SUMMARY

Microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) tumors are malignant tumors that, despite harboring a high mutational burden, often have intact TP53. One of the most frequent mutations in MSI-H tumors is a frameshift mutation in RPL22, a ribosomal protein. Here, we identified RPL22 as a modulator of MDM4 splicing through an alternative splicing switch in exon 6. RPL22 loss increases MDM4 exon 6 inclusion and cell proliferation and augments resistance to the MDM inhibitor Nutlin-3a. RPL22 represses the expression of its paralog, RPL22L1, by mediating the splicing of a cryptic exon corresponding to a truncated transcript. Therefore, damaging mutations in RPL22 drive oncogenic MDM4 induction and reveal a common splicing circuit in MSI-H tumors that may inform therapeutic targeting of the MDM4-p53 axis and oncogenic RPL22L1 induction.

In brief

Weinstein et al. show that loss of ribosomal gene RPL22 promotes alternative splicing of its paralog, RPL22L1, and inclusion of MDM4 exon 6, leading to increased MDM4 expression. These findings reveal a common splicing circuit in MSI-H tumors, adding RPL22 to the regulators of the MDM4-p53 axis and oncogenic RPL22L1 induction.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) tumors are a broad group of cancers that contain 30% or more mutations in microsatellites and are driven by somatic or germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair machinery.1,2 MSI-H status is prevalent in endometrial (28.3%), stomach (21.9%), and colon (16.6%) cancers.3 Despite a high tumor mutational burden, MSI-H tumors infrequently harbor mutations in TP53, suggesting that MSI-H tumors might utilize alternative mechanisms to inactivate p53.4 Notably, MSI-H tumors have a recurrent frameshift mutation (p.K15fs) in a microsatellite of the ribosomal protein RPL22 that leads to a premature stop codon and a truncated non-functional protein.5–7 RPL22 and its paralog, RPL22L1, form part of the large subunit of the 60S ribosome and can modulate protein synthesis as well as splicing of genes and transcription factors that affect development8,9 and tumorigenesis.10–13 RPL22 and RPL22L1 expression levels are tightly linked, with lower levels of one paralog resulting in higher expression of the other.8,14 Of note, high RPL22L1 expression is specifically associated with increased MDM4 exon 6 inclusion and MDM4 dependency in Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) data.5 MDM4 protein expression is mediated through alternative mRNA splicing of its sixth exon, which leads to two major isoforms, the exon 6-inclusive MDM4-FL (full-length) and the exon 6-exclusive MDM4-S (short), which is unstable and prone to degradation through nonsense-mediated decay (NMD).15–17 The regulators of this splicing switch that controls MDM4 activity have included serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 3 (SRSF3), ZMAT3, and PRMT5, among others.15,17,18 However, to date, no mutational events in cancer have been associated with this alternative splicing event.

RESULTS

Deleterious RPL22 alterations are common in MSI-H cancers and associated with specific splicing events of MDM4 and RPL22L1

We first considered the prevalence of RPL22 p.K15fs mutations in MSI-H tumors. We found that 68% of MSI-H cell lines in the CCLE, as previously reported,5 and 52% of MSI-H tumors in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) harbor this specific mutation (Data S1). The RPL22 p.K15fs mutation is also highly recurrent in MSI-H cell lines and tumors, including colon (77%), endometrial (72%), gastric (67%), and ovarian (67%) cancer cell lines in the CCLE, and colon adenocarcinoma (48%), stomach adenocarcinoma (80%), and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (59%) in TCGA (Figure 1A). Additionally, heterozygous RPL22 copy-number loss was common across many other tumor types, including kidney chromophobe (79%), pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (62%), adrenocortical carcinoma (39%), and liver hepatocellular carcinoma (42%) (Figure 1B). We found that RPL22 frameshift mutations were mutually exclusive with deleterious TP53 alterations in TCGA and damaging mutations in RPL22 correlated with decreased RPL22 protein expression in the CCLE (Figures S1A, S1B, and S2A).

Figure 1. RPL22 genomic alterations are common in cancer and associated with changes to specific transcripts of MDM4 and RPL22L1 mRNA.

(A) Frequencies of RPL22 p.K15fs frameshift mutation in microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) cell lines in the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) and MSI-H tumors in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; UCEC, uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma).

(B) Proportion of RPL22 copy-number loss and truncating mutations across TCGA tissue types. ΔCN, copy-number loss, single (—1) or biallelic (—2).

(C) Association between decreased inclusion of MDM4 exon 6 and deleterious alterations to RPL22 in TCGA samples.

(D) Association between decreased inclusion of RPL22L1 exon 3A and deleterious alterations to RPL22 in TCGA samples.

(E) Schematic of splicing switches responsible for the major MDM4 (top) and RPL22L1 (bottom) isoforms.

(F) Association between RPL22L1 dependency and deleterious alterations to RPL22 in CCLE samples.

(G) Focus formation assay of MSI-H RPL22 mutant cell lines with short hairpin RNA knockdown of RPL22L1. p values: SW48 RPL22L1KD1 = 0.0008, SW48 RPL22L1KD2 = 0.0025, LNCaP RPL22L1KD1 = 0.0400, and LNCaP RPL22L1KD2 = 0.0155. Error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three replicates. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

As RPL22 is recurrently mutated in MSI-H tumors, we tested for specific splicing events and gene expression changes related to RPL22 loss. RPL22 copy-number loss and RPL22 frameshift mutations were strongly correlated with MDM4 exon 6 inclusion in TCGA samples (Figure 1C). Deleterious alterations in RPL22 were also associated with an alternative 3’ splicing event in RPL22L1 adjacent to exon 3 (Figure 1D). This splicing event generates a transcript with a predicted premature stop codon in exon 3 leading to a 63 amino acid protein compared to the full-length RPL22L1 isoform (122 amino acids). The exon affected by this alternative 3’ splicing event is defined here as exon 3A (Figure 1E). Taken together, these results suggest that RPL22 loss is associated with MDM4 exon 6 inclusion and regulates its paralog RPL22L1 protein expression through exon 3A alternative splicing.

RPL22 and RPL22L1 exhibit paralog synthetic lethality

As paralogs, RPL22 and RPL22L1 share 73% amino acid identity.14 RPL22L1 has previously been identified as a paralog synthetic lethality in the context of RPL22 mutation.5,19 In the context of MSI-H tumors, RPL22L1 is the second-highest scoring synthetic lethality after WRN, likely due to the highly recurrent RPL22 frameshift mutations in MSI-H tumors.20 To confirm the RPL22/RPL22L1 synthetic lethality relationship, synthetic lethality was tested in the updated CRISPR-Avana dataset using 808 cancer cell lines. RPL22L1 dependency was highly correlated with RPL22 mutational status (Figure 1F). Knockdown of RPL22L1 using two independent short hairpin RNAs in two RPL22 mutant MSI-H cell lines (SW48, LNCaP) (Figure 1G; Table S1) and in an RPL22-null microsatellite-stable (MSS) cell line (ZR-75–1) (Figure S2B) validated the synthetic lethality. This synthetic lethality was not dependent on intact p53, as isogenic TP53 wild-type and TP53-null colorectal carcinoma RKO cells (RPCR, RICR) harboring RPL22fs mutations were both sensitive to RPL22L1 knockdown (Figure S2C). Furthermore, overexpression of RPL22 using antibiotic-selected cell pools was sufficient to rescue the synthetic lethality (Figure S2D).

Modulation of RPL22 regulates a limited gene set, including RPL22L1

We next tested whether RPL22L1 regulates expression of RPL22. Overexpression of RPL22L1 using antibiotic-selected cell pools in an MSS cell line (PC3) led to a robust increase in cell proliferation (Figure S3A). RPL22L1 overexpression in another MSS cell line (CAL851) led to a 1.9-fold decrease in RPL22 mRNA expression (Figure S3B), but knockdown of RPL22L1 did not increase RPL22 mRNA expression (Figure S3B). However, overexpression of RPL22 in an MSI-H cell line (LNCaP) led to a significant 3.8-fold decrease in RPL22L1 mRNA expression, while CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of RPL22 in two MSS cell lines (ZR-75–1, NCI-H2110) resulted in a significant ~10-fold increase in RPL22L1 mRNA expression (Figure 2A). These results suggest that RPL22 regulates RPL22L1 mRNA expression, while modulation of RPL22L1 does not strongly affect RPL22 mRNA expression.

Figure 2. MDM4 and RPL22L1 are splicing targets of RPL22.

(A) Total RPL22L1 mRNA expression across experiments. Bars represent the mean of three replicates (**p < 0.01).

(B) Common differentially expressed genes across RPL22 knockout experiments. The columns and numbers indicate the total counts of differentially expressed genes in each combination of intersections between the different experiments.

(C) Inclusion proportions of RPL22L1 exon 3A across experiments. RPL22 knockdown reduces RPL22L1 exon 3A inclusion. Bars represent the mean of three replicates (**p < 0.01). PSI, percent spliced in.

(D) Changes in splicing modes across experiments as indicated by significant differentially spliced variants. The numbers in parentheses indicate the total counts of differential splicing events in each experiment. A3SS, alternative 3’ splicing site; A5SS, alternative 5’ splicing site; MXE, mutually exclusive exons; RI, retained intron; SE, skipped exon.

