plants using Nucleon Phytopure plant DNA extraction kit (Amersham Pharmacia LKB). The T-DNA flanking sequence of super1-D was recovered by the inverse-PCR (iPCR) as described by Li et al. (2001), except that both EcoRI and KpnI were used to digest the super1-D genomic DNA. The amplified fragments were cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and subjected to sequencing.

RNA and RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was prepared by using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and subsequently treated with DNaseI (Invitrogen) prior to the RT-PCR reaction. cDNA was synthesized from 0.2 mg of the total RNA by using Thermoscript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and a random hexiamer as a primer. One-fifth of the synthesized cDNA was used for the PCR reaction with a YUCCA5 gene-specific primer pair: May2FMO5 (cggaattccc ATG GAG AAC ATG TTT AGG CT) and May2FMO3rc (ccggatcc CTA AGC AAC TGA AAT GCA TC). The Arabidopsis actin (ACT2) gene was amplified as a template control using a primer pair: ACT2-1 (GCC ATC CAA GCT GTT CTC TC) and ACT2-2 (GCT CGT AGT CAA CAG CAA CAA).

Cloning of the YUCCA5 Coding Sequence and Generation of Transgenic Plants

The YUCCA5 cDNA was cloned into the EcoRI and BamHI sites of pSP73 (Promega) and the sequence was confirmed. The plasmid was partially digested with NcoI and BamHI and inserted into pRTL2-GUS to replace the GUS gene. This construct, which drives the YUCCA5 expression under a dual-enhanced CaMV35S promoter, was cloned into the HindIII site of pPZP222 (Hajdukiewics et al., 1994) to generate pEJH101. The plasmid was introduced into Agrobacterium strain GV3101 by electroporation and transformed into Arabidopsis er-103 plants by vacuum infiltration. Selection of the transgenic plants and segregation analysis in the next generation were conducted as described by Shpak et al. (2003).

Histological Analysis, Microscopy, and Cell Length Measurement

Fixation, embedding, and sectioning of tissues for light microscopy using Olympus BX40 were performed as described by Shpak et al. (2003). The GUS staining was performed according to Sessions et al. (1999). For clearing of hypocotyls and pedicels, tissues were placed in 9:1 ethanol:acetic acid solution at room temperature overnight, rehydrated through an ethanol series (85%, 70%, 50%, 30%, 15%) and then stored in chloral hydrate:water:glycerol 8:1:1. The cleared specimens were viewed under the differential interference contrast microscope Nikon Optishot equipped with a Sony DXC-960MD CCD video camera. The cortex cell length was measured directly on the photographic images of plastic sections. For measuring the epidermal pavement cell length, the pedicel epidermis was stripped with scarpel, photographed under phase contrast microscopy, and analyzed with Adobe Photoshop 7.

Auxin Treatment and GUS Activity Assay

Two-week-old seedlings were transferred from plates to full-strength Murashige and Skoog liquid media and incubated for 5 d with shaking (100 rpm) at 18-h-light/6-h-dark condition. Seedlings were then treated with 0, 1, 10, or 100 μm IAA (Sigma) for 6 h with shaking. Subsequently, 150 to 200 mg of plant tissue was ground in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in 500 μL extraction buffer containing 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 10 mm EDTA, 0.1% sodium laurylsarcosine, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol. The extracts were cleared by centrifugation at 12,000g at 4°C for 5 min. The protein content of the extracts was determined using a Bio-Rad Protein Assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. To measure GUS activity, 3 μL protein extract was mixed with 475 μL 2 mm 4-methylumbelliferyl β-d-glucuronide (in extraction buffer), and incubated at 37°C for 45 min. The reaction was stopped by mixing 50 μL of the mixture with 200 μL 0.2 m sodium carbonate. Fluorescence of the samples was measured at 360 (excitation) and 460 (emission) nm using a SynergyHT Multi-Detection microplate reader (BioTek).

