RESUME

Depuis des décennies, la participation communautaire (PC) dans les soins de santé primaires (SSP) et les programmes de santé (PS) joue un rôle crucial dans l’amélioration des services de santé et leur pérennité. Cet article analyse les réussites et les défis de la PC dans la région de l’Autorité intergouvernementale pour le développement (IGAD), qui inclut Djibouti, l’Éthiopie, l’Érythrée, le Kenya, la Somalie, le Soudan, le Soudan du Sud et l’Ouganda, en se concentrant sur les facteurs d’influence et les niveaux d’engagement communautaire. Cette étude s’appuie sur une revue de la portée (scoping review) basée sur le cadre d’Arksey et O’Malley et sur le spectre de participation publique de l’IAP2. Une recherche exhaustive a été réalisée dans PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science et Google Scholar pour les études publiées jusqu’en avril 2024. Les articles pertinents sur les mécanismes de PC dans les SSP et les PS de la région IGAD ont été sélectionnés. Au total, 64 articles ont été inclus dans cette revue. Les études soulignent diverses formes et mécanismes de participation communautaire, comme la création de comités de santé communautaires et la mobilisation de volontaires. Parmi les réussites notables figurent l’amélioration de la prévention des maladies, la gestion des crises, le renforcement de la résilience des communautés et l’accès aux services de santé maternelle et infantile. Cependant, des défis persistent, tels que les lacunes en matière de communication, la limitation des ressources, les barrières culturelles et l’instabilité politique. La participation communautaire est indispensable au succès des programmes de santé dans la région IGAD. Bien que des progrès significatifs aient été réalisés, il reste nécessaire de relever les défis persistants pour optimiser l’impact et la pérennité des initiatives de participation communautaire.

ABSTRACT

For decades, community participation (CP) in primary health care (PHC) and health programs (HP) has played a crucial role in improving health services and their sustainability. This article examines the successes and challenges of CP in the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) region, which includes Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, and Uganda, focusing on the factors influencing and levels of community engagement. This study employs a scoping review based on the Arksey and O'Malley framework and the IAP2 public participation spectrum. A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar for studies published up to April 2024. Relevant articles on CP mechanisms in PHC and HP in the IGAD region were selected. In total, 64 articles were included in this scoping review. The studies highlighted various forms and mechanisms of CP, such as the establishment of community health committees and the mobilization of volunteers. Successes included improvements in disease prevention, crisis management, community resilience, and access to maternal and child health services. However, challenges remain, such as communication gaps, resource limitations, cultural barriers, and political instability. Community participation is essential for the success of health programs in the IGAD region. Although significant progress has been made, persistent challenges must be addressed to optimize the impact and sustainability of CP initiatives.

Introduction

In 1978, the Alma-Ata Declaration marked a global recognition of the essential importance of community involvement in primary healthcare (PHC) and health programs (HP).

This declaration emphasized disease prevention and health promotion through active community participation, encouraging them to play a key role in safeguarding their own health and wellbeing (1, 2).

More recently, this participatory approach has been integrated into strategies aimed at achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), becoming a central element of rights-based health methods and the social determinants of health (3, 4).

During the Astana Declaration in 2018, nations worldwide, including those in the IGAD region, renewed their political commitment.

They reaffirmed their determination to promote active participation and engagement of their communities in PHC and HP, while aiming to empower these communities (5).

The Intergovernmental Authority on Development(IGAD) is a regional organization in East Africa founded in 1986, composed of eight member countries: Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan and Uganda.

Figure 1. The intergovernmental authority on development member countries .

These countries have diverse socio-economic and health contexts but share common goals in development and public health.

IGAD's geopolitical importance lies in its ability to promote regional stability and facilitate cooperation among member states, while its socioeconomic significance is evident through initiatives aimed at improving infrastructure, natural resource management, and health services in the region.

These efforts are crucial for sustainable development and the well-being of local populations (6).

One of IGAD's flagship missions is to promote public health and social development in the region.

In this context, IGAD undertakes PHC initiatives and funds HP aimed at developing and improving health services and the quality of care delivery (7).

These efforts seek to expand health coverage, address disparities in access to care in the region, and promote the right to health and social well-being.

Health is perceived not only as a fundamental human right but also as a determinant of community productivity (CP) and resilience (8).

To achieve this mission, it is crucial for member countries, with the support of IGAD authorities, to adopt the concept of CP, Community participation is defined as a process that actively involves community members in the design, implementation and evaluation of health interventions.

Its main aim is to strengthen their commitment and capacity to make a significant contribution to improving their collective health and well-being.

CP refers to the active involvement of community members in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of health interventions.

This includes consulting communities to identify their needs, collaborating to design relevant programs, and their direct participation in health activities (9).

This approach goes further, creating a continuous partnership between health services and communities, empowering members and strengthening their health autonomy (10).

These mechanisms of CP can be distributed on a continuum, ranging from minimal participation (receiving information) to active participation (delegation and empowerment) (11).

A fundamental element of CP is the application of appropriate levels of engagement in a given context.

Although CP is widely accepted in theory and practice in the IGAD region countries, notable differences persist in its implementation.

Various challenges continue to hinder the success of these initiatives, despite their essential role in improving the quality of health services and interventions, their sustainability, and public health in general.

What must be kept in mind is that, in public health, community participation refers to the involvement of community members in the processes of decisionmaking, implementation, and evaluation of health interventions, generally in a consultative or contributory role, but without actual decision-making power.

In contrast, community engagement is characterized by a deeper involvement, where the community takes on a leadership role and participates in the co-management of health initiatives.

The key distinction lies in the degree of empowerment: community participation offers a consultative voice, while community engagement promotes the sharing of power and responsibilities, thus creating a true partnership with local stakeholders.

This study aims to explore the main successes and challenges associated with CP initiatives implemented in the fields of PHC and HP within the IGAD region countries.

Additionally, it seeks to identify factors influencing community engagement (CE) and assess the level of this engagement.

The results of this study could serve as a valuable source of information and documentation for IGAD authorities, allowing them to adjust CP approaches and contextualize them according to local needs.

Figure 2. IAP2 spectrum of public participation .

Methods

This study presents a scoping review of the scientific literature on CP initiatives in PHC and HP within the member countries of the IGAD region.

We applied the Arksey and O'Malley methodological framework and the IAP2 Public Participation Spectrum evaluation model(inform, consult, involve, collaborate, and empower) to conduct this exploratory review.

This methodology enabled us to identify the successes and challenges related to CP, as well as the influencing factors and to evaluate the levels of engagement (12, 13).