(E) Common splicing changes across RPL22 knockout experiments. The columns and numbers indicate the total counts of differentially expressed exons in each combination of intersections between the different experiments.

(F) Inclusion levels of MDM4 exon 6 across experiments. Bars represent the mean of three replicates (**p < 0.01).

As modulation of RPL22 regulates RPL22L1 mRNA expression, we performed intersection analyses across RPL22 and RPL22L1 modulation experiments in MSI-H and MSS cell lines to identify genes affected by RPL22 or RPL22L1 perturbation (Table S1). Across all RPL22 overexpression and knockout experiments, four common differentially expressed transcripts were identified—RPL22, two protein-coding transcripts of RPL22L1, and UBAP2L (Figure 2B)—indicating that the modulation of RPL22 leads to a highly specific change in expression of its paralog, RPL22L1. UBAP2L (ubiquitin-associated protein 2-like) is an RNA-binding protein that promotes translation and was not further investigated here.21 Perturbation of RPL22L1 resulted in changes in over 400 common genes across experiments that did not include RPL22 (Figures S3C and S3D).

An intersection analysis between genes that exhibited differential expression and those with differentially spliced exons within each experiment revealed large, shared gene sets in the RPL22L1 modulation experiments. Over half of the differentially spliced genes were also differentially expressed following RPL22L1 overexpression (Figure S3E). However, smaller intersections were present among the RPL22 experiments, with far greater numbers of differentially spliced genes, compared to those that were differentially expressed, associated with RPL22 knockout (Figure S3E). Gene set analysis indicated that loss of RPL22L1 led to the upregulation of hallmark p53 genes, whereas overexpression of RPL22L1 led to the downregulation of other pathways, such as chromosome condensation and segregation (Figure S3F). Overall, these results suggest that RPL22L1 modulation affects the expression and splicing of many genes involved in cell proliferation, whereas RPL22 directly regulates the expression of a more limited gene set that includes RPL22L1.

RPL22 controls RPL22L1 expression via a cryptic alternative 3’ splice site and MDM4 expression through splicing of MDM4 exon 6

Based on our identification of a cryptic alternative 3’ splicing event (Figure S3G) resulting in exon 3A inclusion that is highly correlated with RPL22 loss, we tested whether RPL22 modulates RPL22L1 mRNA expression by regulating the splicing of RPL22L1 pre-mRNA. Expression of RPL22 in MSI-H RPL22-deficient (LNCaP) cells significantly increased RPL22L1 exon 3A inclusion (Figure 2C). Conversely, knockout of RPL22 in MSS RPL22 wild-type (NCI-H2110 and ZR75–1) cells robustly decreased RPL22L1 exon 3A inclusion (Figure 2C).

Differentially expressed splicing events in the context of RPL22 or RPL22L1 modulation further defined the splicing events that occur in the setting of RPL22 loss. Across all modulation experiments, the most common splicing events were skipped exons with similar numbers of inclusion and exclusion events (Figure 2D). In addition, overexpression of RPL22L1 in MSS RPL22 intact cells (CAL851) coincided with altered splicing in large numbers of mutually exclusive exons (Figure 2D). Overexpression or knockout of RPL22 led to specific differentially spliced exon events of MDM4 exon 6, MDM4 exon 6B, RPL22L1 exon 3A, and UBAP2L exon 27, suggesting that RPL22 specifically regulates these events (Figure 2E). Between the RPL22L1 modulation experiments, 14 genes (SMPD4, FN1, EEF1D, DERL2, RPS24, ATXN2, H2AFY, FN1, ASPH, MYO5A, USMG5, RPS24, SCRIB, DERL2) were shared (Figure S3D). Modulation of RPL22 had no significant impact on MDM4 or MDM2 mRNA levels (Figures S3H and S3I), suggesting a primary role in modulating splicing. Overall, we conclude that RPL22 modulation leads to precise changes in the pre-mRNA splicing of MDM4 exon 6, RPL22L1 exon 3A, and UBAP2L exon 27.

RPL22L1 was not necessary or sufficient to promote MDM4 exon 6 inclusion (Figure 2F). However, overexpression of RPL22 led to a marked decrease in MDM4 exon 6 inclusion, and RPL22 knockout robustly increased MDM4 exon 6 inclusion across multiple cell lines (Figure 2F). Together, these data suggest that RPL22 tightly regulates the alternative splicing and expression of both RPL22L1 and MDM4.

RPL22 functions as a tumor suppressor through regulation of MDM4

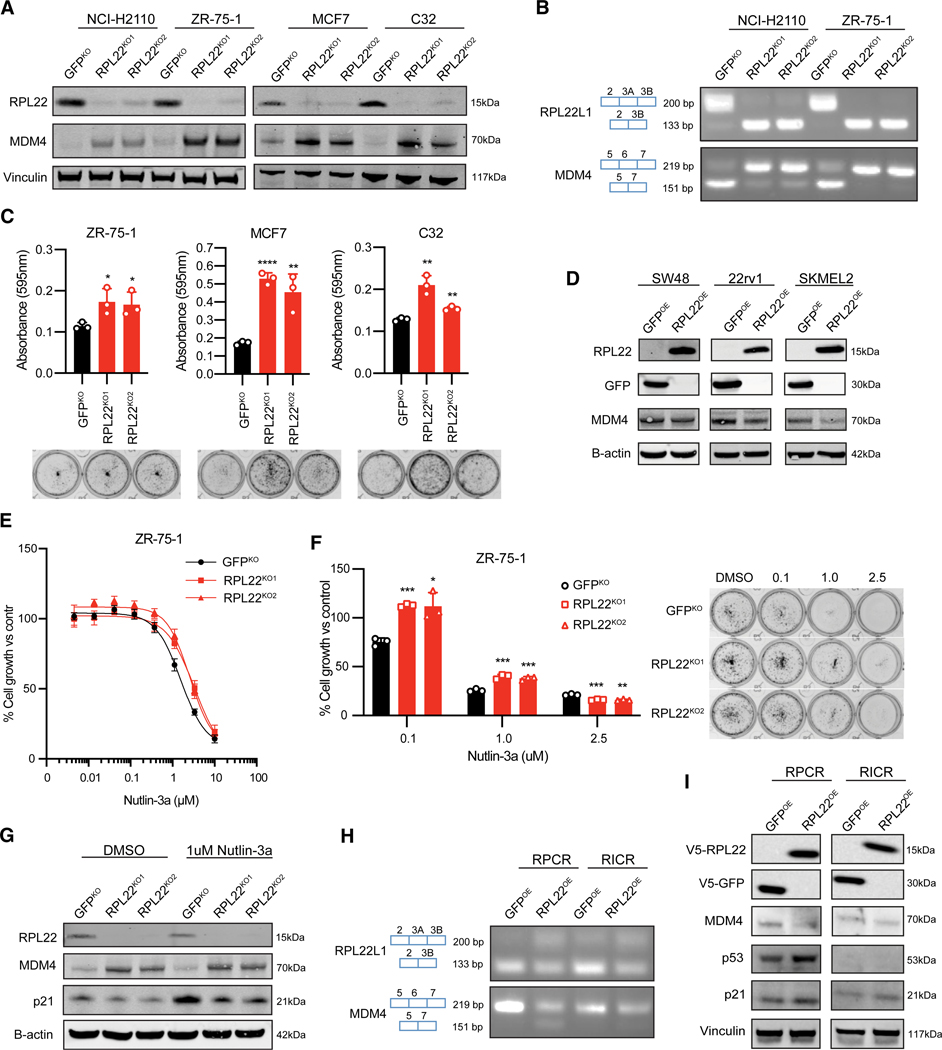

Based on our RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis showing an increase in MDM4 exon 6 inclusion and RPL22L1 exon 3A exclusion in the context of RPL22 loss, we hypothesized that MDM4 and RPL22L1 protein levels increase when RPL22 is lost. In CCLE data, the MDM4 protein was most strongly correlated with both MDM4 mRNA and MDM4 exon 6 inclusion (Figure S4A), suggesting that MDM4 protein expression occurs in the context of MDM4-FL transcripts, as previous studies have shown.15 To test the loss of RPL22, we performed CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of RPL22 in four RPL22 wild-type MSS cell lines (ZR-75–1, NCI-H2110, C32, MCF7) and observed a marked decrease in RPL22 protein expression and a robust increase in MDM4 protein expression (Figure 3A). The two specific splicing events of MDM4 exon 6 inclusion and the alternative 3’ splicing event in RPL22L1 identified through RNA-seq were validated using reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis following CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of RPL22 (Figure 3B). Furthermore, colony formation assays showed a significant increase in cell proliferation in the context of RPL22 loss compared to control in p53 wild-type cells (ZR-75–1, MCF7, C32) (Figure 3C) but not in p53 mutant cells (NCI-H2110) (Figure S4B). Overexpression of RPL22 in MSI-H RPL22 mutant cell lines (SW48, 22rv1, SKMEL2, LNCaP) led to a mild decrease in MDM4 protein levels (Figures 3D and S4C). The two specific splicing events of MDM4 exon 6 exclusion and RPL22L1 exon 3A inclusion in the setting of RPL22 overexpression were also confirmed with RT-PCR in MSI-H RPL22 mutant cells (SKMEL2) (Figure S4D). Finally, we compared the native protein levels of MDM4, MDM2, p53, and p21 in MSI-H and MSS cell lines and observed detectable levels of MDM4 levels in most MSI-H cell lines (Figure S4E).