Quantification of Free IAA Level

For gas chromatography, single-ion-monitoring mass spectrometry (GC-SIM-MS) analyses, fresh plant material (corresponding to a pool of 10 seedlings grown on agar plates for 7 d under continuous light) was carefully weighed, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. For extraction of free IAA, the material was ground in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle. After addition of 0.6 ng of [13C6]IAA (Cambridge Isotope Lab) as an internal standard, the material was extracted in 80% acetone and 0.1 mg/mL 2,6-Di-tret.-butyl-4-methylphenol for 60 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected. The pellet was reextracted again for 90 min, and the supernatant was brought to a water phase in a rotary evaporator. IAA was partially purified from the residual aqueous solution by partitioning using ether, and then purified by HPLC connecting with a fluorometer (Hitachi FL Detector L-7485; 280 nm excitation, 355 nm emmition). The HPLC was performed using a Nucleosil N(CH3)2 column (Senshu) with an isocratic system of 100% methanol and 0.03% acetic acid. The purified IAA fraction was dried under a nitrogen stream and trimethylsilylated with N-methyl-N-trimethylsilyltrifluoroacetamide at 60°C for 15 min.

Splitless injections were made into a GC-single-ion-monitoring-MS system (QP5050A, Shimazu), equipped with a capillary column (DB-1, 0.25 mm i.d.×30 m, film thickness 0.25 mm; J&W Scientific). A linear temperature gradient was applied from 80°C to 280°C with an increase of 20°C/min. The injection temperature of the GC was 250°C, the ion source temperature of the MS was 250°C, and a helium flow of 1.2 mL/min was applied. The ionization potential was 70 electron volt, and the scan time was 0.2 s. The percentages of molecules of IAA labeled with 13C were calculated from the relative intensities of m/z 202 to 208 and 319 to 325 ions after subtraction of background.

Upon request, all novel materials described in this publication will be made available in a timely manner for noncommercial research purposes, subject to the requisite permission from any third-party owners of all or parts of the material. Obtaining any permissions will be the responsibility of the requestor.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession number DQ159070.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Detlef Weigel for a generous gift of pSKI015 plasmid, Drs. Yunde Zhao and Joanne Chory for yucca seeds, Dr. Masao Tasaka for AtAux2-11::GUS seeds, and Drs. Robert Cleland, Elena Shpak, Jessica McAbee, and Lynn Pillitteri for commenting on the manuscript. We are thankful to Kensuke Yamazaki for his help on GC-MS analysis of IAA, May Chen-Lee and Maria Malzone for technical assistance in mutant screen and plasmid rescue, and Drs. Lynn Riddiford, Jay Hesselberth, and Bruce Godfrey for letting us use their equipment (a differential interference contrast microscope and a microplate reader).

This work was supported by the Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology, Japan Science and Technology Agency, and the U.S. Department of Energy (grant no. DE–FG02–03ER15448 to K.U.T.), and by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sport and Culture of Japan (grant no. 15031222 to T.K.). K.U.T. was a University of Washington ADVANCE Professor (National Science Foundation/ADVANCE Cooperative Agreement no. SBE–0123552).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.105.063495.

References

- Abel S, Oeller PW, Theologis A (1994) Early auxin-induced genes encode short-lived nuclear proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 326–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azpiroz R, Wu Y, LoCascio JC, Feldmann KA (1998) An Arabidopsis brassinosteroid-dependent mutant is blocked in cell elongation. Plant Cell 10: 219–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carles CC, Fletcher JC (2003) Shoot apical meristem maintenance: the art of a dynamic balance. Trends Plant Sci 8: 394–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrispeels MJ, Sadava DE (1994) Plants, Genes, and Agriculture. Jones and Bartlett, Boston, pp 298–327