To ensure a comprehensive presentation of the methods and results, we used the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and MetaAnalyses Extension for Scoping Reviews) checklist (14).

Identifying the research question

The scoping review was structured around one main question and two secondary sub-questions.

The main question is as follows: What are the successes and challenges associated with the Community Participation(CP) approach in Primary Health Care (PHC) and health programs?

Two secondary sub-questions complement this main inquiry: What are the factors influencing the effectiveness of Community Participation in these contexts? and What is the level of community engagement within the Community Participation approach?

Identifying relevant studies

We conducted a search in major electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, between March 15, 2024, and April 13, 2024.

The search focused on articles published in English since the creation of each database.

The search strategy included the use of combinations of relevant terms and keywords, such as "" community participation," ""community involvement," ""community engagement," ""citizen participation," ""primary health care," and ""health programs," along with the names of all countries in the IGAD region.

Keywords were combined using Boolean operators (AND, NOT, OR) to develop or refine the search parameters, quotation marks (" "") to obtain results with exact phrases, and parentheses to group search terms(supplementary file 1, table 1 (On Line)).

Selection of studies

All articles included in this literature review met the following criteria:

i. The study had to focus on one or more countries in the IGAD region, namely Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, Djibouti, South Sudan, Somalia, Sudan, or Eritrea;

ii. The studies had to address the mechanisms and approaches of CP in PHC and health programs HP;

iii.The articles had to be published in the English language;

iv. Publications had to be dated before the end of the search period in the electronic databases.

Studies were included if their results addressed our research question, regardless of the individual quality of the studies.

The selection of articles was carried out in several stages.

Initially, articles were automatically selected by applying specific search strategies in the databases.

The obtained references were then exported to Zotero, where duplicates were removed.

After this elimination, the remaining references were screened based on the eligibility criteria.

The first screening involved an assessment of the articles based on the reading of titles and abstracts.

Articles selected at this stage were then subjected to a full-text reading for final inclusion.

The initial selection, based on title and abstract, was performed by the first author and then reviewed by other authors.

The selection of full texts was first conducted by the first author, then evaluated by the other authors.

Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with the last author.

Data Extraction, Synthesizing and Presenting Findings

First, a data extraction and mapping sheet was developed by the authors to collect information for each study, such as the authors, year, country, type of study, method employed, study objectives, main findings, and authors' conclusions (supplementary file 1, table 1).

The data were extracted by the first author and verified by other authors.

Two additional data extraction tables were also developed: one to identify the factors influencing community Participation and the other to evaluate the level of engagement according to the framework of the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2), based on the information and data from the studies included in our review (supplementary file 2, table 1).

After extracting the relevant information, the data were described in a narrative and descriptive manner, grouped into five main themes: characteristics of the included studies, different formats of CP mechanisms, factors influencing CE, comparative analysis, and evaluation of the level of engagement according to the IAP2 framework.

Results

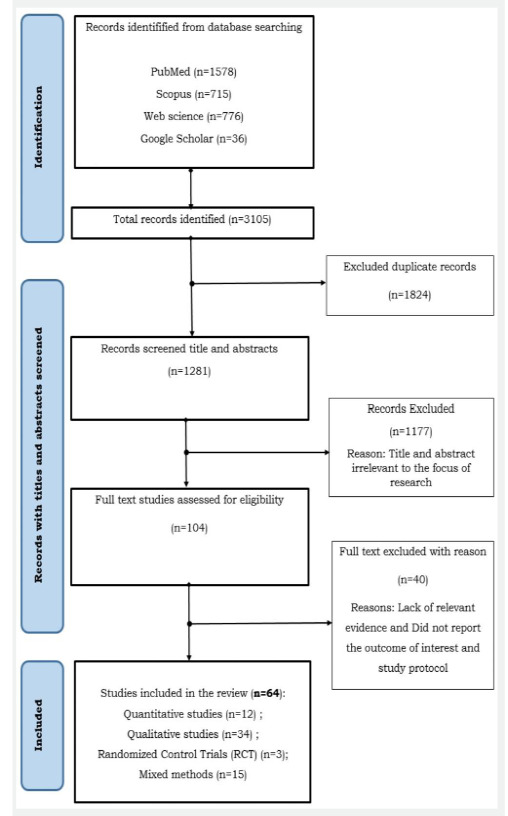

The results of our research identified 1,578 articles in PubMed, 715 in Scopus, 776 in Web of Science, and 36 in Google Scholar.

After removing duplicates, 1,281 articles were retained. Screening of titles and abstracts determined that 104 articles met the selection criteria.

However, a thorough analysis of the full texts led to the exclusion of an additional 40 articles.

Consequently, 64 articles were included in the final review.

The primary reasons for exclusion included a lack of focus on the study subject, absence of relevant new evidence, failure to report outcomes of interest, and limitations of study protocols.

Figure 3. PRISMA-ScR flow chart showing the selection of studies for the review .

Characteristics of included studies

The articles included in our scoping review exhibit various characteristics, particularly concerning their type, the applied method, and the country where the research was conducted.

Regarding the type of article, fifty-one are original research articles, four are case studies, two are narrative reviews, one is a perspective or opinion, three are brief research reports, and three are technical reports.

These studies cover a wide range of methodologies, including twelve quantitative studies, thirty-four qualitative studies, fifteen mixed-methods studies, and three randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

In terms of the distribution of articles by the countries where the studies were conducted, fourteen studies were conducted in Ethiopia with one multicentric study (Brazil and Sri Lanka), three in Djibouti, three in Somalia with one multicentric study (Kenya and South Sudan), four in Eritrea, fifteen in Uganda with one multicentric study in South Africa, fourteen in Kenya with four multicentric studies( Kenya, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Uganda, ) involving various countries, six in South Sudan, and six in Sudan.

The articles address the implementation approach of CP in the IGAD region within these two studied concepts: PHC and HP.

They explore various aspects of these components, including health promotion and prevention, health education, an integrated approach(hygiene, drinking water, maternal and child health, nutrition, vaccination, safety), accessibility, and equity.

Additionally, they discuss communication strategies, CE, assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and practices(KAP), as well as epidemiological surveillance and health information technology (HIT).

The articles also examine the management of chronic and vector-borne diseases, training of community health workers, health system governance, capacity building of civil society networks.

Finally, they cover ethical research, health system strengthening, health planning and financing, environmental sanitation, and legislative and legal frameworks. (Supplementary file 1, Table 1).

Figure 4. Distribution of articles by type, methodology, and country in a scoping review .