Figure 3. Loss of RPL22 increases MDM4 expression and augments resistance to Nutlin-3a.

(A) Immunoblot of MSS cell lines with CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of RPL22.

(B) RT-PCR analysis of MSS cell lines with CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of RPL22.

(C) Focus formation assay of MSS cell lines with CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of RPL22. p values: ZR-75–1 RPL22KO1 = 0.0377, ZR-75–1 RPL22KO2 = 0.0464, MCF7 RPL22KO1 < 0.0001, MCF7 RPL22KO2 = 0.0089, C32 RPL22KO1 = 0.0033, and C32 RPL22KO2 = 0.0029. Error bars represent the mean ± SD of three replicates.

(D) Immunoblot of RPL22 mutant MSI-H cell lines with overexpression of RPL22.

(E) Nutlin-3a treatment of MSS cell lines (ZR-75–1) with CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of RPL22. Error bars represent the mean ± SD of six replicates. Half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) were as follows: GFPKO = 1.566 μM, RPL22KO1 = 3.297 μM, and RPL22KO2 = 2.574 μM.

(F) Focus formation assay with Nutlin-3a treatment of MSS cell lines (ZR-75–1) with CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of RPL22. p values: 0.1 μM Nutlin-3a: ZR-75–1 RPL22KO1 = 0.0001 and ZR-75–1 RPL22KO2 = 0.0126; 1.0 μM Nutlin-3a: ZR-75–1 RPL22KO1 = 0.0008 and ZR-75–1 RPL22KO2 = 0.0008; and 2.5 μM Nutlin-3a: ZR-75–1 RPL22KO1 = 0.0010 and ZR-75–1 RPL22KO2 = 0.0015. Error bars represent the mean ± SD of three replicates.

(G) Immunoblot of MSS cell line (ZR-75–1) with CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of RPL22 with immunostaining for p21 after 1 week of 1 μM Nutlin-3a treatment.

(H) RT-PCR analysis of RPL22 mutant MSI-H cell lines with overexpression of RPL22. RPCR cells are TP53 wild type, while RICR cells are TP53 null.

(I) Immunoblot of RPL22 mutant MSI-H cell lines with overexpression of RPL22.

Since MDM4 is a well-known inhibitor of p53, we hypothesized that the increase in cell growth in the context of RPL22 loss was driven primarily by increased MDM4 protein levels. To test whether increased MDM4 levels contributed to increased cell growth in the context of RPL22 loss, cells were treated with Nutlin-3a, an MDM2 inhibitor with some activity against MDM4.22 Nutlin-3a sensitivity is highly correlated with MDM4-FL and is the top drug sensitivity correlated with MDM4 exon 6 inclusion among a large panel of drugs.5,23–25 TP53 wild-type MSS cells with CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of RPL22 showed resistance to Nutlin-3a in short- and long-term growth assays (Figures 3E and 3F). These results suggest that while MDM4-FL levels appear to be a biomarker for Nutlin-3a sensitivity, loss of RPL22 and overexpression of MDM4 promote resistance to Nutlin-3a. No difference in cell growth was observed in p53 mutant cells treated with Nutlin-3a (Figures S4F and S4G). While induction of p53 protein expression was not observed in the context of 1 week of Nutlin-3a treatment and RPL22 knockout (Figures S4H and S4I), protein expression of p21, a downstream target of p53, was downregulated (Figure 3G), consistent with less p53 activity due to increased MDM4. Quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) of downstream targets of p53, including BBC3, p21, and MDM2, showed significant induction following Nutlin-3a treatment with less induction in the context of RPL22 loss, but no significant difference was consistently observed after 24 h or 1 week of treatment (Figure S4J). When we overexpressed RPL22 in MSI-H TP53 wild-type and mutant cells (RPCR, RICR), we observed alternative splicing of both MDM4 and RPL22L1, decreased MDM4 protein expression, and increased induction of p21 protein expression in the setting of TP53 wild-type cells (Figures 3H, 3I, and S4K). These findings are consistent with RPL22-mediated repression of MDM4 and subsequent activation of the p53 axis.

Since RPL22 and RPL22L1 are known to regulate pre-mRNA splicing by binding to the mRNA of their targets8 and experiments suggested that RPL22 was the paralog responsible for modulating the splicing of MDM4, RPL22L1, and UBAP2L, the predicted hairpin structures in MDM4 proximal to exon 6A and in RPL22L1 proximal to exon 3A, where RPL22 might bind, were of particular interest (Figures S5 and S6). We performed crosslinking immunoprecipitation sequencing (CLIP-seq) on TP53 wild-type MSS cells (ZR-75–1) to characterize the genome-wide binding specificity of RPL22 and identified peaks in intron 5 and exon 6 of MDM4, as well as significant peaks in the 3’ UTR of MDM4 and UBAP2L but no such peaks in RPL22L1 (Figure 4A). We hypothesize that the absence of peaks in RPL22L1 may be explained by low levels of RPL22L1 mRNA. We also confirmed binding of RPL22 to MDM2 mRNA, as previous studies have shown (Figure S7).26 Region enrichment analysis uncovered a binding preference for the transcription termination site of MDM4, overall suggesting that RPL22 binds MDM4 at regulatory sites (Figures 4A and 4B). Gene set enrichment analysis of genes containing peaks uncovered strong enrichment (p < 1 3 10—7) for genes involved in histone modification, regulation of transcription, and RNA splicing (Figure 4C). Intersections between peak-containing genes and those exhibiting significant differential splicing across previous RPL22-modulating experiments also revealed sizable overlaps, suggesting a correlation between RPL22 binding and specific splicing events (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Characterization of RPL22 binding preference with CLIP-seq.

(A) Binding of RPL22 to the 3’ UTR and exon 6 of MDM4 as determined by peak calling on CLIP-seq measurements from ZR-75–1 cells. p = 0.05.

(B) Left: peak frequencies relative to the transcription termination site (TTS). Right: breakdown of peak-containing regions.

(C) Gene set enrichment analysis of RPL22-bound peaks.

(D) Overlaps between genes containing RPL22-bound peaks and differentially spliced genes across RPL22 modulation experiments. Total number of genes and hypergeometric test for each cell line: LNCaP: 15,602 genes, p = 1.536 × 10−4; NCI-H2110: 15,226 genes, p = 6.682 × 10−9; and ZR75–1: 15,690 genes, p = 8.901 × 10−6.

(E) Schematic model of loss of RPL22 and recurrent RPL22 frameshift mutations in MSI-H tumors that results in a splicing-mediated switch to the functional isoforms of MDM4 and RPL22L1. The functional isoform of MDM4 inhibits p53 activity and increased levels of RPL22L1 compensate for RPL22 reduction in the ribosome and perform additional extraribosomal functions.

Finally, we tested the localization of RPL22 and MDM4 protein in TP53 wild-type (RPCR) and TP53-null (RICR) cells with RPL22 overexpression (Figures S8A and S8B). Under normal conditions, RPL22 protein was predominantly localized in the cytoplasm, with a minor fraction detected in the nucleus colocalizing with MDM4. Upon RPL22 overexpression, an increased proportion of RPL22 was localized in the nucleus and colocalized with MDM4 (Figure S8). Taken together, our results indicate that RPL22 modulates the expression of MDM4 and RPL22L1 through splicing modulation, ultimately promoting cell proliferation and survival (Figure 4E).

DISCUSSION

Here, we identify the activation of a common splicing switch through the loss of RPL22 and reveal it as a mechanism of MDM4 induction. RPL22 loss increases inclusion of MDM4 exon 6, leading to a functional protein that is known to interact with MDM2, and together, they form a complex with p53 to inactivate and target p53 for degradation. We identify a physical interaction between RPL22 and MDM4 in intron 5, exon 6, and the 3’ UTR, which may indicate additional regulatory mechanisms. Through these interactions, RPL22 may function to maintain the expression of MDM4-S in the balance between MDM4-FL/MDM4-S isoforms, thus providing a mechanism to suppress MDM4-FL expression and an explanation for the lack of MDM4 protein expression in most somatic tissues.27 Additionally, the MDM4 3’ UTR is a known site of microRNA regulation and SNPs that are associated with increased risk for multiple cancers.27 It remains unclear whether RPL22 binds MDM4 in conjunction with other primary splicing regulators, such as ZMAT3, and if RPL22 may serve as a “rheostat” for p53 activity. RPL22 is also thought to mediate cell proliferation through inhibitory RPL22 N-terminal binding to MDM2.26 In patients with MSI-H tumors, such as colon and stomach adenocarcinomas, which harbor RPL22fs mutations in more than 70% of MSI-H cell lines and tumors in the CCLE and TCGA, our study suggests that tumorigenesis may in part be driven by RPL22 mutations or loss leading to MDM4 inhibition of p53. Thus, RPL22 status may be a biomarker for clinical responses to MDM2/MDM4 inhibitors in the setting of intact p53.