- Diévart A, Clark SE (2004) LRR-containing receptors regulating plant development and defense. Development 131: 251–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doebley J, Stec A, Hubbard L (1997) The evolution of apical dominance in maize. Nature 386: 485–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas SJ, Chuck G, Dengler RE, Pelecanda L, Riggs CD (2002) KNAT1 and ERECTA regulate inflorescence architecture in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 14: 547–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann KA, Marks MD, Christianson ML, Quatrono RS (1989) A dwarf mutant of Arabidopsis generated by T-DNA insertion. Science 243: 1351–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridborg I, Kuusk S, Robertson M, Sundberg E (2001) The Arabidopsis protein SHI represses gibberellin responses in Arabidopsis and barley. Plant Physiol 127: 937–948 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil P, Dewey E, Friml J, Zhao Y, Snowden KC, Putterill J, Palme K, Estelle M, Chory J (2001) BIG: a calossin-like protein required for polar auxin transport in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 15: 1985–1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda H, Sawa S, Asami T, Fujioka S, Shimada Y, Yoshida S (2004) Comprehensive comparison of auxin-regulated and brassinosteroid-regulated genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 134: 1555–1573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajdukiewics P, Svab Z, Maliga P (1994) The small, versatile pPZP family of Agrobacterium binary vectors for plant transformation. Plant Mol Biol 25: 989–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzawa Y, Takahashi T, Michael AJ, Burtin D, Long D, Pineiro M, Coupland G, Komeda Y (2000) ACAULIS5, an Arabidopsis gene required for stem elongation, encodes a spermine synthase. EMBO J 19: 4248–4256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P, Proebsting WM (1999) Genetic analysis of gibberellin biosynthesis. Plant Physiol 119: 365–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakimoto T (1996) CKI1, a histidine kinase homolog implicated in cytokinin signal transduction. Science 274: 982–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanyuka K, Praekelt U, Franklin KA, Billingham OE, Hooley R, Whitelam GC, Halliday KJ (2003) Mutations in the huge Arabidopsis gene BIG affect a range of hormone and light responses. Plant J 35: 57–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komeda Y, Takahashi T, Hanzawa Y (1998) Development of inflorescneces in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Plant Res 111: 283–288 [Google Scholar]

- Lease KA, Wen J, Li J, Doke JT, Liscum E, Walker JC (2001) A mutant Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G-protein beta subunit affects leaf, flower, and fruit development. Plant Cell 13: 2631–2641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyser HM, Lincoln CA, Timpte C, Lammer D, Turner J, Estelle M (1993) Arabidopsis auxin-resistance gene AXR1 encodes a protein related to ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1. Nature 364: 161–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Chory J (1997) A putative leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase involved in brassinosteroid signal transduction. Cell 90: 929–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Lease KA, Tax FE, Walker JC (2001) BRS1, a serine carboxypeptidase, regulates BRI1 signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 5916–5921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Nagpal P, Vitart V, McMorris TC, Chory J (1996) A role for brassinosteroids in light-dependent development of Arabidopsis. Science 272: 398–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln C, Britton JH, Estelle M (1990) Growth and development of the axr1 mutants of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2: 1071–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch-Martinez N, Greco R, Van Arkel G, Herrera-Estrella L, Pereira A (2002) Activation tagging using the En-I maize transposon system in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 129: 1544–1556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi Y, Yang H, Sakagami Y (2001) Peptide signals and their receptors in higher plants. Trends Plant Sci 6: 573–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mele G, Ori N, Sato Y, Hake S (2003) The knotted1-like homeobox gene BREVIPEDICELLUS regulates cell differentiation by modulating metabolic pathways. Genes Dev 17: 2088–2093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori Y, Nishimura T, Koshiba T (2005) Vigorous synthesis of indole-3-acetic acid in the apical very tip leads to a constant basipetal flow of the hormone in maize coleoptile. Plant Science 168: 467–473 [Google Scholar]