The Various Forms and Mechanisms of CP

CP in the countries of the IGAD region primarily manifests in two ways: through the creation and implementation of community health committees or working groups, or through individual, voluntary, spontaneous, and provisional engagement by local population members.

These two mechanisms play a crucial role in various participatory functions, whether they are informational, consultative, operational, decision-making, financial, or related to monitoring and evaluation.

It is also possible to combine these two mechanisms to maximize the effectiveness of CP.

Creation and Implementation of Community Health Committees, Councils, or Groups

In several countries within the IGAD region, committees, working groups, or advisory councils have been established, selected either by health authorities or by the community itself based on its level of engagement. The results of our study indicate, for example, that in Kenya, there are Community Health Committees (CHCs), Community Advisory Committees (CACs), and Community Advisory Groups (CAGs) (15-18 ).

In Uganda, there are Village Health Teams, Community Advisory Boards, and Health Unit Management Committees (19) (20, 21 ).

In Ethiopia, there are Social Affairs Committees, the Health Development Army (HDA), and Pregnant Women Forums (PWF) (22 -24).

In South Sudan, there are Boma Health Committees and the Implementation Coordination Committee (25).

In Somalia, there is the Nutrition Cluster (26 ).

Community health committees and working groups share common objectives and roles essential for facilitating CP in identifying health problems, setting priorities, and planning activities within their local communities.

Their involvement extends to raising awareness among the population, providing guidance to promote preventive management and healthy behaviors to preserve health and well-being.

They ensure that the community’s needs are addressed by working closely with local health facilities.

Their role also includes supporting the implementation of health initiatives and ensuring that health interventions are adapted to local realities and expectations.

The distinctive feature of this mechanism lies in the ongoing and continuous collaboration between committees, working groups, health professionals, and community health workers.

Mobilizing community volunteers

This second mechanism relies on the spontaneous and temporary engagement of local community members, who offer their time and skills.

Their motivation stems from their desire to contribute to the health and wellbeing of their community.

However, this engagement is limited in time and scope, for example, during a crosssectional epidemiological survey to collect information on a specific disease, such as in Djibouti for the hemorrhagic fever virus in 2010 and 2011, or during a health crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic in Uganda, Ethiopia and Djibouti (27-29).

In Eritrea, in the villages of Gash Barka, the inhabitants, primarily women (75.5%), actively collaborated to combat malaria.

Among adult household members (> 15 years), 67.3% participated in environmental sanitation activities.

Additionally, 7.9% of respondents took part in larval habitat management initiatives, such as filling or draining water bodies and eliminating stagnant water (30, 31).

Successes and Challenges Related to Community Participation

Successes of Community Participation

The results of our review highlighted several improvements associated with CP approaches implemented by IGAD member countries.

A well-managed and well-understood community participation is fundamental for the improvement of health programs and primary healthcare (32).

By actively involving community members in the planning and implementation of health initiatives, services become better tailored to local needs, fostering ownership and engagement among the population, over time, activities achieve greater sustainability, thereby ensuring their longevity and long-term impact.

This approach also enhances cooperation and responsibility among community members in promoting their own health, ultimately leading to improved overall health outcomes (33, 34).

The following are examples of positive impacts of CP on PHC and HP.

Prevention, Disease and Health Crisis Management, and Strengthening Community Resilience

The results of our review highlighted several improvements associated with CP approaches implemented by IGAD member countries.

These improvements notably concern disease prevention and control, community resilience, trust in institutions, CE, as well as preventive knowledge and practices in managing infectious diseases.

These advances are attributed to intensive awareness and training efforts (35, 46 ).

Targeted initiatives were carried out by committees, working groups, associations, volunteers, and local community members, as well as by community health workers (CHWs) and other civil society actors.

Together, they organized health education, information, and training campaigns, thus strengthening their resilience and local governance.

For example, during the Ebola hemorrhagic fever outbreaks, in the fight against malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, neglected tropical diseases, and the COVID-19 pandemic (41, 55).

The use of media, including radio, television, and social networks, was a key information channel for these campaigns (24 , 40, 56, 58).

In Ethiopia, 681 volunteers chosen by their communities were trained to fight malaria, and 81,781 community resident volunteers participated in environmental activities between July 1993 and June 1994 ( 22).

CHWs organized regular home visits for the surveillance of suspected tuberculosis cases (59).

In Uganda, a significant increase in coverage for malaria treatment (+23%), pneumonia (+19%), and diarrhea (+13%) was observed in intervention districts (56) (60 ).

Continuous awareness and education of community leaders enhanced the understanding and acceptance of genetic and genomic studies (61).

In Eritrea, a decrease in malaria incidence (from 33 to 5 per 1000 inhabitants) was observed, with 91% of households using insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), and a reduction in mortality rate (30, 31, 62 , 63).

In South Sudan, the seroprevalence of trypanosomiasis decreased from 9% to 2% between 1997 and 1999 (64), and the capacities of 250 Red Cross volunteers and 27 village health committees (Boma) were strengthened (65).

In Sudan, preventive practices showed moderate improvement: about 55% of participants adopted patient isolation as a preventive measure, 55.4% adopted the use of personal protective equipment (PPE), and 62.7% adopted good corpse management practices (66).

In the Gezira State, about 70% of the population stopped practicing female genital mutilation (FGM) thanks to the Saleema campaign (67).

Community Participation (CP) played a central role in the success of the Saleema campaign by fostering open and inclusive dialogue.

The campaign focused on raising awareness and directly involving community members at all levels, including religious leaders, local leaders, families, and women.

Saleema allowed these groups to actively participate in decision-making and discussions about abandoning female genital mutilation (FGM), by addressing their concerns and elevating local voices.

The campaign also utilized participatory methods, such as group discussions, community events, and training sessions, to encourage families to understand the risks associated with FGM and adopt new, positive cultural norms

The success of the initiative lies in the community's ownership of the message, making the fight against FGM a grassroots initiative rather than an externally imposed one.

This approach contributed to lasting social change and collective adherence to new practices.

In Kenya, CP enabled 93% of participating parents to wish for their children to remain involved in the study one year after enrollment, indicating increased trust in trial staff (57).

Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) programs were adopted by most counties to prevent open defecation and reduce worm transmission (42).

Improving Access, Utilization, and Coverage of Healthcare Services

In South Sudan, six primary healthcare (PHC) units were constructed and equipped as part of the community project, thus improving healthcare access for 90% of the population in Mayendit County (25 ).

Community Participation (CP) played a key role in this initiative by mobilizing community members to identify local needs and participate in the planning and implementation of healthcare infrastructure.