We also show that RPL22 loss leads to a splicing switch of its paralog, RPL22L1, thereby highlighting how one ribosomal paralog regulates another. Inclusion of RPL22L1 exon 3A is predicted to encode a non-functional protein lacking the RNA-binding domain as well as an mRNA transcript that is potentially subject to NMD.28 The alternate 3’ splice site in the third exon of RPL22L1 has also recently been described in the induction of glioblastoma cells under alternate regulation by SRSF4.29 Recent data indicate that this differentially spliced RPL22L1 has activity in glioblastoma cells and highlights another mechanism by which this transcript affects splicing.29 Activation of RPL22L1 is also known to drive cell proliferation in ovarian tumors through epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition,12 indicating the importance of RPL22L1 activation in tumor progression. Although RPL22 and RPL22L1 share highly similar sequences and are functionally redundant in the large ribosome for ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis,14 these results suggest a wider range of nuclear effects of RPL22 and RPL22L1 on mRNA expression through splicing. While we were unable to detect direct binding of RPL22 to RPL22L1, our findings, combined with previous evidence of splicing-mediated autoregulation between RPL22 paralogs in yeast28,30–32 and RPL22 repression of its paralog through direct binding in mice,14 suggest that RPL22 directly regulates its own paralog through this alternative 3’ splicing switch.

Given the high prevalence of RPL22 frameshift mutations in MSI-high cancers, our results identify RPL22 as a tumor-suppressor gene that acts as a regulator of the p53 inhibitor MDM4 through modulation of its splicing. Our work suggests that ribosomal genes that also function as mediators of splicing may serve as therapeutic splicing targets.33–37 The identification of RPL22 as a regulator of MDM4 function provides an additional pathway for the development of MDM4-inhibiting treatments and adds the paralogs RPL22/RPL22L1 to other ribosomal proteins that modulate p53 activity in cancer.

Limitations of the study

While this study shows the robust impact of RPL22 loss on cell proliferation through splicing modulation of RPL22L1 and MDM4, conclusions are limited by experimental conditions and findings. In vitro studies were conducted in multiple MSI-H and MSS cell lines, but no studies were performed with direct knockout of mismatch repair genes to specifically generate the MSI-H phenotype. Additionally, while the CLIP-seq data support a binding interaction between MDM4 and RPL22, the exact binding elements needed for RPL22 modulation of splicing remain to be determined. Further investigations are necessary to delineate the precise mechanism of regulation of the downstream targets of RPL22, specifically how RPL22 directly regulates alternative splicing of MDM4. Finally, we did not investigate the significance of UBAP2L, leaving room for subsequent analysis of RPL22 splicing targets.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Dr. Franklin W. Huang (franklin.huang@ucsf.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique plasmids or reagents. All reagents used in this study are available from the lead contact upon request.

Data and code availability

Raw RNA-seq and CLIP-seq data have been deposited at GEO and are publicly available as of the date of publication. The accession numbers is GEO: GSE263237. CCLE and TCGA data used in this study have been deposited at Mendeley and are publicly available as of the date of publication. The DOI is Mendeley Data: http://www.doi.org/10.17632/nh58jyt5dt.1. All other data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

All original code has been deposited at Zenodo and is publicly available as of the date of publication. The DOI is Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10901568.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Cell lines

Cells from various cancer types – breast, lung, prostate, colon, and skin – were cultured as monolayers. Of the included cell lines, SW48, 22rv1, SKMEL2, and LNCaP are known microsatellite unstable (MSI) cell lines, while ZR-75–1, NCI-H2110, C32, MCF7, PC3 cells are microsatellite-stable (Table S1).5,38–42 RICR and RPCR cells were also created in an MSI background.41 ZR-75–1, C32, and MCF7 cells are RPL22 and TP53 wild-type, while NCI-H2110 cells are RPL22 wild-type and contain a TP53 p.R158P missense mutation. LNCaP cells contain a RPL22 p.K15fs frameshift mutation and are wild-type TP53. CAL851 cells are wild-type RPL22 and contain a TP53 p.K132E mutation. SW48, SKMEL2, and 22rv1 cells contain a RPL22 p.K15fs frameshift mutation. PC3 cells are TP53 null. SW48, ZR-75–1, MCF7, CAL851 cells were isolated from females, while 22rv1, SKMEL2, LNCaP, C32, PC3 were isolated from males. The sex of NCI-H2110, RICR, and RPCR is not available. All the cell lines listed above were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). ZR-75–1, NCI-H2110, C32, PC3 and LNCaP cells were cultured in RPMI (Gibco) with 10% FBS. SW48, SW1573, 22rv1, CAL851, and 293T cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco) with 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher). RICR (TP53 mutant), RPCR (TP53 wildtype), and MCF7 cells were cultured in EMEM (Gibco) with 10% FBS. RICR and RPCR were enerated by transiently transfecting the parental TP53 wildtype MSI RKO cells with sgRNAs (in pXPR003) and Cas9 (in pLX311), and then selecting for ~2 weeks in 5 μM Nutlin-3. Thereafter, the cells were maintained in the absence of Nutlin-3 (DMEM +10% FBS + Penn-Strep + Glutamine). The parental and p53-knockout cells were subsequently stably infected with Cas9 again in pLX311 and then with p53-WT or p53-MUT-P278A, making them all resistant to Blasticidin and Hygromycin. All cells were incubated at 37◦C with 5% CO2 and passaged twice a week using Trypsin-EDTA (0.25%) (Thermo Fisher). Cell identity was verified through the ATCC authentication service using short tandem repeat profiling and tested for mycoplasma using the Mycoalert Detection Kit (Lonza, LT07–118).

METHOD DETAILS

CCLE annotations

We sourced mutations and copy number estimates from the DepMap download portal (https://depmap.org/portal/download/) under the public 19Q4 release (CCLE_mutations.csv and CCLE_gene_cn.csv, respectively). We used the mutation classifications detailed in the Variant_annotation column. We also downloaded processed RNAseq estimates in the form of gene expression, transcript expression, and exon inclusion estimates from the DepMap data portal under the latest CCLE release (CCLE_RNAseq_rsem_genes_tpm_20180929.txt.gz, CCLE_RNAseq_rsem_transcripts_tpm_20180929.txt.gz, and CCLE_RNAseq_ExonUsageRatio_20180 929.gct.gz, respectively). We also downloaded RPPA estimates (CCLE_RPPA_20181003.csv) and global chromatin profiling results (CCLE_GlobalChromatinProfiling_20181130.csv). Before performing subsequent analyses, we transformed transcript and gene expression TPMs by taking a log2-transform with a pseudocount of +1. Harmonized CCLE sample information and annotations are available in Data S1.1.

TCGA annotations

Pan-cancer TCGA sequencing data were sourced from the UCSC Xena browser (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/?cohort=TCGA%20Pan-Cancer%20(PANCAN)&removeHub=https%3A%2F%2Fxena.treehouse.gi.ucsc.edu%3A443) as well as the Genomic Data Commons (https://gdc.cancer.gov/about-data/publications/PanCanAtlas-Splicing-2018). TCGA STAD (Stomach Adenocarcinoma) RNA-seq expression and somatic mutation data were sourced from cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=stad_tcga). TCGA UCEC (Uterine Corpus Endometrial Carcinoma) RNA-seq expression and somatic mutation data were sourced from cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=ucec_tcga). TCGA MSI annotations were sourced from Supplementary File 2 of Bonneville et al. 2017.43 Harmonized TCGA sample information and annotations are available in Data S1.2.

Lentivirus transduction

Lentiviruses were produced in 293T cells for all RNAi-induced knockdown, over-expression, and CRISPR-cas9 knockout experiments. To express shRNAs, cells were seeded at 4–5 × 105 cells per well in a 6-well plate and subsequently transduced with lentivirus. The following shRNAs were obtained from the Genetic Perturbation Platform at the Broad Institute: plx-304 lacZ (LacZOE) TCGTATTACAAGTCGTGACT; plx-304 GFP (GFPOE) ccsbBroad304_99986; plx-304 RPL22 (RPL22OE) NM_000983; shluc (LucKD) TRCN0000072243, CTTCGAAATGTCCGTTCGGTT; pLKO RPL22L1 (RPL22L1KD1) TRCN0000247704: GAGGTCAACCTGGAG GTTTAA; pLKO RPL22L1 (RPL22L1KD2) TRCN0000247705: CATTGAACGCTTCAAGAATAA. Puromycin (2 μg/mL) or blasticidin (5ug/ml) were used to select cells following incubation. GFP overexpression was verified through observation on a EVOS FL (Invitrogen) and RPL22L1 knockdown was confirmed via western blot.