- Nemhauser JL, Mockler TC, Chory J (2004) Interdependency of brassinosteroid and auxin signaling in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol 2: E258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski N, Sun TP, Gubler F (2002) Gibberellin signaling: biosynthesis, catabolism, and response pathways. Plant Cell Suppl 14: S61–S80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Carol P, Richards DE, King KE, Cowling RJ, Murphy GP, Harberd NP (1997) The Arabidopsis GAI gene defines a signaling pathway that negatively regulates gibberellin responses. Genes Dev 11: 3194–3205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Richards DE, Hartley NM, Murphy GP, Devos KM, Flintham JE, Beales J, Fish LJ, Worland AJ, Pelica F, et al (1999) ‘Green revolution’ genes encode mutant gibberellin response modulators. Nature 400: 256–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruegger M, Dewey E, Hobbie L, Brown D, Bernasconi P, Turner J, Muday G, Estelle M (1997) Reduced naphthylphthalamic acid binding in the tir3 mutant of Arabidopsis is associated with a reduction in polar auxin transport and diverse morphological defects. Plant Cell 9: 745–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Pearce G, Scheer JM, Moura DS (2002) Polypeptide hormones. Plant Cell (Suppl) 14: S251–S264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz EA, Haughn GW (1991) LEAFY, a homeotic gene that regulates inflorescence development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 3: 771–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessions A, Weigel D, Yanofsky MF (1999) The Arabidopsis thaliana MERISTEM LAYER 1 promoter specifies epidermal expression in meristems and young primordia. Plant J 20: 259–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpak ED, Berthiaume CT, Hill EJ, Torii KU (2004) Synergistic interaction of three ERECTA-family receptor-like kinases controls Arabidopsis organ growth and flower development by promoting cell proliferation. Development 131: 1491–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpak ED, Lakeman MB, Torii KU (2003) Dominant-negative receptor uncovers redundancy in the Arabidopsis ERECTA leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase signaling pathway that regulates organ shape. Plant Cell 15: 1095–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soga K, Wakabayashi K, Hoson T, Kamisaka S (2000) Flower stalk segments of Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia lack the capacity to grow in response to exogenously applied auxin. Plant Cell Physiol 41: 1327–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobeña-Santamaria R, Bliek M, Ljung K, Sandberg G, Mol JNM, Souer E, Koes R (2002) FLOOZY of petunia is a flavin mono-oxygenase-like protein required for the specification of leaf and flower architecture. Genes Dev 16: 753–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii KU (2004) Leucine-rich repeat receptor kinases in plants: structure, function, and signal transduction pathways. Int Rev Cytol 234: 1–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii KU, Hanson LA, Josefsson CAB, Shpak ED (2003) Regulation of inflorescence architecture and organ shape by the ERECTA gene in Arabidopsis. In T Sekimura, ed, Morphogenesis and Patterning in Biological Systems. Springer-Verlag, Tokyo, pp 153–164

- Torii KU, Mitsukawa N, Oosumi T, Matsuura Y, Yokoyama R, Whittier RF, Komeda Y (1996) The Arabidopsis ERECTA gene encodes a putative receptor protein kinase with extracellular leucine-rich repeats. Plant Cell 8: 735–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T, Murfett J, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ (1997) Aux/IAA proteins repress expression of reporter genes containing natural and highly active synthetic auxin response elements. Plant Cell 9: 1963–1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZY, Nakano T, Gendron J, He J, Chen M, Vafeados D, Yang Y, Fujioka S, Yoshida S, Asami T, et al (2002) Nuclear-localized BZR1 mediates brassinosteroid-induced growth and feedback suppression of brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Dev Cell 2: 505–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZY, Seto H, Fujioka S, Yoshida S, Chory J (2001) BRI1 is a critical component of a plasma-membrane receptor for plant steroids. Nature 410: 380–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel D, Ahn JH, Blazquez MA, Borevitz JO, Christensen SK, Fankhauser C, Ferrandiz C, Kardailsky I, Malancharuvil EJ, Neff MM, et al (2000) Activation tagging in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 122: 1003–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt RE, Ainley WM, Nagao RT, Conner TW, Key JL (1993) Expression of the Arabidopsis AtAux2-11 auxin-responsive gene in transgenic plants. Plant Mol Biol 22: 731–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Christensen SK, Fankhauser C, Cashman JR, Cohen JD, Weigel D, Chory J (2001) A role for flavin monooxygenase-like enzymes in auxin biosynthesis. Science 291: 306–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]