Thanks to this participatory approach, healthcare services were better adapted to local realities, leading to improved access to care and greater acceptance of services by the population.

Healthcare coverage was also strengthened through CP, with each region required to have a community health worker for 4,000 people in sedentary areas and for 1,500 nomads (1977/78-1983/84) (68).

This community-based approach allowed for a more equitable distribution of healthcare services, taking into account the specific needs of nomadic populations.

The participation of the communities in the creation and management of these services increased their engagement and the sustainability of the interventions.

In Ethiopia, the use of maternal health services increased significantly (23, 39 , 69).

This increase is a direct result of the Health Extension Program (HEP), which relies heavily on CP. The HEP trained community health workers from within the communities themselves, who played a crucial role in raising awareness and supporting pregnant women.

This helped to build trust in the healthcare system, increase the use of healthcare centers, and raise PHC coverage from 76.9% in 2005 to 90% in 2010 (35).

Community ownership and the direct involvement of its members largely contributed to the success of this initiative.

In Uganda, non-state actors (NSA) conducted home visits to assess the health needs of children and the male partners of pregnant women (60, 51 ).

Community Participation actively involved families in prenatal care and raised awareness among men, who are often excluded from these discussions.

By involving the entire family, including men, in maternal health, CP improved the rate of prenatal consultations and facility-based deliveries through a better understanding of health issues (52 ).

In Kenya, Community Participation (CP) improved access to health services by increasing the number of healthcare professional visits to remote areas by 35% (15).

This success was due to the strong involvement of communities in identifying healthcare needs and their active participation in organizing medical visits.

Mutual trust between healthcare professionals and communities was strengthened through this approach, making the interventions more effective and sustainable.

Additionally, the coverage of pregnant women receiving two doses of intermittent preventive treatment for malaria increased from 47% to 63%, a 34% rise (70), thanks to awareness-raising efforts by community health workers, who themselves were community members.

The involvement of the community in the fight against malaria encouraged better adoption of preventive practices.

In all these examples, CE and CP have been essential levers for ensuring that healthcare services meet local needs, enhancing community participation, and guaranteeing the sustainability of the results achieved.

Promotion of Maternal and Child Health

The improvement in effective coverage of acute malnutrition services in Somalia has been notable (71, 72).

In this context, Community Engagement (CE) played a crucial role.

Community leaders were mobilized to raise awareness among families about the signs of malnutrition and guide them to treatment centers.

The active involvement of community members made it possible to identify a greater number of malnourished children and ensure they received proper follow-up care.

By working closely with health workers, communities not only facilitated access to services but also contributed to disseminating safer nutritional practices and interventions.

This participatory approach strengthened local awareness, expanded service coverage, and led to a significant improvement in addressing acute malnutrition.

In Ethiopia, vaccination coverage saw a substantial increase thanks to CE.

For instance, coverage for the pentavalent-3 vaccine increased from 63% to 84% in Assosa and from 78% to 93% in Bambasi between January 2013 and December 2016

Measles vaccination coverage also rose, from 77% to 81% in Assosa and from 59% to 86% in Bambasi over the same period.

CE was central to these improvements, with the mobilization of community health workers and local leaders.

These actors raised awareness among families about the importance of vaccination, conducted active follow-ups for children, and encouraged women to engage in prenatal care.

Consequently, the adoption of modern family planning methods also increased significantly, from 12% to 93% in Assosa and from 18% to 62% in Bambasi between January and December 2016.

In both regions, prenatal visit coverage also improved: in Assosa, it rose from 60% in June 2013 to 76% in June 2016, and in Bambasi,from 67% to 95% over the same period (35)

The active participation of communities helped better integrate health services into the daily lives of the population, thereby strengthening trust in the healthcare system and improving maternal and child health indicators.

In Uganda, the active involvement of men in maternal and child health, facilitated by CE, improved health outcomes for mothers and children (20, 40 ).

Similarly, in Kenya, CE increased the percentage of pregnant women attending four prenatal visits, from 14% to 31%, a rise of 116%.

Moreover, Vitamin A supplementation for children increased from 17% to 39%, a 130% increase.

The vaccination coverage for fully immunized children also improved, rising from 65% to 99%, an increase of 53% (70 ).

This success is attributed to the strong involvement of communities in the implementation of health programs, leading to greater adoption of preventive practices and a general improvement in public health outcomes

Equity, Cost Reduction, and Resource Optimization

In Sudan, volunteer labor for construction work, fundraising for social and educational services, and materials for the construction of PHC units reduced costs (68).

Gender equity was strengthened through the participation of women via the Food Relief Committees and transparency initiatives (74).

Women represent 75% of health instructors (murshidat) and 40% of village health committees (VHCs) (75, 24).

In Ethiopia, communities participate in the election of CHWs, the implementation of program activities, and the evaluation of CHW performance (22, 38 , 39).

In Uganda, mobilizing community members led to the formation of 34 associations, training them in credit access and management to support income-generating projects (60).

Social networks were enhanced, and social cohesion was promoted through sports events and national day commemorations.

Community savings and credit systems and insurance schemes for obstetric emergencies were established (76).

The cost of training CHWs and community supervisors has decreased over the years, making the process more economical (77 ).

For example, in Uganda, NSAs helped reduce HIV-related stigma and improve trust between communities and health systems (51 ).

The protection of community rights and interests and the development of a rights-based approach were strengthened (41) (21).

In Kenya, communities successfully mobilized local resources, reducing their dependence on external funding and increasing the resources available for health initiatives by 25% (15, 54).

The Key Challenges in Community Mobilization

In the context of community mobilization and engagement within the IGAD member countries, numerous major challenges have been identified, complicating collaborative and development initiatives.

These challenges include communication defects, such as unclear messaging, inadequate choice of communication channels, poor synchronization, lack of feedback and insufficient active listening, as well as limited accessibility to information (15, 19, 25, 27, 40 , 43, 53, 67, 75).

Past negative experiences, lack of motivation, and unmanaged adverse effects of an intervention, such as resistance to indoor spraying due to allergies and unpleasant insecticide odors, further complicate these efforts (17, 19 , 38, 39, 44, 49, 50, 57, 67 , 75, 77).

Additionally, there is sometimes a lack of trust from the community towards community health workers and healthcare providers, as well as misconceptions due to cultural beliefs and taboos (17-20, 22 -24, 27 , 36, 40, 41, 51-53, 55, 57 , 58, 67, 75, 76, 78).

These difficulties are further amplified by political instability and security issues related to armed conflicts and civil war that plague the region (22, 26 , 35, 36, 47, 65, 72, 78, 79 ).