RPL22 was targeted using single-guide RNA sequences inserted into the lentiCRISPR v2 plasmid purchased from Addgene and originally a gift from Feng Zhang (Addgene plasmid # 52961; http://n2t.net/addgene:52961; RRID: Addgene_52961).44 Six RPL22 lentiCRISPR v2 constructs were tested and two, RPL22–1A-1 and RPL22–4A-1, were used based on western blot analysis. RPL22–1A-1 (RPL22KO1): CACCGCGCGGAGCCATACTAACCAC; RPL22–4A-1 (RPL22KO2): CACCGCATACTAACCACA GGAGCCA; control guide EGFP_sg6 (GFPKO1): GGTGAACCGCATCGAGCTGA.45 Transduced cells were selected with puromycin (2 μg/mL) and western blot analysis was used to confirm RPL22 knockout.

Cell proliferation assays

Lentiviral transduced cells were plated for growth curve, drug curve and focus formation analysis. For growth and drug curves, cells were seeded at a density of 2–10 × 103 cells in 96-well plates in the appropriate media. Nutlin-3a (Tocris, 3984) drug dilutions were added after 24 h and cells were allowed to grow for a subsequent 96 h or stopped every 24 h depending on the experiment. CellTiter-Glo was added to wells to stop the assay and luminescence recorded according to the manufacturer’s protocol on a SpectraMax (Molecular Devices). For focus formation analyses, cells were seeded in triplicate in 12-well plates at a density of 2–7.5 × 103 in the appropriate media. If applicable, nutlin-3a was added the following day and replaced after seven days. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and stained with 0.5% crystal violet solution after 7–14 days depending on the cell line. For protein analysis and qPCR, cells were seeded in 6-well plates, treated with nutlin-3a after 24 h with media replacement every three days, and collected following seven days of growth. Plates were imaged using a ChemiDoc Touch Gel Imaging System (Biorad) and subsequently de-stained using 10% acetic acid. Absorbance was measured at 595 nm using a SpectraMax (Molecular Devices). Data shown are representative figures of at least three independent experiments, except for Figure 1G which included two independent experiments.

RNA sequencing, reverse transcription PCR, and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using an RNAeasy Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For RNA sequencing at least 10,000 ng total RNA dissolved in ddH2O was extracted and sent to NovoGene. Libraries were prepared externally by NovoGene, sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 PE150 and FASTQ files were provided.

For reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR), 1 μg RNA was reverse transcribed with SuperScriptTM III First-Strand Synthesis System (ThermoFisher). PCRs were run using Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase. For RPL22L1 alternative splicing was visualized with the forward primer binding in exon 2, and the reverse primer binding in exon 3B. For MDM4, alternative splicing was visualized with forward primer binding in exon 5, and the reverse primer binding in exon 7. PCR was performed for 35 cycles (10 s at 98◦C; 20 s at 64◦C; 30 s at 72◦C) using a 100 ng cDNA template. Products were visualized on a 2% agarose gel.

For quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR), 1 mg RNA was reverse transcribed with SuperScriptTM III First-Strand Synthesis System (ThermoFisher). Primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies and sequences for all primers used in this study are included in Table S2. To detect mRNA amplification reactions, qPCR was performed with the SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The ΔΔCt method was used to normalize the mRNA expression levels with TATA-box binding protein (TBP) as the house keeping gene.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors (Roche, 4719956001), separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using the iBlot dry transfer system (Life Technologies). Membranes were cut, blocked with Intercept blocking buffers (LI-COR) and probed for antibodies against RPL22 (1:100, Santa Cruz, sc-136413), RPL22L1 (1:100, 1:5000, MyBioSource, MBS7050452), HdmX/MDMX (1:500, 1:1000, Bethyl, A300–287A-M), MDM2 (1:200, Santa Cruz, sc-965), p53 (1:200, Santa Cruz, sc-126), p53 (1:1000, Cell Signaling, 2524S), p-p53 (1; 100, Santa Cruz, sc-sc-377567), p21 (1:2000, Cell Signaling, 2946S), UBAP2L/NICE-4 (1:1000, Thomas Scientific, A300–534A-T), B-actin (1:1000, Cell Signaling, 4970S), Vinculin (1:500, Sigma, V9131), or V5 (1:4000, Invitrogen, P/N 46705). Secondary antibodies included goat anti-rabbit IRDye 800CW (LI-COR, 925–32211), goat anti-mouse IRDye 800CW (LI-COR, 925–32210), and donkey anti-mouse IRDye 680 (LI-COR, 926–68072). Blots were imaged with an Odyssey Infrared Imager. ImageJ was used to quantify protein expression in indicated figures. All Western blots were repeated with separate biologically independent replicates.

Transcript expression quantification

We used kallisto for transcript expression quantification.46 GRCh37 cDNA sequences for constructing the Kallisto indices were downloaded from the Ensembl FTP archives at ftp://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-75/fasta/homo_sapiens/cdna/Homo_sapiens.GRCh37.75.cdna.all.fa.gz. To construct the Kallisto index, place the cDNA FASTA file as-is into/data/raw/kallisto_homo_sapiens, and execute 1_kallisto_index.sh from the/scripts directory. Next, to quantify transcript expression, run 2_kallisto_quant.sh from/scripts/, which outputs estimates to/data/raw/kallisto_quant/. Kallisto is fast enough to process each paired-end run in about half an hour on most modern machines. We ran Kallisto with arguments –bias -b 100 -t 6. Kallisto outputs raw transcript quantifications and bootstrap samples for use with Sleuth in differential expression analyses.47 To run Sleuth, see/notebooks/p1_kallisto-sleuth.i-pynb. This was used to run differential expression analyses on each of the experiments, as well as annotate transcripts with matching genes and biotypes for downstream analyses. Differentially expressed gene sets used for comparison across different treatments were selected using a Q-value cutoff of 0.01.

Signature gene set development and correlation analysis

Gene signatures were created for the four phenotypes (RPL22 knockout, RPL22L1 knockout, RPL22 overexpression, and RPL22L1 overexpression) in this study. Genes with log2 fold change >1 and FDR q < 0.05 (compared to control samples, Wilcoxon rank-sum test) were included for each signature gene set. The ssGSEA module on GenePattern48 was then used to test the correlation of the gene signatures on the TCGA-STAD and TCGA-UCEC datasets with curated TP53 and RPL22 mutational status. Then the ssGSEA results.gct files were parsed through customized code to generate heatmaps and conduct correlation and statistical analysis.

Splicing quantification

To compute splicing levels and perform differential splicing analyses, we aligned FASTQ files with STAR,49 after which we used rMATS50 for splicing quantification. STAR alignment included the following process: First, we downloaded the Broad hg19 FASTA reference from console.cloud.google.com/storage/browser/_details/broad-references/hg19/v0/Homo_sapiens_assembly19.fasta, and the associated index from console.cloud.google.com/storage/browser/_details/broad-references/hg19/v0/Homo_sapiens_as-sembly19.fasta.fai. We also downloaded the Ensembl GTF file from ftp://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-75/fasta/homo_sapiens/dna/Homo_sapiens.GRCh37.75.dna.primary_assembly.fa.gz. STAR is a memory-heavy program, and building the index and alignments both require about 32–48 GB of RAM. An example script used for index construction on the Broad computing clusters is provided in/scripts/3_STAR_index.sh. Once the index was built, we ran two-pass alignments on the Broad computing clusters using 4_STAR_2pass.sh. Note the use of/scripts/fastq_samples.txt. We used the rMATS Docker image described at http://rnaseq-mats.sourceforge.net/rmatsdockerbeta. To run rMATS, we changed the DATA_PATH variable in/scripts/5_run_rmats.sh to the absolute path of the/data folder and executed the script.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed with 16% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (ProSciTech, C004–100) for 15 min at room temperature. They were then washed three times with 1X PBS for 5 min each at room temperature. Subsequently, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (ABCAM INC, ab286840) for 15 min at room temperature, followed by another three washes with 1X PBS for 5 min each at room temperature. To block unspecific antibody binding, cells were treated with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies against V5 (1: 100), RPL22 (1:100 or 1:25) and MDM4 (1:100 or 1:25) were then applied for 2 h at room temperature. After three washes with 1X PBS for 5 min each at room temperature, fixed cells were incubated with Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 488), Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 647) and 1 μg/mL DAPI (Thermofisher D1306) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, cells were washed three times with 1X PBS for 5 min each at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted with a drop of Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent (Fisher Scientific, P10144) to protect fluorescent dyes or proteins from bleaching and sealed with nail polish to prevent movement. Representative images were acquired using a confocal Leica Sp5 microscope (Leica Microsystems, Germany). To capture images with immersion oil, a total of 20 μL of oil was applied to the slide. The coarse adjustment wheel was used to raise the carrier platform, ensuring the oil immersion objective lens was submerged in the immersion oil. The aperture, exposure time, laser intensity, and fine adjustment wheel were then carefully adjusted to achieve the clearest object image.