Furthermore, the limited skills of community health workers, the low level of knowledge and education in the community, language barriers, as well as social exclusion and marginalization of certain societies in the region, pose significant challenges.

On the other hand, notable challenges include the lack of material resources, such as insufficient medical equipment, inadequate infrastructure, and limited training materials.

Financial constraints, such as restricted budgets and insufficient financial support, also represent major obstacles.

Additionally, transportation and logistics issues hinder the massive participation of the community (17, 22, 26 , 42, 43, 49, 56, 59, 68, 69 , 76, 78).

Another major challenge lies in the weak engagement of state institutions and partners, as well as the absence of policy standards and legislative frameworks ( 55 ) (50 ).

Furthermore, spatial disparities and limited accessibility to health facilities, especially in rural and remote areas, exacerbate these difficulties (22, 26 , 36, 39, 47, 49, 50- 52, 58 , 59, 64, 66, 70, 72, 76, 77 ).

Deterrent and Incentive Factors for Community Engagement

To maximize community participation and ensure the success and sustainability of health programs in IGAD member countries, it is essential to understand and manage certain influencing factors.

The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes that CE is a social process that integrates physical, emotional, mental, social, and spiritual dimensions.

It is crucial to incorporate the social determinants of health into the design and delivery of health services, which enhances the well-being of healthcare workers, service users, and the broader communities (80 , 81).

Table 1. Deterrent and Incentive Factors in Community Participation .

Assessment of the Level of CP According to the IAP2 Framework

The results of this study show significant disparities among IGAD member countries regarding the availability of peer-reviewed scientific studies, the application of the CP concept in various health fields, and the levels of CE according to the spectrum of the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2).

Specifically, the access, availability, and publication of peer-reviewed scientific studies examining CE and participation in PHC and HP are very limited or moderate in countries such as Eritrea, Somalia, Djibouti, South Sudan, and Sudan.

In contrast, Kenya, Ethiopia, and Uganda have more studies and scientific publications, as well as evaluation programs, documenting CE and participation in various health fields in these countries.

These countries in the region widely integrate the concept of CE in various health fields, such as the management and control of epidemics and pandemics, the improvement and evaluation of health services, capacity building, community resilience, and program implementation, among others.

Conversely, Kenya, Ethiopia, and Uganda stand out for their more advanced use of this concept, particularly through the conduct of clinical research, vaccine trials, ethics, and the study of social determinants of health (44, 57, 21, 41 , 61, 56 ).

According to the engagement spectrum of the International Association for Public Participation, all IGAD countries effectively manage the levels of engagement to inform, consult, and involve.

However, according to the studies included in our research, Eritrea and Somalia struggle to reach the collaboration level, and only Uganda and Kenya have started to progress towards the advanced levels of delegate and empower. (Supplementary file 1,Table 1)

Discussion

Our scoping study highlights the critical role of community participation in primary health care (PHC) and health programs (HP) across the IGAD region. Two primary strategies for community participation have emerged.

The first, instrumental participation, involves engaging communities to achieve specific predefined objectives, such as collecting feedback to improve service delivery.

The second, transformative participation, focuses on empowering communities to actively influence decisions, prioritize their needs, and take ownership of health initiatives.

These strategies emphasize the need for community participation to go beyond mere consultation and involve meaningful engagement and representation(9).

The successes of community participation in PHC and HP are evident in various domains.

Notable achievements include the strengthening of local health systems, reductions in health disparities, improvements in education on sexual and reproductive health, and early detection of diseases.

Community participation has also enhanced resilience to health crises, improved nutrition and hygiene practices, empowered women, increased access to healthcare, and contributed to the prevention and management of both communicable and non-communicable diseases (37, 38).

These outcomes underscore the potential of community participation as a critical mechanism for achieving sustainable development and healthier communities.

Despite these successes, significant challenges hinder the sustainability and scalability of community participation initiatives.

One major challenge is poor communication and coordination among stakeholders, which undermines the effectiveness of community mobilization efforts.

Limited financial and material resources also constrain the capacity of communities to engage meaningfully.

Another critical issue is the lack of trust that communities often have in health institutions and community health workers.

This distrust is exacerbated by opaque selection processes for community representatives and unclear messaging about health initiatives.

Cultural beliefs and traditional practices sometimes conflict with public health interventions, necessitating a tailored and culturally sensitive approach by health authorities and community health workers.

Political instability and insecurity in certain regions further complicate the implementation of health programs.

Moreover, inadequate and nondiversified training of community health workers limits the effectiveness of interventions.

Finally, the unequal participation of marginalized groups leads to gaps in health program coverage, perpetuating existing disparities.

Addressing these challenges is essential to ensuring the long-term success of community participation initiatives In the East African countries region.

While the successes described in this study can often be attributed to community participation, it is important to recognize the influence of external factors.

Funding from international donors, policy reforms, and broader socio-economic and environmental dynamics have likely played significant roles. The causal relationship between community participation and its reported outcomes requires further investigation through rigorous evaluations to better isolate its specific contributions ( 35 , 36 ).

In the IGAD region, disparities in community participation practices are apparent.

Kenya, Uganda, and Ethiopia stand out for their extensive peer-reviewed publications and evaluation programs on community participation in PHC and HP.

These countries have more advanced research infrastructures, greater research funding, and stronger integration into global networks.

They also exhibit higher levels of community empowerment, including partial delegation of decisionmaking to communities, as outlined in the IAP2 spectrum.

However, challenges remain in achieving the highest levels of empowerment, such as full leadership and decision-making autonomy for communities.

Other IGAD countries struggle with political instability, armed conflicts, and limited institutional support, which further hinder progress.

Like any scientific review, our study has limitations that must be acknowledged.

The focus on peer-reviewed literature may have excluded valuable insights from gray literature.

Additionally, some studies included in our review did not involve communities in defining outcomes and objectives, potentially introducing biases that do not fully reflect the perspectives and needs of local communities.

Variations in the methodological rigor of the included studies may also affect the reliability of our findings.

Political instability and security issues in some IGAD regions likely influenced the availability of data and the implementation of community participation initiatives, complicating comprehensive assessments.

Despite these limitations, this review provides valuable insights for policymakers and health authorities in the IGAD region.

These findings can inform the design and adaptation of community participation initiatives in PHC and HP.

Future research should aim to conduct more rigorous evaluations to isolate the effects of community participation, include a wider range of information sources such as gray literature, and actively involve communities in the evaluation process.

Such efforts are critical for improving the effectiveness and sustainability of community participation initiatives.

Conclusion

Our review highlighted the crucial role of Community participation the success of health programs and primary health care in the IGAD region.

Although positive outcomes have been observed, numerous challenges still need to be addressed to optimize the effectiveness and sustainability of community participation initiatives.

A thorough understanding of the factors influencing community engagement is essential for developing strategies tailored to local contexts.

The findings of this scoping review provide valuable guidance for health authorities and policymakers in the IGAD region to design more effective initiatives aimed at strengthening community participation in primary health care and health services programs.

References

- Organisation mondiale de la Santé Les soins de santé primaires : rapport de la Conférence internationale sur le soins de santé primaires, Alma-Ata (URSS, 6-12 septembre 1978. Internet. 1978 https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/39243

- Rifkin SB. Lessons from community participation in health programmes : a review of the post Alma-Ata experience. International Health. 2009;1(1):31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.inhe.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Health - United Nations Sustainable Development. United Nations Sustainable Development. 2023. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/

- Rifkin SB. Examining the links between community participation and health outcomes : a review of the literature. Health Policy And Planning. 2014;29(suppl 2):ii98–ii106. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Course UL. Declaration of Astana. 2018 https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIS-SDS-2018.61

- IGAD About IGAD | IGAD Structure | IGAD Regional Strategy. 2022. https://igad.int/about/

- Opata A. One Health Approach : Safeguarding Communities Across Borders in the Horn of Africa. IGAD. 2024. https://igad.int/one-health-approach-safeguarding-communities-across-borders-in-the-horn-of-africa/

- Opata A. Launch of the Health Emergency Preparedness, Response and Resilience Programme for East and Southern Africa. IGAD. 2024. https://igad.int/launch-of-the-health-emergency-preparedness-response-and-resilience-programme-for-east-and-southern-africa/

- Community participation in primary care : what does it mean « in practice » ? PubMed. 2012 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22377547/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston C, Hinton R, Kean S, Baral S, Ahuja A, Costello A, et al. Community participation for transformative action on women's, children's and adolescents' health. Bulletin Of The World Health Organization. 2016;94(5):376–382. doi: 10.2471/blt.15.168492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Core Values, Ethics, Spectrum – The 3 Pillars of Public Participation - International Association for Public Participation Internet. https://www.iap2.org/page/pillars

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies : towards a methodological framework. International Journal Of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O'Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, et al. Scoping reviews : time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal Of Clinical Epidemiology. 2014;67(12):1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) : Checklist and Explanation. Annals Of Internal Medicine. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/m18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karuga R, Dieleman M, Mbindyo P, Ozano K, Wairiuko J, Broerse JEW, et al. Community participation in the health system : analyzing the implementation of community health committee policies in Kenya. Primary Health Care Research Development/Primary Health Care Research And Development. 2023;24 doi: 10.1017/s1463423623000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamalwa MN, Wamalwa MN, Wamalwa MN. Health managers' perspectives of community health committees' participation in the annual health sector planning and budgeting process in a devolved unit in Kenya : a cross-sectional study. The Pan African Medical Journal. 2024;47 doi: 10.11604/pamj.2024.47.124.40351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumo I, Kabaria C, Oduor C, Amondi C, Njeri A, Mberu B. Community advisory committee as a facilitator of health and wellbeing : A qualitative study in informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. Frontiers In Public Health. 2023;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1047133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero JP, Steyn PS, Gichangi P, Kriel Y, Milford C, Munakampe M, et al. Community and Provider Perspectives on Addressing Unmet Need for Contraception : Key Findings from a Formative Phase Research in Kenya, South Africa and Zambia (2015-2016) PubMed. 2019;23(3):106–119. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2019/v23i3.10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31782636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namatovu JF, Ndoboli F, Kuule J, Besigye I. Community involvement in health services at Namayumba and Bobi health centres : A case study. African Journal Of Primary Health Care Family Medicine. 2014;6(1) doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v6i1.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal P, Fisher D, Seruwagi G, Taddese HB. Male involvement in reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health : evaluating gaps between policy and practice in Uganda. Reproductive Health. 2020;17(1) doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-00961-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulumba M, London L, Nantaba J, Ngwena C. Using Health Committees to Promote Community Participation as a Social Determinant of the Right to Health : Lessons from Uganda and South Africa. PubMed Central (PMC) 2018 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6293345/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebreyesus TA, Alemayehu T, Bosma A, Witten KH, Teklehaimanot A. Community participation in malaria control in Tigray region Ethiopia. Acta Tropica. 1996;61(2):145–156. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(95)00107-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datiko DG, Bunte EM, Birrie GB, Kea AZ, Steege R, Taegtmeyer M, et al. Community participation and maternal health service utilization : lessons from the health extension programme in rural southern Ethiopia. Journal Of Global Health Reports. 2019;3 doi: 10.29392/joghr.3.e2019027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adamu AY. Factors Contributing to Participation of a Rural Community in Health Education : A Case Study from Ethiopia. International Quarterly Of Community Health Education. 2012;32(2):159–170. doi: 10.2190/iq.32.2.f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belaid L, Sarmiento I, Dimiti A, Andersson N. Community Participation in Primary Healthcare in the South Sudan Boma Health Initiative : A Document Analysis. International Journal Of Health Policy And Management. 2022 doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2022.6639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiige PCMV, Minh Tram le, Alison Donnelly, Fatmata Fatima Sesay, Joseph Victor Senesie And Laura Enhancing infant and young child feeding in emergency preparedness and response in East Africa : capacity mapping in Kenya, Somalia and South Sudan. ENN. 2018 https://www.ennonline.net/fex/56/iycfemergencyeastafrica