CLIP-seq

ZR-75–1 cells were crosslinked with 400 mJ/cm2 254 nm UV. Crosslinked cells were lysed with ice-cold lysis buffer (1X PBS, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% IGEPAL CA-630) supplemented with 1x halt protease inhibitors (Pierce) and SuperaseIN (Invitrogen). After lysis, samples were treated with DNase I (Promega) at 37degC, 1000rpm 5 min. Each lysate sample was then split equally, and each portion treated with either a medium or low dilutions of a mix of RNase A and RNase I (Thermo; 3.3ng/ul RNase A and 1units/ul RNase I, and 0.67 RNase A and 0.2units/ul RNase I, respectively) at 37degC for 5 min. Lysate was immediately cleared by centrifuging at 21,000xg 4degC 20 min. The clarified lysate was added to protein G dynabeads (Invitrogen) that were pre-conjugated to an anti-RPL22 antibody (Santa Cruz sc-136413). Immunoprecipitation was performed at 4degC with end-over-end rotation for 1.5 h. Beads were then washed 2X with ice-cold high salt wash buffer (5X PBS, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% IGEPAL CA-630), 2X with ice-cold lysis buffer (1X PBS, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% IGEPAL CA-630), and 2X with ice-cold PNK buffer (10mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.5% IGEPAL CA-630, 10mM MgCl2). The RNA was then end-repaired, and poly(A) tailed on-bead by treatment with T4 PNK (NEB) and then treatment with yeast poly(A) polymerase (Jena Bioscience). The RNA was 3’-end-labeled with azido-dUTP (TriLink biotechnologies) using yeast poly(A) polymerase (Jena Bioscience). The protein-RNA complexes were then labeled with IRDye800-DBCO (LiCor). The protein-RNA complexes were then eluted from beads in 1XLDS sample buffer (Invitrogen), resolved by running on a 4–12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gel (Invitrogen), transferred to nitrocellulose, and imaged using an Odyssey Fc instrument (LiCor). The regions of interest were excised from the membrane and the RNA was isolated by Proteinase K (Invitrogen) digestion and subsequent pulldown with oligodT dynabeads (Invitrogen). After eluting from the oligodT beads, the RNA was immediately used for library preparation using the SMARTer smRNA-Seq Kit (Takara), with the following modifications. The poly(A) tailing step was omitted, and reverse transcription was performed with a custom RT primer. The PCR step was performed with indexed forward (i5) primers and a universal reverse (i7) primer. The libraries were PAGE purified and then sequenced on an Il-lumina HiSeq4000 instrument at the UCSF Center for Advanced Technologies.

CLIP-seq analysis

The raw CLIP-seq data were parsed via FastQC51 for quality control. Low-quality sequences, artifacts sequences, contaminated sequences and low-quality reads were filtered out via Clip tool kit.52 Low-quality sequences before the adapters and universal adapter sequences were removed by Cutadapt trimmer.53 Reads with sufficient quality were then aligned to the human reference genome (hg38). The aligned sam file for each biological replicate was parsed and converted to.bed file using parseAlignment.pl, selectRow.pl and bed2rgb.pl. Using the combined results.bed files, peak calling was performed using Clip tool kit tag2peak.pl and statistical significance was set as p-value = 0.05. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) was used to visualize the peaks.54 Motif detection was conducted on the called peaks using HOMER.55 Genomic annotations were obtained by extracting the coordinates of the significant peaks using bedtools, followed by gene ontology analysis.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

For all assays, statistical significance was calculated using unpaired student’s t-tests on GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software). Error bars represent the mean ± S.D with significance represented as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, and “n.s” for no significance. The number of independent experiments for each assay is indicated in the figure legends. Quantification and statistical analyses for transcript expression analysis and Clip-seq are described in “Methods’’ under the respective section.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Antibodies | ||

|

| ||

| Anti-RPL22 | Santa Cruz | Cat#: sc-136413; RRID: AB_10658965 |

| Anti-RPL22L1 | MyBioSource | Cat#: MBS7050452 |

| Anti-HdmX/MDMX | Bethyl | Cat#: A300–287A-M; RRID: AB_263407 |

| Anti-MDM2 | Santa Cruz | Cat#: sc-965; RRID: AB_627920 |

| Anti-p53 | Santa Cruz | Cat#: sc-126; RRID: AB_628082 |

| Anti-p53 | Cell Signaling | Cat#: 2524S; RRID: AB_331743 |

| Anti-p-p53 | Santa Cruz | Cat#: sc-377567 |

| Anti-p21 | Cell Signaling | Cat#: 2946S; RRID: AB_2260325 |

| Anti-UBAP2L/NICE-4 | Thomas Scientific | Cat#: A300–534A-T; RRID: AB_2272582 |

| Anti-B-actin | Cell Signaling | Cat#: 4970S; RRID: AB_2223172 |

| Anti-Vinculin | Sigma | Cat#: V9131; RRID: AB_477629 |

| Anti-V5 | Invitrogen | Cat#: P/N 46705 |

| Goat anti-rabbit IRDye 800CW | LI-COR | Cat#: 925–32211; RRID: AB_2651127 |

| Goat anti-mouse IRDye 800CW | LI-COR | Cat#: 925–32210; RRID: AB_2687825 |

| Donkey anti-mouse IRDye 680 | LI-COR | Cat#: 926–68072; RRID: AB_2814912 |

| Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) | ABCAM INC | Cat#: ab150113; RRID: AB_2576208 |

| Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 647) | ABCAM INC | Cat#: ab150079; RRID: AB_2722623 |

|

Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| plx-304 lacZ (LacZOE) | Genetic Perturbation Platform at the Broad Institute |

Clone ID#: ccsbBroad304_99994 |

| plx-304 GFP (GFPOE) | Genetic Perturbation Platform at the Broad Institute | Clone ID#: ccsbBroad304_99986 |

| plx-304 RPL22 (RPL22OE) | Genetic Perturbation Platform at the Broad Institute | Clone ID#: ccsbBroad304_01425; NCMI RefSeq Record:NM_000983 |

| shluc (LucKD) | Genetic Perturbation Platform at the Broad Institute | Clone ID#: TRCN0000072243 |

| pLKO RPL22L1 (RPL22L1KD1) | Genetic Perturbation Platform at the Broad Institute | Clone ID#: TRCN0000247704 |

| pLKO RPL22L1 (RPL22L1KD2) | Genetic Perturbation Platform at the Broad Institute | Clone ID#: TRCN0000247705 |

| Puromycin (2 μg/mL) | Thermo Fisher | Cat#: A1113803 |

| Blastocydin (5ug/ml) | Invitrogen | Cat#: ant-bl-05 |

| Nutlin-3a | Tocris | Cat#: 3984 |

| Halt protease inhibitors | Pierce | Cat#: 78429 |

| SuperaseIN | Invitrogen | Cat#: AM2694 |

| DNase I | Promega | Cat#: Z3585 |

| RNase A | Thermo Fisher | Cat#: R1253 |

| RNase I | Thermo Fisher | Cat#: EN0601 |

| Protein G dynabeads | Invitrogen | Cat#: 10003D |

| T4 Polynucleotide Kinase | NEB | Cat#: M0201S |

| yeast poly(A) polymerase | Jena Bioscience | Cat#: RNT-006-S |

| azido-dUTP | TriLink biotechnologies | Cat#: N-1029 |

| IRDye800-DBCO | LI-COR | Cat#: LI-COR 92950000 |

| 1XLDS sample buffer | Invitrogen | Cat#: NP0008 |

| 4–12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gel | Invitrogen | Cat#: NP0335PK2 |

| Proteinase K | Invitrogen | Cat#: 25530049 |

| oligodT dynabeads | Invitrogen | Cat#: 61002 |

| RIPA buffer | Roche | Cat#: 4719956001 |

| Q5® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | NEB | Cat#: M0491S |

| SYBR Green PCR master mix | Applied Biosystems | Cat#: A25742 |

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | ProSciTech | Cat#: C004–100 |

| Triton X-100 | ABCAM INC | Cat#: ab286840 |

| Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent | Fischer Scientific | Cat#: P10144 |

| Nail Polish | VWR International, INC | Cat#: 100491–940 |

|

Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Mycoalert Detection Kit | Lonza | Cat#: LT07–118 |

| CellTiter-Glo | Promega | Cat#: G7570 |

| RNAeasy Kit | Qiagen | Cat#: 74104 |

| SuperScriptTM III

First-Strand Synthesis System |

Invitrogen | Cat#: 18080051 |

| SMARTer smRNA-Seq Kit | Takara | Cat#: 635031 |

|

Deposited Data | ||

| Raw and analyzed Data | This paper; Mendeley data | Mendeley: https://doi.org/10.17632/nh58jyt5dt.1; GEO: GSE263237 |

| Unique Code | This paper; Zenodo | Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10901568 |

| CCLE annotations | DepMap Portal | Data S1.1; https://depmap.org/portal/download/ |

| TCGA annotations | UCSC Xena browser | Data S1.2; https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/?cohort=TCGA%20PanCancer%20(PANCAN)&removeHub=https%3A%2F%2Fxena.treehouse.gi.ucsc.edu%3A443 |

| GRCh37 cDNA sequences | Ensembl FTP archives | ftp://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-75/fasta/homo_sapiens/cdna/Homo_sapiens.GRCh37.75.cdna.all.fa.gz |

| hg19 FASTA reference | Broad Institute | console.cloud.google.com/storage/browser/_details/broad-references/hg19/v0/Homo_sapiens_assembly19.fasta |

| hg19 FASTA index | Broad Institute | console.cloud.google.com/storage/browser/_details/broad-references/hg19/v0/Homo_sapiens_assembly19.fasta.fai |