- Saito K, Komasawa M, Ssekitoleko R, Aung MN. Enhancing community health system resilience : lessons learnt during the COVID-19 pandemic in Uganda through the qualitative inquiry of the COVID Task Force. Frontiers In Public Health. 2023;11 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1214307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umer A, Abdella K, Tekle Y, Debebe A, Manyazewal T, Yuya M, et al. Community Engagement in the Fight Against COVID-19 : Knowledge, Attitude, and Prevention Practices Among Dire Dawa Residents, Eastern Ethiopia. Frontiers In Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.753867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhakim M, Tourab SB, Salem F, Van de Weerdt R. Epidemiology of the first and second waves of COVID-19 pandemic in Djibouti and the vaccination strategy developed for the response. BMJ Global Health. 2022;7(Suppl 3):e008157. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-008157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andegiorgish AK, Goitom S, Mesfun K, Hagos M, Tesfaldet M, Habte E, et al. Community knowledge and practice of malaria prevention in Ghindae, Eritrea, a Cross-sectional study. African Health Sciences. 2023;23(1):241–254. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v23i1.26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10398460/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating J, Locatelli A, Gebremichael A, Ghebremeskel T, Mufunda J, Mihreteab S, et al. Evaluating indoor residual spray for reducing malaria infection prevalence in Eritrea : Results from a community randomized control trial. Acta Tropica. 2011;119(2-3):107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCormack CP. Community Participation in Primary Health Care. Tropical Doctor. 1983;13(2):51–54. doi: 10.1177/004947558301300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Weger E, Van Vooren N, Luijkx KG, Baan CA, Drewes HW. Achieving successful community engagement : a rapid realist review. BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3090-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bath J, Wakerman J. Impact of community participation in primary health care : what is the evidence ? Australian Journal Of Primary Health. 2015;21(1):2. doi: 10.1071/py12164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethiopia's Health Extension Program Improving Health through Community Involvement. MEDICC Review. 2011;13(3):46. doi: 10.37757/mr2011v13.n3.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polidano K, Parton L, Agampodi SB, Agampodi TC, Haileselassie BH, Lalani JMG, et al. Community Engagement in Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Research in Brazil, Ethiopia, and Sri Lanka : A Decolonial Approach for Global Health. Frontiers In Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.823844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byass P. The potential of community engagement to improve mother and child health in Ethiopia — what works and how should it be measured ? BMC Pregnancy And Childbirth. 2018;18(S1) doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1974-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayston R, Alem A, Habtamu A, Shibre T, Fekadu A, Hanlon C. Participatory planning of a primary care service for people with severe mental disorders in rural Ethiopia. Health Policy And Planning. 2015;31(3):367–376. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czv072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebregizabher FA, Medhanyie AA, Bezabih AM, Persson LÅ, Abegaz DB. Is Women's Engagement in Women's Development Groups Associated with Enhanced Utilization of Maternal and Neonatal Health Services ? A Cross-Sectional Study in Ethiopia. International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health. 2023;20(2):1351. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20021351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Bahar OS, Ssewamala FM. Implementation science in global health settings : Collaborating with governmental community partners in Uganda. Psychiatry Research. 2020;283:112585. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barugahare J, Kass NE. Managing community engagement in research in Uganda : insights from practices in HIV/AIDS research. BMC Medical Ethics. 2022;23(1) doi: 10.1186/s12910-022-00797-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochola EA, Karanja DMS, Elliott SJ. Local tips, global impact : community-driven measures as avenues of promoting inclusion in the control of neglected tropical diseases : a case study in Kenya. Infectious Diseases Of Poverty. 2022;11(1) doi: 10.1186/s40249-022-01011-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naanyu V, Njuguna B, Koros H, Andesia J, Kamano J, Mercer T, et al. Community engagement to inform development of strategies to improve referral for hypertension : perspectives of patients, providers and local community members in western Kenya. BMC Health Services Research. 2023;23(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09847-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamuya DM, Marsh V, Kombe FK, Geissler PW, Molyneux SC. Engaging Communities to Strengthen Research Ethics in Low-Income Settings : Selection and Perceptions of Members of a Network of Representatives in Coastal Kenya. Developing World Bioethics. 2013;13(1):10–20. doi: 10.1111/dewb.12014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A, High C, Mwangome N, Hanlin R, Jones C. Evaluating and Engaging : Using Participatory Video With Kenyan Secondary School Students to Explore Engagement With Health Research. Frontiers In Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.797290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamalwa MN, Wamalwa MN, Wamalwa MN. Health managers' perspectives of community health committees' participation in the annual health sector planning and budgeting process in a devolved unit in Kenya : a cross-sectional study. The Pan African Medical Journal. 2024;47 doi: 10.11604/pamj.2024.47.124.40351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demissie SD, Kozuki N, Olorunsaiye CZ, Gebrekirstos P, Mohammed S, Kiapi L, et al. Community engagement strategy for increased uptake of routine immunization and select perinatal services in north-west Ethiopia : A descriptive analysis. PloS One. 2020;15(10):e0237319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asegedew B, Tessema F, Perry HB, Bisrat F. The CORE Group Polio Project's Community Volunteers and Polio Eradication in Ethiopia : Self-Reports of Their Activities, Knowledge, and Contributions. The American Journal Of Tropical Medicine And Hygiene. 2019;101(4_Suppl):45–51. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhwezi WW, Palchik EA, Kiwanuka DH, Mpanga F, Mukundane M, Nanungi A, et al. Community participation to improve health services for children : a methodology for a community dialogue intervention in Uganda. African Health Sciences. 2019;19(1):1574. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v19i1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S, Leitão J, Muhangi D, Nuwa A, Magul D, Counihan H. Community dialogues for child health : results from a qualitative process evaluation in three countries. Journal Of Health, Population And Nutrition [Internet] 2017;36(1) doi: 10.1186/s41043-017-0106-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mburu G, Iorpenda K, Muwanga F. Expanding the role of community mobilization to accelerate progress towards ending vertical transmission of HIV in Uganda : the Networks model. Journal Of The International AIDS Society [Internet] 2012;15(S2) doi: 10.7448/ias.15.4.17386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kananura RM, Ekirapa-Kiracho E, Paina L, Bumba A, Mulekwa G, Nakiganda-Busiku D. Participatory monitoring and evaluation approaches that influence decision-making : lessons from a maternal and newborn study in Eastern Uganda. Health Research Policy And Systems [Internet] 2017;15(S2) doi: 10.1186/s12961-017-0274-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman C, Opwora A, Kabare M, Molyneux S. Health facility committees and facility management - exploring the nature and depth of their roles in Coast Province, Kenya. BMC Health Services Research [Internet] 2011;11(1) doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivelyova A, Kakietek J, Connolly H, Bonnel R, Manteuffel B, Rodriguez-García R. Funding and expenditure of a sample of community-based organizations in Kenya, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe. AIDS Care [Internet] 2013;25(sup1):S20–S29. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.764390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeri I, Eyul P, Getahun M, Hatchett K, Owino L, Akatukwasa C. Nothing about us without us : Community-based participatory research to improve HIV care for mobile patients in Kenya and Uganda. Social Science Medicine [Internet] 2023;318:115471. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waiswa P, Mpanga F, Bagenda D, Kananura RM, O’Connell T, Henriksson DK. Child health and the implementation of Community and District-management Empowerment for Scale-up (CODES) in Uganda : a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Global Health [Internet] 2021;6(6):e006084. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angwenyi V, Kamuya D, Mwachiro D, Kalama B, Marsh V, Njuguna P. Complex realities : community engagement for a paediatric randomized controlled malaria vaccine trial in Kilifi, Kenya. Trials [Internet] 2014;15(1) doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macharia JW, Ng’ang’a ZW, Njenga SM. Factors influencing community participation in control and related operational research for urogenital schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths in rural villages of Kwale County, coastal Kenya. The Pan African Medical Journal [Internet] 2016;24 doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.24.136.7878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megerso A, Deyessa N, Jarso G, Tezera R, Worku A. Exploring community tuberculosis program in the pastoralist setting of Ethiopia : a qualitative study of community health workers’ perspectives in Borena Zone, Oromia Region. BMC Health Services Research [Internet] 2021;21(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06683-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakibinge S, Maher D, Katende J, Kamali A, Grosskurth H, Seeley J. Community engagement in health research : two decades of experience from a research project on HIV in rural Uganda. TM IH Tropical Medicine And International Health/TM IH Tropical Medicine International Health [Internet] 2009;14(2):190–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nankya H, Wamala E, Alibu VP, Barugahare J. Community engagement in genetics and genomics research : a qualitative study of the perspectives of genetics and genomics researchers in Uganda. BMC Medical Ethics [Internet] 2024;25(1) doi: 10.1186/s12910-023-00995-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihreteab S, Lubinda J, Zhao B, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Karamehic-Muratovic A, Goitom A. Retrospective data analyses of social and environmental determinants of malaria control for elimination prospects in Eritrea. Parasites Vectors [Internet] 2020;13(1) doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-3974-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan-Abdallah A, Merito A, Hassan S, Aboubaker D, Djama M, Asfaw Z. Medicinal plants and their uses by the people in the Region of Randa, Djibouti. Journal Of Ethnopharmacology [Internet] 2013;148(2):701–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joja LL, Okoli UA. Trapping the Vector : Community Action to Curb Sleeping Sickness in Southern Sudan. American Journal Of Public Health [Internet] 2001;91(10):1583–1585. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.10.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erismann S, Gürler S, Wieland V, Prytherch H, Künzli N, Utzinger J. Addressing fragility through community-based health programmes : insights from two qualitative case study evaluations in South Sudan and Haiti. Health Research Policy And Systems [Internet] 2019;17(1) doi: 10.1186/s12961-019-0420-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed MMG, Shwaib HM, Fahim MM, Ahmed EA, Omer MK, Monier IA. Ebola hemorrhagic fever under scope, view of knowledge, attitude and practice from rural Sudan in 2015. Journal Of Infection And Public Health [Internet] 2017;10(3):287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AC, Evans WD, Barrett N, Badri H, Abdalla T, Donahue C. Qualitative evaluation of the Saleema campaign to eliminate female genital mutilation and cutting in Sudan. Reproductive Health [Internet] 2018;15(1) doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0470-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idriss AA, Lolik P, Khan RA, Benyoussef A. Sudan : national health programme and primary health care 1977/78-1983/84 [Internet] PubMed Central (PMC) 1976 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2366514/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wereta T, Betemariam W, Karim AM, Zemichael NF, Dagnew S, Wanboru A. Effects of a participatory community quality improvement strategy on improving household and provider health care behaviors and practices : a propensity score analysis. BMC Pregnancy And Childbirth [Internet] 2018;18(S1) doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1977-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara WP, Tsofa B, Molyneux S, Goodman C, McKenzie FE. Community and facility-level engagement in planning and budgeting for the government health sector – A district perspective from Kenya. Health Policy [Internet] 2011;99(3):234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emergency Nutrition Network (ENN) Severe acute malnutrition bottleneck analysis tool [Internet] ENN. https://www.ennonline.net/fex/54/bottleneckanalysistool

- Majeed JNPG Ciara Hogan, Madina Ali Abdirahman, Dorothy Nabiwemba, Abdiwali Mohamed Mohamud, Abdirizak Osman Hussien, Kheyriya Mohamed Mohamud, Samson Desie, Grainne Moloney, Ezatullah. Implementation of the Expanded Admission Criteria (EAC) for acute malnutrition in Somalia : interim lessons learned [Internet] ENN. 2019. https://www.ennonline.net/fex/60/expandedadmissioncriteria

- Tiruneh GT, Zemichael NF, Betemariam WA, Karim AM. Effectiveness of participatory community solutions strategy on improving household and provider health care behaviors and practices : A mixed-method evaluation. PloS One [Internet] 2020;15(2):e0228137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young H, Maxwell D. Participation, political economy and protection : food aid governance in Darfur, Sudan. Disasters [Internet] 2013;37(4):555–578. doi: 10.1111/disa.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A/Rahman SH, Mohamedani AA, Mirgani EM, Ibrahim AM. Gender aspects and women’s participation in the control and management of malaria in central Sudan. Social Science & Medicine [Internet] 1996;42(10):1433–1446. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogwang S, Najjemba R, Tumwesigye NM, Orach CG. Community involvement in obstetric emergency management in rural areas : a case of Rukungiri district, Western Uganda. BMC Pregnancy And Childbirth [Internet] 2012;12(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katabarwa MN, Habomugisha P, Eyamba A, Byamukama E, Nwane P, Arinaitwe A. Community-directed interventions are practical and effective in low-resource communities : experience of ivermectin treatment for onchocerciasis control in Cameroon and Uganda, 2004–2010. International Health [Internet] 2015;8(2):116–123. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihv038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rab F, Razavi D, Kone M, Sohani S, Assefa M, Tiwana MH. Implementing community-based health program in conflict settings : documenting experiences from the Central African Republic and South Sudan. BMC Health Services Research [Internet] 2023;23(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09733-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asegedew B, Tessema F, Perry HB, Bisrat F. The CORE Group Polio Project’s Community Volunteers and Polio Eradication in Ethiopia : Self-Reports of Their Activities, Knowledge, and Contributions. The American Journal Of Tropical Medicine And Hygiene [Internet] 2019;101(4_Suppl):45–51. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Building relationships of trust. Engaging with communities through quality, integrated, people-centred and resilient health services. WHO. 2017. https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/quality-health-services/community-engagement

- Community engagement. WHO. 2023. https://www.who.int/westernpacific/initiatives/community-engagement

- Kirigia JM, Zere E, Akazili J. National health financing policy in Eritrea : a survey of preliminary considerations. BMC International Health And Human Rights [Internet] 2012;12(1) doi: 10.1186/1472-698x-12-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]