| Ensembl GTF | Ensembl | ftp://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-75/fasta/homo_sapiens/dna/Homo_sapiens.GRCh37.75.dna.primary_assembly.fa.gz |

|

Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| SW48 | ATCC | RRID: CVCL_1724 |

| 22rv1 | ATCC | RRID: CVCL_1045 |

| SK-MEL-2 | ATCC | RRID: CVCL_0069 |

| LNCap | ATCC | RRID: CVCL_0395 |

| ZR-75–1 | ATCC | RRID: CVCL_0588 |

| NCI-H2110 | ATCC | RRID: CVCL_1530 |

| C32 | ATCC | RRID: CVCL_1097 |

| MCF7 | ATCC | RRID: CVCL_0031 |

| PC3 | ATCC | RRID: CVCL_0035 |

| CAL851 | ATCC | RRID: CVCL_1114 |

| RKO | Andrew O. Giacomelli | RRID: CVCL_0504 |

| 293T | ATCC | RRID: CVCL_0063 |

|

| ||

| Oligonucleotides | ||

|

| ||

| See Table S2 for a list of oligonucleotides | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

|

| ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

|

| ||

| lentiCRISPR v2 plasmid | Feng Zhang, originally from Sanjana et al.44 | RRID: Addgene_52961 |

|

Software and Algorithms | ||

| Kallisto | Bray et al.46 | https://pachterlab.github.io/kallisto/download |

| Sleuth | Pimentel et al.47 | https://pachterlab.github.io/sleuth/download |

| GenePattern | Reich et al.48 | https://github.com/genepattern/genepattern-server/releases/tag/v3.9_12192023_b409 |

| STAR | Dobin et al.49 | https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR?tab=readme-ov-file |

| rMATS | Shen et al.50 | https://rnaseq-mats.sourceforge.io/ |

| FastQC | Andrews.51 | https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/download.html |

| Clip tool kit | Shah et al.52 | https://github.com/chaolinzhanglab/ctk |

| Cutadapt trimmer | Martin.53 | https://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/en/stable/installation.html |

| Integrative Genomics Viewer | Robinson et al.54 | https://igv.org/ |

| HOMER | Heinz55 | http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/ |

Highlights.

RPL22 p.K15fs mutations are highly prevalent in MSI-H cell lines and tumors

RPL22 mediates alternative splicing and expression of its paralog, RPL22L1

RPL22 loss increases MDM4 exon 6 inclusion, augmenting protein expression of MDM4

RPL22 modulates the MDM4-p53 pathway, thereby revealing it as a tumor suppressor in cancer

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all members of the Huang lab for their feedback and input. This work was supported in part by the NIH (P20CA233255, R01CA248920, and U19CA214253; F.W.H.), the Department of Veterans Affairs (I01CX002444; F.W.H.), the Department of Medicine at UCSF (F.W.H.), the Benioff Initiative for Prostate Cancer Research (F.W.H.), the Prostate Cancer Foundation (F.W.H.), the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub San Francisco (F.W.H.), and the NIH Research Project Grant Program (R01CA244634; H.G.).

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

F.V. receives research support from the Dependency Map Consortium, Riva Therapeutics, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Illumina, and Deerfield Management. F.V. is on the scientific advisory board of GSK, is a consultant and holds equity in Riva Therapeutics, and is a co-founder and holds equity in Jumble Therapeutics.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114622.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maruvka YE, Mouw KW, Karlic R, Parasuraman P, Kamburov A, Polak P, Haradhvala NJ, Hess JM, Rheinbay E, Brody Y, et al. (2017). Analysis of somatic microsatellite indels identifies driver events in human tumors. Nat. Biotechnol 35, 951–959. 10.1038/nbt.3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eso Y, Shimizu T, Takeda H, Takai A, and Marusawa H. (2020). Microsatellite instability and immune checkpoint inhibitors: toward precision medicine against gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary cancers. J. Gastroenterol 55, 15–26. 10.1007/s00535-019-01620-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortes-Ciriano I, Lee S, Park W-Y, Kim T-M, and Park PJ (2017). A molecular portrait of microsatellite instability across multiple cancers. Nat. Commun 8, 15180. 10.1038/ncomms15180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baugh EH, Ke H, Levine AJ, Bonneau RA, and Chan CS (2018). Why are there hotspot mutations in the TP53 gene in human cancers? Cell Death Differ. 25, 154–160. 10.1038/cdd.2017.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghandi M, Huang FW, Jané-Valbuena J, Kryukov GV, Lo CC, Mcdonald ER, Barretina J, Gelfand ET, Bielski CM, Li H, et al. (2019). Next-generation characterization of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Nature 569, 503–508. 10.1038/s41586-019-1186-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novetsky AP, Zighelboim I, Thompson DM, Powell MA, Mutch DG, and Goodfellow PJ (2013). Frequent mutations in the RPL22 gene and its clinical and functional implications. Gynecol. Oncol 128, 470–474. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan M, Wong WC, Brown R, Akbani R, Su X, Broom B, Melott J, and Weinstein J. (2016). TCGASpliceSeq a compendium of alternative mRNA splicing in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D1018–D1022. 10.1093/nar/gkv1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, O’Leary MN, Peri S, Wang M, Zha J, Melov S, Kappes DJ, Feng Q, Rhodes J, Amieux PS, et al. (2017). Ribosomal Proteins Rpl22 and Rpl22l1 Control Morphogenesis by Regulating Pre-mRNA Splicing. Cell Rep. 18, 545–556. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fahl SP, Harris B, Coffey F, and Wiest DL (2015). Rpl22 Loss Impairs the Development of B Lymphocytes by Activating a p53-Dependent Checkpoint. J.I. 194, 200–209. 10.4049/jimmunol.1402242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao S, Cai KQ, Stadanlick JE, Greenberg-Kushnir N, Solanki-Patel N, Lee S-Y, Fahl SP, Testa JR, and Wiest DL (2016). Ribosomal Protein Rpl22 Controls the Dissemination of T-cell Lymphoma. Cancer Res. 76, 3387–3396. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao S, Peri S, Hoffmann J, Cai KQ, Harris B, Rhodes M, Connolly DC, Testa JR, and Wiest DL (2019). RPL22L1 induction in colorectal cancer is associated with poor prognosis and 5-FU resistance. PLoS One 14, e0222392. 10.1371/journal.pone.0222392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu N, Wei J, Wang Y, Yan J, Qin Y, Tong D, Pang B, Sun D, Sun H, Yu Y, et al. (2015). Ribosomal L22-like1 (RPL22L1) Promotes Ovarian Cancer Metastasis by Inducing Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. PLoS One 10, e0143659. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Del Toro N, Fernandez-Ruiz A, Mignacca L, Kalegari P, Rowell M-C, Igelmann S, Saint-Germain E, Benfdil M, Lopes-Paciencia S, Brakier-Gingras L, et al. (2019). Ribosomal protein RPL22/eL22 regulates the cell cycle by acting as an inhibitor of the CDK4-cyclin D complex. Cell Cycle 18, 759–770. 10.1080/15384101.2019.1593708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Leary MN, Schreiber KH, Zhang Y, Duc A-CE, Rao S, Hale JS, Academia EC, Shah SR, Morton JF, Holstein CA, et al. (2013). The Ribosomal Protein Rpl22 Controls Ribosome Composition by Directly Repressing Expression of Its Own Paralog, Rpl22l1. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003708. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dewaele M, Tabaglio T, Willekens K, Bezzi M, Teo SX, Low DHP, Koh CM, Rambow F, Fiers M, Rogiers A, et al. (2016). Antisense oligonucleotide–mediated MDM4 exon 6 skipping impairs tumor growth. J. Clin. Invest 126, 68–84. 10.1172/jci82534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rallapalli R, Strachan G, Cho B, Mercer WE, and Hall DJ (1999). A Novel MDMX Transcript Expressed in a Variety of Transformed Cell Lines Encodes a Truncated Protein with Potent p53 Repressive Activity. J. Biol. Chem 274, 8299–8308. 10.1074/jbc.274.12.8299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bezzi M, Teo SX, Muller J, Mok WC, Sahu SK, Vardy LA, Bonday ZQ, and Guccione E. (2013). Regulation of constitutive and alternative splicing by PRMT5 reveals a role for Mdm4 pre-mRNA in sensing defects in the spliceosomal machinery. Genes Dev. 27, 1903–1916. 10.1101/gad.219899.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bieging-Rolett KT, Kaiser AM, Morgens DW, Boutelle AM, Seoane JA, Van Nostrand EL, Zhu C, Houlihan SL, Mello SS, Yee BA, et al. (2020). Zmat3 Is a Key Splicing Regulator in the p53 Tumor Suppression Program. Mol. Cell 80, 452–469.e9. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonald ER, de Weck A, Schlabach MR, Billy E, Mavrakis KJ, Hoffman GR, Belur D, Castelletti D, Frias E, Gampa K, et al. (2017). Project DRIVE: A Compendium of Cancer Dependencies and Synthetic Lethal Relationships Uncovered by Large-Scale, Deep RNAi Screening. Cell 170, 577–592.e10. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan EM, Shibue T, Mcfarland JM, Gaeta B, Ghandi M, Dumont N, Gonzalez A, Mcpartlan JS, Li T, Zhang Y, et al. (2019). WRN helicase is a synthetic lethal target in microsatellite unstable cancers. Nature 568, 551–556. 10.1038/s41586-019-1102-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo E-C, Nathanson JL, Tan FE, Schwartz JL, Schmok JC, Shankar A, Markmiller S, Yee BA, Sathe S, Pratt GA, et al. (2020). Large-scale tethered function assays identify factors that regulate mRNA stability and translation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 27, 989–1000. 10.1038/s41594-020-0477-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vassilev LT, Vu BT, Graves B, Carvajal D, Podlaski F, Filipovic Z, Kong N, Kammlott U, Lukacs C, Klein C, et al. (2004). In Vivo Activation of the p53 Pathway by Small-Molecule Antagonists of MDM2. Science 303, 844–848. 10.1126/science.1092472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam S, Lodder K, Teunisse AFAS, Rabelink MJWE, Schutte M, and Jochemsen AG (2010). Role of Mdm4 in drug sensitivity of breast cancer cells. Oncogene 29, 2415–2426. 10.1038/onc.2009.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia M, Knezevic D, Tovar C, Huang B, Heimbrook DC, and Vassilev LT (2008). Elevated MDM2 boosts the apoptotic activity of p53-MDM2 binding inhibitors by facilitating MDMX degradation. Cell Cycle 7, 1604–1612. 10.4161/cc.7.11.5929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu B, Gilkes DM, Farooqi B, Sebti SM, and Chen J. (2006). MDMX Overexpression Prevents p53 Activation by the MDM2 Inhibitor Nutlin. J. Biol. Chem 281, 33030–33035. 10.1074/jbc.C600147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao B, Fang Z, Liao P, Zhou X, Xiong J, Zeng S, and Lu H. (2017). Cancer-mutated ribosome protein L22 (RPL22/eL22) suppresses cancer cell survival by blocking p53-MDM2 circuit. Oncotarget 8, 90651–90661. 10.18632/oncotarget.21544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haupt S, Mejía-Hernández JO, Vijayakumaran R, Keam SP, and Haupt Y. (2019). The long and the short of it: the MDM4 tail so far. J. Mol. Cell Biol 11, 231–244. 10.1093/jmcb/mjz007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabunilas J, and Chanfreau G. (2016). Splicing-Mediated Autoregulation Modulates Rpl22p Expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 12, e1005999. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larionova TD, Bastola S, Aksinina TE, Anufrieva KS, Wang J, Shender VO, Andreev DE, Kovalenko TF, Arapidi GP, Shnaider PV, et al. (2022). Alternative RNA splicing modulates ribosomal composition and determines the spatial phenotype of glioblastoma cells. Nat. Cell Biol 24, 1541–1557. 10.1038/s41556-022-00994-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abrhámová K, and Folk P. (2019). Regulation of yeast RPL22B splicing depends on intact pre-mRNA context of the intron (Molecular Biology). 10.1101/814301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petibon C, Parenteau J, Catala M, and Elela SA (2016). Introns regulate the production of ribosomal proteins by modulating splicing of duplicated ribosomal protein genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 3878–3891. 10.1093/nar/gkw140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abrhámová K, Nemčko F, Libus J, Převorovský M, Hálová M, Půta F, and Folk P. (2018). Introns provide a platform for intergenic regulatory feedback of RPL22 paralogs in yeast. PLoS One 13, e0190685. 10.1371/journal.pone.0190685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sciarrillo R, Wojtuszkiewicz A, El Hassouni B, Funel N, Gandellini P, Lagerweij T, Buonamici S, Blijlevens M, Zeeuw van der Laan EA, Zaffaroni N, et al. (2019). Splicing modulation as novel therapeutic strategy against diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. EBioMedicine 39, 215–225. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang E, Lu SX, Pastore A, Chen X, Imig J, Chun-Wei Lee S, Hockemeyer K, Ghebrechristos YE, Yoshimi A, Inoue D, et al. (2019). Targeting an RNA-Binding Protein Network in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Cell 35, 369–384.e7. 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seiler M, Peng S, Agrawal AA, Palacino J, Teng T, Zhu P, Smith PG, Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network; Buonamici, S., Yu L, et al. (2018). Somatic Mutational Landscape of Splicing Factor Genes and Their Functional Consequences across 33 Cancer Types. Cell Rep. 23, 282–296.e4. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.01.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kahles A, Lehmann K-V, Toussaint NC, Hüser M, Stark SG, Sachsenberg T, Stegle O, Kohlbacher O, Sander C, Rätsch G, and Rätsch G. (2018). Comprehensive Analysis of Alternative Splicing Across Tumors from 8,705 Patients. Cancer Cell 34, 211–224.e6. 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Georgilis A, Klotz S, Hanley CJ, Herranz N, Weirich B, Morancho B, Leote AC, D’Artista L, Gallage S, Seehawer M, et al. (2018). PTBP1-Mediated Alternative Splicing Regulates the Inflammatory Secretome and the Pro-tumorigenic Effects of Senescent Cells. Cancer Cell 34, 85–102.e9. 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmed D, Eide PW, Eilertsen IA, Danielsen SA, Eknæs M, Hektoen M, Lind GE, and Lothe RA (2013). Epigenetic and genetic features of 24 colon cancer cell lines. Oncogenesis 2, e71. 10.1038/oncsis.2013.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prensner JR, Iyer MK, Balbin OA, Dhanasekaran SM, Cao Q, Brenner JC, Laxman B, Asangani IA, Grasso CS, Kominsky HD, et al. (2011). Transcriptome sequencing across a prostate cancer cohort identifies PCAT-1, an unannotated lincRNA implicated in disease progression. Nat. Biotechnol 29, 742–749. 10.1038/nbt.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Broad DepMap (2020). DepMap 19Q4 Public. (figshare). 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.11384241.V2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edgren H, Murumagi A, Kangaspeska S, Nicorici D, Hongisto V, Kleivi K, Rye IH, Nyberg S, Wolf M, Borresen-Dale A-L, and Kallioniemi O. (2011). Identification of fusion genes in breast cancer by pairedend RNA-sequencing. Genome Biol. 12, R6. 10.1186/gb-2011-12-1-r6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, Sondka Z, Beare DM, Bindal N, Boutselakis H, Cole CG, Creatore C, Dawson E, et al. (2019). COSMIC: the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D941–D947. 10.1093/nar/gky1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonneville R, Krook MA, Kautto EA, Miya J, Wing MR, Chen H-Z, Reeser JW, Yu L, and Roychowdhury S. (2017). Landscape of Mi-crosatellite Instability Across 39 Cancer Types. JCO Precis. Oncol 2017, 1–15. 10.1200/po.17.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanjana NE, Shalem O, and Zhang F. (2014). Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat. Methods 11, 783–784. 10.1038/nmeth.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shalem O, Sanjana NE, Hartenian E, Shi X, Scott DA, Mikkelson T, Heckl D, Ebert BL, Root DE, Doench JG, and Zhang F. (2014). Genome-Scale CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Screening in Human Cells. Science 343, 84–87. 10.1126/science.1247005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bray NL, Pimentel H, Melsted P, and Pachter L. (2016). Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol 34, 525–527. 10.1038/nbt.3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pimentel H, Bray NL, Puente S, Melsted P, and Pachter L. (2017). Differential analysis of RNA-seq incorporating quantification uncertainty. Nat. Methods 14, 687–690. 10.1038/nmeth.4324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reich M, Liefeld T, Gould J, Lerner J, Tamayo P, and Mesirov JP (2006). GenePattern 2.0. Nat. Genet 38, 500–501. 10.1038/ng0506-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, and Gingeras TR (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shen S, Park JW, Huang J, Dittmar KA, Lu Z.x., Zhou Q, Carstens RP, and Xing Y. (2012). MATS: a Bayesian framework for flexible detection of differential alternative splicing from RNA-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e61. 10.1093/nar/gkr1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andrews S. (2010). FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. [Online]. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shah A, Qian Y, Weyn-Vanhentenryck SM, and Zhang C. (2017). CLIP Tool Kit (CTK): a flexible and robust pipeline to analyze CLIP sequencing data. Bioinformatics 33, 566–567. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martin M. (2011). Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. j 17, 10. 10.14806/ej.17.1.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdó ttir H., Winckler., Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, and Mesirov JP. (2011). Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol 29, 24–26. 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, and Glass CK (2010). Simple Combinations of Lineage-Determining Transcription Factors Prime cis-Regulatory Elements Required for Macrophage and B Cell Identities. Mol. Cell 38, 576–589. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw RNA-seq and CLIP-seq data have been deposited at GEO and are publicly available as of the date of publication. The accession numbers is GEO: GSE263237. CCLE and TCGA data used in this study have been deposited at Mendeley and are publicly available as of the date of publication. The DOI is Mendeley Data: http://www.doi.org/10.17632/nh58jyt5dt.1. All other data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

All original code has been deposited at Zenodo and is publicly available as of the date of publication. The DOI is Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10901568.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.